Abstract

Inner courtyards have been traditionally used as passive strategy in vernacular buildings in desert climates. This paper presents a study conducted to investigate indoor and outdoor thermal comfort of two vernacular buildings in the hot arid climate of Upper Egypt and proposes an improved solution for courtyards to achieve sustainable development of current vernacular houses and apply the same in the arid climate zone of Egypt. The thermal comfort of vernacular building spaces was evaluated based on using field measurements during the hot season and improvement for courtyards based on ENVI-met V5.6.1 simulation model using three scenarios. Two vernacular buildings (Hassan Fathy and Nubian house) were selected to represent the traditional buildings south of Egypt. The study found that using adobe bricks with high thermal mass in vernacular buildings maintained lower indoor temperature with a range of 2.7 °C to 6.7 °C compared to outdoor temperature; this is considered effective thermal insulation. Meanwhile under extreme hot conditions, courtyard temperature inside the vernacular house was 0.3 K higher than the outdoor. This is not sufficient to maintain indoor thermal comfort without integrating passive solutions inside courtyards. In addition, applying the hybrid solution with big dense trees in the courtyards achieved a significant reduction in PET ranging from 4.2 °C and 5.7 °C; shading the widest area of courtyards and allowing for family activities. The study provided techniques and methodology for the middle courtyard of vernacular buildings, demonstrating how improvement achieves thermal comfort and sustainable development required in the 21st century in Upper Egypt, and can be applied to other vernacular houses in different desert cities in southern Egypt.

1. Introduction

There are several studies focused on assessing the improvement of indoor thermal comfort in vernacular buildings besides its efficiency in saving energy consumption. For example, Heidari and Davtalab [1] have evaluated the thermal effect of KharKhona on the indoor thermal comfort of a room in a vernacular house in Sistan region, Iran. They reported a reduction in PET, the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV), and standard effective temperature (SET): 7.69 °C, 1.39, and 3.98 °C, respectively. Moreover, Zou et al. [2] assessed the indoor overheating degree and indoor overheating hours to analyze the thermal environment in vernacular buildings in China. The results showed that the indoor overheating degree improved from 0.7 °C to 1.5 °C inside the case study, and indoor overheating hours were enhanced by a ratio of 40–70%. Fernandes et al. [3] have evaluated the thermal performance of a rammed earth building located in southern Portugal. It was found that thermal comfort had improved to grade “Comfortable” by utilizing shading and natural ventilation devices. Chang et al. [4] studied the impact of building spaces on the thermal environment in vernacular buildings in China, by conducting an occupancy survey. The results indicated that the acceptable air temperature ranged from 23.3 °C to 24.9 °C in summer, and from 18.3 °C to 23.4 °C in winter, and that is available in vernacular buildings compared to modern buildings in the same location. Nevertheless, He et al. [5] assessed the influence of two climate-responsive strategies of vernacular buildings in China on energy consumption by using DesignBuilder software v6.1.8.021. The two strategies employed were multilayer spaces and integrated building envelopes, and their energy-saving rate was 23.7% and 38.3%, respectively. Bayoumi [6] analyzed the Nubian vernacular system in Nubian houses in Aswan, Egypt for applying this system in contemporary buildings to improve passive cooling and thermal comfort, as well as decreasing energy consumption. Also, Du et al. [7] have conducted field measurements of vernacular building microclimate and compared the measurements with dynamic thermal and CFD simulation results. Hence, the simulations could predict the building microclimate successfully. Furthermore, a set of studies has assessed the effect of vernacular buildings on outdoor thermal comfort. For example, Diz-Mellado et al. [8] have assessed the effect of urban courtyards in vernacular centers of a Mediterranean city. It was found that the number of comfort hours (physiological equivalent temperature index) increased by 27%. In contrast, global cooling demand was reduced by 31% using shading devices and courtyards. Davtalab and Heidari [9] have investigated the impact of Kharkhona (an architectural element) on outdoor thermal comfort in the vernacular region of Iran. The results revealed that the physiological equivalent temperature (PET) index was reduced by 9.34 °C. Thus, Kharkhona can be used as a natural ventilation strategy and be more efficient than the vegetation strategy. Xu et al. [10] have studied the factors that influence thermal comfort in vernacular dwellings in Southwest China. It was found that the narrow design of alleys in vernacular dwellings played a main role in reducing the indoor heat gain by 58%. Consequently, it was recommended to integrate the vernacular urban design concepts with modern urban fabric. Also, most studies agree that vernacular buildings in hot regions of the Middle East achieve good thermal comfort using passive design [11,12,13,14]. Abdulkareem [12] shows that courtyard houses create cooler microclimates than surrounding streets, especially in late afternoon and evening. Haseh et al. [13] found that greenery covering more than 50% of the courtyard can improve thermal comfort in hot dry Isfahan. Later studies on Fathy’s Nubian house used architecture design and elements for achieve thermal comfort. A review on vernacular architecture and Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) notes vernacular elements tend to improve satisfaction with thermal comfort and overall IEQ [14].

On the other hand, several scientific studies have compared the indoor thermal performance in vernacular and modern buildings, or different types of vernacular buildings. For instance, Mangeli et al. [15] have proposed a framework to compare vernacular buildings’ parameters (rock-cut houses) with contemporary buildings’ parameters in Iran and estimated the energy consumption. The result of the PMV index in rock-cut houses and modern houses were 0.61 and 0.77, respectively. Further, energy consumption was zero in rock-cut houses against 7.7 KW daily in modern houses. Also, Widera [16] evaluated the thermal environment of vernacular dwellings in western sub-Saharan Africa and compared its results with modern houses in the same location. The results indicated that the user thermal comfort was accepted by 70% in vernacular dwellings (air temperature 26–30 °C), in contrast to 20% in modern houses. Additionally, the concentrations of CO2 increased to 1800–1900 ppm because of the lack of adequate ventilation. Chkeir et al. [17] analyzed thermal comfort parameters and conducted an occupancy survey in two traditional and contemporary houses in Lebanon. The results revealed that the thermal performance in a traditional house is better than in a contemporary one and, consequently, in energy consumption because of using courtyards, natural ventilation, and special architectural elements (narrow and tall windows, porous and light-colored materials, three arch motifs). Also, Toe and Kubota [18] have compared the vernacular cooling techniques in two traditional houses in Malaysia and two other traditional shophouses in China. It was found that, in all four cases, the courtyards assisted in reducing the indoor air temperature in rooms adjacent to the courtyards by 5 °C. Chandel et al. [19] have reviewed the vernacular architectural features that can be adapted in contemporary buildings to keep pace with current lifestyles for improving indoor thermal comfort conditions and energy efficiency. The results indicated that the critical features are built mass design, building and roof materials, orientation, construction techniques, space planning, openings, sunspace provision, and earth as a floor with thermal insulation property. There are many studies on this approach, such as Salameh et al. [20] and Hassan et al. [21].

Moreover, some studies have addressed improvement solutions for vernacular buildings. For example, Zheng et al. [22] have proposed optimization strategies, such as adopting insulating glass windows and increasing the insulation materials of the envelope, to improve indoor thermal comfort in vernacular dwellings in China. The results of the simulation process using DesignBuilder indicated an improvement in thermal environment grade of 4.7%. Also, Abdel Kader and Hassan [23] have improved the model of modern Nubian houses in Aswan, Egypt, to enhance indoor thermal performance using Autodesk Simulation CFD software 2024. So, the results revealed that the air temperature decreased by 2.8 K and the inner ventilation was enhanced to reach 0.9 m/s. Evola et al. [24] have proposed modern envelope solutions for a vernacular house located in Catania, Italy to improve indoor thermal comfort. The modern envelope solutions were (a) a double leaf of bricks, and (b) installing insulation material on the inner and outer walls. It was found that the envelope of the double leaf of bricks decreased the inner air temperature by 1 °C. Conversely, the insulation material caused overheating in the inner spaces.

According to the vernacular buildings analyses in the previous studies, despite the importance of indoor passive strategies for enhancing thermal comfort, the courtyards of these buildings often face environmental challenges such as overheating in summer, limited shading in some spaces, etc. Therefore, this study will investigate the indoor and outdoor thermal comfort of two vernacular houses in Aswan City, Egypt. Based on the field studies and a questionnaire, the vernacular houses’ occupants report that courtyards are considered the main place to practice the most important daily family activities in addition to being a source of indoor spaces’ ventilation. Furthermore, some studies have investigated the outdoor thermal comfort in the vernacular buildings and proposed new improvement solutions for their courtyards. As observed, there is a problem with high air temperature and outdoor discomfort inside the courtyard, which causes heat stress for the residents. Thus, there is a necessity to propose passive solutions for the courtyards in the vernacular houses, such as shading and vegetation, besides the indoor passive strategies (thick walls, vaults, and domes). Consequently, the air temperature and outdoor thermal comfort will be improved to allow family activities to be performed comfortably during the day and the night. Hence, the main objective of this study is to analyze the indoor and outdoor thermal comfort of two vernacular buildings in the hot arid climate of Upper Egypt. In addition, the thermal influence of a set of improvement solutions on the thermal comfort of vernacular houses’ courtyards will be investigated. The novelty of this study lies in its integrated assessment of both indoor and outdoor thermal comfort in vernacular houses, an area rarely explored, combined with the development and simulation of context-specific passive courtyard enhancement strategies for hot arid regions.

2. Case Study Location and Description

2.1. Hassan Fathy House, New Gourna, Luxor

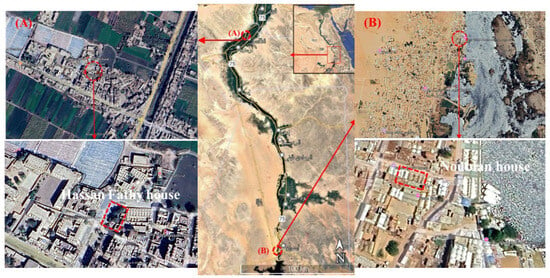

New Gourna, a village located near Luxor on the west bank of the Nile River, represents a practical case of community development utilizing locally available resources and traditional techniques. In 1945, the Egyptian government entrusted Hassan Fathy to design New Gourna, as shown in Figure 1 [25]. Luxor, located in Egypt at a latitude of 25°7′ N and a longitude of 32°64′ E, experiences maximum temperatures ranging from 41 °C to 44 °C and minimum temperatures between 4 °C and 7 °C. New Gourna, planned by Hassan Fathy, was officially inaugurated by the Egyptian government in 1945 [26]. The project was completely constructed using traditional building techniques and materials, such as adobe-baked mud bricks. Influenced by Nubian and Gourna architectural styles, Fathy adopted mud bricks to construct enclosed courtyards and arched roofings [25]. The main characteristics of New Gourna Village include its innovative reinterpretation of historic urban and architectural environments, the appropriate use of local materials and techniques, and its noticeable sensitivity to climatic conditions [27]. Fathy adapted traditional house designs for New Gourna to address the needs of contemporary farmers. These designs focused mainly on reducing the number of exterior openings, with a central courtyard serving as the house’s “lung,” providing natural ventilation to the rooms. Fathy brought back to life the courtyard house as a culturally relevant alternative rooted in Arab traditions [25]. His design decisions were informed, and influenced, by his extensive knowledge of traditional architecture, which guided the adaptation of dwellings to the local climate. Fathy’s sustainable practices were not just about urban planning, encompassing the organization, scaling, and alignment of streets, as well as the integration of courtyards in both residential and urban designs. He avoided construction methods adopted in developed countries, as they were beyond the financial capabilities of people living in rural areas in Egypt. Instead, he looked for affordable materials and construction methods, such as mudbrick and vaulted or domed roofs. Figure 2a illustrates the architectural layout of a Hassan Fathy house, which includes:

Figure 1.

The satellite image of (A) Hassan Fathy House, New Gourna, Luxor, with (B) Nubian House, West Sohail, Aswan (Author).

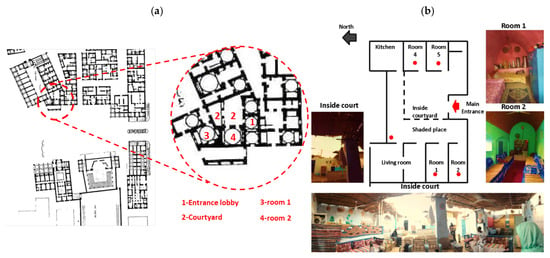

Figure 2.

Location of measurements of the two vernacular dwellings, (a) four locations inside the Hassan Fathy House, New Gourna, (b) five locations inside the Nubian house in West Suhail, Aswan (the authors).

- a.

- The Entrance Lobby: Positioned at the center of the main facade, leading directly to the courtyard.

- b.

- The courtyard: The central space where most family activities occur, connecting the various rooms of the house. It features a large, open, unroofed area.

- c.

- Bedrooms: Two rooms.

- d.

- The Kitchen: A small, often overlooked area.

- e.

- The Toilets: Located inside the house.

2.2. The Nubian House, West Sohail, Aswan

Aswan, located in Egypt at a latitude of 24°09′ N and a longitude of 32°9′ E (Figure 1), experiences maximum temperatures ranging from 42 °C to 45 °C and minimum temperatures between 7 °C and 10 °C. According to the Köppen–Geiger classification (BWh), Aswan has a hot, dry desert climate. The “B” category denotes arid or semi-arid regions characterized by high evaporation rates, while “W” signifies a desert climate. The combination “BW” indicates a dry desert climate, with the “h” for hot climate. The average annual temperature in Aswan is approximately 18 °C [28].

The Nubian houses in Aswan were constructed using mud bricks, which remain one of the most significant examples of indigenous building materials. These homes, built by the Nubians, demonstrate eco-friendly design. Environmentally sustainable practices and climate-responsive architecture contribute to creating a low-cost, comfortable indoor environment [29]. Figure 2b illustrates the layout of a Nubian house, which includes:

- (a)

- The Main Entrance: Positioned in the center of the house’s main facade, leading directly to the courtyard or, in some cases, to a lobby before the courtyard.

- (b)

- The Main Courtyard: The central space where most family activities occur, connecting the various rooms of the house. Measuring 8 × 7 m, it is a large, open, unroofed area, with a portion covered by a semi-shaded structure made of palm leaves.

- (c)

- Bedrooms: Four rooms located on the east and west sides of the house. Their doors open to the courtyard, and small ventilation windows beneath the vaults draw air from the courtyard into the rooms [30].

- (d)

- The Kitchen: Comprising two rooms, their traditional design includes a dome covering and an open vent at the top for ventilation [6].

- (e)

- Toilets: Located inside the house without dedicated ventilation solutions.

3. Methodology

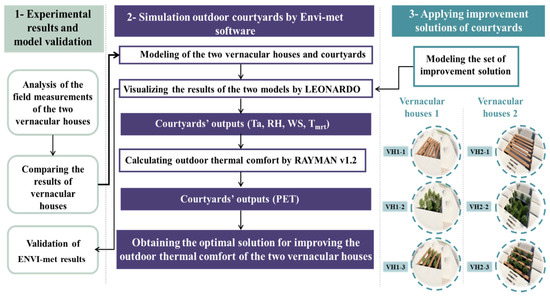

As shown in the previous section, two vernacular houses in the south of Egypt have been chosen to investigate indoor and outdoor thermal comfort. The selected case studies are located in low-density areas, which indeed influences thermal comfort by allowing greater exposure to solar radiation and reduced mutual shading between buildings. In the analysis, building density was controlled by accurately representing the surrounding built environment in the simulation models and ensuring that the same contextual conditions were maintained across all improvement scenarios. Furthermore, courtyards in Upper Egyptian vernacular architecture are uniquely adapted to extreme heat and aridity, where their enclosed geometry and shaded surfaces reduce daytime heat accumulation and promote cooler nighttime temperatures. Their performance is further enhanced by locally available materials, such as mudbrick and limestone, which possess high thermal mass and naturally regulate indoor–outdoor temperature fluctuations. Accordingly, the methodology of this study was proposed, as detailed in Figure 3. Thus, the framework of the methodology consists of three main stages as follows:

Figure 3.

The methodology framework.

- (a)

- The first stage is the experimental results of the field measurements inside the two vernacular houses, comparing the two houses’ measurements and validating the modeling results.

- (b)

- The second stage is simulating the courtyards of the two vernacular houses using ENVI-met software to assess and visualize the air temperature, relative humidity (RH), wind speed (WS), and mean radiant temperature (Tmrt). Then, Rayman software v1.2 was used to calculate the Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) as the outdoor thermal comfort index.

- (c)

- The third stage is applying the three improvement solutions to improve the outdoor thermal comfort in the courtyards and determine the optimal solution for each vernacular house.

Consequently, by conducting the proposed methodology, the study could achieve its goals in investigating the thermal influence of a set of improvement solutions on the outdoor thermal comfort of vernacular houses’ courtyards, to improve the outdoor thermal comfort and allow family activities to be performed comfortably during day and night. The study provided information to use improved courtyards of vernacular house as a solution strategy for residential houses in the hot arid climate of Upper Egypt.

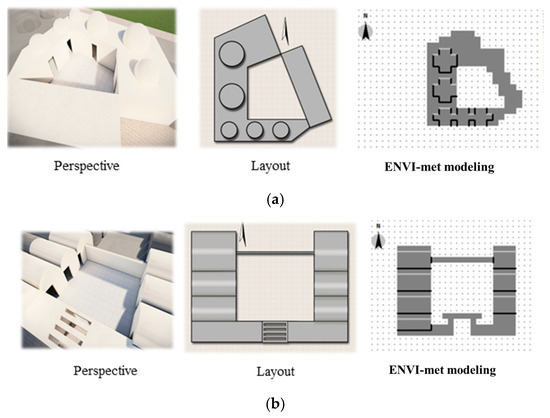

3.1. Modeling Vernacular Houses by ENVI-Met and Validation

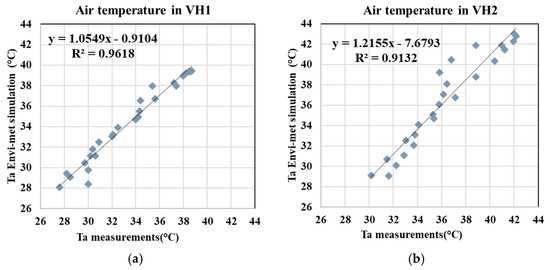

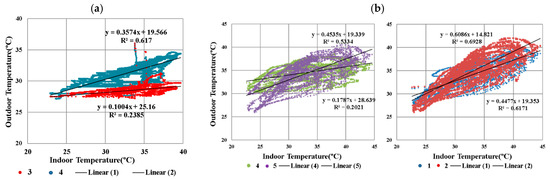

The models of the New Gourna vernacular house (VH1) and the Nubian vernacular house (VH2) have been built using ENVI-met V5.6.1 software to predict the thermal performance and outdoor thermal comfort inside their courtyards, as elaborated in Figure 4. All meteorological inputs for the ENVI-met model, including wind speed and direction, temperature, humidity, and radiation, were obtained from the METAR dataset of Luxor International Airport (ICAO: HELX). Relying on the two models’ characteristics in Table 1, the size of the ENVI-met net was 30 × 24 × 20 for the X, Y, and Z dimensions, respectively. Firstly, the field measurements of Ta, RH inside the two courtyards were monitored using a Thermo Recorder model TR72Ui on 26 April 2016 inside VH1, and on 17 May 2017 inside VH2. Measurement was conducted using data logger with time interval 30 s. The measurement devices were calibrated based on other measurement devices in the lab with accuracy (±1%RH, ±0.1 °C–10 to 95% RH and 0 to 50 °C). Secondly, the field measurements of the two cases were compared with the simulation results to validate the results of the Envi-met model. Consequently, the Coefficient of Determination (R2) for Ta was calculated as 0.96 and 0.91, in VH1 and VH2, respectively, as clarified in Figure 5. According to the good performance of the correction and determination of the coefficient, ENVI-met results are reliable in predicting the thermal performance of the two courtyards in the vernacular houses. The validation of MRT in thermal comfort was not included in this study due to limitations in the available field measurement equipment. Importantly, MRT was fully calculated within the ENVI-met simulations and incorporated into the PET evaluation. In hot-arid climates, several studies have shown that when MRT cannot be measured, air temperature is commonly used as the primary validation parameter because under highly ventilated and low-humidity conditions, operative temperature tends to converge toward air temperature [31,32]. Therefore, using air temperature as the main validation metric represents a reasonable and widely adopted approximation.

Figure 4.

The modeling of the vernacular houses; (a) VH1, and (b) VH2.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the two vernacular houses for ENVI-met modeling and validation.

Figure 5.

Linear regression of air temperature in (a) VH1 and (b) VH2.

3.2. The Improvement Solutions of the Vernacular Houses’ Courtyards

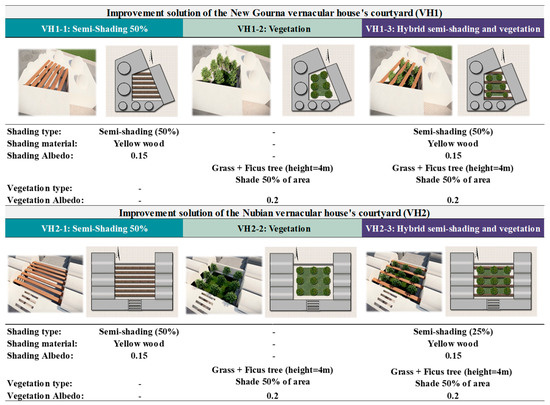

Figure 6 clarifies the proposed improvement solutions for each vernacular house to improve outdoor thermal comfort. It can be observed that the proposed solutions for the VH1 and VH2 are (a) adding semi-shading by 50% (VH1-1, VH2-1), (b) vegetation solution and adding grass area and trees (VH1-2, VH2-2), and (c) hybrid semi-shading and vegetation (VH1-3, VH2-3). The impact of vegetation on human activity space was addressed by selecting vegetation densities and shading ratios (50%) that enhance thermal comfort without obstructing circulation or usable outdoor areas. Vegetation was positioned along the courtyard perimeter and in non-central zones, ensuring that shading benefits were achieved while maintaining an open, functional activity space for users. In this study, a set of Ficus trees were chosen for vegetation solutions because they are common in the area. Additionally, all proposed solutions remain fully affordable because they rely solely on simple vegetation arrangements and lightweight wooden shading elements, which require minimal cost and maintenance. These proposed solutions have proven their effectiveness in improving outdoor thermal comfort in different types of buildings [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Consequently, the air temperature and outdoor thermal comfort improve to allow family activities to be performed comfortably during the day and the night.

Figure 6.

Description of the improvement solutions.

The proposed methodology has a set of potentials as detailed below:

- (a)

- Analyzing the indoor and outdoor thermal comfort of two different vernacular houses.

- (b)

- Proposing diverse improvement solutions to improve outdoor thermal comfort, such as vegetation, shading, and hybrid solutions.

- (c)

- The flexibility of applying the methodology to other vernacular houses, or any house with a courtyard in different desert cities in southern Egypt.

- (d)

- The application of the methodology in two different courtyards with different shapes and H/W ratios so it can be applied to other houses.

- (e)

- The ability to upgrade, to investigate the influence of the improvement solutions through the climate change issue.

Despite that, the study recognizes a set of shortcomings of the methodology:

- (a)

- The methodology ignored other improvement solutions such as albedo.

- (b)

- The study focused only on the semi-shading solution with a ratio of 50% and ignored other ratios, shapes, and materials of the shading system, as well as the effect of surface temperature of the courtyard.

- (c)

- The methodology focused on one-floor vernacular houses with courtyards and ignored other types of vernacular houses.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Indoor Thermal Environment Analysis

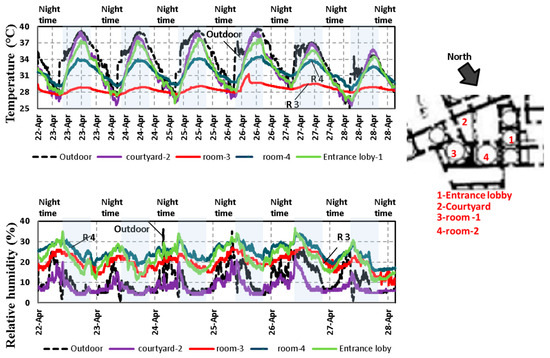

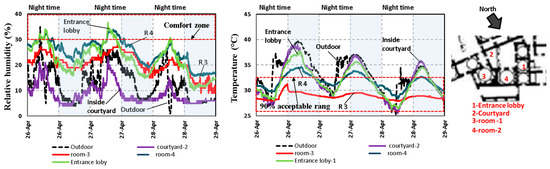

Figure 7 presents the results of indoor temperature and relative humidity monitoring in Hassan Fathy House from 22 to 28 April. The data revealed that indoor temperatures ranged from 25 °C to 39 °C. Most indoor temperatures exceeded the upper limit of the Adaptive Comfort Standard (ACS) of ANSI/ASHRAE/IES 90.2-2022 [40] (maximum temperature: 32.5 °C). The entrance lobby, Room 1, and Room 2 have effectively mitigated the indoor climate, maintaining temperatures below the maximum outdoor levels. Air temperature has been identified as a critical factor influencing indoor thermal comfort. Maarof’s [37] studies have demonstrated that changes in air temperature can significantly affect an individual’s comfort level. Relative humidity (RH) was also monitored, with results from 24 April showing that while outdoor conditions were extremely dry (average 4%), the indoor RH levels in the entrance lobby, Room 1, and Room 2 were 27%, 17%, and 28%, respectively. Although still relatively low, these indoor RH levels were more comfortable compared to the courtyard, where the RH was 5%. The design of Hassan Fathy House focused on effective cooling and necessary heating by strategically distributing rooms and orienting interior spaces toward the sun.

Figure 7.

Temperature profile of three locations in the Hassan Fathy House relative to outdoor and courtyard temperature during April 2017.

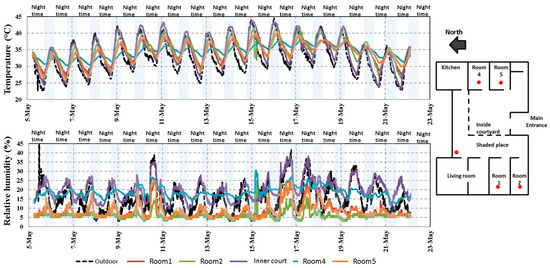

Figure 8 presents the results of indoor temperature and relative humidity monitoring in the Nubian house from 5 to 23 May. Analysis was performed using dry-bulb air temperature measurements; these values were used due to the limitations of the available monitoring equipment. According to the data, indoor temperatures in the Nubian house ranged from 23 °C to 44 °C. During the day, although all indoor temperatures exceeded the upper limit of the ACS, Rooms 1, 2, 4, and 5 managed to mitigate the indoor climate below the maximum outdoor temperatures. Relative humidity (RH) data from 7 May showed that in dry outdoor conditions (average 25%), the indoor RH levels in Rooms 1, 2, 4, and 5 were 13%, 8%, 20%, and 13%, respectively. Thus, the indoor RH levels were less comfortable, except for the courtyard, where the RH was 26%.

Figure 8.

Temperature profile of four locations in the Nubian house relative to outdoor and courtyard temperature during May 2017.

Figure 8 illustrates the temperature patterns of different points in the Hassan Fathy House (the entrance lobby, courtyard, Room 1, and Room 2) from 26 to 29 April. Generally, the temperature curve shows an increase during the day and a decrease at night. On the 26 April, indoor temperatures ranged from 25 °C to 39.1 °C, with the lowest temperatures in Room 3 (28 °C to 32 °C). The highest temperature recorded was 37.5 °C in the entrance lobby, with a relative humidity of 17%. The courtyard temperature reached 39.1 °C with 4% humidity, while the outdoor temperature reached 39.5 °C with 6% humidity. This indicates that the room temperatures were 1.6 °C lower than the courtyard and 2 °C lower than the outdoor temperature. On the 28 April, the courtyard temperature exceeded 36 °C with 5% humidity, while the outdoor temperature was 34.9 °C with 5% humidity. This suggests that the courtyard’s exposure to solar radiation increased its temperature by 1.1 °C compared to the outdoor temperature. The absence of green elements in the courtyard contributed to higher indoor temperatures. These findings agree with the results of Mousli & Semprini [41], who stated that activating a fountain in the courtyard reduced temperatures by at least 1 °C.

On the 27 April, the highest temperature in Room 3 was 29 °C with 28% humidity, while the courtyard temperature was 35 °C with 10% humidity, and the outdoor temperature reached 37 °C with 20% humidity. This indicates that Room 3 was 6 °C cooler than the courtyard and 8 °C cooler than the outdoor temperature, highlighting the significant effect of thermal insulation caused by the adobe bricks used in the Hassan Fathy House.

4.2. Thermal Comfort and Materials

In the Hassan Fathy House, the indoor temperatures at the four measurement points (entrance lobby, courtyard, Room 1, and Room 2) complied with the 90% acceptability upper limits of the ACS, with a maximum temperature of 32.5 °C. It should be noted that the adaptive comfort limits in ASHRAE Standard 55-2023 [42] are defined in terms of operative temperature, not air temperature. In our study, however, the indoor values obtained from the data loggers represent dry-bulb air temperature. Because vernacular buildings in hot-arid regions typically have thick adobe walls, low air movement, and limited radiant temperature differences, the operative temperature is usually very close to the air temperature. For this reason, using air temperature as an approximation is considered reasonable and is consistent with previous field studies conducted in similar climates. The upper comfort limit of 32.5 °C reported in the results was calculated using the Adaptive Comfort Model in ASHRAE 55-2023—Section 5.4.2.2, which defines the upper 80% acceptability limit as Tupper = 0.31 × Tpma(out) + 21.3. Applying this formula to the prevailing mean outdoor temperature measured during the monitoring period yielded a comfort threshold of approximately 32.5 °C. For clarity, all thermal comfort evaluations in this study are based on ASHRAE 55-2023, as shown in Figure 9. The use of materials with high thermal mass, such as stone, clay, and straw, helped maintain lower temperatures due to their physical properties—0.72 kJ/kg·k and 2000 kg/m3 for specific heat and density [6]. Studies have shown that buildings constructed with materials of low thermal conductivity, such as wood in the roof, provide strong thermal comfort [43]. However, the relative humidity (RH) in the Hassan Fathy House ranged between 5% and 30%, falling outside the ASHRAE thermal comfort range (30–60%), except for 26 and 27 April in the entrance lobby and Room 4.

Figure 9.

The temperature pattern of the Hassan Fathy House with different measurement locations (the authors).

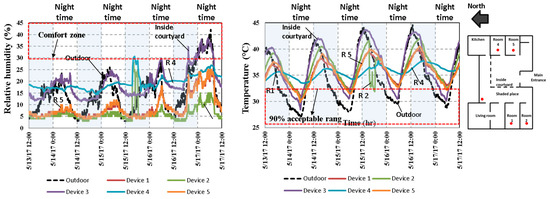

Figure 10 shows the temperature patterns of different points in the Nubian house (Room 1, Room 2, courtyard, Room 4, and Room 5) from 13 May to 17 May. Indoor temperatures ranged from 28 °C to 44.7 °C, with the lowest temperatures in Room 3 (28 °C to 32 °C). This is attributed to:

Figure 10.

The temperature pattern of the Nubian house, West Sohail, Aswan with different measurement locations (the authors).

- The use of mud bricks, a mixture of mud and gravel, which provides effective insulation.

- Wall thickness of 500 mm, which helps maintain cooler room temperatures in hot climates [6].

- Narrow, elevated openings that reduce heat exposure and sun glare while preserving privacy.

- Triangular slots in parapets and vaults that facilitate natural ventilation and reduce heat absorption [44].

- Timberless vaults made of earth bricks and mortar [6].

The results indicate a rise in temperature inside Room 2 during the day, with a peak of 42 °C and a relative humidity level of 10%. Meanwhile, the courtyard recorded a temperature of 43 °C with a relative humidity of 35%, while the outdoor temperature reached 44 °C with a relative humidity of 26%. It can be observed that the temperature in Room 2 was 1 K lower than that of the courtyard and 2 K higher than the outdoor temperature. Further, the air temperature in the courtyard was 1 K lower than the outdoor temperature. On 13 May, the temperature in Room 4 dropped to 36.5 °C with 16% humidity, while the courtyard temperature was 42 °C with 12.5% humidity, and the outdoor temperature was 41.7 °C with 16.5% humidity. This indicates that Room 4 was 5.5 °C cooler than the courtyard and 5.2 °C cooler than the outdoor temperature, demonstrating the effectiveness of solar protection and natural ventilation. These results are consistent with those of Clark [45] and El Azhary et al. [46] regarding the importance of solar protection and ventilation in moderating indoor temperatures. The air temperature in the courtyard was observed to be 0.3 K higher than the outdoor temperature, highlighting the significant influence of solar radiation on the courtyard, which led to an increase in its temperature relative to the outdoor environment. As for relative humidity (RH), the results indicated that the Nubian house generally fell outside the ASHRAE thermal comfort range of 30–60%, with RH levels ranging between 4% and 30%. However, exceptions were noted on 16 and 17 May the courtyard, as well as on May 15th in Room 4, where RH levels were within a more comfortable range, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 11 shows the regression lines between outdoor and indoor temperatures for both the Hassan Fathy House and the Nubian house. The graph shows significant linear relationships, with high R2 values. In the Hassan Fathy House, the R2 value for Room 1 was 0.2385, indicating a weak relationship between indoor and outdoor temperatures. In contrast, the R2 value for Room 2 was 0.617, indicating a strong relationship. In the Nubian house, the R2 values for Rooms 1, 2, and 3 were 0.6171, 0.6928, and 0.5334, respectively, indicating significant linear relationships. However, the correlation coefficient for Room 4, which overlooks the courtyard, was very low (0.2021). This proves that vernacular houses (The Nubian house and Fathy house) can adapt to their local climate. These findings are consistent with previous studies [47].

Figure 11.

The regression lines between daily outdoor and indoor temperatures, (a) Fathy House in two points (Entrance lobby, Courtyard), and (b) Nubian house in four points (room 1, room 2, room 4, room 5).

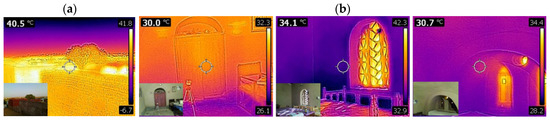

4.3. Evaluation of Indoor and Outdoor Thermography Environment and Temperature Distribution

Thermal imaging helps analyze surface temperature differences in various materials and the effects of shading techniques. It assists architects and engineers in identifying materials and methods that reduce heat absorption [32]. Thermal imaging was conducted using a FLIR (C2) camera, and images were processed using FLIR tools software 6.4. The procedure was made to assess thermal comfort levels for both indoor and outdoor areas. Figure 12a shows a thermal image of the exterior façade of the Nubian house. The floor and wall surface temperatures exceeded 40.5 °C. The red bricks used in the domes provided less thermal insulation than the mud bricks used in the rest of the structure, resulting in higher temperatures. Figure 12b shows the average air temperature distribution inside Hassan Fathy House, ranging from 30 °C to 34.1 °C. This indicates a temperature reduction of 2.7 °C to 6.7 °C compared to the exterior facade, highlighting the thermal insulation effect of adobe bricks. Also, the emissivity values range for brick and painted wall (beige color) are 0.90~0.93 and 0.80~0.90, respectively.

Figure 12.

The thermal image for the two vernacular dwellings, (a) Nubian house in West Suhail, Aswan (b) Hassan Fathy house in Gourna, Luxor.

Data monitoring, during the hot summer months of April and May in the Hassan Fathy House and the Nubian house, showed that indoor temperatures were significantly lower than outdoor temperatures. The Hassan Fathy House performed better in maintaining temperatures close to the comfort range. Fathy’s design, incorporating natural ventilation systems, demonstrates a high degree of adaptability to the Egyptian arid climate [25]. Both houses, with their thick walls and use of local materials like adobe bricks, provide effective thermal insulation. The study concludes that traditional construction methods and materials play a significant role in moderating indoor environments in extreme climates, aligning with previous research [28,44,48,49].

4.4. ENVI-Met Simulation Results of the Courtyards Improvement Solutions

4.4.1. Evaluation of Air Temperature

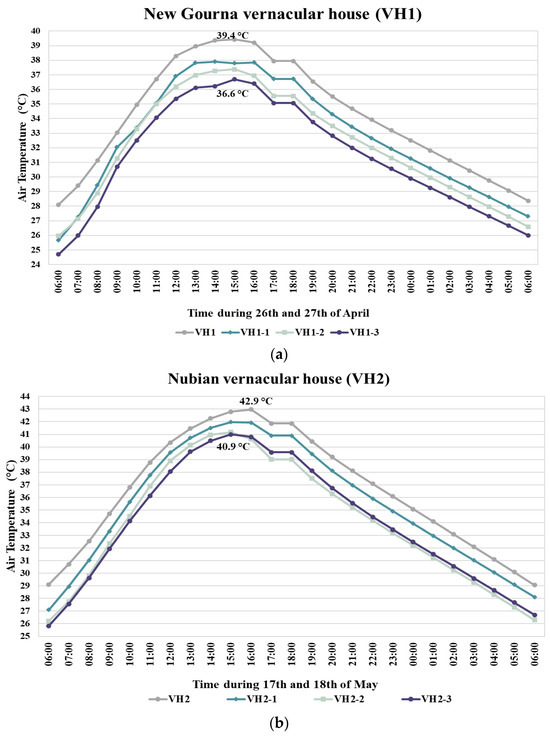

Figure 13a illustrates the variation in Ta inside the courtyard of VH1 for the base case and improvement solutions from 6:00 am on the 26 April to 6:00 am to the 27 April. In the base case (VH1), Ta reached the highest value at 15:00, and it was 39.4 °C. It can be observed that using semi-shading with a ratio of 50% (solution VH1-1) caused a slight temperature reduction in the early hours. The range of Ta reduction is from 1 °C to 2.42 °C. By applying the VH1-2 solution of adding trees, the highest Ta value was reduced to 37.7 °C. The peak reduction in Ta took place by applying the hybrid solution VH1-3 at 15:00, and it was 2.8 °C. Also, the Ta reduction ranged from 2.3 °C to 3.4 °C over the day. Hence, that result is compatible with the result of Mahmoud and Abdallah (2022) [37] who found that adding a 50% semi-shading caused a reduction of 1.5 °C, but the hybrid scenario was the highest reduction up to around 5 °C.

Figure 13.

Air temperature inside the courtyard of the base cases and improvement solutions in: (a) New Gourna vernacular house (VH1), and (b) Nubian vernacular house (VH2).

In addition, in VH2 Ta values were from 29 °C to 42.9 °C on 17th and 18 May as shown in Figure 13b. Applying a semi-shading 50% solution (VH2-1) contributed to reducing Ta by 1.0 °C at the hottest hour 15:00. All day long, the reduction ranged from 0.7 °C to 2.0 °C. Nevertheless, the vegetation in the VH2-2 solution assisted in reducing the Ta by 2.9 °C, as in from 17:00 to 4:00. Meanwhile, a significant reduction in air temperature occurred by applying the hybrid improvement solution. Further, the Ta declined from 42.9 °C in the base case to 40.9 °C in the hybrid solution at the hottest hour 15:00. Moreover, the reduction in Ta was observed over the hours, while the reduction ranged between 1.7 °C and 3.2 °C. This is evidence of the efficiency and effectiveness of the hybrid solution in reducing Ta and improving outdoor thermal comfort accordingly.

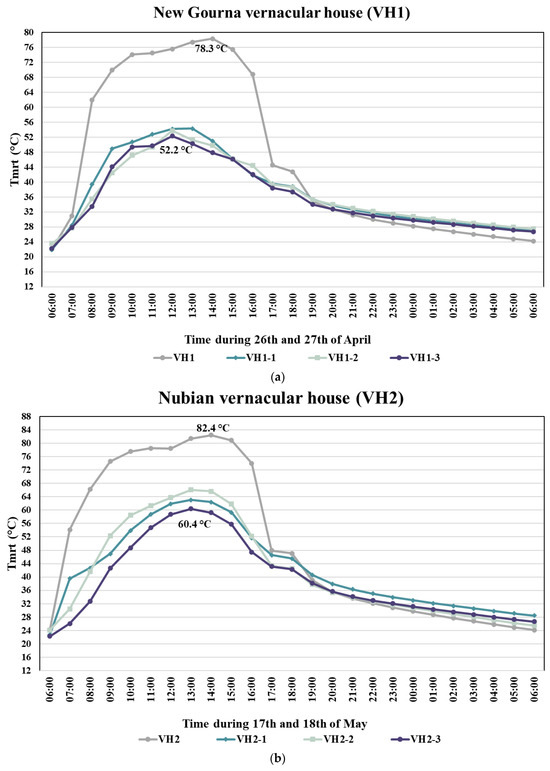

4.4.2. Evaluation of the Tmrt

Mean Radiant Temperature (Tmrt) is a crucial indicator for assessing urban radiant and thermal environments. Therefore, the calculated MRT is used to determine the physiologically equivalent temperature (PET) in the RayMan model. Although the earlier discussion focused on mean radiant temperature (MRT), it is equally important to relate these results to operative temperature, which is the key comfort indicator used in ASHRAE Standard 55. Operative temperature reflects how people actually experience the thermal environment, as it combines both the air temperature and the radiant temperature of surrounding surfaces. In the vernacular buildings examined in this study, the indoor conditions are shaped by thick adobe walls, limited air movement, and relatively uniform surface temperatures. These factors reduce differences between MRT and air temperature, meaning that the operative temperature tends to be very close to the measured air temperature. For this reason, air temperature provides a reasonable and practical approximation of operative temperature in this hot-arid context, and this relationship helps to interpret the comfort findings discussed in this paper. As illustrated in Figure 14a, the three improvement solutions caused a high reduction in the Tmrt in the courtyard of VH1. That is a result of shading almost of the courtyard area. In the base case of VH1, the peak of Tmrt was obtained at 14:00 and was 78.3 °C. Conversely, the highest value of Tmrt by applying VH1-1, VH1-2, and VH1-3 was 54.2 °C, 53.7 °C, and 52.2 °C, respectively. Furthermore, the reduction by applying VH1-1 semi-shading solution reached 29.2 °C during the daytime hours. In contrast to the nighttime hours, the Tmrt increased by a range from 0.5 °C to 2.8 °C because of the absorption and emission coefficients of the materials from which the shading is made, and are not present in the base case. Furthermore, by applying VH1-2 vegetation solution, the reduction of Tmrt goes up to 29.3 °C. Meanwhile, the VH1-3 hybrid solution assisted in dropping Tmrt by a range from 3 °C to 30.5 °C during the daytime hours.

Figure 14.

Tmrt values inside the courtyard of the base cases and improvement solutions in (a) New Gourna vernacular house (VH1), and (b) Nubian vernacular house (VH2).

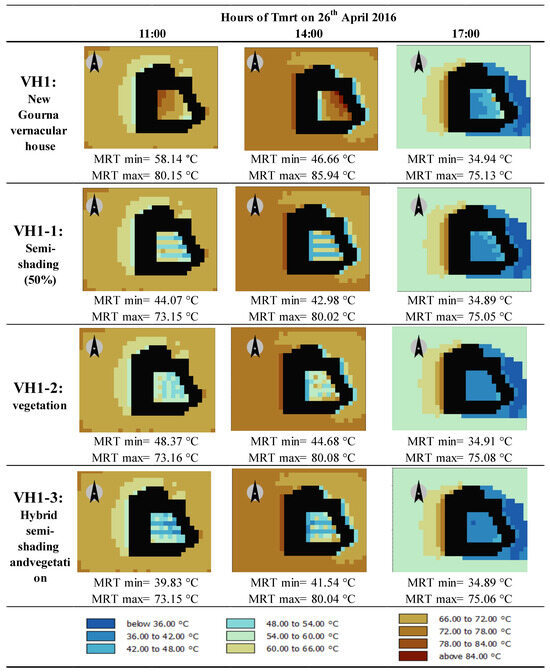

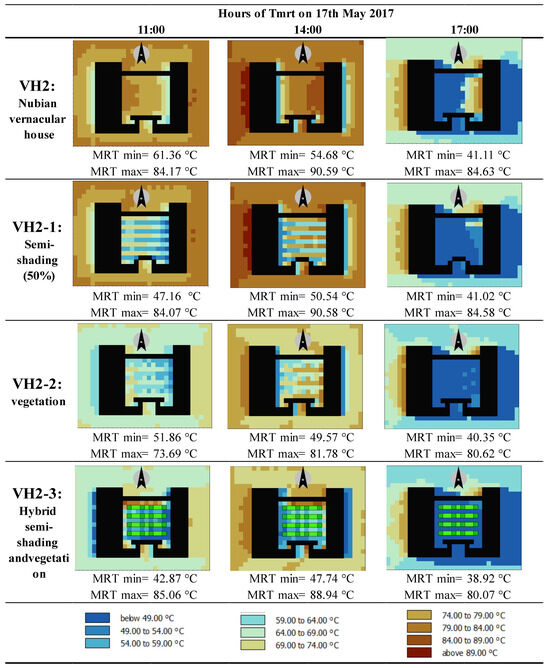

Figure 14b shows the Tmrt values of VH2, whilst the peak value was 82.4 °C at 14:00. After applying VH2-1 semi-shading solution, the Tmrt values were reduced up to 27.5 °C. On the other hand, the reduction of Tmrt in the VH2-2 vegetation solution was the lowest between solutions—24.5 °C. Because the type of trees used could not cover the wide courtyard with an area of 56 m2, it was recommended to use a big dense tree in the courtyard of the Nubian house. Even though, by applying the VH2-3 hybrid solution, the peak reduction of Tmrt was 33.4 °C at 8:00 am, and it was 25.1 °C at the hottest hour 14:00. LEONARDO as a results visualization tool of ENVI-met software was used to obtain thermal distribution maps of Tmrt of VH1, VH2, and their improvement solutions at 11:00, 14:00, and 17:00 as shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16. One can observe numerically and graphically the significant decrease of Tmrt values in the courtyards of the two vernacular houses, as a result of applying the improvement solutions that led to improved outdoor thermal comfort.

Figure 15.

The Thermal distribution map of the Gourna vernacular house (VH1) at 11:00, 14:00, and 17:00.

Figure 16.

The Thermal distribution map of the Nubian vernacular house (VH2) at 11:00, 14:00, and 17:00.

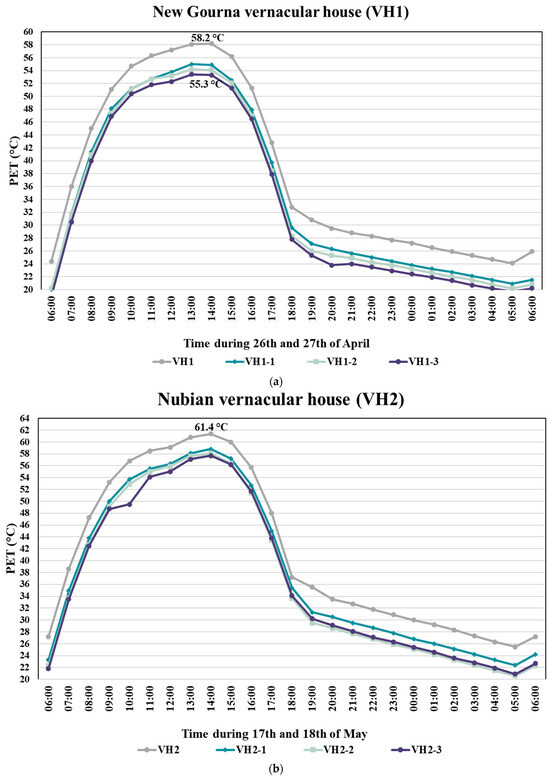

4.4.3. Evaluation of the PET

PET results for the two vernacular houses and the improvement solutions were obtained using LEONARDO outputs and RayMan outputs. The human-related parameters used in the PET calculations were defined in accordance with standard thermal comfort guidelines. These included clothing insulation (0.5–0.9 clo, depending on the season), metabolic rate (1.2 met for light activity), user profile (adult occupants), posture (standing), and activity and behavior (standing still) for ensuring reproducibility and accurate interpretation of the results. Firstly, the PET values of VH1′s courtyard are clarified in Figure 17a, while the range of PET values was between 21.4 °C and 58.2 °C. After applying VH2-1 semi-shading solution, PET dropped from 3 °C to 4.4 °C to reach the highest value is 55 °C at 13:00. As well as VH2-2 vegetation solution contributed to reducing PET by 3.6 °C to 5.1 °C. Above that, the peak of PET reduction ranging from 4.2 °C and 5.7 °C has been obtained by applying the hybrid solution of semi-shading and trees. Consequently, a hybrid solution is the most suitable solution to improve outdoor thermal comfort over the day hours to allow family activities to be performed comfortably.

Figure 17.

PET values inside the courtyard of the base cases and improvement solutions in: (a) New Gourna vernacular house (VH1), and (b) Nubian vernacular house (VH2).

Due to simulating and calculating the PET in the VH2’s courtyard, it can be observed that the high PET values reached 61.4 °C at 14:00, as illustrated in Figure 17b. After applying the VH2-1 semi-shading solution, PET reached 58.8 °C at the hottest hour, 14:00, whilst the reduction range was between 1.8 °C and 4.2 °C. Likewise, PET dropped from 3.2 °C to 6.0 °C by adding trees as in the VH2-2 solution. Additionally, the VH2-2 vegetation solution caused the lowest PET values during the night after 18:00. Furthermore, the hybrid solution (VH2-3) contributed to reducing PET to 59.7 °C at 14:00 and by the range between 3.1 °C and 7.3 °C. It can be concluded that by applying the hybrid solution of semi-shading and trees, the widest area of the courtyard was shaded. This has noticeably reduced the air temperature and mean radiant temperature and improved the outdoor thermal comfort.

Eventually, the limitations of this study are clarified as follows:

- (a)

- Improvement strategies were limited to specific shading and vegetation options, excluding other shading ratios, materials, or cooling methods.

- (b)

- The study focused only on one-floor vernacular houses and two case studies.

- (c)

- Field measurements covered short time periods and may not represent full seasonal conditions.

- (d)

- Courtyard surface temperature effects and a wider range of vegetation types were not examined.

- (e)

- MRT was not validated due to equipment limitations, and only air temperature was used for model validation.

- (f)

- The study did not evaluate other potentially influential solutions such as high-albedo surfaces, evaporative cooling elements, or courtyard surface material modifications.

- (g)

- Only one shading configuration was studied (50% semi-shading). Other shading ratios, materials, geometries, and dynamic shading systems were not investigated.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to investigate indoor and outdoor thermal comfort of two vernacular buildings in the hot arid climate of Upper Egypt and propose improved solution for courtyards to achieve sustainable development of current vernacular houses and apply the same in the arid climate zone of Egypt. The results from the measurements and simulation can be summarized as follows:

- Using adobe bricks as a material for traditional and vernacular buildings south of Egypt is considered as effective thermal insulation that moderates indoor environments in extreme climates, and lowers indoor temperature by 2.7 °C to 6.7 °C.

- Using inner courtyards without any passive solutions achieved high air temperature due to the significant influence of solar radiation on the courtyard; 0.3 K higher than the outdoor temperature.

- Significant reductions for Ta and PET values are achieved through providing hybrid shading in the courtyards of the vernacular buildings, ranging from 2.3 °C to 3.4 °C over the day, and 4.2 °C and 5.7 °C for air temperature and PET, respectively.

- Inner courtyards with shading and big dense trees achieve thermal comfort and allow family activities to be performed comfortably.

In conclusion, the study demonstrated that implementing a hybrid strategy of semi-shading structures combined with trees provides the largest shaded coverage across the courtyard. This approach has significantly lowered both air temperature and the mean radiant temperature, thereby enhancing outdoor thermal comfort. Consequently, such improvements can motivate Egyptian families to engage more actively in courtyard activities, while also contributing to a noticeable reduction in indoor temperatures in the arid climates of Upper Egypt.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; methodology, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; software, R.M.A.M.; validation, R.M.A.M.; formal analysis, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; investigation, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; resources, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; data curation, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.H.A. and R.M.A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.S.H.A., R.M.A.M., M.H.H.A. and U.A.A.; visualization, R.M.A.M.; supervision, A.S.H.A.; project administration, U.A.A.; funding acquisition, U.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Heidari, A.; Davtalab, J. Effect of Kharkhona on thermal comfort in the indoor space: A case study of Sistan region in Iran. Energy Build. 2024, 318, 114431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Guo, J.; Xia, D.; Lou, S.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhong, Z. Quantitative analysis and enhancement on passive survivability of vernacular houses in the hot and humid region of China. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Silva, S.M.; Mateus, R.; Teixeira, E.R. Analysis of the Thermal Performance and Comfort Conditions of Vernacular Rammed Earth Architecture from Southern Portugal. Ref. Modul. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2020, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; He, W.; Yan, H.; Yang, L.; Song, C. Influences of vernacular building spaces on human thermal comfort in China’s arid climate areas. Energy Build. 2021, 244, 110978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wu, Z.; Jin, R.; Liu, J. Organization and evolution of climate responsive strategies, used in Turpan vernacular buildings in arid region of China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi, O.A.M. Nubian Vernacular architecture & contemporary Aswan buildings’ enhancement. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Bokel, R.; Dobbelsteen, A.V.D. Building microclimate and summer thermal comfort in free-running buildings with diverse spaces: A Chinese vernacular house case. Build. Environ. 2014, 82, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diz-Mellado, E.; L’opez-Cabeza, V.P.; Roa-Fern’andez, J.; Rivera-G’omez, C.; Gal’an-Marín, C. Energy-saving and thermal comfort potential of vernacular urban block porosity shading. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davtalab, J.; Heidari, A. The Effect of Kharkhona on Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Hot and Dry Climate: A Case Study of Sistan Region in Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Ren, J.; Feng, C.; Tang, M. Thermal environments of vernacular dwellings and the adjacent alley in summer: An experimental study in Southwest China. Build. Environ. 2024, 261, 111634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, N.Y. Architecture design for procuring thermal comfort: Hassan Fathy, Nubia and desert building. Int. J. Islam. Archit. 2024, 13, 361–391. [Google Scholar]

- Haval, A.A. Thermal comfort through the microclimates. Acritical review of the middle-eastern courtyard house as a climatic response. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 662–674. [Google Scholar]

- Haseh, H.R.; Khakzand, M.; Ojaghlou, M. Optimal thermal characteristics of the courtyard in the hot and arid climate of Isfahan. Building 2018, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Patil, S. Vernacular architecture and indoor environmental satisfaction: Asystematic review of influencing factors. Architecture 2025, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangeli, M.; Aram, F.; Abouei, R. Energy consumption and thermal comfort of rock-cut and modern buildings. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widera, B. Comparative analysis of user comfort and thermal performance of six types of vernacular dwellings as the first step towards climate resilient, sustainable and bioclimatic architecture in western sub-Saharan Africa. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chkeir, A.; Bouzidi, Y.; El Akili, Z.; Charafeddine, M.; Kashmar, Z. Assessment of thermal comfort in the traditional and contemporary houses in Byblos: A comparative study. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 5, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toe, D.H.C.; Kubota, T. Comparative assessment of vernacular passive cooling techniques for improving indoor thermal comfort of modern terraced houses in hot–humid climate of Malaysia. Sol. Energy 2015, 114, 229–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, S.S.; Sharma, V.; Marwah, B.M. Review of energy-efficient features in vernacular architecture for improving indoor thermal comfort conditions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, M.; Mushtaha, E.; El Khazindar, A. Improvement of thermal performance and predicted mean vote in city districts: A case in the United Arab Emirates. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.; Lee, H.; Ohb, S. Challenges of passive cooling techniques in buildings: A critical review for identifying the resilient technique. J. Teknol. 2016, 78, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wei, F.; Su, S.; Cai, J.; Wei, J.; Hua, R. Effect of the envelope structure on the indoor thermal environment of low-energy residential building in humid subtropical climate: In case of brick–timber vernacular dwelling in China. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Kader, H.S.; Hassan, M.H. Improving the thermal performance of modern nubian house (wadi karkar as a case study). JES Assiut Univ. Fac. Eng. 2017, 45, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evola, G.; Marletta, L.; Natarajan, S.; Patane, E.M. Thermal inertia of heavyweight traditional buildings: Experimental measurements and simulated scenarios. Energy Procedia 2017, 133, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferruses, I.J.; Dols, S.A.; Gago, C.C. Sustainable Approaches Employed in Settlements Designed by Hassan Fathy: Lessons from New Gourna and New Baris in Egypt. J. Int. Soc. Study Vernac. Settl. 2024, 11, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S. The Earth Construction Fallacy: Hassan Fathy’s New Gourna Revisited. In Proceedings of the PLEA Conference (Re) Thinking Resilience, Wroclaw, Poland, 26 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouchene, H. Dismantling Green Colonialism: Energy and Climate Justice in the Arab Regio; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- El-deen, H.M.A.N.; Hassan Rihan, D.A.A.F.; Hamed, R.E. An analytical study to evaluate thermal performance of Nubian dwellings Before and after Displacement. J. Surv. Fish Sci. 2023, 10, 3004–3016. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, C. Egyptian Imperialism in Nubia c. 2009–1191 BC. Master’s Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, M.W.F. Nubian vernacular architecture technique to enhance Eco-Tourism in Egypt. J. Emerg. Trends Econ. Manag. Sci. 2015, 6, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.-Y.; Qin, H. The Impact of Urban Design Descriptors on Outdoor Thermal Environment: A Literature Review. Energies 2017, 10, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E.; An, X.; Ren, C.; Lee, M.; Wang, U.; He, Z. Sky view factor analysis of street canyons and its implications for daytime intra-urban air temperature differentials in high-rise, high-density urban areas of Hong Kong: A GIS-based simulation approach. Int. J. Climatol. 2010, 30, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.A. Urban morphology as an adaptation strategy to improve outdoor thermal comfort in urban residential community of new assiut city, Egypt. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H. Passive design strategies to improve student thermal comfort in Assiut University: A field study in the Faculty of Physical Education in hot season. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.A.; Ragab, A.; Gomaa, M.M. A Multi-Objective Optimization Method for Enhancing Outdoor Environmental Quality in University Courtyards in Hot Arid Climates. Buildings 2025, 15, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.A. Sustainable Mitigation Strategies for Enhancing Student Thermal Comfort in the Educational Buildings of Sohag University. Buildings 2025, 15, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.A.; Aloshan, M. Optimizing Urban Spaces: A Parametric Approach to Enhancing Outdoor Recreation Between Residential Areas in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Buildings 2025, 15, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.A.; Mahmoud, R.M.A.; Abdallah, A.S.H. A New Planning Proposal for Achieving Residents’ Thermal Comfort in Hot Arid Climate Based on Simulation Model. Mansoura Eng. J. 2023, 48, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.M.A.; Abdallah, A.S.H. Assessment of outdoor shading strategies to improve outdoor thermal comfort in school courtyards in hot and arid climates. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.2-2022; Energy-Efficient Design of Low-Rise Residential Buildings. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers and Illuminating Engineering Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- Mousli, K.; Semprini, G. Thermal performances of traditional houses in dry hot arid climate and the effect of natural ventilation on thermal comfort: A case study in Damascus. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 2893–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2023; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- Shaeri, J.; Yaghoubi, M.; Aflaki, A.; Habibi, A. Evaluation of thermal comfort in traditional houses in a tropical climate. Buildings 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernea, R.A. Contemporary Egyptian Nubia: A Symposium of the Social Research Center, American University in Cairo; Human Relations Area Files; Dar-El-Thakafa: Aswan, United Arab Emirates, 1996; Available online: https://books.google.com.eg/books/about/Contemporary_Egyptian_Nubia.html?id=z0cuAQAAIAAJ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Clark, B. Comment «devenir traditionnel» ? Premiers projets et espoirs de l’architecte Jean Hensens (1929–2006) au Maroc. CLARA 2023, 8, 170–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Azhary, K.; Ouakarrouch, M.; Laaroussi, N.; Garoum, M. Energy efficiency of a vernacular building design and materials in hot arid climate: Experimental and numerical approach. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2021, 10, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, T.; Shi, C.; Tian, L.; Zhang, T.; Fukuda, H. Research on indoor thermal comfort of traditional dwellings in Northeast Sichuan based on the thermal comfort evaluation model and EnergyPlus. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 5234–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, N.A.M.; Behaz, A.; Denan, Z. Thermal comfort studies on houses in hot arid climates. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 401, 12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, H.; Gelan, E.; Girma, Y. Indoor thermal comfort analysis: A case study of modern and traditional buildings in hot-arid climatic region of Ethiopia. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).