Impact of Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards on the Mental Health Outcomes of Construction Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

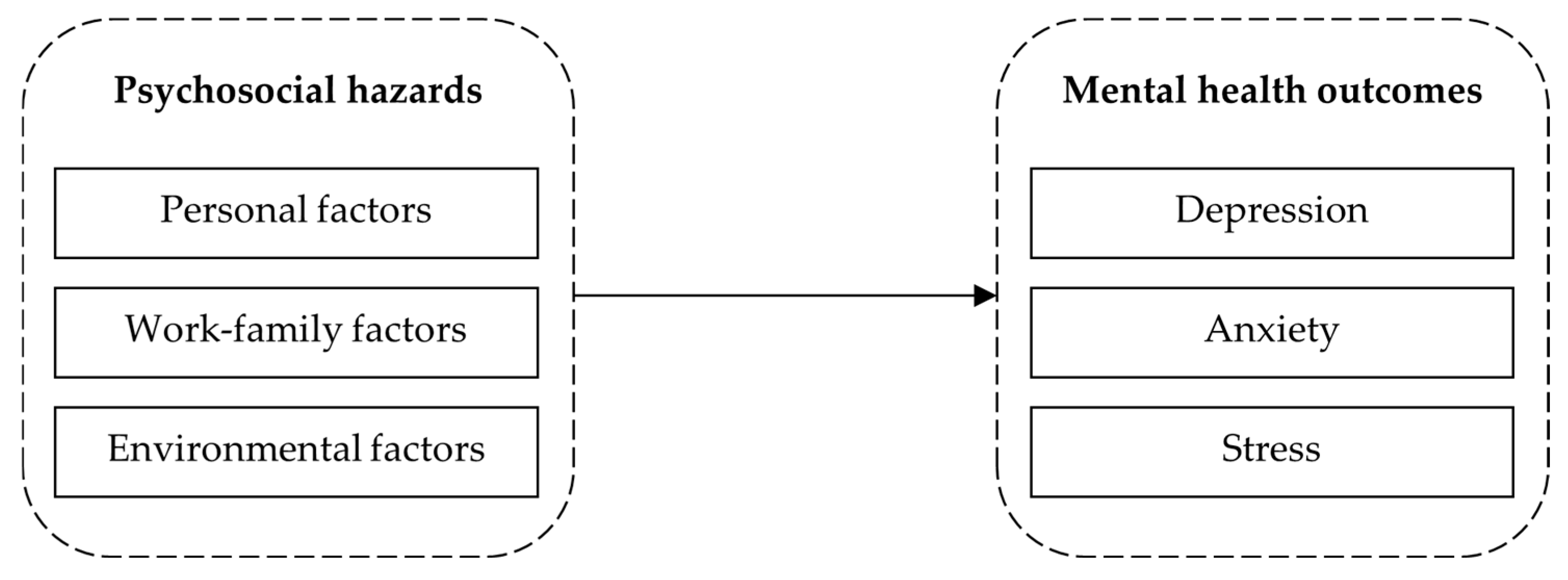

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Model Development

2.1. Psychosocial Hazards

2.2. Mental Health

2.3. Conceptual Model Development

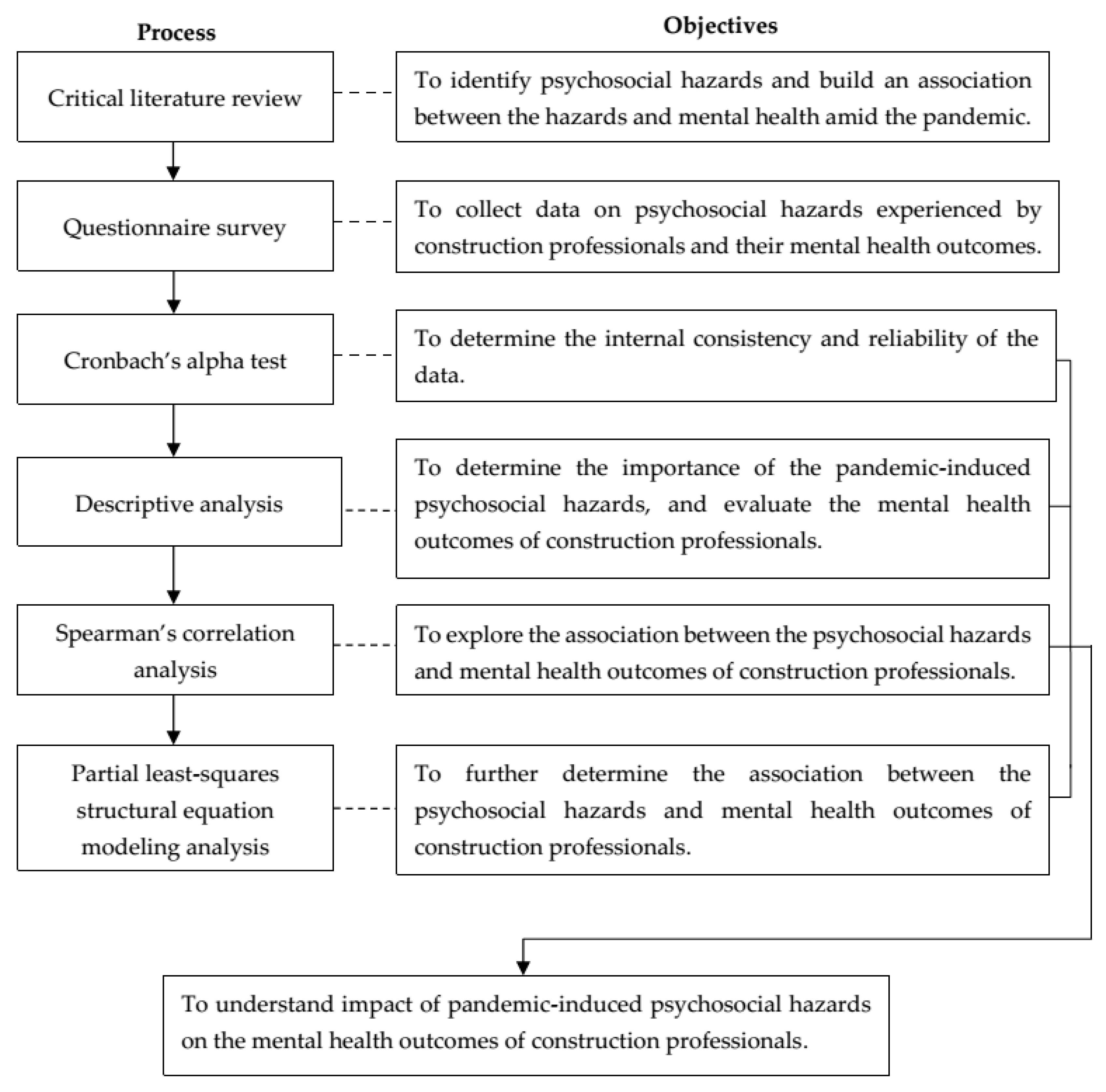

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

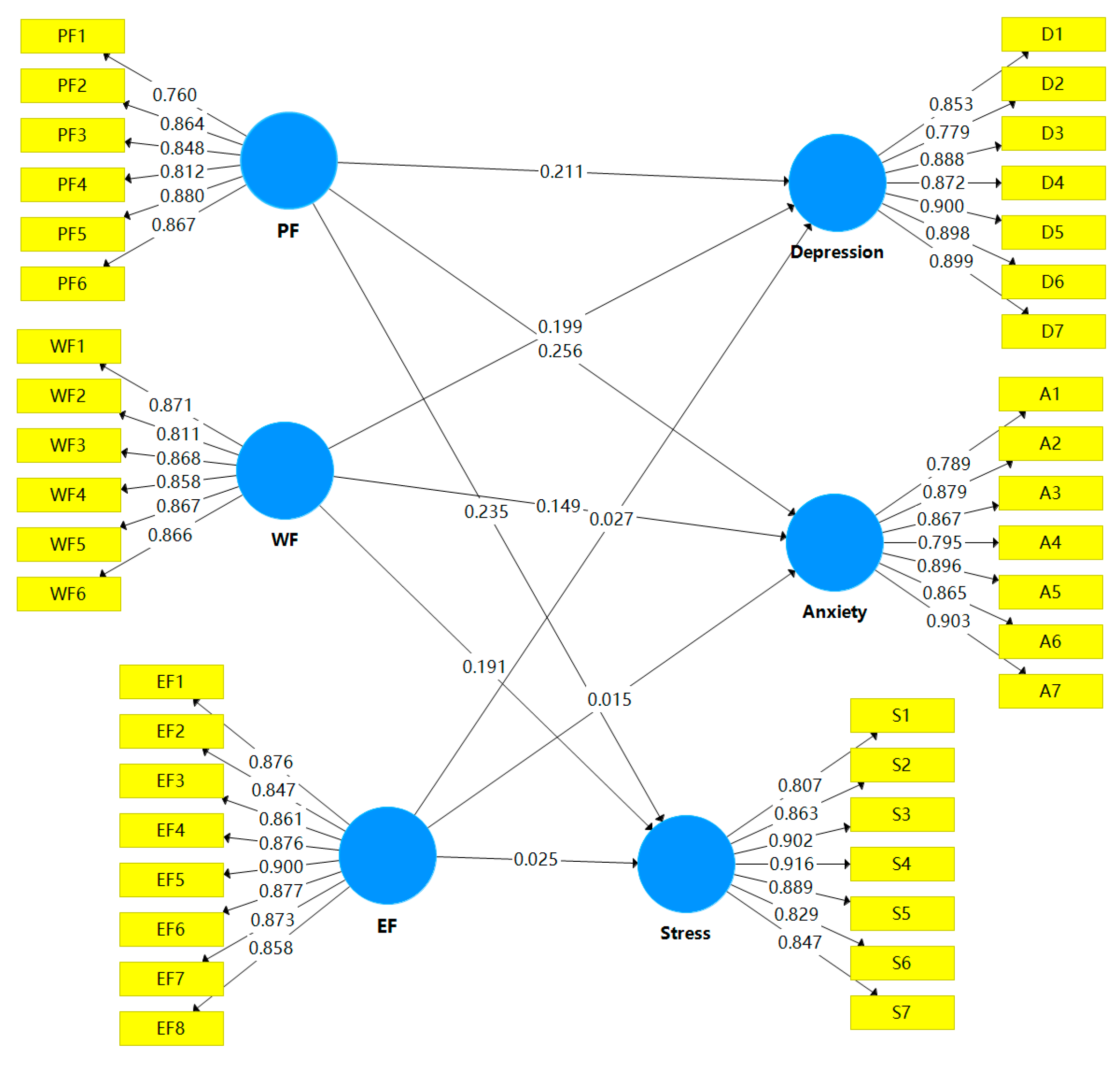

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards

4.3. Mental Health Outcomes

4.4. Impacts of Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards on Mental Health Outcomes

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mates in Mind. Mental Health in UK Construction: The Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://www.matesinmind.org/news/mental-health-in-uk-construction-the-statistics (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Dong, X.S.; Brooks, R.D.; Brown, S.; Harris, W. Psychological distress and suicidal ideation among male construction workers in the United States. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.C.; Akinyemi, T.A. Conceptualizing the dynamics of mental health among construction supervisors. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2593–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Xie, M.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J. Underneath social media texts: Sentiment responses to public health emergency during 2022 COVID-19 pandemic in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 118, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oufi, N.; Garza, C.D.; Nascimento, A. Dynamics of COVID-19 crisis management in hospitals and its long-term effects: An analysis using organizational resilience. Appl. Ergon. 2025, 126, 104486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, H.; Mirarchi, C.; Shahbodaghlou, F.; Pavan, A. Predicting the trends and cost impact of COVID-19 OSHA citations on US construction contractors using machine learning and simulation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 3461–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Tackling the Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis: An Integrated, Whole-of-Society Response; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021.

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Health and well-being of project-based construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, H.; Milaković, M.; Bubaš, M.; Bekavac, P.; Bekavac, B.; Bucić, L.; Čvrljak, J.; Capak, M.; Jeličić, P. Psychosocial risks emerged from COVID-19 pandemic and workers’ mental health. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1148634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Baylina, P.; Fernandes, R.; Ramalho, S.; Arezes, P. Healthcare workers’ mental health in pandemic times: The predict role of psychosocial risks. Saf. Health Work 2022, 13, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alboga, O.; Tantekin-Çelik, G.; Un, B.; Aydinli, S.; Erdis, E. The effects of COVID-19 on the construction sector: Before and after. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 119, 105278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Frimpong, S.; Su, Z. Work stressors, coping strategies, and poor mental health in the Chinese construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2023, 159, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Yang, L. Associations between COVID-19 infection experiences and mental health problems among Chinese adults: A large cross-section study. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Li, W.; Meng, Q.; Hu, X. Impacts of COVID-19 on construction project management: A life cycle perspective. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 3357–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Leung, M.Y.; Zhang, S. Examining the critical factors for managing workplace stress in the construction industry: A cross-regional study. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, A.; AbdulAziz, A.; Preece, C.N.; Shobowale, K. Evaluation of measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 on the construction sites. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikhart, H.; Pikhartova, J. The Relationship Between Psychosocial Risk Factors and Health Outcomes of Chronic Diseases: A Review of the Evidence for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015.

- Sun, C.; Hon, C.K.H.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B. The relationship between psychosocial hazards and mental health in the construction industry: A meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Hon, C.K.H.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B.; Wu, P. A bayesian network model for the impacts of psychosocial hazards on the mental health of site-based construction practitioners. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04022184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, C.K.H.; Sun, C.; Way, K.A.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Xia, B.; Biggs, H.C. Psychosocial hazards affecting mental health in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Australia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 31, 3165–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebar, A.L.; Taylor, A. Physical activity and mental health; it is more than just a prescription. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2017, 13, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. National Data in 2023. 2023. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 10 June 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Bureau of Statistics. National Data in 2024. 2024. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 10 June 2025). (In Chinese)

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H.; Zhang, R.P. Job quality and construction workers’ mental health. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kan, Z.; Kwan, M.P.; Cai, J.; Liu, Y. Assessing the impact of socioeconomic and environmental factors on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic based on GPS-enabled mobile sensing and survey data. Health Place 2025, 92, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, B.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. A systematic review of mental stressors in the construction industry. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2020, 39, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Wang, C.; and Boadu, E. Domains of psychosocial risk factors affecting young construction workers: A systematic review. Buildings 2022, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Duan, J.; Sunindijo, R.Y. Mental health outcomes and psychosocial hazards experienced by construction professionals with different demographic characteristics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Liu, T.; Yang, W.; Xia, F. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic perception on job stress of construction workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Deng, X.; Yang, W.; Fang, J. COVID-19 related stressors and mental health outcomes of expatriates in international construction. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 961726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L.M. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and emotional well-being of older adults. World J. Virol. 2022, 11, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Impact of COVID-19 on field and office workforce in construction industry. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preti, E.; Di Mattei, V.; Perego, G.; Ferrari, F.; Mazzetti, M.; Taranto, P.; Pierro, R.D.; Madeddu, F.; Calati, R. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Fromson, J.A.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation: A mixed-method study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Tasnim, S.; Sultana, A.; Faizah, F.; Mazumder, H.; Zou, L.; McKyer, E.L.J.; Ahmed, H.U.; Ma, P. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Resarch 2020, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Poudel, L.; Bhandari, N.; Adhikari, N.; Shrestha, B.; Poudel, B.; Bishwokarma, A.; Kuikel, B.S.; Timalsena, D.; Paneru, B.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression, anxiety and stress symptoms among construction workers in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochaiwong, S.; Ruengorn, C.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Awiphan, R.; Phosuya, C.; Ruanta, Y.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus dis-ease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Qu, X.L.; Wang, H. Mental health of community residents in Wuhan during the epidemic of COVID-19 and the influencing factors. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 35, 76–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhang, L.; Lang, Q.; Liao, C.; Wang, N.; Qin, M.; Huang, H. Work stress among Chinese nurses to support Wuhan in fighting against COVID-19 epidemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1002–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, J.; Hasan, A.; Kamardeen, I. Mental health challenges of manual and trade workers in the construction industry: A systematic review of causes, effects and interventions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 31, 1497–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.Q.; Li, S.S.; Yue, H.Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Xu, S.F. Analysis on anxiety status of Chinese netizens under the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) and its influencing factors. Mod. Tradit. Chin. Med. Mater. Medica-World Sci. Technol. 2020, 22, 686–691. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.P.; Wang, L.P.; Yu, B.; Li, H.Q.; Zheng, J.S. Adverse emotional response and its influencing factors among frontline health workers during coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic. Chin. J. Public Health 2020, 36, 677–681. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Zhou, D. The impact of COVID-19 on physical and mental health: A longitudinal study. SSM—Popul. Health 2023, 24, 101538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuntella, O.; Hyde, K.; Saccardo, S.; Sadoff, S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016632118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Linos, E.; Rodriguez, C.I.; Chen, M.L.; Dove, M.S.; Keegan, T.H. Prevalence and associations of poor mental health in the third year of COVID-19: U.S. population-based analysis from 2020 to 2022. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 330, 115622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyraz, G.; Legros, D.N.; Tigershtrom, A. COVID-19 and traumatic stress: The role of perceived vulnerability, COVID-19-related worries, and social isolation. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 76, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Di, Y.; Ye, J.; Wei, W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 26, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noopur. Identifying the stressors hindering performance in the Indian construction industry: An empirical investigation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 1053–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Arango, D.; Vasquez-Hernandez, A.; Botero-Botero, L.F. Assessment of subjective workplace well-being of construction workers: A bottom-up approach. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 36, 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.R.; Wang, K.; Yin, L.; Zhao, W.F.; Xue, Q.; Peng, M.; Min, B.Q.; Tian, Q.; Leng, H.X.; Du, J.L.; et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhao, J.; Guo, H. Analysis of psychological status and influencing factors of nursing staff in public health emergencies. Hehan Med. Res. 2021, 30, 3652–3656. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tong, R.; Wang, L.; Cao, L.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X. Psychosocial factors for safety performance of construction workers: Taking stock and looking forward. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 944–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Birkett, H.; Forbes, S.; Seo, H. COVID-19, flexible working, and implications for gender equality in the United Kingdom. Gend. Soc. 2021, 35, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, H. Home-Based Telework During the COVID-19 Pandemic; Mälardarlen University: Västerås, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Setyorini, D.; Swarnata, A.; Bella, A.; Melinda, G.; Dartanto, T.; Kusnadi, G. Social isolation, economic downturn, and mental health: An empirical evidence from COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Ment. Health Prev. 2024, 33, 200306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Haq, I.; Anam, S.M.A. Impacts of COVID-19 on the construction sector in the least developed countries. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2024, 42, 1085–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.L.; Lamontagne, A.D. COVID-19 and suicide risk in the construction sector: Preparing for a perfect storm. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Bataineh, M.F.; Mohamad, M.N.; Ajab, A.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Jarrar, A.H.; Habib-Mourad, C.; Jamous, D.O.A.; Ali, H.I.; Al Sabbah, H.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life: Is there any effect? A crosssectional study of the MENA region. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettman, C.K.; Abdalla, S.M.; Cohen, G.H.; Sampson, L.; Vivier, P.M.; Galea, S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D.; Steptoe, A.; Bu, F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Hui, B.P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Nam, B.H.; Hong, J.Y.; Cummings, C.E. Perceived vulnerability to disease, resilience, and mental health outcome of Korean immigrants amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A machine learning approach. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2023, 24, 04023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Que, J.; Lu, Q.; Liu, L.; Lu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Meng, S.; et al. The impact of quarantine on mental health status among general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 4813–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tull, M.T.; Edmonds, K.A.; Scamaldo, K.M.; Richmond, J.R.; Rose, J.P.; Gratz, K.L. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.Z.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Wu, Y.; Choi, E.P.H.; Wang, M.P.; Lam, T.H. Social distancing compliance under COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts: A population-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ge, J.; Yang, M.; Feng, J.; Qiao, M.; Jiang, R.; Bi, J.; Zhan, G.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and nonmembers of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People. Notice on Further Optimizing the Prevention and Control Measures of COVID-19 Pandemic. 2022. Available online: http://health.people.com.cn/n1/2022/1111/c14739-32564156.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- People. The COVID-19 Campaign in China Enters a New Stage—A Record of China’s Optimization of Pandemic Prevention and Control Measures in Accordance with Time and Situation. 2023. Available online: http://health.people.com.cn/n1/2023/0108/c14739-32601966.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Qian, J.; Zhang, B.T.; Qiu, W.F.; Jiang, Z.L.; Dong, X.Q.; Li, H.Q. Psychological crisis intervention on the psychological status of COVID-19 patients. China J. Health Psychol. 2021, 29, 101–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Nwaogu, J.M.; Naslund, J.A. Mental Ill-Health Risk Factors in the construction industry: Systematic review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, B.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Theoretical model for mental health management of project management practitioners in architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) project organizations. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 30, 914–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, J.M.; Moore, K.O.; Tang, S.; Christensen, H.; Faasse, K. Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Khan, N.A.; Soomro, M.A. The impact of moral leadership on construction employees’ psychological behaviours. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 69, 2817–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan, K.; Natarajan, R.; Dasgupta, C. Prevalence and risk factors for depression, anxiety, and stress among foreign construction workers in Singapore—A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Rajaraman, N.; Ghosh, S. Effectiveness of peer support to reduce depression, anxiety and stress among migrant construction workers in Singapore. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 4867–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Feng, C.; Xie, H.; Zhao, X.; Wu, G. Ambidextrous leadership and innovative behaviors in construction projects: Dual-edged sword effects and social information processing perspective. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 04022070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Technique, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Deep, S.; Sonkar, N.; Yadav, P.; Vishnoi, S.; Bhoola, V.; Kumar, A. Factors influencing the mental health of white-collar construction workers in developing economies: Analytical study during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04024058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Willaby, H.W.; Costa, D.S.J.; Burns, B.D.; Maccann, C.; Roberts, R.D. Testing complex models with small sample sizes: A historical overview and empirical demonstration of what Partial Least Squares (PLS) can offer differential psychology. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 84, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Estudillo, B.; Forteza, F.J.; Carretero-Gomez, J.M.; Rejon-Guardia, F. The role of organizational factors in promoting workers’ health in the construction sector: A comprehensive analysis. J. Saf. Res. 2024, 88, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Chung, J. Is safety education in the E-learning environment effective? Factors affecting the learning outcomes of online laboratory safety education. Saf. Sci. 2023, 168, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, O.; Koçak, Ö.E.; Younis, M.Z. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 Fear and the Moderator Effects of Individuals’ Underlying Illness and Witnessing Infected Friends and Family. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordjour, G.A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Tuffour-Kwarteng, L. Exploring construction employees’ perspectives on the potential causes of psychological health conditions in the construction industry: A study in Ghana. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2020, 17, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, M.; Zheng, P.; Lyu, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Luo, W.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Public Health Measures and the Control of COVID-19 in China. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, M.Y.; Su, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.J.; Gu, X.F.; Ma, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.K.; Ren, Z.F.; Ren, R.; et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Mayer, G.; Hummel, S.; Oetjen, N.; Gronewold, N.; Zafar, A.; Schulttz, J.H. Mental health burden in different professions during the final stage of the COVID-19 lockdown in China: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. The influence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on family violence in China. J. Fam. Violence 2022, 37, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ding, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, K.; Xiao, S.; Luo, T.; Yu, S.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Children and Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being Became Worse in Heavily Hit Chinese Provinces during the COVID-19 Epidemic. J. Psychiatry Brain Sci. 2021, 6, e210020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modelling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Macrolides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Salgado, C.; Camacho-Vega, J.C.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Linares-Manrique, M.; García-Iglesias, J.J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, L.; Vázquez-Lara, J.M.; et al. Psychological distress and work engagement of construction workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A differential study by sex. Buildings 2024, 14, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, N.; Scott-Young, C.M.; Naderpajouh, N.; Borg, J. Surviving adversity: Personal and career resilience in the AEC industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2023, 41, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. Real Gross Domestic Product by Industry Group. 2020. Available online: https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/gdp3q20_3rd.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

| Hazard | Literature Source | |

|---|---|---|

| The first dimension: Personal factors (PFs) | Worrying about infection with COVID-19 disease (PF1) | [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] |

| Less sleep due to the pandemic (e.g., having a problem falling asleep or reduced sleep time) (PF2) | [8,38,39,40,41,42] | |

| Improper strategies used to cope with the pandemic (e.g., denial, avoidance, smoking, or alcohol consumption) (PF3) | [30,35,38,43,44,45] | |

| Reduced exercise due to the pandemic (PF4) | [8,38,41,46,47] | |

| Increased severity of chronic illness and corresponding problems due to the pandemic (e.g., enhanced level of possibility of infection, or poorer situation of previous illness) (PF5) | [11,31,38,44,48] | |

| Personal traits (e.g., age, gender, and vulnerability) (PF6) | [38,48,49,50] | |

| The second dimension: Work–family-related factors (WFs) | Significantly increased workload due to the pandemic (WF1) | [8,42,51,52,53] |

| Worrying about relatives’ infection with COVID-19 disease (WF2) | [8,31,34,35,38,42,54] | |

| Frequently working overtime due to the pandemic (WF3) | [8,34,51,52] | |

| Work–life conflict due to the pandemic (WF4) | [8,42,52,55,56,57] | |

| Decreased income due to the pandemic (WF5) | [26,30,38,51,58,59,60,61,62] | |

| Inadequate career development opportunities due to the pandemic (WF6) | [30,51,58,60] | |

| The third dimension: Environmental factors (EFs) | Inadequate care from government departments or employers for minimizing the influence of the pandemic (EF1) | [35,42,53,63] |

| Inadequate epidemic prevention supplies (e.g., medicine or masks) (EF2) | [31,53,58,59,64,65] | |

| Discrimination due to infection or possible infection with COVID-19 disease (EF3) | [31,58,60,66] | |

| A variety of social distancing measures due to the pandemic (e.g., quarantine or restricted travel) (EF4) | [30,38,58,67,68,69] | |

| Too much negative information associated with the pandemic (EF5) | [8,30,38,70,71] | |

| Too much false information associated with the pandemic (EF6) | [30,38] | |

| More personal information reported to government due to the pandemic (e.g., frequently reporting personal health conditions to authorities) (EF7) | [72,73] | |

| More nucleic acid tests due to the pandemic (EF8) | [72,73,74] |

| Category | Profile | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 80.23% |

| Female | 19.77% | |

| Age | Aged less than 20 | 3.58% |

| Aged between 21 and 30 | 40.11% | |

| Aged between 31 and 40 | 39.36% | |

| Aged between 41 and 50 | 10.92% | |

| Aged over 50 | 6.02% | |

| Type of company | State-owned company | 56.69% |

| Private company | 42.56% | |

| Other types of company | 0.75% | |

| Years of working experience | Less than 1 year | 10.17% |

| Between 1 and 10 years | 54.43% | |

| Between 11 and 20 years | 26.74% | |

| More than 20 years | 8.66% | |

| Position | Employee without management title | 62.90% |

| Head of department/unit | 33.15% | |

| Senior manager | 3.77% | |

| Other positions | 0.19% | |

| Main working location | Office on construction site or construction site | 68.93% |

| Office at headquarters or branch company | 30.70% | |

| Other working locations | 0.38% |

| Constructs | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR (rho_a) | CR (rho_c) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal factors | 0.916 | 0.943 | 0.935 | 0.705 |

| Work–family factors | 0.928 | 0.950 | 0.943 | 0.735 |

| Environmental factors | 0.955 | 0.958 | 0.962 | 0.759 |

| Depression | 0.946 | 0.922 | 0.956 | 0.758 |

| Anxiety | 0.939 | 0.946 | 0.951 | 0.735 |

| Stress | 0.944 | 0.941 | 0.954 | 0.750 |

| Constructs | PF | WF | EF | Depression | Anxiety | Stress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal factors (PFs) | ||||||

| Work–family factors (WFs) | 0.845 | |||||

| Environmental factors (EFs) | 0.801 | 0.853 | ||||

| Depression | 0.410 | 0.399 | 0.356 | |||

| Anxiety | 0.409 | 0.373 | 0.338 | 0.963 | ||

| Stress | 0.430 | 0.412 | 0.368 | 0.970 | 0.985 |

| Hazards | Mean Value | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| The first dimension: Personal factors (PFs) | 3.121 | - |

| Worrying about being infected with COVID-19 (PF1) | 3.279 | 11 |

| Less sleep due to the pandemic (PF2) | 3.107 | 19 |

| Improper strategies used to cope with the pandemic (PF3) | 2.836 | 20 |

| Reduced exercise due to the pandemic (PF4) | 3.171 | 17 |

| Increased severity of chronic illness and corresponding problems due to the pandemic (PF5) | 3.173 | 16 |

| Personal traits (PF6) | 3.160 | 18 |

| The second dimension: Work–family-related factors (WFs) | 3.371 | - |

| Significantly increased workload due to the pandemic (WF1) | 3.258 | 14 |

| Worrying about relatives being infected with COVID-19 (WF2) | 3.621 | 1 |

| Frequently working overtime due to the pandemic (WF3) | 3.275 | 12 |

| Work–life conflict due to the pandemic (WF4) | 3.181 | 15 |

| Decreased income due to the pandemic (WF5) | 3.480 | 2 |

| Inadequate career development opportunities due to the pandemic (WF6) | 3.409 | 5 |

| The third dimension: Environmental factors (EFs) | 3.351 | - |

| Inadequate care from government departments or employers for minimizing the influence of the pandemic (EF1) | 3.294 | 10 |

| Inadequate epidemic prevention supplies (EF2) | 3.358 | 7 |

| Discrimination due to infection or possible infection with COVID-19 disease (EF3) | 3.269 | 13 |

| A variety of social distancing measures due to the pandemic (EF4) | 3.422 | 3 |

| Too much negative information associated with the pandemic (EF5) | 3.341 | 8 |

| Too much false information associated with the pandemic (EF6) | 3.318 | 9 |

| More personal information reported to government due to the pandemic (EF7) | 3.416 | 4 |

| More nucleic acid tests due to the pandemic (EF8) | 3.386 | 6 |

| Mental Health Level | Depression | Anxiety | Stress | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Respondents | Range of Scale | Percentage of Respondents | Range of Scale | Percentage of Respondents | Range of Scale | |

| Normal | 56.69% | 0–4 | 54.43% | 0–3 | 76.46% | 0–7 |

| Mild | 10.36% | 5–6 | 12.99% | 4–5 | 6.59% | 8–9 |

| Moderate | 17.89% | 7–10 | 13.75% | 6–7 | 5.84% | 10–12 |

| Severe | 4.52% | 11–13 | 4.52% | 8–9 | 6.21% | 13–16 |

| Extremely severe | 10.55% | 14+ | 14.31% | 10+ | 4.90% | 17+ |

| Overall score | 5.023 | 4.612 | 5.365 | |||

| Variables | PF | WF | EF | Stress | Anxiety | Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal factors (PFs) | 1 | |||||

| Work–family factors (WFs) | 0.754 (**) | 1 | ||||

| Environmental factors (EFs) | 0.722 (**) | 0.784 (**) | 1 | |||

| Stress | 0.369 (**) | 0.368 (**) | 0.309 (**) | 1 | ||

| Anxiety | 0.328 (**) | 0.319 (**) | 0.267 (**) | 0.874 (**) | 1 | |

| Depression | 0.344 (**) | 0.343 (**) | 0.277 (**) | 0.874 (**) | 0.827 (**) | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Hon, C.K.H.; Li, H.; Su, Z.; Kang, P. Impact of Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards on the Mental Health Outcomes of Construction Professionals. Buildings 2025, 15, 4339. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234339

Zhang S, Sunindijo RY, Hon CKH, Li H, Su Z, Kang P. Impact of Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards on the Mental Health Outcomes of Construction Professionals. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4339. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234339

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shang, Riza Yosia Sunindijo, Carol K. H. Hon, Haoxiang Li, Zhenwen Su, and Peng Kang. 2025. "Impact of Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards on the Mental Health Outcomes of Construction Professionals" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4339. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234339

APA StyleZhang, S., Sunindijo, R. Y., Hon, C. K. H., Li, H., Su, Z., & Kang, P. (2025). Impact of Pandemic-Induced Psychosocial Hazards on the Mental Health Outcomes of Construction Professionals. Buildings, 15(23), 4339. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234339