Abstract

A leachate from alkaline leaching of copper shaft furnace (CSF) dust as a hazardous waste was used in this study for performing a chemical precipitation experiment of lead, zinc, and copper. The precipitation processes for lead, zinc, and copper were theoretically optimized based on a thermodynamic study. To determine suitable operating conditions, metal phase stability, reaction mechanisms, and precipitation order were analyzed using the Hydra/Medusa and HSC Chemistry v.10 software packages. In the first experimental stage, treatment of the alkaline leachate resulted in the formation of insoluble lead sulfate (PbSO4), while zinc remained dissolved for subsequent recovery. In the second stage, the zinc-bearing solution was treated with Na2CO3, producing a mixed zinc precipitate consisting of Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2(s). This study determined that the optimal conditions for chemically precipitating lead as PbSO4 from alkaline leachate (pH 13.5) are the use of 1 mol/L H2SO4 at pH 3.09 and Eh 0.22 V at 25 °C, while optimal zinc precipitation from this solution (pH 3.02) is achieved with 2 mol/L Na2CO3 at pH 9.39 and Eh –0.14 V at 25 °C. A small amount of copper present in the solution co-precipitated and was identified as an impurity in the zinc product. The chemical composition of the resulting precipitates was confirmed by SEM–EDX analysis.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, a global increase in electric vehicle sales has been observed, leading to a more than four times increase in copper consumption within this sector [1,2]; therefore, in the European Union, copper is considered a critical and strategic raw material [3,4].

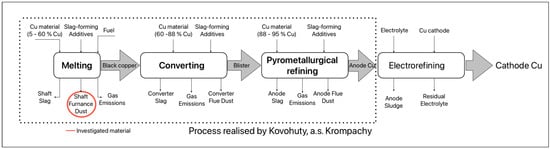

The pyrometallurgical process of copper production, depending on the treatment of primary or secondary raw materials, is carried out in three main stages: smelting, converting, and refining [5,6]. The scheme of secondary copper production is shown in Figure 1. Flue dust is generated in all three processes. They differ in chemical composition, which depends on the mineralogical composition of the concentrates, the melt, and the circulating materials (slag, flue dust, etc.) and their respective ratios [7].

Figure 1.

Pyrometallurgical production of secondary copper.

During the thermal processes of copper production, fine dust particles known as flue dust are generated. According to the European Waste Catalogue, flue dust is classified as hazardous waste [8]. With the need for increased copper production, the amount of this waste will also rise. Flue dust from copper production contains heavy metals, primarily zinc, lead, and tin, as well as residual copper in oxide form [9]. Among the priorities of the EU waste management strategy is the effort to increase the recycling rate of waste before its energy recovery [10]. It is, therefore, essential to apply processing methods to copper production flue dust that allow for the recovery of metals or compounds based on zinc, lead, tin, and copper within acceptable technological and environmental requirements. Considering the composition of the flue dust, hydrometallurgical processing methods are preferred, as they are less environmentally demanding than pyrometallurgical techniques [11,12].

Several authors worldwide have studied the hydrometallurgical treatment of flue dust. The leaching agents used include sulfuric acid solutions [11,13,14], acetic acid [15], nitric acid [16], and sodium hydroxide solutions [17,18]. Research has also addressed pre-treatment processes, such as oxidative roasting, prior to leaching [19]. Jianyong Che et al. [20] studied an environmentally friendly process that selectively recovers As, Cu, Pb, Zn, and Bi from copper smelting flue dust through low-temperature roasting, leaching in dilute scrubbing H2SO4, and cementation, while Pb and Bi are subsequently processed mechanochemically or electrolytically. Jun Chen et al. [21] investigated that adding H2SO4 significantly lowers the roasting temperature and promotes the formation of soluble metal sulfates, with over 99% of Cl and Br removed at 325 °C using 1.5 × H2SO4; in addition, Cu, Zn, and Cd were almost completely leached in water. Microwave-assisted leaching, used in study [22], showed that non-microwave leaching occurs in two stages due to the formation of a product layer, whereas microwave-assisted leaching reduces the formation of this layer and enhances copper dissolution. Multiple extraction methods were investigated in the process of recovering metals (Zn, Pb, Sn, and Cu) from the leachate, such as chemical precipitation, cementation, or solvent extraction [15,17,23]. The authors [24] investigated the direct separation of copper and zinc from a highly acidic leaching solution. Copper and part of the zinc were precipitated using H2S, and then the zinc remaining in the residue was re-leached with the original leaching solution. For the precipitation of copper sulfide from acidic sulfate solution, H2S was also used [25]. Solvent extraction is used for the separation of Cu and Zn from acidic solutions after leaching dust wastes, with laboratory tests achieving Cu yields of 69–87% and Zn yields of 75–80% [26]. Chemical precipitation was then used to selectively separate zinc and lead from the leach solution, with sodium sulfide successfully precipitating lead at a Na2S/Pb ratio of ~2.0 and zinc at a Na2S/Zn ratio of ~3.0 [27]. The optimal conditions for copper involved using nitric acid (4 mol/L) at a temperature of 80 °C, achieving a copper leaching efficiency of 99.4%. Copper was then synthesized as copper oxide through precipitation from the leach solution [16].

The main objective of this research is to perform thermodynamic predictions through the construction and analysis of speciation and Pourbaix diagrams under defined conditions in a CSF dust leaching system, followed by the subsequent precipitation of lead and zinc from solution. The optimal leaching parameters were determined by considering the stability of various chemical species of zinc, lead, copper, and tin, as well as their distribution as a function of pH and redox potential.

Furthermore, this study proposes the optimal concentrations of sulfuric acid for lead precipitation and sodium carbonate for zinc precipitation to provide deeper insight into the complex reaction system and to establish optimal process parameters. To predict the most suitable operating conditions, an analysis of metal phase stability, possible chemical reactions, and their relative order was carried out using the Hydra/Medusa software package (https://speciation.net/Database/Components/HydraMedusa-;i1947) and HSC Chemistry v.10.

In addition to the thermodynamic assessment, this work focuses on the hydrometallurgical processing of CSF dust with the aim of recovering marketable zinc- and lead-based products. The valorization of hazardous waste into commercially viable materials would significantly contribute to addressing the challenges associated with CSF dust treatment, a by-product generated during copper production. Special attention is also given to evaluating the influence of impurities such as Cu and Sn present in the leach solution, as their behavior can substantially affect both the efficiency and selectivity of the precipitation processes.

2. Materials and Methods

Chemical analysis of solid and liquid samples was performed using a combination of X-ray fluorescence spectrometry (XRF) (SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH, Kleve, Germany) and atomic absorption spectroscopy AAS (iCE 3300 AA-ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA), depending on the elemental composition and detection requirements. Samples of CSF dust and produced precipitates were characterized by scanning electron microscope (SEM) (MIRA 3 FE-SEM microscope TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) equipped with a high-resolution cathode (Schottky field emitter), a three-lens Wide Field OpticsTM design, and an Energy-dispersive X-ray detector (EDX) (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK).

The redox potential (Eh) and pH were measured using an Orion Lab Star PH111 pH meter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Pourbaix Eh–pH diagrams were employed to evaluate the leaching thermodynamics using HSC Chemistry, version 10 (Metso Finland Oy, Espoo, Finland). Predicted speciation diagrams in aqueous solutions were generated using MEDUSA software (version 32-bit, 2010, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden) (Make Equilibrium Diagrams Using Sophisticated Algorithms).

All chemical reagents used for leaching and precipitation experiments are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The usage, purpose, and properties of the leaching reagents.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Alcaline Leaching

The alkaline leachate used in the experiments conducted in this laboratory research was obtained by alkaline leaching a copper shaft furnace (CSF) dust sample from secondary copper production at the company Kovohuty, a. s., Krompachy (Krompachy, Slovakia). The CSF dust, containing 44.02% Zn, 14.57% Pb, 1.12% Cu, and 1.59% Sn, predominantly occurs in the flue dust in an oxidic form. The alkaline leaching aimed to extract the metals (Zn, Pb, Cu, and Sn) into solution under conditions that would achieve the highest possible yield of lead in the leachate. The optimal leaching conditions (1 mol/L NaOH solution, pH 14, temperature 80 °C, liquid-to-solid ratio of 20, under atmospheric pressure) were adopted from the study by Laubertová et al. [17].

Oxides SnO2, PbO, and ZnO are amphoteric and dissolve in a basic 2 mol/L NaOH solution (pH 14) at 80 °C, forming stable complex ions [Sn(OH)6]2−, [HPbO2]−, and [Zn(OH)4]2−. CuO decomposes at high temperatures in NaOH at pH 14 to the complex [Cu(OH)4]2−, but is not considered amphoteric. Navarro M. et al. [28] confirmed the solubility of CuO in NaOH. SnO2 has high solubility and forms stable complexes. The solubility of PbO and ZnO is lower, and some of the oxide may remain partially undissolved in the solution. Higher leaching temperature (80 °C) enhances the dissolution kinetics but only slightly affects the equilibrium potential (Eh). The leaching chemical Equations (1)–(4), based on thermodynamic predictions, are proposed, and their values of Gibbs free energy at a temperature of 80 °C are provided in Table 2. A comparison of the ΔG°T values from Equations (1) and (4) shows that all equations have a high probability of proceeding in the direction of product formation.

Table 2.

Values of Gibbs free energy (at 80 °C and pH 14) of Equations (1)–(4).

3.2. Chemical Precipitation

After the leaching process was completed, the process of recovering metals or their compounds from the solution using the chemical precipitation method followed. The solution obtained after alkaline leaching contained 8651 ppm Pb, 1630 ppm Zn, and 97.5 ppm Cu. This solution provided the initial sample for lead precipitation and was designated as MRD82. The pH value of the solution was 13.05, and the measured redox potential (Eh) was −0.350 mV. The aim of this part of the process was to extract metals from the solution to form sparingly soluble (or insoluble) compounds, which can then be used in the next metal production process. The appropriate precipitating agent must be selected according to the solubility of inorganic compounds in water based on its further commercial use and environmental impact. Therefore, in the first step, the research focused on the selective recovery of lead from the solution, followed by studying possible methods for recovering zinc, copper, or tin from the solution.

3.2.1. Lead Precipitation

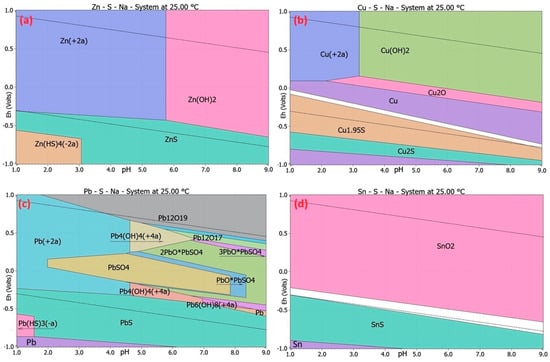

Lead sulfate (PbSO4) can be considered a useful lead compound, as it is used as an active material in lead-acid batteries [29]. Lead sulfide (PbS) can be used as a raw material for lead smelting and production of metallic lead [24]. For the precipitation of lead from the alkaline leachate, a 0.5 mol/L sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution was used for experiments. To predict the precipitation conditions, Eh–pH diagrams (pH—the acidity/basicity of the environment; Eh—the electrochemical potential) of the systems Zn–S–Na–H2O, Cu–S–Na–H2O, Pb–S–Na–H2O, and Sn–S–Na–H2O were studied at 25 °C and at a pressure of 101,325 Pa using HSC Chemistry software, version 10 [30]. Eh–pH diagrams, also known as Pourbaix diagrams, illustrate the thermodynamic stability regions of various species in an aqueous solution. These stability regions are displayed as a function of pH and electrochemical potential.

Figure 2 shows the potential–pH diagrams of the Zn–S–Na–H2O, Cu–S–Na–H2O, Pb–S–Na–H2O, and Sn–S–Na–H2O systems at 25 °C, based on all species’ specification and using a 1 to 9 pH scale.

Figure 2.

Eh–pH diagrams of (a) Zn–S–Na–H2O, (b) Cu–S–Na–H2O, (c) Pb–S–Na–H2O, (d) Sn–S–Na–H2O systems at 25 °C, based on all species’ specification, using 1 to 9 pH scale. Zn, Cu, Pb, and Cu are the main elements in each diagram. The modalities of elements are 1 mol/kg H2O. The upper and lower stability limits of water are indicated by dotted lines. The asterisk in a chemical formula is a multiplication sign.

Based on the thermodynamic predictions, the following chemical equations are proposed. Equations (5)–(13) describe the behavior of Zn, Pb, Cu, and Sn after the addition of sulfuric acid as a precipitating agent to the alkaline leachate. Equations (5)–(13), with their values of Gibbs free energy at a temperature of 25 °C, are listed in Table 3. Negative values of standard Gibbs energies indicate that the reactions will proceed in the direction of reactant formation and should be spontaneous at a temperature of 25 °C.

Table 3.

Proposed equations for the precipitation of metals from the solution using H2SO4 (pH range from 1 to 9) at 25 °C.

The Eh–pH diagram shown in Figure 2a displays that zinc is present in the solution as Zn2+ at a temperature of 25 °C in the pH range of 1–5.6 with (Eh = –0.2 to 1 V) and (Eh = –0.3 to 0.6 V), and at a pH of 5.6–9 with (Eh = –0.3 to 0.6 V) and (Eh = –0.9 to 0.2 V), and as insoluble Zn(OH)2(s) in stability limits of water, Equations (5) and (6). The Eh–pH diagram shown in Figure 2b displays that copper is present in the solution as Cu2+ at a temperature of 25 °C in the pH range of 1 to 3.2 with (Eh = 0.1 to 0.9 V), and at a pH of 1–3.2 with (Eh = 0.2 to 0.8 V), and pH 3.2 to 9 (Eh = –0.5 to 0.2 V) as insoluble Cu(OH)2(s) in stability limits of water, Equations (8) and (9).

The Eh–pH diagram shown in Figure 2c displays that lead is in the solution, presenting as Pb2+ at a temperature of 25 °C in the pH range of 1–4.5, and it contains a region of an insoluble compound PbSO4 at pH 2 to 7.8 (Eh = 0.2 to −0.2 V) in stability limits of water, Equation (11). Equation (14) shows that tin is insoluble as SnO2(s) in the pH range 1–9. In this area, compound Sn(SO4)O2 is shown. The solubility product (Ks) of the insoluble compound Zn(SO)4 is 3.263 × 10−17, Cu(SO)4 is 2.618 × 10−22, and PbSO4 is 1.514 × 10−8 at 25 °C, Equations (7), (10) and (12).

Thermodynamic studies indicate that Zn and Cu remain in solution at around pH 3 and an Eh of approximately 0.2 V, whereas Pb will precipitate from the solution as the sparingly soluble compound PbSO4 at 25 °C. This statement is further supported by the prediction of fraction diagrams in aqueous solutions created using the MEDUSA software, which has been used to predict the conditions for Zn and Pb recovery in several research studies [31,32].

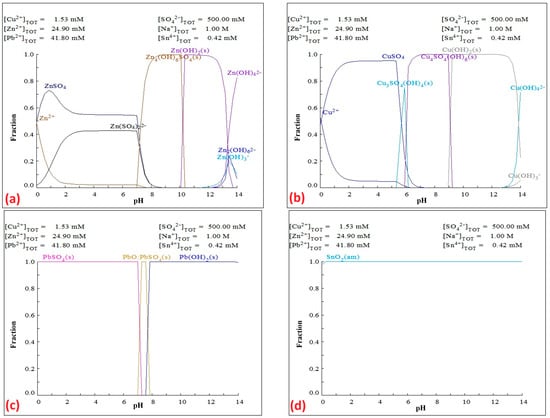

Figure 3 shows the fraction diagrams of metal precipitation occurring in an alkaline solution upon the addition of H2SO4.

Figure 3.

Predicted fraction diagrams of the (a) ZnSO4–NaOH–H2O, (b) CuSO4–NaOH–H2O, (c) PbSO4–NaOH–H2O, and (d) SnO2–NaOH–H2O at 25 °C at the potential Eh = 0.22 V.

Figure 3a shows the fraction diagram of Zn precipitation using H2SO4, from which it can be inferred that Zn is likely to be present in solution as Zn(OH)2(s) in the pH range of 10.5–13.5, while a narrow region of Zn4(OH)6SO4(s) formation occurs in the pH range of 8–10. In the pH range of 0–7, zinc is likely to be present in solution as ionic ZnSO4, Zn2+, and Zn(SO4)22, confirmed by research study authors Gajic et al. [33].

Figure 3b shows the fraction diagram of Cu precipitation using H2SO4, from which it can be inferred that Cu is present in solution as Cu(OH)2(s) in the pH range of 9.5–14. In the pH range of 6–9.5, a region of Cu4SO4(OH)6(s) formation occurs, and in the pH range of 5.5–6, a region of Cu3SO4(OH)4(s) formation appears, which overlaps with the region of CuSO4 formation (pH 0–6) with Cu2+ ions.

Figure 3c shows the fraction diagram of Pb precipitation using H2SO4, from which it can be inferred that in the pH range of 8–14, lead is present in solution as Pb(OH)2(s), while a narrow region of PbO:PbSO4(s) formation occurs between pH 7 and 8. Lead precipitates from the solution as PbSO4 in the pH range of 0–7.

Figure 3d shows the fraction diagram of Sn precipitation using H2SO4, from which it can be inferred that Sn is likely present as amorphous SnO2 in the pH range of 12–14. Tin is not present in the solution after leaching in the proposed treatment of CSF dust. Based on a thermodynamic study of Eh–pH and fraction diagrams, its precipitation together with lead in the current process is not expected, although its removal would be necessary if some Sn were to leach from the dust, which represents a topic for further research.

A 1 mol/L H2SO4 solution was used for the precipitation of lead from the alkaline leachate (pH 13.05). During the precipitation process, pH and redox potential (Eh) were continuously monitored at 25 °C under constant stirring at 300 rpm. The input sample for each experiment was the MRD82 sample. Gradual addition of the reagent led to the formation of precipitates in the solution at various pH values (Table 4). The resulting suspensions were subsequently filtered and dried. The filtrates were analyzed using AAS to determine their elemental composition, and their Eh values were measured. The dried precipitates were analyzed by SEM–EDX to determine their elemental composition. Each experiment under identical conditions was repeated three times. At pH 3.09 and Eh 0.225 V, 99% of Pb ions were precipitated (white precipitate), while Zn ions (1198 ppm) and Cu ions (67 ppm) remained in the solution. The formation of the white precipitate confirms the expected formation of PbSO4, as predicted by the thermodynamic study based on the Eh–pH diagrams (Figure 2) and the fractional diagrams (Figure 3). A similar situation was observed at pH 5.16 and Eh 0.103 V.

Table 4.

Results of the chemical analysis by AAS of the solutions before and after Pb precipitation, including their pH and Eh values.

At pH 7.75 and Eh −0.047 V, lead also precipitated as a white solid; however, the Zn concentration in the solution (60.2 ppm) indicates that zinc had begun to co-precipitate into the white solid phase. At pH 12 (Eh −0.295 V), Pb (335.6 ppm), Zn (24.5 ppm), and Cu (2.7 ppm) were precipitated. The formation of a blue–green precipitate indicates the presence of Cu(OH)2, in agreement with Figure 2 and Figure 3. This is also supported by the thermodynamic study of Gajić et al. [33], who confirmed that if the pH value exceeds 3.5, the leached copper may precipitate in the form of Cu3SO4(OH)4, Cu4SO4(OH)6, or CuO. The formation of Pb in the form of hydroxides is also possible. The analytical results obtained after precipitation are summarized in Table 4. Based on the changes in the concentrations of Pb, Zn, and Cu ions in the MRD86 solution relative to the initial MRD82 sample, it can be concluded that nearly 99% of Pb was precipitated from the solution, while Zn losses reached 26.5%, and Cu losses reached 30%. However, when comparing the metal content at the input and output, the Zn and Cu present in the precipitate may be considered impurities. The addition of 1 mol/L H2SO4 may have contributed to the observed decrease in the concentrations of Zn and Cu in the MRD86 solution. The decrease in concentrations may result not only from precipitation but also from the change in the solution volume.

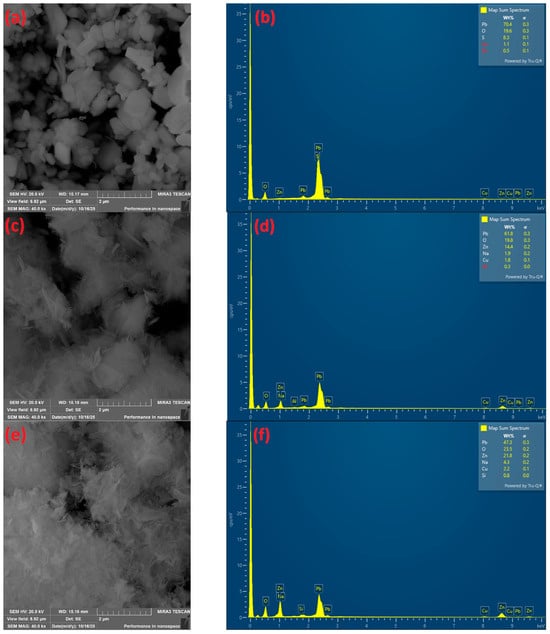

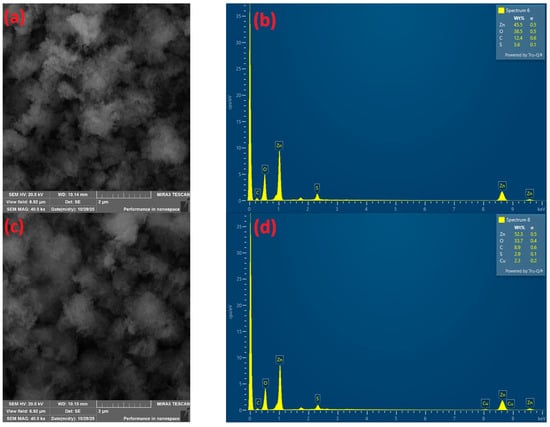

The resulting precipitates were subjected to SEM–EDX analysis to determine their morphology and chemical composition (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Morphology of precipitate SEM analysis at (a) pH 3.09, (c) pH 7.75, (e) pH 12, at 40,000× magnification. EDX analysis of precipitate at (b) pH 3.08; (d) pH 7.75; (f) pH 12.

The morphology of the precipitate sample at pH 3.9, observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), is shown in Figure 4a. In Figure 4a, the sample morphology is presented at a magnification of 40,000×, revealing particles of various shapes, with the majority exhibiting a blocky, angular form. EDX analysis (Figure 4b) indicated the presence of the major elements Pb, O, and S. Based on the EDX results, as well as theoretical studies of the Eh–pH and fractional diagrams, the precipitate is most likely PbSO4 [17].

The morphology of the precipitate at pH 7.75 (Figure 4b) and at pH 12 (Figure 4c) reveals “cotton-like” particles forming smaller aggregates, with occasional needle-shaped particles. EDX analysis indicated the presence of the major elements Pb, Zn, Cu, and O (Figure 4d). Based on the EDX results and theoretical studies of the Eh–pH and fractional diagrams, the precipitates are likely composed of lead, zinc, and copper hydroxide compounds.

3.2.2. Zinc Precipitation

In the second stage of leachate processing (pH 3), the objective was to recover zinc from the solution as an insoluble compound that could be further utilized in industry, using a suitable precipitating agent. An example of a slightly soluble compound is ZnCO3, which is employed as a pigment, corrosion inhibitor, in cosmetics, and for other applications. The solubility product (Ks) of zinc carbonate (ZnCO3) at 25 °C and an ionic strength of I = 0.0 mol·dm−3 is 1.276 × 10−10. Based on the properties of this compound, as well as environmental considerations, Na2CO3 was chosen as the precipitating agent. The Eh–pH diagrams of the individual systems were studied (Figure 5).

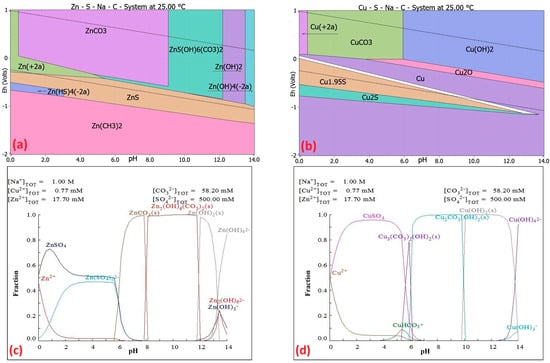

Figure 5.

Eh–pH diagrams of (a) Zn–S–Na–C–H2O and (b) Cu–S–Na–C–H2O systems at 25 °C, based on all species’ specification, using 0 to 14 pH scale. Zn and Cu are the main elements in each diagram. The modalities of elements are 1 mol/kg H2O. The upper and lower stability limits of water are indicated by dotted lines. Predicted fraction diagrams display (c) Zn–Na2CO3–H2O and (d) Cu–Na2CO3–H2O at 25 °C at the potential Eh = −0.14 V.

From the Eh–pH diagrams of the Zn–S–Na–C–H2O system (Figure 5a) and the Cu–S–Na–C–H2O system (Figure 5b), it can be concluded that precipitation will occur within the pH range of 1.5 to 9 according to Equations (14) and (15), whereas at pH 9.2 to 12.3, the formation of Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2 precipitate would occur (Table 5). Copper in this pH range is expected to precipitate as CuCO3 (pH 0.3–5.9) and as Cu(OH)2 (pH 5.9–14) at 25 °C. Equations (14)–(21), along with their Gibbs free energy values at 25 °C, are presented in Table 5. The solubility products (Ks) of the insoluble compounds ZnCO3(s), Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2, CuCO3(s), and Cu(OH)2(s) are also listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Proposed equations for the precipitation of metals from the solution using Na2CO3 (pH range from 0 to 14) at 25 °C.

Figure 5 shows the fraction diagrams (created using the MEDUSA software) for the precipitation of metals from the solution using Na2CO3 [11,31].

Figure 5c shows the fraction diagram for Zn precipitation using Na2CO3, which indicates that with the addition of Na2CO3, Zn begins to precipitate from pH 6. From pH 8 to 12, zinc precipitates from the solution as Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2(s). From pH 12 to 13.5, it occurs as Zn(OH)2(s).

Figure 5d shows the fraction diagram for Cu precipitation using Na2CO3, indicating that in the pH range 6–10, Cu in solution is likely present as Cu2CO3(OH)2(s) (100% of the precipitate), while at pH 10–13.5, it occurs as Cu(OH)2(s). At lower pH values, depending on the concentration in the solution, Cu may exist either in ionic form or as a precipitate. Zinc extraction from the solution after lead precipitation is carried out by the precipitation method. Based on theoretical knowledge of precipitation, solubility studies of individual inorganic compounds, and their environmental impact, sodium carbonate is considered the most suitable precipitating agent for zinc extraction, targeting a solution pH of approximately 9.

For the precipitation experiments, a 2 mol/L Na2CO3 solution (precipitating agent) was used at 25 °C under continuous stirring at 300 rpm. During the precipitation process, pH and redox potential (Eh) were measured. The feed solution for each experiment consisted of the post-lead-precipitation solutions. The resulting precipitates were filtered, dried at 65 °C, and analyzed by SEM–EDX to determine their morphology and chemical composition. The resulting solutions were filtered, and liquid samples were collected for analysis by AAS to confirm the content of the target metals and the precipitation of Zn ions from the solution. At pH 9.11, more than 99% of Zn was precipitated from the solution (Table 6); however, along with zinc, over 98% of Cu also precipitated. The redox potential at this pH was −0.123 V, which corroborates the theoretical prediction of PbSO4 formation based on the Eh–pH and fraction diagrams. The addition of 2 mol/L Na2CO3 may have contributed to the observed decrease in the concentrations Cu and Zn in the MRD94 solution.

Table 6.

Results of chemical analysis by AAS of the solutions before and after Zn precipitation, along with their corresponding pH and Eh values.

The morphology of the precipitate formed at pH 9.39 was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Figure 6a). In Figure 6a, the morphology at a magnification of 40,000× shows fine particles aggregated into clusters. EDX analysis (Figure 6b) revealed the presence of Zn, C, O, and S. Based on the EDX results and theoretical studies of the Eh–pH and fraction diagrams, the precipitate is likely a zinc-based compound, such as Zn(OH)2, Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2(s), and Zn4(OH)6SO4(s).

Figure 6.

Morphology of precipitate SEM analysis at (a) pH 9.39 and (c) pH 8.69, at 40,000× magnification; EDX analysis of precipitate at (b) pH 9.39 and (d) pH 8.69.

The morphology of the precipitate at pH 8.69, observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), is shown in Figure 6c. In Figure 6c, the particle morphology exhibits smaller particles, forming “cotton-like” aggregates. EDX analysis (Figure 6d) indicated the presence of Zn, Cu, C, O, and S. Based on the EDX results and theoretical studies of the Eh–pH and fraction diagrams, the precipitate likely consists of zinc-based compounds (Zn(OH)2, Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2(s), and Zn4(OH)6SO4(s)) and copper (Cu(OH)2). However, by comparing the metal content in the input and output, Zn and Cu in the precipitate can be considered impurities. EDX analysis does not allow for a definitive confirmation of the exact stoichiometry or purity of the precipitate at the trace-element level. It is also necessary to focus on determining the XRD analysis of the precipitate, as documented in the work of authors [17].

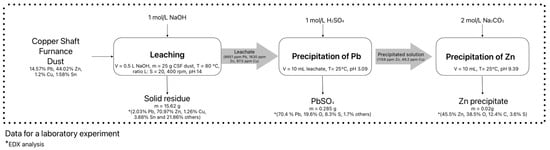

Figure 7 illustrates the proposed scheme for hydrometallurgical processing of CSF dust. Following the leaching of CSF dust under optimal conditions, the first extraction phase involves the precipitation of lead from the solution using the precipitating agent H2SO4 to achieve pH 3.09, resulting in the formation of PbSO4. In the second extraction phase, zinc is precipitated using the precipitating agent Na2CO3, forming a zinc-based precipitate at pH 9.39 and 25 °C. At each stage, the amounts of reagents added, the masses and compositions of solids, and the compositions and volumes of solutions are tracked to provide a clear overview of the material flows and to illustrate the distribution of metals throughout the process. The amounts of the precipitating agents H2SO4 and Na2CO3 were added after the pH of the solution was adjusted.

Figure 7.

Proposed basic scheme for hydrometallurgical processing of CSF dust.

4. Conclusions

The present theoretical study focuses on the extraction of metals from the solution obtained after alkaline leaching of CSF dust as a hazardous waste. The precipitation processes for lead and zinc were successfully optimized theoretically by designing them based on a thermodynamic study, which determined their optimal parameters:

- For efficient precipitation of lead from an alkaline solution at pH = 14, lead forms the insoluble compound PbSO4 within the pH range 2 to 7.8 (Eh = 0.2 to –0.2 V) within the stability limits of water;

- For efficient precipitation of zinc from an acidic solution in the pH range 6–8, Zn is expected to precipitate as ZnCO3;

- If the solution also contains Cu, copper will precipitate in the form of Cu2CO3(OH)2(s) (pH 6–10) and as Cu(OH)2(s) (pH 10–13.5) at ambient temperatures and will be present as an impurity in the zinc precipitate.

The first stage of the experimental work included processing the alkaline leachate formed in the insoluble compound of lead sulfate (PbSO4) as a solid precipitate, while zinc remained in ionic form in the solution for subsequent recovery. This solution was utilized in the second stage of the process by adding Na2CO3, resulting in a zinc-based precipitate consisting of Zn(OH)2 (12–13.5 pH) and Zn5(OH)6(CO3)2(s) (8–12 pH). In addition, the experimental investigation led to the following conclusions:

- The optimal conditions for precipitating lead as PbSO4 from an alkaline leachate (pH 13.5) are a 1 mol/L H2SO4 solution at pH 3.09 and Eh 0.22 V at 25 °C;

- The optimal conditions for precipitating zinc from this solution (pH 3.09) are the use of 2 mol/L Na2CO3 as the precipitating agent at pH 9.39 and Eh −0.14 V at 25 °C.

Since the solution contained small amounts of copper, this fraction also precipitated and is considered an impurity in the resulting zinc precipitate. The final precipitates were subjected to SEM–EDX analysis to confirm their chemical composition.

Further research is required, and the next stage should include testing the process illustrated in Figure 7. In this phase, it is essential to conduct optimization studies with a broader range of investigated variables, as well as to evaluate the effects of different concentrations of precipitating solutions during the precipitation process, with an emphasis on kinetic modeling. In addition, further research should focus on the removal of copper prior to zinc precipitation from the solution. Copper coprecipitation under optimal zinc precipitation conditions can reduce the purity of Zn-rich precipitates and negatively affect subsequent hydrometallurgical processing. Because copper has a higher redox potential than zinc, it can be selectively reduced prior to zinc precipitation, converting Cu2+ to metallic Cu or Cu+ species. This can be achieved, for example, by cementation using powdered zinc, although this approach requires experimental verification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and M.R.; methodology, M.L. and M.R.; validation, M.L.; formal analysis, M.M. and M.L.; investigation, M.L. and M.R.; resources, M.L.; data curation, M.L. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.L.; visualization, M.R. and M.M.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.R. and M.M.; funding acquisition, M.M. and M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded from EU NextGenerationEU funds through the Recovery and Resilience Plan for Slovakia under project No. 09I03-03-V05-00015. This research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Sport of the Slovak Republic under grant number VEGA 1/0247/23 and VEGA 1/0408/23.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through cooperation with the company Kovohuty, a. s., Krompachy, which provided a sample of CSF dust, and with the Institute of Geotechnics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, v. v. i., Košice, for carrying out selected analyses, especially Jaroslav Briančin.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, C.L.; Xu, M.; Cui, S.; Li, Z.; Fang, H.; Wang, P. Copper-induced ripple effects by the expanding electric vehicle fleet: A crisis or an opportunity. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, S.; Pauliuk, S. Sector-level estimates for global future copper demand and the potential for resource efficiency. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohol, M.; Veeh, C. Study on the Critical Raw Materials for the EU 2023: Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; ISBN 978-92-68-00414-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cehlár, M.; Šimková, Z. Critical raw materials as a part of sustainable development. Multidiszcip. Tudományok 2021, 11, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, M.E.; Sole, K.C.; Davenport, W.G.; Alvear Flores, G.R.F. Extractive Metallurgy of Copper, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Forsén, O.; Aromaa, J.; Lundström, M. Primary copper smelter and refinery as a recycling plant—A system integrated approach to estimate secondary raw material tolerance. Recycling 2017, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orac, D.; Laubertova, M.; Piroskova, J.; Klein, D.; Bures, R.; Klimko, J. Characterization of dusts from secondary copper production. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B Metall. 2020, 56, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Waste Catalogue and Hazardous Waste List. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/2503/dokumente/2014-955-eg-en.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Okanigbe, D.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Adeleke, A.A. Characterization of Copper Smelter Dust for Copper Recovery. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 7, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Inverno, G.; Carosi, L.; Romano, G. Meeting the challenges of the waste hierarchy: A performance evaluation of EU countries. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oráč, D.; Klimko, J.; Klein, D.; Pirošková, J.; Liptai, P.; Vindt, T.; Miškufová, A. Hydrometallurgical recycling of copper anode furnace dust for a complete recovery of metal values. Metals 2022, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlik, T. Chapter 12—Leaching of Copper Sulphides. In Hydrometallurgy: Principles and Application, 1st ed.; Series in Metals and Surface Engineering; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84569-407-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dosmukhamedov, N.; Zholdasbay, E.; Argyn, A. Extraction of Pb, Cu, Zn and As from Fine Dust of Copper Smelting Industry via Leaching with Sulfuric Acid. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiyski, M.; Angelov, N.; Iliev, P.; Stefanov, E.; Semerdzhiev, T.; Sopotenska, I. Treatment of Copper Flue Dust From Flash Furnace Waste Heat Boiler for Impurities Control. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2024, 59, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubertová, M.; Kollová, A.; Trpčevská, J.; Plešingerová, B.; Briančin, J. Hydrometallurgical treatment of converter dust from secondary copper production: A study of the lead cementation from acetate solution. Minerals 2021, 11, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Ghosh, A.; Saravanan, V.; Jain, R. Hydrometallurgical separation of iron and copper from copper industrial dust waste and recovery of copper as copper oxide. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2025, 7, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubertová, M.; Sisol, M.; Briančin, J.; Trpcevská, J.; Ružizičková, M. Recovery of Valuable Materials Based on Pb and Zn in the Hydrometallurgical Processing of Copper Shaft Furnace Dust. Materials 2025, 18, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamutan, J.; Koide, S.; Sasaki, Y.; Nagasaka, T. Selective dissolution and kinetics of leaching zinc from lime treated electric arc furnace dust by alkaline media. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanigbe, D.O.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Adeleke, A.A.; Otunniyi, I.O.; Popoola, O.M. Investigating the impact of pretreating a waste copper smelter dust for likely higher recovery of copper. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 35, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Zhang, W.; Deen, K.M.; Wang, C. Eco-friendly treatment of copper smelting flue dust for recovering multiple heavy metals with economic and environmental benefits. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Ma, B.; Che, J.; Xia, L.; Wen, P.; Wang, C. Recovering metals from flue dust produced in secondary copper smelting through a novel process combining low temperature roasting, water leaching and mechanochemical reduction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzezari, B.; Koleini, S.M.J.; Ghassa, S.; Shahbazi, B.; Chelgani, S.C. Microwave-leaching of copper smelting dust for Cu and Zn extraction. Materials 2019, 12, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Fu, X.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, D. Hydrometallurgical Treatment of Copper Smelting Dust by Oxidation Leaching and Fractional Precipitation Technology. JOM 2017, 69, 1982–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youcai, Z.; Stanforth, R. Selective separation of lead from alkaline zinc solution by sulfide precipitation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2001, 36, 2561–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Wei, Y.; Li, L.; Mumford, K.A.; Stevens, G.W. An investigation into the precipitation of copper sulfide from acidic sulfate solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 192, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Steenari, B.M. Solvent extraction separation of copper and zinc from MSWI fly ash leachates. Waste Manag. 2015, 44, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, D.M.; Martins, F.B. Lead and zinc selective precipitation from leach electric arc furnace dust solutions. Matéria 2007, 12, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.; May, P.M.; Hefter, G.; Königsberger, E. Solubility of CuO(s) in highly alkaline solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 147–148, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, P.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Hu, Y.; Liang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Xiao, K.; Hou, H.; et al. A low-emission strategy to recover lead compound products directly from spent lead-acid battery paste: Key issue of impurities removal. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roine, A. HSC Chemistry® Software, version 11; Outotec Research Oy: Pori, Finland, 2023.

- Picazo-Rodríguez, N.G.; Soria-Aguilar, M.D.J.; Martínez-Luévanos, A.; Almaguer-Guzmán, I.; Chaidez-Félix, J.; Carrillo-Pedroza, F.R. Direct acid leaching of sphalerite: An approach comparative and kinetics analysis. Minerals 2020, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.E.; Santucci, R.J.; Scully, J.R. Advanced chemical stability diagrams to predict the formation of complex zinc compounds in a chloride environment. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19905–19916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajić, N.; Ranitović, M.; Marković, M.; Kamberović, Ž. Thermodynamics Study for Selective Leaching of Copper and Zinc from Complex Secondary Raw Materials Using Oxidative Sulfuric Acid Leaching. Metall. Mater. Data 2023, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).