1. Introduction

The modernization of educational buildings is essential not only for meeting sustainability targets but also for ensuring healthy, comfortable, and productive learning environments for students and teachers [

1,

2]. In recent decades, renovation strategies have focused primarily on improving operational energy efficiency, especially in nearly zero-energy buildings, has shifted attention to embodied carbon from constru ction materials [

3]. Concurrently, there is growing recognition that indoor environmental quality (IEQ), including IAQ, thermal comfort, lighting, and ventilation, plays a decisive role in occupant health, well-being, and academic performance [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6]. For schools, IAQ is a critical yet often under-prioritized, with mounting evidence linking it to cognitive outcomes and student attendance. Adherence to hygiene norms and recommended IAQ parameters [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] is required in all schools, renovated or not, to ensure safe learning conditions. Recent research calls for renovation strategies integrating environmental impact reduction with occupant-centered performance evaluation, ensuring that sustainability goals are met without compromising student health and learning conditions.

Elevated indoor carbon dioxide (CO

2) concentrations are well-established indicators of inadequate classroom ventilation, linked to impaired decision-making, lower academic performance, and increased absenteeism [

1]. Children are particularly vulnerable due to developing respiratory systems and higher breathing rates [

4]. Studies show that sustained CO

2 levels above 1000–1500 ppm significantly harm concentration, memory, and attendance [

12], with children reporting “stuffy” air when CO

2 exceeds ~1450 ppm [

13]. The COVID-19 pandemic further increased IAQ monitoring and ventilation improvements in schools [

1,

14]. While mechanical ventilation reduces pollutants effectively [

15], naturally ventilated classrooms remain vulnerable to outdoor air quality and inconsistent occupant behavior. Artificial intelligence models suggest optimal IAQ parameters for learning are CO

2 between 600–700 ppm, RH of 55–65%, and airflow of 0.32–0.40 m/s [

16]. Differences between urban and rural schools in building features and pollutant exposure affect comfort perceptions, prompting calls for tailored, multi-dimensional IEQ assessment [

17].

Natural ventilation relies on manual window opening, reducing CO

2 in warmer months but introduces outdoor pollutants and discomfort in cold seasons. Díaz et al. (2021) [

18], and Jo et al. (2024) [

2] reported degraded IAQ during the heating season in naturally ventilated classrooms, with elevated CO

2 linked to reduced cognitive performance. Similarly, Kanama et al. (2023) [

19] found that balanced mechanical ventilation with filtration lowered CO

2, but unexpectedly increased infiltration of outdoor PM

2.

5. Behavioral aspects, such as teacher and student window-opening practices, also affect ventilation effectiveness, while occupant control enhances comfort and IAQ [

3,

20]. These findings underscore the need for site-specific, seasonally adaptive ventilation strategies minimizing pollutant ingress.

School renovation efforts across in Europe prioritize energy efficiency, thermal comfort, and IAQ, guided by EU policies like the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) [

21]. Studies report IAQ-focused renovations improve academic outcomes, for instance, Stafford et al. (2015) [

22] found gains in math and reading scores following mold remediation and ventilation upgrades, while Zaeh et al. (2021) [

23] showed that combined ventilation and envelope upgrades reduce CO

2, PM

2.

5, and CO. However, not all renovations yield positive IAQ outcomes. Emissions from new materials can worsen air quality, as seen in Korean schools [

24], while Jovanović et al. (2014) [

25] reported high pollutant levels in Serbian schools, due to outdated materials and heating systems. Positive results also come from EPBD-compliant retrofits that shows improved occupant satisfaction [

26], and deep retrofits in Denmark and Italy achieved energy savings of 75–80% while maintaining or improving IEQ [

27,

28]. However, Stocker et al. (2015) [

29] note that building age, design, and climate critically influence renovation outcomes. Overall, renovations can enhance IAQ, thermal comfort, and energy efficiency [

30], but outcomes vary depending on design quality, ventilation strategy, material selection and local context.

The integration of life cycle assessment (LCA) aids environmental decision-making in school buildings with growing emphasis on embodied carbon from life cycle stages A1–A3 (A1: raw material extraction and processing. A2: transportation to manufacturing site. A3: manufacturing of building products.). Arena et al. (2003) [

31] showed that design strategies can reduce operational energy use but may have trade-offs, such as increased ozone formation. Deng et al. (2021) [

32] found that IEQ factors affect student health and absenteeism differently across heating and non-heating seasons, demonstrating the need for season-specific analyses. Material production stages can be significant contributors to total emissions, and design choices and low-carbon material selection matter considerably [

30,

33,

34]. Research by Pachta et al. (2022) [

35] identified material impact differences but often neglected seasonal IAQ effects. Ruth et al. (2025) [

5] confirm IAQ is frequently the most influential comfort factor, though thermal, visual, and acoustic parameters vary seasonally. Seuntiens et al. (2024) [

36] observed ventilation systems can produce higher material impacts than operational energy, yet IAQ is rarely measured alongside environmental impacts. Perceived control over classroom environments can enhance both comfort and IAQ perception, enabling potential energy savings through lower heating setpoints [

37].

Greer et al. (2025) [

38] and Mohebbi et al. (2021) [

39] argue for integrating IAQ and embodied carbon assessment in educational building renovations, Jaemoon et al. (2023) [

34] report that in high-performance or nearly zero-energy buildings, A1–A3 stages can account for 30–50% of total greenhouse gas emissions. They highlight the role of LCA tools, such as One Click LCA, SimaPro, G-SEED, and LEED modules, in identifying high-impact materials, selecting low-carbon alternatives [

34,

40]. Kempton et al. (2022) [

41] caution that airtightness strategies may reduce operational carbon yet risk degrading IAQ without sufficient ventilation. Galimshina et al. (2019) [

42] propose integrating LCA with Life Cycle Costing (LCC) and uncertainty analysis to balance environmental and economic outcomes. Simultaneous consideration of IAQ and embodied carbon is essential because renovation strategies optimizing one dimension may compromise the other; increased airtightness reduces operational energy but can degrade IAQ, while material-intensive upgrades improve comfort but increase upfront carbon emissions [

23]. Integrated assessment enables optimization of both health and environmental outcomes [

19,

43].

Despite extensive research on school IAQ and renovation, three critical gaps persist:

- a.

First, most studies compare different school types or locations rather than architecturally identical schools differing only by renovation status [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], making it difficult to isolate renovation effects from confounding factors.

- b.

Second, few studies analyze seasonal IAQ variation during the heating-to-cooling transition period, though this phase is critical for understanding how ventilation and envelope performance interact dynamically.

- c.

Third, IAQ and embodied carbon evaluation are rarely integrated in a single empirical study, limiting understanding of health–environment trade-offs.

This study addresses all three gaps simultaneously through controlled comparison, seasonal monitoring, and integrated assessment.

This research compares two architecturally identical schools in the same suburb (~100 m apart), one renovated, one non-renovated, across heating-to-cooling season transition period. The study combines field measurements of IAQ parameters (CO2 concentration, temperature, and relative humidity) with LCA of building materials for stages A1–A3. The IAQ data (211,417 observations at 10-min intervals) are statistically analyzed for seasonal and renovation-related differences, while the LCA quantifies embodied carbon. The primary aim is to evaluate how energy-efficiency renovation influences both IAQ and embodied carbon. Specifically, the objectives are:

- (i)

to analyze differences in CO2 concentration, temperature, and RH between the two schools across seasons and school time;

- (ii)

to assess the embodied carbon of renovation materials through LCA of stages A1–A3.

The hypothesis of this research is that renovation improves thermal stability but does not necessarily guarantee IAQ compliance, while introducing additional embodied carbon. Regardless of renovation status, IAQ must remain within hygiene norms, national and international guidelines [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. By integrating field IAQ measurements with LCA, the study provides direct, evidence-based comparison of renovation impacts on indoor conditions and embodied emissions.

This study makes three distinct technical contributions:

First, it employs controlled comparative design, directly comparing architecturally identical schools differing only in renovation status, minimizing confounding variables [

19,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

Second, it delivers high-resolution seasonal analysis, capturing the transition period with 211,417 observations at 10-min intervals, revealing IAQ variations masked in shorter studies.

Third, it provides integrated IAQ-LCA, simultaneously evaluating indoor quality and embodied carbon to address occupant health and sustainability within a single framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. School Selection Criteria

Two architecturally identical schools, located in the same suburb within Kaunas County, Lithuania, were selected for this study. The schools share the same building shape, layout, and original construction year; however, one has undergone major energy-efficiency renovation (“renovated school”), while the other remains in its original, non-renovated state (“non-renovated school”). The exact city and suburb are not disclosed to maintain the anonymity of the schools, as agreed with the school authorities. Selecting buildings in the same location ensured similar outdoor environmental conditions (temperature, precipitation, air pollution, traffic), to minimize local climate influence on indoor air quality. Both schools accommodate students of the same age group, thereby reducing variability in indoor conditions that could arise from differences in student behavior or schedules.

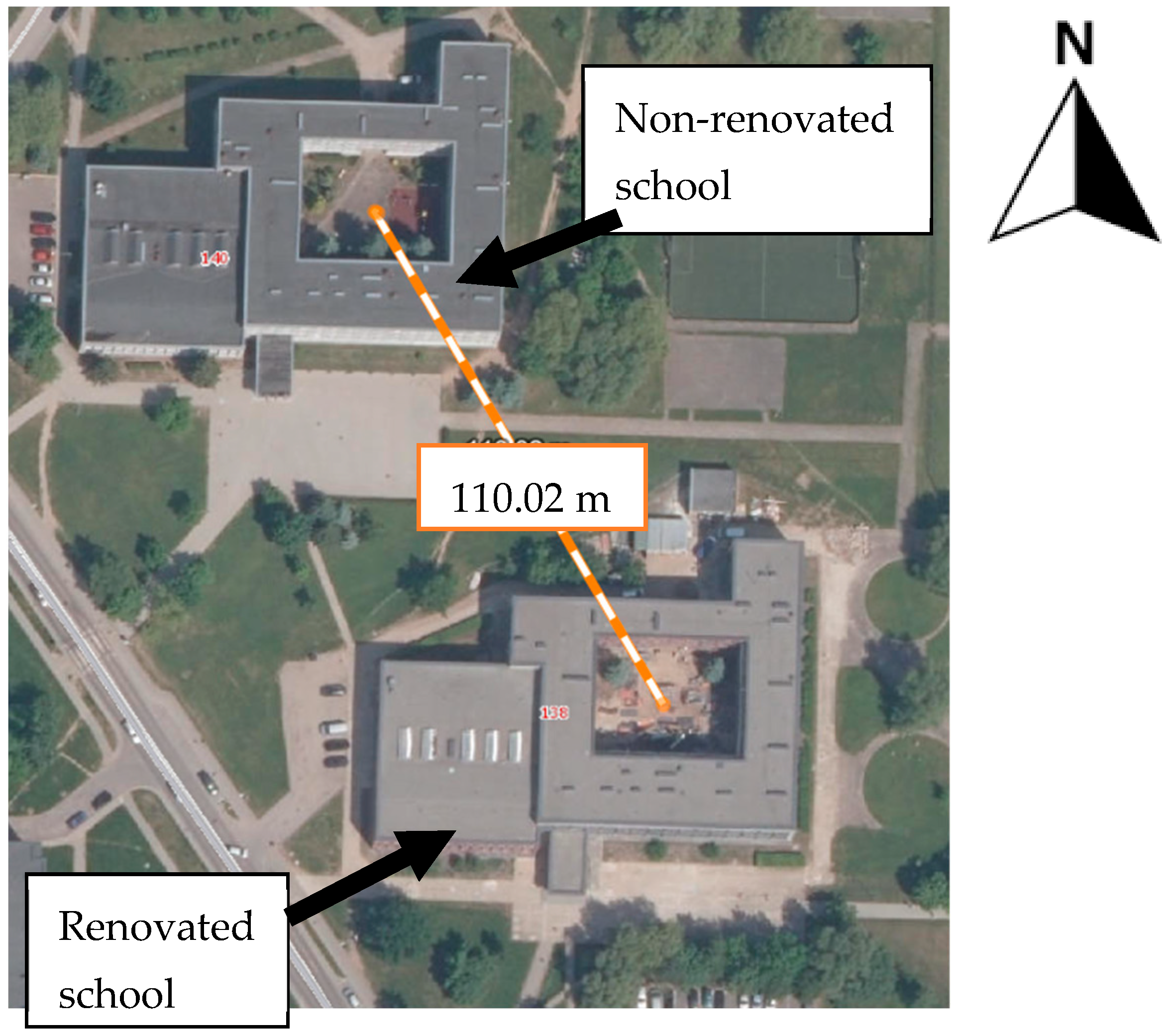

Both schools are situated within the same suburb, separated by less than 115 m (

Figure 1). This guarantees equivalence in outdoor climatic exposure, urban traffic density, local air quality sources, and neighborhood context—conditions that can strongly affect IAQ but are rarely controlled by observational research. With outdoor environment held constant, observed differences can be confidently attributed to renovation status rather than external influences.

This study did not involve the collection of any personal data, and thus did not require formal ethical review.

Lithuania’s climate is classified as warm-summer humid continental (Köppen Dfb), characterized by cold winters, moderate to warm summers, and significant seasonal temperature fluctuations [

44,

45,

46]. These conditions set a challenging context for both heating demand and natural ventilation, directly influencing indoor air quality and occupant comfort in school buildings.

Depth of observation is maximized. Over 61 consecutive days, data were collected continuously (211,000+ data points) from six classrooms (three in each school), providing rich intra-building and day-to-day patterns, occupancy effects, and season transitions. This granularity is critical for understanding not just average IAQ, but the real-time dynamics most relevant to occupant health and comfort—insights that are often missed in studies limited to cross-sectional or spot measurements.

The measurements were conducted during a transitional spring period from 29 March to 29 May 2024 at a school located in the Kaunas region, capturing both heating-season and cooling-season dynamics. During the heating season (29 March–25 April), outdoor temperatures remained relatively cold with a mean of 6.2c, while the cooling season (26 April–29 May) corresponded with rising temperatures averaging 15.3 °C [

47,

48]. Across the entire period, outdoor temperatures ranged from −1 °C to 21 °C (mean = 10.7 °C, SD = 4.7 °C) and relative humidity ranged between 45% and 95% (mean = 71%, SD = 11%). Precipitation totaled 42 mm, with most rainfall in late April and early May [

47,

48]. This transitional period was strategically valuable for observing both heating-phase dynamics (windows closed, reliance on envelope performance) and cooling-phase behaviors (natural ventilation via window opening), allowing identification of ventilation and envelope effects under real-world operational conditions.

Finding identical renovated and non-renovated pairs is rare. This opportunity thus represents a natural experiment unlikely to be reproducible once the non-renovated school is upgraded.

2.2. Permissions and School Collaboration

School authorities were contacted to arrange field studies. They agreed to participate on the condition that the school names would remain anonymous to avoid reputational risks if IAQ recommendations were not met. The schools were therefore coded as School 1 (renovated) and School 2 (non-renovated).

2.3. IAQ Monitoring Setup

Indoor air temperature, CO

2 concentration, and relative humidity were monitored using COMET dataloggers (

Figure 2). Data was recorded in non-volatile memory and transferred to a PC via USB-C using COMET Vision software (Version 2.3) [

49]. Each device includes a traceable calibration certificate in accordance with EN ISO/IEC 17,025 standards [

49].

Sensor Specifications [

49]:

Temperature sensor: Range −20 °C to +60 °C; Accuracy ±0.4 °C; Resolution 0.1 °C.

Humidity sensor: Range 0–100% RH; Accuracy ±1.8% RH; Resolution 0.1% RH.

Dew point: Range −60 to +60 °C; Accuracy ±1.5 °C (T < 25 °C and RH > 30%); Resolution 0.1 °C.

CO2 sensor: Range 0–5000 ppm; Accuracy ±(50 ppm + 3% of reading) at 25 °C and 1013 hPa; Resolution 1 ppm.

Recording interval: Adjustable from 1 s to 24 h.

Memory capacity: 500,000 values (noncyclic); 350,000 values (cyclic).

Power source: Li-Ion battery A8200, 3.6 V/5200 mAh.

Protection class: IP20.

Dimensions: 61 × 93 × 53 mm; Weight: approx. 250 g.

Sensors were installed at approximately 1.1 m above floor level, close to the breathing zone of seated students, to ensure representative measurements of the occupied zone. Placement near windows, doors, or heating devices was avoided to reduce the influence of drafts, solar radiation, or localized heat sources. Sensor locations were determined by school authorities. There were several criteria for dataloggers placement:

Minimum 2–3 m from external windows to minimize direct outdoor air influence and solar radiation effects.

Minimum 1.5 m from classroom doors to avoid corridor air drafts during door opening.

Minimum 2 m from radiators or heating equipment to prevent localized temperature/humidity plumes.

Exact placement varied between classrooms, dictated by furniture configurations, electrical outlet access, and spatial constraints. All installations met above criteria, reflecting realistic limitations of monitoring in occupied, operational buildings. This variability is not expected to affect results materially, as IAQ standards apply throughout classroom spaces and buildings.

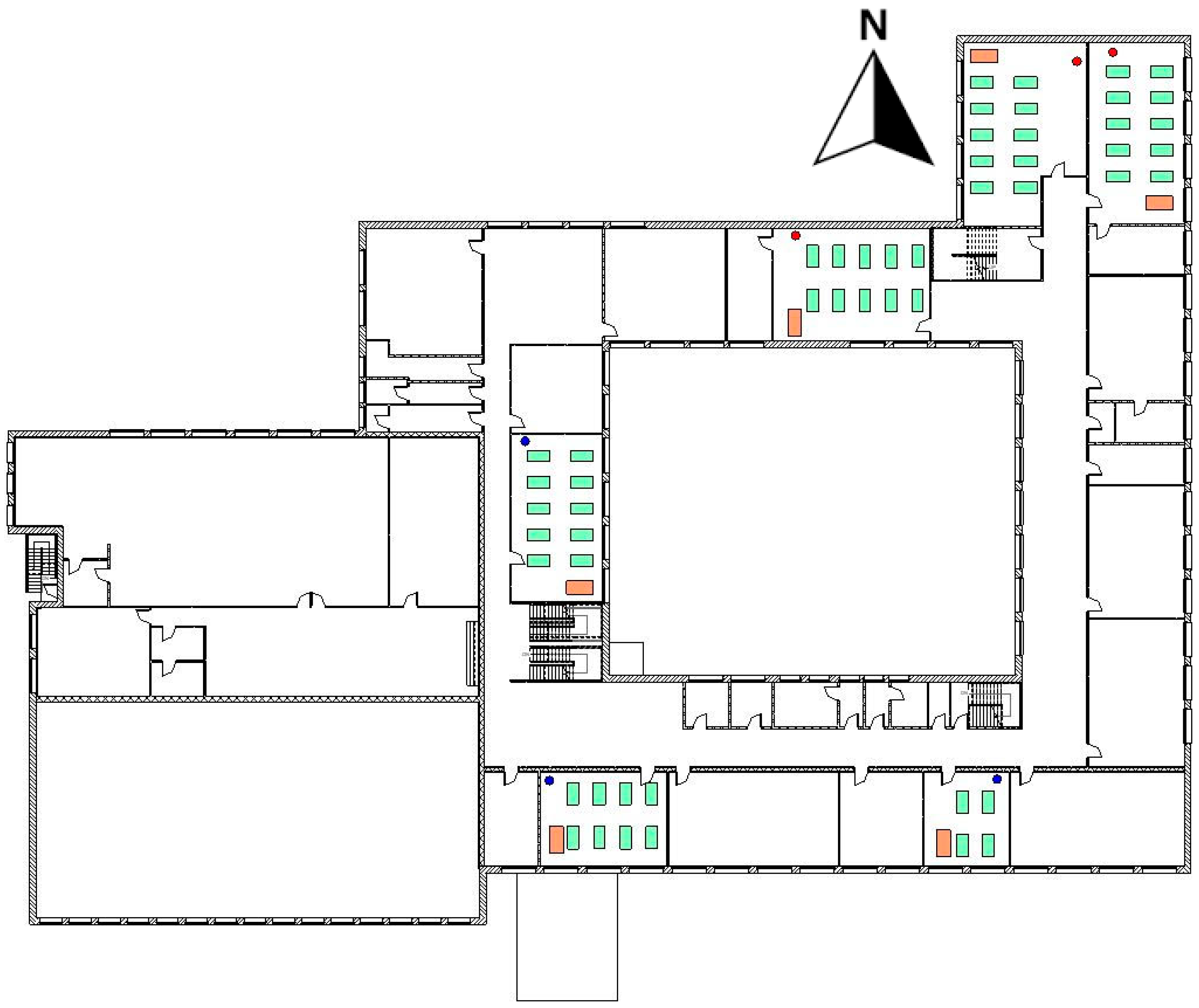

Figure 3 presents a schematic plan of the first floor of the school. Since both schools share the same layout and structure, only one floor plan is shown. On the plan, light green rectangles represent double student desks, while light orange rectangles represent single teacher desks. The figure also illustrates the approximate locations of the sensors in both schools. Red dots indicate the locations of the data loggers in the non-renovated school, while blue dots show their locations in the renovated school. Red and blue dots are also shown in 3D model of school (

Figure 4).

No sensors were placed on the ground floor. In each school, two sensors (four in total) were installed on the first floor, and one sensor per school (two in total) was installed on the second floor. Because the first and second floors share the same layout, the authors chose to show only the first-floor plan with the locations of the data loggers. Classroom layouts with desks/tables are shown only for the classrooms where data loggers were installed, as other rooms were not relevant. A north arrow is also included in

Figure 3.

2.4. Monitoring Period and Seasonal Division

Measurements were carried out from 29 March 2024 (10:00) to 29 May 2024 (14:00). The heating season ended on 25 April 2024, after which the cooling season began on 26 April 2024. This two-season approach ensured the capture of IAQ variations under different ventilation and heating/cooling regimes.

For the analysis, the dataset was further divided based on school occupancy patterns. Since exact classroom occupancy data (the number of people present) was not available, an additional variable was created in SPSS (version 29) to distinguish between school/lesson time and non-school time instead of using “occupied” and “unoccupied.” Time intervals between 8:00 and 15:00 (Monday–Friday) were coded as school/lesson time, while periods outside this range, including evenings, nights, and weekends, were classified as non-school time. Within school hours, lessons and breaks were separated into two different categories to capture IAQ variations more precisely. These time-based clusters formed the basis of the statistical analyses, with results presented in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

2.5. Building Documentation and 3D Modelling

Following the start of monitoring, schools provided building floor plans and cadastral files. Additional construction material information was obtained from Lithuania’s Registry Centre. These data were used to create accurate 3D models of both schools, enabling a visual comparison of architectural similarity and serving as input for Life Cycle Assessment modelling.

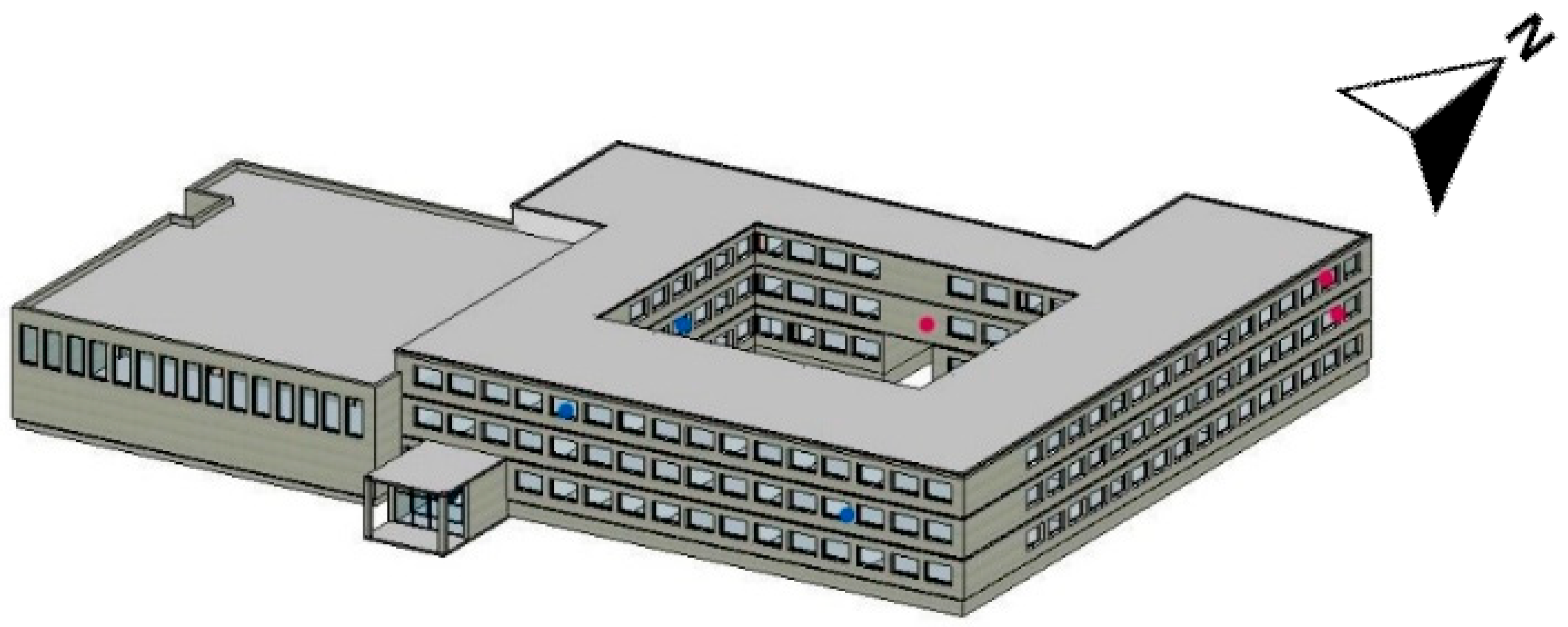

Because both schools share the same architectural layout, one being renovated and the other non-renovated, the authors chose to present only one 3D model for visual illustration. The non-renovated school was selected for this purpose, as its representation clearly reflects the original building configuration used as a reference in this study. The 3D representation shown in

Figure 4 was prepared by the authors based on the documentation provided by the schools.

2.6. Life Cycle Assessment

A comparative Life Cycle Assessment was conducted using OneClick LCA (Version 0.46.4) [

50] software to quantify the embodied carbon impacts of different renovation strategies for the case study school building. The functional unit was defined as the entire school building, enabling consistent comparison across scenarios. The analysis focused on the product stage modules A1–A3 of the building life cycle in accordance with EN 15978 [

51]:

A1: Raw material supply.

A2: Transportation.

A3: Manufacturing.

The scope was limited to stages A1–A3 because the main objective of this study was to capture the embodied carbon of the additional renovation materials. These stages cover raw material supply, transport, and manufacturing, which are generally recognized as important contributors to the embodied emissions of building products. Later stages of the life cycle, such as construction (A4–A5), use phase (B1–B7), and end-of-life (C1–C4), were not included, as they often require more detailed building-specific data and assumptions that were beyond the scope of this study.

For the modelling, three scenarios were created. The first scenario was the non-renovated school, which served as the baseline, and renovation materials were added to simulate the second version, the renovated school version. The third scenario was a renovated school with eco-materials, the substitution of conventional products with lower-impact alternatives. LCA inputs were derived from the 3D models and material data applicable here, default service life values embedded in OneClick LCA were applied. For comparability, operational conditions were assumed to be identical across scenarios, and only material differences were considered. The environmental impact factors were taken from OneClick’s integrated Ecoinvent and Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) databases [

50]. The main impact category reported is Global Warming Potential (GWP), expressed in CO

2 equivalents (CO

2e).

The goal of the LCA was to assess and compare the embodied product stage emissions (A1–A3) of renovation materials versus the baseline structure, and to evaluate whether eco-materials can mitigate the additional impacts introduced by renovation.

2.7. Data Preparation and Statistical Analysis

Sensor data were first exported into Microsoft Excel and then imported into IBM SPSS Statistics [

52] for analysis. The dataset consisted of 211,417 observations, collected at 10-min intervals across six classrooms (three per school), recording temperature, relative humidity, CO

2, and dew point.

Variables included timestamp information (date, hour, minute, weekday), season (heating vs. cooling), school type (renovated vs. non-renovated), classroom ID, measured values, school time category (lesson vs. no lesson), and outdoor temperature and RH. Data were cleaned to address formatting inconsistencies—over 200,000 outdoor readings required conversion from string to numeric format—and missing values were handled using listwise or pairwise exclusion depending on the analysis type to maintain statistical robustness.

Several statistical techniques were applied to examine and compare IAQ conditions across the two school buildings and under different operational conditions. Descriptive statistics summarized distributions and variation in CO

2, temperature, and relative humidity across seasons, school types, and occupancy periods. Threshold breach analysis quantified the frequency of exceedances above recommended standards using binary flags based on EU and US guidelines [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], detailed threshold definitions and flagging criteria are presented in

Section 3.2. Independent-samples

t-tests compared mean IAQ values between renovated and non-renovated schools. Mixed ANOVA accounted for repeated measurements within classrooms and tested for interaction effects between renovation status and school time (lessons vs. breaks), with renovation status as the between-subjects factor and season and school time as within-subjects factors. Correlation analysis explored linear relationships between IAQ parameters, and k-means cluster analysis was used to identify typical classroom profiles based on IAQ characteristics, grouping classrooms into distinct operational patterns.

Statistical analyses employed mixed ANOVA and independent-samples

t-tests rather than full multilevel (hierarchical linear) modeling, despite the nested data structure (observations within classrooms within schools). This approach was justified by several considerations: firstly, with only two schools, between-school random effects cannot be estimated reliably, as such models typically require 20–30 level-3 units for robust variance component estimation [

53,

54]. Secondly, school-level effects would be confounded with renovation status in this design [

55,

56]. Thirdly, the study’s analytic focus centered on fixed effects (renovation, season) rather than variance partitioning. As a robustness check, hierarchical models nesting measurements within classrooms and schools were estimated with renovation status as a school-level predictor; these results mirrored the ANOVA findings, confirming stability of conclusions across analytic approaches [

57].

3. Results

This section presents the measured indoor air quality conditions, including carbon dioxide, temperature, and relative humidity across different groupings. Figures and tables summarize the measurements, with no interpretation or comparison to literature.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

This subsection summarizes the central tendency and variability of IAQ parameters (CO2 concentration, temperature, and relative humidity) across the study’s primary groupings: indoor–outdoor comparison, renovation status, seasons, and occupancy periods. Descriptive statistics provide an overview of overall patterns before statistical testing.

3.1.1. Indoor vs. Outdoor Conditions

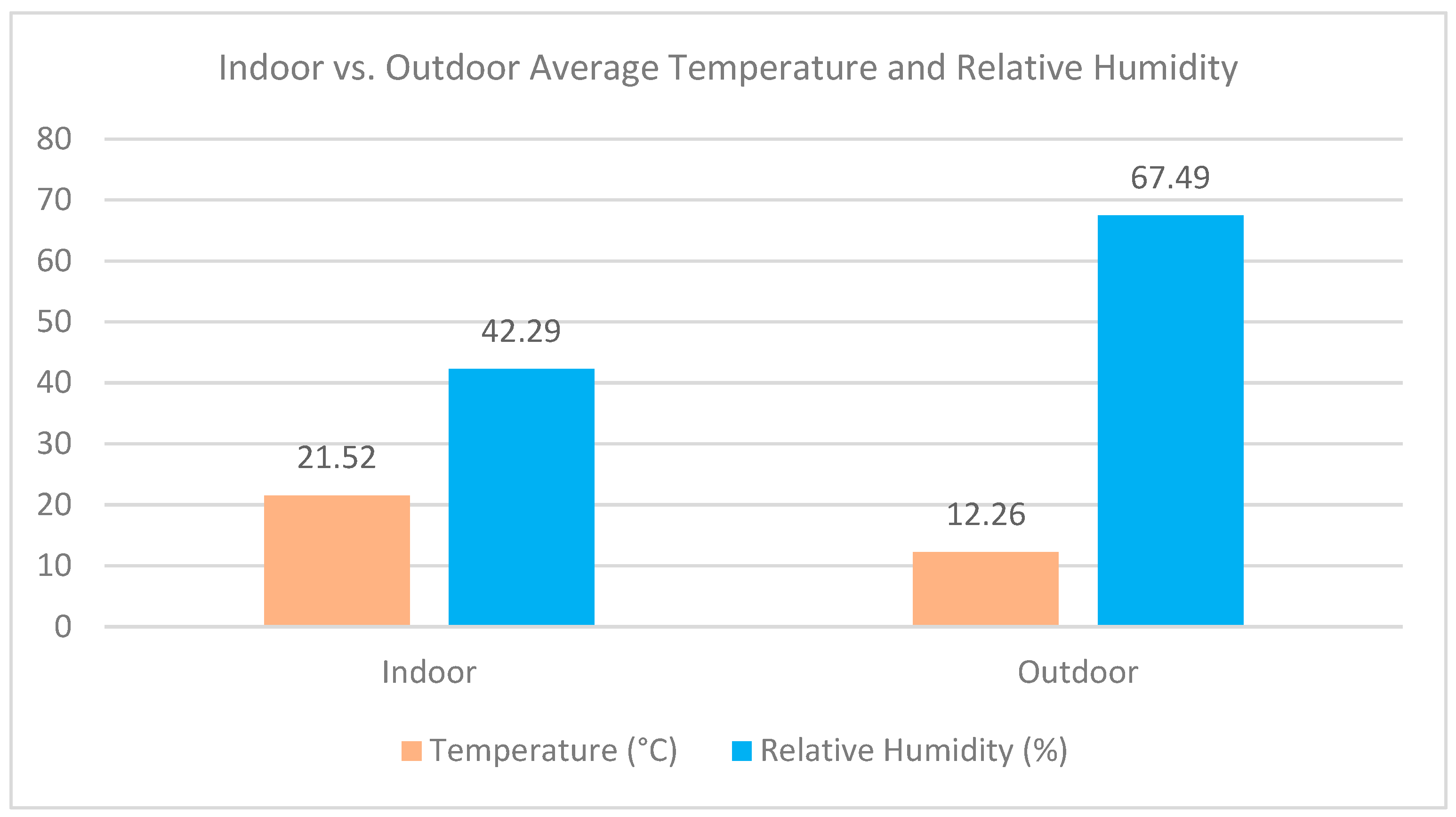

Indoor conditions were notably moderated compared to outdoor extremes across the measurement period (

Table 1,

Figure 5). Indoor temperatures averaged 21.5 °C, approximately 9 °C higher than outdoor conditions, while indoor RH was 42.3%, roughly 25% lower than outdoors. This moderation reflects the protective function of building envelopes in stabilizing interior environments, though more detailed seasonal and occupancy-specific patterns are examined below.

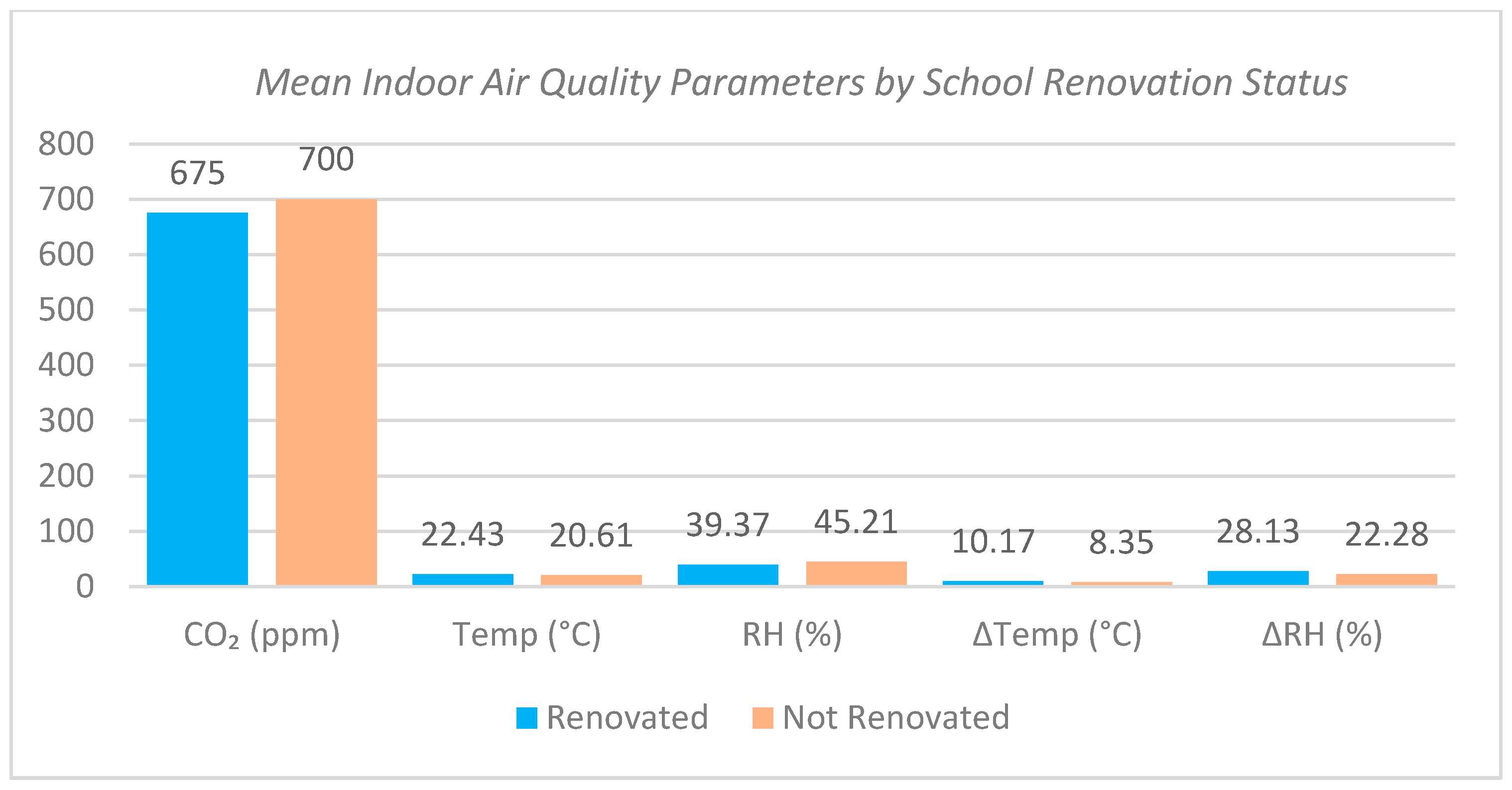

Renovation status influenced all three measured parameters (

Table 2,

Figure 6). Renovated classrooms recorded lower CO

2 concentrations (675 vs. 700 ppm), warmer temperatures (22.43 vs. 20.61 °C), and lower relative humidity (39.37 vs. 45.21%). Beyond mean differences,

Figure 3 illustrates that renovated schools exhibited narrower distributions for temperature and relative humidity, suggesting more stable thermal conditions. The smaller standard deviations in renovated schools (temperature SD = 1.48 °C vs. 2.08 °C; RH SD = 1.89% vs. 3.00%) confirm reduced variability, likely reflecting improved envelope performance and reduced infiltration.

3.1.2. Seasonal and Occupancy Patterns

Occupancy patterns strongly influenced IAQ conditions (

Table 3). CO

2 concentrations nearly doubled during lessons and breaks (1061–1148 ppm) compared to unoccupied periods (588 ppm), exceeding the 1000 ppm threshold during school hours. This confirms occupancy as the primary driver of CO

2 accumulation. Temperature and RH remained relatively stable across occupied periods, but indoor–outdoor differentials (ΔTemp and ΔRH) showed greater variability during non-school time, indicating closer coupling with outdoor conditions when ventilation practices and internal gains were minimal.

Season significantly affected IAQ parameters (

Table 4). During the heating season, CO

2 concentrations averaged 81 ppm higher than in the cooling season, while RH increased by 3.26%. Indoor temperatures were 3.36 °C lower in winter. These patterns reflect reduced natural ventilation during cold weather: windows remained closed to conserve heat, limiting air exchange and allowing CO

2 and moisture accumulation. Conversely, the cooling season showed lower CO

2 and RH alongside higher temperatures, suggesting more frequent window opening. Although window behavior was not directly monitored, the data strongly indicate that seasonal ventilation practices dominated IAQ variation.

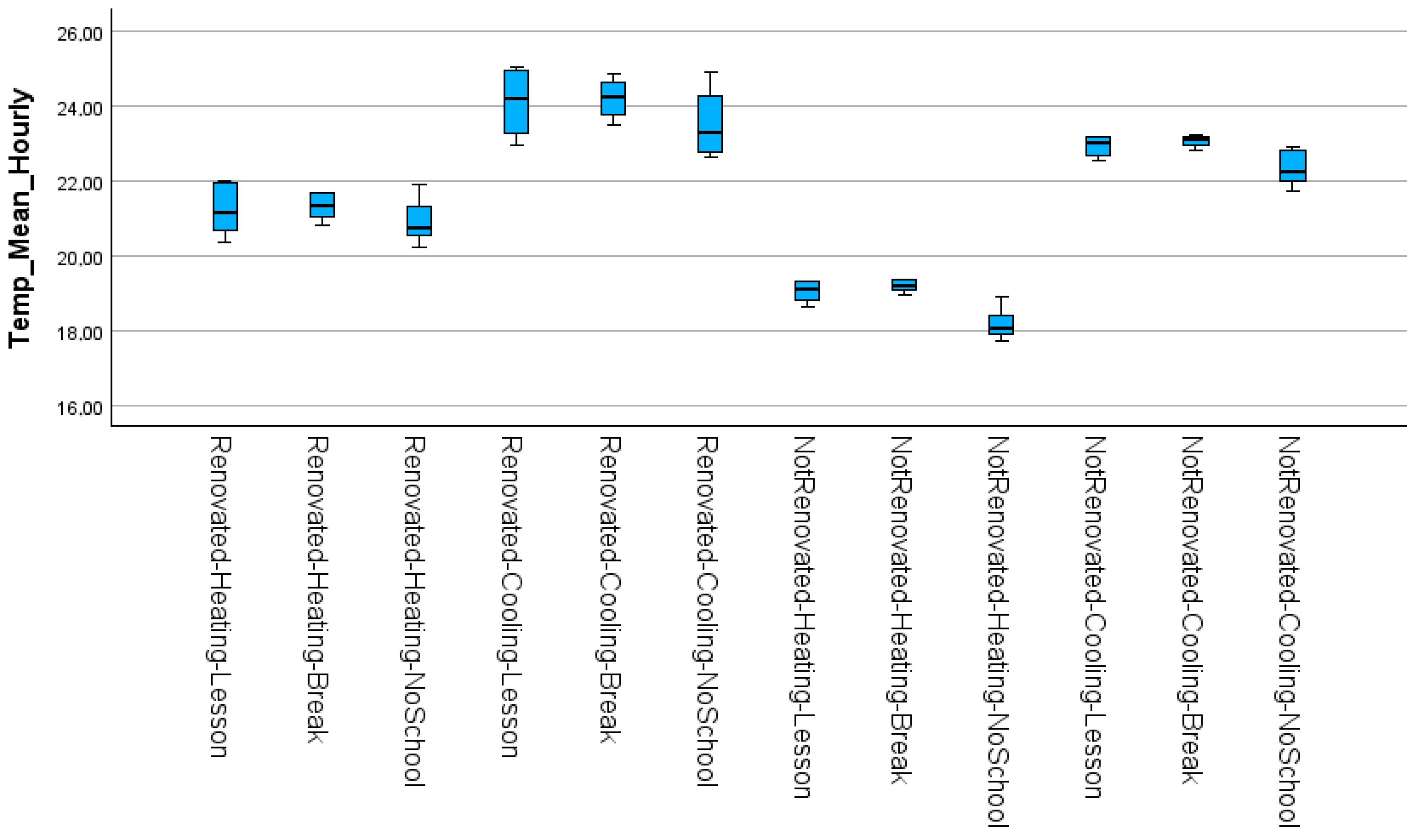

Figure 4 illustrates classroom temperature distributions by season, activity, and renovation status. During the heating season, renovated schools maintained median temperatures around 21 °C, closely aligned with recommended comfort ranges (20–22 °C), while non-renovated schools showed medians near 19 °C, frequently approaching or falling below acceptable thresholds. During the cooling season, renovated schools exhibited slightly elevated temperatures (median ~24 °C), generally remaining within the 23–26 °C guideline, whereas non-renovated schools showed medians around 23 °C. Overall, renovated schools demonstrated greater thermal stability across activities, while non-renovated buildings displayed larger seasonal contrasts, particularly during winter. These patterns confirm that renovation improves alignment with international thermal comfort standards [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

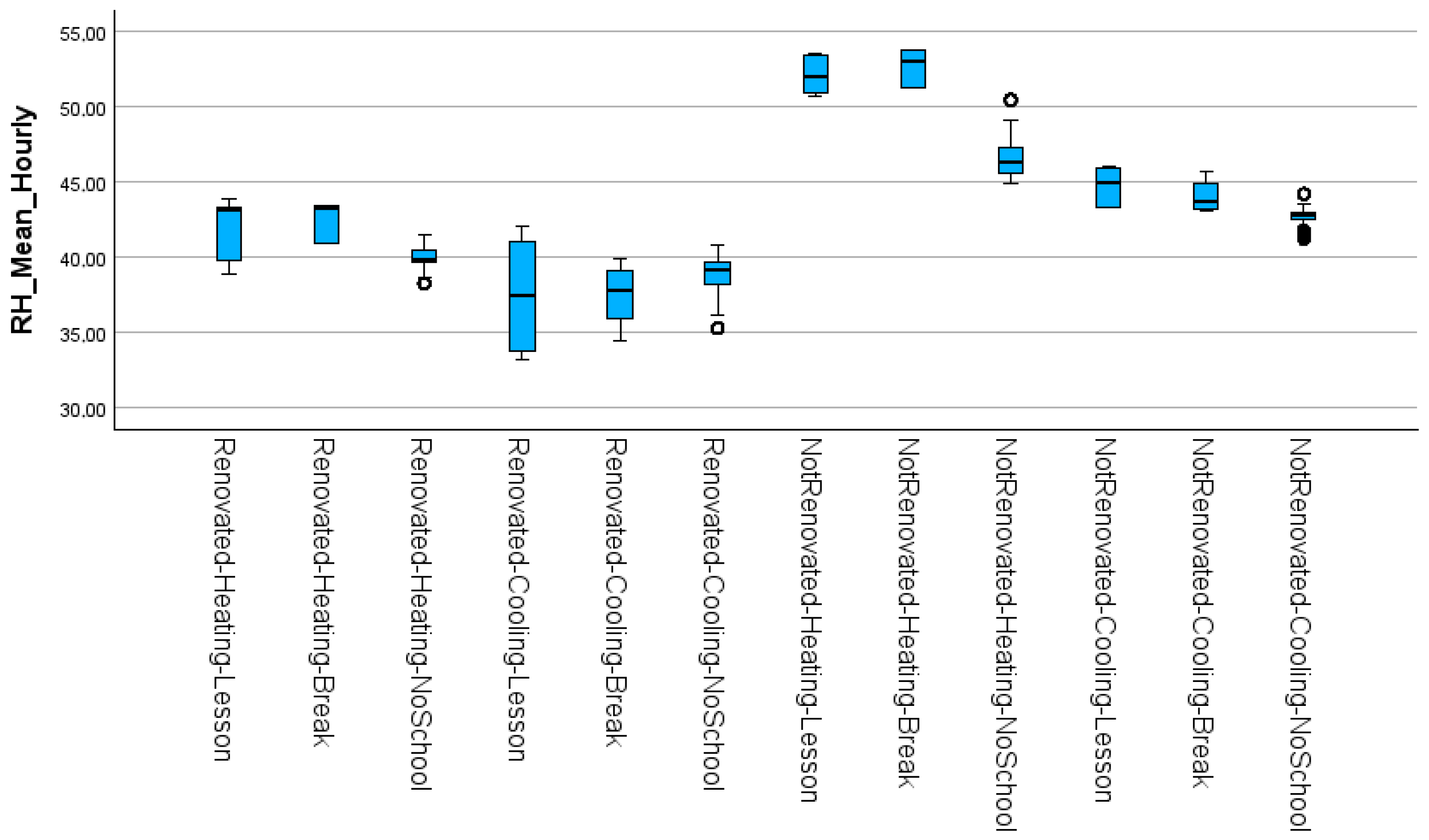

Figure 8 displays RH distributions across the same groupings. In renovated schools, heating-season RH clustered around 40–43%, remaining comfortably within the 30–60% range, while cooling-season values decreased slightly to 37–40%. Non-renovated schools showed consistently higher RH during winter (medians 50–52%), approaching upper comfort boundaries, with somewhat lower levels in summer (43–46%). Without mechanical ventilation in either school type, these differences reflect envelope performance and infiltration characteristics. Renovation reduced humidity and increased seasonal variability, whereas non-renovated schools retained more moisture during heating periods. All measured values remained within acceptable international thresholds [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

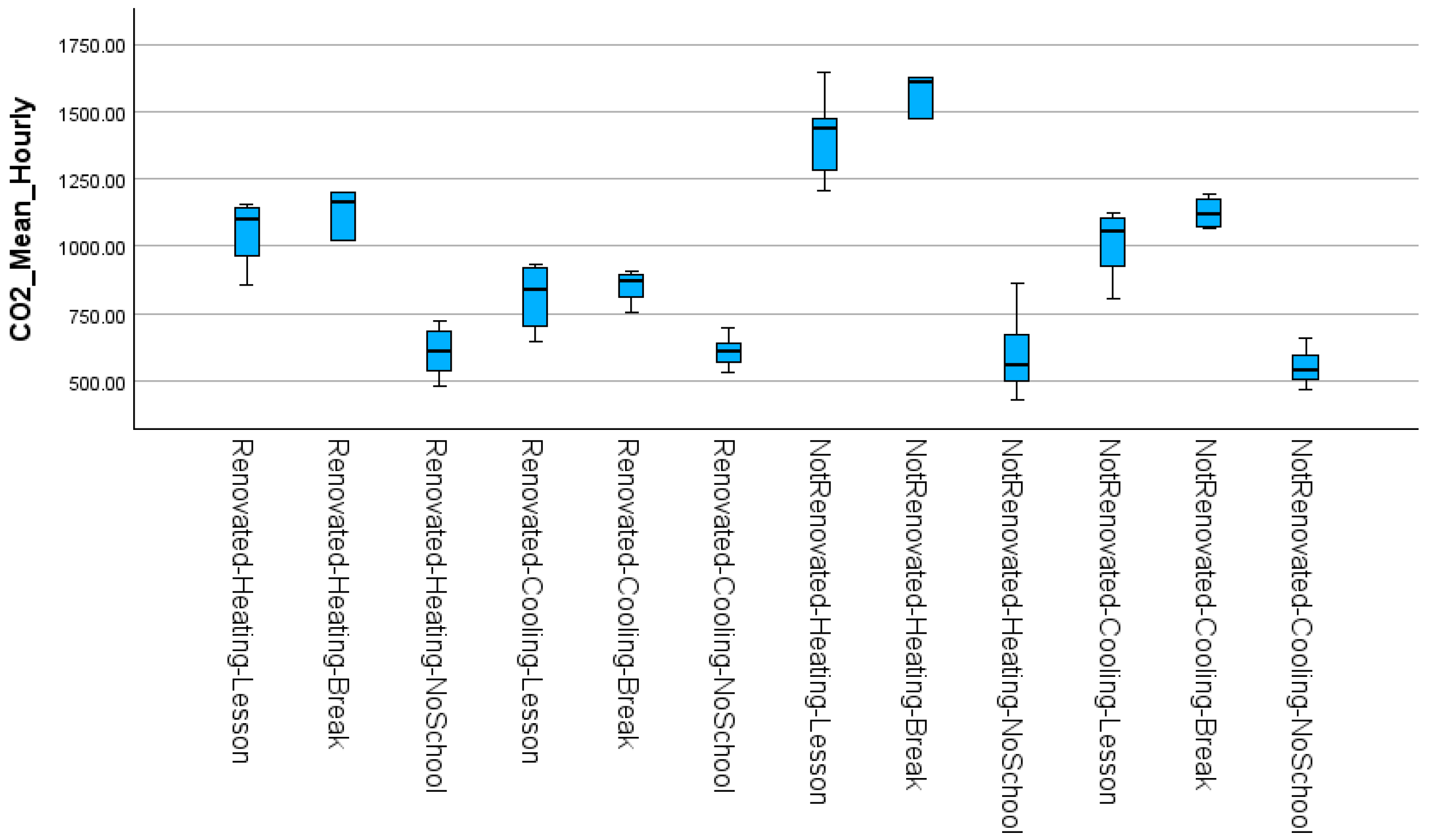

Occupancy patterns exerted strong influence on CO

2 concentrations (

Figure 9). During lessons, median values frequently exceeded 1000 ppm, with non-renovated schools approaching 1500 ppm in the heating season when window ventilation was minimal. Break periods showed slight reductions, indicating limited air renewal, but concentrations remained above guidelines [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], suggesting that short breaks provided insufficient time for full air exchange. In contrast, unoccupied periods consistently remained near outdoor background levels (500–700 ppm) in both school types, highlighting occupancy as the dominant driver of CO

2 accumulation. While renovated schools recorded lower concentrations than non-renovated buildings, neither maintained guideline compliance (≤1000 ppm) during lessons without mechanical ventilation. CO

2 levels during lessons were approximately 80% higher than during non-school time.

3.1.3. Relationships Among Parameters

These descriptive patterns align with subsequent significance testing. Independent

t-tests and mixed ANOVA (

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.5) confirm statistically significant differences between schools, seasons, and occupancy categories. Correlation analyses (

Section 3.4) further explain these interactions: indoor temperature and RH were strongly negatively correlated (renovated: r = −0.726; non-renovated: r = −0.641,

p < 0.001), while indoor temperature was moderately coupled with outdoor temperature (r = 0.593 and r = 0.537). CO

2 concentrations showed only weak associations with outdoor climate, reinforcing that occupancy and ventilation practices dominate IAQ variation.

A key limitation is that active ventilation behavior (such as window opening or door use) was not systematically tracked during the study. While CO2 reductions during the cooling season and correlations with outdoor temperature suggest that windows were more frequently opened in warmer periods, this inference remains indirect. Without direct behavior monitoring, the independent effects of occupant actions and the building envelope cannot be fully disentangled. Future research should incorporate direct window-position sensors or activity logging to precisely distinguish mechanical from occupant-driven IAQ changes.

Looking at all of the results combined, it shows that occupancy drives sharp thermal comfort and CO2 fluctuations, pushing CO2 above recommended thresholds during school hours. Seasonal effects exacerbate problems in winter, when closed windows limit air exchange, and while renovation improves thermal and RH stability, it alone cannot ensure healthy IAQ without complementary ventilation strategies.

3.2. Threshold Breaches

This section presents the frequency of indoor air quality threshold exceedances for carbon dioxide, temperature, and relative humidity across the monitored schools. Results are grouped by renovation status, season (heating vs. cooling), and school time (lesson, break, no school). Thresholds and flag conditions used to identify exceedances are presented in

Table 1.

Threshold definitions and flagging criteria: To evaluate compliance with IAQ standards, thresholds were established based on EU and US guidelines [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], ensuring comparability with international standards. Several binary flags were created to identify when measured values exceeded recommended ranges (

Table 1). For CO

2, the ideal concentration is ≤1000 ppm with a maximum acceptable level of 1500 ppm; values exceeding 1500 ppm were flagged as high. For temperature, seasonal thresholds reflect different thermal comfort expectations: during the heating season, the recommended range is 20–22 °C with 18–22 °C considered tolerable, while during the cooling season, 23–26 °C is recommended with up to 27 °C tolerable. Temperatures falling below or exceeding these ranges were flagged accordingly. For relative humidity, the optimal range is 30–60% with 20–70% considered acceptable; values below 30% or above 60% were flagged. These thresholds align with European Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) requirements and Lithuanian STR standards for school buildings, providing a robust framework for assessing compliance.

3.2.1. CO2 Threshold Breaches

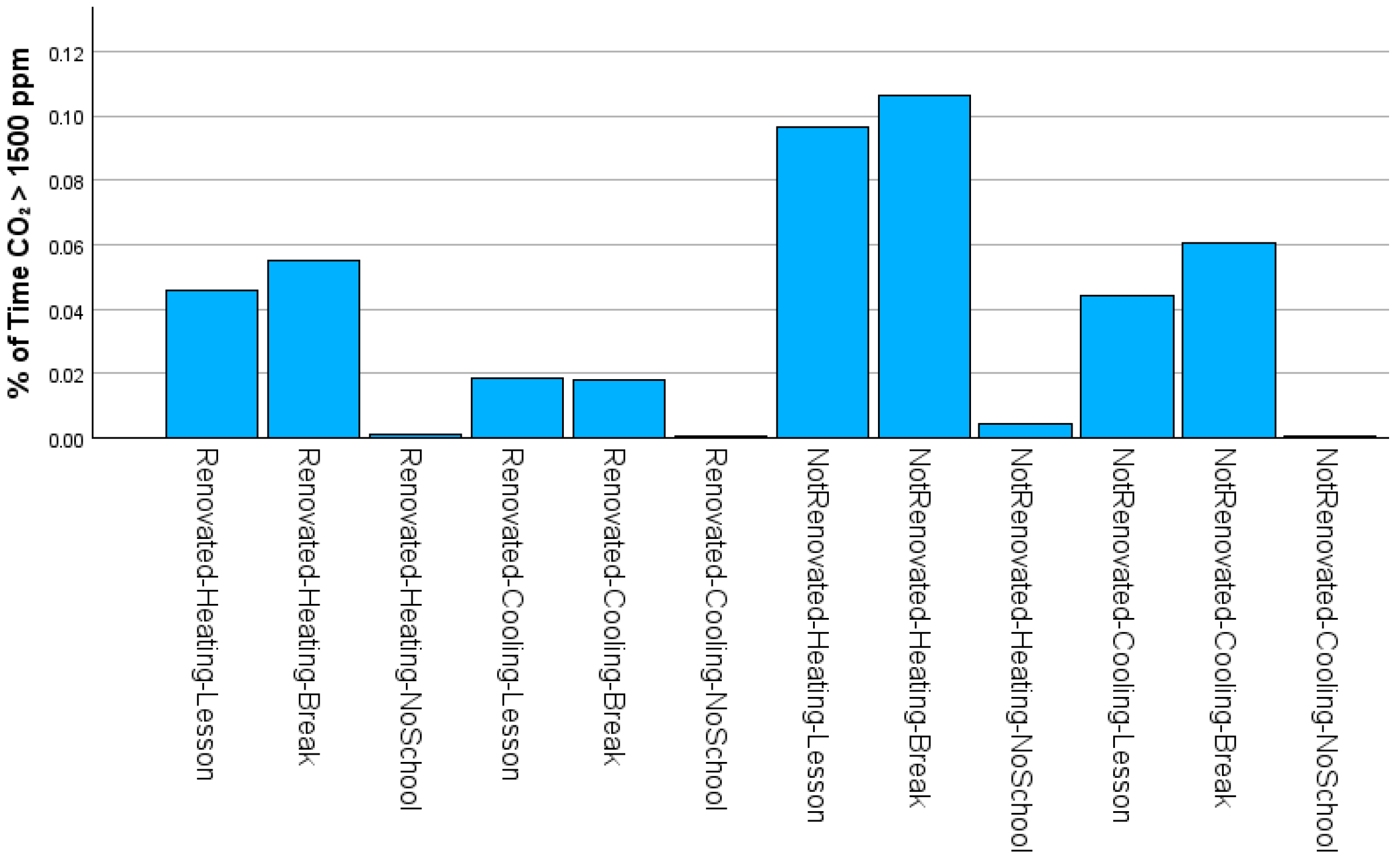

Figure 10 illustrates the share of time during which CO

2 concentrations exceeded the 1500 ppm threshold, separated by renovation status, season, and occupancy category.

In the non-renovated school, the percentage of time exceeding the threshold of 1500 CO2 ppm was significantly higher. During the heating season, lessons and breaks showed the highest values, with about 10% of the time above 1500 ppm. Even during breaks, when some airing might have occurred, concentrations frequently remained elevated. In the cooling season, exceedances decreased but persisted in lessons and breaks (≈5–6%), while non-school periods remained without exceeding the threshold of 1500 CO2 ppm.

Mixed ANOVA results confirm these observations (see

Section 3.5.2). School type and had a significant effect on CO

2, while school time showed an even larger effect on CO

2.

These results confirm that renovation lowers the risk of extreme CO2 accumulation, especially during the heating season, but does not eliminate it in the absence of mechanical ventilation. The heating season remains the most critical period, as reduced window opening limits natural air exchange. Short breaks also prove insufficient for full air renewal, particularly in non-renovated classrooms. Beyond the technical factors, teacher behavior plays an important role in shaping IAQ: some teachers open windows regularly and send students out during breaks, while others keep classrooms occupied and unventilated, leading to higher concentrations. This highlights that envelope renovation lowers CO2 levels and aligns with EU EPBD and Lithuanian STR requirements for modernized school buildings, but further improvements could be achieved by raising awareness among teachers about the influence of ventilation practices on classroom air quality. Practical strategies, such as teacher training, demand-controlled window airing, or hybrid ventilation solutions, are needed to ensure that renovation efforts result in consistently healthier indoor environments.

3.2.2. Temperature Threshold Breaches

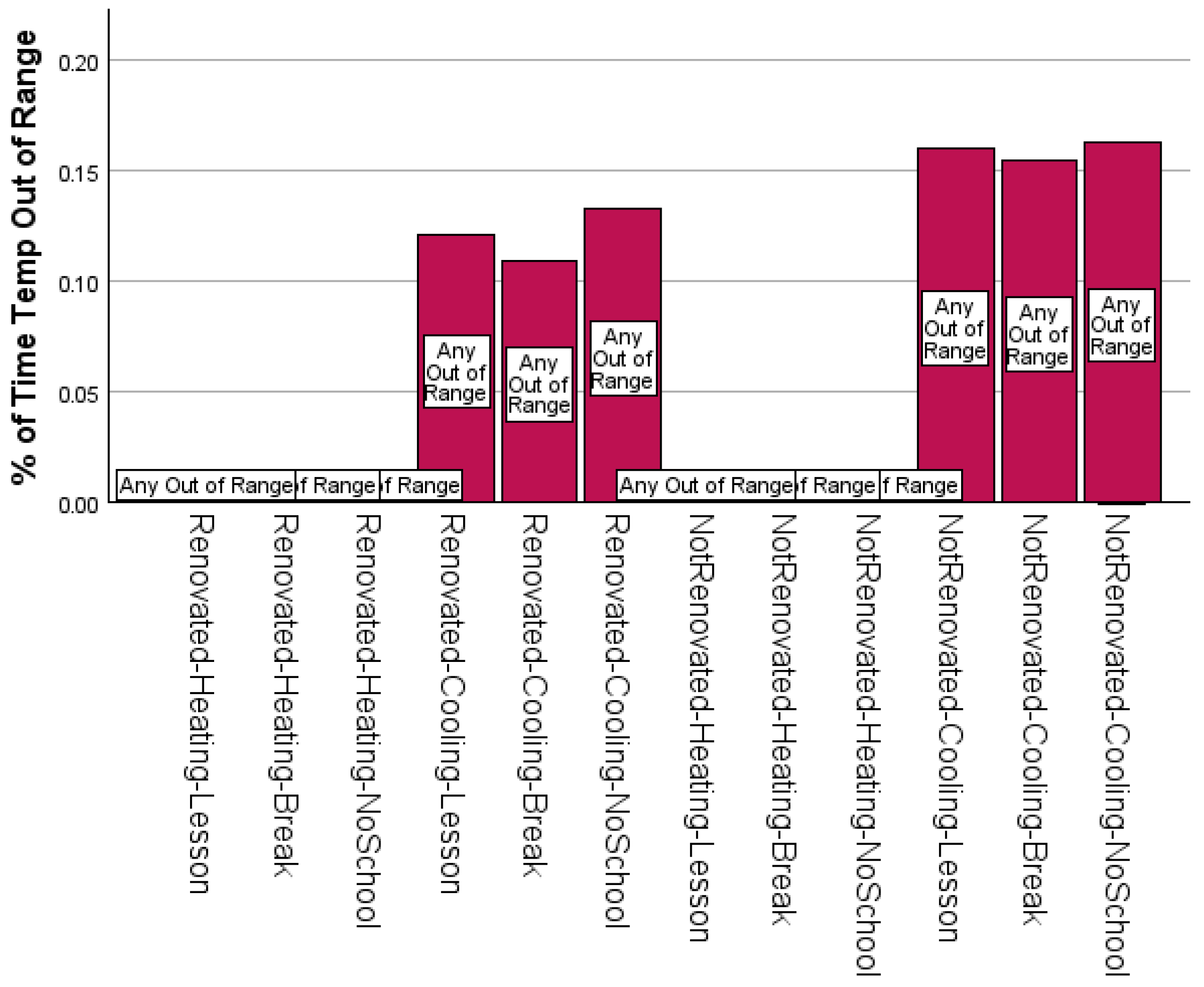

Temperature deviations from the acceptable seasonal ranges (see

Table 5) were markedly different between renovated and non-renovated schools (

Figure 11).

In the heating season, no temperature exceedances were recorded in either school type, demonstrating that both heating systems were capable of maintaining minimum thermal requirements during winter occupancy.

But during the cooling season, exceedances became evident. In renovated classrooms, deviations from the comfort range were relatively limited, typically 11–13% of monitored time, depending on occupancy period. In non-renovated classrooms, the exceedance rate was significantly higher, reaching 15–16% of time during lessons and breaks. This means that non-renovated classrooms experienced roughly 1.5 times higher exceedance rates than renovated ones during summer conditions, reflecting a lack of cooling capacity and shading systems.

Mixed ANOVA results confirm these patterns (see

Section 3.5.3). School type had a highly significant effect on indoor temperature.

From a practical perspective, these results suggest that envelope renovation substantially reduces overheating risk but does not eliminate it. Even in renovated schools, temperature breaches during the cooling season point to the need for complementary strategies such as external shading, hybrid ventilation, or dedicated cooling solutions.

3.2.3. Relative Humidity Threshold Breaches

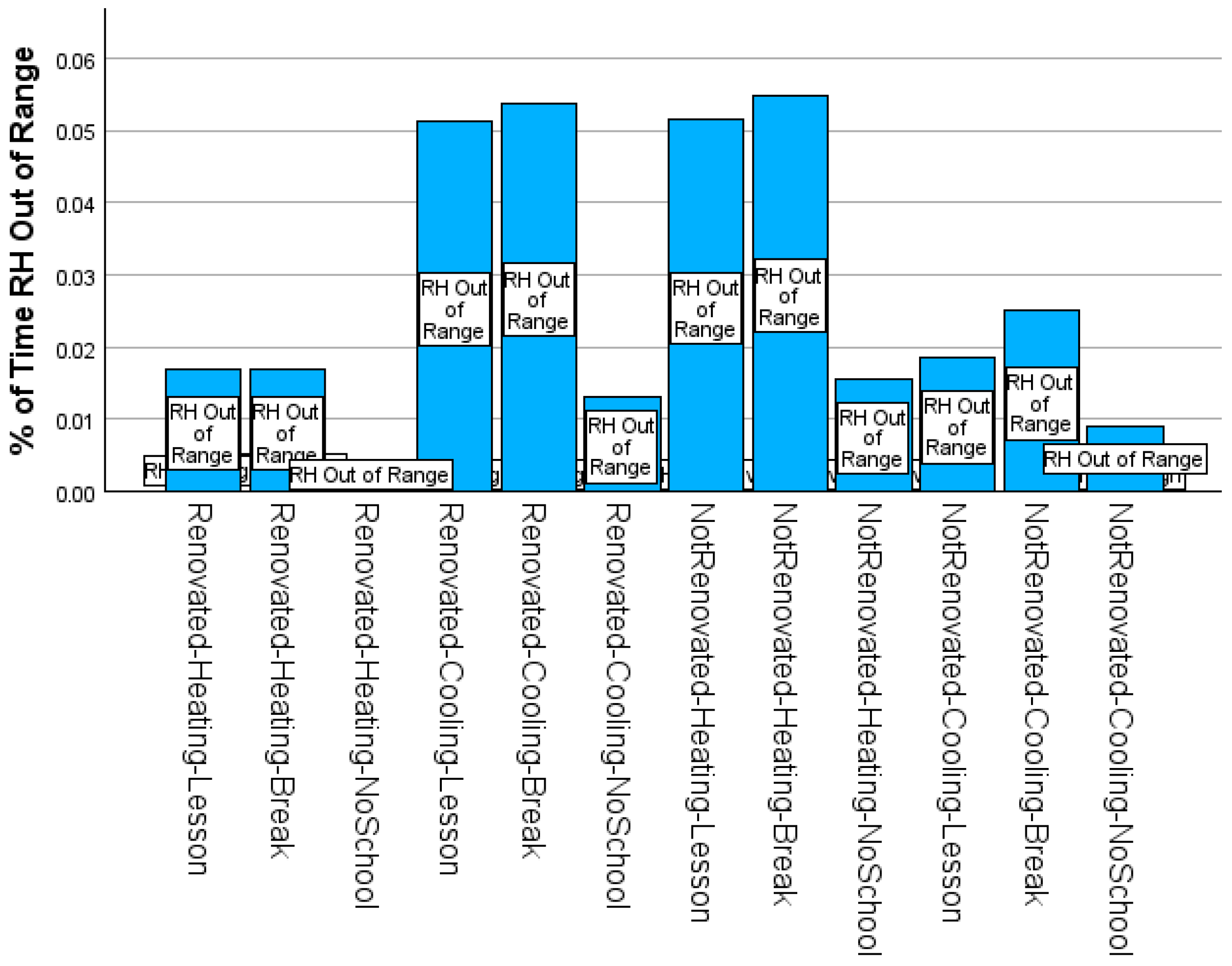

Relative humidity breaches were less frequent than CO

2 or temperature exceedances, but still present in both schools.

Figure 12 shows that RH exceedances (see

Table 1) occurred in less than 2% of monitored time during the heating season in renovated schools, and up to 6% during the cooling season. In non-renovated classrooms, breaches were consistently higher: around 5–6% in the heating season and 2–3% during cooling-season lessons and breaks.

Mixed ANOVA results support these patterns (see

Section 3.5.4). School type and school time had a significant effect on RH.

Renovated schools showed slightly better RH stability, but overall differences between renovated and non-renovated buildings were less pronounced than for CO2 and temperature. The main driver of RH variation was school time: during lessons and breaks, RH values tended to be higher in both schools due to occupant presence and activity, while during no-school periods RH levels dropped closer to background values. This indicates that occupancy patterns play a stronger role in shaping RH than renovation status.

From a practical perspective, these results suggest that RH alone may not be the most critical concern in Lithuanian schools, as exceedances were relatively infrequent. However, ensuring compliance throughout the year could still benefit from simple operational measures, such as coordinated window ventilation strategies during breaks, rather than more resource-intensive solutions like mechanical humidification or dehumidification.

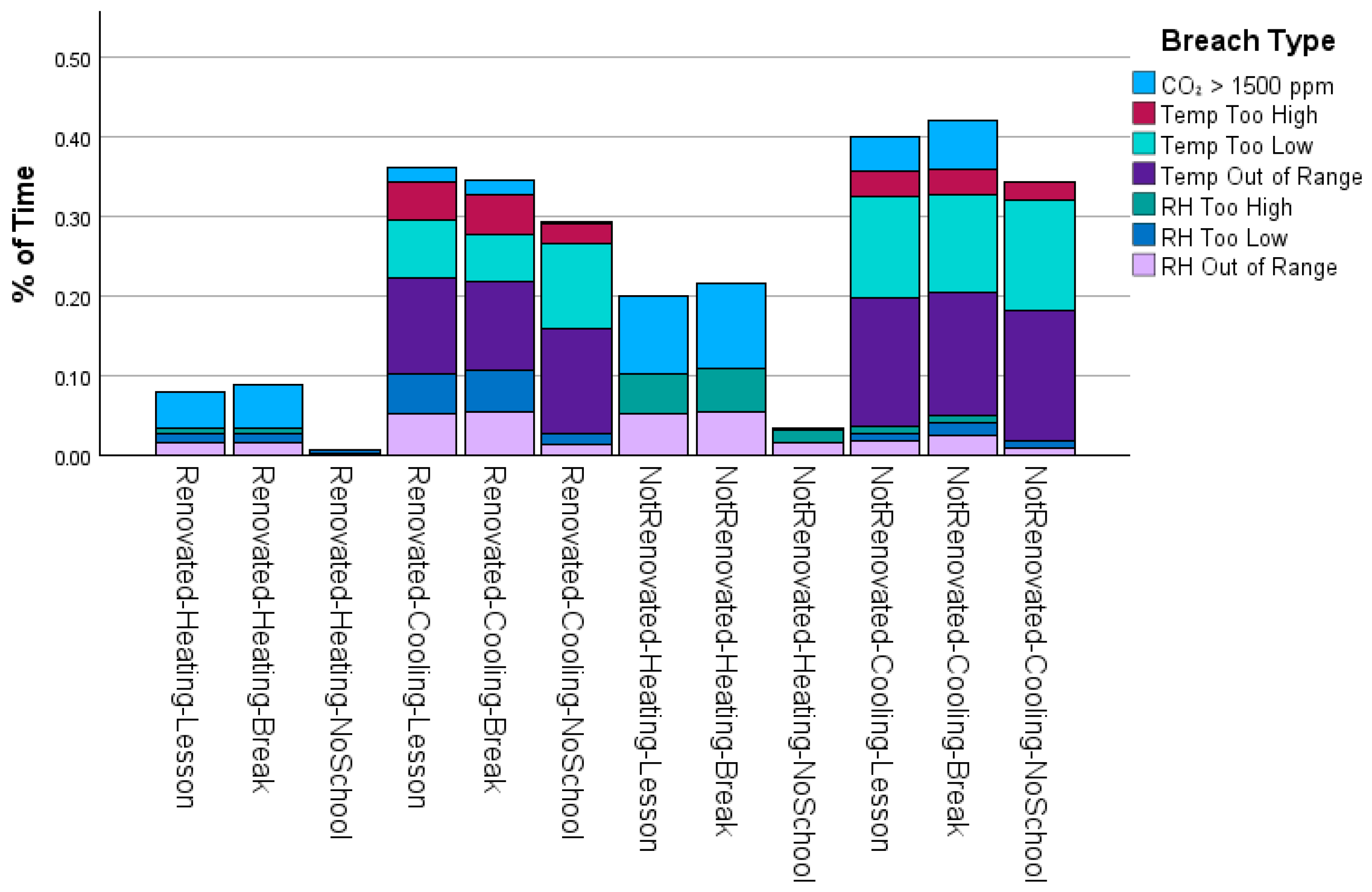

3.2.4. Combined Breach Overview

When all parameters (CO

2, temperature, RH) were considered together, the non-renovated school showed higher cumulative breach rates across nearly all periods, with total exceedances often reaching close to 40% of the monitored time during the cooling season (

Figure 13). During the heating season non-renovated school showed breaches at around 20% during occupied times. In contrast, the renovated school generally remained below 10% during the heating season, and during the cooling season, the breaches reached around 35%. The renovated school showed 5–10% lower results than the non-renovated school during the same school time periods and seasons.

The most problematic situation was during the cooling-season occupied times in the non-renovated school, where multiple parameters exceeded thresholds simultaneously, especially CO2 above 1500 ppm and RH out-of-range conditions. In both schools, the cooling season also revealed notable instances of temperatures falling below the comfort range. These numbers could have appeared mainly in the early cooling season, when outdoor conditions were still relatively cold, but heating had already been switched off, leaving classrooms occasionally cooler than recommended.

By comparison, the renovated school achieved more stable conditions overall, with breaches concentrated mainly during occupied cooling-season periods. Renovation clearly reduced the prevalence of simultaneous exceedances, yet it did not fully prevent RH or seasonal transition-related temperature issues. Importantly, RH-related breaches occurred in both schools, and RH contribution remained the biggest breach compared to CO2 and temperature.

From a practical perspective, these results highlight that envelope renovation significantly reduces cumulative breach rates; however, ventilation control and transitional-season management remain essential to maintaining compliance throughout the year. Particular attention is needed during the transition from heating to cooling seasons, when heating is switched off but outdoor temperatures can still be too low to meet recommended comfort ranges. In cases where schools lack mechanical equipment to manage these exceedances, staff practices and awareness actively become especially important. Simple measures, such as adjusting window airings, scheduling occupancy, or temporarily retaining some heating, can help mitigate seasonal transition issues. This supports the broader conclusion that energy-focused renovation alone is insufficient. Ventilation, seasonal transition control, and staff training are all required for year-round healthy school environments.

3.3. Independent Samples t-Test

Indoor air quality parameters (CO

2 concentration, temperature, and relative humidity) were compared between renovated and non-renovated schools using independent samples

t-tests. Analyses were conducted for the overall measurement period and separately for heating and cooling seasons (

Table 6).

CO2 concentration was statistically lower in renovated schools overall and during the heating season, though effect sizes were small (overall d = −0.109; heating d = −0.200). The 25-ppm overall difference, while detectable given the large sample size, represents only approximately 3.5% reduction and is unlikely to produce meaningful differences in occupant comfort, as perceptible IAQ changes typically require differences of 100–200 ppm. During the cooling season, no significant difference emerged (p = 0.441, d = 0.009), confirming that ventilation behavior rather than building envelope dominated warm-weather CO2 control.

In contrast, temperature and relative humidity differences showed large to very large effect sizes across all periods. Renovated schools maintained substantially warmer conditions, with the heating-season effect size reaching d = 5.346—an exceptionally large difference reflecting approximately 2.6 °C higher average temperatures. This represents a practically significant improvement in thermal comfort, particularly important during winter when non-renovated schools frequently fell below recommended ranges. Cooling-season temperature differences remained large (d = 1.822), indicating sustained thermal benefits year-round.

Relative humidity exhibited very large effect sizes in all comparisons (overall d = −2.329; heating d = −3.530; cooling d = −3.045), with renovated schools consistently maintaining drier conditions. During the heating season, the 7.32 percentage-point RH reduction in renovated schools moved conditions away from the upper comfort boundary, reducing moisture-related discomfort and potential condensation risks. These sustained, large-magnitude differences in thermal and moisture parameters demonstrate that envelope renovation produces meaningful improvements in occupant comfort.

The pattern of results—negligible CO

2 improvements but substantial thermal and humidity benefits—indicates that building envelope renovation addresses passive environmental control (heat retention, moisture regulation) effectively but cannot compensate for inadequate ventilation during occupancy. These findings align with threshold breach analyses (

Section 3.2) and ANOVA results (

Section 3.5), reinforcing that while renovation improves thermal and moisture conditions, CO

2 management requires complementary ventilation strategies and behavioral factors such as coordinated window opening during breaks.

3.4. Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess relationships between key indoor air quality variables, CO2 concentration, indoor temperature, and indoor relative humidity, and selected outdoor climate indicators (outdoor temperature and indoor–outdoor temperature difference, ΔTemp). Results for the renovated and non-renovated school are presented separately.

3.4.1. Heating and Cooling Season Trends

Both schools showed a strong negative correlation between indoor temperature and RH (renovated: r = −0.726; non-renovated: r = −0.641, p < 0.001), confirming the typical inverse relationship between heat and moisture.

3.4.2. Link with Outdoor Climate

Indoor temperature was moderately positively correlated with outdoor temperature (renovated: r = 0.593; non-renovated: r = 0.537), while indoor RH was moderately negatively correlated with outdoor temperature (renovated: r = −0.411; non-renovated: r = −0.239). This indicates that indoor conditions partly track outdoor variation, though more weakly in renovated schools.

3.4.3. Temperature Differences and Stability

ΔTemp was negatively correlated with indoor temperature (renovated: r = −0.468; non-renovated: r = −0.303).

3.4.4. CO2 Relationships

CO2 showed only weak correlations with outdoor temperature (renovated: r = 0.117; non-renovated: r = 0.150) and ΔTemp (renovated: r = −0.161; non-renovated: r = −0.203). However, CO2–RH correlations were substantial, particularly in the non-renovated school (renovated: r = 0.436; non-renovated: r = 0.711), suggesting that occupancy and ventilation patterns simultaneously drive moisture and CO2 accumulation.

3.4.5. Key Implication

The findings in

Table 7 indicate that renovation, even without HVAC installation, improves indoor environmental stability and reduces direct influence from outdoor conditions. The stronger CO

2–RH coupling in the non-renovated school underscores the importance of controlling infiltration and optimizing natural ventilation design.

3.5. Mixed ANOVA Results

This section presents results of a mixed Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) examining differences in indoor environmental parameters, CO2 concentration, temperature, and relative humidity, between lesson and break times across schools. The analysis further investigates whether these differences vary by school renovation status (renovated vs. non-renovated).

3.5.1. Research Design and Variables

A mixed ANOVA model was specified with:

Between-subject factor: School Type (1 = Renovated, 2 = Non-Renovated).

Within-subject factor: School Time (1 = Lesson, 2 = Break, 3 = No School Time).

Dependent variables: CO2 concentration (ppm), Temperature (°C), and Relative Humidity (%).

The dataset included 26,427 readings from each school type (total 52,854) and 9936 lesson readings (total 19,872), and 1050 break readings (total 2100) (excluding “No School Time” readings) for the within-subject factor. Although “No School Time” readings were excluded from the analysis, the within-subject factor (School Time) originally had three levels, which is reflected in the degrees of freedom reported.

3.5.2. Results for CO2 Concentration

The mixed ANOVA revealed significant main effects of both school type and school time on CO

2 levels, as well as a significant interaction between these factors (

Table 8):

School Type: F(1, 52,848) = 586.41, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.011 (small effect).

School Time: F(2, 52,848) = 8024.03, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.234 (large effect).

Interaction (School Type × School Time): F(2, 52,848) = 837.44, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.031 (small to medium effect).

The model explained approximately 25.2% of the variance in CO2 levels (Adjusted R2 = 0.252).

School time was the dominant factor, confirming that occupancy strongly elevated CO2 concentrations, particularly during lessons. Renovated schools consistently had lower CO2 levels, and the interaction indicates that this difference was most pronounced during occupied periods, when CO2 accumulation was highest. The model explained 25.2% of the variance in CO2 (Adjusted R2 = 0.252), underscoring the critical role of occupancy patterns in IAQ.

3.5.3. Results for Temperature

For indoor temperature, significant main effects and interaction were also observed (

Table 9):

School Type: F(1, 52,848) = 829.24, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.015 (small effect).

School Time: F(2, 52,848) = 216.06, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.008 (small effect).

Interaction (School Type × School Time): F(2, 52,848) = 10.80, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.0004 (negligible effect).

The model accounted for 11.1% of temperature variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.111).

School type explained more variation in temperature than school time, suggesting that building envelope characteristics and renovation status had a stronger influence than occupancy patterns. Although the interaction was statistically significant, the effect was negligible in size, indicating consistent differences across school types regardless of time of day. The model accounted for 11.1% of temperature variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.111).

3.5.4. Results for Relative Humidity

Relative humidity also demonstrated significant main effects and interaction (

Table 10):

School Type: F(1, 52,848) = 2293.83, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.042 (small to medium effect).

School Time: F(2, 52,848) = 345.23, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.013 (small effect).

Interaction (School Type × School Time): F(2, 52,848) = 243.68, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.009 (small effect).

The model explained 16.9% of RH variance (Adjusted R2 = 0.169).

School type had the strongest effect on RH, reflecting the importance of building envelope performance and renovation measures in maintaining moisture balance. School time also influenced RH, though less strongly, likely due to occupancy-related moisture generation. The interaction effect suggests that differences between renovated and non-renovated schools were more evident during occupied hours. The model explained 16.9% of the variance in RH (Adjusted R2 = 0.169).

3.6. Cluster Analysis

3.6.1. Clustering Approach

A K-means cluster analysis was conducted to identify distinct patterns of indoor air quality conditions across combinations of school type, season, and school time. Each case represented one of twelve unique group combinations defined by:

School type: Renovated vs. Non-renovated.

Season: Heating vs. Cooling.

School time: Lesson, Break, No School.

The clustering was based on seven IAQ indicators, each expressed as the percentage of time the parameter exceeded recommended limits:

Pct_High_CO2—CO2 concentration above the recommended threshold.

Pct_Temp_TooHigh—Temperature above the seasonal upper limit.

Pct_Temp_TooLow—Temperature below the seasonal lower limit.

Pct_Temp_OutOfRange—Temperature outside the comfort range (too high or too low).

Pct_RH_High—Relative humidity above the comfort range.

Pct_RH_Low—Relative humidity below the comfort range.

Pct_RH_OutOfRange—Relative humidity outside the comfort range.

All variables were standardized to ensure equal weighting in the clustering process. The optimal number of clusters (k = 3) is identified by examining the agglomeration schedule and dendrogram from preliminary hierarchical clustering, followed by K-means refinement.

3.6.2. Cluster Profiles

The three clusters reflected distinct IAQ behaviour patterns (see

Table 11):

Cluster 1—Overheating and dryness pattern:

Moderate CO2 exceedances (~3.54%), the highest occurrence of overheating (4.05% of time above the limit), and notable dryness (RH low 3.19%). The temperature was outside the comfort range approximately 13.6% of the time.

Cluster 2—High CO2 and high humidity pattern:

Cluster 3—Best-performing profile:

3.6.3. Distribution of Groups Across Clusters

Cluster membership showed clear links with season and renovation status:

Cluster 1 (n = 4)—Primarily heating-season lessons in a non-renovated school, where overheating, underheating, and dryness frequently co-occurred.

Cluster 2 (n = 2)—Mostly heating-season conditions in a non-renovated school, characterized by high CO2 and elevated humidity.

Cluster 3 (n = 6)—Included most cooling-season cases and several break periods, generally showing the best IAQ performance. Renovated school cases appeared here more frequently.

3.6.4. Interpretation and Implications

The clustering results indicate that IAQ challenges are strongly dependent on season and renovation status. The heating season in the non-renovated school consistently produced the most problematic patterns (Clusters 1 and 2), with either overheating/dryness or high CO2/high humidity profiles. The most cooling-season cases and break periods fell into Cluster 3, reflecting generally better IAQ performance.

Although neither school was equipped with mechanical ventilation systems, the renovated school still appeared more frequently in Cluster 3, maintaining better thermal–humidity balance and lower pollutant exceedances. This suggests that renovation measures beyond ventilation can significantly improve IAQ.

From a practical perspective, targeted interventions could further reduce risks: humidity management during winter for Cluster 1 profiles, and enhanced ventilation strategies during lessons for Cluster 2. These condition-specific actions are discussed further in the Discussion section.

3.7. LCA Analysis

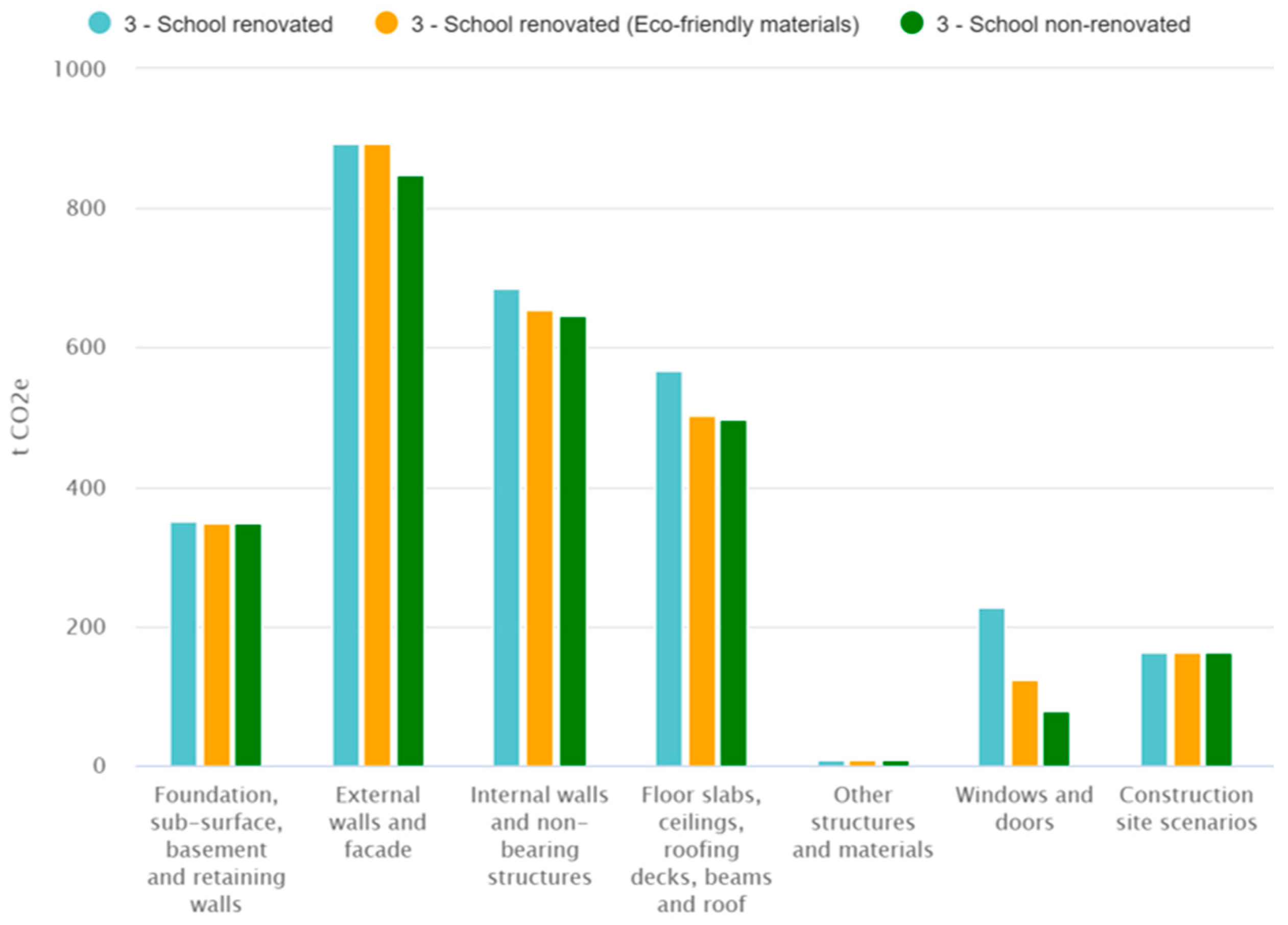

As shown in

Figure 14, external walls and façades accounted for the highest embodied CO

2e emissions across all scenarios, ranging from approximately 850–880 t CO

2e. Internal walls and non-bearing structures were the second-largest source (640–670 t CO

2e), followed by floor slabs, ceilings, roofing decks, and beams (540–550 t CO

2e). Foundations, sub-surface elements, basements, and retaining walls consistently contributed about 350 t CO

2e.

Windows and doors showed the most pronounced differences between scenarios. The renovated school scenario resulted in the highest emissions (~220 t CO2e), whereas the non-renovated baseline emitted significantly less (~130 t CO2e). This difference reflects the material-intensive nature of window and door replacements during renovation.

Other components, such as minor structures, contributed minimally (<10 t CO2e). Reported values represent A1–A3 product-stage emissions only, in line with the defined system boundary.

The eco-materials renovation scenario provided a clear advantage in lowering embodied emissions compared to conventional renovation. For most components, especially walls and finishes, the use of low-carbon or recycled materials reduced CO2e by 5–12%. While windows and doors remained emission-intensive, even in this scenario, eco-materials achieved measurable reductions that partially offset the additional impacts of renovation.

The renovated school scenario consistently displayed higher embodied emissions in several elements, particularly windows/doors and wall assemblies, due to the additional materials and layers required for refurbishment. However, these increases in upfront embodied CO2e must be interpreted in the context of potential long-term operational energy savings, which may offset the higher initial impacts.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study found clear differences in indoor air quality between renovated and non-renovated classrooms, with distinct seasonal and occupancy-related patterns. Renovated classrooms generally had lower CO2 concentrations, higher indoor temperatures, and lower relative humidity. Seasonal variation was evident: both CO2 and RH tended to be higher during the heating season, while temperatures were consistently higher during the cooling season. Occupancy strongly influenced conditions, CO2 levels during lessons were around 80% higher than during non-school periods.

Renovated schools experienced fewer threshold breaches for CO2, temperature, and RH, although exceedances still occurred during lessons in the heating season. In contrast, non-renovated schools recorded frequent breaches, particularly for CO2 and temperature in winter. Differences between school types were most pronounced in the heating season.

Correlation analysis supported these observations. Indoor temperature and RH were strongly negatively correlated, and renovation appeared to strengthen associations between RH, temperature, and ΔTemp. CO2 concentrations showed only weak links to outdoor climate, suggesting that occupancy patterns and ventilation effectiveness had greater influence.

Renovation improved indoor environmental stability by enhancing temperature control and reducing the direct impact of outdoor weather. However, CO2 concentrations remained problematic in both school types, especially during lessons, showing that envelope upgrades alone are insufficient without complementary ventilation measures. Particular attention is needed during the transition from heating to cooling seasons, when heating is switched off but outdoor temperatures can still be too low to meet recommended comfort ranges. In cases where schools lack mechanical equipment to manage these exceedances, staff practices and awareness actively become especially important. Simple measures, such as adjusting window airings, scheduling occupancy, or temporarily retaining some heating, can help mitigate seasonal transition issues.

Cluster analysis identified three distinct IAQ patterns: (1) overheating with dryness, (2) high CO2 with high humidity, and (3) a best-performing profile with minimal exceedances. The most problematic profiles occurred in non-renovated schools during the heating season, reflecting inadequate ventilation and less effective thermal regulation.

4.2. Renovated vs. Non-Renovated Schools

According to trends, renovated schools consistently maintained more stable indoor conditions than non-renovated schools. Envelope improvements such as insulation, airtightness enhancements, and window replacements reduced threshold breaches and kept conditions closer to comfort ranges, 20–22 °C for heating, 23–26 °C for cooling [

7,

9,

10], and within the optimal RH band of 30–60% [

7,

9,

11].

Correlation patterns help explain these differences. The stronger negative relationship between temperature and RH in the renovated school suggests that humidity was more responsive to temperature changes. Reduced influence of outdoor temperature also indicates that the upgraded envelope limited direct weather impacts. In contrast, the stronger CO2–RH correlation in the non-renovated school points to greater infiltration variability, likely due to lower airtightness.

Mixed ANOVA results showed smaller temperature fluctuations between lessons and breaks in the renovated school, indicating improved thermal stability. Humidity variability remained greater in the non-renovated building, particularly during breaks, suggesting less effective humidity control.

Renovation reduced the frequency and magnitude of extreme temperature and humidity conditions and increased the likelihood of classrooms falling into the best-performing cluster. However, persistent CO

2 exceedances during high-occupancy periods confirm that ventilation improvements are not only essential to complement airtightness and insulation measures, echoing prior research [

58] but also in schools that lack mechanical ventilation to efficiently manage these problems, staff awareness and training become especially needed and important.

4.3. Classroom-Level and Cluster-Based Differences

Despite clear building-level trends, substantial variation occurred between classrooms in the same school. Some rooms fell into different IAQ clusters despite identical envelope, heating, and ventilation contexts. This indicates that factors such as room size, occupancy density, heating control, or window-opening habits significantly shaped conditions.

In the non-renovated school during heating-season lessons, for example, one classroom showed overheating and dryness, while another had high CO

2 and high humidity. Such variation supports earlier findings that intra-building differences can rival or exceed those between buildings [

59,

60].

These results highlight the risk of relying solely on building-wide averages, which can mask problematic rooms. Targeted, room-specific interventions are often needed, particularly in older, naturally ventilated schools where user behaviour strongly influences IAQ.

4.4. Time-Based Differences and Occupancy Effects

CO2 concentrations peaked during lessons, often exceeding recommended thresholds and occasionally surpassing 1500 ppm. Breaks showed elevated but less frequent exceedances, and non-school hours typically stayed within limits. This pattern reflects the influence of human presence, as both CO2 and moisture rose during occupancy.

Heating-season lessons often combined high CO

2 with sub-comfort temperatures, suggesting that cold weather discouraged window airing and reduced natural ventilation effectiveness. These excursions are known to impair cognitive performance and increase health complaints [

2,

61]. Mixed ANOVA confirmed significantly higher CO

2 during lessons, with greater differences in the non-renovated school, pointing to less effective IAQ control.

Humidity patterns mirrored seasonal and operational influences. Cold, dry outdoor air in winter lowered indoor RH during ventilation, frequently pushing it below the 30–60% optimal range.

Lessons presented the most challenging thermal comfort and CO2 conditions, while breaks and cooling-season periods aligned more with the best-performing cluster. This supports the need for technical measures, such as demand-controlled ventilation, and behavioral strategies that encourage measures, such as adjusting window airings, scheduling occupancy, or temporarily retaining some heating.

4.5. Life Cycle Assessment and Environmental Impact

Because the scope of the LCA was limited to A1–A3 product stages, the reported results capture only upfront embodied emissions of materials. This focus was appropriate for comparing renovation strategies, but it does not account for construction, use-phase, or end-of-life impacts, which could influence the long-term balance of carbon performance. It is important to note that these trade-offs capture only the upfront embodied emissions (A1–A3: materials sourcing, transport, fabrication) and do not address long-term operational savings, life extension, or recyclability, factors outside the current model scope. Conclusions should be regarded as an appraisal of initial investment: whether operational energy reductions or service life extension will offset or outweigh these embodied impacts would require dynamic, full-lifecycle modeling beyond that presented here.

The findings demonstrate that while renovations improved thermal comfort and indoor CO2 levels, they also introduced higher embodied emissions, particularly from windows, doors, and wall assemblies. The eco-materials scenario showed that strategic substitution of conventional products can reduce these impacts by up to 12%, but windows and doors remain hotspots of embodied carbon.

Long-term environmental benefits will ultimately depend on the extent to which operational energy reductions compensate for higher embodied impacts. This highlights a dual challenge: improving indoor environmental quality while simultaneously minimizing carbon emissions. IAQ outcomes were strongly shaped by occupant behavior, density, and seasonal weather, not only by envelope quality.

Therefore, sustainable renovation requires an integrated strategy: combining low-carbon material choices (e.g., recycled-content finishes, eco-materials, modular assemblies) with effective ventilation management. Such an approach can better align the goals of carbon reduction and healthy indoor environments in school buildings.

4.6. Implications for School Renovation Policies

While statistical comparisons revealed significant differences between renovated and non-renovated schools across IAQ parameters, the practical magnitude of these differences varied. The large sample size (>211,000 observations) means that even small mean differences returned highly significant p-values, highlighting the need to consider both effect sizes and real-world relevance.

For CO2, although renovated classrooms averaged lower levels across the entire measurement period (675 ppm ± 159 vs. 700 ppm ± 289, d = −0.11), the wide variability in the non-renovated building meant substantial overlap between the two groups. During the heating season, the mean difference was greater (703 ppm ± 203 vs. 761 ppm ± 357, d = −0.20), though still classified as a small effect. Both values remained below internationally recognized thresholds for cognitive or health effects, which typically occur only with sustained increases of 300–500 ppm or higher. Moreover, the difference became negligible during the cooling season (d = 0.009). Thus, despite statistical significance, the observed differences in mean CO2 may not translate to perceptible improvements for occupants. However, the rate of threshold exceedances (>1500 ppm CO2) was nearly halved with renovation (5% vs. 12%), a difference likely to have meaningful implications for compliance and health.

In contrast, differences in temperature and relative humidity were substantial in both statistical and practical terms. Renovated classrooms were, on average, 1.8 °C warmer overall (22.4 ± 1.5 °C vs. 20.6 ± 2.1 °C, d = 1.0), with very large effects during the heating season (+2.6 °C, d = 5.35). Relative humidity was also considerably lower in renovated classrooms (overall d = −2.33; heating season d = −3.53), pointing to real improvements in comfort and the management of dry indoor air in winter.

These findings demonstrate that while envelope renovation produces modest and highly variable improvements in mean CO2, its main benefits are large and consistent gains in thermal comfort and moisture control. To meaningfully reduce CO2 exceedances and meet IAQ goals, renovation must be paired with ventilation upgrades and behavioral interventions.

4.7. Implications for School Renovation Policies

Thermal upgrades alone are insufficient for a healthy classroom IAQ. Policies should require post-renovation thermal comfort and CO

2 monitoring, staff training, and ensure that ventilation improvements accompany envelope works. Occupancy-driven ventilation control and staff training can help reduce CO

2 peaks and maintain compliance with standards [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Infiltration control should be integrated into renovation strategies, as airtightness improvements without adequate ventilation risk non-compliance with IAQ standards. Effective policy should therefore promote holistic retrofits that address airtightness, insulation, ventilation, and moisture management together.

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is the controlled comparative design. Two architecturally identical schools, one renovated and one non-renovated, were selected in the same suburb, with identical building shape, layout, and construction year. This minimized the influence of local climate, traffic, and outdoor air quality, ensuring that observed differences in IAQ could be attributed primarily to renovation status rather than external factors. Both schools accommodated students of the same age group and followed similar schedules, further reducing behavioral and operational variability.

Continuous, high-frequency IAQ monitoring was conducted from 29 March 2024 to 29 May 2024, covering both the heating season (ending 25 April) and the cooling season (beginning 26 April). This two-season approach captured thermal comfort and CO2 variations under distinct thermal and ventilation regimes. The integration of life cycle assessment and the use of statistical techniques such as correlation and cluster analysis enabled both broad trend identification and detection of specific problem areas.

Limitations include the focus on only two schools without mechanical ventilation systems, limiting generalizability to other building types or ventilation configurations. The absence of direct occupancy counts may have influenced interpretation of CO

2 variations. Furthermore, occupant-driven ventilation practices (window/door opening) were not directly monitored, which limits the ability to separate envelope and occupant effects on IAQ outcomes. Seasonal changes in CO

2 suggest behavior played a substantial role. (See

Section 3.1 for a full discussion). Sensor locations were determined by school authorities and varied between classrooms. However, this should not be considered a limitation, as IAQ standards apply to all classrooms regardless of renovation status.

Regarding the LCA, limitations primarily relate to scope and data assumptions. The analysis was restricted to A1–A3 product stages, excluding construction, use-phase, and end-of-life modules. A more complete life-cycle impact analysis, including use-phase energy, maintenance, and end-of-life scenarios, would be needed to fully understand long-term carbon trade-offs of renovation. As a result, the reported values reflect only upfront embodied emissions and not the full life cycle impacts. Material quantities were derived from design models, and environmental data were based on databases, which introduce variability depending on regional representativeness. These constraints mean that the LCA results are most robust for relative comparisons between scenarios (non-renovated, renovated, eco-materials) rather than as absolute carbon footprints.

4.9. Future Research Directions

Future studies should expand to a larger and more diverse sample of schools, including those with mechanical ventilation, and extend monitoring across a full annual cycle to capture more seasonal transitions. Linking thermal comfort and CO2 measurements with student performance indicators would help quantify the educational impact of environmental conditions. Also, field study can be improved by waiting till the non-renovated school gets renovated and repeating field studies in that school after it becomes renovated.

Experimental interventions, such as occupancy-based ventilation control, timed natural ventilation during lessons, winter humidification, and targeted behavioral changes, should be tested under real-world conditions to identify effective strategies for maintaining both thermal comfort and healthy IAQ. Material selection with low embodied carbon and renovation strategies that balance energy efficiency with indoor environmental quality should also be evaluated.

5. Conclusions

This comparative field study of two architecturally identical Lithuanian schools demonstrated that energy-focused renovations in schools can substantially improve thermal stability and reduce the frequency of extreme indoor air quality conditions, particularly in the heating season, but does not ensure full compliance with indoor air quality standards. The investigation reveals three critical findings with important implications for school building policy and practice.

First, renovation delivers large, practically significant improvements in thermal comfort and humidity control. Renovated classrooms maintained warmer and drier conditions, with average temperatures higher by ~1.8 °C overall (22.4 °C vs. 20.6 °C,

Table 6) and relative humidity lower by ~6% (39.4% vs. 45.2%,

Table 6). The effect was even stronger (effect sizes indicating very large practical significance (d = 5.3 for heating-season temperature, d > 2.3 for relative humidity across all periods)) in the heating season, where renovated schools were on average 2.6 °C warmer (21.0 °C vs. 18.4 °C) and 7.3% drier (40.4% vs. 47.7%) than non-renovated ones (

Table 6). These results confirm that renovation substantially improved thermal comfort stability.

Second, envelope renovation alone cannot resolve occupancy-driven IAQ challenges [

30]. Despite thermal improvements, CO

2 concentrations exceeded 1500 ppm during 5% of occupied time in renovated schools and 12% in non-renovated schools. Statistical analysis revealed only small effect sizes for CO

2 reductions (d = −0.11 overall, d = −0.20 heating season), with no significant cooling-season difference (

p = 0.441). Occupancy drove CO

2 levels approximately 80% higher during lessons compared to unoccupied periods (

Figure 9,

Figure 10, and

Table 9), demonstrating that ventilation inadequacy, not envelope performance, constitutes the primary IAQ barrier. Cluster analysis reinforced this conclusion: heating-season lessons in both school types frequently exhibited problematic IAQ profiles (high CO

2 with elevated humidity, or overheating with dryness), while only cooling-season and unoccupied periods consistently achieved best-performing status.

Third, improved comfort carries embodied carbon costs that require strategic mitigation. Life cycle assessment findings revealed that IAQ gains from renovations carry embodied carbon costs, reinforcing the need to balance operational energy savings with low-carbon material choices. For example, the use of eco-materials reduced embodied CO

2e by 5–12% across major assemblies without compromising thermal performance, indicating that low-carbon material selection can partially offset renovation impacts., especially walls and finishes (

Figure 14). Since the LCA encompassed only product stages (A1–A3), the full environmental balance depends on whether operational energy savings over the building service life compensate for higher initial embodied carbon—a critical consideration for future policy development.

These findings challenge current renovation approaches that prioritize envelope performance while neglecting ventilation and material carbon intensity. Effective school renovation requires integrated strategies combining:

envelope improvements for thermal stability;

adequate ventilation systems, mechanical, hybrid, or rigorously managed natural ventilation with CO2 monitoring;

low-carbon material selection to minimize embodied emissions;

occupant training and behavioral protocols to optimize ventilation during high-occupancy periods.

Policymakers should mandate post-renovation IAQ monitoring and establish performance standards that address both thermal comfort and air quality, rather than energy efficiency alone. Building practitioners must recognize that airtightness improvements without corresponding ventilation capacity risk creating thermally stable but unhealthy environments.

This study advances understanding of renovation–IAQ relationships by providing controlled comparison of identical buildings under real-world conditions, integrating environmental performance with embodied carbon assessment, and revealing classroom-level heterogeneity that building-wide averages can mask. The findings demonstrate that sustainable school renovation requires balancing multiple objectives, thermal comfort, indoor air quality, embodied carbon, and operational energy, through holistic design rather than single-parameter optimization. Only through such integration can the goals of climate mitigation, student health, and learning environment quality be simultaneously achieved.