1. Introduction

Pile or granular columns are commonly used to stabilize foundations composed of soft clay, silt, and loose sandy silt containing significant amounts of fine silt. This method has become one of the most frequently employed support techniques for structures capable of withstanding certain settlement, such as low-rise buildings, highway facilities, storage tanks, dams, and bridge abutments, owing to its low cost, effective results, and ease of installation. The advantages of stone columns include enhancing foundation stiffness, reducing settlement, prolonging settlement time, improving shear strength, and lowering liquefaction risk in soft soil layers [

1,

2]. In extremely soft soils with low undrained shear strength, the construction and utilization of conventional stone columns are nearly impossible due to insufficient lateral support. To address this issue, the column material can be encased with geosynthetics. This foundation system, initially introduced as geotextile-encased columns (GECs), has been successfully applied and widely recognized in engineering practice [

3,

4]. Sivakumar et al. introduced and investigated a similar concept based on geosynthetic-encased columns, employing sturdier and potentially harder alternatives to geotextiles [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In recent years, various field and laboratory studies have been conducted to evaluate the performance of geosynthetic-encased granular columns [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Applications of granular columns have involved different designs, such as partial and full encasement [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23], floating conventional columns and enclosed columns [

24,

25] and geosynthetic-reinforced layered piles [

26], which are non-enclosed columns reinforced by geosynthetic discs within their internal regions.

Currently, numerous scholars [

27,

28,

29] have focused on numerical simulations of geosynthetic-encased column composite foundations, achieving significant progress. Among these, some studies [

30] primarily focused on establishing numerical models and parameter selection to predict the mechanical properties and stability of column composite foundations. Murugesan and Rajagopal [

7,

8] evaluated the behavior of ordinary stone columns (OSCs) and geosynthetic-encased stone columns (ESCs) through numerical analysis. They reported that ESCs exhibit higher stiffness than OSCs and demonstrate reduced dependence of its bearing capacity on the strength of the surrounding clay soil. Khabbazian [

31] employed numerical analysis software to develop a numerical model of a composite foundation with encased gravel columns. This study analyzed the influence of various parameters—such as aspect ratio, mechanical properties of the gravel, and stiffness of the encasement material—on the bearing characteristics of the composite foundation. Tandel et al. [

32,

33] investigated the bearing capacity and deformation characteristics of composite foundations with encased gravel columns by examining the influence of geosynthetic stiffness through numerical simulations and field comparison tests, reaching conclusions consistent with laboratory experiments. Yoo [

34] conducted numerical analyses to examine the effect of sleeve length on the bearing characteristics of encased gravel column composite foundations. The study indicated that encasement of gravel columns effectively increases their bearing capacity while reducing settlement of the composite foundation. As the encasement length increases, both the bearing capacity of the encased gravel columns and the settlement of the composite foundation decrease. Pulko et al. [

35] conducted finite element analysis on encased column composite foundations based on elastoplastic theory, examining multiple influencing parameters. They concluded that changes in the area replacement ratio significantly affect the bearing capacity of the foundation.

However, the inherent nature of soft and liquefied soils is their low strength and high deformability, which prevents them from providing sufficient lateral confinement to the gravel column. Under loading, the column attempts to deform downward and expand outward, leading to lateral bulging or even shear failure [

36]. Chen et al. [

37] addressed key challenges in urban waste concrete composites through scientific innovation. By utilizing diverse urban wastes to enhance concrete workability and strength, their research paves the way for designing sustainable concrete materials with the required mechanical properties. Therefore, this study replaces crushed stone with RCA featuring a higher internal friction angle and interlocking effect. Using ABAQUS software (Abaqus 2023), a three-dimensional numerical model was established based on prior model test conditions. Through vertical loading analysis, the effects of column spacing, encapsulating material stiffness, and encasement length on the bearing characteristics of the RCAEC composite foundation were investigated.

2. Introduction to Composite Foundation Bearing Capacity Testing

This study employs numerical modeling to investigate the bearing capacity of composite foundations, with supporting experimental data drawn from prior model tests [

38]. The model box measured 2500 mm (length) × 2500 mm (width) × 1500 mm (height), with a width exceeding four times the maximum diameter of the loading plate, thereby satisfying boundary condition requirements for static load tests. Four types of nylon mesh with 1.5 mm apertures were used as encasement materials, manually sewn into sleeves matching the column diameter. The RCAECs were installed in liquefiable sandy soil obtained from Dongfang City, Hainan Province, with a maximum particle size of 5 mm. The RCA was obtained from C30 grade waste concrete and processed to a maximum particle size (dmax) of 10 mm. Laboratory tests indicated an internal friction angle of 42° for the aggregate. Grading analysis yielded a curvature coefficient (Cc) of 2.51 and a coefficient of uniformity (Cu) of 4.3. According to the Unified Soil Classification System, the sandy soil and RCA were classified as GP and SP, respectively. A 100 mm-thick hard layer composed of 5~10 mm crushed stone was used at the base. Loading followed the JGJ 79-2012 [

39], applied incrementally via a jack to avoid impact forces. The initial load was 10 kN, followed by 5 kN increments. Settlement readings were taken at 5, 10, 15, 15, and 15-min intervals during the first minute after loading, and subsequently every 30 min until stabilization before proceeding to the next stage.

3. Numerical Modeling

3.1. Model Description

The loading plate is modeled as a cylindrical element with a diameter of 0.64 m and a thickness of 0.02 m. The sandy soil layer is represented by a cuboid measuring 2.5 m × 2.5 m × 0.7 m, while the underlying stiff soil layer has dimensions of 2.5 m × 2.5 m × 0.15 m. The RCAEC is simulated as a cylinder with a diameter of 0.1 m and a length of 0.7 m, as depicted in

Figure 1.

In the numerical model, the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model was adopted for the stiff soil layer, sand layer, and RCAEC. To enhance computational convergence, an asymmetric solver was utilized in the analysis step. Surface-to-surface contact was defined with the circumferential surface of the RCAEC as the master surface and the surrounding sand as the slave surface. Similarly, the top surface of the stiff soil layer was set as the master surface interacting with the bottom surface of the RCAEC as the slave. The normal contact behavior was defined as “Hard” contact, while the tangential behavior was modeled using the penalty method with a friction coefficient of 0.3. To simplify the model and improve convergence, the interfaces between the loading plate and both the top of the RCAEC and the sand surface were defined as “Tie” constraints.

A surface-to-surface contact formulation was employed to simulate interactions between the geotextile encasement and the surrounding soil. The base of the model was fixed against vertical displacement, while the side boundaries were fixed against horizontal displacement. Due to strong interlocking and friction between the geotextile and the column material, no relative displacement was permitted at this interface; hence, no contact elements were defined internally. Contact was explicitly modeled only between the geotextile encasement and the sandy soil layer, allowing for possible relative slip, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The finite element model was discretized using 8-node linear brick (C3D8R) elements. A global seeding was first applied, followed by localized edge seeding in regions requiring higher computational accuracy, such as the vicinity of the geosynthetic-encased recycled concrete aggregate column, to create a refined mesh. Conversely, in areas farther from the column where precise results are less critical, a coarser mesh was adopted to enhance computational efficiency

Figure 3.

3.2. Material Properties

A three-dimensional finite element model was developed to simulate the behavior of dense sand beds and granular columns. The corresponding material parameters are summarized in

Table 1. The geosynthetic encasement was modeled using three-node shell elements with isotropic linear elastic material behavior. These elements are capable of resisting membrane forces but do not account for bending moments. The thickness assigned to the shell elements corresponds to that of the geotextile encasement used in the physical model tests.

All numerical simulations were conducted on a desktop computer equipped with an Intel® Core™ i7-12700 processor running at 4.90 GHz and supporting 32- and 64-bit operating systems.

3.3. Constitutive Model

The choice of constitutive models is critical for accurately representing geomaterial behavior. In this study, the Mohr–Coulomb and linear elastic models were employed to characterize different materials. The Mohr–Coulomb model was applied to the hard soil layer, the sandy soil layer, and the RCAEC. This model is suitable for capturing the shear strength of geomaterials, particularly their strain-softening behavior beyond the yield point, by incorporating strength parameters—cohesion (c) and internal friction angle (φ).

In the numerical implementation, the Mohr–Coulomb model assumes that the total strain before yielding is purely elastic (ε = εe). After yielding, the strain comprises both elastic and plastic components (ε = εe + εp). The model accounts for the evolution of strength parameters with accumulating plastic strain, thereby providing a more realistic simulation of the post-yield response of granular materials.

3.4. Validation of the Numerical Simulation Results

Based on the numerical simulation results, the contour plot of vertical displacement for the geosynthetic-encased recycled concrete aggregate column composite foundation is presented in

Figure 4.

To further validate the accuracy of the numerical model, the vertical stress of the composite foundation under the ultimate load state was analyzed.

Figure 5 shows the vertical stress contour of the composite foundation with a replacement ratio of 0.227. It can be observed that the stress is primarily concentrated in the geosynthetic-encased recycled concrete aggregate column, with only minimal stress distributed in the surrounding soil. Within the column, the stress is mainly focused at the top, while a portion is also transmitted to the bottom, which is consistent with the phenomena observed in the model tests. Overall, the settlement and vertical stress of the composite foundation obtained from the numerical model show good agreement with the experimental results, indicating that the present numerical model is capable of effectively simulating the bearing and deformation behavior of the geosynthetic-encased recycled concrete aggregate column composite foundation.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Influence of Encasement Length on the Bearing Characteristics of Composite Foundations

To evaluate the effect of encasement length on the bearing behavior of RCAEC composite foundations, a series of numerical models were established with identical parameters except for the encasement length. The numerical study comprised seven configurations: one unreinforced foundation, one composite foundation with an unencased column, and five RCAEC foundations with encasement lengths of 300 mm, 400 mm, 500 mm, 600 mm, and 700 mm. All columns had a length of 700 mm, a diameter of 100 mm, an encasement stiffness of 49.0 kN/m, and a center-to-center spacing of 300 mm. The corresponding numerical models were subjected to vertical loading simulations.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the vertical displacement and stress contours, respectively. The results show that under the same displacement level, longer encasement lengths lead to higher vertical stresses in the RCAEC, with stress concentration primarily observed in the upper 1–3 diameters. The bearing capacity was quantified as the load corresponding to a settlement of 50 mm [

10,

40]. The load–settlement curves for the columns are shown in

Figure 8.

As shown in

Figure 7, at a settlement of 50 mm, the column-top load of the composite foundation with RCAEC is consistently higher than that of the unencased column foundation, indicating a significant improvement in ultimate bearing capacity due to encasement. Moreover, the ultimate load capacity increases progressively with encasement length, rising from 8.45 kN for the unencased column to 10.80 kN for the fully encased (700 mm) case.

As shown in

Figure 8, when the column-top load is less than 3 kN, the settlement curves of composite foundations with varying encasement lengths are nearly identical, indicating that encasement length has a negligible influence on bearing capacity at low load levels. Once the column-top load exceeds 3 kN, the effect of encasement length becomes apparent: longer encasement leads to a gradual decrease in the slope of the load–settlement curve. Under the same load, settlements for encasement lengths of 300 mm and 400 mm are smaller than those for lengths of 500~700 mm, suggesting that encasements shorter than 400 mm do not fully mobilize the column’s bearing potential. In contrast, encasement lengths of 500 mm, 600 mm, and 700 mm result in significantly improved bearing performance.

To further quantify the influence of encasement length, the column-top load at a foundation settlement of 50 mm was extracted for each case (

Table 2). The relationship between this load and the encasement length-to-column length ratio is illustrated in

Figure 9. The results indicate that when the ratio is below 20%, increasing encasement length has little effect on bearing capacity. Between 20% and 94%, bearing capacity increases significantly with encasement length. Beyond 94%, however, further increases in encasement length yield no appreciable improvement, demonstrating that the effect of encasement length on column capacity is bounded.

4.2. Influence of Encasement Stiffness on the Bearing Characteristics of Composite Foundations

To evaluate the influence of encasement stiffness on the bearing behavior of RCAEC composite foundations, a series of numerical models were established with identical parameters except for the encasement stiffness. The numerical study included six configurations: one unencased column composite foundation and four RCAEC foundations with encasement stiffness values of 24.8 kN/m, 49.0 kN/m, 73.8 kN/m, and 102.2 kN/m. All columns had a length of 700 mm, a diameter of 100 mm, full-length encasement (700 mm), and a center-to-center spacing of 300 mm. The corresponding models were subjected to vertical loading simulations.

The resulting vertical displacement and stress contours are presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, respectively. The load–settlement curves for the columns are shown in

Figure 12, with the bearing capacity quantified as the load corresponding to a settlement of 50 mm.

Figure 12 shows that at a settlement of 50 mm, the column-top load of the RCAEC composite foundation is consistently higher than that of the unencased column foundation, confirming that encasement significantly improves the ultimate bearing capacity. With increasing encasement stiffness, the ultimate load capacity rises progressively—from 8.45 kN for the unencased column to 10.80 kN for the geotextile-encased column (102.2 kN/m stiffness) and 11.88 kN for the geomembrane-encased column.

When the column-top load is below 3 kN, the settlement curves for different encasement stiffnesses nearly coincide, indicating a negligible influence of stiffness at low load levels. Beyond 3 kN, however, the effect of encasement stiffness becomes evident, manifested by a gradual decrease in the slope of the load–settlement curve as stiffness increases.

To further quantify this relationship, the column-top loads corresponding to a settlement of 50 mm were extracted for different encasement stiffnesses (

Table 3). The variation in column-top load with encasement stiffness is illustrated by the fitted scatter plot in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 13, the bearing capacity of the RCAEC increases with encasement stiffness, albeit at a gradually diminishing rate. The results indicate that when the encasement stiffness reaches approximately 100 kN/m, the column’s bearing capacity attains a maximum value of 11.88 kN. Below this threshold, increasing the encasement stiffness effectively enhances both the column capacity and the overall performance of the composite foundation. Beyond 100 kN/m, however, further increases in stiffness yield no significant improvement in bearing capacity.

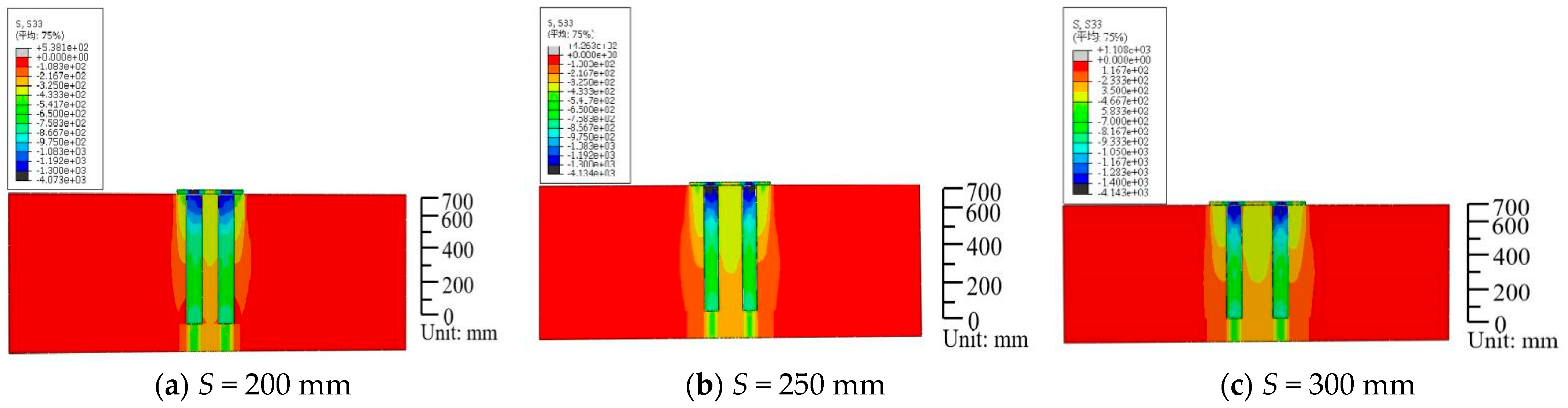

4.3. Influence of Column Spacing on the Bearing Characteristics of Composite Foundations

This section examines the effect of column spacing on the deformation and stress distribution of RCAEC composite foundations. While keeping other parameters—including column length, diameter, encasement length, and stiffness—constant, column spacings of 2 d, 2.5 d, and 3 d were considered (

S = 200 mm, 250 mm and 300 mm), corresponding to area replacement ratios (m) of 0.227, 0.145, and 0.101, respectively. The resulting stress and displacement contours under corresponding loading conditions are presented in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

Based on the numerical model of the composite foundation, the load–settlement curve for the column head was plotted. The ultimate load of the column was defined as the load corresponding to a settlement of 50 mm. The results are shown in

Figure 16.

As shown in

Figure 16, under increasing load, the unreinforced foundation undergoes rapid failure, whereas the load–settlement curve of the RCAEC composite foundation shows no distinct steep descending segment. Under the same load level, composite foundations with smaller column spacing (i.e., higher area replacement ratio) exhibit smaller settlements. In addition, the stress sustained by the reinforced composite foundation is significantly greater than that of the unreinforced case, indicating that RCAEC composite foundations effectively improve the bearing capacity of soft soil. Moreover, foundations with smaller column spacing demonstrate superior reinforcement performance under service conditions.

By analyzing the soil stresses at the column top and the center of the composite foundation, the relationship between the column–soil stress ratio and the area replacement ratio is obtained, as illustrated in

Figure 17. The results show that the column–soil stress ratio decreases as the area replacement ratio increases, which aligns with findings from prior model tests. In previous single-column tests conducted by the research group, the ultimate load of a 6d double-layer encased column was about 4 kN, while the ultimate soil load was 1.37 kN. Taking the ratio of these values as the optimal column–soil stress ratio, and aiming to fully mobilize the bearing capacities of both columns and soil while maintaining economic efficiency, it is recommended that the area replacement ratio be designed between 10% and 20% when determining the column spacing for RCAEC composite foundations.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

Murugesan and colleagues conducted a comprehensive parametric study using the finite element method to investigate both qualitative and quantitative improvements in the bearing capacity of geosynthetic-encased stone columns. Similarly, Yoo et al. performed laboratory model tests on stone columns installed in a controlled clay bed within a large test tank, examining the effect of encasement on the qualitative and quantitative bearing behavior of individual columns. Their load tests were carried out on both single and group configurations of stone columns, with and without encasement, using various geosynthetic materials for encapsulation. In the present study, a systematic numerical investigation is carried out to evaluate the bearing characteristics of a composite foundation with geosynthetic-encased recycled concrete aggregate columns. Nevertheless, there remain considerable aspects for improvement in understanding the bearing behavior and developing computational theories for such composite foundations, warranting further in-depth research in subsequent studies.

5.2. Conclusions

This study developed a numerical model to simulate the behavior of RCAEC composite foundations under specific working conditions, with a focus on evaluating the effects of column spacing, encasement stiffness, and encasement length on their bearing characteristics. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) When the ratio of encasement length to column length falls within the range of 20% to 94%, increasing the encasement length significantly enhances the column’s load-bearing capacity. Specifically, once the column-top load exceeds 3 kN, columns with encasement lengths of 5 d, 6 d, and 7 d demonstrate far superior load-bearing performance compared to those with 3 d and 4 d encasement lengths. The maximum bearing capacity increased by 27.8%. Therefore, it is recommended to set the encasement length at 5 to 7 times the column diameter in design.

(2) The enhancing effect of encasement stiffness on bearing capacity becomes evident when column-top loads exceed 3 kN. When stiffness is below 100 kN/m, increasing stiffness effectively boosts both column load-bearing capacity and composite foundation bearing capacity. The results indicate that when the encasement stiffness reaches approximately 100 kN/m, the column’s bearing capacity attains a maximum value of 11.88 kN. Below this threshold, increasing the encasement stiffness effectively enhances both the column capacity and the overall performance of the composite foundation. Beyond 100 kN/m. However, once stiffness surpasses 100 kN/m, further increases yield negligible improvements in bearing capacity. This pattern aligns with single-column test results.

(3) Given that the benefits of encasement stiffness cease to be significant when it exceeds 100 kN/m, a comprehensive assessment of economic viability and effectiveness suggests selecting an encasement stiffness below 100 kN/m for practical engineering designs.

(4) Reducing column spacing can effectively enhance the overall bearing capacity of composite foundations, yielding superior reinforcement effects. However, this strengthening effect is accompanied by a decrease in the column-to-soil stress ratio.

(5) Considering the ultimate load capacity of individual columns, the variation patterns of column–soil stress ratios, and construction cost factors, it is recommended that the optimal design range for the area replacement ratio of composite foundations using concrete construction waste-encased columns be set between 10% and 20%. This ensures the best balance between bearing capacity and project economics.