Abstract

This study addresses the fabrication challenges associated with producing diverse geometries for concrete dry connections, particularly regarding cost, time, and geometric limitations. The research investigates methods for fabricating precise, rebar-free dry connections in concrete, focusing on stamping and green-state computer numerical control (CNC) milling. These methods are evaluated using metrics such as dimensional accuracy, tool abrasion, and energy consumption. In the stamping process, a design of experiments (DOE) approach varied water content, concrete age, stamping load, and operational factors (vibration and formwork) across cone, truncated cone, truncated pyramid, and pyramid geometries. An optimal age range of 90 to 105 min, within a broader operational window of 90 to 120 min, was identified. Geometry-specific exceptions, such as approximately 68 min for the truncated cone and 130 min for the pyramid, were attributed to interactions between shape and age rather than deviations from general guidance. Within the tested parameters, water fraction primarily influenced lateral geometric error (diameter or width), while age most significantly affected vertical error. For green-state milling, both extrusion- and shotcrete-printed stock were machined at 90 min, 1 day, and 1 week. From 90 min to 1 week, the total milling energy increased on average by about 35%, and at one week end-face (head) passes caused substantially higher tool wear, with mean circumference losses of about 3.2 mm for head engagement and about 1.0 mm for side passes. Tool abrasion and energy demand increased with curing time, and extrusion required marginally more energy at equivalent ages. Milling was conducted in two engagement modes: side (flank) and end-face (head), which were evaluated separately. End-face engagement resulted in substantially greater tool abrasion than side passes, providing a clear explanation for tolerance drift in final joint geometries. Additionally, soil-based forming, which involves imprinting the stamp into soft, oil-treated fine sand to create a reversible mold, produced high-fidelity replicas with clean release for intricate patterns. This approach offers a practical alternative where friction and demolding constraints limit the effectiveness of direct stamping.

1. Literature Review

Structural connections critically influence global performance, construction cost, and buildability. Among them, dry, concrete, and grout-free connections transfer forces primarily through bearing and geometric interlocking. When suitable geometries, materials, and locations are chosen, these joints can achieve high capacity while keeping assemblies demountable and reconfigurable without adding rebar or cast-in-place grout between parts [1,2]. Various fabrication routes have been used to realize such connections, including CNC milling of contact surfaces and precision formwork for accurate fitting and interlocking [3,4,5]. Both approaches, however, constrain the feasible design space and are costly and time-consuming at scale. Consequently, geometry selection must consider not only structural capacity but also assembly parameters, interlocking factors [6], and manufacturability constraints. This yields two coupled challenges: devising dry-joint geometries that balance capacity with ease of assembly, and identifying efficient, repeatable fabrication methods for producing them. In short, dry connections offer a compelling path to high-capacity, demountable structures, but their broader adoption hinges on processes that deliver precise interlocking geometry at acceptable cost and speed. From mixing to its nominal 28-day strength, concrete passes through distinct stages marked by rapid changes in workability and stiffness. During the first 30–60 min, the mixture is considered fresh concrete: highly workable and suitable for placement and compaction [7]. As hydration proceeds, the material enters the setting phase, characterized by an initial setting time typically around 90–150 min, depending on admixtures and ambient conditions [8,9]. The final setting time is commonly reached after roughly 360–600 min (6–10 h), beyond which the concrete loses workability and gains structural rigidity [10,11]. Within 24–48 h, concrete enters an early hardening stage, attaining sufficient strength for self-support and, under favorable conditions, formwork removal [9,10]. Continued curing is essential: by 7 days, approximately 70% of the 28-day compressive strength is typically achieved [10,12]. By 28 days, the target design strength is generally reached under standard curing practices [11,12]. In practice, this time-dependent evolution creates a narrow fabrication window: as workability diminishes, achievable precision and surface quality decline, an essential constraint for processes such as stamping and green-state milling that rely on controlled deformation or milling of young concrete. Stamped (patterned or imprinted) concrete reproduces the appearance of stone, brick, or timber by pressing textured molds or rigid stamps into freshly placed “green” concrete while it remains plastic. The process is commonly used for decorative pavements and precast architectural panels and, conceptually, has been practiced for decades in industry [13,14]. The critical determinant of quality is timing: stamping should occur after bleed water has vanished yet before the rapid rise of yield stress, typically within ∼30–90 min after placement, when the mix is plastic enough to capture fine details but firm enough to resist smearing [15]. Adequate stamping pressure is required to fully express surface relief and achieve dense, defect-free skins. However, applying very high pressure too late in the setting process, once the internal yield stress in the core has significantly increased, can promote localized microcracking due to stress concentrations [16]. Consequently, tight control over the fresh-state, pressure application, and substrate support is essential. For structural components that demand high geometric fidelity (e.g., interlocking dry connections), conventional surface stamping is limited because it primarily modifies the skin and is highly sensitive to timing tolerances; this motivates process variants that act volumetrically or operate earlier in the green-state. CNC (computer numerical control) milling fabricates interlocking joint geometry by subtractive machining and is attractive where tight tolerances and complex freeform features are required [15,17]. Milling of cured elements can deliver excellent dimensional accuracy and surface quality, often surpassing formwork-based approaches in precision. Nonetheless, broad adoption is constrained by economic factors: long machining times, high energy demand, and significant abrasion of diamond or carbide tooling when milling abrasive, brittle matrices, especially in high-strength mixes [18]. An emerging alternative is green-state milling, i.e., machining during early-age curing while the material is firm yet not fully hardened. Acting in this state reduces milling load, tool abrasion, and energy relative to milling in the fully hardened state, while still achieving repeatable geometry if adequate fixturing and process control are provided. This strategy is particularly relevant to layered elements produced by extrusion or shotcrete, where early-age machining can correct or finalize interlocking features before substantial stiffness gain and shrinkage set in. This study addresses fabrication challenges for dry connections by systematically investigating stamping and CNC milling during the green state of concrete, defined as the period when the material is firm yet workable. The objective is to produce precise, rebar-free interlocking connections without reliance on a costly precision formwork or fully hardened machining. This approach aims to reduce tool abrasion and energy consumption, minimize the risk of microcracking, and enhance overall fabrication efficiency.

2. Methodology

Two fabrication processes, stamping and CNC milling, were applied during the green state of a printable concrete formulated for robotic concrete printing at the Digital Building Fabrication Laboratory (DBFL) of the Institute of Structural Design (ITE) at TU Braunschweig. A single concrete mixture (cement, sand, and aggregates) was employed throughout to maintain comparability across all time points and process conditions.

2.1. Concrete-Mortar Properties

The printable material used in this study is a commercially available sprayable fine-grained concrete premix supplied by MC Bauchemie Müller GmbH & Co. KG (Bottrop, Germany). The maximum aggregate size is 2 mm. The binder system consists of ordinary Portland cement CEM I 52.5 R, combined with pozzolanic additions and silica fume, while the aggregate skeleton is a fine siliceous sand (0–2 mm). The premix additionally contains pulverized mineral additives and micro-polypropylene fibers to enhance cohesion and reduce rebound; no coarse aggregate is used. A more detailed process-oriented characterization of the same material in robotic shotcrete 3D printing (SC3DP) is reported in [19]. The exact mass fractions of the constituents and the water–binder ratio are proprietary to the manufacturer and cannot be disclosed in full. To maintain reproducibility despite this limitation, (i) the commercial product and supplier are identified; (ii) the cement type, aggregate size range, presence of silica fume, pozzolanic additions, and fibres are specified; and (iii) the target fresh-state workability, together with the complete set of process parameters used in the printing tests (concrete and air volume flows, traverse speed, nozzle-to-strand distance, and accelerator dosage), is reported. Flow-table tests were carried out according to DIN EN 12350-5 [20], and all batches used for printing were adjusted to a target spread of cm. For the parameter study presented here, the accelerator dosage was set to 0%, whereas for the double-curved vault demonstrator in [19], an accelerator volume flow of 1.5% was used to increase early stiffness. The corresponding values are explicitly listed in the tables describing the experimental settings in that work.

In previous studies on this material, time-dependent properties were characterized by measuring age-dependent yield stress with a handheld penetrometer at two locations: a core zone (interior) and an edge zone (within 2–5 mm of the free surface). In parallel, surface texture was quantified using the Estimated Texture Depth (ETD) and Mean Profile Depth (MPD) as roughness metrics [7]. Table 1 summarizes representative values over the first 90 min after placement and for selected stamping/machining times. As the material stiffens, core yield stress increases markedly while the edge remains comparatively compliant. Over the same period, delaying surface processing reduces ETD/MPD, indicating a diminished capacity to accept crisp imprinting or to be cut cleanly under identical tooling conditions. Following [7], ETD and MPD are used here as surface processability proxies: lower ETD/MPD at the same age correlate with reduced imprint acceptance and rougher subtractive finishes for the same tool and process parameters.

Table 1.

Time-dependent changes in core yield stress and surface texture metrics (ETD, MPD) measured by penetrometer for the printable concrete (water fraction ). Penetrometer values reflect material yield stress under quasi-static loading with a small tip (low confinement).

2.2. Stamping Green-State Concrete

The setup used to apply stamps to green-state specimens is shown in Figure 1. The assembled stamp block is mounted to a 25 kN hydraulic jack on a rigid frame, and specimens are cast in a compliant plastic container placed on a vertically guided steel platen. The platen is permitted to translate vertically with low friction, and the applied force during stamping is recorded by an in-line load cell (digital force meter) located beneath the platen. By this arrangement, normal loading is enabled while the lateral constraints on the specimen sides are minimized. Because specimens were cast in a thin (≈0.5 mm) flexible plastic liner, the lateral restraint from the sidewalls was negligible. The in-line load cell, therefore, provides the global reaction to normal penetration, which is compared across runs rather than interpreted as a local contact stress.

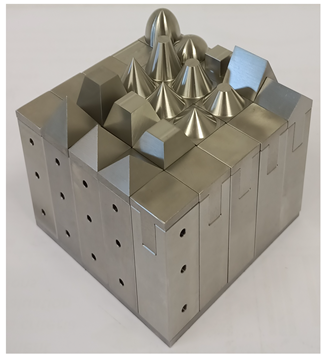

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for stamping tests: a 25 kN hydraulic jack mounted on a rigid frame, a custom multi-geometry stamp block with interchangeable inserts, and an integrated force measurement unit under the floating steel platen. Insets show the stamp head, the actuator connection, and the digital force meter used to record applied loads.

The central component of this setup is the stamp, engineered with adaptable geometry to facilitate rapid assembly and disassembly for changing stamp configurations. Eight geometry types were fabricated in three heights (10, 15, and 20 mm), with each type available in both positive and negative forms to enable production of both connection sides. In total, 48 (2 × 3 × 8) stamps were produced, each fitting into a holder of uniform section size (25 × 25 mm). These holders can be arranged on a base plate to create larger stamps with customizable geometries and dimensions (e.g., 25 × 100 mm for a 1 × 4 array or 125 × 125 mm for a 5 × 5 array). Additionally, flat stamps without geometric features were prepared to serve as caps for the holders. All components are connected using screws inserted through pre-designed holes.

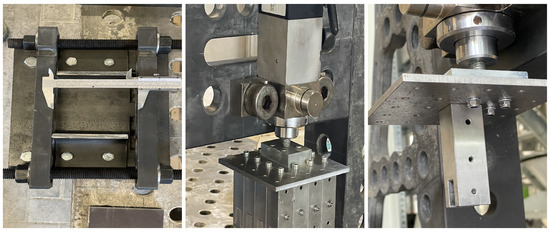

2.3. Robotic Milling Operation

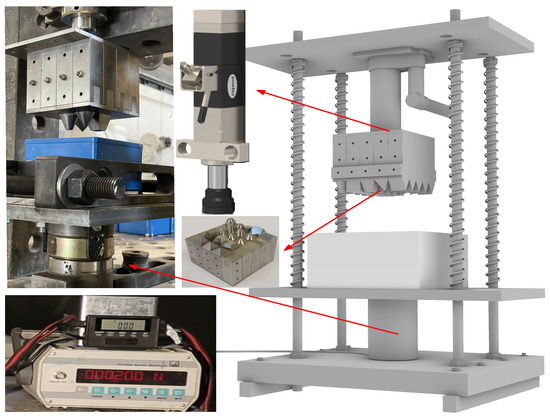

At DBFL, robotic fabrication of dry-joint geometries was performed with a five-axis industrial robot equipped with an end-effector spindle and interchangeable milling/sawing tools. In the present study, all Design of Experiments (DOE) trials used milling; sawing tools were available only for stock separation and are not analyzed here. Two tool–material engagement modes were tested (see Figure 2): (i) side milling (flank engagement) and (ii) end-face (head) milling. The workflow comprised CAD modeling in Rhino 3D and CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) toolpath planning/simulation in EasyStone (DDX Software Solutions, Sopra, Italy); fixtures and collision were verified on a portable clamping table, and the post-processing program (tool IDs, dimensions, and magazine positions) was transferred to the robot controller. CAM strategies used linear toolpaths with controlled step-over/step-down; selection criteria and safety clearances were kept consistent across tests to ensure comparability. For comparability, six identical rough-diamond milling tools were employed across all milling operations. The same printable concrete and identical printing parameters were used for both shotcrete and extrusion processes. To attribute abrasion unambiguously, each of the six tools was dedicated to exactly one test set – (no reuse across sets). Specimens were processed at three ages after printing, 90 min, 1 day, and 1 week, yielding six test sets –.

Figure 2.

Experimental set-up for green-state and time-step milling.

As shown in Figure 2, each printed element was partitioned into three equal sections. To isolate the two engagement modes, linear passes were executed separately on the end face (top face; end-face milling) and on one lateral face (side milling). Energy consumption was logged by the machine/controller during each pass, and tool abrasion was documented after each test; cumulative toolpath length was recorded for normalization of wear/energy metrics.

2.4. Testing Setups and Geometrical Evaluations

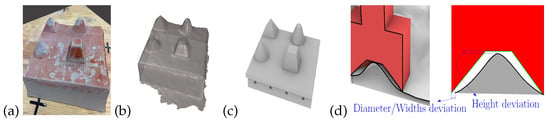

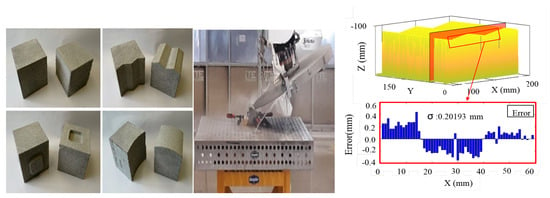

To develop the experimental (DOE) setups and evaluate the effects of parameters on stamping accuracy, analyses were conducted in Minitab® 19. An initial water–time screening (Table 2), was performed with one test per age–water combination () to delimit feasible ranges. In the subsequent Plackett–Burman screening and geometry-specific DOE series, each unique factor combination was likewise realized once ( per DOE cell), with the run order generated and randomised in Minitab. The influence of water fraction [%], stamping load [kN], and age after placement [min] on height and diameter/width deviations for the specimens as a whole was examined. to develop the experimental tests, two strategies were used: a Plackett–Burman screening to identify influential factors, followed by a full factorial design to study main effects and pairwise interactions. Unique input combinations were tested in randomized order. Each stamped element was 3D-scanned and compared with its reference CAD model to quantify geometric accuracy. The scans produced high-resolution point clouds with a target point spacing of , sufficient to capture both sharp edges and smoothly curved features. The workflow comprises four steps, physical sample capture, 3D reconstruction, rigid best-fit registration to the CAD model, and deviation mapping, as shown in Figure 3. Registration was performed using an iterative closest-point alignment and was checked using visual overlays. Signed point-to-surface distances were then computed to enable both visual and quantitative assessment of fabrication precision, with special attention to interlocking surfaces and sloped transitions. After managing the tests and documenting the geometrical deviations, the test outputs were re-imported into the software and evaluated using optimization, interaction plots, response tables, and regression models. For statistical analysis, two scalar deviations were extracted from the features: a diameter/width deviation at mid-height and a height deviation at the apex, obtained from section-based measurements on the registered scan.

Table 2.

Screening matrix: measured stamping force F [N] and nominal stress [N/mm2] with mm2, for four water fractions and five ages t. Highlighted cells mark the practical operational range for stamping (–120 min).

Figure 3.

Workflow for geometric accuracy assessment: (a) fabricated concrete sample, (b) high-resolution 3D scan, (c) reference CAD model, and (d) scan-to-CAD overlay and deviation visualization.

In response to this comment, Table 3 now reports the factor levels and coding used in the PB12 design. The composite-geometry screening (tests A.1–A.12) was implemented as a three-factor Plackett–Burman design with two levels for each factor: water fraction (10%/15%), age at stamping t (50/130 min), and stamping load F (nominally 17/25 kN). The full PB12 matrix and factor coding are summarized in Table 3, and the corresponding ANOVA tables together with Pareto and normal probability plots for each response (, ) are provided in the Supplementary Information (Figures S1–S8).

Table 3.

Factor levels and coding for the PB12 screening and subsequent 2-level factorial regressions on the composite stamp.

In these two-level factorial regressions, only one main effect reaches statistical significance at : for the truncated-pyramid diameter deviation , the water fraction is significant with and an estimated effect of ≈0.88 mm between the low and high levels, whereas load and age remain non-significant ( and ). For all other diameter/width responses and for all height responses , no main effect crosses ; age and water still show the largest standardized effects (in the order of 1–3 mm), but only at the trend level ().

3. Main Body

3.1. Green-State Stamping

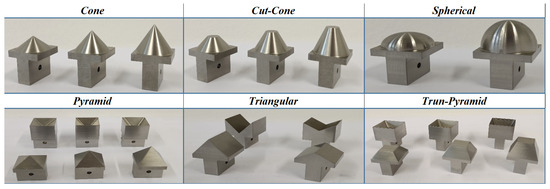

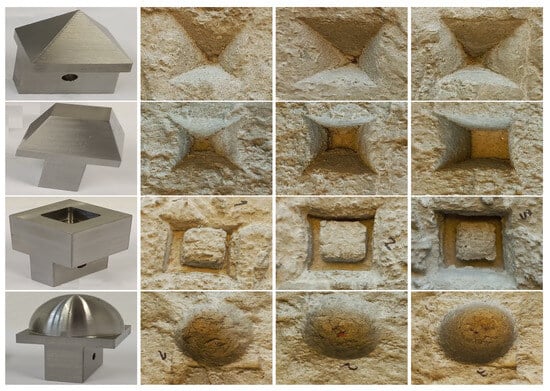

This section examines the influence of process parameters on the dimensional accuracy of stamped geometries in green-state mortar. The experimental design encompassed multiple test series simulating practical prefabrication scenarios with diverse joint interfaces and surface profiles. The specimens incorporated a variety of geometries representative of dry-joint interfaces and architectural features, such as cones, truncated cones, pyramids, truncated pyramids, hemispheres, triangular wedges, and box (rectangular prism) profiles (see Table 4). The experimental campaigns evaluated several factors. Three primary variables—water fraction ( [%]), stamping load (F [kN]), and age after placement (t [min])—formed the basis of the design of experiments (DOE) analysis. Additional factors, including vibration mode, impact speed, negative stamp configuration, geometry type, flat-cap stamp tests, joint combinations, formwork or platen stiffness (measured as deflection under load), and stamping/un-stamping time, were either examined in supplementary series or held constant to ensure comparability. Qualitative assessments of surface quality and edge fidelity were also documented. An overview of the investigated stamp geometries and representative imprints is provided in Figure 4.

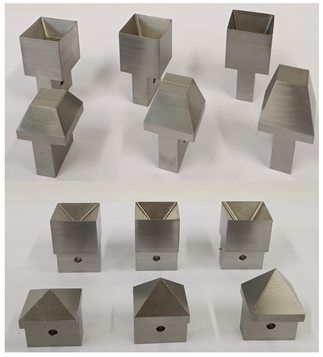

Table 4.

Details of the stamping tools used in the experiments, showing (a) assembled multi-geometry stamp block, (b) examples of individual stamp pairs with corresponding positive and negative geometries, and (c) CAD models of all stamp types, including pyramid, truncated pyramid, cone, cylindrical, hemisphere, truncated cone, box, and triangular forms.

Figure 4.

Representative fabricated stamps and imprints: cone, truncated cone, hemisphere, pyramid, triangular wedge, and truncated pyramid.

3.1.1. Water Fraction, Age, and Geometry Set

Water–Time Screening

To define an operational range for stamping, the effects of age after placement (t, in minutes) and water fraction ( [%]) were initially screened. Mixtures with water fractions of 11.5%, 13.0%, 15.0%, and 16.7% were stamped at time intervals of 15, 40, 65, 90, and 120 min using a single insert. These preliminary tests employed a single-insert configuration. Table 2 presents the measured stamping force (F, in newtons) and the corresponding nominal stress (, in N/mm2), calculated as with . This initial water–time screening was exploratory (one run per condition; ) and served to establish factor ranges for subsequent DOE analyses. Here, w denotes the mass of mixing water and c the mass of cement; aggregate is not included in . For any target , one may compute and , where is the chosen binder mass. Lower water fractions (11.5%) consistently produced the highest resistance, reaching up to at min, whereas the 16.7% mixture exhibited the lowest resistance. Intermediate water fractions (13–15%) provided a balance between workability and strength; for example, 13% at 90 min achieved (), and 15% at 120 min reached (). These results indicate that a practical stamping window exists at min with , where the material exhibits sufficient plasticity to prevent microcracking and adequate stiffness to maintain geometric integrity for the 25 mm × 25 mm insert. These parameter ranges were therefore selected for subsequent studies to achieve higher geometric precision. for subsequent studies was favored, as a balance between sufficient stiffness (to hold geometry) and workable rheology (to avoid tearing, suction, and incomplete filling) under identical boundary conditions.

Two time constructs are used in this study—a global operational range and a general optimum band: (1) a global operational range for cross-geometry screening and comparability, fixed at 90–120 min; and (2) a general optimum band observed for most cases at 90–105 min. Unless stated otherwise, age is measured from the end of mixing to the start of contact. Varying dwell time (contact duration) does not alter this age definition. A direct, one-to-one comparison between Table 1 and Table 2 is not possible. As an independent material reference, Table 1 reports the material yield stress from penetrometer tests, whereas Table 2 lists the stamping force and the nominal stress during geometric imprinting (with F in N and ). Early in stamping, the actual contact area is smaller than ; therefore is a lower bound on the true contact stress, and as the stamp sinks in, the contact area grows toward and approaches the mean contact stress. In addition, textured contact, partial confinement, interface friction, and a higher loading rate increase the required force compared with the quasi-static, low-confinement penetrometer test, so exact equality between the two measures should not be expected, and agreement should be judged in a comparative sense. To relate both datasets, the stamping-derived nominal stress is reported as a ratio to the age-matched penetrometer yield (via linear interpolation). At 90 min, across the four water fractions (11.5, 13.0, 15.0, 16.7%), the typical ratio is about 3.5 (min–max 0.7–6.4), meaning the stamping-based stress is usually several times higher than the penetrometer yield. However, it can approach or dip below parity in some cases. Overall, this serves as a consistency check rather than a test of strict numerical equality, with variability governed by mix water content, age, and process conditions.

3.1.2. Time-Dependent Stamping Forces for Diverse Geometries

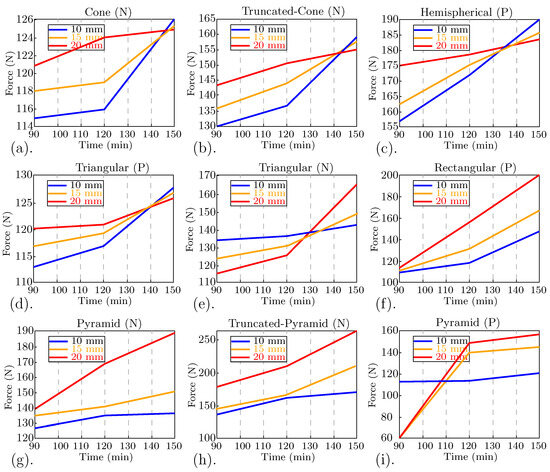

Thirty stamp configurations at a fixed water fraction of and three ages were analyzed. The set covers positive (P)/negative (N) polarities and three nominal depths (stamp heights) of 10, 15, and 20 mm, plus single- and grouped-flat patterns. The reported force F [N] is the reaction measured beneath the floating platen. Figure 5 presents force–time histories for all configurations.

Figure 5.

Force–age response for stamp penetration between 90 and 150 min at . Each subplot shows the measured reaction force during stamping for a given geometry and polarity: (a) cone (N), (b) truncated cone (N), (c) hemispherical (P), (d) triangular (P), (e) triangular (N), (f) rectangular (P), (g) pyramid (N), (h) truncated pyramid (N), and (i) pyramid (P). Curves correspond to nominal imprint depths of 10, 15, and 20 mm (blue, orange, and red, respectively). Here, P and N denote positive and negative stamp polarities.

The force–time curves presented in Figure 5 align with the screening values reported in Table 2. At and , Table 2 indicates , while the curves display values of approximately 114–116 N for the cone (N) and 115 N for the triangular (P) geometries (panels a, d). At , Table 2 lists ; the corresponding curves show approximately 160 N for the pyramid (P, 20 mm) and 165–175 N for the hemispherical (P, 20 mm) (panels i, c). Minor discrepancies are attributable to geometry and depth effects not captured in the single-insert screening. Overall, the figure data corroborate the table in both magnitude and trend. The narrowest spread across depths is observed for the cone (N), which stays within roughly 114–126 N (Figure 5a). Overall, the curves show a consistent time-dependent strengthening across configurations (panels a–i). For the triangular (P) stamp, force increases gently with time and remains relatively narrow across depths (≈114–128 N) (Figure 5d), while the negative geometry of them demands mainly higher forces. For instance, the triangular (N) case also rises with time, starting near 110 N and reaching about 165 N (Figure 5e).

Among the tested geometries, the pyramid (P) required the lowest forces overall, averaging around 110 N and starting near 90 N at 90 min for 10 mm depth (Figure 5i). In contrast, the truncated pyramid (N) exhibited the highest force demand, reaching approximately 250 N at 150 min and 20 mm depth (Figure 5h); the hemispherical (P) peaked lower, at about 190 N under the same conditions (Figure 5c). The resulting gap of roughly 140 N between these extremes highlights the strong influence of the indenter geometry on stamping resistance. Note that min lies beyond the 90–120 min operational window; it is included here to extend the age trend for penetration resistance.

Depth sensitivity is strongly geometry-dependent: the effect of increasing penetration from 10 to 20 mm is most pronounced for the truncated pyramid (N) and remains substantial for the pyramid (N) and hemispherical (P), while it is minimal for the cone (N) (Figure 5a,c,g,h). Likewise, across the two polarity pairs available, negative geometries consistently demanded higher forces than their positive counterparts (triangular: e > d; pyramid: g > i). In terms of time evolution, the steepest increases are observed for the truncated pyramid (N) and pyramid (N), whereas cone (N) and triangular (P) grow more slowly (Figure 5a,d,h,g).

3.1.3. Effect of Complex Geometric Arrangements on Stamping Force

Effect of Grouped Layouts

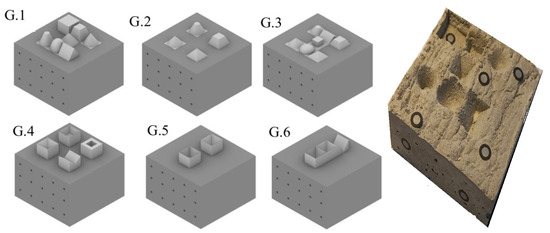

Six grouped configurations (G1–G6) were tested on cm specimens at and ages of min, combining positive, negative, and flat inserts in a single shot to probe interaction effects (Figure 6). Among the layouts, G4 produced the highest forces at all ages, peaking near ∼2200 N, consistent with dense arrays of sharp negative forms that increase confinement. G3 strengthened markedly with age (from ∼1380 to ∼3209 N) as pyramidal/domed elements engaged more material, Table 5. By contrast, G1 remained the lowest, reflecting smoother geometries that allow gradual penetration and reduce stress concentration. G2 exhibited a steady increase across ages (no dip at 120 min), indicating stable engagement behavior. G5 and G6 peaked at 120 min after a smooth initial rise. Overall, force demand increases with geometric complexity and compact spacing; however, through layout optimization (spatial arrangement and stamp-shape selection), equivalent imprint clarity can be achieved at a lower global load. For fair comparison across layouts, it is recommended to normalize by the active contact area, defined as the sum of the nominal footprint areas of inserts engaged at the target penetration. Grouped layouts are physically consistent with the single-insert tests. However, the loads do not scale linearly with the number of inserts due to interaction, confinement, interfacial friction, and platen compliance.

Figure 6.

Stamp layouts for grouped geometries (G1–G6) along with corresponding force testing results. Each group contains a specific arrangement of positive and negative geometries to evaluate combined stamping effects. The right image shows an example of the resulting impressions on the concrete surface after testing.

Table 5.

Stamping forces for grouped configurations (G1–G6) at . Values are global reactions (N) measured during the grouped press at the indicated ages.

3.1.4. Experimental Observations and Considerations

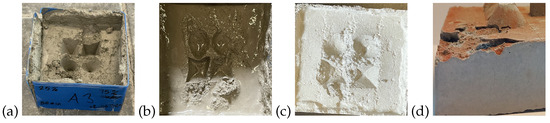

Lubrication: Application of a thin, uniform lubricant layer between steel stamps and fresh concrete reduced friction and suction, particularly for flat or concave geometries. Excess lubricant accumulated in recesses, resulting in droplet marks or surface defects. Removing surplus lubricant to achieve a matte surface prevented fluid entrapment and facilitated clean stamp release. Moisture: The concrete mix’s moisture content significantly influenced stampability. Increased water content elevated sidewall pressures, promoted flooding into recesses, and caused blurring of bottom surfaces. Reduced water content enhanced edge definition but heightened the risk of tearing or microcracking during demolding, especially for sharp or thin-walled features. Maintaining the mix within the defined green-state operational range optimized both flowability and shape fidelity (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Typical failure modes during stamping: (a) overpressure or broken formwork, (b) excessive water fraction, (c) insufficient lubrication, and (d) inadequate stamp travel or poor leveling.

Air Entrapment and Surface Integrity: Air entrapment represented a significant limitation, particularly for inverted and deep profiles. Air pockets beneath the stamp hindered complete filling, resulting in shallow or incomplete imprints. This effect was exacerbated in wetter mixes, where bleed-water films and local hydrostatic backpressure impeded air venting, delaying full seating and reducing surface fidelity. Stamp Geometry and Adhesion Forces: The stamp geometry significantly affected both insertion resistance and removal behavior. Rounded geometries, including hemispherical or dome-like forms, exhibited increased adhesion during demolding due to the expanding effective contact area with penetration depth. Conversely, angular stamps with sharp edges concentrated stress along ridges and corners, increasing the likelihood of surface damage during extraction. In multi-feature layouts, simultaneous stamping of all features was necessary to prevent uneven displacement and distortion of adjacent details. Initial trials with commercially available plastic box forms yielded inadequate edge and corner definition. Under elevated loads, these forms exhibited bending, joint leakage, and insufficient stiffness. Subsequently, rigid and well-sealed forms accommodated higher forces encountered in complex arrays (often exceeding 2 kN) and provided improved control over edges. In subsequent experiments, well-sealed formwork was required to achieve dimensional accuracy. Precise calibration of lubricant application and stamping speed minimized surface artifacts and prevented suction. Stamping multi-feature patterns in a single pass avoided cross-interference between elements. Consistent cleaning and washing between trials enhanced repeatability and limited carry-over of lubricant or residue. The combined influence of mix rheology, stamp geometry, and operational procedures determined imprint quality and force requirements; thus, experimental controls and equipment must be coordinated to maintain fidelity while managing applied loads (see Figure 8). Hardware details of the stamping setup are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

Examples of degraded stamp impressions on cured concrete surfaces. The quality of the impressions varies depending on geometry type, surface preparation, and material compaction. Circular and hemispherical shapes tend to maintain sharper definition, while elongated and narrow features are more prone to edge erosion and surface roughness.

Figure 9.

Hardware details of the stamping setup: adjustable clamping frame, mounted stamp assembly with hydraulic linkage, and side view showing alignment and fastening.

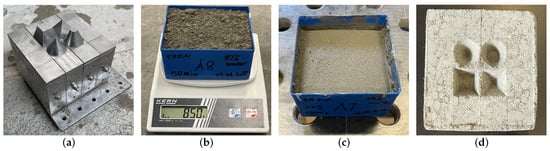

3.1.5. Experimental Setup for Composite Geometry Stamping:

To evaluate multiple geometries under consistent material and loading conditions, a composite steel stamp was assembled with four features—truncated cone, cone, truncated pyramid, and pyramid—mounted on a single base plate so they could be imprinted simultaneously into fresh concrete blocks. Tests were performed with a manual hydraulic press using a controlled cycle: after the stamp first contacted the surface, a downstroke was applied to the target depth, followed by a upstroke for withdrawal. Tests were displacement-controlled (programmed downstroke to a target depth with fixed timing); the hydraulic pressure limit only capped the maximum force (see Figure 9). A thin release film was wiped on before each run to limit friction and suction; over-application was avoided to prevent pooling in recessed regions and loss of imprint fidelity. Because all four features were pressed together, the recorded reaction corresponds to the global load on the assembly rather than per-feature forces (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

General stamping process and setup: (a) assembled stamp block containing multiple geometries, (b) measurement of concrete mix weight before casting, (c) freshly poured concrete in the mold before stamping, and (d) final imprinted geometry after demolding.

To make the control protocol reproducible, the three phases of the stamping cycle (downstroke, dwell, and un-stamping) and their characteristic durations for the main test series are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Control mode and stamping cycle timing for the main test series. Each cycle consists of a displacement-controlled () downstroke, a dwell under nominally constant load, and a linear upstroke.

Lubrication

In all direct stamping tests, a thin release film was applied between the steel stamps and the fresh concrete to reduce friction and suction. A commercially available multi-purpose mineral–oil spray (WD-40 Multi-Use Product) was used as the lubricant. This low-viscosity, petroleum-based formulation is typically used as a water-displacing corrosion inhibitor and light lubricant, forming a very thin, non-reactive film on metallic surfaces. Before each run, the stamp surfaces were cleaned and dried; the lubricant was then sprayed once from approximately 15 cm and immediately wiped with a lint-free cloth, leaving a uniform, very thin, matte film. Preliminary trials showed that visible droplets or pooling in recesses led to voids, rounded edges, and lens-shaped marks. In contrast, insufficient lubrication increased adhesion and suction during withdrawal and occasionally caused surface tearing at sharp features. During the main test series, the same operator applied the lubricant using this standardized spray-and-wipe procedure, and the visual criterion of a continuous matte sheen without wet spots was used as a practical control of the lubricant quantity. This protocol ensured a repeatable, very thin lubricant layer. However, the film thickness was not measured directly; the applied amount was controlled operationally by the fixed spray–wipe procedure and the visual criterion (continuous matte sheen without visible wet spots).

The study varied three factors within a practical green-state operational range: mix water fraction at 10% and 15%, age at stamping of 50 and 130 min, and applied stamping load F spanning roughly –. A 12-run Plackett–Burman screening design guided the factor assignments, with the experimental matrix summarized in Table 7. The table lists the water fraction, material age, and the programmed load level for each test. In wetter mixes, higher internal fluid pressure and surface bleeding made complete filling more difficult and increased resistance to displacement. In contrast, drier mixes improved edge definition but raised friction on unstamping and occasionally caused partial tearing at sharp features. Adhesion during removal tended to be stronger for rounded, large-contact shapes, which sometimes disturbed imprint edges at the end of the upstroke. During stamping, insufficient drainage can cause water to accumulate in recesses. Retained water impedes proper settling and consolidation, softens edges, and increases dimensional deviations. The cases shown in Figure 11 illustrate blurred features, voids, and uneven compaction attributable to water entrapment at the tool–concrete interface.

Table 7.

Experimental matrix for composite stamping tests: water fraction (10% or 15%), concrete age (50 or 130 min), and applied stamping load F (kN). The 12 runs follow a PB12 testing plan.

Figure 11.

Examples of surface irregularities and loss of edge sharpness attributed to inadequate drainage during stamping. Entrapped water in cavities likely caused local erosion, voids, and incomplete feature definition.

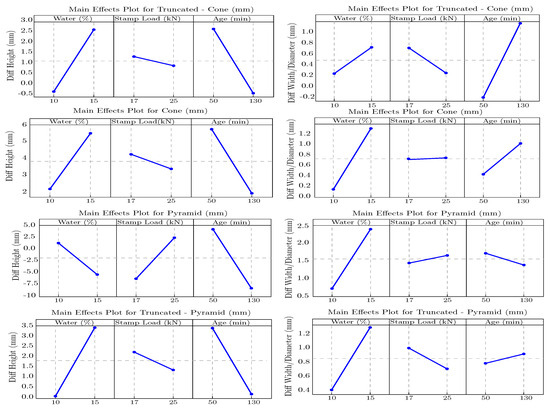

3.1.6. Effect of Processing Parameters on Dimensional Accuracy

To comprehensively assess how processing parameters affect dimensional fidelity in the truncated pyramid (TPyr), two responses were compared to the CAD reference: diameter difference and height difference. Factorial analysis (Pareto and normal probability plots) showed that, at ( DOE main-effects ANOVA), only water fraction was statistically significant for the diameter difference. Increased water improved filling of recessed features, but beyond a threshold, it promoted lateral overspread and reduced diameter accuracy; within the tested range, stamping load and concrete age were not significant for diameter. The height response was more sensitive: higher water and younger concrete ( min) produced greater height gain relative to the CAD target, consistent with lower yield stress enabling deeper penetration. The influence of stamping load was minor yet visible, suggesting limited compaction or rebound effects at higher force, Figure 12. For the truncated cone, a factorial study with water fraction, stamping load, and age (Figure 12) revealed clear rheology-driven trends. Raising water from 10% to 15% increased deviation in both dimensions; the height difference rose from about to beyond , and diameter deviation increased in parallel. This reflects deeper, less-controlled penetration in wetter mixes. Increasing stamping load from 17 to 25 kN produced only a modest reduction in height deviation—consistent with a slight stabilizing effect on the penetration path—while diameter was largely unaffected, indicating that load alone cannot constrain radial spread without sufficient stiffness. Aging from 50 to 130 min consistently reduced deviations (e.g., height from to ∼−0.5 mm and diameter toward zero), as the semi-set matrix better resists over-penetration (Figure 12). Extending the comparison between the cone, truncated cone, pyramid, and truncated pyramid showed a clear pattern. Increasing the water fraction to 15% generally enlarged deviations, with the strongest effect for the cone and the truncated pyramid (deeper penetration and more lateral flow). Pyramid stamps retained the height best as the concrete aged, likely because the sharp tip engages stiffer mixes effectively. With higher water, pyramids remained comparatively less sensitive in height—deviations still increased, but less than for the other shapes—since the point directs the load vertically and limits lateral spread. Stamping load played a secondary role; for the cone and the truncated cone, the higher load (25 kN) slightly improved height control in wetter or younger mixes. Concrete age had the dominant stabilizing effect on height: by 130 min, height deviations decreased across all shapes, while the impact on diameter was geometry-dependent—often decreasing for conical profiles as the matrix stiffened, but showing mixed trends for sharp-edged shapes (Figure 13). Overall, dimensional accuracy depended primarily on fresh-state properties—especially water fraction and age—while stamping load provided fine-tuning. Truncated cones yielded the most internally consistent results—i.e., across repeated trials at the same factor settings, they showed the lowest within-condition scatter in both height and diameter—despite clear factor trends, likely due to their balanced taper and lower resistance to penetration. Pyramids were more age-sensitive in height, yet kept their diameters relatively stable, underscoring that stiffness matters most for sharp shapes (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Main -effect plots for four stamp geometries (truncated cone, cone, pyramid, and truncated pyramid) showing the influence of water fraction (10%/15%), stamping load (16.2–25.5 kN), and age (50/130 min) on deviations in height, width, and diameter. Lower deviations are observed at 130 min, highlighting the stabilizing effect of age.

Figure 13.

CAD geometries (left column) and corresponding concrete imprints under varied water, load, and age (three right columns) for pyramid, truncated pyramid, box (square recess), and hemisphere. Differences in edge definition and surface finish illustrate sensitivity to green-state rheology and loading.

Comparison of factor significance across geometries presents standardized Pareto charts for all eight cases (diameter and height deviations across four stamp geometries). Among all configurations, the pyramid and truncated pyramid show the strongest sensitivity of diameter to Factor A (water fraction): in both, the effect of water exceeds the significance line, indicating that mixture moisture is the most influential parameter governing lateral conformity in these sharp-edged, deep features. For height deviation, no factor crosses the significance limit in the tested ranges; nevertheless, the age of concrete (Factor C) exhibits the relatively most significant standardized effects for the truncated cone and cone, suggesting that vertical accuracy is more governed by curing stage than by water or applied load for these profiles. Across geometries, the stamping load (Factor B) contributes the least to variance within the applied state (approximately ), implying limited sensitivity to the force level compared with mix moisture and age. In practice, this means that, for improved dimensional precision—especially in geometries with sharp or deep features—tight control of the water fraction should be prioritized. Load can be used as a secondary tuning parameter, and age should be selected to fall within a stabilizing green state.

Response Optimization and Comparative Analysis

Beyond the general optimum band, a substantive Shape × Age interaction yields geometry-specific optima outside 90–105 min. These cases are not contradictions of the global guidance but flagged exceptions arising from how each feature interacts with the mix at different stiffness levels. Notable examples include the truncated cone at ∼68 min (earlier, when the matrix is more compliant) and the pyramid at ∼130 min (later, when the matrix better supports steep flanks). For most other geometries, optima cluster within 90–105 min and remain operationally consistent with the 90–120 min screening operational range. To prevent misinterpretation across multiple factors, the following reading guides were adopted: (i) unless stated otherwise, age is referenced to the start of contact; varying dwell modifies contact duration but not the age definition; (ii) 3 min vibration frequently improves fidelity, yet geometry- and mix-dependent reversals occur, so both 1 and 3 min are reported case-by-case; (iii) where multi-feature stamps were pressed simultaneously, reported loads are global (not area-normalized), and shape-specific optima should be compared at consistent dwell and vibration settings; (iv) when an optimum falls outside 90–105 min, captions and tables explicitly flag it as shape-specific. Practically, for mixed or unspecified feature sets, a target of 95 ± 15 min (within the 90–120 min operational range) is recommended, while a dominant geometry should follow its own shape-specific optimum (e.g., ∼68 min for the truncated cone, ∼130 min for the pyramid). To quantify dimensional accuracy, a multi-response optimization was performed for four stamp geometries—truncated cone, cone, truncated pyramid, and pyramid—minimizing the absolute differences between target and measured diameter/width and height. For clarity, and as signed scan-to-CAD differences (measured minus CAD) are reported, while the optimization minimized their absolute values with equal weights in a composite desirability (where higher D indicates a better simultaneous fit of both responses), as reported in Table 8.

Table 8.

Multi-response optimization for the four stamp geometries was carried out in Minitab over the tested ranges of water fraction (10–15 %), stamping load F (17–25 kN), and age t (50–130 min). The responses were the absolute deviations in height and lateral diameter/width. Each response was converted to a desirability , and the composite desirability was used ( = perfect match). The table lists, for each geometry, the three settings with the highest D in the tested domain.

As Table 8 shows, the truncated pyramid achieved the best overall fidelity () with small, balanced errors ( mm, mm) at , kN, and min. Both the truncated cone and the cone also optimized well (), again at 10% water and the higher load level 25 kN; their optimal ages diverged, with the truncated cone favoring an earlier state (∼68 min) and the cone landing near the late green-state (∼104 min). The pyramid remained an outlier: even at min (at the edge of and locally beyond the general 90–105 min optimum band) and with a reduced load of 17 kN, it exhibited a large negative height deviation ( mm) and the lowest desirability (), indicating persistent height underfill and the need for further process or geometric refinement. The poor response of the pyramid in Table 9 (large negative height, mm; low desirability at , kN, min) was obtained under the factorial DOE conditions and should not be conflated with the subsequent duration study. In the duration series, boundary control was tightened, the protocol fixed and kN, and dwell was varied at ages 60 and 90 min; under these refined conditions, the pyramid achieved its best accuracy at min with a 10 min dwell (B.6: mm, mm). The apparent discrepancy is therefore due to different experimental contexts: in the DOE, the main effects were explored at (50/130 min; 17/25 kN) without dwell optimization, where the pyramid remained height-sensitive; in the duration study, with laterally supportive boundaries and a slightly extended dwell, axial consolidation was achieved, and underfilling was removed. In the DOE, the best pyramid setting is still associated with a large height underfill ( mm, ), whereas in the stamping-duration series (B.6), with improved boundaries and a 10 min dwell at 90 min, values of mm and mm are achieved for the pyramid. This difference is attributed to boundary and dwell conditions rather than to a contradiction in the recommended process window.

Table 9.

Optimized settings and resulting lowest experienced deviations for each geometry. The applied quantity is the stamping load F. and denote signed scan-to-CAD differences in diameter/width and height.

Taken together, the optima cluster at 10% water and 25 kN load for three of the four geometries, with age typically in the ∼90–105 min general optimum band (truncated pyramid at 97 min, cone at 104 min). The truncated cone is the notable exception, shifting earlier to ∼68 min. Under these conditions, the truncated pyramid is the most reliable choice for high-dimensional accuracy, whereas the standard pyramid requires additional refinement to mitigate the pronounced height shortfall.

3.1.7. Stamping Duration (Effect of Stamping and Unstamping)

To isolate the effect of operation time on imprint fidelity, a controlled series was conducted in which the contact duration between the stamp and fresh concrete was varied while all other influential variables were held fixed at their previously optimized levels. In this context, contact duration denotes the full interval from the instant of first touch through loading to the target value and the subsequent hold under constant load, up to the completion of un-stamping. Water fraction was fixed at , and the applied stamping load at (load). Two material ages were examined, and 90 minutes after placement, chosen to bracket the preferred green-state operational range identified earlier. Ages of 60 and 90 min in the duration series were selected to represent an early vs. near-optimum contrast, rather than to fully bracket the preferred range (90–105 min; operational 90–120 min). The subsequent factorial DOE provided the wider bracket (50 vs. 130 min) under consistent water, load, and vibration settings, thereby maintaining alignment across series. For each age, three contact durations were imposed, , 3, and 10 minutes, yielding the experimental matrix in Table 10. Dimensional responses were extracted from registered scans as and (diameter/height differences to CAD).

Table 10.

Experimental matrix for the stamping-duration study. Water fraction is fixed at 10%, and the applied quantity is stamping loadF (kN).

This design controls for load and water while probing duration at two levels. At the younger age (60 min), longer contact is expected to enhance vertical consolidation. However, it may encourage lateral spread and adhesion during unstamping. In contrast, at 90 min, the stiffer matrix should reduce over-penetration and springback while still benefiting from a short dwell for full feature formation. The ensuing results are reported as scan-to-CAD deviations to indicate whether brief contact ( min) risks underfill, extended dwell (10 min) risks overshoot, or an intermediate duration (3 min) offers the best balance between height attainment and lateral conformity for the optimized and settings.

Dimensional Accuracy Analysis of Stamped Geometries

After stamping, specimens were 3D-scanned and registered to the CAD reference to extract signed scan-to-CAD differences in diameter/width () and height (). Examples of scan-derived meshes and their surface quality variation are provided in Figure 14. Performance was geometry-dependent. For the truncated cone, B.5 (90 min, 3 min) showed the smallest simultaneous errors ( mm, mm); for the cone, B.6 (90 min, 10 min) attained the lowest height deviation ( mm) with moderate diameter/width error (∼1.92 mm). The truncated pyramid again favored B.5 ( mm, mm), while the pyramid achieved its best accuracy in B.6 ( mm, mm). The influence of very short dwell is age-dependent: at 60 min, the mix is soft enough that even a 0.5 min dwell can cause excessive sinking and lateral spread, whereas at 90 min, the same short dwell risks underfill and springback due to higher stiffness. The downstroke was displacement-controlled to the target depth; the dwell period was held under constant load before withdrawal.

Figure 14.

3D scan results of stamped concrete geometries, showing variations in accuracy and surface quality across different shapes and production parameters. The last image illustrates the corresponding physical stamped sample for reference.

In contrast, specimen B.1 (60 min, 0.5 min dwell) exhibited significant over-deformation, with height errors exceeding 10 mm and diameter/width errors greater than 5 mm. This result demonstrates that stamping at an early age with a very short dwell leads to excessive sinking and lateral spread. Two consistent trends emerged: (i) specimens stamped at 90 min (B.4–B.6) achieved superior dimensional accuracy compared to those stamped at 60 min (B.1–B.3), attributable to increased material stiffness; and (ii) a 3 min dwell time generally provided the optimal balance between complete feature formation and limited dimensional overshoot (notably B.5), while a 10 min dwell time was advantageous for axially sensitive geometries such as the cone and pyramid (B.6), consolidating height without excessive lateral growth. Overall, specimens B.5 and B.6 (90 min with 3 and 10 min dwell times, respectively) produced the most accurate replications across the tested geometries. A 3 min dwell time generally balanced height attainment and lateral control at min; however, when external vibration was varied (1 vs. 3 min) in the subsequent geometry study, cone responses showed that longer vibration could slightly increase height error even as lateral errors decreased (Table 9). Because the 1 vs. 3 min sets were not fully balanced in age/water, this contrast should be read as a trend, not a full factorial test; accordingly, both 1 and 3 min cases are reported and interpreted case-by-case. Across all tested conditions, specimens B.5 and B.6 (age 90 min with contact durations of 3 and 10 min, respectively) consistently achieved the most faithful replication for the examined geometries. This indicates that allowing sufficient material aging in the green state, together with a moderate to slightly extended contact time under constant load, yields the best balance between complete feature formation and control of dimensional overshoot. In the initial studies, the primary goal was to map the force demand across stamp geometries rather than to maximize dimensional fidelity. As a result, while comparative force trends were established, the geometric accuracy of the imprints remained limited. In parallel, it became apparent that stamping time, water fraction, and the formwork’s stiffness and sealing exerted a strong influence on the final geometry. A subsequent series, therefore, revisited the geometry set with improved boundary control: more robust, sealed formwork was used, water fraction and age were bracketed around the preferred green-state, and contact duration was standardized or explicitly varied to separate material effects from operational ones.

3.1.8. Experimental Design and Parameters Studied

This section examines how age (50 vs. 130 min), water fraction (10% vs. 15%), and a short-duration external vibration (exactly 1 min or 3 min) affect stamping load and dimensional fidelity for four geometries (cone, truncated pyramid, hemisphere, truncated cone) at a nominal feature height of 10 mm. After stamping, imprints were 3D-scanned and rigidly registered to CAD; signed scan-to-CAD deviations in height () and diameter/width (/) were extracted (measured minus CAD; negative indicates underfill). The parameter matrix is given in Table 11. Loads cluster by green-state rheology: younger, drier mixes (50 min, 10%) give the highest reactions (e.g., C.6, C.7); older, wetter mixes (130 min, 15%) the lowest (C.5, C.11); and mixed cases are in between (C.4, C.8, C.12). By geometry, cone is balanced (height near target, modest lateral growth, aided by aging); truncated pyramid keeps height tight but its lateral size is mix-sensitive unless boundaries are firm; hemisphere is laterally forgiving (often slightly negative ) with small height error; and truncated cone is height-sensitive (underfill without sufficient mobility or a short vibration) and shows the widest scatter in width.

Table 11.

Parameter matrix for the second geometry study (C.1–C.12). Vibration is the duration of an external vibration applied after seating (exactly 1 min or 3 min).

Vibration and Boundaries

A 3 min external vibration often improves seating and air release—and thus fidelity—provided the formwork is rigid and well sealed; with soft or gapped boundaries, the same vibration can amplify lateral spread. Importantly, the benefit is geometry- and mix-dependent: as summarized in Table 9, the cone shows a slight worsening of mean height error under 3 min vs. 1 min ( mm) despite better lateral conformity, whereas truncated shapes tighten laterally without a height penalty, and hemispheres show small gains. Note that the 1 vs. 3 min sets are not fully balanced in age/water; therefore, the vibration contrast should be read as a trend, not a full factorial test. In short, rheology sets what is achievable, while boundary stiffness and controlled vibration determine whether that potential yields crisp edges and correct dimensions.

Integrated Interpretation

Lower water/earlier age increase load but improve shape-holding; at fixed water, later age improves height control for axially sensitive shapes (cone, pyramid) but does not by itself curb lateral spread in wet mixes; geometry governs the trade-off—hemispheres are laterally safe, truncated cones need attention to height underfill, and truncated pyramids require lateral control at high water/late age.

Quantified Influence of Vibration (3 min vs. 1 min)

Mean absolute errors (mm; per group) indicate where 3 min helps most: cone— improves (0.63→0.35) with a slight height overshoot (0.75→1.02) in some wet/late cases; truncated pyramid—lateral size tightens markedly ( 1.32→0.53; 0.85→0.77) while height remains tight; hemisphere—a small reduction in height (0.28→0.20) and a mixed effect in diameter (0.78→0.54); and truncated cone—height and lateral both improve ( 0.63→0.33; 0.93→0.55; 0.97→0.77). Note: the 1 min and 3 min sets are not fully balanced in age/water; treat the vibration contrast as a trend, not a factorial test.

Mechanistic Note (1–3 min Vibration)

A minute-long vibration provides sustained microshear that expels entrapped air and breaks static interfacial friction and early thixotropic structure, temporarily lowering the apparent yield stress at the tool–mortar interface. As a result, the insert seats fully and contact distribution becomes more uniform, reducing lateral error—especially for truncated shapes—while the overall reaction changes only marginally. The parameter matrix for the second geometry study (C.1–C.12) is given in Table 12.

Table 12.

Condensed error summary from C.1–C.12. Values are mean absolute deviations (mm, lower is better), averaged over six distinct test conditions with exactly 1 min or 3 min external vibration ( per condition; six conditions per group). Lateral error uses diameter for cone/hemisphere and diameter+width for truncated shapes.

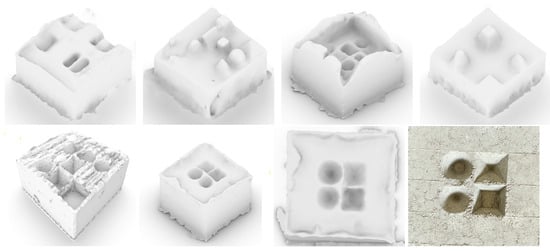

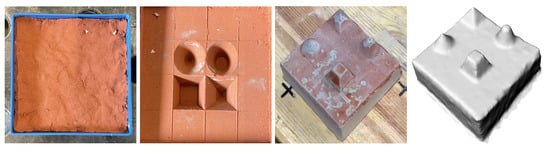

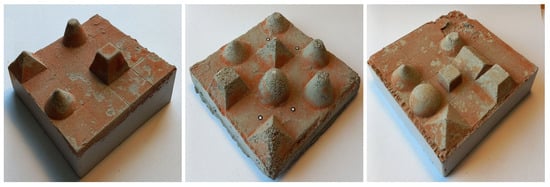

3.1.9. Alternative Stamping Approach Using Soft-Soil Molds

As discussed in the parameter-tuning study (age, water, vibration, and formwork), small but persistent deviations in height and diameter/width were observed in direct concrete stamping. To address this, a reversible-mold route was introduced using soft, oil-treated fine sand as the imprint medium (Figure 15). In the first step, the 3D-printed stamp is pressed into the soil to form a clean negative; in the second step, fresh concrete is placed or sprayed into this cavity (e.g., shotcrete). After sufficient curing, the soil is simply removed, releasing a positive replica with markedly improved geometric fidelity (see Figure 16). Early trials with the soil-based mold showed precise transfer of intricate details and stable edges. The soil’s plasticity distributes contact pressure during casting, cushions minor volume changes during hydration, and reduces frictional locking at demolding. Once the concrete has set, the soil can be brushed or washed out of the dry-joint features, revealing sharp, well-formed profiles. This approach therefore offers a practical alternative when direct stamping is limited by timing tolerances, adhesion during withdrawal, or boundary compliance (see Figure 17). “Soft-soil’’ here denotes oil-treated fine sand (not clay/loam); the minimum adequate oiling to avoid contaminating concrete surfaces that must later bond should be used. The minimum oil needed to avoid contaminating bond-critical concrete surfaces. Place the sand bed in a rigid frame, level it, and lightly pre-moisten/compact to stabilize the cavity walls—especially for spray placement. For shotcrete, adjust standoff and pressure to prevent erosion of the sand cavity. Where impact is severe, low-head pouring is preferred. Note that very slender or deep negatives may slump; adding a small draft or casting in stages improves stability and release. The sand can be sieved and reused, the oil treatment can be refreshed as needed, and the waste can be managed responsibly.

Figure 15.

Process of forming concrete geometries using oil-treated fine sand as a mold material. From left to right: (1) the prepared soft-soil surface, leveled and compacted with fine aggregate; (2) stamped impressions made using 3D-printed geometries; (3) concrete cast within the soil mold using either manual pouring or shotcrete application; and (4) final hardened concrete piece after soil removal, showing minimal deformation and high geometric precision. This method allows for clean release and accurate reproduction of detailed features.

Figure 16.

Examples of concrete elements produced by the soil stamping technique, demonstrating high geometric fidelity for various shapes, including pyramids, hemispheres, and truncated cones.

Figure 17.

Detailed views of surface-formed elements produced via the soil-mold method, highlighting edge quality and feature fidelity.

3.2. Green-State Milling

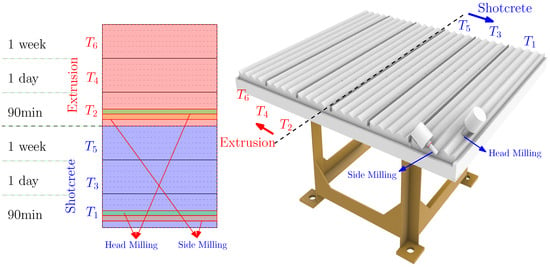

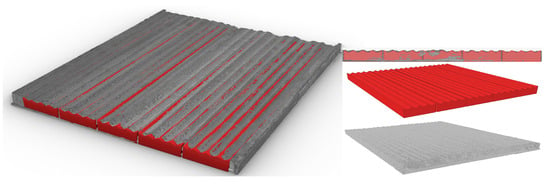

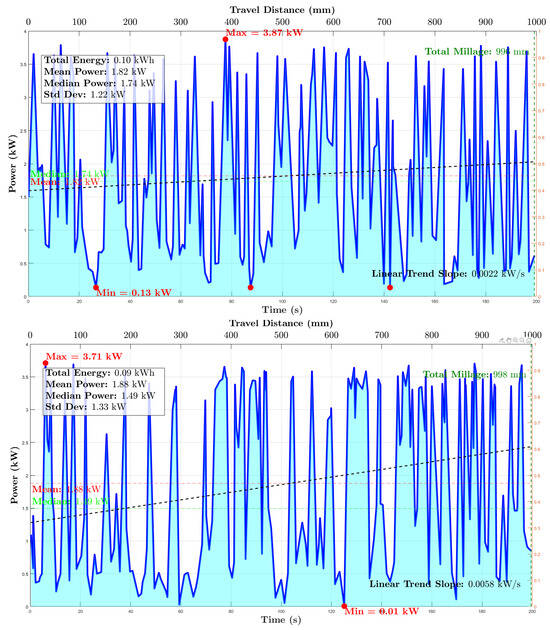

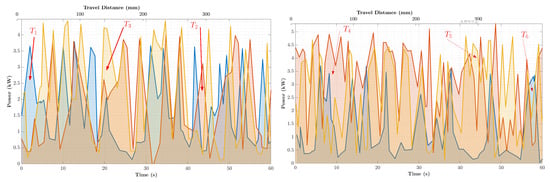

Subtractive CNC milling is among the most capable methods for forming precise, interlocking geometries for dry concrete connections; however, its cost and cycle time in fully hardened concrete are substantial. To mitigate milling load, tool abrasion, and energy demand, this study investigates green-state milling—i.e., machining during early-age curing—using a trapezoidal interlock profile as a case geometry. Three process factors were examined: material age at machining (90 min, 1 day, 1 week after printing), printing route of the substrate (shotcrete vs. extrusion), and tool orientation (end milling vs. peripheral/side milling). The primary responses were (i) scan-to-CAD geometric accuracy of the milled profile, (ii) post-run tool abrasion as an indicator of abrasive interaction, and (iii) electrical energy and cycle time required per cut. The experimental layout is shown in Figure 2. Each printed panel was partitioned into three equal regions, yielding six test divisions in total : three for the extrusion route and three for the shotcrete route. A dedicated rough diamond tool was assigned to each division so that cumulative abrasion could be attributed unambiguously to the corresponding substrate route and age; abrasion was recorded after completion of the division’s cuts. Although the same printable concrete (nominal at 28 days) was used for all specimens, both extrusion and shotcrete were employed to produce machining stock with different as-printed textures and internal porosity, enabling a comparison of substrate response to milling at early ages. All printing and milling were performed at the DBFL, TU Braunschweig, using separate robotic gantries for deposition and machining. The CAD geometry of the dry connection was modeled in Rhino 3D and transferred to EasyStone, along with the fixturing table and specimen volumes, to enable collision checking and kinematic simulation. Using the DBFL tool library, the CAM workflow generated six near-identical programs with spatial offsets corresponding to the test divisions. After post-processing, the programs were executed on the robot controller; for each division, milling duration and electrical energy consumption were measured and logged individually to support subsequent analysis of process efficiency. An overview of the milling sequence in the DBFL setup is provided in Figure 18. Representative photos of the in-process cuts on shotcrete and extrusion at one week are shown in Figure 19. Using the DBFL tool library, the CAM workflow generated six spatially offset programs (G-code) corresponding to the test divisions. Each milling condition T1–T6 (defined by printing route and age) was executed once ( per condition); the section-wise statistics D1–D3 are derived from multiple cross-sections of the same scan and represent intra-specimen variation rather than independent repeats.

Figure 18.

Milling workflow: (left) EasyStone-programmed toolpath for the trapezoidal profile; (middle) fixtured concrete block on the CNC table; (right) in-process cut on an extrusion specimen.

Figure 19.

Milling of green-state specimens (extrusion and shotcrete) under test conditions T1 and T4.

3.2.1. Tool Abrasion in Green-State Milling

Milling kinematics were kept constant within the series (nominal traverse setpoint and a spindle speed of 4200 rpm); for traceability, the logged path length and duration were recorded for each orientation. Because the contact mechanics of the two orientations differ, the traversed distance also differed between orientations: the side-milling path per run covered approximately (about ), while the head-milling path accumulated longer travel (documented at ∼18.7 m). The corresponding average CNC durations were about 400 s for the side pass and 930 s for the head pass. Abrasion was quantified as the circumference loss (mm) of the tool’s rough-diamond rim, measured with a digital caliper near the end face (head engagement) and on a mid-height circumferential band of the flank (side engagement) (see Figure 20). For reference, the nominal pristine rim had a circumference (≈20 mm diameter); the equivalent diameter loss is . All milling tests used a 20 mm rough-diamond milling tool mounted on a five-axis robotic spindle at a fixed speed of 4200 rpm and a programmed traverse feed of 1200 mm/min. The CAM strategy employed linear toolpaths with constant step-over and step-down values and identical safety clearances across all tests, so that differences in response arise from material age and printing route rather than kinematic changes. Six nominally identical tools were used in total, one per scenario; tool IDs T1–T6 are mapped one-to-one to the milling scenarios T1–T6 listed in Table 13 and Table 14, and each tool was only used for its corresponding test set.

Figure 20.

Circumference-loss measurements for T1–T6 plotted separately for head (end face) and side (flank band), contrasting shotcrete and extrusion routes. Measurements by digital caliper; initial rim circumference mm.

Table 13.

Measured tool abrasion as circumference loss (mm) at the head (end face) and side (flank band) for different substrate ages and printing routes. Each tool (–) was used for one run. Measurements by digital caliper; initial circumference (≈20 mm diameter).

Table 14.

Electrical energy per unit tool path length and measured head circumference loss for the six milling scenarios T1–T6. The total programmed tool path per test was m (identical G-code for all cases).

Three trends emerge from Table 13. First, head engagement consistently produced greater wear than side engagement, reflecting higher specific contact pressures and less favorable chip evacuation at the end face; for example, at the late-age extrusion condition (), the head loss reached (equivalent ) versus on the flank. Quantitatively, at one week, the measured circumference loss at the head was mm for shotcrete (tool T5) and mm for extrusion (tool T6), whereas the corresponding flank losses were only about mm and mm, respectively (Table 13); in this test series, the head passes therefore caused roughly three times the total circumference loss of side passes. Second, abrasion increased with material age: comparing very early shotcrete (–) to day-scale and week-scale cases (T3–T4, T5–T6) shows a clear rise, consistent with rapid stiffening and higher milling load outside the earliest green-state. Third, extrusion-printed stock tended to be more abrasive than shotcrete at comparable ages (cf. T3 vs. T4), in line with differences in as-printed surface texture and internal compaction. These abrasion trends map directly to geometric fidelity and process economics: elevated head wear correlates with faster loss of edge definition in end-milled features and with longer cycle times due to tool changes; conversely, scheduling tolerance-critical cuts early in the green-state and favoring side engagement where feasible can reduce both wear and energy per unit geometry. Note: even when normalized by travel, head wear remains higher (e.g., T6 rates vs. for head vs. side).

3.2.2. Tool–Abrasion Trends

Effect of aging (time). For the shotcrete route (T1, T3, T5), head wear increases monotonically with age, from mm (T1) to mm (T3) and mm (T5). For the extrusion route (T2, T4, T6), the same rising trend is observed: mm at the head, with the side (flank band) also increasing ( mm). This behavior is consistent with progressive stiffening and higher specific cutting forces as curing progresses beyond the earliest green state. The effects of milling orientation and exposure are as follows. Head engagement consistently produces more wear than side engagement due to higher contact pressures and less favorable chip evacuation at the end face. Exposure also contributes: the documented head path length per run was ∼18.7 m (about 930 s) versus ∼7.9 m (about 400 s) for the side at the same traverse setpoint. Even when normalized by travel, headwear remains higher (e.g., at T6: mm m−1 vs. mm m−1 for the side), confirming an actual orientation effect beyond exposure. Taken together, abrasion is governed by (i) engagement mode and exposure (head > side), (ii) curing progression (later > earlier), and (iii) printing route (extrusion > shotcrete at comparable ages). For planning, the measured circumference loss (mm)—obtained by digital caliper on the tool’s rough-diamond rim—offers a compact estimator of tool life. The pristine rim circumference was mm (≈20 mm diameter); if needed, the equivalent diameter loss is . Schedule tolerance-critical passes earlier in the green state, and side engagement is preferred where edge quality permits to reduce wear and energy per unit of geometry.

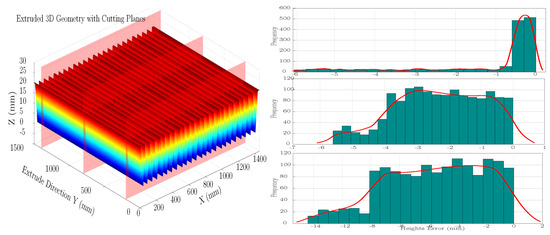

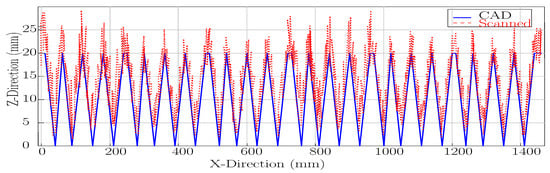

3.2.3. Geometric Evaluation of Milled Profiles

After milling, the point cloud of each division was aligned to the reference CAD model that had been used in EasyStone to generate the G-codes. Registration and deviation mapping were performed with CloudCompare (rigid ICP) and custom MATLAB-R2023a routines, yielding signed point-to-surface distances and section-based dimensional differences. Scalar deviations were extracted as (feature height) and (feature width) from reference sections (measured minus CAD). For each division, the workflow comprised scan preprocessing (trimming edge artifacts, downsampling, and outlier removal), best-fit rigid registration to CAD, and extraction of scalar deviations and from reference sections. Representative outputs—milled surfaces, robotic setup, surface profilometry, and the corresponding error analysis—are illustrated in Figure 21. A triangular interlock was adopted as the principal study shape because it can be machined by both end milling (head engagement) and peripheral milling (side engagement). This allowed for a direct comparison between subtractive routes and facilitated a faster construction path for high-capacity joints observed in preliminary tests. Earlier production of dry connections at DBFL used the same milling technology and fixturing, but with a more elaborate, multi-step preparation: smooth pre-cuts, a robust clamping strategy, and precise calibration of the milling coordinate system to the raw concrete stock. When time permitted, these steps, the milled quality was high and geometric errors were limited, as evidenced in Figure 21. In green-state milling, such exhaustive preparation was intentionally curtailed to respect the short processing window. Additive manufacturing of the stock by shotcrete and extrusion introduced additional metrological challenges. As-printed surfaces are uneven, and edges are rounded; even after light post-processing, they lack the sharp datums typically used to reference and calibrate the workpiece. The MATLAB pipeline implemented this: CAD sections were imported and scaled; scan lines at fixed y were extracted and shifted by calibrated offsets; a nearest-neighbor match to the CAD section was formed over a restricted x-range; and pointwise errors were computed. The script produced an overlay of scan and CAD, the distribution of selected matches, bar plots of annotated with mean-squared error (MSE) and root-mean-squared error (RMSE), a histogram with normal fit, and absolute-error profiles across the width. Altogether, this process provided a reproducible basis for quantifying milling accuracy by division, printing route, and age, while acknowledging the deliberate trade-offs in fixturing and calibration imposed by green-state timing.

Figure 21.

Milling process and accuracy evaluation: examples of milled concrete geometries, robotic milling setup, 3D surface profile measurement, and corresponding dimensional error analysis with a standard deviation of 0.20 mm.

Two operational choices during green-state milling measurably affected geometric quality. First, for the earliest cuts (T1, T2), the internal tool-cooling circuit remained active, but surface splash was intentionally disabled to avoid washing the fresh mortar; in subsequent divisions, the surface spray was restored. Second, because milling started immediately after printing, no preliminary surfacing or datum preparation was performed. As-printed substrates, therefore, retained uneven roughness and slightly rounded edges, which impeded precise workpiece calibration and the reliable transfer of the exact geometry into the CAM environment. Immediate pre-milling scanning can mitigate both the lack of a clean datum and the small global slope via plane-fit compensation. But in the present series, the combination of rough skins and a slight global slope across some divisions limited the attainable referencing accuracy even on a leveled printing table. Both effects—lack of a clean datum and small but finite tilt—propagated into the final milled geometry.

To resolve the non-uniformity observed along the length of each division, the registered point clouds were compared to the CAD model in three longitudinal sections for each milling schedule (D1(), D2(), D3()). Figure 22 shows the 3D scan overlaid on the CAD reference with deviation coloring, while Figure 23 illustrates the perpendicular milling planes and the extracted cross-section traces used for sectionwise analysis. The statistics reveal a clear gradient in accuracy: section D1 exhibited the largest deviations, with a mean error and standard deviation , and a broad distribution indicative of variable local engagement and referencing drift. Section D2 improved markedly to and , with tighter clustering and fewer outliers, while D3 lay between these two, at and . The surface topology in Figure 23 corroborates these findings: periodic scallop patterns from the tool path are superimposed on a gentle planar tilt, and localized peaks align with the larger errors seen in D1. The labels X and Y follow the local DBFL convention and were chosen only to constrain the portal to move along a single axis for sectioning; they do not carry any energetic or other physical meaning (the choice avoids coupled motor motion and simplifies analysis) (see Figure 24).

Figure 22.

Three-dimensional scans of the entire milled concrete surface, compared with the corresponding CAD model, highlighting deviations and matching areas.

Figure 23.

Comparison of the CAD reference geometry with the measured milled surface profile, showing deviations across multiple cross-sections and the overall 3D surface topology.

Figure 24.

CAD–scan comparison along sampled sections: blue = CAD reference profile, red = 3D-scan profile of the milled element. Plots show Z vs. X along sampled toolpaths; deviations indicate residual waviness and local over/under-cut.

A comparative view across printing routes underscores the same mechanisms. For an extrusion-based specimen, the mean error was approximately with a maximum deviation near , whereas a shotcrete-based specimen before recalibration showed a substantially larger mean of about and maxima approaching . After coordinate refinement on a second shotcrete scan, the mean tightened to with a reduced maximum of , indicating that part of the excess deviation arose from referencing (calibration) rather than milling alone. The residual spread is consistent with the combined influence of the global slope, surface roughness of the as-printed skin, and the absence of a preparatory surfacing pass—factors that are amplified when surface splash is disabled at a very early age. Together, these results show that while acceptable accuracy is achievable in green-state milling, uniformity along the workpiece remains sensitive to datum definition. Incorporating a rapid pre-scan and plane-fit compensation, where timing permits, materially improves section-wise conformity to the CAD files.

3.2.4. Energy Consumption