Assessment of Soft Skills for Construction Professionals in New Zealand: Perspectives from Contractor Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Objective 1. To determine which soft skills are perceived by QS and PM to be important.

- Objective 2. To apply statistical tests to get a preliminary indication of any difference in the ranking of importance of soft skills by QS and PM.

- Objective 3. To establish which soft skills are important for QS to successfully transition to PM roles.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks for Role Transition and the Influence of Soft Skills

2.2. Soft Skills for the Construction Industry

2.3. Soft Skills in Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers

2.4. Summary of the Literature

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Sample and Participant Demographics

3.2. Data Analysis

- p < 0.01: highly significant difference between the two cohorts.

- p < 0.05: significant difference between the two cohorts.

4. Results and Discussion

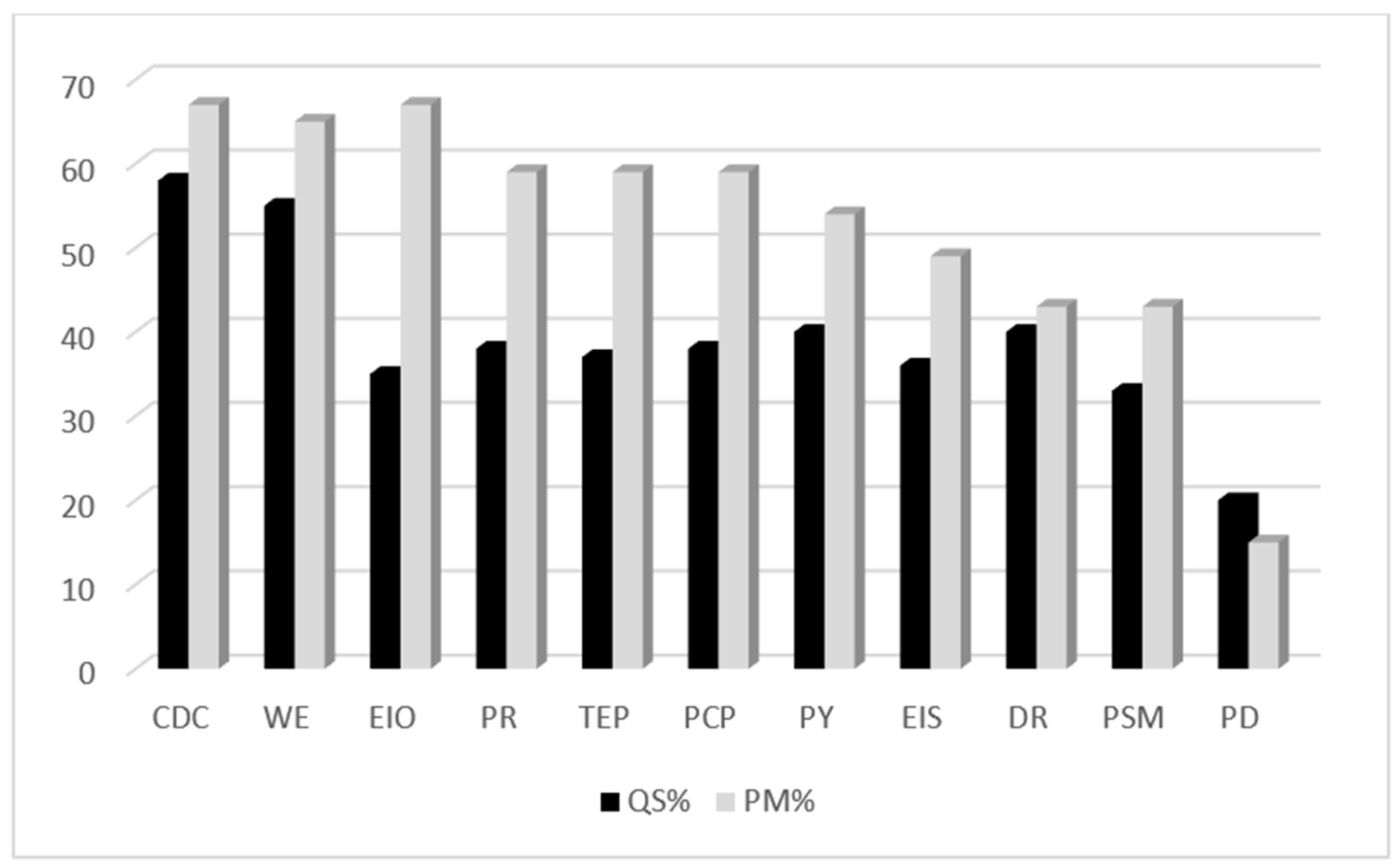

4.1. Ranking of the Perceived Importance of Soft Skills Clusters by QS and PM (Objective 1)

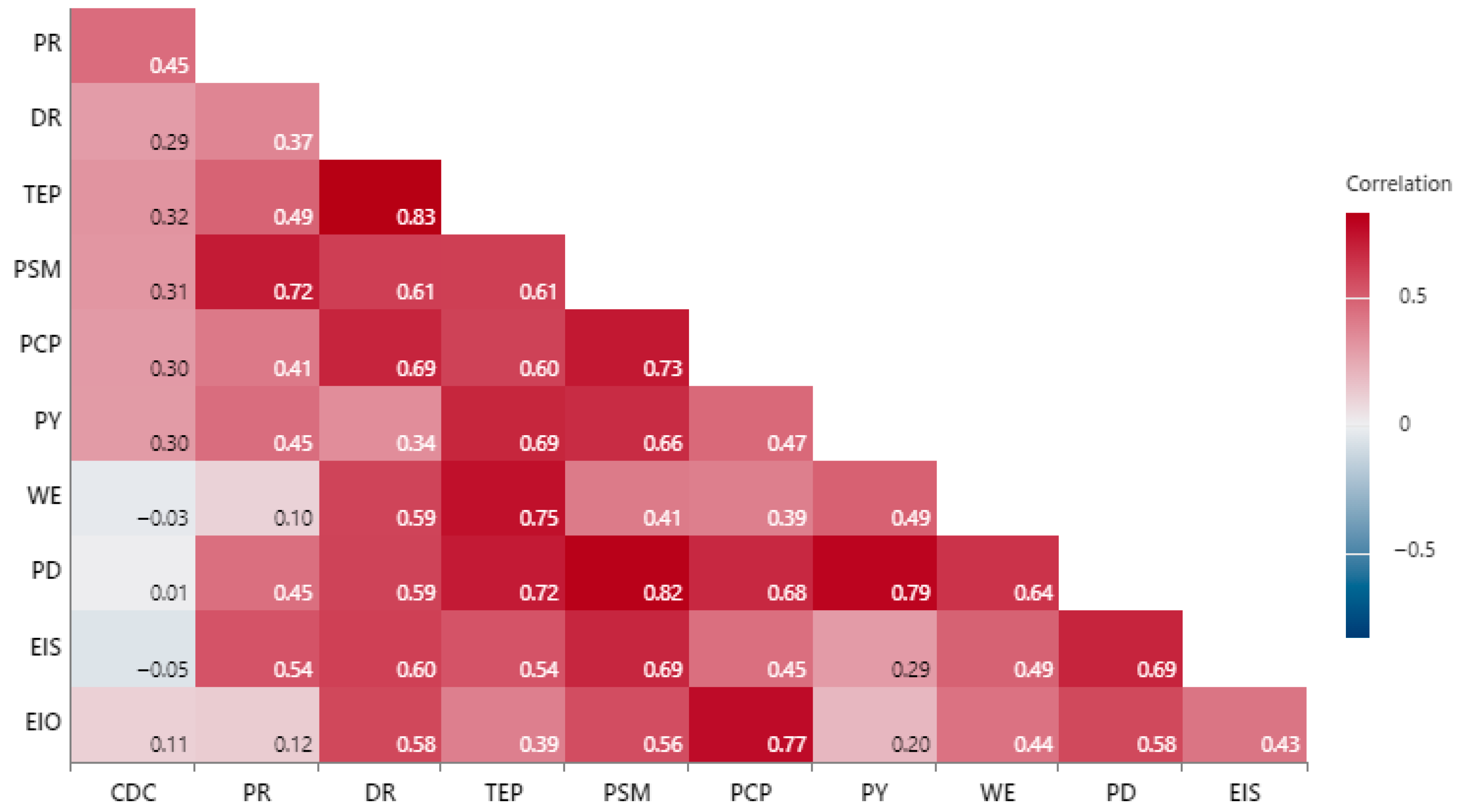

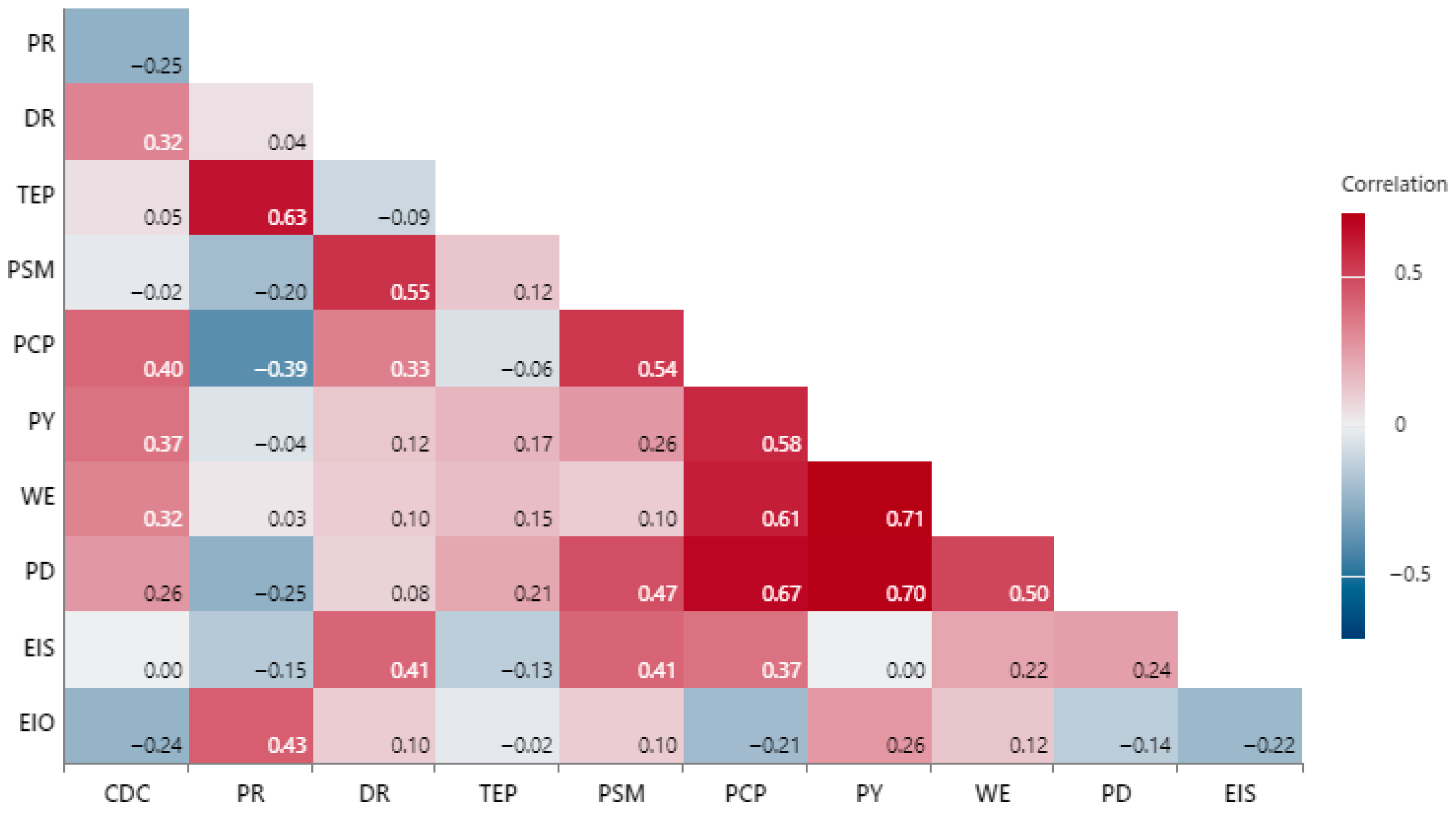

4.2. Strength of Correlation Between Pairs of Soft Skills Clusters

4.3. Applying Statistical Tests to Get a Preliminary Indication of Difference in the Ranking of the Importance of Soft Skills Clusters by QS and PM (Objective 2)

4.4. Apex Soft Skills for QS and PM

4.5. Participant Comments on Transitioning from QS to PM Roles

- QS have “excessive preoccupation with numerical data”; “they mostly deal with a computer, they need to develop a wider point of view and learn to talk to people”; QS “want everything to fit, they need to be adaptive”; QS require “higher empathy”; QS can be “unemotional”.

- PM roles require “lots of nuance and grey areas where being right is not necessarily the best solution for the outcome of the project”; “teamwork is required by PM, less so for QS”; “PM roles require dealing with people”; PMs need “diverse communication competencies”; “a lot of QS do not like talking to sub-contractors and don’t know that you have to be able to have a yarn with them”; “some QS have the ‘gift of the gab’ and appear to know it”; and QS need to “relate to people and develop leadership”.

- QS already has “good people skills and knows how to be part of a team. They need to know how a building goes together, construction methodology and programming”; QS require “technical skills and project programming skills”; QS require “more practical experience”.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QS | Quantity surveyors |

| PM | Project managers |

| CDC | Communication and document control |

| PR | Project reasoning |

| DR | Dispute resolution |

| TEP | Team effort and partnership |

| PSM | Project stress management |

| PCP | Professional code of practice |

| PY | Project yield |

| WE | Workplace ethics |

| PD | Project diversity |

| EIS | Emotional intelligence (self) |

| EIO | Emotional intelligence (others) |

References

- Darlow, G.; Rotimi, J.O.B.; Shahzad, W.M. Automation in New Zealand’s offsite construction (OSC): A status update. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2022, 12, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likita, A.J.; Jelodar, M.B.; Vishnupriya, V.; Rotimi, J.O.B.; Vilasini, N. Lean and BIM implementation barriers in New Zealand construction practice. Buildings 2022, 12, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. Stuff. Here’s What You Need to Know About Struggling Construction Firms. 2022. Available online: https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/300643804/heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-struggling-construction-firms (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). Building and Construction Sector Trends—Annual Report 2023; Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (MBIE): Wellington, New Zealand, 2024; pp. 1–52. Available online: https://www.mbie.govt.nz/assets/building-and-construction-sector-trends-annual-report-2023.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Somers, E. Interest. Construction Sector Faces Rising Number of Liquidations as Business Credit Defaults Also Climb Across the Industry According to Credit Bureau Centrix. 2024. Available online: https://www.interest.co.nz/business/129995/construction-sector-faces-rising-number-liquidations-business-credit-defaults-also (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Adafin, J.; Wilkinson, S.; Rotimi, J.O.B.; MacGregor, C.; Tookey, J.; Potangaroa, R. Creating a case for innovation acceleration in the New Zealand building industry. Constr. Innov. 2021, 22, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Pelosi, A.; Jia, Y.; Shen, X.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Yang, N. Implementation of technologies in the construction industry: A systematic review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 3181–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, E.; Burger, M. Effective utilisation of generation Y Quantity Surveyors. Acta Structilia 2016, 23, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Barcaui, A.; Bahli, B.; Figueiredo, R. Do the Project Manager’s Soft Skills Matter? Impacts of the Project Manager’s Emotional Intelligence, Trustworthiness, and Job Satisfaction on Project Success. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadim, N.; Thaheem, M.J.; Ullah, F.; Mahmood, M.N. Quantifying the cost of quality in construction projects: An insight into the base of the iceberg. Qual. Quant. 2023, 57, 5403–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, I.; Eshtehardian, E.; Nasirzadeh, F.; Arabi, S. Dynamic modeling to reduce the cost of quality in construction projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloi, D.; Price, A.D.F. Modelling global risk factors affecting construction cost performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhag, T.M.S.; Boussabaine, A.H.; Ballal, T.M.A. Critical determinants of construction tendering costs: Quantity surveyors’ standpoint. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, A. Contractual Procedures in the Construction Industry, 6th ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, M.; Mbachu, J.; Phipps, R. Critical success factors, opportunities and threats of the cost management profession: The case of Australasian quantity surveying firms. Int. J. Proj. Organ. Manag. 2013, 5, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wao, J.O.; Flood, I. The role of quantity surveyors in the international construction arena. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2016, 16, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.J.; Booyens, D.E.; Trusler, K. Agents for Change—Profiling South African Construction Quantity Surveyors. In Intelligent Sustainable Systems: Selected Papers of WorldS4 2022; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, S.; Steyn, H.; Bond-Barnard, T.J. The relationship between project management maturity and project success. J. Mod. Proj. Manag. 2022, 10, 218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, A. A Review of Successful Construction Project Managers’ Competencies and Leadership Profile. J. Rehabil. Civ. Eng. 2023, 11, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Mehmood, A. Employability skills: The need of the graduates and the employer. VSRD Int. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2014, 4, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heerden, H.H.G. The Road to Purpose-Fit Selection of the Construction Manager. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pretoria (South Africa), Pretoria, South Africa, 2018; pp. 1–266. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarenga, J.C.; Branco, R.R.; Guedes, A.L.A.; Soares, C.A.P.; da Silveria e Silva, W. The project manager core competencies to project success. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteson, M.L.; Anderson, L.; Boyden, C. “Soft skills”: A phrase in search of meaning. Portal Libr. Acad. 2016, 16, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloumakos, A.K. Expanded yet restricted: A mini review of the soft skills literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, S.; McGregor, H. Recognizing and supporting a scholarship of practice: Soft skills are hard! Asia-Pac. J. Coop. Educ. 2005, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, M. Moocs and soft skills: A comparison of different courses on creativity. J. E-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2017, 13, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kechagias, K. (Ed.) Teaching and Assessing Soft Skills; MASS Project, September; 1st Second Chance School of Thessaloniki (Neapolis): Thessaloniki, Greece, 2011; pp. 1–189. ISBN 978-960-9600-00-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, S.T.; Reid, S.; Barry, S. Successful managerial attributes of construction project managers: Empirical evidence from Australia. Pac. Rim Prop. Res. J. 2024, 29, 66–96. [Google Scholar]

- Oni, O.J.; Aina, Y.J. Employers’ perspectives on critical quantity surveying soft skills. Int. J. Innov. Res. Adv. Stud. 2020, 7, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Qizi, K.N.U. Soft skills development in higher education. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, W.J.; Logan, J.; Smith, S.M.; Szul, L.F. Meeting the Demand: Teaching “Soft” Skills; Delta Pi Epsilon: Prescott, AZ, USA, 2002; pp. 1–82. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED477252.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Van Heerden, A.H.; Jelodar, M.B.; Chawynski, G.; Ellison, S. A study of the soft skills possessed and required in the construction sector. Buildings 2023, 13, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, S. Soft skills assessment: Theory development and the research agenda. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2014, 33, 455–471. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E. Investigating the perception of stakeholders on soft skills development of students: Evidence from South Africa. Interdiscip. J. E-Ski. Life Long Learn. 2016, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahasneh, J.K.; Thabet, W. Developing a normative soft skills taxonomy for construction education. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. Res. 2016, 3, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar]

- George, M.M.; Wittman, S.; Rockmann, K.W. Transitioning the study of role transitions: From an attribute-based to an experience-based approach. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2022, 16, 102–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J.; da Motta Veiga, S.P.; Hirschi, A.; Marciniak, J. Career transitions across the lifespan: A review and research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2024, 148, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, S.F.; Bakker, A. Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 132–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maanen, J.; Schein, E.H. Toward a theory of organizational socialization. Res. Organ. Behav. 1979, 1, 209–264. [Google Scholar]

- Trede, F.; Macklin, R.; Bridges, D. Professional identity development. Stud. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkerman, S.F.; Bruining, T. Multilevel boundary crossing in a professional development school partnership. J. Learn. Sci. 2016, 25, 240–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, M.; Bekebrede, J.; Hanna, F.; Creton, T.; Edzes, H. The contribution of graduation research to school development: Graduation research as a boundary practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 40, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerosuo, H.; Engeström, Y. Boundary crossing and learning in creation of new work practice. J. Workplace Learn. 2003, 15, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trede, F.; McEwen, C. Developing a critical professional identity: Engaging self in practice. In Practice-Based Education: Perspectives and Strategies; Higgs, J., Barnett, R., Billett, S., Hutchings, M., Trede, F., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media, Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 27–40. ISBN 9462091285. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, J. Organization Development: How Organizations Change and Develop Effectively; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 1352009285. [Google Scholar]

- Dainty, A.; Moore, D.; Murray, M. Communication in Construction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0203358641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.; Morris, P.; Thomas, J.; Winter, M. Practitioner development: From trained technicians to reflective practitioners. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.; Stasis, A.; Lindkvist, C. Managing change in the delivery of complex projects: Configuration management, asset information and ‘big data’. Int. J. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Lloyd-Walker, B. Collaborative Project Procurement Arrangements; Project Management Institute Inc.: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/collaborative-project-project-procurement-arrangements-11645 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Crawford, L.; Cooke-Davies, T.; Hobbs, B.; Labuschagne, L.; Remington, K.; Chen, P. Governance and support in the sponsoring of projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, S43–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, J.; Ireland, V.; Gorod, A. Clarifying the project complexity construct: Past, present and future. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechky, B.A. Making Organizational Theory Work: Institutions, occupations, and negotiated orders. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succi, C.; Canovi, M. Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: Comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1834–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Norbash, A. Transitional leadership: Leadership during times of transition, key principles, and considerations for success. Acad. Radiol. 2017, 24, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, A.; Chang, A.; Wiewiora, A.; Ashkanasy, N.M.; Jordan, P.J.; Zolin, R. Manager emotional intelligence and project success: The mediating role of job satisfaction and trust. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassi, A.A.; Roufechaei, K.M.; Abu Bakar, A.H.; Yusof, N. Linking team condition and team performance: A transformational leadership approach. Proj. Manag. J. 2017, 48, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulch, B.G. The Construction Project Manager as Communicator in the Property Development and Construction Industries. Doctoral Dissertation, University of the Free State (South Africa), Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2012; pp. 1–241. [Google Scholar]

- Bora, B. The essence of soft skills. Int. J. Innov. Res. Pract. 2015, 3, 7–22. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/22419076/The_Essence_of_Soft_Skills (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Cimatti, B. Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2016, 10, 97–130. Available online: http://www.ijqr.net/journal/v10-n1/5.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Thompson, S. The power of pragmatism: How project managers benefit from coaching practice through developing soft skills and self-confidence. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 2019, S13, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, G.; Capone, V.; Babiak, J.; Bajcar, B.; Kuchta, D. Efficacy beliefs, empowering leadership, and project success in public research centers: An Italian–polish study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6763. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, M.M. Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Bus. Commun. Q. 2012, 75, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Kiyani, S.K.; Dust, S.B.; Zakariya, R. The impact of ethical leadership on project success: The mediating role of trust and knowledge sharing. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 982–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Princes, E.; Said, A. The impacts of project complexity, trust in leader, performance readiness and situational leadership on financial sustainability. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 15, 619–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaffa, M.; Husain, S.H. Unravelling the Key Ingredients of Employability Skills for Surveyor Graduates: A Systematic Literature Review. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2024, 32, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamikara, P.B.S.; Perera, B.S.; Rodrigo, M.N. Competencies of the quantity surveyor in performing for sustainable construction. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 20, 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveros, J.; Vaz-Serra, P. Construction project manager skills: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Architectural Science Association, Melbourne, Australia, 28 November–1 December 2018; pp. 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera, M.; Perera, B.A.K.S.; Liyanawatta, T.N. Use of Emotional Intelligence to Enhance the Leadership Skills of Project Managers in Construction: A Qualitative Delphi Study. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2025, 17, 04525011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.T.T.; Nguyen, L.C.T.; Nguyen, T.D.N. Emotional intelligence and project success: The roles of transformational leadership and organizational commitment. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, R.F.; Liu, A.M. Research Methods for Construction; John Wiley & Sons: Bognor Regis, UK, 2015; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassell, C.; Symon, G. Raising the profile of qualitative methods in organizational research. In The Real Life Guide to Accounting Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, A.; Ruddock, L. (Eds.) Advanced Research Methods in the Built Environment; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-1405161107. [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky, H. Intuitive Biostatistics: A Nonmathematical Guide to Statistical Thinking, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–540. ISBN 9780199946648. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–1104. ISBN 9781526419514. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. How IRT can solve problems of ipsative data in forced-choice questionnaires. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louviere, J.J.; Flynn, T.N.; Marley, A.A.J. Best–Worst Scaling: Theory, Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 1–342. ISBN 9781107043152. [Google Scholar]

- Kukah, A.S.; Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Emotional intelligence (EI) research in the construction industry: A review and future directions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 4267–4286. [Google Scholar]

- Sanusi, A.N. Review of Influence of Emotional Intelligence (EI) on Collaboration Among Employees from Diverse Cultural Backgrounds in the Construction Industry. J. Adv. Artif. Intell. Eng. Technol. 2025, 1, 39–46. Available online: https://artificial-intelligence.engineering-technology.wren-research-journals.com/1/article/view/39 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

| Soft Skill Cluster | Attributes | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Communication and document control (CDC) | Verbal, written, listening | [24,26,32] |

| 2. Project reasoning (PR) | Critical thinking, decision-making | [19,59,60] |

| 3. Dispute resolution (DR) | Mediation, negotiation | [24,26,32] |

| 4. Team effort and partnership (TEP) | Teamwork, coaching, client partnership | [19,59,61] |

| 5. Project stress management (PSM) | Resilience, flexibility, adaptability | [19,24,62] |

| 6. Professional code of practice (PCP) | Professionalism, responsibility, planning | [32,35,59] |

| 7. Project yield (PY) | Initiative, productivity, time management | [18,24,59] |

| 8. Workplace ethics (WE) | Integrity, transparency, trust | [24,63,64] |

| 9. Project diversity (PD) | Cultural awareness, global citizenship | [32,34,35] |

| 10. Emotional intelligence (EI) | a. Manage own self’s emotions (EIS): self-awareness, self-control, motivation | [24,59,60] |

| b. Manage others’ emotions (EIO): empathy, leadership, social skills | [19,24,35] |

| Characteristic | Participant Demographics (N = 27) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role | Quantity Surveyor N = 13 (48%) | Project Manager N = 14 (52%) | ||||

| Gender | Male N = 19 (70%) | Female N = 8 (30%) | ||||

| Age (years) 1 | <29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60+ | |

| 7.4% | 40.7% | 40.7% | 7.4% | 3.7% | ||

| Projects completed 1 | 0–5 | 5–10 | 10–15 | 15–20 | 20+ | |

| 11.1% | 11.1% | 3.7% | 29.6% | 44.4% | ||

| Soft Skills Cluster | Quantity Surveyor (N = 13) | Project Manager (N = 14) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication and document control | 6.69 | 0.630 | 0.397 | 6.93 | 0.267 | 0.071 |

| Project reasoning | 5.85 | 0.987 | 0.974 | 6.36 | 0.745 | 0.555 |

| Dispute resolution | 6.00 | 0.913 | 0.833 | 5.93 | 0.829 | 0.687 |

| Team effort and partnership | 5.85 | 0.987 | 0.974 | 6.14 | 0.864 | 0.747 |

| Project stress management | 5.69 | 0.751 | 0.564 | 5.93 | 0.829 | 0.687 |

| Professional code of practice | 5.77 | 0.927 | 0.859 | 6.29 | 0.914 | 0.835 |

| Project yield | 5.85 | 1.068 | 1.141 | 5.86 | 0.663 | 0.440 |

| Workplace ethics | 6.46 | 0.776 | 0.603 | 6.57 | 0.514 | 0.264 |

| Project diversity | 4.77 | 1.235 | 1.526 | 4.86 | 0.949 | 0.901 |

| Emotional intelligence—self | 5.92 | 0.760 | 0.577 | 6.00 | 0.679 | 0.462 |

| Emotional intelligence—others | 5.69 | 0.947 | 0.897 | 6.57 | 0.514 | 0.264 |

| Soft Skills Cluster | p-Value | U-Statistic | H0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication and document control | 0.254 | 76.0 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Project reasoning | 0.171 | 64.0 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Dispute resolution | 0.856 | 95.0 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Team effort and partnership | 0.410 | 74.5 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Project stress management | 0.466 | 76.5 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Professional code of practice | 0.123 | 60.5 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Project yield | 0.814 | 96.0 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Workplace ethics | 0.933 | 89.0 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Project diversity | 0.760 | 84.5 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Emotional intelligence—self | 0.790 | 85.5 | Fail to reject H0 |

| Emotional intelligence—others | 0.011 | 42.0 | Reject H0 |

| Soft Skills Cluster | Number of QS Ranking the Importance of the Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Total | |

| Communication and document control | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Workplace ethics | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Dispute resolution | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Emotional intelligence—others | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Project reasoning | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Project yield/productivity | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Soft Skills Cluster | Number of QS Ranking the Importance of the Cluster | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Total | |

| Communication and document control | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Workplace ethics | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Project reasoning | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Dispute resolution | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Project yield/productivity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Emotional intelligence—others | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Reardon, B.; Heerden, A.v.; Flemmer, C. Assessment of Soft Skills for Construction Professionals in New Zealand: Perspectives from Contractor Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers. Buildings 2026, 16, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020284

Reardon B, Heerden Av, Flemmer C. Assessment of Soft Skills for Construction Professionals in New Zealand: Perspectives from Contractor Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020284

Chicago/Turabian StyleReardon, Brian, Andries (Hennie) van Heerden, and Claire Flemmer. 2026. "Assessment of Soft Skills for Construction Professionals in New Zealand: Perspectives from Contractor Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers" Buildings 16, no. 2: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020284

APA StyleReardon, B., Heerden, A. v., & Flemmer, C. (2026). Assessment of Soft Skills for Construction Professionals in New Zealand: Perspectives from Contractor Quantity Surveyors and Project Managers. Buildings, 16(2), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020284