Abstract

As sustainability becomes a strategic priority, the Information Technology (IT) sector faces pressure on both reducing its environmental impact and leading in innovation. This study examines how Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) practices influence employees’ Green IT Attitudes (GITA) and beliefs within the IT industry. Guided by the Belief–Action–Outcome (BAO) framework, it explores how HR strategies can foster eco-conscious mindsets that support sustainable behaviour. A quantitative cross-sectional design was used, collecting data through a validated questionnaire. The study was conducted in Australia, focusing on IT professionals employed. Responses from 112 IT professionals, determined through G*Power sample estimation, were analysed using SPSS 28.0.1 with regression techniques to assess the relationship between GHRM practices and environmental attitudes and beliefs. Results indicate that GHRM practices have a modest but significant positive effect on employees’ green IT attitudes and beliefs, supporting the view that structured HR initiatives can shape sustainability-driven mindsets. The findings emphasize the strategic role of HR in embedding sustainability within organizational culture, particularly in technology-driven environments. The study offers practical guidance for IT organizations aiming to integrate sustainability into internal systems by leveraging HRM. Future research should examine moderating variables and long-term behavioural effects, enhancing our understanding of sustainability-focused HRM in the digital era.

1. Introduction

The corporate landscape has experienced a profound shift toward sustainability over recent decades. Academic research highlights a growing emphasis on integrating sustainable practices across operational and strategic domains (Ojo et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2013). This shift responds to urgent global challenges such as climate change and industrial contributions to environmental degradation (Nidumolu et al., 2009).

Sustainability today extends beyond physical practices, it encompasses corporate values, leadership, and strategic frameworks. Global frameworks like the Environmental Management System (EMS) offer structured approaches for adopting sustainable practices. Prominent examples include Aware Super in Australia reallocating A$1 billion from traditional to green bonds, and the global commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Hák et al., 2016).

“Green” has emerged as a central theme in environmental discourse (Loknath & Azeem, 2017; Dumont et al., 2017; Ojo & Raman, 2019), symbolising organisational commitment to eco-conscious practices. Particularly within the Information Technology (IT) sector, sustainability is becoming increasingly relevant. While digital by nature, the IT industry contributes to environmental concerns such as energy consumption and e-waste. It also offers tools and systems that support sustainable practices (Khuntia et al., 2018; Molla et al., 2008).

In Australia, approximately 377,000 professionals were employed in the ICT sector in 2020 (Statista, 2020), surpassing traditional sectors like manufacturing and finance. The industry’s ecological footprint necessitates alignment with the SDGs and EMS standards. Adoption of frameworks such as Green IT and Green HRM has gained momentum, with Green HRM in particular offering a mechanism to align employee behaviours with sustainability goals (Dumont et al., 2017; Zoogah, 2011; Nash & Wakefield, 2021).

This study was inspired by a simple but powerful observation: the presence of green recycling bins in Sydney workplaces. This prompted reflection on whether small, localised initiatives could contribute to broader environmental goals. With IT’s organisational agility and technological capacity, it is well-positioned to integrate environmentally responsible practices. Given Australia’s ranking as the third-highest CO2 emitter per capita (Olivier et al., 2020), this integration is especially urgent.

Despite extensive research on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) and Green Information Technology (Green IT), existing studies have predominantly focused on behavioural and organisational performance outcomes, with comparatively limited attention to the underlying cognitive foundations that precede such behaviour. In particular, how Green HRM influences employees’ Green IT attitudes and Green IT beliefs, key cognitive precursors to sustainable behaviour—remains insufficiently examined within the IT sector. While prior research has established links between Green HRM and employee eco-behaviour (Dumont et al., 2017; Zoogah, 2011), the extent to which HR-driven sustainability practices shape employees’ internalisation of Green IT values has not been empirically tested. Addressing this gap is important, as sustainable IT behaviour is unlikely to emerge without first influencing how employees think about and evaluate the environmental role of IT (Murugesan, 2008).

Accordingly, this study aimed to examine the impact of Green HRM practices on IT professionals’ Green IT attitudes and Green IT beliefs within the Australian IT sector.

The research questions guiding this study are:

- RQ1: Does Green HRM impact Green IT attitudes in the IT sector?

- RQ2: Does Green HRM impact Green IT beliefs in the IT sector?

The study focused on IT professionals employed in Australian companies that have adopted Green HRM policies. The internal organisational environment serves as the unit of analysis, with emphasis on how these policies shape employees’ Green IT mindsets. While geographically confined to Australia, the findings offer implications for global IT sectors. By adopting a bottom-up perspective, centred on employees, this study highlights how sustainability is internalised at the micro level. Given the evolving nature of Green IT, this targeted scope ensures analytical feasibility while providing practical insights for sustainable transformation.

This study is theoretically grounded in the Belief–Action–Outcome (BAO) framework, which explains how organisational practices shape employees’ beliefs, which subsequently inform their attitudes and behavioural tendencies. The BAO model is complemented by cognitive–behavioural theory (e.g., Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), which differentiates between beliefs as cognitive appraisals and attitudes as evaluative judgments shaped by those beliefs. Together, these theories provide a coherent foundation for examining how Green HRM practices influence the early cognitive mechanisms underpinning Green IT behaviour.

This research offers two key contributions. Theoretically, it addresses a clear gap in prior work by examining the distinct yet sequential cognitive processes—beliefs and attitudes—through which HR-driven sustainability initiatives may influence Green IT behaviour. Practically, the study provides organisations with evidence on whether Green HRM practices meaningfully shape employees’ environmental mindsets in IT contexts, informing the development of targeted sustainability strategies. By articulating these contributions, the study advances the understanding of the HR–IT sustainability interface and establishes a clear rationale for the analyses that follow. This study contributes by (1) empirically linking Green HRM with Green IT attitudes and beliefs, (2) applying the BAO framework to explain cognitive pathways in green IT behaviour, and (3) providing Australia-specific evidence on sustainability in the IT industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Introduction

This literature review begins by outlining the theoretical foundations that underpin Green HRM and Green IT, followed by a structured synthesis of previous empirical studies and the development of the study’s hypotheses. This section provides the theoretical foundation for the study by critically reviewing existing scholarship on Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) and Green Information Technology (Green IT), with particular focus on employee attitudes and beliefs. Green IT refers to the environmentally responsible use of technology, while Green HRM encompasses HR practices designed to promote sustainability within organisations. Existing literature demonstrates that Green HRM initiatives, such as eco-focused recruitment, training, and performance appraisal, can influence employee engagement with sustainability goals. However, limited research explicitly explores how these practices affect IT professionals’ beliefs about environmental responsibility or their attitudes toward sustainable IT practices. The review highlights the significance of internal organisational mechanisms, such as HRM, in shaping pro-environmental behaviours, particularly in sectors like IT that both contribute to and can help mitigate environmental degradation. Concepts such as perceived behavioural control, normative commitment, and ecological efficacy emerge as key constructs in understanding how Green IT beliefs are formed. The review also identifies a gap in empirical studies linking Green HRM practices to the cognitive and affective dimensions of Green IT engagement within the IT industry. Addressing this gap, the study proposes a conceptual framework positioning Green HRM as a driver of Green IT mindsets. This framework supports the development of hypotheses for empirical validation and serves as a basis for practical recommendations to align human resource strategies with environmental objectives. The literature review thus positions this research at the intersection of sustainability, human resource practices, and technology management.

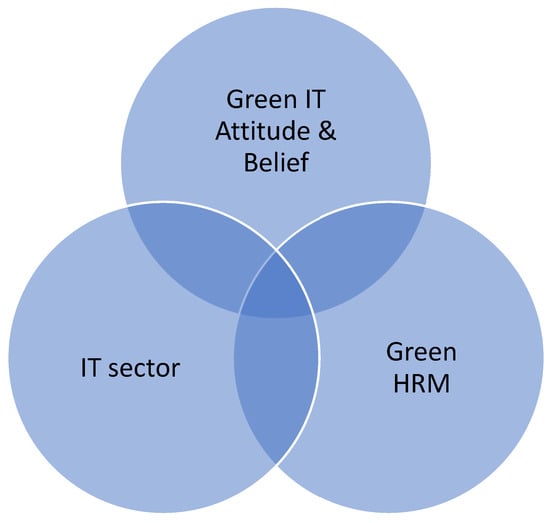

The literature review structure comprises three variables, as seen in Figure 1. Green HRM overlaps with the IT sector, and the dependent variable, Green IT attitudes and beliefs, will be examined in light of the published literature separately as well as jointly with the other two variables. A similar strategy will be followed for Green IT attitudes and beliefs and the IT sector.

Figure 1.

Literature Review Structure.

Figure 1 represents the Literature Review Structure.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in several interrelated theories that help explain how organisational strategies can shape employees’ sustainability-related mindsets and behaviours in the IT sector. Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) is positioned as a strategic organisational approach that fosters eco-conscious behaviours by embedding sustainability into recruitment, training, and appraisal processes. Green IT, in parallel, refers to environmentally sustainable practices within technology management, such as energy efficiency and responsible e-waste disposal (Murugesan, 2008; Iacobelli et al., 2010). The study draws on the Belief–Action–Outcome (BAO) model, which posits that organisational and societal influences shape individual beliefs, which in turn drive actions that result in environmental or financial outcomes (Melville, 2010). In this research, emphasis is placed on the first two stages, belief formation and subsequent action. The Supplies-Values Fit theory (Edwards, 1996) is also relevant, highlighting how alignment between individual values and organisational environmental practices can enhance motivation and engagement, with the “carryover” effect enabling surplus resources or values to influence broader workplace behaviour. Additionally, the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1985), and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) collectively reinforce the idea that beliefs and attitudes serve as key antecedents to intention and behaviour. These theories offer a robust framework for examining how Green HRM initiatives may influence Green IT mindsets, laying the conceptual foundation for the study’s empirical model. To study the connections or relationships between different ideas or topics, it is essential to have a solid foundation or starting point. This foundation is often based on existing theories that researchers have previously established.

2.2.1. Green HRM

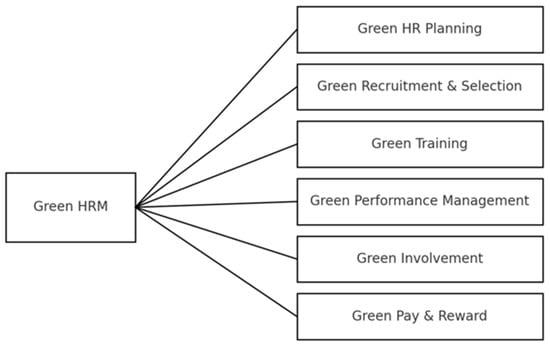

Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) integrates environmental sustainability into conventional HRM functions, aiming to foster pro-environmental behaviours among employees and align organisational practices with ecological goals. Scholars have conceptualised Green HRM as a strategic approach that leverages HR policies and processes, such as recruitment, training, performance management, and rewards—to promote sustainability (Rani & Mishra, 2014; Dumont et al., 2017). Rani and Mishra (2014) describe it as a means to cultivate environmental awareness and commitment among employees. Similarly, Dumont et al. (2017) frame Green HRM as a system of practices designed to enhance employees’ green behaviours at work. Zoogah (2011) highlights the role of Green HRM in ensuring the sustainable use of resources and preventing environmental harm through targeted HR strategies. From an organisational lens, Pillai and Sivathanu (2014) position Green HRM as a mechanism for embedding sustainability principles within corporate structures and culture. Collectively, these perspectives underscore the pivotal role of HRM in driving sustainability transformations within organisations. Figure 2 aims to visualise Green HRM.

Figure 2.

Green HRM (Source: Dumont et al., 2017).

Green HRM has evolved from earlier concepts like sustainable or environmental HRM (Milliman & Clair, 1996; Madsen & Ulhøi, 2001) into a formalised framework aimed at aligning human resource functions with organisational environmental goals (Renwick et al., 2008). Scholars have categorised Green HRM into several domains—such as recruitment, selection, training, performance management, and rewards—each designed to promote sustainability through people-focused strategies (Dumont et al., 2017; Ojo & Raman, 2019). Green recruitment seeks candidates whose values align with environmental goals, while Green selection integrates eco-conscious criteria into hiring processes (Wehrmeyer, 1996; Pham & Paillé, 2019). Training and development initiatives equip employees with skills in areas such as waste management and green innovation (Jackson et al., 2011; Zakaria, 2012). Performance appraisal frameworks increasingly evaluate environmental contributions alongside conventional metrics (P. Mishra, 2017), and reward systems, financial or otherwise, are used to reinforce pro-environmental behaviours (Arulrajah et al., 2015). While definitions vary, the overarching aim of Green HRM is to embed sustainability across the employee lifecycle and shape a workforce that champions ecological responsibility within and beyond the organisation.

2.2.2. Green IT Attitude

Green IT refers to the environmentally responsible design, usage, and disposal of information technologies, aimed at reducing ecological impact (Murugesan, 2008; Akman & Mishra, 2015). It encompasses initiatives such as energy-efficient computing, responsible recycling, power management, and the integration of renewable energy (Murugesan, 2008; Jenkin et al., 2011). The concept is increasingly embedded in organisational strategies under broader sustainability goals. Molla et al. (2008) developed a “G-readiness framework” identifying enablers like policy, governance, attitude, and technology that support Green IT adoption.

Green IT attitude is defined as an individual’s favourable or unfavourable disposition toward environmentally sustainable IT practices (Molla et al., 2014). This attitude can be shaped by internal beliefs as well as organisational signals such as CSR efforts (Gross & Holland, 2011). The theoretical underpinnings lie in the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1985) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991), both of which emphasise that behavioural intention is shaped by attitudes, beliefs, and perceived control. A pro-environmental attitude among employees is more likely to develop when they are aware that their IT-related behaviours can contribute positively to sustainability goals (Ojo et al., 2020). Organisational commitment to sustainability, therefore, plays a key role in cultivating and reinforcing Green IT attitudes.

2.2.3. Green IT Belief

Green IT belief refers to IT professionals’ perceptions and awareness of the environmental impact of their work and their role in mitigating it (Molla et al., 2014). Beliefs are shaped by knowledge and awareness, which then influence pro-environmental behaviours (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002; Amel et al., 2009). As supported by the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) and the Theory of Reasoned Action, knowledge and intention are critical in translating beliefs into action (D. Mishra et al., 2014).

Beliefs are not static; they evolve with cognitive exposure and practical experience. Ojo et al. (2018) emphasise that Green IT beliefs are strengthened when individuals are provided with environmentally friendly technologies and are educated on their relevance and use. Thus, Green IT beliefs are foundational to sustainable IT behaviour and are closely linked to awareness, knowledge acquisition, and organisational practices that promote environmental consciousness.

Although related, beliefs and attitudes represent conceptually distinct stages of cognition. Beliefs refer to an individual’s perceptions or knowledge about an object or phenomenon, whereas attitudes reflect the evaluative judgment—positive or negative—formed on the basis of those beliefs (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen, 1991). Cognitively, beliefs are informational in nature, while attitudes are affective–evaluative responses shaped by those underlying beliefs. This distinction is well-established in behavioural theory, which positions beliefs as antecedents to attitudes and, subsequently, to behavioural intentions. For these reasons, the present study examines Green IT beliefs and Green IT attitudes as separate variables, capturing two different but sequential levels of cognitive processing that together shape sustainability-related behaviour in the IT context.

2.3. Previous Studies and Research Gap

Research at the intersection of Green Human Resource Management (Green HRM) and Green Information Technology (Green IT) has grown steadily, revealing important insights into how organisations foster sustainability. Foundational theories such as Festinger’s cognitive dissonance and Fishbein and Ajzen’s work on attitudes and beliefs have helped establish that changes in belief systems can influence attitudes and, subsequently, behaviours. These principles are particularly useful when applied to the environmental context, where beliefs about ecological responsibility often shape workplace attitudes toward sustainable practices.

In the domain of Green IT, studies have used models like the New Ecological Paradigm (P. C. Stern et al., 1995) and Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) to connect environmental concern with individual responsibility and action. For instance, Steg and Sievers (2000) demonstrated that pro-environmental behaviour is significantly shaped by personal risk perception and a sense of environmental responsibility. Similarly, P. Stern (2000) highlighted the importance of understanding individual behaviours within both public and private spheres of environmental action, suggesting that each behavioural outcome must be theorised separately.

Parallel to this, a growing body of literature has examined the influence of Green HRM on the pro-environmental behaviour of IT employees. Ojo et al. (2020) found that specific HR practices—such as green training and development—have a strong association with environmentally responsible actions within IT settings. Ruchismita et al. (2015) reported that IT firms implementing Green HRM saw improvements in energy-saving behaviours, reduced paper usage, and increased carpooling. While Sakhawalkar and Thadani (2015) did not find strong statistical correlations, they observed notable changes in environmental awareness due to Green HRM practices. Studies by Loeser et al. (2013) and Molla et al. (2011) also underscore the strategic potential of Green HRM in promoting innovation and improving organisational performance, though not always labelled explicitly as such.

Some researchers have taken a more integrated view. For example, Yusoff et al. (2015) linked Green HRM and electronic HRM practices to employee attitudes through the lens of the Technology Acceptance Model. Others, like Zhang et al. (2013), explored how Green HRM influences the environmental dimension of technology acceptance. Despite these efforts, only a few studies have explicitly examined how Green HRM shapes the underlying attitudes and beliefs of IT employees toward Green IT—constructs that are arguably essential precursors to behavioural change.

While prior research has thoroughly explored how Green HRM encourages pro-environmental behaviours in general, particularly within the IT sector, there is limited empirical investigation into how these HRM practices influence the foundational elements—namely, Green IT attitudes and beliefs. Understanding these precursors is essential because sustainable behaviour in IT cannot occur without a shift in how professionals think and feel about environmental issues related to their work.

Therefore, this study aims to bridge this overlooked intersection by examining how Green HRM practices influence Green IT mindsets, particularly the beliefs and attitudes of IT professionals. By doing so, it contributes to both the theoretical discourse and practical implementation of sustainability within technology-driven organisations. It also offers strategic insights for leveraging HRM as a catalyst for developing environmentally conscious work cultures that align with broader organisational sustainability goals.

2.4. Hypotheses Development

Building on the theoretical distinctions outlined above and the empirical gaps identified in previous studies, this research proposes two hypotheses examining the predictive role of Green HRM on employees’ Green IT mindsets. The literature indicates that Green HRM practices can influence pro-environmental behaviour through mechanisms such as values alignment, green training, and organisational climate; however, prior work has not explicitly tested their effect on the cognitive antecedents of Green IT—namely attitudes and beliefs. As established in the Belief–Action–Outcome (BAO) framework, organisational practices influence employee beliefs, which subsequently shape attitudes and inform behaviour. Accordingly, and consistent with the conceptual separation of beliefs and attitudes presented in the theoretical framework, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1:

Green HRM positively predicts Green IT Attitudes among IT professionals.

H0:

Green HRM does not predict Green IT Attitudes among IT professionals.

H2:

Green HRM positively predicts Green IT Beliefs among IT professionals.

H0:

Green HRM does not predict Green IT Beliefs among IT professionals.

3. Research Methodology

This study adopted a quantitative, survey-based design aligned with a positivist orientation, as the research aims to examine statistically testable relationships between Green HRM practices and Green IT cognitive outcomes across a defined population of IT professionals. Quantitative, cross-sectional research design was employed, using pre-validated scales to collect data at a single point in time (Setia, 2016). Survey research, conducted through structured questionnaires, was used to gather insights from IT professionals. This approach allowed for the examination of variable relationships, and the generalisation of findings from the selected sample to the broader population (Isaac & Michael, 1997; Kraemer, 1991).

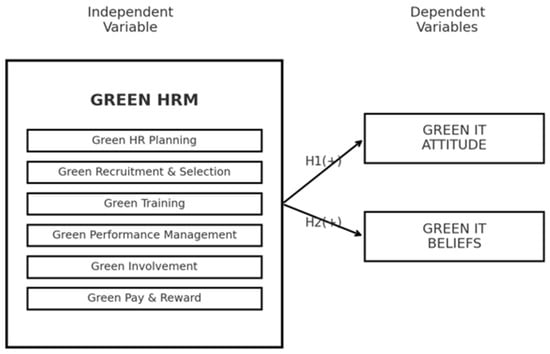

Since this study aimed to explore the impact of Green HRM on Green IT attitudes and beliefs, it primarily had three variables, as can be seen in Figure 3. Dumont et al. gave the following definition for Green HRM (Dumont et al., 2017):

“A set of practices that organisations adopt with the purpose of improving employee workplace Green behaviour”.

Figure 3.

Conceptual Framework.

According to the discussion in Section 2, the scholarly work on Green HRM has generally recognised it as a concept, set of practices, or managerial tool that when adopted, contributes towards ingraining a pro-environmental outlook of the employees. A reflection of this was seen in the definition given by Rani and Mishra, where they defined Green HRM as a concept that when incorporated, propels every employee to support sustainability, and as its ultimate goal, increases employee responsiveness and commitments to the problem to sustainability (Rani & Mishra, 2014).

Since this research enquires into the impact that Green HRM can have on the two dependent variables, both definitions seem accurate. However, since the research tool was adopted from Dumont et al. (2017), the baseline definition by the same authors will be used.

Due to the limited available literature on the synthesised definitions of Green IT attitudes and beliefs, this study used the definition given by Molla et al. (Molla et al., 2014).

Green IT attitude was defined as “A positive or negative feeling about the environment and the role of IT”.

Considering the previous discussion in this research, attitude or a positive or negative feeling are precursors of behaviour, and since behaviour can be impacted by Green HRM, this definition is deemed suitable with Research Question 1 (RQ1). Similarly, Molla et al. (2014) defined Green IT belief as “The perception and cognition of IT professionals about the environmental impact of IT and their role”, which was deemed suitable for examining Research Question 2 (RQ2) of this study due to impact of Green HRM on employee responsiveness and commitment, as explained by Rani and Mishra (2014).

3.1. Conceptual Framework

The reviewed literature and selected definitions indicate that Green HRM influences employees’ Green behaviour (Dumont et al., 2017; Saifulina et al., 2020). As discussed in the BAO model (Section 2), organisational and societal contexts shape employee attitudes and beliefs. This raises a relevant question in the IT sector: can Green HRM similarly influence IT employees’ environmental perspectives? Given existing correlations between Green HRM and IT (Loeser et al., 2013; Ojo et al., 2020), RQ1 explores whether Green HRM fosters positive Green IT attitudes among employees.

The BAO framework was specifically chosen for this study because it emphasises the sequential role of beliefs and attitudes as precursors to behavioural outcomes. Unlike alternative behavioural theories that focus primarily on behavioural intention (e.g., Theory of Planned Behaviour) or perceived usefulness (e.g., TAM), the BAO model aligns directly with the study’s objective of examining how organisational inputs—such as Green HRM practices—shape early cognitive stages rather than final behaviours. BAO therefore provides the most appropriate lens for isolating the belief-formation and attitude-formation mechanisms that underpin Green IT behaviour.

Similarly, RQ2 builds on Ojo and Raman (2019), who found that Green HRM affects pro-environmental IT behaviour. Grounded in the TAM and Ajzen’s (1991) theory—where beliefs influence behaviour—this study investigated whether Green HRM also shapes Green IT beliefs.

Figure 3 represents the conceptual framework of this research.

Figure 3 gives a clear indication of hypotheses formulation where the impact of Green HRM, as explained by Dumont et al. (2017), will be explored on the variables Green IT attitudes and beliefs as defined by Molla et al. (2014). The intention of this research is to question whether, when managerial aspects such as HRM integrate sustainable practices (Green HRM), they generate an impact on the attitudes and beliefs that employees of the IT industry hold about their actions and the consequences of these actions on the environment, as explained in the literature review.

Beliefs and attitudes were examined as independent constructs because each captures a different cognitive mechanism through which Green HRM may exert influence. Green HRM practices may shape employees’ knowledge and perceptions about environmental impacts (beliefs) as well as their evaluative orientation toward sustainable IT practices (attitudes). Treating these constructs independently allows the model to identify which cognitive domain is more responsive to HR-driven environmental initiatives, consistent with prior Green IT and organisational behaviour research (Molla et al., 2014).

3.2. Data Collection

This study adopted a quantitative research design, collecting data through a close-ended questionnaire that used a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire items were based on established instruments, with Green HRM measures adapted from Dumont et al. (2017), and Green IT Attitudes and Beliefs adapted from Molla et al. (2014). These tools have been validated in earlier research and were selected to ensure the reliability and consistency of data across variables.

The research targeted currently employed professionals in the Australian IT sector. Thus, the empirical context of this study is Australia. According to Kim (2005), this includes individuals engaged in IT management, systems development and integration, technical services and operations, network management, and PC end-user support. From this defined population, participants were selected using targeted purposive sampling, rather than convenience sampling. This approach was chosen because the study required participants who met specific eligibility criteria: (1) current employment in an IT-related role, (2) affiliation with an ISO 14001-certified organisation (International Organization for Standardization, 2015), and (3) representation across a range of job functions and organisational levels.

LinkedIn was used as the primary recruitment platform because it enables accurate verification of professional roles, organisational affiliation, and industry sector, making it suitable for identifying individuals who met the study’s predefined criteria. While this method may exclude inactive LinkedIn users, it remains the most comprehensive professional database for Australia’s IT workforce. To mitigate representational bias, invitations were extended across multiple companies, cities, and job families to ensure heterogeneity in role types and organisational context.

Eligible participants were approached via direct LinkedIn messages. Those who expressed interest received an electronic consent form, followed by a link to the questionnaire hosted on Google Forms. Participation was voluntary, withdrawal was permitted at any stage, and confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained.

The required sample size was calculated using G*Power version 3.1.9.4, based on an expected effect size of 0.25. The standard deviations for the variables were drawn from Dumont et al. (2017) and Ojo et al. (2019), resulting in a minimum required sample of 112 participants. The survey required approximately 20–30 min to complete.

The questionnaire was designed to measure employees’ perceptions of their organisation’s Green HRM practices as well as their own Green IT-related attitudes and beliefs. The original authors of the measurement instruments were contacted via ResearchGate for further clarification, ensuring accurate adaptation. A detailed overview of the items and variables is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Constructs of the Variables.

For clarity, brief examples of the items used to measure each construct are provided here. Green HRM items were adapted from Dumont et al. (2017), such as “My company provides Green training to develop knowledge and skills required for environmental management”. Green IT Attitude items were adapted from Molla et al. (2014), for example “I am concerned about reducing It is power usage”. Green IT Belief items were also taken from Molla et al. (2014), such as “I believe that IT equipment contributes to greenhouse gas emissions”. An overview of the constructs and example items is presented in Table 1, while the complete questionnaire, including all measurement items and rating scales, is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

To test Hypothesis 1 (H1) and address Research Question 1 (RQ1), items 1–6 and 7–10 will be analysed to explore the relationship between Green HRM and Green IT attitudes. For Hypothesis 2 (H2) and RQ2, items 1–6 and 11–15 will be examined to determine the influence of Green HRM on Green IT beliefs.

This study draws on the Belief–Action–Outcome (BAO) framework, which posits that organisational structures, such as Green HRM, shape individual beliefs (e.g., Green IT beliefs and attitudes), which may lead to pro-environmental behaviours that support organisational sustainability (Molla et al., 2014). While prior research suggests that organisational factors influence Green IT cognition, this study sought to isolate the specific contribution of Green HRM practices.

The measurement tools have been validated in prior research. ISO 14001 certification was used as an inclusion criterion to ensure that participating organisations practise environmental management (Boaden & Lockett, 1991; Ojo et al., 2020). The sampling strategy aligns with Burmeister and Aitken (2012), and regression analysis was employed as per the methodologies used in similar studies, such as Chaudhary (2020).

As in every competent study that is conducted, this research will also analyse the proposed hypotheses in the conceptual framework through inferential statistics and descriptive analysis.

3.3. Data Analysis

To examine the proposed theoretical framework and test the two hypotheses (H1 and H2), data were analysed using SPSS version 28.0.1. This software was chosen for its ease of use and effective visual outputs, which support both statistical testing and interpretation. The analysis employed inferential statistical techniques to assess the relationships between variables and to enable generalisation from the sample to the broader population.

Reliability of the measurement scales will be assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with a threshold of 0.6 or higher considered acceptable for internal consistency. Descriptive statistics will also be used to support the validity of the items and constructs, based on previously validated instruments.

Linear regression analysis was used to assess the effect of Green HRM on Green IT attitudes and Green IT beliefs. Adjusted R2 will serve as the primary measure of model fit, representing the proportion of variance in the dependent variables explained by the independent variable. A higher adjusted R2 reflects greater predictive strength. Hypotheses were considered statistically significant if the p-value was equal to or less than 0.05.

To determine the strength and direction of relationships, the correlation coefficient (r) was examined. This value, ranging from +1 to −1, indicates whether the association is strong or weak, positive or negative. These tests will help confirm whether Green HRM significantly influences pro-environmental attitudes and beliefs among IT employees, as proposed in the study’s hypotheses.

4. Results

Ethical protocols were strictly followed throughout the data collection process. Informed consent was obtained from the participants, who were briefed on the research objectives, benefits, and risks. Questions were designed to be non-intrusive, avoiding any personal or distressing content, ensuring privacy and voluntary participation. No personal identifiers were collected, and participant confidentiality remained a priority. Once data were gathered, sensitive information was removed, and datasets were uploaded to Figshare with the appropriate metadata. A DOI was generated for citation and transparency purposes, ensuring that the data remain publicly accessible for five years in alignment with responsible research standards.

To identify suitable participants, the study targeted ISO 14001-certified IT companies in Australia. Through strategic keyword searches, a list of companies was compiled and shortlisted based on location and certification status, as presented in Table 2. This table outlines the names and cities of the IT firms considered for recruitment.

Table 2.

List of companies shortlisted by set criteria.

From these shortlisted firms (see Table 2), 732 employees were approached via LinkedIn. A total of 189 agreed to participate, and the sample was finalised at 112 responses. Each participant received a consent form followed by a structured questionnaire hosted on Google Forms. A Case Processing Summary confirmed the absence of missing values, indicating a clean and reliable dataset (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Case processing summary for the study variables.

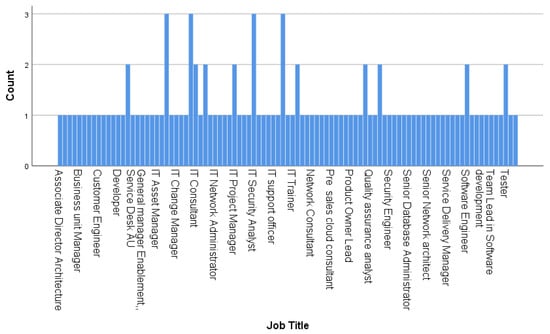

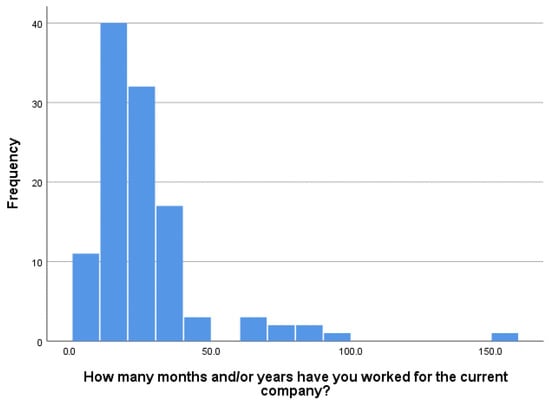

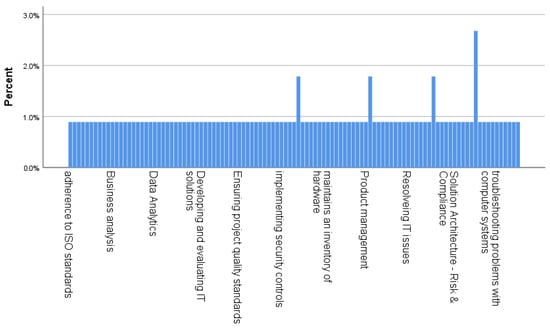

Three open-ended questions at the start of the survey captured the participants’ job titles, tenure, and scope of work—adapted from Dumont et al. (2017). Responses were visually analysed. Job roles were carefully categorised (Figure 4); tenure distribution showed most participants had 10–30 months at their current company (Figure 5), and a wide range of scopes of work was recorded (Figure 6), reflecting the diverse roles held by the respondents.

Figure 4.

Job titles of the study participants.

Figure 5.

Distribution of employee tenure at current company.

Figure 6.

Scope of work of the study participants.

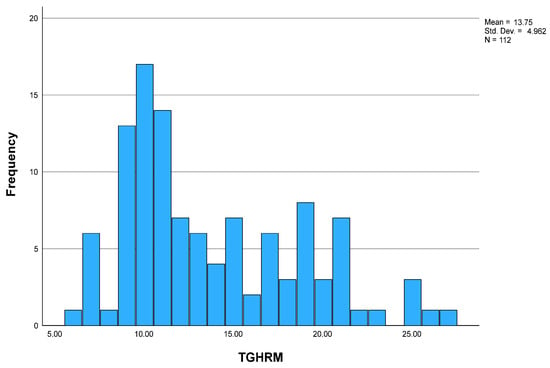

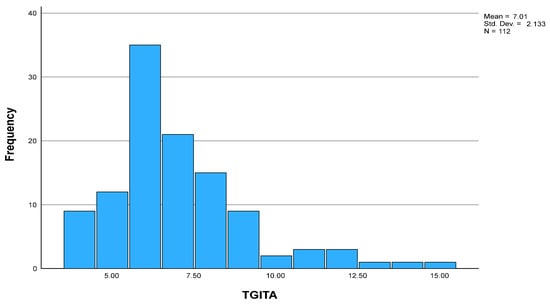

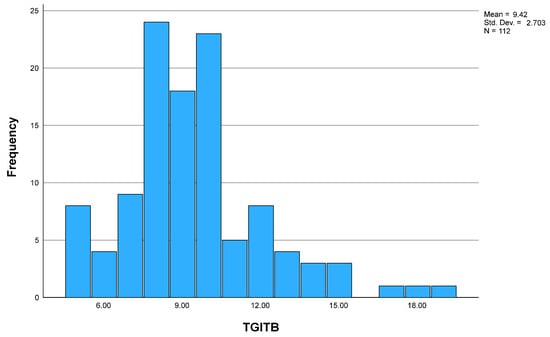

The core variables of the study, Green Human Resource Management (GHRM), Green IT Attitudes (GITA), and Green IT Beliefs (GITB)—were measured through a 15-item Likert-scale questionnaire. Each variable showed a complete response rate, with no missing data. Table 4 summarises the descriptive statistics, including mean, median, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. GHRM had a mean score of 13.75, GITA 7.01, and GITB 9.42. Skewness and kurtosis values indicated moderate deviations from normality, with GITA showing the highest skew (1.315) and kurtosis (2.276), suggesting some concentration of values above the mean. Despite these variations, the values remained within acceptable thresholds, allowing progression to regression analysis.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for GHRM, GITA, and GITB Constructs.

Understanding the shape and distribution of the data through skewness and kurtosis was important to assess its suitability for linear regression. Positive skew indicated a longer right tail in the data, and kurtosis offered insight into the sharpness or flatness of the curve. As regression assumes normality, these descriptive insights were crucial for validating subsequent inferential analyses. Histogram and scatterplot inspections, discussed later in the Results section, provide further evidence supporting the dataset’s fit for regression modelling.

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test Results

To assess internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was used for each of the three variables. Values above 0.7 were considered acceptable, with 0.8–0.9 viewed as good, and above 0.9 as very good (Bujang et al., 2018).

- Green HRM (GHRM):

With six items, the scale showed good reliability (α = 0.878) (see Table 5). As detailed in Table 6, most items had high item-total correlations (above 0.75), particularly GHRM4–GHRM6. However, GHRM2 displayed a weak correlation (0.086). Despite this, it was retained due to the overall strength of the scale.

Table 5.

Reliability statistics of GHRM.

Table 6.

Items total statistics for GHRM.

- Green IT Attitudes (GITA):

This four-item scale showed acceptable reliability (α = 0.700) (see Table 7). Table 8 shows that each item contributed meaningfully, with GITA3 having the highest impact on reliability. Removing any item would reduce the alpha below 0.7, supporting the decision to retain all items.

Table 7.

Reliability statistics of GITA.

Table 8.

Items total statistics of GITA.

- Green IT Beliefs (GITB):

With five items, GITB demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.803) (see Table 9). Table 10 indicates that all items had strong item–total correlations, particularly GITB2–GITB5. Removing any would weaken the overall scale, confirming the internal consistency of the construct.

Table 9.

Reliability statistics of GITB.

Table 10.

Items total statistics of GITB.

4.2. Assumptions of Linear Regression

Before conducting linear regression, four key assumptions were examined: linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and independence of errors. These tests ensure the model’s suitability for the data and the robustness of the analysis.

Linearity was assessed using comparison of means analysis. As shown in Table 11 and Table 12, the relationships between GHRM and both GITA (p = 0.014) and GITB (p = 0.024) demonstrated statistically significant linearity, with no significant deviation, confirming that the data met the linearity assumption.

Table 11.

Comparison of means for GHRM*GITA.

Table 12.

Comparison of means for GHRM*GITB.

The Shapiro–Wilk test was conducted for normality checking, which indicated non-normality across variables (Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15), with p-values < 0.001.

Table 13.

Shapiro–Wilk test for GHRM.

Table 14.

Shapiro–Wilk test for GITA.

Table 15.

Shapiro–Wilk test for GITB.

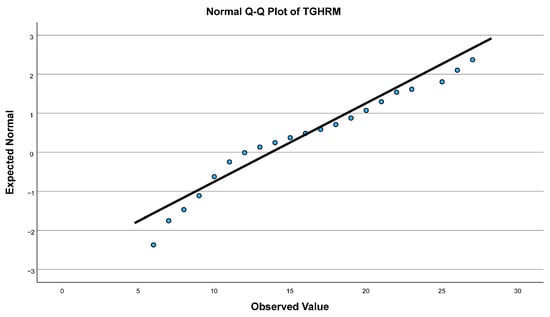

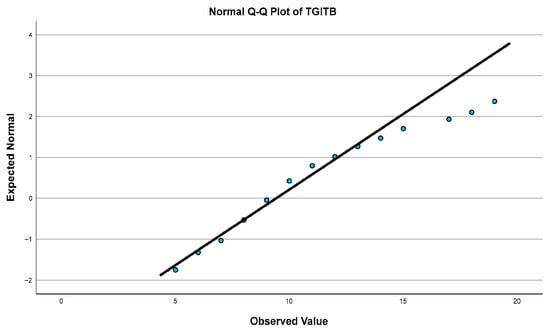

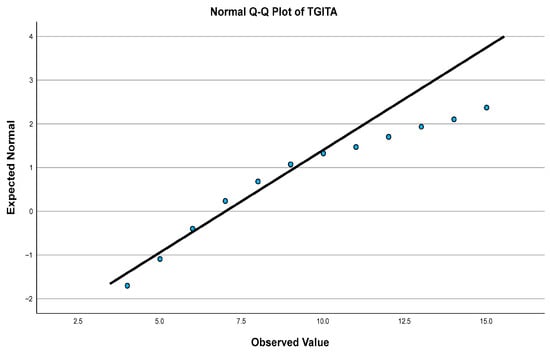

However, the histogram plots (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9) and Q-Q plots (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12) revealed acceptable normality patterns. Given the large sample size and the robustness of linear regression to minor normality violations, the assumption was considered satisfied. The Central Limit Theorem further supports the decision to proceed.

Figure 7.

Histogram of GHRM.

Figure 8.

Histogram of GITA.

Figure 9.

Histogram of GITB.

Figure 10.

Normal Q-Q plot of GHRM.

Figure 11.

Normal Q-Q plot of GITA.

Figure 12.

Normal Q-Q plot of GITB.

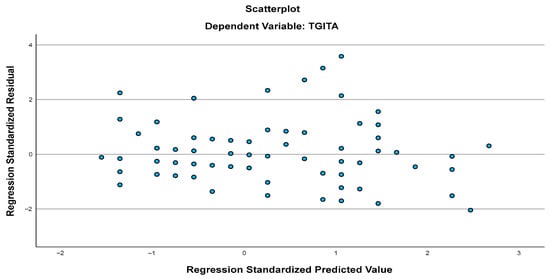

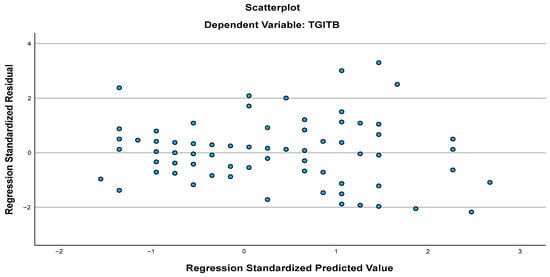

Homoscedasticity was assessed using residual scatterplots (Figure 13 and Figure 14), which showed an even spread of residuals across values of GITA and GITB, confirming consistent variance and meeting the homoscedasticity requirement.

Figure 13.

Scatterplot of GHRM*GITA residuals against regression.

Figure 14.

Scatterplot of GHRM*GITB residuals against regression.

Independence was tested using the Durbin–Watson statistic. Both models (1.848 for GITA and 1.606 for GITB) fell within the acceptable range (1.5–2.5), confirming that residuals were independent (Table 16).

Table 16.

Durbin–Watson Statistics.

In summary, all regression assumptions were adequately met, supporting the model’s validity for further analysis.

4.3. Linear Regression

The assumptions of linear regression were confirmed before proceeding with statistical analyses using SPSS v.28.0.1. The aim was to evaluate the impact of Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) on two dependent variables: Green IT Adoption (GITA) and Green IT Behaviour (GITB). The analyses involved Pearson’s correlation, model summaries, ANOVA, and coefficient interpretation. A significance threshold of α = 0.05 was applied throughout.

- GHRM and GITA

The relationship between Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) and Green IT Attitudes (GITA) was examined using a linear regression analysis. The overall model fit and explained variance are summarised in Table 17, while the statistical significance of the regression model is reported in Table 18. The estimated regression coefficients and effect sizes are presented in Table 19. Together, these results indicate that GHRM is a statistically significant predictor of GITA, explaining a modest but meaningful proportion of variance.

Table 17.

Model summary of GHRM*GITA.

Table 18.

ANOVA for regression residuals of GHRM*GITA.

Table 19.

Coefficients of model GHRM*GITA.

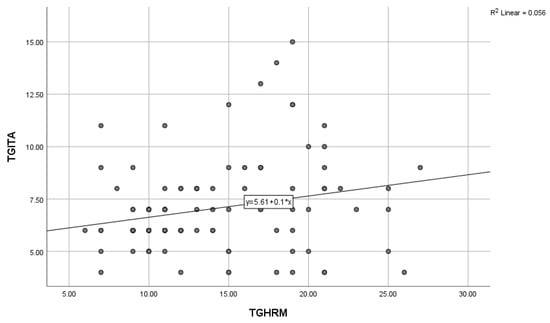

Table 17 presents the model fit statistics for the regression model examining GHRM as a predictor of GITA. The R value (0.236) indicates a positive correlation between predicted and observed GITA scores. The R2 value (0.056) shows that 5.6% of the variance in GITA is explained by GHRM, while the Adjusted R2 (0.047) reflects the variance explained after adjusting for sample size and model complexity. The R² Change (0.056) and F Change (6.488, p = 0.012) demonstrate that adding GHRM results in a statistically significant improvement in model fit.

Table 18 reports the ANOVA results for the overall regression model, testing whether the model explains significantly more variance in GITA than would be expected by chance. The Regression Sum of Squares (28.126, df = 1) represents the variance explained by the model, while the Residual Sum of Squares (476.865, df = 110) reflects unexplained variance. The F statistic (6.488, p = 0.012) confirms that the regression model is statistically significant, indicating that GHRM contributes meaningfully to explaining variance in GITA.

Table 19 presents the regression coefficients for the model evaluating the effect of GHRM on GITA. The unstandardised coefficient (B = 0.101, SE = 0.040) indicates that each one-unit increase in GHRM is associated with a 0.101-unit increase in GITA. The standardised coefficient (Beta = 0.236) confirms a positive effect with moderate strength. The t statistic (2.547, p = 0.012) shows that GHRM is a statistically significant predictor of GITA. These results support the conclusion that GHRM has a positive and meaningful influence on GITA.

- GHRM and GITB

The relationship between Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) and Green IT Behaviour (GITB) was examined using a linear regression analysis. Model fit statistics and the proportion of variance in GITB explained by GHRM are presented in Table 20, the overall statistical significance of the regression model is evaluated using ANOVA results in Table 21, and the estimated regression coefficients and effect sizes are reported in Table 22. Collectively, these results indicate that GHRM is a statistically significant predictor of GITB, explaining a modest but meaningful proportion of variance.

Table 20.

Model summary of GHRM*GITB.

Table 21.

ANOVA for regression residuals of GHRM*GITB.

Table 22.

Coefficients of model GHRM*GITB.

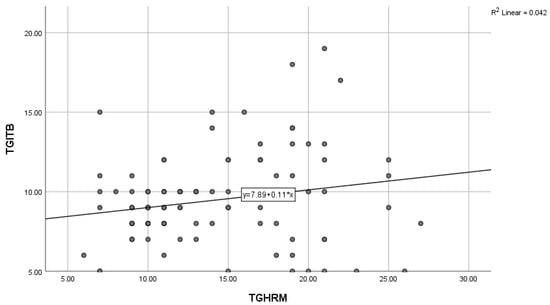

Table 20 presents the model summary for the regression analysis assessing GHRM as a predictor of GITB. The R value (0.204) indicates a positive correlation between predicted and observed GITB scores. The R2 value (0.042) shows that 4.2% of the variance in GITB is explained by GHRM, while the Adjusted R2 (0.033) reflects the model fit after adjusting for sample size and predictor inclusion. The F Change statistic (4.776, p = 0.031) confirms that the model improves significantly when GHRM is included as a predictor.

Table 21 reports the ANOVA results for the overall regression model, testing whether the model explains GITB variance beyond chance. The Regression Sum of Squares (33.759, df = 1) represents the variance explained by the model, and the Residual Sum of Squares (777.518, df = 110) reflects unexplained variance. The F statistic (4.776, p = 0.031) confirms that the regression model is statistically significant, indicating that GHRM contributes meaningfully to explaining variance in GITB.

Table 22 presents the regression coefficients for GHRM predicting GITB. The unstandardised coefficient (B = 0.111, SE = 0.051) indicates that each one-unit increase in GHRM is associated with a 0.111-unit increase in GITB. The standardised coefficient (Beta = 0.204) confirms a positive effect of moderate strength. The t statistic (2.185, p = 0.031) shows that GHRM is a statistically significant predictor, supporting the conclusion that GHRM has a positive and meaningful influence on GITB.

In both models, GHRM emerged as a statistically significant predictor of Green IT attitudes (GITA) and Green IT beliefs (GITB), although it explained only a modest proportion of variance in these outcomes. This limited explanatory power is expected, as employee environmental mindsets are influenced by a range of organisational and individual factors not included in the present model, such as organisational culture, environmental leadership, individual pro-environmental values, and potential mediating mechanisms like environmental motivation or ecological awareness. Nonetheless, the consistent significance across both dependent variables highlights that GHRM plays a meaningful—though partial—role in shaping Green IT mindsets within organisations. Taken together, the results from Table 17, Table 18, Table 19, Table 20, Table 21 and Table 22 and Figure 14 underscore that while GHRM alone cannot account for the full complexity of Green IT cognition, it remains an important organisational lever for fostering sustainability-oriented attitudes and beliefs in the IT sector.

5. Findings

5.1. Research Question 1: High-Level Summary

The first research question asked: Does Green HRM impact Green IT Attitudes in the IT sector? To explore this, the study proposed the following:

- H1: Green HRM positively impacts Green IT Attitudes in the IT industry.

- H0: Green HRM does not impact Green IT Attitudes in the IT industry.

The analysis confirms a statistically significant, though modest, relationship between GHRM and GITA. Specifically, Green HRM explained 5.6% of the variance in GITA, as reflected in the R2 value of the linear regression model, and the model was statistically significant (p = 0.012), as supported by the ANOVA test (F(1,110) = 6.488). While the effect size was small, the findings affirm that GHRM predicts GITA, with a standardised beta coefficient of 0.236—indicating that for every one standard deviation increase in GHRM, there was a corresponding 0.236 increase in GITA.

5.1.1. Finding 1: Model Significance and Relationship Strength

The regression analysis confirms the significance of the relationship, with the model demonstrating a good fit (p = 0.012). The regression slope (β = 0.236) reflects a modest association, and the R2 value (0.056) indicates that GHRM accounted for 5.6% of the variance in Green IT Attitudes. These results suggest that although the impact was not strong, GHRM does play a role in shaping employee attitudes toward Green IT.

5.1.2. Finding 2: Regression Equation and Interpretation

The regression equation derived from the analysis is:

Predicted GITA = 5.614 + (0.101 × GHRM)

Here, the intercept (5.614) represents the baseline level of GITA when GHRM is absent, while the slope (0.101) indicates that each unit increase in GHRM results in a 0.101 increase in GITA. This reinforces the idea that higher levels of Green HRM practices are associated with more favourable attitudes towards Green IT.

This relationship is visually depicted in Figure 15, which presents a scatterplot of GHRM against GITA. The plot demonstrates a linear trend, with data points clustering around the regression line, confirming the model’s explanatory power.

Figure 15.

Regression line on GHRM*GITA.

The figure supports the rejection of the null hypothesis due to the significance level of 0.012.

5.1.3. Finding 3: Theoretical Alignment

The findings align with the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which suggests that attitudes influence behavioural intentions. The modest but significant link between Green HRM and GITA indicates that employees who perceive their organisation as environmentally responsible tend to develop more favourable attitudes towards Green IT.

Similarly, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) supports this result. The perceived usefulness and value of Green HRM likely influence positive attitudes toward Green IT. While the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) posits that beliefs shape attitudes and intentions, this study found limited evidence that GITA leads directly to changes in GITB. However, the conceptual framework (see Figure 3) remains supported in part, confirming the positive influence of GHRM on GITA.

5.2. Research Question 2: High Level Summary

The second research question asked: Does Green HRM impact Green IT Beliefs in the IT sector? The aim was to examine whether environmentally focused organisational practices influence employees’ beliefs about IT’s environmental role. The hypotheses were as follows:

- H2: Green HRM positively impacts Green IT Beliefs in the IT industry.

- H0: Green HRM does not impact Green IT Beliefs in the IT sector.

Regression analysis confirmed a statistically significant relationship between GHRM and GITB, with Green HRM explaining 4.2% of the variance in Green IT Beliefs (R2 = 0.042, p = 0.031). While the effect was small, the result confirms that GHRM is a significant predictor of GITB. The standardised beta coefficient of 0.204 indicates a modest positive association, whereby a one standard deviation increase in GHRM corresponds to a 0.204 increase in GITB.

5.2.1. Finding 4: Model Fit and Variance Explanation

The model summary indicated a statistically significant value (p = 0.031), confirming that introducing GHRM changes the baseline of GITB. The ANOVA test further validated this relationship with F(1,110) = 4.776, p < 0.031, indicating that the model adequately explains variation in GITB. The correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.042) shows that GHRM accounted for 4.2% of the variability in beliefs, slightly lower than its impact on attitudes.

5.2.2. Finding 5: Regression Equation and Visual Interpretation

The derived regression equation was:

Predicted GITB = 7.891 + (0.111 × GHRM)

In this equation, 7.891 represents the intercept or expected GITB score when GHRM is absent, while the slope coefficient 0.111 indicates that for every one-unit increase in GHRM, there is an expected 0.111 unit increase in GITB. This implies that stronger HRM practices focused on sustainability are associated with slightly more positive beliefs about Green IT.

This linear relationship is illustrated in Figure 16, which plots GHRM against GITB. The scatterplot shows a discernible trend, with data points clustered along the regression line, reinforcing the equation’s explanatory value.

Figure 16.

Regression line on GHRM*GITB.

The visual reinforces the finding that small increases in GHRM are associated with proportional increases in employee beliefs about IT’s role in sustainability.

5.2.3. Finding 6: Conceptual and Practical Alignment

The findings for RQ2 support the conceptual framework (see Figure 3) by confirming a positive, statistically significant relationship between GHRM and GITB. Although the effect size was small, the results suggest that as organisations enhance their environmentally focused HR practices, employees’ beliefs about the environmental responsibility of IT also become more positive. The standardised coefficient of 0.111 supports this interpretation, aligning with the theoretical premise that sustainable HR practices can shape employee beliefs toward greener IT practices.

6. Discussion

This quantitative predictive correlation study aimed to explore how Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) practices influence the attitudes and beliefs of IT professionals toward Green IT. Specifically, it investigated whether GHRM could act as a predictor of Green IT Attitudes (GITA) and Green IT Beliefs (GITB). The analysis was guided by two central research questions focusing on the extent of GHRM’s influence on these variables.

Data were collected from 112 participants, as calculated through G*Power 3.1.9.4, yielding a 16.3% response rate. The study adopted a linear regression approach to quantify the strength and direction of the relationships between GHRM and the two dependent variables. The regression models allowed the study to examine how changes in GHRM are associated with shifts in employee attitudes (GITA) and beliefs (GITB), aligning with RQ1 and RQ2, respectively.

The results, as detailed in Section 4.3 include model summaries, ANOVA, and coefficient statistics. Regression equations were derived to reflect the predictive power of GHRM, supported by Figure 4 and Figure 5, which depict scatterplots illustrating the relationship between GHRM and both dependent variables.

Linear regression was selected due to its suitability in identifying and quantifying linear relationships. It helped assess whether increases in GHRM correspond with measurable and consistent changes in GITA and GITB. The regression line generated by the model provided the best fit, minimising discrepancies between the observed and predicted values.

The analysis employed a twofold approach: first, to determine whether GHRM significantly predicts GITA and GITB, and second, to evaluate the strength and significance of these relationships. This approach not only addressed the research hypotheses but also emphasised the practical implications of GHRM in promoting sustainable behaviour and mindsets in the IT sector.

The modest effect sizes identified in this study should be interpreted in light of several organisational and contextual factors noted in the prior Green HRM and Green IT literature. First, Green HRM practices may differ significantly in their depth and quality across organisations, with some firms adopting compliance-oriented or symbolic initiatives that do not translate into meaningful cognitive change among employees. Second, employee exposure to, and awareness of, sustainability-related HR activities may be limited; without consistent reinforcement, such initiatives are unlikely to influence attitudes or beliefs strongly. Third, variations in organisational culture and leadership commitment to environmental values can weaken the internalisation of Green IT mindsets, as cultural signals often outweigh formal HR policies. Finally, an implementation gap may exist between HR-driven sustainability policies and the day-to-day realities of IT work, where operational pressures and technical priorities often overshadow environmental considerations. Taken together, these factors provide a plausible explanation for the relatively weak predictive effect of GHRM on Green IT attitudes and beliefs observed in this study.

Although the regression results indicate statistically significant relationships between Green HRM practices and both Green IT attitudes and Green IT beliefs, the overall explanatory power of the models was modest. This suggests that while Green HRM plays a meaningful role in shaping sustainability-oriented IT mindsets, it represents only one component within a broader set of influences. Green IT attitudes and beliefs are likely shaped by multiple factors beyond HR practices, including organisational culture, leadership commitment, technological infrastructure, regulatory pressures, and individual environmental values. Moreover, cognitive outcomes such as beliefs and attitudes may be indirectly influenced through mediating mechanisms, such as perceived organisational support or environmental self-efficacy, or moderated by contextual variables such as organisational size, industry maturity, or national sustainability norms. The modest variance explained therefore reflects the inherently multifaceted nature of sustainability cognition rather than a weakness of the model, reinforcing the need for more integrative frameworks in future research.

6.1. Combined Real-World Implications

The study’s findings highlight a consistent, albeit modest, influence of Green HRM on both Green IT attitudes and behaviours, suggesting that a unified HR strategy could address both dimensions simultaneously. While the impact is not substantial, this alignment offers practical benefits. For organisations, this means that HR initiatives promoting sustainability may be integrated into existing frameworks without requiring major structural changes. Rather than expecting transformative shifts, companies can treat Green IT outcomes as a supplementary gain.

Importantly, these insights call for a holistic approach. Green IT adoption is not driven by HR alone, it must be supported by technology upgrades, policy reform, and a sustainability-oriented organisational culture. In this context, HR can act as a supportive mechanism rather than the sole driver.

Additionally, cost-efficiency emerges as a practical advantage. Organisations already planning HR updates can embed Green IT objectives with minimal extra investment. Still, setting realistic expectations is crucial, as HR-driven efforts are likely to yield incremental rather than sweeping changes.

For greater effectiveness, targeted interventions such as workshops or focused training on Green IT may offer more value than large-scale HR transformations. The consistent pattern across both attitudes and behaviours also suggests that well-designed initiatives in one area are likely to have a parallel—though modest—effect on the other.

6.2. Integrating Current Findings with Previous Literature

The findings of this study align with the existing literature suggesting that knowledge and awareness gained through HR practices can shape employee beliefs regarding environmental issues. Studies by Amel et al. (2009), Ojo and Raman (2019), and Molla et al. (2014) highlight that Green IT beliefs are influenced by cognitive and experiential factors, including training and exposure. The observed positive relationship between Green HRM and Green IT beliefs affirms the role of HR initiatives—especially green training—in shaping employee perceptions of IT’s environmental implications (Jabbour et al., 2010).

In light of global environmental concerns, organisations are increasingly adopting non-tangible sustainability practices such as Environmental Management Systems and Green HRM to align with sustainable development goals (Sarre & Davey, 2021). This study complements foundational work by Dumont et al. (2017), who found that GHRM fosters green behaviour, and by Ojo et al. (2018), who linked Green IT beliefs with pro-environmental behaviours. Molla et al. (2014) further established the theoretical framework underpinning this study by identifying Green IT attitudes and beliefs as mediators of sustainable behaviour.

The results also support the Theory of Planned Behaviour, indicating that attitudes and beliefs shape behavioural intentions. Although the influence of GHRM was modest—5% for Green IT Attitudes (GITA) and 4% for Green IT Beliefs (GITB)—these findings point to a foundational, though limited, role of HR practices in shaping pro-environmental IT mindsets.

Comparative studies, such as Chaudhary (2020), reported a stronger R2 of 0.32 between GHRM and overall green behaviour. This implies that GHRM’s impact may be more pronounced when indirect effects—mediated through attitudes and beliefs—are considered. Accordingly, this study highlights the need to explore whether GITA and GITB mediate the relationship between GHRM and Green IT behaviour, suggesting that the pathway from HR practices to sustainable outcomes may be indirect but meaningful.

The results also reinforce the Belief–Action–Outcome (BAO) model. The positive association between GHRM and GITA confirms the belief formation stage, suggesting that HR practices can cultivate environmentally conscious attitudes among IT professionals (Molla et al., 2014). The relationship between GHRM and GITB corresponds to the action-formation phase, implying that pro-environmental attitudes may lead to stronger sustainability-related beliefs, echoing Melville’s (2010) argument that beliefs shape sustainable IT actions.

Additionally, the Supplies-Values Fit Theory (Edwards & Lambert, 2007) is supported here. The alignment of organisational “supplies” (i.e., Green HRM practices) with employee values related to sustainability fosters congruent attitudes and beliefs. Thus, organisations promoting green values through HR mechanisms are more likely to nurture employees who resonate with sustainability goals.

Overall, the integration of this study’s statistical results with the established theories and literature enhances our understanding of how Green HRM shapes employee perceptions. Although the direct influence of GHRM on attitudes and beliefs is modest, its strategic significance lies in its potential to indirectly cultivate sustainable IT practices through shifts in employee mindset.

6.3. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study contribute several important theoretical insights to the Green HRM and Green IT literature. First, the study demonstrates that Green HRM practices influence Green IT attitudes and beliefs through distinct cognitive pathways, highlighting the importance of treating attitudes and beliefs as separate psychological constructs rather than as interchangeable. This refinement strengthens cognitive–behavioural frameworks and offers a more granular understanding of how organisational sustainability practices shape employees’ internal evaluations of technology.

Second, the modest explanatory power of the structural models (5% for Green IT attitudes and 4% for Green IT beliefs) suggests that Green HRM is a necessary but insufficient antecedent of Green IT mindsets. This extends existing theoretical models—such as BAO and TPB/TAM—by indicating that additional constructs (e.g., organisational climate, moral norms, leadership support, digital maturity) are required to develop a more comprehensive theoretical account of sustainability-oriented technology behaviour in the IT workforce.

Third, by grounding the analysis within the Australian ICT context, the study provides empirical support for the contextual sensitivity of Green HRM theory. The findings highlight that national and organisational contexts may moderate cognitive responses to Green HRM initiatives, reinforcing calls for more context-specific theorisation in sustainability and technology adoption research.

6.4. Comparative Insights and Contextual Considerations

To strengthen the interpretation of the results, we also compared the findings with international studies conducted in similar IT or sustainability-driven markets. Studies from India, the EU, and Southeast Asia (e.g., Ruchismita et al., 2015; Sakhawalkar & Thadani, 2015; Saifulina et al., 2020) similarly report modest predictive effects of Green HRM on early stage cognitive outcomes such as attitudes and beliefs, suggesting that these constructs are shaped by a wider constellation of organisational and individual factors. This supports our observation that GHRM alone explains only a small proportion of the variance in green IT mindsets.

In line with the reviewer’s suggestion, we acknowledge that mediating or moderating variables—such as organisational culture, individual environmental values, environmental motivation, and green leadership—may play influential roles in shaping Green IT attitudes and beliefs. While these variables fall outside the scope of the present parsimonious framework, their absence may contribute to the low explanatory power observed. We have therefore highlighted them as valuable extensions for future research.

Finally, we recognise that practical misalignments between HR-driven sustainability initiatives and IT operational processes may weaken the effect of GHRM on employee cognition. If green HR policies are not effectively translated into IT workflows—for instance through system guidelines, resource allocation, or technical leadership—employees may not perceive strong reinforcement for green behaviour. This implementation gap offers a plausible contextual explanation for the modest effect sizes identified.

6.5. Alternative Explanations

Acknowledging alternative explanations is essential for scientific integrity. While the study found statistically significant relationships between Green HRM, Green IT attitudes (GITA), and beliefs (GITB), these links may be influenced by other factors. Exploring such alternatives strengthens the research and highlights areas for future study.

Confounding Factors: Unmeasured variables such as organisational culture, job role, personal values, or length of employment may have influenced the results. For example, sustainability-focused cultures may independently affect both Green HRM and employee attitudes. Industry type, geographic location, and generational differences could also act as confounders.

Reverse Causality: Rather than Green HRM shaping employee attitudes and beliefs, it is possible that environmentally conscious individuals are more likely to join organisations with strong sustainability practices, suggesting that the direction of causality could be reversed.

Spurious Relationships: Green HRM might directly influence pro-environmental behaviour, and the observed link with GITA and GITB may simply reflect this broader effect. Without covariance analysis between GITA and GITB, it is difficult to confirm the true nature of their relationship, as highlighted by Ojo et al. (2018).

Sample Characteristics: The study sample primarily includes employees from major cities like Sydney and Melbourne, which are more exposed to sustainability initiatives. This urban bias could skew results and may not reflect attitudes in rural or less environmentally engaged areas.

Organisational Culture: A strong pro-environment culture within an organisation can shape employee attitudes and beliefs, possibly independent of specific HR practices. This culture might be the dominant influence, making it difficult to isolate the effects of Green HRM. Additionally, external societal and media influences may also play a role. Understanding these broader cultural and contextual factors is essential for accurate interpretation.

7. Limitations

While this study provides meaningful insights into the relationship between Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) and Green IT Attitudes (GITA) and Beliefs (GITB), several limitations must be acknowledged. One key limitation is the modest effect size observed. GHRM explained only about 5% of the variance in GITA and 4% in GITB, suggesting that although the relationships were statistically significant, their practical implications may be limited.

The sample size of 112 participants also constrains the generalisability of findings. A larger and more diverse sample would enhance the robustness of results and provide greater confidence in extending the conclusions to the broader IT sector. Moreover, the study examined only three primary variables, GHRM, GITA, and GITB, which may not fully capture the complexity of employee behaviour in relation to sustainability. Including factors such as individual motivations, organisational culture, or external environmental influences could offer a more nuanced understanding.

Additionally, the study relied solely on quantitative methods. While this allowed for statistical analysis, it limited the depth of insight into the participants’ experiences and perceptions. A mixed-methods approach incorporating qualitative techniques, such as interviews or open-ended surveys, could reveal richer context and subtleties behind the data.

Another limitation relates to the use of pre-existing scales for measuring the key constructs. These instruments may not have been perfectly aligned with the specific context of the IT industry, potentially affecting the precision of the results. The reliance on self-reported data further introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, where respondents might have provided answers they perceived as more acceptable rather than fully accurate.

Contextual and temporal factors also pose challenges to external validity. The study was conducted within a specific time frame and organisational setting, which may not reflect the dynamics of other industries or regions. Finally, the cross-sectional design restricts causal interpretation. While associations between variables were identified, it remains unclear whether GHRM directly influenced changes in GITA and GITB, or whether other unmeasured variables or reverse causality may be involved.

Taken together, these limitations underscore the need for cautious interpretation of the findings and highlight important directions for future research.

8. Recommendations

This study’s findings offer several practical pathways for organisations seeking to foster sustainability through Green Human Resource Management (GHRM). Firstly, the evidence suggests that strategically implementing GHRM practices, particularly training and development—can positively influence both Green IT attitudes (GITA) and beliefs (GITB). Educating IT professionals about the value of environmentally responsible practices not only builds awareness but also shapes their behavioural mindset. These programs must be paired with eco-centric workplace policies to reinforce a green organisational culture.

Leadership plays a critical role in this transformation. Empowering sustainable leaders or “green champions” within the organisation can amplify the adoption of GHRM, as these individuals model and inspire environmentally responsible behaviour across teams.

To sustain momentum, companies should leverage GHRM’s influence on GITA and GITB through well-designed communication campaigns that highlight the environmental impact of IT practices. Sharing tangible outcomes—such as reductions in energy consumption or carbon footprint—can reinforce belief in green initiatives. Recognising employees who actively demonstrate positive green behaviours also helps embed sustainability into the organisational ethos.

A broader cultural shift is needed. GHRM should be integrated into the organisation’s values, mission, and everyday operations. Cross-functional collaboration—especially between HR, IT, and sustainability departments—is crucial to embed these practices effectively and consistently.

In light of the post-pandemic work environment, remote and hybrid work models require special attention. Organisations must extend their sustainability efforts to home-based professionals by offering guidelines and support for setting up eco-friendly workspaces. IT departments, in particular, should take the lead in recommending energy-efficient tools and systems to maintain consistency in sustainability practices across locations.

Finally, continuous monitoring and evaluation are essential. Organisations should develop clear performance indicators linked to green practices and regularly assess employee engagement, environmental performance, and compliance with green IT standards. Encouraging open feedback and adapting strategies based on employee insights will enhance both the effectiveness and longevity of Green HRM initiatives.

9. Future Work

Future research should also consider incorporating potential mediating and moderating variables that were beyond the scope of the present model. Factors such as organisational culture, individual environmental values, environmental motivation, and green leadership may influence how Green HRM practices shape employee cognitions toward sustainable IT behaviour. Including these variables in extended models, such as through structural equation modelling or moderated mediation analysis, would offer richer insights into the mechanisms underlying Green IT mindset formation and help explain variation that the current study could not capture.

This study highlights strong links between Green HRM practices and Green IT mindsets, offering a springboard for several future research directions. A key recommendation is to adopt longitudinal studies to observe how GHRM influences IT attitudes and beliefs over time—shedding light on whether such changes are lasting or temporary.

Another avenue is to explore cross-industry comparisons, extending the investigation beyond IT into sectors like manufacturing or healthcare. This can help determine whether the dynamics observed are universal or sector-specific.

Future research should also consider contextual factor, such as culture, gender, and prior knowledge, prior environmental experience or organisational size that may shape how GHRM impacts green IT behaviours. Cultural context, in particular, could play a significant role in how such initiatives are received and internalised by employees.

Targeted studies on specific technologies, such as telecommuting tools or green data centres, can help organisations align GHRM policies with the technologies that matter most. Such research can guide customised training and policy design to support green goals.

Researchers may also examine how GHRM correlates with transparency in sustainability reporting—do organisations with strong green HR practices also disclose their efforts more openly?

Additionally, future studies can assess which training methods are most effective in fostering environmental awareness within IT. Establishing standardised evaluation metrics to measure the impact of GHRM on green mindsets would also help organisations track and refine their strategies.

Finally, with the rise of remote and hybrid work, it is vital to understand how GHRM can shape eco-friendly behaviours in decentralised environments. Investigating the role of technology in reducing the environmental impact of home-based work will be critical in shaping sustainable work cultures.

These research directions offer valuable pathways for advancing the effectiveness of GHRM and promoting a deeper culture of sustainability in organisations.

10. Conclusions

This study highlights the vital role Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) plays in shaping how IT professionals think and feel about environmentally friendly practices. The findings show a clear link: when organisations embrace GHRM, it positively influences both Green IT attitudes (GITA) and beliefs (GITB). In other words, sustainable HR practices help build a workplace culture where employees are more open to and supportive of eco-conscious IT initiatives.

The practical message is simple—companies aiming to go green can start with their HR policies. By embedding sustainability into training, policies, and leadership practices, they can cultivate a workforce that not only supports but actively engages in green IT efforts. This can lead to stronger alignment with broader sustainability goals and more effective implementation of eco-friendly technology solutions.

Beyond individual organisations, these insights feed into the global push for environmental responsibility. Promoting green attitudes and beliefs through HR practices is a step toward reducing the industry’s carbon footprint and advancing sustainability more widely.