Abstract

Hydrometallurgical pretreatment of pyrite-bearing concentrates and tailings by hydrothermal interaction with Cu(II) solutions is a promising route for chemical beneficiation and mitigation of acid mine drainage but is limited by passivation caused by elemental sulfur and secondary copper sulfides. Here, the effect of sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) on the hydrothermal reaction between natural pyrite and CuSO4 in H2SO4 media at 180–220 °C was studied at [H2SO4]0 = 10–30 g/dm3, [Cu]0 = 6–24 g/dm3, and [SLS]0 = 0–1.0 g/dm3. Process efficiency was evaluated by Fe extraction into solution and Cu precipitation on the solid phase, and products were characterized by XRD and SEM/EDS. SLS markedly intensified pyrite conversion: at 200 °C and 120 min, Fe extraction increased from 14 to 26% and Cu precipitation from 5 to 23%, while at 220 °C, Fe extraction reached 33.4% and Cu precipitation 26.8%. XRD confirmed the sequential transformation CuS → Cu1.8S. SEM/EDS showed that SLS converts localized nucleation of CuxS on defect sites into the formation of a fine, loosely packed, and well-dispersed copper sulfide phase. The results demonstrate that lignosulfonate surfactants efficiently suppress passivation and enhance mass transfer, providing a basis for intensifying hydrothermal pretreatment of pyrite-bearing industrial materials.

1. Introduction

The global mining industry continues to expand to meet rising metal demand, with copper production growing by 2.2–2.5% annually to exceed 20 Mt in recent years [1]. Pyrometallurgy remains the dominant route for copper concentrates because of high productivity and effective recovery of associated precious metals [2,3], while the greatest economic benefits are typically achieved by vertically integrated operations [4,5]. At the same time, stricter environmental regulations and the need to minimize waste drive modernization of existing plants, including improved gas-cleaning systems and integrated processing of metallurgical by-products (slags, dusts) [6,7,8,9], which increases interest in hydrometallurgical alternatives and prompts a reassessment of tailings management and problematic mineral phases [10]. Flotation is the primary beneficiation method for sulfide ores, particularly chalcopyrite ores [6], but selectivity deteriorates for finely disseminated, complexly intergrown ores [11]. Pyrite in concentrates and tailings is a key challenge, largely due to activation by Cu ions released from secondary copper minerals or added as a sphalerite activator [12,13,14,15], causing pyrite and associated impurities (Zn, Pb, As, etc.) to contaminate concentrates or remain in tailings, thereby reducing product value and increasing environmental risks [10]. In complex systems, sphalerite can act as a “copper sink” and promote pyrite depression under certain conditions [16,17], underscoring the need for approaches that selectively modify or remove the sulfide fraction—primarily pyrite—after enrichment. Tailings, which are finely ground residues after metal extraction [18], exceed 20 billion tons per year globally and occupy > 200,000 km2 [19,20]; their main hazard arises from residual pyrite (FeS2), whose oxidation generates sulfuric acid and AMD, mobilizing heavy metals and contaminating waters and soils. In addition, failures of tailings storage facilities can cause severe, long-term environmental damage, as shown by the Mount Polley and Mariana/Brumadinho accidents [21,22]. Therefore, controlling pyrite behavior in tailings is essential to reduce both acidity generation and toxicity.

Hydrometallurgical technologies applied for chemical beneficiation or purification of concentrates and tailings represent a promising route to address these issues [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. One relevant concept is the hydrothermal interaction of undesirable pyrite (FeS2) with copper ions in aqueous media at elevated temperatures, leading to the formation of secondary copper sulfides (CuS, Cu1.8S, Cu2S) [30,31]. Such a transformation may provide a dual benefit: chemical modification of pyrite-bearing materials and mitigation of AMD potential through depletion or passivation control of reactive sulfides. However, the high chemical stability of pyrite remains a key limitation. Many studies indicate that substantial conversion is typically achieved only at high temperatures, often above 225–240 °C, whereas at temperatures below 200 °C pyrite conversion can be limited under many conditions [32,33,34]. Therefore, intensification strategies that enable more efficient transformation within moderate hydrothermal regimes are of practical and scientific interest.

Process intensification requires a sound mechanistic understanding of pyrite interaction with copper ions in different aqueous media. In acidic sulfate solutions, Kritsky et al. [35] reported a two-stage hydrothermal transformation, where an initial redox-exchange step is followed by a regime increasingly controlled by product-layer formation. A representative pathway can be written as follows:

FeS2 + 1.75Cu2+ + H2O ⟶ 1.75CuS + Fe2+ + 2H+ + 0.25SO42−

They showed that substantial pyrite conversion (up to 50%) is achieved mainly at temperatures above 250 °C, and the kinetics exhibit two stages with activation energies of 61.1 and 37.0 kJ/mol, consistent with internal diffusion control due to the development of a dense multilayer film (Kp-B > 1) composed of successive CuS, Cu1.8S, and Cu2S layers. In chloride media, Zhang et al. [36] proposed a coupled dissolution–precipitation mechanism for natural pyrite crystals, where the product assemblage and zonal structures strongly depend on pH. Key steps include the following:

14FeS2 + 14CuCl2− + 14e− ⟶ 14CuFeS2 + 28Cl−

FeS2 + 8H2O + 2Cl− ⟶ 14H+ + FeCl2(aq) + 2HSO4− + 14e−

Complementary results for sulfate systems were reported by Fuentes et al. [30], who demonstrated that temperature and the nature of the product layer (dense vs. porous) critically determine overall conversion and rate control. Overall, the literature indicates that hydrothermal transformation of pyrite is a multifactorial process governed by solution chemistry, temperature, and evolving product-layer properties; however, transferring these concepts to heterogeneous technogenic materials remains insufficiently resolved [37,38]. Dense reaction products on pyrite may create a diffusion/mass-transfer barrier that slows or even arrests further interaction with reagents [39], motivating the use of surface-active additives to reduce sulfur/product-film adhesion and stabilize dispersions under hydrothermal conditions [40]. At the same time, the specific role and mechanisms of lignosulfonate additives in the pyrite–Cu(II) hydrothermal system in acidic sulfate media remain poorly disclosed in the available literature, leaving an important knowledge gap addressed in this work.

Lignosulfonates (LS) are cost-effective and widely available reagents that have proven effective in mitigating sulfide surface passivation under acidic conditions by acting as sulfur dispersants and interfacial modifiers [41,42]. Their action is commonly attributed to adsorption at the mineral/solution and sulfur/solution interfaces, which decreases sulfur adhesion to mineral surfaces, limits the formation of a blocking sulfur/product layer, and thereby improves reagent access and mass transfer [43]. Owing to their availability and low toxicity, lignosulfonates have also been implemented in industrial practice, including pressure leaching of sulfide concentrates [44,45]. Under hydrothermal conditions, where molten elemental sulfur and secondary sulfides can rapidly form and impose kinetic limitations, lignosulfonate addition has been reported to suppress sulfur encapsulation, enhance process performance, and modify residue morphology via improved sulfur dispersion [46,47,48,49]. Nevertheless, despite these indications, the role of lignosulfonates in the hydrothermal interaction between pyrite and Cu(II) ions in sulfuric acid media—particularly with respect to product phase formation and surface-related phenomena—remains insufficiently systematized.

Accordingly, this study investigates the effect of sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) on the hydrothermal interaction between natural pyrite and Cu(II) ions in H2SO4 media. Batch autoclave experiments were performed at 180–220 °C by varying the initial concentrations of H2SO4, CuSO4, and SLS within the ranges used in this study. Process performance was quantified using Fe extraction into the filtrate and Cu precipitation onto the solid phase, while the reaction products were characterized by XRD and SEM/EDS. The novelty of the present work is a systematic assessment of lignosulfonate action in the pyrite–Cu(II) hydrothermal system, demonstrating suppression of passivation and a transition from localized CuxS nucleation on defect sites to the formation of a finer and better-dispersed copper sulfide phase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis

Chemical analysis of the starting minerals and the resulting solid dissolution products was performed using an ARL Advant’X 4200 wavelength-dispersive spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Phase analysis was carried out on an XRD 7000 Maxima diffractometer (Shimadzu Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Particle size analysis was performed using laser diffraction on an Analysette 22 Nanotec Plus (FRITSCH GmbH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany).

Chemical analysis of the resulting solutions was performed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) on an Elan 9000 instrument (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The ICP-MS solution data were used to calculate Fe extraction and Cu precipitation values, as reported in the Results Section.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a JSM-6390LV microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a module for energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis (EDX). Thermodynamic calculations were performed using HSC Chemistry 9.5 (database) to assess the feasibility and driving force of the proposed overall reactions (within the studied temperature range).

2.2. Materials and Reagents

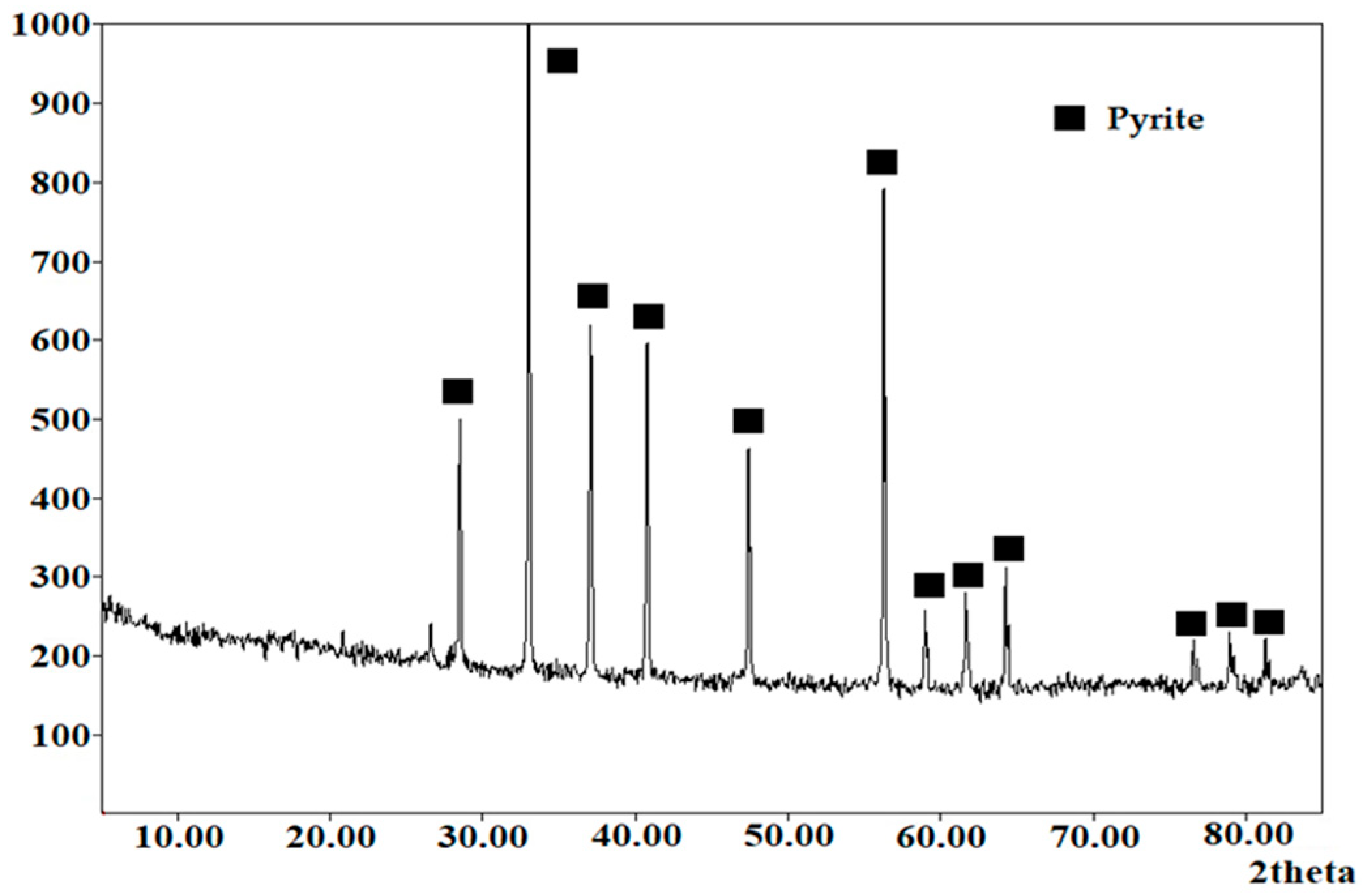

The main raw material used was the natural sulfide mineral pyrite, obtained from the Berezovskoye deposit (Sverdlovsk region, RF). Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of the pyrite used. The clean XRD pattern refers to the detectable crystalline phase composition within the sensitivity of the method. Minor accessory components may be present in trace amounts or in an XRD-amorphous form and therefore may not produce distinguishable diffraction peaks. The mineral was crushed and sieved on laboratory sieves. After sieving, the material was ground to P80 (d80) = 40 μm (80% passing 40 μm). The ground material was homogenized to obtain an averaged powder sample. No chemical purification or pre-treatment was applied prior to XRD measurements. The mechanically prepared natural mineral was analyzed to avoid any alterations in the surface and phase composition.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction pattern of the pyrite used.

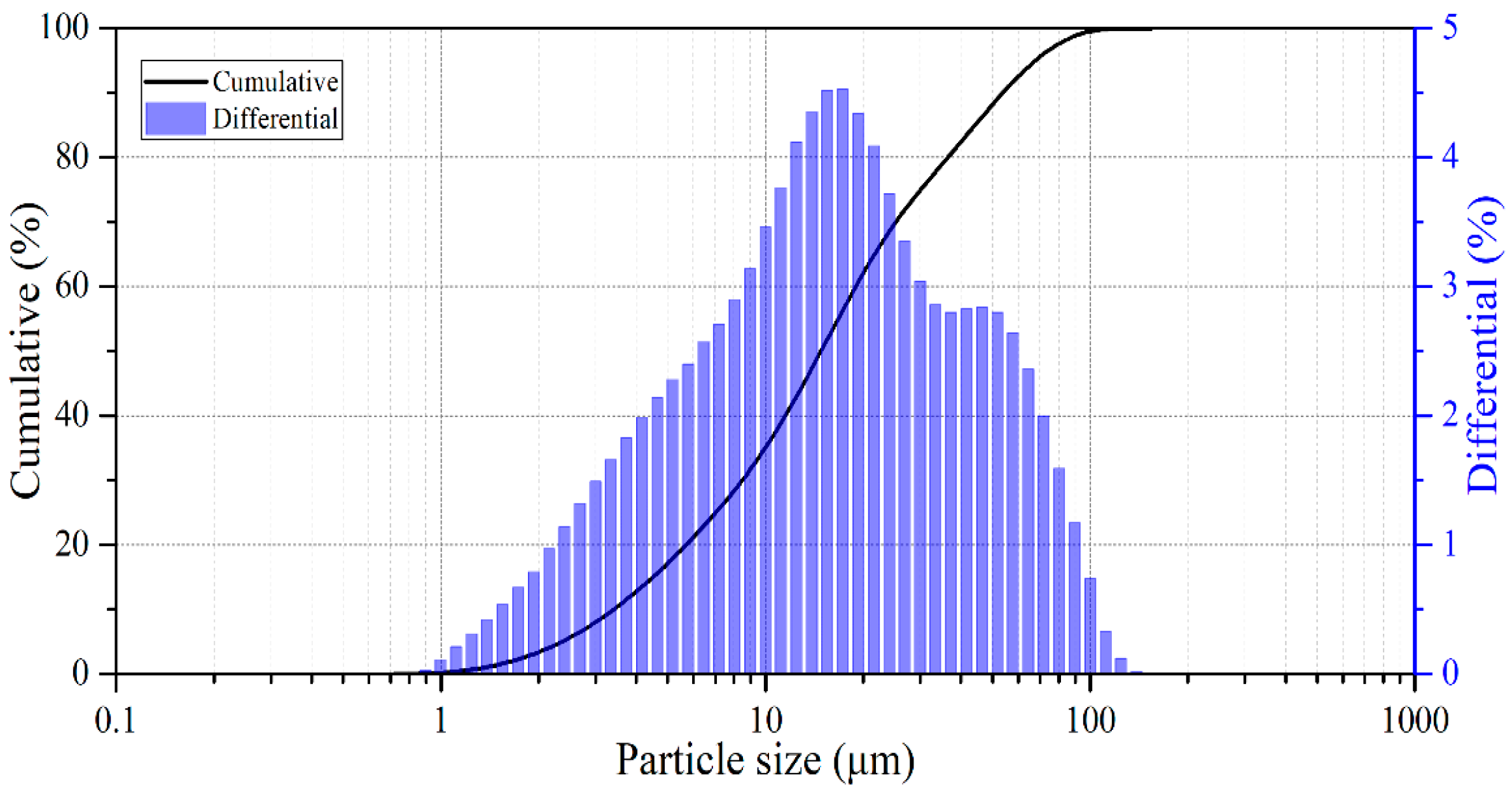

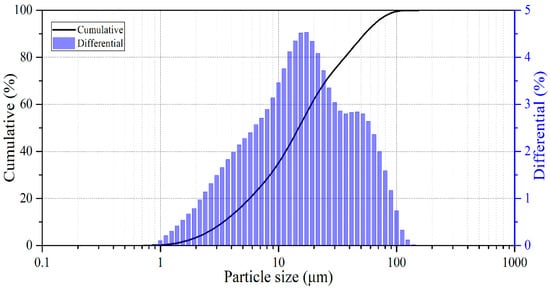

The particle size distribution of the minerals is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Particle size distribution of crushed pyrite.

The percentage contents of the d10, d50, and d90 fractions were 3.41, 14.81, and 53.77 μm, respectively. The chemical composition of pyrite was 44.1 wt.% Fe, 50.8 wt.% S, and 5.1 wt.% others. This composition indicates that the starting material is predominantly FeS2, with a minor amount of accompanying components (others, 5.1 wt.%). The other-material fraction reflects the presence of minor chemical impurities in the natural mineral. However, these components do not necessarily form separate crystalline phases detectable by XRD. Accordingly, Figure 1 indicates pyrite as the dominant crystalline phase, while pronounced reflections of additional crystalline impurities were not observable given the instrument’s sensitivity. All other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.3. Autoclave Hydrothermal Treatment Procedure

Hydrothermal experiments were performed in a 1.0 dm3 titanium autoclave (Parr Instrument, Moline, IL, USA) equipped with an overhead stirrer and temperature control within ±2 °C. For each run, 600 cm3 of an H2SO4–CuSO4 solution was prepared (autoclave filling factor = 0.6) with initial concentrations varying within the following ranges: [H2SO4]0 = 10–30 g/dm3 and [Cu]0 = 6–24 g/dm3. Sodium lignosulfonate was added when required to obtain [SLS]0 = 0–1.0 g/dm3 (0, 0.25, 0.625 and 1.0 g/dm3 were used in this study). A mass of ground pyrite (P80 = 40 μm) of 30 g was added to the solution to obtain a solid-to-liquid (S:L) ratio of 0.05. The reactor was sealed, agitation was set to 800 rpm to ensure slurry homogeneity, and the system was heated to the target temperature (180–220 °C). The temperature range (180–220 °C) was selected to ensure measurable conversion and observable phase transformations within the fixed treatment time, while remaining within the moderate hydrothermal regime relevant to potential process implementation. No external gas atmosphere was imposed, and experiments were performed in a sealed autoclave under autogenous pressure. The reaction time was 120 min and was counted from the moment the set temperature was reached. After the run, the autoclave was cooled to 70 °C, the slurry was filtered, and the residue was thoroughly washed and dried to constant weight. Liquid and solid samples were collected for subsequent chemical and phase or morphological analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

To optimize the autoclave processing, it is necessary to understand the interaction of pyrite with copper sulfate in sulfuric acid solutions. The behavior of FeS2 is known from the literature; however, information on the behavior of this mineral in the presence of surfactants is lacking. Equations (4)–(9) are presented below as net stoichiometric schemes (overall reactions) intended to describe the observed transformation of FeS2 and Cu(II) in sulfate media with the formation of secondary Cu–S phases and elemental sulfur. These equations were derived by balancing Fe, Cu, S, O, and H for the experimentally observed product assemblage and are used for qualitative interpretation rather than as a set of elementary mechanistic steps. The thermodynamic feasibility and direction of these overall reactions under the studied hydrothermal conditions were additionally evaluated using the HSC Chemistry 9.5 database.

The reactions describing the autoclave processing of the pyrite are as follows:

FeS2 + CuSO4 → CuS + FeSO4 + S0

4FeS2 + 7CuSO4 + 4H2O → 7CuS + 4FeSO4 + 4H2SO4

5FeS2 + 14CuSO4 + 12H2O → 7Cu2S + 5FeSO4 + 12H2SO4

FeS2 + 2.61CuSO4 + 2.16H2O → 1.45Cu1.8S + FeSO4 + 2.16 H2SO4

5CuS + 3CuSO4 + 4H2O → 4Cu2S + 4H2SO4

6CuSO4 + 5S0 + 8H2O → 7Cu2S + 8H2SO4

This section is devoted to studying the effectiveness of sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) as a surfactant in the autoclave processing of pyrite. The study aims to establish quantitative relationships between the main process parameters and copper precipitation and pyrite conversion indicators. Hereafter, the process efficiency was quantified using two indicators: Fe extraction into solution and Cu precipitation (removal from solution onto the solid phase). Dissolved Fe and Cu concentrations were measured by ICP-MS (Elan 9000, PerkinElmer), and Fe extraction (%) and Cu precipitation (%) were calculated from mass balance using the measured solution concentrations before and after the run.

Iron extraction was calculated from the dissolved iron concentration measured in the filtrate (ICP-MS) as follows:

where mFe,sol = CFe,sol × V is the mass of Fe in the solution after treatment, CFe,sol (g/dm3) is the measured Fe concentration, and V (dm3) is the solution volume. The initial iron content mFe,0 was determined from the mass of the loaded pyrite and its elemental composition (Section 2.2).

EFe = (mFe,sol/mFe,0) × 100%,

Copper precipitation was calculated from copper removal from solution as follows:

where mCu,0 = CCu,0 × V is the initial mass of Cu(II) in the leach solution, and mCu,sol = CCu,sol × V is the mass of dissolved Cu after treatment (ICP-MS).

PCu = [(mCu,0 − mCu,sol)/mCu,0] × 100%,

The phase composition of solid products was determined by XRD (XRD 7000 Maxima), while morphology and elemental distribution were evaluated by SEM/EDX (JSM-6390LV). The corresponding instrumentation is described in Section 2.1. In particular, the kinetics of pyrite dissolution with the release of iron ions into the solution are examined in detail.

The experiments were conducted under high hydrothermal conditions (180–220 °C). It should be emphasized that the presented results are unique: the influence of SLS on phase transformations during the interaction of copper sulfate solutions with pyrite at the specified temperature range has not previously been described in the literature.

The influence of key process parameters on the degree of the interaction of pyrite with copper (II) ions under hydrothermal conditions was studied. The variable factors included process temperature (180–220 °C), the initial concentration of sulfuric acid (10–30 g/dm3), copper (II) (6–24 g/dm3), and SLS (0.25–1.00 g/dm3).

The efficiency of pyrite conversion was assessed based on the degree of iron transfer into solution and the amount of copper precipitation on the solid phase surface. This approach allowed for a comprehensive characterization of both FeS2 dissolution and the accompanying redox-exchange processes between pyrite and Cu(II), which is particularly important when analyzing the behavior of minerals in complex sulfate systems.

Unless stated otherwise, plotted data represent the average of three independent runs, and the error bars indicate 5% SD, which was in the data we received.

3.1. Effect of Sodium Lignosulfonate

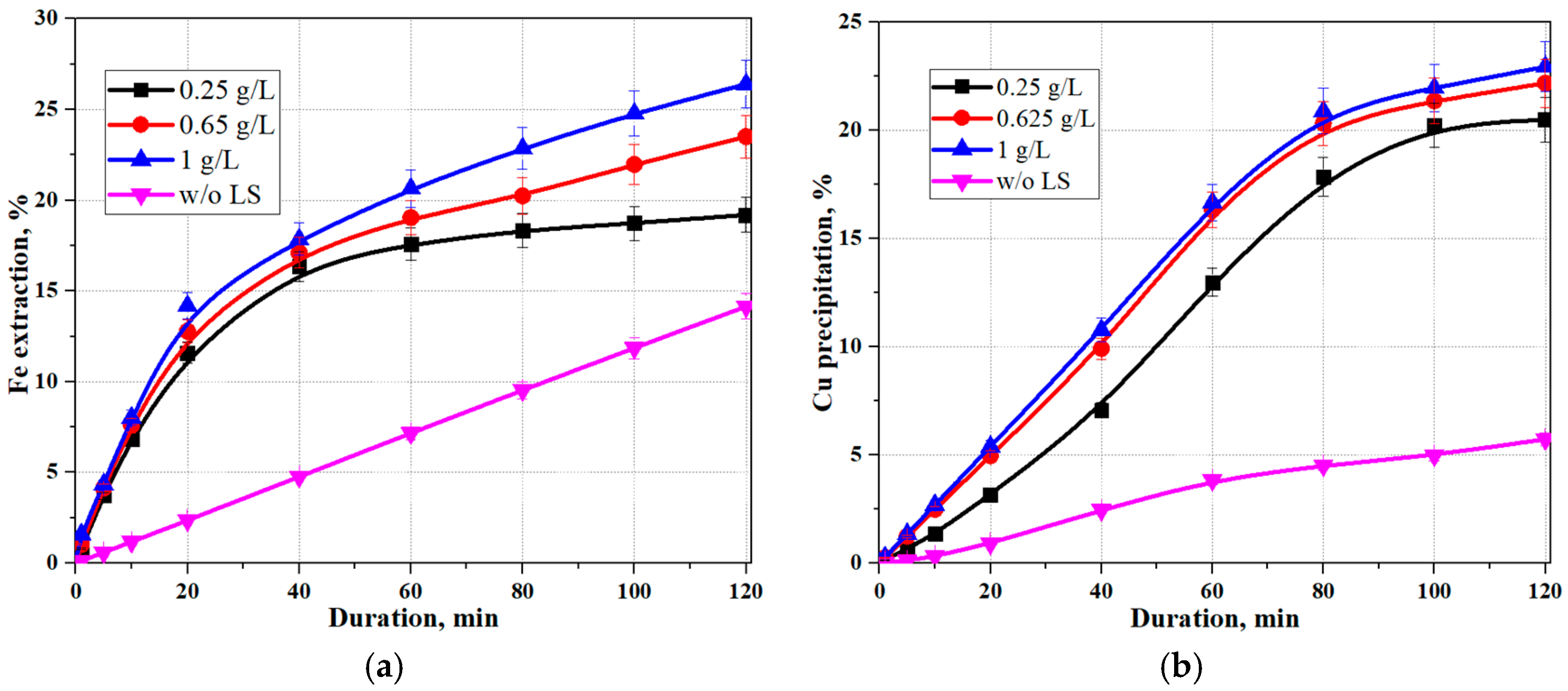

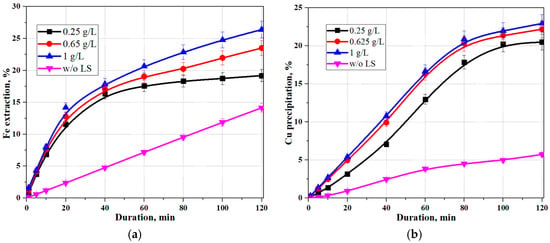

Figure 3 shows the effect of SLS concentration on the degree of iron extraction and the degree of copper precipitation during hydrothermal treatment of pyrite.

Figure 3.

Effect of initial lignosulfonate concentration during hydrothermal pyrite treatment: (a) extraction iron; (b) copper precipitation (t = 200 °C, [H2SO4]0 = 20 g/dm3, [Cu]0 = 15 g/dm3).

The graph shows a significant effect of sodium lignosulfonate addition on iron extraction from pyrite and copper precipitation onto pyrite. As with sphalerite, the addition of sodium lignosulfonate significantly intensifies the hydrothermal treatment of pyrite. Increasing the initial lignosulfonate concentration moderately increases iron extraction. After 120 min of hydrothermal treatment with 0.25 g/dm3 and 1 g/dm3 lignosulfonate, iron extraction was 19% and 26%, respectively, compared to 14% without sodium lignosulfonate. Copper precipitation also increases with increasing initial sodium lignosulfonate concentration, namely, after 120 min without sodium lignosulfonate, with 0.25 g/dm3 and 1 g/dm3, copper precipitation was 5%, 20%, and 23%, respectively. For the following calculations, an initial SLS concentration of 1 g/dm3 was adopted.

Analysis of the experimental data (Figure 3) showed that sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) had a significant impact on iron extraction and the concomitant copper deposition on the pyrite surface. SLS introduction significantly intensified the hydrothermal interaction of pyrite with copper (II) ions.

With increasing initial SLS concentration, an increase in the degree of iron release into solution was observed. After 120 min of hydrothermal treatment at SLS concentrations of 0.25 and 1.0 g/dm3, iron extraction was 19% and 26%, respectively, while it did not exceed 14% in the control experiment without surfactants. A similar trend was observed for the copper precipitation process, namely, the degree of Cu(II) precipitation increased from 5% (without SLS) up to 20% at an SLS concentration of 0.25 g/dm3 and up to 23% at 1.0 g/dm3 over 120 min.

Given the significant increase in the system’s reactivity and the most pronounced effect at 1.0 g/dm3, an initial SLS concentration of 1 g/dm3 was adopted for further experiments and modeling.

3.2. Effect of Temperature

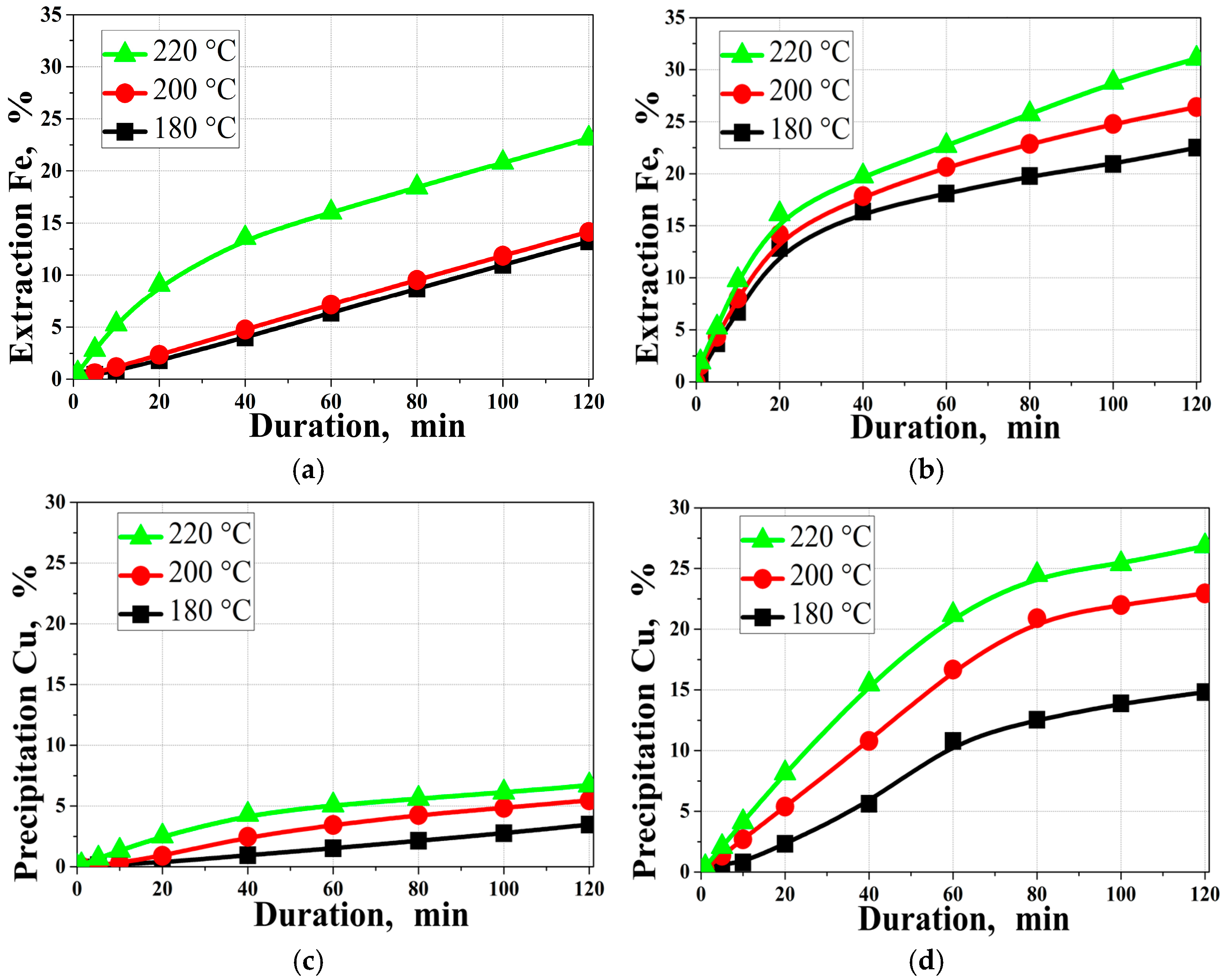

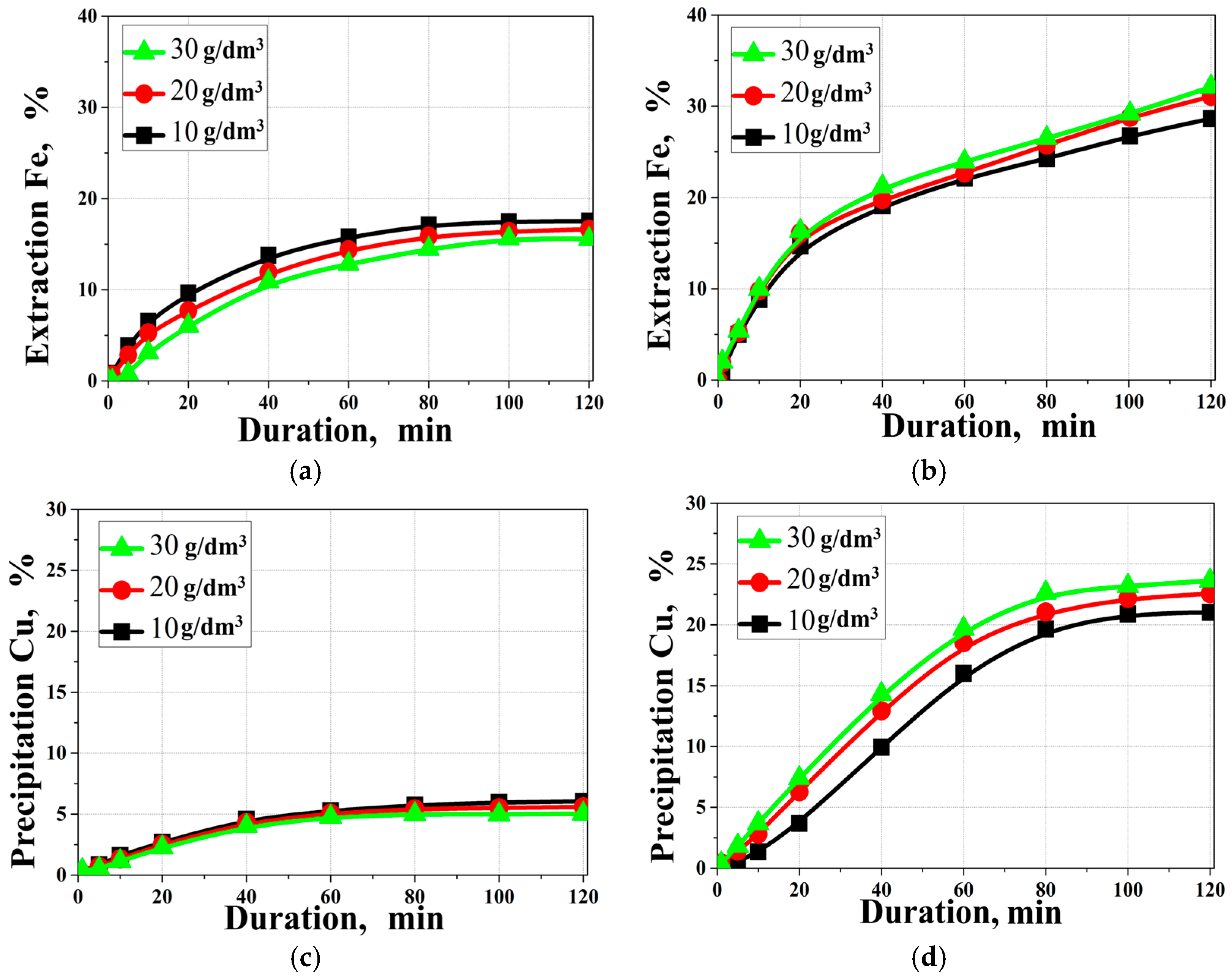

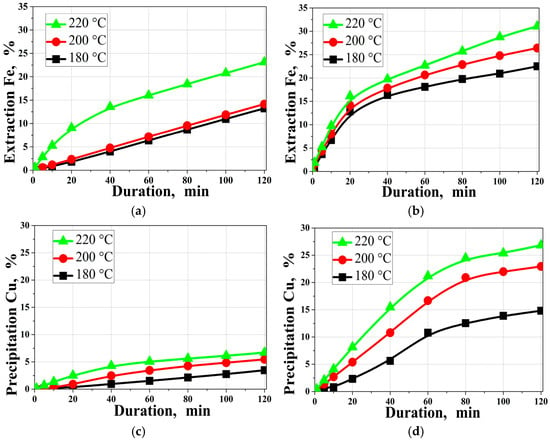

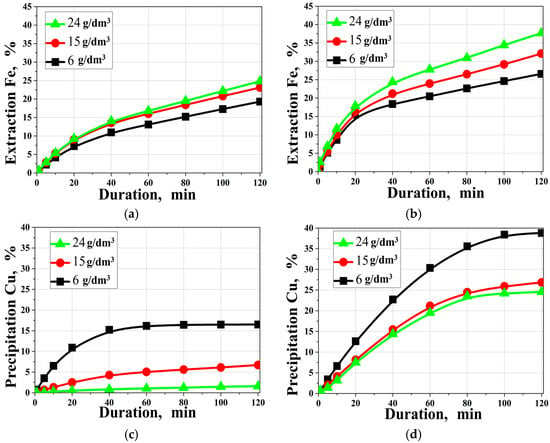

Figure 4 shows the effect of temperature on the degree of iron extraction and copper precipitation.

Figure 4.

Effect of temperature on the degree of (a,b) iron extraction; (c,d) copper precipitation; (a,c) in the absence of SLS; (b,d) in the presence of SLS. ([H2SO4]0 = 20 g/dm3, [Cu]0 = 15 g/dm3, [SLS]0 = 1 g/dm3).

Here and further, panels (a,c) correspond to experiments without SLS, whereas panels (b,d) correspond to experiments with SLS. Therefore, the different trends between the left and right panels reflect the change in the surface-controlled regime due to SLS, which mitigates passivation by S0 and secondary Cu–S phases and improves reagent access to the pyrite surface. As can be seen from the data presented in Figure 4, increasing temperature has a pronounced positive effect on iron extraction into solution and the degree of copper precipitation on the solid phase surface. In the presence of sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) at 220 °C, 33.4% of the iron is released into solution within 120 min, compared to only 23.1% in the absence of SLS. Thus, the addition of SLS intensifies the sulfide matrix destruction and iron release into solution.

A similar pattern is observed for copper. The presence of SLS significantly increases its precipitation rate. At temperatures of 180, 200, and 220 °C with no addition of SLS, the copper precipitation rate is 3.5, 5.5, and 6.7%, respectively, after 120 min of treatment. The addition of SLS leads to a sharp increase in this rate—up to 14.8, 22.9, and 26.8%, respectively, at the same temperatures. This behavior indicates the nature of the influence of SLS, likely related to modification of the surface properties of mineral particles and accelerated reagent transfer.

The upper bound of 220 °C was chosen because it provided the highest Fe extraction and Cu precipitation rates within 120 min and maximized the contrast between experiments with and without SLS, enabling more reliable comparison of parameter effects and product-phase evolution.

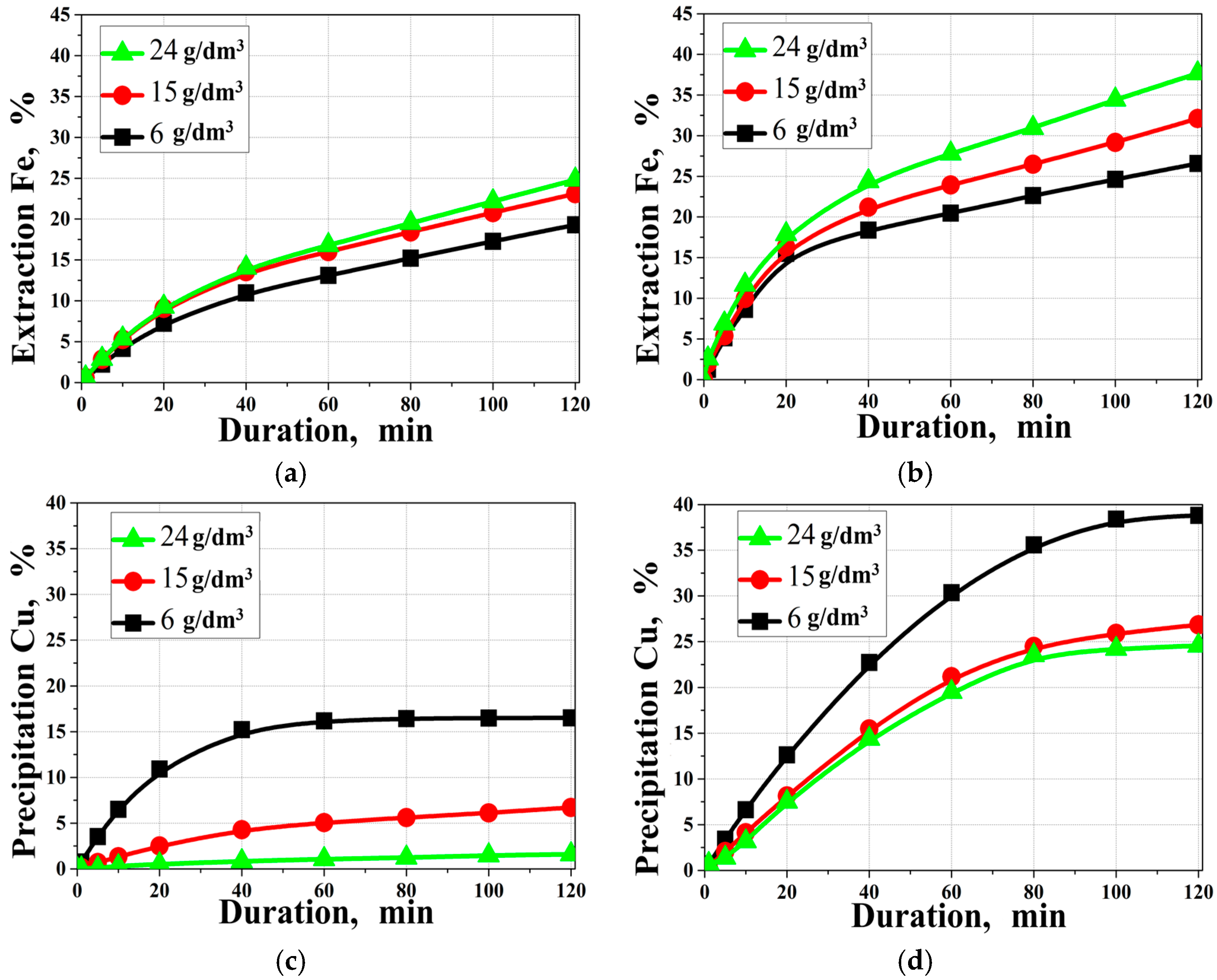

3.3. Effect of Initial Sulfuric Acid Concentration in Solution

In this work, the acidity of the hydrothermal sulfate system was controlled and reported via the initial sulfuric acid concentration, [H2SO4]0 (10–30 g/dm3), rather than pH. At 220 °C, the formal pH of aqueous solutions and dissociation equilibria differ markedly from those at ambient conditions; therefore, specifying [H2SO4]0 provides more robust reproducibility. For reference, the initial pH values can be reported for the starting solutions at 25 °C (prior to heating) if required.

Sulfuric acid was selected deliberately to maintain a sulfate medium consistent with the FeS2–Cu(II) redox-exchange chemistry discussed in reactions (4–9). The use of other acids (especially chloride-containing media) would alter Cu(II) complexation and potentially change the transformation pathways, complicating mechanistic interpretation. Buffer systems were not applied because most buffering couples are not chemically stable and/or do not maintain a well-defined buffering capacity at 220 °C, while also introducing additional ions that can interfere with the sulfate system. Figure 5 shows the effect of the initial sulfuric acid concentration on the degree of iron extraction and copper precipitation.

Figure 5.

Effect of the initial sulfuric acid concentration on (a,b) iron extraction; (c,d) copper precipitation; (a,c) in the absence of SLS; (b,d) in the presence of SLS. (t = 220 °C, [Cu]0 = 15 g/dm3; [SLS]0 = 1 g/dm3).

According to the data presented in Figure 5, the change in the degree of iron extraction from pyrite and copper precipitation indicates that SLS exhibits pronounced dispersing and adsorption properties, which help reduce the passivating effect of elemental sulfur, covellite, and digenite on the surface of mineral particles and, consequently, increase the availability of active sites for reactions.

In the absence of SLS, increasing the initial sulfuric acid concentration leads to a decrease in iron extraction and copper precipitation, which is consistent with the concept of enhanced surface passivation at elevated acidity. Conversely, in the presence of SLS, increasing the acid concentration from 10 up to 30 g/dm3 is accompanied by a small but steady increase in the degree of conversion. For example, after 120 min of hydrothermal treatment of pyrite at 10, 20, and 30 g/dm3 sulfuric acid, 31.3, 33.4, and 33.9% Fe are extracted, respectively, while copper precipitation reaches 21, 22.5, and 23.6%, respectively. The observed trends are consistent with the formation of surface-passivating products in the sulfate hydrothermal system, including secondary copper sulfides and elemental sulfur. The solid-phase products are discussed in Section 3.5 and are supported by XRD, which indicates the formation of Cu1.8S as well as by SEM–EDX mapping, demonstrating Cu/S enrichment on the particle surfaces.

These data demonstrate that the use of SLS not only compensates for the negative effect of increased acidity but also ensures more stable oxidation and precipitation reactions. Based on the maximum achieved iron recovery and copper precipitation values, an initial sulfuric acid concentration of 30 g/dm3 was adopted for subsequent experiments.

3.4. Effect of Initial Copper Concentration

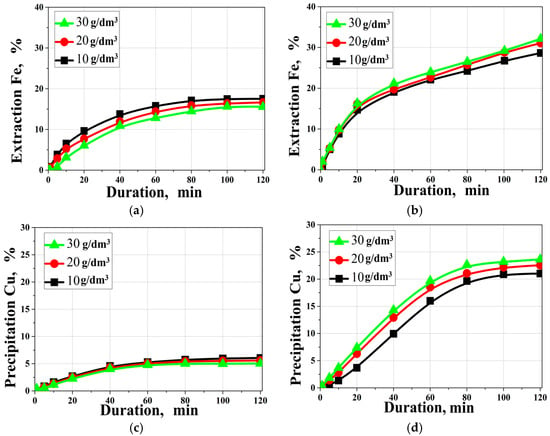

Figure 6 shows the effect of the initial copper concentration on iron recovery and copper precipitation.

Figure 6.

Effect of the initial copper concentration on (a,b) iron extraction; (c,d) copper precipitation; (a,c) in the absence of SLS; (b,d) in the presence of SLS ([H2SO4]0 = 30 g/dm3; t = 220 °C; [SLS]0 = 1 g/dm3).

According to Figure 6, increasing the initial copper (II) ion concentration leads to an increase in iron recovery in both the absence and presence of SLS. However, the magnitude of the effect is significantly greater in systems with SLS. For example, at a copper (II) ion concentration of 24 g/dm3, 41.2% of Fe is recovered after 120 min of hydrothermal treatment, compared to only 25% in the system without surfactants. This indicates an increased role for copper as an oxidizer and that SLS facilitates reagent access to the pyrite surface, reducing the effect of passivating films.

Mechanistically, increasing [Cu]0 enhances the redox-exchange interaction because Cu(II) serves as the main oxidant/electron acceptor at the pyrite surface. The surface reaction can be viewed as coupled anodic dissolution of FeS2 (release of Fe2+ and sulfur species) and cathodic reduction in Cu(II) to Cu(I) in localized electrochemical microzones. The generated Cu(I) is unstable in the sulfate hydrothermal system and is consumed via nucleation and growth of secondary Cu–S phases on the pyrite surface. Consistent with the phase analysis (Section 3.5), the secondary layer evolves sequentially (CuS → Cu1.8S), and its growth progressively introduces a diffusion/mass-transfer barrier for reagent access and product removal. This framework explains why Fe extraction increases with [Cu]0 (higher oxidizing capacity and faster interfacial electron transfer), whereas the “Cu precipitation, %” may decrease at higher [Cu]0: under Cu(II) excess, the extent of Cu removal becomes limited by the availability of reactive sulfur/surface sites and by transport through the growing Cu–S/S0 product layer, so the fraction of Cu removed from solution declines even though the absolute amount of precipitated copper can increase.

In the presence of SLS, the above limitations are mitigated because SLS reduces adhesion/encapsulation by S0 and Cu–S products and improves dispersion, thereby maintaining a larger population of active precipitation sites over the course of the run.

Interestingly, copper’s behavior in solution exhibits a different trend, namely, at an initial concentration of 6 g/dm3, its precipitation rate is 38.8%, while at 24 g/dm3, it decreases down to 24%. Despite this, both values significantly exceed those of similar systems without SLS (16.5 and 6%, respectively). This discrepancy emphasizes that SLS promotes the formation of active copper precipitation sites even at high copper (II) ion concentrations in solution. Notably, this trend refers to the fraction of Cu removed from solution, as at higher [Cu]0, the absolute amount of precipitated Cu can still increase, while the removal percentage decreases.

Taken together, the data obtained confirm the pronounced positive effect of SLS on the interaction of pyrite with copper ions under hydrothermal conditions, manifesting both in enhanced iron dissolution and in increased copper precipitation efficiency.

3.5. Characteristics of the Resulting Precipitates

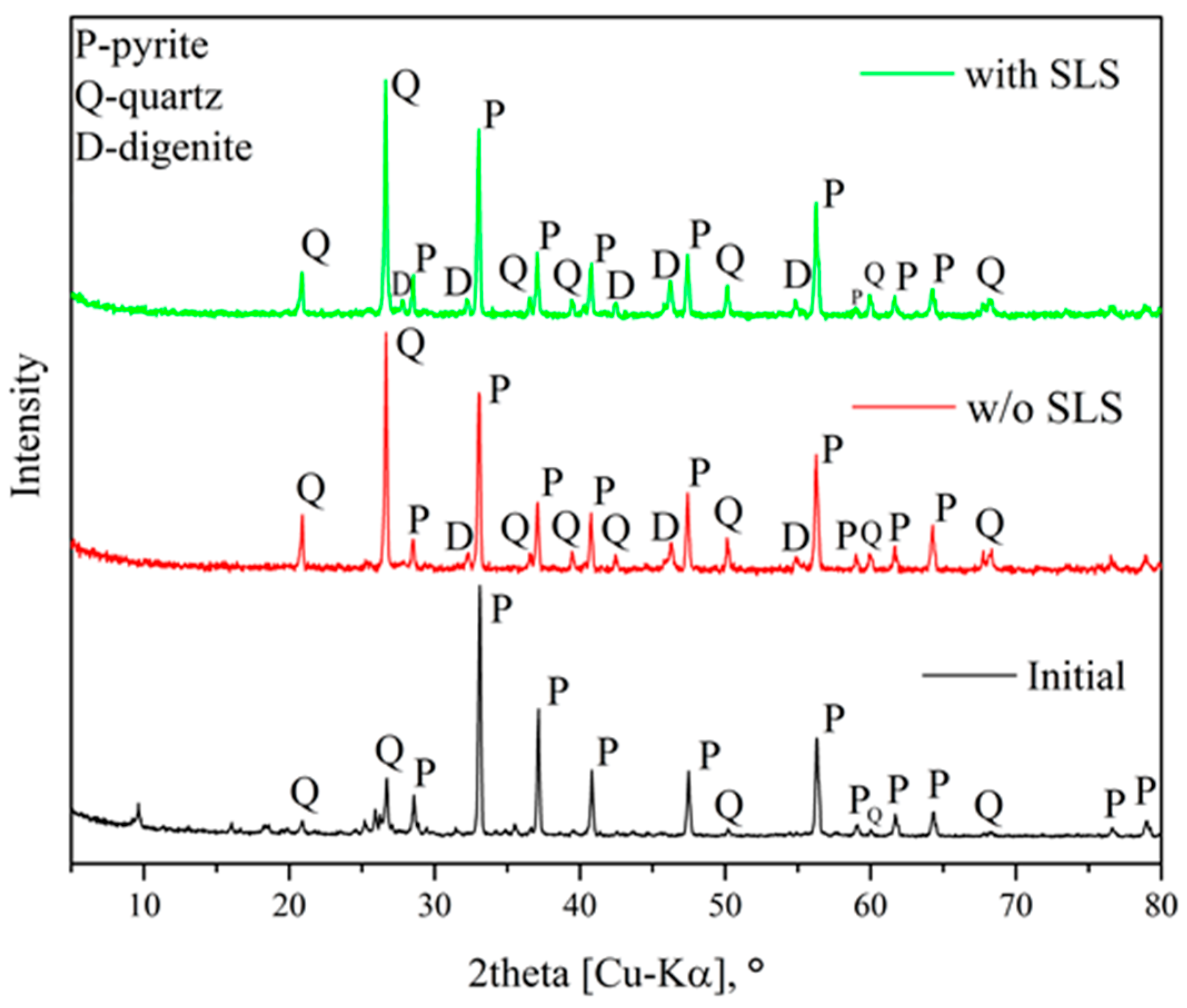

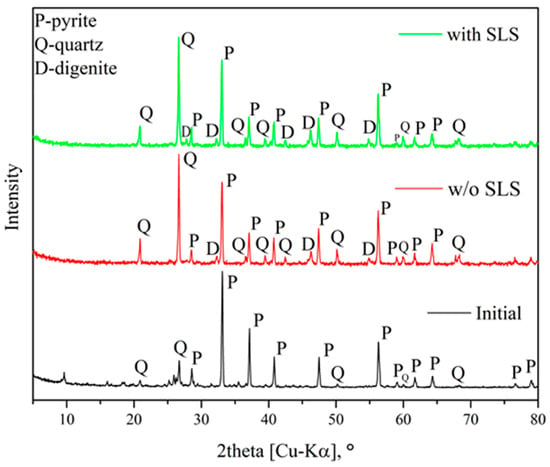

Figure 7 shows X-ray diffraction patterns of the solid products obtained after the hydrothermal treatment of pyrite.

Figure 7.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the solid products obtained after the hydrothermal treatment of pyrite.

According to the X-ray diffraction data, secondary copper sulfide digenite (Cu1.8S) is formed during the hydrothermal reaction of pyrite, which is consistent with previously published results [32,35,50,51,52,53]. In the early stages of transformation or at low temperatures, the presence of CuS could be detected in the solid product, whereas at elevated temperatures or longer reaction times, the formation of the Cu1.8S phase is observed.

Temperature has a significant effect on the degree of pyrite transformation and the reaction mechanism. No formation of Fe2O3, metallic copper, or other secondary phases is observed. The phase composition of the solid residue indicates that the pyrite transformation process proceeds predominantly according to Equations (4)–(7). Similarly to the results of [51], the presence of Cu1.8S is confirmed.

Based on these data, it can be concluded that pyrite transformation in copper sulfate solution occurs sequentially through the formation of the phases CuS → Cu1.8S → Cu1.94S → Cu2S [35]. This sequence reflects the gradual enrichment of the sulfide layer with copper, which is consistent with the thermodynamically determined direction of the interaction processes between FeS2 and Cu(II).

During hydrothermal treatment of pyrite in a CuSO4 solution, the resulting layer of copper sulfides (CuS–Cu1.8S) may shield the pyrite surface and reduce the rate of reaction due to a diffusion barrier associated with reagent access to the surface and impeding the removal of transformation products. The rate of diffusion through this product layer is determined primarily by its thickness, density, and porosity.

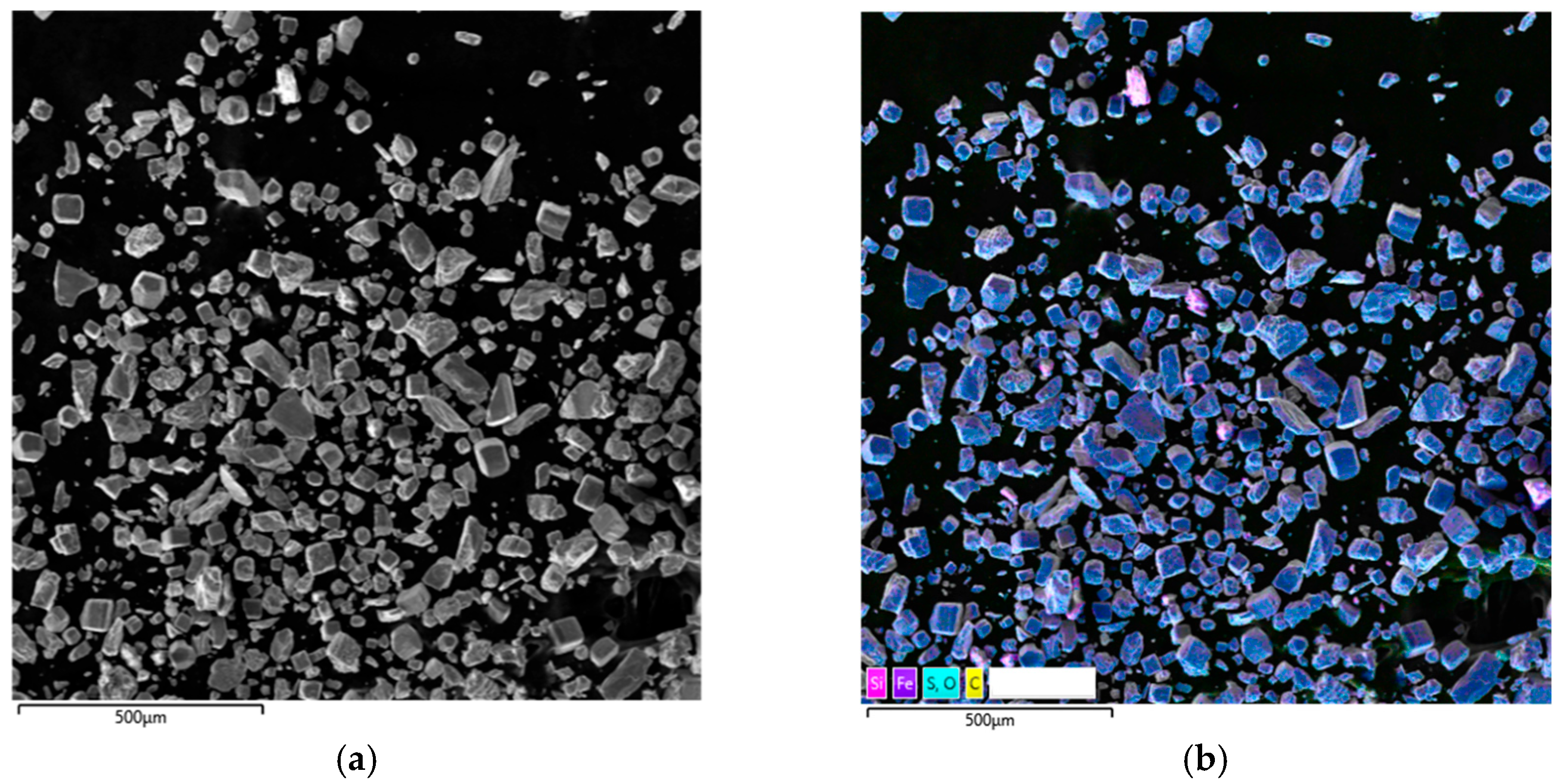

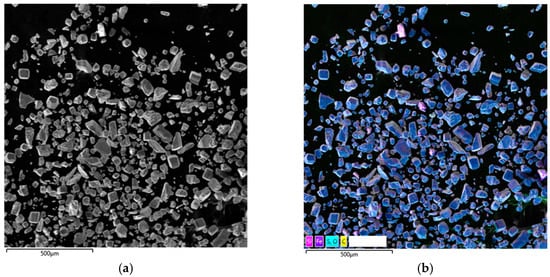

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to characterize the resulting precipitates. The interpretation of Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 is based on a combined dataset: ICP-MS results for Fe extraction and Cu removal from solution; XRD phase identification (Figure 7) evidencing secondary Cu–S phases (CuS/Cu1.8S) formed during pyrite transformation, and SEM–EDX morphology and elemental mapping revealing where and how these phases nucleate and distribute on/around pyrite particles. In addition, bulk data for selected residues are provided (Table 1 and Table 2) to confirm Cu accumulation in the solid phase and to support the mass-balance interpretation.

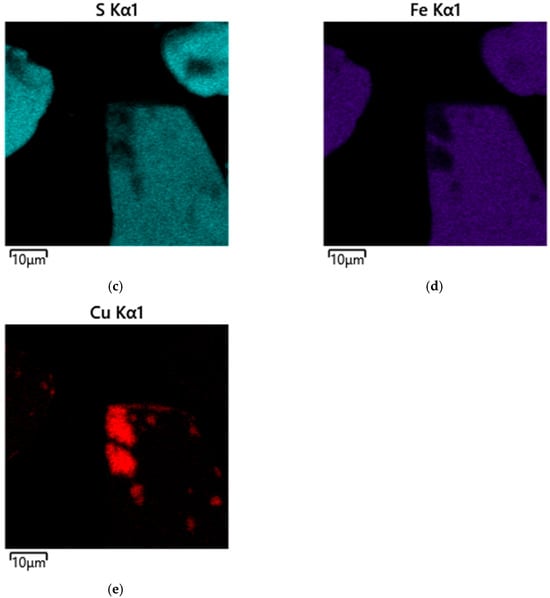

Figure 8.

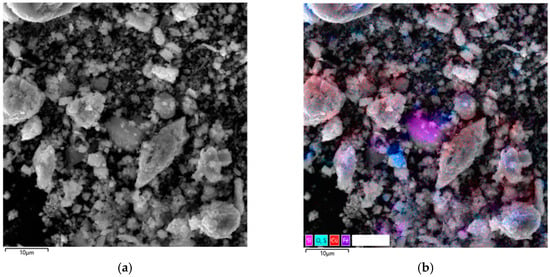

Micrograph and EDS mapping of pyrite cake without SLS (500 µm): (a) electron image, (b) multilayer EDS image, (c) EDS for sulfur, (d) EDS for iron, (e) EDS for copper.

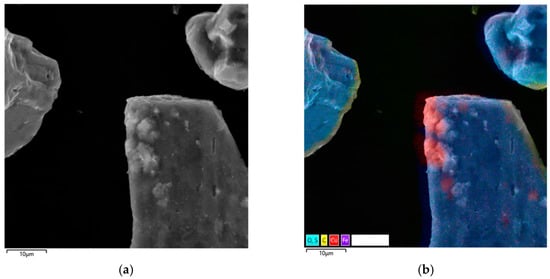

Figure 9.

Micrograph and EDS mapping of the pyrite cake without SLS (10 μm): (a) electron image, (b) multilayer EDS image, (c) EDS for sulfur, (d) EDS for iron, (e) EDS for copper.

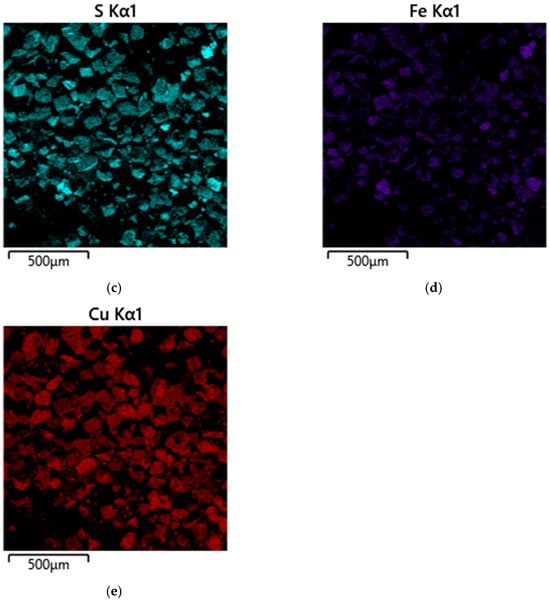

Figure 10.

Micrograph and EDS mapping of a pyrite gas-extracted solid waste cake sample in the presence of SLS, 500 µm: (a) electron image, (b) multilayer EDS image, (c) EDS for sulfur, (d) EDS for iron, (e) EDS for copper.

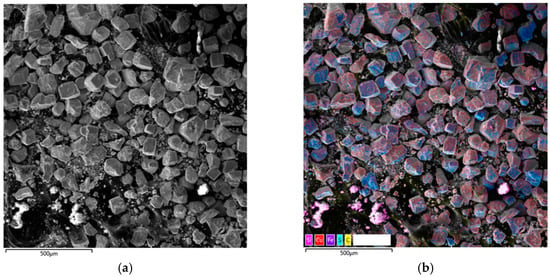

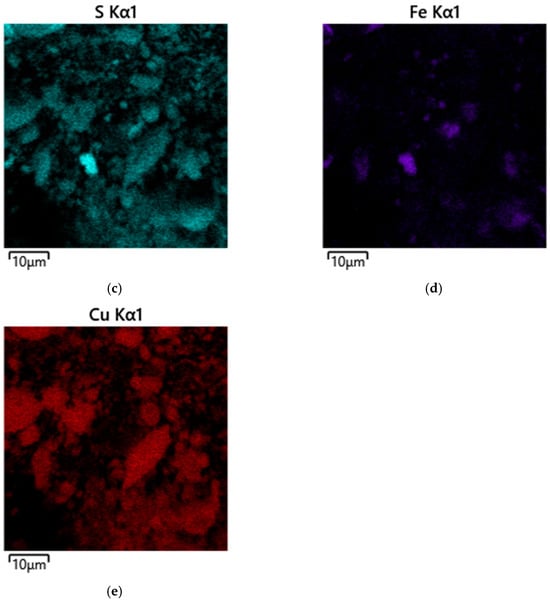

Figure 11.

Micrographs and EDS mapping of a pyrite cake sample from a gas-extracted wastewater treatment plant in the presence of SLS, 10 µm: (a) electron image, (b) multilayer EDS image, (c) EDS for sulfur, (d) EDS for iron, (e) EDS for copper.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the selected residue without SLS.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the selected residue with SLS.

The results of analysis of the resulting precipitates from the hydrothermal treatment of pyrite with copper sulfate in the absence and presence of SLS at [H2SO4]0 = 30 g/dm3; t = 220 °C; [SLS]0 = 1 g/dm3, and [Cu]0 = 15 g/dm3 are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8a shows cake particles for which the EDS map visualizes the distribution zones of the main elements: turquoise areas correspond to sulfur (Figure 8c), violet areas to iron (Figure 8d), and red areas to copper (Figure 8e). The overlap of turquoise and violet zones indicates the presence of pyrite, which is consistent with the morphology of the particles identified in Figure 8b.

The amount of copper deposited on pyrite is insignificant; its distribution is localized. Copper is observed primarily as individual small inclusions, irregularly dispersed across the surface of mineral particles. This is a typical feature of autoclave systems, where copper (II) ions are reduced to copper (I) and then precipitate as secondary sulfides on active surface areas.

When the image is zoomed in to 10 µm (Figure 9), it becomes apparent that the surface of most pyrite grains remains relatively smooth.

However, pronounced irregularities and microdepressions are observed in a number of localized areas. These morphological defects are due to the formation of the secondary copper phase of digenite (Cu1.8S). This is consistent with phase analysis data and general understanding of the mechanism of copper deposition on pyrite during hydrothermal oxidation.

This surface heterogeneity indicates that copper deposition is a point-like nucleation process controlled by localized electrochemical microzones and heterogeneities in the pyrite surface [54,55,56,57,58,59,60].

Analysis of the microstructure shown in Figure 9 suggests that secondary copper sulfides form predominantly in localized defect zones of the pyrite surface and are virtually nonexistent on smooth, low-activity areas of the particles. This spatial selectivity is characteristic of nucleation processes, where structural inhomogeneities, cracks, micropores, and areas with a disrupted crystal lattice act as nucleation centers.

The total copper particle content in the analyzed region does not exceed 4%, confirming the limited nature of copper precipitation under these conditions. According to EDX mapping data (Figure 9b), the region where copper is localized (Figure 9e) is characterized by reduced sulfur content and a virtually complete absence of iron (Figure 9d). This combination is characteristic of secondary copper sulfides and possibly indicates the formation of compounds such as CuS, formed through the reduction of copper (II) ions and subsequent interaction with sulfur migrating within the surface layers of the mineral.

Thus, the morphology and distribution of elements in localized areas confirm that copper precipitates predominantly as secondary sulfides on pyrite surface defects, which act as active nucleation centers.

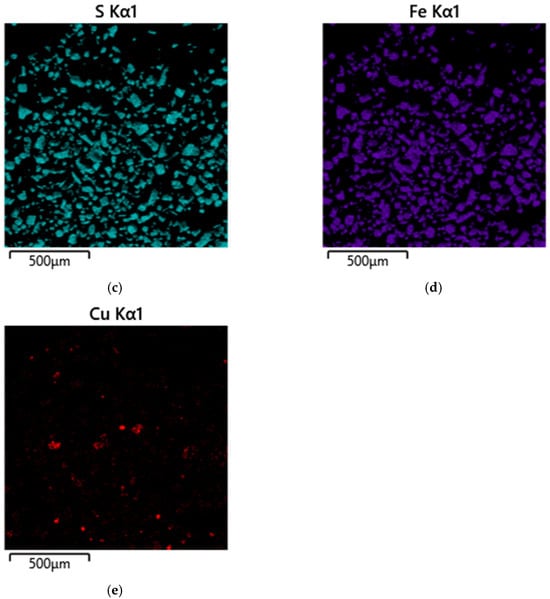

Micrographs and EDS mapping of a pyrite gas-extracted solid waste cake sample in the presence of SLS are shown in Figure 10.

According to the data presented in Figure 10, the addition of SLS leads to a significant change in the morphology of the solid products. The micrographs clearly show the appearance of a large number of small particles, which, as follows from the EDS mapping results, are most likely secondary copper sulfides. Their significant formation indicates that the presence of SLS promotes more intense interaction of copper (II) ions with pyrite on the surface, leading to its reduction and the subsequent nucleation of secondary copper sulfides (CuS and Cu1.8S) in the bulk of the suspension.

Furthermore, according to Figure 10e, the copper distribution on the pyrite surface becomes noticeably more uniform. Unlike the surfactant-free system, where copper precipitates as isolated point inclusions, individual inclusions are virtually nonexistent in the presence of SLS. This indicates a change in the precipitation mechanism. SLS likely prevents localized surface passivation by secondary copper sulfides and elemental sulfur, facilitating a more uniform transfer of copper ions to the pyrite surface, their interaction, and precipitation.

It can be noted that the iron signal intensity in the EDX maps significantly decreases, which may indicate partial shielding of the pyrite surface by secondary copper phases.

Micrographs of fine cake particles obtained in the presence of SLS are shown in Figure 11.

These particles have a significantly more developed and morphologically heterogeneous surface compared to the products formed in the system with no surfactants. This confirms the influence of SLS on the formation of secondary phases and the overall morphology of minerals during hydrothermal treatment.

As can be seen from the presented images (Figure 11), fine particles are formed primarily as a result of the interaction of copper ions with elemental sulfur, fine pyrite particles, and the subsequent separation of the formed copper sulfides. In the presence of SLS, the dispersion processes of sulfur and secondary phases are significantly enhanced, leading to the formation of a developed fine fraction. Almost all of the “fine” material is represented by secondary copper sulfides, which is clearly confirmed by the EDS maps (Figure 11d,e), which record the characteristic distribution of copper with a simultaneous almost complete absence of iron signals.

Nevertheless, fragments of unreacted pyrite are also found among the fine particles (Figure 11c,d). There are no signs of secondary copper phase precipitation on their surface. This suggests that previously formed copper sulfides may have separated from the pyrite surface during hydrothermal treatment. This effect is consistent with the observed morphology—smooth pyrite areas and the absence of copper inclusions indicate mechanical separation with the combined action of surfactants. The latter, due to its absorption and dispersive properties, concentrates on the pyrite surface, creating cracks and breaking large particles into small ones, while in smaller particles, it forms irregularities and roughness, facilitating the separation of newly formed copper sulfides from the surface.

3.6. Mechanistic Interpretation

In the sulfate hydrothermal system, pyrite interacts with Cu(II) predominantly via a redox-exchange pathway accompanied by formation of secondary copper sulfides and elemental sulfur, as summarized by Equations (4)–(9). At the initial stage, Cu(II) is reduced at reactive sites of the pyrite surface and Cu–S nuclei form (CuS can be detected at early stages or less severe conditions), while Fe is released into solution as FeSO4 and sulfur is partially converted to S0 (Equation (4)). As the reaction proceeds, the surface product evolves toward Cu-rich sulfides, and XRD demonstrates a dominance of digenite Cu1.8S at higher temperatures and longer times, consistent with the sequential transformation CuS → Cu1.8S (and as further Cu enrichment occurs, as reported in the literature) and in the overall direction of Equations (4)–(7). The growing CuS–Cu1.8S layer progressively becomes a mass-transfer barrier, limiting reagent access and removal of transformation products, which explains the tendency toward diffusion control at advanced conversion.

The role of SLS is interpreted as mitigation of local passivation by S0 and Cu–S products and stabilization of dispersion under hydrothermal conditions. Without SLS, SEM–EDX shows that copper is deposited mainly as isolated, localized inclusions on surface defects, whereas most pyrite areas remain relatively smooth, indicating point-like nucleation in electrochemically active microzones. In the presence of SLS, SEM–EDX reveals numerous fine Cu-bearing particles and a markedly more uniform Cu distribution, consistent with suppressed adhesion/encapsulation by passivating products and a larger number of active precipitation sites sustained over time.

Overall, the obtained microstructural data confirm that SLS significantly alters the mechanism of interaction between pyrite and copper and sulfur ions, promoting the formation of a finer phase of secondary copper sulfides and simultaneously influencing the distribution of copper among the mineral components of the solid product.

4. Conclusions

Sodium lignosulfonate (SLS) was shown to markedly influence the hydrothermal interaction between natural pyrite and Cu(II) in sulfate media by mitigating surface passivation and promoting a more uniform deposition/dispersion of transformation products. Under the studied conditions (180–220 °C, [H2SO4]0 = 10–30 g/dm3, [Cu]0 = 6–24 g/dm3, t = 120 min), the most pronounced contrast between the systems with and without SLS was observed at 220 °C, where the process intensity and the sensitivity to additives were maximal. Phase analysis confirmed that pyrite transformation proceeds with the formation of secondary copper sulfides, with CuS detected at early conditions and Cu1.8S dominating at higher temperatures and longer treatments. The combined ICP-MS, XRD, and SEM–EDX results consistently indicate that SLS reduces the formation of a blocking product layer and maintains a larger population of reactive sites, which improves the efficiency metrics (Fe extraction and Cu precipitation) under hydrothermal conditions. These findings support the practical use of lignosulfonate-type additives for controlling passivation and mass-transfer limitations in sulfate hydrothermal processing of pyrite-bearing materials. Further work should focus on identifying sulfur speciation and surface states using high-resolution methods (e.g., XPS and thermogravimetric analysis) and on extending the approach to complex technogenic feedstocks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and D.R.; methodology, K.K. and T.L.; software, M.T. and U.S.; validation, D.R., T.L., and K.K.; formal analysis, U.S. and M.T.; investigation, M.T.; resources, D.R.; data curation, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T. and O.D.; writing—review and editing, K.K., T.L., and D.R.; visualization, U.S., O.D., and M.T.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K. and D.R.; funding acquisition, K.K. and D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation under Project No. 25-79-10290 https://rscf.ru/project/25-79-10290/ (accessed on 20 January 2026). Analytical studies were carried out with the financial support of the State Task of the Russian Federation under Grant No. 075-03-2024-009/1 (FEUZ-2024-0010).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- US Geological Survey. Copper Data Sheet–Mineral Commodity Summaries 2020; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2020/mcs2020-copper.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Dreisinger, D. Copper leaching from primary sulfides: Options for biological and chemical extraction of copper. Hydrometallurgy 2006, 83, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Copper Study Group. The World Copper Factbook 2019; ICSG: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; Available online: https://www.icsg.org (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kelchevskaya, N.R.; Altushkin, I.A.; Korol, Y.A.; Bondarenko, N.S. Peculiarities and importance of price formation in non-ferrous metallurgy (the case of copper concentrate production). Tsvetnye Met. 2016, 8, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altushkin, I.A.; Vorob’ev, A.G.; Kelchevskaya, N.R.; Korol, Y.A. Pricing in blister copper production: World market features and competitiveness requirements. Tsvetnye Met. 2017, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, M.; Sole, K.; Davenport, W.; Alvear Flores, G. Extractive Metallurgy of Copper, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorai, B.; Jana, R.K.; Premchand. Characteristics and utilization of copper slag—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2003, 39, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Ma, Y.; Gao, W.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, T. A review of the comprehensive recovery of valuable elements from copper smelting open-circuit dust and arsenic treatment. JOM 2020, 72, 3860–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.M.; Radzinski, R.; Ghahreman, A. Review of arsenic metallurgy: Treatment of arsenical minerals and the immobilization of arsenic. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 174, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.J.; Cook, N.J.; Grano, S.R.; Ehrig, K. Selective leaching of penalty elements from copper concentrates: A review. Miner. Eng. 2016, 98, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.A.; Finch, J.A. Wills’ Mineral Processing Technology: An Introduction to the Practical Aspects of Ore Treatment and Mineral Recovery, 8th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, S.; Szargan, R.; Suoninen, E. Interaction of copper(II) ions with pyrite and its influence on ethyl xanthate adsorption. Surf. Interface Anal. 1994, 21, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, T.; Alp, İ.; Deveci, H.; Celep, O. Production of a copper concentrate by flotation from Yomra–Kayabasi massive Cu–Zn sulfide ore. J. Sci. Technol. Dumlupinar Univ. 2008, 15, 57–64. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, A.P.; Gerson, A.R. A review of the fundamental studies of copper activation mechanisms for selective flotation of sphalerite and pyrite. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 145, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bıçak, Ö.; Ekmekçi, Z.; Can, M.; Öztürk, Y. The effect of water chemistry on froth stability and surface chemistry of flotation of a Cu–Zn sulfide ore. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2012, 102–103, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Rao, S.R.; Finch, J.A. An in-plant test of sphalerite flotation without copper activation. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual CMP Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 21–23 January 1992. Paper No. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Bozkurt, V.; Finch, J.A. Pyrite flotation in the presence of metal ions and sphalerite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1997, 52, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottermoser, B.G. Mine Wastes: Characterization, Treatment and Environmental Impacts, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottermoser, B.G. Recycling, reuse and rehabilitation of mine wastes. Elements 2011, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Tse, T.; Soufani, K. Is the circular economy a new fast-expanding market? Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 59, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossoff, D.; Dubbin, W.E.; Alfredsson, M.; Edwards, S.J.; Macklin, M.G.; Hudson-Edwards, K.A. Mine tailings dams: Characteristics, failure, environmental impacts, and remediation. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 51, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.W.; Goulart, F.F.; Ranieri, B.D.; Coelho, M.S.; Dales, K.; Boesche, N.; Soares-Filho, B. Deep into the mud: Ecological and socio-economic impacts of the Mariana dam breach (Brazil). Nat. Conserv. 2016, 14, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, C.A.C.; Santos, D.M.F.; Chen, Y.; Anastassakis, G. Chemical metathesis of chalcopyrite in acidic solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 92, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizer, O.; Rogozhnikov, D.; Karimov, K.; Kuzas, E.; Suntsov, A. Nitric Acid Dissolution of Tennantite, Chalcopyrite and Sphalerite in the Presence of Fe(III) Ions and FeS2. Materials 2022, 15, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.G.; Li, J.; Austin, P. High-Temperature Pressure Oxidation of Low-Grade Nickel Sulfide Concentrate with Control of Residue Composition. Minerals 2020, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzas, E.; Rogozhnikov, D.; Dizer, O.; Karimov, K.; Shoppert, A.; Suntsov, A.; Zhidkov, I. Kinetic Study on Arsenopyrite Dissolution in Nitric Acid Media by the Rotating Disk Method. Miner. Eng. 2022, 187, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, K.A.; Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Naboichenko, S.S.; Karimova, L.M.; Zakhar’yan, S.V. Autoclave Ammonia Leaching of Silver from Low-Grade Copper Concentrates. Metallurgist 2018, 62, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Zakharian, S.V.; Dizer, O.A.; Karimov, K.A. Nitric Acid Leaching of the Copper-Bearing Arsenic Sulphide Concentrate of Akzhal. Tsvetnye Met. 2020, 8, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozhnikov, D.A.; Mamyachenkov, S.V.; Karelov, S.V.; Anisimova, O.S. Nitric Acid Leaching of Polymetallic Middlings of Concentration. Russ. J. Non-Ferr. Met. 2013, 54, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fuentes, G.; Viñals, J.; Herreros, O. Hydrothermal purification and enrichment of Chilean copper concentrates. Part 2: Behavior of bulk concentrates. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 95, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritskii, A.; Naboichenko, S.; Karimov, K.; Agarwal, V.; Lundström, M. Hydrothermal pretreatment of chalcopyrite concentrate with copper sulfate solution. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 195, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritskii, A.; Fuentes, G.; Deveci, H. A Critical Review of Hydrothermal Treatment of Sulfide Minerals with Cu(II) Solution in H2SO4 Media. Hydrometallurgy 2025, 231, 106413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liao, Y.; Wu, M.; Jia, X. Acid-Free Ultrasonic-Enhanced Hydrothermal Leaching of Copper and Zinc from Polymetallic Sulfide Secondary Concentrates. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.D.; Wadsworth, M.E. Solid–solution reactions in the hydrothermal enrichment of chalcopyrite at elevated temperatures. In Proceedings of the EPD Congress; Warren, G.W., Ed.; TMS: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1994; pp. 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kritskii, A.; Celep, O.; Yazici, E.; Deveci, H.; Naboichenko, S. Hydrothermal treatment of sphalerite and pyrite particles with CuSO4 solution. Miner. Eng. 2022, 180, 107507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Cai, Y.; Qu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, K. Experimental investigation of the reactions between pyrite and aqueous Cu(I) chloride solution at 100–250 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 298, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, E.C.; de Souza, C.B.; de Almeida, I.C.; Vieira, M.M.; Dutra, A.J.B. Pyrite Oxidation Mechanism by Oxygen in Aqueous Medium. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 17527–17536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimstidt, J.D.; Vaughan, D.J. Pyrite Oxidation: A State-of-the-Art Assessment of the Reaction Mechanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, T. Dissolution and passivation mechanism of chalcopyrite during pressurized water leaching. Minerals 2023, 13, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Yang, S.; Zheng, X.; Deng, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Lignosulphonates in Zinc Pressure Leaching: Improving Sulfur Dispersion and Stabilizing Residue Impurities. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 140355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Dreisinger, D. Interfacial Properties of Liquid Sulfur in the Pressure Leaching of Nickel Sulfide Concentrates above the Melting Point of Sulfur. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Dreisinger, D. The Adsorption of Sulfur Dispersing Agents on Sulfur and Nickel Sulfide Concentrate Surfaces. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazieva, Z.K.; Mamyachenko, S.V.; Aleksandrova, T.N. Surfactants Influence on Sphalerite Wetting during Zinc Concentrate Pressure Leaching. Solid State Phenom. 2017, 265, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aro, T.; Fatehi, P. Production and Application of Lignosulfonates and Sulfonated Lignin. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1861–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billich, A.; Kolo, H.; Uhlig, M.; Koch, C.; Niemeyer, J.; Pfeiffer, A. Deciphering Molar Mass Distributions of Lignosulfonates with Asymmetric Flow Field-Flow Fractionation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 17385–17397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, Q.; Zheng, X.; Deng, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Li, J. Behavior of Calcium Lignosulphonate under Oxygen Pressure Leaching of a Zinc Sulfide Concentrate. Hydrometallurgy 2024, 230, 106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Chen, M.; Luo, H. Effects of Temperature, Oxygen Partial Pressure and Calcium Lignosulphonate on Chalcopyrite Dissolution in Sulfuric Acid Solution. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 3368–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Qiu, X.; Chen, P. Adsorption Characteristics of Lignosulfonates in Salt-Free and Electrolyte Solutions. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu, C.; Dreisinger, D.B. Interfacial Properties in Liquid Sulfur, Aqueous Zinc Sulfate and Zinc Sulfide Systems. Hydrometallurgy 1996, 43, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zies, E.G.; Allen, E.T.; Merwin, H.E. Some reactions involved in secondary copper sulphide enrichment. Econ. Geol. 1916, 11, 407–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, G.; Viñals, J.; Herreros, O. Hydrothermal purification and enrichment of Chilean copper concentrates. Part 1: Behavior of bornite, covellite, and pyrite. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 95, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritskii, A.; Naboichenko, S. Hydrothermal Treatment of Arsenopyrite Particles with CuSO4 Solution. Materials 2021, 14, 7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñals, J.; Fuentes, G.; Hernandez, M.C.; Herreros, O. Transformation of sphalerite particles into copper sulfide particles by hydrothermal treatment with Cu(II) ions. Hydrometallurgy 2004, 75, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.P.; Puskar, L.; Simpson, D.J.; Gerson, A.R. Copper and xanthate adsorption onto pyrite surfaces: Implications for mineral separation through flotation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2012, 114–117, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Peng, Y. The interaction between copper species and pyrite surfaces in copper cyanide solutions. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 158, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B. Electrodeposition on pyrite from copper(I) cyanide electrolyte. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisener, C.; Gerson, A.R. An Investigation of the Cu(II) Adsorption Mechanism on Pyrite by ARXPS and SIMS. Miner. Eng. 2000, 13, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Oertzen, G.U.; Skinner, W.; Nesbitt, H.W.; Pratt, A.; Buckley, A.N. Cu Adsorption on Pyrite (100): Ab Initio and Spectroscopic Studies. Surf. Sci. 2007, 601, 5794–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Z. Activation of Pyrite by Copper Ions and Its Depression by Thioglycollic Acid in the Flotation of a Complex Sulfide Ore. Minerals 2018, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Hu, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, D. Study of Galvanic Interactions between Pyrite and Chalcopyrite in a Flowing System. Environ. Geol. 2007, 52, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.