Abstract

Due to the recent increase in building energy consumption, daylighting technologies such as light ducts are becoming increasingly important. However, conventional light ducts have limitations, such as light loss, uneven illumination, and spectral distortion as the transmission distance increases, restricting the development of a comfortable lighting environment. This study developed technical alternatives for transmission and diffusion parts to overcome these limitations and improve the daylighting performance of light ducts. The performance of these alternatives was verified through testbed experiments. The proposed light duct design minimized light loss through the arrangement of multiple relay lenses in series in the transmission part and improved indoor illuminance uniformity in the diffusion part using a double-reflection structure with upper and lower reflectors. Consequently, for a transmission distance of 20 m, the average illuminance increased by ~27.3% and the uniformity improved by an average of 47.8% compared to a conventional plastic optical fiber (POF)-based light duct. Even under intense summer sunlight conditions, a transmission distance of 30 m showed a high useful daylighting illuminance (UDI) ratio and considerbly reduced glare risk, indicating characteristics favorable for maintaining a comfortable visual environment. Furthermore, the proposed light duct exhibited a spectral distribution similar to that of outdoor sunlight, demonstrating the potential to ensure the continuous spectral characteristics of natural light transmitted indoors. Finally, it also exhibited the potential to maintain its higher daylighting performance even at a transmission distance of 30 m compared to conventional technology.

1. Introduction

Global energy demand has been increasing rapidly every year, and the resulting rise in carbon emissions continues to exacerbate climate change [1,2]. According to the “Global Energy Review 2025” published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), global energy use in 2024 increased by 2.2% compared to that in 2023, reaching 650 EJ [3]. A significant portion of this increase originates from the building sector. As reported in the IEA’s “Energy Efficiency Policy Toolkit 2025”, the building sector, which includes residential and commercial buildings, accounts for ~30% of global energy consumption [4]. In particular, lighting energy use in the U.S. has been rising as efforts to create more comfortable indoor environments are increasing. According to the “Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey 2018” published by the Energy Information Administration, ~25% of energy consumed in commercial buildings is used for lighting purposes [5]. Thus, lighting energy demand in the building sector continues to increase, prompting increased research on various natural lighting and shading systems, such as light ducts [6,7,8,9,10,11], light shelves [12,13,14,15], louvers [16,17,18], and blinds [19,20,21,22]. In the architectural field, the importance of daylighting is being increasingly emphasized not just as a simple energy-saving technology but as a means to improve the health of residents and the resilience of cities, achieving UN Sustainable Development Goals 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities). Specifically, the spectral fidelity of natural light plays a significant role in physiological health and is directly linked to maintaining humans’ circadian rhythms and visual comfort. Among various natural lighting systems, light ducts are representative systems that transmit external natural light indoors by reflecting the light multiple times using highly reflective metal or optical fibers. Their effectiveness has been demonstrated in various studies [6,7,8,9,10,11]. However, conventional light ducts suffer from a rapid decrease in the transmission efficiency due to cumulative reflection losses during multiple reflections. Studies have shown that approximately 50–70% loss occurs when light is transmitted over a distance of ~20 m [23]. Furthermore, the diffusion part is equipped with a component that diffuses natural light entering the interior [24]. We found that conventional systems face difficulty in achieving uniform illuminance.

Therefore, this study aimed at addressing light loss and nonuniform illuminance issues that occur during long-distance light transmission by arranging relay lenses in series in the transmission part and using a double-reflection structure in the diffusion part. We aimed to offer potential solutions that will not only contribute to energy reduction but also to the realization of a human-centered, healthy lighting environment. We developed methods for improving the performance of the transmission and diffusion parts of the proposed light duct. The aim was to verify the applicability and feasibility of the proposed technology by quantitatively comparing its performance with that of conventional technology based on a full-scale testbed.

1.1. Concept of Light Ducts and Literature Review

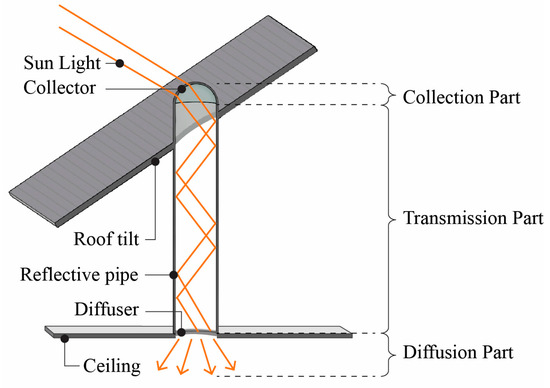

As shown in Figure 1, a light duct is a natural lighting system that collects external sunlight through a highly reflective duct and transmits it to spaces where natural light is limited [25]. Light ducts provide a permanent and intuitive means of transmitting light, and their effectiveness has been demonstrated in previous studies [6,7,8,9,10,11]. A light duct is composed of three main parts: collection, transmission, and diffusion parts, all defined by their functions and installation locations. The collection part collects sunlight typically using polymethylmethacrylate panels due to their high transmittance [26]. The collection part is classified into fixed and tracking types [27], and the tracking type is further classified into program-based and sensor-based systems [28,29,30]. The program-based system calculates the sun’s position using astronomical data. Although this method is susceptible to external environmental changes, it has the advantage of minimizing unnecessary tracking [31]. The sensor-based system tracks the sun’s direction in real time using light sensors. While this method adapts to environmental changes, its positional accuracy is low. The transmission part transmits the collected light to the target point typically through optical fibers or high-reflectance ducts using a multireflection method [32]. Optical fibers are easy to install and suitable for use in narrow spaces; however, in large-scale or long-distance daylighting systems, they generate cumulative optical loss with increasing transmission distances and incur high costs [33]. Optical fibers can be classified into two main types: plastic optical fibers (POFs) and reflective optical fibers. POFs are flexible and easy to install but exhibit high loss rates and low durability. In contrast, reflective optical fibers have high transmission efficiency but exhibit a complex structure and incur high manufacturing costs. Consequently, POFs are primarily used in general architectural light duct systems. Studies have shown that light ducts employing POFs are effective for transmission distances of up to ~20 m, beyond which their efficiency decreases significantly, making them unsuitable for application [6]. High-reflectance ducts can maintain efficiency over long distances using anodized aluminum surfaces and reflective sheets [34]. However, they have drawbacks, such as light loss along curved paths, contamination, and maintenance difficulties. The diffusion part disperses light from the duct’s end into the room using materials with high transmittance and by inducing surface light scattering [24].

Figure 1.

Schematic of a light duct.

Studies have investigated light ducts using various methods and configurations [24,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], as shown in Table 1. However, most studies aimed to improve the daylighting performance by focusing on simple structural aspects and parameters, such as internal reflectance, duct length, and installation location. Research on the transmission part of light ducts has primarily focused on improving the transmission efficiency through multiple reflections. The diffusion part has been explored to a limited extent, with simple structures such as diffusion covers being generally used. On the other hand, while some previous studies proposed lens-based daylight transmission systems, this research presents a new design strategy that simultaneously improves transmission efficiency and illuminance uniformity. This is accomplished by applying relay lenses to the transmission part and introducing a double-reflection structure to the diffusion part. Hence, this study can clearly emphasize its technical contribution compared to previous research in terms of improved daylighting performance and an enhanced indoor light environment.

Table 1.

Studies conducted on light ducts.

1.2. Concept and Structure of a Relay Lens

A relay lens is an optical element that adjusts the direction of light or shifts its position by a certain distance [47]. It can efficiently transmit light even in environments with spatial constraints, making it useful in various systems such as daylighting, lighting, and industrial optics [48]. Relay lenses are essential for delivering light efficiently to a desired location even in narrow spaces or complex structures where it is difficult to transmit light along a straight line. Typically, relay lenses are composed of two or more lenses or lens groups arranged symmetrically and designed to minimize light loss and optical aberrations [49]. This design plays a key role in maintaining the quality of transmitted light by reducing distortions that may occur when light is refracted or reflected multiple times. Furthermore, parameters such as group spacing, focal length, and material properties are optimized according to the design purpose, allowing for the uniform control of light intensity and distribution at a specific distance. Relay lenses are classified into single and double relay lenses depending on their configuration. A single relay lens consists of one lens group and is used to transmit light over a certain distance or adjust light direction. Its simple design makes it suitable for single-stage transmission. Meanwhile, a double relay lens comprises two lens groups, allowing light to be efficiently delivered to the desired location by adjusting the distance between the lens groups. This structure is advantageous for multistage transmission or for transmitting light efficiently over long distances. With the appropriate arrangement of multiple lens groups, uniform illumination distribution can be achieved even over long distances while minimizing light loss.

1.3. Indoor Illuminance Criteria for Improving Indoor Light Environments

To create a comfortable indoor lighting environment, it is essential to ensure sufficient brightness while maintaining a balanced distribution of illuminance within the space [50]. Appropriate illumination helps alleviate visual fatigue and enhance work efficiency, while contributing to energy savings by reducing the excessive use of artificial lighting [51,52]. Conversely, an imbalance in indoor illuminance can cause visual discomfort for occupants and lead to decreased productivity in work environments [53]. To quantitatively analyze these issues, this study employed the uniformity ratio [54] as an indicator to evaluate the uniformity of indoor illuminance. Generally, a uniformity ratio of 0.4 or higher is considered desirable [55,56]. In this study, the uniformity ratio was calculated by taking the ratio of the minimum illuminance to the average illuminance. Additionally, this study analyzed useful daylighting illuminance (UDI) to qualitatively evaluate indoor illuminance. UDI refers to the percentage of time when indoor illuminance falls within 100–2000 lx, and it serves as a reliable indicator for evaluating potential glares caused by excessive illuminance [57]. Illuminance levels exceeding 2000 lx are generally associated with glares, making UDI an important criterion in evaluating a comfortable indoor lighting environment [51]. Furthermore, an increase in the number of points exceeding 2000 lx in an indoor space indicates excessive natural light penetration, increasing the likelihood of glares [58]. This study analyzed not only the distribution of illuminance but also light spectral characteristics. Natural light has continuous and balanced spectral characteristics that positively affect human circadian rhythms and visual comfort [37,59]. Consequently, examining the similarity between the spectral characteristics of the light entering through the daylighting device and natural outdoor light is considered an important evaluation metric for ensuring the physiological and psychological comfort of indoor environments [60]. Therefore, this study aimed to verify the performance of the proposed system in terms of not only optical loss but also spectral fidelity by comparing and analyzing the similarity between the light entering through the light duct and natural outdoor light.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Proposed Light Duct Technology

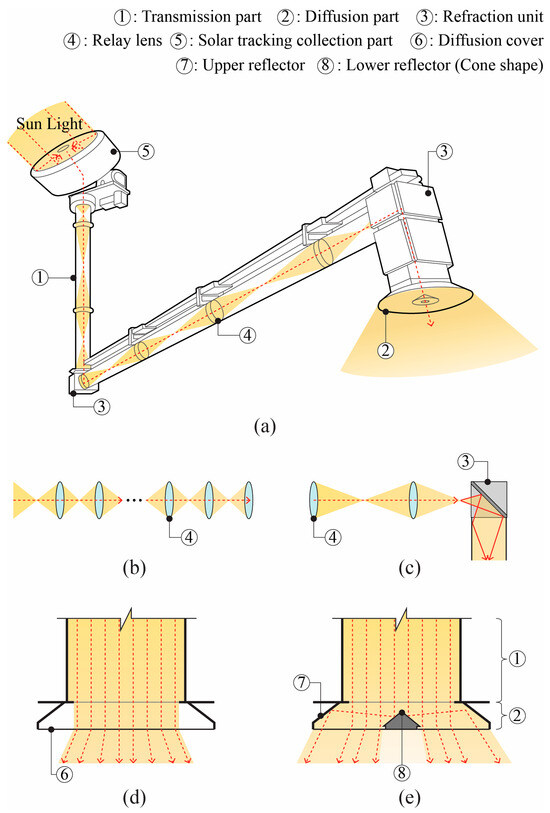

The light duct technology proposed herein features a structure that transmits natural light using multiple relay lenses, as shown in Figure 2. It incorporates a conical reflector in the diffusion part. We hypothesized that this structure will reduce optical losses during long-distance light transmission compared to conventional light ducts. Further, by enhancing light diffusion in the diffusion part, we can reduce lighting energy consumption and improve illuminance uniformity in indoor spaces. The details of the light duct technology proposed herein are discussed below.

Figure 2.

Light duct technology based on relay lenses: (a) Structure of the light duct employing relay lenses, (b) light propagation through relay lenses in the transmission part, (c) refraction unit of the transmission part, (d) the diffusion part of existing light duct systems, and (e) the diffusion part developed herein.

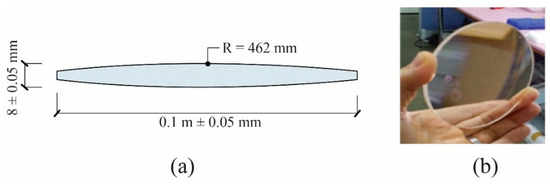

First, the transmission part of the developed light duct was constructed by arranging relay lenses in series with aspherical designs at 1 m intervals, as shown in Figure 2b. Each relay lens used in the transmission part had a diameter of 100 mm, thickness of 8 mm, and radius of curvature of 462 mm, as shown in Figure 3. All relay lenses were made of silica, which has excellent transmittance characteristics. The proposed light duct ensured stable light paths during vertical and horizontal transmission using a refraction unit with 95% reflectivity, as shown in Figure 2c.

Figure 3.

Relay lens (a) specifications and (b) image.

Second, the diffusion part was configured to achieve double reflection, unlike the diffusion cover method used in existing light ducts, as shown in Figure 2e. To achieve this, an upper reflector and a conical lower reflector were installed in the diffusion part. The interior of the double-reflection diffusion part used in this study was coated with a high-reflectance film with a reflectance of 98%.

External natural light entering through the collection and transmission parts sequentially passed through the lower and upper reflectors, undergoing diffusion in multiple directions. This broadened the emission range compared to existing single-reflection diffusion parts, enhancing the daylighting performance. Additionally, the lower reflector partially shaded the intense concentrated light moving downward through the transmission part, mitigating the concentration of light in specific areas below the diffusion part and addressing the issue of uneven indoor illuminance.

2.2. Environment Setup and Performance Evaluation Methods

We constructed a testbed to analyze the lighting energy reduction and indoor lighting performance of the developed light duct, which was manufactured by Sunportal Co., Ltd. (Seoul, South Korea). The details are as follows.

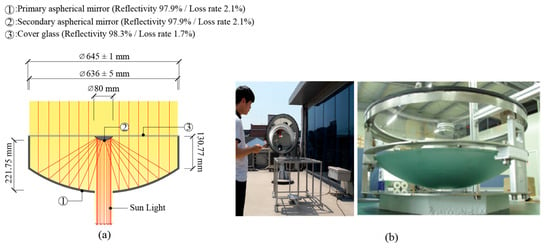

First, we established three cases (Table 2) to evaluate the performance of different light duct configurations. Case 1 involved a light duct that uses an optical-fiber-based transmission part—similar to that in existing systems—and a diffusion part equipped with a diffusion cover. In this case, the cross-sectional area of the optical fiber bundle was set equal to that of the relay lens. The optical fiber was configured with a diameter of 5 mm. A transmission distance of 20 m was set because the effective range of POFs is 20 m. Cases 2 and 3 employed a relay-lens-based transmission part and a double-reflection-structure diffusion part developed in this study. The transmission lengths for Cases 2 and 3 were 20 and 30 m, respectively. In both cases, the optical cone angle of the lower conical reflector set to 60°. The collection part constituted an aspherical mirror in all cases; the specifications of this aspherical mirror are shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Cases established for performance evaluation.

Figure 4.

Structure of the aspherical-mirror-type collection part: (a) Cross-section and (b) configuration of the collection part.

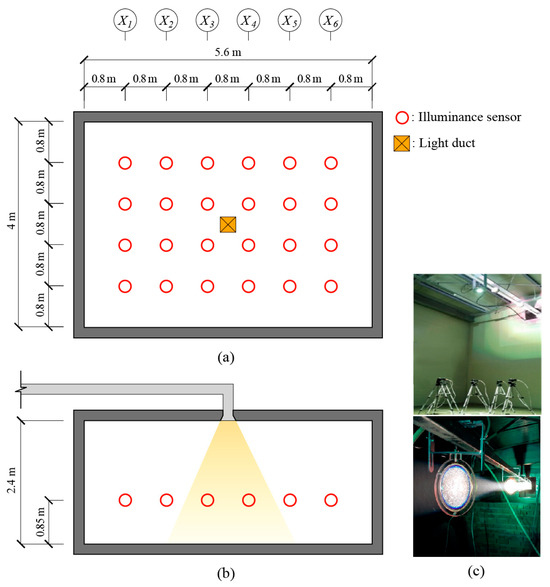

Second, we constructed three testbeds for performance evaluation, as shown in Figure 5. The light ducts were installed within a recessed structure in the ceiling, with only the bottom of the diffusion part protruding into the room. The testbed featured a rectangular internal space with floor dimensions of 5.6 m × 4.0 m and a reflectivity of 25%. The ceiling height of the testbed is 2.4 m, and the reflectance values of the walls and ceiling were 46% and 86%, respectively.

Figure 5.

Plane and cross-sectional views of the testbed: (a) plane view, (b) cross-sectional view, and (c) configuration.

Third, we installed 24 illuminance sensors vertically on the floor surface to analyze the illuminance distribution across the testbed, as shown in Figure 5a. Considering the ceiling and work-surface heights, the sensor height was set to 0.85 m above the floor. This allowed for illuminance distribution monitoring across the testbed for each case. Based on obtained data, the percentage of the indoor space with UDI between 100 lx and 2000 lx was determined. We used the uniformity ratio as an index for evaluating indoor lighting uniformity based on the measurements. The uniformity ratio was calculated as the ratio of the average illuminance to the minimum illuminance within the indoor space based on data from the 24 sensors. Furthermore, to determine the uniformity ratio values, we calculated the average illuminance for each of the columns X1–X6 shown in Figure 5 and utilized these values in uniformity ratio analysis for each case.

Fourth, we analyzed the spectrum of indoor light radiated through the diffusion part in each case and compared its similarity with that of external natural light. The spectral distribution was recorded for wavelengths ranging from 380 to 780 nm. Spectral measurements were performed using a CS-2000 spectroradiometer (Konica Minolta, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and indoor/outdoor illuminance values were measured using an ML-020S-O illuminance meter (EKO Instruments Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). In the measurement equipment, an illuminance sensor and a spectral measurement device were placed on the same axis, allowing for the simultaneous measurement of illuminance and spectral characteristics at the same point. However, due to limitations of the measurement equipment, spectral distribution analysis of external natural light was performed only for Cases 1 and 3. To quantitatively compare the spectral distributions, spectral angle mapper (SAM) and root mean square error (RMSE) were used to evaluate morphological and intensity differences between the spectra of natural outdoor light and transmitted indoor light, respectively [61]. SAM was calculated by assuming the two spectra as vectors and computing the angle between them, which represented the difference in the shape of the spectra. SAM was calculated using (2). RMSE quantifies the intensity difference between two spectral curves as a single value and is calculated using (3). Lower SAM and RMSE values indicate greater similarity between the spectra of natural outdoor light and transmitted indoor light.

Here, S1(λi) and S2(λi) denote the spectrum values at each wavelength λi and N denotes the number of wavelength samples.

Here, S1(λi) and S2(λi) denote the spectrum values at each wavelength λi and N denotes the number of wavelength sections used for comparison.

Fifth, performance evaluation was conducted in Busan, South Korea, where distinct seasonal characteristics are evident, as shown in Table 3. Busan (35.18° N, 129.07° E) is located in the mid-latitudes, within the temperate oceanic climate zone. It is characterized by high solar radiation in the summer and low solar altitudes in the winter. This results in distinct seasonal variations in solar radiation. These mid-latitude climatic characteristics make this study universally applicable and useful for analyzing lighting environments in similar climate zones. The dates of experiments performed in summer and winter were 11 June 2025, and 13 December 2024, respectively, with average cloud covers of 4.1 and 4.3, respectively. The performance evaluation was conducted from 10:00 to 15:00. Indoor and outdoor illuminance values were recorded at 1 min intervals for each time slot and then averaged. External variable control was not performed separately during performance evaluation. The analysis was conducted using the average solar radiation and cloud cover data presented in Table 3 as the baseline conditions. This allowed for representative performance comparison based on seasonal solar conditions. Spectral distribution analysis was performed only for the south-facing direction on 10 June 2024, which falls within the summer season. The average outdoor illuminance and average cloud cover for that day were 104,666 lx and 4.8, respectively.

Table 3.

Solar altitude and azimuth in different seasons.

3. Performance Evaluation Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Evaluation Results

This study developed alternative technologies for the transmission and diffusion parts of light ducts to improve their daylighting performance. The performance evaluation results are discussed below.

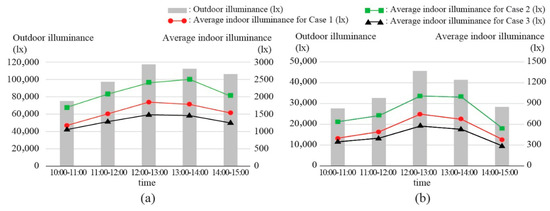

First, the analysis results for average indoor illuminance for each case are shown in Figure 6. Case 2 improved the average indoor illuminance by an average of 27.3% compared to Case 1. This confirmed that the proposed light duct exhibits low loss during the transmission of external natural light. However, in Case 3, the indoor average indoor illuminance decreased by an average of 17.1% compared to Case 1. This indicated that increasing the transmission distance reduces the transmission efficiency. Therefore, for improving indoor average illuminance, Case 1 is superior to Case 3.

Figure 6.

Performance evaluation results for each case (indoor average illuminance): (a) summer and (b) winter.

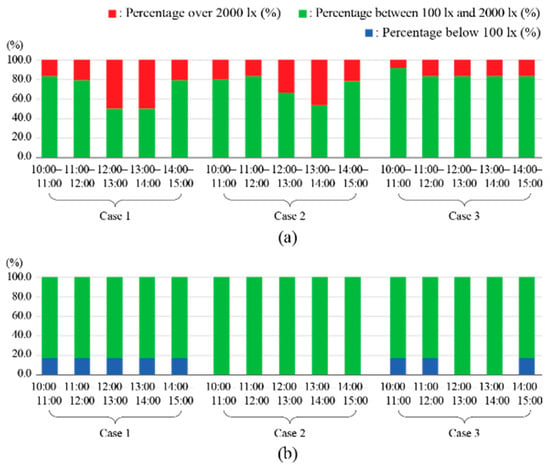

Second, the UDI values analyzed for each case are shown in Figure 7. During summer, the indoor illuminance level exceeded 2000 lx in all cases. This indicated that natural light entering through the light duct could cause glares. However, in Cases 2 and 3, the percentage of values exceeding 2000 lx decreased by an average of 13.2% and 52.6%, respectively, compared to that in Case 1. This demonstrated that increasing the transmission distance effectively reduced the likelihood of glares. In particular, Case 3 showed a higher average illuminance within the UDI range of 100–2000 lx, which was 13.3% and 1.4% higher compared those in Cases 1 and 2, respectively. Thus, Case 3 provided a more comfortable visual environment than Cases 1 and 2. During winter, no measurement points in Cases 1, 2, or 3 recorded indoor illuminance values exceeding 2000 lx. However, in Cases 1 and 3, the indoor illuminance values fell below 100 lx, indicating inadequate daylight for ensuring sufficient UDI. However, Case 3 achieved a higher proportion of illuminance values lying within the UDI range of 100–2000 lx compared to Case 1, making it more effective in improving the lighting environment.

Figure 7.

Performance evaluation results for each case (UDI): (a) summer and (b) winter.

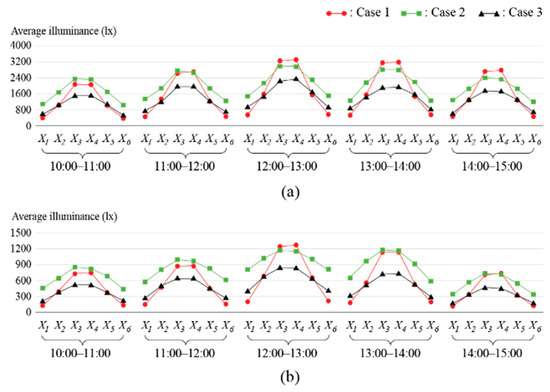

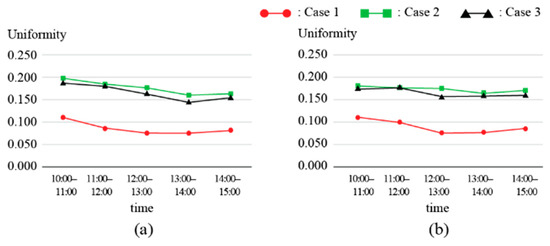

Third, the distribution of average illuminance values from columns X1–X6 in each case for summer and winter is shown in Figure 8. Cases 2 and 3 exhibited less variations in illuminance compared to Case 1. This was because Cases 2 and 3 included a lower reflector in the diffusion part, which helped disperse excessive light that would otherwise be directed toward the bottom of the diffusion part. Cases 2 and 3 demonstrated an average improvement of 47.8% in the indoor space uniformity ratio compared to Case 1, as shown in Figure 9. However, since the uniformity ratio was <0.4 in all three cases, the use of a light duct alone is inadequate to create a comfortable lighting environment.

Figure 8.

Average illuminances of columns X1–X6 for each case: (a) summer and (b) winter.

Figure 9.

Performance evaluation results for each case (indoor uniformity ratio): (a) summer and (b) winter.

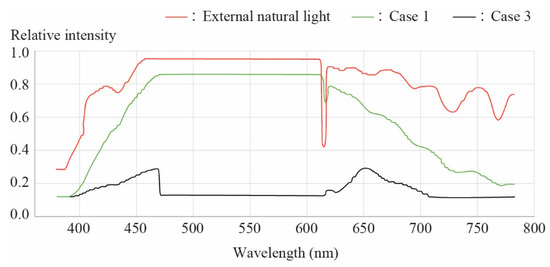

Fourth, we compared the spectral distribution of light entering through the light duct and external natural light, as shown in Figure 10. The external-light solar spectrum displayed a continuous and gradual distribution across the entire range from 380 to 780 nm. Case 3 generally maintained a similar curve. However, light transmitted in Case 1 exhibited local peaks in specific wavelength ranges while showing a rapid decrease in relative intensity in the long-wavelength range, resulting in a significant difference compared to actual natural light. The SAM and RMSE values, which were calculated as quantitative indicators of the spectral distribution, revealed that light transmitted in Case 3 exhibited greater similarity to natural outdoor light. Specifically, the SAM value difference between external natural light and light transmitted in Case 3 was ~15.1°, indicating a high degree of similarity in their spectral curves. In contrast, light transmitted in Case 1 showed a large SAM value difference of 19.5°. Furthermore, the RMSE value for Case 3 was low (0.267), indicating small differences between the intensity distribution of natural light and light transmitted in this case. However, Case 1 showed a larger error, with an RMSE value of 0.684.

Figure 10.

Spectral analysis results.

3.2. Discussion

This study developed alternative technologies for the transmission and diffusion parts of light ducts to enhance their daylighting performance and verified their performance using a testbed. The daylighting performance of the proposed light duct system was quantified, and the influence of each part on improving the indoor lighting environment was comprehensively examined. This study aimed to identify the feasibility and limitations of applying the proposed technology by comparing and analyzing performance differences among three cases, focusing on the transmission distance, double-reflection-structure of the diffusion part, and spectral characteristics of transmitted light.

The average indoor illuminance observed in Case 2 was higher than that in Case 1. This indicates that Case 2 is the most efficient configuration for transmitting external natural light into indoor spaces. Additionally, in Case 2, a conical reflector was placed below the diffusion part in addition to the upper reflector, resulting in double reflection. This structure improved the uniformity ratio by shading and scattering natural light concentrated below the diffusion part. However, in Cases 1 and 2, glares can occur due to the influx of natural light during summer, suggesting the need for additional shading devices.

In summer, in Case 3, the average indoor illuminance decreased due to reduced natural light entering the interior. However, this increased the proportion of measurement points within the UDI range of 100–2000 lx while reducing the number of measurement points exceeding 2000 lx, indicating a lower concern for glares compared to Cases 1 and 2. This suggests that in summer, it is preferable to control the light duct to ensure sufficient UDI rather than simply increasing the transmission efficiency. However, the glare reduction trend observed is for a limited time period and weather conditions. Therefore, further validation using quantitative analysis is required, including UDI exceedance maps and glare probability indices.

In winter, no measurement points in Cases 1, 2, and 3 exhibited indoor illuminance exceeding 2000 lx, indicating little concern regarding glares. However, in Cases 1 and 3, illuminance values of <100 lx were observed, suggesting that separate lighting control may be required to ensure a comfortable lighting environment. Further, Cases 2 and 3 showed a higher proportion of illuminance values lying within the UDI range of 100–2000 lx compared to Case 1, making them more suitable for improving the lighting environment.

Cases 1, 2, and 3 showed uniformity ratios of <0.4, suggesting that light ducts alone may be inadequate for creating a comfortable lighting environment. Therefore, integrated control involving supplementary artificial lighting and shading device control is required. This study highlights the need to incorporate artificial lighting based on illuminance distribution characteristics observed when light ducts are used. Additionally, it highlights the need to control excessive light entry using sunshades during periods of high solar irradiance. These integrated control strategies are expected to mitigate illuminance variations observed when operating a light duct alone and contribute to creating a stable lighting environment under various solar conditions.

The spectral distributions of natural light and light transmitted in Cases 1 and 3 were compared. The results showed that the light transmitted in Case 3 was similar to natural light in terms of spectral characteristics. This suggested that the degree of spectral distortion can vary depending on the optical structure and material properties of the light duct. However, this study focused on analyzing the qualitative trends of spectral distributions. Therefore, it is necessary to quantitatively verify spectral fidelity by introducing SAM and RMSE for comparison with a baseline (i.e., external natural light) in future work. Case 3 is preferable because it transmits light with spectral characteristics similar to those of outdoor sunlight effectively. Additionally, it generates a light environment similar to that generated by natural light in an indoor setting, even though the transmission distance is longer compared to Case 1. Meanwhile, Case 1 fails in reproducing the continuous spectral characteristics of actual sunlight due to its concentration on specific wavelengths.

Considering these findings, the light duct technology proposed herein is suitable for improving the lighting environment of indoor spaces. Its efficiency is expected to increase when integrated with controlled lighting and shading technologies. Case 3 is found to be more effective in creating a comfortable lighting environment compared to a conventional light duct with a transmission distance of 20 m.

4. Conclusions

This study developed technical alternatives for the transmission and diffusion parts of light ducts to enhance their daylighting performance and validated their performance through experiments conducted using a testbed. The findings are as follows.

First, the light duct proposed in this study reduced light loss during the transmission of external natural light into the interior using multiple relay lenses arranged in series within the transmission part. Additionally, in the diffusion part, rather than simply installing a diffusion cover, upper and lower reflectors were installed to create a double-reflection effect, allowing more light to spread evenly throughout the indoor space. In particular, the lower reflector was placed at the bottom center of the diffusion part to address illuminance imbalance caused by concentrated light entering the bottom of the diffusion part.

Second, the light duct with a transmission distance of 20 m demonstrated excellent transmission efficiency, achieving ~27.3% improvement in indoor average illuminance compared to existing light duct technologies based on optical fibers with the same transmission distance. Additionally, the double-reflection structure of the diffusion part reduced illuminance variations, resulting in an average improvement of 47.8% in the indoor uniformity ratio.

Third, during summer, excessive natural light entering indoors caused glares. However, the light duct with a transmission distance of 30 m maintained high UDI (100–2000 lx) and no measurement points exceeded 2000 lx, making it advantageous for establishing a comfortable visual environment. In winter, there was no risk of glares; however, in some cases, low illuminance levels (<100 lx) were observed. This suggested that the use of light ducts alone may not be adequate and should be supplemented with artificial lighting and control technology.

Fourth, the spectral analysis results showed that the proposed light duct exhibited a spectral distribution similar to that of external sunlight, indicating its ability to retain the continuous spectral characteristics of natural light transmitted in the indoor environment. Existing light duct technologies based on optical fibers suffer from distortion at certain wavelengths, limiting their capability to transmit sunlight. The proposed light duct technology has the potential to improve the utilization of natural light, reducing reliance on artificial lighting and ultimately contributing to lighting energy savings and an improvement in the quality of indoor environments. These results are expected to serve as a basis for future eco-friendly building design and the establishment of daylighting-based energy-saving strategies.

Thus, the proposed light duct technology exhibited superior performance compared to conventional light ducts in terms of the average illuminance, uniformity ratio, glare, and spectral similarity. It was proven to be more effective in creating a comfortable light-ing environment compared to an existing design with a transmission distance of 20 m, even when the transmission distance reached 30 m. Future research should consider strategies for integrating the control of light ducts, artificial lighting, and shading systems. Additionally, the optimization of relay lens spacing should be further reviewed. It will also be necessary to build a hybrid control model that includes various diffuser arrangements and reflector combinations, and its daylighting and lighting performance should be experimentally verified in a real environment. Future research should consider strategies for integrating the control of light ducts, artificial lighting, and shading systems, and further review regarding the optimization of relay lens spacing will also be necessary. It is necessary to build a hybrid control model that includes various diffuser arrangements and reflector combinations and experimentally verify its daylighting and lighting performance in a real environment. Although this was an experimental study focusing on the optical performance of light ducts and improving indoor lighting environments, quantitative evaluations of lens material costs, manufacturing and installation expenses, maintenance cycles, and other factors are required for practical applications. Therefore, we will conduct ray tracing-based simulations as well as economic feasibility and environmental sustainability assessments in the future to comprehensively verify the technical performance and cost effectiveness of the proposed light duct system. Finally, since this study was conducted under specific climatic conditions, it has limitations in fully reflecting various regional and environmental factors. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance the universality and applicability of the technology through additional empirical studies that consider these climatic variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H. and T.H.; Methodology, M.L., S.H. and J.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; Writing—review and editing, J.S. and H.L.; Funding acquisition, H.L.; Visualization, S.H.; Investigation, S.H.; Formal analysis, S.H. and J.S.; Supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT; RS-2023-00208303). This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. RS-2024-00441860).

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Taegon Han was employed by the company SunPortal Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Deng, L.; Cao, C.; Li, W. Impacts of carbon emission trading prices on financing decision of green supply chain under carbon emission reduction percentage measure. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 75929–75944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinwei, S.; Xiang, C.; Caixia, L.; Xin, S.; Yue, Y.; Shize, Z. High-speed rail electric traction carbon emission calculation method based on carbon flow theory. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 102096–102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global Trends. Global Energy Review. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025/global-trends (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- IEA. Buildings. Energy Efficiency Policy Toolkit. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-policy-toolkit-2025/buildings (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- EIA. 2018 Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey Final Results. CBECS. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Song, J.; Dessie, B.B.; Gao, L. Analysis and comparison of daylighting technologies: Light pipe, optical fiber, and heliostat. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jin, M.; Liu, M.; Li, S. Integrated systems of light pipes in buildings: A state-of-the-art review. Buildings 2024, 14, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzini, P. Daylight performance of the modified double light pipe (MDLP) through yearly experimental tests on a scale model of the system. Sol. Energy 2023, 266, 112179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, K.; Ramamurthy, K. Review on fibre-optic-based daylight enhancement systems in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 163, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, E.K.W.; Kocifaj, M.; Li, D.H.W.; Kundracik, F.; Mohelníková, J. Straight light pipes’ daylighting: A case study for different climatic zones. Sol. Energy 2018, 170, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paroncini, M.; Calcagni, B.; Corvaro, F. Monitoring of a light-pipe system. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee, H. Evaluation of energy performance and daylight utilization in light shelves integrated with transparent solar panels. Energy 2025, 326, 136336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee, H. Effectiveness of improving indoor uniformity of light shelves using location-awareness technology. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee, M.; Lee, H. Effectiveness of internal light shelves to improve daylighting. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Hwang, T.; Jung, G.J.; Rhee, K.N. Cooling capacity evaluation of thermally activated light shelf (TALS) systems. Build. Environ. 2023, 235, 110214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Seo, J.; Lee, H. Development of a solar-tracking movable louver with a PV module for building energy reduction. Buildings 2025, 15, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Tao, S.; Tao, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, J. The effect of louver blinds on the wind-driven cross ventilation of multi-storey buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 54, 104614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Lin, P. Analysis of dynamic louver control with prism redirecting fenestrations for office daylighting optimization. Energy Build. 2022, 262, 112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunay, H.B.; O’Brien, W.; Beausoleil-Morrison, I.; Gilani, S. Development and implementation of an adaptive lighting and blinds control algorithm. Build. Environ. 2017, 113, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, I.T.; Choi, A.S.; Sung, M.K. Evaluation of optimized PV power generation and electrical lighting energy savings from the PV blind-integrated daylight responsive dimming system using LED lighting. Sol. Energy 2014, 107, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Q. An automated control of daylight blinds and artificial lighting integrated scheme for therapeutic use. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Choi, A.; Sung, M. Impact of bi-directional PV blind control method on lighting, heating and cooling energy consumption in mock-up rooms. Energy Build. 2018, 176, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, L. Evaluation methods of the daylight performance and potential energy saving of tubular daylight guide systems: A review. Indoor Built Environ. 2022, 31, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocifaj, M.; Petržala, J. Designing of light-pipe diffuser through its computed optical properties: A novel solution technique and some consequences. Sol. Energy 2019, 190, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.; Muneer, T. Light-pipe prediction methods. Appl. Energy 2004, 79, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivo, C.; Bonomolo, M.; Congedo, P.M. Modeling of light pipes for the optimal disposition in buildings. Energies 2019, 12, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya’u, M.J. A review on solar tracking systems and their classifications. J. Energy Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 2, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, J.A.; Bonilla, J.; Roca, L.; Berenguel, M. New low-cost solar tracking system based on open source hardware for educational purposes. Sol. Energy 2018, 174, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukdir, Y.; Omari, H.E.L. Novel high precision low-cost dual axis sun tracker based on three light sensors. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamodiya, U.; Tiwari, N. Dual-axis solar tracking system with different control strategies for improved energy efficiency. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 111, 108920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkari, O.; Fadar, A.E.L.; Amlal, I.; Haddi, A.; Hamidoun, M.; Hamdoune, S. A new sun-tracking approach for energy saving. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 820–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.; Muneer, T. Modelling light-pipe performances—A natural daylighting solution. Build. Environ. 2003, 38, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zou, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, H.; Song, J. Measurement and analysis of light leakage in plastic optical fiber daylighting system. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fend, T.; Jorgensen, G.; Küster, H. Applicability of highly reflective aluminium coil for solar concentrators. Sol. Energy 2000, 68, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgülü, S.; Ekren, N. Energy saving in lighting system with fuzzy logic controller which uses light-pipe and dimmable ballast. Energy Build. 2013, 61, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakopoulou, K.; Kolokotsa, D.; Santamouris, M.; Kousis, I.; Asproulias, H.; Giannarakis, I. Analysis of the experimental performance of light pipes. Energy Build. 2017, 151, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Ali, S.F.; Rakshit, D. Performance evaluation of a top lighting light-pipe in buildings and estimating energy saving potential. Energy Build. 2018, 179, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, D.S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Garg, H.; Kumar, R.R.S. Computational analysis and optimization of daylight collector geometry for removal of hotspots in circular mirror light pipe. Sol. Energy 2023, 264, 112066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshnia, E.; Rahnamayiezekavat, P.; Rashidi, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Samali, B. Curve optimization for the anidolic daylight system counterbalancing energy saving, indoor visual and thermal comfort for Sydney dwellings. Energies 2023, 16, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, K.; Ramamurthy, K. Daylight performance of collector-diffuser combinations in light pipe systems at different geographical locations. Sol. Energy 2024, 267, 112254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeb, S.; Joarder, M.A.R. Daylighting and energy performance optimization of anidolic ceiling systems for tropical office buildings. Build. Environ. 2024, 265, 112032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, K.; Ramamurthy, K. Location-specific optimization of free conic dome daylight collector for improved light pipe performance. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Rajagopalan, P.; Woo, J.; Garg, H. Harnessing sunlight for indoor illuminance using a Fresnel lens-based daylighting system. Energy Build. 2025, 342, 115877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I. Fiber-based daylighting system using trough collector for uniform illumination. Sol. Energy 2020, 196, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, S.; Feng, D.; Ni, Y.; Yu, S.; Song, J.; Ren, B.; Ma, D.; Duan, M.; Lin, B. Advancing fiber-optic daylighting system integrated with freeform optics for indoor workstation lighting. Build. Simul. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Lv, H.; Whang, A.J.W.; Su, Y. Analysis of a novel design of uniformly illumination for Fresnel lens-based optical fiber daylighting system. Energy Build. 2017, 154, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, M.; Park, S.M.; Kim, W.; Lee, C.; Kim, C.; Kim, D.S. Injection molded plastic lens for relay lens system and optical imaging probe. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2015, 16, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, B.; Darian, S.B.; Kim, Y.; Oh, J.; Ghasemi, M.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.K. Spectral multiplexing of fluorescent endoscopy for simultaneous imaging with multiple fluorophores and multiple fields of view. Biosensors 2022, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Hua, H. Optical design and system engineering of a multiresolution foveated laparoscope. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 3058–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choi, C.; Sung, M. Development of a dimming lighting control system using general illumination and location-awareness technology. Energies 2018, 11, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bournas, I. Daylight compliance of residential spaces: Comparison of different performance criteria and association with room geometry and urban density. Build. Environ. 2020, 185, 107276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, V.; Kurian, C.P.; Augustine, N. Optimizing daylight glare and circadian entrainment in a daylight-artificial light integrated scheme. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 38174–38188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantzos, I.; Sadeghi, S.A.; Kim, M.; Xiong, J.; Tzempelikos, A. The effect of lighting environment on task performance in buildings—A review. Energy Build. 2020, 226, 110394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte-Valiente, A.; Castillo-Sequera, J.L.; Castillo-Martinez, A.; Gómez-Pulidov, J.M.; Gutierrez-Martinez, J.M. An artificial neural network for analyzing overall uniformity in outdoor lighting systems. Energies 2017, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFS-EN 12464–1:2011; The Indoor Lighting Standard. ENSTO: Uusimaa, Finland, 2011. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/30549/d5880e1a3a95469d840804022206edf3/SIST-EN-12464-1-2011.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Abdelsamie, M.M.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Fatouh, M.; Liu, J.; Ali, M.I.H. Development of a comprehensive simulation to explore the energy-saving and daylighting features of a multifunctional window in tropical climates. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 325, 119325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdad, A.A.S.; Fadzil, S.F.S.; Onubi, H.O.; BenLasod, S.A. Sensitivity analysis linked to multi-objective optimization for adjustments of light-shelves design parameters in response to visual comfort and thermal energy performance. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabil, A.; Mardaljevic, J. Useful daylight illuminance: A new paradigm for assessing daylight in buildings. Light. Res. Technol. 2005, 37, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. A review of daylighting design and implementation in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubekri, M.; Cheung, I.N.; Reid, K.J.; Wang, C.-H.; Zee, P.C. Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: A case-control pilot study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennison, P.E.; Halligan, K.Q.; Roberts, D.A. A comparison of error metrics and constraints for multiple endmember spectral mixture analysis and spectral angle mapper. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 93, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).