Abstract

Based on the principle of re-centering with low prestress and energy dissipation through sloped friction (SF) energy dissipators, this study proposes a new hysteresis concept characterized by enhanced post-stiffness and energy dissipation for self-centering prestressed concrete (SCPC) frames. The focus of this research is to compare the seismic performance of SCPC frames utilizing both traditional and novel hysteresis concepts, aiming to provide critical evidence for the advancement of seismic-resilient structures. Nonlinear dynamic time history analyses were conducted under various seismic levels to investigate the impact of the novel hysteretic concept on seismic performance indicators, including inter-story drift, residual inter-story drift, and beam-column damage. Additionally, the influence of energy dissipator configuration and prestress level on the repair costs of structures subjected to the maximum considered earthquake (MCE) was analyzed to elucidate the structural functional recovery capacity. The results indicate that the combination of low prestress and sloped friction energy dissipators significantly reduces internal forces in beams and columns compared to traditional high prestress SCPC frames with conventional friction energy dissipators. The integration of sloped friction energy dissipators and the application of low prestress to post-tensioned (PT) strands effectively dissipate the energy transmitted to the frame during an earthquake, leading to a substantial reduction in structural damage within the SCPC frame utilizing the new hysteresis concept during large earthquakes, thereby facilitating post-earthquake repairs.

1. Introduction

With the development of resilient cities, the demands for the seismic performance of buildings are becoming increasingly stringent. In particular, to mitigate the damage caused by earthquakes and reduce repair costs, seismic resilient structures have emerged as a prominent research focus in the field of earthquake engineering. As a type of recoverable functional structure, self-centering precast concrete (SCPC) frames have garnered significant attention from scholars both domestically and internationally due to their ability to return to their original state after an earthquake, thereby eliminating residual deformations.

The achievement of functional recovery for the SCPC frame after an earthquake lies in the effective integration of energy-dissipating and self-centering systems. The self-centering system aims to minimize residual deformation, while the energy-dissipating system is designed to absorb seismic energy and reduce damage to the primary structure. With advancements in technology, the energy-dissipating systems of SCPC frames have diversified into various forms, including metal friction dampers [1], metal yielding energy-dissipating devices [2], and viscous dampers [3,4]. The continuous improvement of these energy-dissipation technologies has resulted in varying degrees of enhancement in the specific performance requirements for SCPC frames. For instance, Yang et al. [5] have demonstrated that SCPC frames, equipped with rotational friction energy-dissipating devices, exhibit significantly superior self-centering capacity compared to cast-in-place frames. The self-centering system also encompasses various configurations, including Post-tensioned (PT) strands [6], shape memory alloy (SMA) bars [7], fiber-reinforced composite bars [8], disk spring combinations [9,10], all of which establish different types of self-centering mechanisms. In addition, scholars also proposed a series of high-performance beam–column joints utilizing innovative material connections. For example, Qian et al. [11] introduced a self-centering joint enhanced by SMA strands and engineered cementitious composites (ECC) materials to enhance the ductility and energy-dissipation capacity of the structure, thereby delaying yielding of strands. Liu et al. [12] proposed a novel spring-based self-centering system that addresses the issue of prestress loss. The aforementioned study revealed that the stiffness of the spring and the pre-compression significantly affect the stiffness after joint opening, energy-dissipation capacity, and residual deformation.

SCPC frame, as an earlier developed type of recoverable functional structure used in practical engineering [13,14], effectively meets the seismic requirements of structures under design basis earthquakes (DBE). However, existing forms of energy-dissipators (such as commonly used friction energy-dissipators and angle steel energy-dissipators) used in the abovementioned SCPC joint possess a limited capacity to further enhance their energy-dissipation ability once activated, and may even degrade [15]. Moreover, the opening mechanism of joints inevitably reduces the lateral stiffness of the structure. This reduction in stiffness and energy-dissipation capacity may not adequately satisfy seismic demands during major earthquakes, as the substantial displacements and floor accelerations generated by the structure can lead to unintended structural damage and non-structural damage. Furthermore, existing designs often prioritize complete self-centering of the structure and typically apply high prestress to the PT tendons. This approach can result in insufficient deformation capacity of the PT tendons under large earthquakes, which may lead to yielding or rupture, thereby further diminishing or even eliminating the stiffness of the structure [16,17]. Additionally, excessive prestress can increase the internal forces within the main components, exacerbating unintended structural damage.

Based on the aforementioned issues, the authors have proposed a novel self-centering concrete frame by sloped friction energy dissipation (SF-SCPC), in which the principle of low prestress to re-centering is utilized [18,19]. The sloped friction energy dissipation configuration enhances the energy dissipation capacity and stiffness of the frame as the deformation of the joints increases. Low prestress effectively improves the deformation redundancy of the PT strands, reduces the internal forces on the main components, and mitigates the structural seismic response and potential damage. Compared to the previously mentioned self-centering prestressed concrete frames, this structure employs low prestressing to achieve a larger energy dissipation ratio (β). The sloped design of the energy dissipater enhances the stiffness after the joint opens. This dual approach significantly improves the energy dissipation capacity and stiffness of the structure during large earthquakes, thereby reducing dynamic responses. Notably, a new hysteresis concept characterized by enhanced post-stiffness and energy dissipation for self-centering prestressed concrete (SCPC) frames provides crucial evidence for the advancement of seismic-resilient structures. To comprehensively investigate the seismic performance of SF-SCPC frames, the investigation for series structures with varying parameters, such as story heights, prestressing levels and type of energy dissipators, is carried out in this study. Nonlinear dynamic time history analyses are conducted on the partial self-centering prestressed concrete frames with sloped friction (SF-PSCPC), partial self-centering prestressed concrete frames with planar friction (PF-PSCPC), and complete self-centering concrete frames equipped with sloped friction energy dissipators (SF-CSCPC) under various seismic levels. The influence of prestress and energy dissipation configurations on the influence of performance indicators such as inter-story drift, residual inter-story drift, and beam-column damage is examined. Additionally, the analysis addresses the impact of energy dissipator types and prestress levels on the repair costs of structures under maximum considered earthquakes (MCE), clarifying the structural functional recovery capability.

2. Working Mechanism of SCPC Joint with Sloped Friction Energy Dissipator

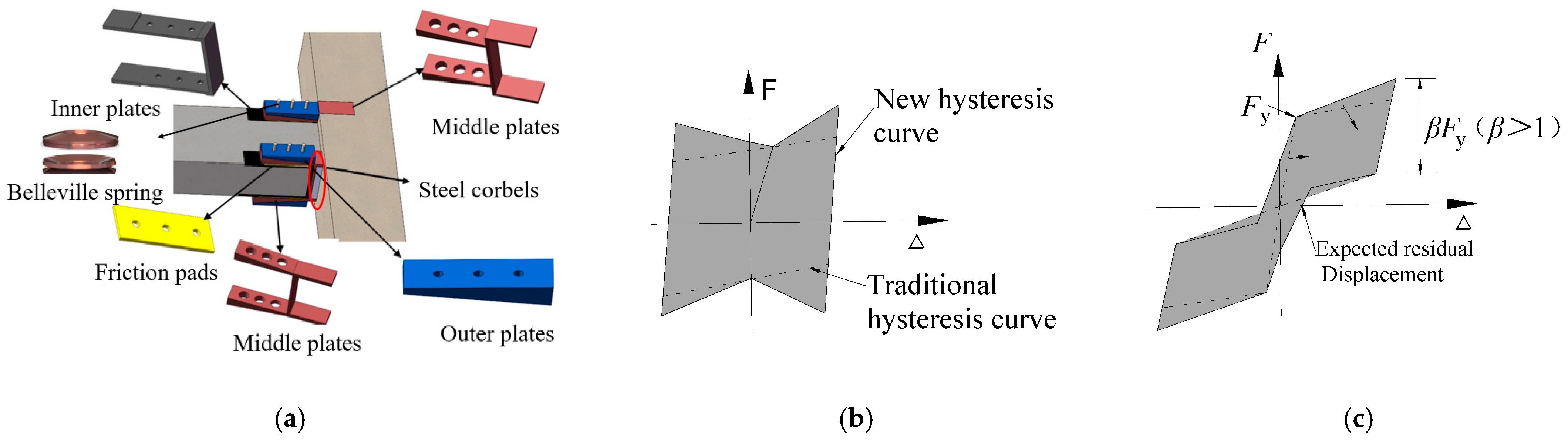

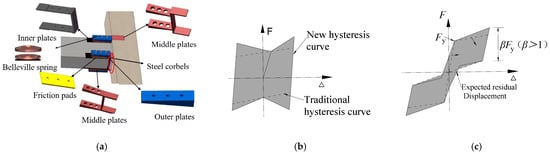

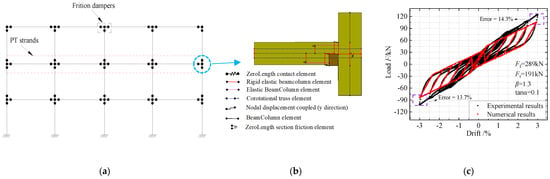

Figure 1a illustrates the sloped friction self-centering precast concrete (SF-SCPC) beam-column joint. This joint features a pair of sloped friction energy dissipators composed of high-strength friction bolts, outer plates with sloped surfaces, middle plates with sloped surfaces, inner plates, friction pads, and Belleville spring assemblies. The inner plates and middle plates are embedded within the beam and column, respectively. The friction pad is secured to the inner plate, creating a cohesive unit. The diameters of the holes for the high-strength friction bolts in the outer plates and inner plates are identical and smaller than those in the middle plates. This configuration allows the steel plates within the sloped friction energy dissipator to slide as intended, generating frictional forces. The Belleville spring assemblies, which possess adequate compressive deformation capacity and load-bearing capability, are installed at both ends of the bolt (Figure 1a). This installation is crucial for achieving increased energy dissipation with displacement. When the sloped middle plates and outer plates slide relative to each other, the Belleville spring assemblies undergo continuous compression, enhancing the pre-tightening force in the high-strength friction bolts. As a result, the frictional force progressively increases, allowing the sloped friction energy dissipator to achieve stiffness upon activation, thereby enhancing its energy dissipation capacity. PT strands, which are not depicted in Figure 1a, are positioned along the centerline of the beam to facilitate re-centering. Additionally, applying a low prestressing force to the PT strands not only expedites the structure’s installation but also enables a larger energy dissipation ratio, β. Preliminary research has proved that the SCPC frame equipped with sloped friction energy dissipators exhibits smaller inter-story drifts and a more uniform deformation pattern compared to the SCPC frame with traditional friction energy dissipators [20,21,22].

Figure 1.

SF-SCPC beam–column joints. (a) SF-SCPC joints; (b) Energy dissipation mechanism; (c) Force–displacement relationship.

The comparison of force–displacement relationship hysteresis curves between partial self-centering prestressed concrete frames with sloped friction (SF-PSCPC) joints and commonly used self-centering prestressed concrete (CSCPC) beam–column joints—characterized by high prestressing forces and planar friction dampers with constant friction force—is presented in Figure 1b,c. In this context, Fy denotes the “yield” strength of the structure, which corresponds to the load-bearing capacity when the joint opens. K1 represents the initial stiffness of the joint, which can be considered equivalent to the stiffness of a cast-in-place structure. In contrast, K2 is the second stiffness, which is significantly greater than that in the traditional hysteresis curve due to the configuration of slope friction dampers. In contrast to the CSCPC beam–column joint (Figure 1c), β for the SF-PSCPC beam–column joint exceeds 1, indicating that the contribution of the initial prestressing force is less than that of the energy-dissipating devices. The area under the new hysteresis curve is larger than that of the traditional hysteresis curve, indicating a larger energy dissipation capacity. This design ensures sufficient energy dissipation capacity to prevent significant damage to both structural and non-structural components during strong earthquakes. Additionally, a low level of prestress is applied to the PT strands, allowing for residual displacements within the structure, thereby ensuring that repair costs and time remain within acceptable limits.

3. Analytical Model

3.1. Prototype Structures

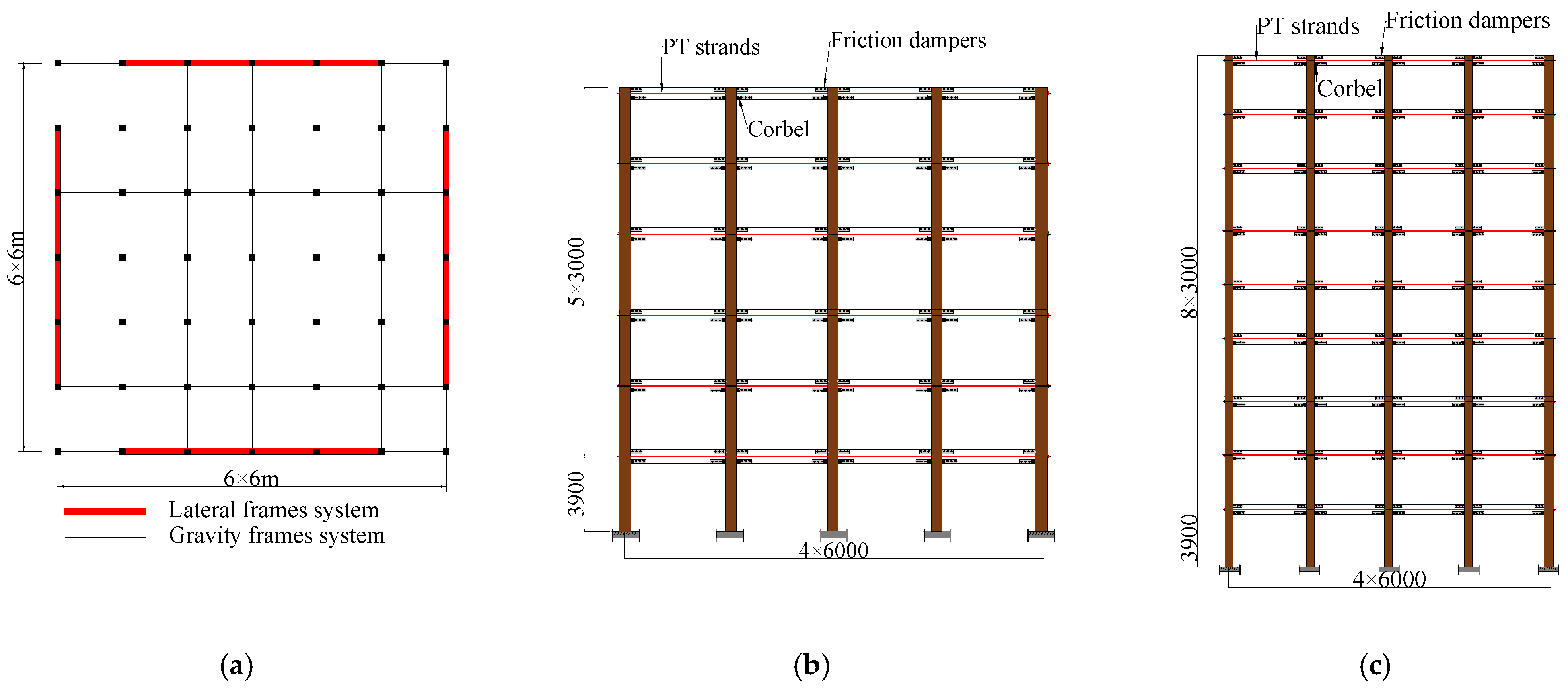

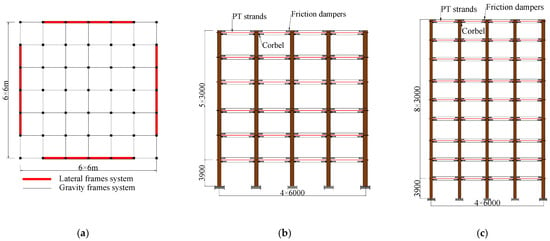

The structure designed by Huang et al. [19] is selected as a case study for seismic performance analysis. The analysis model consists of a reinforced concrete frame structure, as illustrated in Figure 2a. This model is based on a novel performance-based seismic design method, with the following performance objectives: under design basis earthquakes (DBE), the energy dissipators require no replacement, beams and columns remain within the elastic range, and the structure can be immediately occupied post-earthquake, with inter-story drift and residual inter-story drift limits set at 1.5% and 0.2%, respectively. Under maximum considered earthquakes (MCE), a limited number of structural components may experience plastic deformation, necessitating either replacement or minor repairs for continued use after the event, with inter-story drift and residual inter-story drift limit values established at 2.5% and 0.5%, respectively. Based on these design objectives, Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 present the design parameters for various structures.

Figure 2.

Multi-story SF-SCPC frames. (a) Layout of structures [19]; (b) Six-story frame; (c) Nine-story frame.

Table 1.

Parameters for the energy dissipators and PT strands for six-story structure.

Table 2.

Energy dissipator parameters and steel strand parameters of nine-story structure.

Table 3.

Beam-column reinforcement information of six-story structure.

Table 4.

Beam-column reinforcement information of nine-story structure.

The analytical model features six spans in both the transverse and longitudinal directions, with an overall length of 36 m. The corresponding six-story and nine-story structures are designed as analysis cases. The height of the first floor is 3.9 m, while the heights of the remaining floors are 3.0 m. In each direction, two self-centering frame structures, each with four spans, are incorporated as lateral resistance frames. The elevation views of the six-story and nine-story self-centering frames are depicted in Figure 2b and Figure 2c, respectively. Both beams and columns are constructed of C40 concrete, which has a cube compressive strength of 40 MPa. The longitudinal reinforcement consists of HRB335 bars with a yield strength of 335 MPa. The yield strength of the PT strands is 1320 MPa, with an ultimate strength of 1860 MPa and an elastic modulus of 195,000 MPa. The dead load on the roof is 7.5 kN/m2, while the live load is 0.5 kN/m2. For the other floors, the dead load is 5.0 kN/m2, and the live load is 2.0 kN/m2. This structure is classified as a Class C building, with a seismic fortification intensity of 8 degrees, a design basic seismic acceleration of 0.20 g, and it falls under design seismic grouping Group II. The soil category at the building site is classified as Category I. The designed information of beams and columns for the two frames is shown from Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

3.2. Designed Information for Friction Energy Dissipator, PT Strands and Structural Components

In the SF-SCPC frame, β is a critical parameter that influences design specifications, including the starting friction force for the sloped friction energy dissipator and the initial prestress in PT strands. Specifically, β > 1 corresponds to the SF-PSCPC frame, while β < 1 pertains to the SF-CSCPC frame. For the SF-PSCPC frame, β is set at 1.4, which determines the initial pre-tightening force applied to high-strength friction bolts (the starting friction force), the initial prestress, and the area of the PT strands. The tangent value of the slope (α) of the outer plates and middle plates in the sloped friction energy dissipator is 0.1. The parameters for the sloped friction energy dissipator and the PT strands are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, where Ff denotes the starting friction force of the friction energy dissipator, AT represents the area of the PT strands, and Ft indicates the initial prestress. Table 3 and Table 4 present the beam cross-sectional area (Ab), column cross-sectional area (Ac), longitudinal reinforcement area of the beams (Asb), and longitudinal reinforcement area of the columns (Asc).

Additionally, to assess the impact of the energy dissipator on the seismic performance of the structure, the energy dissipators in the SF-PSCPC6 and SF-PSCPC9 frames are substituted with commonly used planar friction energy dissipators that feature constant friction forces (designated as PF-PSCPC6 and PF-PSCPC9) for nonlinear dynamic time history analysis.

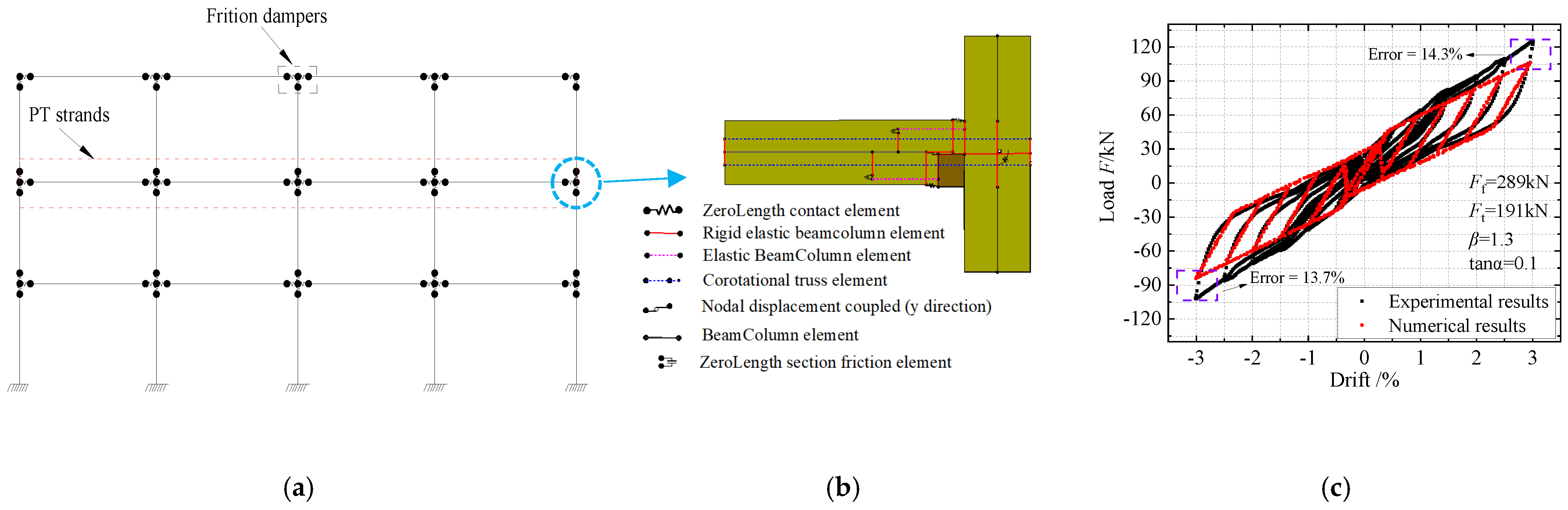

4. Numerical Model of Multi-Story Frames

A refined modeling approach was employed to develop the finite element model of the SCPC frame structure using OpenSees finite element software 3.7.1 [23,24]. The finite element modeling method for the SCPC joints is illustrated in Figure 3. Zero-length spring elements are utilized to simulate planar and sloped friction dampers. These zero-length spring elements feature a reinforced tensile and compressive restoring force model, which can be implemented using the Steel 02 constitutive material. One end of each zero-length spring element is connected to the beam, while the other end is connected to the column. Both the beam and column components are modeled using nonlinear beam-column elements based on the finite element flexibility method, wherein the cross-section of the beam and column is divided into multiple fibers to create a distributed plasticity model. In this model, concrete and reinforcement are represented by the Concrete 01 constitutive material model and the Steel 01 constitutive model, respectively. At the rotation points of the upper and lower sections of the beam–column joints, zero-length elements exclusively assigned with compressive materials are used to simulate the opening and closing behavior during operation. The PT strands are modeled using truss elements, which are provided with initial stress and the Steel 01 constitutive model to simulate the tensioning process.

Figure 3.

Numerical modeling of the multi-story frame. (a) Finite element model of frames; (b) Numerical model of connections; (c) Comparison between numerical and experimental results.

Based on the results of low-cycle loading tests conducted on friction-damped SCPC joints [18], the finite element model has been validated. Figure 3c presents a comparison between the verified test results and the finite element simulation results. The analysis shows that when the drift is less than 2.5%, the numerical simulation results align well with the experimental data. However, a discrepancy arises when the drift exceeds 2.5%, although this difference remains within 15%. Considering that the general design requirement for structures limits inter-story drift to 2.0% for seismic design, it can be concluded that the joint model illustrated in Figure 3b generally meets the accuracy requirements for the seismic performance analysis of SCPC frames.

For the SCPC frame structure, a damping ratio of 0.5% is employed [18]. It is assumed that the friction surfaces within the friction energy dissipator consist of steel-steel and stainless steel-brass interfaces. According to previous studies, the friction coefficient for the middle plate-outer plate interfaces is 0.16, while it is 0.33 for the inner plate-middle plate interfaces. The fundamental periods (T1) for the 6-story and 9-story structures are 0.71 s and 1.1 s, respectively. To account for the actual horizontal inertial forces on the supporting frame, an additional mass of 65.2 tons is applied to the top of the column for the top floor, and an additional mass of 78.9 tons is applied to the tops of the columns for the other floors. This additional mass does not exert any gravitational force. The beam-column system incorporates both material and geometric nonlinearity, with a vertical concentrated force of 66.5 kN applied at the top of the column for the top floor, and a vertical concentrated force of 80.5 kN applied at the tops of the columns for the other floors.

5. Seismic Performance of Structures with Different Parameters

5.1. Comparison Analysis of Inter-Story Drift

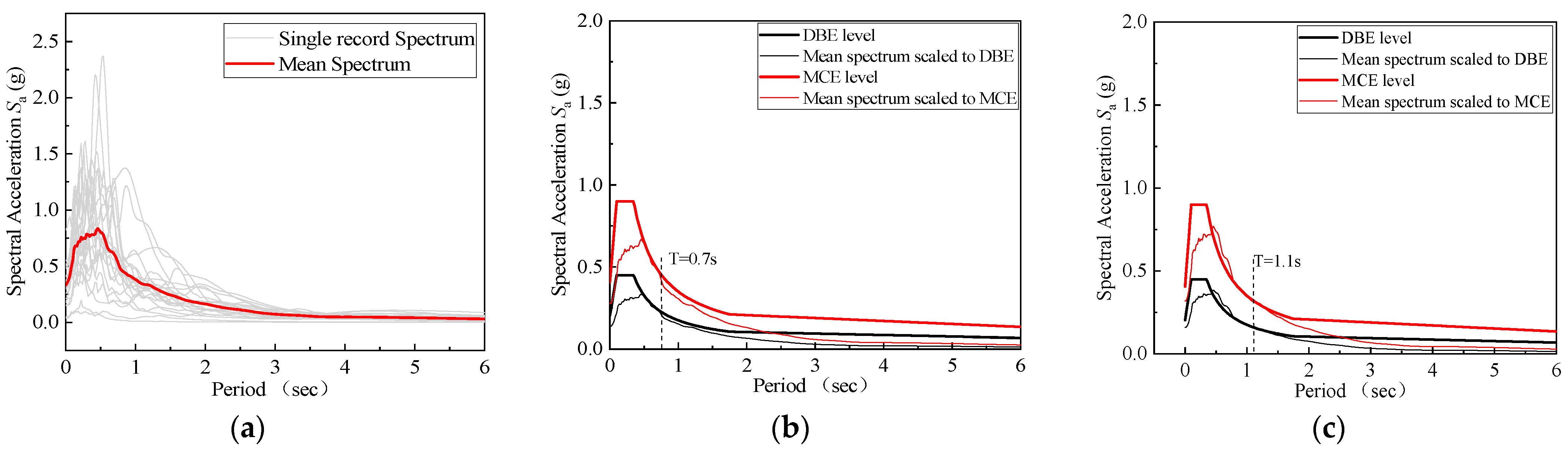

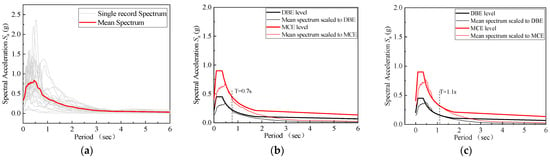

In accordance with the randomness of earthquakes and the selection criteria for ground motion records outlined in the ATC project [25], 22 ground motion records, as depicted in Figure 4a, were selected for the nonlinear dynamic time-history analysis of the structure. These ground motion records were adjusted to align with the Design Basis Earthquake (DBE) and Maximum Considered Earthquake (MCE) seismic levels, as illustrated in Figure 4b and Figure 4c, respectively, serving as the excitation input for the dynamic analysis.

Figure 4.

Earthquake ground motion records. (a) Twenty-two ground motion records; (b) Six-story frame; (c) Nine-story frame.

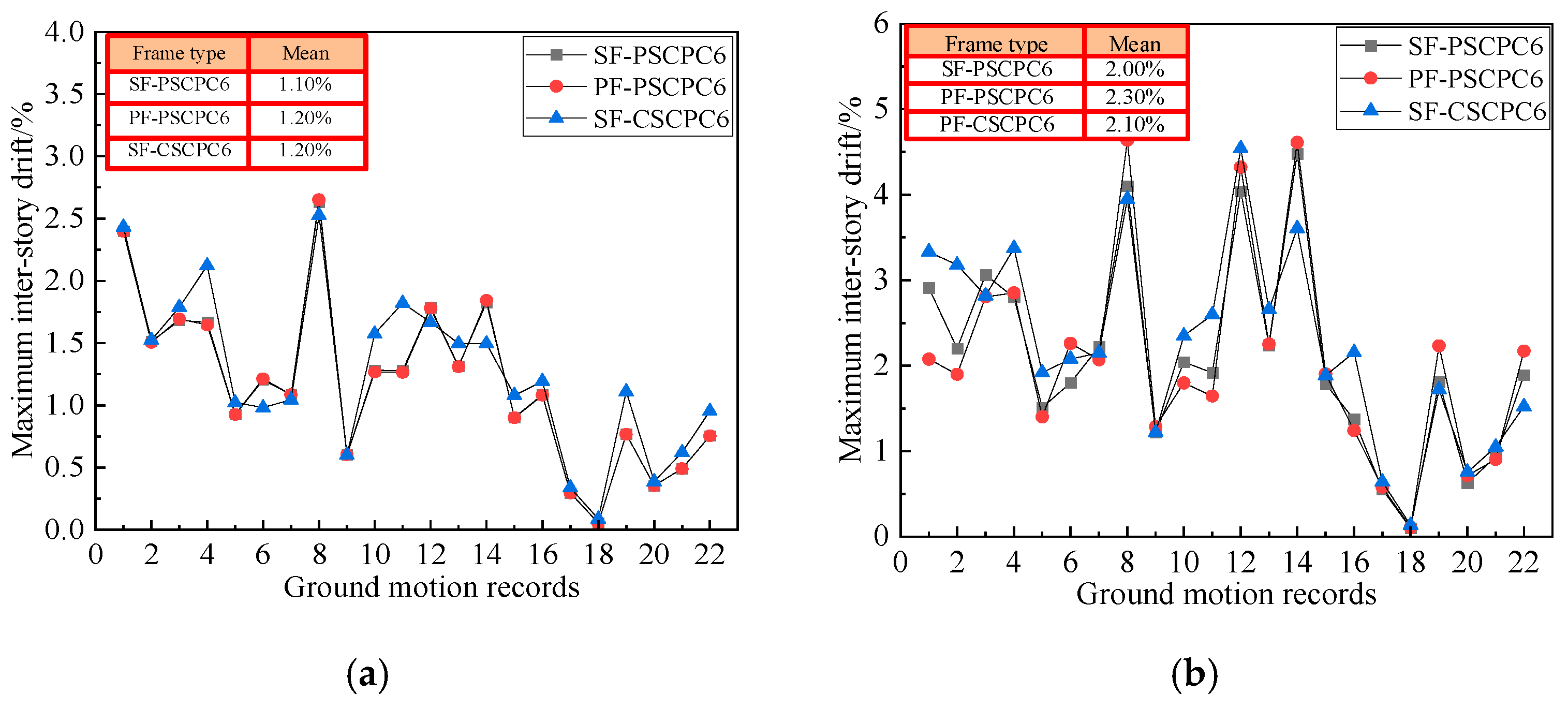

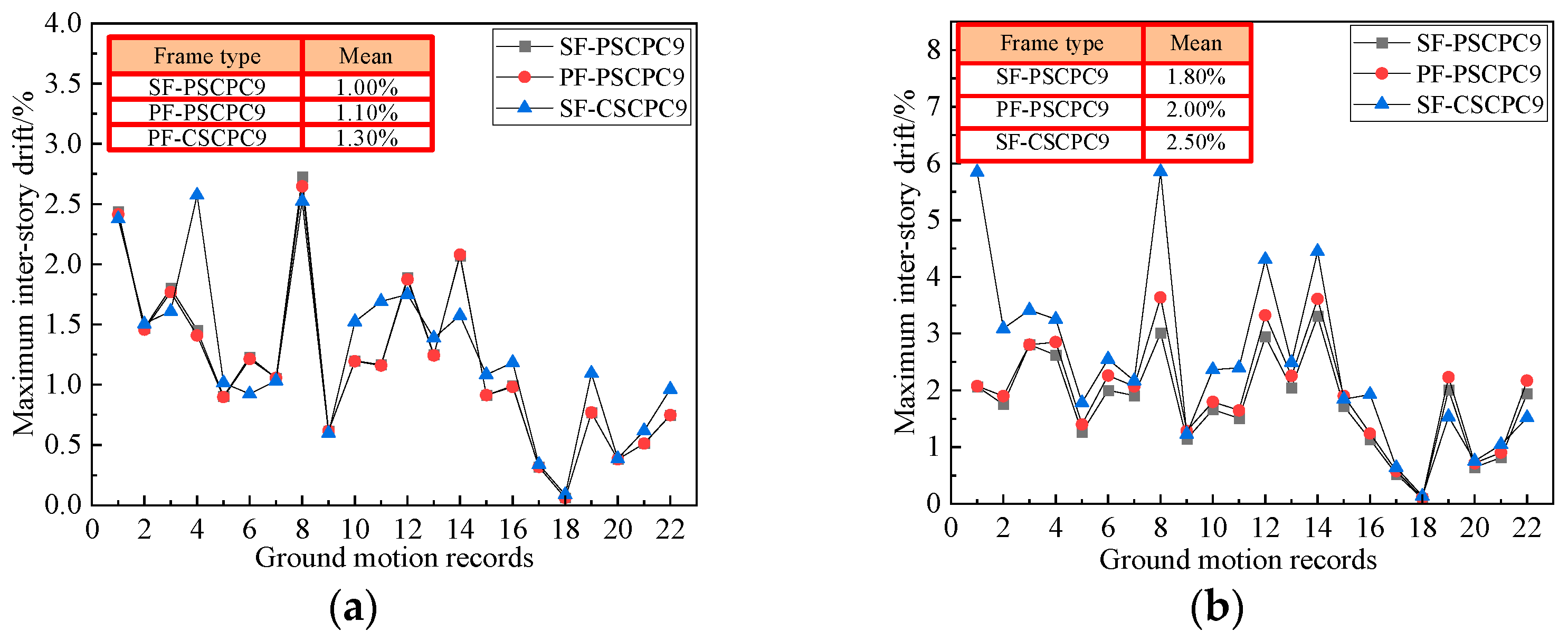

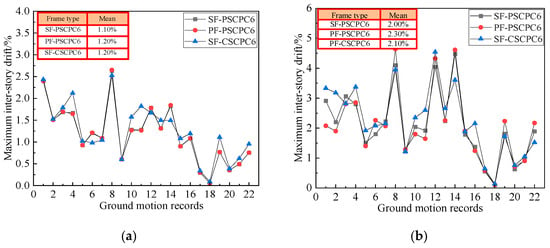

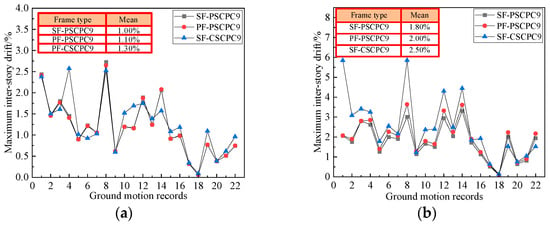

The inter-story drift of the PF-PSCPC frame was compared to that of the SF-PSCPC frame to analyze the impact of energy dissipation device configurations on the structural dynamic response, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Under the DBE seismic level, the inter-story drift of the PF-PSCPC frame is greater than that of the SF-PSCPC frame, while the fluctuations in inter-story drift for the SF-PSCPC frame are smaller. For instance, under the DBE seismic level, the average inter-story drifts for the PF-PSCPC6 and PF-PSCPC9 frames are 1.20% and 1.10%, respectively. In contrast, the maximum average inter-story drifts for the SF-PSCPC6 and SF-PSCPC9 frames are 1.10% and 1.00%, respectively. This indicates that replacing the planar friction energy dissipator with a sloped friction energy dissipator leads to a slight reduction in the inter-story drift of the SCPC frame at the DBE seismic level, although this reduction is limited.

Figure 5.

Inter-story drift of six-story frame. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

Figure 6.

Inter-story drift of nine-story frame. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

Under the MCE seismic level, the inter-story drift of the SF-PSCPC frame is significantly lower than that of the PF-PSCPC frame. For instance, under the influence of 22 ground motion records, the average inter-story drift of the SF-PSCPC6 is 2.0%, compared to 2.5% for the PF-PSCPC6, indicating a 25% reduction. This suggests that the arrangement of sloped friction energy dissipators enhances the secondary stiffness of the structure, thereby significantly reducing its inter-story deformation. In contrast, commonly used planar friction energy dissipators lack post-activation stiffness, which can result in excessive deformation of the structure during strong earthquakes.

By comparing the analysis results of the SF-CSCPC and SF-PSCPC frames, the effect of prestress levels on the structural dynamic response was analyzed, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The results indicate that under both DBE and MCE seismic levels, the inter-story drift of the SF-PSCPC frames is smaller than that of the SF-CSCPC frames. Specifically, under DBE seismic levels, the inter-story drift of the SF-CSCPC frames is greater, but the average inter-story drift does not exceed the 1.5% drift limit. Under MCE seismic levels, the inter-story drift of the SF-CSCPC6 frame is generally within the 2.0% range, while the average inter-story drift of the SF-CSCPC9 frames reaches the 2.5% drift limit. This may be due to the failure of some PT strands as the number of stories increases, thereby increasing the inter-story drift of the structure. The analysis suggests that, compared to the SF-CSCPC frames, the SF-PSCPC frames effectively reduce inter-story drift and improve the seismic performance of the structure. However, under MCE seismic levels, the higher prestressing in the PT strands of the SF-CSCPC frame may cause some PT strands to fracture, leading to larger inter-story drifts in the SF-CSCPC frame.

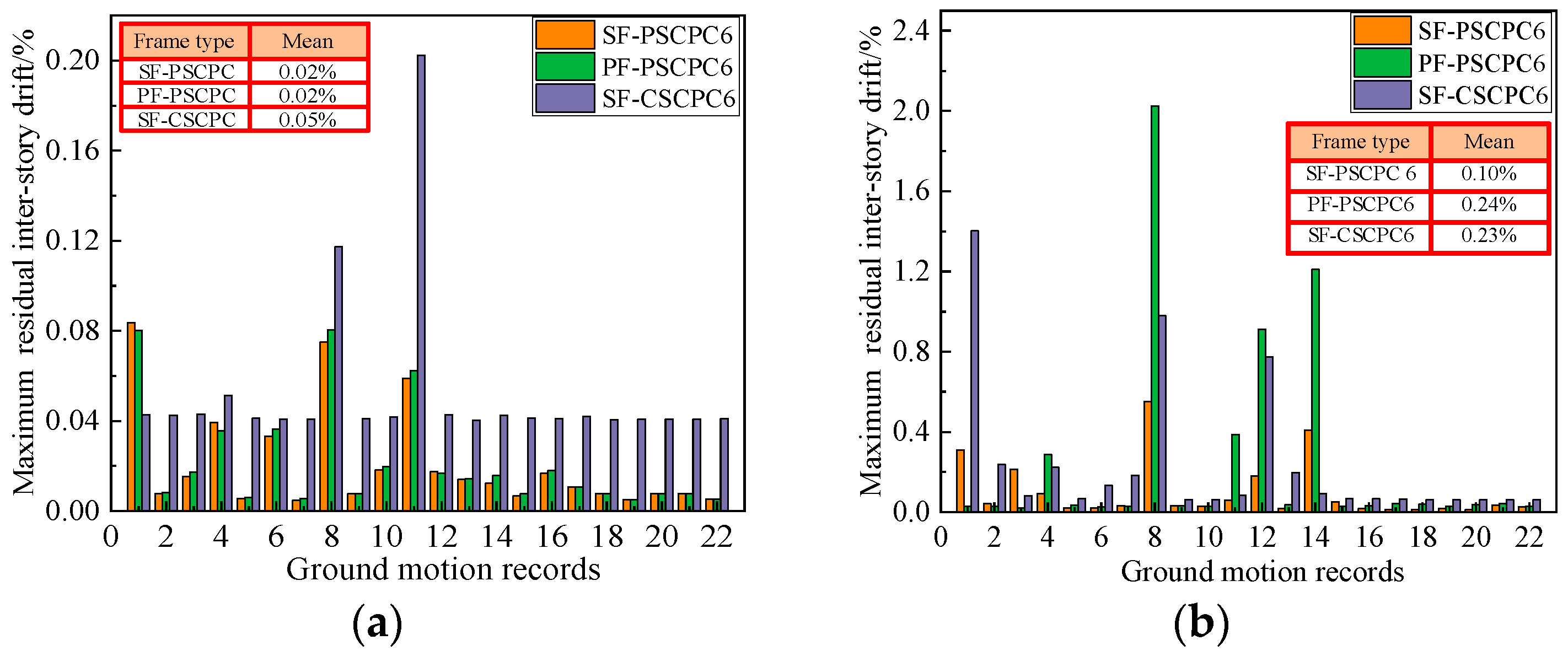

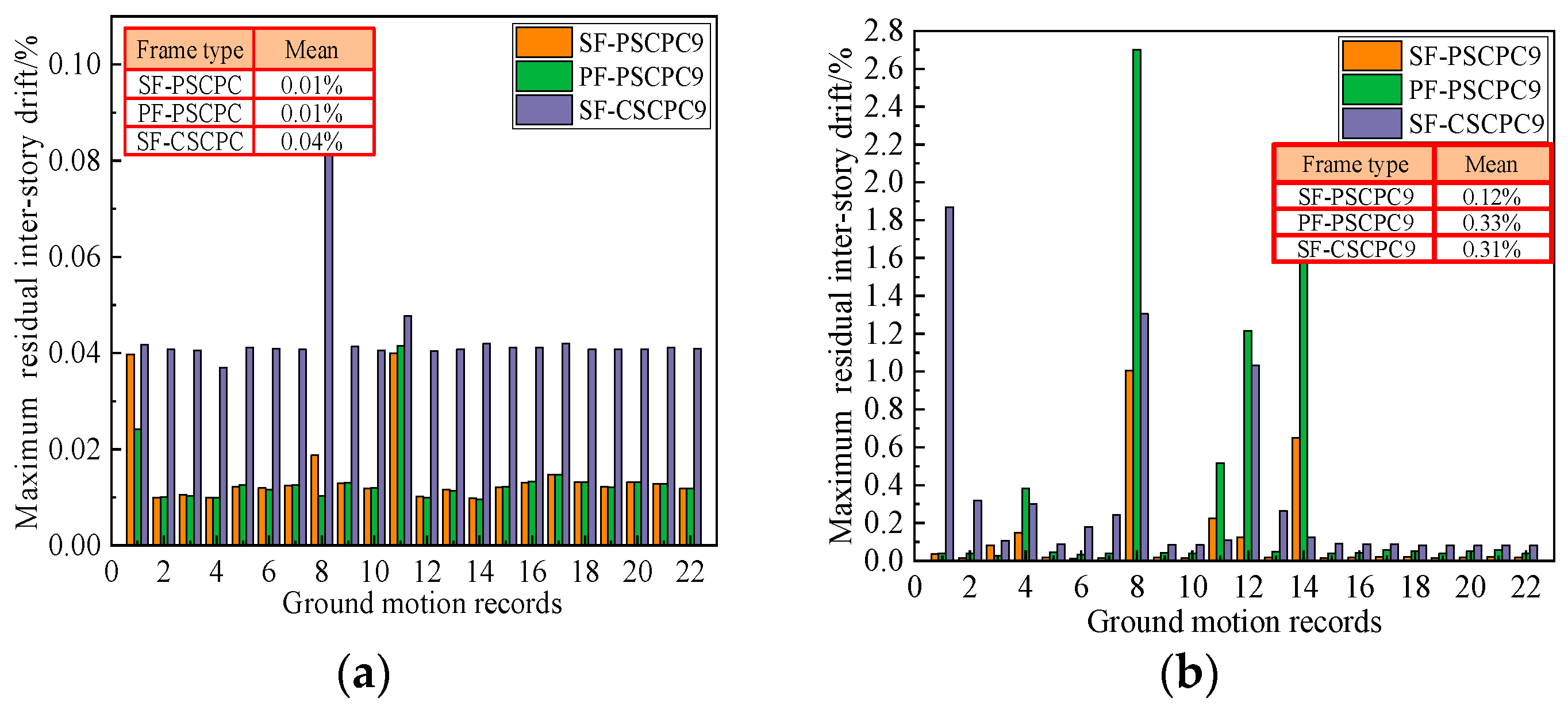

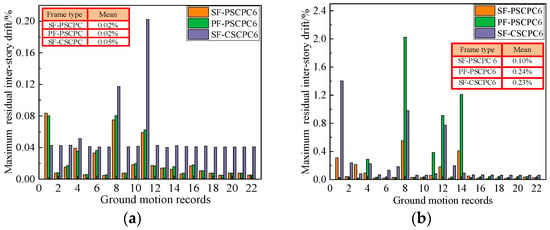

5.2. Comparison Analysis of Residual Inter-Story Drift

To analyze the impact of energy-dissipating device configurations on the recoverability performance of low-prestressed partial SCPC frames, the residual inter-story drifts of PF-PSCPC and SF-PSCPC frames were compared, as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. It is observed that, under the DBE seismic level, the residual inter-story drift of the PF-PSCPC frame is slightly greater than that of the SF-PSCPC frame, despite larger fluctuations. Overall, the residual inter-story drift of all structures did not exceed the immediate occupancy limit of 0.2% under the DBE seismic level. This indicates that in partial SCPC frames, the inherent large deformation capacity of the PT strands reduces the likelihood of yielding, ensuring that the structure consistently possesses a reliable self-centering system that meets the performance goal of immediate occupancy following moderate earthquakes. Additionally, the arrangement of sloped friction energy dissipators further reduces the residual deformation of the structure.

Figure 7.

Residual inter-story drift of six-story frame. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

Figure 8.

Residual inter-story drift of nine-story frame. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

Notably, under MCE seismic events, the residual inter-story drift of the SF-PSCPC frame is significantly lower compared to the PF-PSCPC frame, which exhibits low prestress characteristics. A possible explanation for this is that the arrangement of planar friction energy dissipators in the PF-PSCPC frame results in excessive deformation and damage to the structure, diminishing the re-centering effect relative to the SF-PSCPC frame. For instance, the average residual inter-story drift angle of SF-PSCPC6 is only 0.10%, while that of the PF-PSCPC frame reaches 0.24%, approaching the immediate occupancy performance target limit of 0.2%. This suggests that the structure necessitates a certain economic investment for usability following an earthquake.

Interestingly, the residual inter-story drift of the SF-CSCPC frame, characterized by high prestress, is also significantly greater than that of the SF-PSCPC frame under MCE seismic conditions. For example, the average residual inter-story drift of SF-PSCPC9 is only 0.12%, whereas that of the SF-CSCPC9 frame reaches 0.31% under MCE seismic conditions. This phenomenon may be attributed to the significant inter-story drift of the structure under seismic action, leading to considerable deformation of beams and columns. The prestress in the PT strands gradually increases, exerting substantial pressure on the concrete beams, which can cause damage to some beams and columns. This contributes to the larger residual inter-story drift observed. The analysis demonstrates that applying lower prestress and arranging sloped friction energy dissipators within SCPC frames can effectively enhance the self-centering capacity, control residual displacements, and help reduce post-earthquake repair costs.

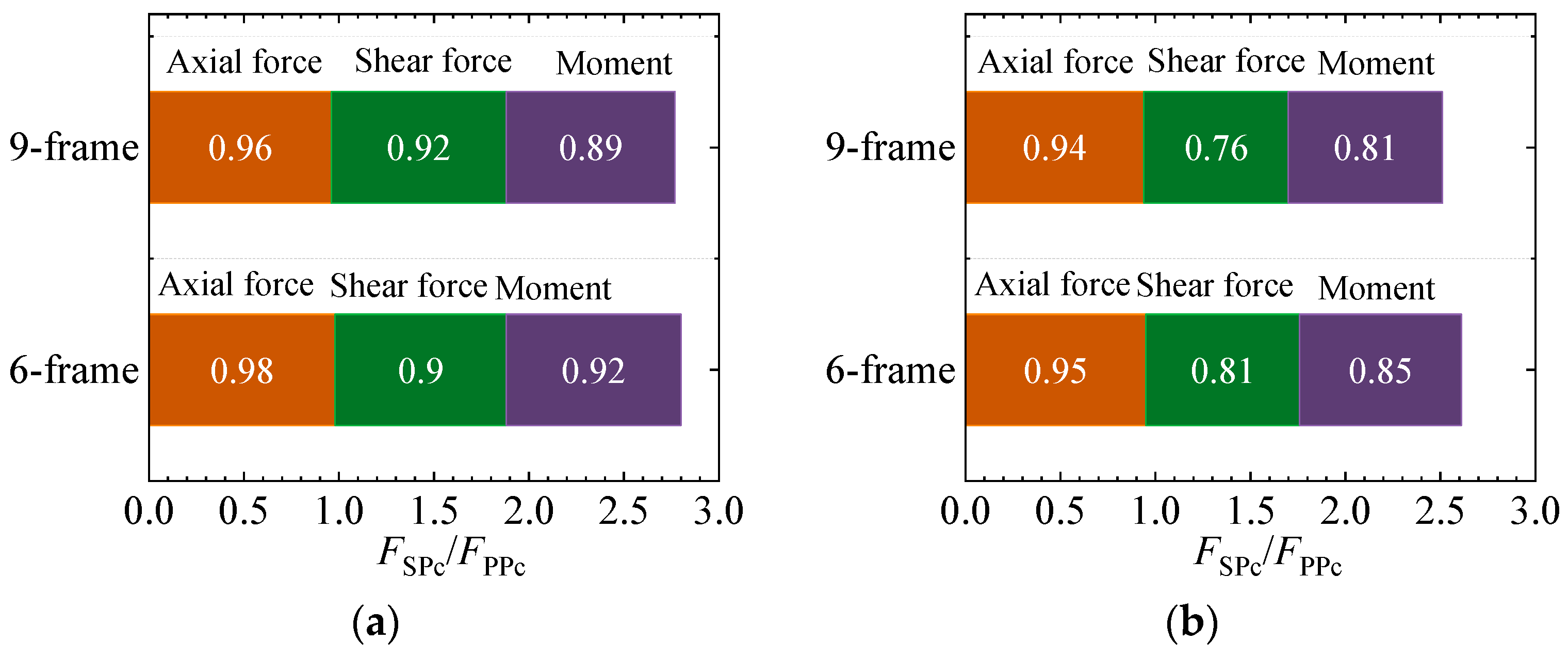

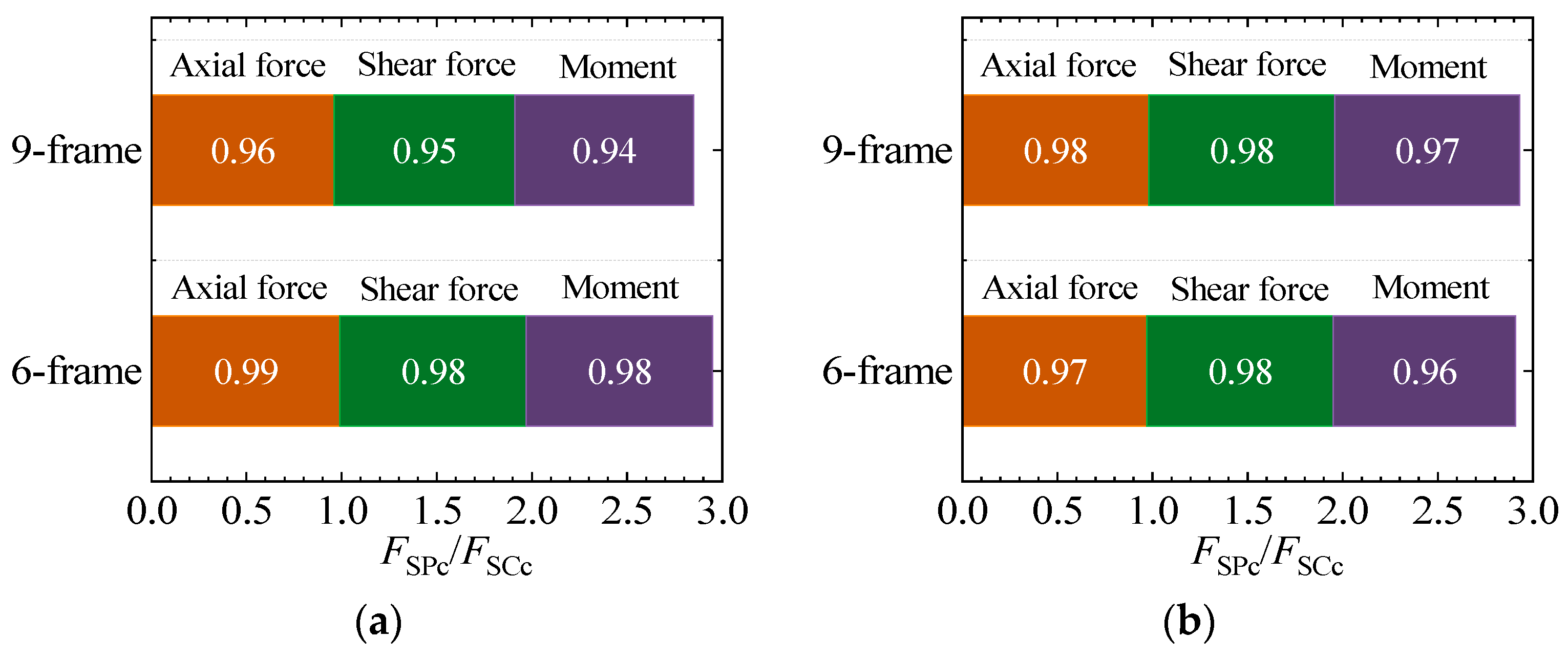

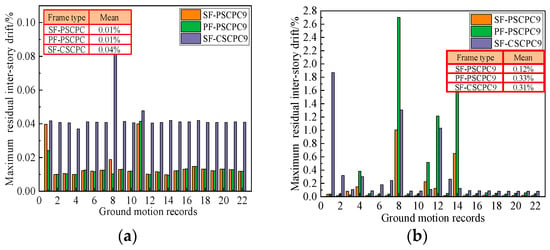

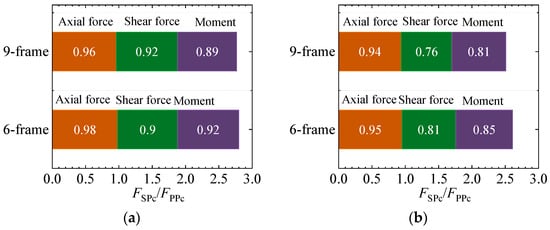

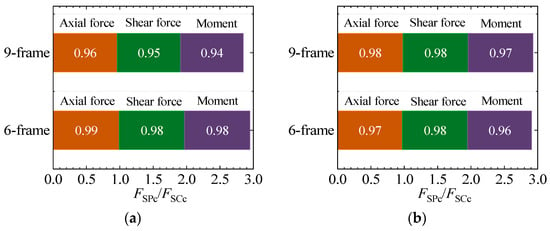

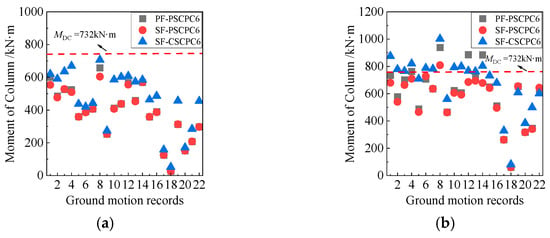

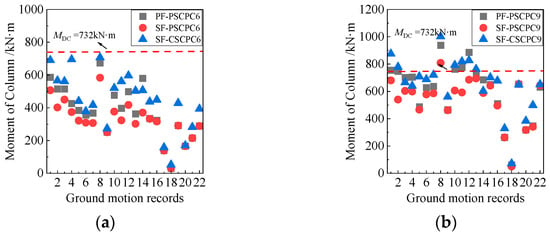

5.3. Comparative Analysis of Internal Forces in Structural Components

As illustrated in Figure 9 and Figure 10, the internal force conditions of the columns in the six-story and nine-story frames subjected to 22 seismic motions are summarized. In this context, FSPc, FPPc, and FSCc denote the internal forces of the SF-PSCPC, PF-PSCPC, and SF-CSCPC frames, respectively, encompassing axial force, shear force, and bending moment. To intuitively assess the impact of energy dissipation devices on column internal forces, the ratio of internal forces between the SF-PSCPC frame and the PF-PSCPC frame, denoted as FSPc/FPPc, is presented. Furthermore, to evaluate the effect of prestressing on column internal forces, the ratio of internal forces between the SF-PSCPC frame and the SF-CSCPC frame, denoted as FSPc/FSCc, is also provided.

Figure 9.

Analyses of friction dampers to the inner force of columns. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

Figure 10.

Analyses for the influence of prestressing on the inner force of column. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

From Figure 9, it is clear that at the DBE and MCE seismic levels, the ratio of the friction energy dissipators in the SCPC frame (FSPc/FPPc) is less than 1. This indicates that substituting planar friction energy dissipators with sloped friction energy dissipators results in a reduction in the axial force, shear force, and bending moment in the columns. The axial force ratio between the SF-PSCPC frame and the PF-PSCPC frame ranges from 0.94 to 0.98 at the DBE and MCE seismic levels, suggesting that sloped friction energy dissipators can mitigate axial forces in the structure, albeit to a limited extent. The shear force ratio between these two frames ranges from 0.90 to 0.92 at the DBE seismic level and decreases to between 0.76 and 0.81 at the MCE seismic level. Similarly, the bending moment ratio falls from 0.89 to 0.92 at the DBE level to between 0.76 and 0.81 at the MCE level. This analysis indicates that while the arrangement of sloped friction energy dissipators has a minor effect on axial forces in the columns, it significantly reduces both shear forces and bending moments, with these reductions becoming more pronounced as seismic intensity increases.

From Figure 10, it is apparent that at both the DBE and MCE seismic levels, the internal force ratios in the columns of the SF-PSCPC frame compared to those in the SF-CSCPC frame are predominantly less than 1, with a minimum value of 0.94. This suggests that reducing the high prestress in the structure to a lower level leads to a decrease in axial forces, shear forces, and bending moments in the columns, although this reduction is not particularly significant. Analyzing the influence of the friction energy-dissipating structural form on the internal forces in the columns, it can be concluded that in the SF-PSCPC frame, the energy-dissipating devices primarily control the shear forces and bending moments in the columns, while the protective effect of lower prestress levels on the columns is less pronounced compared to that of the energy-dissipating devices.

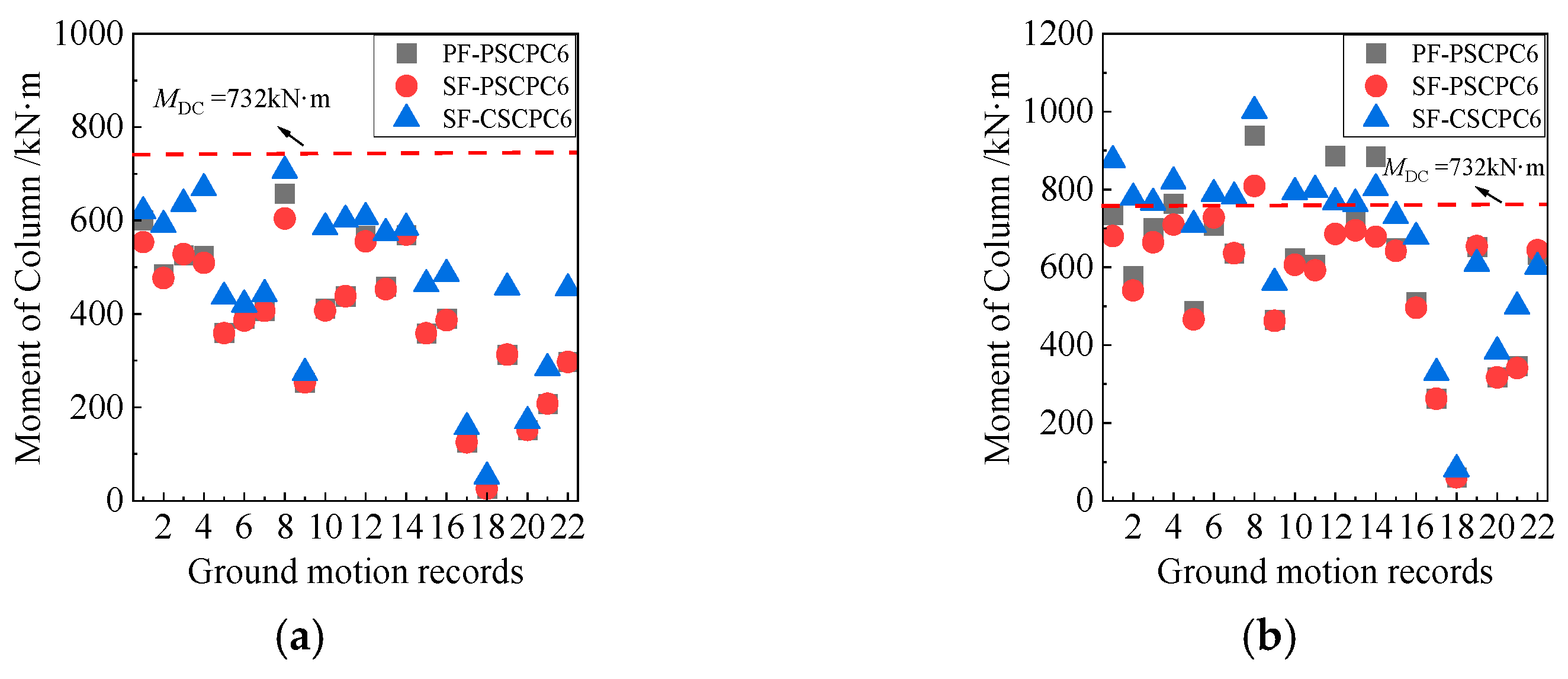

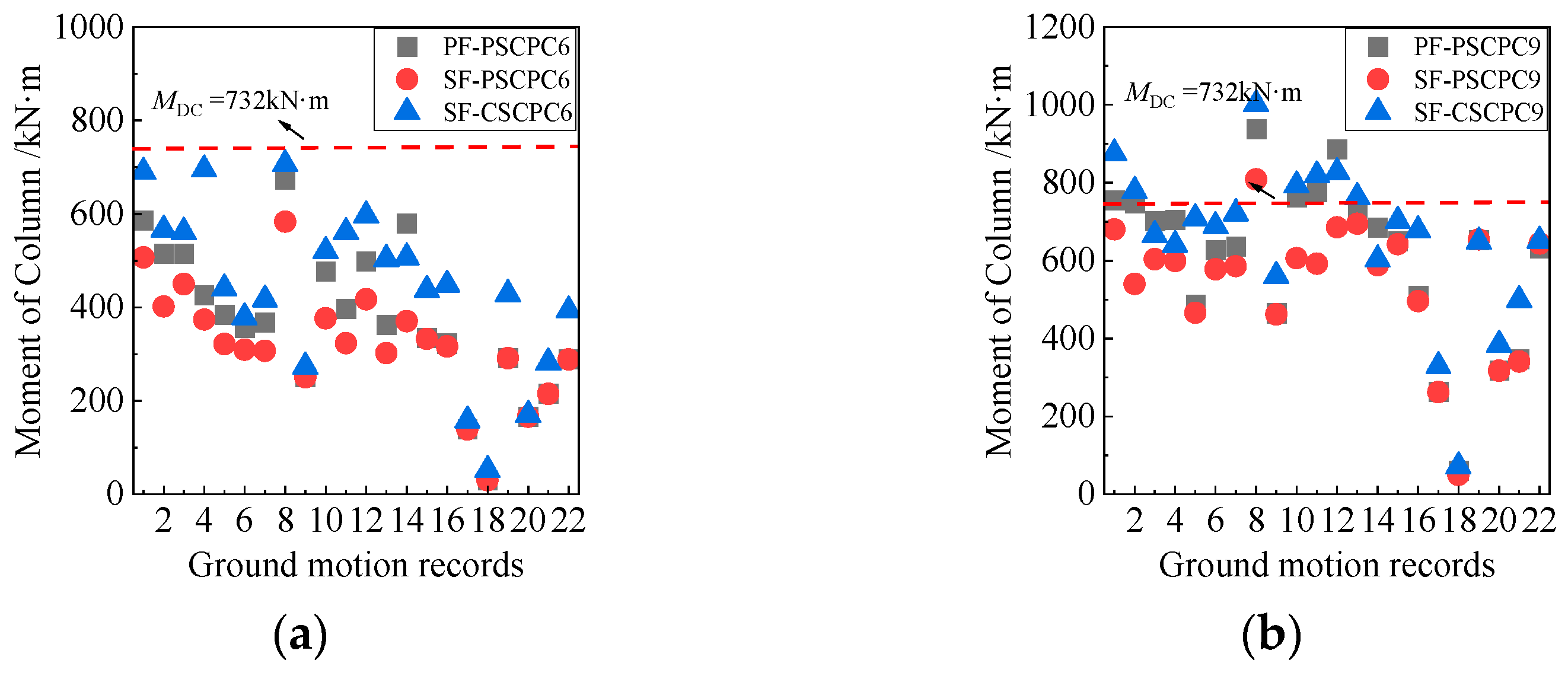

Figure 11 and Figure 12 compare the internal forces in the columns of the SF-PSCPC, PF-PSCPC, and SF-CSCPC frames to evaluate the damage conditions of these columns. It is noted that at the DBE seismic level, the internal forces in the columns of all structures remain below the design values. However, at the MCE seismic level, the internal forces in the columns exceed the design values. The bending moment for the columns in the SF-PSCPC frame exceeds the design moment under only one ground motion record. In contrast, the SF-CSCPC frame experiences bending moments that surpass design values under five ground motion records due to its higher prestress, indicating a degradation of seismic performance. The PF-PSCPC frame shows a greater than 30% probability of column damage at the MCE seismic level, reflecting a significant degradation in the loading capacity of structural components, which can be attributed to insufficient energy dissipation from the planar friction energy dissipators. This emphasizes that utilizing sloped energy dissipators and applying lower prestress to the prestressed strands can effectively dissipate the energy transmitted to the frame during an earthquake. Consequently, this approach reduces the energy demand on the columns, enhances the structure’s repairability, and significantly improves its safety performance.

Figure 11.

Column inner force of six-story frames. (a) DBE; (b) MCE.

Figure 12.

Column inner force of nine-story frames. (a) DBE; (b) MCE.

6. Architectural Functions Recoverability

In recent years, the architectural function recoverability performance of architectural structures, as determined by post-earthquake repair costs and repair times, has garnered increasing attention [26]. As previously analyzed, structures with varying parameters exhibit different degrees of structural damage. Furthermore, inter-story deformation can lead to varying levels of damage to non-structural components, all of which significantly influence the overall recoverability performance of the structure [27,28]. Therefore, it is essential to comprehensively evaluate the aggregate losses of both structural and non-structural components in order to accurately assess the post-earthquake recoverability of the structure.

6.1. Establishment of Performance Model

The FEMA P-58 [29] recommended tool, PACT, is employed to evaluate the resilience of the SCPC frame. The repair cost for the entire building is estimated at $310 per square foot, based on actual conditions. The building is designated for office use, and the population model corresponds to the commercial office building population model included in PACT. The maximum number of workers allowed for repair work is set at 0.02 persons per square meter, with a maximum capacity of 25 workers per floor.

Structural component performance groups are determined based on their actual quantity and distribution within the building. The Normative Quantity Estimation Tool recommended by PACT is used to estimate the types and quantities of non-structural components based on floor area and occupancy type. The fragility curves for non-structural components utilize the built-in dataset of PACT. Repair costs for both structural and non-structural components are defined in accordance with the data recommended by FEMA P-58 [29], derived from average repair data collected in Northern California in 2011.

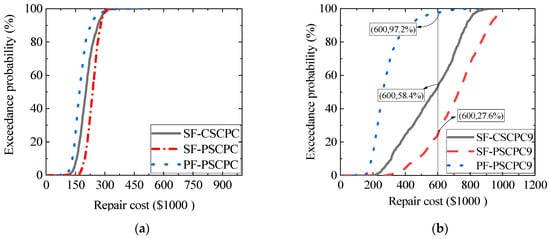

6.2. Repair Cost Analysis

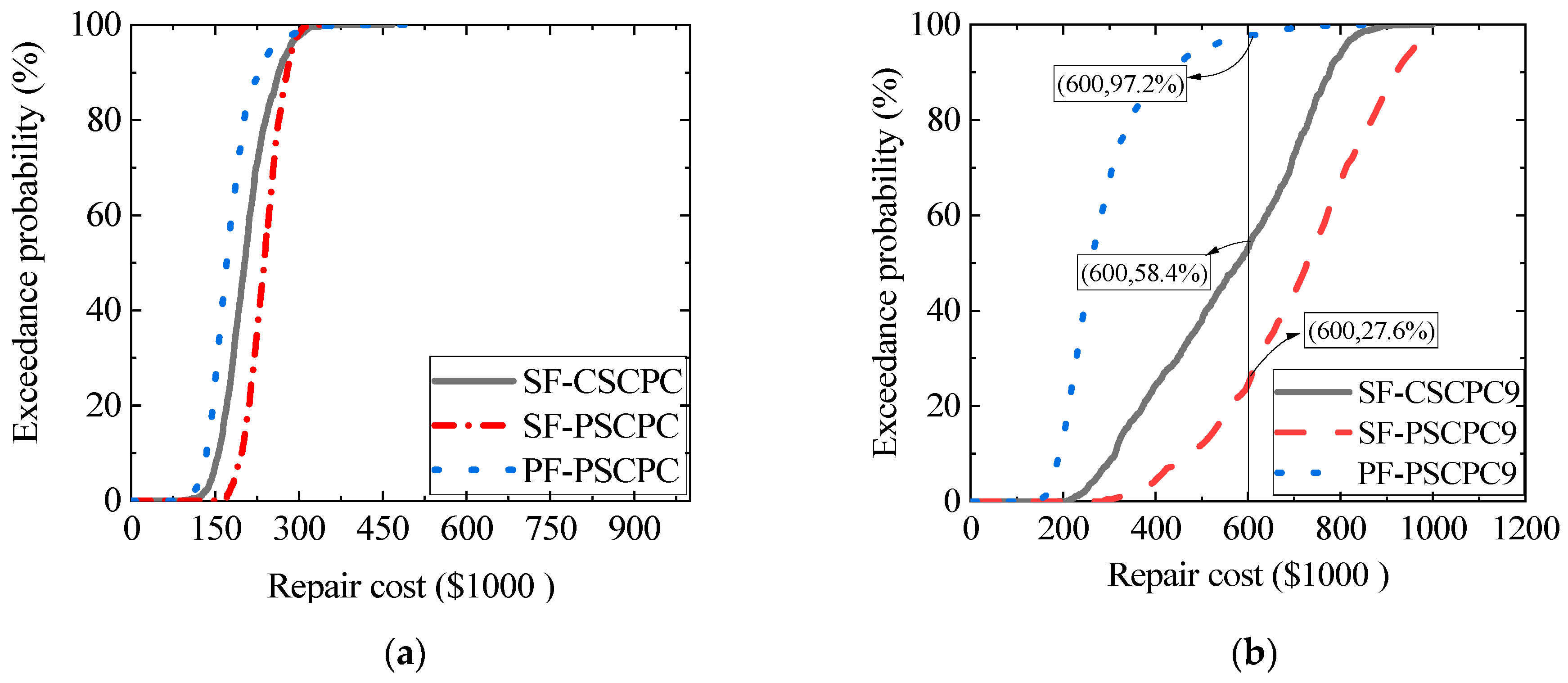

Using the nine-story frame as an example, the post-earthquake repair costs for three structures at the DBE and MCE seismic levels are analyzed. Figure 13 illustrates the performance functions of the SF-CSCPC frame, SF-PSCPS frame, and PF-PSCPC frame at both the DBE and MCE seismic levels. The horizontal axis represents the required post-earthquake repair costs, while the vertical axis indicates the exceedance probabilities. The analysis reveals that at the DBE seismic level, the repair cost for the SF-PSCPS frame is slightly lower than that of both the SF-CSCPC frame and the PF-PSCPC frame. However, at the MCE seismic level, the repair costs for the three structures exhibit significant variability. For example, at a repair cost of $600,000, the exceedance probability for the SF-PSCPC frame is only 27.6%, whereas the exceedance probabilities for the SF-CSCPC frame and the PF-PSCPC frame are 58.4% and 97.2%, respectively.

Figure 13.

The performance functions under DBE and MCE seismic levels. (a) DBE seismic level; (b) MCE seismic level.

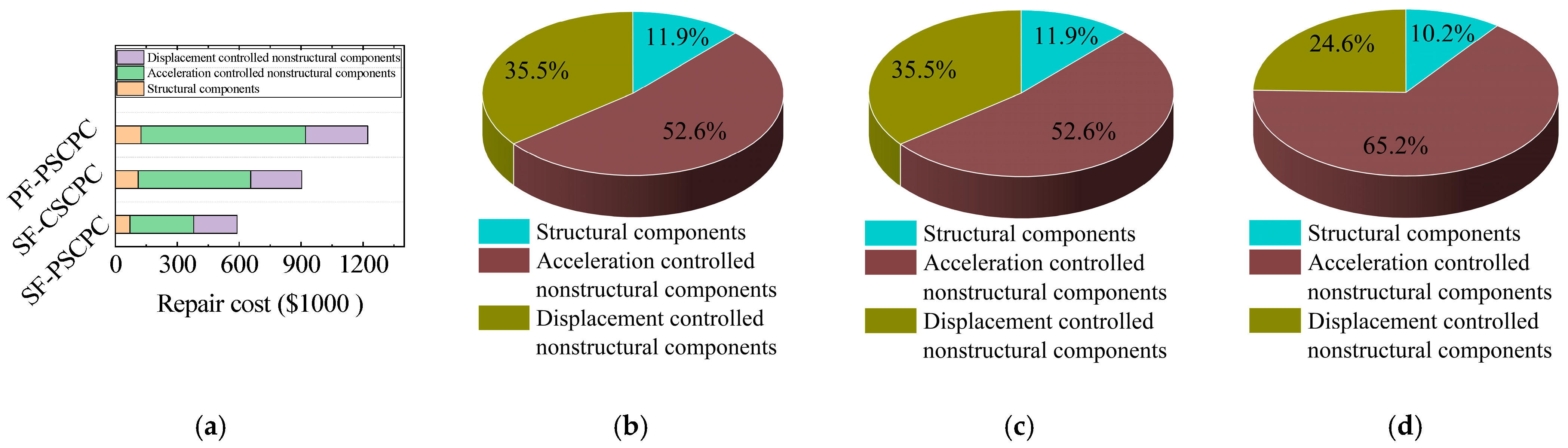

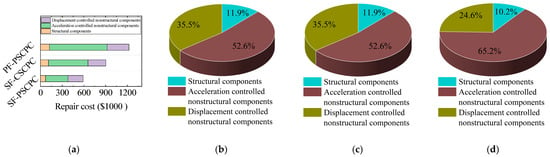

Figure 14 examines the economic investment required for the three structures following an earthquake at the MCE seismic level. Additionally, since structural components, acceleration-controlled nonstructural components, and displacement-controlled nonstructural components are typical in building structures, this analysis also considers the proportion of economic investment needed for the repair of these three component types at the MCE seismic level. Overall, the total economic investment for the SF-PSCPC frame is the lowest, while the post-earthquake total economic investments for the SF-CSCPC frame and PF-PSCPC frame are 53.2% and 87.4% higher than that of the SF-PSCPC frame, respectively.

Figure 14.

Repair cost of structures under MCE seismic level. (a) Total repair cost; (b) Repair cost for SF-PSCPC; (c) Repair cost for SF-CSCPC; (d) Repair cost for PF-PSCPC.

From Figure 14b–d, it is evident that the damage to the structural components is minimal, resulting in the lowest repair costs. The post-earthquake losses for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components are the most significant. Notably, the post-earthquake repair cost for the acceleration-controlled nonstructural components in the PF-PSCPC frame reaches $183,308, accounting for 65.2% of the total economic investment. In contrast, the repair costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components in the SF-PSCPC frame, although exceeding 50% of its total post-earthquake repair costs, amount to only $183,308, accounting for 65,271,255, which is 157% lower than the post-earthquake repair costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components in the PF-PSCPC frame. Additionally, the post-earthquake loss costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components in the SF-CSCPC frame are also 31.5% lower than those in the PF-PSCPC frame. This indicates that the sloped friction energy dissipators, due to their substantial energy dissipation capability, have significantly reduced the post-earthquake economic investment costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components. When combined with a low prestressing design, further reductions in these post-earthquake economic losses can be achieved.

It is important to note that assessing the recoverability of architectural functions for actual structures may involve more complex scenarios, and the repair costs, labor input, and fragility will inevitably differ from those in the examples presented in this study. However, since the primary goal of this study is to compare the post-earthquake repair performance of SCPC frames with different parameters, repair costs, labor input, and fragility remain constant variables. Thus, this analytical method can provide significant insights into the assessment of post-earthquake repair performance for real structures.

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under MCE seismic level, the average inter-story drift of the SF-PSCPC frame is decreased by about 25% in comparison to PF-PSCPC frame. This indicates that the arrangement of sloped friction energy dissipators enhances the secondary stiffness of the structure, thereby significantly reducing its inter-story deformation. In contrast, commonly used planar friction energy dissipators lack post-activation stiffness, which can result in excessive deformation of the structure during strong earthquakes.

- (2)

- Compared to the SF-CSCPC frames, the SF-PSCPC frames demonstrate reduced inter-story drift. In contrast, the SF-CSCPC frames may experience larger deformations during significant earthquakes, potentially leading to the fracture of some PT strands and resulting in increased inter-story drift.

- (3)

- The average residual inter-story drift of SF-PSCPC is only 0.12%, whereas that of the SF-CSCPC9 frame reaches 0.31% under MCE seismic conditions. It is because in partial SCPC frames, the inherent large deformation capacity of the PT strands reduces the likelihood of yielding, ensuring that the structure consistently possesses a reliable self-centering system that meets the performance goal of immediate occupancy following moderate earthquakes.

- (4)

- The repair costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components in the SF-PSCPC frame are 157% lower than those in the PF-PSCPC frame. The post-earthquake loss costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components in the SF-CSCPC frame are also 31.5% lower than those in the PF-PSCPC frame. This indicates that the sloped friction energy dissipators, due to their substantial energy dissipation capability, have significantly reduced the post-earthquake economic investment costs for acceleration-controlled nonstructural components. When combined with a low prestressing design, further reductions in these post-earthquake economic losses can be achieved.

It is crucial to acknowledge that, in the case of actual structures, more complex situations may emerge, leading to variations in repair costs, labor investments, and vulnerabilities compared to the examples discussed in this study. Thus, when evaluating the seismic performance of real structures, it is imperative to consider their actual conditions and to derive more accurate assessment results based on the analytical methods utilized in this research.

Author Contributions

S.W.: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Investigation, Project Administration; X.Z.: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Resources; G.Y.: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—Review & Editing; D.Z.: Validation, Data Curation, Supervision; L.H.: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Software; Y.W.: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research described in this paper was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52208480), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M731712). These supports are gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Sicong Wang, Xiaoyan Zhou, Guoqing Yuan and Dandan Zhang were employed by the company JSTI GROUP. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Huang, X.; Eatherton, M.R.; Zhou, Z. Initial stiffness of self-centering systems and application to self-centering-beam moment-frames. Eng. Struct. 2020, 203, 109890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Qiu, C.; Du, X.; Liu, H. Experimental tests and analytical model of double-action steel angles as external energy-dissipating devices. J. Struct. Eng. 2025, 151, 14330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzimas, A.S.; Kamaris, G.S.; Karavasilis, T.L.; Galasso, C. Collapse risk and residual drift performance of steel buildings using post-tensioned MRFs and viscous dampers in near-fault regions. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 14, 1643–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Gu, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, C.; Tong, L.; Xu, W. Seismic performance of a self-centering concrete frame with tuned viscous mass dampers based on mode tuning design. Structures 2025, 76, 108991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, A.; Xie, L. Development of design method for precast concrete frame with dry-connected rotational friction dissipative beam-to-column joints. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Hao, H. Lifetime seismic performance assessment on post-tensioned self-centering concrete frames considering long-term prestress loss. Eng. Struct. 2022, 262, 114321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Guo, T.; Koetaka, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, B.; Alam, M. Seismic performance of hybrid self-centering braces with structural and nonstructural damage control functions: Validation tests, computational modeling, and benefits evaluation. J. Struct. Eng. 2025, 151, 04025163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajil, N.; Srinivasan, S.; Santhanam, M. Self-centering of shape memory alloy fiber reinforced cement mortar members subjected to strong cyclic loading. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilzadeh, M.; Khaneghah, M.; Safari, P.; Broujerdian, V.; Ghamari, A. Investigating the seismic performance of disc spring-based self-centering bracing system. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 23, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tian, K.; Dong, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, F. Shaking table test of a frame structure retrofitted by externally-hung rocking wall with SMA and disc spring self-centering devices. Eng. Struct. 2021, 240, 112422. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Deng, E.; Gao, J. Experimental investigation on bending behavior of existing RC beam retrofitted with SMA-ECC composites materials. Materials 2022, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhu, L.; Dong, Y.; Luo, J.; Li, Z. Experimental and mathematical model of the variable friction adaptive self-centering energy dissipative brace. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 4660–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, W.Y.; Pampanin, S.; Palermo, A.; Carr, A.J. Self-centering structural systems with combination of hysteretic and viscous energy dissipations. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 39, 1083–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, W. Shaking table test and numerical simulation of a 1/2-scale self-centering reinforced concrete frame. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn 2015, 44, 1899–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, G.W.; Solberg, K.M.; Chase, J.G.; Mander, J.B.; Bradley, B.A.; Dhakal, R.P. Performance of a damage-protected beam–column subassembly utilizing external HF2V energy dissipation devices. Earth. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2008, 37, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, G.W.; Mander, J.B.; Chase, J.G. Modeling cyclic loading behavior of jointed precast concrete connections including effects of friction, tendon yielding and dampers. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2012, 41, 2215–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Y.; Fang, C.; Chen, Y.; Yam, M. Seismic robustness of self-centering braced frames suffering tendon failure. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 50, 1671–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, L.; Zeng, B.; Shi, Z.; Xie, Q. Analysis of seismic performance of self-centering concrete frame structures characterized by low prestressing and slope friction. Ind. Constr. 2024, 54, 38–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wen, H.; Jiang, K.; Liu, R. Seismic performance of partial self-centering prestressed concrete frames with friction dampers. Structures 2024, 62, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xue, J.; Luo, Z.; Huang, L. Manufacturing, testing and simulation of novel dual-stage energy-dissipation and self-centering friction damper. Eng. Struct. 2023, 297, 116947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, W.; Qu, B.; Alam, M.S. Self-centering energy-absorbing rocking core system with friction spring damper: Experiments, modeling and design. Eng. Struct. 2020, 225, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Liu, J.; Jiang, T.; Du, X. Experimental study on a steel self-centering rocking column with SMA slip friction dampers. Eng. Struct. 2022, 274, 115126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Furuta, T.; Xiong, H. Full-scale shaking table tests of cross-laminated timber structures adopting dissipative angle brackets and hold-downs with soft-steel and rubber. Eng. Struct. 2024, 313, 118292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Furuta, T.; Xiong, H. Experimental research on lateral performance of CLT shear walls with novel dissipative angle brackets and hold-downs. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applied Technology Council (ATC). FEMA P695, Quantification of Building Seismic Performance Factors; Federal Emergency Management Agency: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. A rapid identification framework for post-earthquake local damage of the multi-span interconnected slender equipment in substation. Eng. Struct. 2025, 333, 120124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.; Wang, W.; Tesfamariam, S. Effects of self-centering structural systems on regional seismic resilience. Eng. Struct. 2023, 274, 115125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Guan, D.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, M.; Yang, H. Seismic performance on PSPC beam-concrete encased CFST column frame with a built-in reduced beam section. Case. Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. FEMA P-58, Seismic Performance Assessment of Buildings: Volume 1–Methodology (FEMA P-58-1); Applied Technology Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).