1. Introduction

The acceleration of the global urbanization process led to a sustained growth in the demand for concrete in infrastructure construction. Consequently, a series of resource and environmental issues arose, like the overharvesting of natural sand and gravel aggregates and the buildup of construction waste [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Against this backdrop, the preparation of concrete using desert sand and recycled construction aggregates offered an effective means of achieving the sustainable development of building materials. This approach not only alleviated the pressure of natural aggregate resource shortages but also contributed to reducing construction waste accumulation and land desertification, thereby demonstrating significant ecological and economic benefits [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

However, the durability performance of desert sand recycled aggregate concrete (DSRAC) in cold regions, particularly its freeze–thaw resistance, confronted formidable challenges. The inherent pores and microcracks within the concrete deteriorated significantly under the action of freeze–thaw cycles. The stress generated by the repeated freezing and expansion of pore water caused microcracks to propagate from the surface into the interior, ultimately resulting in macroscopic cracking, spalling and even structural failure [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. It is important to note that the long-term durability degradation of fiber-reinforced concrete under diverse severe service conditions represents a pervasive core challenge in the field. Cascardi et al. [

21] demonstrated that alkaline exposure significantly weakens the interfacial bond between glass fibers and the cementitious matrix, resulting in a time-dependent decline in the constraint efficacy of fiber-reinforced composites. This further underscores the criticality of in-depth investigations into fiber–matrix interface damage mechanisms under specific environmental conditions, such as the freeze–thaw cycling addressed in this study, for ensuring the long-term structural integrity of fiber-reinforced concrete structures.

To enhance the freeze–thaw resistance of DSRAC, scholars explored various modification methods. Regarding fiber reinforcement, which was highly effective in inhibiting crack propagation, Ye et al. [

22] verified that adding 0.15–0.20% basalt fibers notably enhanced the material’s overall performance under wind–sand erosion and salt–freeze cycles. The use of hybrid fibers was particularly promising due to the potential for synergistic effects; for instance, steel fibers excelled at bridging macro-cracks, while finer polymer fibers could control microcrack initiation. However, most existing research was limited to a single type of fiber. Separately, extensive research was conducted on the utilization of desert sand. At the macroscopic level, Zhang et al. [

23] discovered through coupled experiments of chloride salt attack and freeze–thaw cycling that concrete with a 100% desert sand replacement rate exhibited superior performance compared to ordinary concrete after 200 cycles. Gong et al. [

24,

25] employed the Weibull distribution model to predict the freeze–thaw resistance life of desert sand concrete and identified that the optimal replacement rate range was 25–40%. Li et al. [

26] examined the durability performance of aeolian sand concrete under the combined effect of carbonation and freeze–thaw cycling and developed a damage equation based on a parabolic model. Ji et al. [

27] explored the impact of the combined application of recycled rubber and desert sand on the mechanical properties of concrete. At the microscopic scale, Luo et al. [

28] confirmed that a 30% desert sand substitution ratio optimized the pore structure and reduced microcracks, and proposed a damage index based on fractal dimension. Yang et al. [

29] revealed that 50% desert sand effectively suppressed the formation of gypsum and ettringite in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) in a salt–freeze environment, enhancing its microscopic hardness and density. Bai et al. [

30] developed a freeze–thaw damage degradation model linking macroscopic and microscopic perspectives, based on irreversible energy dissipation. Dong et al. [

31] examined the capillary water absorption properties under the combined effect of a sulfate attack and freeze–thaw cycling via fractal theory. Wang et al. [

32] explored the freeze–thaw resistance of desert sand in 3D-printed concrete.

Our previous research [

33] systematically explored the mechanical performance of steel–hybrid PP fiber-reinforced DSRAC at an ambient temperature and determined that a 30% desert sand replacement rate and a hybrid combination of 0.15% hybrid PP fibers and 0.5% steel fibers (F0.15-S0.5) were the optimal parameters. However, this work had notable limitations. Firstly, the research was confined to a static normal-temperature environment, failing to unveil the performance degradation and damage evolution of the material under freeze–thaw cycles. Secondly, no quantitative damage model was established, making it challenging to support the durability design of structures in cold regions. Thirdly, the 30% desert sand replacement rate was optimized solely based on normal-temperature strength, and its durability performance under freeze–thaw conditions remained to be verified. These limitations, together with the inadequacies of the aforementioned single-fiber studies, collectively constituted the crucial research gaps in the current context.

Nevertheless, the utilization of desert sand was not a straightforward one-to-one substitution. Its ultra-fine particle size and relatively smooth surface morphology introduced distinct microstructural effects and interfacial challenges to concrete [

34]. On one hand, fine particles might exert a positive micro-filling effect, refining the matrix pore structure; on the other hand, their high specific surface area could increase water demand or impair workability, while the smooth surface might weaken the chemo-mechanical bonding with cement paste, reducing the inherent strength of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). In fiber-reinforced systems, the interplay between the weakening of the matrix’s native ITZ and the performance of the fiber–matrix interface emerged as a critical yet unresolved scientific issue [

35,

36]. Notably, in freeze–thaw environments, water migration was highly dependent on the material’s pore structure and interfacial defects [

20]. Thus, the incorporation of desert sand might either improve the baseline freeze–thaw resistance by refining pores or exacerbate the accumulation of frost damage by introducing additional weak interfaces. The core challenge for enhancing the durability of desert sand recycled concrete was how to leverage the benefits while mitigating the drawbacks of desert sand via fiber reinforcement in such a complex interfacial matrix. Based on the above analysis, this study posited that simply optimizing the desert sand replacement ratio might be insufficient to offset the interfacial disadvantages it introduced. Fiber reinforcement, particularly hybrid fiber strategies, offered a viable pathway for actively regulating and strengthening this fragile system. Investigating whether and how hybrid fibers could overcome or compensate for interfacial defects induced by desert sand characteristics, thereby enhancing freeze–thaw durability, was one of the core mechanistic questions this study sought to address.

Extensive studies have confirmed that the composite incorporation of rigid fibers (e.g., steel fibers) and flexible fibers (e.g., polypropylene fibers, basalt fibers, PVA fibers) into concrete yielded significant synergistic effects. The general mechanism was as follows: rigid fibers could effectively bridge and constrain the propagation of macroscopic cracks, providing post-peak load-bearing capacity; flexible fibers, by contrast, could disperse stress, inhibit the initiation of microcracks and enhance matrix toughness. However, the existing research on hybrid fiber’s synergistic effects had predominantly focused on ordinary aggregate concrete or systems with specific single alternative materials. Concrete prepared from the complex multiphase system integrating desert sand (ultra-fine particles) and recycled coarse aggregates (coated with old mortar) exhibited numerous internal interfaces and defects, resulting in inherently poor freeze–thaw resistance. For such a fragile matrix, the following questions remained unsystematically addressed: whether the aforementioned synergistic enhancement principle still held; how to quantitatively characterize its enhancement efficiency; and what the specific mechanisms were by which fibers inhibited the freeze–thaw damage process. Therefore, to address this gap, this study systematically investigates the damage mechanism of hybrid-fiber-reinforced DSRAC under freeze–thaw cycles, based on the aforementioned optimal mix proportion. The specific research objectives are outlined below:

- (1)

Evaluate and compare the freeze–thaw resistance of DSRAC with hybrid fibers against plain and single-fiber-reinforced counterparts, based on macroscopic performance indicators;

- (2)

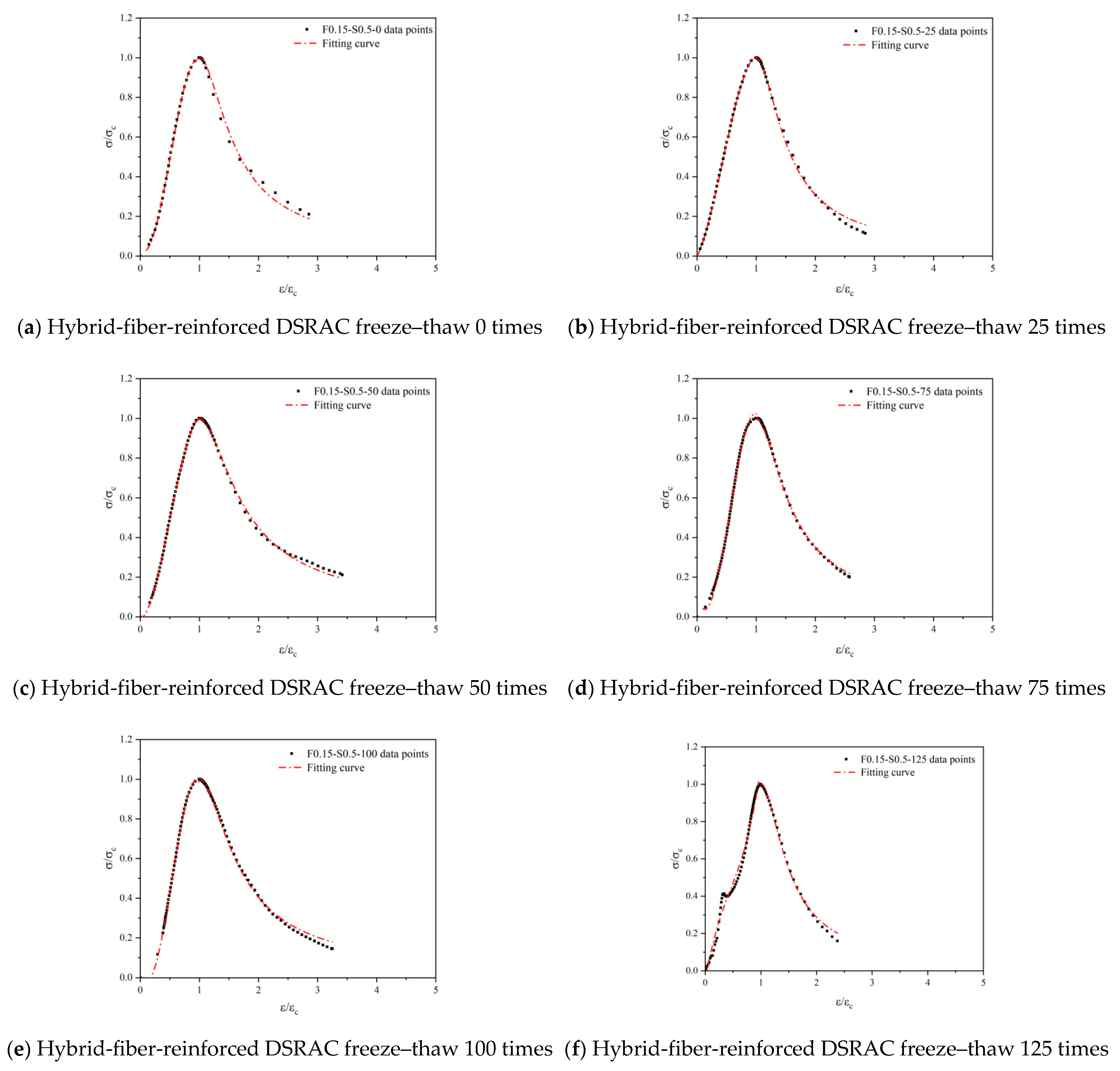

Establish freeze–thaw damage models built upon the exponential function and Aas-Jakobsen function, and characterize the stress–strain relationship evolution using Guo’s constitutive model;

- (3)

Reveal the toughening and crack-arresting mechanisms of fibers at the microscopic scale. This work aims to provide a crucial theoretical basis and practical guidance for the engineering application of fiber-reinforced DSRAC in cold regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

The basic materials used in this research included P·O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement, 5–20 mm recycled coarse aggregates, sand from the Taklimakan Desert in Xinjiang, wave-milled steel fibers and hybrid PP fibers. Specifically, the cement met the requirements of ASTM C150 [

37] for ordinary Portland cement. The chemical composition is presented in

Table 1, below. To clearly demonstrate the crucial performance indicators of the materials employed in this research, their main physical and mechanical properties were systematically collated and summarized, as presented in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4. For a more in-depth exploration of the parameters, interested readers were referred to our previously published work [

33]. The synthetic fiber employed in this study was a blend of twisted-bundle macro-synthetic fibers and fibrillated polypropylene fibers, which were primarily composed of virgin copolymer and polypropylene. This fiber was designed to integrate the macroscopic bridging effect of coarse fibers and the microcrack-inhibiting capacity of fine fibers. For brevity in subsequent sections, it was abbreviated as “hybrid PP fibers”.

As presented in

Table 2, the chemical composition of the employed desert sand is dominated by SiO

2, with notably high contents of CaO and Al

2O

3. This compositional characteristic implies potential pozzolanic activity [

38]. While the present study primarily focuses on its macroscopic effects as an aggregate, its chemical properties are recognized as a critical context for subsequent in-depth investigation of microscale mechanisms.

2.2. Mix Design

The mix-proportion design of this study was founded upon the systematic parametric research that was previously published by the author’s research group [

33]. In that earlier investigation, we systematically explored the impacts of various desert–sand replacement ratios (0%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 100%) and different fiber dosages (both single-fiber and hybrid-fiber configurations) on the mechanical properties of desert–sand recycled–aggregate concrete (DSRAC) at a normal temperature. The findings of this research clearly demonstrated that when 30% of the sand was replaced with desert sand, the concrete manifested the optimal baseline mechanical properties. Additionally, the group with hybrid fibers F0.15-S0.5 (comprising 0.15% hybrid PP fibers and 0.5% steel fibers) exhibited a significantly more pronounced reinforcement effect compared to any single-fiber type or other dosage combinations.

Consequently, the objective of this study was not to reiterate the parameter screening process but rather to conduct an in-depth exploration of the damage mechanism and performance evolution patterns of this material system under freeze–thaw cycles, building upon the optimally determined benchmarks from the previous research. Based on this premise, the experimental design of this study was characterized by a distinct focus and logical structure.

To accurately assess the sensitivity of the freeze–thaw performance to fluctuations in the desert–sand content around the pre-determined optimal value of 30%, we established three replacement ratio groups with 25%, 30% and 35% replacement levels. This approach, in contrast to including a group with a 0% replacement ratio (DS0), was more effective in uncovering the internal performance change patterns within the DSRAC system and precisely identifying the optimal desert–sand dosage under freeze–thaw conditions.

To directly evaluate the degree of improvement in the freeze–thaw durability and the underlying synergy mechanism upon the introduction of the optimal fiber combination into the pre-determined optimal matrix (DS30), we retained only the most effective hybrid-fiber group, F0.15-S0.5. This decision was made with the intention of emphasizing the verification of the effectiveness of this optimal combination in durability-related scenarios, rather than re-validating the already-established effects of single fibers.

In conclusion, the four mix-proportion designs in this study (DS25, DS30, DS35, F0.15-S0.5) were capable of effectively addressing the following core scientific inquiries: (1) Did the optimal desert–sand dosage remain optimal under freeze–thaw conditions? (2) Could the optimal fiber combination effectively enhance the durability of the optimal matrix in freeze–thaw environments? This focused experimental design enabled a more profound research approach and led to more conclusive and distinct findings. The experimental mix proportions are listed in

Table 5.

Given that the specific gravity of the employed hybrid PP fibers (0.91) was lower than that of water, a standardized mixing protocol was implemented in this study to prevent fiber floating and segregation during mixing, as well as to ensure uniform fiber dispersion within the concrete matrix. The protocol was specified as follows: a forced-action mixer was utilized; feeding sequence: all dry ingredients (cement, sand, desert sand, recycled coarse aggregate) were first introduced into the mixer and dry-mixed for 60 s to achieve homogeneous blending; approximately 80% of the mixing water was then added, followed by wet-mixing for 90 s; hybrid PP fibers and steel fibers were uniformly dispersed and sprinkled into the mixer, with mixing being continued for 60 s; finally, the remaining 20% of the mixing water (intended to rinse fibers adhering to the mixing blades and drum inner walls) was added, and mixing was prolonged for 120 s until a homogeneous mixture free of fiber agglomeration was obtained. The total duration of the mixing process was strictly controlled. Observations indicated that this protocol effectively mitigated fiber floating; the molded specimens exhibited a uniform appearance, with no evident fiber stratification or localized enrichment.

2.3. Specimen Preparation

This study followed the criteria outlined in the standard “GB/T 50082-2009” [

39]. The rapid freeze–thaw protocol was employed to perform freeze–thaw cycling tests on desert sand recycled aggregate concrete (DSRAC) specimens. The cycle counts were set to 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 125, respectively. After 24 days of standard curing, the specimens were extracted and soaked in 20 °C water for 4 days—during immersion, the water level was consistently kept 20–30 mm above the specimen top surface. At the 28-day curing age, the specimens were taken out of the water and their surface moisture was wiped dry. An ACS-30 electronic balance (precision: 0.1 g) was used to weigh the specimens. Meanwhile, a DT-20 dynamic elastic modulus tester was utilized to measure the specimens’ natural vibration frequency via the forced resonance method. Next, the specimens were placed into a TDR-3 rapid freeze–thaw testing device (

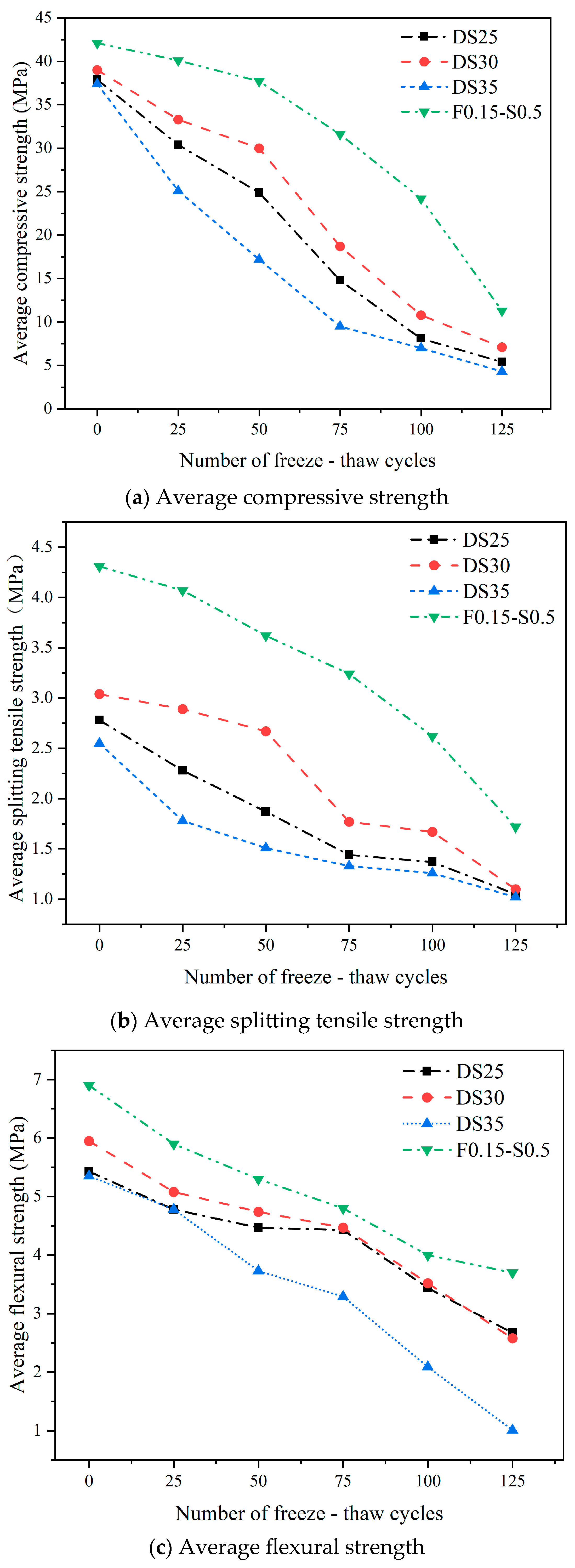

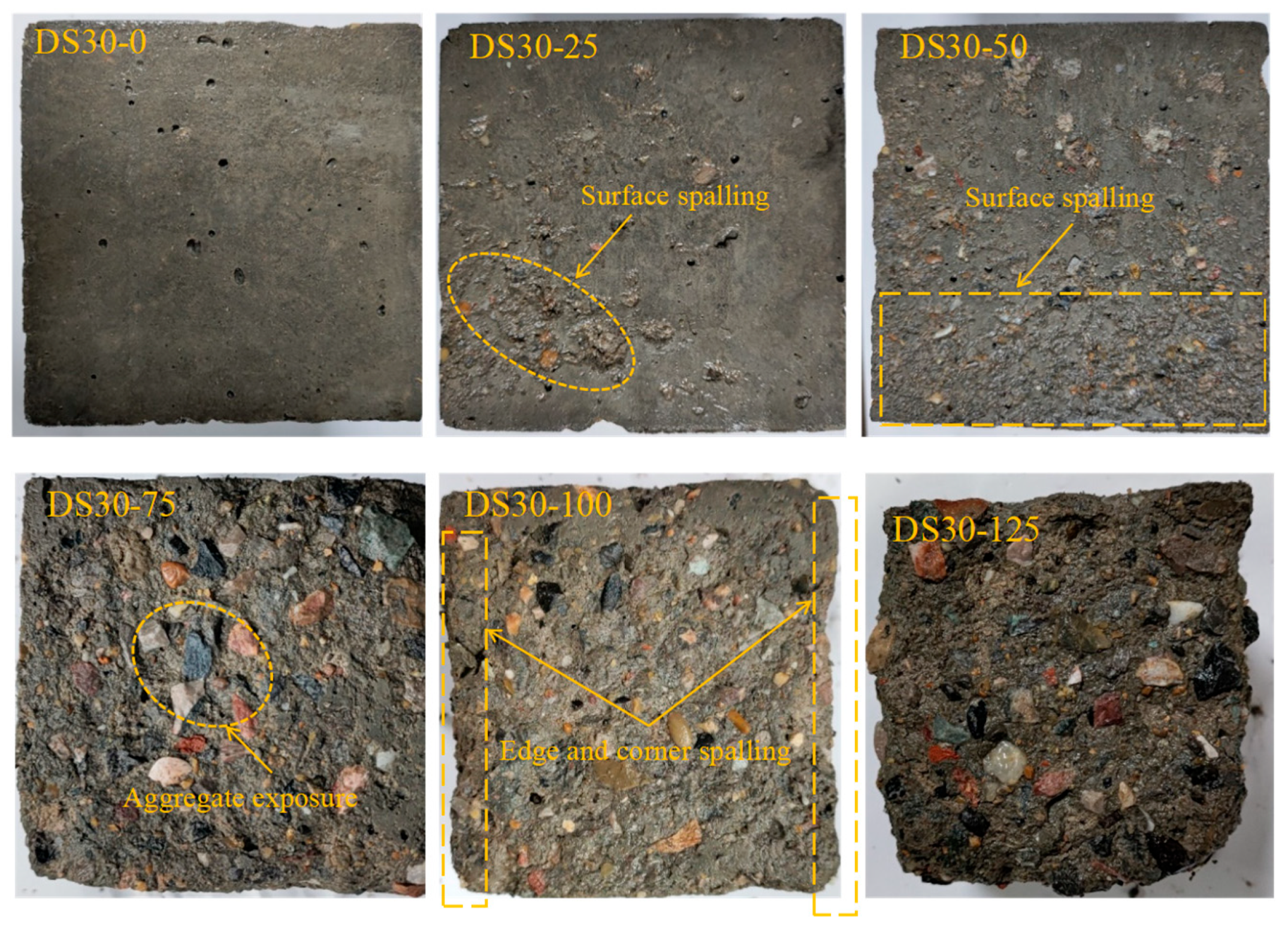

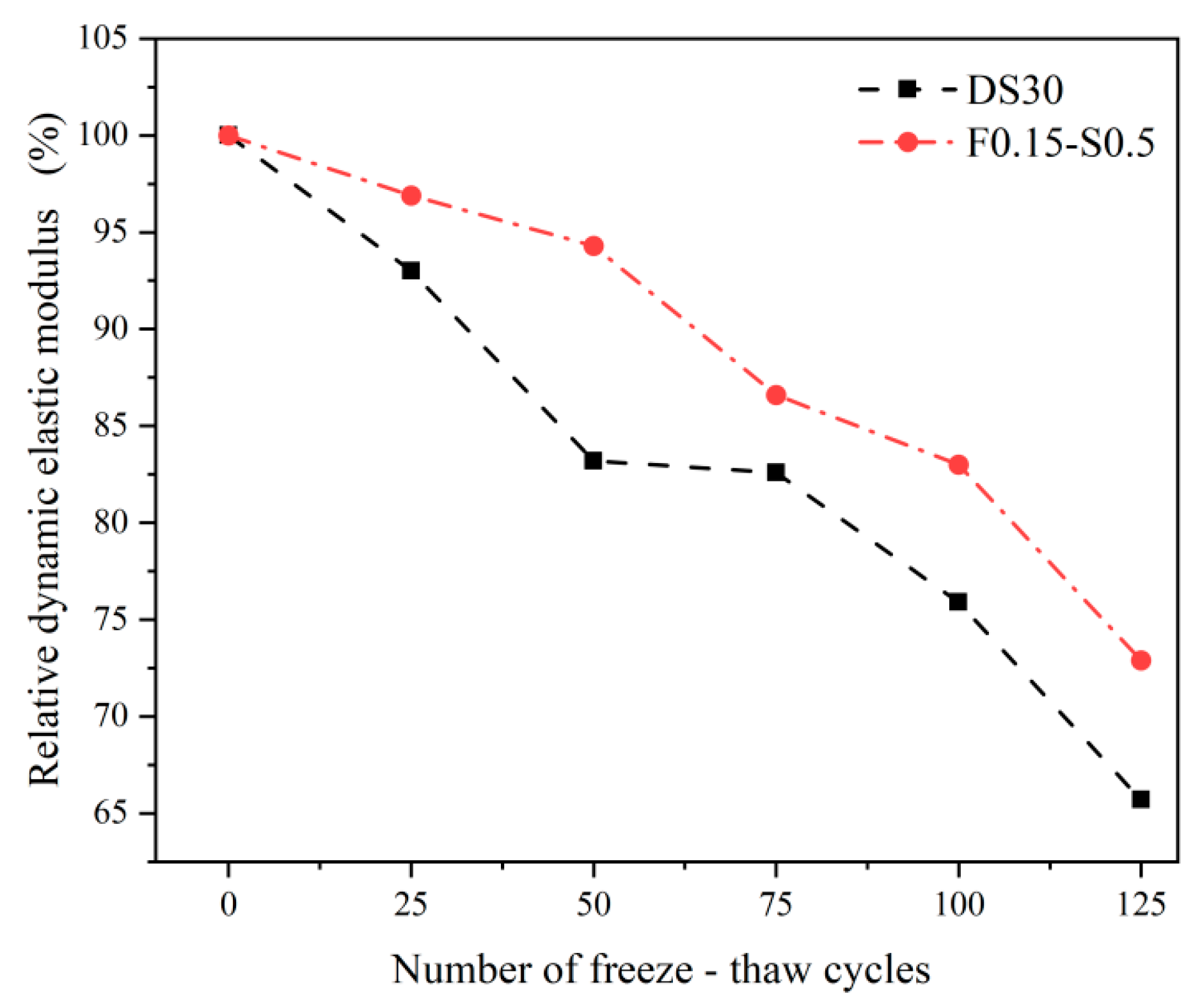

Figure 1) for cycling. Throughout the experiment, the core temperature was regulated to fluctuate between −17.0 °C ± 2.0 °C and 8.0 °C ± 2.0 °C. After every 25 freeze–thaw cycles, each group of specimens was tested for mass loss rate, dynamic elastic modulus, compressive strength, splitting tensile strength and flexural strength.

2.4. Test Methods

Following the guidelines of GB/T 50081-2019 [

39], this research utilized 100 × 100 × 100 mm cubic specimens for both the compressive strength and splitting tensile strength tests. For the flexural strength test, 100 × 100 × 400 mm prismatic specimens were used; the test loading rate, along with the mechanical property-testing instruments and loading setups, were consistent with the parameters employed in our team’s prior study [

33].

The mass loss rate calculation formula for DSRAC post-freeze–thaw cycles is given in Equation (1).

where

represents the mass loss rate of the i-th concrete specimen post N freeze–thaw cycles (%);

represents the initial mass of the i-th concrete specimen before freeze–thaw cycle testing (g); and

represents the post-N-freeze–thaw-cycle mass of the i-th concrete specimen (g).

The calculation methodology for the relative dynamic elastic modulus of desert sand recycled concrete following freeze–thaw cycles was presented as Equation (2) [

39].

In the equation: denotes the relative dynamic elastic modulus of the i-th concrete specimen post N freeze–thaw cycles; represents the transverse fundamental frequency (Hz) of the i-th concrete specimen post N freeze–thaw cycles; and represents the initial transverse fundamental frequency (Hz) of the i-th concrete specimen pre freeze–thaw cycle testing.

The relative dynamic elastic modulus calculation formula for desert sand recycled aggregate concrete (DSRAC) post-freeze–thaw cycles was provided in Equation (3) [

39].

where

f represents the natural vibration frequency (unit: Hz) and W denotes the specimen mass (unit: kg). Here, the subscript “0” indicates 0 freeze–thaw cycles and “n” denotes the freeze–thaw cycle count; L, b and h correspond to the specimen’s length, width and height, respectively (unit: mm); T is a size- and Poisson’s ratio-related correction factor for the specimen. According to the specification [

39], T took the value of 1.40.

2.5. Damage Model and Analytical Method

2.5.1. Exponential Function Freeze–Thaw Damage Model

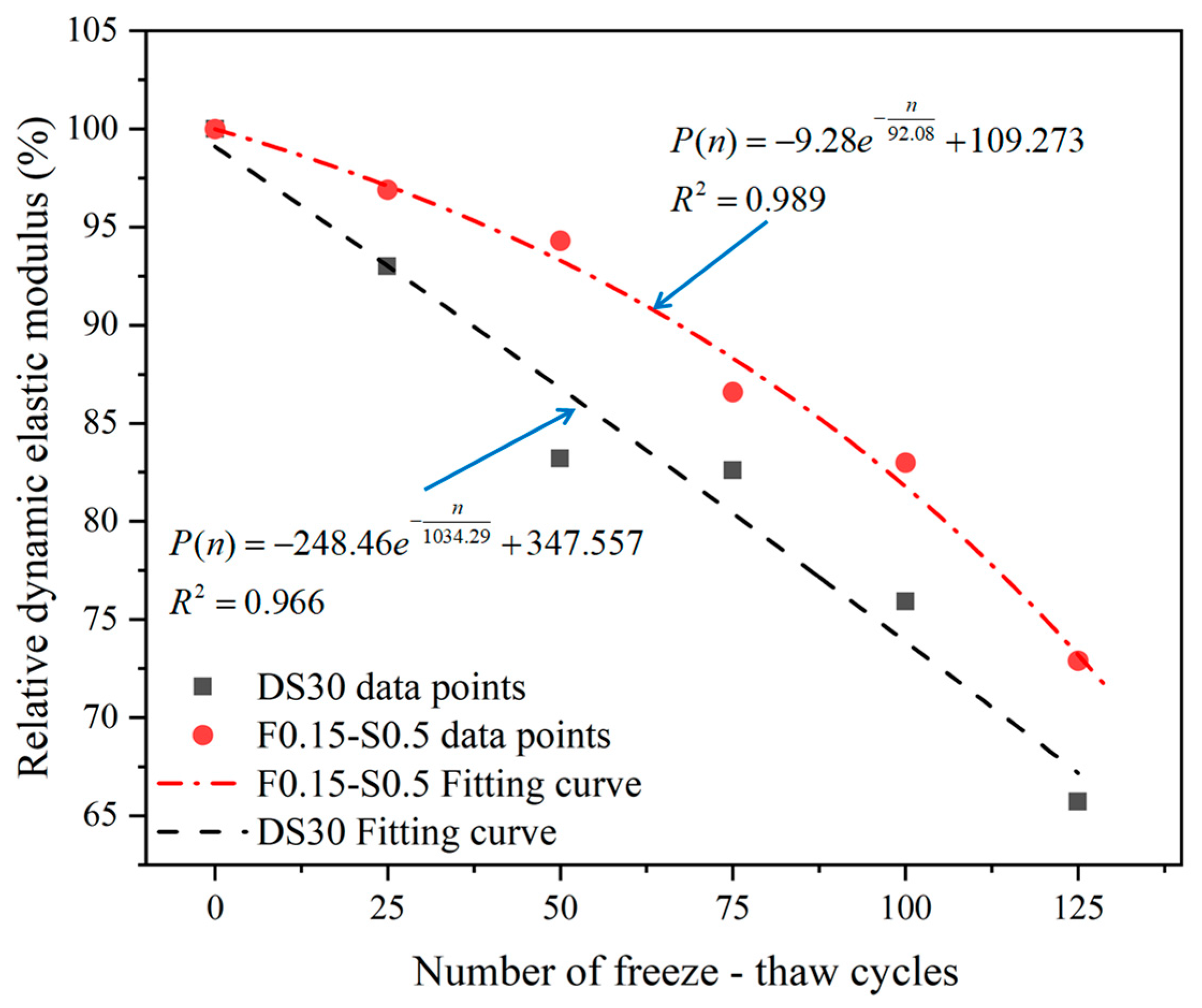

Through analysis of the relative dynamic elastic modulus variation pattern for hybrid-fiber-reinforced DSRAC specimens, it was found that the relative dynamic elastic modulus exhibited a decreasing trend as the number of freeze–thaw cycles increased and the curve exhibited certain non-linear characteristics. Therefore, an exponential decay function was employed to construct the freeze–thaw damage model. The specific formula was as shown in Equation (4).

where

P(n) represents the specimen’s relative dynamic elastic modulus post-n freeze–thaw cycles, in percentage (%) (dimensionless parameter, reflecting the integrity of the material internal structure after freeze–thaw); n represents the freeze–thaw cycle count, in cycle (experimental variable, with values of 0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125 cycles in this study); A represents the initial difference relative to the dynamic elastic modulus (when n = 0) and the final stable value, in percentage (%) (dimensionless parameter, reflecting the total attenuation amplitude of the material’s elastic modulus from the initial state to the stable state after late freeze–thaw); B represents the attenuation constant, in cycle (determining the rate at which the relative dynamic elastic modulus declines as the freeze–thaw cycle count increases; a higher B value denotes a slower attenuation rate and superior freeze–thaw resistance of the material); C represented the relative dynamic elastic modulus’ stable value in the late freeze–thaw cycle stage, in percentage (%) (dimensionless parameter, which reflects the lower limit of the relative dynamic elastic modulus when the material’s internal damage saturates, following repeated freeze–thaw cycles).

2.5.2. Aas-Jakobsen Freeze–Thaw Damage Model

Compared with other existing freeze–thaw damage models, such as the empirical models, probabilistic damage models and fatigue damage models proposed in previous studies [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47], the Aas-Jakobsen function model [

48] was a classic form of the freeze–thaw damage model. Its core concept is to characterize the evolution law of damage parameters with a freeze–thaw cycle count via a power–law relationship. Considering the characteristics of hybrid-fiber-reinforced DSRAC, by introducing influence parameters such as fiber type, dosage and recycled aggregate replacement rate, a non-linear correlation between the damage parameter and freeze–thaw cycle count was constructed. The model was shown in Equation (5), as follows.

In Equation (5), denoted the dynamic elastic modulus loss rate, n represented the freeze–thaw cycle count, n0 represented the characteristic number of cycles and m was the shape parameter.

2.5.3. Stress–Strain Constitutive Relationship

Prior to this, researchers worldwide had obtained extensive findings regarding the mathematical modeling of concrete’s uniaxial compressive stress–strain relationship under ambient temperature conditions. Representative models included those proposed by Hognestad, Guo and Saenz et al. [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Among these, the constitutive model developed by Guo [

49] gained the broadest applications. For the stress–strain relationship of recycled desert sand concrete, this characterization approach delivered higher precision and could more effectively capture the material’s actual mechanical behavior under diverse working conditions. Consequently, it offered a more robust foundation for assessing and forecasting the performance of hybrid-fiber-reinforced recycled DSRAC.

The detailed model expression was presented in Equation (6).

In the equation, , where represented the strain and represented the stress.

2.6. Microscopic Morphology Analysis

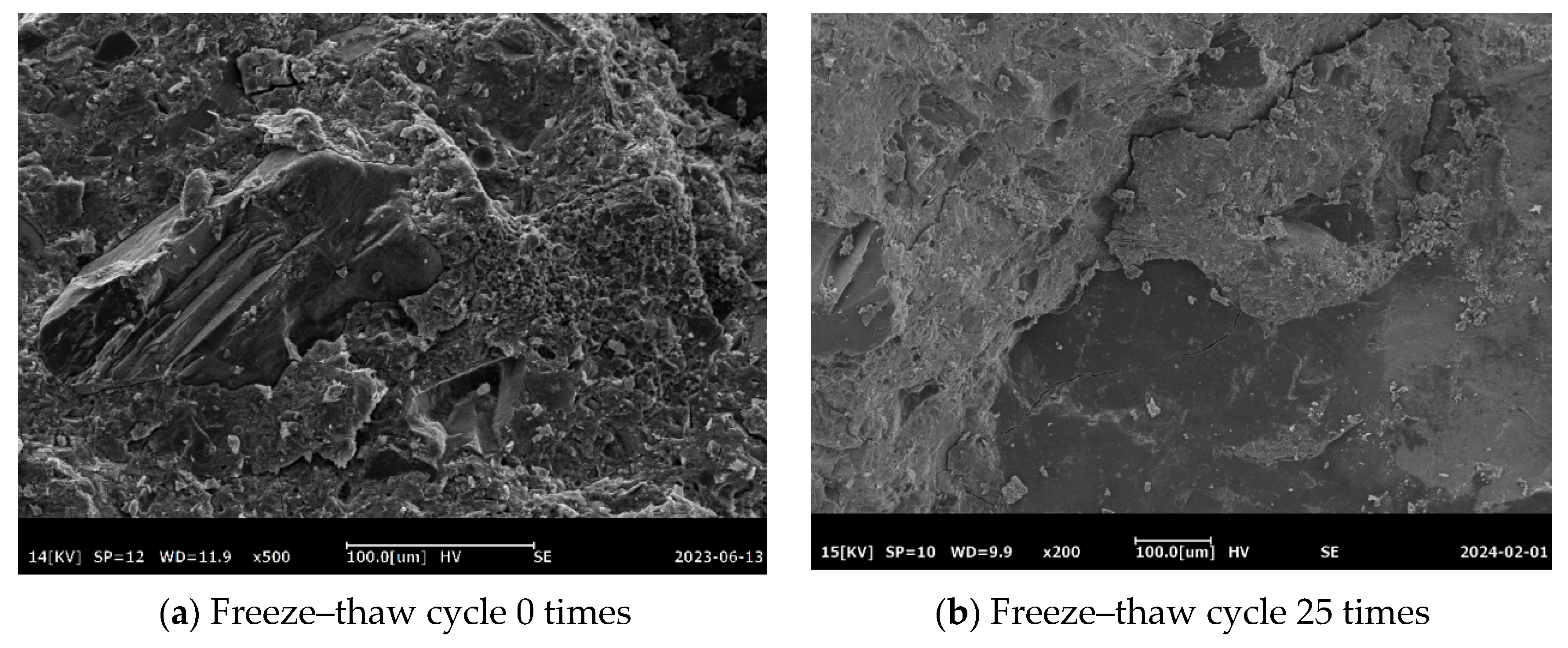

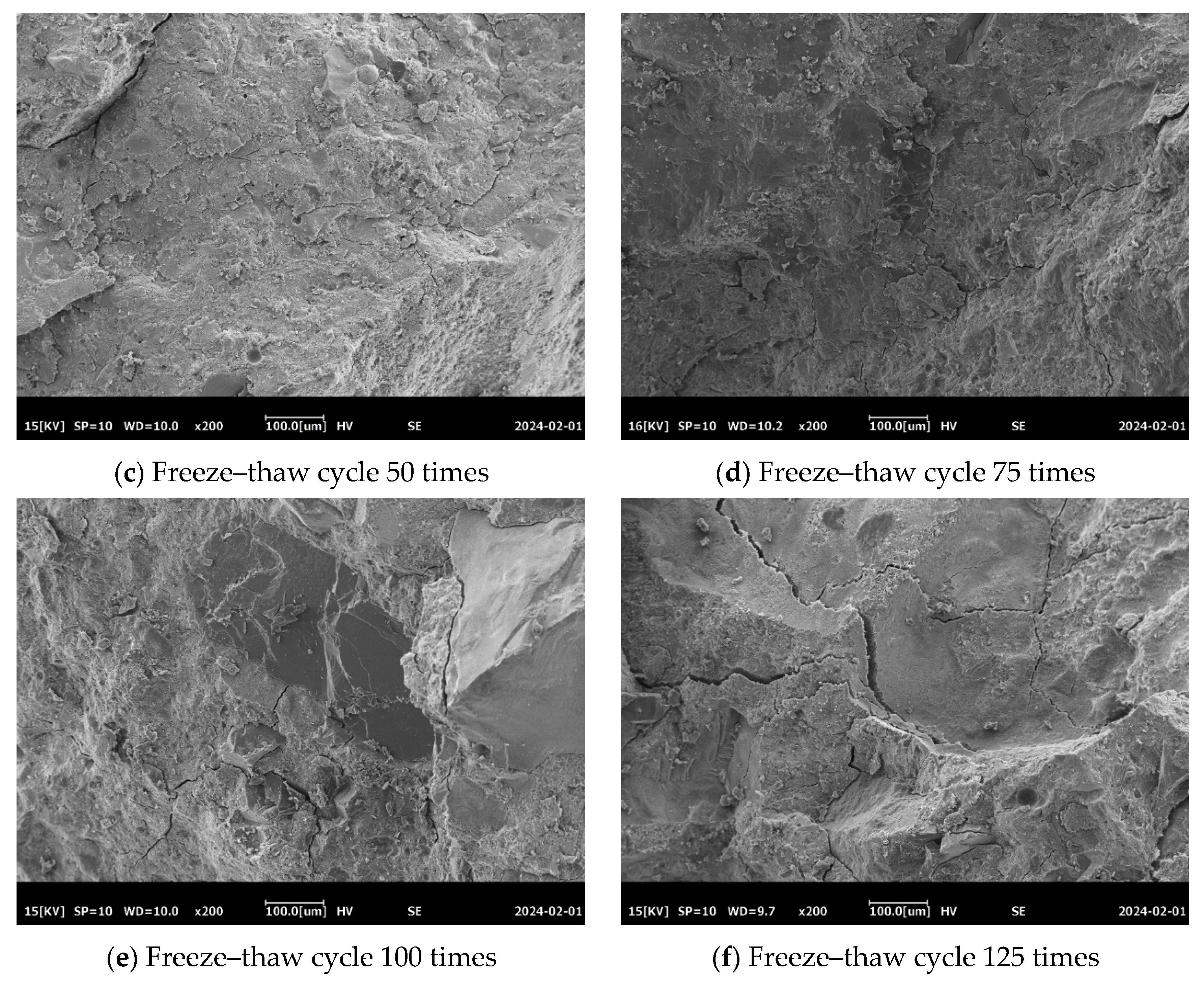

To explore the influence of freeze–thaw cycles on the microstructural characteristics of materials, this study employed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to perform micromorphological observations on the selected test specimens. The samples for SEM analysis were sourced from the inner core regions of the specimens following mechanical property tests. This approach was adopted to mitigate the influence of the cutting surface. The samples underwent a series of preparatory treatments, including drying and sputter coating with gold, before being positioned within the vacuum sample chamber. During SEM observation, the main accelerating voltage was adjusted to 15.0 kV, while the working distance was kept at roughly 15 mm. This study focused primarily on the microstructural evolution of the hybrid-fiber-reinforced group (F0.15-S0.5) under different freeze–thaw cycle counts (0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125 cycles). For the sample that had not undergone any freeze–thaw cycles (0 cycles), a magnification of 500× was employed to display the initial microstructure. For specimens that had undergone freeze–thaw cycles, all observations were performed at a consistent magnification of 200×. This standardization was implemented to guarantee the direct comparability of damage patterns across different freeze–thaw cycles.

4. Microscopic Research

Figure 12 displays scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrographs of hybrid-fiber-reinforced DSRAC after varying freeze–thaw cycle counts. From the perspective of microstructural evolution, it is clear that as the number of freeze–thaw cycles increases, the material undergoes a distinct degradation process. When the specimen had not experienced any freeze–thaw cycles (

Figure 12a), its microstructure was relatively compact, with a low porosity. The interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between cement paste and aggregates remained continuous and structurally intact, demonstrating an excellent initial condition. After 25 freeze–thaw cycles (

Figure 12b), microcracks started to emerge in the ITZ region, indicating that the freeze–thaw action had induced the initial damage. After 50 freeze–thaw cycles (

Figure 12c), these microcracks further propagated and interconnected. The porosity increased, and the continuity of the ITZ was disrupted, signifying a gradual accumulation of internal damage within the material. Upon reaching 75 freeze–thaw cycles (

Figure 12d), the number of cracks increased markedly, and their widths expanded. In some local areas, the cement paste peeled off, the surface roughness increased and the overall structural performance deteriorated. When the number of freeze–thaw cycles reached 100 (

Figure 12e) and 125 (

Figure 12f), the damage to the microstructure intensified. Cracks were extensively distributed and interconnected. The ITZ was severely damaged and the porosity rose significantly. Some regions exhibited a loose and peeling state, indicating that the microstructure of the material was on the verge of failure.

The aforementioned SEM characterization results indicated that with increasing freeze–thaw cycle counts, the microstructure of hybrid-fiber-reinforced DSRAC gradually transitioned from a dense morphology to a state marked by extensive cracking and elevated porosity. This degradation at the microscopic scale directly gave rise to a decline in the macroscopic mechanical properties. The addition of fibers had, to some extent, retarded the propagation of cracks. However, it had not been able to completely inhibit the cumulative damage induced by the freeze–thaw actions. These findings clearly elucidated the microscopic mechanism underlying the degradation of the material’s durability in a freeze–thaw environment. This provided a theoretical foundation for further enhancing frost resistance through material design strategies, such as optimizing the fiber composition, incorporating air entraining agents and other related measures.

The SEM analysis presented in this paper was primarily centered on uncovering the sequence of the microstructure evolution of the hybrid-fiber-reinforced group under the influence of freeze–thaw cycles. Notwithstanding the fact that no concurrent SEM observations were conducted on the fiber-free control group, the systematic sampling carried out on the fiber-reinforced specimens (with a minimum of three samples for each freeze–thaw cycle) and the observations made at a consistent magnification (200×, except for the initial state where 500× was used) clearly illuminated the mechanism by which fibers impeded the propagation of microcracks. These qualitative findings, when combined with the macroscopic performance data, collectively provided strong evidence for the reinforcing effect of the fibers. Future research endeavors will encompass direct microscopic comparisons between fiber-containing and fiber-free specimens. Additionally, image quantification techniques will be employed to enable more refined and in-depth characterizations.

Through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations, this study focused on revealing the inhibitory mechanisms of fibers against physical damage under freeze–thaw cycles. However, the unique chemical composition of desert sand might induce chemical microstructure evolution (e.g., chemical alterations of hydration products at the ITZ), which also constituted a potential factor influencing long-term durability. Given that this study primarily focused on the degradation of physical–mechanical properties and the physical crack-arresting effect of fibers, the quantitative characterization of chemical interactions represented a critical direction for future in-depth investigations.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the performance evolution and damage mechanism of hybrid-fiber-reinforced DSRAC under freeze–thaw cycling. The exploration was carried out through macroscopic mechanical experiments, freeze–thaw durability tests, damage model establishment and microstructure analysis. The main findings were as follows:

(1) At a desert sand replacement ratio of 30%, the initial mechanical properties of DSRAC were found to be optimal; however, its freeze–thaw resistance performance was relatively poor. When the replacement ratio was 25%, although the initial strength was slightly lower, the performance degradation during the freeze–thaw process was observed to be more gradual, indicating better durability.

(2) The incorporation of hybrid fibers (F0.15-S0.5) was shown to significantly enhance the mechanical properties and freeze–thaw resistance of DSRAC. The compressive strength of specimens in this group was measured to be 31.6% higher than that of the fiber-free control group. After 125 freeze–thaw cycles, the loss rates of compressive strength, splitting tensile strength and flexural strength dropped to 73.2%, 60.1% and 46.4%, respectively—values that are significantly lower than those of the reference group.

(3) The fibers were proven to effectively mitigate the mass loss and the decline in the dynamic elastic modulus during the freeze–thaw process. After 125 freeze–thaw cycles, the mass loss of the fiber-added group was only 0.34%, and the dynamic elastic modulus remained at 72.9%, demonstrating excellent durability performance.

(4) The freeze–thaw damage models constructed using the exponential function and Aas-Jakobsen function were verified to precisely characterize the evolution pattern of the relative dynamic elastic modulus with freeze–thaw cycle counts, with coefficients of determination R2 ≥ 0.96. Guo’s constitutive model was verified to effectively represent the changes in the stress–strain relationship before and after freeze–thaw, and the goodness-of-fit was higher than 0.97 for all cases.

(5) SEM analysis revealed that as the number of freeze–thaw cycles increased, the microstructure of the concrete gradually evolved from a dense state to a state with multiple cracks and high porosity. The addition of the fibers was shown to significantly retard the damage of the interfacial transition zone and crack propagation behavior, thus enhancing the macroscopic freeze–thaw resistance and ductility.

Freeze–thaw tests in this study were conducted in a pure water environment, and no quantitative characterization of the concrete’s pore system was performed. Future research should integrate ASTM C457 standard [

55] analysis to comprehensively evaluate the synergistic durability enhancement mechanism of air-entrainment and fiber-hybridization strategies for desert sand recycled concrete under multi-factor environments (e.g., salt–frost coupling). Furthermore, this research was predominantly centered on the material scale. As such, the mechanical properties of full-scale structural members remain to be further validated. Consequently, future research endeavors should prioritize investigations into durability under the coupled action of multiple corrosion factors. Additionally, experimental verification of the findings of this study through tests on structural components is essential. Such efforts will facilitate the translation of these research outcomes into practical engineering applications. Performance analysis in this study relies primarily on mean values and standard deviations. Future research will leverage larger sample sizes (n ≥ 6) and employ more diverse statistical visualization tools, such as boxplots, to conduct a more thorough analysis of the distributional characteristics of performance data, thereby providing a more comprehensive reliability assessment.