Abstract

Most current second-hand housing sales, contract signing, and other processes require the participation of intermediaries. However, suppose the intermediary refuses to disclose all information to the parties involved in the transactions. In that case, this traditional model can lead to weak supervision and punishment, adverse selection, moral hazards, and weak contract enforcement. Blockchain technology can not only secure the information intermediaries share, encouraging them to disclose information, but can also generate irreversible records of housing transactions for data traceability. Therefore, this study aims to develop a framework based on blockchain technology for the trading of second-hand housing. In this study, a second-hand housing online trading framework (SHHOTF) based on smart contract development is proposed for the second-hand housing business process, aiming to promote second-hand housing transactions. The contributions of this study lie in (1) determining the framework requirements, (2) proposing the functional module of a framework based on the blockchain and designing a complete business process, (3) developing an architecture for integrating blockchain and second-hand housing transaction processes, and developing technical components that support the framework functions, and (4) demonstrating the use case in Britain, analyzing the effectiveness and innovation of the framework. Furthermore, the framework demonstrated a 24% increase in transaction speed compared to the traditional Ethereum public network. The proposed process is highly adaptable within the current second-hand housing domain, and the developed framework can serve as a reference for introducing blockchain technology into other industries or application scenarios.

1. Introduction

Real estate is a capital-intensive industry. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2019, the value of second-hand houses in China reached 113 billion US dollars, accounting for nearly 50% of the real estate output value [1]. In addition, the National Economic Research Center of China predicted that by 2025, second-hand housing will account for more than 70% of the market share [2]. Therefore, the second-hand housing trading market is expected to expand in the future as the intensity of urban development and national regulation increases.

Most current second-hand housing sales, contract signing, and other processes require the participation of intermediaries. However, this traditional model has many disadvantages. First, there is often weak supervision of product and service processes and a lack of adequate means of punishment for illegal activities. Second, the intermediary may refuse to disclose all information to the parties involved in the transaction [3]; the widespread information asymmetry in real estate transactions can lead to adverse selection, moral hazards, and weak contract enforcement [4]. In addition, the unpredictability of intermediaries leads to an extremely low reliability of operation [5]. These problems distort second-hand housing market data. Government departments, financial institutions, and consumers cannot make logical decisions based on the data, nor can they effectively control risks in response to market changes. These issues restrict the development of the real estate market [6].

In response to the problems mentioned above, an online second-hand housing transaction framework has been suggested as being more efficient than the traditional system [7]. However, the scopes of operations of second-hand housing online platforms in different countries are not entirely consistent. Online platforms in China and the United States, such as Lianjia [8] and Zillow [9], can facilitate the entire process of purchasing a house in their respective countries. However, in the UK and other countries, online platforms such as Trustpilot [10] primarily serve as information-sharing platforms. When using platforms that can complete the entire process, consumers focus on the authenticity of houses [11], whereas when using information-sharing platforms, consumers focus on the evaluation of houses [12].

However, consumers have difficulty verifying the authenticity of the large amounts of information on the current platforms [13]. Some platforms even publish false housing information for profit. For example, Zillow [9] is exposed to click farming, wherein a large group of low-paid workers is hired to click on paid advertising links, which exacerbates the problem of information asymmetry [14]. Traditional platforms cannot effectively solve the problems of information transparency and traceability; however, the novel development of blockchain technology can provide a solution [15,16]. Many industries, including the medical [17,18], energy trading [19], and supply chain fields [20], have developed specific and sophisticated blockchain applications. By contrast, blockchain implementation in the building construction industry, particularly for second-hand housing trading, is still in its infancy [21,22]. Current research has confirmed that the application of blockchain in the intermediary field can reduce transaction time and costs and ensure transaction security [23,24]. However, the blockchain for the second-hand housing trading platform lacks clear identification of requirements, thorough function analysis, and a well-defined framework architecture. Therefore, this study aims to develop a framework based on blockchain technology for the trading of second-hand housing. In this study, a SHHOTF (Second-Hand Housing Transaction Framework) based on smart contract development is proposed for the second-hand housing business process, aiming to promote second-hand housing transactions.

The objectives of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- Use literature review and expert interviews to identify requirements for the framework, and perform functional analysis based on requirements.

- (2)

- Develop an architecture for integrating blockchain and second-hand housing transaction processes and develop technical components that support the framework functions.

- (3)

- Evaluate the performance of the SHHOTF. First, we aim to deploy the framework in the development environment based on the Ethereum blockchain network and trigger the corresponding smart contracts through three scenarios to verify its feasibility. Then, we plan to evaluate the performance based on two indicators, namely, storage cost and throughput.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the status of current research and identifies the gaps addressed in this study. In Section 3, the SHHOTF is introduced. Section 4 presents the implementation process of the second-hand house trading platform based on the blockchain. The results are presented and discussed in Section 5, and the conclusion and future research are presented in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

Given this research’s nature, our literature review covers two related streams: second-hand housing transaction model and blockchain technology.

2.1. Second-Hand Housing Transaction Model

As a fixed asset, housing transactions constitute a professional and meticulous process [11]. Therefore, in real housing transactions, buyers rely on certain groups with professional knowledge of housing transactions (these groups are the origin of real estate intermediaries). Traditional real estate agents deliver convenience to buyers but also certain inconvenience. For example, the storage of information by traditional intermediaries is very dubious; occasionally, information is lost. Moreover, traditional intermediaries rely on offline or telephone communication, which substantially increases the time and financial cost to buyers. Recently, intermediary companies have adopted digital methods for overcoming this dilemma. For example, Debenham [25] and Chu [26] proposed the use of a digital intermediary to perform paperless tasks. In addition, Lianjia [8], Letgo [27], and other companies have begun to deploy online trading platforms.

The rapid popularization of the Internet has accelerated the process of digitalization, which has had a large impact on the traditional intermediary industry. Zhang [28] and Chen et al. [29] stated that traditional intermediary agencies need to create higher value for buyers and sellers through innovation and reform. Specifically, a reduction in intermediary costs and shortening of the transaction cycle are necessary [30,31,32]. However, the specific application of online trading platforms is not straightforward. Li [16] observed that because of the high transaction volume of residential commodities, infrequent transactions, and many non-observable attributes, it is difficult to completely replace intermediary services with an online platform. Zhang [11] noted that market information asymmetry is more serious in online trading platforms for second-hand housing than it is for other fields and that a market using intermediary information services would approximately represent the Pareto optimal situation.

A number of scholars, such as Soto [32], believe that in online trading platforms, intermediaries take advantage of information asymmetry to generate income and further increase purchases, which is not conducive to the long-term operation and development of online second-hand housing transactions. On average, homes are sold at prices of 1.58% below the fair market price and are bought at prices of 1.22–8.36% above the fair market price [30]. To solve this problem, the concept of disintermediation has been utilized. The combination of disintermediation and the Internet has created a direct connection between the seller and the buyer. However, housing transactions cannot be completely disintermediated. The most critical reason for this is that once transactions are disintermediated, the probability of false housing information becomes unacceptably high. Therefore, solving the problem of false housing information is an important measure in the process of implementing online intermediaries.

To solve the aforementioned problems and promote the development of online second-hand housing transactions, Many scholars have proposed real estate trading frameworks supporting blockchain technology, making real estate transactions more transparent [33]. For example, Sharma et al. [34] proposed a real estate transaction process based on blockchain; however, it is limited by unclear identification of basic requirements for platform development. Ullah et al. [35] proposed a real estate transaction framework combining blockchain based on literature analysis and brainstorming methods. However, this system sometimes deviates from the real situation, overemphasizing security and ignoring the inherent logic of the transaction itself, which is, in fact, a reflection of the blockchain’s characteristics. Moreover, it does not account for the process of real estate transactions, resulting in a specific gap between the proposed framework and actual transactions. In other words, there are great differences between second-hand and new housing trading frameworks [36]. First, in some countries (e.g., China), new house transactions are more stringently regulated than second-hand house transactions, and the transaction process is more complicated. Some business activities (such as transferring and after-sales dispute handling) cannot be conducted within the framework. Therefore, if it is necessary to build a blockchain-based framework for second-hand housing transactions, it is essential to design functional modules and develop the framework based on the requirements of the trading platform.

2.2. Blockchain Technology

The security features and special structure of blockchains ensure data security. Due to this feature, blockchains can be applied in nearly any field. The classification of blockchains is generally the same across all fields [37], but the tools and applications based on blockchains may differ.

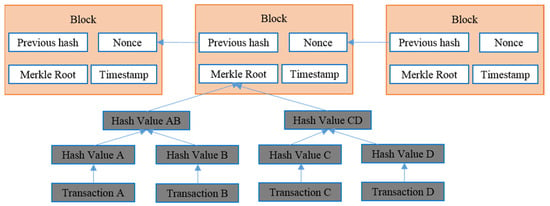

A complete blockchain system is a data structure that links block data in chronological order. Its core is a distributed ledger of a peer-to-peer network, and its basic unit is a block that includes key components such as the hash value, timestamp, Merkle tree root, and a random number [38]. Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental components of a blockchain. Blocks are indexed and connected by a hash value to ensure decentralization, data transparency, anti-tampering, traceability, privacy protection, and disclosure of the technical characteristics of the outsourcing process. Therefore, blockchain technology is suitable for solving the problem of information asymmetry in second-hand housing transactions [39,40]. The Merkle Tree Root is a cryptographic summary of all transactions within a block. It is generated by recursively hashing pairs of transaction hashes until a single root hash is obtained. This root enables efficient and secure verification of the entire set of transactions, allowing users to confirm the integrity and inclusion of specific transactions without revealing all transaction data. It plays a central role in ensuring the tamper-proof nature of blockchain ledgers.

Figure 1.

Basic units of a blockchain.

Smart contracts are widely regarded as one of the core technologies of blockchains. The life cycle of smart contracts can be divided into six stages: (1) negotiation, (2) development, (3) deployment, (4) operation and maintenance, (5) learning, and (6) self-destruction. Smart contracts are essentially business logic codes written for the needs of a given scenario; they are invoked when external applications interact with the general ledger [41,42]. The realization and execution of smart contracts rely on a safe and trusted environment [43]. Smart contracts support multiple languages such as Golang, Java, and Python [44]. Additionally, programming tools, such as Solidity [40,45] and Hyperledger Fabric [46], provide developers with various types of contract templates for different application scenarios, allowing them to quickly write smart contracts.

Given the tamper-proof and traceable advantages of the blockchain, researchers proposed that the architecture, engineering, construction, and operation (AECO) industry is generally considered a decentralized industry with low efficiency and productivity, and the emergence of blockchain technology may provide new opportunities for industrial transformation [47]. The industry has the potential to make business processes more efficient, traceable, transparent, and accountable at all stages of the project lifecycle [48,49]. In the real estate field, scholars explore the feasibility and potential of combining blockchain with the real estate field. Mayorov [50] proposed that “new technologies” (such as the cloud, artificial intelligence, big data, and distributed ledgers) should be used to transform frameworks to better adapt to current social developments. In Industry 4.0, blockchain technology will be applied to the real estate field to subvert traditional real estate [51]. However, although many scholars have studied blockchain in AECO industry, its overall development is still lagging behind [47]. The blockchain still requires significant development before it can be applied in these fields; this is particularly true for second-hand housing trading frameworks. There are only a small number of relevant studies on the development of blockchain technology for second-hand housing trading and the associated frameworks.

This study combined the advantages of existing platforms to ensure that the characteristics of blockchain can effectively reflect the real estate transaction process. At the same time, aiming to capture the uniqueness of the second-hand housing transaction process, this paper proposes a SHHOTF based on blockchain, drawing on expert interviews and relevant laws and regulations. At present, blockchain development technologies are primarily divided into Ethereum and Hyperledger Fabric [40,46]. We chose Ethereum for our blockchain platform as it is more convenient and user-friendly than Hyperledger Fabric [52]. This platform uses the alliance chain for node deployment, which combines the advantages of a fast private chain and transparent public chain information [53]. In addition, the proposed blockchain trading framework can be applied to general real estate blockchain trading frameworks and satisfy most second-hand housing trading scenarios based on the characteristics and business logic of the second-hand housing market [35]. Therefore, the contributions of this research are as follows:

(1) The blockchain application process followed in this study determines the problems through literature analysis, determines the needs through qualitative interviews, and designs the function modules as well as business processes.

(2) Based on the functional modules and business processes, a universal second-hand housing trading framework is developed for blockchain, and comprehensive testing and performance evaluation were conducted.

(3) The designed blockchain was then introduced into the second-hand housing transaction market. The proposed whole-process transaction framework can not only effectively solve the problem of false housing supply and ensure the authenticity of information but also improve transaction speed and reduce transaction cost. The proposed dynamic smart contract can be changed according to the business processes of different countries; hence, the framework has worldwide applicability.

3. Overview of SHHOTF Based on Blockchain

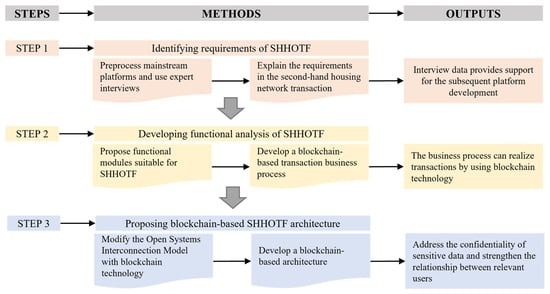

Current second-hand housing trading platforms include the functions of selling, buying, and net signing. In online second-hand housing transactions, it is challenging to ensure that platform users are operating in a stable environment. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the functional requirements of SHHOTF and determine the way blockchain technology can satisfy these functional requirements [54]. Specifically, this includes the determination of the following: the functional requirements of second-hand housing and the model architecture of SHHOTF. The overall process of second-hand housing trading is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing the overall process of SHHOTF.

3.1. Identification of Requirements for SHHOTF

To identify the requirements of SHHOTF, we first analyze the requirements of the existing second-hand housing online trading platforms in the world. The results are presented in Table 1 (the ticks indicate that the given platform possesses the corresponding functions).

Table 1.

Requirements of existing second-hand housing online trading platforms.

Next, we interviewed experts with second-hand housing sales experience and developers of second-hand housing trading platforms. The purpose was to determine the requirements of SHHOTF, lay a theoretical foundation for subsequent framework design and business process development, and increase the intelligence and security of the framework.

The interviews conducted for this study primarily included two parts: (1) respondents’ basic information (including age, years of work, company, and position), and (2) the respondents’ demand for the requirements of SHHOTF. The specific interview questions are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interview questions.

Based on bilateral market theory, the requirements were subdivided into those of the buyer and those of the seller according to the interview results. Because the realization of SHHOTF requires the joint participation of both buyers and sellers, the simple functions of either the buyer or seller are not the same as the overall requirements of the framework. Thus, it is necessary to systematically combine the requirements of both buyers and sellers in SHHOTF.

Hallowell and Gambatese [57] suggested two basic requirements for the qualification and number of experts in expert interviews. For qualification, it is necessary to meet the requirements of working years, identity, and status. The number of experts should be determined according to the characteristics of the study. To ensure the scientific efficacy of the expert interview, according to the above requirements, we horizontally compared the relevant literature of the blockchain framework designed based on the expert interview and found that Ullah [35] used an expert group composed of two professors, four doctors, and four real estate developers to conduct expert interviews, while Lu et al. conducted structured stakeholder interviews with a total of eight people [58]. Therefore, the number of experts was chosen as six, which meets the basic requirements of 3–20 people mentioned in the literature [59]. Based on the characteristics of second-hand housing, the experts selected in this study are industry experts with rich work experience. They had more than four years of rich experience, and their positions were at or above the level of manager. In addition, almost all respondents had an in-depth understanding of blockchain technology and were familiar with the business processes involved in online trading platforms, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Information regarding the interviewed experts.

3.2. Function Analysis of SHHOTF

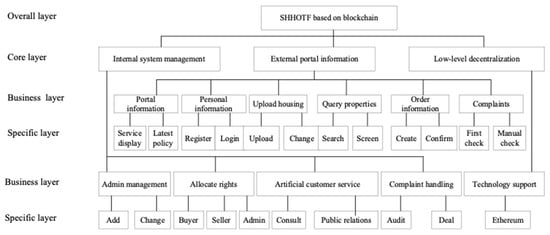

Based on interview data, we separated the needs of buyers and sellers according to expert interviews and applied the technical characteristics of blockchain technology to meet the corresponding needs (Table 4). The functional process designed based on the interview data was reviewed by two experts, E2 (senior intermediary) and E6 (platform R&D personnel), and finally we put forward a functional development framework diagram for SHHOTF, which is illustrated in Figure 3. The trading framework can be divided into three subsystems: the administrator system, user information system, and decentralized system. The administrator system is primarily for advanced operations, including user management, authority allocation, manual customer service, complaint handling, and other functions. The user information system is designed for both buyers and sellers and is the core embodiment of the framework’s function. Its main purpose is to streamline the entire process of second-hand housing transactions. The decentralized system serves as a reference for blockchains. At the interaction between the back and front ends of the framework, a decentralized application is constructed using blockchain technology. The framework function not only meets the needs of the traditional second-hand housing trading, but also integrates blockchain technology to lay the foundation for the actual development of the subsequent framework.

Table 4.

Functional requirements suggested by the interviewees.

Figure 3.

Hierarchy of the functional requirements for a blockchain-based SHHOTF.

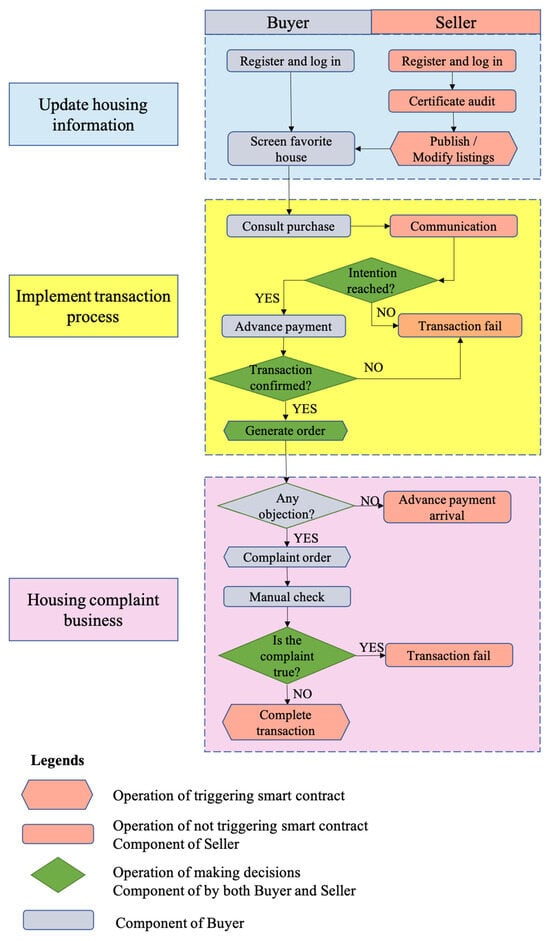

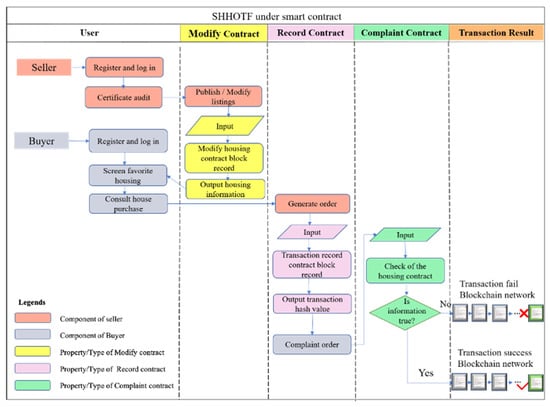

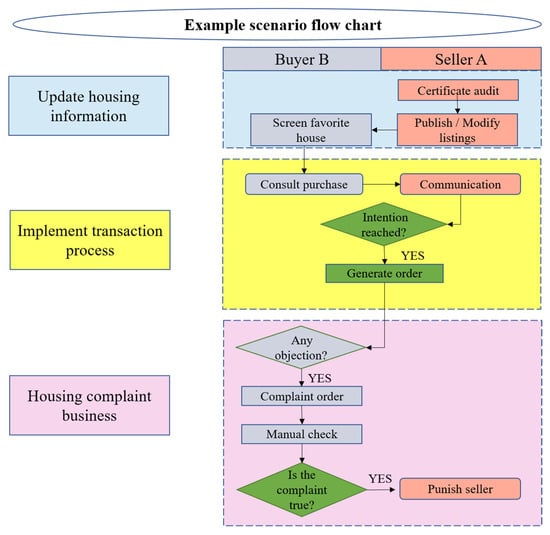

The SHHOTF we developed in this study is a decentralized transaction framework based on blockchain technology. The business process was analyzed and designed according to the functional modules of the framework. To better integrate blockchain technology into the trading framework, the framework’s business development implements the three processes of housing information updates, transactions, and false housing information complaints, which constitute a complete purchase process. The overall business process is shown in Figure 4, and the steps are outlined as follows:

Figure 4.

Business flow chart of a blockchain-based SHHOTF.

- (1)

- Updating the housing information

In transactions between the buyer and the seller, the seller publishes the house supply information, and the buyer screens the house supply. The main business logic for updating the housing information is as follows.

(a) The seller and buyer register and login on the relevant pages of the website. At the same time, to ensure the authenticity of housing information and the uniqueness of personal information, the seller conducts an identity audit.

(b) After the seller passes the identity audit, the housing information is uploaded or modified before the house is sold. The supplier uploads it according to the standardized format provided by the framework; this forms a simple database on the web page. Subsequently, the web page interacts with the information of the listing according to the modification contract uploaded to the framework. At this time, browsing the web page of the listing in the framework will automatically display the listing information.

(c) On the browser page, the buyer selects their preferred house through a house-listing operation. If a buyer sends an order request, the business logic of the transaction process is deemed open.

- (2)

- Implementing the transaction process

The main business logic for the transaction process is as follows.

(a) After the buyer selects the house and purchases a consultation, and the two sides reach the point of intending to execute a transaction, the purchase transaction officially begins. The buyer first submits a transaction application to the seller and sends the advance payment. After the seller agrees, the transaction is officially confirmed. Simultaneously, the framework interacts with the transaction record contract uploaded to the framework for block recording.

(b) After the block record is successful, the block hash value of the aforementioned transaction is returned, which indicates that the transaction is officially completed and the framework order information is generated.

(c) If the buyer has no objection to the subsequent transaction, the order will automatically end in a successful transaction, and the seller’s advance payment will arrive. If the buyer has any objection to the transaction, they can submit an order complaint. The order complaint is divided into two parts: checking order information and manual review. The order complaint automatically triggers a listing complaint contract for interaction and block recording.

- (3)

- Submitting false housing information complaints

The main business logic for the false housing information complaint process is as follows.

(a) For order information verification, a user can preliminarily check whether the current housing information is false. If the check shows that the housing information is false, manual review will be automatically triggered. If the returned housing information is not false, the buyer can choose to apply for a manual review. Otherwise, the order automatically skips to the transaction success stage.

(b) In the manual review stage, the uploaded false housing information complaint contract records the case and trial results in detail. If the complaint is true, the seller will be punished, and the order will skip to the transaction failure stage. If it is not true, the order will skip to the transaction success stage.

(c) When the order skips to the transaction success or transaction failure stage, the second-hand housing trading process ends. Operations that trigger smart contracts refer to actions that interact with the blockchain, such as generating transactions or submitting complaints, which result in on-chain data updates. Other actions, like browsing or inputting information, are handled off-chain and do not trigger contract execution.

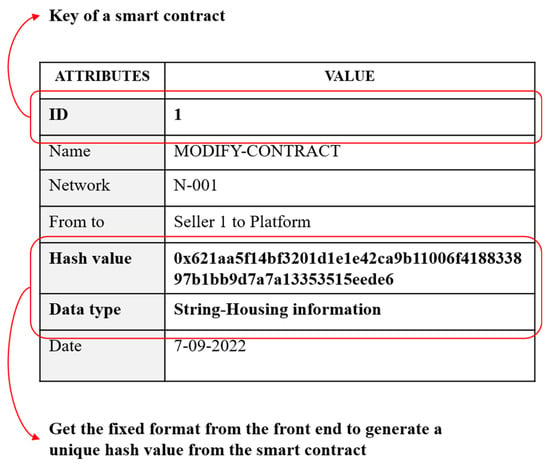

The development of smart contracts based on business processes needs to consider the principles of data model compatibility, integrity, and interoperability [60]. For the requirements of compatibility, this paper chooses Ethereum as the blockchain platform. Ethereum can accept the data model of key value relationship. For example, when the user executes the operation of triggering the smart contract on the front end, the front end will convert the relevant events into the data flow types that can be recognized by the smart contract and sent to the back end to execute the smart contract. Figure 5 shows the information of a data model. The model is the basic unit generated by triggering the smart contract operation as shown in Figure 4. The information of a smart contract whose key (file ID) is 1, and values (attributes) are name, network, and hash value, etc. For completeness requirement, a transaction must provide complete collaborative design information for all participants. For example, the smart contract in Figure 5 is tied to a model with a specific version; thus, a “Data type” row is designed to record which model and version this smart contract depends on or associated with as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Blockchain data model of the smart contract.

For integrity requirements, the information model data provided by each event is necessary and fixed. For example, the information model keys generated by modifying the housing source provided by different users as shown in Figure 5 are the same, but the values are different.

For interoperability requirements, events adopt a readable and compatible format in the second-hand housing transaction workflow. Table 5 presents the attributes and corresponding values of the general data model of the smart contract based on the business process design.

Table 5.

Attributes and corresponding values of the general data model of the smart contract.

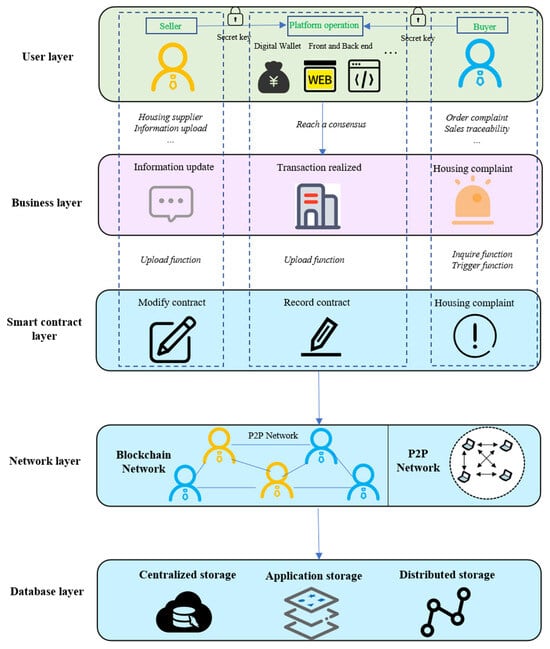

3.3. Blockchain-Based SHHOTF Architecture Development

The traditional blockchain structure has two limitations. First, the users of second-hand housing platforms want their sensitive data to remain confidential and are unwilling to disclose the data. Second, there is a trade-off between the storage capacity and running speed. Therefore, this paper proposes a blockchain-based SHHOTF architecture model that overcomes these limitations. The model diagram is divided into five layers (from top to bottom): (1) user, (2) business, (3) contract, (4) network, and (5) data. The structure is developed as a whole by imitating the TCP/IP five-layer structure and combining the characteristics of blockchains. Additionally, this structural model is similar to the current mainstream blockchain architecture [61]. Blockchains are more closely related to the latter three layers (contract, network, and data layers). The contract layer is the level where smart contracts are placed, and it serves as the bridge between the user and the business layers. The network and data layers guarantee the normal operation of the blockchain network. Therefore, the structure not only ensures the confidentiality of sensitive data, but also strengthens the relationship between relevant users. A series of methods, such as private chains and contract optimization, are used at the contract level to ensure sufficient storage capacity and speed. Thus, the function of the framework is identified at the user and business levels. The SHHOTF architecture model is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Proposed system architecture model for blockchain-based SHHOTF.

The user layer includes all the subjects involved in second-hand housing trading. There are two types of subjects: individual subjects and multi-individual organizations. The flow of information between subjects and organizations follows the network structure in which buyers and sellers form the main body. The buyer and seller are the starting points of second-hand housing trading. There are clear role differences between the two, and the nature of the business they conduct on the framework is different. In this layer, point-to-point (P2P) links can be carried out between users, and various problems in business processes can be solved through core blockchain technology to achieve mutually beneficial cooperation between buyers and sellers.

The business layer describes the overall process of second-hand housing trading. This operation can be carried out on the framework for both buyers and sellers. Users participating in the framework conduct second-hand housing trading through three business activities according to their respective needs: housing information updates, transaction processes, and false housing information complaints. To decentralize the entire process of second-hand housing trading, each business activity triggers a smart contract corresponding to the contract layer. To ensure the transactions are completed, each user receives support in terms of accurate provision of information and business activity policy.

The contract layer connects the business and network layers. When users trigger the contract corresponding to their business activities, the contract layer sends information to the network layer for blockchain technical support. The contract layer is based on three smart contracts: modified house supply, transaction record, and false housing information complaint. In modified house supply contracts, the input data type of the house supply contract is modified to a string, and no data are output. After the modification of the house supply contract is successful, the block corresponding to the business activity is officially and permanently saved on the trading framework. When subsequent business activities are generated, the transaction record contract queries the record of the current modified house supply contract block, and its output data consist of the transaction hash value saved by the buyer. Similarly, the transaction record contract generates the corresponding block. When the buyer has no objection to the order, the transaction is officially closed. If there is a complaint regarding the order, it will trigger a false housing information complaint contract; the contract block will also be uploaded to the trading framework for information traceability and network security.

The network layer is a framework layer that attempts to transport data from the source to the destination. Its core mechanisms include data dissemination and verification, P2P networking communication, and decentralized networking. It forms a decentralized network topology through two communication modes: full node and light node. In this structure, a series of unique blockchain activities can be performed. For example, users can publish information on the network through the node’s digital signature included in the transaction. When the information is verified, the broadcast protocol is executed and transmitted to the entire network. This process is tamper-proof, which ensures the security of information transmission, effectively suppresses the problem of false housing information, and solves the problem of trust in second-hand housing transactions. Therefore, this process overcomes the limitations of the traditional open systems interconnection (OSI) network layer.

The data layer is divided into two parts: conventional and blockchain. The traditional part is the data layer module represented by MySQL, which builds a database of data resources for the trading framework. It primarily uses the concepts of data blocks, data signatures, and Merkel trees to build the data organization, storage form, address key mechanism, and other cryptographic components of the blockchain. The data layer is the basis of the other four layers. The security of the data structure is maintained through the aforementioned concepts and modules. When using a database in business activities, the data are collected, maintained, and updated.

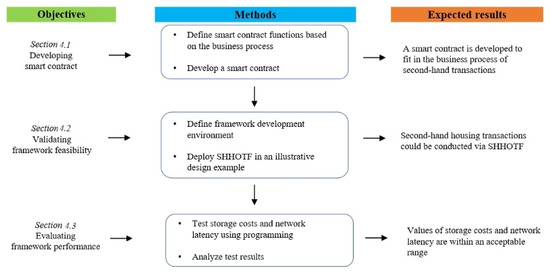

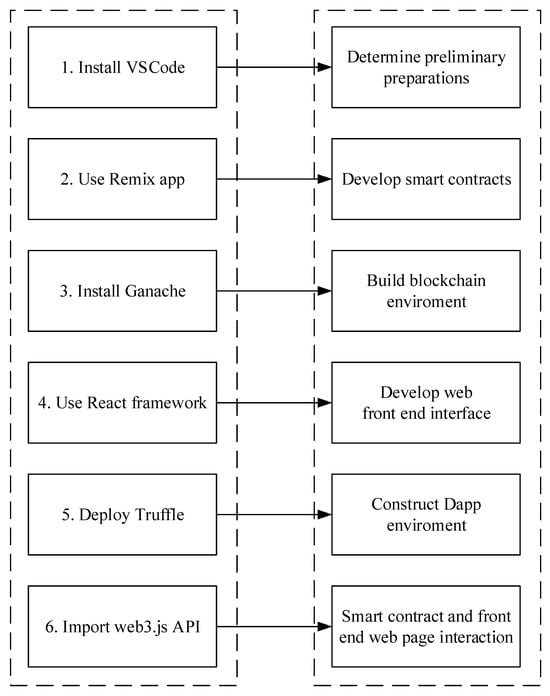

4. Implementation of SHHOTF Based on Blockchain

This part focuses on the implementation process of the second-hand house trading platform based on the blockchain. Section 4.1 develops the smart contract. Section 4.2 explains the feasibility of the blockchain based SHHOTF. Section 4.3 evaluates the performance of the framework. The flow chart of implementation is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Flow chart of implementation of SHHOF.

4.1. Smart Contract Development

The proposed business process is designed for the entire transaction process. Therefore, in this study, we researched and analyzed the laws of China, the United States, and other relevant countries that focus on the use of the whole process. Based on this analysis, the smart contract was designed and prepared so that it could execute workflows according to the legal requirements. It cannot fully prevent “mis-selling” and “mis-prolonging” in second-hand housing transactions, but blockchain technology can provide irreversible records of the transactions, which is solid evidence, providing higher confidence for the users.

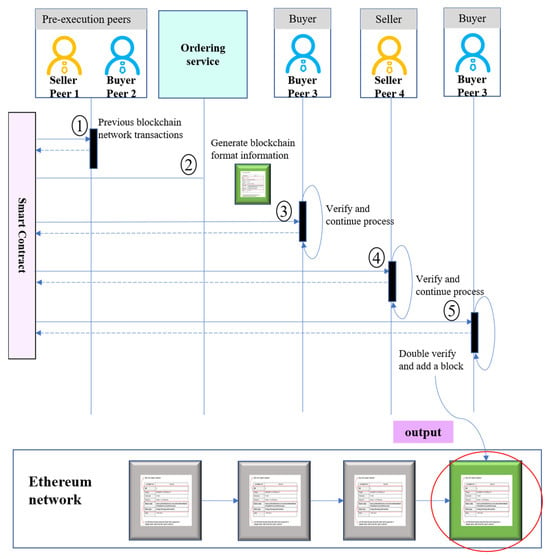

Smart contracts can safely ensure the normal workflow by verifying the digital signature and recorded password of users, and it can be verified in the future [62]. To meet the business logic and technical blockchain requirements of the framework, Ethereum is used for intelligent contract programming design because it has an open and collaborative community environment [52] and is more in line with the openness of second-hand housing transactions. In the contract design, different objects are stored in one contract through structure and mapping [63]. According to the analysis of business processes and functional requirements, in this study, we design and modify three contracts: housing supply contracts, transaction record contracts, and false housing information complaint contracts. These three contracts are designed using the Solidity language, which is a high-level language for smart contracts that runs on the Ethereum virtual machine, to facilitate the recording of information in housing supply transactions in the blockchain and to take advantage of the decentralization and information traceability of the private chain [44]. The trigger mechanism of the smart contract is shown in Figure 8. Only operations that involve blockchain verification or record creation will trigger smart contracts. Other auxiliary steps are completed off-chain to reduce system overhead.

Figure 8.

Smart contract trigger mechanism.

Modifying a housing supply contract records the seller’s modification of the housing information. Its objects include seller ID, seller mobile phone number, community city, community name, community location, expected price, contact name, and seven other items of information. The contract encapsulates an object through its structure. First, the contract is linked to the modifier and functions are constructed through the mapping function so that the web page data type can match the value in the smart contract. Because of the encapsulation, the contract call has specific permissions, and the seller must call the contract.

After the function connection is successful and the control authority is confirmed, the smart contract officially triggers the change function, which records the current housing supply information value and maps the housing supply information to a structure through the method of key value pairs. The specific mapping relationship is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Updating information contracts |

| Input: house data (e.g., community name) Output: blockchain ledger and display of information on the house for sale Step 1: Smart contract checks legality of file key and function name if address(seller) === address(msg.seller) return inputs are validated else Input invalid Step 2: Store data in blockchain ledger Hashcode ← Input data End |

A transaction process contract is used to record the transaction information generated in the process of second-hand housing transactions. This information includes the functions of obtaining current housing supply information, creating an order, and returning information on the order. The contract is mapped to the corresponding function using a hash. The specific information is shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Transaction process contracts |

| Input: Create order request Output: Order information (including hash) Step 1: function getInfo(): //get current house information return (buyer, _block_number) Step 2: function changestatus(buyer, _block_number): //create order if status === 1: // this means the order was created successfully goto step3 Step 3: function getOrderData(): return data such as orderId End |

The false housing information complaint contract is the core component of SHHOTF, which distinguishes it from all current second-hand housing trading frameworks. It represents the transformation of false housing information complaints from pure manual discrimination to an intelligent response. Utilizing the tamperability and traceability properties of blockchain technology, it protects the legitimate rights and interests of the buyer and ensures that those responsible for the complaints receive feedback and punishment. The false housing information complaint contract includes two functions: a preliminary audit and a manual review record. The specific algorithm is shown in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3: False housing information complaint contracts |

| Input: order data Output: feedback and hash Step 1: function returninfo: If _block_number === order_data: return valid and goto step 2 else return invalid and break Step 2: function firstcheck(block_number): if block_number === _block_number: return real property else return fake property Step 3: function manualReview(): End |

The above shows the pseudo code of the smart contract corresponding to the three business processes. Ethereum consensus mechanism adopts POS, and buyers and sellers call different smart contract functions through the consensus mechanism. In addition, as shown in Figure 9, the smart contract mechanism helps project members reach a consensus to ensure data consistency in the blockchain ledger by sorting the transaction sequence and verifying the signature.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of SHHOTF member consensus mechanism.

We understand that different countries and regions may have different requirements and workflows for second-hand housing selling. The proposed framework depends on smart contracts, which can be customized according to different needs and requirements. This paper only demonstrates the entire house purchase process that is generally carried out in China, the United States, and other regions. However, for countries that do not support online payment and online signing, such as the United Kingdom, the business process can be regarded as a part of the whole process. Therefore, based on the blockchain framework in this paper, we can design a SHHOTF that supports blockchain technology in different countries by dynamically modifying the smart contract.

4.2. Prototype and Experimental Setting

The specific development environment and tool configuration of the framework are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Environment and tool configuration of the second-hand housing trading platform.

Similar to apps being the essence of iOS and Android, distributed or decentralized applications (Dapps) are the essence of blockchain technology. We used a layered and extensible development process and framework for the Dapp of the second-hand housing online trading platform. Different developers can develop different layers, and react componentization is applied to combine the layers. The scalable and layered model enables interaction between components without interference across layers, supporting modular development and deployment. This encrypts information and achieves low coupling and high aggregation. In the development framework, the application architecture is divided into three layers: the user-oriented platform client (top layer), the front end for developing web pages (middle layer), and the back end for deploying smart contracts (bottom layer). The middle layer calls the bottom layer through the web3.js plug-in and correctly processes the top layer requests. A frame diagram of the Dapp is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Frame diagram of the blockchain Dapp.

This example comes from a real case in the UK. Buyer B spent 130,000 pounds to buy a second-hand house. Buyer B saw the bungalow on the website and contacted a real estate agent to buy the house. After the house was accepted, the buyer found that the house was full of garbage. Although Buyer B and Seller A reached an agreement and no longer investigated, this scenario revealed that there were still risks and unpredictable problems in the second-hand house transaction.

The example in SHHOTF completed the three processes (shown in Figure 11) involved in implementing smart contracts. The first step is the process of modifying the housing information. The housing information is stored in the underlying blockchain network so that it cannot be tampered with. The second step is the transaction process. The transaction information of the buyer and the seller is also stored in the blockchain network through the transaction record contract to ensure the authenticity of the information and the correctness of the call information for subsequent processes. The third step is the complaint process for false housing information. Compared with manual processing, this process is not only significantly faster but also more transparent. These beneficial properties can protect the rights and interests of buyers and promote the wholesome development of the second-hand housing market. In this case, smart contract-triggering steps include modifying housing data, submitting transaction requests, and filing complaints. Other steps are front-end interactions that do not involve blockchain updates.

Figure 11.

Case scenario flow chart.

According to the business logic flow chart, a user can carry out the three operations of modifying housing information, recording housing transactions, and submitting false housing information complaints, as follows.

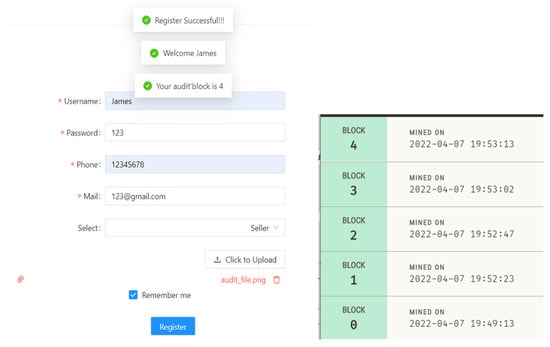

- (1)

- Modifying housing information contracts

The registered person must authenticate and submit their identity information, including their ID number or passport. To balance the authenticity and confidentiality of the privacy information, the information on the blockchain can only submit the identity information for the previously submitted identity information. The transaction framework can enhance the threshold through the authentication step, and the authentication information is deployed as an intelligent contract. This approach can save considerable time and cost. Due to blockchain’s immutability, the results of identity authentication queries on the network are trustworthy (as shown in Figure 12).

Figure 12.

The identity authentication information of the seller is on the blockchain.

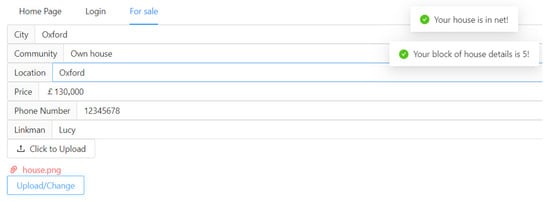

The seller can first obtain the current housing information on the housing modification page. If it is necessary to modify the housing information, the seller can enter the information in the seven input boxes (as shown in Figure 13) and click the “Submit” button. Then, the webpage will automatically submit the corresponding information to the uploaded housing information modification contract. The specific steps are outlined in Figure 14. The housing information written into the blockchain network guarantees the authenticity of the information and provides security for subsequent business processes.

Figure 13.

Sellers can revise the housing information on the housing information modification page.

Figure 14.

House information modification record.

- (2)

- Transaction process contracts

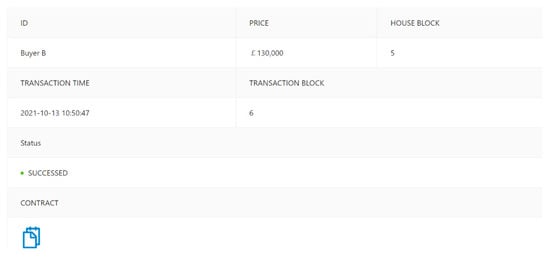

In this example, the buyer is satisfied with the seller’s selling price and wants to buy. The buyer can click the “buy house” button on the housing information page. The page then automatically loads the order page and asks the buyer to confirm. After being prompted, the webpage interacts with the uploaded transaction process contract and stores the order information in the blockchain network. After the order is formally created, the buyer obtains the block number of the house at the time of the transaction; this is used as the only voucher for subsequent complaint handling. The transaction order information is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Chart of transaction information.

- (3)

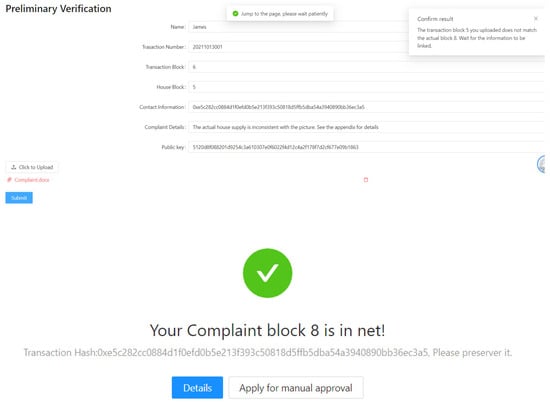

- False housing complaint contracts

The main functions of the false housing complaint contract interface include preliminary verification of the authenticity of the housing information and manual review of the order information. The interface completes transactions for buyers using the blockchain technology to protect the rights and interests of buyers. The preliminary verification of the housing information function is to match the house block number saved by the buyer when the order is created with the current house block number. If they are inconsistent, this will be relayed to the page to inform the buyer that the authenticity of the house cannot be guaranteed. In the case of the real example mentioned earlier, the order block number of Seller A’s transaction was 5; hence, Seller A used 5 to check the information. However, the current house block number was changed to 7 by Intermediary B. After the smart contract compared the 7 in the contract to the input of 5, it discovered that the values were unequal and returned an alert that indicated there was a problem with the housing information, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Screenshot of false housing information alert.

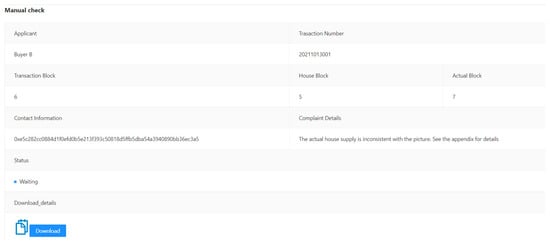

A manual review of the order information is the buyer’s final recourse. When the button is clicked, the information is submitted to the administrator for processing. After this, the administrator inputs the verification results into the blockchain network in the background, and then broadcasts and stores the results. In this example, after the initial check and return of the housing information, Seller A confirmed that the housing information of their transaction was inconsistent with the current housing information. Seller A could choose to apply for a manual review of the false housing information (see Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Screenshot of false housing information complaint submission.

In view of the non-tamperability and traceability of the blockchain, the authenticity of the information on the chain can be guaranteed. Therefore, in case of legal disputes, Buyer B can download the block information about the transaction through the framework to obtain supporting evidence. Thus, this system not only provides a means of recourse for Buyer B but also prevents Seller A from swindling Buyer B through the full use of blockchain technology.

4.3. Evaluation and Analysis

- Storage costs

Storage costs can be divided into two categories: general and data storage. The data storage cost covers the block data storage because the block storage size directly affects the operating speed and user experience of the platform’s services [64]. The blocks deployed on this framework use Ganache, which provides one-click local deployment blocks. Each user is provided with an account with 100 ETH, which is equivalent to 1 KB. The average number of users is 100,000. The calculation formula is:

where represents the total storage size, represents the numbers of block, and represents the storage size of each block.

Hence, the maximum capacity of the main blockchain of the project can only generate 97.67 MB (100,000/1024). In terms of current blockchain storage capacity, this is an acceptable size. The storage load can be released from the five-layer structure of the blockchain, particularly when valuable large files (such as video and model data) must be tracked [16].

- Latency

The latency performance in this study was evaluated using the concept of throughput. Throughput refers to the amount of successfully transmitted data per unit time for networks, equipment, ports, and other facilities [52,65]. The calculation formula is:

where represents the total Latency, and – refers to the buyer’s processing time, the seller’s processing time, the blockchain network processing time, and the interface response time, respectively. O represents other time. indicates the adjustment coefficient. The coefficient is between 0 and 10. The larger the value, the higher the requirements for delay performance. The test link is in a normal state of 1.

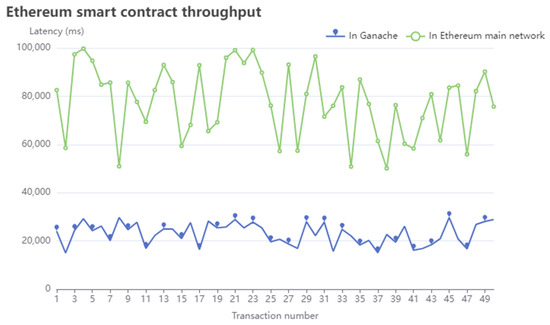

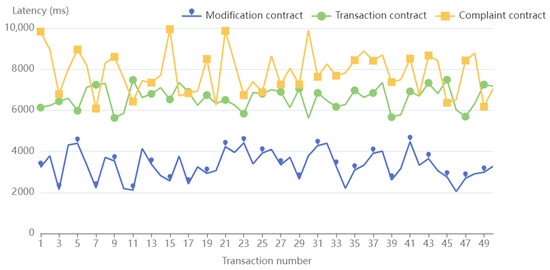

We measured the time taken by the contractor to release each transaction to the owner. Figure 18 shows the results of the top 50 transactions in the main Ethereum network. The average response time of the main network was approximately 10 s, which was unacceptably long because of the number of chains. Because Ganache was isolated from the main network of Ethereum, the response time was further optimized, with an average of approximately 3 s. Figure 19 shows the results of the first 50 transactions for the three contracts: the modification contract, transaction contract, and complaint contract. The results show that there was a systematic delay at the millisecond level, which indicates that there were significant differences between the rates at which the different contracts were processed. Modifying the contract is simple, and thus, the average response time for the modification contracts was approximately 3000 ms. By contrast, the complaint contracts were processed the slowest because they required waiting for feedback from the manager; their average response time was approximately 1 s.

Figure 18.

Test of throughput for the Ethereum main network and Ganache.

Figure 19.

Test of throughput for the three contracts in the framework.

Taking the Ethereum public network as an example, the public network block transaction speed was seven transactions per second. However, if the processing speed of Metamask was considered, the latency could be as high as approximately 3 s. In terms of transaction speed, there was a large leap, and the speed could increase by 24%. In the Ethereum public network, the average transaction speed is approximately 7 transactions per second (TPS), as referenced in our test (Figure 18). In our proposed framework using the Ganache environment, the effective transaction speed reached approximately 8.7 TPS. This represents a 24% increase, calculated as (8.7 − 7)/7 × 100% = 24%. The increase is primarily due to the use of a private blockchain environment and optimized smart contract design. There were many reasons for this increase. The most important reason is that the Ethereum platform sets the corresponding block for each user separately, and the user’s operations are performed in this block. At the same time, the code for smart contract development should be as concise as possible to maximize the speed. Occasionally, in real transactions, information on the actual buying and selling of houses may be released after a long time. In this case, the throughput and latency are negligible.

It should be noted that the performance results observed (e.g., 3-s response time) are based on a Ganache local environment, which simulates a private or alliance blockchain. Therefore, the results reflect an idealized development setting with minimal network delay and isolated traffic. If deployed on the public Ethereum mainnet, network congestion, gas fees, and node distribution could significantly affect performance. In such settings, transaction confirmation times may be longer, and system throughput could be constrained by global consensus protocols. Future work will explore deployment on public or hybrid chains and evaluate system scalability under real-world loads.

5. Discussion

The innovation of SHHOTF is primarily reflected in the following three aspects:

- (1)

- A number of researchers in the construction industry usually store and trade the data of all participants in a blockchain, increasing the operational burden. This paper proposed a logic flow chart for second-hand housing trading based on smart contracts for three processes: modifying housing information, transactions, and false housing information complaints. The flow chart (1) meets the requirements of all steps in second-hand housing transactions and (2) protects the privacy and security of buyers and sellers. Specifically, it enables the sources of false housing information to be traced and guarantees the authenticity of the information.

- (2)

- After a series of analyses and tests, SHHOTF demonstrated that it meets the general business process requirements and can increase the transaction speed by 24% compared to the traditional Ethereum public network. This confirms that the blockchain technology possesses the properties of both traceability and high transaction speed. At the same time, the framework ensures the authenticity of information through the use of a weak intermediary, an approach which can reduce the cost for buyers and sellers by 5% [66].

- (3)

- From a theoretical perspective, this research contributes to the emerging literature on blockchain applications in the architecture, engineering, construction, and operation (AECO) industry by presenting a structured and tested framework (SHHOTF) specifically tailored for second-hand housing transactions—a relatively underexplored domain. Unlike prior studies that discuss blockchain in general real estate or supply chain contexts, this study integrates smart contracts, data model design, and case-based evaluation, offering a replicable model for other domains with similar trust and transparency challenges.

- (4)

- From a practical standpoint, the development and testing of SHHOTF demonstrate that blockchain can meaningfully reduce transaction time (by 24%) and improve data traceability and false information handling. These improvements are particularly relevant in markets with high information asymmetry and low regulatory enforcement. The modularity of the smart contract design also allows for adaptation to different legal and business environments, enhancing the framework’s global applicability. However, the reliance on a private chain (Ganache) highlights the need for further exploration of scalability and performance under public or hybrid blockchain deployments, which will be addressed in future research.

- (5)

- While blockchain offers pseudonymity and strong privacy protection, this can pose challenges in real estate transactions where identity verification and asset authenticity are critical. To mitigate the risks of identity fraud or misuse of deepfake technologies, our framework incorporates off-chain real-name authentication during account registration, supported by government-issued ID verification. Additionally, the authenticity of housing information is ensured through a multi-step validation mechanism, including blockchain-stored hashes and manual review layers for flagged complaints. Future versions of the framework may integrate Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) or decentralized identity (DID) systems to further enhance both privacy and trust. These measures aim to proactively protect users from cybercriminals while preserving decentralization and transparency.

- (6)

- In addition to benefits for buyers and sellers, the proposed SHHOTF also offers potential value to credit institutions such as banks and mortgage providers. The immutable transaction records stored on the blockchain can serve as reliable evidence of ownership history, transaction legitimacy, and asset condition—factors that are essential for loan risk assessment. Moreover, the automated smart contracts can integrate conditional logic to release ownership or funds only after loan approval or insurance confirmation, thus reducing fraud and enhancing trust. By incorporating these features, the system can support safer, faster, and more transparent mortgage-backed transactions, which may reduce administrative costs and improve regulatory compliance for financial institutions.

6. Conclusions

Economic problems, such as information asymmetry, and legal problems, such as skipping orders, exist in second-hand housing transactions. However, the existing literature does not comprehensively review the problems of second-hand housing transactions and propose effective solutions. To fill this research gap, we conducted a comprehensive literature review to determine the suitability of second-hand housing transactions and blockchain trading frameworks.

The major contributions of this paper are summarized as follows. First, we determined the content of expert interviews through literature review and classified the interview manuscripts to determine the framework requirements. The requirements have the characteristics of a bilateral market, meeting the needs of both buyers and sellers. Second, we proposed the functional module of a framework based on the blockchain and designed a complete business process. Third, we developed an architecture for integrating blockchain and second-hand housing transaction processes and developed technical components that support the framework functions. The framework not only ensures the confidentiality of sensitive data, but also strengthens the relationship between relevant users. Fourth, a practical case in Britain is used as an example to demonstrate the effectiveness and innovation of the framework in this paper. The experimental results show that it can improve the transaction speed by 24%, and the cost is acceptable compared with the mainstream platforms.

This study solves the most important difficulty in the development of SHHOTF. However, there are many deficiencies in this study, and many aspects need to be further explored. First, this study only evaluates the performance of blockchain technology (such as throughput and scalability) for the Ethereum platform, which verifies the effectiveness of Ethereum alliance chain platform but does not verify the security and privacy of the platform and does not make a quantitative comparison with other blockchain development platforms (such as Hyperledger Fabric). Future research can be based on application scenarios in different countries and compared with other different blockchain networks. In addition, the implementation of the SHHOTF platform must operate within the legal frameworks of each country. While some jurisdictions support blockchain-based records and digital signatures, the legal recognition of smart contracts and decentralized transactions is still evolving. Therefore, future deployment of the platform may require further regulatory support or legal adaptation, particularly in areas such as data privacy, identity verification, and digital contract enforcement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-H.L., Z.H. and J.Z.; Methodology, Z.H. and J.Z.; Software, H.L.; Validation, J.Z.; Resources, X.T. and J.C.P.C.; Writing—original draft, Z.H. and J.Z.; Visualization, X.T. and J.C.P.C.; Supervision, Y.-H.L. and J.Z.; Project administration, Y.-H.L. and H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NBoS. Share of Second-Hand Housing in China, National Bureau of Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/english/easyquery.htm?cn=A01 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. China Housing Development Report (2020–2021), n.d. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1686740835698737420&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Agarwal, S.; He, J.; Sing, T.F.; Song, C. Do real estate agents have information advantages in housing markets? J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 134, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R. Organising the unorganised: Role of platform intermediaries in the Indian real estate market. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2017, 29, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liang, P.; Gao, N. Can higher levels of disclosure bring greater efficiency: Empirical research on the effect of government information disclosure on enterprise investment efficiency. China Econ. Q. Int. 2021, 1, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. Does Information Asymmetry Impede Market Efficiency? Evidence from Analyst Coverage. J. Bank. Financ. 2020, 118, 105856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalberts, R.; Townsend, A. Real Estate Transactions, the Internet and Personal Jurisdiction. J. Real Estate Lit. 2002, 10, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianjia. Lianjia Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://bj.lianjia.com/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Zillow. Zillow Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.zillow.com/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Trustpilot. Trustpilot Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.trustpilot.com/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Li, V. Challenge of disintermediation to the information service of brokers in the second-hand house market. J. Tsinghua Univ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 57, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Bjork, P. Sources of distrust: Airbnb guests’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Teruel, R.M. A legal approach to real estate crowdfunding platforms. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2019, 35, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukissas, Y. All the Homes: Zillow and the Operational Context of Data. Transform. Digit. Worlds Iconference 2018, 10766, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Thaheem, M.J.; Wang, C.C.; Imran, M. It’s all about perceptions: A DEMATEL approach to exploring user perceptions of real estate online platforms. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 4297–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, R.; Lu, W.; Xue, F. Two-layer Adaptive Blockchain-based Supervision model for off-site modular housing production. Comput. Ind. 2021, 128, 103437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Mukkamala, R.R.; Vatrapu, R.; Ordieres-Mere, J. Blockchain-based Personal Health Data Sharing System Using Cloud Storage. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on E-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom), Ostrava, Czech Republic, 17–20 September 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Barenji, A.V.; Li, Z.; Montreuil, B.; Huang, G.Q. Blockchain-based smart tracking and tracing platform for drug supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ableitner, L.; Tiefenbeck, V.; Meeuw, A.; Wörner, A.; Fleisch, E.; Wortmann, F. User behavior in a real-world peer-to-peer electricity market. Appl. Energy 2020, 270, 115061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, P.V.R.P.; Jauhar, S.K.; Ramkumar, M.; Pratap, S. Procurement, traceability and advance cash credit payment transactions in supply chain using blockchain smart contracts. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 167, 108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Li, X.; Xue, F.; Zhao, R.; Wu, L.; Yeh, A.G.O. Exploring smart construction objects as blockchain oracles in construction supply chain management. Autom. Constr. 2021, 129, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wakefield, R.; Lyu, S.; Jayasuriya, S.; Han, F.; Yi, X.; Yang, X.; Amarasinghe, G.; Chen, S. Public and private blockchain in construction business process and information integration. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saull, A.; Baum, A.; Braesemann, F. Can digital technologies speed up real estate transactions? J. Prop. Investig. Financ. 2020, 38, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, S.; Bodkhe, U.; Alshehri, M.D.; Gupta, R.; Sharma, R. Blockchain-assisted industrial automation beyond 5G networks. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenham, J. A trading agent for a multi-issue clearing house. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Innovative Techniques and Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Cambridge, UK, 12–14 December 2006; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.M. Motives for participation in Internet innovation intermediary platforms. Inf. Process. Manag. 2013, 49, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letgo. Letgo Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.letgo.com/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Seiler, M. The Effects of Time Constraints on Broker Behavior in China’s Resale Housing Market: Theory and Evidence. Int. Real Estate Rev. 2016, 19, 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.R. The Development Force of S&T Intermediary in Traditional Industrial Clusters. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Public Administration, Chengdu, China, 23–25 October 2009; pp. 1033–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, D.L.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Liu, S.D.; Li, Y.P.; Deng, N. Data Authenticity Analysis for Online O2O Data: A Case Study of Second-Hand Houses Posting Data. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Broadband Wireless Computing, Communication and Applications (BWCCA), Tottori, Japan, 28–30 October 2020; Volume 97, pp. 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Li, X.; Kamoche, K. Transforming From Traditional To E-intermediary: A Resource Orchestration Perspective. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2021, 25, 338–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.A.; Bosman, L.B.; Wollega, E.; Leon-Salas, W.D. Peer-to-peer energy trading: A review of the literature. Appl. Energy 2021, 283, 116268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Teruel, R.M. Legal challenges and opportunities of blockchain technology in the real estate sector. J. Prop. Plan. Environ. Law 2020, 12, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Jindal, R.; Borah, M.D. A review of smart contract-based platforms, applications, and challenges. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Al-Turjman, F. A conceptual framework for blockchain smart contract adoption to manage real estate deals in smart cities. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 5033–5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, W.; Wang, M. Research on the scope definition and market segmentation of real estate network platform. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2018, 4, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Berdik, D.; Otoum, S.; Schmidt, N.; Porter, D.; Jararweh, Y. A Survey on Blockchain for Information Systems Management and Security. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawari, N.O.; Ravindran, S. Blockchain and the built environment: Potentials and limitations. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-F.; Chang, K.-C.; Huang, T.-H.; Lin, W.-Y. Blockchain-driven framework for financing credit in small and medium-sized real estate enterprises. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 201–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lisi, A.; De Salve, A.; Mori, P.; Ricci, L.; Fabrizi, S. Rewarding reviews with tokens: An Ethereum-based approach. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 120, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, K.; Rehman, M.H.U.; Nizamuddin, N.; Al-Fuqaha, A. Blockchain for AI: Review and open research challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 10127–10149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. The blockchain: State-of-the-art and research challenges. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2019, 15, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, M.; Božić, N.; Pujolle, G.; Secci, S. A Vademecum on Blockchain Technologies: When, Which, and How. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 3796–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldweesh, A.; Alharby, M.; Mehrnezhad, M.; van Moorsel, A. The OpBench Ethereum opcode benchmark framework: Design, implementation, validation and experiments. Perform. Eval. 2021, 146, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, A.; Nowostawski, M. Security Vulnerabilities in Ethereum Smart Contracts. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July–3 August 2018; pp. 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Molisch, A.F.; Sastry, N.; Raman, A. Individual Preference Probability Modeling and Parameterization for Video Content in Wireless Caching Networks. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2019, 27, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chong, H.Y.; Chi, M. Blockchain in the AECO industry: Current status, key topics, and future research agenda. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Nanayakkara, S.; Rodrigo, M.N.N.; Senaratne, S.; Weinand, R. Blockchain technology: Is it hype or real in the construction industry? J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 17, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akanbi, L.; Ajayi, A.; Delgado, J.M.D.; Bilal, M.; Akinade, O.O.; Ahmed, A. Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A review of present status, opportunities and future challenges. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorov, S.I. Digital Transformation of Capital Market Infrastructure. Ekon. Polit. 2020, 15, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Alqarni, M.A.; Almazroi, A.A.; Alam, L. Real estate management via a decentralized blockchain platform. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2020, 66, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Q.; Sun, G.; Luo, L.; Cao, H.L.; Yu, H.F.; Vasilakos, A.V. Latency performance modeling and analysis for hyperledger fabric blockchain network. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Huh, J.-H. Autochain platform: Expert automatic algorithm Blockchain technology for house rental dApp image application model. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2020, 2020, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y. An integrated framework for blockchain-enabled supply chain trust management towards smart manufacturing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rightmove. Rightmove Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.rightmove.co.uk/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Opendoor. Opendoor Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.opendoor.com/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Hallowell, M.R.; Gambatese, J.A. Qualitative Research: Application of the Delphi Method to CEM Research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wu, L.; Xu, J.; Lou, J. Construction E-Inspection 2.0 in the COVID-19 Pandemic Era: A Blockchain-Based Technical Solution. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.G.; Alhomoud, A.; Wills, G. A Framework of the Critical Factors for Healthcare Providers to Share Data Securely Using Blockchain. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 41064–41077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Das, M.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.C.P. Automation in Construction Distributed common data environment using blockchain and Interplanetary File System for secure BIM-based collaborative design. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Fan, L.; Liu, C. Manufacturing system under I4.0 workshop based on blockchain: Research on architecture, operation mechanism and key technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Tao, X.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.C.P. A blockchain-based integrated document management framework for construction applications. Autom. Constr. 2022, 133, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakurthi, V.; Manupati, V.K.; Machado, J.; Varela, L.; Babu, S. An innovative approach for resource sharing and scheduling in a sustainable distributed manufacturing system. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 52, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkhe, U.; Tanwar, S.; Parekh, K.; Khanpara, P.; Tyagi, S.; Kumar, N.; Alazab, M. Blockchain for Industry 4.0: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 79764–79800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marridi, A.Z.; Mohamed, A.; Erbad, A. Reinforcement learning approaches for efficient and secure blockchain-powered smart health systems. Comput. Netw. 2021, 197, 108279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldBank. Doing Business 2018: Reforming to Create Jobs. 2018. Available online: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/registering-property (accessed on 11 April 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).