Abstract

Microplastics, defined as particles up to 5 mm in size, present a significant environmental and health concern due to their ubiquity, capacity to accumulate in organisms, and potential to cause toxic effects, inflammation, and endocrine disruption. A major challenge in addressing this issue is the lack of a universal method for sample preparation and analysis across different environmental matrices. This study addresses this gap by applying a custom-developed method for isolating microplastics from freshwater, followed by a comparative analysis of their abundance using three techniques: spectral (μ-FTIR) and thermal (TGA and pyro-GC-MS). The study was conducted on water samples from the Ob River near Novosibirsk, a major industrial center in Siberia. Field processing entailed filtering 20 L water volumes through a polyamide fabric with a nominal 100 µm pore size. Subsequent characterization established that the entire population of detected particles fell within the 100 to 500 µm interval. The results revealed microplastic concentrations of 0–10,000 particles/m3 (μ-FTIR), 6–19 mg/m3 (TGA), and 0.47–2.96 mg/m3 (pyro-GC-MS). Critically, the data showed spatially variable contamination, with higher microplastic levels identified near industrial wastewater discharge stations and urban recreational areas.

1. Introduction

Plastic materials are ubiquitous in modern society due to their widespread use in various industries and in everyday life. This leads to the accumulation of plastic wastes in the environment, which undergoes fragmentation through environmental degradation processes, ultimately forming microplastics (MPs)—plastic particles smaller than 5 mm—and nanoplastics (particles < 1 µm) [1].

Extensive studies are being conducted worldwide to quantify plastic waste in coastal seas [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] and open oceans [16,17,18,19,20]. However, freshwater systems are crucial for providing drinking water to people and for agriculture. At the same time, they also act as pathways for the dissemination and sinks of microplastics. MPs enter freshwater bodies from wastewater, atmospheric transport from land, and the degradation of larger plastic waste due to improper waste disposal [21]. These particles enter rivers and then spread throughout aquatic systems. Increasingly, research is being conducted on the detection of MPs in rivers and lakes in Europe [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], Asia [32,33], and America [34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

In global environmental monitoring practice, MPs pollution is quantified using two metrics: the number of particles or mass concentration per unit volume of water or per unit mass of solid matter (for bottom sediment analysis) [41,42]. Fourier transform infrared microscopy (μ-FTIR), Raman microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are used to determine the number of MPs particles [43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Thermal methods, such as thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) [50,51,52,53] and pyrolysis gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry (pyro-GC-MS) [54,55,56,57], are used to determine the mass content of MPs. Scanning electron microscopy combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) allows for the distinction between MPs and inorganic impurities [48]. FTIR and Raman microscopy are non-destructive methods widely used to identify MPs [58,59]. However, the main disadvantage of these methods is the long analysis time. Analysis of samples containing a large number of particles, especially those tens of micrometers in size and smaller, can take up to several days. In addition, the accuracy of the results may be affected by the heterogeneity of MPs, the degree of their degradation, and the presence of surface contaminants or microbial byproducts.

The two main thermal analysis methods currently used for MPs analysis are TGA and pyro-GC-MS. TGA provides a relatively simple yet accurate approach to quantifying the total MPs content in samples. Pyro-GC-MS is used for both identification and quantification of the various polymer types within MPs.

The Ob River is one of the largest and most voluminous river systems in the world, playing a crucial role in regulating climate and maintaining ecosystems in the Northern Hemisphere. Originating in the Altai Mountains, the river crosses Western Siberia before emptying into the Kara Sea. Increasing anthropogenic pressure from industrial and economic activities is degrading the water quality of the Ob River, leading to the accumulation of marine pollutants. This study aimed to assess microplastic contamination in the Ob River and its tributaries around Novosibirsk and Berdsk, using a newly developed sample preparation method followed by analysis with μ-FTIR, TGA, and pyro-GC-MS. A secondary objective was to compare the applicability of these three methods for environmental microplastic analysis. All analyzed particles were within the 0.1–0.5 mm size range.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

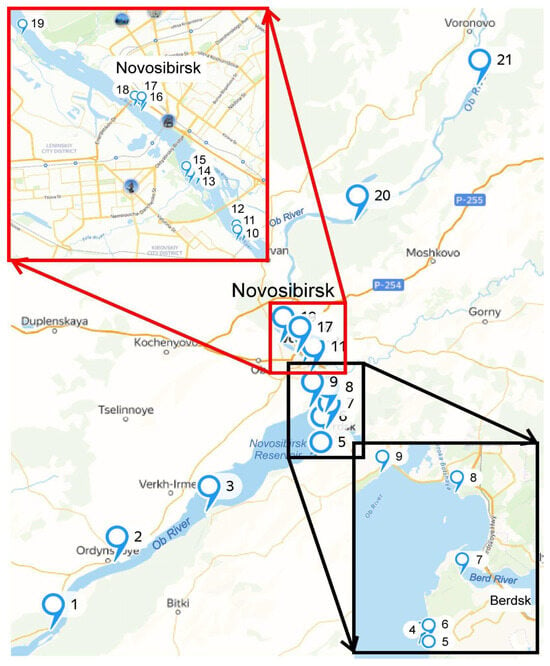

Freshwater samples were collected in August 2023 from 21 stations with varying anthropogenic influences along the Ob River and its tributary, the Berd River, near the cities of Novosibirsk and Berdsk, Russia (Figure 1, coordinates are given in the Table S1). Sampling sites were selected to represent different potential sources of MPs pollution and included: ferry crossings (stations 1–2), recreation centers and beaches (stations 3, 7–9), storm sewer outlets (stations 10–12, 16–18), industrial wastewater discharge stations (stations 4–6), the mouths of small rivers (stations 13–15, 19), and areas near rural settlements (stations 20–21).

Figure 1.

Sampling point distribution.

Samples were labeled as Sample_X_Y, where X denotes the site number and Y indicates the parallel sample number (1 or 2). Duplicate samples (Y = 1, 2) were collected at stations 7–11 to facilitate a direct comparison between the two destructive thermal methods, TGA and pyro-GC-MS.

The sampling procedure involved filtering 20 L of freshwater through a polyamide fabric (100 μm mesh), which was mounted between two metal sieves—an upper sieve with a 5 mm mesh to exclude larger debris. Primarily, this size aligns with the de facto lower limit frequently adopted in the published literature [60], a standard often dictated by the use of conventional plankton nets. This choice is further supported by the operational parameters of our IR microscopy system. To establish a defined upper size boundary and ensure methodological consistency with current guidelines, particles were limited to 5 mm using a sieve, in accordance with ISO 24187:2023 [61]. The polyamide fabric containing the captured sample was then wrapped in aluminum foil, placed in a plastic bag, and transported to the laboratory for analysis [62].

2.2. Chemicals and Materials

Hydrogen peroxide (30 wt% in water), iron (II) sulphate heptahydrate, sodium chloride, and ethanol (95%). All reagents were of at least “Chemically Pure (CP)”. Peracetic acid was obtained as a commercial disinfectant. Its concentration was determined to be 30 wt% by iodometric titration in our laboratory. The heavy liquid sodium heteropolyoxotungstate (density 2.80 g/cm3) was diluted with distilled water to a working density of 1.70 g/cm3. Polyamide fabric (100 μm mesh) and stainless-steel net (26 μm mesh).

A set of stainless-steel sieves (200 mm diameter; mesh sizes: 5 mm, 0.25 mm) and an IKA M20 mill (manufacturer IKA Werke, Staufen, Germany) were used for sample preparation. Organic matrix removal was performed using a Stegler WB-6 6-place water bath (manufacturer Stegler, Shanghai, China). The extent of natural organic matter (NOM) removal was monitored using a Micromed MC-5-ZOOM stereomicroscope (manufacturer Micromed, Shenzhen, China) equipped with a ToupCam UA1000CA (10.0 MP) (manufacturer ToupTek Photonics, Hangzhou, China) digital camera.

2.3. Sample Treatment: Density Separation and Oxidizing Digestion

Sample preparation followed a previously established two-stage protocol [58]. First, the inorganic matrix was removed by density separation using a sodium heteropolyoxo-tungstate solution (density 1.70 g/cm3). Second, NOM was oxidized with peracetic acid at 90 °C, followed by treatment with hydrogen peroxide and iron (II) sulfate (0.05 M). This treatment preserves the mass and structure of most plastics, with the exception of polyamides and polyurethanes.

The purified mixture was filtered through a pre-heated (700 °C) and pre-weighted stainless-steel net (18 mm diameter, 26 μm mesh). The 18 mm diameter was selected to accommodate the crucible sizes for TGA and pyro-GC-MS. After drying, the sample mass was recorded to determine the optimal analysis path: samples > 0.1 mg were analyzed by μ-FTIR/SEM and TGA, while smaller samples were analyzed by μ-FTIR and pyro-GC-MS.

It was noted that highly resistant NOM components, such as chitin and keratin, were not fully dissolved by this method without risking structural damage to the plastics.

2.4. Analytical Methods

The analytical workflow employed complementary techniques to characterize the microplastics: Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) for particle morphology and elemental composition; μ-FTIR spectroscopy for precise polymer identification; Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for the quantitative mass determination of total organic substances (including both natural organic matter and microplastics); and Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (pyro-GC-MS) for the quantitative analysis of specific, common polymers.

2.4.1. SEM-EDS Analysis

SEM-EDS analysis was conducted using a Hitachi SU1000 FlexSEMII microscope (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an Oxford Instruments AzTec One EDX system (Oxfordshire, UK). Samples were mounted without coating with a conductive material and imaged using a backscattered electron (BSE) detector at an accelerating voltage of 15 keV in low vacuum mode (30 Pa) to prevent surface charging. SEM images were obtained using magnifications ranging from ×40 to ×200, depending on the MP particle size. Resolution was 5.0 nm in low vacuum mode and 15 kV accelerating voltage. EDX spectra were accumulated over 15 to 60 s per analysis point. The working distance was about 10 mm.

2.4.2. μ-FTIR Spectroscopy

μ-FTIR analysis was performed using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer coupled with a HYPERION microscope, Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer (Ettlingen, Germany). Particles were located with a 4× visible objective, and spectra were collected using a 15× IR objective. A PIKE MIRacle™ ATR accessory with a single-reflection diamond crystal was used. Spectra were acquired at a resolution of 4 cm−1 with 120 scans over the 4000–630 cm−1 range (microscope) or 256 scans over the 4000–400 cm−1 range (ATR accessory). Spectral processing and polymer identification were performed using OPUS 6.5 software, with reference to a custom IR spectra database maintained at the Novosibirsk Institute of Organic Chemistry SB RAS.

2.4.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

TGA was carried out on a NETZSCH STA 409 instrument (Burlington, MA, USA). Samples were heated at a rate of 10 °C/min in an oxidizing atmosphere (80:20 He:O2) using standard corundum crucibles with vented lids.

2.4.4. Pyro-GC-MS Measurements

Pyro-GC-MS analysis was performed using a micro-furnace pyrolyzer (EGA/Py-3030D, Frontier Laboratories Ltd., Koriyama, Japan) coupled to an Agilent 7890B gas chromatograph and a 5977B single quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Separation was achieved using an Ultra Alloy+-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm; Frontier Laboratories Ltd.) with helium as the carrier gas. Detailed method parameters are provided in the Supplementary Information (SI, Table S2).

Qualitative and quantitative analysis of polymers was conducted using a commercial microplastic standard (Frontier Laboratories Ltd.; SI, Figure S1, Table S3). Calibration curves were constructed from 1 mg aliquots of the standard and its 10×, 20×, and 50× dilutions by silicone dioxide. Polymers were identified and quantified based on characteristic pyrolysis products, with their representative ions and retention times listed in SI, Table S4.

2.5. Quality Assurance and Quality Control

Stringent measures were implemented to prevent airborne contamination. All procedures were conducted inside fume cupboards, and samples were covered with aluminum foil during transport. Personnel wore 100% cotton lab coats, and plasticware was replaced with glass or metal alternatives where possible.

All equipment was meticulously cleaned: glassware was rinsed thrice with bidistilled water (pre-filtered through a 0.7 μm glass fiber filter, pre-heated to 400 °C), and stainless-steel filters were washed with filtered distilled water and heated in a muffle furnace at 400 °C. All reagents (acids, heavy liquid, etc.) were filtered through a glass fiber filter with a pore size of 0.7 µm. All reagents were screened for microplastic contamination via pyrolytic gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (pyro-GC-MS). Following filtration, the reagents were confirmed to be contaminant-free and thus suitable for sample preparation.

Procedural blanks were processed alongside the samples by substituting 1000 mL of distilled water for the sample and following the identical extraction and purification workflow. These blanks were subsequently analyzed by pyro-GC-MS to account for any background contamination (results discussed in the following section).

3. Results

Our analysis of MPs samples revealed several methodological limitations that significantly impact the accuracy of MPs content assessment.

3.1. Non-Destructive Analysis Methods

Non-destructive methods, which preserve the sample, primarily include microscopy techniques such as optical microscopy, SEM, μ-FTIR, and micro-Raman spectroscopy.

3.1.1. Optical Microscopy

Optical microscopy is used for counting MPs particles and determining their size, shape, and color. However, as it provides no chemical composition data, reliance on this method alone can lead to misidentification between MPs and residual NOM from sample preparation.

3.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

SEM is a non-destructive method for examining the surface morphology of microplastics, their degree of degradation, and particle size [63]. When combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, it enables rapid elemental analysis. This method readily identifies inorganic particles (e.g., silicates, carbonates) by their characteristic elemental signatures (Si, Mg, Ca, Na), allowing their exclusion from microplastic counts.

In our study, we found that SEM-EDS is less effective for identifying organic polymers than FTIR and Pyro-GC-MS. Common plastics such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS), which are composed solely of carbon and hydrogen, yield identical EDS spectra. Although the presence of oxygen may indicate polymers such as polyesters or polycarbonates, it is not a definitive indicator, as organic matter such as plant residues also contains oxygen. Similarly, the presence of nitrogen could indicate polyurethane or polyamide, but these polymers were degraded during peracetic acid treatment, and the nitrogen-containing polymers in our samples were proteins or chitin from zooplankton, which are difficult to remove during sample preparation (see Figures S2 and S3).

Furthermore, obtaining SEM images and EDS data for individual particles was labor-intensive and time-consuming. Given the low information yield of this method for identifying polymers in complex environmental matrices, we abandoned its use for natural water analysis in favor of more informative methods.

3.1.3. μ-FTIR Spectroscopy

μ-FTIR is a widely used non-destructive method for polymer identification in environmental samples. It is typically applied to particles smaller than 500 μm. As has been established in our study of MP particles of various sizes, particle thickness was a critical parameter. In reflection mode, the resulting spectrum is a combination of transmission and reflection. Thin particles produced spectra similar to transmission mode, while thick particles exhibited dominant reflection components that distorted spectral shapes. Additionally, the presence of inorganic fillers and additives significantly altered the IR spectrum of MP particles, complicating identification.

Analysis determined that all recovered particles fell within a size range of 100 µm to 500 µm.

3.2. Thermal Analysis Methods

3.2.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis

TGA determines the total polymeric content in a sample by measuring mass loss upon thermal decomposition. A key advantage is that mineral particles (e.g., dust, sand, clay) do not contribute to the mass loss in the relevant temperature range, thus not interfering with the MPs quantification. However, sample preparation must effectively remove NOM, as they also decompose upon heating and contribute to the mass loss. For TGA, we used filters preheated to 800 °C to remove contaminants.

3.2.2. Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

Pyro-GC-MS involves the thermal decomposition of polymers in an inert atmosphere, generating low-molecular-weight products characteristic of specific polymers. We used a commercial calibration standard (MPs-SiO2, Frontier Lab) to establish linear calibration curves with satisfactory correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.99). Procedural blanks were analyzed to assess background contamination, with the limit of reliable detection set at twice the blank value (see SI, Table S5).

This method is advisable for use with sample masses below 100 μg. Methodological constraints include the small sample capacity (crucible diameter = 4 mm; volume ≈ 100 μL), which may lead to column overloading when analyzing large particles. A significant limitation is that quantitative analysis is restricted to polymers for which calibration standards are available (e.g., the 11 polymers in the Frontier Lab standard). Other polymers can only be identified qualitatively. The method also requires an inorganic filter, such as pre-heated fiberglass or metal filters. We found metal filters superior due to their higher mechanical strength, as fiberglass filters often tore during handling and placement into the pyrolyzer.

3.3. MPs Abundances: Total Particle Number and Mass Concentration

Water samples from the Ob River were collected from anthropogenically impacted areas (point 7–9, 10–11). After sample preparation, MPs were accumulated on metal filters, and their presence was confirmed by μ-FTIR. The prepared samples were systematically divided into two groups based on post-preparation filter weight. This approach was designed to align each sample with the most suitable analytical technique, thereby optimizing data quality.

Pyro-GC-MS: Samples weight of less than 0.1 mg were selected for this analysis. This threshold was established to prevent column overloading, a technical limitation that could compromise the chromatographic resolution and quantification accuracy for this highly sensitive method.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Samples exceeding the 0.1 mg weight threshold were allocated for TGA. This group consisted of samples containing a higher mass of particulate material, which included both relatively larger microplastic particles and non-plastic organic matter. Thus, it was established that in these samples, microplastic particles identified according to the μ-FTIR data were 0.4–0.5 mm in size (for pyro-GC-MS analysis particles were less). The non-plastic fraction comprised organic particles whose geometry and optical properties rendered them unsuitable for definitive identification via IR spectroscopy. A key limitation of the Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) method in this context is its inability to independently quantify the mass of plastic versus that of natural organic matter. Even with known microplastic particle sizes, accurately determining their mass—and subsequently deriving the mass of natural organic matter—remains unfeasible under the current analytical framework. This represents a primary constraint in applying the TGA method to this particular analytical challenge. Nevertheless, it should be noted that if complete (100%) removal of NOM is achieved, TGA can be effectively utilized to determine the total microplastic content within a sample.

MPs particles of various types were identified in these water samples. Table 1 compares the total sample mass on the filter with the mass loss recorded by TGA. The mass loss was consistently lower than the total sample mass, indicating the presence of inorganic particles and fillers. The TGA mass loss represents the total weight of organic suspended particles, including both MPs and any residual NOM. Based on this, the concentration of organic suspended particles in the Ob River water was determined to be in the range of 6–19 mg/m3.

Table 1.

Determination of MPs by TGA and μ-FTIR.

Table 2 presents the particle counts obtained by μ-FTIR and the mass of MPs determined by pyro-GC-MS in samples from the Ob River. To compare pollution levels in Russian and global river systems, we extrapolated our results to a standardized water volume of 1 m3, while the actual sample volume was 20 L.

Table 2.

MPs content in samples determined by μ-FTIR microscopy and pyro-GC-MS.

As can be seen from the compared data, the number of MPs particles is not a characteristic value due to the different particle sizes in the sample. Pyro-GC-MS is suitable for both the qualitative and quantitative determination of MPs content in natural samples based on characteristic pyrolysis products of the polymers. This method demonstrates higher sensitivity compared to FTIR microscopy. Therefore, within individual samples, pyro-GC-MS demonstrated the ability to identify a broader diversity of polymer types compared to μ-FTIR. We recognize that μ-FTIR, supported by extensive spectral libraries, possesses a fundamentally wider theoretical range of polymer identification. It is also worth noting that this method requires a preliminary assessment of the amount of MPs in the sample using microscopy or weighing. Based on the results of this assessment, it is possible to select the chromatography mode more accurately to avoid overloading the column or detector with the amount of substance. In our study, overload fronting peaks were observed for a number of substances. Therefore, some data are presented in Table 2 as “>LOQ” (Limit of Quantification), and the numerical values of these limits are presented in Table S5.

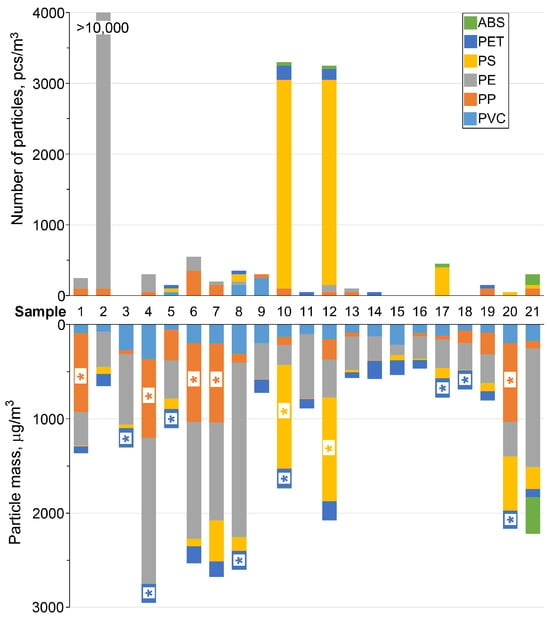

The analytical results indicate that 88% of the MPs particles identified by μ-FTIR belonged to six polymer types that were also targeted for pyro-GC-MS analysis, enabling a direct comparison between the two methods (Figure 2). Overall, μ-FTIR identified 16 different polymer types, including PE, PP, PS, PVC, ABS, PET, PAN, PA, PU, alkyd resins, polysiloxane, phenol-formaldehyde resins, and various acrylates (Table 2). The order of abundance by particle count, based on μ-FTIR, was: PE (55%) > PS (33%) > PP (6%) > PET (3%) > PVC (2%) > ABS (2%).

Figure 2.

Particle count (μ-FTIR) and approximate MPs mass (pyro-GC-MS). The * symbol denotes polymers above the limit of quantification (LOQ).

Pyro-GC-MS analysis confirmed PE as the most abundant polymer, detected in all samples. The highest PE particle count (>10,000 particles/m3) was recorded at point 2; however, this site did not show the highest mass concentration due to the small size of the particles, which were approximately 100 µm thin films. The highest mass concentrations of PE were found at stations 4 and 6 (industrial wastewater) and 7–8 (beach areas). While the exact percentage of PE could not be calculated due to column overloading from other polymers, it is unequivocally the predominant pollutant in the Ob River.

PMMA, detected at less than 1% by weight and not identified by μ-FTIR, was excluded from further comparative analysis. Figure 2 shows that the highest levels of PS were found at stations 10 and 12, which caused column overload in pyro-GC-MS and corresponded to the highest PS particle counts in μ-FTIR. The data also suggest that PP is likely the second most abundant polymer, with the highest concentrations detected at sampling stations 4, 6, and 7.

Interestingly, MPs pollution levels near rural settlements were higher than at storm drain outlets in central Novosibirsk, likely due to an efficient stormwater treatment system prior to discharge. Furthermore, the mouths of small tributaries were found to be sources of low MPs concentrations compared to stormwater outlets, industrial wastewater, and beach areas.

The comparison between μ-FTIR and pyro-GC-MS results does not always show identical trends in contamination levels. While some samples exhibit satisfactory reproducibility, others show significant variance. This discrepancy occurs because a single large particle can dominate the mass concentration, while a multitude of small particles may contribute insignificantly to the total mass. Additionally, the resolution limit of the μ-FTIR microscope may have led to an underestimation of fine fibers, potentially affecting the reported abundance of polymers like PA and PET, which are often present in this form [64].

4. Discussion: Comparative Analysis and Methodological Considerations

A comprehensive analysis of environmental microplastics involves a multi-stage workflow encompassing sampling, sample preparation (including the separation of microplastic particles from inorganic and natural organic matrices), and the subsequent qualitative and quantitative analysis of the extracted particles. Globally, researchers employ a diverse array of techniques at each stage, with methodological choices being contingent upon the sample matrix, specific research objectives, and available resources. This inherent methodological variability presents a significant challenge. It leads to inconsistencies in key parameters, including the reported size range of analyzed particles, the identified polymer composition, and the units used to present results. Consequently, direct comparison and synthesis of data from different studies remain problematic, hindering a clear and consolidated understanding of global environmental microplastic contamination. To address this critical gap, the development of efficient, universal extraction protocols, followed by the standardization of the entire analytical procedure—from initial sampling to final data reporting—is urgently needed. The establishment of such standardized frameworks is a prerequisite for generating reliable, comparable, and high-quality data. This, in turn, is fundamental for accurately assessing pollution levels, tracing sources, predicting ecological and human health impacts, and ultimately informing effective monitoring and mitigation strategies for this pervasive environmental contaminant.

The spatial distribution of microplastic contamination points directly to anthropogenic sources. The maximum concentrations (number of MPs) were measured at stations 2, 10, and 12, which align with known effluent discharges from wastewater treatment and stormwater systems. Complementary data from pyro-GC-MS highlights additional hotspots at stations 4 and 6, located proximate to a metal and plastics manufacturing facility, indicating probable industrial contribution. Elevated levels at beach sites (stations 7 and 8) further underscore the pervasive nature of plastic pollution in areas of high recreational use.

The MPs concentrations reported in this study—up to >10,000 pcs/m3 (by μ-FTIR) and 470 to >2955 μg/m3 (by pyro-GC-MS)—are substantially higher than those in many published reports (Table 3). For instance, studies on the Ob (north of Novosibirsk) and Tom Rivers, using a 300 μm Manta trawl, reported concentrations of 26.5–114 pcs/m3 and 29.2–57.2 pcs/m3, respectively [65]. This discrepancy is largely attributable to our use of 100 μm polyamide filters, which capture a significantly greater number of small particles. The gravimetric mass determination in the former study may also be inflated by undissolved NOM.

Table 3.

Microplastic abundances of river water around the world.

A similar pattern emerges from other regional studies. Research on the Volga River [27] reported 0.16–4.10 particles/m3 (40 to 1290 µg/m3). The average MPs concentration was 0.90 pcs/m3 (210 µg/m3). In contrast, studies of the Northern Dvina River, a major Arctic waterway, reported significantly lower concentrations of 0.004–0.010 particles/m3 (20–40 µg/m3) [28].

Similar MPs concentrations was reported in European rivers. For instance, in the Ofanto River in southeast Italy [23], MPs abundances ranged from 0.9 to 13 pcs/m3 measured in October 2017 and May 2018, respectively. Microplastic concentrations in Amsterdam canals have been assessed in multiple studies. Early screening using microscopy reported high concentrations of 48,000–187,000 pcs/m3 [29], while a more recent comprehensive study employing μ-FTIR imaging and pyro-GC-MS measured concentrations of 16–1707 pcs/m3 and 8.5–754 μg/m3, respectively [30]. In contrast, exceptionally low MPs concentrations of 0.04–9.97 pcs/m3 were recorded in the Rhine River by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy [24].

Analysis of the Seine River in Paris revealed microplastic concentrations of up to 108 particles/m3, with fibers constituting the dominant morphological type identified in the samples [22]. It should be noted, however, that this study targeted particles within a size range of 100–5000 μm. In Dutch riverine surface waters, MPs number concentrations between 67 and 11,532 pcs/m3 were detected [66]. In this study, particles > 20 µm were identified using µ-FTIR and automated image analysis. Microplastics in the Elbe River estuary were assessed using three different sampling methods [25]. A Continuous Flow Centrifuge (CFC) recorded values from 193 to 2072 particles/m3, a Hydrocyclone (HC) from 269 to 574 pcs/m3, while grab sampling of bulk water in glass bottles detected concentrations of up to 39,458 pcs/m3 in the influent. Higher concentrations (up to 95,800 pcs/m3) were reported in an urban canal in Berlin [67], although their sampling may not be representative of pollution levels in large rivers. There are also data that show the detection of significant concentrations of 483–967 pcs/m3 in Tibetan rivers [33] and 58–1265 pcs/m3 in the Antua River in Portugal [31].

The observed discrepancies, spanning several orders of magnitude, cannot be explained by pollution gradients alone. The key differentiator is methodology. Unlike studies employing 300 μm Manta trawls [65], our use of 100 μm polyamide filters enabled capture of substantially more small particles. More fundamentally, approaches relying on visual identification or gravimetric analysis face critical limitations—morphological characteristics cannot reliably distinguish synthetic polymers from NOM, while combustion methods merely quantify total thermo-resistant mass without polymer discrimination.

In contrast, our integrated approach combines μ-FTIR for definitive chemical identification and pyro-GC-MS for accurate mass quantification. This allows for reliable polymer composition analysis of minute particles and effectively excludes NOM, eliminating a major source of error. Our findings show strong concordance with studies using similarly rigorous methods, such as [66], who also used fine filtration (20 μm) and μ-FTIR, and found that 67% of MPs were under 100 μm.

In conclusion, the comparison of our results with the literature underscores the urgent need for unified, standardized protocols for MPs monitoring. Such standards must mandate (1) chemical identification of particles to prevent misclassification and (2) comprehensive analysis that includes the small fraction (<100 μm), which constitutes a major portion of MPs pollution. Only through such rigorous, integrated approaches can the scientific community generate reliable and comparable data to accurately assess the global impact of microplastics.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the features of quantitative analysis of MPs in aqueous environmental samples from the Ob River, employing three established analytical techniques: μ-FTIR, TGA, and pyro-GC-MS.

Based on the results obtained using μ-FTIR spectroscopy, the following conclusions were drawn: μ-FTIR represents a non-destructive analytical technique capable of both polymer identification and quantitative enumeration of MPs particles exceeding 100 μm in size. In the present study, the lower size threshold was set at 100 μm due to two methodological constraints: (1) the 100 μm mesh size of the polyamide sampling fabric, and (2) the substantial technical challenges associated with visual identification and analysis of sub-100 μm particles using μ-FTIR microscopy.

The detection of MPs by TGA requires complete purification of the sample from natural organic matter. Pyro-GC-MS enables both qualitative identification and quantitative determination of polymers in the form of MPs in environmental samples through detection of characteristic pyrolysis products. The main disadvantage of the method is its destructiveness.

Comparative analysis revealed MPs concentrations in the Ob River of 6–19 mg/m3 (TGA) versus 0.7–2.9 mg/m3 (pyro-GC-MS). This discrepancy arises from those factors: (1) inherently larger sample weights for TGA and possible residual NOM retained during sample preparation, and (2) quantification by pyro-GC-MS was limited to the polymer types with available calibration standards and column overloading in the case of large particle analysis. Notably, μ-FTIR detected additional polymer classes (alkyd resins, polyurethanes, polyacrylates, polysiloxanes, polyamides) whose pyrolysis products were not analyzed.

The generation of reliable and comparable environmental data on microplastic contamination necessitates the adoption of standardized and robust analytical approaches. This study underscores the critical importance of selecting an analytical method appropriate to the specific research objective. Our findings illustrate, for instance, that a comprehensive characterization of microplastic pollution within a sample is best achieved through a complementary, multi-method strategy—such as the combined use of spectroscopic (e.g., IR microscopy) and thermo-analytical (e.g., pyro-GC-MS) techniques.

Furthermore, when considering the development of a unified international methodology, thermochemical methods like pyro-GC-MS offer distinct advantages for standardization. This method provides highly reproducible quantitative data for common polymers and minimizes operator-dependent variability, thereby serving as a strong candidate for a core, harmonized analytical protocol.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/environments13010050/s1. Figure S1. Frontier Lab microplastic standard (Frontier Laboratories Ltd., Fukushima, Japan) SEM image. Figure S2. SEM images of wood particles (a) and alkyd paint (b), their EDS and IR spectra. Figure S3. SEM images of protein (a) and chitin (b), their EDS and IR spectra. Table S1. Coordinates of sampling points. Table S2. Pyro-GC-MS parameters. Table S3. Content of polymers in Frontier Lab microplastic standard and in diluted forms. Table S4. Selected indicator ions of pyrolysis products of different polymers at 600 °C; M/z masses highlighted in bold were used for quantification; polystyrene (PS), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene (PE), acrylo-nitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). Table S5. Summary of the quantitation parameters.

Author Contributions

Y.S.S.: conceptualization, methodology, verification, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing. E.V.K. and I.K.S.: methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing. A.E.O. and D.I.S.: investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing. A.A.N.: investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing. A.V.S.: methodology, writing—reviewing and editing. D.N.P.: conceptualization, supervision, writing—reviewing and editing. E.G.B.: supervision, writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 25-24-20132.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information. Initial data (microphotographs, IR- and EDS spectra, pyrograms, TGA data) were generated at NIOCH SB RAS.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the Government of the Novosibirsk Region, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, and the Multi-Access Chemical Research Center SB RAS for spectral measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MP | Microplastic |

| μ-FTIR | Micro-Fourier transform infrared microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| pyro-GC-MS | Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| NOM | Natural Organic Matter |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| EVA | Ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer |

| ABS | Acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PA | Polyamide |

References

- State Water Resources Control Board. Adoption of Definition of ‘Microplastics in Drinking Water’: Resolution No. 2020-0021. Available online: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/board_decisions/adopted_orders/resolutions/2020/rs2020_0021.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Zobkov, M.B.; Esiukova, E.E.; Zyubin, A.Y.; Samusev, I.G. Microplastic content variation in water column: The observations employing a novel sampling tool in stratified Baltic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, S.; Garm, A.; Huwer, B.; Dierking, J.; Nielsen, T.G. No increase in marine microplastic concentration over the last three decades—A case study from the Baltic Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayomi, O.A.; Range, P.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Obbard, J.P.; Almeer, S.H.; Ben-Hamadou, R. Microplastics in coastal environments of the Arabian Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçer, S.; Artüz, O.B.; Demirkol, M.; Artüz, M.L. First report of occurrence, distribution, and composition of microplastics in surface waters of the Sea of Marmara, Turkey. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baini, M.; Fossi, M.C.; Galli, M.; Caliani, I.; Campani, T.; Finoia, G.; Panti, C. Abundance and characterization of microplastics in the coastal waters of Tuscany (Italy): The application of the MSFD monitoring protocol in the Mediterraneand Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajšt, T.; Bizjak, T.; Palatinus, A.; Liubartseva, S.; Kržan, A. Sea surface microplastics in Slovenian part of the northern Adriatic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 113, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimali Koongolla, J.; Andrady, A.L.; Terney Pradeep Kumara, P.B.; Gangabadage, C.S. Evidence of microplastics pollution in coastal beaches and waters in southern Sri Lanka. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; He, H.; Liu, M.; Li, S.; Tang, G.; Wang, W.; Huang, P.; Wei, G.; Lin, Y.; Chen, B.; et al. Lost but can’t be neglected: Huge quantities of small microplastics hide in the South China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Tan, S.; Kang, Z.; Yu, X.; Lan, W.; Cai, L.; Wang, J.; Shi, H. Microplastic pollution in the Maowei Sea, a typical mariculture bay of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincinelli, A.; Scopetani, C.; Chelazzi, D.; Lombardini, E.; Martellini, T.; Katsoyiannis, A.; Fossi, M.C.; Corsolini, S. Microplastic in the surface waters of Ross Sea (Antarctica): Occurrence, distribution and characterization by FTIR. Chemosphere 2017, 175, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, A.; Hecq, J.H.; Galgani, F.; Voisin, P.; Collard, F.; Goffart, A. Neustonic microplastic and zooplankton in the North Western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collignon, A.; Hecq, J.; Galgani, F.; Collard, F.; Goffart, A. Annual variation in neustonic micro- and meso-plastic particles and zooplankton in the Bay of Calvi (Mediterranean-Corsica). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 79, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lucia, G.A.; Caliani, I.; Marra, S.; Camedda, A.; Coppa, S.; Alcaro, L.; Campani, T.; Giannetti, M.; Coppola, D.; Cicero, A.M.; et al. Amount and distribution of neustonic micro-plastic off the western Sardinian coast (Central-Western Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 100, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutroneo, L.; Reboa, A.; Besio, G.; Borgogno, F.; Canesi, L.; Canuto, S.; Dara, M.; Enrile, F.; Forioso, I.; Greco, G.; et al. Microplastics in seawater: Sampling strategies, laboratory methodologies, and identification techniques applied to port environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8938–8952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, K.; Lenz, R.; Stedmon, C.A.; Nielsen, T.G. Abundance, size and polymer composition of marine microplastics ≥ 10 μm in the Atlantic Ocean and their modelled vertical distribution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desforges, J.P.W.; Galbraith, M.; Dangerfield, N.; Ross, P.S. Widespread distribution of microplastics in subsurface seawater in the NE Pacific Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 79, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.S.; Kregting, L.; Boots, B.; Blockley, D.J.; Brickle, P.; da Costa, M.; Crowley, Q. A comparison of sampling methods for seawater microplastics and a first report of the microplastic litter in coastal waters of Ascension and Falkland Islands. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, T.; Van der Meulen, M.D.; Devriese, L.I.; Leslie, H.A.; Huvet, A.; Frère, L.; Robbens, J.; Vethaak, A.D. Microplastic baseline surveys at the water surface and sediments of the North-East Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, D.; La Russa, D.; Barberio, L. Pollution Has No Borders: Microplastics in Antarctica. Environments 2025, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Fan, C. Fate and Impacts of Microplastics in the Environment: Hydrosphere, Pedosphere, and Atmosphere. Environments 2023, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Rocher, V.; Saad, M.; Renault, N.; Tassin, B. Microplastic contamination in an urban area: A case study in Greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Stock, F.; Massarelli, C.; Kochleus, C.; Bagnuolo, G.; Reifferscheid, G.; Uricchio, V.F. Microplastics and their possible sources: The example of Ofanto river in southeast Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, T.; Hauk, A.; Walter, U.; Burkhardt-Holm, P. Microplastics profile along the Rhine River. Sci. Rep. 2016, 5, 17988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, L.; Zimmermann, T.; Primpke, S.; Fischer, D.; Gerdts, G.; Pröfrock, D. Comparison and uncertainty evaluation of two centrifugal separators for microplastic sampling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.K.; Paglialonga, L.; Czech, E.; Tamminga, M. Microplastic pollution in lakes and lake shoreline sediments e a case study on Lake Bolsena and Lake Chiusi (central Italy). Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisina, A.A.; Platonov, M.M.; Lomakov, O.I.; Sazonov, A.A.; Shishova, T.V.; Berkovich, A.K.; Frolova, N.L. Microplastic Abundance in Volga River: Results of A Pilot Study in Summer 2020. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 14, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, I.; Lokhov, A.; Belesov, A.; Kozhevnikov, A.; Pakhomova, S.; Berezina, A.; Frolova, N.; Kotova, E.; Leshchev, A.; Wang, X.; et al. Assessment of Seasonal Variability of Input of Microplastics from the Northern Dvina River to the Arctic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 175, 113370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; Brandsma, S.H.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Vethaak, A.D. Microplastics, En Route: Field Measurements in the Dutch River Delta and Amsterdam Canals, Wastewater Treatment Plants, North Sea Sediments and Biota. Environ. Int. 2017, 101, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefiloglu, F.Ö.; Stratmann, C.N.; Brits, M.; van Velzen, M.J.M.; Groenewoud, Q.; Vethaak, A.D.; Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Lamoree, M.H. Comparative microplastic analysis in urban waters using μ-FTIR and Py-GC-MS: A case study in Amsterdam. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 351, 124088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.O.; Abrantes, N.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Nogueira, H.; Marques, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Spatial and temporal distribution of microplastics in water and sediments of a freshwater system (Antuã River, Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Xue, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Li, D.; Shi, H. Microplastics in taihu lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 216, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Yin, L.; Li, Z.; Wen, X.; Luo, X.; Hu, S.; Yang, H.; Long, Y.; Deng, B.; Huang, L.; et al. Microplastic pollution in the rivers of the tibet plateau. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaker, P.L.; Baldwin, A.K.; Corsi, S.R.; Mason, S.A.; Reneau, P.C.; Scott, J.W. Vertical distribution of microplastics in the water column and surficial sediment from the Milwaukee river basin to lake Michigan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 12227–12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Luna, R.A.; Oquendo-Ruiz, L.; García-Alzate, C.A.; Arana, V.A.; García-Alzate, R.; Trilleras, J. Identification, abundance, and distribution of microplastics in surface water collected from Luruaco lake, low basin Magdalena river, Colombia. Water 2023, 15, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.K.; Corsi, S.R.; Mason, S.A. Plastic Debris in 29 Great Lakes Tributaries: Relations to Watershed Attributes and Hydrology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10377–10385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wontor, K.; Olubusoye, B.S.; Cizdziel, J.V. Microplastics in the Mississippi River System during Flash Drought Conditions. Environments 2024, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, N.; Miller, J.; Orbock-Miller, S. Quantification and Categorization of Macroplastics (Plastic Debris) within a Headwaters Basin in Western North Carolina, USA: Implications to the Potential Impacts of Plastic Pollution on Biota. Environments 2024, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Mason, S.; Wilson, S.; Box, C.; Zellers, A.; Edwards, W.; Farley, H.; Amato, S. Microplastic pollution in the surface waters of the laurentian great lakes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 77, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, E.; Minor, E.C.; Schreiner, K. Microplastic abundance and composition in Western lake superior as determined via microscopy, Pyr-GC/MS, and FTIR. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1787–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.; Dehal, A.; Kumar, A.R. Microplastics in Soils and Sediments: A Review of Characterization, Quantitation, and Ecological Risk Assessment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filella, M. Questions of size and numbers in environmental research on microplastics: Methodological and conceptual aspects. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Monnot, M.; Sun, Y.; Asia, L.; Wong-Wah-Chung, P.; Doumenq, P.; Moulin, P. Microplastics in different water samples (seawater, freshwater, and wastewater): Methodology approach for characterization using micro-FTIR spectroscopy. Water Res. 2023, 232, 119711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willans, M.; Szczecinski, E.; Roocke, C.; Williams, S.; Timalsina, S.; Vongsvivut, J.; McIlwain, J.; Naderi, G.; Linge, K.L.; Hackett, M.J. Development of a rapid detection protocol for microplastics using reflectance-FTIR spectroscopic imaging and multivariate classification. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2023, 2, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-L.; Thomas, K.V.; Luo, Z.; Gowen, A.A. FTIR and Raman imaging for microplastics analysis: State of the art, challenges and prospects. Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 119, 115629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käppler, A.; Fischer, D.; Oberbeckmann, S.; Schernewski, G.; Labrenz, M.; Eichhorn, K.-J.; Voit, B. Analysis of environmental microplastics by vibrational microspectroscopy: FTIR, Raman or both? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 8377–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekudewicz, I.; Dąbrowska, A.M.; Syczewski, M.D. Microplastic pollution in surface water and sediments in the urban section of the Vistula River (Poland). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 143111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girão, A.V. SEM/EDS and optical microscopy analysis of microplastics. In Handbook of Microplastics in the Environment; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dąbrowska, A.; Mielańczuk, M.; Syczewski, M. The Raman spectroscopy and SEM/EDS investigation of the primary sources of microplastics from cosmetics available in Poland. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansa, R.; Zou, S. Thermogravimetric analysis of microplastics: A mini review. Environ. Adv. 2021, 5, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorolla-Rosario, D.; Llorca-Porcel, J.; Pérez-Martínez, M.; Lozano-Castelló, D.; Bueno-López, A. Study of microplastics with semicrystalline and amorphous structure identification by TGA and DSC. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Razeghi, N.; Yousefi, M.R.; Podkościelna, B.; Oleszczuk, P. Microplastics identification in water by TGA–DSC Method: Maharloo Lake, Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 67008–67018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.T.; Sogut, E.; Uysal-Unalan, I.; Corredig, M. Quantification of polystyrene microplastics in water, milk, and coffee using thermogravimetry coupled with Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (TGA-FTIR). Chemosphere 2024, 368, 143777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, F.; Wang, J.; Sun, C.; Song, J.; Wang, W.; Pan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Yan, J. Influence of interaction on accuracy of quantification of mixed microplastics using Py-GC/MS. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedecke, C.; Dittmann, D.; Eisentraut, P.; Wiesner, Y.; Schartel, B.; Klack, P.; Braun, U. Evaluation of thermoanalytical methods equipped with evolved gas analysis for the detection of microplastic in environmental samples. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2020, 152, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, N.; Anquetil, C.; Dris, R.; Gasperi, J.; Tassin, B.; Derenne, S. Quantification of Microplastics by Pyrolysis Coupled with Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry in Sediments: Challenges and Implications. Microplastics 2022, 1, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolin, M.S.; Ivaneev, A.I.; Savonina, E.Y.; Dzhenloda, R.K. Extraction of Microplastics from River Water in a Rotating Coiled Column Using a Water–Oil System. J. Anal. Chem. 2025, 80, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.S.; Choe, J.H.; Yoo, J.; Choi, T.M.; Lee, H.R.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Pyo, S.G. Vibrational Spectroscopy for Microplastic Detection in Water: A Review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2024, 60, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, S.; Teng, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Qin, Y.; He, Y.; Fan, L. Deep learning assisted ATR-FTIR and Raman spectroscopy fusion technology for microplastic identification. Microchem. J. 2025, 212, 113224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Savino, I.; Pojar, I. A practical overview of methodologies for sampling and analysis of microplastics in riverine environments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 24187-2023; Principles for the Analysis of Microplastics Present in the Environment. International Standard ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Sotnikova, Y.S.; Karpova, E.V.; Song, D.I.; Polovyanenko, D.N.; Kuznetsova, T.A.; Radionova, S.G.; Bagryanskaya, E.G. The development of an analytical procedure for the determination of microplastics in freshwater ecosystems. Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 8019–8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandikes, G.; Banerjee, O.; Mirthipati, M.; Bhargavi, A.; Jones, H.; Pathak, P. Separation, Identification, and Quantification of Microplastics in Environmental Samples. In Microplastic Pollutants in Biotic Systems: Environmental Impact and Remediation Techniques; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Volume 1482, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, A.P.; Tehrani-Bagha, A. A review on microplastic emission from textile materials and its reduction techniques. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 199, 109901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Y.A.; Vorobiev, E.D.; Vorobiev, D.S.; Trifonov, A.A.; Antsiferov, D.V.; Soliman Hunter, T.; Wilson, S.P.; Strezov, V. Preliminary Screening for Microplastic Concentrations in the Surface Water of the Ob and Tom Rivers in Siberia, Russia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M.; Erich, M.W.; Primpke, S.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Dekker, S.C.; Koelmans, A.A.; van Wezel, A.P. A systems approach to understand microplastic occurrence and variability in Dutch riverine surface waters. Water Res. 2020, 176, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.K.; Bochow, M.; Imhof, H.K.; Oswald, S.E. Multi-temporal surveys for microplastic particles enabled by a novel and fast application of SWIR imaging spectroscopy—Study of an urban watercourse traversing the city of Berlin, Germany. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.