Abstract

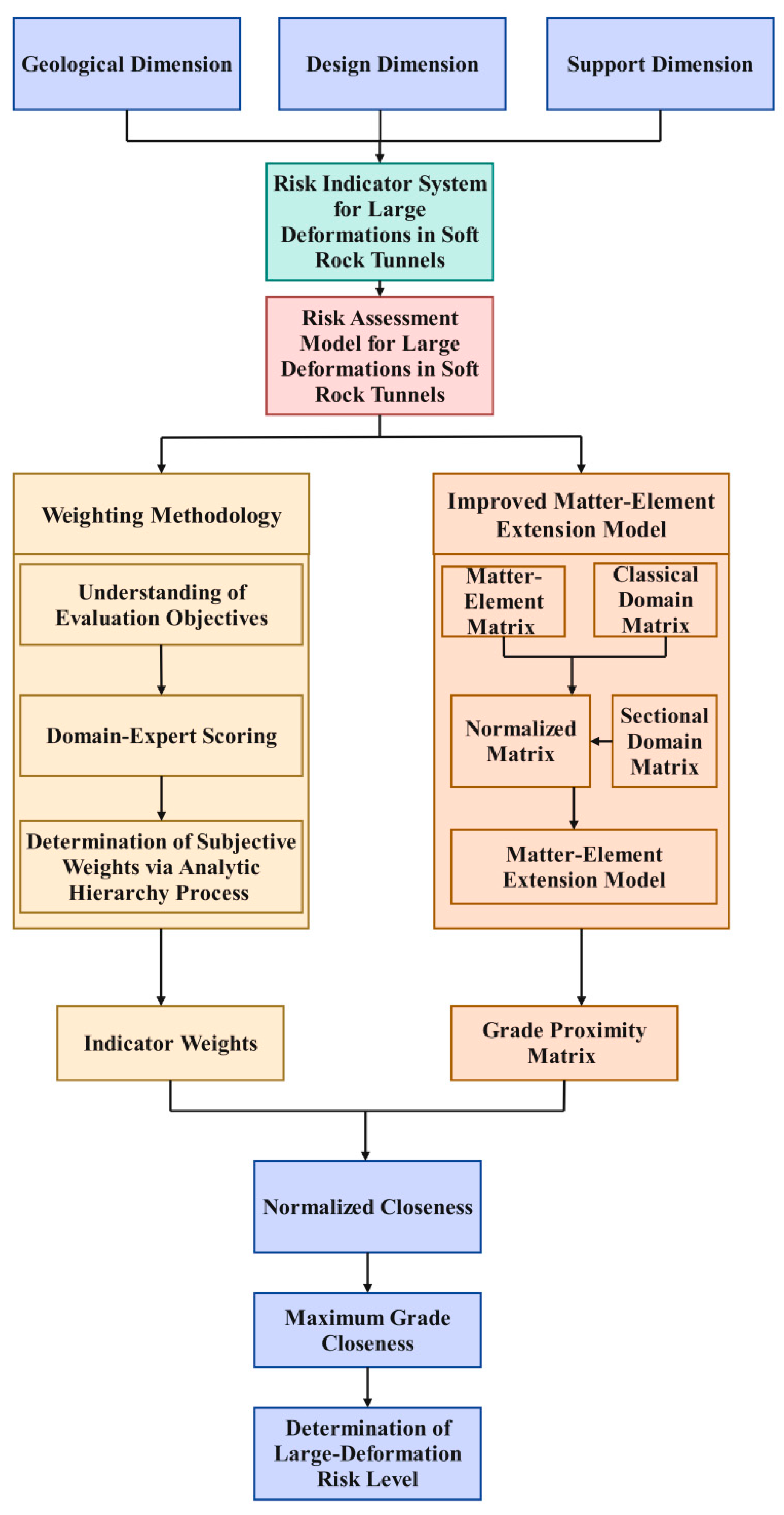

An integrated evaluation framework merging the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and an improved matter–element extension model based on asymmetric proximity is developed to classify large deformation risk levels in soft-rock tunnel construction. From geological surveys and real-time monitoring, ten core indicators spanning three dimensions—geology (surrounding rock grade, groundwater condition, strength–stress ratio, adverse geological condition), design (excavation cross-sectional shape, excavation span, excavation cross-sectional area), and support (support stiffness, support installation timing, construction step length)—are selected. AHP constructs and validates a judgment matrix to derive subjective weights for each indicator. Within a three-tier hierarchy (indicator, criterion, and target layers), the asymmetric proximity quantifies each tunnel’s proximity to the matter–element representing predefined risk levels. Risk levels are then automatically assigned by selecting the maximum composite proximity. Application to representative soft-rock tunnel cases confirms the method’s high accuracy, stability, and operational feasibility, closely matching field observations. This framework enables precise risk stratification and intuitive visualization, offering critical technical support for optimizing tunnel design and operations, and ultimately enhancing the safety, resilience, and sustainability of large-scale infrastructure.

1. Introduction

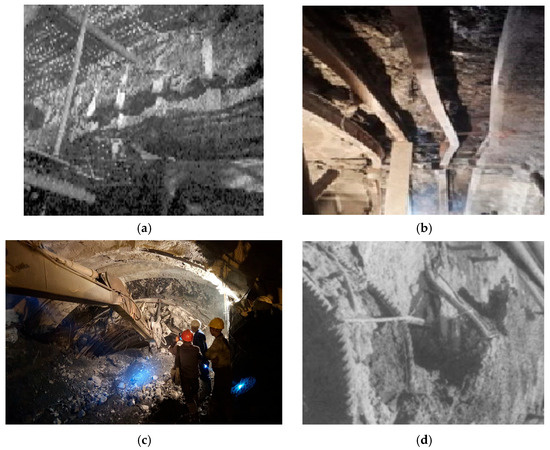

With the rapid expansion of high speed rail and highway tunnel projects in China, the number of soft-rock tunnels featuring large cross-sections and complex geological conditions has been steadily increasing [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. In particular, when traversing high-stress zones, water rich strata, and sections with low strength–stress ratios, the surrounding rock is prone to significant deformation and support instability that critically constrain both construction progress and safety management [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Therefore, the development of a risk assessment method that is both scientifically rigorous and operationally feasible is of great importance for enabling risk warning and control throughout the entire large deformation process of soft-rock tunnels, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Large-deformation failures in soft-rock tunnels. (a) Cracking and spalling of the sidewall concrete; (b) torsional deformation and fracture of the steel rib; (c) cracking induced by uplift of the tunnel invert; (d) The primary support encroached upon the designated boundary.

In the domain of large-deformation risk assessment for soft-rock tunnels, Bai et al. [15] developed a real-time updating model grounded in fuzzy multi-attribute decision-making (FMADM) theory, enabling monitoring-driven, dynamic adjustment of indicator weights. However, within FMADM, the distance–risk relationship is quantified using a symmetric membership function, which consequently reduces the method’s discriminative capacity. Bai et al. [16] identified the key factors by means of data envelopment analysis and evaluated them with a normal cloud model. However, the indicators were treated as independent, so the influence of coupling terms on the correlation degree was omitted. Zhang et al. [17] demonstrated that a CNN-LSTM architecture can deliver high-precision early-warning predictions. However, its limited interpretability and the uncontrollable nature of its weights hinder its ability to provide transparent decision support for construction planning. The game theoretic cloud model proposed by He et al. [18] mitigates the conflict between subjective and objective weight. However, symmetric correlation function is still employed, which renders the model insufficiently sensitive to risk stratification within the extreme high-risk interval. A microseismic monitoring–numerical coupling method was employed by Sun et al. [19] to achieve in-situ dynamic risk identification. However, the approach remains highly dependent on the density and configuration of the sensor network. Discrete–continuum coupled simulations were conducted by Deng et al. [20] to partition and predict large deformations, yet the computational expense was substantial.

To address these shortcomings, this study leveraged extensive field geological investigations and construction monitoring data. First, ten core evaluation indicators were selected across three dimensions: geology (surrounding rock grade, groundwater condition, strength–stress ratio, adverse geological condition), design (excavation cross-sectional shape, excavation span, excavation cross-sectional area), and support (support stiffness, support installation timing, construction step length). An improved analytic hierarchy process was then employed to assign subjective weights and conduct consistency checks for each indicator, thereby ensuring a scientifically sound and reasonable weight distribution. Second, a three-tier evaluation system—comprising an indicator layer, criterion layer, and target layer—was constructed. An innovative matter–element extension model based on asymmetric proximity was introduced, and directional quantification techniques were applied to calculate the proximity between evaluation units and the matter–element of various risk levels, overcoming the limitations of traditional symmetric measures. Finally, subjective weights and asymmetric proximity were integrated to achieve precise risk classification and visual representation of large deformation risks in soft rock tunnels.

Application results from representative cases demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms existing traditional evaluation models in terms of accuracy and stability. It effectively addresses the risk management requirements for large deformation in soft-rock tunnels under high stress, water rich, and low strength stress ratio. The findings provide a novel technical approach and practical pathway for the risk management of soft-rock tunnels in complex geological settings, thereby contributing to the enhancement of construction quality and operational safety of soft-rock tunnels in China.

2. Establishment of the Evaluation System

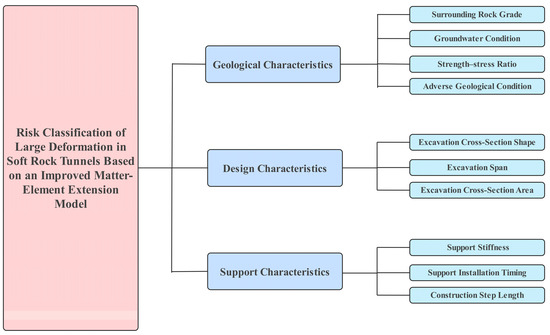

2.1. Construction of the Indicator System

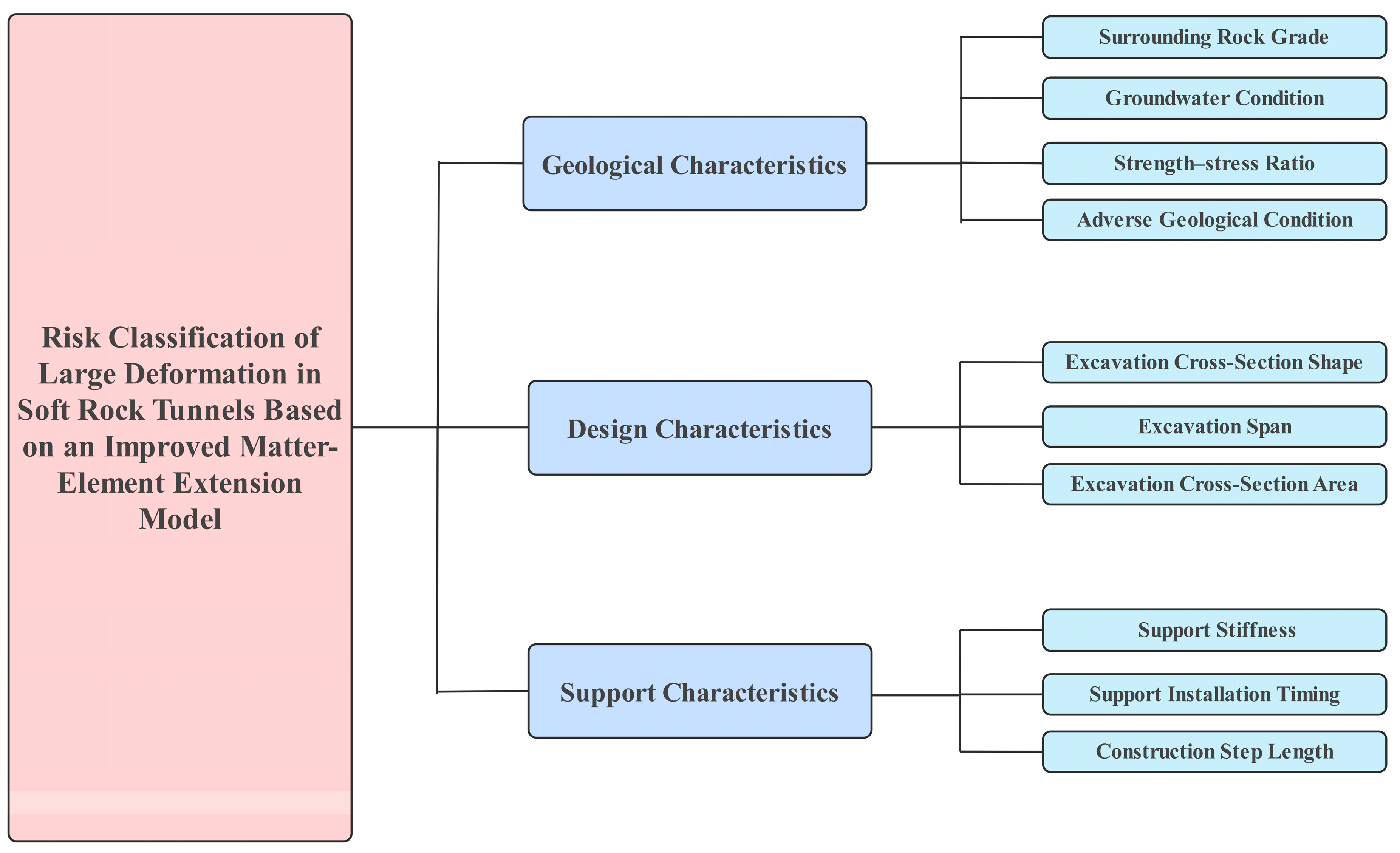

To scientifically and systematically classify large deformation risks in soft-rock tunnels, the evaluation indicator system was constructed based on an improved analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and an improved matter–element extension model incorporating asymmetric proximity. The system covers three dimensions: geological characteristics, design characteristics, and support characteristics. The geological characteristics dimension focuses on surrounding rock stability and hydromechanical coupling effects; the design characteristics dimension emphasizes the influence of excavation geometry on stress redistribution; and the support characteristics dimension considers the effects of support stiffness. The selected indicators combine quantitative with engineering decision-making, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent AHP and matter–element extension evaluation.

Indicator selection was guided by the principles of scientific rigor, systematic coverage, and independence. Drawing on both domestic and international research findings in tunnel engineering, the key factors affecting large deformation risks in soft-rock tunnels were screened.

2.1.1. Geological Characteristics

The geological characteristics dimension constitutes the foundation for evaluating the stability of soft-rock tunnels. It focuses on the intrinsic properties of the surrounding rock. In view of the pronounced impact of geological conditions on large deformations in soft-rock tunnels, the following indicators are selected:

Surrounding rock grade: classified comprehensively on the basis of lithology. It represents the principal indicator of tunnel stability.

Groundwater condition: encompassing the hydrogeological condition. It is a key factor controlling tunnel deformation.

Strength–stress ratio: the ratio of the rock mass uniaxial compressive strength to the prevailing in-situ stress. It serves as a critical factor in large deformations.

Adverse geological conditions: includes fault zones, karst cavities, and weak interlayers, all of which can trigger local or global instability in the surrounding rock.

2.1.2. Design Characteristics

The design characteristics dimension focuses on the influence of excavation geometry on stress redistribution and deformation responses of the surrounding rock, and therefore selects design parameters that are closely linked to large deformations:

Excavation cross-section shape: The geometric profile controls the formation of the pressure arch and stress concentration, with failure patterns and stress redistribution.

Excavation span: The span directly determines the height of the pressure arch, thereby influencing the magnitude of deformation and the corresponding support requirements.

Excavation cross section area: The excavation area forms the basis for adjusting support design parameters and has a significant impact on both construction methodology and deformation forecasting.

2.1.3. Support Characteristics

The support characteristics dimension focuses on the capacity of the support system to restrain the deformation of the surrounding rock. In view of the deformation encountered in soft-rock tunnels, the following support indictors are adopted.

Support stiffness: The support stiffness controls the deformation of the support system. Higher stiffness facilitates the rapid development of a load-bearing arch and effectively suppresses displacements.

Support installation timing: Whether support is installed promptly or belatedly alters the unloading path of the surrounding rock. Selecting an optimal installation timing maximizes control over deformation.

Construction step length: The length of each excavation step controls the rate at which the support ring is closed and the timing for rock–mass stabilization. The shorter construction step length mitigates the accumulation of deformation during construction.

By hierarchically arranging the foregoing dimensions and indicators, a three-tier structure—comprising an indicator layer, a criterion layer, and goal layer (Figure 2)—was established, thereby furnishing structured input for the subsequent AHP method and for evaluation with a matter–element extension model based on asymmetric proximity.

Figure 2.

Indicator System for Risk Assessment of Large Deformation in Soft-Rock Tunnels.

2.2. Classification of Evaluation Indicator

Based on the dimensions of geology, design, and support, an evaluation indicator system was developed to classify large deformation risks in soft-rock tunnels. The geological indicators include surrounding rock grade, groundwater condition, strength–stress ratio, and adverse geological conditions; the design indicators encompass excavation cross section shape, excavation span, and tunnel cross section area; and the support indicators consist of support stiffness, support installation timing, and construction step length. By combining the weights of these indicators—determined via the AHP method—with the results of a matter–element extension model improved by asymmetric proximity, the risk levels were delineated into five grades (I–V)(Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk-Level Classification for Large Deformation in Soft-Rock Tunnels.

Indicator values are decisive for assessing the risk grades of large-scale tunnel deformations. To eliminate subjective bias and enhance the scientific rigor and operability of the scoring, the selected geological, design, and support indicators were classified into five grades (I–V) based on quantification principles, drawing extensively on the Highway Tunnel Rock Mechanics Classification Standard (JTG/T 5128-2014), the Rock Mechanics Parameter Classification Standard (GB/T 50266-2013) [21,22], and relevant domestic and international studies, with each grade defined by specific numerical ranges or qualitative descriptions (see Table 2). In subsequent comprehensive evaluations, researchers may assign precise values to each indicator using project-specific data, thereby ensuring the objectivity, reliability, and reproducibility of the assessment results.

Table 2.

Influencing Factors and Scoring Criteria for Evaluation Indicators of Large-Deformation Risk in Soft-Rock Tunnels.

2.3. Evaluation Method

2.3.1. Calculation of Indicator Weights

To determine the relative importance of each evaluation indicator in the overall risk classification objectively and scientifically, the AHP approach was adopted. Expert scores were integrated into a judgment matrix, and the geometric mean method was employed to compute the indicator weights. A consistency check was then performed to ensure the reliability of the resulting weights [23,24,25].

- ●

- Hierarchical Structure Division

A three-level hierarchical model was constructed around the primary factors influencing large-deformation risks in soft-rock tunnels:

Overall objective, evel: Evaluation of large-deformation risk grades in soft-rock tunnels.

Criterion level: Geological characteristics, design characteristics, and support characteristics.

Indicator level: Geological characteristics: surrounding rock grade, groundwater condition, strength–stress ratio, and adverse geological condition.

Design characteristics: excavation cross-section shape, excavation span, and tunnel cross section area

Support characteristics: support stiffness, support installation timing, and construction step length

- ●

- Expert Scoring and Priority Relationship Judgment Matrix

- (1)

- Questionnaire Design and Expert Selection

Questionnaire design: A pairwise-comparison questionnaire covering all secondary indicators was developed, accompanied by detailed indicator definitions, criterion explanations, and scoring guidelines to ensure that experts evaluate based on a consistent information set.

A total of 50 experts were invited to participate in this study, including 16 from the design sector (32%), 17 from the construction sector (34%), and 17 from academia (34%). Equal weighting was applied to each expert to prevent any individual opinion from disproportionately influencing the results.

- (2)

- Relative Importance Scale

To quantitatively capture experts’ judgments on the relative importance between any two indicators i and j, an improved 1–9 scale was employed to assign the relative importance value aij, as follows:

1 indicates equal importance; 3, 5, 7, and 9 denote moderate importance, strong importance, very strong importance, and extreme importance, respectively; 2, 4, 6, and 8 serve as intermediate judgments between adjacent odd-numbered ratings (e.g., 2 signifies slightly more important than 1 but less than 3; 4 lies between 3 and 5; and so forth).

- (3)

- Construction of the Judgment Matrix

For all secondary indicators within the three dimensions of geology, design, and support, judgment matrix A = (aij) was constructed, where each element aij denotes the relative importance of indicator i compared to indicator j. Reciprocity is ensured (aji = 1/aij), and all diagonal entries are set to unity (aii = 1).

- (4)

- Weight Calculation and Consistency Test

For each judgment matrix A = (aij)n × n, the following procedures were carried out to derive sublevel indicator weights and to assess consistency:

Weight Estimation by the Product Method

The product of all elements in the i-th row was computed:

The n-th root of Mi was taken to obtain wi and geometric mean normalization:

Maximum Eigenvalue Calculation

The maximum eigenvalue was employed to assess the consistency of the judgment matrix. Consistency Index (CI) Computation

The consistency ratio (CR) was employed to assess matrix consistency. A CR value below 0.1 indicates that consistency has been satisfied; otherwise, the matrix must be adjusted or re-evaluated.

Final Weight Vector

w1–w11 are the weights derived using the AHP method.

W = [w1,w2,w3,wj,…,w11]T

2.3.2. Improved Matter–Element Extension Model

The matter–element extension model was improved by incorporating asymmetric proximity. In this model, each evaluated tunnel is represented as a matter–element. By defining classical domains for each assessment level and a joint domain spanning the entire quantitative range, a refined evaluation of large-deformation risk levels in soft-rock tunnels is achieved [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

- ●

- Construction of Matter–Element Matrices

(1) Let the object under evaluation be Mx, and let there be n evaluation indicators c1, c2, c3, c4…, cn with corresponding values Vx1, Vx2…, Vxn. The matter–element for M is then represented by the matrix Rx as follows:

(2) Assuming that M can be classified into z evaluation grades, each grade Mⱼ together with its n indicators and their value ranges defines a classical domain. The classical-domain matter–element matrix for grade j is given by:

Here, c1, c2, …, cₙ denote the n indicators, and vⱼ1, vⱼ2, …, vⱼₙ specify the value ranges of these indicators at grade j of the classical domain. Each interval (aⱼᵢ, bⱼᵢ) defines the numeric range of indicator i for grade j, where i = 1, 2, …, n and j = 1, 2, …, z.

(3) The overall quantitative range of the evaluation indicator—termed the joint domain—is defined as the union of the value ranges of the indicators across all assessment levels. The joint-domain matter–element matrix Rp is presented in Equation (8)

In the equation, Vp1, Vp2, …, Vpn are defined as the value ranges of the n evaluation indicators c1, c2, …, cn, which together constitute the joint domain. The interval (api,,bpi) is employed to denote the magnitude range of Pji.

- ●

- Normalization Processing

(1) During evaluation using the matter–element extension model, if an indicator’s measured value falls outside the joint domain range, the correlation function cannot be employed to compute the correlation degree. Consequently, the model must be improved by normalizing the evaluated matter–element matrix, the classical domains, and the joint-domain matter–element matrix. The improved evaluated matter–element matrix is presented in Equation (9)

(2) The normalized classical-domain matter–element matrix is defined as:

(3) The normalized joint-domain matter–element matrix is defined as:

- ●

- Proximity Calculation

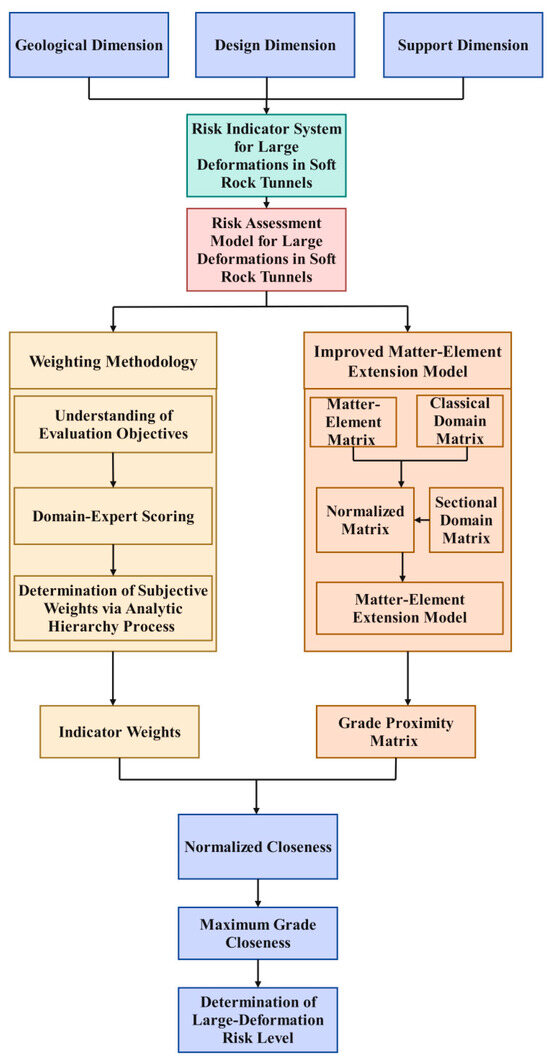

The maximum membership principle is typically employed in the matter–element extension model to determine the grade of an evaluation object. However, the inherent fuzziness of certain objects’ boundaries may result in information loss and thus distort the evaluation outcomes. To achieve more accurate results, an asymmetric proximity measure is adopted in lieu of the maximum membership principle,. as shown in Figure 3

Figure 3.

Level Assessment Framework for Large Deformations in Soft-Rock Tunnels.

Proximity is a concept in fuzzy mathematics that quantifies the degree of nearness between two fuzzy subsets. In this study, proximity is applied to measure how closely the risk grades defined for large deformation in soft-rock tunnels correspond to each other.

The proximity kj(x) between the x-th evaluated matter–element and the j-th evaluation grade is defined by Equation (12).

In Equation (12), wi denotes the weight of the i-th evaluation indicator; n is the total number of evaluation indicators; and Dj represents the distance between the i-th indicator value of the x-th evaluated matter–element and its corresponding joint domain.

The proximities between all evaluated matter–element and all evaluation grades were calculated using Equation (14). These proximity values were then subjected to min–max normalization to amplify the distinctions between each matter–element and its corresponding grades, thereby enabling more precise grade determination.

- ●

- Evaluation Grade Determination

The evaluation grade for each matter–element is determined by selecting the grade corresponding to its maximum proximity value; Equation (15) indicates that the x-th matter–element is most proximate to grade j′. After min–max normalization, the grade associated with a proximity value of 1 is adopted as the final evaluation grade

3. Example Applications

3.1. Risk Assessment of Large Deformations in Soft-Rock Tunnels

In this study, an extension model of matter–element was enhanced by incorporating the asymmetric proximity to achieve refined risk classification for large deformations in soft-rock tunnels. To verify the model’s applicability and reliability, four representative soft-rock tunnel cases—Xinchengzi, Xinlian, Muzhailin, and Gonghe—were selected. All four tunnels are situated within weathered, weak surrounding rock zones and are affected by adverse geological conditions, including fault-fracture zones together with well-developed groundwater and diverse construction scenarios. Comparative analysis of the measured deformations from these cases demonstrated that the model can accurately delineate risk classification differences arising from geological heterogeneity, thereby providing a scientific basis for proactive control and safety management during construction under complex hydrogeological conditions. In the Xinchengzi, Xinlian, and Gonghe tunnels, severe lining cracking and structural deformation were observed, whereas a tunnel collapse occurred at Muzhailin.

Based on actual large-deformation data for soft-rock tunnels collected from the literature, a comprehensive evaluation procedure encompassing indicator quantification and risk classification was established. First, ten evaluation indicators were selected: geological indicators (surrounding rock grade, groundwater condition, strength–stress ratio, and adverse geological conditions), design indicators (excavation cross section shape, excavation span, and tunnel cross section area), and support indicators (support installation stiffness, support timing, and construction step length). Subjective weights for these indicators were determined using an improved AHP.

Next, an improved matter–element extension model based on the asymmetric proximity was used to construct the matter–element matrix, and the proximity between each evaluation unit and the standard matter–element for different risk levels was calculated. Finally, risk classification for large deformation was performed based on the comprehensive proximity values.

3.2. Determination of Indicator Weights

A panel of fifty tunnel-engineering specialists—from design, construction, operation and maintenance organizations, and academia—was convened to assign weights to ten evaluation indicators using the 1–9 scale method. After each pairwise comparison of the indicators had been completed by the experts, a judgment matrix was constructed based on an improved AHP. Inconsistent judgments were then eliminated via a consistency test, yielding optimized weights for each indicator and thus providing a robust weighting foundation for the subsequent evaluation using the improved matter–element extension model with asymmetric proximity, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Weights of Evaluation Indicators.

3.3. Construction of the Matter–Element Matrix

Based on the improved matter–element extension model, the risk of large deformation in soft rock tunnels was classified into five levels (I–V), with higher levels indicating greater risk. The classical domains corresponding to each risk level were defined in accordance with the physical significance and quantitative characteristics of the geological, design, and support indicators, ensuring that the classification criteria are both scientifically rigorous and practically applicable.

Normalized Joint-Domain Matter–Element Matrix:

3.4. Determination of Risk Levels

3.4.1. Normalization of Proximity Intervals

To enhance the distinguishability among tunnel risk levels, the lower and upper bounds of the proximity intervals for Levels I–V were subjected to min–max normalization, mapping each proximity interval to the [0, 1] range. This approach is commonly adopted in multi-criteria decision analysis. It offers computational simplicity, efficiency, and robustness to outliers, thereby providing a stable and reliable data foundation for subsequent assessments.

3.4.2. Comprehensive Assessment and Level Determination

The normalized proximity values for each level were determined by the “maximum normalized proximity” method: the category associated with the highest normalized proximity value across all levels was directly selected, succinctly reflecting the most prominent risk under current conditions.

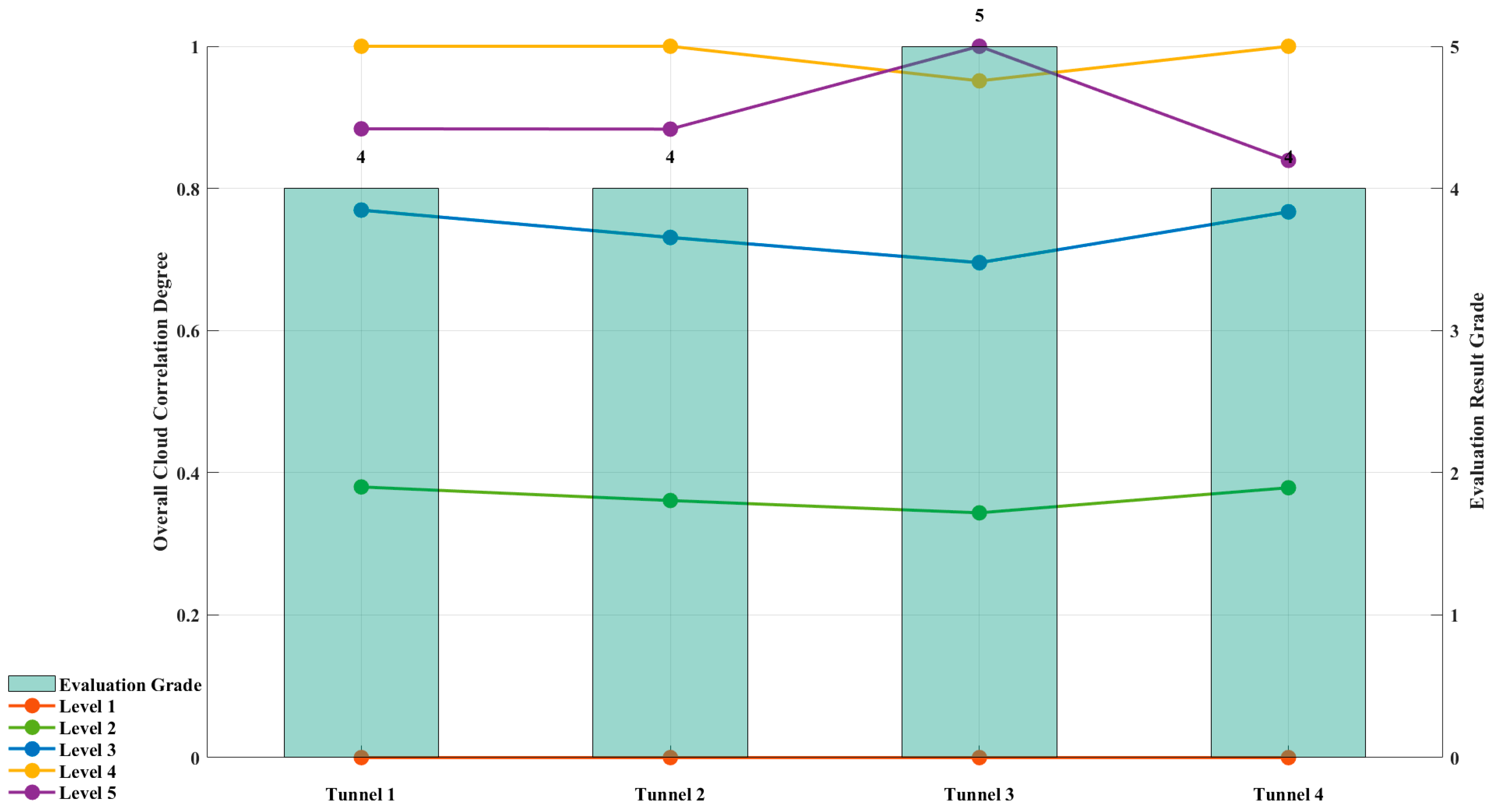

4. Model Results

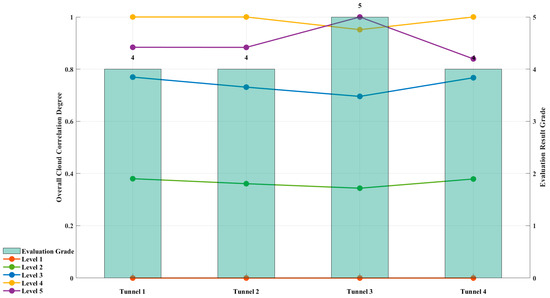

Table 4 summarizes the proximity values, normalized proximity values, and final evaluation grades for four typical soft-rock tunnels—Xinchengzi, Xinlian, Muzhailing, and Gonghe—across risk levels I–V, as shown in Figure 4.

Table 4.

Risk Ratings for Each Tunnel.

Figure 4.

Evaluation Results of the Improved Matter–Element Extension Model.

As shown in the table, the maximum normalized proximity values for the Xinchengzi, Xinlian, and Gonghe tunnels all fall within the Level IV range. They are therefore classified as Level IV. The Muzhailin Tunnel, however, reaches a normalized proximity of 1.0000 in Level V and is thus classified as Level V. These findings are in close agreement with field observations, thereby validating the accuracy and reliability of the model-based risk grading method for large deformations in soft-rock tunnels, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

In-situ photographs of the four tunnels (a) Xinchengzi Tunnel; (b) Xinlian Tunnel; (c) Muzhai-ling Tunnel; (d) Gonghe Tunnel.

4.1. Evaluation Accuracy and Recognition Precision

Extreme state detection: Field monitoring at the Muzhailin Tunnel confirmed a Level V large deformation, with a normalized proximity value of 1.0000 within the Level V interval. The model likewise identified it precisely as Level V, with no false positives or false negatives.

Consistency verification: The maximum normalized proximity values for the Xinchengzi, Xinlian, and Gonghe Tunnels all fall within the Level IV interval, and the model’s classifications are consistent. These results closely match the field’s Level IV assessments, demonstrating the robustness of our model under varying geological and operational conditions.

4.2. Continuity and Sensitivity

The asymmetric proximity maintains monotonic continuity when factors exceed their defined ranges, without exhibiting sudden jumps or discontinuities, thereby effectively avoiding the instability issues encountered with conventional symmetric proximity functions outside their domains. Empirical results indicate that this algorithm exhibits high sensitivity to variations at factor boundaries, promptly reflecting minor fluctuations in the tunnel.

4.3. Multi-Indicator Fusion Capability

Min–max normalization is applied to the proximity intervals of each grade, thereby eliminating the influence of heterogeneous indicator scales and value ranges. This approach also demonstrates strong robustness against outliers.

The “maximum normalized proximity” method is employed to simplify the multi-indicator fusion process into a single-objective decision. This method not only ensures efficient and reproducible evaluation computations but also renders the classification of risk levels more intuitive and transparent.

5. Comparison Between the Improved Matter–Element Model and the Traditional N1 Method

A systematic comparison is performed between the improved matter–element extension model based on the asymmetric proximity criterion (hereafter “the improved model”) and the classical N1 method across five dimensions: methodological principle, classification clarity, stability and consistency, evaluation accuracy and engineering applicability, and methodological innovation. This analysis is intended to underscore the advantages of the improved model in risk grading for large deformations in soft-rock tunnels.

5.1. Overview of the Traditional N1 Method

The traditional N1 method derives a composite evaluation value, NL, by extracting the maximum (max) and arithmetic mean (ave) from each factor’s indicator series. The evaluation value is calculated as:

where NL denotes the composite evaluation value from the N1 method, max denotes the maximum value among single-factor indices, and ave denotes their arithmetic mean. Owing to its computational simplicity and ease of implementation, the N1 method has been widely employed in tunnel and underground engineering risk assessments. However, its reliance on a single statistical measure impedes the capture of subtle multi-factor differences, often resulting in clustered risk classifications and insufficient resolution, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Classification Criteria for Risk Levels Based on the N1 Method.

Table 6.

Comparison of Evaluation Results between the N1 Method and the Improved Matter–Element Extension Model.

The NL-based risk-level classification criteria were defined as follows: Level I [0, 0.2), Level II [0.2, 0.4), Level III [0.4, 0.6), Level IV [0.6, 0.8), and Level V [0.8, 1].

When this method was applied to the four soft-rock tunnels—Xinchengzi, Xinlian, Muzhailin, and Gonghe—Tunnel 1 was classified as Level III, whereas Tunnels 2, 3, and 4 were classified as Level IV. This result exhibits a “high clustering, low resolution” pattern, making it difficult to capture short-term exceedances and subtle variations observed during field monitoring (see Table 6).

5.2. Classification Clarity and Boundary Sample Discrimination Capability

- (1)

- Fine Grained Classification

When applied to the four soft-rock tunnels—Xinchengzi, Xinlian, Muzhailin, and Gonghe—the improved model, centered on an asymmetric proximity criterion and refined by multi-layer fuzzy boundary calibration, enables detailed quantification of the continuous risk evolution process. Unlike the N1 method, which relies solely on extreme or mean values, the enhanced model fully exploits inter-factor correlations to achieve fine-grained differentiation of the risk level in the Xinchengzi Tunnel, accurately classifying it as Level IV, and likewise correctly identifying the Muzhailin Tunnel as Level V. These results align closely with the medium- to high-risk conditions observed in engineering practice.

- (2)

- Boundary Sample Robustness

Taking Tunnel 3 as an example, although the local factor briefly exceeded its limit, the improved matter–element extension model still yielded Grade V, whereas the conventional N1 method reverted to Grade IV. This contrast clearly demonstrates the method’s robust discrimination of boundary samples. The improved model does not “over-regress” or jump grades in response to transient limit exceedances, but maintains a sensitive and stable response to the actual risk state.

5.3. Stability and Consistency Assessment

- (1)

- Stability Analysis

To mitigate the impact of sporadic peaks or short-term extreme factor values, the improved model balances expert-derived weights, effectively suppressing the amplification of single extreme observations. In contrast, the N1 method is prone to domination by isolated spikes, resulting in significant deviations in its assessments.

- (2)

- Consistency Verification

Across four tunnel samples, the improved model’s outputs were highly consistent with both historical monitoring records and in-situ deformation. The Muzhailing tunnel—subject to prolonged, multi-factor exceedances—was correctly classified as Level V. The remaining three tunnels were all classified as Level IV, perfectly matching on-site observations and significantly outperforming the N1 method’s tendency toward classification clustering.

5.4. Evaluation Accuracy and Engineering Applicability

5.4.1. Evaluation Accuracy

Comparison with field observations revealed that the risk boundaries defined by the asymmetric proximity-based classification correspond closely with actual risk levels. Overall accuracy was substantially improved relative to the N1 method, exhibiting enhanced sensitivity to minor variations and enabling timely detection of potential risk.

5.4.2. Engineering Applicability

This method standardizes proximity values across all risk levels to the [0,1] range, accommodating differences in indicator scales and value ranges to facilitate direct comparison of tunnel risks. Moreover, the model offers high stability and data continuity, satisfying practical engineering implementation requirements.

5.5. Methodological Innovations and Prospects for Deployment

5.5.1. Asymmetric Proximity

To address the problem of conventional symmetric proximity measures beyond the classical domain, the proposed asymmetric proximity algorithm compensates for insufficient responsiveness, providing smooth and continuous mappings at classification boundaries and markedly enhancing sensitivity and stability under extreme conditions.

5.5.2. Hierarchical Fuzzy Boundary Correction

Fuzzy boundary corrections are applied hierarchically to account for uncertainties in the mechanical properties of the soft rock and to accommodate the effects of external indicator perturbations on the evaluation. This approach markedly reduces the subjectivity involved in selecting single factor thresholds, thereby enhancing the model’s generalizability and resistance to interference.

To balance the objectives of peak sensitivity and trend stability, this study integrates weights through a combined AHP method and expert scoring approach into the asymmetric proximity model, establishing a comprehensive weighted assessment workflow. This strategy enables rapid early warning of extreme deformation risks while smoothly reflecting overall risk evolution trends, providing a robust foundation for precise implementation and field promotion of risk grading in large deformations.

In summary, the improved matter–element extension model based on the asymmetric proximity demonstrates outstanding discrimination accuracy, stability, and engineering applicability in the risk grading of large deformations in soft-rock tunnels. Future integration with digital-twin frameworks and online monitoring platforms could enable real time data integration and early warning responses, further advancing the intelligence and automation of tunnel risk management.

6. Conclusions

The improved matter–element extension model, based on asymmetric proximity, was formulated to grade the risk of large deformations in soft-rock tunnels. It was subsequently validated on four representative tunnels—Xinchengzi, Xinlian, Muzhailing, and Gonghe. It was demonstrated that, under the combined influence of multiple factors, the proposed model discriminates risk levels with finer granularity and improved robustness, significantly surpassing the conventional N1 method and thus exhibiting broad applicability to engineering practice.

- (1)

- Ten key evaluation indicators were identified across three dimensions—geological characteristics, design characteristics, and support characteristics—including surrounding rock grade, groundwater conditions, strength–stress ratio, adverse geological conditions, excavation cross-section shape, excavation span, excavation cross-section area, support stiffness, support installation timing, and construction step length. These indicators underpin a comprehensive, hierarchical framework for assessing large deformations in soft-rock tunnels, thereby supplying rigorously quantified inputs for subsequent risk grading.

- (2)

- The matter–element extension model was innovatively enhanced by incorporating asymmetric proximity in place of the traditional maximum membership principle. Min–max normalization applied to the proximity intervals of each risk class produces smooth, continuous mappings at class boundaries, thereby mitigating information loss and abrupt transitions, and enabling the model to distinguish tunnel risk levels with greater precision.

- (3)

- Comparative experiments with the classical N1 method further confirmed the improved model’s superior evaluation accuracy, classification discriminability, and interference resistance. Field measurements closely matched on-site monitoring, and the model effectively captured transient exceedance and subtle variations. Moreover, its straightforward and efficient normalization process facilitates rapid field deployment, demonstrating strong potential for engineering-scale application. However, the method depends on expert-derived weights and overlooks construction dynamics. This limitation will be explored in greater depth in future research.

Author Contributions

S.M.: Original draft preparation, Software, Methodology. Y.X.: supervise, Resource. J.Q.: Conceptualization of this study, Methodology. J.L.: supervise, Resource. H.S.: supervise. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities of Chang’an University (300102213202).

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, W.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Zi, X. Mechanical properties of partially bonded rock anchors in squeezing large-deformation soft rock tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 147, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.-S.; Fu, H.-L.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Hou, W.-Z. Countermeasures against large deformation of deep-buried soft rock tunnels in areas with high geostress: A case study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 119, 104238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, E.; Zhang, W.; Lai, J.; Hu, H.; Xue, F.; Su, X. Enhancement of Cement-Based Materials: Mechanisms, Impacts, and Applications of Carbon Nanotubes in Microstructural Modification. Buildings 2025, 15, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, E.; Hu, H.; Lai, J.; Zhang, W.; He, S.; Cui, G.; Wang, K.; Wang, L. Deformation analysis of high-speed railway CFG pile composite subgrade during shield tunnel underpassing. Structures 2025, 78, 109193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Cui, G.; Lai, J.; Zhao, K.; Tang, K.; Qiang, L.; Jia, D. Influence of Fissure-Induced Linear Infiltration on the Evolution Characteristics of the Loess Tunnel Seepage Field. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 162, 106640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-K.; Lai, J.-X.; Song, Z.-P.; Xie, Y.-L.; Qiu, J.-L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L. Investigating fracture response characteristics and fractal evolution laws of pre-holed hard rock using infrared radiation: Implications for construction of underground works. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 161, 106594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Lai, J.; Su, X. Investigation of power-law fluid infiltration grout characteristics on the basis of fractal theory. Buildings 2025, 15, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Fang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Xue, B.; Yang, M.; Wang, N. GPR detection localization of underground structures based on deep learning and reverse time migration. NDT E Int. 2024, 143, 103043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Gong, J.; Deng, J.; Xu, W. Effects of Air Vent Size and Location Design on Air Supply Efficiency in Flood Discharge Tunnel Operations. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2023, 149, 4023050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, W.; Yin, X.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Yang, J. Experimental study on the performance of shield tunnel tail grout in ground. Undergr. Space 2025, 20, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Xin, T.; Zhenggang, H.; Minghua, H.; Hui, C. Measurement and Analysis of Deformation of Underlying Tunnel Induced by Foundation Pit Excavation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 8897139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhong, Z.; Ye, T.; Meng, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J.; Luo, S. Impact failure and disaster processes associated with rockfalls based on three-dimensional discontinuous deformation analysis. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2024, 49, 3344–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Q.; Nie, L.; Xue, Y.; Li, W.; Fan, K. Model Testing on the Processes, Characteristics, and Mechanism of Water Inrush Induced by Karst Caves Ahead and Alongside a Tunnel. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 5363–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Meng, S.; Sun, W.; Yuan, M.; Liu, X.; Nan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Sun, D.; Tao, J.; Li, J.; et al. Research on the risk assessment of the green construction of hydraulic tunnels based a on combination weighting-cloud model. Evol. Intell. 2025, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Xue, Y.; Qiu, D.; Yang, W.; Su, M.; Ma, X. Real-time updated risk assessment model for the large deformation of the soft rock tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 21, 04020234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Xue, Y.; Qiu, D.; Su, M.; Ma, X.; Liu, H. Analysis of factors affecting the deformation of soft rock tunnels by data envelopment analysis and a risk assessment model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 116, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Minghao, W.; Feng, D.; Jingchun, W. Risk classification assessment and early warning of large deformation of soft rock in tunnels based on CNN-LSTM model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.P.; Xu, Y.D.; Hu, Q.J.; Cai, Q.J. Assessment of Large Deformation Risk in Soft-Rock Tunnels Based on Game-Theory–Cloud Model. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2021, 58, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, N.; Xiao, P.; Sun, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Li, B. Characterizing large deformation of soft rock tunnel using microseismic monitoring and numerical simulation. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Liu, Q.; Liu, B.; Lu, H. Failure mechanism and deformation prediction of soft rock tunnels based on a combined finite–discrete element numerical method. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 161, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50266-2013; Standard for Test Methods of Engineering Rock Mass. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- GB/T 50218-2014; Standard for Engineering Classification of Rock Mass. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Hyun, K.-C.; Min, S.; Choi, H.; Park, J.; Lee, I.-M. Risk analysis using fault-tree analysis (FTA) and analytic hierarchy process (AHP) applicable to shield TBM tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 49, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezarat, H.; Sereshki, F.; Ataei, M. Ranking of geological risks in mechanized tunneling by using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP). Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 50, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, C.; Park, J.; Lee, I.-M.; Min, S. Probabilistic tunnel collapse risk evaluation model using analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and Delphi survey technique. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 120, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.-C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.-P.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, F.-J. Debris-flow hazard assessment based on stepwise discriminant analysis and extension theory. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2014, 47, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, Q.; Gong, D. Construction and implementation of matter-element matching model for soil heavy metal pollution evaluation. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2022, 109, 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Zhao, J.; Qi, S.; Feng, X. Evaluation of soil pollution by potential toxic elements in cultivated land in the Poyang Lake region based on an improved matter–element extension model. Forests 2022, 13, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bai, X.; Zhai, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, X.; Li, C.; Liu, K.; Wang, Q. Research on extension evaluation method of mudslide hazard based on Analytic Hierarchy Process–criteria importance through intercriteria correlation combination assignment of game theory ideas. Water 2023, 15, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caixia, T.; Zhongfu, T.; Jianbin, W.; Huiwen, Q.; Xiangyu, Z.; Zhenbo, X. Benefit analysis and evaluation of virtual power plants considering electric vehicles. EDP Sci. 2021, 248, 02024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Ma, B. Risk evaluation of tailings dam-break based on the extension matter-element model. EDP Sci. 2021, 253, 01056. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, G.; Niu, D.; Liang, Y. Core competitiveness evaluation of clean energy incubators based on matter-element extension combined with TOPSIS and KPCA-NSGA-II-LSSVM. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S. Debris flow risk mapping based on GIS and Extenics. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.C.; Zhao, B.T.; Xie, S.H.; Fan, H.B.; Wang, R.Q.; Qiu, J.L. Hydro-environmental evolution and mechanical response of support structures in loess-oilfield tunnels during water injection well leakage. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 166, 106971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).