Abstract

This study addresses the limited empirical evidence on women’s contributions to sustainable development leadership within higher education institutions. Focusing on Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana in Colombia, we employed a mixed-methods approach that combines surveys, semi-structured interviews, and bibliometric analysis of women-led scientific publications and academic courses. Our findings demonstrate that women leaders at UPB significantly influence and enhance sustainable practices and policies, fostering a culture of sustainability through their formal roles and collaborative, empathetic leadership. Key characteristics include inclusivity, shared vision-building, and community responsibility. Their systematic thinking and holistic problem-solving contribute to more effective sustainability outcomes, integrating environmental values into curricula, campus operations, and community engagement. The positive impact of women’s presence in sustainability governance on the university’s performance and commitment to Sustainable Development Goals highlights the importance of the institutional context. The research highlights the importance of policies that strengthen women’s leadership in sustainability as well as for continuous measurement of their contributions within specific educational and research ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Higher education institutions are crucial agents in advancing gender equality and sustainable development globally, as underscored by organizations such as UNESCO (UN 2015). Despite this recognition, significant disparities persist in academic and decision-making roles within universities, with leadership being paramount for guiding sustainability efforts and achieving Sustainable Development Goals. While women have demonstrated their invaluable role in navigating environmental and social changes, contributing innovative, sustainability-focused approaches (Leach et al. 2016; Barreiro-Gen and Bautista-Puig 2022), empirical evidence specifically detailing their contributions as sustainability leaders within HEIs remains limited, especially concerning their concrete impact on institutional practices (Williams et al. 2017). Structural obstacles, including unequal access to decision-making and persistent gender bias, continue to hinder women’s full participation in SDG-related processes, thereby constraining the transformative potential of these goals (Sharma 2023). This study addresses this critical gap by analyzing the specific role of women in promoting sustainability within Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, a Colombian HEI. We employed a mixed-methods approach to explore how women’s leadership influences and enhances sustainable practices and policies, fostering a culture of sustainability through their formal roles and distinctive leadership styles. By focusing on UPB, this research offers valuable insights into gender dynamics and sustainability performance within a specific institutional context, highlighting the need for policies that enhance women’s leadership in sustainability.

2. Barriers for Women in Addressing SDGS: Literature Review

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation of women, causing a significant social and economic setback whose effects remain evident in both economic development and societal dynamics. ECLAC notes that women have faced an alarming increase in domestic violence. This poses serious challenges to achieving gender equality, fulfilling women’s rights, empowering their autonomy, and advancing sustainable development with equality in the region (Galán-Muros et al. 2023). These conditions reveal deep-rooted structural obstacles—such as persistent gender-based violence, limited access to leadership positions, and inequities in education and employment—that directly hinder women’s ability to participate fully in, and contribute to, the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (Diaz-Sarachaga 2021).

Addressing these barriers requires multi-sectoral action, with higher education playing a pivotal role. Galán-Muros et al. (2023) argue that achieving gender equality in higher education and research is essential for advancing women’s rights and promoting social justice. An ECLAC policy brief examines the representation of women in various academic positions within higher education institutions (HEIs) and highlights persistent gender inequalities in academia worldwide. It emphasizes the need for policies that ensure hiring and promotion practices are based equally on performance indicators, enabling a more accurate recognition of women’s contributions and supporting them at every stage of their academic careers. Acknowledging the influence of female teachers and researchers on shaping education and serving as role models is equally important (Brundtland 1987). Galletta et al. (2022) note that gender diversity within boards of directors (academic or otherwise) has been discussed in depth. These studies show that guaranteeing diversity within the board is a critical mechanism for enhancing oversight, aligning decision-making with the interests of all stakeholders, and expanding access to a broad range of resources, expertise, and networks that collectively strengthen institutional performance (Muhammad and Migliori 2023).

Within this framework, some institutions and sectors—such as education—have made efforts to improve gender equity and address the targets of SDG 5. However, significant challenges remain, particularly in the composition of teaching, research, and leadership bodies, where the gender gap not only persists but continues to widen. Higher education institutions (HEIs) are expected to play a key role in promoting gender equality in society, as emphasized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO 2020). Yet, as of 2024, the gap in academic and decision-making roles within universities is not narrowing—it is, in fact, growing.

Leadership is essential for advancing sustainability: effective leaders guide collective action, build teams strategically, and align institutional efforts toward shared goals such as the SDGs. Pierli et al. (2022) argue that women have consistently demonstrated their value in navigating the challenges posed by social and environmental change, playing a key role as promoters of sustainability-focused approaches. Building on this, Lucchese et al. (2022) outline that the proportion of women on institutional boards significantly influences SDG disclosure in organizations, particularly in Higher Education Institutions, alongside factors such as economic performance, institutional factors, organization size, and gender representation on institutional boards.

Other studies (Rosati and Diniz Faria 2019; Cicchiello et al. 2021; Diaz-Sarachaga 2021) also agree that organizational boards with a higher proportion of women are more likely to work towards achieving the SDGs, as female directors tend to bring perspectives oriented toward energy efficiency, social welfare, and climate change policies. According to Shinbrot et al. (2019), the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 recognized women’s fundamental role in environmental management and sustainable development. Yet tangible progress toward policies that translate into action has been slow—much has been written, but less has been implemented. Scholars argue that women can offer equally strong, and sometimes superior, contributions as leaders in sustainable development, bringing grounded perspectives, innovative approaches, and authority informed by ecofeminism and feminist political ecology.

This perspective characterizes imperialism and colonialism as carriers of a specifically Western, mechanistic rationality—one often described as patriarchal or “masculinist” and as “doing violence” to both women and nature (Leach et al. 2016). Such paradigms have historically acted as barriers to women’s access to the basic opportunities needed to participate in the scientific world and benefit from its social and economic advantages. Colonial science and administration frequently portrayed local communities as environmental destroyers, legitimizing their displacement, restriction, or re-education (Leach et al. 2016; Coutinho da Silva and Batista Tortato 2018). Moreover, the traditional structures of promotion, evaluation, and production in science continue to exclude alternative perspectives, limiting the potential contributions of approaches such as ecofeminism, which strongly critiques modern science and values local and Indigenous knowledge systems. These systemic conditions shape not only what women can publish but also the terms and frameworks within which their work is recognized, forcing them to conform to traditional modes of production to be accepted into the scientific community (Surmani and Tortato 2018).

Achieving both epistemic and social justice for women requires that organizations and universities actively engage in research and initiatives that foster gender diversity, equity, and equality within their institutions, thereby empowering women and girls in alignment with SDG 5 (Mahdawi 2021). Moreover, as higher education institutions are entrusted with driving social and cultural transformation, women can be recognized as “change agents” who play a pivotal role in guiding the evolution of organizational strategies, business models, and reporting systems toward values grounded in sustainable development (Lucchese et al. 2022, p. 4). These research initiatives and sustainable strategies demand, at a minimum, gender parity among researchers, educators, and academic leaders. UNESCO-IESALC (2022) reports a steady rise in female representation in academia worldwide. In Latin America, as in the United States and the European Union, several public universities are now led by women—a significant step forward. Even so, persistent gaps remain in senior research positions and faculty roles, particularly within private institutions. In contexts where full parity is not yet achievable, women scientists can expand international collaboration—especially with regions such as Eastern Europe—which could greatly enhance the scope and impact of their initiatives.

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has disrupted these networks, slowing research progress related to sustainable development. Parity does not always lead to a significant decrease in the gender gap. Sometimes, women’s inclusion is mandated by law rather than driven by a consensual administrative decision or a true recognition of their abilities. This creates an issue, as leadership imaginaries frame stronger skills as masculine, while female traits like creativity and sensitivity (Schubert 2021) are often viewed as weaknesses for business and academic roles (Builes-Vélez et al. 2023, pp. 901–2). Despite this, results have shown that women have greater skills for collaborative work, focus on conflict resolution, and are much more empathetic, skills that allow, among other things, a better understanding of sustainability-related issues in institutions; while men tend to have a more aggressively oriented negotiation and leadership skills, and a task-oriented leadership (Eagly and Carli 2004; Schubert 2021). Nevertheless, some studies continue to view leadership skills as masculine, failing to recognize the contextual, cultural, and social factors that determine effective institutional leadership. In contexts like Colombia’s, this leadership may specifically require less aggressive and more empathetic skills for resolving internal and external social, economic, and environmental problems.

Recognizing these persistent disparities emphasizes the relevance of the findings presented in the World Survey on the Role of Women in Development 2024 by the United Nations, which highlights that women bring diverse perspectives and experiences critical to sustainable peacebuilding, inclusive development, and effective decision-making processes (Staab et al. 2024). Their active participation not only ensures that policies and programs address the needs of entire communities but also strengthens the legitimacy of strategies and advances international commitments. Furthermore, their engagement is closely linked to climate action, as women—often at the forefront of resource management, community resilience, and adaptation efforts—play a pivotal role in mitigating the disproportionate impacts of climate change and fostering innovative, locally grounded solutions that advance both gender equality and environmental sustainability. Against this backdrop, the structural obstacles that hinder women’s participation in SDG-related processes—such as unequal access to decision-making spaces, persistent gender bias in hiring and promotion, limited support for international collaboration, and the underrepresentation of women in senior academic positions—are not only issues of fairness, but also barriers to fully realizing the transformative potential of the SDGs (Staab et al. 2024). Failing to remove these barriers means leaving untapped a vast reservoir of leadership, knowledge, and innovation that is essential for achieving sustainable development. Still, women’s potential must not translate into adding environmental responsibilities to their existing care roles or instrumentalizing them as “sustainability saviours” (Leach et al. 2016, p. 11). Achieving genuine gender justice and sustainability requires recognizing and respecting women’s knowledge, rights, capabilities, and bodily integrity, while ensuring equal control over resources and decision-making power (Builes-Vélez et al. 2023). This perspective acknowledges that gender inequality and unsustainability share common structural drivers—rooted in market-oriented neoliberal growth patterns—that demand profound social, economic, and political transformation, rather than merely technical or managerial fixes (Leach et al. 2016, p. 35).

3. Materials and Methods

To achieve the objective of this study—analyzing the impact of female leadership on UPB’s sustainability performance—a mixed-methods approach was employed, combining surveys, semi-structured interviews, bibliometric analysis of scientific production, and a documentary review of national and international reports and articles addressing the situation of women in academia and leadership. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected to answer the research questions. A questionnaire with open-ended questions was administered at Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (UPB) in Medellín, Colombia, an institution characterized by a significant presence of women in research groups, teaching staff, and leadership positions.

3.1. Questionnaire

The study targeted a specific population of female researchers and university professors from different fields of knowledge whose academic work focuses on sustainability from multiple perspectives or through the teaching of related courses. A formal invitation was sent to a total of 86 women who met the inclusion criteria. Of this group, a response rate of 27.9% was obtained, with a total of 24 participants completing the questionnaire. The researchers and teachers who responded are distinguished by a profile of high commitment to the institution and the subject of study, characterized by: leadership in gender equality, a history of significant efforts to make women’s work within the institution visible, and positioning themselves as key figures in the promotion of equality. In addition to questions on leadership and sustainability, the survey explored participants’ understanding of the concept of sustainability, as well as the challenges and barriers they perceive in their roles as researchers, educators, and administrators within the broader context of higher education and society.

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

To deepen understanding of the findings emerging from the questionnaire, a qualitative phase was implemented through semi-structured interviews. The selection of participants for this phase was intentional and based on convenience, seeking to maximize the informational richness of the qualitative data. Five (5) researchers and teachers were selected from the 24 who responded to the questionnaire, applying the following inclusion criteria, derived from the research objectives:

- Representativeness by thematic leadership: priority was given to those participants who showed greater academic production and/or institutional experience at the intersection of sustainability and gender equality (SDG 5), as evidenced in their responses to the questionnaire.

- Institutional visibility: researchers who demonstrated an active and visible role in promoting and raising awareness of women’s work within the higher education institution (HEI) were included.

- Diversity of perspectives: an effort was made to include women from various areas of knowledge and with different academic roles—teaching, research, management- to ensure a holistic perspective of the impact.

The semi-structured interview script focused on five (5) key questions designed to explore the participants’ perceptions and experiences of the impact of women’s work in HEIs, with particular emphasis on their contribution to research, sustainability, and gender equity. The interviews were transcribed and subjected to qualitative content analysis to identify emerging themes and categories. Initial coding was performed independently by two or more researchers (peer coding). Disagreements in the assignment of codes or the interpretation of themes were resolved through a process of reflective discussion and consensus, anchoring final decisions to the theoretical frameworks established for the research. This ensured the reliability of the qualitative data obtained.

3.3. Bibliometric Analysis

The bibliometric analysis was performed on the SCOPUS database, using a systematic search strategy. The time frame of the review covered seven years, from 2017 to 2023. The search focused exclusively on scientific output with institutional affiliation to the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (UPB). The exact query executed in SCOPUS was:

AFFIL( \text{“Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana”} \ ) \ AND \ PUBYEAR \ > \ 2013 \ AND \ (LIMIT \ TO \ ( \ PUBSTAGE, \ “FINAL” \ ) \ OR \ LIMIT \ TO \ ( \ PUBSTAGE, \ “IN \ PRESS” \ ) )

The initial dataset included detailed information about the article (title, abstract, year) and the gender of the authors/co-authors. The selection of SDGs to be analyzed was aligned with the UPB’s strategic agenda (UPB 2024), prioritizing SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 4 (Quality Education, focused on sustainability). To link UPB articles to these specific SDGs, the following procedure was used:

- Thematic classification: the second Excel file contained the classification of each article by its dominant SDG.

- Classification method: a manual classification method was used by experts (the study researchers) who reviewed the title, abstract, and keywords of each article, comparing them with the specific goals of SDGs 4, 5, and 8.3.

- Reliability of SDG classification: to ensure the reliability of the SDG classification process, a rigorous validation strategy was implemented.

- Resolution of Disagreements: Cases of disagreement in SDG classification were resolved through thoughtful discussion and consensus among the four researchers, adhering to the SDG guidelines for final classification.

- The total of 1880 articles selected for analysis were reviewed independently by four researchers. This peer coding process ensured that the assignment of each article to its respective SDG (4, 5, or 8) was consistent and objective.

Additionally, a list of research projects aligned with the SDGs and led by women at UPB was examined to identify which goals had been prioritized and to assess the impact of these projects on the institution’s sustainability performance. Courses led by women faculty members that incorporated topics such as Sustainable Development, Climate Change, and the SDGs were also reviewed to capture the educational dimension of women’s contributions to sustainability.

Findings from the documentary review, bibliometric analysis, projects, and courses were descriptively analyzed and triangulated with the questionnaire responses and semi-structured interviews. This methodological integration provided a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted role of women in advancing sustainability through leadership, teaching, and research.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical findings on women’s contributions to sustainability at Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (UPB), followed by a comparative analysis with national and global trends. The aim is to highlight institutional patterns while situating them within broader systemic contexts.

Women at UPB play a significant role in advancing sustainability through research, teaching, and governance. At the governance level, the Vice-Rector’s Office for Research is led by a woman, although only two of the eight School Research Coordinating Offices are directed by women. In 2024, UPB reported 215 researchers, of whom 86 were women (40%), which is slightly above the national average of 38.6% but still falls short of parity (UPB 2024).

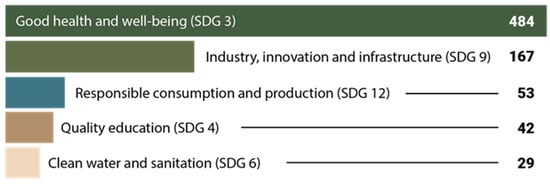

Bibliometric analysis of SCOPUS-indexed publications between 2017 and 2023 shows that 47.45% of UPB’s articles included at least one woman as author or co-author. Women’s contributions are particularly prominent in SDG 3 (Health and Well-being) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), reflecting disciplinary tendencies toward health-related fields and emerging participation in innovation. However, SDG 5 (Gender Equality) remains absent, indicating that gender issues are not prioritized in UPB’s research agenda (UPB 2024) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Publications in SCOPUS with women’s participation by SDG. Source: UPB SCOPUS Report 2024.

In teaching, women lead 24 courses explicitly referencing sustainability, representing 60% of all sustainability-related courses offered at UPB. Interviews with faculty reveal that sustainability is often addressed through interdisciplinary approaches, particularly in engineering and architecture programs, though integration across curricula remains limited. Survey responses from UPB women involved in sustainability work emphasize the importance of systemic and long-term resource management, intergenerational justice, and cultural preservation. Participants advocate for institutional actions, such as reducing plastic use, improving bioclimatic campus design, and integrating sustainability as a core strategy rather than an add-on policy.

National and global data reveal persistent gender disparities in education and research. According to UNESCO (2020), women represent 94% of pre-primary teachers but only 43% of tertiary education staff worldwide, reflecting a “Glass Ceiling” (Zeng 2011) in academic leadership. In Colombia, DANE (2023) reports that women account for 95.2% of preschool teachers, 77% of primary school teachers, and 52.4% of secondary school teachers, while men dominate higher education and STEM disciplines.

In research, MINCIENCIAS (2022) identifies 21,094 researchers in Colombia, of whom 38.6% are women—slightly below the Ibero-American average of 45%. Leadership gaps are even more pronounced: women lead only 1485 research groups compared to 2818 led by men. These patterns mirror UPB’s internal dynamics, where women remain underrepresented in top research leadership roles and patent applications.

Gender disparities are particularly acute in STEM fields. UNESCO (2020) Women Colombia reports that only 37.3% of STEM graduates are women. At UPB, similar trends persist, with women concentrated in health-related research and underrepresented in technical innovation areas. This alignment underscores structural barriers—such as stereotypes, limited mentorship, and male-dominated professional environments—that constrain women’s participation in science and technology.

STEM disciplines are critical for addressing environmental challenges through innovation, energy efficiency, and climate action. Even so, global and national deficits in STEM professionals, compounded by gender gaps, limit progress toward sustainability goals. At UPB, initiatives such as sustainability-focused engineering courses and interdisciplinary projects aim to counter these trends, but greater efforts are needed to attract and retain women in STEM fields. Early exposure to female role models and targeted mentorship programs are essential strategies for fostering gender equity in these areas.

5. Discussion

These findings enable us to revisit the guiding questions posed at the outset of this section—what characterizes female sustainability leadership, how it manifests in practice, and how women navigate institutional challenges. The results indicate that women at Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (UPB) make substantial contributions to research, teaching, and sustainability initiatives. Yet, their participation in institutional governance reveals persistent structural barriers that shape the extent of their influence. Interpreting these patterns through national data and feminist theoretical frameworks provides a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms that enable and constrain women’s leadership within higher education institutions (HEIs) in Colombia.

UPB demonstrates comparatively strong female participation in academic production. Between 2017 and 2023, 892 of 1880 SCOPUS-indexed publications (47.45%) included at least one woman author, a figure that contrasts with national patterns where women represent only 38.6% of recognized researchers (MINCIENCIAS 2022). Women also constitute 40% of UPB’s researchers—slightly above national levels—and play a visible role in teaching sustainability-related courses and leading SDG-oriented projects. These trends diverge from the persistent gender imbalances reported by UNESCO (2020) and DANE (2023), particularly in STEM fields, where women continue to be underrepresented.

Despite these positive indicators, UPB reproduces a central contradiction widely documented in international literature: women’s strong contributions to academic productivity and institutional performance do not translate into proportional representation in strategic decision-making spaces. Essentially, academic capital functions as the currency of prestige and credibility, while strategic capital operates as the engine of influence and resource allocation. Although women significantly bolster the indicators that support UPB’s accreditation and ranking performance, they remain underrepresented in leadership structures where institutional priorities, resources, and long-term strategies are defined. This reinforces the pattern of vertical segregation in HEIs, where women’s presence is robust in academic and operational spheres but limited in the upper tiers of governance.

The underrepresentation of women in strategic roles at UPB cannot be attributed to a lack of qualifications or experience. As participants explained, women typically advance through extensive, merit-based trajectories: they begin as instructors, move through coordination roles, and lead research or administrative projects before reaching directive positions. This progression provides women with deep knowledge of institutional processes, teams, and contexts, which are key assets for sustainability leadership.

However, several structural mechanisms limit their access to higher-impact decision-making. First, leadership appointments are not always based on transparent, criteria-driven processes. Instead, decisions rely heavily on the opinions of committees whose composition remains predominantly male. Such informal selection practices tend to reproduce established networks and implicit biases, a dynamic consistent with the literature on gender and leadership in academia.

Second, participants identified a relational tension: while male colleagues value women’s academic work, there is often resistance to being directed by women. This reflects a subtle but persistent form of gender bias that aligns with “Glass C” dynamics reported globally. In this configuration, women are welcomed as collaborators and contributors; conversely, their authority is often contested when they occupy positions of formal leadership. These mechanisms illustrate how institutional cultures, rather than individual limitations, sustain gendered power imbalances.

Several leadership practices emerged from the study—collaborative approaches, effective coordination, and systemic thinking—which are frequently attributed to women in sustainability roles. Nevertheless, consistent with feminist political ecology and ecofeminist critiques, these patterns must be understood as context-dependent rather than inherent traits. The evidence suggests that these practices result from a combination of factors, such as gendered socialization, which historically positions women as mediators and coordinators in both professional and domestic spheres.

Institutional expectations, where women are often relied upon to “sustain” teams, manage complexity, and address relational or organizational challenges. Trajectory-shaped competencies, since women at UPB frequently accumulate experience across multiple levels—teaching, co-ordination, research, administration—before reaching leadership roles. Organizational demands, especially in sustainability governance, increasingly require collaborative problem-solving, interdisciplinary articulation, and long-term vision.

Understanding these practices as products of social, institutional, and professional processes is essential to avoid essentializing discourses that risk reinforcing stereotypes. The findings indicate that women’s leadership contributions at UPB arise not from presumed inherent qualities but from the situated expertise developed through their career trajectories and institutional engagement.

The interaction between women’s strong academic contributions and their limited access to strategic influence generates several tensions within UPB. Women at UPB contribute significantly to sustainability indicators through research, teaching, and project leadership. Yet, their influence over strategic decision-making remains limited, reinforcing a gendered divide between academic work and governance. Moreover, women often reach leadership positions through long, rigorous, internally built trajectories, while some men access similar roles through shorter paths or external appointments, raising questions about institutional definitions of merit and the criteria used to identify leadership potential.

Additionally, although women’s work is highly visible in publications, courses, and sustainability initiatives, their presence diminishes at the upper echelons of decision-making, suggesting that their contributions are recognized as academic capital but not fully acknowledged as strategic capital. Together, these tensions align with studies indicating that sustainability work often relies on women’s expertise while simultaneously limiting their decision-making authority (Shinbrot et al. 2019).

This case makes significant contributions to the field in three ways. First, it provides empirical evidence that women’s participation strengthens institutional sustainability performance, supporting findings on the positive effects of gender diversity in sustainability governance. Second, it challenges essentializing narratives by showing that women’s leadership practices at UPB are shaped by structural and institutional conditions rather than innate characteristics. Third, it reveals how sustainability efforts in HEIs may depend on labor that is not equally recognized within governance structures, highlighting the need for more equitable institutional arrangements.

The findings suggest that UPB could strengthen both gender equity and sustainability performance by adopting transparent, criteria-based procedures for leadership selection; ensuring more balanced gender representation in strategic committees; and formally recognizing the relational and coordination work carried out by women. In addition, strengthening promotion and performance evaluation processes would help ensure that positions of power are filled by individuals who have demonstrably developed the leadership capacities required in context. Such measures would better align the university’s sustainability commitments with its gender equity objectives and enhance its overall institutional capacity.

This study empirically demonstrates the profound and positive impact of women’s leadership on sustainability performance within higher education institutions, using Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana in Colombia as a specific case. Beyond broad discussions of systemic barriers like the “Glass Ceiling” (Zeng 2011) and “Leaky Pipeline” (Ayyildiz and Banoglu 2024), our mixed-methods approach (combining survey data, semi-structured interviews, and institutional database analysis) revealed concrete evidence of how women professors and researchers significantly enhance UPB’s sustainability initiatives.

Specifically, our findings demonstrate that the active participation of women in research programs, faculties, and sustainability management committees directly correlates with improved institutional sustainability outcomes. The study highlights that gender parity within work teams and committees leads to more positive results, underscoring women’s critical role in problem-solving and knowledge generation related to sustainability. These contributions are not merely anecdotal but are rooted in women’s demonstrated capacity for empathy, collaborative approaches, and their role as agents of change in community adaptation.

This research, therefore, adds a vital layer of empirical evidence to the existing literature by providing a detailed examination within a specific institutional and regional context. It challenges outdated beliefs regarding women’s capabilities in scientific and leadership roles by showcasing their tangible and positive influence on institutional sustainability. The study underscores the imperative for higher education institutions to integrate gender-sensitive policies and practices that foster inclusive participation and leadership.

By proactively addressing persistent structural inequalities and promoting gender parity in academic and governance structures, HEIs like UPB can not only close gender gaps but also significantly strengthen their capacity for innovation, resilience, and achieving long-term sustainability goals. Our findings advocate for targeted interventions to support and elevate women in these roles, recognizing their indispensable contribution to building more just, competitive, and environmentally responsible organizations.

6. Conclusions

Even today, in the 21st century, the belief that women advance more slowly than men and that they do not have the same capabilities to perform as scientists continues to prevail in many organizations, without considering the strong influence of certain social factors that discourage women from embarking on a scientific career, for example, pursuing a PhD, as mentioned above. Including women in committees and boards is necessary, as the literature review shows, because women are key in community adaptation and are agents of change since they are more empathetic and tend to collaborate more.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; methodology, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; validation A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; investigation, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; resources, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; data curation, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; writing—review and editing, A.E.B.-V., D.J.P.M.H., J.D.M.M. and J.R.J.; project administration, A.E.B.-V. and J.R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC were funded by Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Comite De Etica De Investigacion En Salud Med of Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (protocol code ACTA 14 de 2023, 26 June 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data was published by authors at International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-09-2023-0423.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the women researchers, teachers, and administrative staff of Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (UPB) for their valuable participation in this study. Their insights, experiences, and collaboration were fundamental to the development of this research. The authors also acknowledge the support of digital research tools, including artificial intelligence–based assistance (ChatGPT4, OpenAI), which was used to improve the clarity, coherence, and language of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

References

- Ayyildiz, Pinar, and Koksal Banoglu. 2024. The leaky pipeline: Where ‘exactly’ are these leakages for women leaders in higher education? School Leadership & Management 44: 120–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro-Gen, Maria, and Núria Bautista-Puig. 2022. Women in sustainability research: Examining gender authorship differences in peer-reviewed publications. Frontiers in Sustainability 3: 959438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, Gro Harlem. 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Builes-Vélez, Ana Elena, Lina Maria Escobar Ocampo, Juliana Restrepo Jaramillo, and Ana Maria Osorio Floréz. 2023. Women’s influence on sustainability performance in Higher Education Institutions: The case of Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (Medellín, Colombia). Paper presented at the 29th International Sustainable Development Research Society Conference, Faculty of Law, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Bangi, Malaysia, July 11–13; pp. 882–915. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchiello, Antonella Francesca, Anna Maria Fellegara, Amirreza Kazemikhasragh, and Stefano Monferrà. 2021. Gender diversity on corporate boards: How Asian and African women contribute on sustainability reporting activity. Gender in Management: An International Journal 36: 801–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho da Silva, Ana Claudia, and Cintia de Souza Batista Tortato. 2018. Movimentos e epistemologia feministas: Um novo olhar sobre a ciência. Anais do V Simpósio Gêneros e Políticas Públicas 5: 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANE. 2023. Educación, Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación ECTel; Bogotá: DANE. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/boletines/educacion/ectei/documento-ECTeI-1-reporte-estadistico.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Diaz-Sarachaga, Jose Manuel. 2021. Shortcomings in reporting contributions towards the sustainable development goals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 1299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Linda L. Carli. 2004. Women and men as leaders. In The Nature of Leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Galán-Muros, Victoria, Mathias Bouckaert, and Jaime Roser-Chinchilla. 2023. The Representation of Women in Academia and Higher Education Management Positions: Policy Brief. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Galletta, Simona, Sebastiano Mazzù, Valeria Naciti, and Carlo Vermiglio. 2022. Gender diversity and sustainability performance in the banking industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 29: 161–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, Melissa, Lyla Mehta, and Preetha Prabhakaran. 2016. Gender equality and sustainable development: A pathways approach. The UN Women Discussion Paper 13: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchese, Manuela, Ferdinando Di Carlo, Natalia Aversano, Giuseppe Sannino, and Paolo Tartaglia Polcini. 2022. Gender Reporting Guidelines in Italian Public Universities for Assessing SDG 5 in the International Context. Administrative Sciences 12: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdawi, Arwa. 2021. Strong Female Lead: Lessons from Women in Power. London: Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación de Colombia, (MINCIENCIAS). 2022. La Ciencia en Cifras: Researchers. [Online Database]. Available online: https://minciencias.gov.co/la-ciencia-en-cifras/investigadores (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Muhammad, Hussain, and Stefania Migliori. 2023. Effects of board gender diversity and sustainability committees on environmental performance: A quantile regression approach. Journal of Management & Organization 29: 1051–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierli, Giada, Federica Murmura, and Federica Palazzi. 2022. Women and Leadership: How Do Women Leaders Contribute to Companies’ Sustainable Choices? Frontiers in Sustainability 3: 930116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, Francesco, and Lourenço Galvão Diniz Faria. 2019. Business contribution to the Sustainable Development Agenda: Organizational factors related to early adoption of SDG reporting. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26: 588–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, Katrine Juliane. 2021. Gender Differences in Leadership: An Investigation into Female Leadership Styles and Affective Organisational Commitment. Dublin: CCT College Dublin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Harshita. 2023. Gender equality and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A comprehensive analysis. International Journal of Science and Social Science Research 1: 162–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinbrot, Xoco A., Kate Wilkins, Ulrike Gretzel, and Gillian Bowser. 2019. Unlocking women’s sustainability leadership potential: Perceptions of contributions and challenges for women in sustainable development. World Development 119: 120–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, Silke, Loui Williams, Constanza Tabbush, and Laura Turquet. 2024. Harnessing Social Protection for Gender Equality, Resilience and Transformation. World Survey on the Role of Women in Development. New York: UN-Women. [Google Scholar]

- Surmani, Josiane de Souza, and Cíntia de Souza Batista Tortato. 2018. A Construção Do Campo Científico E O Feminismo. Revista Mundi Engenharia, Tecnologia e Gestão 3: 56–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2020. Global Education Monitoring Report. Gender Report. A New Generation: 25 Years of Efforts for Gender Equality in Education. Paris: UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374514/PDF/374514eng.pdf.multi (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC). 2022. Gender Equality: How Global Universities are Performing—Part 2. London: Times Higher Education. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381739 (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- United Nations (UN). 2015. Sustainable Development Goals—Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. 2024. Reporte de Sostenibilidad de la Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana Bajo Estándares Global Reporting Initiative. Medellín: Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. Available online: https://repository.upb.edu.co/bitstream/handle/20.500.11912/11620/Reporte_de_Sostenibilidad_UPB_2023_compressed.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Williams, Jannine, Elina Meliou, and Jorge A. Arevalo. 2017. Gender and sustainable management education: Exploring the missing link. In Handbook of Sustainability in Management Education. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 307–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Zhen. 2011. The myth of the glass ceiling: Evidence from a stock-flow analysis of authority attainment. Social Science Research 40: 312–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).