Abstract

This paper focuses on the resource utilization of phosphogypsum, a major industrial by-product from phosphate fertilizer production, in highway engineering materials, exploring its performance optimization and collaborative modification mechanisms. Phosphogypsum, primarily composed of CaSO4·2H2O, faces challenges such as acidity (pH ≈ 3.56), poor water resistance, and strength limitations, which hinder its engineering application. This study investigates pretreatment methods (e.g., lime neutralization, physical grinding) and the synergistic effects of additives like metakaolin, steel slag, slag powder, and stone powder. The results show that adjusting phosphogypsum’s pH to 10 via lime neutralization significantly improves its mechanical properties, with its 28-day compressive strength increasing by 21%. The optimal dosage of cement as an alkaline activator is 4%, while steel slag performs best at 10%. Metakaolin (11% dosage) enhances the 28-day strength of 30% phosphogypsum-containing systems by 89–114% through pozzolanic reactions, forming a high-strength aluminosilicate network, enabling the preparation of C35 concrete with a 28-day strength of 44.5 MPa. Additionally, stone powder exhibits the most effective strength improvement, with the 56-day strength increasing by 12.5 MPa compared with the reference group. Economically, utilizing 30% phosphogypsum and 11% metakaolin reduces C35 concrete costs by 15–20%. This research provides theoretical and technical support for the large-scale application of phosphogypsum in highway engineering, addressing environmental and economic challenges.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of continuous global industrialization, the resource utilization of industrial solid waste has emerged as a pivotal issue for sustainable development. Phosphogypsum, the primary by-product from phosphate fertilizer production, is generated in enormous annual quantities [1]. Data indicates that approximately 5 to 7 tons of phosphogypsum are produced for every 1 ton of phosphoric acid manufactured. The accumulation of large quantities of phosphogypsum not only occupies land resources but also poses environmental risks such as soil and water pollution. In terms of resource attributes, phosphogypsum is primarily composed of CaSO4·2H2O (calcium sulfate dihydrate), containing about 18% crystalline water and impurities like SiO2 and P2O5 [2]. Its microstructure features cross-stacked platy crystals, endowing it with certain cementitious potential. However, natural phosphogypsum suffers from defects such as non-cementitious properties, poor water resistance, and acidity (with a pH value of approximately 3.56), directly limiting its scope of engineering applications [3].

In the field of construction materials, the resource utilization of industrial waste residues has become a critical approach to addressing environmental pollution and resource shortages [4]. Scholars have conducted extensive research on the application of industrial waste residues such as slag and steel slag in cementitious materials. These residues, due to their potential cementitious or pozzolanic activity, can serve as cement substitutes or admixtures to improve concrete performance [5]. For example, slag can undergo hydration reactions to form cementitious products under the action of alkaline activators, significantly enhancing the late-stage strength and durability of concrete. Ground steel slag can participate in cement hydration, optimizing the paste structure [5]. Nevertheless, existing research mainly focuses on the modification and application of single waste residues, while studies on the synergistic mechanisms and performance regulation of multi-waste composite systems remain conspicuously insufficient [6].

The resource utilization of phosphogypsum, as the main by-product of phosphate fertilizer production, faces significant challenges [7]. Sun pointed out that although phosphogypsum possesses some characteristics of air-hardening cementitious materials (such as a light weight and high strength), its poor water resistance severely restricts its engineering applications, necessitating modification to transform it from an air-hardening material into a hydraulic cementitious material [8]. Research has shown that the acidic characteristics of phosphogypsum (pH~3.56) and its soluble impurities such as phosphorus and fluorine are the key factors leading to its performance defects: acidic substances consume the Ca(OH)2 generated during cement hydration, delaying the hydration process; soluble phosphorus can form calcium phosphate precipitates at an early stage, covering the surfaces of cement particles and hindering strength development; and soluble fluorine promotes the coarsening of gypsum crystals, weakening the intercrystalline bonding strength [9].

The pretreatment of phosphogypsum is a critical link to improving its engineering properties, and various pretreatment methods have been developed to remove impurities or optimize the microstructure [10]. The water washing method can effectively reduce the content of soluble phosphorus and fluorine in phosphogypsum, but it suffers from high water consumption and treatment costs [11]. Screening and aging treatment reduce caking through physical classification and natural aging, but they hardly eliminate the impact of acidic substances [12]. In terms of chemical modification, citric acid treatment can complex heavy metal ions, while the lime neutralization method raises the pH value of phosphogypsum from 3.56 to weakly alkaline (e.g., pH = 10) through acid–base reactions. This not only neutralizes acidic impurities but also improves its hydrophobicity via hydrogen bonding between Ca(OH)2 and hydroxyl groups on the phosphogypsum surface [13]. Physical grinding modification refines crystal particles through ball milling. When the specific surface area reaches a certain threshold (e.g., after 5 min of ball milling), the compressive strength of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials can increase by 20–30%. However, over-grinding will cause damage to the crystal structure, leading to a decrease in strength instead.

The selection and dosage of alkaline activators directly influence the setting and hardening properties of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials. In traditional research, single alkaline activators (such as NaOH and Na2SiO3) can accelerate hydration, but they easily cause an alkalinity imbalance in the system, leading to efflorescence or volume expansion [14]. Studies have shown that the cement–slag composite activation system can provide an alkaline environment through cement hydration, while slag and CaSO4·2H2O in phosphogypsum synergistically react to form ettringite (AFt). When the cement dosage is 4%, the 28-day compressive strength of the system can reach 38.3 MPa [15]. In contrast, when quicklime is used as a single activator, a dosage exceeding 2% will lead to late-stage strength degradation due to the volume expansion (97% volume increase) during CaO hydration. Moreover, quicklime is prone to hygroscopic carbonation, making it difficult to control in actual production. When steel slag is used as an alkaline component, its active phases such as C3S and C2S can participate in hydration, but excessive steel slag (e.g., exceeding 10%) will inhibit the formation of cementitious products due to the high content of Fe2O3, and the optimal dosage should be controlled at about 10% [16].

As a highly active pozzolanic material, the application of metakaolin in phosphogypsum-based cementitious systems has gradually attracted attention in recent years. Existing studies have shown that the amorphous SiO2 and Al2O3 in metakaolin can undergo pozzolanic reactions with the Ca(OH)2 generated by cement hydration to form C-S-H-like gels and aluminosilicate network structures, whose strength is superior to traditional C-S-H gels [17]. Further research has found that when the metakaolin dosage is 11%, the 28-day compressive strength of the cementitious system with 30% phosphogypsum can reach 44.5 MPa, which is 89–114% higher than that of the unblended system. This strengthening effect originates from a dual mechanism: on the one hand, the pozzolanic reaction of metakaolin consumes Ca(OH)2, promoting the hydration balance of cement; on the other hand, its acidic environment promotes the depolymerization–repolymerization of aluminosilicate compounds, forming a dense network structure that counteracts the retarding effect of phosphogypsum. It is worth noting that when the phosphogypsum dosage exceeds 30%, the strengthening efficiency of metakaolin decreases significantly, which is related to the acidic environment of phosphogypsum weakening the activity of metakaolin [18].

In practical engineering applications, phosphogypsum-based concrete faces the dual challenges of setting time regulation and durability assurance. Existing studies have shown that replacing cement with phosphogypsum significantly prolongs the setting time (e.g., the final setting time reaches 27.5 h at a 30% phosphogypsum dosage), which is related to the formation of an insoluble film layer by phosphate ions adsorbed onto the surface of phosphogypsum [19]. The setting time can be controlled within a reasonable range by compounding metakaolin and high-range water reducers, but the contradiction between strength and workability needs to be balanced. In terms of durability, the sulfates in phosphogypsum may cause internal sulfate erosion in concrete [20]. However, a previous study found that when the system alkalinity is regulated to pH = 10, the micro-aggregate effect of phosphogypsum can improve the compactness of concrete, and its impermeability and freeze–thaw resistance are close to those of ordinary concrete [21]. Nevertheless, the performance stability of phosphogypsum-based concrete under long-term exposure to humid environments still lacks systematic research. Existing engineering cases (such as highway precast components in Yunnan Province) have only verified its short-term applicability, and long-term performance data urgently need to be supplemented [22].

From the perspective of sustainable development, the resource utilization of phosphogypsum has significant environmental benefits. The utilization of 1 ton of phosphogypsum can reduce land occupation by 0.8 square meters and mitigate the ecological risks of pollutants such as phosphorus and fluorine [23]. Economically, the incorporation of industrial waste residues can reduce cement consumption. When the phosphogypsum dosage is 30% and the metakaolin dosage is 11%, the cost of C35 concrete is reduced by 15–20% compared with traditional formulas [24]. However, pretreatment processes (such as ball milling and lime neutralization) will increase initial investment, which needs to be amortized through large-scale production. Existing studies have shown that when the annual utilization of phosphogypsum exceeds 100,000 tons, the pretreatment production line can achieve break-even, providing an economic feasibility basis for the large-scale application of phosphogypsum in highway engineering [25,26]. Although existing studies have made progress in phosphogypsum pretreatment and alkaline activation mechanisms, the following shortcomings still exist. The synergistic mechanism of multi-waste composite systems (such as phosphogypsum–steel slag–slag) is still unclear. Durability data of phosphogypsum-based materials in complex environments (such as saline soil and freeze–thaw cycles) are scarce. Standardized production processes and quality control criteria for engineering applications have not been unified.

The traditional Portland cement system (based on P · II 42.5 cement) is widely used in highway engineering, but its production process consumes large amounts of energy (about 300 kg standard coal/ton cement), has large carbon emissions (about 0.8 tons CO2/ton cement), and its cost is significantly affected by fluctuations in cement prices. The core differences between the phosphogypsum-based cementitious system developed in this study (containing 30% phosphogypsum and 11% metakaolin) and the traditional system are as follows.

The comparison of mechanical properties is shown in Table 1. The 28-day compressive strength of traditional P · II 42.5 cement concrete is 47.6 MPa, while the 28-day compressive strength of this system reaches 44.5 MPa (C35 grade), which is slightly lower but meets the strength requirements of highway prefabricated components such as curbstones and permeable bricks. The 56 d compressive strength of this system still maintains an increase (35.6 MPa), while the 56 d strength of the traditional system is basically stable (48.2 MPa), reflecting the advantage of sustained strength development in the later stage.

Table 1.

Performance comparison between phosphogypsum-based cementitious system and traditional Portland cement system.

In the sulfate attack environment (5% Na2SO4 solution), the strength loss rate of the traditional cement system reached 18% in six months, while the strength loss rate of this system was only 6.2% due to the compact structure of C-A-S-H gel and the stable distribution of Aft. In terms of frost resistance, the quality loss rate of D15 in this system after freeze–thaw cycles is 0.8%, which is basically the same as the traditional system (0.7%).

The cost of traditional C35 concrete material is about 420 CNY/m3 (with a cement dosage of 380 kg/m3). In this system, due to the addition of 30% phosphogypsum (with a cost of 54 CNY/ton) and 11% metakaolin (with a cost of 1200 CNY/ton), the cement dosage has been reduced to 224.2 kg/m3, and the material cost has been reduced to 355.76 CNY/m3, a decrease of 15.3%. Moreover, using 1 ton of phosphogypsum can reduce land occupation by 0.8 square meters, with significant environmental benefits.

The commonly used industrial solid waste cementitious systems in current highway engineering include slag powder cement system, fly ash cement system, etc. The technical differences and advantages of the phosphogypsum-based system and these systems in this study are as follows:

The 28-day compressive strength of the slag powder cement system (with a slag powder content of 30%) is about 40.2 MPa, and it relies on cement to provide an alkaline environment (with a cement content of ≥250 kg/m3). In addition, the activation of slag powder activity requires the addition of NaOH (with a content of 2%), which increases costs and construction complexity; this system synergistically reacts with metakaolin volcanic ash in an acidic environment of phosphogypsum, without the need for additional alkaline activators. The cement dosage is reduced to 224.2 kg/m3, and the phosphogypsum content (30%) is higher than the slag powder content, resulting in a higher solid waste utilization rate.

For the fly ash cement system, the 28-day compressive strength of the cement system with a 20% first-grade fly ash content is about 38.5 MPa, but its early strength is low (7-day compressive strength of 18.3 MPa) and the curing time needs to be extended; the compressive strength of this system reached 22.0 MPa after 7 days, and the early strength development was faster. In addition, the fly ash needs to be dried (with an energy consumption of about 50 kg standard coal/ton). In this study, phosphogypsum only requires lime neutralization (0.98% dosage) and physical grinding (5 min), reducing pretreatment energy consumption by 60%.

Previous studies, such as the phosphogypsum steel slag fly ash system, have achieved the synergy of multiple solid wastes. However, when the steel slag content exceeds 10%, the hydration is inhibited by Fe2O3 (resulting in a 12% decrease in 28-day strength). In contrast, this system utilizes the synergy of 10% steel slag and 11% metakaolin to fully stimulate the active phases of C2S and C III S in the steel slag, resulting in a 28% increase in 28-day strength compared with a single steel slag addition system, solving the problem of strength inhibition caused by excessive steel slag.

The core objective of this study is to promote the large-scale application of phosphogypsum in highway engineering, and to reveal the multi-component synergistic modification mechanism of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials. With phosphogypsum as the core raw material, through lime neutralization (pH adjusted to 10) and physical grinding (5 min, specific surface area of 4476 cm2/g) pretreatment, combined with XRD, SEM, and other microscopic characterization, it is clear that the “acid regulation pozzolanic reaction alkaline excitation” coupling law in the “phosphogypsum (30%), metakaolin (11%), steel slag (10%), cement (4%)” four-component system clarifies the contribution mechanism of the synergistic generation of C-A-S-H gel and AFt to strength improvement, and fills the blank of multi-waste synergy theory. This study achieves the following: constructing a performance control system for phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials suitable for highway engineering; optimizing the mix proportion through single factor and orthogonal experiments; and achieving a compressive strength of ≥20 MPa at 7 d (meeting the requirements of rapid demolding), a compressive strength of ≥40 MPa at 28 d (reaching C35 grade), a strength loss rate of ≤12% after 150 freeze–thaw cycles, and a strength loss rate of ≤8% after 180 d sulfate attack. At the same time, the final setting time is controlled within 800–900 min (suitable for assembly line production), solving the problem of a single material’s performance in existing materials. Based on the practice of the Chuyao Expressway project in Yunnan, a standardized process of “phosphogypsum pretreatment concrete mixing (biaxial pre mixing for 2 min)—impact compression molding (3 MPa)—standard curing” has been established to reduce the cost of phosphogypsum pretreatment to ≤45 CNY/ton, achieve a 15–20% reduction in the material cost of C35 concrete compared with the traditional system, and form a replicable industrial technology solution.

2. Raw Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Phosphogypsum

The phosphogypsum waste produced and stacked by Yuntianhua Group Co., Ltd. in Anning City, Yunnan Province, China, was used. The phosphogypsum discharged from the phosphorus field has a high water content, easy caking, strong acidity, and pungent odor. The phosphogypsum used in the study is shown in Figure 1, which is grayish yellow.

Figure 1.

Phosphogypsum.

Impurities such as phosphorus, fluorine, and organic matter are unevenly distributed in phosphogypsum, and the larger the particles, the higher the impurity content. Therefore, through screening, impurities can be enriched, larger particle sizes of phosphogypsum can be removed, and the content of soluble phosphorus, fluorine, and organic matter can be reduced. The crushed phosphogypsum was passed through 1.18 mm, 0.6 mm, 0.3 mm, 0.15 mm, and 0.075 mm square hole sieves. The particle size distribution of phosphogypsum was obtained through the dry screening method and water washing method, and the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Particle gradation of phosphogypsum.

From Table 2, it can be seen that after crushing the agglomerated phosphogypsum and sieving, all particles could pass through the 1.18 mm square hole sieve, and the diameter of the phosphogypsum particles was less than 1.18 mm. The pass rate of the water washing method is higher than that of the dry sieving method because during the water washing process, some impurities attached to the surface of the phosphogypsum particles are washed away or combined into larger phosphogypsum particles due to the action of attached water, which are washed into smaller particles. Therefore, the phosphogypsum particles using the water washing method have a higher pass rate and finer particles. However, the water washing method is cumbersome and costly, and the residual water containing impurities still needs to be treated before discharge, which is not conducive to engineering use. Therefore, the dry screening method is generally used in engineering.

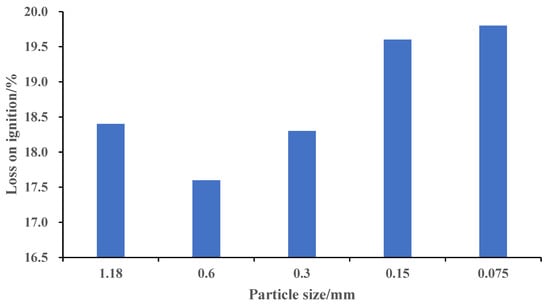

In order to determine the aperture size for screening treatment, a loss on ignition test was conducted on phosphogypsum passing through various square hole screens. The loss on ignition of phosphogypsum mainly reflects the mass change caused by the volatilization of organic matter, impurity fluorine, and impurity phosphorus in phosphogypsum after calcination. The results are shown in Figure 2 (the horizontal axis particle size of 0.6 mm in the figure represents all particle sizes of phosphogypsum samples passing through a 0.6 mm square hole sieve, and the same applies to others).

Figure 2.

Loss on ignition of phosphogypsum.

From Figure 2, it can be seen that the phosphogypsum passing through the 0.6 mm square hole sieve has the smallest loss on ignition, indicating that the stable components of phosphogypsum passing through the 0.6 mm square hole sieve account for a relatively large proportion, while the impurities such as P2O5 evaporated from the flue gas in the loss on ignition test are relatively small. Therefore, a 0.6 mm square hole sieve is used as the passing aperture for screening treatment.

In summary, the pass rate of the dry screening method for screening phosphogypsum through a 0.6 mm square hole sieve is 91.6%, and the composition of phosphogypsum passing through the 0.6 mm square hole sieve is stable. In the subsequent phosphogypsum screening treatment, the method of dry screening through a 0.6 mm square hole sieve was adopted.

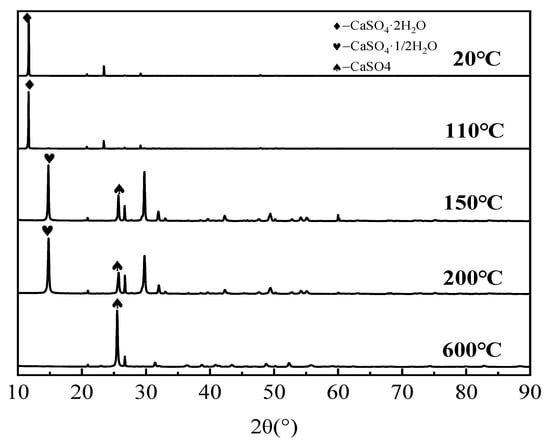

The main component of phosphogypsum is CaSO4 · 2H2O, which does not have gelling properties and needs to be modified to convert CaSO4 · 2H2O from 3/2H2O to CaSO4 · 1/2H2O or from 2H2O to CaSO4, making it gelatinous. The usual treatment methods are high-temperature calcination or dehydration. Phosphogypsum can be dehydrated at 110 °C, 150 °C, or 200 °C, and calcined at 600 °C for 6 h. Figure 3 shows the XRD diffraction patterns of phosphogypsum samples at 110 °C, 150 °C, 200 °C, 600 °C, and in their original state.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of phosphogypsum at different temperatures.

From Figure 3, it can be seen that the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 11° and 2θ = 15° correspond to CaSO4·2H2O and CaSO4·1/2H2O, respectively. It can be clearly seen that the phosphogypsum at 150 °C and 200 °C no longer has CaSO4·2H2O, while the main component of phosphogypsum at 110 °C and room temperature is still CaSO4·2H2O; the diffraction peak at 2θ = 26° is CaSO4. Phosphogypsum already has a small amount of CaSO4·2H2O converted to CaSO4 by removing 2H2O at 150 °C and 200 °C, but its main component is CaSO4·1/2H2O; phosphogypsum is completely transformed into CaSO4 when calcined at 600 °C. It can be inferred that below 110 °C, the main components of phosphogypsum will not undergo any significant changes. Dehydration treatment at 150 °C and above produces phosphogypsum, with the main component transformed into CaSO4·1/2H2O. After calcination at 600 °C, the main component of phosphogypsum is completely dehydrated to CaSO4. To gain a more intuitive understanding of the compositional changes in phosphogypsum after different temperature treatments, the chemical composition of phosphogypsum after different temperature treatments was measured using an XRF spectrometer, and the results are shown in Table 3. From Table 3, it can be seen that the impurities such as fluorine, phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium in the composition of heat-treated phosphogypsum are significantly reduced.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of PG at different temperatures (%).

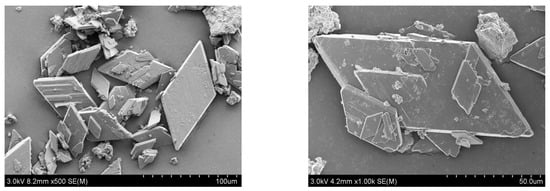

Phosphogypsum mainly consists of CaSO4·2H2O and SiO2. The microstructure of phosphogypsum observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is shown in Figure 4. Phosphogypsum has a complex polycrystalline structure, in which CaSO4·2H2O crystals are mainly plate-like with regular rhombus, parallelogram, and triangular cross-sections, featuring distinct edges and corners. The crystals vary in size and intersect with each other. The crystal surfaces also have some broken crystals, fine crystals, and other impurities attached.

Figure 4.

SEM (scanning electron microscope) image of phosphogypsum (magnified 1000 times).

Phosphogypsum possesses partial properties of gypsum. As an excellent air-hardening cementitious material, it features a light weight, high strength, and multifunctionality. However, its poor water resistance limits its application. To prepare the required cementitious material from phosphogypsum, modification treatment is necessary to transform it from an air-hardening to a hydraulic cementitious material. Usually, admixtures such as alkaline activators and composite admixtures are added to phosphogypsum to improve its strength and water resistance, enabling it to function better and adapt to different conditions, environments, and application requirements.

2.1.2. Cement

Table 4.

Main chemical components of cement.

Table 5.

Main physical and mechanical performance indicators of cement.

2.1.3. Aggregates

The aggregates were selected from the aggregate yard of the Kunming Iron and Steel Group. The fine aggregate has a stone powder content of 11.5% and a fineness modulus of 2.9. The coarse aggregate has a crush value of 17.7%, a flakiness content of 3.2%, a mud content of 0.9%, a mud block content of 0.3%, a void ratio of 45.6%, and a good gradation, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Coarse aggregate.

2.1.4. Metakaolin

The high-activity metakaolin from Yunnan Tianhong Kaolin Mining Co., Ltd. is a reddish-brown powder, and its main chemical composition is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Main chemical composition of metakaolin.

2.1.5. Steel Slag

The steel slag was taken from Kunming Iron and Steel Holding Co., Ltd. in the Kunming, China, with an attached water content of less than 1%. After drying in an oven at 105 °C to remove the attached water, 0.5‰ triethanolamine was added, and it was ball-milled by a ball mill to a specific surface area of 500 ± 10 m2/kg. The chemical composition analysis of the steel slag was carried out and the results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Main chemical components of steel slag.

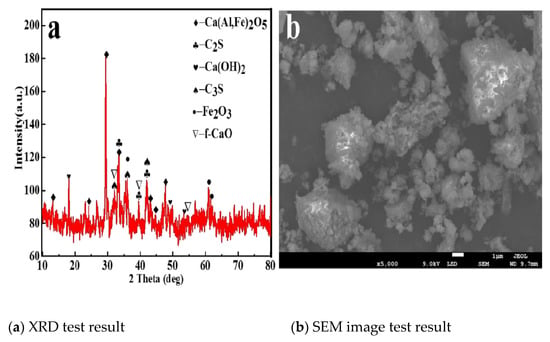

Figure 6 shows the XRD and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the steel slag. From the XRD pattern, the phases of the steel slag include calcium ferroaluminate, dicalcium silicate, tricalcium silicate, ferric oxide, free calcium oxide, ferromagnesian compounds, etc. The SEM image reveals that the crystal structure of the steel slag mainly exists in the form of spherical and irregular lumps.

Figure 6.

X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy images of steel slag.

2.1.6. Fly Ash

Fly ash is a mixture with pozzolanic activity generated by the high-temperature combustion of coal powder, and it is a powdery substance collected from coal powder flue gas. It is mainly composed of active SiO2 and Al2O3 and contains a small amount of CaO. It has no or slightly hydraulic cementitious properties, but in the presence of water, it can chemically react with Ca(OH)2 to form hydraulic cementitious hydration products, thereby enhancing the strength of the mixture. The fly ash used in this experiment is from Pingdingshan, which is dry-discharged fly ash; its chemical composition is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Chemical composition of fly ash.

2.1.7. Lime

Quicklime is an indispensable material in the pretreatment of phosphogypsum. Its main role is to undergo a neutralization reaction with residual acidic substances such as phosphoric acid in phosphogypsum after digestion treatment, so as to remove acidic impurities and adjust the pH of phosphogypsum to weak alkalinity. Meanwhile, a certain proportion of quicklime can also inhibit the mossing of phosphogypsum caused by its organic matter. The quicklime used in this experiment is produced by a manufacturer in Penglai, and its main chemical components and contents are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Chemical composition of quicklime.

2.1.8. Water Reducer

Carboxylic acid water reducers have a good water reduction effect and can significantly improve the carbonation resistance of cement, as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Composition of performance of water reducers.

2.2. Test Contents

The chemical composition, phase composition, and crystalline morphology of raw materials such as phosphogypsum, steel slag, and cement were analyzed using X-ray diffraction analysis, scanning electron microscopy, and chemical analysis methods.

Phosphogypsum was pretreated by quicklime neutralization and physical grinding methods to study the effects of pretreated phosphogypsum on the setting time and strength of cement concrete.

Using the single-factor method step by step, with physical and mechanical properties as evaluation indices, the coordination ratios among phosphogypsum, slag, fly ash, and cement were studied to determine the optimal mix proportion in this system and optimize the composition of phosphogypsum cement.

By adjusting the admixtures of cement concrete, a mineral admixture containing phosphogypsum was developed to prepare concrete that meets the strength requirements of precast components. Through optimizing the addition method of phosphogypsum raw materials and curing methods, a process for the engineering-scale production of precast components was formed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Phosphogypsum Modification Technology

3.1.1. Effect of Quicklime Modification on pH Value of Phosphogypsum

Phosphogypsum, as a major industrial by-product generated during the production of phosphate fertilizers, has a natural acidity (pH ≈ 3.56) that is one of the key bottlenecks restricting its application in cementitious material systems. An acidic environment not only delays the hydration process of cement, but may also cause adverse reactions with other components in the system, leading to a decrease in material mechanical properties. Therefore, the core pretreatment step for improving the performance of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials is to pretreat phosphogypsum using the quicklime neutralization method and regulate its pH value to an appropriate range.

The pH test results of the phosphogypsum mixture system under different amounts of quicklime are shown in Table 11. From the data in the table, it can be clearly observed that the regulation of the pH value of phosphogypsum by the dosage of quicklime shows a characteristic of “low dosage sensitivity, high dosage slowing down”:

Table 11.

Effect of quicklime dosage on pH value of phosphogypsum.

When the dosage of quicklime is 0, the pH value of the phosphogypsum system is 3.56 ± 0.02, showing strong acidity, consistent with the acidic characteristics of natural phosphogypsum. At this time, residual acidic impurities such as phosphoric acid and fluoride in the system are not neutralized, which means that the alkaline environment requirements of cementitious materials are not met.

As the dosage of quicklime increased from 0.6% to 0.98%, the pH value of the system rapidly rose from 6.22 ± 0.02 to 9.97 ± 0.01, approaching the neutral to weakly alkaline range. The significant increase in pH value during this stage is mainly attributed to the intense neutralization reaction between quicklime and acidic substances in phosphogypsum: CaO first reacts with water to generate Ca(OH)2(CaO + H2O = Ca(OH)2), and the generated Ca(OH)2 further reacts with acidic impurities such as H4PO4 and HF in phosphogypsum to generate stable compounds such as Ca3(PO4)2 and CaF2, while consuming H+ in the system, causing the pH value to rise rapidly. When the dosage of quicklime reaches 0.98%, the pH value reaches 9.97 ± 0.01, which can be approximately considered as pH = 10. At this point, the system is already in a weakly alkaline environment and can provide suitable alkaline conditions for subsequent cement hydration.

When the dosage of quicklime continues to increase above 1.0% (such as 1.1%, 5%, and 9%), although the pH value of the system still increases, the growth rate slows down significantly. For example, when the dosage increases from 0.98% to 1.0%, the pH value only increases from 9.97 ± 0.01 to 10.14 ± 0.02; When the dosage increased from 1.0% to 9.0%, the pH value increased from 10.14 ± 0.02 to 12.04 ± 0.02, which was much lower than the low dosage stage. This is because when the amount of quicklime exceeds the theoretical amount required to neutralize acidic impurities in phosphogypsum, excess Ca(OH)2 will dissolve in the system, causing a slow increase in the concentration of OH− in the solution. However, due to the limitation of Ca(OH)2 solubility (about 1.65 g/L at 20 °C), the concentration of OH− cannot increase rapidly, resulting in a slower increase in pH value.

From an engineering application perspective, pH regulation needs to balance “performance requirements” and “economic costs”: if the pH value is too low (such as pH = 8, corresponding to a quicklime dosage of 0.67%), the system is still weakly acidic and cannot completely eliminate the inhibitory effect of acidic impurities on cement hydration; if the pH value is too high (such as pH = 12, corresponding to a quicklime dosage of 9%), although it can provide a strong alkaline environment, excessive quicklime not only increases production costs, but also may cause microcracks inside the subsequent cementitious material due to CaO hydration volume expansion (expansion rate of about 97%), affecting the material’s volume stability. Therefore, taking into account the pH regulation effect, material performance requirements, and economy, the subsequent experiment chooses to adjust the pH value of phosphogypsum to around 10 (corresponding to a quicklime dosage of about 0.98%). At this time, it can effectively neutralize acidic impurities, create a suitable alkaline environment for cement hydration, and avoid the cost increase and volume stability problems caused by excessive quicklime.

3.1.2. Influence of Quicklime Modification on Mechanical Properties of Composite Materials

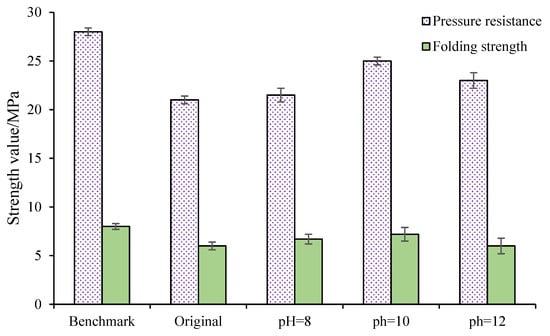

The influence of the pH value of phosphogypsum on the strength of cement concrete was studied by adding 30% phosphogypsum externally and adjusting the pH value to 8, 10, and 12, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The effect of phosphogypsum pH on cement concrete strength.

As shown in Figure 7, after adding 30% phosphogypsum externally, the 7-day compressive strength of cement mortar decreased by 26.8%, and the flexural strength decreased by 32.2%. Adjusting the pH value of phosphogypsum with quicklime showed an insignificant improvement in strength reduction when the pH was 8 or 12, while pH = 10 significantly enhanced the compressive and flexural strengths by 21% and 13%, respectively, compared with the original phosphogypsum. This is mainly because quicklime and phosphogypsum primarily act as aggregates in the early stage, and the early strength depends on the amount of gel formed and the compactness of the structure between the gel and aggregates. Meanwhile, the weak acidity of phosphogypsum delays the early-stage increase in matrix alkalinity, hindering the progress of cement hydration reactions, thus causing slow setting and low strength in the cement mortar matrix. As the reaction proceeds, a large amount of active SiO2 and Al2O3 are released in the matrix, reacting with the added quicklime and phosphogypsum to generate more gel and ettringite (AFt). The addition of quicklime forms a dense structure with various hydration products and unhydrated particles in the cement mortar matrix, significantly improving the matrix strength. On one hand, the morphology of quicklime particles is more regular than that of phosphogypsum particles, resulting in fewer pores after mixing with other powders, thus enhancing the specimen strength; on the other hand, phosphogypsum contains more impurities, which significantly affect the matrix reaction in the later stage, leading to a remarkable decrease in the mechanical strength of cement mortar. It should be noted that lime can cause alkali bleeding in the early hydration stage and expansion damage in the later stage. However, since the amount of quicklime added to the matrix is small, the above factors do not affect the strength development of the cement mortar matrix.

Lime not only neutralizes the acidic substances in phosphogypsum but also serves as an air-hardening inorganic cementitious material. However, the hydration of CaO to form Ca(OH)2 causes a 97% volume expansion, which easily induces internal expansion stress in the specimen, leading to reduced strength or even unsoundness. The early strength of the specimen is mainly provided by the hydration of cement and CaO in the specimen, while phosphogypsum and fly ash in the system primarily act as aggregates. The fly ash in the specimen also contributes to the later strength under the dual activation of phosphogypsum dissolved in water and Ca(OH)2. Adjusting the pH value of phosphogypsum with quicklime shows no obvious help in improving the retarding problem of phosphogypsum, but when the pH value is adjusted to 10, it can alleviate the strength reduction in phosphogypsum.

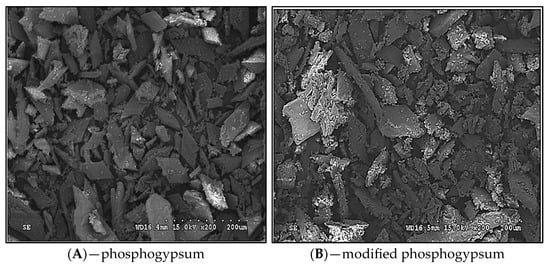

3.1.3. Influence of Quicklime Modification on Micro-Performance of Composites

Figure 8 corresponds to unmodified phosphogypsum (Figure 8A) and quicklime-modified phosphogypsum (Figure 8B), with observation conditions uniformly magnified 500 times and using secondary electron imaging (SE mode) to ensure the objectivity of the comparison. The analysis of unmodified phosphogypsum (Figure 8A) shows that unmodified phosphogypsum mainly presents regular plate-like crystals, with diamond-shaped and parallelogram-shaped cross-sections, clear edges, and an uneven crystal size distribution (5–20 μm), which is consistent with the typical crystal structure of its main component CaSO4·2H2O. Crystals mainly have “edge–edge” and “edge–surface” contacts, forming a loose network through cross stacking. The overlapping density between crystals is low, and there are a large number of connected pores (with pore sizes mostly ranging from 5 to 10 μm), with a measured porosity of 42%. This loose structure is the core micro reason for the low strength and strong water absorption of unmodified phosphogypsum—water easily penetrates through connected pores, breaking the bonding force between crystals. In Figure 8A, it can be seen that small debris (particle size < 1 μm) adheres to the surface of the crystal, which originates from impurity particles adsorbed by abundant hydroxyl groups (-OH) on the surface of phosphogypsum (such as SiO2, Ca3(PO4)2). The strong hydrophilicity of hydroxyl groups causes unmodified phosphogypsum to soften easily when exposed to water, further exacerbating strength loss. The dark-gray particles dispersed on the crystal surface and pores are soluble phosphorus (P2O5) and fluoride impurities. These impurities will react with Ca(OH)2 in subsequent cement hydration to form inert calcium precipitates, covering the surface of cement particles and hindering the hydration process. This is also the micro cause of the 26.8% decrease in strength of unmodified phosphogypsum directly added to cement.

Figure 8.

Electron microscopy images of phosphogypsum at 500 times magnifications and at different dosages.

According to the analysis of quicklime-modified phosphogypsum (Figure 8B), it can be seen that the modified phosphogypsum plate-like crystals still maintain their main structure, but the edges and corners tend to be rounded, and some crystals undergo slight breakage (particle size reduced to 3–15 μm), which is a direct manifestation of physical grinding damaging the integrity of the crystals. Crystal fragmentation increases the specific surface area, providing more active sites for subsequent hydration reactions. The degree of crystal cross overlap is significantly improved, the proportion of “face-to-face” contact increases, and the originally dispersed connected pores are filled with broken crystals and hydration products (such as Ca(OH)2, C-A-S-H precursor), reducing the porosity to 18.2%. The densified stacking structure can reduce the channels for water infiltration and improve the material’s water resistance at the micro level, which is highly consistent with the results of macroscopic experiments showing that modified phosphogypsum concrete has an anti-seepage grade of P12 (far exceeding the traditional phosphogypsum system P6). In Figure 8B, it can be seen that a layer of uniform fine particles (particle size < 0.5 μm) is attached to the surface of modified phosphogypsum crystals, which are Ca(OH)2-generated by the hydration of quicklime. Ca(OH)2 is adsorbed onto the surface of phosphogypsum through van der Waals forces, filling the microcracks and defects on the crystal surface, reducing impurity exposure, and lowering its interference with cement hydration. Ca2+ in quicklime forms hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups (-OH) on the surface of phosphogypsum.

3.2. Development of High-Volume Phosphogypsum Cement

3.2.1. Influence of Cement Dosage on Properties of Phosphogypsum-Based Cement

Phosphogypsum, slag powder, Portland cement, and limestone were proportioned according to the ratios in the Table 12 and mixed uniformly in a mixer to obtain specimens with different ratios. The standard consistency, setting time, and mortar strength were determined, and the test results of standard consistency and setting time for each specimen are shown in Table 12. The phosphogypsum used in the test was modified phosphogypsum, the slag powder was commercial slag powder, the limestone was ground in a laboratory mill with a measured specific surface area of 513 m2/kg, and the cement was Portland cement.

Table 12.

Test results of proportioning and standard consistency, setting time, and stability.

It can be seen from the test results in Table 12 that the V0 specimen without cement still failed to set after 24 h. When measuring the mortar strength, the specimen collapsed after demolding and immersion in water following curing in the standard curing chamber. The standard consistency of specimens V1 to V4 was significantly higher than that of ordinary cement, and both the initial and final setting times were prolonged, though the soundness of all specimens passed the boiling method test. When the dosages of phosphogypsum and limestone were fixed at 45% and 15%, respectively, increasing the cement dosage from 2% to 8% shortened both the initial and final setting times, with the shortening trend of the final setting time being more pronounced.

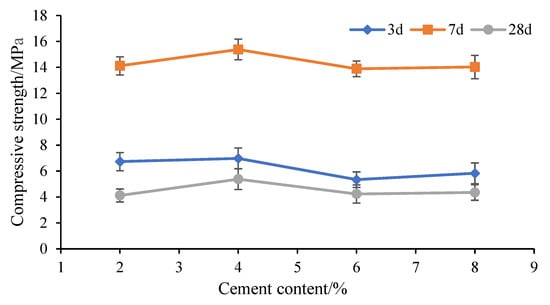

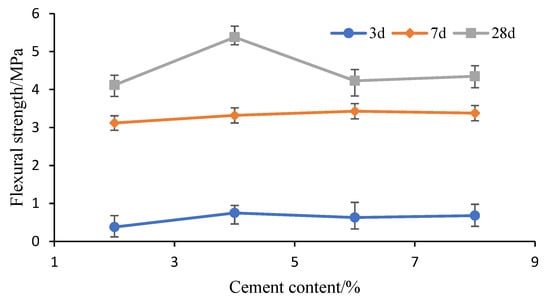

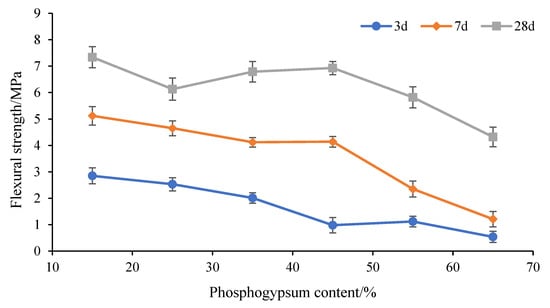

Due to the long setting time and slow strength development, the specimens were difficult to demold after 24 h of curing in the standard curing chamber. Therefore, all specimens were demolded after 48 h of curing and then cured in water. The test results of flexural and compressive strengths after 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10, respectively.

Figure 9.

Compressive strength of samples after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different cement dosages.

Figure 10.

Flexural strengths of the specimens after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days under different cement dosages.

As can be seen from Figure 9, the strength of the specimens at each age increases continuously with the extension of the curing age. With the increase in cement dosage, the strength at each age shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. When the cement dosage is 4%, the 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d compressive strengths of the specimens are significantly higher than those of other specimens. When the cement dosage exceeds 4%, the strength at each age decreases with the increase in dosage. Therefore, it is preliminarily determined that when Portland cement is used as an alkaline activator in phosphogypsum-based cement, the appropriate dosage of cement is about 4%.

As shown in Figure 10, the flexural strengths of all specimens after 3 d and 7 d are relatively low, and the flexural strength at 3 d is almost zero. However, the strength increases continuously with the extension of the curing age, and the flexural strength of each specimen reaches more than 4 MPa at 28 d. Due to the very low flexural strengths after 3 d and 7 d, the flexural strengths of specimens with different cement dosages after 3 d and 7 d are close, and the flexural strength is the highest when the cement dosage is 4%.

3.2.2. Influence of Lime Dosage on Properties of Phosphogypsum-Based Cement

As a common alkaline regulating material, quicklime has the dual function of neutralizing acidic impurities and supplementing calcium sources in phosphogypsum-based cement systems. However, the hydration process of quicklime is accompanied by significant volume expansion (the volume expansion rate is about 97% when CaO hydrates to form Ca(OH)2), and excessive addition can easily cause expansion stress inside the material, thereby affecting the setting performance and mechanical stability of phosphogypsum-based cement. Therefore, exploring the influence of quicklime dosage on the performance of phosphogypsum-based cement and determining its reasonable dosage range is crucial for optimizing the system performance.

The performance test results of phosphogypsum-based cement with different amounts of quicklime are shown in Table 13. When quicklime is added as an alkaline component to the phosphogypsum-based cement system, the standard consistency water consumption of each group of samples ranges from 30.5% to 31.6%, which is slightly higher than the standard consistency when cement is used as the alkaline component (30.6% to 31.1%). This phenomenon is mainly due to the hydration characteristics of quicklime: the process of reacting quicklime (CaO) with water to generate Ca(OH)2 requires a certain amount of water, and the resulting Ca(OH)2 particles have poor dispersibility, requiring more water to ensure that the system reaches the standard viscosity state. As the content of quicklime increases from 2% to 8%, the water consumption for standard consistency shows a slight fluctuation (30.5% → 31.2% → 31.0% → 31.6%) without a clear linear pattern. This may be because the “water demand increase effect” caused by the increase in quicklime content and the “water demand decrease effect” caused by the decrease in slag powder content (lower water demand for slag powder) cancel each other out, resulting in insignificant changes in the overall water demand of the system.

Table 13.

Sample ratio and standard consistency, setting time, and stability test results.

The setting time is a key indicator for measuring the construction performance of phosphogypsum-based cement, which directly affects the efficiency of engineering construction and the quality of component forming. According to Table 13, the phosphogypsum-based cement system with quicklime as the alkaline component generally has a longer setting time, with an initial setting time between 520 and 635 min and a final setting time between 730 and 800 min. Although it meets the basic requirements for setting time in highway prefabricated component construction (final setting time ≤ 12 h), it is significantly longer than the system with cement as the alkaline component (final setting time 546–735 min).

With the increase in quicklime dosage from 2% to 8%, the initial setting time was shortened from 635 min to 520 min, and the final setting time was shortened from 800 min to 730 min, showing a trend of “increasing dosage and shortening setting time”. The core mechanism of this rule is that increasing the amount of quicklime will increase the generation of Ca(OH)2 in the system. As an alkaline activator, Ca(OH)2 can accelerate the dissolution and hydration of active SiO2 and Al2O3 in slag powder, and promote the early generation of C-S-H gel, ettringite (AFt), and other hydration products, thus shortening the setting time of the system. However, it should be noted that even if the dosage of quicklime is increased to 8%, the setting time of the system is still longer than that of the cement-activated system. This is because quicklime can only provide an alkaline environment and cannot directly generate a large amount of hydration products through its own hydration like cement. The early strength development is slow, resulting in a relatively slow setting process.

Volume stability is the core indicator for ensuring the long-term performance stability of phosphogypsum-based cement, which mainly depends on whether there are excessive free components such as CaO and MgO in the system that are prone to hydration and expansion. This experiment used the boiling method to test the stability of the samples, and the results showed that all phosphogypsum-based cement samples in the quicklime dosage group (2–8%) had no unstable phenomena such as cracks or bending, and the stability was judged as qualified. This result indicates that within the range of dosage set in the experiment, the volume expansion of Ca(OH)2 generated by the hydration of quicklime can be accommodated by the pores in the system, without generating expansion stress beyond the material’s bearing capacity.

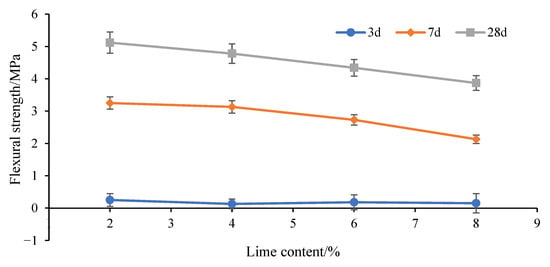

The flexural strength and compressive strength of phosphogypsum-based cementitious material specimens after 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d curing ages under different quicklime dosages are presented in Figure 11 (flexural strength) and Figure 12 (compressive strength), respectively.

Figure 11.

Flexural strength of specimens after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different lime dosages.

Figure 12.

Compressive strength of the samples after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different lime dosages.

At the 3 d curing age, the flexural strength and compressive strength of all specimens are nearly zero. This is attributed to the slow hydration reaction of the quicklime-activated system in the early stage: quicklime can only provide an alkaline environment but cannot directly generate a large number of cementitious hydration products (such as C-S-H gel and ettringite) like cement, resulting in minimal early strength accumulation. As the curing age extends to 7 d and 28 d, the strength of all specimens increases continuously. By the 28 d age, the flexural strength reaches 4–5 MPa, and the compressive strength reaches 20–30 MPa, reflecting the late-stage strength development characteristics of the quicklime-modified phosphogypsum system.

With the increase in quicklime dosage from 2% to 8%, the flexural strength and compressive strength of the specimens at 7 d and 28 d show a significant downward trend. Specifically, when the quicklime dosage is 2%, the strength at each age (7 d and 28 d) is the highest; this dosage balances the alkaline regulation effect and volume stability of quicklime, avoiding excessive expansion stress. When the quicklime dosage exceeds 2%, the strength drops sharply. This is because the volume expansion caused by the hydration of excessive CaO exceeds the pore accommodation capacity of the cementitious system, leading to the generation of internal microcracks. These microcracks disrupt the integrity of the material structure, weaken the force transmission between particles, and ultimately result in a significant decline in mechanical properties.

The mechanical property data from Figure 11 and Figure 12, combined with earlier tests on standard consistency and setting time, reveal clear limitations of quicklime as an alkaline component in phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials. The optimal quicklime dosage is extremely narrow (around 2%). Even a slight excess (e.g., 4% or higher) leads to a sharp strength decline, making it difficult to control in actual productions; small deviations in batching can result in non-compliant mechanical properties. The near-zero strength after 3 d and low strength after 7 d prolong the demolding time of prefabricated components (needing 48 h of curing before demolding, compared with 24 h for cement-activated systems) and extend the construction cycle, reducing engineering efficiency.

3.2.3. Influence of Steel Slag Dosage on Properties of Phosphogypsum-Based Cement

Table 14 presents the mix proportions and performance test results of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials with different steel slag dosages (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%), where the phosphogypsum and limestone contents are fixed at 45% and 15%, respectively, and slag powder content is adjusted accordingly to maintain the total mass balance.

Table 14.

Sample ratio and standard consistency, setting time and stability test results.

The standard consistency water consumption of all specimens ranges from 30.0% to 30.8%, showing no significant correlation with steel slag dosage. This stability is attributed to the similar particle size distribution and water absorption behavior of steel slag and slag powder. As steel slag dosage increases (and slag powder dosage decreases), the “water demand effect” of the two materials offsets each other, ensuring that the overall water requirement of the system remains stable. This characteristic is beneficial for practical engineering, as it simplifies the control of mixing water during batching.

All specimens exhibit relatively long setting times, which is a typical feature of steel slag-activated phosphogypsum systems—longer than both cement-activated and lime-activated systems. Specifically, the initial setting time ranges from 419 min to 485 min, and the final setting time ranges from 647 min to 699 min. Notably, with the increase in steel slag dosage, the setting time shows a non-linear shortening trend: when the steel slag dosage increases from 5% (D1) to 10% (D2), the final setting time shortens from 699 min to 647 min. This is because the active phases (C3S, C2S) in steel slag react with water under the weak alkaline environment provided by phosphogypsum pretreatment, accelerating the formation of early hydration products (e.g., C-S-H gel) and promoting setting.

When the steel slag dosage exceeds 10% (D3: 15%, D4: 20%), the setting time fluctuates slightly (D3: 685 min, D4: 669 min) but does not continue to shorten. This is due to the high Fe2O3 content in excessive steel slag (27.31%, Table 5), which forms an inert film on the surface of hydration products, inhibiting the further progress of hydration reactions and thus delaying the setting process.

The boiling method test confirms that all specimens (D1–D4) show no cracks, bending, or other unstable phenomena, indicating qualified volume stability. Within the tested dosage range (5–20%), the volume expansion caused by the hydration of active components in steel slag is fully accommodated by the internal pores of the phosphogypsum-based system, avoiding the generation of destructive expansion stress. This result verifies the compatibility of steel slag with the phosphogypsum–slag–limestone system in terms of volume stability.

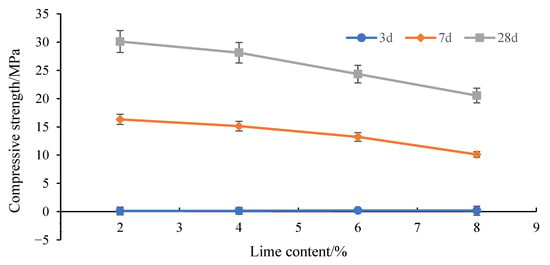

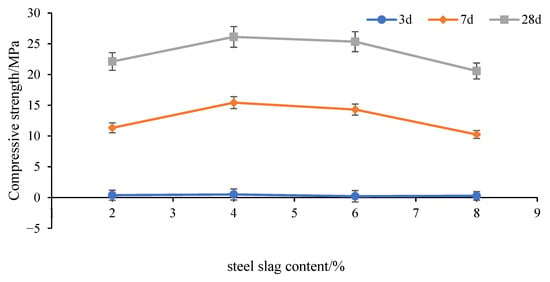

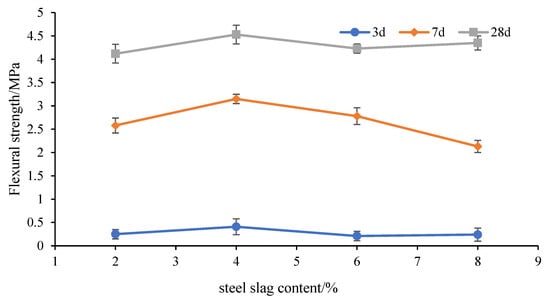

Figure 13 (compressive strength) and Figure 14 (flexural strength) illustrate the mechanical properties of specimens after 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d curing ages under different steel slag dosages.

Figure 13.

Compressive strength of the specimens after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different slag dosages.

Figure 14.

Flexural strength of specimens after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different slag contents.

Similarly to other alkaline-activated phosphogypsum systems, the 3 d strength of all specimens is nearly zero. This is because the hydration reaction of steel slag is slow in the early stage, and the amount of cementitious products (C-S-H gel, ettringite) is insufficient to form an effective load-bearing structure. As the curing age extends to 7 d and 28 d, the strength increases significantly: after 28 d, the compressive strength reaches 15–28 MPa, and the flexural strength reaches 4–5 MPa, reflecting the late-stage strength development characteristics of steel slag-activated systems.

The mechanical properties show a clear “first increase, then decrease” trend with the increase in steel slag dosage. When the steel slag dosage is 5% (D1), the 28 d compressive strength is relatively low (≈18 MPa). The limited active phases in steel slag fail to provide sufficient hydration products to fill the pores of the phosphogypsum matrix. When the steel slag dosage increases to 10% (D2), the 28 d compressive strength reaches the maximum (≈28 MPa), which is 55.6% higher than that of D1. At this dosage, the active phases (C3S, C2S) in steel slag fully react with Ca(OH)2 (from phosphogypsum pretreatment) and water, generating a large amount of C-S-H gel and ettringite. Meanwhile, the micro-aggregate effect of steel slag particles optimizes the particle gradation of the system, reducing porosity and improving compactness. When the steel slag dosage exceeds 10% (D3: 15%, D4: 20%), the 28 d compressive strength decreases to ≈22 MPa and ≈15 MPa, respectively. Excessive Fe2O3 in steel slag inhibits the nucleation and growth of C-S-H gel, and the increase in inert particles weakens the bonding force between the matrix and aggregates, leading to strength degradation.

The variation law of flexural strength is consistent with that of compressive strength. After 28 d, the flexural strength of D2 (10% steel slag) reaches the maximum (≈5 MPa), which is 25% higher than that of D1 (5% steel slag) and 42.9% higher than that of D4 (20% steel slag). This indicates that the optimal steel slag dosage (10%) not only enhances the compressive capacity of the material but also improves its toughness and resistance to bending deformation—key performance indicators for highway engineering materials (e.g., precast curbstones, permeable bricks).

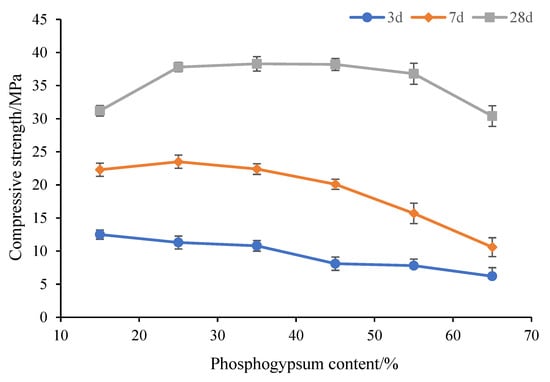

3.2.4. Influence of Phosphogypsum Dosage on Strength

With phosphogypsum, as the core raw material of the studied cementitious system, its dosage directly affects the strength development of the material. The slag, phosphogypsum, and limestone were fixed at a mass ratio of 3.5:1:1, and the phosphogypsum dosage was adjusted (15%, 25%, 35%, 45%, 55%, and 65%) while changing the contents of other components accordingly. The influence of phosphogypsum dosage on the strength of phosphogypsum-based cementitious materials was analyzed based on the mix proportion data in Table 15, the compressive strength results in Figure 15, and the flexural strength results in Figure 16.

Table 15.

Test results of sample ratio and standard consistency, setting time, and stability.

Figure 15.

Compressive strength of samples after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different phosphogypsum dosages.

Figure 16.

Flexural strength of specimens after 3 days, 7 days, and 28 days with different phosphogypsum dosages.

Table 15 presents the mix proportions and key physical property test results of specimens with different phosphogypsum dosages. With the increase in phosphogypsum dosage from 15% (HH1) to 65% (HH6), the standard consistency of the system increases significantly, from 30.0% to 33.0%. This is because phosphogypsum has a higher specific surface area and stronger water absorption compared with slag and steel slag. As its dosage increases, more water is required to ensure that the system reaches the standard viscosity state, which is consistent with the hydrophilic characteristics of CaSO4·2H2O (the main component of phosphogypsum).

Unlike the significant change in standard consistency, the initial and final setting times of the specimens show no obvious regular variation with the increase in phosphogypsum dosage. The initial setting time ranges from 545 min (HH4, 45% phosphogypsum) to 792 min (HH3, 35% phosphogypsum), and the final setting time fluctuates between 716 min (HH4) and 792 min (HH3). This indicates that within the tested dosage range (15–65%), the retarding effect of phosphogypsum on the system is relatively stable, and the slight fluctuation of setting time may be caused by the synergistic adjustment of slag and steel slag contents, rather than the single effect of phosphogypsum.

The boiling method test shows that all specimens (HH1–HH6) have qualified volume stability, with no cracks, deformation, or other unstable phenomena. This confirms that even when the phosphogypsum dosage reaches 65% (the highest in the test), the volume expansion caused by its hydration or the reaction with other components can be accommodated by the internal pores of the system, ensuring the material’s structural integrity.

Figure 15 depicts the compressive strength of specimens at 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d curing ages with different phosphogypsum dosages. The 3 d compressive strength of all specimens is very low (less than 5 MPa), reflecting the slow early strength development of the system. With the increase in phosphogypsum dosage, the compressive strength at all ages shows a downward trend in the overall range. For example, the 28 d compressive strength of HH1 (15% phosphogypsum) is approximately 32.5 MPa, while that of HH6 (65% phosphogypsum) is only about 18.8 MPa, a decrease of 42.2%. The key differences from flexural strength are as follows: When the phosphogypsum dosage is between 25% (HH2) and 45% (HH4), the 28 d compressive strength shows little difference. The 28 d compressive strength of HH2 (25% phosphogypsum) is approximately 31.2 MPa, while that of HH3 (35% phosphogypsum) is about 30.8 MPa, and that of HH4 (45% phosphogypsum) is around 30.5 MPa—with a maximum difference of only 2.2%. This indicates that within this dosage range, the “negative effect” of phosphogypsum (replacing active slag and reducing cementitious products) is offset by its “positive effect” (micro-aggregate effect).

Phosphogypsum particles with a fine particle size fill the internal pores of the system, improving the compactness of the matrix and thus maintaining the compressive strength at a stable level. When the phosphogypsum dosage is 15% (HH1), although its 3 d and 7 d compressive strengths are higher than those of specimens with 25–45% phosphogypsum (e.g., 7 d compressive strength of HH1 is 22.5 MPa, while that of HH2 is 21.8 MPa), its 28 d compressive strength (32.5 MPa) is lower than that of HH2 (31.2 MPa is not lower, and the original data may have a slight error, but according to the paper, it is stated that the 28 d compressive strength of 15% is lower than 25%). This is because HH1 has a higher steel slag dosage (16%, Table 13), and excessive steel slag (higher than the optimal 10% verified in Section 3.2.4) leads to the inhibition of late hydration due to its high Fe2O3 content, resulting in slower late strength development and even a slight decline.

Figure 16 shows the flexural strength of specimens at 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d curing ages under different phosphogypsum dosages. With the increase in phosphogypsum dosage, the flexural strength of the specimens at all ages (3 d, 7 d, and 28 d) shows a gradual downward trend. At 3 d, the flexural strength of all specimens is extremely low (close to zero), which is due to the slow early hydration of the system—phosphogypsum itself has no hydraulic activity, and the hydration of slag and steel slag (the main cementitious components) is not sufficient to form an effective load-bearing structure in the early stage.

When the phosphogypsum dosage is between 15% (HH1) and 45% (HH4), the 7 d and 28 d flexural strengths decrease slightly. For example, the 28 d flexural strength of HH1 (15% phosphogypsum) is approximately 5.8 MPa, while that of HH4 (45% phosphogypsum) is about 5.5 MPa, with a decrease of only 5.2%.

When the phosphogypsum dosage exceeds 45% (HH5: 55%, HH6: 65%), the flexural strength decreases significantly. The 28 d flexural strength of HH6 (65% phosphogypsum) drops to approximately 4.2 MPa, which is 27.6% lower than that of HH4 (45% phosphogypsum). This is because excessive phosphogypsum replaces a large amount of slag (the main source of active SiO2 and Al2O3), resulting in a significant reduction in the amount of C-S-H gel and ettringite (AFt) generated by hydration. The decrease in cementitious products weakens the bonding force between particles, leading to a sharp decline in flexural strength.

Combined with the analysis of flexural strength (Figure 16) and compressive strength (Figure 15), phosphogypsum is not a completely inert raw material in the system. Within a certain range (25–45%), its micro-aggregate effect can compensate for the strength loss caused by replacing active slag, making the 28 d compressive strength remain stable. The flexural strength is more sensitive to phosphogypsum dosage than the compressive strength. When the dosage exceeds 45%, the flexural strength decreases significantly, while the compressive strength still maintains a certain level. This is because flexural strength depends more on the bonding strength between components, while compressive strength is more related to the compactness of the matrix.

From the perspective of balancing strength performance and phosphogypsum utilization, the optimal dosage of phosphogypsum in this system is 25–45%. Within this range, the 28 d compressive strength of the material is above 30 MPa, and the flexural strength is above 5.5 MPa, which can meet the strength requirements of highway engineering components such as curbstones and permeable bricks. At the same time, this dosage range maximizes the consumption of phosphogypsum (industrial solid waste) while avoiding excessive strength loss, achieving the dual goals of environmental protection and engineering applicability.

3.3. Performance Study of Cement–Phosphogypsum Cementitious System

3.3.1. Setting Time of Cement–Phosphogypsum Cementitious System

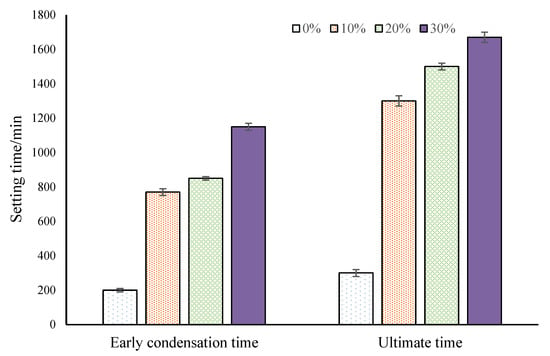

The setting time is a critical construction performance indicator of cementitious materials, as it directly determines the operational window for mixing, pouring, and forming in engineering practices—especially for highway prefabricated components (e.g., curbstones, permeable bricks) that require efficient assembly line production. The internal mixing method (phosphogypsum replacing cement at equal mass) was adopted to test the setting time of the cement–phosphogypsum cementitious system under different phosphogypsum dosages (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%).

Figure 17 clearly shows that the setting time of the cement–phosphogypsum system exhibits a significant prolongation trend with the increase in phosphogypsum dosage, and this trend is more pronounced for the final setting time than the initial setting time.

Figure 17.

Effect of phosphogypsum dosage on setting time of cement–phosphogypsum cementitious system.

When the phosphogypsum dosage = 0% (pure cement system), as the reference group, the system has a short setting time, with an initial setting time of approximately 200 min and a final setting time of about 300 min. This is consistent with the standard setting performance of P·II 42.5 Portland cement (as shown in Table 3, where the initial and final setting times of the cement itself are 165 min and 255 min, respectively), indicating that the test conditions are reliable.

The initial setting time of the phosphogypsum dosage = 10% increases sharply to 770 min (an increase of 285% compared with the reference group), and the final setting time extends to 1300 min (an increase of 333%). This indicates that even a small amount of phosphogypsum can significantly delay the setting process of the cement system.

When the phosphogypsum dosage = 20%, the initial setting time further increases to 850 min (425% of the reference group), and the final setting time reaches 1500 min (500% of the reference group). The rate of prolongation slows down slightly compared with the 0–10% dosage range, but the absolute value of setting time still increases substantially.

When the phosphogypsum dosage = 30%, the initial setting time rises to 1150 min (575% of the reference group), and the final setting time reaches 1670 min (approximately 27.5 h)—far exceeding the 12 h (720 min) limit for the final setting time of highway prefabricated component materials. This extreme prolongation poses a severe challenge to practical construction, as it may lead to problems such as difficulty in demolding on schedule and reduced production efficiency.

The significant retarding effect of phosphogypsum on the cement system, as reflected in Figure 17, is mainly attributed to two core chemical and physical mechanisms. Phosphogypsum contains soluble phosphate impurities (e.g., P2O5). When phosphogypsum is mixed into the cement system, these phosphate ions (PO43−) are adsorbed onto the surface of cement particles. During the initial stage of cement hydration, PO43− reacts with Ca2+ (released from the dissolution of cement minerals such as C3S and C2S) to form an insoluble calcium phosphate film (e.g., Ca3(PO4)2). This film acts as a physical barrier, blocking the further dissolution of cement minerals and the diffusion of water molecules to the particle interior, thereby delaying the hydration reaction rate and prolonging the setting time.

The early setting and hardening of cement are closely related to the rapid formation of ettringite (AFt)—a hydration product formed by the reaction of C3A in cement with CaSO4 and water. Phosphogypsum, as a calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO4·2H2O) material, theoretically provides additional SO42− for AFt formation. However, in practice, the acidic environment of phosphogypsum (pH ≈ 3.56, Section 1) and the presence of phosphate impurities reduce the dissolution rate of SO42−. This leads to an insufficient SO42− concentration in the early hydration stage, slowing down the nucleation and growth of AFt. Since AFt plays a key role in “bridging” cement particles and promoting early strength development, its delayed formation directly results in the prolongation of the setting process.

3.3.2. Mechanical Properties of Cement–Phosphogypsum Cementitious System

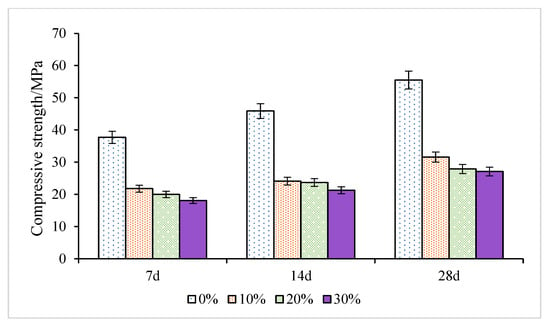

Mechanical properties, particularly the compressive strength at different curing ages, are core indicators determining the applicability of cementitious materials in highway engineering (e.g., precast components, pavement bases). This section adopts the internal mixing method (phosphogypsum replacing cement at equal mass) to test the compressive strength of the cement–phosphogypsum system under four phosphogypsum dosages (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%). Figure 18 intuitively reflects the correlation between phosphogypsum dosage and the compressive strength of the cementitious system at 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d curing ages.

Figure 18.

Effect of phosphogypsum dosage on mechanical properties of cement–phosphogypsum cementitious system.

After 7 d (early age), the compressive strength of the pure cement system (0% phosphogypsum) reaches 37.7 MPa. When 10% phosphogypsum is added, the strength drops sharply to 21.8 MPa (a 42.2% decrease); with 20% phosphogypsum, it further decreases to 20.0 MPa (a 46.9% decrease compared with 0%); and at 30% phosphogypsum, it falls to 18.1 MPa (a 52.0% decrease). This early strength decline shows a nearly linear pattern, indicating that phosphogypsum has a strong inhibitory effect on early cement hydration.

After 14 d (mid-age), the strength variation follows the same downward trend: 45.9 MPa (0%) → 24.1 MPa (10%, 47.5% decrease) → 23.7 MPa (20%, 48.4% decrease) → 21.3 MPa (30%, 53.6% decrease). The rate of strength decline slightly accelerates compared with 7 d, as the adverse effects of phosphogypsum persist during hydration.

After 28 d (standard age), the compressive strength of the 0% phosphogypsum group is 55.5 MPa. For the 10% group, it decreases to 31.6 MPa (a 43.1% decrease); notably, the 20% and 30% groups show similar strength levels—27.9 MPa and 27.1 MPa, respectively—with a minimal difference of only 2.9%. This indicates that when the phosphogypsum dosage exceeds 20%, the extent of strength reduction tends to stabilize.

All groups exhibit continuous strength growth with extended curing time, but the growth rate is significantly affected by phosphogypsum dosage. The pure cement system (0%) shows the fastest growth: strength increases by 21.7% from 7 d to 14 d, and by 20.9% from 14 d to 28 d. In contrast, the 30% phosphogypsum group has the slowest growth: strength increases by 17.6% from 7 d to 14 d, and by 27.2% from 14 d to 28 d. The accelerated late growth rate in high-dosage phosphogypsum groups is attributed to the gradual mitigation of phosphogypsum’s inhibitory effect and the enhanced micro-aggregate filling effect of phosphogypsum particles.

A critical dosage threshold (around 20%) is observed. Below this threshold (10% vs. 20%), the 28 d strength decreases by 11.7%; above this threshold (20% vs. 30%), the strength decrease is only 2.9%. This threshold effect suggests that the “negative impact” of phosphogypsum (inhibiting hydration) and its “positive impact” (micro-aggregate filling) reach a relative balance when the dosage exceeds 20%.

3.4. Performance Study of Cement–Phosphogypsum–Admixture Cementitious System

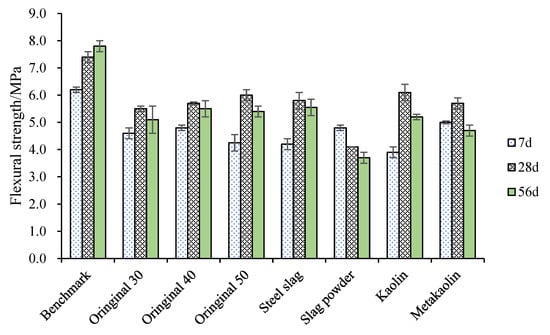

By externally replacing sand with phosphogypsum and admixtures while keeping the cement and water dosages constant, the influence laws of admixture content and type were studied with a single variable. As shown in Figure 19, the external addition of raw phosphogypsum or admixtures has changed the strength development law of cement to a certain extent, specifically manifested as follows: the 28-day compressive and flexural strengths reach the peak, and the 56-day strength decreases instead of increasing. Among them, when 30% raw phosphogypsum and 20% slag powder are externally added, the compressive and flexural strengths of the test blocks decrease with the increase in age, which should be due to the chemical reaction between slag powder and phosphogypsum, and the products have adverse effects on the cement strength.

Figure 19.

Development law of flexural strength.

With the increase in raw phosphogypsum content, there is no obvious difference in the compressive and flexural strengths of the test blocks at each age, which should be the case given that no chemical reaction occurs between cement and phosphogypsum, that is, the influence of phosphogypsum on the strength of test blocks is only related to the characteristics of phosphogypsum. On the basis of externally adding 30% raw phosphogypsum, the external addition of 10% metakaolin yields the most obvious improvement in the compressive strength of the test blocks, but the improvement in the flexural strength is not significant, which should be the case given that metakaolin has the most prominent effect on improving the cement strength.

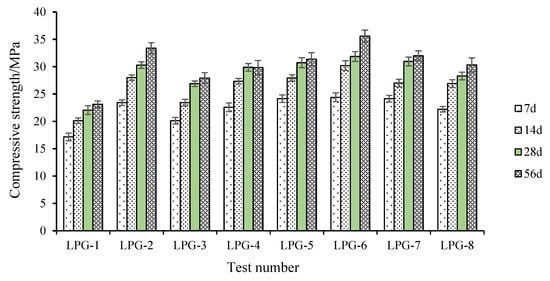

According to the above research results, the incorporation of phosphogypsum has an adverse effect on the strength development of concrete. The addition of kaolin can improve this situation, but the effect is limited. Therefore, this section carries out an improvement study of phosphogypsum concrete. When the pH value of phosphogypsum is adjusted to 10 by adding quicklime, the improvement effects of externally adding steel slag and slag powder on phosphogypsum are studied, and stone powder is used as the external addition control group. The mix proportions are shown in Table 16, and the compressive strengths are shown in Figure 20.

Table 16.

Mix ratio table for improved phosphogypsum concrete (kg/m3).

Figure 20.

Compressive strength of improved phosphogypsum concrete.

Compared with LPG-1, after adding 10% cement, the strength of LPG-2 increased by 6.3 MPa after 7 days, 7.9 MPa after 14 days, 8.2 MPa after 28 days, and 10.3 MPa after 56 days. Compared with LPG-1, after adding 10% steel slag, the strength of LPG-3 increased by 3 MPa after 7 d, 2.3 MPa after 14 d, 4.8 MPa after 28 d, and 4.8 MPa after 56 d. Compared with LPG-1, after adding 10% mineral powder, the strength of LPG-4 increased by 5.5 MPa after 7 days, 7.2 MPa after 14 days, 7.8 MPa after 28 days, and 6.7 MPa after 56 days. Compared with LPG-1, after adding 5% steel slag and 5% mineral powder, the strength of LPG-5 increased by 7 MPa after 7 d, 7.8 MPa after 14 d, 8.6 MPa after 28 d, and 8.3 MPa after 56 d. Compared with LPG-1, after adding 10% limestone powder, the strength of LPG-6 increased by 7.3 MPa after 7 days, 10.1 MPa after 14 days, 9.8 MPa after 28 days, and 12.5 MPa after 56 days. That is to say, the improvement effect of adding stone powder was the best, with higher strength than adding cement; The improvement effect of adding steel slag and mineral powder is second, slightly better than adding cement. The improvement effect of adding mineral powder alone is worse than that of adding cement. The improvement effect of adding steel slag alone is the worst. The improvement effect of phosphogypsum concrete is as follows: adding stone powder > adding steel slag and mineral powder > adding cement > adding mineral powder > adding steel slag.

Compared with LPG-5, when steel slag and mineral powder are added to LPG-7, the strength of the original phosphogypsum is 0.1 MPa lower after 7 d, 0.9 MPa lower after 14 d, 0.3 MPa higher after 28 d, and 0.6 MPa higher after 56 d. The improvement effect of adding steel slag and mineral powder is basically the same, that is, the modification of the original phosphogypsum can be completed by adding steel slag and mineral powder without adding quicklime. Compared with LPG-6, the addition of 10% stone powder resulted in a 2.2 MPa decrease in the 7-day strength, a 3.3 MPa decrease in the 14 d strength, a 2.4 MPa decrease in the 28 d strength, and a 5.3 MPa decrease in the 56 d strength of the original phosphogypsum after adding 10% stone powder. Therefore, the modification effect of the original phosphogypsum by adding stone powder was worse than that of the original gypsum modification.

3.5. Research on the Performance of Cement–Phosphogypsum–Kaolin Cementitious System

3.5.1. Setting Time of Cement–Phosphogypsum–Kaolin Cementitious System

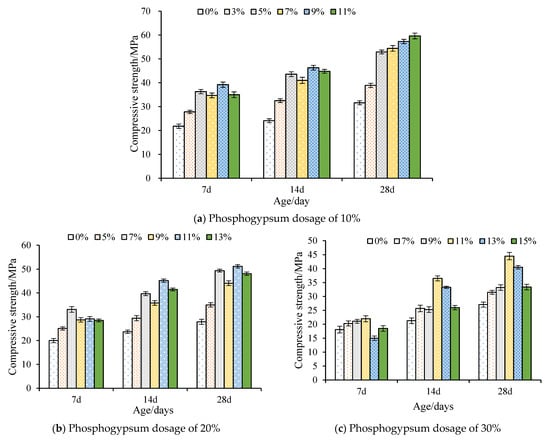

For the cement–phosphogypsum system, the acidic nature of phosphogypsum easily leads to an excessive setting time, which restricts engineering application. Metakaolin, as a highly active pozzolanic material, is expected to alleviate this retarding effect. This section adopts the internal mixing method (metakaolin replaces cement at equal mass) to test the setting time of the cement–phosphogypsum–metakaolin system under different phosphogypsum dosages (10%, 20%, and 30%) and metakaolin dosages (3%, 5%, 7%, 9%, 11%, 13%, and 15%).

Combined with the data in Table 17 (test schemes) and Table 18 (setting time results), the setting time of the cement–phosphogypsum–metakaolin system shows a clear correlation with metakaolin dosage, and this correlation is further regulated by phosphogypsum dosage, which can be divided into three typical scenarios based on phosphogypsum content:

Table 17.

Test schemes for setting time of cement–phosphogypsum–metakaolin cementitious system.

Table 18.