The Effect of Sewer-Derived Airflows on Air Pressure Dynamics in Building Drainage Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Introduction of New Terms for Building Drainage Systems

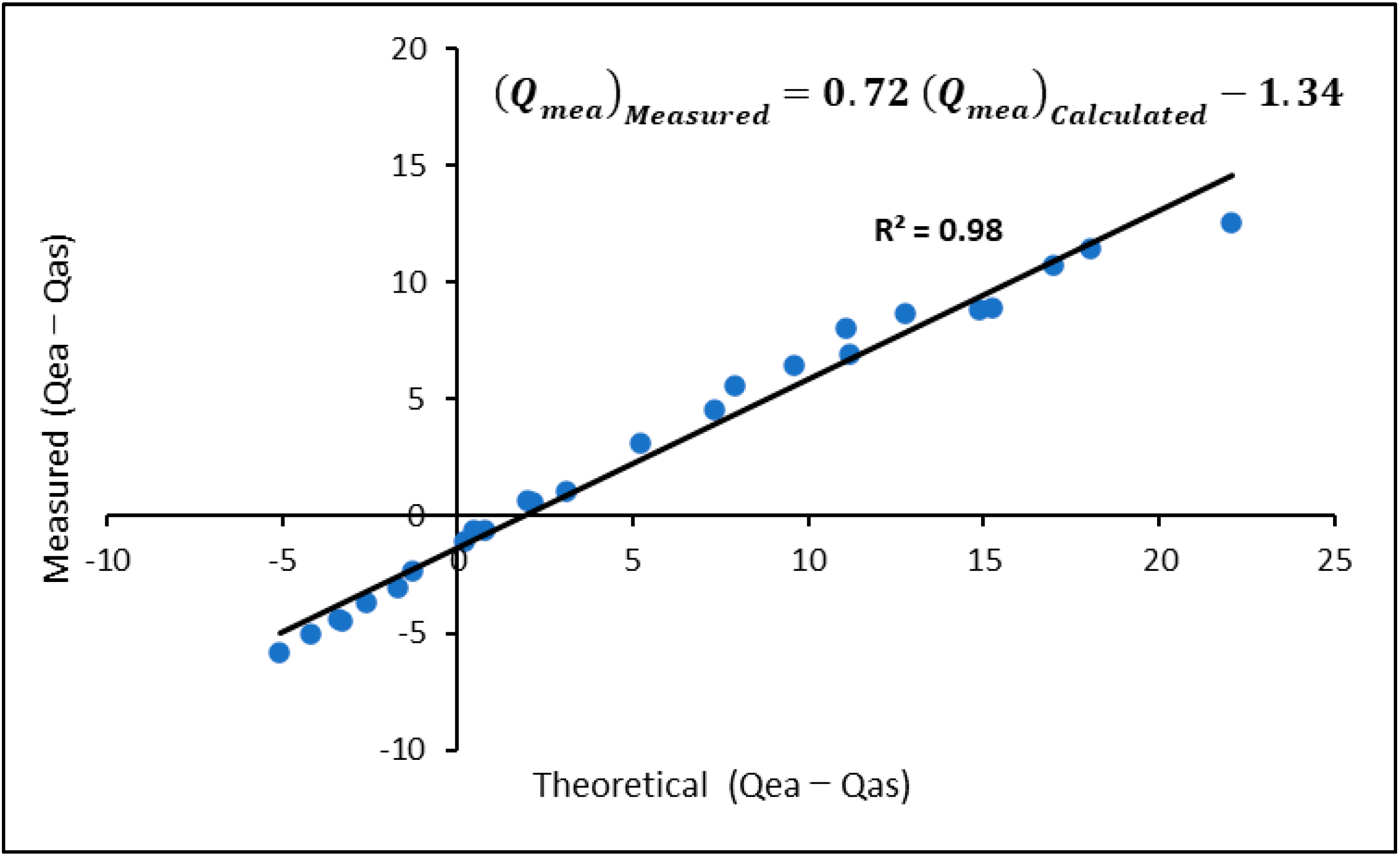

2.1. Modified Entrained Air (Qmea)

- is modified entrained air from measurement = ; is modified entrained air from calculation = ;

- Qea is the entrained air associated with water flow (L/s);

- Qas is the airflow from the sewer (L/s).

2.2. Classical Pressure Profile and Modified Air Pressure Due to Sewer Air ()

3. Methods and Procedures

- Build laboratory test rig;

- Conduct experiments;

- Develop model equations based on experiments;

- Validate model using 3-floor test rig;

- Validate model using 32-floor test rig NLT;

- Confirm applicability of the model and its impact on air pressure regimes.

3.1. Experiment 1: Methodological Approach for Investigating Pressure Losses Due to Sewer Air

Test Procedure

- (i)

- To measure the induced continuous airflow within the system;

- (ii)

- To measure pressure fluctuations along different pipe lengths;

- (iii)

- To analyse the system’s response to these changes in pipe length.

3.2. Experiment 2: Three-Storey Single-Stack Test Rig—Steady Flow Conditions

- (i)

- How the entrained airflow rate is modified by airflow from the sewer;

- (ii)

- The influence of sewer air on air pressures across the bend at the base of the stack.

Test Procedure

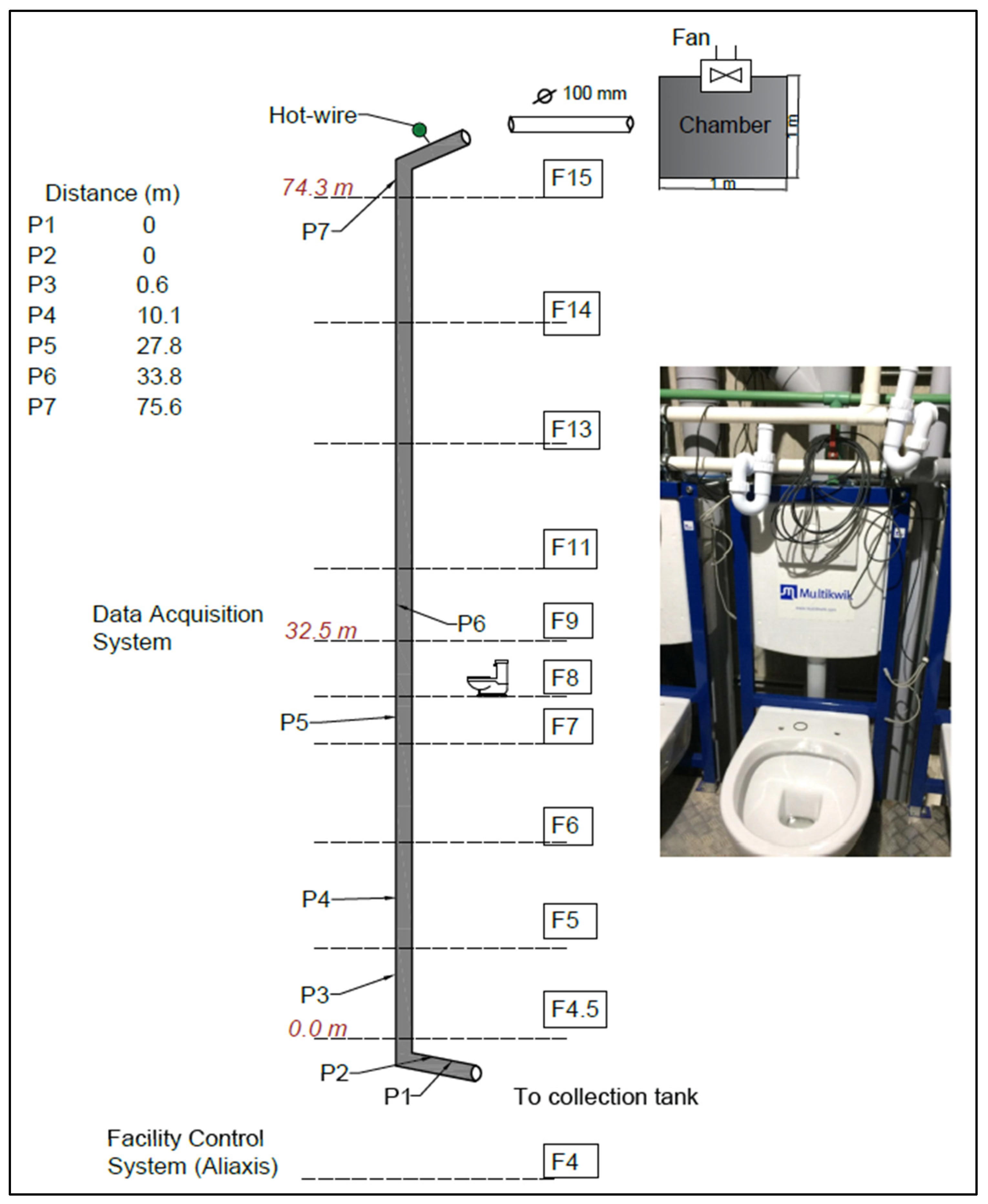

3.3. Experiment 3: Thirty-Two-Storey Single-Stack Test Rig—Unsteady Flow Conditions

Test Procedure

- (i)

- How the entrained airflow rate is modified by airflow from the sewer;

- (ii)

- How a single water flow event results in a range of pressure changes along the drainage stack under varying updraft airflow conditions.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Modification of Entrained Air (Qmea) by Updraft Air (Qas)

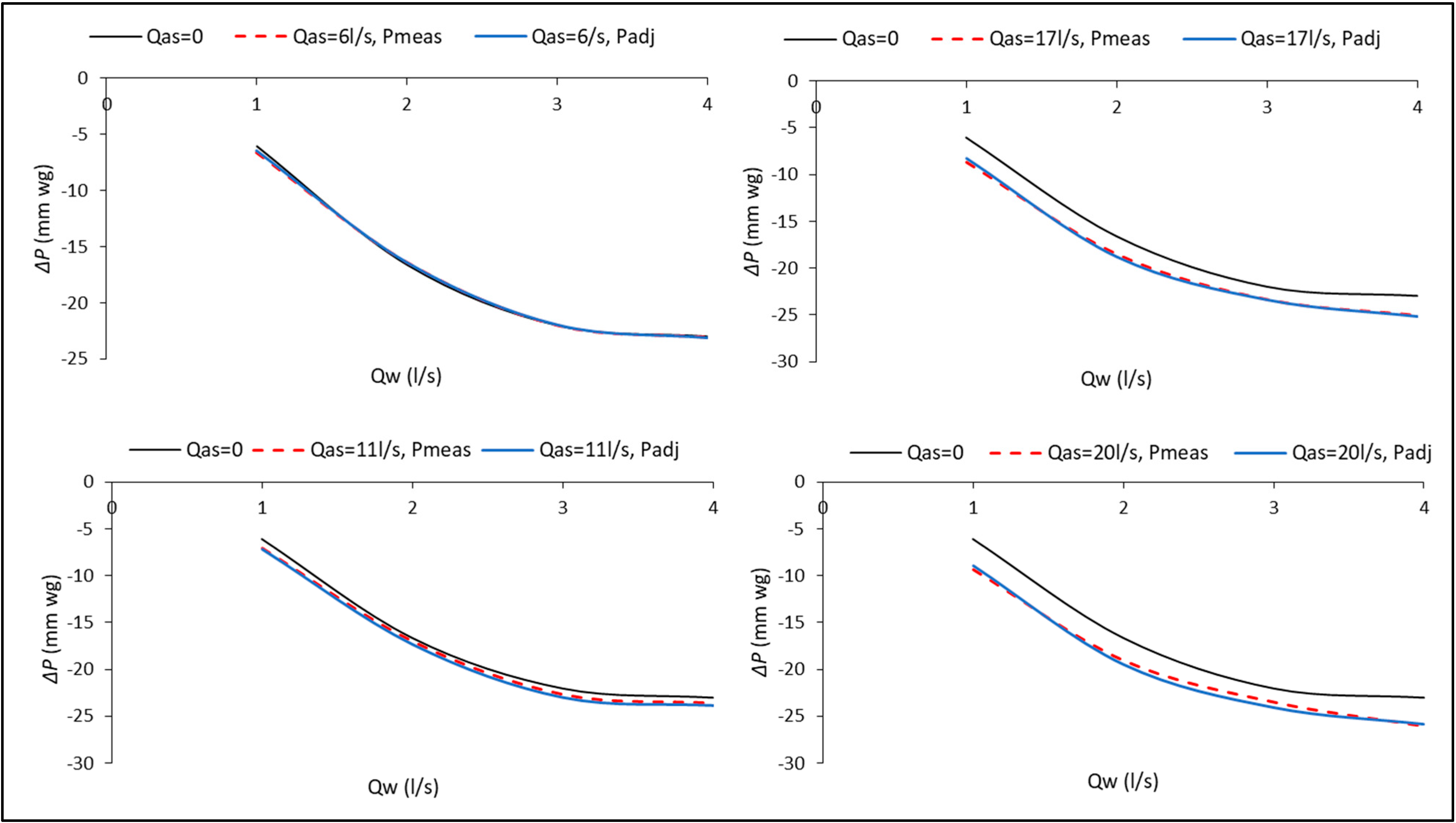

4.2. Modified Air Pressure Distribution

4.3. Applied Developed Model Equations for the Dry Stack Exposed to Sewer Air

4.3.1. Laboratory Test Rig: Three-Storey Building

4.3.2. NLT Test Rig

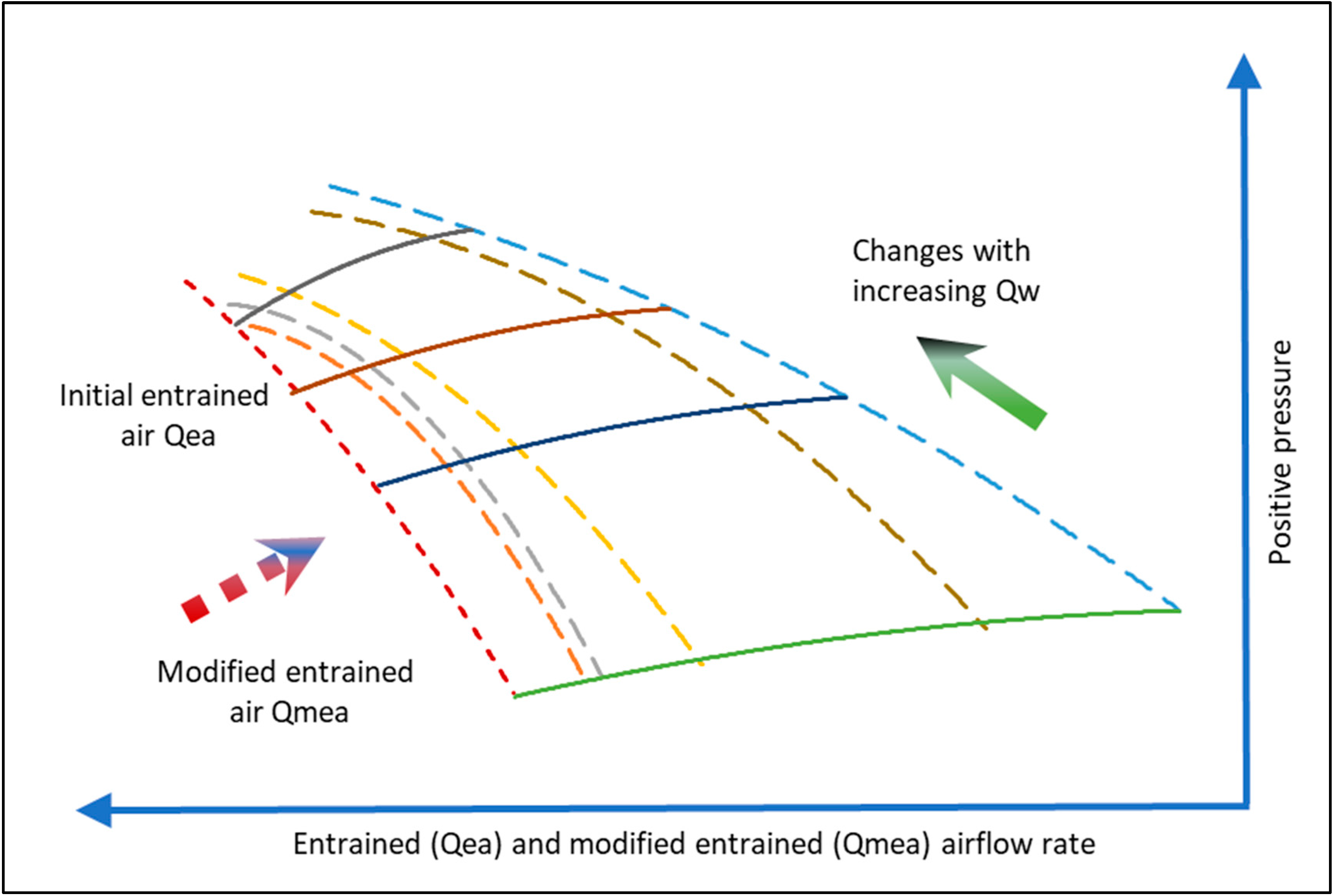

4.4. Development of a New Conceptual Diagram for Building Drainage Systems Exposed to Sewer Air

- The modification of entrained air due to sewer air;

- The reduction in initial entrained air with higher updraft air rates;

- The increase in positive or negative pressure with increasing water flow;

- The increase in positive and negative pressure with adjusted modified entrained air.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swaffield, J. Transient Airflow in Building Drainage Systems; Tylor& Francis: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- El-Housni, H.; Duchesne, S.; Mailhot, A. Predicting Individual Hydraulic Performance of Sewer Pipes in Context of Climate Change. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 752:2017; Drain and Sewer Systems Outside Buildings. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 2017.

- BS EN 12056-2:2000; Gravity Drainage Systems Inside Buildings. Sanitary Pipework, Layout and Calculation. BSI: London, UK, 2000.

- Sharif, K.; Gormley, M. Integrating the Design of Tall Building, Wastewater Drainage Systems into the Public Sewer Network: A Review of the Current State of the Art. Water 2021, 13, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Shao, W.; Zhu, D.Z.; Mohamad, K.A.A.; Steffler, P.M.; Edwini-Bonsu, S.; Yue, D.; Krywiak, D. Modeling Air Flow in Sanitary Sewer Systems: A Review. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2021, 38, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, K.; Gormley, M. Exploring the Impact of Sewer-Derived Airflows on the Air-Pressure Dynamics Within Building Drainage Systems; Heriot-Watt University: Edinburgh, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Consensus Document on the Epidemiology of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley, M.; Templeton, K.E.; Kelly, D.A.; Hardie, A. Environmental Conditions and the Prevalence of Norovirus in Hospital Building Drainage System Wastewater and Airflows. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2013, 35, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, M.; Aspray, T.J.; Kelly, D.A.; Rodriguez-Gil, C. Pathogen Cross-Transmission via Building Sanitary Plumbing Systems in a Full Scale Pilot Test-Rig. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, H.C.K.; Chan, D.W.T.; Law, L.K.C.; Chan, E.H.W.; Wong, E.S.W. Industrial Experience and Research into the Causes of SARS Virus Transmission in a High-Rise Residential Housing Estate in Hong Kong. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2006, 27, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, M.; Aspray, T.J.; Kelly, D. Bio-Aerosol Cross-Transmission via the Building Drainage System. In Proceedings of the Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate, Hong Kong, China, 7–12 July 2014; International Society of Indoor Air Quality and Climate: Chantilly, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley, M.; Kelly, D.; Campbell, D.; Xue, Y.; Stewart, C. Building Drainage System Design for Tall Buildings: Current Limitations and Public Health Implications. Buildings 2021, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, M.; Stewart, C. Design Methodologies for Sizing of Drainage Stacks and Vent Lines in High-Rise Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, J.A.; Campbell, D.P. The Simulation of Air Pressure Propagation in Building Drainage and Vent Systems. Build. Environ. 1995, 30, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, J.A.; Campbell, D.P.; Gormley, M. Pressure Transient Control: Part I—Criteria for Transient Analysis and Control. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2005, 26, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyly, S.R.; Eaton, H.N. Capacities of Stacks in Sanitary Drainage Systems For Buildings U.S.; US Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1961.

- Campbell, D.P. Mathmatical Modelling of Air Pressure Transients in Building Drainage and Vent Systems; Heriot Watt University: Edinburgh, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, L.B. An Investigation and Analysis of the Air Presssure Regime Within Building Drainage Vent System; Heriot Watt University: Edinburgh, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Swaffield, J.A.; Galowin, L.S. The Engineered Design of Building Drainage Systems; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Surrey, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley, M.; Mohammed, S.; Kelly, D.A.; Campbell, D.P. Application and Validation of AIRNET in Simulating Building Drainage Systems for Tall Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sharif, K.; Gormley, M. The Effect of Sewer-Derived Airflows on Air Pressure Dynamics in Building Drainage Systems. Buildings 2026, 16, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020256

Sharif K, Gormley M. The Effect of Sewer-Derived Airflows on Air Pressure Dynamics in Building Drainage Systems. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020256

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharif, Khanda, and Michael Gormley. 2026. "The Effect of Sewer-Derived Airflows on Air Pressure Dynamics in Building Drainage Systems" Buildings 16, no. 2: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020256

APA StyleSharif, K., & Gormley, M. (2026). The Effect of Sewer-Derived Airflows on Air Pressure Dynamics in Building Drainage Systems. Buildings, 16(2), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020256