Abstract

To address the difficulties in characterizing fine crack morphology, the limitations of detection accuracy, and the challenge of real-time deployment caused by large model parameter counts in concrete dam crack detection, this paper constructs DamCrackSet-1K, a high-resolution dataset with pixel-level annotations covering multiple crack scenarios; proposes a lightweight semantic segmentation framework, MTC-Net, which integrates a MobileNetV2 encoder with Enhanced Transformer modules to achieve global–local feature fusion and enhance feature extraction; and designs a geometry-sensitive Curvature-Aware loss function to effectively mitigate pixel-level class imbalance for fine cracks. Experiments show that, while significantly reducing the number of model parameters, the method greatly improves crack detection accuracy and inference speed, providing a feasible solution for efficient, real-time crack detection in dams.

1. Introduction

Dams play a crucial role in national water resource management, power generation, and ecological protection. Since the mid-20th century, China has constructed over 98,000 dams, most of which are embankment dams. Due to their long service life and the intrinsically low tensile strength of concrete, many concrete dams gradually develop surface cracks, potentially compromising structural integrity and posing safety risks. Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods have long been used to assess the condition of civil infrastructure without causing damage, providing essential support for early defect identification and maintenance planning. However, traditional NDT techniques still face limitations in detection efficiency, field adaptability, and large-scale deployment, motivating the exploration of more effective and intelligent inspection approaches [1]. Therefore, accurate crack detection and timely maintenance are essential for structural health monitoring (SHM). SHM covers displacement prediction, reflecting the structure’s global response to environmental loads, and surface crack detection, identifying local damage that may lead to failure. Recent studies have applied deep learning methods to enhance the accuracy of displacement modeling [2], and the use of deep learning algorithms for surface crack detection has also become an important trend in civil engineering practice [3,4].

The development of crack detection methods has undergone four distinct stages. The first stage (1950–1990s) relied primarily on manual inspection. During this period, crack detection in dams was mainly based on visual inspection and manual recording by on-site engineers. Cracks on concrete surfaces were typically observed through walking patrols or slow-moving vehicles, with measurements and annotations made using rulers and engineering drawings [5]. As the limitations of manual methods became increasingly apparent—not only in concrete dam inspection but also in broader applications—more efficient detection methods were demanded, which led to the emergence of automated and intelligent crack detection techniques [6]. The second stage (1990–2010) focused on signal processing techniques. In this phase, image processing and frequency domain analysis were gradually introduced, improving the ability to extract crack edges and texture features. Mallat’s multiresolution wavelet analysis theory has been widely applied in image-based damage detection tasks, including crack recognition on concrete surfaces [7]. However, its performance was highly sensitive to scale parameters, making it unsuitable for unified detection across cracks of different sizes. Mahler et al. developed the Automatic Crack Measurement system, which used gradient histograms, binary segmentation, and skeletonization algorithms to automatically extract quantitative parameters such as crack length, width, and orientation [8]. In addition, Medina et al. combined Gabor filtering and frequency domain convolution to achieve directional identification of longitudinal and transverse cracks, maintaining stable detection performance under varying lighting conditions [9]. Despite their initial automation capabilities, methods of this stage still suffered from limited robustness and adaptability, necessitating further refinement. The third stage (2010–2017) witnessed the rise of machine learning-based classification methods. These approaches primarily relied on extracting morphological and textural features from images and using models such as neural networks to classify crack types. Zakeri et al. proposed a multi-stage expert system that integrated wavelet transforms, 3D Radon transforms, and fuzzy logic, significantly enhancing classification robustness [10]. Banharnsakun et al. combined the artificial bee colony algorithm with an artificial neural network (ANN) to achieve automatic crack classification [11]. Although these methods were more intelligent than traditional techniques, they still relied heavily on handcrafted features and exhibited limited generalization capabilities.The current fourth stage (2017–present) of dam health monitoring is characterized by the increasing integration of deep learning techniques [12]. This fourth stage reflects a shift from conventional rule-based detection to data-driven understanding [13]. For crack analysis, neural networks, particularly convolutional and segmentation-based models, have made significant advances. Yet, the limited accessibility of underwater visual data remains a challenge. To address this, researchers have turned to image synthesis techniques, such as image-to-image translation, to augment datasets [14]. Simultaneously, the use of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) paired with lightweight detectors like YOLO variants has enabled more responsive underwater inspections [15]. Beyond visual tasks, deep learning has also contributed to the modeling of structural behavior. For example, Wu et al. introduced a hybrid clustering approach for modal parameter identification, improving stability and automation in arch dam analysis [16]. In deformation prediction, the Gated Recurrent Unit–Self-Attention–Temporal Convolutional Network model combines sequence learning and attention mechanisms to achieve high accuracy across multiple measurement points [17].

However, existing lightweight convolutional networks and efficient Transformer variants still face several challenges when applied to fine-grained crack segmentation. First, cracks exhibit extremely sparse and irregular geometric structures, making it difficult for conventional CNNs to capture long-range dependencies. Second, many efficient Transformer models rely on generic token reduction or window partitioning strategies, which may cause the loss of thin crack features. Third, pixel-level class imbalance remains severe in tiny-crack regions, and existing losses often fail to account for geometric continuity.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: (1) DamCrackSet-1K, a high-resolution crack segmentation dataset covering diverse dam scenarios with pixel-level annotations, was constructed to address the scarcity of high-quality samples for fine-grained crack analysis; (2) MTC-Net, a lightweight segmentation framework that integrates a MobileNetV2 encoder with a domain-tailored Enhanced Transformer, was developed to incorporate geometry-aware token interaction and a global–local fusion mechanism specifically designed for modeling sparse crack structures; (3) Curvature-Aware loss, a geometry-sensitive objective function that encodes local structural smoothness, was formulated to alleviate extreme pixel imbalance and structural discontinuity in tiny cracks; (4) Comprehensive experiments were conducted to verify the effectiveness of the proposed dataset, architecture, and loss function, demonstrating state-of-the-art accuracy with real-time inference speed and providing new insights for lightweight Transformer design and geometry-aware vision tasks beyond dam crack detection.

2. Background of Deep Learning-Based Crack Analysis

In recent years, deep learning-based crack analysis has rapidly evolved and become a prominent research focus in structural health monitoring. Existing approaches can be broadly categorized into object detection methods, which emphasize rapid crack localization, and semantic segmentation methods, which aim to provide fine-grained morphological characterization. Despite their respective strengths in adapting to dam crack patterns, achieving detection accuracy, and enabling efficient deployment, both paradigms exhibit notable limitations. Therefore, this study systematically reviews and evaluates the applicability and constraints of these two approaches in dam crack detection scenarios.

2.1. YOLO-Based Detection Paradigm for Crack Localization

Object detection methods have been widely adopted due to their fast inference speed and relatively simple implementation. Among them, the YOLO series, as a representative algorithm, can efficiently locate crack regions by predicting bounding boxes. However, when confronted with the complex and highly variable crack patterns found in dams, their detection accuracy still faces significant challenges. As quantified in Table 1, even advanced YOLOv10 achieves merely 43.09% mAP0.50:0.95, proving detection frameworks ill-suited for SHM. in the context of dam crack analysis, this study has identified three critical limitations in such methods: (1) Geometric mismatch: The axis-aligned bounding box paradigm fundamentally conflicts with the anisotropic morphology of curvilinear cracks, leading to erroneous region proposals; (2) Fragmentation artifacts: Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) inherently suppresses discontinuous crack instances due to their irregular spatial distribution; and (3) Scale blindness: Fixed receptive fields in convolutional backbones fail to adapt to multiscale crack patterns, particularly sub-millimeter defect structures.

Table 1.

Performance of YOLO series detectors on DamCrackSet-1K.

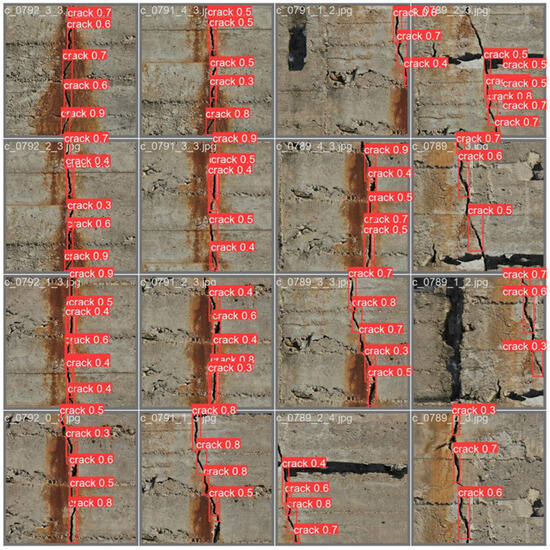

As illustrated in Figure 1, the YOLO-based algorithms exhibit notable limitations in dam crack detection, particularly in identifying fine cracks. The detection results often suffer from issues such as redundant bounding boxes, missed detections, and low confidence scores (typically ranging from 0.3 to 0.5).

Figure 1.

YOLO-based dam crack detection results.

The problems mentioned above impede the accurate localization and morphological characterization of cracks, thereby compromising the reliability of practical monitoring applications. To address these challenges, several key strategies have been proposed: Contour-aware mask regression preserves crack geometry by aggregating boundary-sensitive features, ensuring that the fine details of crack contours are retained. Resolution-preserving encoder-decoder architectures maintain defect localization accuracy through skip connections, effectively bridging the gap between high-level semantic information and detailed spatial features. Multi-scale feature fusion resolves submillimeter cracks through pyramidal pooling modules [18], enabling the model to capture cracks at various scales and improve overall detection performance. These advancements collectively enhance the robustness and accuracy of crack detection and characterization in practical applications.

2.2. Mask R-CNN-Based Segmentation Paradigm for Morphology Preservation

Compared with object detection methods, semantic segmentation methods can characterize crack morphology on a pixel-by-pixel basis, making them more suitable for the complete representation of complex geometric features. By generating instance-aware segmentation masks, they can provide more detailed crack boundary information, thereby significantly enhancing morphology preservation capabilities.Mask R-CNN [19] is a quintessential example of this paradigm shift, demonstrating robust detection and segmentation performance on bridge crack datasets through instance-aware mask prediction. However, as quantified in Table 2, its two-stage architecture incurs substantial computational costs, rendering real-time deployment on edge devices impractical.

Table 2.

Benchmarking Common Deep Learning Architectures in Crack Analysis.

In dam structural health monitoring, crack analysis algorithms must not only deliver high-precision detection, but also satisfy real-time requirements and enable efficient deployment on resource-constrained mobile terminals or edge devices to support rapid on-site decision-making. Recent advances in lightweight segmentation [20] have shown promise through techniques like depth-wise separable convolutions and neural architecture search. However, existing solutions still tend to compromise accuracy, often resulting in a 6–8% drop in mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) when reducing parameters below 30 M. Therefore, developing a lightweight image segmentation approach that strikes an optimal balance among detection accuracy, inference efficiency, and deployability not only better aligns with the demands of practical engineering applications, but also defines a clear research direction for future model design.

3. Related Work

3.1. Segmentation Architecture Innovations

In concrete dam crack detection, cracks exhibit diverse and irregular morphological patterns. Consequently, in scenarios with complex backgrounds, uneven lighting, and extremely fine crack widths, higher demands are placed on segmentation networks in terms of small-object modeling, boundary preservation, and inference efficiency.

The U-Net architecture [21], with its symmetric encoder–decoder design and training-friendliness for small datasets, has become a widely adopted baseline model in crack detection. However, its symmetric structure shows significant limitations when applied to linear crack patterns, leading to three inherent constraints: (1) Isotropic convolution kernels struggle to model directional variations in cracks; (2) Skip connections tend to propagate low-frequency artifacts, degrading boundary quality; and (3) The downsampling process can easily erode slender cracks.Attention-enhanced variants [22] address these issues through adaptive feature gating, but at the cost of significantly increased parameter complexity.

Vision transformer adaptations [23] introduce global context modeling via self-attention mechanisms, demonstrating theoretical advantages for irregular defect shapes. However, their quadratic computational scaling relative to input resolution renders them impractical for high-resolution infrastructure inspection scenarios. In high-resolution civil engineering imagery, convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures still maintain an advantage in inference efficiency. However, their ability to capture fine cracks is limited by the inherent constraints of the receptive field. Overall, the performance bottleneck of CNN-based models in processing high-resolution dam crack images motivates the exploration of an innovative model design that achieves a better trade-off among accuracy, computational cost, and deployment feasibility.

3.2. Hybrid Architecture and Loss Optimization

3.2.1. Hybrid Design Paradigms

Recent architectural innovations attempt to reconcile these competing demands: Lightweight CNN variants [24] prioritize mobile deployment through operator-level optimizations, but sacrifice multi-scale representational capacity. Real-time specialized networks [25] employ hardware-aware pruning strategies, achieving edge compatibility at the expense of segmentation fidelity.

Modern edge-oriented model compression operates through three principal paradigms called lightweight design strategies: 1. Architectural innovation: MobileNet’s inverted residuals [26] establish depthwise separable convolution as the mobile computation standard. 2. Quantization awareness: Mixed-precision training [27] enables INT8 inference without accuracy degradation. 3. Knowledge distillation: Feature mimicry learning [28] transfers knowledge from the teacher to compact student networks.

In crack detection, EfficientCrackNet [29] exemplifies architectural efficiency requiring only 0.26 M parameters, and 0.483 FLOPs (G). However, its deep network configuration induces gradient vanishing during backpropagation.

However, although hybrid architectures achieve a certain balance between feature modeling capacity and inference efficiency, crack detection tasks still face several challenges, including class imbalance [30], blurred boundaries [31], and insufficient representation of fine crack structures [32]. Structural design alone is no longer sufficient to fully address these issues. This underscores the importance of optimizing the loss function as a critical direction for further improving segmentation performance [33].

3.2.2. Loss Function Evolution

The inherent class distribution imbalance in crack segmentation has driven progressive innovations in loss function design. Early approaches adapted region-based losses like Dice [34] to address foreground scarcity, while subsequent work introduced Tversky loss [35] through parametric tuning of false negative penalties—a critical advancement for thin crack preservation. Frequency-domain insights further shaped this evolution, with spectral weighting strategies [36] emerging to enhance micro-crack sensitivity by emphasizing high-frequency components.

Traditional loss formulations remain constrained by two persistent challenges: (1) structural inconsistency between predicted and actual crack topology, and (2) inadequate edge sensitivity when handling sub-pixel defect boundaries. Our Curvature-Aware Loss addresses these limitations through a unified spatial-frequency optimization framework, theoretically bridging the gap between global shape coherence and local boundary precision.

3.3. Overall Framework of the Proposed Method

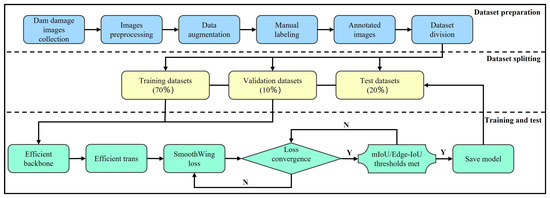

The proposed method, as illustrated in Figure 2, consists of three stages. The data collection stage involves acquiring dam surface damage images, followed by preprocessing, data augmentation, and manual annotation. In the data partitioning stage, the dataset is divided into training, validation, and testing subsets.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the proposed crack detection method.

During the training and testing stage, an efficient backbone network is employed for feature extraction, and the Curvature-Aware loss function is introduced to optimize model performance. The loss convergence is dynamically monitored throughout training, and the model is evaluated using mIoU and Edge-IoU as the primary metrics. Once the performance reaches a predefined threshold, the model is saved for deployment in dam crack detection tasks.

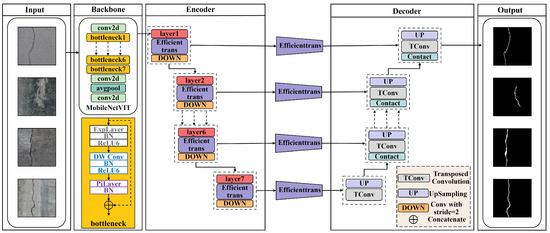

As illustrated in Figure 3, Our dam crack segmentation framework integrates three key innovations to address edge deployment challenges and structural defect characteristics: (1) a lightweight MobileNetV2 backbone optimized for crack pattern preservation, (2) an Enhanced Transformer block with crack-prioritized attention, and (3) a hybrid Curvature-Aware loss for imbalanced pixel learning. The architecture combines these components through a U-shaped network that progressively refines local textures and global crack continuity.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the proposed crack segmentation framework.

The MobileNetV2 encoder is adapted through channel reconfiguration and gradient-sensitive convolutions to maintain micron-scale crack features. Subsequent skip connections are enhanced with our Enhanced Transformer blocks, which apply localized attention along predicted crack paths to model long-range dependencies. The decoder path combines these features with adaptive upsampling, while the Curvature-Aware loss dynamically balances precision and recall through curvature-aware constraints.

4. Methodology

4.1. MobileNetV2-Based U-Net Architecture

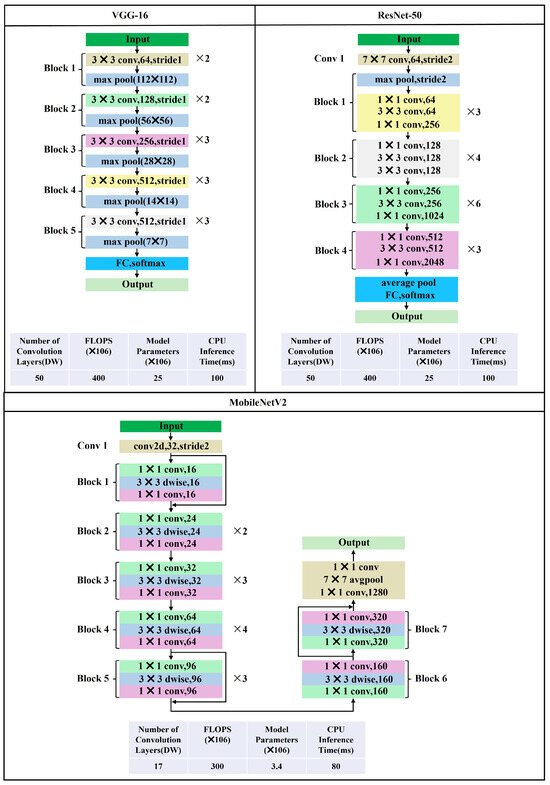

Our choice of MobileNetV2 as the encoder backbone stems from three critical requirements for concrete crack image segmentation: (1) real-time inference on mobile devices, (2) preserved spatial details through shallow layers, and (3) compatibility with skip connection mechanisms. As illustrated in Figure 4, MobileNetV2 adopts a linear bottleneck and inverted residual structure, which significantly reduces computational cost and parameter count while maintaining accuracy. Compared to VGG [37] and ResNet [38], it requires only 3.4 M parameters and 30 G FLOPs, offering higher inference efficiency and making it more suitable for deployment on embedded devices. The 19-layer architecture provides four natural downsampling stages (2×, 4×, 8×, 16×, 32×), aligning perfectly with U-Net’s multi-scale fusion paradigm.

Figure 4.

Architectures of VGG-16, ResNet-50, and MobileNetV2 (MobileNetV2 used as the backbone).

To integrate MobileNetV2 into the U-Net framework, this study employs the following design components, with the encoder stage configurations summarized in Table 3:

Table 3.

MobileNetV2 Encoder Stages.

- (1)

- Encoder Stream: Use original MobileNetV2 layers up to the final 1280-channel expansion (excluding classification head).

- (2)

- Channel Balancing: Insert 1 × 1 convolutions to align skip connection channels with decoder dimensions.

- (3)

- Skip Connections: Extract multi-scale features from four strategic stages:

Table 3 presents the output resolution, number of channels, and number of inverted residual blocks for each stage of the MobileNetV2 encoder. Each inverted residual block follows [39] with expansion ratio and ReLU6 activation. This study initializes with ImageNet pretrained weights and fine-tune all layers.

To validate the suitability of MobileNetV2 as the backbone network, this study conducts a systematic comparison of several commonly used alternative backbones with reference to our crack imaging dataset. ResNet-50: 3.8× more FLOPs than MobileNetV2, incompatible with ARM NEON instructions; EfficientNet-B3: 2.1× higher memory usage, irregular channel counts complicating skip fusion; VGG-16: Lacks expansion-convolution projection, causing 47% accuracy drop on small lesions.

MobileNetV2’s linear bottlenecks prove essential for preserving positive feature ranges in skip connections, while depthwise convolutions minimize spatial detail loss—critical for segmenting sub-millimeter anatomical structures.To this end, targeted architectural optimizations are applied to the decoder to improve overall segmentation efficacy. The decoder progressively upsamples features using bilinear interpolation followed by 3 × 3 convolutions, with channel dimensions mirroring the encoder’s contracting path. Skip connections fuse encoder features post Efficient Trans Block processing.

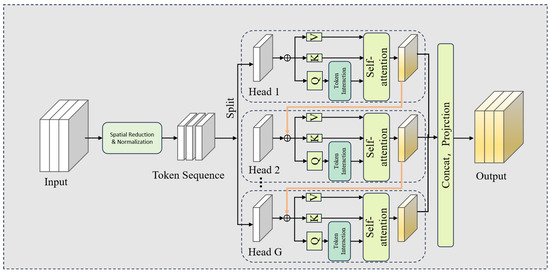

4.2. Enhanced Transformer Block

The integration of Transformer architectures into computer vision has demonstrated significant success in capturing long-range dependencies and global context information. However, the standard self-attention mechanism exhibits quadratic computational complexity with respect to spatial resolution, rendering it prohibitively expensive for high-resolution image segmentation tasks such as dam crack detection. To address this challenge, we propose an Enhanced Transformer block that maintains the global modeling capabilities of standard attention while achieving substantial computational efficiency gains.

4.2.1. Design Motivation and Architecture

Our design is motivated by the need to balance global contextual modeling with computational feasibility for high-resolution dam imagery. Traditional self-attention mechanisms require computations for feature maps of size , which becomes prohibitive for structural health monitoring applications.

The proposed Enhanced Transformer Block integrates seamlessly into both encoder and decoder pathways, positioned after channel reduction operations and before feature fusion steps. As illustrated in Figure 5, the module processes feature maps through three fundamental operations: spatial reduction, efficient attention computation, and resolution restoration. This architectural placement ensures operation on compressed feature representations, maximizing computational efficiency while enabling multi-scale global context aggregation.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the proposed Enhanced Transformer Block.

The micro-architecture incorporates several innovative components. A depthwise convolutional operation with kernel size and stride equal to the reduction ratio r performs spatial downsampling while maintaining channel dimensionality:

The reduced feature map then undergoes layer normalization followed by linear projections to generate queries, keys, and values:

Multi-head attention operates on the reduced spatial dimension, significantly decreasing computational requirements:

Finally, bilinear interpolation restores the original spatial resolution before the final projection and residual connection:

4.2.2. Mathematical Formulation and Complexity Analysis

The complete transformation can be formally expressed as:

where r represents the reduction ratio, denotes the key dimension, and and are learnable projection matrices.

The computational advantage of our approach is evident when comparing complexity:

For a typical reduction ratio applied to feature maps of spatial size with channel dimension , the standard attention mechanism requires approximately billion operations, while our efficient variant reduces this to billion operations—representing a reduction in computational requirements. This efficiency gain enables practical deployment on hardware with limited resources while processing high-resolution dam inspection imagery.

4.2.3. Benefits for Dam Crack Segmentation

The integration of our Enhanced Transformer Block provides substantial benefits for dam crack segmentation tasks. The attention mechanism enables effective modeling of long-range dependencies across large dam surfaces, connecting disparate crack regions that may appear disjoint in local receptive fields. Strategic placement at multiple decoder levels facilitates integration of contextual information at various scales, from fine crack details to broader structural patterns.

Crucially, the spatial reduction mechanism maintains the global modeling capabilities of Transformers while reducing computational requirements to feasible levels for high-resolution imagery. Experimental results on dam crack datasets demonstrate consistent improvement in segmentation metrics, particularly for elongated crack structures that benefit significantly from global context aggregation.

The proposed Enhanced Transformer Block represents a practical solution for incorporating global attention mechanisms into segmentation networks for structural health monitoring applications, effectively balancing performance gains with computational constraints inherent in processing high-resolution infrastructure imagery.

5. Experiments

5.1. DamCrackSet-1K Dataset Construction

5.1.1. Dataset Preparation

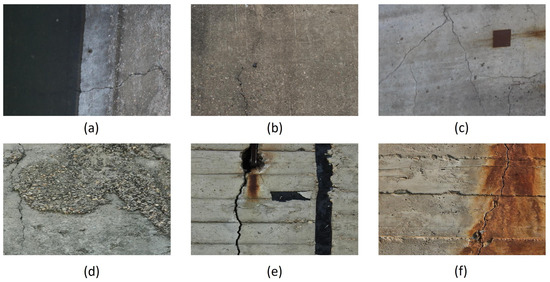

This study presents DamCrackSet-1K, a comprehensive benchmark for dam crack segmentation, consisting of 400 high-resolution (6000 × 4000) raw images captured using a Canon EOS 80D camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) across multiple inspection sites.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the dataset encompasses six representative real-world crack scenarios frequently encountered in dam and infrastructure inspection: Moisture-obscured cracks: Partially covered by water stains or wet surfaces, which reduce contrast and obscure crack edges; Hairline fractures: Narrow, low-contrast cracks with sub-millimeter width, challenging to detect under natural textures; Intersecting crack networks: Multiple cracks intersecting or branching, resulting in irregular geometries and fused boundaries; Aggregate interference: Rough background textures caused by exposed coarse aggregates, introducing false edges and high visual noise; Corrosion-scour composite defects: Cracks accompanied by corrosion or thermal scorching, often causing strong color distortions; Longitudinal corrosion-induced cracks: Cracks aligned along reinforcement paths, typically accompanied by large rust-stained regions.

Figure 6.

Representative crack scenarios included in the dataset: (a) moisture-obscured cracks, (b) hairline fractures, (c) intersecting crack networks, (d) aggregate interference, (e) corrosion-scour composite defects, (f) longitudinal corrosion-induced cracks.

To ensure image quality and reduce computational overhead, the original images were cropped to a resolution of 900 × 600 pixels. Data augmentation was performed using horizontal and vertical flipping. Images with ambiguous or indistinct crack features were manually excluded. After this preprocessing, a total of 1000 images were retained for the dataset. For effective training and parameter tuning, the dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets in a ratio of 7:1:2.

To ensure the quality and consistency of the annotations, the labeling process in this study was strictly controlled, and strong agreement was achieved among annotators. In addition, due to the high resolution of the original images and the thin, intricate geometry of crack boundaries, annotating a single image required approximately 6–10 min, resulting in more than 160 total labor hours for completing the dataset. This demonstrates that the construction of the dataset involved substantial manual effort, and the annotation quality-having undergone multiple rounds of verification—meets the standards required for reliable model training and evaluation.

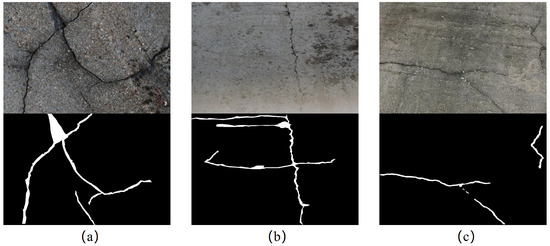

5.1.2. Dataset Generation

A total of 1000 high-resolution images were manually annotated using the Labelme tool (version 4.5.9) to construct a training dataset for concrete dam crack segmentation. This annotation step is the only human-involved stage in the pipeline, and its accuracy directly affects the segmentation model’s performance.

As illustrated in Figure 7, this study places particular emphasis on the accurate extraction and continuity of crack edges. Therefore, three representative crack structures were deliberately selected to highlight the diversity and difficulty of edge patterns: (a) shows multiple cracks intersecting in various directions, with slight disconnections at junctions. These gaps pose challenges to maintaining edge continuity and often result in fragmented predictions; (b) represents smooth, continuous multi-directional cracks with complex geometries, requiring the model to preserve edge coherence across multiple orientations; (c) depicts spatially separated cracks distributed across the surface. The weak and discontinuous edge signals in such cases can easily lead to false negatives or missing segments.

Figure 7.

Examples of annotated cracks from the dataset. (a) Intersecting cracks with discontinuities at junctions; (b) Multi-directional continuous cracks; (c) Spatially separated cracks with fragmented boundaries. These configurations present significant challenges for edge detection and continuity preservation.

These configurations not only occur frequently in real-world scenarios but also provide a rigorous test for assessing the model’s edge-awareness capabilities under varying crack topologies. They serve as important benchmarks for evaluating the robustness and adaptability of the proposed method.

To ensure the rigor and consistency of the annotation process, the following quality control mechanisms were implemented:multi-stage verification: The annotation process was conducted in three stages, comprising initial labeling, independent cross-verification, and a final expert review by a structural engineer; uncertainty masking: Probabilistic labels assigned to ambiguous regions (e.g., crack termini or blurred contours); geometric validation: Automated consistency checks for crack width and length based on structural rules.

5.2. Training Strategy

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer for a total of 100 epochs. Each epoch consisted of approximately 1000 mini-batches, with a batch size of 8. This configuration strikes a balance between memory efficiency and convergence speed.

The initial learning rate was set to and adjusted dynamically using a cosine annealing schedule. Momentum terms were set to and . A weight decay of was applied to prevent overfitting and enhance generalization.

All experiments were conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. The training environment was configured with CUDA 11.3 and cuDNN 8.2. As quantified in Table 4, the training setup was designed to ensure stable convergence while maintaining deployment efficiency.

Table 4.

Training configuration details.

To enhance generalization while preserving crack topology, this study implements real-time augmentation:

Binary masks are softened using Gaussian kernel smoothing to handle annotation uncertainty:

where Z normalizes values to . This converts hard labels to probabilistic targets, improving boundary learning [40].

This study proposes Edge IoU to specifically evaluate thin crack delineation capability. Using Canny edge detector with (, low = 0.1, high = 0.3), we extract 1-pixel wide edges from both prediction and ground truth. The metric calculates:

where is the indicator function. This strict measurement reflects structural integrity preservation for safety-critical inspections.

5.3. Ablation Study

This study conducts comprehensive ablation studies on DamCrackSet-1K validation set to validate our design choices. All experiments use 512 × 512 crops with batch size 8, trained on 1×RTX 3090 GPUs.

5.3.1. Backbone Architecture Analysis

The experimental results demonstrate the superiority of our enhanced backbone architecture across multiple performance metrics. As quantified in Table 5, our modified MobileNetV2 achieves competitive performance with 67.9% mIoU, representing a 2.1% improvement over the baseline MobileNetV2 and a 3.0% advantage over ResNet-50. The architecture also delivers the best Dice score (80.3%) and recall (76.6%), while maintaining competitive precision (86.7%). Notably, our model achieves this performance with only a marginal increase in inference time (13.1 ms/img vs. 12.4 ms/img) compared to the original MobileNetV2, while being significantly faster than both ResNet-50 (18.7 ms/img) and EfficientNet-B3 (15.2 ms/img). These results validate our design choices in balancing accuracy and efficiency for practical deployment scenarios.

Table 5.

Ablation on Backbone Networks.

Through task-oriented optimization of MobileNetV2, this study achieves concurrent improvements in crack detection accuracy and lightweight design at the backbone level. The resulting model markedly enhances crack feature representation while maintaining a low parameter count and minimal inference overhead, enabling direct deployment on low-power embedded devices or UAV platforms. This approach effectively satisfies the stringent real-time and resource-efficiency requirements of long-term on-site dam inspections, offering a practical technical pathway for crack detection in complex environments.

5.3.2. Transformer Block Design

Table 6 validates the superiority of our cascaded group attention mechanism. Our design achievescompetitive 69.20% mIoU while using 58% fewer parameters and 64% less computation than global attention baselines. The 2.95% mIoU gain over local window attention demonstrates enhanced capability in modeling long-range crack dependencies through multi-scale group interactions. Remarkably, the FLOPs reduction from 8.2 G to 2.9 G enables efficient deployment without sacrificing structural awareness critical for crack continuity analysis.

Table 6.

Ablation on Attention Mechanisms.

The attention module proposed in this study markedly enhances crack detection accuracy while preserving overall lightweight design. With an extremely low parameter count and computational complexity, it strengthens the modeling of long-range dependencies, thereby avoiding prediction interruptions and edge losses in dam crack detection that are typically caused by local-sum or window-based attention mechanisms. By integrating a multi-scale interaction mechanism into the key feature fusion stage, the module establishes a more comprehensive global–local context association, ensuring complete preservation of crack geometric continuity. Experimental results confirm that this design not only delivers consistent numerical improvements but also provides more reliable structural detection for long cracks and intersecting crack networks in dam inspections.

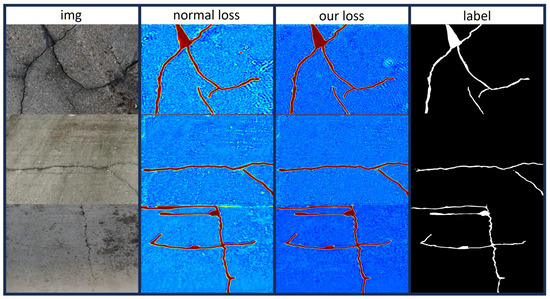

5.3.3. Loss Function Components

To balance learning between crack regions and edge details, this study designed a dynamic loss weight scheduling strategy. Specifically, the parameter is linearly decreased from 0.7 to 0.3, with a decay of 0.1 every 10 epochs. This strategy aims to enhance class discrimination during the early training stages while emphasizing edge refinement in later stages.

This study also experimented with alternative scheduling methods, such as a smaller step decay (decreasing 0.05 every 10 epochs) and exponential decay (), but none outperformed the current scheme Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of different scheduling strategies.

The final loss integrates both components through adaptive weighting:

where evolves from 0.7 to 0.3 during training, initially emphasizing class balance then refining edges.

The class-balancing term is formulated as a weighted binary cross-entropy loss:

where N is the number of training samples, denotes the ground-truth crack label of pixel i, is the predicted probability, and is the class weight for balancing foreground and background samples.

Edge-RefinementTerm

To enforce smooth and coherent crack boundaries, the edge-refinement loss is defined as:

where denotes the number of boundary pixels and measures the boundary smoothness penalty at pixel j. The intermediate computation term is defined as:

where , , , and c are smoothing parameters. This formulation compresses the penalty for small-error regions to avoid excessive punishment, while applying stronger constraints in large-error regions, thereby improving the precision of boundary depiction. Here, denotes the absolute value of .

Although our loss does not explicitly compute curvature, we term it ‘Curvature-Aware’ because its boundary-smoothness penalty implicitly constrains local geometric variation, effectively achieving curvature-aware regularization without computing curvature directly.

As quantified in Table 8, the proposed Curvature-Aware loss achieves the highest mIoU of 69.20%, outperforming the standard focal loss by an absolute improvement of 2.75%. Benefiting from the combination of class-balancing supervision and the proposed curvature-based boundary regularization, our adaptive weighting mechanism leads to superior segmentation quality, with the highest Dice score (81.32%) and Precision (84.60%) among all variants. This confirms the effectiveness of Curvature-Aware in enhancing crack boundary delineation.

Table 8.

Ablation on Loss Components.

To intuitively illustrate the advantages of the proposed algorithm over the baseline method in optimizing crack boundaries, this study conducted a visual analysis on three different types of concrete crack images. The figure shows comparisons among the original images (“img”), predictions obtained using the baseline loss (“normal loss”), predictions generated by our proposed loss (“our loss”), and the ground truth labels (“label”). Compared with the baseline algorithm, our proposed loss function demonstrates significant superiority in crack edge detection, capturing finer and more precise crack boundaries, thereby effectively reducing false detections caused by coarse edge predictions from the baseline. Moreover, predictions from our improved method exhibit cleaner backgrounds, substantially decreasing the interference from background noise in crack detection, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Crack Edge Optimization Using Different Loss Functions.

5.3.4. Component Combinations

As quantified in Table 9, the full integration of our co-designed components—including the MobileNetV2 backbone, cascaded group attention, and the proposed Curvature-Aware loss—achieves an mIoU of 69.20%, representing an absolute improvement of 5.93% over the baseline configuration using Focal Loss (63.27%). Meanwhile, the inference latency only increases marginally by 1.7 ms (from 12.4 ms to 14.1 ms), demonstrating the efficiency of our design. The progressive gains observed by introducing either the attention module or loss modification alone further confirm the complementary benefits of each component.

Table 9.

Component Combination Analysis.

5.4. Comparative Experiments

This study evaluates our method against competitive segmentation architectures on the DamCrackSet-1K test set. All speed evaluations are performed on a computer equipped with an RTX 3090 GPU, using a 512 × 512 input with a batch size of 1, excluding I/O time. FPS is calculated as 1000 ms/per-image latency.

As quantified in Table 10, the proposed method achieves a 0.85% improvement in mIoU compared to DeepLabV3+, and a 3. 2% increase in edge IoU relative to Mask R-CNN, indicating improved segmentation accuracy and boundary localization. Furthermore, the model achieves a frame rate of 70.9 FPS, which is substantially higher than the 28.1 FPS reported for UNet, suggesting its potential applicability in real-time dam inspection tasks.

Table 10.

Comparative results with competitive methods.

It should also be noted that several recent crack-specific models—such as Mamba-Crack-Net [41], Crack-SAM [42] and MAX-Net [43] are not included in our quantitative comparison. Although these methods are relevant to thin-crack extraction, at the time of our experiments no stable, reproducible implementations or pretrained weights were publicly available for evaluation on our DamCrackSet-1K dataset. Retraining these models from scratch would require substantial computational resources and custom training pipelines, making the comparison less fair under our unified experimental settings. In addition, many of these methods rely on heavy foundation backbones or multi-stage inference, which exceed the memory and latency constraints of the edge-oriented deployment targeted in this work. For fairness and reproducibility, we therefore restrict our benchmark to widely adopted baselines that can be trained and executed under identical hardware and training conditions.

5.5. Visual Comparison

To better illustrate crack-detection performance on concrete dams, a visual comparison focused on precise edge extraction is provided. Segmentation results are presented for two representative crack types, fine, low-contrast cracks and intersecting cracks. This categorization offers clearer insights into algorithm behavior and enabling a more effective comparative assessment of the generalizability and robustness of each method across varying complexities.

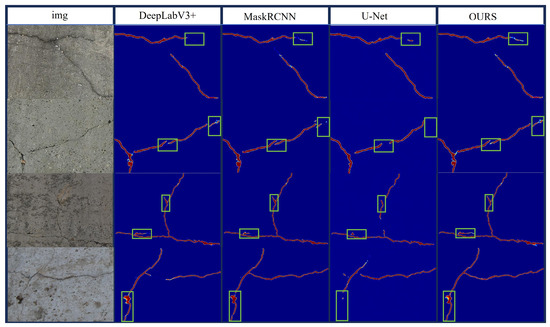

5.5.1. Intersecting Cracks

As illustrated in Figure 9, intersecting cracks exhibit complex geometries, and many existing algorithms produce discontinuities or shape distortions in these regions. Visual comparisons show that DeepLabV3+ and Mask R-CNN, due to over-smoothing, often merge multiple branches near junctions into a single widened crack, resulting in the loss of fine angular details; U-Net frequently yields broken branches, indicating limited ability to preserve complex topological connectivity.

Figure 9.

Visual comparison for intersecting cracks. From left to right: raw image, DeepLabV3+, Mask R-CNN, U-Net, and OURS.

In contrast, the proposed MTC-Net produces continuous, sharply delineated contours at intersections and fully preserves the original morphology and width of each branch. Even in scenes with multiple intersections, it achieves precise branch separation without performance degradation. This advantage stems from its attention mechanism, which effectively fuses contextual information with local edge cues, enabling the network to maintain overall crack continuity and geometric fidelity in structurally complex regions.

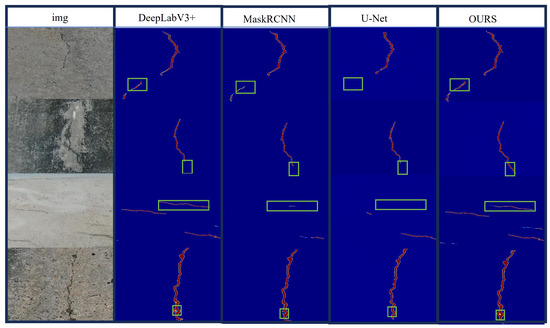

5.5.2. Fine and Low-Contrast Cracks

As illustrated in Figure 10, microcracks and low-contrast cracks are particularly challenging to detect due to their minimal color contrast with the background, resulting in frequent missed detections in existing methods. Specifically, DeepLabV3+ and Mask R-CNN often fail to capture fine crack segments, while U-Net, although covering a broader area, generates a substantial number of false positives and false negatives in low-contrast regions.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison for fine and low-contrast cracks. From left to right: raw image, DeepLabV3+, Mask R-CNN, U-Net, and OURS.

The proposed MTC-Net significantly strengthens responses to weak edge cues through the geometry-sensitive weighting mechanism of the Curvature-Aware loss. Even under extremely low visual contrast, it can reconstruct a continuous, width-accurate trajectory along the entire crack while maintaining zero false positives in background regions and effectively suppressing noise. This optimal balance between accuracy and completeness demonstrates the robustness and practical applicability of the method for on-site dam inspections.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the difficulties of characterizing fine cracks, the limitations of detection accuracy, and the constraints on real-time deployment imposed by model size in concrete dam crack detection. It then proposes a systematic solution, which includes constructing DamCrackSet-1K (a high-resolution dataset with pixel-level annotations covering multiple crack scenarios), designing the lightweight semantic segmentation framework MTC-Net (which integrates a MobileNetV2 encoder with Enhanced Transformer modules to achieve effective global–local feature fusion), and proposing a geometry-sensitive Curvature-Aware loss to alleviate pixel-level class imbalance for fine cracks and to strengthen thin-crack edge delineation.

Experimental results show that, while significantly reducing the number of parameters and computational overhead, the proposed method maintains stable segmentation performance and high inference speed under challenging conditions (e.g., shadows, low illumination, corrosion, intersecting cracks, and fine cracks), demonstrating strong potential for real-time edge deployment. Future work will focus on enhancing the generalization and engineering adaptability of the model, including the incorporation of explainable artificial intelligence mechanisms to improve decision credibility; conducting targeted optimizations for intersecting cracks, low-contrast cracks, and corrosion-associated cracks; leveraging domain adaptation and federated learning to enable high-precision transfer across diverse scenarios and devices; integrating multi-modal data such as laser scanning and infrared thermal imaging to construct three-dimensional crack models; and performing long-term operational testing on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and underwater remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) while applying lightweight inference and model pruning techniques to achieve real-time inspection capabilities.

Author Contributions

Study conception, methodology design, and experimental planning, J.H.; data acquisition, formal analysis, and statistical data processing, J.H. and B.H.; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, F.K.; writing—original draft, J.H.; writing—review & editing, F.K. and B.H.; review and editing for submission and journal requirements compliance, B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4703404).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The DamCrackSet-1K dataset and implementation code are not publicly available, but can be provided upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ghannadi, P.; Kourehli, S.; Nguyen, A.; Oterkus, E. Letter to the Editor: A brief insight into the NDT in the UK. e-J. Nondestruct. Test. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Kang, F.; Li, J.; Wang, F. Displacement prediction model for high arch dams using long short-term memory based encoder-decoder with dual-stage attention considering measured dam temperature. Eng. Struct. 2023, 280, 115686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Li, J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y. Structural health monitoring of concrete dams using long-term air temperature for thermal effect simulation. Eng. Struct. 2019, 180, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, F.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Yao, Y. Data-Augmented Manifold Learning Thermography for Defect Detection and Evaluation of Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheradmandi, N.; Mehranfar, V. A critical review and comparative study on image segmentation-based techniques for pavement crack detection. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 321, 126162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, D.H.; McQueen, J.M. A Study of Manual vs Automated Pavement Condition Surveys; Auburn University: Auburn, AL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, B.L. Stéphane Mallat: A Wavelet Tour of Signal Processing, 2nd Edition. Comput. Music. J. 2007, 31, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, D.; Kharoufa, Z.; Wong, E.; Shaw, L.G. Pavement Distress Analysis Using Image Processing Techniques. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 1991, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Zalama, E. Automated Visual Inspection of Road Surface Cracks. In Proceedings of the International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction, Bratislava, Slovakia, 24–27 June 2010; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Zakeri, H.; Nejad, F.M.; Fahimifar, A.; Torshizi, A.D.; Zarandi, M.F. A multi-stage expert system for classification of pavement cracking. In Proceedings of the 2013 Joint IFSA World Congress and NAFIPS Annual Meeting (IFSA/NAFIPS), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–28 June 2013; pp. 1125–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Banharnsakun, A. Hybrid ABC-ANN for pavement surface distress detection and classification. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber 2017, 8, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Li, S. Concrete dam deformation prediction model for health monitoring based on extreme learning machine. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2017, 24, e1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laqsum, S.A.; Zhu, H.; Haruna, S.I.; Ibrahim, Y.E.; Amer, M.; Al-Shawafi, A.; Ahmed, O.S. Impact and Failure Analysis of U-Shaped Concrete Containing Polyurethane Materials: Deep Learning and Digital Imaging Correlation-Based Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Kang, F.; Li, X.; Zhu, S. Underwater dam crack image generation based on unsupervised image-to-image translation. Autom. Constr. 2024, 163, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Huang, B.; Wan, G. Automated detection of underwater dam damage using remotely operated vehicles and deep learning technologies. Autom. Constr. 2025, 171, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kang, F.; Wan, G.; Li, H. Automatic operational modal analysis for concrete arch dams integrating improved stabilization diagram with hybrid clustering algorithm. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kang, F.; Zhu, S.; Li, J. Data-driven deformation prediction model for super high arch dams based on a hybrid deep learning approach and feature selection. Eng. Struct. 2025, 325, 119483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6230–6239. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zim, A.; Iqbal, A.; Al-Huda, Z.; Malik, A.; Kuribayashi, M. EfficientCrackNet: A Lightweight Model for Crack Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 6279–6289. [Google Scholar]

- Su, G.; Qin, Y.; Xu, H.; Liang, J. Automatic real-time crack detection using lightweight deep learning models. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Zhou, C.; Ruan, Y.; Li, Y. MobileNetV2 model for image classification. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Information Technology and Computer Application, Guangzhou, China, 18–20 December 2020; pp. 476–480. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 2704–2713. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-maqtari, O.; Peng, B.; Al-Huda, Z.; Al-Malahi, A.; Maqtary, N. Lightweight Yet Effective: A Modular Approach to Crack Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 7961–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, S.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Teng, Q. A novel convolutional neural network for enhancing the continuity of pavement crack detection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Peng, B.; Zhai, D. Boundary-Aware Axial Attention Network for High-Quality Pavement Crack Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 13555–13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yan, F.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Xu, S.; Liu, S. TCI-Net: Structural Feature Enhancement and Multi-Level Constrained Network for Reliable Thin Crack Identification on Concrete Surfaces. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 65604–65616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompanets, A.; Duits, R.; Pai, G.; Leonetti, D.; Snijder, H.B. Loss function inversion for improved crack segmentation in steel bridges using a CNN framework. Autom. Constr. 2025, 170, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.; Li, W.; Vercauteren, T.; Ourselin, S.; Jorge Cardoso, M. Generalised Dice overlap as a deep learning loss function for highly unbalanced segmentations. In Proceedings of the MICCAI Workshop on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis, Québec City, QC, Canada, 14 September 2017; Volume 10553, pp. 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, S.; Erdogmus, D.; Gholipour, A. Tversky loss function for image segmentation using 3D fully convolutional deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging, Québec City, QC, Canada, 10 September 2017; pp. 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Dai, B.; Wu, W.; Loy, C.C. Focal frequency loss for image reconstruction and synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 13919–13929. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Dasarathy, G.; Berisha, V. Regularization via structural label smoothing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Online, 26–28 August 2020; pp. 1453–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, X.; Sheng, Y.; Shen, J.; Shan, Y. Topology-aware Mamba for Crack Segmentation in Structures. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.19894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, G.; Chen, P.H.; Hosseini, M.S. Segment Any Crack: Deep Semantic Segmentation Adaptation for Crack Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.14138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wen, X.; Yan, C.; Guo, Y.; Cao, R. MA-Xnet: Mobile-Attention X-Network for Crack Detection. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).