Abstract

The transmission tower-line system is subjected to long-term loads such as wind and ice, and the instability of the tower leg angle steel is one of the key factors leading to collapse. This paper proposes the partially restrained reinforced angle steel member (PRR-ASM), a method used to enhance the bearing capacity of the tower leg angle steel. By combining tests and simulation analyses, the reinforcement mechanism and engineering applicability of PRR-ASM were studied. Comparative analysis was performed on the gap working conditions of PRR-ASM, and compression tests on constraint gaps (0/2/4 mm) were conducted. The bearing capacity of partially constrained specimens increased by 31%, and the yield displacement increased by 92.2%. Analysis of constraint segment length showed that length significantly affects bearing capacity, and better improvement in stability performance can be achieved with partial constraint. Based on the test and simulation results, constitutive and simplified models were established, and PRR-ASM was applied to vulnerable members of the tower-line system. A two towers and three lines coupled model was constructed to analyze the structural failure mechanism. The results show that under the most unfavorable wind direction, the ultimate wind speed after reinforcement increased from 25 m/s to 32 m/s, and the member safety factor increased from 1.6 to 3.4. Considering high reinforcement efficiency and low economic cost in engineering, the gap-free, partially constrained scheme is recommended for engineering practice.

1. Introduction

Long-distance transmission lines often span different geographical and climatic regions. Therefore, they are susceptible to external excitation from strong winds [1,2]. Transmission towers are the key load-bearing structures of transmission lines. Under the influence of strong winds, if a transmission tower collapses, the transmission line may be disconnected, potentially leading to power outages and huge economic losses [3,4]. Therefore, transmission towers need to have sufficient safety margins in severe weather conditions. In recent years, after adjustments to load design specifications, many old transmission towers have been unable to meet operational requirements. They need to be retrofitted to enhance their load-bearing capacity and ensure stable operation.

In response to the need for optimizing the wind resistance performance of transmission towers, some researchers have proposed various reinforcement schemes and verified them through experiments. The general idea behind these schemes is to increase the moment of inertia of the angle steel section by attaching reinforcement components [5,6,7,8,9]. Technically, this often involves the use of bolt joints [10,11], welding [12], and clamps [13,14,15]. However, some of these methods involve reinforcing angle steels by drilling holes in the original components, which can cause additional damage to the original structure [16]. Liang et al. [13] used clamp reinforcement technology to strengthen the legs of transmission towers and proposed a load-bearing capacity prediction model through experiments and simulations. Liu et al. [15] proposed a clamp reinforcement technology for the main legs and oblique rods of transmission towers. However, this clamp adopts a full-length reinforcement method, which can significantly increase the elastic stiffness of the components and potentially cause damage at the connection points.

In terms of reinforcement schemes, the concept of the buckling-restrained brace (BRB) has been applied to angle steels. Sun et al. [17] introduced a rectangular angle steel sleeve buckling-restrained technology to enhance the stability of towers. The effectiveness of this technology in slowing down the degradation of compressive strength was verified through full-scale experiments and simulations. Zeng et al. [18], inspired by the idea of buckling-restrained braces, proposed a buckling-restrained reinforcement method to improve the stability of existing tower legs. The feasibility of this method was verified through experiments and numerical analysis. However, these methods all adopt overall length reinforcement without discussing partial length reinforcement methods.

In summary, most existing reinforcement methods for enhancing the wind resistance of transmission towers involve full-length reinforcement. These methods are challenging and unsafe to implement in high-altitude environments and can compromise the integrity of the components. Furthermore, current research primarily focuses on reinforcement methods applied directly to components, lacking a comparison of different reinforcement methods under various reinforcement gaps. To address these limitations, this study proposes a partially restrained reinforcement measure that enables the non-destructive and continuous reinforcement of angle steel components. Additionally, it introduces the degree of improvement in the wind resistance performance of transmission towers after PRR members.

To enhance the overall stability of such components, this paper proposes a novel partially restrained reinforced angle steel member (hereinafter referred to as PRR-ASM). This reinforcement scheme adopts a local reinforcement form, which significantly improves the bearing capacity and yield displacement of angle steel. In the following sections, PRR-ASM is first described in Section 2. To compare the effectiveness of different reinforcement schemes, axial compression tests were conducted as described in Section 3. In Section 4, based on the test results, the performance of the proposed PRR-ASM was analyzed. In Section 5, numerical simulations were performed on PRR-ASM to study the action mechanisms of PRR-ASM with and without gaps. In Section 6, a second group of tests was designed to study the influencing factor of constraint length, and a simplified model was proposed based on the test results. Finally, the transmission tower-line system using the proposed PRR-ASMs was modeled, and the finite element results were analyzed in Section 7.

2. Basic Idea and Configuration of PRR-ASM

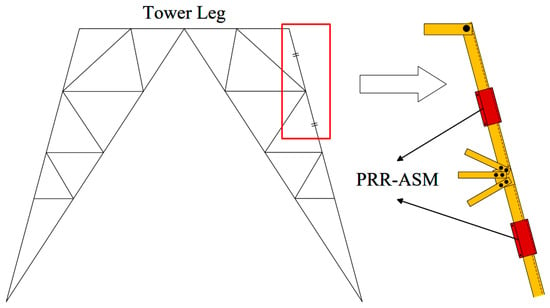

The basic idea of PRR-ASM is derived from buckling-restrained braces (BRBs), involving a modification of the restraining component inspired by the BRB concept. This reinforcement form is particularly beneficial for the reinforcement of transmission tower angle steel, as shown in Figure 1. Firstly, it is an economical reinforcement scheme with less material consumption, and it is also a non-destructive reinforcement form. Secondly, it reduces the additional mass of the angle steel, making it less likely to exceed the design bearing capacity of the original tower. Finally, it weakens the stress redistribution effect after reinforcement, making the stress distribution more reasonable.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of reinforcement of transmission tower legs. The red segment is the constrained segment, and the yellow segment is the original angle steel.

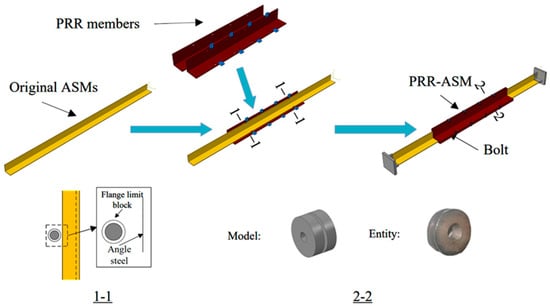

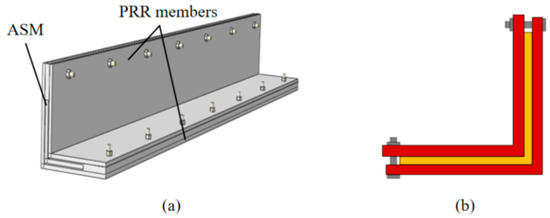

Partial restraint reinforcement (PRR) is applied to angle steel members (ASMs), namely PRR-ASMs. This is a modification scheme for existing ASMs, as shown in Figure 2. First, PRR members are installed on the inner and outer sides of the original ASM through flange limit blocks, forming the section shown in Section 1-1 of Figure 2. The middle grooves of the flange limit blocks contact with the flange of the angle steel, facilitating control of the gap between the ASM and the PRR members. The flange-limiting clamp block is shown in Section 2-2 of Figure 2. No notch needs to be machined on the ASM, achieving true non-destructive reinforcement.

Figure 2.

Retrofitting scheme for the proposed PRR-ASM.

The PRR member is made using angle iron and has slightly larger dimensions than the original ASM. The PRR member is positioned in alignment with the existing ASM, typically at the center of the member’s longitudinal axis. The PRR member is connected to the ASM using a flange limit block, which is secured with bolts. Bolts and nuts are made of ordinary materials, depending on the thickness and location of the reinforced specimen.

The key difference between PRR-ASM and traditional full-length constraint reinforcement lies in its partial constraint mechanism and non-destructive construction process. Although full-length reinforcement methods increase overall stiffness, they usually cause stress concentration at connections and are difficult to install on in-service towers. PRR-ASM allows for the control of deformation and force redistribution by applying constraints only to the critical parts of members, avoiding the creation of new structural weaknesses. The bolted modular design of PRR-ASM enables quick installation in high-altitude environments without welding, greatly reducing construction time and risks.

This section aims to verify the mechanical performance of the PRR-ASM reinforcement scheme under axial loads by conducting tests based on key influencing factors. According to the key influencing factors, the operating conditions of the test specimens are divided into three categories: The first is the gap d between the PRR member and ASM; the second is the length l of the PRR member; and the third is the material type between the PRR member and ASM. Based on the above working conditions, the designed experiment aims to compare the reinforcement effect by using two key performance indicators. The first is the change in the bearing capacity of the components before and after reinforcement, and the second is the change in axial displacement under unstable loads before and after reinforcement.

3. Compression Tests Considering the Influence of Gaps

To obtain the ultimate bearing capacity and strain of PRR-ASM, a series of compression tests were conducted based on relevant studies [19,20]. The experimental methods and parameters were introduced.

3.1. Specimen Details

First, we determined the size of the ASM specimen. The ASM specimens were made of the steel angle L20 × 3. According to the “Code for Design of Steel Structures” (GB50017-2017) [21], the aspect ratio of compression members shall not exceed 150. Considering the need to compare the performance of PRR-ASM with the spatial constraints of experimental equipment, we set the aspect ratio of the non-restricted ASM specimens in this experiment to 140, as shown in Table 1 (specimen U).

Table 1.

Detailed geometric parameters of the specimens.

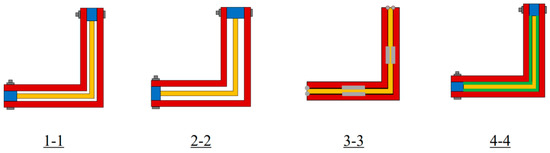

Then, the BRR scheme was determined. Considering the cross-sectional form, if the gap between the core member and the constraining member is excessive, it will cause a sudden change in bearing capacity and excessive weight of the constraining member, which is unfavorable to the overall performance of the support. Therefore, three types of gaps were set: 2 mm, 4 mm, and 0 mm. The main comparison conditions for Sections 1-1, 2-2, and 3-3 in Figure 3 are the core gap sizes. Among them, the 0 mm gap uses spot welding between ASM and PRR members, as shown in Section 3-3 of Figure 3. The comparison conditions for Sections 1-1 and 4-4 in Figure 3 are the gap material between the core and the constraining member. The gap between ASM and PRR members is filled with rubber and plastic materials. Sample numbers and main parameters, with a total of 12 designed, are shown in Table 1. The material properties of the samples are shown in Table 2. When manufacturing ASM and PRR members, the dimensional tolerance of the angle steel legs and gap surfaces is ±0.1 mm. This ensures consistency between the specimens.

Figure 3.

PRR-ASM specimen schematic diagram. The yellow members represent the original ASM. The red members are BRR members. Green members are filling materials.

Table 2.

Material properties of the steel members.

3.2. Test Setups

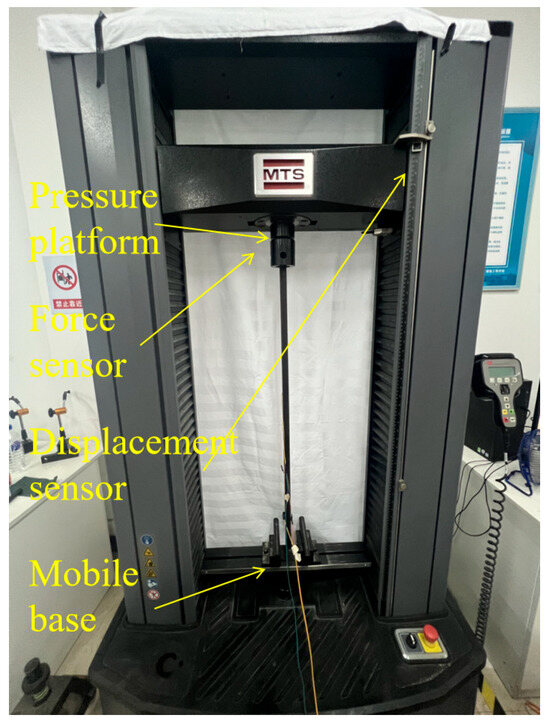

The experimental equipment used a 100 kN MTS electro-hydraulic servo testing machine from the Transmission Engineering Laboratory of NEEPU, as shown in Figure 4. The testing machine was configured for axial static loading. Given that the boundary conditions used in this study employed a dual fixed end contact loading system, the following specifications were determined based on laboratory testing machines: the upper end of the ASM specimen was welded with a circular gasket (20 mm radius, 3 mm thickness), and the lower end was welded with a square gasket (60 mm side length, 3 mm thickness), both made of thin iron. The upper contact surface of the testing machine was a cylindrical barrel, and the lower surface was smooth. Custom movable bases were designed and bolted to the testing machine. The MTS end near the loading point was designated as the upper end: the upper part of the ASM specimen was placed into the circular hole designed for the MTS, and the lower end of the ASM specimen was clamped by the two ends of the movable bases, ensuring a double-fixed end loading configuration and pure axial load application.

Figure 4.

Photo of the testing device for PRR-ASM specimens.

Loading was displacement-controlled at a rate of 0.05 mm/s, with a data acquisition frequency of 20 Hz. A pre-load force of 10 kN was applied to ensure tight contact between the specimen and the press. Load and displacement data were collected using the testing machine’s built-in force and displacement sensors, as shown in Figure 4. The data acquisition system operated at a frequency of 2 Hz. Two physical quantities were collected: specimen displacement and specimen bearing capacity.

4. Analysis of Gap Influence Based on Test Results

In Section 3, considering the effect of the gap, compression tests were conducted on PRR-ASM. Based on the test phenomena, this section analyzed the test results of PRR-ASM. First, the failure modes of PRR-ASM specimens are studied. Second, the working mechanism of PRR-ASM is analyzed based on the bearing capacity and stability performance of the specimens. Finally, the reinforcement effect of PRR-ASM is quantitatively analyzed.

4.1. Failure Mode for the Specimens

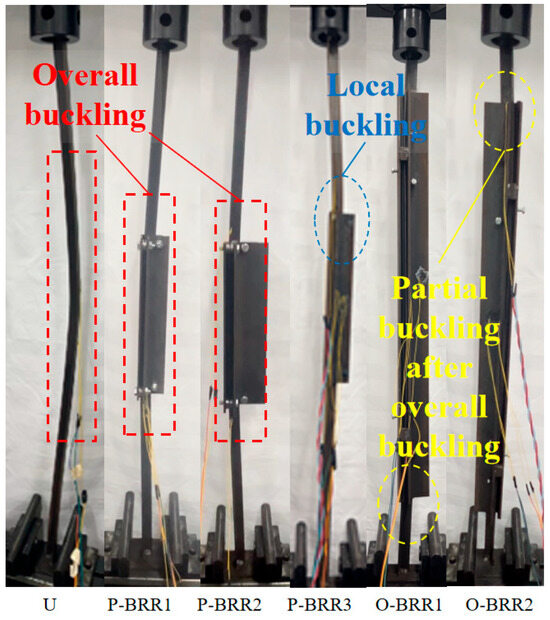

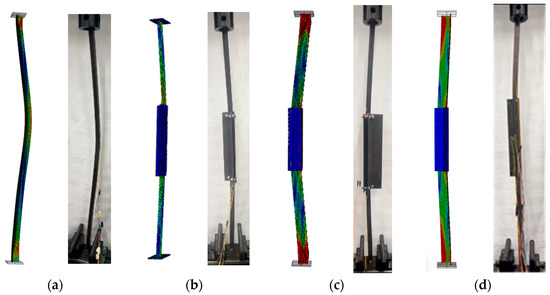

The failure modes of each specimen and the test results are presented in Figure 5 and Table 3, respectively.

Figure 5.

Photos of failure modes of each test specimen.

Table 3.

A summary of failure mode and location for all PRR-ASM specimens.

Since PRR specimens have sufficient stiffness and strength, all restrained specimens are in the elastic stage. It can be seen from Table 3 that all specimens exhibited three failure modes in total, among which Failure Mode 1 belongs to the local flexural buckling of PRR-ASM specimens. It can be seen from Figure 5 that P-BRR3 with welding reinforcement belongs to this failure mode. Under axial force, this method is equivalent to a stepped column under axial compression. The reinforced position has a larger cross-sectional area and higher stiffness, but the welding joint is a weak point compared to other parts, making it prone to local instability.

Failure Mode 2 involves PRR-ASM specimens experiencing global instability with local flexural buckling at specific locations. O-BRR1 and O-BRR2 fall into this failure mode. With the increase in axial compression, the ASM specimen undergoes global buckling, but the PRR specimen restricts the displacement of the ASM specimen. Contact occurs at the junction between the PRR and ASM specimens, leading to local buckling. Consequently, the instability bearing capacity of the angle steel decreases.

Failure Mode 3 is that PRR-ASM specimens undergo global instability. As shown in Table 3, P-BRR1 and P-BRR2 exhibit this failure mode. This indicates that, due to the large slenderness ratio of ASM specimens, with the increase in axial compression, the ASM specimen undergoes global instability, and the short length of the PRR specimen fails to achieve the effect of preventing the displacement of the ASM specimen.

4.2. Displacement Bearing Capacity Analysis of PRR-ASM

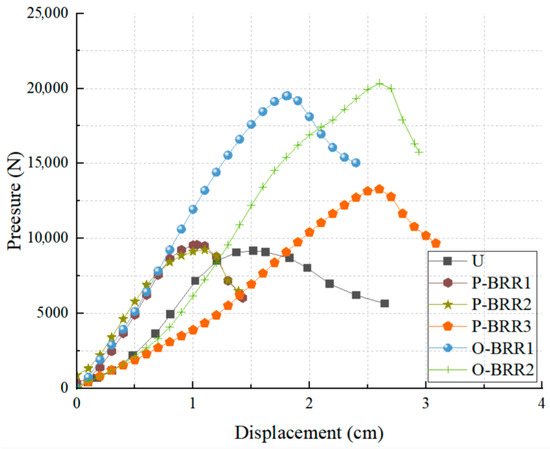

During the axial force loading test, the axial displacement-load variations in PRR-ASM specimens were recorded. The pressure axial displacement curve of the six specimens is plotted in Figure 6. In the figure, the x-axis represents the axial displacement of the specimens in cm; the y-axis represents the pressure exerted at the centroid of all PRR-ASM specimens in N. The global buckling strain and final strain improvement rate are listed in Table 4.

Figure 6.

Displacement–pressure curve of PRR-ASMs.

Table 4.

Improvement rate of ultimate pressure and ultimate yield displacement of test specimens.

As shown in Figure 6 and Table 4, F-BRR3 exhibits the best capacity performance, while H-BRR2 has the worst. P-BRR3 has the largest yield displacement under ultimate bearing capacity. All specimens reached ultimate bearing capacity in the elastic stage, consistent with the test expectations. The yielding of PRR-ASM is caused by global stability. Next, separate comparisons will be conducted based on the working conditions designed in Section 3.1.

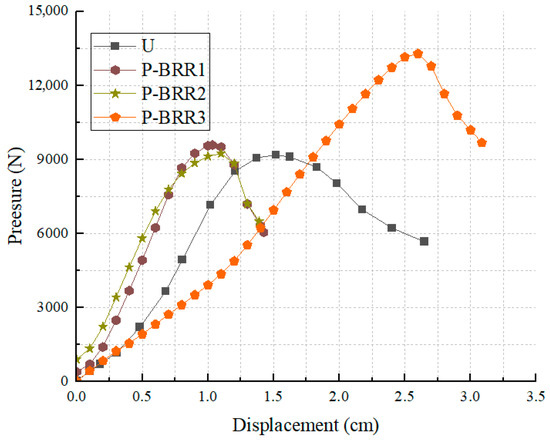

Considering the influence of gap d, based on the unique variation condition of the gap size, the pressure–displacement curves under three types of gaps were compared. As shown in Figure 7, the partial reinforcement scheme comparison reveals that P-BRR3 with a 0 mm gap has the best bearing capacity and the optimal ultimate yielding displacement improvement rate. Therefore, the 0 mm gap in the P-BRR group is optimal.

Figure 7.

P-BRR group comparison chart under gap influence.

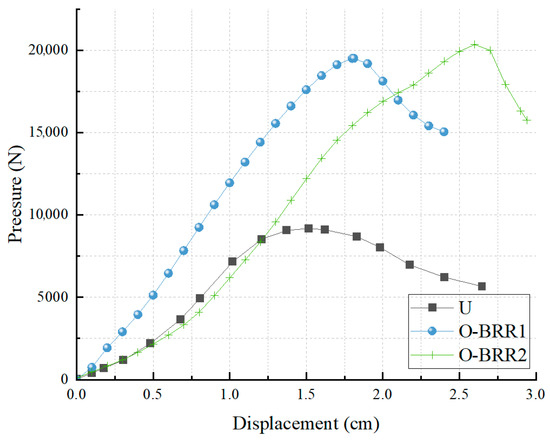

The influence of materials between PRR members and ASM is shown in Figure 8. O-BRR2 has a higher bearing capacity than O-BRR1, proving that for PRR-ASM under the condition of having a gap, filling the gap with softer materials yields better effects. In terms of the improvement rate of ultimate yield displacement, O-BRR2 demonstrates the optimal enhancement effect.

Figure 8.

Comparison chart under material influence.

Based on the analysis of the above test results, PRR-ASM exhibits the best performance when the core gap is 0 mm. Moreover, a 0 mm gap achieves the goal of partial restraint reinforcement to enhance overall performance. From the test phenomena and results, it is found that when a gap exists under axial compression of PRR-ASM, the ASM first undergoes global buckling, and the PRR members come into play, changing the failure mode of the PRR-ASM component from direct global buckling to secondary global buckling in the unreinforced section. This is different from the case with a 0 mm gap. However, the comparison of this testing phenomenon is not significant. Therefore, numerical simulations were designed for analysis in Section 5.

5. Numerical Analysis of Gap Influence

In Section 3 and Section 4, although this study completed six sets of tests, it cannot cover all actual engineering working conditions due to limitations in resources and time. To systematically analyze the effectiveness of PRR-ASM, this chapter uses finite element simulation: first, an ABAQUS solid model is constructed based on test parameters, and model reliability is verified through test simulation comparison. Subsequently, an in-depth study of the action mechanism of the core is conducted under the conditions of PRR-ASM with and without gaps. All design parameters during model construction are strictly calculated with reference to the actual test data.

5.1. Validation of Finite Element Model

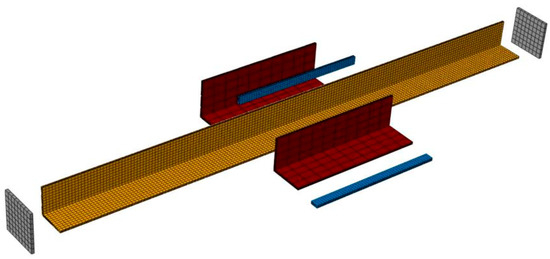

The structural composition of PRR-ASM includes core angle steel, inner and outer constraint angle steels, and gaskets assembled and connected with bolts. Bolts are omitted and replaced with gaskets serving the same function, as shown in Figure 9. All components are constructed using 3D solid elements. The yield point and elastic modulus of the ASM are consistent with those from material property tests, as shown in Table 2. Constraint angle steels adopt a bilinear model, with a tangent modulus after yielding of .

Figure 9.

The entity model diagram of PRR-ASM. The yellow in the picture represents ASM, the red represents PRR members, the blue represents padding, and the gray represents end plates.

In the simulation of components with gaps, to improve model convergence, the surface-to-face contact algorithm is used in ABAQUS to define constraint reinforcement contact. The friction coefficient is set to 0.3. The bolts and bolt holes are simplified in the model. Tie constraints are used to simulate the connections between members.

For the BRR-ASM model, the mesh size of ASM is set to 5 mm, and the element size of the constrained segment is 7 mm. BRR-ASM uses the C3D8R element type, with a total of 16,422 hexahedral elements generated. All components adopt this element type to ensure computational consistency. Initial imperfections are applied to this study based on 1/1000 of the deformation of the first order buckling mode of the ASM structure.

5.2. Finite Element Analysis of Results

First, the finite element results were validated through failure modes. In the test, due to the sufficient stiffness and strength of the PRR members, none of the PRR members exhibited obvious friction marks. Comparison of failures in some models is shown in Figure 10. The numerical model and test results highly coincide in failure modes, and this phenomenon confirms the credibility of the finite element model from the perspective of the failure mechanism.

Figure 10.

Comparison of finite element and test results for partial specimens. (a) U; (b) P-BRR1; (c) P-BRR2; and (d) P-BRR3.

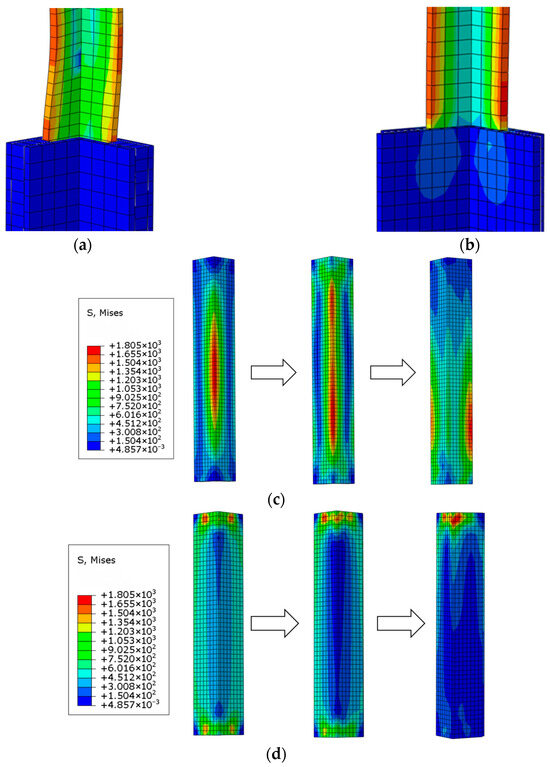

Subsequently, PRR-ASMs with and without gaps were compared. Through the stress cloud diagrams of the finite element model, it can be visually observed that, under axial compression, the two conditions exhibit different stress distributions. As shown in the test results, PRR-ASM with gaps restricts the first-order global buckling of the ASM, leading to an increase in overall capacity bearing. PRR-ASM without gaps is equivalent to local strengthening of the ASM, where the original angle steel effectively increases the cross-sectional area of part of its length, transforming into stepped section steel. A comparison of the two is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Comparison of PRR-ASM schemes with and without gaps. (a) Enlarged view of PRR-ASM connection with gap; (b) enlarged view of seamless PRR-ASM connection; (c) enlarged image of PRR members with gaps; and (d) enlarged view of gapless PRR members.

Comparing Figure 11a with Figure 11b, the local buckling position of PRR-ASM with gaps is not adjacent to the connection point between the constraint member and the core, while for PRR-ASM without gaps, the local buckling position is exactly at the connection between the constraint member and the core. Stress cloud diagrams of PRR members over time for the PRR-ASM scheme are shown in Figure 11c. ASM in the PRR-ASM scheme first undergoes global instability, causing its midsection to meet the midsection of the PRR members. Subsequently, the contact area expands. Finally, local buckling occurs near the connection between ASM and PRR members. This phenomenon corresponds to the test results and better explains the difference between the gapped reinforcement scheme and the traditional equal-section reinforcement method. Figure 11d shows stress cloud diagrams of PRR members over time for PRR-ASM without gaps. It can be seen from the figure that the flanges of the outer angle steel at both ends of the PRR members in PRR-ASM without gaps bear stress first. Then, the stress concentrates at the back of one limb, at which point local buckling occurs in PRR-ASM.

6. The Effect of PRR Member Length on PRR-ASM

The comparative analysis in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 only focuses on the gap condition. However, the influence of the constraint member length condition on the overall structural performance remains unclear. To address this issue, experimental analysis was conducted in this section. Based on the test results, a constitutive model of PRR-ASM suitable for engineering applications was established.

6.1. PRR-ASM Specimen Design and Fabrication

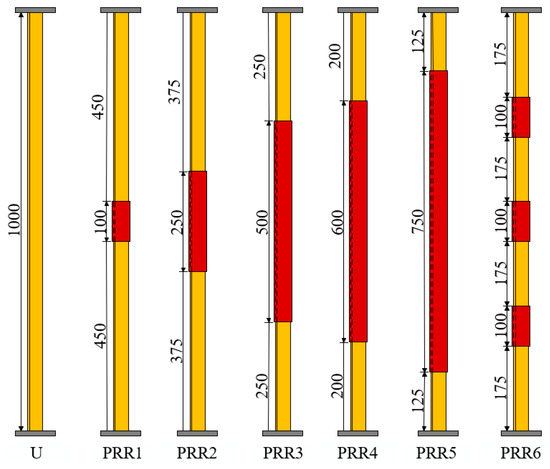

This test designed a total of seven specimens, including one original steel and six PRR-ASMs. In the specimens designed this time, the cross-sections were all set without gaps, as shown in Figure 12. The length of PRR members was studied as the only variable condition. The main comparison focused on the influence of PRR member length on the performance improvement of PRR-ASM. The PRR length (100–750 mm) was selected to cover the range from local reinforcement (10% of the member length) to near-full-length coverage (75%). If the PRR length is too small, the reinforced specimen fails to exert its effect, and the failure mode remains as the overall flexural buckling of the original steel. If the PRR length is too large, it leads to local instability at the connection between the core and the reinforcing member, and the economy is poor. The material properties of the specimens in this test are shown in Table 5, and the measurement plan and boundary conditions are consistent with those in the test of Section 3. The main parameter is the length of PRR members, as shown in Figure 13, with the length values listed in Table 6.

Figure 12.

Reinforcement method of PRR-ASM: (a) 3D model; (b) cross-sectional schematic.

Table 5.

Material properties of the steel members.

Figure 13.

PRR-ASM specimen schematic diagram.

Table 6.

Material properties of the steel members.

6.2. Analysis of Test Results

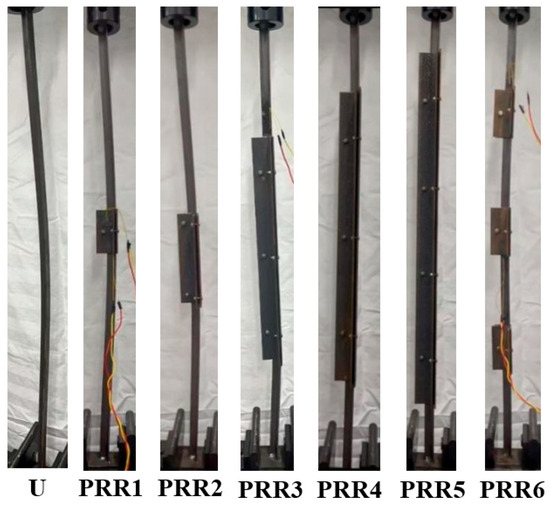

Pre- and post-test comparisons of the specimens are shown in Figure 14. After pre-loading was completed, as loading proceeded, PRR3, PRR4, and PRR5 all exhibited distinct frictional sounds, with PRR5 having the most noticeable ones. Frictional sounds occurred at approximately 70–80% of the ultimate load, coinciding with the onset of global buckling where the ASM contacted the PRR inner surface. The failure modes of U, PRR1, and PRR6 were buckling globally, with the same failure location at the midsection of the core. The failure modes of PRR2, PRR3, PRR4, and PRR5 were global buckling and local flexural buckling, with their failure locations all at the connection between the core and the constraint member. Due to the large slenderness ratio of the components, none of the specimens exhibited torsional phenomena.

Figure 14.

The destructive form of PRR-ASM.

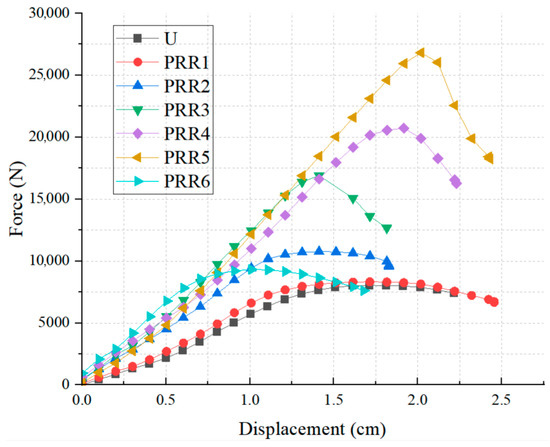

The length of the constraint section directly affects the type of instability, as shown in Figure 15 and Table 7. The axial displacement–force response curves of PRR-ASMs exhibit common characteristics: in the initial stage, they show a linear increasing relationship between displacement and force, with the slope of the curve remaining relatively constant. Displacement increases uniformly with the increase in force, reflecting that the material is in the elastic deformation domain. When the axial force continuously increases to the critical pressure, PRR-ASM reaches its ultimate bearing state. After the peak, the bearing performance shows a significant and rapid decline, accompanied by continuous displacement growth.

Figure 15.

Axial displacement–force comparison of PRR-ASM.

Table 7.

Improvement rate of ultimate force and ultimate yield displacement of test specimens.

Axial force is the bearing capacity of PRR-ASM. As shown in Table 7, the minimum improvement in bearing capacity of PRR1 is 3.5%, and the maximum improvement in bearing capacity of PRR5 is 234.3%. Compared with U, the reinforced specimens show a significant improvement in bearing capacity, demonstrating the effectiveness of PRR-ASM. With the increase in the constraint segment length, the ultimate bearing capacity of the specimens gradually increases. With the increase in the length of PRR members, the axial displacement of PRR-ASM decreases.

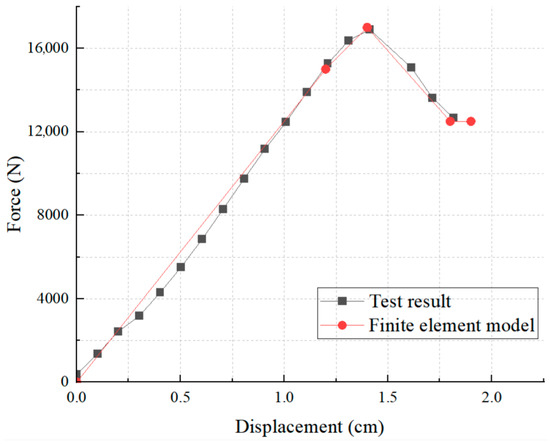

6.3. Proposal of the Constitutive Model for PRR-ASM

Based on the experimental results, PRR3 is considered an excellent specimen. Based on this excellent specimen, the constitutive model of PRR-ASM was established to prepare for subsequent simulations. Since all steel components are made of Q235B, the quadratic flow plastic model for steel in ABAQUS software was referenced [22]. The model was simplified, and the simplified model of PRR-ASM was simulated using the T3D2 element in ABAQUS software. The results obtained from the simplified constitutive model were compared with the test results of PRR-ASM, as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Comparison between PRR-ASM simplified constitutive model and test results.

7. Wind Vibration Analysis of Reinforcement Effect on Transmission Towers Using PRR-ASM

To investigate the enhancement effect of the proposed PRR-ASM on the wind resistance performance of the transmission tower-line system, this study section conducts finite element analysis. Studies on the wind resistance performance of transmission towers usually rely on numerical simulation methods [23,24,25,26]. In this part of the work, the construction of the transmission tower-line system model is first completed. Then, based on the dynamic time–history analysis method, the calculation of wind vibration responses is carried out.

7.1. Finite Element Modeling and Modal Analysis of Tower-Line System

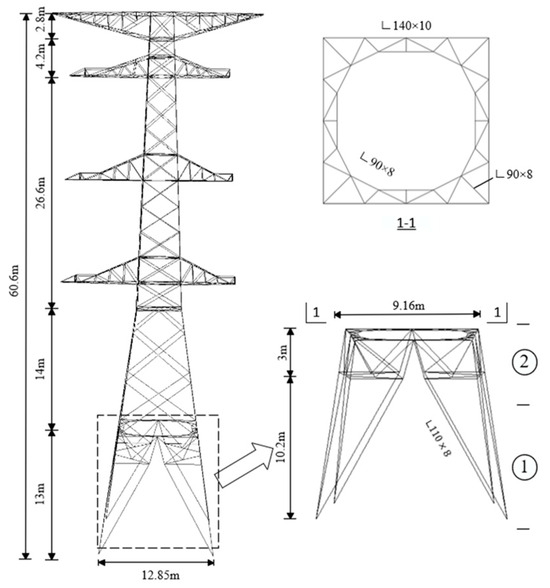

The transmission tower selected is the tension section of the standard design module 2F3B6 for 220 kV transmission lines of the China Southern Power Grid. The transmission tower is a double-circuit corner tower for 220 kV AC lines, and its single-line diagram is shown in Figure 17. The total height of the transmission tower is 60.6 m, and the nominal height is 32 m. Material selection strictly follows actual engineering standards: Q235 and Q355 steels are used for auxiliary components/partial diagonal members and main members/critical diagonal members, respectively. The material parameters of Q235 are determined in accordance with the GB/T700-2006 Carbon Structural Steel specification. The entire tower adopts 12 types of equal-leg single-angle steel members, and their specific models and geometric parameters are detailed in Table 8—the technical parameter table.

Figure 17.

Single-line diagram of transmission tower.

Table 8.

Model and cross-sectional areas of transmission tower angle steel.

The main member angle steel was simulated using B31 two-node linear beam elements, selected for their ability to model both flexural and axial responses with linear interpolation, which is optimal for the slender angle steel components under wind loads. Auxiliary members use T3D2 spatial truss elements. Diagonal members are treated differently according to cross-sectional properties—those with a cross-sectional area greater than 25 cm2 use beam elements, and the rest use truss elements. The transmission conductor and ground wire system uses a four-layer arrangement structure: the top layer is a lightning protection line, and the three lower layers are four-split conductors. Conductors and ground wires are simulated using T3D2 spatial cable elements, and spacers and insulators are characterized using B31 beam elements. Detailed design parameters of the system are shown in Table 9. Among them, spacers are designed with a length of 0.45 m, one set is installed every 100 m, and reference planes are configured.

Table 9.

Design parameters for transmission lines.

Modal analysis was performed based on the established finite element model of the transmission tower. The first four natural frequencies and modal shapes of the transmission tower were obtained, as shown in Table 10. The first four modes of the transmission tower are shown in Figure 18.

Table 10.

First four natural frequencies and modal characteristics of transmission towers.

Figure 18.

First four modes of transmission tower.

According to the suggestion of the Chinese power industry [27], the first natural period of the transmission tower is calculated as

where T1 is the first natural period, in seconds. f1 is the first natural frequency, measured in Hz. H is the height of the transmission tower, measured in meters; B is the root width, measured in meters; and b is the width of the tower head, measured in meters. According to Equation (1), the first natural period of this transmission tower is T = 0.5 s. The first natural frequency is f = 2 Hz. Compared with the finite element model calculation results, the error in natural frequency is less than 5%. This indicates that using this finite element model for calculations is relatively reliable.

7.2. Wind-Induced Response Analysis

Wind loads primarily consist of two components: mean and fluctuating parts. The mean wind load is relevant to static load analysis. Transmission towers are generally situated in Class B terrain, and this investigation utilizes the Class B terrain classification for turbulence intensity calculation. I10 denotes the reference turbulence intensity at 10 m elevation, assigned a value of 0.12 under Class B terrain conditions. Here, α represents terrain roughness, while z indicates the height above ground level.

Turbulence intensity is computed in accordance with current load specifications, whose mathematical expression is presented as follows:

Within international load standards and wind engineering practices, the Kaimal spectrum is frequently employed [28]. It characterizes the fluctuating wind speed spectrum corresponding to mean measured values at various heights above the ground, with its mathematical formulation given by

In this equation, , , z denotes the height of the simulated point (in meters), n represents the frequency (in Hz), and k stands for the coefficient associated with ground roughness (with terrain type B specified) and corresponds to the mean wind speed at a 10 m reference height.

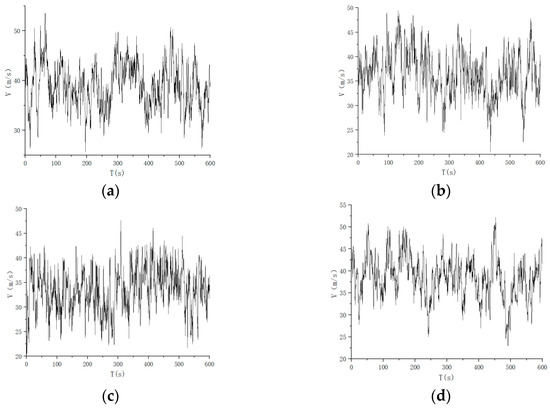

This research employs the autoregressive linear filtering method (AR method) for fluctuating wind simulation [28]. The wind speed of the transmission tower is segmented into 11 sections, corresponding to 11 points in the simulation space. This study focuses on the unstable segments 1 and 2 of the transmission tower legs, as illustrated in Figure 17. Time histories of fluctuating wind speed at the center point of the three-section conductor are presented in Figure 19a–c, while Figure 19d displays that at the ground line center point. By incorporating the 0–600 s pulsating wind speed time history, the wind speed spectrum enables wind vibration response analysis for the transmission tower.

Figure 19.

Time–history curve of fluctuating wind speed. (a–c) represents simulated points 1–3 on the wire. (d) Corresponding to simulation point 1 on the ground line.

The key simulation parameters for pulsating wind speed are as follows: ground roughness category of Class B terrain, power index of 0.12; use Shiotani coherence function; simulate using P = 4th order autoregressive (AR) method; simulate 13 spatial points; apply a time step of 0.1 s and a frequency step of 0.01 Hz; and the average wind profile follows a power-law wind speed spectrum and selects the Kaimal spectrum. The Kaimal spectrum is used to generate a time series of fluctuating wind speeds for each segment.

Each wind speed time history of each segment is converted into wind loads and applied onto the finite element model. Each wind load segment is evenly divided into four parts and applied to the four nodes of the tower segment. The fluctuating wind-induced load in ABAQUS adopts amplitude loading with an interval of 0.1 s. The wind-induced load of the transmission tower-line system model lasts for 100 s at all wind loading steps. Considering the direction of wind load under extreme working conditions, the wind angle of attack is 90° to the wind direction condition. The wind direction is orthogonal to the wind state of the conductor.

7.3. PRR-ASM Enhances the Wind Resistance of Tower-Line System

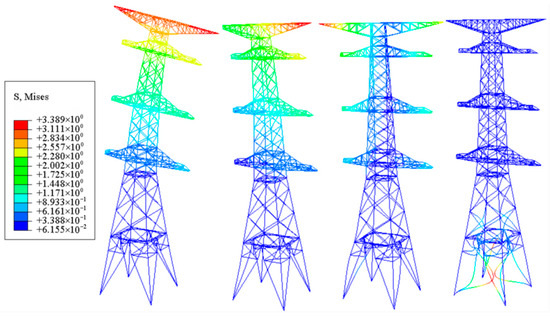

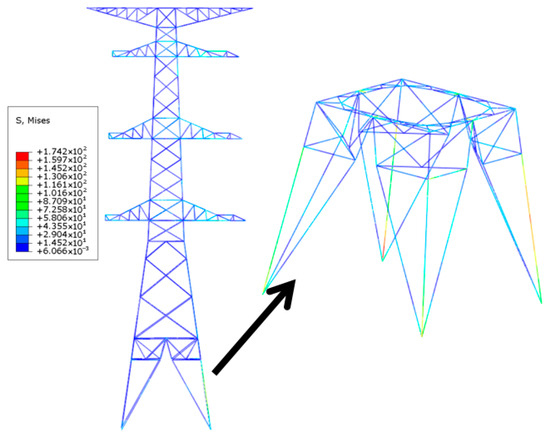

By applying coupled wind and vertical loads to the transmission tower-line system, according to the finite element calculation results, the original tower fails at the main tower leg location. At a wind speed of 20 m/s, the main member in the compressed zone of the tower leg is the key stress concentration component, as shown in Figure 20. At this point, the structure is in an elastic working state, and the main angle steel of the tower leg on the compressed side is the member with the maximum stress.

Figure 20.

Stress contour map of main tower leg of transmission tower.

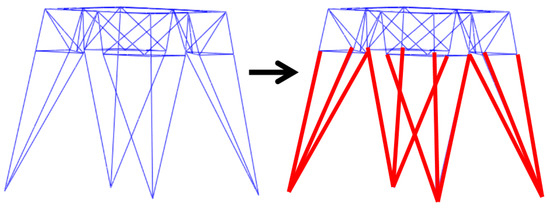

When the wind speed increases to 25 m/s, the tower leg angle steel first enters the plastic yielding stage. This triggers internal force redistribution in the tower structure, with the stress in the angle steel of the main tower leg increasing significantly. After the wind speed exceeds 25 m/s, the tower top displacement undergoes a sudden change, and the calculation fails to converge. Based on the L110 × 7 equal-leg angle steel diagonal bracing member, the calculated slenderness ratio is 145. According to the principle of equivalent parameters with the test reinforcement members, it can be considered that it is equivalently replaced with the reinforcement members. According to the simplified model in Section 6.3, the reinforcement position covers all components of the transmission tower legs, as shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21.

Steel reinforcement model of transmission tower legs. The red area indicates the reinforced tower legs.

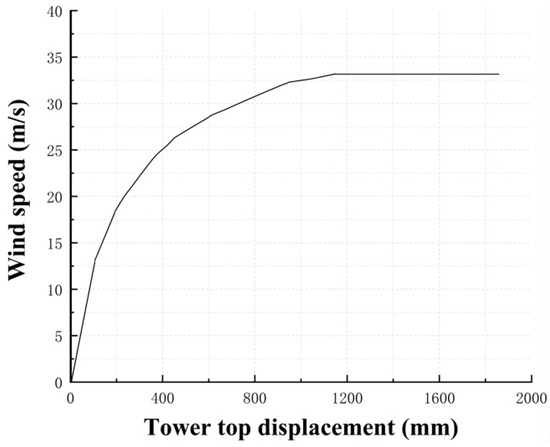

For the transmission tower-line system after applying PRR-ASM, before the wind speed reaches 32 m/s–35 m/s, the tower top displacement shows a positive correlation with wind speed. When the wind speed exceeds 32 m/s, the overall displacement approaches a horizontal angle, and at this point, the tangent slope of the tower top displacement-wind speed curve segment is the smallest. Judging by the B-R criterion [29], the ultimate wind speed of the transmission tower under the partial constraint reinforcement scheme is 32 m/s. At wind speeds exceeding 32 m/s, the finite element calculation fails to converge, and the transmission tower structure is damaged. The comparison of top tower displacements of the reinforced transmission tower-line system model is shown in Figure 22. After applying PRR-ASM, the tower top displacement is significantly reduced, and the stability of the transmission tower-line system is good.

Figure 22.

Comparison of tower top displacements.

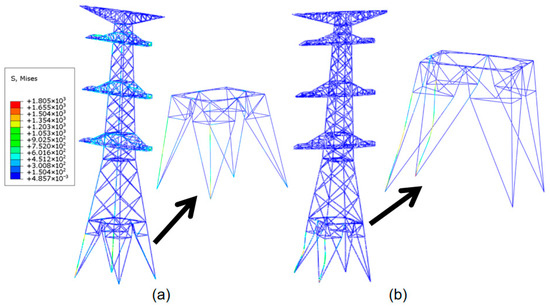

Both the original tower and the PRR-ASM-reinforced transmission tower failed due to the strength failure of members at the main tower leg angle steel. This led to a significant increase in tower top displacement, causing overall instability of the transmission tower-line system. Figure 23 is a comparison diagram of the transmission tower before and after reinforcement. As shown in Figure 23a, under the combined action of conductors and crossarms, the main tower leg angle steel underwent strength failure due to stress exceeding the limit. Accompanied by significant deformation of the tower body, this indicates that the tower-line system entered a failure state. As shown in Figure 23b, the angle steel did not yield, and the tower top displacement was small; therefore, the PRR-ASM reinforcement scheme is considered effective.

Figure 23.

Comparison before and after reinforcement of transmission towers. Part (a) is an unreinforced tower, and part (b) is a tower reinforced with PRR-ASM.

The stress safety factor (SF) is defined as the ratio of the structural design value (design stress of Q235B) to the maximum stress effect. Based on the comparison of models before and after reinforcement: the yielding of main members occurred in the original tower at a wind speed of 25 m/s, corresponding to SF = 1.6 (ultimate state). After reinforcement with PRR-ASM, the ultimate wind speed of the transmission tower increased to 32 m/s with SF = 3.4 (design stress/maximum stress of members in simulation results), representing an increase of 52%. Therefore, PRR-ASM is considered effective. Compared with the F-BRR reinforcement scheme, this scheme improves the safety factor and reduces costs. Moreover, using prefabricated assembly reduces labor costs and the construction period.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposes an angle steel constraint reinforcement scheme using a partial constraint method to improve the stability of existing angle steel members, namely PRR-ASM. Through compression tests and numerical simulations, the constraint reinforcement schemes under different working conditions were studied, and the transmission tower was reinforced using PRR-ASM to analyze the actual wind resistance enhancement effect of the tower-line system. The concluding remarks are summarized as follows.

- (1)

- The PRR-ASM scheme effectively improves the compressive stability performance of existing angle steel members. A systematic study on the influence mechanism of constraint gaps in PRR-ASM was conducted, and through tests and numerical simulations of six sets of comparative specimens, the influence law of gap size on reinforcement performance was revealed. Reinforcement without gaps (P-BRR3) achieved a 31% increase in the bearing capacity and a 92.2% increase in yield displacement through the coordinated deformation of locally strengthened cores and constrained members, with the failure mode changing from overall instability to local bending instability.

- (2)

- A systematic study was conducted on the influence mechanism of constraint segment length in the PRR-ASM scheme. Through the experimental comparison of seven sets of comparative specimens, the core principles of the PRR-ASM technique were revealed, where the constraint segment length directly affects the instability type. Short constraint segments (<300 mm) primarily exhibit global flexural buckling. However, excessively long constraint segments (>750 mm) cause the contribution of constraints to overall stability to tend toward saturation. The axial displacement–load curve shows that better improvement in stability performance can be achieved with partial constraints.

- (3)

- Based on the wind-induced response analysis of the transmission tower-line system, the PRR-ASM scheme increases the ultimate wind speed from 25 m/s to 32 m/s. The safety factor of members increases from 1.6 to 3.4. The PRR-ASM scheme is recommended for engineering practice because it improves efficiency and economic cost.

- (4)

- This paper focuses on studying the performance of the PRR-ASM scheme in improving the stability of the main leg angle steel of transmission towers under design wind loads. However, PRR-ASM is currently in the theoretical research stage. Regarding the constrained angle steel, how to select weaker materials to achieve the original improvement effect requires further research. The comparison between PRR-ASM and traditional reinforcement methods that require drilling and welding will be further studied in subsequent work. Moreover, its overall stability design and practical application design methods will be the focus of our future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C. and D.Z.; methodology, N.Z.; validation, B.Y. and K.G.; formal analysis, T.C.; investigation, D.Z. and H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.; writing—review and editing, H.C., B.Y., and D.Z.; visualization, K.G. and D.Z.; supervision, T.C. and N.Z.; project administration, T.C.; funding acquisition, T.C. and D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Tianyuan Cai, Dehui Zhao, and Baohai Yang are employed by the company State Grid Inner Mongolia Eastern Electric Power Co., Ltd. The authors Ning Zhang, Kangning Guo, and He Chen are employed by the company North China Power Engineering Co., Ltd. of China Power Engineering Consulting Group.

References

- Meng, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, J. Wind-ice-induced Damage Risk Analysis for Overhead Transmission Lines Considering Regional Climate Characteristics. Eng. Struct. 2025, 329, 119844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.D.; Fan, J. Progressive collapse analysis of a truss transmission tower-line system subjected to downburst loading. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2022, 188, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albermani, F.; Kitipornchai, S.; Chan, R.W.K. Failure Analysis of Transmission Towers. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2009, 16, 1922–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Mao, J.; Wang, H.; Gao, H.; Li, D. Deep learning-based automated identification on vortex-induced vibration of long suspenders for the suspension bridge. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 2025, 224, 112070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J. Theoretical Model for Circular Concrete-Filled Steel Tubes Reinforced with Latticed Steel Angles Under Eccentric Loading. Buildings 2025, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.E.; Ma, X.; Zhuge, Y. Experimental study on multi-panel retrofitted steel transmission towers. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2012, 78, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, Y.; Mills, J.E.; Ma, X. Modelling of steel lattice tower angle legs reinforced for increased load capacity. Eng. Struct. 2012, 43, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Moon, B.W.; Min, K.W. Cyclic loading test of friction-type reinforcing members upgrading wind-resistant performance of transmission towers. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 3185–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.H.; Ma, X.; Mills, J.E. Modeling of retrofitted steel transmission towers. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2015, 122, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Yang, Q.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D. Fragility Analysis and Wind Directionality-Based Failure Probability Evaluation of Transmission Tower under Strong Winds. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 246, 105668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ma, X.; Mills, J.E. The Structural Effect of Bolted Splices on Retrofitted Transmission Tower Angle Members. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2014, 95, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H.; Ishii, K.; Fukushima, A. Experimental Study on Buckling Strength of Angle Steel Compression Members with Built-up Bracing. Steel Constr. Eng. 2010, 16, 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, G.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Mechanical behavior of steel transmission tower legs reinforced with innovative clamp under eccentric compression. Eng. Struct. 2022, 258, 114101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ma, X.; Mills, J.E. Cyclic Performance of Reinforced Legs in Retrofitted Transmission Towers. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2018, 18, 1608–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yan, Z.; Jiang, T.; Guo, T.; Zou, Y. Experimental study on failure modes of a transmission tower reinforced with clamps. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthi, G.B.G.; Deepak, M.; Roy, K.; Lim, J.B. Influence of intermediate stiffeners on the axial capacity of cold-formed steel back-to-back built-up unequal angle sections. Structures 2021, 32, 827–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Trovato, M.; Stojanović, B. In-Situ Retrofit Strategy for Transmission Tower Structure Members Using Light-Weight Steel Casings. Eng. Struct. 2020, 206, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Cai, T.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Su, N. Enhancing the wind-resistant capacity of transmission towers with buckling-restraint-reinforced angle-steel-members (BRR-ASMs). J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 228, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettler, M.; Lichtl, G.; Unterweger, H. Experimental tests on bolted steel angles in compression with varying end supports. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2019, 15, 155301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, P.; Chen, H.; Ge, J.; Peng, C. Experimental and Numerical Investigations on Load Capacity of SRC Beams with Various Sections. Buildings 2025, 15, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50017-2017; Standard for Design of Steel Structures. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Han, J. Research on Seismic Performance of Truss Stiffened Double Steel Plate Composite Shear Wall Dissertation. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Li, S.; Jin, W.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Frequency Domain Analysis of along wind Response and Study of Wind Loads for Transmission Tower Subjected to Downbursts. Buildings 2022, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Dong, Z. Fragility analysis of a transmission tower under combined wind and rain loads. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 199, 104098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Sun, L. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Behavior and Failure Mechanism of a Latticed Steel Transmission Tower. J Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, S.; Philip, P.M. Numerical Analysis of Transmission Line Tower with Connection Beam on Pile Foundation. In Recent Advances in Structural Engineering and Construction Management: Select Proceedings of ICSMC 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DL/T 5551–2018; Electric Power Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China, Load Code for the Design of Overhead Transmission Line. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Manarikkal, I.; Elasha, F.; Mba, D. Diagnostics and prognostics of planetary gearbox using CWT, auto regression (AR) and K-means algorithm. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 184, 108314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiansky, B.; Roth, R.S. Axisymmetric Dynamic Buckling of Clamped Shallow Spherical Shells; NASA Technical Note D-1510; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).