Abstract

Resonance is currently more of a mechanical engineering concept than a civil engineering one. This is because in earthquake engineering or science, there has not been one definitive predominant frequency of seismic action, which is something that the resonance concept requires: at least one excitation frequency should predominate. In fact, a literature review on seismic structural resonance indicates that the subject has not been studied much. Recently, however, when the seismic spectral analysis focus is shifted—disruptively—from the common acceleration to displacement, clear predominant periods of near-field earthquake records have been observed and published. Now, based on these new and clear seismic predominant frequencies, the objective of this paper is to verify and experience clear structural resonance in linear multiple-degrees-of-freedom building models. Clear resonant structural response will be defined as evident amplification in the global deformation (top-floor relative displacement) spectrum; moreover, an additional hypothesis is that these amplifications would occur near the novel earthquake predominant frequencies.

1. Introduction

Seismic structural resonance is a phenomenon characterized by a level of coincidence between the natural frequency of a building and the predominant frequency of ground motion, or the site period [1]. This frequency matching implies a notable amplification in the structural seismic response. In mechanical engineering, the concept is clearer as the input usually has a very neat predominant frequency, which is commonly associated with the sole operational velocity of rotating turbomachinery. That is, the “level of coincidence” in the definition at the start would plainly be “coincidence”. In civil or earthquake engineering, however, there is no (or has not been) neat predominant period of seismic motion; therefore, that “level of” has been required and the resonance topic, consequently, has not been extensively studied. In fact, mechanical engineers involved in earthquake engineering research have considered that “resonance response phenomena… are rarely mentioned in publications on earthquakes” [2] even though structural resonance has been noted in several major events; famously, in the Mexico earthquakes of 1985 and 2017 (interestingly, both on the same date: 19 September), and in the Loma Prieta (1989) and Northridge (1994) events [1,2].

Two primary research papers on seismic structural resonance, from the century’s end, had basically the same words for this engineering problem (both first pages): the “expected cause” of “surprising and unexpected heavy damage to modern buildings” is seismic resonance [3,4]. These two works were written after other major or “famous” earthquakes: Gediz (1970, Turkey) and Kobe (1995, Japan). A difference in language does appear when referring to the soil or ground “period”. Tezcan and Ipek wrote “predominant period of the soil” [3] while Takewaki writes “natural period of surface ground” [4]. This is expected because the first paper is based on estimating the predominant period of the ground through the common acceleration response spectrum (ARS) concept, whereas the second work is based on estimating the natural period of the ground. These two are different ideas, of course; to start, the predominant period requires a real earthquake, or a set thereof, while the natural period concept implies simply that the soil above bedrock is a vibratory system: there may never be a seismic event in the surround.

Approaches to seismic structural resonance as the latter, in which the strong and direct surface ground motion is unknown, unavailable or disregarded, can be divided in two types: (1) soil–structure interaction analyses with 2(3)-dimensional finite element models for soil and structure [4,5], and (2) ambient noise or microtremor studies based on the horizontal to vertical spectral ratio (HVRS) [6,7,8]. According to a comprehensive literature review we carried out, the majority of works on this topic of seismic structural resonance are of this type: HVRS-based ambient noise analyses. However, these studies are very limited geographically as each analyzes only one European city/town: Varazdin [6], Avellino [7] and Barcelona [8].

When real strong motion records at surface are available or considered, the HVRS concept has also been employed to define the predominant frequency of the seismic ground in structural resonance papers [9,10]. Nevertheless, the limitation in these studies is even higher or more than geographical as these deal with solely one earthquake: Adana (1998) [9] and Tesistan (2016) [10]. Now, in this case of availability of real seismic signals, the common ARS concept has been also utilized to identify the soil predominant period [2,11,12]; more importantly, in these studies there are less geotechnical limitations than in the previous ones. It is noted that the dozen research papers presented in this Introduction, as a result or summary of the complete literature review carried out, is a consequence of the fact explained at the start: that seismic structural resonance is not commonly treated in civil engineering literature, assertion in which by seismic structural resonance literature we mean a paper where a concrete match of input predominant frequency and structural natural frequency is analyzed. A main reason for this scarcity is, again, that there is no definitive predominant frequency of earthquakes [13].

Efforts to define general and clear predominant periods in ground motion have been indeed deemed unsuccessful, and this is because of the wide scattering in the results or large standard deviations in the found dominant frequencies in sets of records [13,14]; moreover, even when an individual spectrum is considered a clear predominance is not observed in general. However, it has been lately argued that this impossibility of defining a clear predominant frequency of seismic input may be only due to the persistence of basing the spectral analyses on acceleration [15]. In fact, when either the ground displacement record is employed (power spectral density analysis) [16,17] or the displacement response spectrum is considered [15], clearer predominant frequencies, ωp, have lately been discovered, in near-fault records. This important result or conclusion is based on two facts, that standard deviations are more reasonable, and that individual spectra do show clear peaks.

Based on those clearer predominant frequencies, the aim of this work is to observe and verify also clear structural resonance in linear multiple-degrees-of-freedom (MDOF) building models; additionally, to corroborate that this single spectral parameter, ωp [15], can characterize satisfactorily seismic spectral content, or the excitation in the frequency domain. The novelty is in that previous single-parameter spectral characterization were based on acceleration, either of the ground or as ARS, but these analyses in sets of records produced no statistically meaningful seismic resonant frequencies [13,14,15]; moreover, individual ARS do not show a clear peak or predominance either. Of course, the other or the main novelty in this work is to experience or technically witness seismic structural resonance, but not in vague and common terms but in the mathematical terms of the resonance concept which imply an input/system frequency match. This resonant behavior study will focus on the relative structural displacement or deformation; specifically, in this case of MDOF building models, the response variable of interest will be the displacement of the roof relative to ground, or global deformation. The reason is that engineers are mostly interested in resonance solely to avoid it, or to prevent structural or mechanical failure, and this type of failure is closely associated with mechanical strain and/or stress, or deformation. Finally, these same engineers will use the results herein in the clear sense of not designing buildings with natural frequencies close to the predominant frequencies established and confirmed; this technical recommendation could not be written this clearly before because there had not been definitive seismic predominant periods.

2. Method

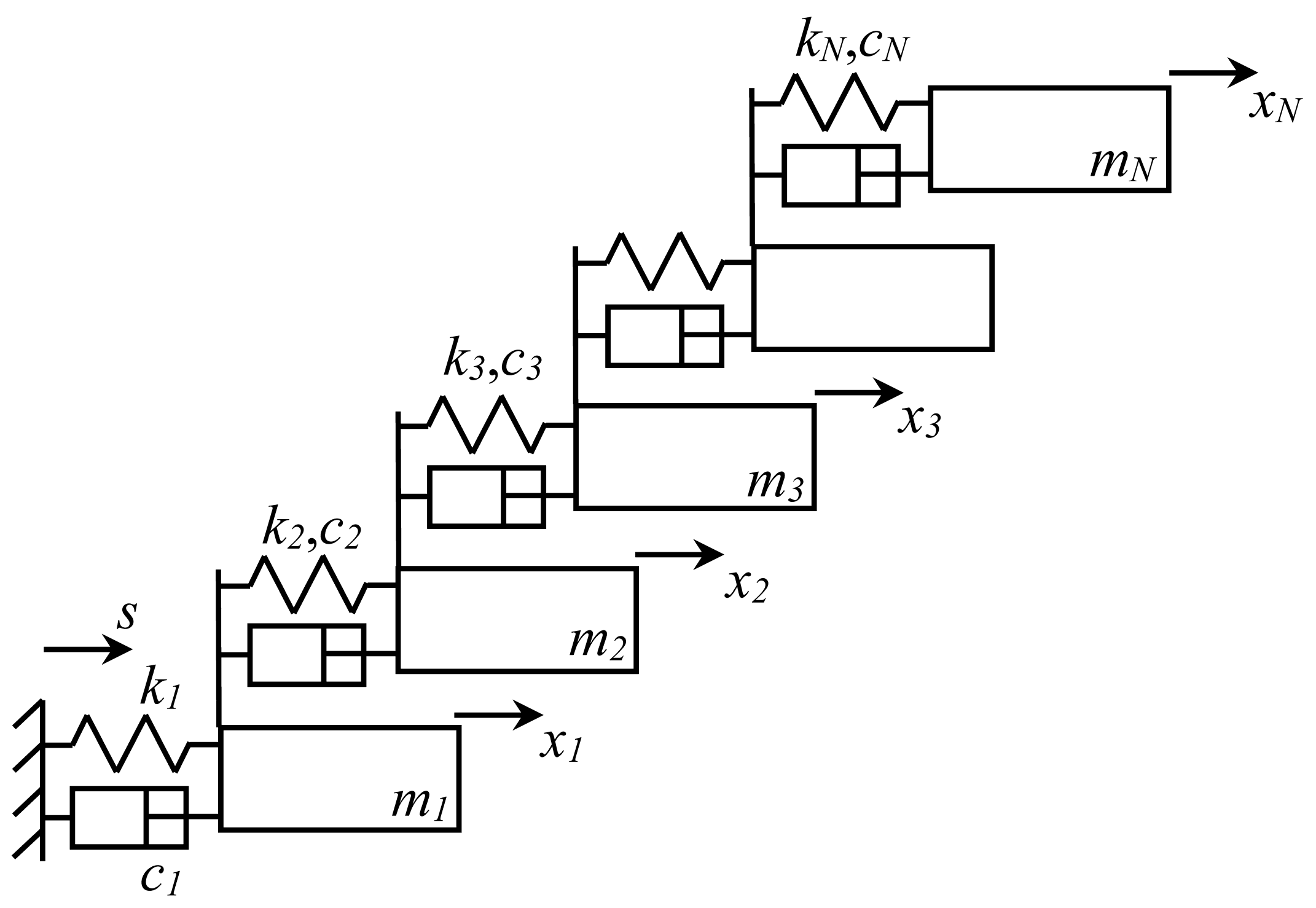

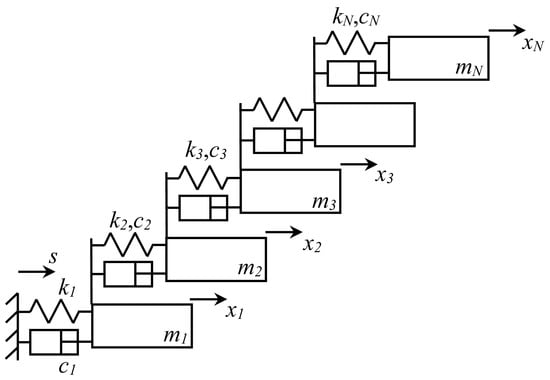

In order to observe and verify actual seismic resonance, a MDOF linear-elastic structural model such as the one shown in Figure 1 will be employed. An important reason to not consider at this point inelastic behavior is that resonance in nonlinear systems is very complex and not as evident and definitive as in elastic systems; in fact, even if we deal with a single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) nonlinear system, such as the “simple” Duffing oscillator, several resonances can be considered therein: main, subharmonic, supraharmonic and ultrasubharmonic, and the associated jump phenomenon in the frequency response function [18]. Regarding damping, viscous damping has been added to the model as all structures are naturally damped but since the pure or mathematical resonance concept originates in undamped SDOF systems, low levels of damping will be considered (see Section 3) because the main interest is in experiencing or observing resonance as neatly and purely as possible. In the practical seismic case, as the input is inherently highly nonstationary or most earthquakes last a fraction of a minute, there should not be any concerns about the possibility that light damping could result in unbounded motion, which is a common concern in the original resonance concept which is associated with not only steady-state input but also of the harmonic type.

Figure 1.

Multi-degree-of-freedom structure.

The equations of motion of this system under earthquakes are fairly common or do not require derivation:

therein, mi, ci and ki are the mass, damping coefficient and stiffness of each level, xi is the displacement of each floor relative to the ground, and s is the ground displacement which is always absolute.

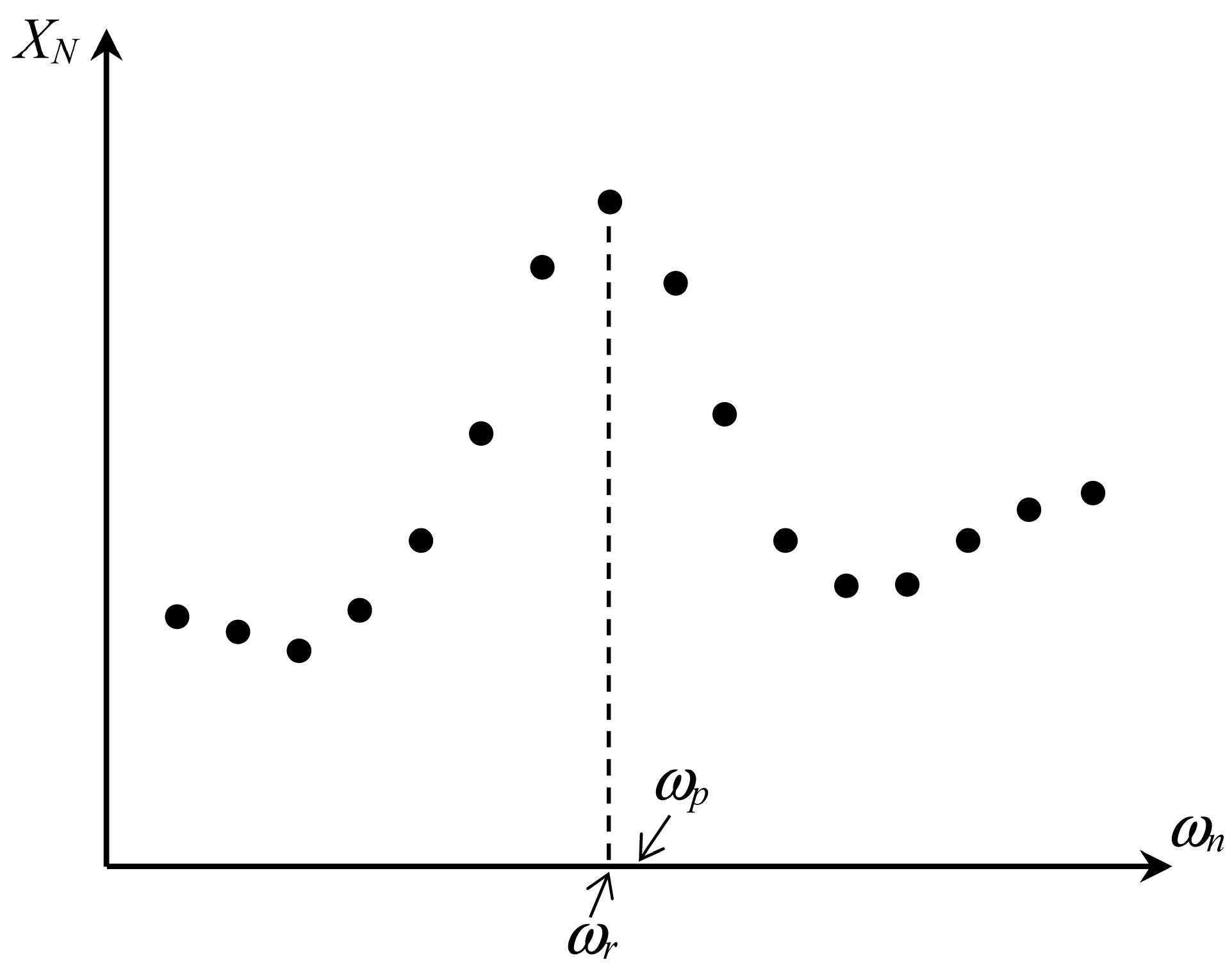

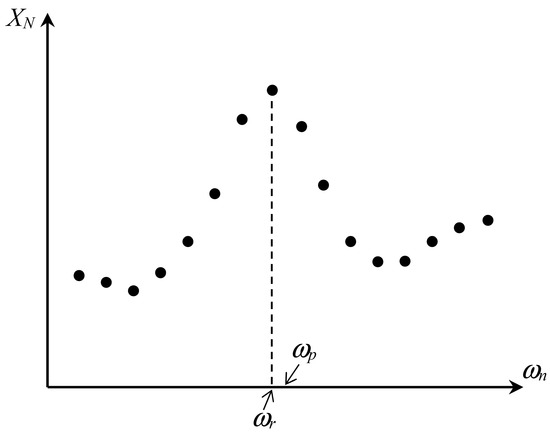

Next, the structural system resonant behavior will be studied under an important set of real and strong earthquakes. The significance of the set lies in that the moment magnitudes are larger than 6.5, that the records are near-field, and in that it is an international set, which is shown in Table 1. As explained in the Introduction, resonance is analyzed focusing on the global deformation or the last-story displacement relative to ground, xN, as this is a single variable most related to mechanical failure, which is the main consequence or concern under resonance, either in machinery or structures. The time-history peak value of this overall drift, XN, will be plotted against the fundamental natural frequency of the structure, for each earthquake. This will result in a resonant graph similar to Figure 2, which is illustrative, if indeed (1) seismic structural resonance, centered at ωr, is a fact or a real possibility in near-field instances, and if (2) near-field seismic records do have a single predominant frequency, which is a premise of this research based on recent results [15]. In fact, the plot can also exhibit that predominant frequency of ground motion, ωp, as obtained in that recent work, to highlight the match between ωp and the encountered or observed resonant frequency ωr. This coincidence is or would be, of course, one main result of this research as it will corroborate the previous results [15]. Again, the figure in this Method section is illustrative; ωp could be lower than ωr, and even in the perfect case (which in nature there are some, as shown in Section 3), ωr can be equal to ωp.

Table 1.

Selected set of seismic events and respective records.

Figure 2.

Global peak displacement against natural frequency to observe resonance (illustration).

In mathematical, rather than visual, terms that frequency match will be emphasized, in Section 3, by a relative difference whose expression is

which is expected to be low. In fact, if the relative differences for the set of events are below 10% (or 0.1), this can be considered a confirmation that near-field earthquakes do have a period that predominates [15] which has been elusive to demonstrate before by insisting in obtaining dominant periods through the usual ARS or Fourier analysis of the input acceleration. It is stressed that this confirmation will be based on analyzing, and indeed experiencing (witnessing) resonance, in an N-story building; it is noted also that the 10% is established arbitrarily although it is based on the fact that an earthquake is not at all the ideal harmonic excitation, where relative differences of less than 5% are expected.

Now, the recently published predominant frequency results [15] may require some explanation because this study is based on those. In that previous work, clear predominant frequencies for strong seismic ground motion in the near field were established, with a novel and different idea, that of considering displacement response rather than the more common acceleration one. In particular, relative displacement response spectra were studied and the existence of clear and neat maximum spectral displacements was demonstrated in each of the 20 spectra analyzed; in fact, the predominant frequency is defined as the fundamental frequency at which the maximum peak displacement occurs for 5% damping. Moreover, the statistical distribution of the records set is characterized by a superior standard deviation, so that a single and general seismic predominant frequency is advanced, even though this last proposal may be debatable.

3. Results

First, the example structure is defined; it is a five-story (N = 5) building with parameters mi = 6 × 105 kg and ci = 3 × 104 Ns/m, while ki = k is the chosen parameter allowed to vary to search for or attain resonance. That story damping coefficient implies a lightly damped system as discussed in Section 2; to be more precise, the damping factor ζ = 2% (ci/2miωn) if resonance is imposed (or if the story natural frequency is equal to 0.18 Hz which is a mean predominant frequency [15]). The real near-field strong motions were defined also in Section 2, and these are the inputs here to the structural system, to obtain the resonance graphs as Figure 2. Again, these plots show the peaks of the displacement time history of the 5th floor or roof as a function of the main natural frequency of the building. The peak of this plot, in turn, is located and it defines the resonant frequency ωr, as in the illustrative plot (Figure 2). It can be said, then, that the resonance presented is the “peak of peaks”, being the plural for the time domain and the singular for the frequency domain.

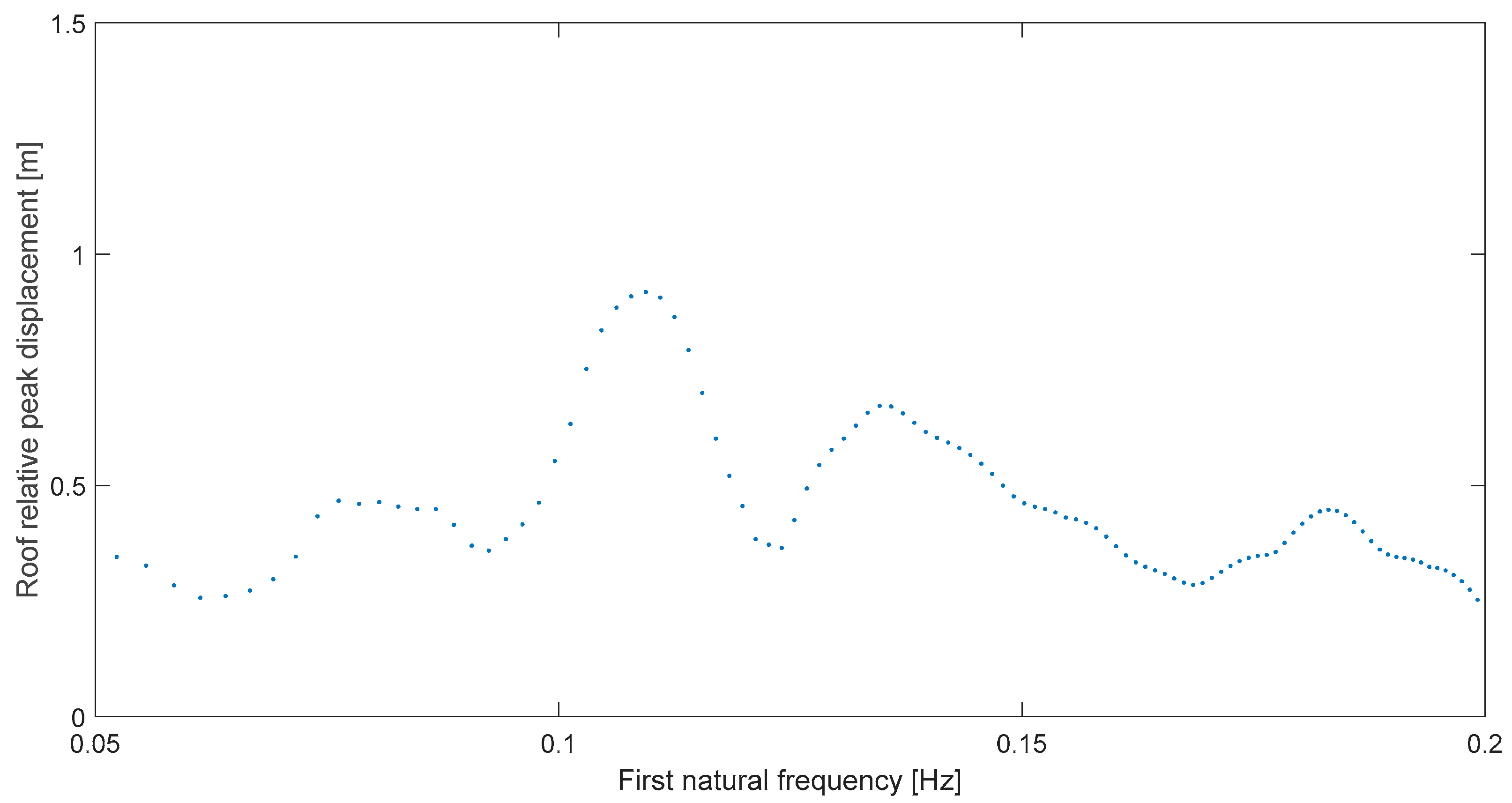

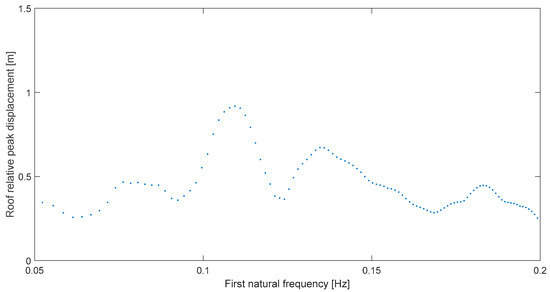

To be clear, let us consider the first case or Kern County at Taft. Its resonance plot, proposed in this paper and shown in Figure 3, exhibits clear resonant behavior in the structure when it is subjected to this seismic record. That is, the global deformation almost trebles on a narrow range (0.09–0.12 Hz) from non-resonance levels when the building’s natural frequency nears the predominant frequency of this ground motion, which has been previously obtained as ωp = 0.109 Hz [15]. As a matter of fact, in this case, there is no nearing or the frequency match is perfect because the graph maximum is exactly at ωr = 0.109 Hz, for a relative difference δ = 0. It is important to note that the order is chronological; that is, we are not presenting first, on purpose, the neatest result regarding difference δ.

Figure 3.

Global peak deformation for Kern C at Taft (111°).

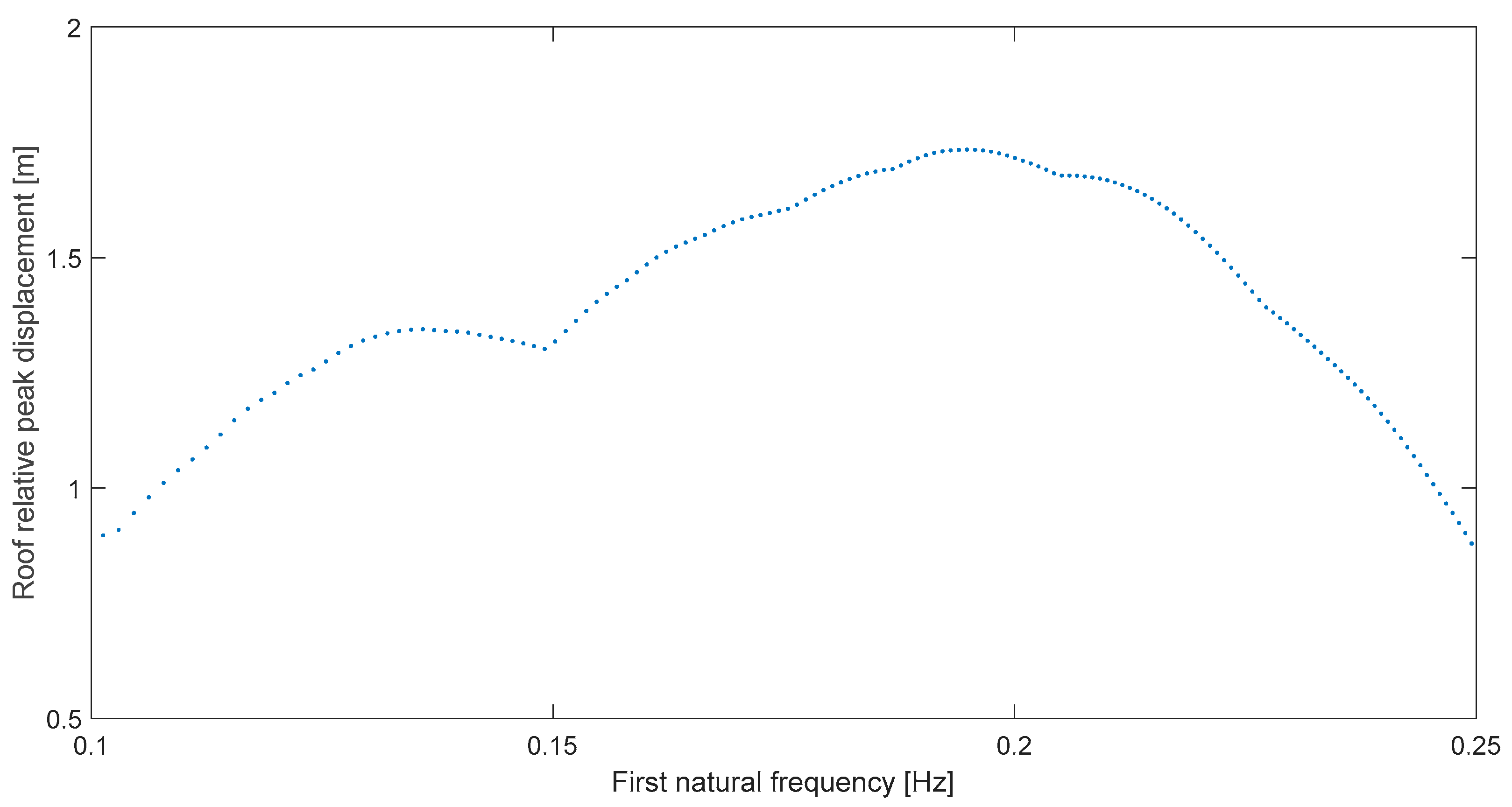

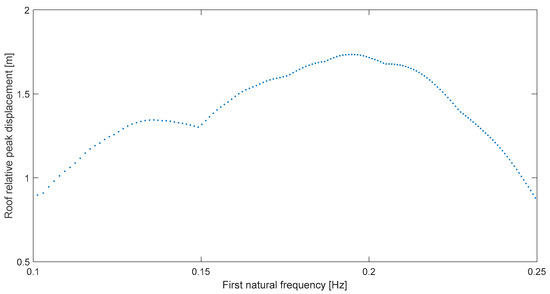

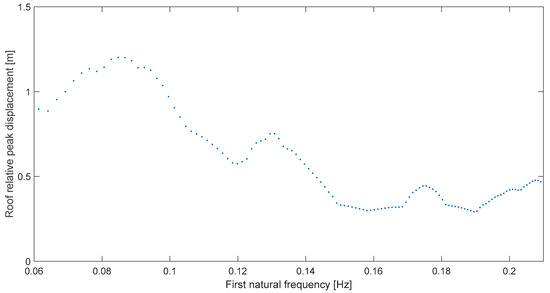

Let us consider the next case, San Fernando at Pacoima Dam, whose resonance graph is Figure 4. In this second case, the resonant peak is not as narrow or clear as in Kern C at Taft, but the amplification is also notable in the deformation response as it basically doubles near 0.19 Hz from levels at either 0.25 or 0.1 Hz. Now, the relative difference result is not as perfect as in the first case because the predominant frequency for this record is ωp = 0.17 Hz [15] and ωr = 0.195 which implies a difference δ = 14.7%. It is important to note, regarding bandwidth, that all the spectra have a 0.15 Hz range, this for resonance narrowbandness comparison purposes; moreover, note that a 0.15 Hz width is already a narrow band, so when it is said that in this second example the resonance is not as narrow as in the first case, we are solely comparing.

Figure 4.

Global peak deformation for San Fernando at Pacoima Dam (164°).

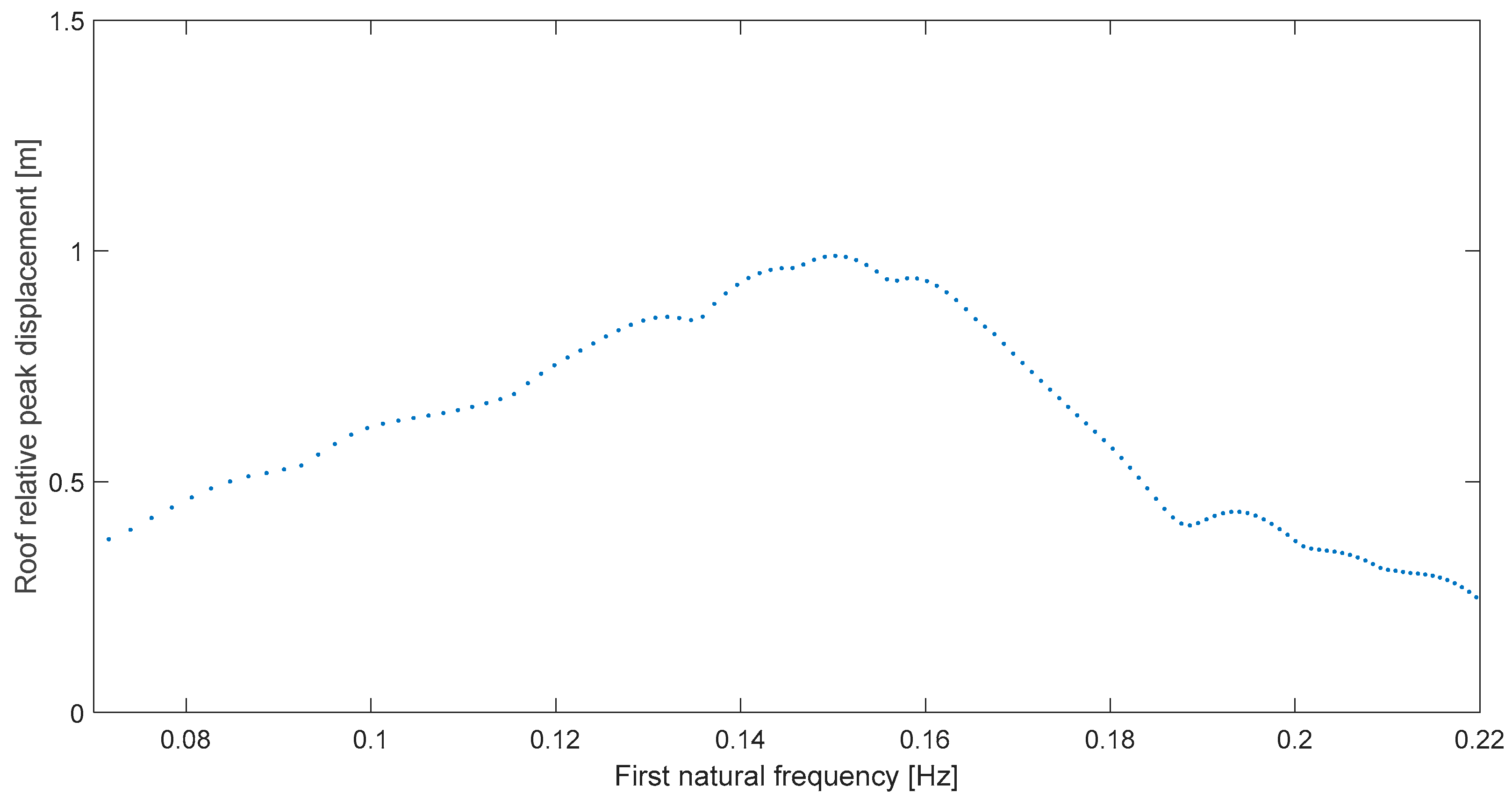

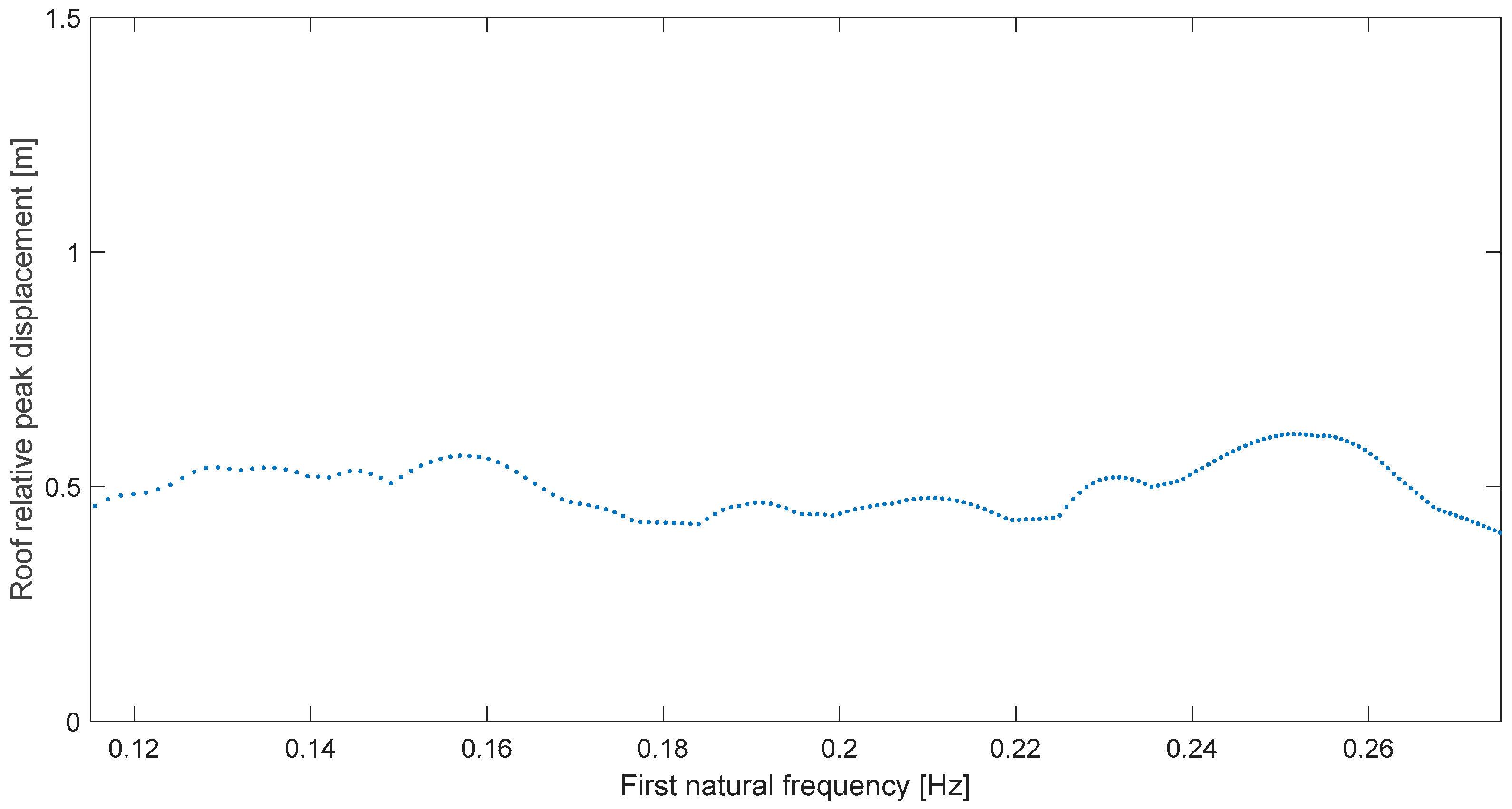

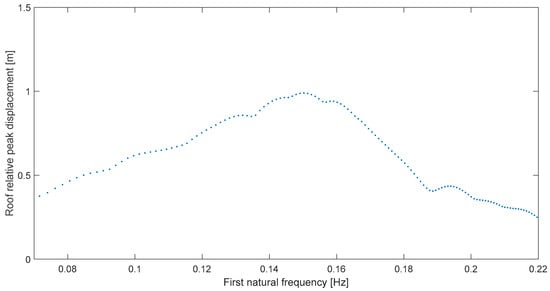

Similarly, for Imperial Valley at Calexico (Figure 5) resonance also appears clearly as the roof displacement more than doubles from ~0.4 m to 0.99 m at 0.15 Hz, and the difference between ωp and ωr is 14.5%. The exact resonant frequencies ωr obtained in this work, the retrieved predominant frequencies ωp [15] and the relative differences are shown in Table 2 for all cases. In addition, it is noted that all spectra have the same ordinate range: 1.5 m, again, for a correct comparison among the real seismic resonances presented.

Figure 5.

Global peak deformation for Imperial Valley at Calexico (315°).

Table 2.

Resonant and predominant frequencies, and relative difference thereof, plus bandwidth and transmissibility.

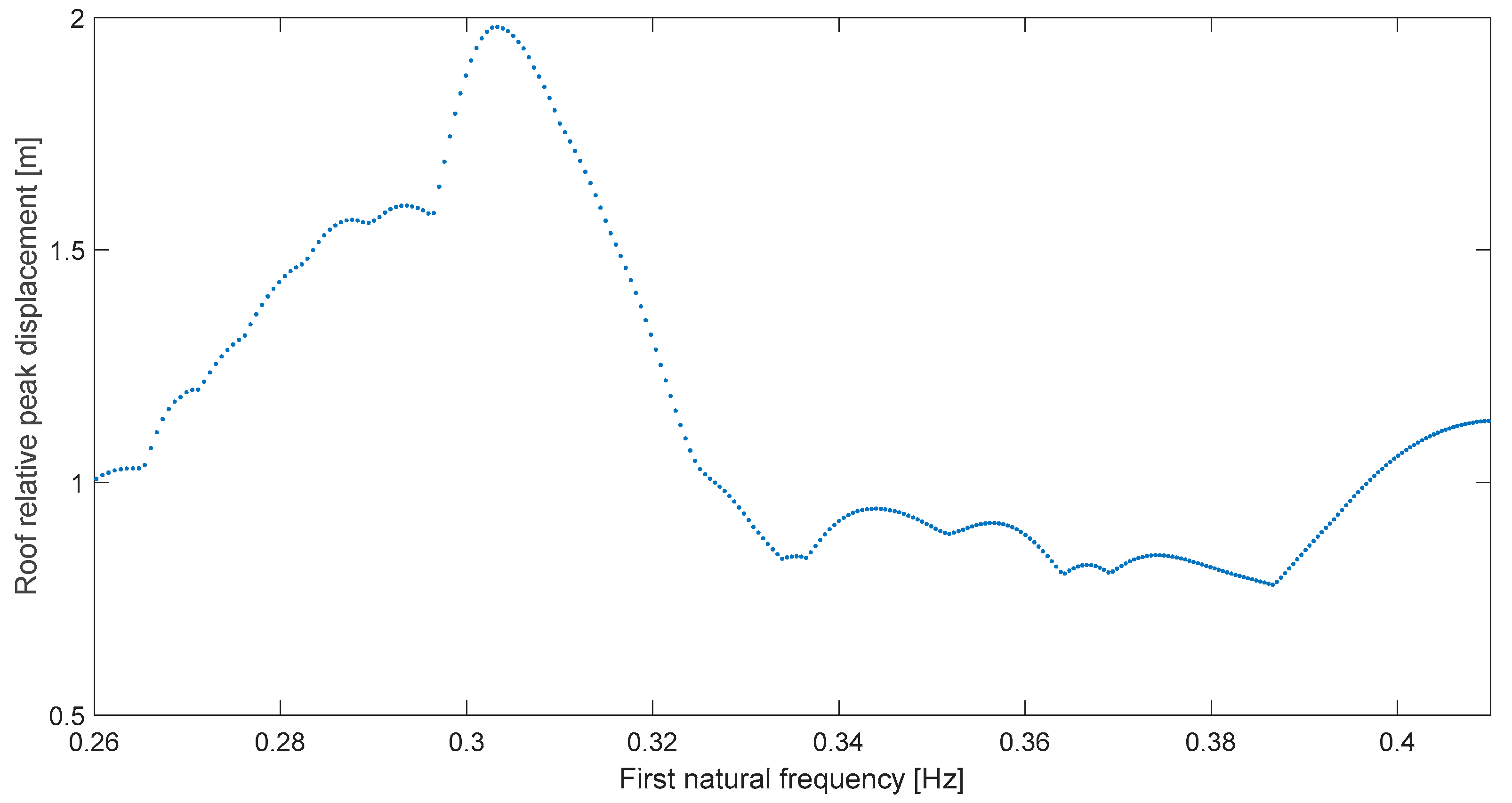

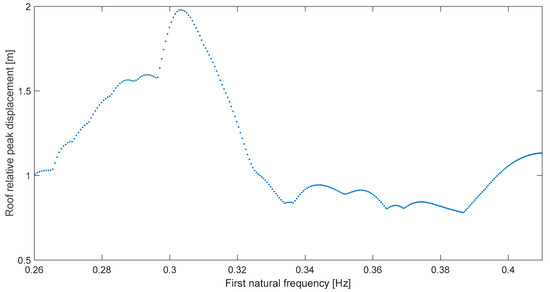

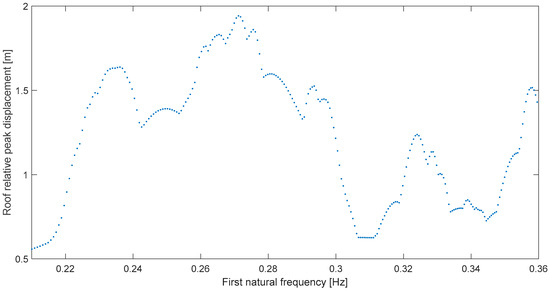

Regarding clarity of resonance, the next case (Imperial W, Figure 6) is worth highlighting as the amplification is clear at ~0.3 Hz; in fact, the response more than doubles from the levels at slightly higher frequencies (0.33–0.39 Hz, which is a non-resonance range). Here, it is established that clarity of resonance is composed or defined by both level of amplification and narrowbandness. To measure narrowbandness the classical bandwidth Δω can be computed, and to measure amplification the relative transmissibility Tr can be calculated which is equal to the magnification factor at resonance (for a SDOF system) [19]. These are shown also in Table 2 where it can be confirmed that Imperial Wildlife resonance clarity is superior; it is noted, nevertheless, that earthquake response spectra are complex and cannot be simplified as a common frequency response, so, e.g., the bandwidth concept cannot be applied as simply in all cases. Finally, in this case, there is a strong frequency match because difference δ is just 5.2%.

Figure 6.

Global peak deformation for Superstition Hills at Imperial Wildlife (0°).

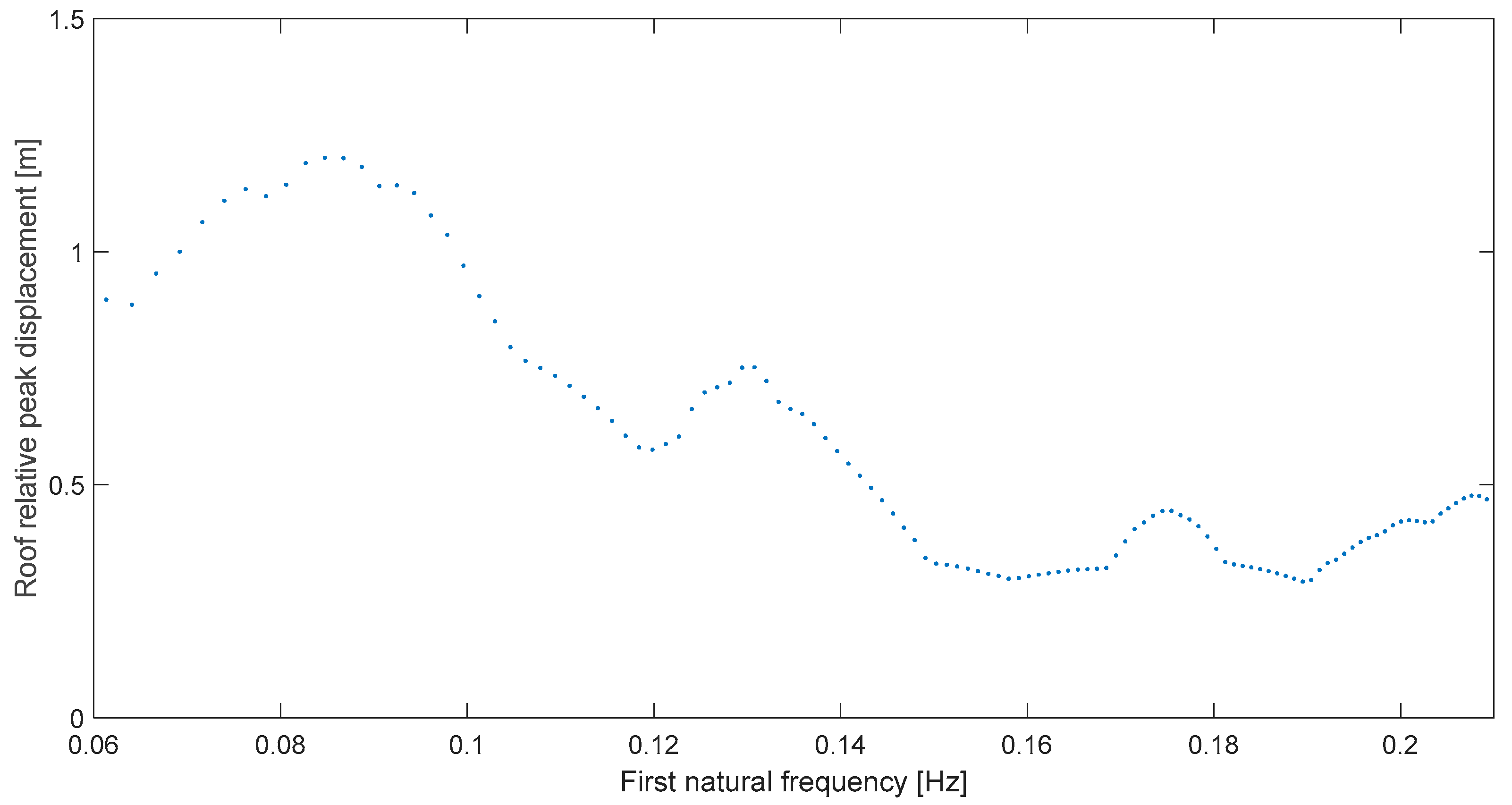

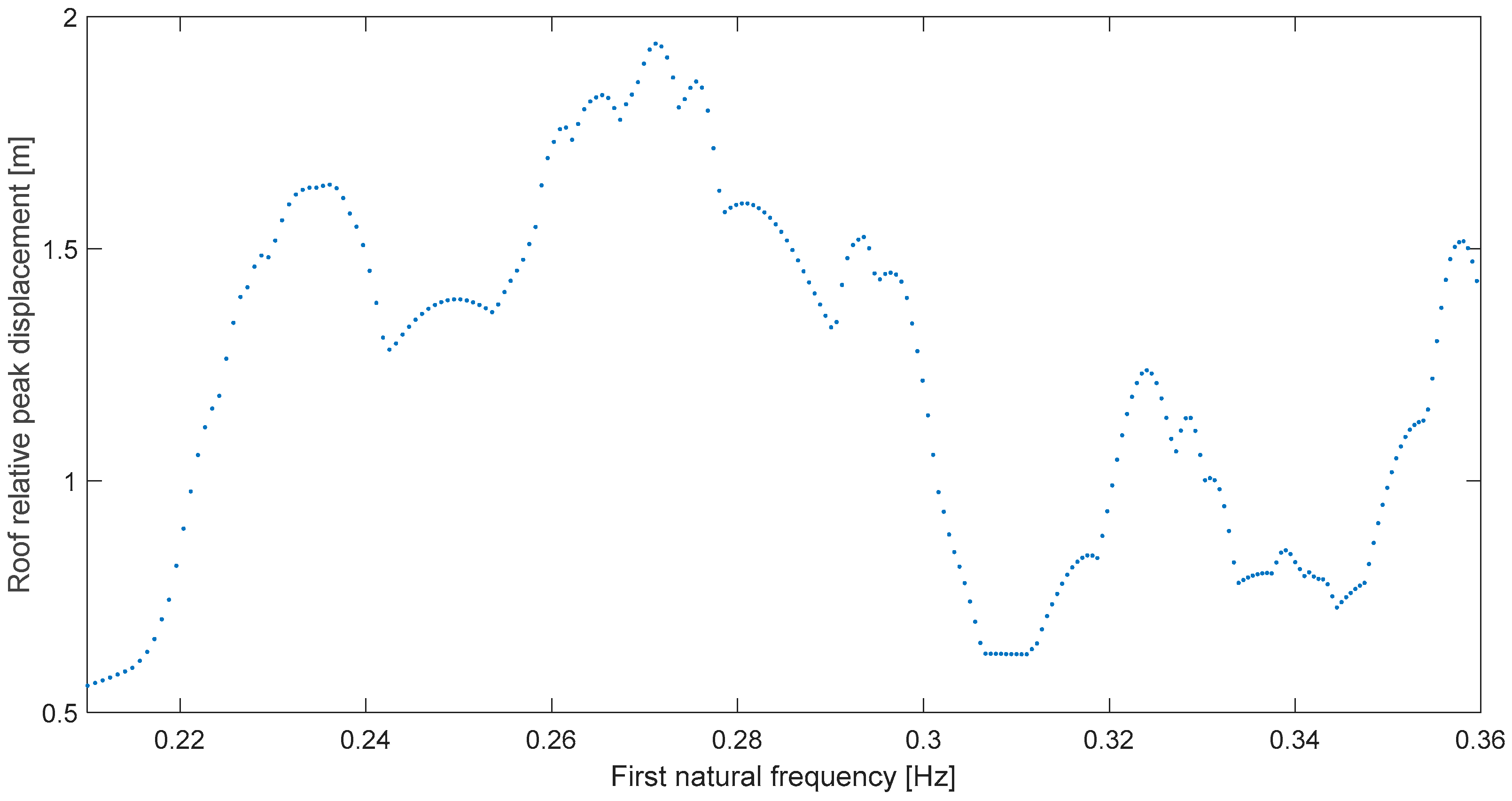

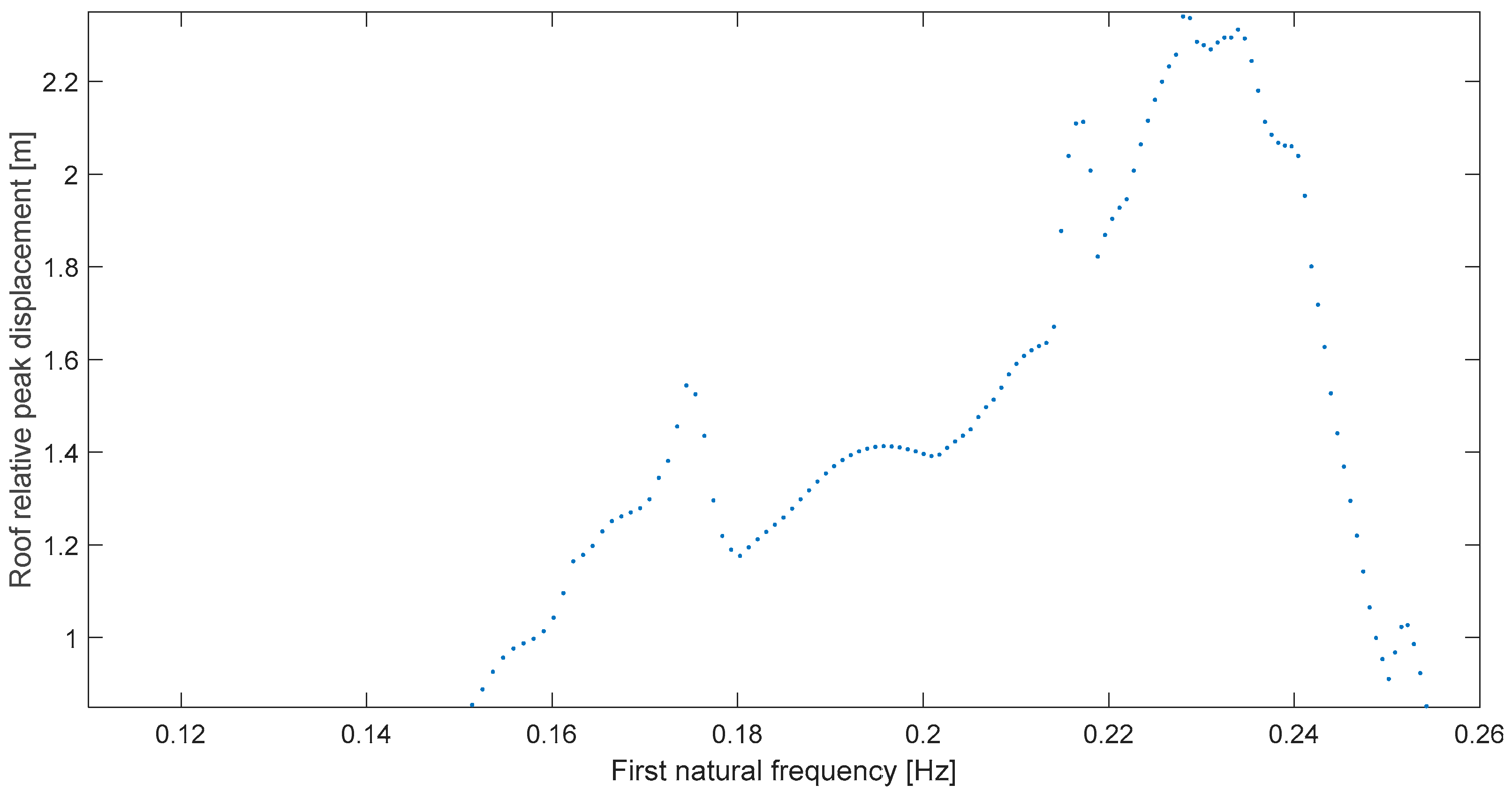

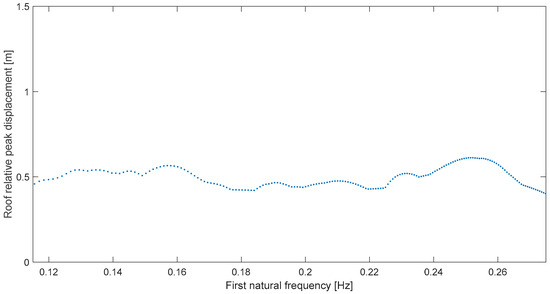

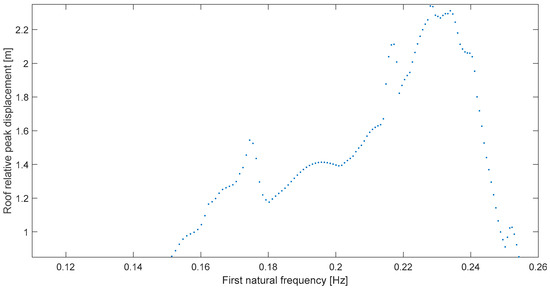

The rest of the roof or global deformation response spectra are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10. Solely for the Norcia case (Figure 9) the amplification is not very clear, at ~0.16 Hz; this is corroborated by its transmissibility (Table 2) which is the lowest; also, the bandwidth concept cannot be applied in this case. Moreover, although δ is a decent 10.3% (Table 2), in this particular case there is another or main resonance at 0.25 Hz which makes it a distinct case because in the other ones there is a predominant resonance at a frequency very similar to the earthquake predominant frequency, obtained by employing the displacement response spectrum [15] which is a single-degree-of-freedom concept. Now, Kaikoura at Te Mara (Figure 10) must be highlighted because at resonance, ωr = 0.228 Hz, the response trebles from levels at either 0.15 Hz or 0.25 Hz, which means a very clear, and potentially harmful, amplification. More remarkably, the predominant frequency, ωp, is exactly 0.228 Hz (Table 2) for a perfect frequency match, or δ = 0 in this case.

Figure 7.

Global peak deformation for Chi Chi at Taichung 78 (90°).

Figure 8.

Global peak deformation for Maule at Constitución (T).

Figure 9.

Global peak deformation for Norcia at Norcia (E).

Figure 10.

Global peak deformation for Kaikoura at Te Mara (332°).

4. Discussion

This research had two objectives: to observe seismic structural resonance in MDOF building models, and to confirm recent seismic predominant frequency results. The two are related because to experience or technically witness structural (mechanical) resonance, a predominant frequency is required, a concept that was elusive in earthquake engineering and seismology until recently, as explained in the paper.

The analysis considering an important set of international earthquakes (MW > 6.5) demonstrated clear resonant behavior in the five-story example building studied when its fundamental natural frequency is varied or tuned with the input predominant frequency. In fact, for three records (Taft, Imperial W and Te Mara) the amplification is, in general, 3-fold; moreover, the observed resonance is positively narrowband for these three cases, which is equivalent as saying that the resonance plots exhibit an evident amplification concentrated in a limited and well-defined bandwidth. To be more precise, in these three cases the bandwidth is only 0.02 Hz, which is the lowest or best in the set, and the transmissibility is above 10 (16.9 for Imperial W which is the highest). The other results or graphs also show clear resonances, except for Norcia (Figure 9) which was thoroughly discussed. Again, the literature review has demonstrated that there are no works in which resonance is observed this clearly and where a concrete match of input predominant frequency and structural natural frequency is studied concurrently; the reason for this literature fact (again) is that there had not been a definitive seismic predominant period [13].

As importantly, the other main result is also very positive; indeed, the overall (mean value) relative difference between ωp and ωr is only 7.56%; that is, the structural resonance, as hypothesized in the Abstract, occurs near the input signal predominant frequency as defined quite recently [15]. In this regard, it should be recalled, from Section 2 now, that a 10% difference was expected or was a target; we have obtained a positive overall result (8 major seisms) below 8% which, in addition, confirms that earthquakes do have a predominant frequency, if the analysis is based on displacement rather than the common acceleration [15]. As an interesting or additional result from these strong and near-fault events, it is noted that—amazingly—there are two 15% δ results, two 10% ones, two 5% ones and finally, and more remarkably, two zero difference results (Table 2) which mean perfect frequency match. These perfect results, ωp = ωr, are for Taft and Te Mara, which are also cases where the two-way measured resonance clarity, presented here, was notable. Regarding perfection and the Taft result, it is also added that the resonance shape (Figure 3) is very smooth, so much so that it can be thought of as resembling a mathematical or closed-form function; in fact, in another recent work it is demonstrated that displacement response spectrum smooth shapes are harmonic [20].

Now, it can be argued that this linear structure analysis limits the physical realism of the results, as in real buildings nonlinear analysis can be necessary, especially in earthquake engineering. However, apart from the facts that there is no single resonance in inelastic systems, and there is the jump phenomenon (both complexities discussed in Section 2), several authors have written that “resonance is not possible for mass-nonlinear spring systems” [21], and that “the natural period is not defined for inelastic systems” [22]. In other words, vibrations resonance (which is the original and actual one) is hard or impossible to analyze in its purely mathematical or original terms for nonlinear structures. Therefore, since a literature review on seismic structural resonance indicates that there are no papers in which the original resonance concept is studied and, more importantly, observed clearly, we consider that a very first work on the subject should be logically for linear systems, where resonance can be studied in its original (vibrations) or mathematical terms, which absolutely imply an input/system frequency match, which in turn is only possible after a seismic predominant frequency is defined, and if there is an absolute and unequivocal structural frequency. Of course, future work must be to investigate the problem in nonlinear structures; this is discussed in Section 5.

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrated clear resonance in the structure analyzed when its fundamental frequency is varied and tuned with the seismic predominant frequency. In fact, for most cases the resonance plots exhibit an evident and measured amplification concentrated in a limited and well-defined bandwidth. The second important result is very positive as well; in fact, the overall spectral difference δ is below 8% which confirms that (1) structural resonance does occur near the predominant frequency established recently [15], and (2) earthquakes do have a predominant frequency.

Structural and earthquake engineers can use these results in the clear sense of not designing buildings with natural frequencies close to the predominant frequencies established; this technical recommendation could not be written this clearly before because there had not been definitive seismic predominant periods [13] without which actual resonance is not possible. But there are now novel predominant frequencies [15] and this work confirms that these are not only dominant but also resonant. That is, the contribution to engineering is a double confirmation: (1) that the predominant frequencies indeed produce response amplification in more complex structures than the SDOF system, and (2) that these frequencies cause a clear resonance based not only on the transmissibility results but also on the bandwidth ones.

A limitation of this work is the small number or seismic records, even though the set analyzed is important or was selected considering internationality, magnitudes greater than 6.5 (MW) and distance (near-source signals only). Future work should be directed at enlarging the earthquakes set. Analysis of inelastic structures should also be the subject of future work; that is, a first work on the matter had to be theoretical or mathematical, as discussed in Section 4, but of course advanced computer simulations can be used to study more real nonlinear and 3-dimesional building models [23].

Funding

UPC funding is mainly for open-access publishing; thus, there is no particular grant numbers but a general UPC program: EXPOST-2025.

Data Availability Statement

All data necessary for this research is publicly available in third-party seismic databases, e.g., at strongmotioncenter.org (CESMD).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elanashai, A.S.; Di Sarno, L. Fundamentals of Earthquake Engineering; Wiley: West Sussex, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.G.; Fischer, T.P. Quasi-resonance effects observed in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, and others. Shock. Vib. 1998, 5, 5153–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcan, S.S.; Ipek, M. Long distance effects of the 28 March 1970 Gediz Turkey Earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1973, 1, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takewaki, I. Remarkable response amplification of building frames due to resonance with the surface ground. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 1998, 17, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullu, H.; Pala, M. On the resonance effect by dynamic soil-structure interaction: A revelation study. Nat. Hazards 2014, 72, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, D.; Markusic, S.; Strelec, S.; Gasdek, M. HVRS analysis of seismic site effects and soil-structure resonance in Varazdin city (North Croatia). Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 92, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresca, R.; Nardone, L.; Gizzi, F.; Potenza, M. Ambient noise HVSR measurements in the Avellino historical centre and surrounding area (southern Italy). Correlation with surface geology and damage caused by the 1980 Irpinia-Basilicata earthquake. Measurement 2018, 130, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon, L.; Pujades, L.; Macau, A.; Figueras, S. Increased seismic hazard in Barcelona (Spain) due to soil-building resonance effects. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 117, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celebi, M. Revelations from a single strong-motion record retrieved during the 27 June 1998 Adana (Turkey) earthquake. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2000, 20, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A.; Preciado, A.; Bandy, W.; Salazar, E.; Jaimes, M.; Alcantara, L. The Tesistan, Mexico earthquake (Mw 4.9) of 11 May 2016: Seismic-tectonic environment and resonance vulnerability on buildings. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2019, 18, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusay, R.; Aydan, O.; Erken, A.; Tuncay, E.; Kumsar, H.; Kaya, Z. An overview of geotechnical aspects of the Cay-Eber (Turkey) earthquake. Eng. Geol. 2004, 73, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, R.; Chae, Y. Adaptive base isolation system to achieve structural resiliency under both short- and long-period earthquake ground motions. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2019, 30, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathje, E.M.; Abrahamson, N.A.; Bray, J.D. Simplified frequency content estimates of earthquake ground motions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1998, 124, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tong, G. An investigation of characteristic periods of seismic ground motions. J. Earthq. Eng. 2009, 13, 540–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.A. Predominant frequency in near-field strong ground motion by analysis of displacement response spectra. Buildings 2024, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.A. Further seismic displacement PSDF results. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2010, 34, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.A. Narrowbandness of seismic ground displacement on a broader area of the lithosphere and importance on base motion in isolated structures. J. Vibroeng. 2021, 23, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayfeh, A.H.; Mook, D.T. Nonlinear Oscillations; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, C.A. Validation of a one predominant frequency presence in seismic ground displacement by means of deformation response spectra. Buildings 2023, 13, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.A. Harmonic forms in displacement response spectra and a novel definition of earthquake duration in pulse-type strong motion. J. Vib. Control 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirovitch, L. Elements of Vibration Analysis; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, A.K. Dynamics of Structures; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, A.; Sahin, E.K.; Demir, S. Advanced tree-based machine learning methods for predicting the seismic response of regular and irregular RC frames. Structures 2024, 64, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).