Abstract

This systematic review maps and compares experimental strategies for estimating residual expansion in concrete elements affected by internal expansive reactions (IER), with emphasis on cores extracted from in-service structures. It adopts an operational taxonomy distinguishing achieved expansion (deformation already occurred, inferred through DRI/SDT or back-analysis), potential expansion (upper limit under free conditions), and residual expansion (remaining portion estimated under controlled temperature, T, and relative humidity, RH), in addition to the free vs. restrained condition and the diagnostic vs. prognostic purpose. Seventy-eight papers were included (PRISMA), of which 14 tested cores. The limited number of core-based studies is itself a key outcome of the review, revealing that most residual expansion assessments rely on adaptations of laboratory ASR/DEF protocols rather than on standardized methods specifically developed for concrete cores extracted from in-service structures. ASR predominated, with emphasis on accelerated free tests ASTM/CSA/CPT (often at 38 °C and high RH) for reactivity characterization, and on Laboratoire Central des Ponts et Chaussées (LCPC) No. 44 and No. 67 protocols or Concrete Prism Test (CPT) adaptations to estimate residual expansion in cores. Significant heterogeneity was observed in temperature, humidity, test media, specimen dimensions, and alkali leaching treatment, as well as discrepancies between free and restrained conditions, limiting comparability and lab-to-field transferability. A minimum reporting checklist is proposed (type of IER; element history; restraint condition; T/RH/medium; anti-leaching strategy; schedule; instrumentation; uncertainty; decision criteria; raw data) and priority gaps are highlighted: standardization of core protocols, leaching control, greater use of simulated restraint, and integration of DRI/SDT–expansion curves to anchor risk estimates and guide rehabilitation decisions in real structures.

1. Introduction

Concrete is universally recognized as the most consumed construction material worldwide, forming the fundamental basis of modern infrastructure. Given its ubiquity, the durability of reinforced concrete structures is not merely a technical requirement but a socio-economic and environmental imperative, directly linked to the safety and longevity of built assets [1]. Structures with compromised service life require early interventions, generating high maintenance and rehabilitation costs, in addition to environmental impacts resulting from disposal and replacement, since demolished concrete placed in landfills is a major concern, and rehabilitation aims to limit CO2 emissions [2]. Within this context, the construction industry has devoted significant efforts to the diagnosis, prognosis, and mitigation of factors that may act as deterioration agents in structural concrete [3]. Among the most severe damage mechanisms affecting concrete structures are internal expansive reactions, which frequently cause volumetric expansion and cracking [4,5]. Two major pathological manifestations associated with internal expansive reactions in concrete are Alkali–Aggregate Reaction (AAR) and Delayed Ettringite Formation (DEF). AAR is used here as a generic term describing reactions between alkalis in the cementitious matrix and reactive aggregates in the presence of moisture. Alkali–Silica Reaction (ASR) corresponds to the most common and practically relevant form of AAR, occurring when the reactive aggregate phase is silica [6]. ASR leads to the formation of an expansive gel that absorbs water and generates internal tensile stresses within the cement paste and at the aggregate–paste interface, resulting in cracking and progressive deterioration of concrete [7,8,9]. This review was based on previous ASR/DEF studies, systematically mapping and comparing residual expansion test protocols applied to concrete cores extracted from actual structures, identifying methodological gaps, and proposing a minimum reporting framework to improve the consistency and reliability of diagnostic and prognostic assessments in in-service structures.

Damage due to ASR originates within reactive aggregate particles and propagates into the cement paste as expansion increases [10]. DEF, on the other hand, is associated with initial curing at 65–70 °C followed by a humid service environment, a condition that promotes late ettringite reprecipitation [4,11,12,13]. This reaction corresponds to the recrystallization of secondary ettringite within the hardened cement matrix after cooling, producing internal pressures that lead to expansion and cracking [11,12,14]. Studies indicate that ASR and DEF are often observed simultaneously in the field and are regarded as coupled mechanisms [10,15,16]. Cracks resulting from one deterioration mechanism compromise the integrity of concrete and facilitate the ingress of aggressive agents, particularly due to increased water permeability [10].

The identification of these deleterious reactions in new structures is typically performed through accelerated laboratory tests [1,17,18,19], which assess the reactivity potential of constituent materials [1,6]. The Concrete Prism Test (CPT) is widely employed and regarded as the most reliable method for identifying aggregate reactivity [17,18,20]. However, the crucial challenge lies in the diagnosis and prognosis of in-service structures already exhibiting damage symptoms [10,15,21,22,23]. In these cases, evaluation must go beyond confirming the presence of a pathological manifestation—it must also determine the residual activity of the reaction [10,24]. Residual expansion is defined as the remaining potential for further expansion that may still develop in a given concrete element of a structure [10]. Its measurement is crucial, as it allows engineers not only to confirm whether the deterioration process is still active or has stabilized, but also to quantify the expected future expansion [10,19,24]. This information forms the basis for service-life predictive models, serving as a primary input for certain numerical simulation methods—particularly those aiming to predict mechanical behavior or calibrate the chemical progression of expansive reactions [5,10,15,19,24]. Moreover, it provides essential guidance for rehabilitation and repair strategies to be adopted in structures affected by internal expansion phenomena.

Despite its recognized importance for the diagnosis and prognosis of concrete structures affected by internal expansive reactions, residual expansion assessment remains methodologically heterogeneous [10,24,25,26]. Most experimental strategies reported in the literature are adaptations of laboratory-based tests originally developed for aggregate reactivity or mixture qualification [1,8,19], and their transfer to concrete cores extracted from in-service structures is often performed without standardized procedures or consistent boundary conditions [10,24,27]. This situation leads to significant variability in test conditions, interpretation criteria, and reported results, particularly when core extraction, stress release, and conditioning effects are involved. As a consequence, comparability across studies is limited and the reliability of prognostic assessments based on core testing remains uncertain [24,27], motivating the need for a systematic synthesis of existing methodologies with specific attention to core-based residual expansion measurements.

Although the title of this review emphasizes residual expansion measured in concrete cores, it should be highlighted that only a limited number of studies explicitly address this issue. This scarcity is not incidental, but reflects a fundamental gap in the current state of the art. Most experimental procedures used to estimate residual expansion in cores are derived or adapted from ASR/DEF laboratory test protocols, originally developed for evaluating aggregate reactivity or mix qualification. Consequently, a critical discussion of these general test structures is necessary to properly interpret their applicability, limitations, and inherent biases when transferred to core-based investigations. In this context, the present review deliberately combines an analysis of conventional ASR/DEF experimental protocols with a focused synthesis of studies that have performed residual expansion measurements on cores extracted from in-service structures. This approach allows the identification of methodological inconsistencies, highlights the lack of standardized procedures for cores, and reinforces the need for protocols specifically designed for the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of real concrete structures.

To address this gap, the main objective of this study is to analyze and synthesize, through an SLR following the PRISMA protocol [28], the experimental strategies used to identify and quantify residual expansion in concrete cores extracted from in-service structures, mapping testing techniques, conditions, and their limitations. Specifically, this review seeks to answer the following research questions that guided data extraction and analysis:

- What is the state of the art of experimental strategies used to identify residual expansion in concrete cores?

- What contributions and limitations do authors report regarding the applicability of these methods?

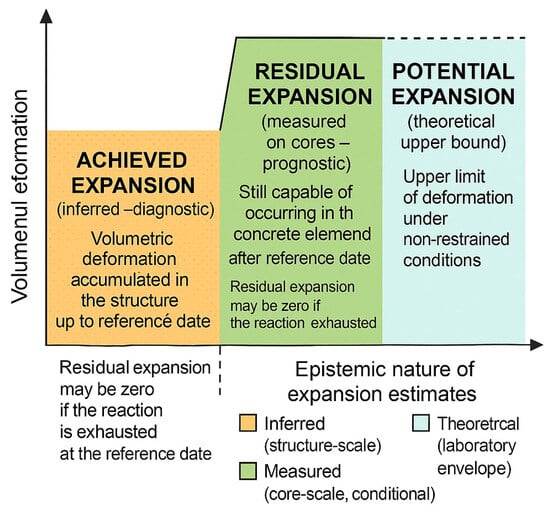

Finally, to avoid terminological ambiguity and align diagnostic and prognostic interpretation, three complementary concepts were adopted to define the expansion triad as follows:

- Achieved expansion (already occurred): volumetric deformation accumulated in the structure up to the date of core extraction. It is not directly measured but estimated through mapping and back-analysis, serving to characterize the current state of damage.

- Potential expansion (total free): upper limit of deformation under non-restrained conditions, at temperature and humidity favorable to reaction (typically via accelerated tests). It expresses the maximum reactive capacity of the aggregate–binder system when kinetics is not limited by mechanical restraint.

- Residual expansion: the remaining portion still capable of occurring in the in-service concrete element after the reference date. It is estimated by monitoring cores under controlled conditions (temperature, relative humidity, storage medium)—under free and/or simulated restrained regimes—and serves a prognostic purpose, supporting risk projection and intervention decisions.

In order to avoid terminological ambiguity and to clarify the distinct diagnostic and prognostic roles of the achieved–potential–residual expansion triad, Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of their conceptual and epistemic relationships. The diagram explicitly distinguishes inferred, measured, and theoretical quantities, highlights the reference date associated with core extraction, and illustrates how total expansion capacity may be partitioned into already mobilized and remaining components.

Figure 1.

Conceptual representation of achieved, residual, and potential expansion in concrete affected by internal expansive reactions.

2. Methodology

This Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted in strict accordance with the PRISMA protocol [28], ensuring transparency, traceability, and reproducibility of results.

2.1. Definition and Research Questions

The scope of the SLR was defined using the PICo acronym (Population, Interest, Context), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Population, interest, and the SLR context.

The review was guided by the two research questions, presented above in Section 1, which directed data extraction and synthesis.

2.2. Search Strategy and Data Sources

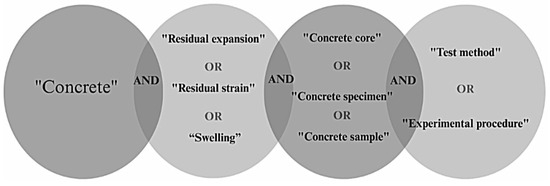

The systematic search was carried out in October 2025 across major international databases relevant to Civil Engineering: ScienceDirect, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search strategy combined keywords and Boolean operators to capture studies addressing the intersection of residual expansion, field testing, and experimental methodologies. The generic search string used was as follows, and presented in Figure 2, which summarizes the search string used.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the search string used in the SLR (Source: the authors).

No time period or language restrictions were applied to the initial search. Results were refined to include primarily peer-reviewed journal papers.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

Study selection followed a two-phase sequential screening protocol applying one Inclusion Criterion (IC) and eight Exclusion Criteria (EC). IC1 referred to studies addressing tests or experiments for identifying expansion in concrete; ECs are detailed in Table 2, showing the criteria used in each screening stage.

Table 2.

Exclusion criteria used in article screening.

In the first screening, titles, abstracts, and keywords of all retrieved papers were reviewed. Papers meeting EC1–EC4 were excluded. The second screening involved a full-text review, applying EC5–EC8 to eliminate studies outside the scope of the SLR. All screening was performed using the Rayyan software [29], and the included studies were managed in Zotero [30].

2.4. Selection Flow

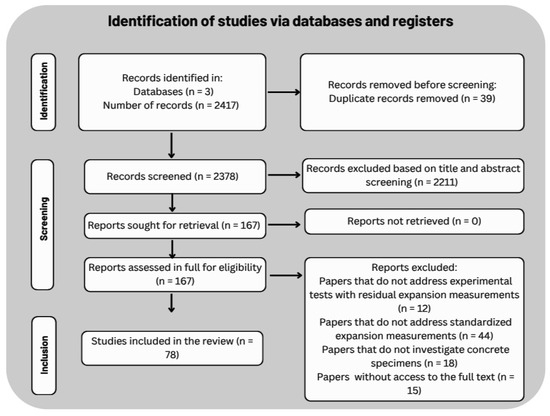

The complete PRISMA flowchart depicting study identification and inclusion, from initial database search to final selection, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

PRISMA Flowchart (Source: the authors, adapted from [28]).

A total of 2417 records were identified across the three databases. Metadata from all records were downloaded in BibTeX format and imported into Rayyan for screening. Initially, 39 duplicates were removed, leaving 2378 records for title and abstract screening. In the title and abstract review, 2211 papers were rejected, and 167 were retrieved. After full-text review, 78 papers were included in the SLR.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data from the 78 included papers were compiled into a spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel. The extracted items and their methodological purposes are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Items used in data extraction and their descriptions.

2.6. Limitations of the SLR

Although the systematic review process followed structured and reproducible criteria, some methodological limitations must be acknowledged. The main one concerns the heterogeneity of the included studies, which presented significant variations in experimental conditions, measurement techniques, and normative criteria, making a direct quantitative comparison of expansion results unfeasible. For this reason, a qualitative and descriptive approach was adopted, focused on identifying methodological trends and standardization gaps.

In addition, the terminological and symbolic diversity employed by the authors, especially in the way of citing norms, assays, and pathological manifestations, demanded a manual process of standardization and categorization of the data, susceptible to minor subjectivities. Another limitation refers to the unequal availability of information in the papers, since not all report expansion values, exact assay conditions, or limitations recognized by the authors themselves. During the database searches, only scientific papers from journals were included; however, the review did not restrict language, publication period, or country of origin, ensuring broad international and temporal coverage. Thus, the set of 78 studies analyzed is considered to offer a representative and robust overview of strategies for measuring residual expansion in reactive concretes.

3. Results

The analysis of the 78 papers included in the SLR was carried out in three stages: (a) general characterization, (b) method analysis, and (c) evaluation of results and limitations, encompassing the pathological manifestations and the types of expansion measured in the studies.

3.1. General Characterization of the Scientific Production

The general characterization identifies when the studies were conducted, where they originated, and which deterioration mechanisms they address, thereby contextualizing the relevance of residual expansion in concrete cores.

3.1.1. Temporal Evolution and Geographic Origin

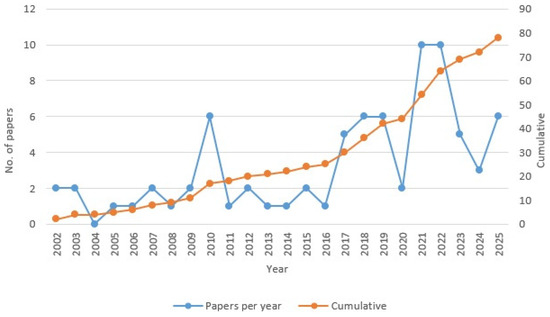

The temporal distribution of the included papers (see Figure 4) shows that research on residual expansion in concrete cores emerged in the early 2000s with a low annual output, followed by a gradual increase and periods of more intense activity. A first marked rise occurs around 2010, and a second, more pronounced growth phase begins in 2017. The years 2021 and 2022 correspond to the highest annual counts, with 10 papers each, and the cumulative curve indicates that approximately 62% of all publications (48 out of 78) were produced from 2018 onward. This pattern highlights the consolidation and growing relevance of residual expansion in concrete cores as a research topic in recent years. The cumulative curve shows a slow initial growth followed by a marked acceleration from 2017 onward, indicating that most of the publications on residual expansion in concrete cores have been produced in the last few years.

Figure 4.

Temporal evolution of publications on residual expansion in concrete cores from 2002 to 2025.

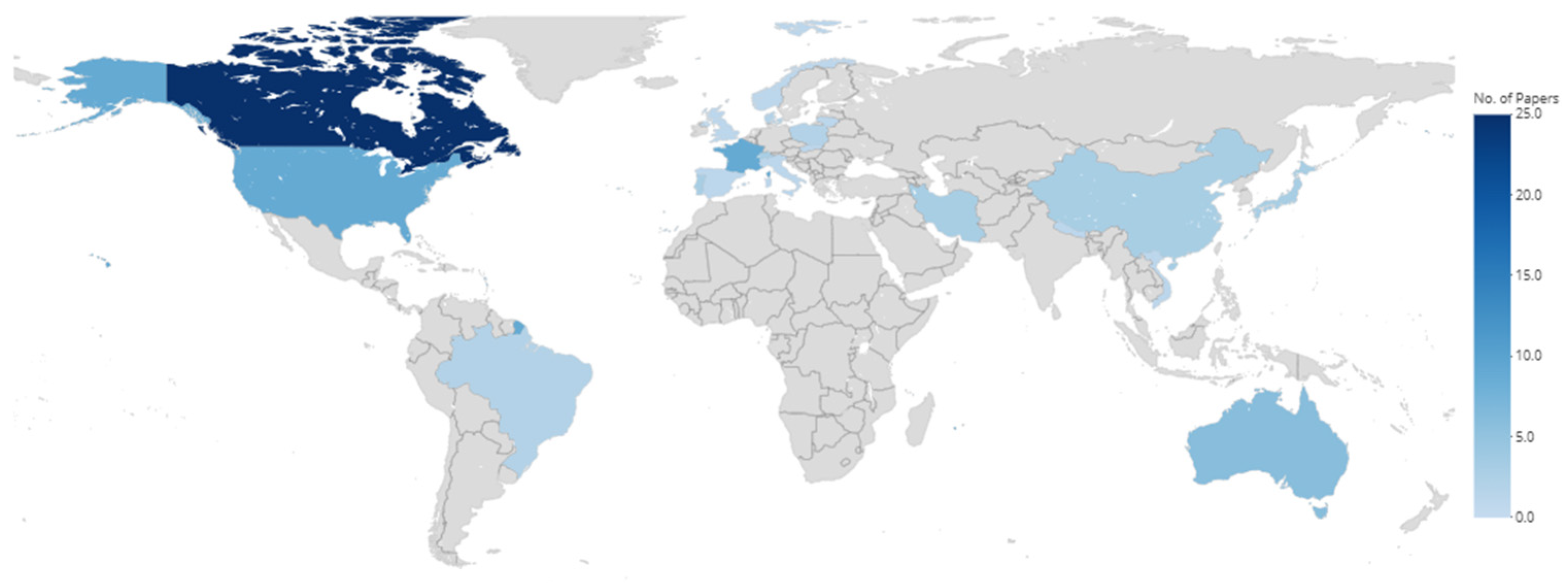

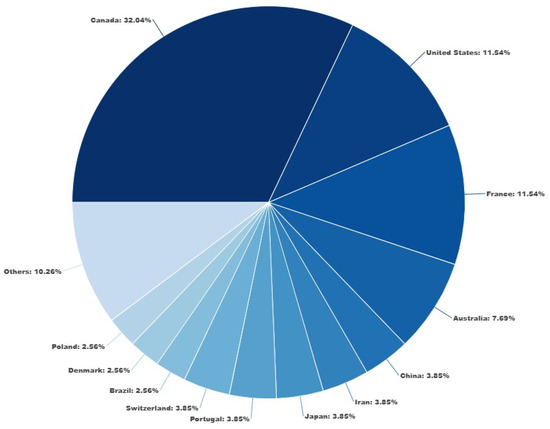

In terms of geographic distribution, Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the spatial distribution of corresponding authors’ institutional affiliations.

Figure 5.

Map showing the distribution of papers by country of the corresponding author institution.

Figure 6.

Pie chart showing the percentage of papers published by country.

The scientific production is concentrated mainly in countries with a strong tradition in infrastructure research and studies on expansive reactions, particularly those related to ASR. Canada, France, and the United States are the leading contributors. Canada accounts for approximately 32% of all studies—reflecting its historical engagement in ASR monitoring of transportation and energy infrastructure since the 1980s, which positioned the country as a global reference in diagnostic and mitigation protocols [6,8,35,36]. France and the United States also stand out due to the integration of research centers with public infrastructure agencies, which promotes applied research on concrete asset management [10,20,24,37,38]. On the other hand, there is still limited representation from Latin American, Asian, and African countries, revealing a geographical gap in the recent literature.

This temporal and geographic distribution not only demonstrates the maturity of research on expansion phenomena in concrete but also confirms the consolidation of specialized research centers driving scientific progress in this area.

3.1.2. Keywords and Journals

Keyword analysis reinforces the main conceptual axes structuring the research field on expansion in concrete cores. Figure 7 presents the word cloud generated from the most frequent author-provided terms in the 78 studies.

Figure 7.

Keyword cloud from the included SLR papers.

The most recurrent terms were reaction, concrete, expansion, alkali, ASR, alkali–silica, aggregate, and damage, reflecting the predominance of studies focusing on ASR and DEF mechanisms and expansion damage assessment methods. Terms such as sensor, strain, test, and LVDT highlight the prevalence of laboratory-based approaches, while others such as porosity, pore, and permeability indicate a concern with microstructural characteristics.

This diversity shows that the literature combines both physicochemical and mechanical approaches, ranging from microstructural characterization of reaction products to instrumentation and monitoring of expansion behavior.

Publication patterns reveal strong concentration in journals focused on cementitious materials and concrete durability. Table 4 summarizes the journals where the included studies were published, indicating the number of papers and total citation counts.

Table 4.

Main journals publishing studies on concrete expansion.

Construction and Building Materials, Cement and Concrete Research and Cement and Concrete Composites together account for 90% of the articles mapped in Table 4, which confirms the central role of these three journals in disseminating experimental research on expansive mechanisms, testing protocols and predictive degradation models in concrete structures. Construction and Building Materials is by far the most prolific outlet, concentrating 45% of the sample (35 papers), which reflects its profile as a broad, application-oriented journal for materials and structural performance studies. Cement and Concrete Research and Cement and Concrete Composites, with 33% (26 papers) and 12% (9 papers) of the publications, respectively, complement this picture by attracting more specialized contributions on microstructural aspects, mechanistic modeling and durability-oriented investigations.

However, productivity does not coincide with scientific impact. While Construction and Building Materials accumulates 658 citations (18.8 citations per article), Cement and Concrete Research reaches 1950 citations, corresponding to an average of 75 citations per paper—four times higher—indicating that this journal concentrates the most influential and often more fundamental contributions, including works that refine the relationship between expansion and damage and validate new experimental procedures. Cement and Concrete Composites also stands out with 39 citations per article, above the global mean. At the other extreme, NDT&E International presents the highest average number of citations (92) but with only a single paper in the sample, representing an isolated yet highly visible contribution rather than a consolidated publication trend. When all 78 papers are considered, the set of journals totals 3114 citations, which corresponds to an overall mean of approximately 39.9 citations per article. This correlation between publication frequency and citation patterns shows that research on expansion in concrete cores is strongly concentrated in a small group of specialized journals that simultaneously organize the scientific production and define the main arenas of visibility and impact in this field.

3.2. Pathological Manifestations

The literature survey reveals a marked predominance of Alkali–Silica Reaction (ASR), which appears as the main degradation mechanism in 65 of the 78 papers (83.33%). This massive participation confirms that ASR, because of its global occurrence and diagnostic complexity, is still the primary motivation for developing and refining strategies to identify internal swelling in concrete cores.

Delayed Ettringite Formation (DEF), although recognized as a severe expansive mechanism, was the exclusive focus of only eight studies (10.26%), while five papers (6.41%) addressed ASR and DEF jointly, either in combined or comparative approaches.

This distribution shows that the methodological debate on residual expansion tests is largely shaped by ASR-driven case studies, with DEF appearing mostly as a complementary or concomitant process.

In these studies, ASR and DEF are consistently identified as the main drivers of internal swelling in concrete structures, and frequently occur in combination [10,13,15]. A recurrent finding in the literature is the synergistic interaction between these mechanisms: alkali–silica gel formation and ASR-induced cracking enhance ionic mobility and water ingress, thereby promoting or accelerating the development of DEF [10,13].

Environmental conditions and material composition strongly modulate the occurrence and severity of both mechanisms. For instance, initial thermal treatment at elevated temperatures (≥65–80 °C) is a critical prerequisite for DEF development, whereas sodium hydroxide release from specific aggregates exacerbates ASR-related expansion [13,24,39]. In massive concrete elements, alkali leaching—although unfavorable to AAR by reducing one of the reactants—can act as a trigger that accelerates DEF, amplifying damage through cracking and leading to expansion patterns and anisotropic behavior that differ markedly from those observed in small laboratory specimens [24].

Expansion and cracking measurements are essential to assess the level and extent of damage, as well as to distinguish microscopic cracking patterns: ASR typically initiates within aggregate particles, whereas DEF-related cracks concentrate in the interfacial transition zone and cement paste [10,13]. This distinction is crucial, because the choice of residual expansion protocols, test conditions, and the interpretation of their limitations depends strongly on the type of reaction present in the material.

3.3. Type of Expansion Measured

The studies included in this review measured different types of expansion, depending on the degree of mechanical restraint imposed and on whether the testing program had a primarily diagnostic or prognostic objective.

3.3.1. Restrain State

The restraint state refers to the mechanical boundary conditions under which expansion develops and is measured in concrete structures.

Two mechanical boundary conditions were identified: free and restrained expansion. However, none of the studies investigated a purely restrained condition in isolation. To standardize the interpretation and reporting of expansion tests, the following definitions are adopted:

- Free expansion: measurement performed without any applied mechanical restraint—a typical laboratory condition in which the specimen can deform freely. Examples include bars or cylinders stored at controlled temperature and relative humidity, or immersed in water or alkaline solutions, with or without sealed faces and without any confining devices;

- Restrained expansion: measurement performed under mechanical confinement (such as existing reinforcement, external jackets, or test frames), which reduces the rate and magnitude of expansion and may induce anisotropic strain. Examples include cores tested within restraining frames or reinforced specimens designed to simulate the confinement conditions of real structures.

Most studies focused on free expansion, which accounted for 76% of the sample (59 of the 78 papers). The remaining 24% (19 papers) evaluated free and restrained conditions simultaneously.

Free expansion is typically measured in unrestrained concrete specimens stored under controlled laboratory conditions [3,10,19,40]. It is a key input parameter for chemo-mechanical predictive models [8]. As expected, free expansion values are systematically higher than restrained ones, since mechanical confinement limits both reaction kinetics and overall strain development [5]. When residual expansion testing is performed before the onset of IER, the measured strain describes the complete free expansion curve [10].

Restrained expansion occurs in reinforced concrete elements, where confinement influences both the physical and chemical development of expansion [5,40]. The restraint reduces both the rate and the final magnitude of expansion when compared with freely expanding specimens [5,40,41]. Furthermore, restraint induces anisotropic behavior, meaning that expansion redistributes toward the less confined directions [5,8,23,26,40,41].

Studies that compared free and restrained expansion focused primarily on quantifying the effect of confinement on IER development [15,24,42]. For example, Zahedi et al. [40] showed that unconfined samples exhibit faster expansion than restrained blocks. This dual approach is crucial for evaluating rehabilitation strategies—such as external wrapping with fiber-reinforced concrete—that impose external restraint to limit residual expansion, demonstrating that confinement effectively reduces the damage potential [43,44].

3.3.2. Diagnostic vs. Prognostic Expansion

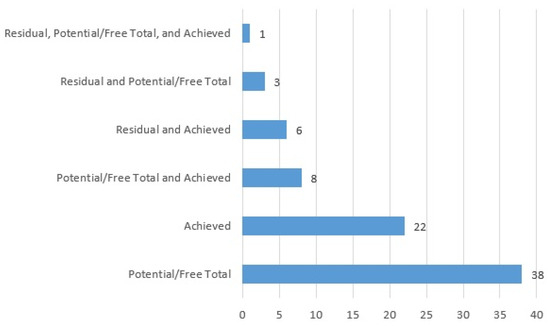

Based on the expansion taxonomy defined in Section 1, the reviewed studies measured achieved, potential, and residual expansion according to distinct diagnostic and prognostic objectives [10,15,19] are represented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Number of studies by type of expansion measured for diagnostic and prognostic purposes.

This classification reflects the stage of reaction development and is commonly used to assess both the current condition and the future deterioration of affected structures [10,15,19]. Most studies (38 of 78) focused on potential/free total expansion, also referred to as ultimate expansion or expansion at infinity. This parameter represents the total free deformation that the material can reach if the reaction proceeds to completion without mechanical restraint [3,10,19,45]. Such tests usually define the upper bound of material reactivity and are crucial for kinetic modeling [24].

Residual expansion refers to the remaining potential for expansion in a structure already affected by IER, measured on cores extracted from in-service concrete and stored under controlled temperature and humidity conditions. This parameter supports prognostic assessment, helping to determine whether damage is likely to progress or has stabilized [10,15]. Achieved expansion represents the cumulative deformation that has already occurred in the structure. It is not measured directly but is instead estimated from diagnostic indices or by subtracting residual expansion from the total free potential expansion. Diagnostic tools such as the Damage Rating Index (DRI) and the Stiffness Damage Test (SDT) are frequently employed to quantify the degree of current expansion-related damage [10,15,19,23]. The DRI quantifies microcrack density and reaction features on polished surfaces under microscopy, whereas the SDT measures stiffness degradation caused by internal cracking, thereby reflecting cumulative damage. Together, these indicators enable the estimation of achieved expansion in field structures.

The investigation of total potential/free expansion primarily aims to establish the upper deformation limit of the material, which is essential for modeling and forecasting structural behavior in the field. Table 5 summarizes the objectives and the papers in the RSL that measured total potential/free expansion alone or in combination with residual and achieved expansion, and highlights four representative studies used as reference cases for the subsequent analysis.

Table 5.

Groups of studies, organized by objective, that addressed the measurement of potential/total free expansion.

In the study reported by De Grazia et al. [3], a new semi-empirical approach based on the Larive model was proposed to provide a comprehensive description of unrestrained, laboratory-induced expansion. The objective was to predict ultimate expansion and ASR kinetics over a wide range of materials and exposure conditions without the need for case-by-case calibration. In contrast, Al-Jabari et al. [61] measured potential/total free expansion using the Concrete Prism Test (CPT) to evaluate the performance of concrete mixtures with and without a modified crystalline admixture. Their main goal was to assess the effectiveness of the admixture in mitigating ASR-induced expansion and concrete deterioration by comparing mixture performance against a 0.1% expansion limit. The research conducted by Jabbour et al. [24] compared potential/total free expansion with residual expansion in cores extracted from massive structures, allowing the authors to obtain the achieved expansion by subtracting residual from potential expansion. This relationship proved fundamental for predicting the remaining service life of the structure and for selecting appropriate rehabilitation strategies. In turn, the study by Olajide et al. [66] measured potential/total free expansion incrementally in laboratory specimens (producing an expansion kinetics curve) and directly correlated it with achieved expansion at specific levels (0.05%, 0.12%, 0.20%, and 0.30%). The objective was to quantify microscopic and mechanical damage using tools such as the Damage Rating Index (DRI) and the Stiffness Damage Test (SDT), thereby enabling these indices to be used to classify deterioration levels (from negligible to very high) according to the degree of achieved expansion.

Achieved expansion represents the cumulative damage already sustained by the concrete. Among the 22 papers in the SLR that measured this parameter, it was almost always used as a quantitative reference for diagnostic purposes—that is, to correlate the macroscopic deformation level with internal (microscopic and mechanical) damage and with the structural consequences of the reaction. Sanchez et al. [22] measured achieved expansion at discrete levels (0.05%, 0.12%, 0.20%, and 0.30%) to determine the optimal loading level (40% of compressive strength) for the SDT, ensuring that the test could reliably distinguish different degrees of internal damage (microcracking) as expansion progresses. In the study reported by Zahedi et al. [40], achieved expansion was measured in concrete blocks at levels of 0.08%, 0.15%, and 0.25% to correlate surface cracking (via DRI) with internal damage under various confinement configurations, with the aim of establishing an empirical model linking the surface cracking index to the actual degree of internal damage. Conversely, Macioski et al. [68] measured achieved expansion to validate novel optical monitoring techniques based on Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors embedded at different locations, correlating sensor readings with SDT and DRI damage indices obtained from the specimens. Table 6 summarizes the groups of studies that measured achieved expansion according to their specific objectives.

Table 6.

Groups of studies, organized by objective, that addressed the measurement of achieved expansion.

Studies that simultaneously measured residual and achieved expansion aimed to provide a comprehensive diagnostic and prognostic assessment of structures affected by Internal Swelling Reactions (ISR). The works of Martin et al. [10] and Custódio and Ribeiro [15] focused on the integrated diagnosis and prognosis of in-service structures, treating achieved expansion as a quantitative indicator of existing damage and residual expansion as the potential for future deterioration. Specifically, Martin et al. [10] combined residual expansion results with the Stiffness Damage Test (SDT) and Damage Rating Index (DRI) to determine the current damage level and, crucially, to estimate the achieved expansion prior to core extraction, by subtracting the residual expansion from the total potential expansion of the material. Similarly, Custódio and Ribeiro [15] conducted a comprehensive experimental campaign on an underground passage, applying residual expansion tests for both ASR and DEF on extracted cores to assess the probability of continued expansion. They also used SDT parameters to estimate the total unrestrained achieved expansion up to the date of the investigation, providing an order of magnitude of the associated dimensional variation.

In another line of research, Kubat et al. [43], and Diab et al. [42,44] measured both achieved and residual expansions to evaluate the effectiveness of external reinforcement and mitigation measures in concrete damaged by ASR. In these studies, the degree of expansion at the time of strengthening was identified as critical, exerting a greater influence on structural performance than the mechanical properties of the reinforcement materials themselves. These authors emphasized that the level of achieved expansion governs the appropriate timing of intervention, and that early application of confinement leads to a greater reduction in subsequent expansion of subsequent expansion. They also highlighted that monitoring residual expansion is essential to assess the effectiveness of confinement systems in suppressing remaining expansion. A further study was provided by Boukari et al. [75], who used residual expansion measurements on field-extracted cores to validate new monitoring tools, including nonlinear acoustic testing and physicochemical analysis of aggregates to detect additional internal damage. Their work correlated the progressive expansion achieved, measured in laboratory specimens, with the expansion observed in residual expansion tests, thereby confirming the specific contribution of ASR to the measured expansion and damage.

Finally, the integration of all three expansion categories (achieved, residual, and potential) was highlighted in the study by Piersanti and Shehata [35], which investigated the feasibility of using Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA) sourced from ASR-damaged structures. In this work, the achieved expansion was interpreted as the pre-existing damage level in the original highway barriers, which were classified into high-deterioration and low-deterioration groups. The objective was to compare the reactivity of RCA as a function of the damage level in the parent structure. Residual expansion was then measured on cores extracted from these damaged barriers, monitoring their deformation under laboratory conditions (38° C and 100% RH) to determine whether expansion in the original structures was still ongoing. Results showed that cores from low-deterioration barriers exhibited higher residual expansion rates than those from highly deteriorated ones, suggesting that extensive cracking in severely damaged cores may have allowed ASR gel to exude, thereby reducing the remaining expansion potential.

3.4. Testing Techniques and Standards for Measuring Expansion

The analysis of the included studies revealed a wide variety of experimental methodologies for measuring residual expansion in concrete. However, most investigations were based on specimens cast under laboratory conditions rather than on cores extracted from existing structures. Of the 78 studies analyzed, only 14 performed tests on cores taken from real structures, underscoring a significant gap in field-oriented research. This finding reflects both the lack of an international standardized protocol and the coexistence of adapted laboratory procedures. This section consolidates the testing techniques identified in the review performed, grouping them by normative family, test type, geographical prevalence, and experimental features.

3.4.1. Normative Distribution and Test Families

The review confirms the coexistence of multiple normative for evaluating expansion in concrete. This variety highlights the absence of a unified global standard and the emergence of region-specific experimental traditions shaped by local materials and environmental conditions. Figure 9 shows the normative families and their geographical origins.

Figure 9.

Normative families and their geographic origins.

The standards for evaluating the reactivity in cementitious materials and aggregates comprise a broad set of international protocols, with North American methods and European recommendations standing out as the most prominent [1,19]. Among these, the ASTM and RILEM protocols are the most widely used internationally.

In North America, the ASTM C1293 method [31] (Concrete Prism Test, CPT) is widely used to characterize the Alkali–Aggregate Reaction (AAR) [7,16,18,61,64]. This is a long-term test, typically lasting from one to two years, in which concrete prisms are cured at 38° C and 100% relative humidity, with the cement alkali content often adjusted to 1.25% Na2Oeq (sodium oxide equivalent). An expansion limit of 0.04% after one year is conventionally adopted as indicative of non-reactivity [1,2,9,17,18,23,61,63]. Overall, the wide range of expansion testing methods illustrates the complexity of predicting Internal Expansive Reactions (IERs) in concrete. In addition to direct expansion measurements, the literature also reports advanced diagnostic methods such as the Damage Rating Index (DRI) and the Stiffness Damage Test (SDT), which quantify microscopic and mechanical damage, respectively.

Canadian standards often closely follow ASTM protocols—for example, CSA A23.2-14A [32], which is analogous to the CPT [8,34]. In the European context, RILEM recommendations define key methods for assessing potential reactivity:

- RILEM AAR-2 [76], originally defined as an accelerated mortar bar test similar to ASTM C1260 [77], was used by [78] to evaluate expansion and strength of concrete specimens affected by AAR.

- RILEM AAR-3 [33] uses concrete prisms stored at 38 °C to assess aggregate combinations [37,79]

- RILEM AAR-4.1 [80] is an accelerated concrete prism test performed at 60 °C; expansions below 0.03% after 15–20 weeks indicate non-reactive aggregate combinations [79].

- RILEM AAR-12 [81] was developed to assess ASR performance under simulated service conditions, including exposure to de-icing solutions and humidity cycles at 60 °C [60].

Other countries and international entities have also proposed standardized methods. The British Standard BS 812-123 [82] specifies the monitoring of concrete prism expansion at 38 ± 2 °C [83]. The French school is represented by the Laboratoire Central des Ponts et Chaussées (LCPC) procedures, including LCPC No. 44, and LCPC No. 67 [84,85], which provide testing methods for residual expansion in concrete cores [10,15,24]. The Japanese Standard JIS A6202 [86] establishes a protocol for measuring deformation in prismatic specimens under restrained conditions, using metal bars with screw threads to simulate different levels of confinement [87]. In Brazil, the standard NBR 15577-6 [88] is dedicated to determining expansion in concrete prisms [16,68].

In addition to standardized protocols, several local and experimental methods have been proposed to overcome the limitations of conventional tests, particularly problems associated with alkali leaching and excessive test duration [19,49]. The Norwegian Concrete Prism Test (NCPT) defined in publication NB32 [89], uses larger prisms than the CPT (100 × 100 × 450 mm3), is performed at 38 °C, and is applied both for aggregate classification and performance testing [1,49,79]. The Alkali-Wrapped Concrete Prism Test (AW-CPT) is an innovative method in which the specimen is wrapped with an alkali-saturated fabric, to prevent alkali leaching and moisture loss [27]. Together, these various methods illustrate the complexity of predicting internal expansive reactions (IERs) in concrete and the lack of comprehensive harmonization in global testing approaches.

To enhance clarity and provide a synthetic overview of the main normative frameworks discussed above, Table 7 presents a comparative summary of the key experimental features, objectives, and applicability of the ASTM, CSA, RILEM, and LCPC protocols used to assess expansion associated with internal expansive reactions in concrete.

Table 7.

Comparative summary of major international protocols used to assess expansion associated with internal expansive reactions in concrete.

This comparison highlights that most international standards were originally developed for laboratory specimens and aggregate qualification, whereas only the LCPC procedures were explicitly conceived for residual expansion assessment in concrete cores extracted from in-service structures.

It is important to note that testing methodologies that use concrete cores are also highly diverse, mostly adopting protocols that attempt to accelerate the remaining chemical potential. Table 8 presents the 14 studies included in this SLR that performed core extraction from structures in service and the corresponding standards applied in their tests.

Table 8.

Standards adopted in the 14 studies that performed core extraction.

The results show that the most frequently used standard is CSA A23.2-14A [32], corresponding to the Concrete Prism Test (CPT), followed by the ASTM C1293 standard [31]. The CPT conditions are often adapted for core specimens, reproducing exposure at 38 °C and high relative humidity, frequently with the cement alkali content increased to 1.25% Na2Oeq. The LCPC No. 44 and LPC No. 67 protocols [84,85], French standards applied to ASR and DEF, respectively, are the third most commonly used methods. These are specific residual expansion tests, essential for prognostic assessment and for estimating the total expansion achieved by concrete up to the date of core extraction. Such dimensional measurements on cores are fundamental for reducing the discrepancy between laboratory and field behavior and are often complemented by advanced diagnostic tools applied to the extracted samples, such as the Damage Rating Index (DRI) and the Stiffness Damage Test (SDT).

3.4.2. Comparative Experimental Parameters of Core-Based Residual Expansion Tests

Table 9 presents a detailed comparative synthesis of the experimental parameters adopted in the 14 investigations that performed residual expansion tests on concrete cores extracted from in-service structures. The table systematically consolidates information on core geometry and extraction characteristics, specimen orientation when reported, conditioning environment, test temperature, relative humidity or storage medium, alkali leaching control strategies, restraint conditions, test duration, and the main methodological limitations explicitly discussed by the authors. By organizing these parameters side by side, the comparison enables a direct assessment of how methodological choices influence residual expansion measurements and their interpretation. The synthesis clearly reveals a pronounced heterogeneity in experimental practices, even among studies addressing similar pathological mechanisms. This finding highlights the absence of an internationally standardized framework specifically designed for the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of residual expansion in concrete cores extracted from actual structures.

Table 9.

Experimental parameters adopted in residual expansion tests performed on concrete cores.

Although no standardized experimental design currently allows the isolated quantification of extraction-related effects, several of the core-based studies summarized in Table 9 qualitatively report that drilling-induced microcracking, stress release upon coring, and core orientation relative to in situ restraint conditions can influence residual expansion measurements, either by modifying internal stress states, promoting early ASR gel exudation, or inducing anisotropic expansion behavior. Stress release during coring is frequently cited as a critical issue, as it may promote early ASR gel exudation at the core surface and modify internal stress states, potentially leading to an underestimation of the remaining expansion potential. This effect is discussed, for example, by Martin et al. and Piersanti and Shehata, who observed gel exudation shortly after extraction in highly deteriorated cores, suggesting that stress liberation can alter subsequent expansion kinetics.

3.5. Reported Limitations in Core Testing

The limitations reported by the authors across the analyzed studies highlight significant challenges in testing and measuring expansion in concretes, ranging from sample representativeness to the sensitivity of diagnostic techniques. Most studies recognize that laboratory tests on small-scale specimens under controlled free-expansion conditions do not adequately reproduce the behavior of real structures [1,8,13,18,24,75]. Zahedi et al. [40] and Jabbour et al. [24] observed that the expansion data obtained under “free and accelerated expansion” conditions are not necessarily applicable to concrete cores extracted from aged in-service structural members. In real structures, mechanical restraints and service stresses induce anisotropic expansion—that is, reduced deformation in confined directions and greater strain along less-restrained axes [1,3,5,8,13,23,24,26,38,40,41].

Another major group of limitations is related to experimental conditions and normative adaptations. Accelerated tests using high temperatures and concentrated alkaline solutions—although useful for rapid screening—may overestimate potential reactivity and induce degradation mechanisms that differ from those observed in field conditions [19,27,35,52,53,54,61,63]. For aggregates with low or moderate reactivity, the Accelerated Mortar Bar Test (AMBT) may yield misleading results. In the Accelerated Concrete Prism Test (ACPT), excessive acceleration and temperature of 60 °C or higher can promote alkali leaching, leading to reduced expansion measurements [17,63,64]. Kawabata et al. [27] also observed that high temperature may promote ASR gel exudation, resulting in lower measured fine expansion. In addition, the short testing duration of AMBT may not be enough to properly assess the efficiency of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as fly ash, which exhibit slower reaction kinetics [7,49].

On the other hand, long-term tests, such as the Concrete Prism Test (CPT), although widely considered the most reliable method, are not suitable for the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of structures in service due to their long duration and the phenomenon of alkali leaching. Small concrete prisms are more susceptible to alkali loss than large field structures [1,17,18,19,24,41,49,57,68]. Lindgård et al. [49] reported that concrete prisms may lose 3–20% of their alkalis within the first four weeks and up to 50% after one year of exposure, leading to an underestimation of the true reactivity potential. This leaching results in a flattening or premature stabilization of the laboratory expansion curve, even when reactive species have not been fully consumed. In addition, CPT expansion is highly temperature-sensitive, and variations in the curing environment may significantly affect reaction kinetics.

Regarding the preparation and instrumentation of test specimens, uncertainties arise from heterogeneity and microcracking induced during core extraction. Drilling can generate microcracks that modify transport properties [24,35], particularly when high drill rotational speeds are used. Furthermore, the extraction of the core from a confined structure causes stress release [10], which can lead to ASR gel exudation on the core surface within a few hours, providing visual evidence of stress liberation [25]. Stress release is reported by several authors as one of the factors that may cause deviations in assessing the “true residual expansion” of concrete.

4. Conclusions

This systematic literature review compiled and critically analyzed the main experimental strategies used to estimate residual expansion in concrete, with particular emphasis on methods applied to cores extracted from existing structures. A total of 78 scientific papers were identified, but only 14 directly involved core-based testing. This imbalance is not merely quantitative, but reflects a methodological gap in the literature, since residual expansion in concrete cores is predominantly evaluated using laboratory-derived RAS/DEF protocols, which were not originally designed for core testing. This dependence highlights the lack of internationally standardized procedures specifically calibrated for the diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of concrete structures in service, under realistic mechanical and environmental conditions.

This review showed that, despite extensive research on internal expansive reactions, the term “expansion” is still frequently used in a generic way, without specifying either its nature or the associated mechanical boundary conditions. To address this, a threefold taxonomy was proposed, distinguishing achieved, potential and residual expansions, under free or restrained conditions, with the aim of standardizing terminology and improving comparability among studies. The analysis also confirmed the coexistence of multiple normative frameworks (ASTM, CSA, RILEM, LCPC), with no global consensus on residual expansion testing. Canadian and French protocols (CPT and LCPC 44/67) stand out in core-based applications, largely due to their reproducibility and successful field deployment, but their predominance underscores a pattern of regional fragmentation rather than harmonization.

Experimental conditions were found to vary widely, particularly regarding temperature, relative humidity and alkaline concentration, as well as strategies for leaching control. The review highlights that effective sealing or wrapping and well-defined T/RH conditions are essential to obtain comparable and interpretable results. Free expansion tests clearly dominate the literature, even though they do not reproduce the mechanical restraint typical of real structures; only a limited number of studies explicitly simulate restraint, despite its importance for realistic prognosis in reinforced and prestressed concrete. The combined use of residual expansion testing with DRI and SDT emerges as a promising diagnostic–prognostic framework, increasing the reliability of expansion models and supporting better-informed decisions on maintenance and intervention in existing structures. At the same time, the quality of reporting remains a critical weakness: key test variables are often missing, which hinders reproducibility and meta-analysis. In response, this review proposes a minimum reporting checklist for residual expansion tests. Finally, the synthesis of the literature points to clear research priorities: the development of a standardized protocol for cores, the integration of chemo–mechanical modeling for restrained expansion, a more systematic quantification of leaching effects, long-term correlation between laboratory and field behavior, and the cross-validation of DRI/SDT–expansion relationships as a robust bridge between diagnosis and prognosis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.S.M., F.A.N.S. and E.A.R.; investigation, M.E.S.M., F.A.N.S. and E.A.R.; formal analysis, M.E.S.M., F.A.N.S., E.A.R., A.C.A. and J.M.P.Q.D.; validation, M.E.S.M., F.A.N.S., E.A.R., A.C.A. and J.M.P.Q.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.S.M., F.A.N.S., E.A.R., A.C.A. and J.M.P.Q.D.; writing—review and editing, M.E.S.M., F.A.N.S., E.A.R., A.C.A. and J.M.P.Q.D.; supervision, F.A.N.S.; funding acquisition, J.M.P.Q.D. and F.A.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Base Funding—UIDB/04708/2020, with DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/04708/2020; Programmatic Funding—UIDP/04708/2020, with DOI: 10.54499/UIDP/04708/2020 of the CONSTRUCT funded by national funds through the FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC); and FCT through the individual Scientific Employment Stimulus 2020.00828.CEECIND/CP1590/CT0004, DOI: 10.54499/2020.00828.CEECIND/CP1590/CT0004.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bergmann, A.; Sanchez, L.F.M. Assessing the reliability of laboratory test procedures for predicting concrete field performance against alkali-aggregate reaction (AAR). Cement 2025, 19, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khair, S.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. Mitigating heavy metal leaching and ASR expansion in copper heap leach residue concrete using cement and cement-fly ash-silica fume blends: Experimental and microstructural insights. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 497, 143859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grazia, M.T.; Goshayeshi, N.; Gorga, R.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Santos, A.C.; Souza, D.J. Comprehensive semi-empirical approach to describe alkali aggregate reaction (AAR) induced expansion in the laboratory. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 40, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoine, A.; Brunetaud, X.; Divet, L. The impact of cement parameters on Delayed Ettringite Formation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Souza, D.J.; Zubaida, N.; Sanchez, L.F.M. Overall assessment of CFRP-wrapped concrete affected by alkali-silica reaction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 169, 107165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.F.M.; Fournier, B.; Jolin, M.; Duchesne, J. Reliable quantification of AAR damage through assessment of the Damage Rating Index (DRI). Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, M.; Moodi, F.; Ramezanianpour, A.M.; Zolfagharnasab, A.; Ramezanianpour, A.A. Assessing the risk of ASR in LC3 binders based on low-grade calcined clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéruel, A.; Ben Ftima, M. Unrestrained ASR volumetric expansion for mass concrete structures: Review and experimental investigation using 3D laser scanning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 399, 132565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leśnicki, K.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kurtis, K.E.; Jacobs, L.J. Characterization of ASR damage in concrete using nonlinear impact resonance acoustic spectroscopy technique. NDT E Int. 2011, 44, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.P.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Fournier, B.; Toutlemonde, F. Evaluation of different techniques for the diagnosis & prognosis of Internal Swelling Reaction (ISR) mechanisms in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, E.R.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Tuinukuafe, A.; Folliard, K.J. Characterization of concrete affected by delayed ettringite formation using the stiffness damage test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 162, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouvrier-Buffet, F.; Eiras, J.N.; Garnier, V.; Payan, C.; Ranaivomanana, N.; Durville, B.; Marquie, C. Linear and nonlinear resonant ultrasonic techniques applied to assess delayed ettringite formation on concrete samples. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 275, 121545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.F.M.; Drimalas, T.; Fournier, B.; Mitchell, D.; Bastien, J. Comprehensive damage assessment in concrete affected by different internal swelling reaction (ISR) mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 107, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Leklou, N.; Mounanga, P. Development of accelerated test methods by electromigration to assess the risk of internal sulfate attack in heat-cured mortar and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 455, 139185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, J.; Ribeiro, A.B. Evaluation of damage in concrete from structures affected by internal swelling reactions—A case study. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 17, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portella, K.F.; Hasparyk, N.P.; Bragança, M.D.G.P.; Bronholo, J.L.; Dias, B.G.; Lagoeiro, L.E. Multiple techniques of microstructural characterization of DEF: Case of study with high early strength Portland cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 311, 125341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Gowripalan, N.; Sirivivatnanon, V.; South, W. Accelerated test for assessing the potential risk of alkali-silica reaction in concrete using an autoclave. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D.J.; Antunes, L.R.; Sanchez, L.F.M. The evaluation of Wood Ash as a potential preventive measure against alkali-silica reaction induced expansion and deterioration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Li, J.; Fournier, B.; Sirivivatnanon, V. Correlating alkali-silica reaction (ASR) induced expansion from short-term laboratory testings to long-term field performance: A semi-empirical model. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Rajabipour, F.; Olek, J.; Peethamparan, S. Characterizing the mechanisms and alkali-silica reaction behavior of novel and non-traditional alkali-activated materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 195, 107914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Pierre, F.; Rivard, P.; Ballivy, G. Measurement of alkali–silica reaction progression by ultrasonic waves attenuation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, L.F.M.; Fournier, B.; Jolin, M.; Bastien, J. Evaluation of the stiffness damage test (SDT) as a tool for assessing damage in concrete due to ASR: Test loading and output responses for concretes incorporating fine or coarse reactive aggregates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 56, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Noël, M. Appraisal of visual inspection techniques to understand and describe ASR-induced development under distinct confinement conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, J.; Darquennes, A.; Divet, L.; Bennacer, R.; Torrenti, J.M.; Nahas, G. New experimental approach to accelerate the development of internal swelling reactions (ISR) in massive concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 313, 125388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, P.; Saint-Pierre, F. Assessing alkali-silica reaction damage to concrete with non-destructive methods: From the lab to the field. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, A.; Bilodeau, S.; Pissot, F.; Fournier, B.; Bastien, J.; Bissonnette, B. Expansive behavior of thick concrete slabs affected by alkali-silica reaction (ASR). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Dunant, C.; Yamada, K.; Scrivener, K. Impact of temperature on expansive behavior of concrete with a highly reactive andesite due to the alkali–silica reaction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 125, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotero Software, version 6.0. Corporation for Digital Scholarship. 2024. Available online: https://www.zotero.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ASTM C1293; Determination of Length Change of Concrete Due to Alkali-Silica Reaction. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020.

- CSA A23.2-14A; Alkali-Aggregate Reaction (Concrete Prism Test). Methods of Test for Concrete, CAN3-A23.2-M77. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1977; pp. 183–185.

- RILEM AAR-3; Detection of Potential Alkali-Reactivity—38 °C. Test Method for Aggregate Combinations Using Concrete Prisms. RILEM: Paris, France, 2016.

- ANFOR NF P18-594; Aggregates—Test Methods of Reactivity to Alkalis. French Association for Standardization: Paris, France, 2015.

- Piersanti, M.; Shehata, M.H. A study into the alkali-silica reactivity of recycled concrete aggregates and the role of the extent of damage in the source structures: Evaluation, accelerated testing, and preventive measures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 129, 104512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, P.; Ballivy, G. Assessment of the expansion related to alkali-silica reaction by the Damage Rating Index method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2005, 19, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopperla, K.S.T.; Drimalas, T.; Beyene, M.; Tanesi, J.; Folliard, K.; Ardani, A.; Ideker, J.H. Combining reliable performance testing and binder properties to determine preventive measures for alkali-silica reaction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 151, 106641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, C.; Vidal, T.; Sellier, A.; Noret, C.; Anthiniac, P. Creep of concrete during Alkali-Aggregates Reaction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 336, 127355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillott, J.E.; Rogers, C.A. The behavior of silicocarbonatite aggregates from the Montreal area. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Trottier, C.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Noël, M. Evaluation of the induced mechanical deterioration of alkali-silica reaction affected concrete under distinct confinement conditions through the Stiffness Damage Test. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 126, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berra, M.; Faggiani, G.; Mangialardi, T.; Paolini, A.E. Influence of stress restraint on the expansive behaviour of concrete affected by alkali-silica reaction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, S.H.; Soliman, A.M.; Nokken, M.R. Feasibility of basalt and glass FRP mesh for strengthening and confinement concrete damage due to ASR-expansion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 120893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubat, T.; Al-Mahaidi, R.; Shayan, A. Strain development in CFRP-wrapped circular concrete columns affected by alkali-aggregate reaction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 113, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, S.H.; Soliman, A.M.; Nokken, M. Exterior strengthening for ASR damaged concrete: A comparative study of carbon and basalt FRP. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.; Carles-Gibergues, A. Normalized age applied to AAR occurring in concretes with or without mineral admixtures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozière, E.; Loukili, A.; El Hachem, R.; Grondin, F. Durability of concrete exposed to leaching and external sulphate attacks. Cem. Concr. Res. 2009, 39, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diaz, E.; Bulteel, D.; Monnin, Y.; Degrugilliers, P.; Fasseu, P. ASR pessimum behaviour of siliceous limestone aggregates. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektas, F.; Wang, K. Performance of ground clay brick in ASR-affected concrete: Effects on expansion, mechanical properties and ASR gel chemistry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgård, J.; Thomas, M.D.A.; Sellevold, E.J.; Pedersen, B.; Andiç-Çakır, O.; Justnes, H.; Rønning, T.F. Alkali–silica reaction (ASR)—Performance testing: Influence of specimen pre-treatment, exposure conditions and prism size on alkali leaching and prism expansion. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 53, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jen, G.; Hay, R.; Ostertag, C.P. Multi-scale evaluation of hybrid fiber restraint of alkali-silica reaction expansion in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, A.; Grimstad, J. Deterioration of concrete in a hydroelectric concrete gravity dam and its characterisation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, T. The so-called alkali-carbonate reaction (ACR)—Its mineralogical and geochemical details, with special reference to ASR. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 643–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, R.D.; Jayapalan, A.M.; Garas, V.Y.; Kurtis, K.E. Assessment of binary and ternary blends of metakaolin and Class C fly ash for alkali-silica reaction mitigation in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.H.; Christidis, C.; Mikhaiel, W.; Rogers, C.; Lachemi, M. Reactivity of reclaimed concrete aggregate produced from concrete affected by alkali–silica reaction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Zheng, L.; Xu, X. Evaluation of alkali reactivity of concrete aggregates via AC impedance spectroscopy. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 145, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.B.; Brito, J.; Silva, A.S.; Ahmed, H.H. Study of ASR in concrete with recycled aggregates: Influence of aggregate reactivity potential and cement type. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 265, 120743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, S.H.; Soliman, A.M.; Nokken, M.R. Effect of triggering material, size, and casting direction on ASR expansion of cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanijo, E.O.; Kassem, E.; Ibrahim, A. ASR mitigation using binary and ternary blends with waste glass powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, H.; Heidarpour, A.; Shayan, A. Experimental and analytical studies of bacterial self-healing concrete subjected to alkali-silica-reaction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 310, 125149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolik, A.; Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D. ASR induced by chloride- and formate-based deicers in concrete with non-reactive aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabari, M.; Al-Rashed, R.; Ayers, M.E. Mitigation of alkali silica reactions in concrete using multi-crystalline intermixed waterproofing materials. Cement 2023, 12, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargolzahi, M.; Kodjo, S.A.; Rivard, P.; Rhazi, J. Effectiveness of nondestructive testing for the evaluation of alkali–silica reaction in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, B.P.; Panesar, D.K. The effect of elevated conditioning temperature on the ASR expansion, cracking and properties reactive Spratt aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasvand, E.; Mohammadi, H.; Rezaei, Z.; Ayyoubi, M.; Dehghani, S. Evaluation of the durability of concretes containing alkali-activated slag exposed to the alkali-silica reaction by measuring electrical resistivity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D.J.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Biparva, A. Influence of engineered self-healing systems on ASR damage development in concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 147, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, O.D.; Nokken, M.R.; Sanchez, L.F.M. Evaluation of the induced mechanical deterioration of ASR-affected concrete under varied moisture and temperature conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 157, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaudat, J.; Carol, I.; López, C.M.; Saouma, V.E. ASR expansions in concrete under triaxial confinement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 86, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macioski, G.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; Medeiros, M.H.F. Multiscale monitoring of alkali–silica reaction in concrete with embedded fiber Bragg grating sensors. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 495, 143718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinicki, M.A.; Jóźwiak-Niedźwiedzka, D.; Antolik, A.; Dziedzic, K.; Dąbrowski, M.; Bogusz, K. Diagnosis of ASR damage in highway pavement after 15 years of service in wet-freeze climate region. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D.J.; Sanchez, L.F.M. Evaluating the efficiency of SCMs to avoid or mitigate ASR-induced expansion and deterioration through a multi-level assessment. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 173, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D.J.; Sanchez, L.F.M.; De Grazia, M.T. Evaluation of a direct shear test setup to quantify AAR-induced expansion and damage in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 16806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, A.; Watanabe, M.; Murakami, R.; Ohkubo, T. Visualization of internal crack growth due to alkali–silica reaction using digital image correlation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemann, A.; Münch, B.; Lothenbach, B.; Bernard, E.; Trottier, C.; Winnefeld, F.; Sanchez, L. Alkali-carbonate reaction in concrete—Microstructural consequences and mechanism of expansion. Cem. Concr. Res. 2025, 195, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivard, P.; Ollivier, J.P.; Ballivy, G. Characterization of the ASR rim Application to the Potsdam sandstone. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukari, Y.; Bulteel, D.; Rivard, P.; Abriak, N.E. Combining nonlinear acoustics and physico-chemical analysis of aggregates to improve alkali–silica reaction monitoring. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 67, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RILEM AAR-2; Detection of Potential Alkali-Reactivity—Accelerated Mortar-Bar Test Method for Aggregates. RILEM: Paris, France, 2015.

- ASTM C1260; Standard Test Method for Potential Alkali Reactivity of Aggregates (Mortar-Bar Method). ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023.

- Nagrockienė, D.; Rutkauskas, A. The effect of fly ash additive on the resistance of concrete to alkali silica reaction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 201, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, J.; Lindgård, J.; Fournier, B.; Silva, A.S.; Thomas, M.D.; Drimalas, T.; Ideker, J.H.; Martin, R.-P.; Borchers, I.; Wigum, B.J.; et al. Correlating field and laboratory investigations for preventing ASR in concrete—The LNEC cube study (Part I—Project plan and laboratory results). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 343, 128131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RILEM AAR-4.1; Detection of Potential Alkali-Reactivity—60 °C Test Method for Aggregate Combinations Using Concrete Prisms. RILEM: Paris, France, 2015.

- RILEM AAR-12; Determination of Binder Combinations for Non-Reactive Mix Design or the Resistance to Alkali-Silica Reaction of Concrete Mixes Using Concrete Prisms —60 °C Test Method with Alkali Supply. RILEM: Paris, France, 2021.

- BS 812-123; Method for Determination of Alkali-Silica Reactivity-Concrete Prism Method. BSI: London, UK, 1999.

- Taha, B.; Nounu, G. Using lithium nitrate and pozzolanic glass powder in concrete as ASR suppressors. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LPC No. 44; Alcali-Réaction du Béton—Essai D’expansion Résiduelle sur Béton Durci. MELPC, ME 44. Laboratoire Central des Ponts et Chaussées: Paris, France, 1997.

- LPC No. 67; Réaction Sulfatique Interne au béton—Essai D’expansion Résiduelle sur Carotte de Béton Extraite de L’ouvrage. MELPC, ME 67. Laboratoire Central des Ponts et Chaussées: Paris, France, 2006.

- JIS A6202; Expansive Additive for Concrete. Japanese Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 2017.

- Wyrzykowski, M.; Terrasi, G.; Lura, P. Expansive high-performance concrete for chemical-prestress applications. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 107, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBR 15577-6; Aggregates—Alkali-Aggregate Reactivity. ABNT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2018.

- NB32; Alkali–Aggregate Reactions in Concrete. Test Methods Requirem. Test Laborat. Norwegian Concrete Association: Oslo, Norway, 2005.

- AASHTO T380; Standard Method of Test for Potential Alkali Reactivity of Aggregates and Effectiveness of ASR Mitigation Measures (Miniature Concrete Prism Test, MCPT). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.