An Optimization Procedure for Improving the Prediction Performance of Failure Assessment Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Improved Guo-Ni Model (IGNM)

2.1. Establishment Principles

2.1.1. Evaluation Indicator System (EIS)

- Stability is the FAM’s inherent characteristic reflecting the cognitive level, which consists of three indicators: correlation (C1), multi-modality (C2) and dispersion (C3). C1 represents the correlation coefficient (Rn) between PA and the experimental burst pressure Pexp. C2 represents the distributional properties of PA’s probability density. In details, C2 = 1 when the best-fit distribution is clearly single-peaked, while C2 = 3 when the generic single-peaked distributions are rejected or C2 = 2 otherwise. C3 is the Coefficient of Variation (COV) of PA.

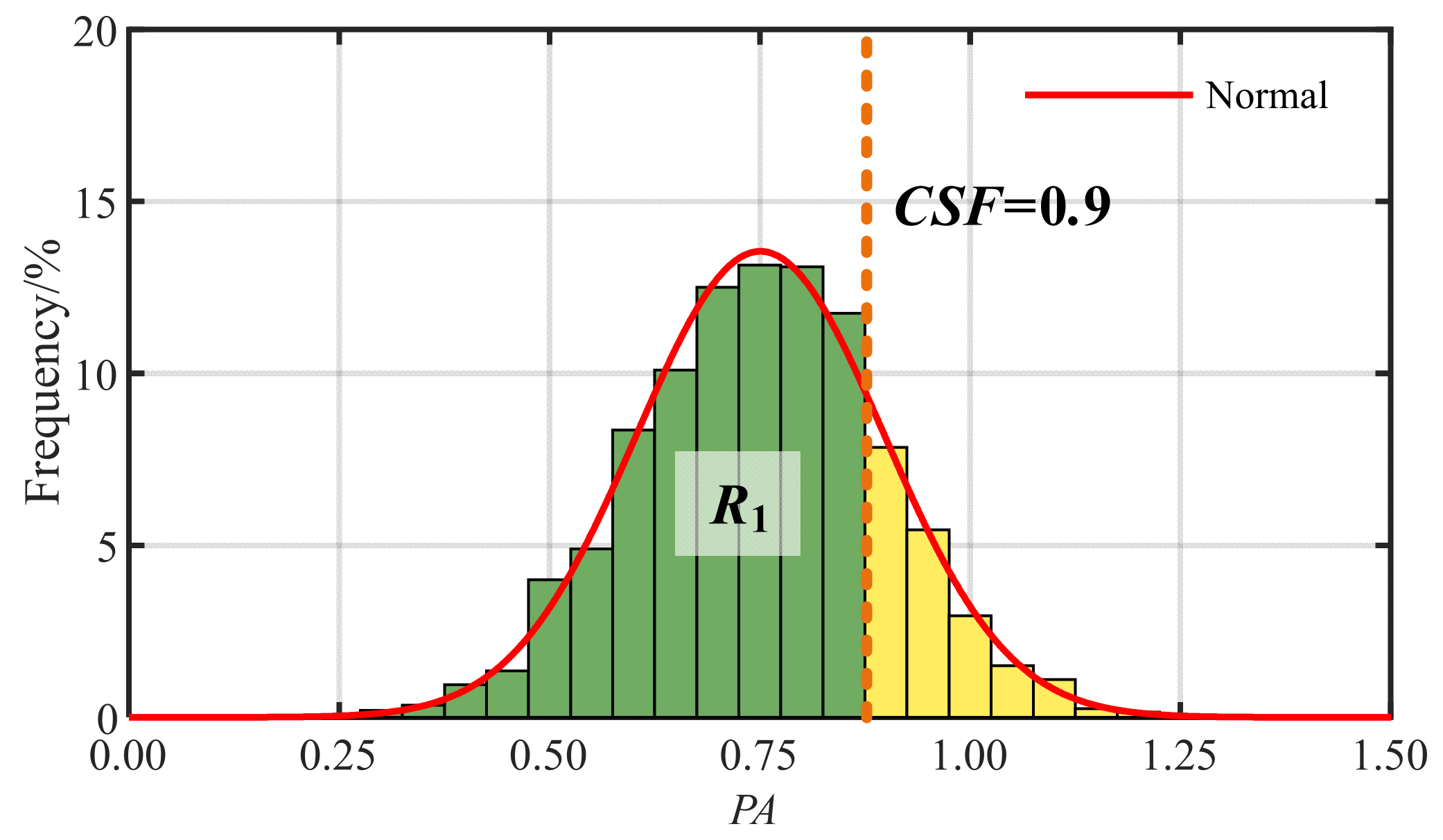

- Distributional Location Characterizations (DLCs) are superficial properties that are easy to observe and obtain. DLCs consist of four indicators: risk (C4), conservatism (C5), robustness (C6) and accuracy (C7). C4 is the probability that the PA is greater than 1, C5 is the probability that the PA is less than 0.5 and C6 is the probability that the PA is between 0.5 and 1. C7 is the absolute difference between 1 and the meaning of PA.

2.1.2. Evaluation Mathematical Models (EMMs)

2.1.3. Integration Processing

2.2. Flowchart

- Step 1: Calculate the values of seven PP evaluation indicators in EIS based on experimental pressure Pexp and FAM’s PA. EIS describes FAM’s PP from multiple dimensions consisting of stability (correlation C1, multi-modality C2 and dispersion C3) and Distribution Location Characterizations DLCs (risk C4, conservatism C5, robustness C6 and accuracy C7). Therefore, the subsequent EIS-based overall score s output by IGNM can represent the various engineering adaptability of PP to the greatest degree.

- Step 2: Obtain sub-scores si (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) with the weights output by the Best-Worst Method (BWM) and four multi-criteria decision-making models acknowledged by numerous experts, including SWM, TOPSIS, VIKOR and PROMETHEE II. Notably, BO and OW’s settings in BWM are able to affect indicators’ weights, thereby adjusting the contribution of each indicator to the overall score.

- Step 3: Integration processing to obtain the overall s, where the characteristics of si (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) output from step 2 must first be unified with Equations (4) and (5) before integrating by the averaging method with Equation (6). Notably, IGNM’s output s covers various core decision perspectives, ranging from absolute scoring to relative comparison and from comprehensive capacity to weakness avoidance, thereby significantly enhancing the credibility and acceptability of PP evaluation and quantification.

3. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

4. Optimization Procedure

4.1. Basic Definition

4.1.1. Fitness

4.1.2. Particles

4.2. Flowchart

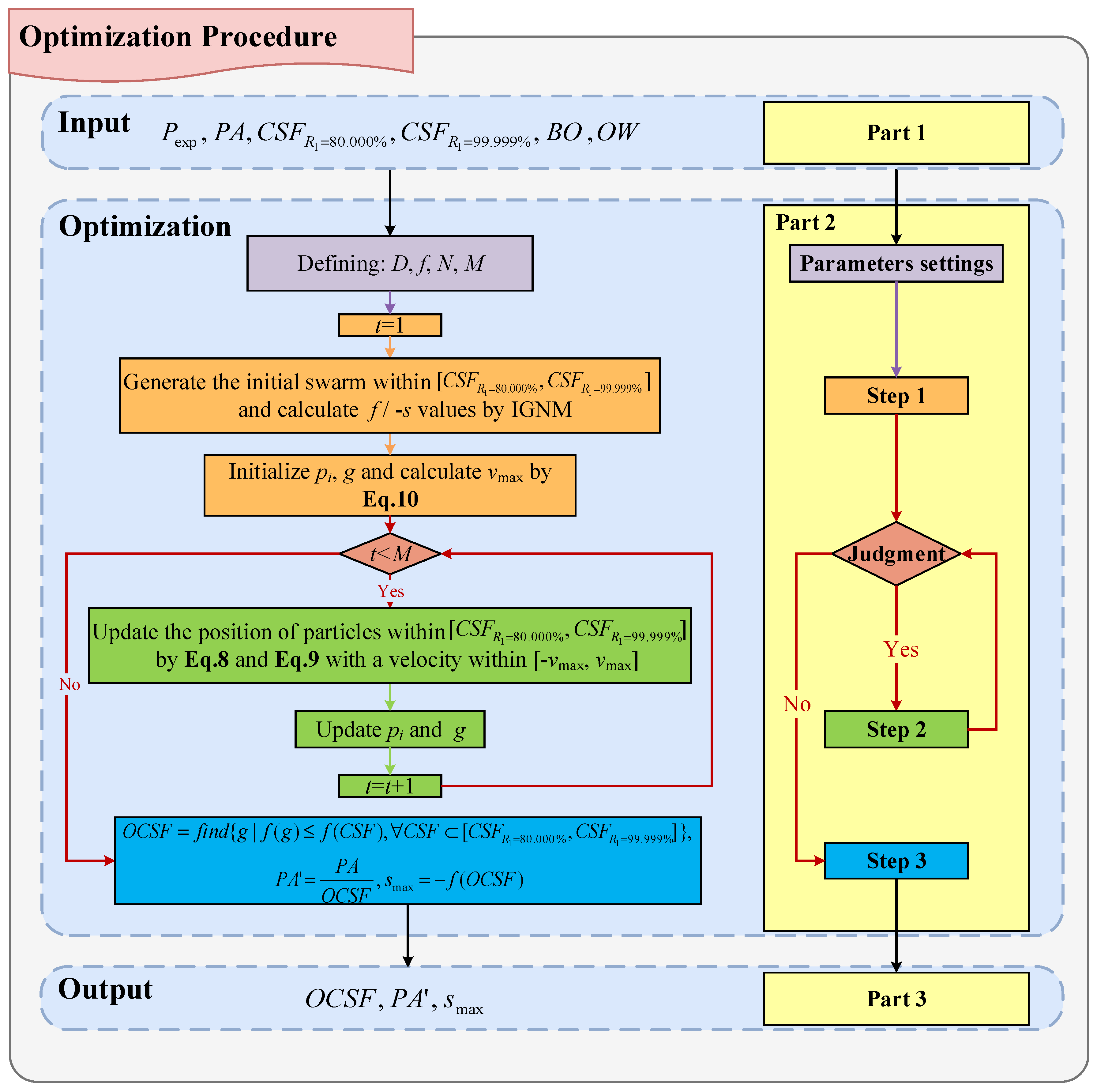

- (1)

- Part 1: Input. Input parameters cover six elements, including the experimental pressure (Pexp), FAM’s Prediction Accuracy (PA), minimum and maximum CSF values () and relative importance degrees among different indicators in EIS (BO and OW). Specifically, PA is calculated by Equation (1) where the Ppre values are determined by FAMs. are suggested by the values corresponding to FAM’s confidence level (R1) equaling to 80.000% and 99.999%, respectively. BO and OW are determined by users’ needs.

- (2)

- Part 2: Optimization. The optimization is carried out by PSO. Four optimization parameters are still required before iteration, including the dimension of particles (D), fitness (f), particles number (N) and the maximum number of iterations (M), as shown in purple box of part 2 in Figure 3. Specifically, D is defined as 1, since the particle is defined as an individual element CSF in the optimization procedure. f defined as −s, is calculated with IGNM. N and M’s default settings are 50 and 50, respectively, which can be adjusted by users’ needs. Next, the optimization process is divided into the following three steps, as shown in part 2 of Figure 3.

- Step 1: Initialization. The part covers three sub-steps as indicated in the orange boxes in part 2 of Figure 3. Firstly, the number of iterations t is set as 1. Then, the procedure generates the initial swarm within and calculates f, i.e., −s by IGNM. Finally, it initializes the local optimal particle pi of individual particle and the global optimal particle g of the swarm. Here, pi equals the particle’s own initial value. g is determined by the position of the minimum f value in the swarm. In addition, the maximum speed of particles vmax is determined by Equation (10).

- Step 2: Iteration. When the judgment condition (t is less than the maximum number of iterations M) is satisfied, the iteration is carried out, as shown in the pink area at part 2 of Figure 3. Iteration covers three sub-steps as indicated in the green boxes in part 2 of Figure 3. Firstly, the positions of particles are updated by Equations (8) and (9) in by a velocity in [−vmax, vmax]. Then, update the positions of pi and g corresponding to the latest minimum f value by that specific individual and the swarm, respectively. Finally, update t with t + 1 for next iteration.

- Step 3: Calculation. When this judgment condition (t is less than the maximum number of iterations M) is not satisfied, the calculation begins. Calculation includes three aspects as presented in a blue box in part 2 of Figure 3. Firstly, the optimal CSF (OCSF) is calculated, which equals to g value at the last iteration, i.e., the found CSF value corresponding to the minimum f value in . The second one is PA’ which is the ratio of the original input PA to OCSF calculated by Equation (13) and the last one is the maximum smax, i.e., −f(OCSF).

- (3)

- Part 3: Output. Output includes 3 parameters: OCSF, PA’ and smax.

5. Empirical Verification

5.1. Rationality of Fitness Setting

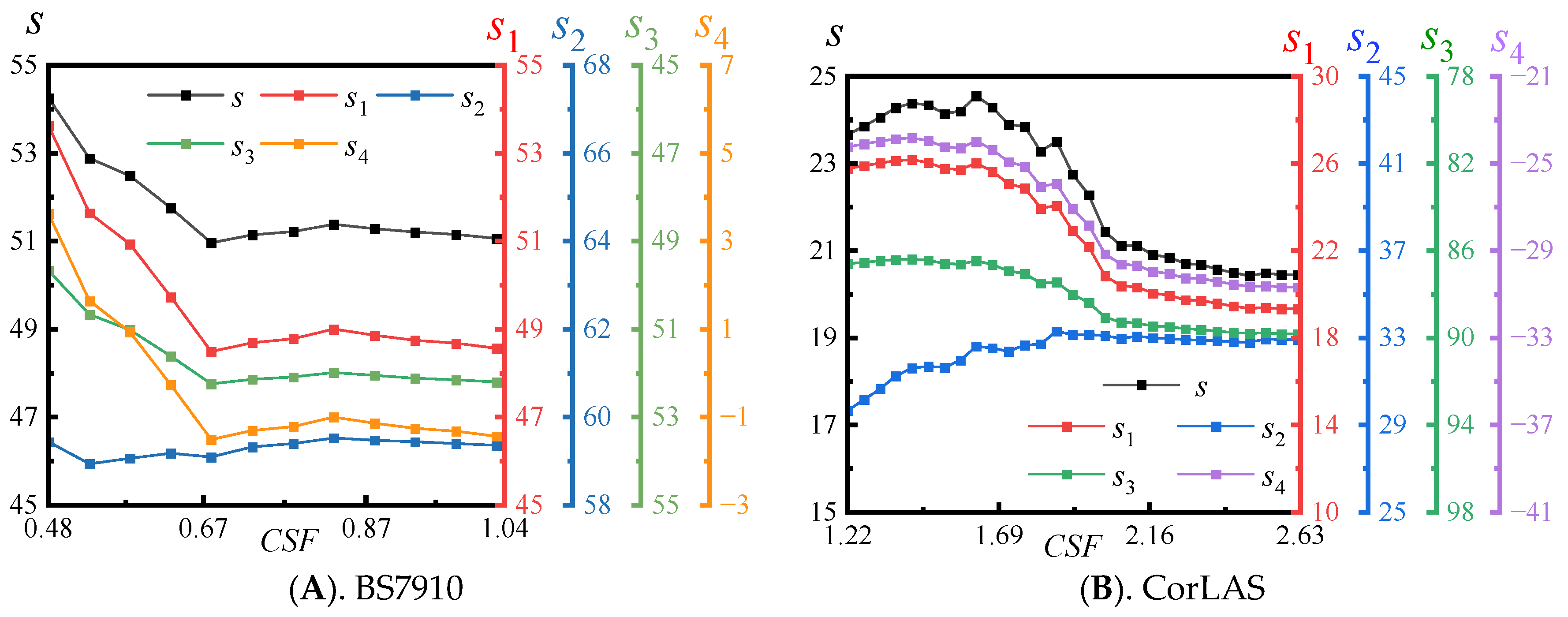

5.2. Optimization Effect

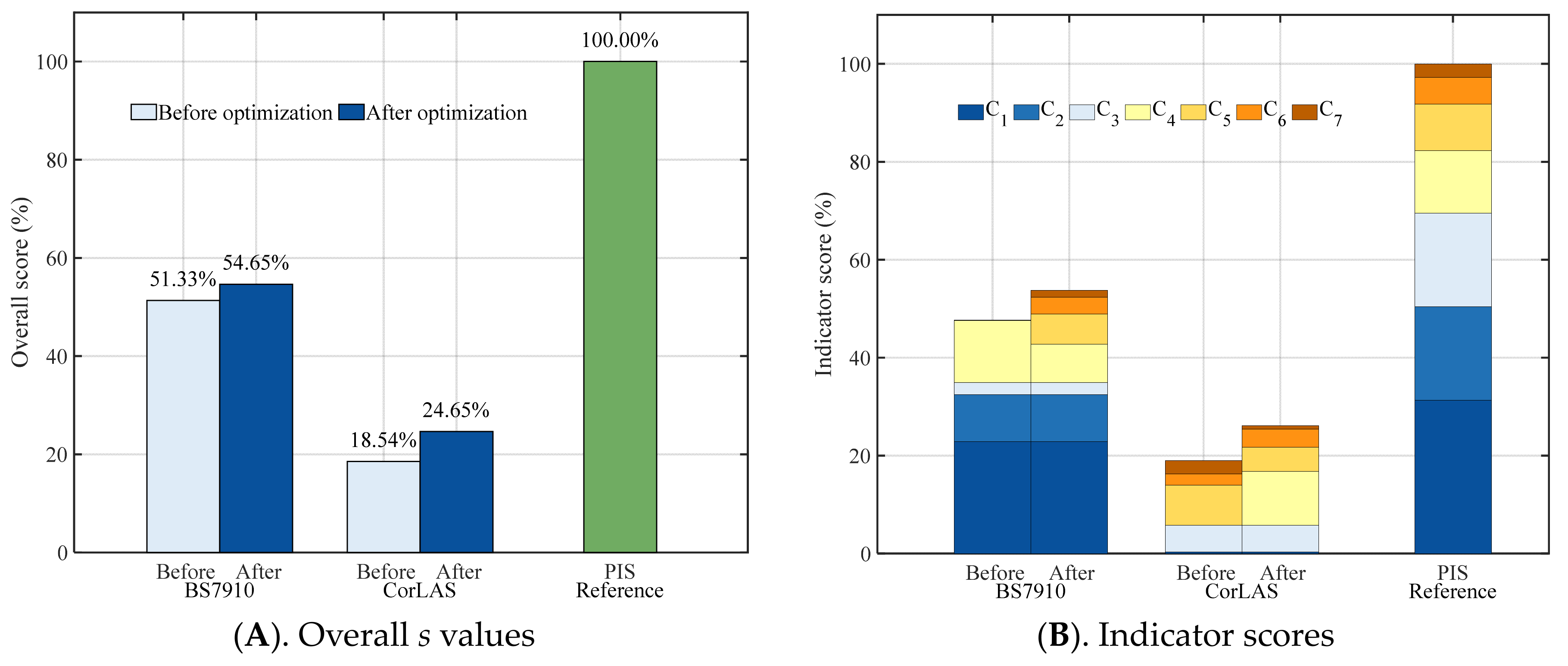

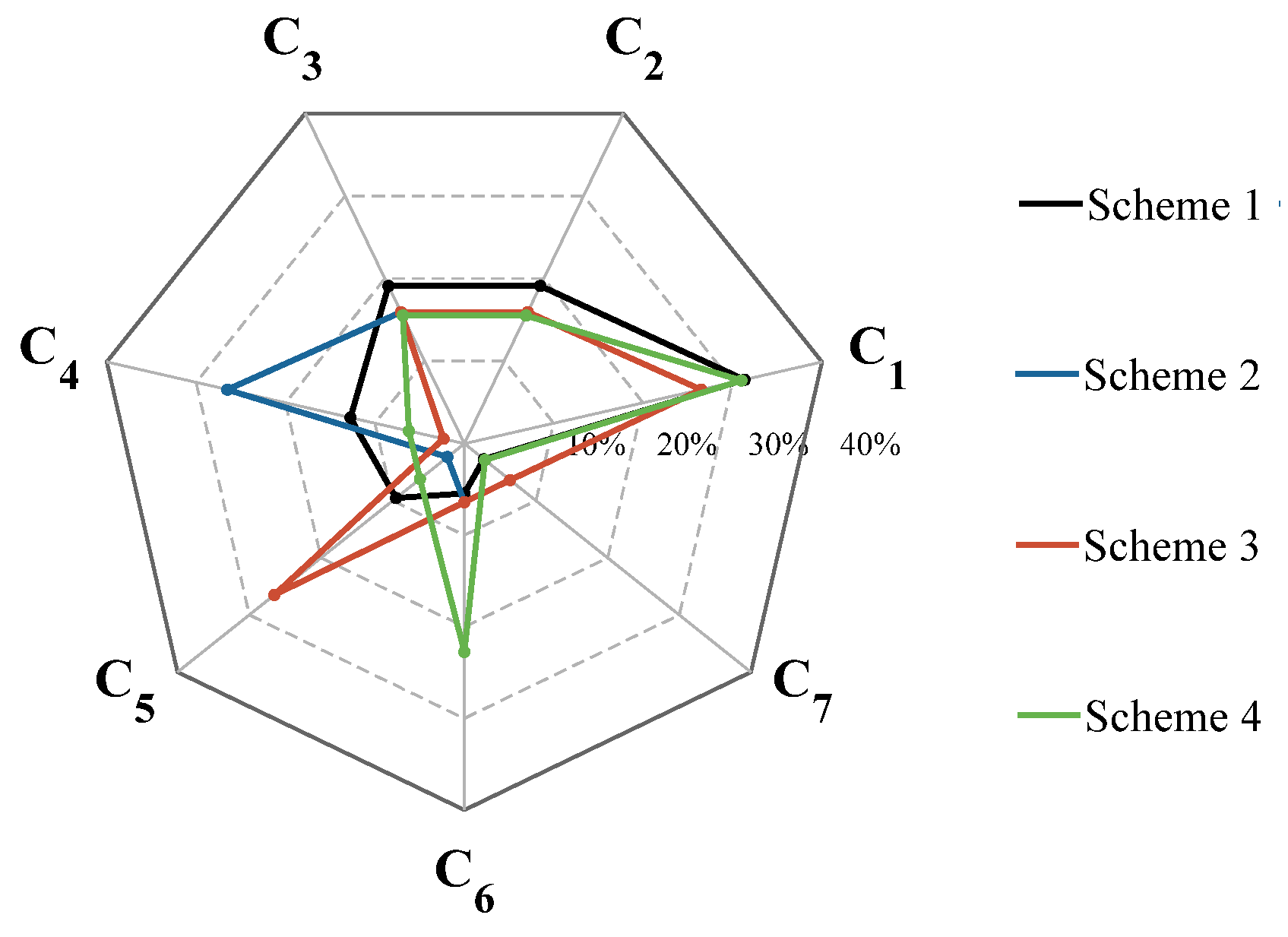

5.2.1. PP Scores

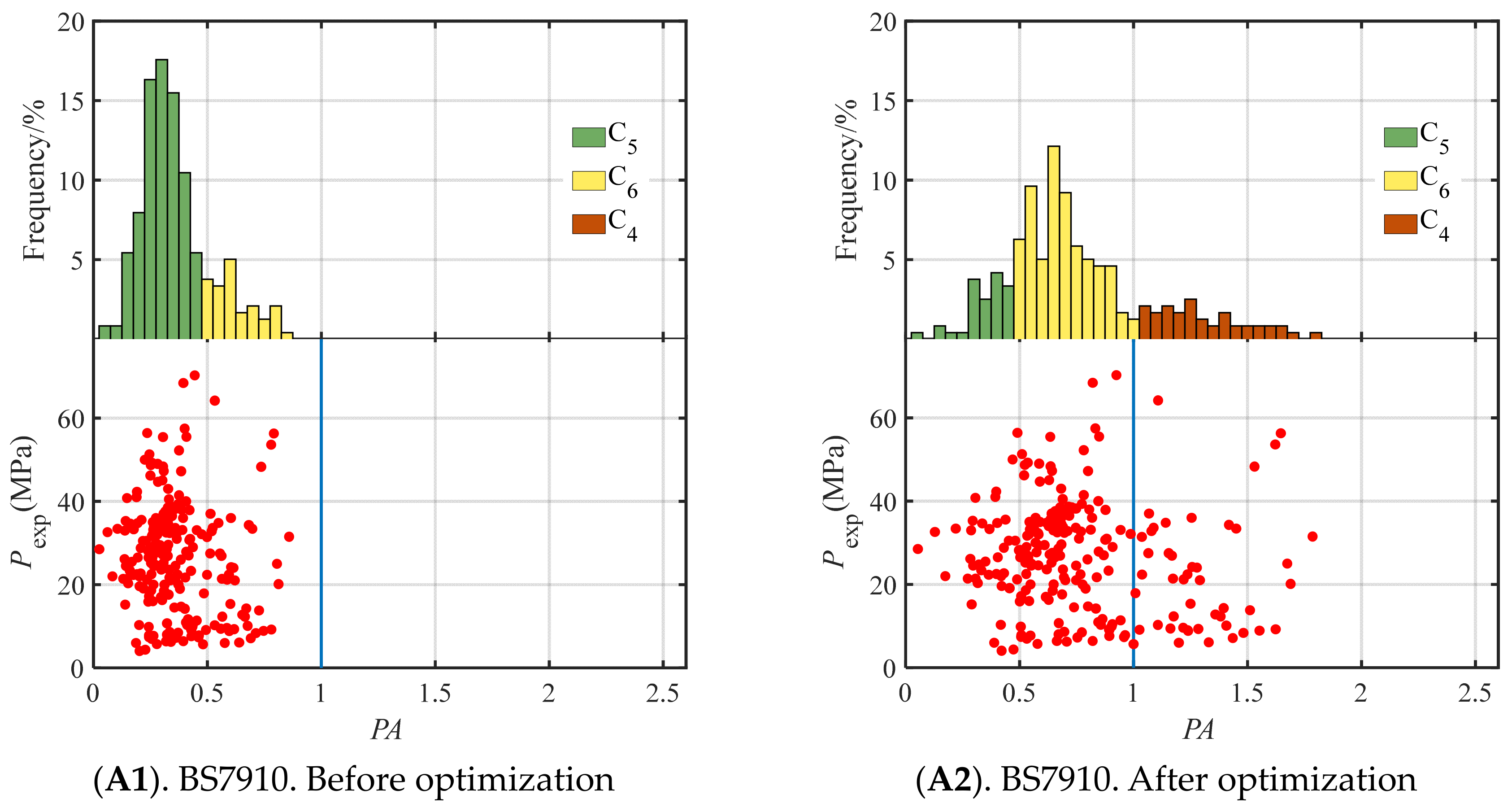

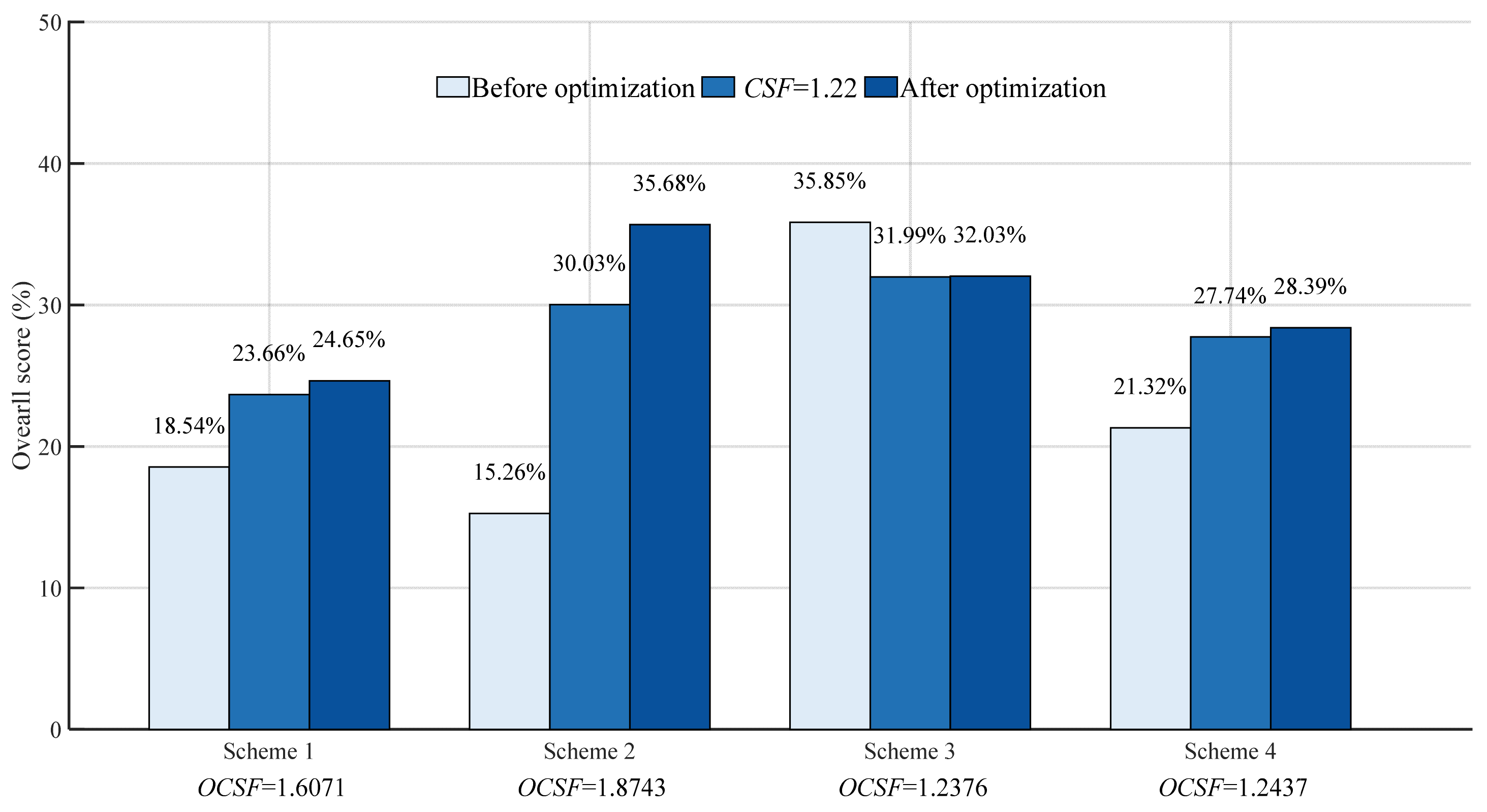

5.2.2. PA Distribution

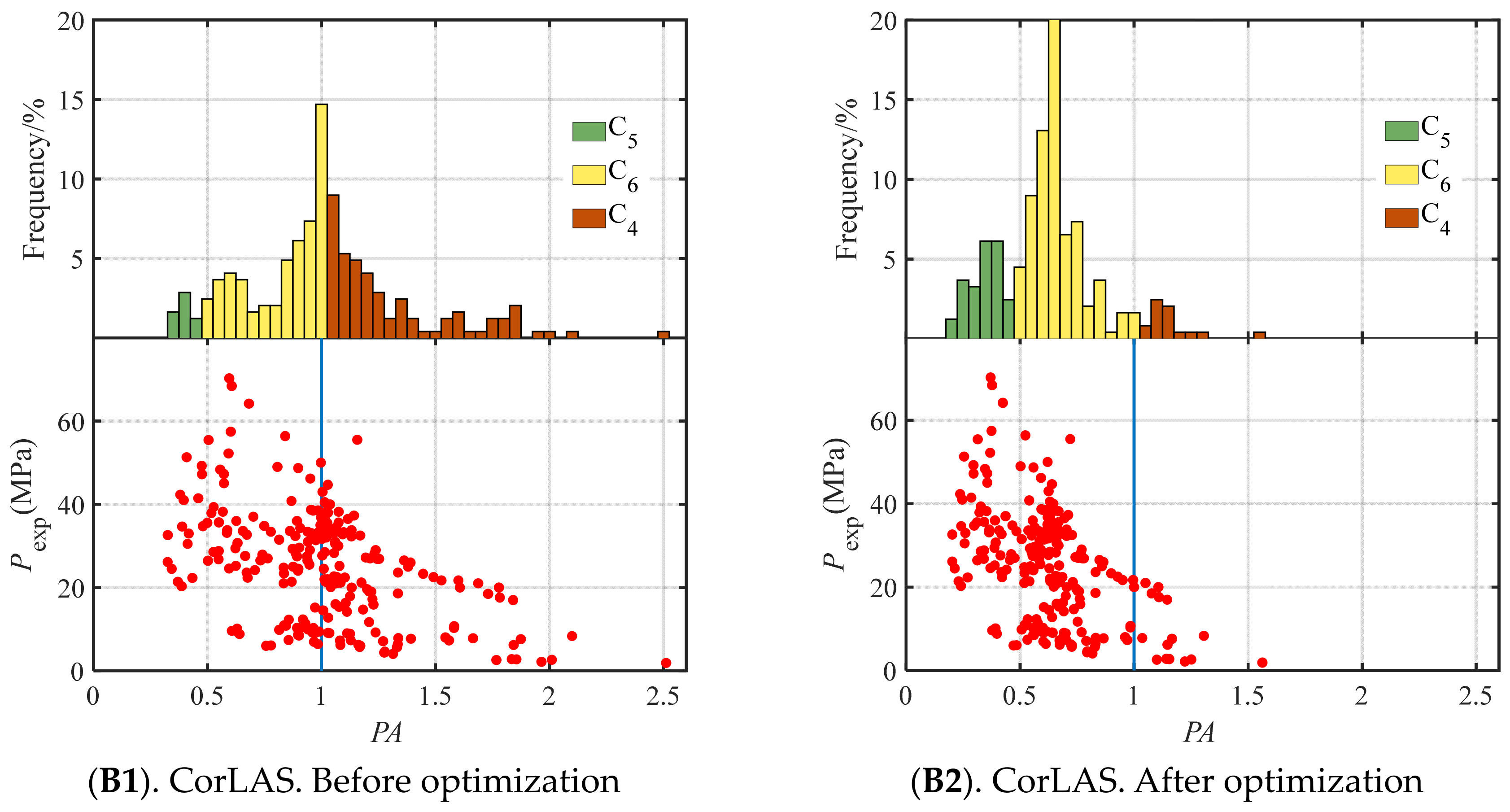

5.3. Tests on Application Preferences

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The convexity tests conducted for the fitness functions of BS7910 and CorLAS demonstrate that the IGNM-based fitness can not only successfully avoid the problem of ineffective optimization targeting a single decision-making model, but also effectively integrate the characteristics of various decision-making models for enhancing the comprehensiveness and robustness of the subsequent optimization. These findings validate the rationality and advantages of the optimization procedure.

- (2)

- Based on the procedure, BS7910 and CorLAS have been optimized with a set of initial parameters showing no significant preference for DLCs. The results indicated that, for PP’s overall scores, there is an s value improvement up to 3.32% for BS7910 and CorLAS’s s is also effectively improved with up to 6.09% increase, proving the validity of the procedure. For the specific scores in EIS, the scores for DLCs including risk C4, conservatism C5, robustness C6 and accuracy C7 have significantly changed, while stability shows no variation, revealing that the procedure achieves overall performance enhancement by modifying DLCs. As for Prediction Accuracy (PA) distribution, the optimized PA values of both FAMs show better balance for DLCs.

- (3)

- Three added application preference optimization tests conducted for CorLAS indicate that the optimization results can satisfy different prediction preferences which can be adjusted by modifying the relative importance degrees of DLCs, demonstrating the procedure’s excellent generalization capability. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the procedure can guarantee that the output results always meet the basic safety requirement for design of the mechanism, further proving the reliability and engineering value of the procedure.

- (4)

- The optimization procedure has been proven to effectively increase the PP of FAM by balancing DLCs, providing a new idea for the optimization control of FAM’s overall performance, i.e., utilizing a comprehensive evaluation model to set the goal about PP optimization. While the procedure has failed to change the stability of FAM prediction by scaling PA with CSF. The future research will continue to explore incorporating additional factors influencing the PA and other algorithms better suited to multidimensional optimization. Enriching the candidate solution dimensions enables non-linear adjustment of PA, thereby fundamentally optimizing the inherent characteristics of FAM. Furthermore, adding some physical constraints during the optimization process may allow the final optimized PA values to be fully less than 1 without being overly conservative, thus ensuring the output results fully meet the safety requirements for structural reliability assessment in the design. Additionally, considering the real-time nature of the input data, periodic optimization can be considered to enhance the procedure robustness.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, L.; Zhou, J.; Dai, Y. Time-dependent failure probability analysis of corroded pipelines based on different stochastic degradation processes. Acta Pet. Sin. 2019, 40, 1542–1552. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shuai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shuai, J.; Xie, D.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z. A novel framework for predicting the burst pressure of energy pipelines with clustered corrosion defects. Thin-Walled Struct. Part A 2024, 205, 112413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okodi, A.; Lin, M.; Yoosef-Ghodsi, N.; Kainat, M.; Hassanien, S.; Adeeb, S. Crack propagation and burst pressure of longitudinally cracked pipelines using extended finite element method. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2020, 184, 104115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnuvardhan, S.; Murthy, A.R.; Choudhary, A. A review on pipeline failures, defects in pipelines and their assessment and fatigue life prediction methods. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2023, 201, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Guo, S.; Zhang, R.; Frangopol, D.M. Prediction of burst pressure of corroded thin-walled pipeline elbows subjected to internal pressure. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 199, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 19624-2019; Safety Assessment for in-Service Pressure Vessels Containing Defects. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- BS 7910:2019; Guide to Methods for Assessing the Acceptability of Flaws in Metallic Structures. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2019.

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, W. Model error assessment of burst capacity models for energy pipelines containing surface cracks. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2014, 120-121, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, Q.; Leung, J.; Adeeb, S. Reliability-based assessment of cracked pipelines using monte carlo simulation technique with CorLAS™. In Proceedings of the ASME Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 17–22 July 2022; p. V002T03A051. [Google Scholar]

- Cosham, A.; Hopkins, P.; Leis, B. Crack-like Defects in Pipelines: The Relevance of Pipeline-specific Methods and Standards. In Proceedings of the International Pipeline Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 24–28 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, S.; Kariyawasam, S.; Pino, M.; Liu, T. Validate Crack Assessment Models with In-Service and Hydrotest Failure. In Proceedings of the International Pipeline Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 24–28 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Niffenegger, M.; Jing, Z. Statistical inference and performance evaluation for failure assessment models of pipeline with external axial surface cracks. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2021, 194, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Niffenegger, M.; Zhou, J. A novel procedure to evaluate the performance of failure assessment models. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedmohammadi, J.; Sarmadian, F.; Jafarzadeh, A.A.; Ghorbani, M.A.; Shahbazi, F. Application of SAW, TOPSIS and fuzzy TOPSIS models in cultivation priority planning for maize, rapeseed and soybean crops. Geoderma 2018, 310, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-S.; Shen, S.-L.; Zhou, A.; Xu, Y.-S. Novel model for risk identification during karst excavation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 209, 107435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal, J.R.S. Multi-criteria decision-making in the selection of a renewable energy project in spain: The Vikor method. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wang, X. A PROMETHEE II method based on regret theory under the probabilistic linguistic environment. IEEE Access 2020, 99, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dong, S.; Ling, J.; Zhang, L.; Cheang, B. A modified method for the safety factor parameter: The use of big data to improve petroleum pipeline reliability assessment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 198, 106892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiswendsida, K.J.; Huang, Q. Probabilistic burst pressure prediction model for pipelines with single crack-like defect. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2024, 207, 105084. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefner, J.F. Modified Ln-Secant equation improves failure prediction. Oil Gas J. 2008, 106, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, J. Fast and accurate prediction of failure pressure of oil and gas defective pipelines using the deep learning model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 108016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, W. Classification of failure modes of pipelines containing longitudinal surface cracks using mechanics-based and machine learning models. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2023, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, M.; Xiao, Z. Numerical simulation and ANN prediction of crack problems within corrosion defects. Materials 2024, 17, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wan, N.; Zhu, H. Reconstruction of structural acceleration response based on CNN-BiGRU with squeeze-and-excitation under environmental temperature effects. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 15, 985–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Matharu, J.S.; Parmar, K.S. A survey on Particle Swarm Optimization: Evolution, adaptations and practical implementations. Appl. Soft Comput. 2026, 186, 114016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Gül, M.; Zhu, H. Vibration-Based Structural Damage Identification under Varying Temperature Effects. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ling, Z.; Sun, C.; Lei, Y.; Xiang, C.; Wan, Z.; Gu, J. Two-stage damage identification for bridge bearings based on sailfish optimization and element relative modal strain energy. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2023, 86, 715–730. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Li, X.; Lei, Y.; Gu, J. Structural damage identification based on modal frequency strain energy assurance criterion and flexibility using enhanced Moth-Flame optimization. Structures 2020, 28, 1119–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Brunelli, M.; Rezaei, J. Consistency issues in the best worst method: Measurements and thresholds. Omega 2020, 96, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Fundamentals of the analytic network process- dependence and feedback in decision-making with a single network. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2004, 13, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. The Study on Failure Assessment of Defect Pipes; Dalian University of Technology: Dalian, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kiefner, J.F.; Maxey, W.A.; Eiber, R.J.; Duffy, A.R. Failure stress levels of flaws in pressurized cylinders. ASTM Spec. Tech. Publ. 1973, 536, 461–481. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, A.; Cronin, D.; Plumtree, A.; Kania, R. Experimental Testing and Evaluation of Crack Defects in Line Pipe. In Proceedings of the International Pipeline Conference, Calgary, AB, Canada, 27 September–1 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri, C.; Dotta, F. Numerical modeling of ductile crack extension in high pressure pipelines with longitudinal flaws. Eng. Struct. 2011, 33, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, G.; Demofonti, G. Fracture Properties of API X 100 Gas Pipeline Steels; Europipe: Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.D.; Selines, R.J. Structural integrity assurance of high-strength steel gas cylinders using fracture mechanics. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1988, 30, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staat, M. Plastic collapse analysis of longitudinally flawed pipes and vessels. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2004, 234, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, H.P.; Junker, G.; Merker, W. Fracture analysis of surface cracks in cylindrical pressure vessels applying the two-parameter fracture criterion (TPFC). Int. J. Pres. Ves. Pip. 1987, 29, 113–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocks, W.; Kunecke, G.; Wobst, K. Stable crack growth of axial surface flaws in pressure vessels. Int. J. Pres. Ves. Pip. 1989, 40, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, J.; Xu, K. Validation of failure assessment curve of linepipe containing cracks. J. Mech. Strength 2003, 25, 251–253. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.D. Experimental verification of fracture toughness requirement for leak- before-break performance for 155-175ksi strength level gas cylinders. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 1987, 109, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.D.; Smith, J.H.; Tribolet, R.O. Technical basis for flawed cylinder test specification to assure adequate fracture resistance of ISO high-strength steel cylinder. J. Press. Vessel. Technol. 1997, 119, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scheme | BO (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7) | OW (C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7) |

|---|---|---|

| Scheme 1-Initial | (1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9) | (9, 8, 8, 7, 6, 3, 1) |

| Scheme 2-Conservatism | (1, 2, 2, 1, 9, 5, 5) | (9, 8, 8, 9, 1, 5, 5) |

| Scheme 3-Risk | (1, 2, 2, 9, 1, 5, 5) | (9, 8, 8, 1, 9, 5, 5) |

| Scheme 4-Robustness | (1, 2, 2, 5, 5, 1, 5) | (9, 8, 8, 5, 5, 9, 5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Guo, L.; Shen, Z. An Optimization Procedure for Improving the Prediction Performance of Failure Assessment Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 4488. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244488

He Y, Guo L, Shen Z. An Optimization Procedure for Improving the Prediction Performance of Failure Assessment Model. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4488. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244488

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yan, Lingyun Guo, and Zhenzhong Shen. 2025. "An Optimization Procedure for Improving the Prediction Performance of Failure Assessment Model" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4488. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244488

APA StyleHe, Y., Guo, L., & Shen, Z. (2025). An Optimization Procedure for Improving the Prediction Performance of Failure Assessment Model. Buildings, 15(24), 4488. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244488