Abstract

The use of flawed excavated-mass aggregates produced from crushing and screening hydraulic engineering waste in concrete projects can reduce natural resource extraction, increase waste utilization rates, and minimize environmental pollution. However, the direct application of flawed excavated-mass aggregates is limited due to their high crushing index and water absorption rate. Therefore, this paper measures the multi-dimensional physical and mechanical properties of defective aggregates. A strengthening slurry is prepared by comprehensively modifying the crystallization strength and penetration path of sodium silicate solution using various chemical reagents. The strengthening mechanism of the slurry on flawed excavated-mass aggregates is analyzed using SEM and MIP tests. Concrete tests are designed to investigate the workability and mechanical properties of flawed excavated-mass aggregate concrete. The pore structure of the ITZ (Interfacial Transition Zone) in defective aggregate concrete is analyzed through BSE (Backscattered Electron) imaging to elucidate the strengthening mechanism of secondary crystallization reactions on the ITZ. The research findings can provide technical support for repairing aggregates with defects.

1. Introduction

Large quantities of flawed excavated material are generated during the construction of hydraulic engineering projects such as water conservancy hubs and water diversion tunnels. This material is often discarded in mountain gullies, valleys, or spoil grounds, leading to waste, vegetation damage, and environmental pollution. Repairing and reinforcing this flawed excavated material for use as aggregates would not only protect the environment but also address the current imbalance in aggregate supply and demand and reduce engineering construction costs [1,2,3].

In recent years, scholars worldwide have conducted extensive research on the rational utilization of engineering excavation materials. Mostafaei et al. [4] found that solid waste-based binder CGF exhibits superior moisture resistance compared to ordinary cement, which demonstrates better low-temperature performance. Deng et al. [5] validated the feasibility of using tunnel spoil in cement-stabilized base courses, with its unconfined compressive strength significantly increasing from 7.0 MPa to 11.0 MPa within 90 days. Wu et al. [6] proposed using coarse gravel from tunnel excavation as anti-frost fill material, and field monitoring demonstrated that a 2 m-thick fill layer could reduce frost heave by over 70%. Xie et al. [7] established a constitutive relationship between particle breakage and accumulated strain of crushed rock slag through triaxial tests. Nuray Tokgöz et al. [8,9] explored the feasibility of using TBM excavation materials as rock fill for reservoirs. Current research primarily focuses on high-quality aggregates, such as granite and limestone, while the application of low-strength porous materials, such as dolomite, remains limited, highlighting the importance of developing reinforcement technologies. Microbial mineralization deposition technology leverages the calcium carbonate deposition capabilities of certain mineralizing organisms in nature to selectively fill or bind porous media with permeability, thereby improving the pore structure of materials. Grabiec M A et al. [10] proposed using biogenic calcium carbonate deposition to strengthen recycled aggregates, discovering that this method could increase the water absorption of recycled aggregates and was more effective for finer and lower-quality aggregates. Qiu et al. [11] used microbial carbonate precipitation to treat recycled aggregates and found that it could increase the weight and decrease the water absorption of the aggregates. The sedimentation rate, quantity, and type of microbial carbonate precipitation can be altered by adjusting water conditions. Liu et al. [12] employed Bacillus cohnii to modify recycled aggregates, achieving concrete performance with a 40% replacement ratio comparable to natural aggregates. In chemical modification, Sasanipour et al. [13] found that 25% coarse recycled aggregates had no significant impact on the durability of self-compacting concrete. Belabbas et al. [14] and Zhang et al. [15] revealed the shrinkage patterns of multi-generation recycled aggregates. significantly reduced water absorption by filling pores with silicon-based polymers. In fiber reinforcement, Yuan et al. [16] achieved an optimal compressive strength of recycled brick-concrete aggregate concrete using basalt fibers. Zhang et al. [17] identified an 8% sodium silicate solution with 5 h immersion as the optimal strengthening method for recycled coarse aggregates, demonstrating that the treated aggregates meet heavy-traffic base course requirements at 5% cement content. Zhuang et al. [18] developed a cold-bonding and microbial mineralization technique to form dense crystalline layers, enhancing overall performance. Kou et al. [19] used different concentrations of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution to impregnate and strengthen recycled aggregates. The results showed that the water absorption of the PVA-treated recycled aggregates was significantly reduced, and the durability and drying shrinkage performance of the concrete were improved, with no significant change in the compressive strength of the concrete.

Nano-crystallization is a method used to improve the porosity of aged mortar and the strength of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) in recycled aggregates by utilizing the secondary hydration reaction and filling effect of nanomaterials such as sodium silicate. Xue et al. [20] used nano-SiO2 soaking to strengthen recycled aggregates. The experiment showed that nano-silica reinforcement reduced aggregate water absorption and increased the compressive strength of concrete. Microscopic analysis and pore analysis revealed that the filling effect and secondary hydration reaction of nano-silica improved the performance of recycled aggregates. Li et al. [21] addressed the reduced mortar fluidity caused by high water absorption of recycled concrete aggregates by evaluating conventional pre-saturation and extra water addition methods. The team developed an innovative mix proportion design based on real-time absorption measurement in cement paste, revealing distinct absorption behavior compared to pure water: stabilization within 24 min, 80% completion within 6 min, and a maximum absorption lower than the 24 h standard. The study also established that water absorption increases with water–cement ratio but decreases with higher aggregate volume fraction. Shi, C. et al. and Ge, P. et al. [22,23] showed that recycled concrete immersed in 5% sodium silicate exhibited the best compressive strength. But the compressive strength of concrete immersed in 5~7% sodium silicate was not high. Based on the above research, the filling effect of nanomaterials such as sodium silicate can enhance the strength and structural compactness of recycled aggregate mortar, thereby improving the mechanical properties and durability of recycled aggregate concrete. However, due to their extremely small particle size, nanomaterials are prone to agglomeration during the strengthening process, reducing their effectiveness. Further research is needed to develop new nanomaterials suitable for aggregate reinforcement.

Newly prepared sodium silicate undergoes an “aging” phenomenon during storage, where silicic acid spontaneously polymerizes, leading to decreased viscosity and bonding strength along with increased surface tension [24,25]. To address this, two main modification methods—physical and chemical—are employed. Physical modification utilizes external energy fields such as ultrasound, magnetic fields, or pulsed electric currents. For instance, Wang, L. Reference [26] applied ultrasonic treatment to enhance performance. While Wang et al. [27] demonstrated that electrochemical modification promotes sodium silicate hydrolysis, increasing H+ and inhibitory components (H2SiO3/SiO32−/HSiO3−) and thereby improving its inhibitory effect on muscovite. Chemical modification involves adding organic or inorganic substances with polar groups to suppress silicic acid polycondensation. Xu et al. [28] reported a strength saturation phenomenon in sodium silicate-solidified sandy soil, where specimens with low Baume degree exhibit strength saturation values below 3 MPa, while those with high Baume degree exceed 8 MPa. Phuong [29] and Lim [30] enhanced bonding strength and high-temperature fluidity by incorporating disodium hydrogen phosphate to form a multi-layer network structure. Song et al. [31] confirmed that silica fumes significantly improve the mechanical properties and humidity resistance of sodium silicate-based inorganic sand cores by promoting silicate polymerization. In summary, chemical modification is more suitable for large-scale engineering applications due to its lower equipment requirements. To improve the utilization rate of excavated materials, this study investigates the physical and mechanical properties of flawed excavated-mass aggregates and systematically evaluates their performance. Sodium silicate is used for modification from the perspectives of crystal strength and permeation pathways to prepare a strengthening grout for reinforcing defective aggregates. The effectiveness and strengthening mechanism of the grout are then explored. Furthermore, concrete is prepared using the strengthened, flawed excavated-mass aggregates to investigate the changes in workability and mechanical properties. The improvement in concrete performance using the secondary crystallization process is elucidated through analysis of the ITZ pore structure. The research results can provide a basis for the reinforcement of excavated materials with defects.

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

This study used 42.5 grade ordinary Portland cement to prepare C30 concrete. The concrete mix ratio design is shown in Table 1. The mix proportion design is as follows: water-binder ratio 0.58, sand ratio 36%, cement dosage 362 kg/m3, water dosage 210 kg/m3, and sand dosage 676 kg/m3.

Table 1.

Concrete mix design.

The fine aggregate was natural river sand. For the “N” group, the coarse aggregate consisted of 100% natural granite (5–20 mm). For all other groups (B, B3, B9, B15), the coarse aggregate was entirely replaced with flawed excavated-mass dolomite (5–20 mm), obtained from the Chongqing BaiMa Navigation and Hydropower Hub Project, and processed using a jaw crusher and screening. The “B3” group used flawed excavated-mass aggregates that had been soaked in a 3% concentration of strengthening slurry and air-dried. The raw modifier materials are shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, the strengthening slurry was made by compounding and modifying water, sodium silicate, sodium borate, sodium hexametaphosphate, and polycarboxylate substances in a mass ratio of 100:15:2:1.5:0.6.

Figure 1.

Sodium silicate modified materials: (a) sodium silicate; (b) sodium borate; (c) sodium hexametaphosphate.

2.2. Experimental Process

2.2.1. Preparation of Strengthened Aggregates

Weigh different proportions of sodium borate (0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%), sodium hexametaphosphate (0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%), and polycarboxylic acid (0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%), dissolve them in water, and stir for 10 min until completely dissolved. Then add sodium silicate at the specified concentrations (3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 15%) and continue to stir for 20 min until fully dissolved. The soaking and air-drying procedures are illustrated in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, pour the resulting slurry into a container with flawed excavated-mass aggregates, with the liquid surface 20 mm higher than the aggregates. After soaking for 14 days, remove the aggregates, spread them out, and air-dry for 14 days. Then rinse the surface of soluble crystals and air-dry them for use in testing the crushing index and water absorption rate. For the SEM test, select flawed excavated-mass aggregates (BA, i.e., baseline flawed excavated-mass aggregates) and reinforced aggregates (BA15) treated with 15% reinforcing slurry, and prepare them into specimens smaller than 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm. Dry them at 60 °C for 2 days and then spray gold for testing. For the MIP test, use flawed excavated-mass aggregates (NA, i.e., natural aggregate) and reinforced aggregates (BA3, BA9, BA15) treated with 3%, 9%, and 15% reinforcing slurry. The sample treatment method is the same as that for SEM, but no gold spraying is required.

Figure 2.

The process of reinforcing with flawed excavated-mass aggregates: (a) soaking process; (b) air dry process.

2.2.2. Preparation of Concrete Specimens

This experiment mainly involved conducting tests on concrete slump, backscatter electron (BSE), and compressive strength. Before pouring, the reinforcing slurry was diluted to five concentrations: 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, and 15%. The flawed excavated-mass aggregates were, respectively, soaked and air-dried with these concentrations, and a group of flawed excavated-mass aggregates soaked in clean water was set as the control group. The cubic compressive strength test specimens measured 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm. The BSE specimens were taken from concrete that had been standardly cured for 28 days, cut into 10 mm cubic samples, and then underwent the following treatments: soaked in isopropyl alcohol for 72 h, dried at 60 °C for 3 days, impregnated with low-viscosity epoxy resin, and cured at room temperature for 48 h. Subsequently, the specimens were polished with 500–5000 mesh sandpaper, and then the surface powder and residues were cleaned with isopropyl alcohol for observation. The specific test items, specimen sizes, and quantities are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample design for microscopic analysis of aggregate and performance of concrete.

2.2.3. Test Set-Up

The aggregate crushing value and water absorption of natural and flawed aggregates were tested following the Chinese standard GB/T 14685-2022. Concrete performance was evaluated by testing the slump in accordance with GB/T 50080-2016 and the cube compressive strength as per GB/T 50081-2019.

Microstructural characterization was conducted using several techniques. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed using an FEI Quanta FEG250 microscope at an accelerating voltage of 8 kV and magnifications of 1000×, 5000×, and 10,000×. Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) measurements were performed using a McMurtry AutoPore V 9600 instrument, capable of measuring pore sizes from 3 nm to 500 μm. Back-Scattered Electron (BSE) imaging was implemented on a TESCAN MIRA4 microscope operating at 15 keV, with a working distance of 15.52 mm and a magnification of 500×. For BSE analysis, ten images were captured per sample with a pixel size of 0.545 μm. Impact crusher and compression testing equipment are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(a) Impact crusher; (b) compression test equipment.

3. Mechanism of Defect Aggregate Performance Enhancement Based on Crystalline Products

3.1. Influence of Crystal Strength on the Performance of Flawed Excavated-Mass Aggregates

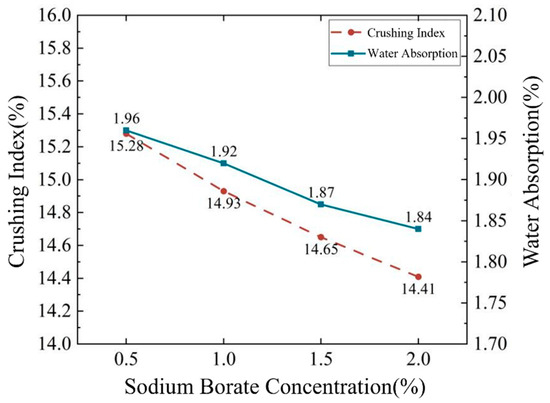

The crushing value and water absorption rate of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates after being reinforced with sodium borate solution are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Effect of sodium borate concentration on crushing index and water absorption of defective aggregates.

Figure 4 indicates that the crushing value and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates decrease continuously with increasing sodium borate concentration. When the sodium borate concentration is 2.0%, the crushing value and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates are minimized, suggesting that the optimal dosage of sodium borate is 2.0%. The key to boron’s strengthening effect in the alkali-silica system lies in the incorporation of Boron(B) into the sodium silicate network in a tetrahedral coordination structure. To ensure that all B in the Na2O-B2O3-SiO2 system enters the robust tetrahedral network and enhances the strength of the silica crystals (i.e., preventing the formation of [BO3] low-coordination structures), the limit for B content in this system is: B2O3 = 12%, SiO2 = 79–80% [32]. In this experiment, the maximum dosage of sodium borate is 2.0%, which is far below the aforementioned limit. Therefore, the incorporated sodium borate forms a robust composite network with [SiO4] in a tetrahedral coordination structure within the alkali–silica system, making the single silica crystal structure more complete [33]. This enhances the strength and density of the silica crystals, thereby improving the mechanical properties of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates and reducing their crushing index and water absorption.

As shown in Figure 5, the crushing index of flawed excavated-mass aggregate decreases continuously with increasing sodium hexametaphosphate concentration, while the water absorption rate increases slightly. The crushing index of defective aggregate reaches its minimum and optimal value at a sodium hexametaphosphate concentration of 1.5%. This is because sodium hexametaphosphate is continuously hydrolyzed under the catalysis of sodium silicate to generate phosphate. The phosphate tetrahedron [PO4] inserts into the molecular chain composed of silicon-oxygen tetrahedra [SiO4] to form a silicon-phosphorus-oxygen molecular chain. After sodium polyphosphate dissolves into sodium silicate, it changes the structure of the polysilicate chain, which improves the bonding strength of sodium silicate to a certain extent, thereby enhancing the strength of the [SiO4] single network crystal and reducing the crushing index of the flawed excavated-mass aggregate [30]. In a humid environment, sodium hexametaphosphate reacts with water to generate pentasodium, containing six crystal water molecules. The generated hexahydrate pentasodium is a cubic prismatic crystal, which destroys the integrity of the network structure of sodium silicate, thereby enhancing the water absorption capacity of sodium silicate [34].

Figure 5.

Effect of sodium hexametaphosphate concentration on crushing index and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates.

3.2. Impact of Permeation Paths on the Performance of Flawed Excavated-Mass Aggregates

Polycarboxylate superplasticizers are common anionic surfactants in concrete laboratories, frequently used during concrete mixing to enhance workability. The addition of surfactants serves a dual purpose: firstly, they disperse the sodium silicate colloidal solution system, improving its stability; secondly, they lower the surface tension of the sodium silicate, enhancing its wetting ability on flawed excavated-mass aggregates. This extends the penetration pathways of the sodium silicate, enabling it to seep into the fine fissures deep within the aggregates, thereby strengthening the performance of these compromised materials. Figure 6 shows the influence of polycarboxylic acid concentration on the crushing index and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates. As shown in the figure, the crushing index of flawed excavated-mass aggregates initially decreases with increasing polycarboxylic acid concentration, then remains essentially constant. The crushing index of flawed excavated-mass aggregates is minimized at 14.38% when the polycarboxylic acid concentration is 0.6%. The water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates initially decreases with increasing polycarboxylic acid concentration, followed by a slight increase. The water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates is minimized at 1.81% when the polycarboxylic acid concentration is 0.8%. Therefore, the optimal dosage of polycarboxylic acid is 0.6%.

Figure 6.

Influence of polycarboxylic acid concentration on crushing index and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates.

The addition of polycarboxylate substances to a sodium silicate system results in the hydrophobic groups preferentially adsorbing onto the polysilicic acid chain surfaces, while the hydrophilic groups orient themselves towards the aqueous solution. This imparts a uniform charge to the polysilicic acid chain surfaces, altering their structure. The resulting electrostatic repulsion between like charges causes the polysilicic acid chains to move further apart. This weakens the polycondensation reaction between the silicic acid chains, leading to a significant dispersion effect and improved stability of the sodium silicate system. Simultaneously, the electrostatic repulsion from the uniform charges facilitates the breakdown of polysilicic acid chains into smaller structures, reducing the surface tension of the sodium silicate. This enhances the wettability of sodium silicate on flawed excavated-mass aggregates, enabling it to penetrate deeper into the flawed excavated-mass aggregates through nanoscale cracks, thereby expanding the penetration pathways of the sodium silicate.

3.3. Impact of Crystal Content on the Flawed Excavated-Mass Aggregates

Because sodium borate, sodium hexametaphosphate, and polycarboxylate materials modify sodium silicate through different mechanisms, the resulting modified flawed excavated-mass aggregates exhibit individual strengths and weaknesses in their physical and mechanical properties. Therefore, this study investigates the individual modification effects of each substance on sodium silicate. Furthermore, sodium borate, sodium hexametaphosphate, and polycarboxylate are used in combination to modify sodium silicate solutions in order to prepare a strengthened grout. This aims to comprehensively improve the penetration performance of sodium silicate and the strength of the silicon dioxide crystals. The quality ratio of the enhanced grout material is 100:15:2:1.5:0.6. Prepare solutions of strengthening slurry at concentrations of 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, and 15% to impregnate and air-dry flawed excavated-mass aggregates. Simultaneously, the flawed excavated-mass aggregates soaked in water were used as a control group.

As shown in Figure 7, the crushing index of flawed excavated-mass aggregates continuously decreases with the increase in reinforcement slurry concentration, with reductions of 5.09%, 3.46%, 2.09%, 1.34%, and 0.68% for each level, respectively. The water absorption rate of flawed excavated-mass aggregates also exhibits a similar trend to the crushing index, decreasing continuously with increasing reinforcement slurry concentration, with reductions of 0.34%, 0.23%, 0.18%, 0.09%, and 0.07% for each level, respectively. It can be observed that the reductions in both the crushing index and water absorption rate decrease at each level as the reinforcement slurry concentration increases. However, when the slurry concentration exceeds 9%, the improvement effect of the reinforcement slurry on the physical and mechanical properties of flawed excavated-mass aggregates gradually weakens.

Figure 7.

Influence of slurry concentration on crushing index and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates.

3.4. Mechanism of Performance Enhancement for Flawed Excavated-Mass Aggregates Based on Crystalline Products

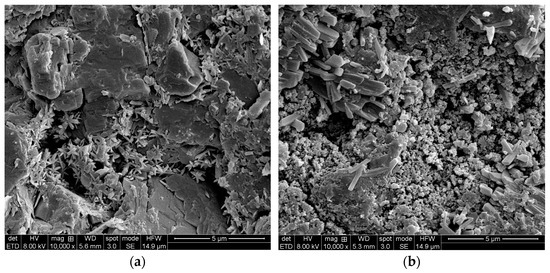

Figure 8 shows the scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates after repair. As shown in Figure 8, the surface of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates is generally uneven, with numerous micropores and fissures. Some diagenetic crystals of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates are short, randomly arranged, and have a loose structure, surrounded by a large number of pores and cracks. The surface smoothness of the reinforced aggregate is significantly improved, with no obvious pores or fissures. Obvious columnar and rod-shaped silicon oxide crystals are densely arranged on the surface, with a dense accumulation of silicon oxide crystals near the pores. It can be seen that the silicon oxide crystals effectively fill the pores and voids of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates, optimize the pore structure of the aggregate, and improve the physical and mechanical properties of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates.

Figure 8.

Scanning electron microscope image of aggregate: (a) flawed excavated-mass aggregate; (b) reinforced aggregate.

Figure 9 shows the pore size distribution of the aggregate before and after reinforcement. The figure indicates that soaking with the reinforcing slurry can densify the pore structure of flawed excavated-mass aggregates and reduce their total porosity, and the higher the concentration of the reinforcing slurry, the lower the total porosity. The total porosities are 4.92% for BA3, 4.70% for BA9, and 3.66% for BA15, representing reductions of 1.28%, 1.50%, and 2.54%, respectively, compared with BA. After soaking in the reinforcing slurry, the cumulative mercury intrusion volume per unit mass of flawed excavated-mass aggregates decreases, indicating a reduction in aggregate porosity. During the soaking process, the slurry penetrates weak locations such as cracks and pores of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates; during air drying, the sodium silicate in the slurry dehydrates and solidifies into silica crystals, filling the aggregate and reducing internal pore and void volume, thereby densifying the aggregate.

Figure 9.

Total porosity of aggregate.

Figure 10 shows the pore size distribution curves of the aggregates. The figure indicates that after soaking in the reinforcing slurry, the pore size distribution curve of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates shifts markedly toward smaller pores, and the volume of the large-pore portion decreases sharply. The mean pore diameters are 355.87 nm for BA, 132.06 nm for BA3, 112.54 nm for BA9, and 52.64 nm for BA15, representing reductions of 223.81 nm, 243.33 nm, and 269.63 nm compared with BA, respectively; the mean pore size has clearly decreased.

Figure 10.

Aggregate pore size distribution curve of different groups.

4. Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Concrete Reinforced with Flawed Excavated-Mass Aggregate

4.1. Concrete Slump

Reinforced aggregate concrete prepared by soaking aggregates in 3%, 9%, and 15% strengthening slurry (designated B3, B9, and B15, respectively) exhibited slump values of 150 mm, 155 mm, and 160 mm (Figure 11). This represents an increase of 10 mm, 15 mm, and 20 mm, respectively, compared to concrete made with flawed excavated-mass aggregates. This improvement is attributed to the reduced water absorption of the reinforced aggregates, leading to less water being absorbed during concrete mixing. Consequently, the effective water-to-cement ratio of the concrete is partially restored, resulting in increased slump. However, the slump of the reinforced aggregate concrete remained lower than that of concrete made with natural aggregates. This is partly because flawed excavated-mass aggregates tend to fracture along internal natural fissures and joints during crushing, resulting in a higher proportion of angular aggregates. Compared to rounded natural aggregates, angular aggregates make concrete less workable. Additionally, the water absorption rate of flawed excavated-mass aggregates is 2.65%, which is 2.22% higher than that of natural aggregates. During concrete mixing, flawed excavated-mass aggregates absorb more mixing water, reducing the effective water-cement ratio and consequently decreasing the concrete’s fluidity.

Figure 11.

Concrete slump of different groups.

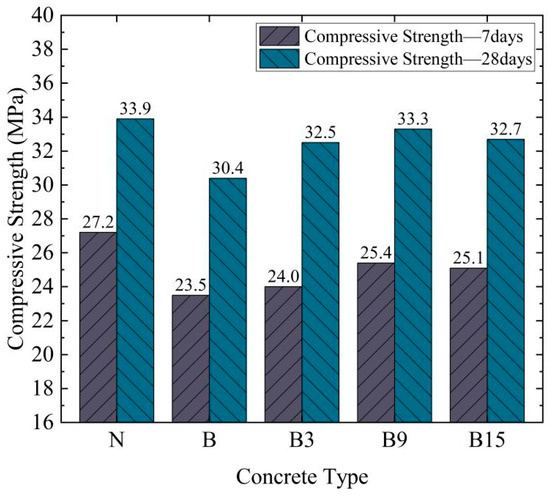

4.2. Concrete Compressive Strength

As shown in Figure 12, natural aggregate concrete exhibits a compressive strength of 27.2 MPa at 7 days and 33.9 MPa at 28 days. Flawed excavated-mass aggregate concrete shows compressive strengths of 23.5 MPa at 7 days and 30.4 MPa at 28 days, which are 3.7 MPa and 3.5 MPa lower than those of natural aggregate concrete at 7 and 28 days, respectively. The 28-day compressive strength of B9 (33.3 MPa) is comparable to that of natural aggregate concrete (33.9 MPa). The 7-day compressive strengths of B3, B9, and B15 are 24.0 MPa, 25.4 MPa, and 25.1 MPa, representing increases of 0.5 MPa, 1.9 MPa, and 1.6 MPa compared to the 7-day compressive strength of flawed excavated-mass aggregate concrete. The 28-day compressive strengths of B3, B9, and B15 are 32.5 MPa, 33.3 MPa, and 32.7 MPa, showing increases of 2.1 MPa, 2.9 MPa, and 2.3 MPa compared to the 28-day compressive strength of flawed excavated-mass aggregate concrete.

Figure 12.

Compressive strength of concrete.

After immersion in the strengthening slurry, the sodium silicate dehydrates and solidifies within the flawed excavated-mass aggregates, forming silicon dioxide crystals that fill the cracks and pores. This enhances the mechanical properties of the strengthened aggregates and reduces their crushing index. Simultaneously, a large number of silicate crystals adhere to the surface of the strengthened aggregates. During concrete mixing, these silicate crystals partially detach from the aggregate surface due to collisions and friction, dispersing into the concrete matrix. There, they undergo a secondary crystallization reaction with calcium hydroxide produced during cement hydration, forming calcium silicate and other substances, thereby promoting cement hydration and improving the mortar strength of the fresh concrete. Silicate crystals that remain attached to the strengthened aggregate surface directly undergo a secondary crystallization reaction with calcium hydroxide from cement hydration in the ITZ (interfacial transition zone), generating calcium silicate gel. This improves the ITZ microstructure and enhances its strength, consequently increasing the compressive strength of the strengthened aggregate concrete.

4.3. Microstructure of the Interface Transition Zone

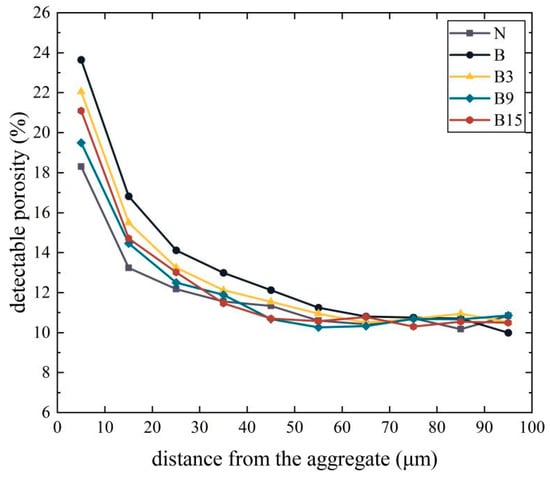

Analysis of Table 3 reveals that the porosity of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) in the concretes tested gradually decreases with increasing distance from the aggregate surface, stabilizing at 11%. This indicates that the porosity of the mortar matrix in the concrete is 11%, and this value represents the boundary between the ITZ and the mortar. Based on this, the ITZ thickness of each concrete can be calculated. The ITZ thickness is 50 μm for N, 60 μm for B, 50 μm for B3, and 40 μm for B9. The ITZ thickness is 40 μm for B9. Comparing the ITZ thicknesses, it is evident that immersion in a strengthening slurry reduces ITZ thickness. This is because some silicate crystals attached to the strengthened aggregate surface detach from the aggregate surface, disperse into the concrete matrix, and undergo a secondary crystallization reaction with calcium hydroxide produced by cement hydration, forming calcium silicate and other substances. This promotes cement hydration, effectively reducing the porosity at the ITZ edge, thus transforming it into ordinary mortar and decreasing the ITZ thickness.

Table 3.

Test results of porosity of the concrete interfacial transition zone.

Figure 13 illustrates the variation in porosity of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) of various concretes with increasing distance from the aggregate surface. As can be seen, the porosity of the ITZ is higher closer to the aggregate surface. This is mainly because a water film forms around the aggregate during hydration, resulting in a higher water-cement ratio in the mortar closer to the aggregate surface, and a higher content of large crystalline hydrates. Furthermore, due to the incompatibility between the aggregate and the mortar, the porosity of the mortar closer to the aggregate surface is higher. Within the ITZ range, the ITZ porosity of natural aggregate concrete is the lowest. The ITZ porosity decreases sequentially from B, B3, to B9, indicating that immersion in a strengthening slurry can reduce the ITZ porosity. The higher the concentration of the strengthening slurry, the more significant the reduction in ITZ porosity. This is because the unreacted silicate on the strengthened aggregate surface directly undergoes a secondary crystallization reaction with calcium hydroxide produced by cement hydration in the ITZ, generating calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which promotes cement hydration and effectively reduces the ITZ porosity, improving the microstructure of the ITZ. However, the ITZ porosity of B15 is slightly higher than that of B9. This may be because after the silicate attached to the strengthened aggregate surface has fully reacted with the Ca(OH)2 produced by cement hydration, some crystal residue remains. These silicate crystals are formed by the dehydration and hardening of sodium silicate. The hardening of sodium silicate is a slow process; the sodium silicate on the surface first dehydrates and hardens to form crystals, while the interior of the sodium silicate still contains a large amount of uncured sodium silicate, which contains moisture. After this portion of water slowly evaporates, it leaves a large number of pore structures inside the silicate crystals, resulting in a slight increase in the ITZ porosity of B15.

Figure 13.

Porosity of the concrete interfacial transition zone of different groups.

5. Conclusions

- Sodium borate, sodium hexametaphosphate, and polycarboxylic acid substances are used to modify sodium silicate, producing a strengthened slurry primarily composed of sodium silicate. The reinforcement effect on flawed excavated-mass aggregates is optimized by expanding the penetration pathways and increasing the strength of the crystals. Sodium borate forms a composite network structure with silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, while sodium hexametaphosphate interlocks with silicon–oxygen tetrahedra to enhance the strength of silicon dioxide crystals. Polycarboxylic acid substances improve the stability of the sodium silicate system, reduce its size, and increase its wettability on defective aggregates.

- The crushing value and water absorption of flawed excavated-mass aggregates decrease continuously with increasing concentration of the strengthening slurry. Higher concentrations of strengthening slurry lead to a greater amount of sodium silicate entering the aggregate’s interior, resulting in more silica crystals forming during air-drying through dehydration, and a more pronounced filling effect on the pore structure of the defective aggregates.

- Crystalline silica formed by dehydration and hardening within the flawed excavated-mass aggregates after impregnation with the strengthening slurry densifies the pore structure, reducing its total porosity. Higher concentrations of the strengthening slurry result in lower total porosity. Simultaneously, the pore structure of the flawed excavated-mass aggregates is refined, the pore size distribution curve is optimized, and the average pore size and the most probable pore size are reduced.

- Soaking aggregate in strengthening slurry can improve the workability and slump of reinforced aggregate concrete. Furthermore, it enhances the compressive and flexural strength of the concrete. Higher slurry concentration leads to greater improvements in these strength properties. The strengthening effect of the slurry on the concrete’s mechanical strength is most pronounced during the early stages of curing.

- The porosity of the Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) increases closer to the aggregate surface. Impregnating with a strengthening slurry can reduce both the porosity and thickness of the ITZ. Higher concentrations of the strengthening slurry result in a more significant reduction in ITZ porosity. Silicates attached to the surface of the strengthened aggregate undergo a secondary crystallization reaction with calcium hydroxide, a product of cement hydration in the ITZ, forming calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel. This promotes cement hydration, effectively decreasing ITZ porosity and improving the ITZ microstructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. (Mengliang Li) and X.L.; methodology, M.L. (Miao Lv); software, H.B.; validation, M.L. (Mengliang Li), Z.R. and X.L.; formal analysis, H.B.; investigation, M.L. (Mengliang Li) and H.B.; resources, X.L.; data curation, Z.R. and M.L. (Miao Lv); writing—original draft preparation, M.L. (Mengliang Li); writing—review and editing, H.B., X.L., Z.R. and M.L. (Miao Lv); visualization, M.L. (Mengliang Li) and M.L. (Miao Lv); supervision, M.L. (Miao Lv); project administration, H.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dongyang Shimatan Reservoir Consulting Project of Sinohydro Bureau 12 Co., Ltd.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Mr. Mengliang Li was employed by the company Sinohydro Bureau 12 Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare that this study received funding from the Dongyang Shimatan Reservoir Consulting Project of Sinohydro Bureau 12 Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Wongvatana, N.; Noorak, A.; Poorahong, H.; Jongpradist, P.; Chaiprakaikeow, S.; Jamsawang, P. Sustainable road construction materials incorporating dam sediment and eucalyptus ash waste: A circular economy framework. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharghi, M.; Jeong, H. The potential of recycling and reusing waste materials in underground construction: A review of sustainable practices and challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, H.; Chamasemani, N.F.; Mashayekhi, M.; Hamzehkolaei, N.S.; Santos, P. Sustainability Enhancement and Evaluation of a Concrete Dam Using Recycling. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Wu, Y. Durability Performance of CGF Stone Waste Road Base Materials under Dry–Wet and Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Materials 2024, 17, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Yao, Y.; Huang, C. Utilization of Tunnel Waste Slag for Cement-Stabilized Base Layers in Highway Engineering. Materials 2024, 17, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Niu, F.; Lin, Z.; Shang, Y.; Nimbalkar, S.; Sheng, D. Experimental and numerical analyses on the frost heave deformation of reclaimed gravel from a tunnel excavation as a structural fill in cold mountainous regions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Lü, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Xu, K. Study on mechanical property and breakage behavior of tunnel slag containing weak rocks as road construction material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokgöz, N. Use of TBM excavated materials as rock filling material in an abandoned quarry pit designed for water storage. Eng. Geol. 2013, 153, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuaim, A.; Abbas, Y.M.; Khan, M.I. Sustainable application of processed TBM excavated rock material as green structural concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274, 121245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabiec, M.A.; Klama, J.; Zawal, D.; Krupa, D. Modification of recycled concrete aggregate by calcium carbonate biodeposition. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 34, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Tng, S.Q.D.; Yang, E. Surface treatment of recycled concrete aggregates through microbial carbonate precipitation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 57, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Si, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Yang, L. Research on the properties and modification mechanism of microbial mineralization deposition modified recycled concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasanipour, H.; Aslani, F. Durability properties evaluation of self-compacting concrete prepared with waste fine and coarse recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 236, 117540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belabbas, O.; Bouziadi, F.; Boulekbache, B.; Hamrat, M.; Haddi, A.; Amziane, S. Mechanical properties of multi-recycled coarse aggregate concrete, with particular emphasis on experimental and numerical assessment of shrinkage at different curing temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89, 109333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, D. Research progress on fiber-reinforced recycled brick aggregate concrete: A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, K.; Luo, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, F. Effects of brick-concrete aggregates on the mechanical properties of basalt fiber reinforced recycled waste concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Ding, L.; Zhao, H. Performance evaluation of strengthening recycled coarse aggregate in cement stabilized mixture base layer of pavement. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8821048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Han, S.; Guo, Y. Recycled coarse aggregate from waste concrete strengthened by microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.C.; Poon, C.S.; Wan, H.W. Properties of concrete prepared with low-grade recycled aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.C.; Chu, J.J. Microstructure and physical properties of concrete containing recycled aggregates pre-treated by a nano-silica soaking method. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104363. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Nogueira, R.; de Brito, J.; Liu, J. A simple method to address the high water absorption of recycled aggregates in cementitious mixes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Chong, L.; He, Z. Performance enhancement of recycled concrete aggregate—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, P.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Quan, W.; Guo, Y. Mix proportion design method of recycled brick aggregate concrete based on aggregate skeleton theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 304, 124584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.S. The study of formation colloidal silica via sodium silicate. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2004, 106, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, J.S., Jr.; Bass, J.L.; Angelella, M.; Schenk, E.R.; Brensinger, K.A. The determination of sodium silicate composition using ATR FT-IR. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 6287–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Liu, F.; Fan, Z. Investigation of parameters and mechanism of ultrasound-assisted wet reclamation of waste sodium silicate sands. Int. J. Cast Met. Res. 2018, 31, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wen, K.; Dang, W.; Xun, J. Strengthening the inhibition effect of sodium silicate on muscovite by electrochemical modification. Miner. Eng. 2021, 161, 106731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, G. Mechanical properties, microstructure and consolidation of sand modified with sodium silicate. Eng. Geol. 2022, 310, 106875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, T.N.; Vu, T.N.M. Effects of Disodium Hydrogen Phosphate Addition and Heat Treatment on the Formation of Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Gel. JST Eng. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 31, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.M.; Yang, H.C.; Chun, B.S.; Lee, S.H. The effect of sodium tripolyphosphate on sodium silicate-cement grout. Mater. Sci. Forum 2005, 486, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Liu, W.; Han, F.; Li, Y. Effect of silica fume on humidity resistance of sodium silicate binder for core-making process. Int. J. Met. 2020, 14, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysen, B. Physics and chemistry of silicate glasses and melts. Eur. J. Mineral. 2003, 15, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, J.C.; Schomborg, L.; Rüscher, C.H. Hydrogen Storage; Liu, J., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; Chapter 38722. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.Y. Alkaline hydrolysis of sodium trimetaphosphate in concentrated solutions and its role in built detergents. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1966, 5, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.