Research Topic Identification and Trend Forecasting of Blockchain in the Construction Industry: Based on LDA-ARIMA Combined Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Method

2.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.2. LDA Model-Based Research Topic Identification

2.2.1. Determining the Optimal Number of Topics

2.2.2. Fitting the LDA Model

2.3. Calculating Topic Strength

2.4. Applying the ARIMA Model to Forecast the Development Trends of Blockchain in Construction Projects

2.4.1. Time Series Difference Processing and Test

2.4.2. Optimal Parameter Combinations and Model Validation

3. Results

3.1. Trend in Research Quantity

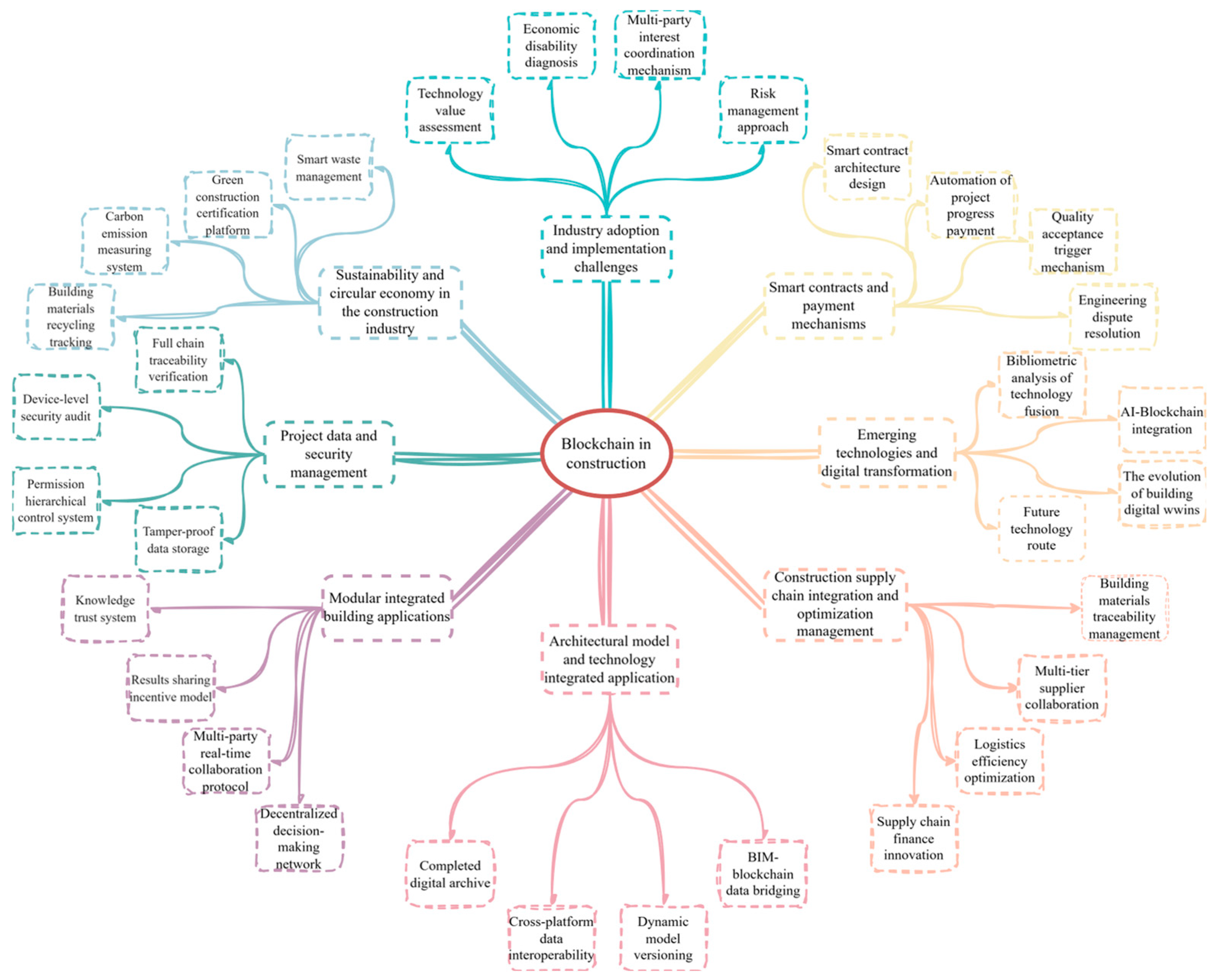

3.2. Identification of Research Topics

3.3. Research Topic Popularity Analysis

3.4. Topic Trend Prediction

4. Discussion

4.1. LDA Research Topic Analysis

4.1.1. Industry Adoption and Implementation Challenges

4.1.2. Project Data and Security Management

4.1.3. Emerging Technologies and Digital Transformation

4.1.4. Smart Contracts and Payment Mechanisms

4.1.5. Architectural Model and Technology Integrated Application

4.1.6. Modular Integrated Construction Applications

4.1.7. Sustainability and Circular Economy in the Construction Industry

4.1.8. Construction Supply Chain Integration and Optimization Management

4.2. ARIMA-Based Topic Forecasting and Analysis

4.2.1. Industry Adoption and Implementation Challenges Topic Forecast and Analysis

4.2.2. Project Data and Safety Management Topic Forecasting and Analysis

4.2.3. Forecast and Analysis of Emerging Technologies and Digital Transformation Topic

4.3. Comparison with Previous Bibliometric Studies

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, L.; Ghansah, F.; Zou, Y.; Ababio, B. Blockchain oracles for digital transformation in the AECO industry: Securing off-chain data flows for a trusted on-chain environment. Buildings 2025, 15, 3662. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, Ž.; Klinc, R. Potentials of blockchain technology for construction management. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Lee, G.; Kim, S. A study on the application of blockchain technology in the construction industry. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 24, 2561–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiu, M.S.; Chia, F.C.; Wong, P.F. Exploring the potentials of blockchain application in construction industry: A systematic review. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 2931–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, W.; Zhong, B.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Mehmood, I. Barrier identification, analysis and solutions of blockchain adoption in construction: A fuzzy DEMATEL and TOE integrated method. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2025, 32, 409–426. [Google Scholar]

- Shamshiri, A.; Ryu, K.R.; Park, J.Y. Text mining and natural language processing in construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Kang, P. Identifying core topics in technology and innovation management studies: A topic model approach. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 1291–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, B.; Pan, X.; Love, P.E.; Ding, L.; Fang, W. Deep learning and network analysis: Classifying and visualizing accident narratives in construction. Autom. Constr. 2020, 113, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.; Du, Y.; Zhang, L. A comparative analysis of Chinese green building policies from the central and local perspectives using LDA and SNA. Arch. Eng. Des. Manag. 2024, 20, 1037–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassandro, J.; Mirarchi, C.; Gholamzadehmir, M.; Pavan, A. Advancements and prospects in building information modeling (BIM) for construction: A review. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelodar, H.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Feng, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: Models, applications, a survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 15169–15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudnia, D.; Arashpour, M.; Yang, R. Blockchain in construction management: Applications, advantages and limitations. Autom. Constr. 2022, 140, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartoumi, K.I. Five-year review of blockchain in construction management: Scientometric and thematic analysis (2017–2023). Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105773. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Mao, C. Optimization of topic recognition model for news texts based on LDA. J. Digit. Inf. Manag. 2019, 17, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polatkan, G.; Zhou, M.; Carin, L.; Blei, D.; Daubechies, I. A Bayesian nonparametric approach to image super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2014, 37, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.; Shen, J.; Shen, C.; Li, J.; Kang, J.; Li, T. Construction engineering in China under green Transition: Policy research Topic clusters and development forecasts. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulrazzaq, H.; Alenezi, M.N.; Rawajfih, Y.; Alghannam, B.A.; Al-Hassan, A.A.; Al-Anzi, F.S. On the accuracy of ARIMA based prediction of COVID-19 spread. Results Phys. 2021, 27, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Guo, P.; Li, F.; Wu, Q. Research topic identification and trend prediction of China’s energy policy: A combined LDA-ARIMA approach. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119619. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Chong, H.Y.; Chi, M. Modelling the blockchain adoption barriers in the AEC industry. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2023, 30, 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, B.G.; Abraham, Y.S.; Attaran, M. Unlocking blockchain in construction: A systematic review of applications and barriers. Buildings 2024, 14, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuc, T.Q.; Nguyen, V.T.; Do, S.T. Barriers to the adoption of blockchain technology in the construction industry: A total interpretive structural modeling (TISM) and DEMATEL approach. Constr. Innov. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Chong, H.Y. Understanding the determinants of blockchain adoption in the engineering-construction industry: Multi-stakeholders’ analyses. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 108307–108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkesen, S.; Tezel, A. Investigating major challenges for industry 4.0 adoption among construction companies. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2022, 29, 1470–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Samsurijan, M.S. An appraisal of blockchain technology relevance in the 21st century Nigerian construction industry: Perspective from the built environment professionals. Glob. Oper. Strat. Sourc. 2023, 16, 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Adu-Amankwa, N.A.N.; Rahimian, F. Harnessing blockchain-enabled digital twins for building commissioning: Examining practitioners’ perspectives. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2025. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Zhong, B.; Fung, I.W.; Lee, Y.Y.R. Blockchain technology in the construction industry: Current status, challenges, and future directions. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 03122007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeb, A.; Keogh, J.G.; Simske, S.J.; Stafford, T.; Treiblmaier, H. Potentials of blockchain technologies for supply chain collaboration: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgun, A.P.; Koc, K. Administrative risks challenging the adoption of smart contracts in construction projects. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2022, 29, 989–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskula, K.; Kifokeris, D.; Papadonikolaki, E.; Rovas, D. Blockchain-based decentralized common data environment: User requirements and conceptual framework. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2025, 151, 04025112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, A.S.E.; Yiu, T.W.; Zou, Y.; Amor, R. Blockchain-aided information exchange records for design liability control and improved security. Autom. Constr. 2021, 126, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, Y.; Petri, I.; Barati, M. Blockchain supported BIM data provenance for construction projects. Comput. Ind. 2023, 144, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.S.; Waqar, A.; Radu, D.; Khan, A.M.; Dodo, Y.; Althoey, F.; Almujibah, H. Building information modeling (BIM) adoption for enhanced legal and contractual management in construction projects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.H.; Masoud, N.; Krishnan, M.S.; Li, V.C. Integrated digital twin and blockchain framework to support accountable information sharing in construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2021, 127, 103688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Liu, Y.; Wong, P.K.Y.; Chen, K.; Das, M.; Cheng, J.C. Confidentiality-minded framework for blockchain-based BIM design collaboration. Autom. Constr. 2022, 136, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, Y.; Petri, I.; Rezgui, Y. Integrating BIM and blockchain across construction lifecycle and supply chains. Comput. Ind. 2023, 148, 103886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Lu, W. A semantic differential transaction approach to minimizing information redundancy for BIM and blockchain integration. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadisheykhsarmast, S.; Aminbakhsh, S.; Sonmez, R.; Uysal, F. A transformative solution for construction safety: Blockchain-based system for accident information management. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2023, 35, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Hu, H.; Chai, Z.; Wang, W. Secure and formalized blockchain-IPFS information sharing in precast construction from the whole supply chain perspective. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04023150. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, A.; Ambekar, S. Digital transformation using blockchain technology in the construction industry. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2020, 22, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, A. Use of blockchain for enabling Construction 4.0. In Construction 4.0; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2020; pp. 395–418. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Han, S.; Zhu, Z. Blockchain technology toward smart construction: Review and future directions. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 03123002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.A.; Hassan, M.U.; Ullah, F.; Ahmed, K. Integrated building information modeling and blockchain system for decentralized progress payments in construction projects. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Sinaga, L.; Husin, A.E.; Arif, E.J.; Kristiyanto. Cost performance analysis of green chemical industrial buildings using, blockchain-BIM. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, K.; Hammad, A.W.; Pierott, R.; Tam, V.W.; Haddad, A. Integrating digital twin and blockchain for dynamic building life cycle sustainability assessment. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, F.; Marzouk, M. Integrated blockchain and digital twin framework for sustainable building energy management. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 43, 100747. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Lu, W.; Chen, C. Compliance checking for cross-border construction logistics clearance using blockchain smart contracts and oracles. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 2778–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Pan, X.; Ding, L.; Chen, Q.; Hu, X. Blockchain-driven integration technology for the AEC industry. Autom. Constr. 2023, 150, 104791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zeng, N.; König, M. Systematic literature review on smart contracts in the construction industry: Potentials, benefits, and challenges. Front. Eng. Manag. 2022, 9, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadisheykhsarmast, S.; Sonmez, R. A smart contract system for security of payment of construction contracts. Autom. Constr. 2020, 120, 103401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Deng, X.; Zhang, N. To what extent can smart contracts replace traditional contracts in construction project? Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2025, 32, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Heydari, M.; Shojaei, A. Blockchain applications in the construction supply chain. Autom. Constr. 2025, 171, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghaish, F.; Rahimian, F.P.; Hosseini, M.R.; Edwards, D.; Shelbourn, M. Financial management of construction projects: Hyperledger fabric and chaincode solutions. Autom. Constr. 2022, 137, 104185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerapperuma, U.S.; Rathnasinghe, A.P.; Jayasena, H.S.; Wijewickrama, C.S.; Thurairajah, N. A knowledge framework for blockchain-enabled smart contract adoption in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2025, 32, 374–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Lu, W.; Chen, C. Resolving power imbalances in construction payment using blockchain smart contracts. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2025, 32, 1875–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Jha, K.N. Determining delay accountability, compensation, and price variation using computable smart contracts in construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2024, 40, 04024013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Zeng, N.; Tao, X.; Han, D.; König, M. Smart contract generation and visualization for construction business process collaboration and automation: Upgraded workflow engine. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2024, 38, 04024030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, G.; Pheng, L.S.; Xia, R.L.Z. Adoption of smart contracts in the construction industry: An institutional analysis of drivers and barriers. Constr. Innov. 2023, 24, 1401–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozovsky, J.; Labonnote, N.; Vigren, O. Digital technologies in architecture, engineering, and construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105212. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.L.; Palha, R.P.; de Almeida Filho, A.T. Towards an integrative framework for BIM and artificial intelligence capabilities in smart architecture, engineering, construction, and operations projects. Autom. Constr. 2025, 174, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Wong, P.K.Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gong, X.; Zheng, C.; Cheng, J.C. Smart contract swarm and multi-branch structure for secure and efficient BIM versioning in blockchain-aided common data environment. Comput. Ind. 2023, 149, 103922. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, C.; Zhong, R.Y. Digital twin-enabled visibility and traceability for building materials in on-site fit-out construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 166, 105640. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Zhong, H.; Bolpagni, M. Integrating blockchain with building information modelling (BIM): A systematic review based on a sociotechnical system perspective. Constr. Innov. 2024, 24, 280–316. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Wu, L. A blockchain-based deployment framework for protecting building design intellectual property rights in collaborative digital environments. Comput. Ind. 2024, 159, 104098. [Google Scholar]

- Markou, I.; Sinnott, D.; Thomas, K. Current methodologies of creating material passports: A systematic literature review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, H.; Li, H.; Zhong, B.; Fung, I.W.; Lee, Y.Y.R. Exploring the adoption of blockchain in modular integrated construction projects: A game theory-based analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Hu, H.; Xu, F.; Chai, Z.; Wang, W. Blockchain-based security-minded information-sharing in precast construction supply chain management with scalability, efficiency and privacy improvements. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105698. [Google Scholar]

- Olawumi, T.O.; Chan, D.W.; Ojo, S.; Yam, M.C. Automating the modular construction process: A review of digital technologies and future directions with blockchain technology. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Zhong, R.Y.; Huang, G.Q. Blockchain-enabled digital twin collaboration platform for fit-out operations in modular integrated construction. Autom. Constr. 2023, 148, 104747. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Luk, C.; Zheng, B.; Hu, Y.; Chan, A.P.C. Disassembly and reuse of demountable modular building systems. J. Manag. Eng. 2025, 41, 05024012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Juan, Y.K.; Han, Q.; de Vries, B. An investigation on construction companies’ attitudes towards importance and adoption of circular economy strategies. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, E.C.; Sofolahan, O.; Ugulu, R.A.; Ameyaw, E.E. Bolstering circular economy in construction through digitalisation. Constr. Innov. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, A.; Ketabi, R.; Razkenari, M.; Hakim, H.; Wang, J. Enabling a circular economy in the built environment sector through blockchain technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, K.; Hammad, A.W.; Haddad, A.; Tam, V.W. Assessing the usability of blockchain for sustainability: Extending key themes to the construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343, 131047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghaish, F.; Hosseini, M.R.; Kocaturk, T.; Arashpour, M.; Ledari, M.B. Digitalised circular construction supply chain: An integrated BIM-blockchain solution. Autom. Constr. 2023, 148, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Wang, J.; Niu, D.; Nwetlawung, Z.E. Evaluating stakeholders’ decisions in a blockchain-based recycling construction waste project: A hybrid evolutionary game and system dynamics approach. Buildings 2024, 14, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Pishdad-Bozorgi, P. State-of-the-art review of blockchain-enabled construction supply chain. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 03121008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, B.; Gunathilake, L.; Edirisinghe, R.; Perera, S. EcoConstruct: A blockchain-based system for carbon trading in construction projects. Constr. Innov. 2025, 25, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badi, S. The role of blockchain in enabling inter-organisational supply chain alignment for value co-creation in the construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2024, 42, 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Papadonikolaki, E. Shifting trust in construction supply chains through blockchain technology. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2021, 28, 584–602. [Google Scholar]

- Dedehayir, O.; Steinert, M. The hype cycle model: A review and future directions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 108, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Nanayakkara, S.; Rodrigo, M.N.N.; Senaratne, S.; Weinand, R. Blockchain technology: Is it hype or real in the construction industry? J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 17, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A.; Alharbi, L.A.; Abdullah Alotaibi, F.; Alrasheed, K.A.; Khan, A.M.; Almujibah, H. Challenges of blockchain implementation in construction. J. Eng. 2024, 2024, 2442345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Topic Intensity | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Topic 1 | 130.33 | 1 |

| Topic 2 | 40.27 | 4 |

| Topic 3 | 54.18 | 3 |

| Topic 4 | 15.65 | 8 |

| Topic 5 | 35.62 | 5 |

| Topic 6 | 33.14 | 6 |

| Topic 7 | 111.40 | 2 |

| Topic 8 | 27.41 | 7 |

| Difference | Topics | Topic 1 | Topic 7 | Topic 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d = 0 | ADF_statistic | −6.8806 | ||

| p-value | <0.01 | |||

| d = 1 | ADF_statistic | −2.0922 | −0.6685 | |

| p-value | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Topic | AIC | BIC | Ljung–Box | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 1 | ARIMA (2, 1, 2) | 217.7241 | 230.6774 | 0.5912 > 0.1 |

| Topic 7 | ARIMA (2, 1, 2) | 208.4277 | 221.381 | 0.3255 > 0.1 |

| Topic 3 | ARIMA (2, 0, 2) | 136.9691 | 150.0154 | 0.9411 > 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, C.-Y.; Chong, H.-Y.; Cheng, M. Research Topic Identification and Trend Forecasting of Blockchain in the Construction Industry: Based on LDA-ARIMA Combined Method. Buildings 2026, 16, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020254

Xu Y, Zhang Z, Lee C-Y, Chong H-Y, Cheng M. Research Topic Identification and Trend Forecasting of Blockchain in the Construction Industry: Based on LDA-ARIMA Combined Method. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):254. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020254

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yongshun, Zhongyuan Zhang, Cen-Ying Lee, Heap-Yih Chong, and Mengyuan Cheng. 2026. "Research Topic Identification and Trend Forecasting of Blockchain in the Construction Industry: Based on LDA-ARIMA Combined Method" Buildings 16, no. 2: 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020254

APA StyleXu, Y., Zhang, Z., Lee, C.-Y., Chong, H.-Y., & Cheng, M. (2026). Research Topic Identification and Trend Forecasting of Blockchain in the Construction Industry: Based on LDA-ARIMA Combined Method. Buildings, 16(2), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020254