Analysis of the Regulatory Effect of Semi-Solid Isothermal Treatment Time on Crystallization and Plasticity of Amorphous Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

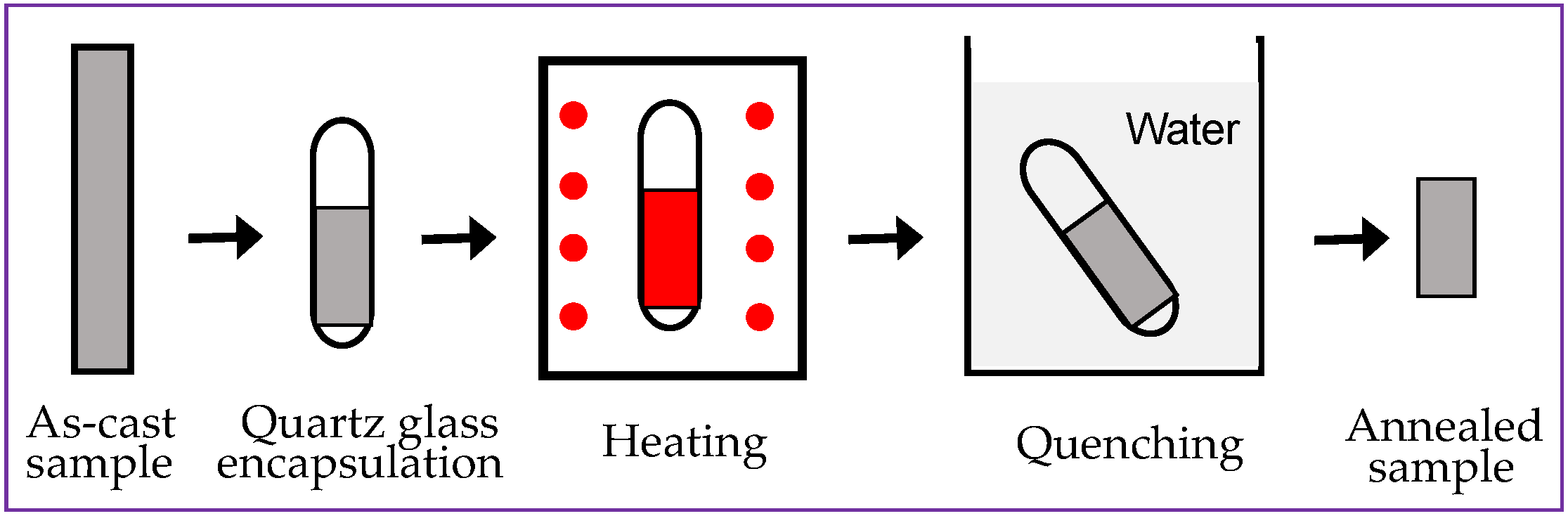

2. Experiment

3. Results

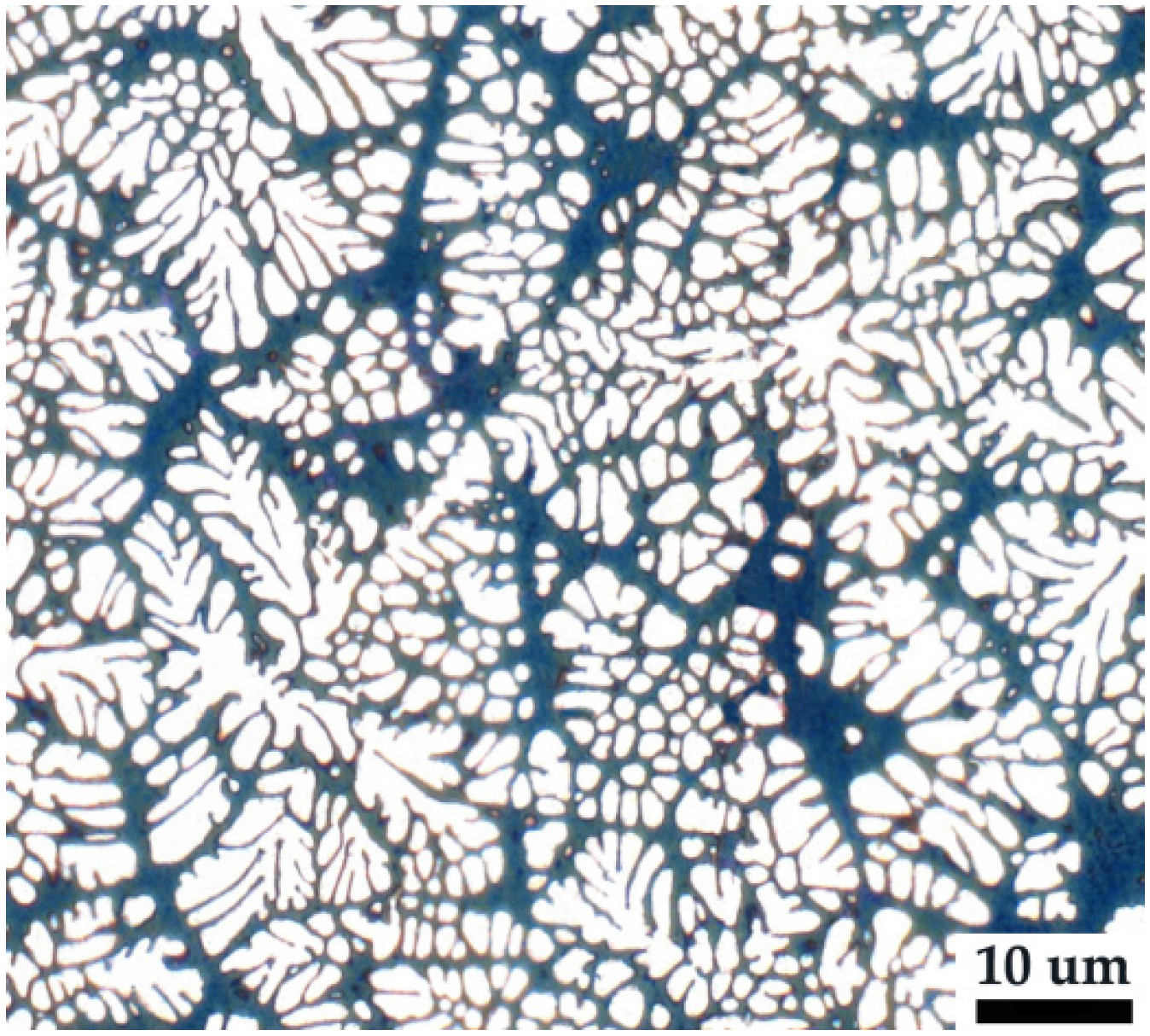

3.1. Microstructure of As-Cast Specimen

3.2. Microstructure of Annealed Specimens

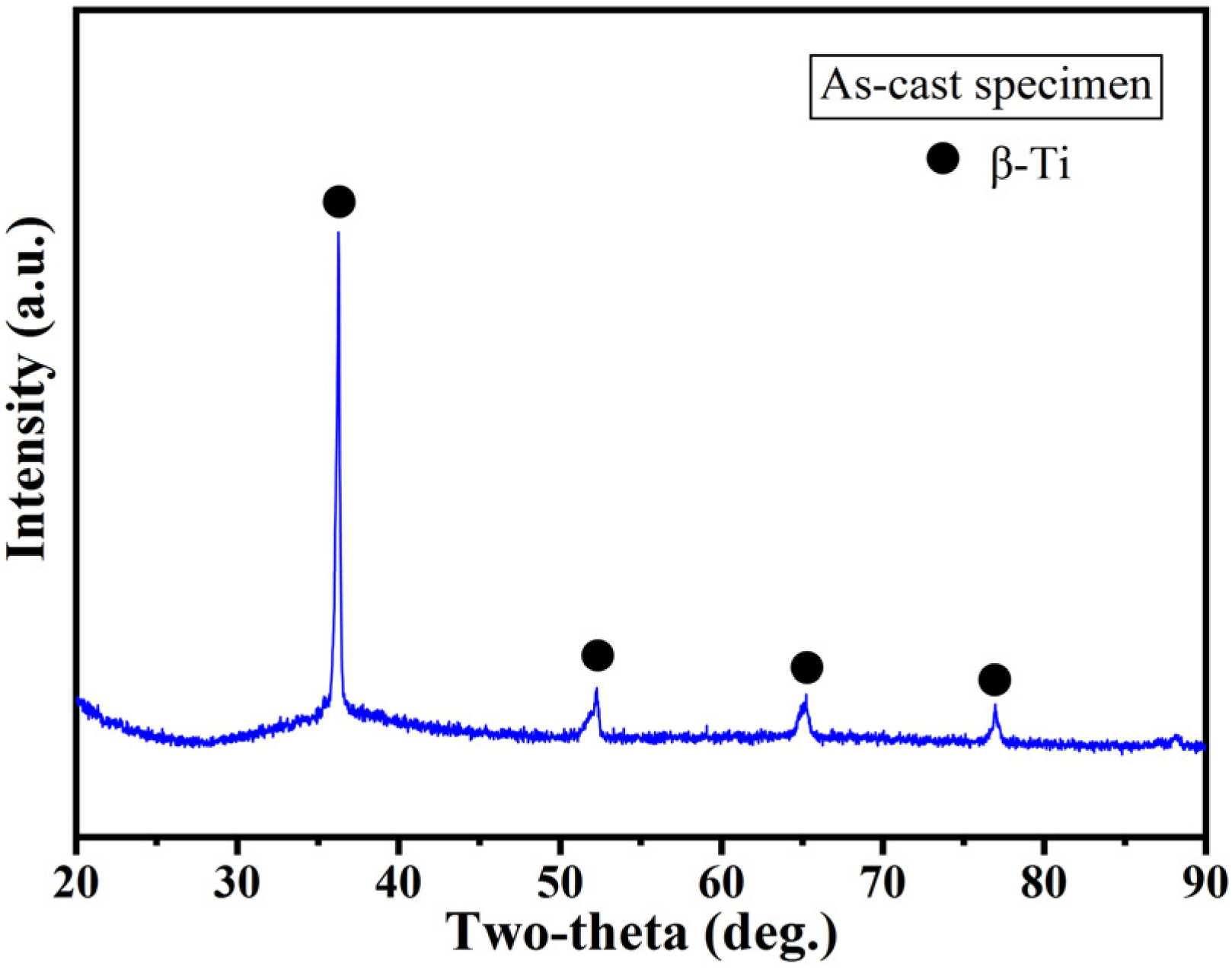

3.3. Phase Composition of As-Cast Specimens

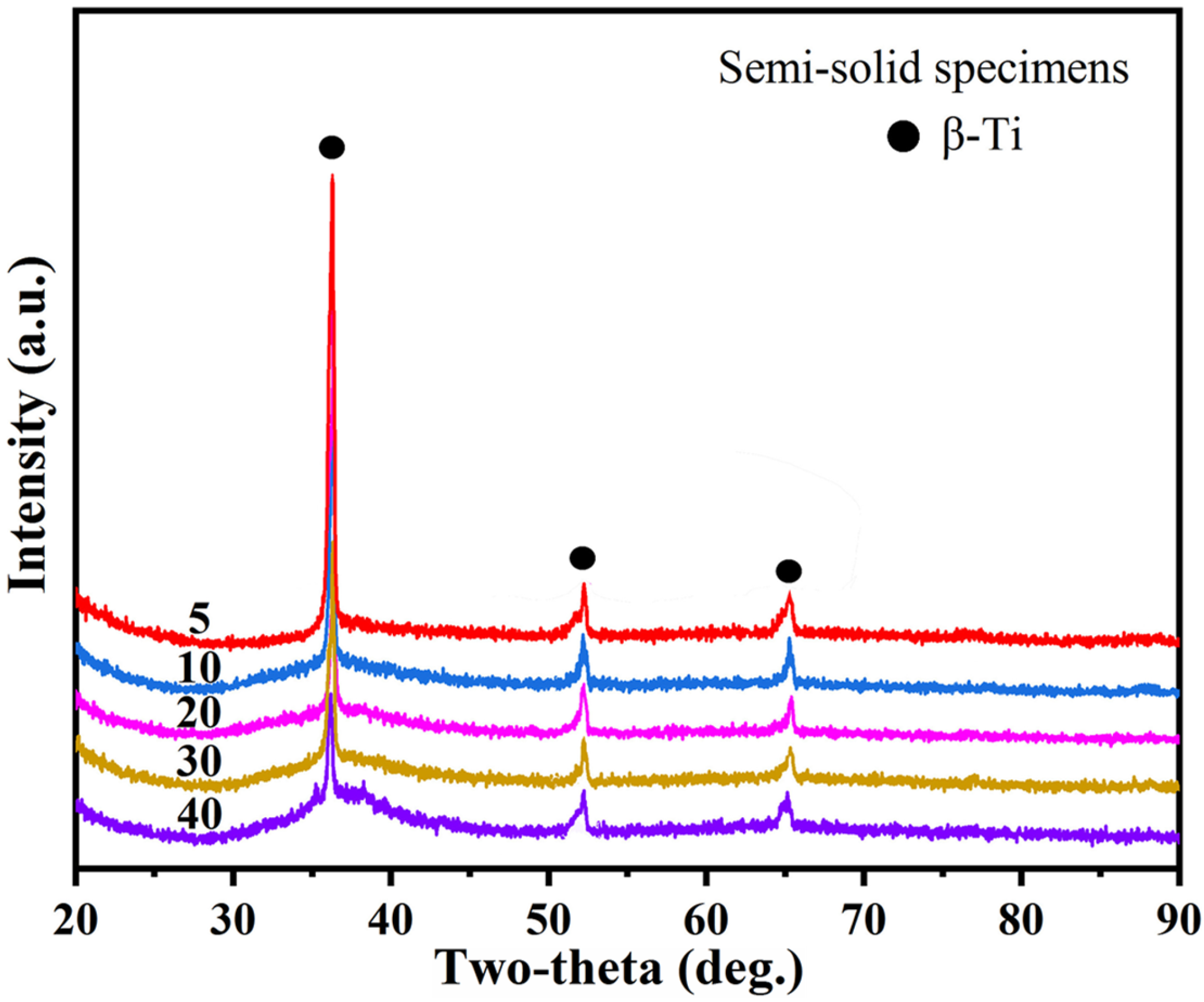

3.4. Phase Composition of Processed Specimens

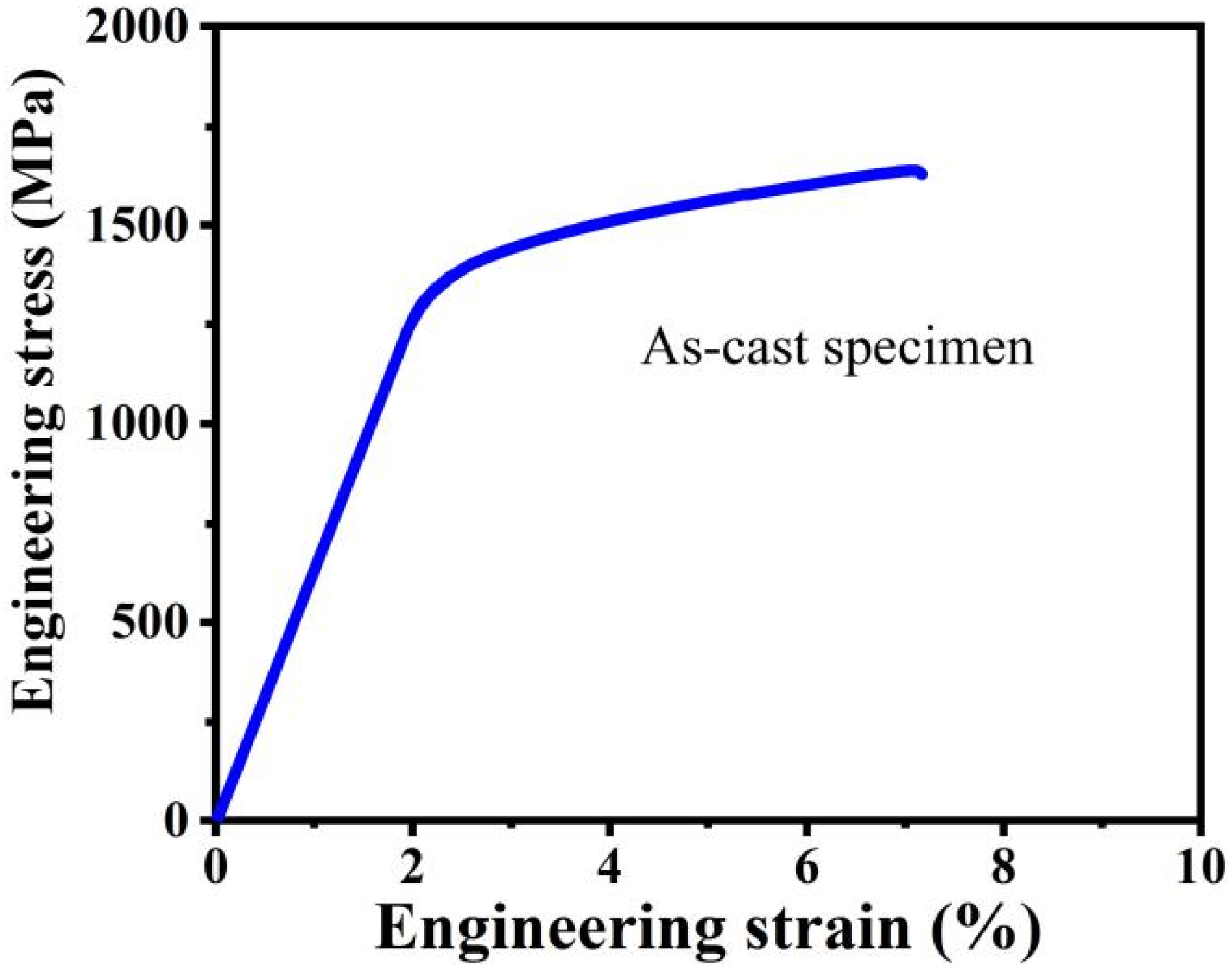

3.5. Mechanical Properties

3.6. Observation of Lateral Surface of Fractured Specimens

4. Discussion and Analysis

4.1. Crystal Evolution Process and Mechanism

4.2. Mechanism of Holding Time on Plasticity

5. Future Outlook

6. Conclusions

- ①

- The β-Ti dendrites of Ti48Zr27Cu6Nb5Be14 amorphous composites evolve into near-spherical/spherical crystals as the holding time increases from 5 to 40 min at 900 °C, with the average crystal size continuously rising to 23.1 μm and the crystal volume fraction gradually dropping.

- ②

- The plasticity of amorphous composites first increases to a maximum of 16.2% at 30 min then decreases to 12.5% at 40 min, while yield strength first falls to 1201 MPa at 30 min then rises, showing an opposite trend.

- ③

- As the treatment time extends, the crystal size gradually increases, and these crystals improve plasticity by increasing the number of shear bands. When treated for 40 min, the large-sized crystals also promote evolutionary behaviors of shear bands such as crossing, bending and deviation, further improving plasticity. However, the low crystal content causes the plasticity to decrease instead of increasing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, T.; Pang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, T. Corrosion resistant Cr-based bulk metallic glasses with high strength and hardness. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2015, 410, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.F.; Jiang, S.S.; Huang, Y.J.; Yin, H.B.C.; Sun, J.F.; Ngan, A.H.W. Elucidating how correlated operation of shear transformation zones leads to shear localization and fracture in metallic glasses: Tensile tests on CuZr based metallic-glass microwires, molecular dynamics simulations, and modelling. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 119, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Jiang, M.Q.; Dai, L.H. Dilatancy induced ductile–brittle transition of shear band in metallic glasses. Proc. R. Soc. A-Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2018, 474, 20170836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S.; Dai, C.; Mao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Han, G.; Wang, X. Effects of Ag and Co microalloying on glass-forming abilities and plasticity of Cu-Zr-Al based bulk metallic glasses. Mater Design 2022, 220, 110896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.C.; Hu, Y.J.; Chang, J.; Wang, H.P. Microscopic hardness and dynamic mechanical analysis of rapidly solidified Fe-based amorphous alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 861, 157957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.G.; Guo, H.B. Effects of annealing on structures and properties of Cu–Hf–Al amorphous thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 582, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Kaban, I.; Orava, J.; Cheng, Q.; Sun, Y.H.; Soldatov, I.; Nielsch, K. Phase-formation maps of CuZrAlCo metallic glass explored by in situ ultrafast techniques. Acta Mater. 2022, 241, 118371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, V.N.; Sokolov, A.P. Temperature dependence of structural relaxation in glass-forming liquids and polymers. Entropy 2022, 24, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-Uribe, A.; Reyes-Mayer, A.; Rodriguez, M.C.; Sarmiento-Bustos, E. On the influence of thermal annealing on molecular relaxations and structure in thermotropic liquid crystalline polymer. Polymer 2022, 240, 124506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradtmüller, H.; Gaddam, A.; Eckert, H.; Zanotto, E.D. Structural rearrangements during sub-Tg relaxation and nucleation in lithium disilicate glass revealed by a solid-state NMR and MD strategy. Acta Mater. 2022, 240, 118318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechers, B.; Das, A.; Dufresne, E.; Derlet, P.M.; Maaß, R. Intermittent cluster dynamics and temporal fractional diffusion in a bulk metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, Y.; Cao, Z.; Chen, H.; Bao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xie, C.X.; Ke, Y.B.; Zhou, Z.R.; Guo, J.W.; Sun, Z.Z.; et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Zr46Cu46Al8 bulk metallic glass after annealing treatment. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 621, 122636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, B.; Bontha, S.; Ramesh, M.R.; Krishna, M.; Balla, V.K. Solid state amorphization of Mg-Zn-Ca system via mechanical alloying and characterization. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017, 28, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimeroth, N.; Rohrer, J.; Albe, K. General purpose potential for glassy and crystalline phases of Cu-Zr alloys based on the ACE formalism. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 043602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, Q.; Tao, J.; Peng, Y.; Cai, T. Impact of polymer enrichment at the crystal–liquid interface on crystallization kinetics of amorphous solid dispersions. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Lück, R.; Lu, K.; Lavernia, E.J.; Rühle, M. Amorphous-to-crystalline transformation induced by thermal annealing of a metastable Al90Fe10 composite. Philos. Mag. A 2002, 82, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wu, X.; Dai, L.; Jiang, M. Comparative study of amorphous and crystalline Zr-based alloys in response to nanosecond pulse laser ablation. Acta Mech. Sin. 2002, 38, 221480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Kou, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, P. Phase separation and microstructure evolution of Zr48Cu36Ag8Al8 bulk metallic glass in the supercooled liquid region. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 2016, 45, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, S.; Hara, S.; Kumagai, T.; Sakai, S. Structural and mechanical properties of well-relaxed amorphous–crystal interface in silicon: Molecular dynamics study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2004, 31, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Yao, G.; Ge, Y.; Yue, X. Tunable rejuvenation behavior of Zr55Cu35Al10 metallic glass at the atomic scale during recovery annealing and pressure treatment. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tang, Z.; Kelton, K.F.; Liu, C.T.; Liaw, P.K.; Inoue, A.; Fan, C. Evolution of the atomic structure of a supercooled Zr55Cu35Al10 liquid. Intermetallics 2017, 82, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Song, W.; Shek, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Ritchie, R.O. Compressive ductility and fracture resistance in CuZr-based shape-memory metallic-glass composites. Int. J. Plast. 2020, 128, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Inoue, A.; Kong, F.L.; Zhu, S.L.; Stoica, M.; Kaban, I.; Eckert, J. Influence of ejection temperature on structure and glass transition behavior for Zr-based rapidly quenched disordered alloys. Acta Mater. 2016, 116, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.H.; Jiang, M.Q.; Liu, X.F.; Dai, L.H.; Li, J.X. In-situ observations on shear-banding process during tension of a Zr-based bulk metallic glass composite with dendrites. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2021, 565, 120841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, N.; Parrilli, A.; Jhabvala, J.; Neels, A.; Logé, R.E. Tensile and impact toughness properties of a Zr-based bulk metallic glass fabricated via laser powder-bed fusion. Materials 2021, 14, 5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Chen, Q.; Gao, J. Brittle-ductile transition in laser 3D printing of Fe-based bulk metallic glass composites. Metals 2019, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Wang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Ke, C.; Luo, J. Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties for oxygen-rich ZrTiAlV alloy during in-situ semi-solid processing. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 993, 174654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.P.; Bao, X.Q.; Jamili-Shirvan, Z.; Jin, J.S.; Deng, L.; Yao, K.F.; Gong, P.; Wang, X.Y. Enhancing strength-ductility synergy in an ex situ Zr-based metallic glass composite via nanocrystal formation within high-entropy alloy particles. Mater. Design 2021, 210, 110108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.C.; Wang, H.P. Phase selection and characterization of Fe-based multi-component amorphous composite. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 839, 142840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Song, L.J.; Huo, J.T.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Y. Designing advanced amorphous/nanocrystalline alloys by controlling the energy state. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2311406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.C.; Suh, J.Y.; Wiest, A.; Lind, M.L.; Demetriou, M.D.; Johnson, W.L. Development of tough, low-density titanium-based bulk metallic glass matrix composites with tensile ductility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Su, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y. In situ high-energy X-Ray diffraction studies of deformation-induced phase transformation in Ti-based amorphous alloy composites containing ductile dendrites. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 5008–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Han, W.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhai, H.; Bhardwaj, V.; Wang, H. Enhancing the plasticity of a Ti-based bulk metallic glass composite by cryogenic cycling treatments. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 835, 155247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, M. Microstructure evolution during dendrite coarsening in an isothermal environment: 3-D cellular automaton modeling and experiments. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 10393–10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Tang, C.; Zhao, X.; Ding, Y.; Ma, L.; Shen, X. Effect of isothermal annealing on mechanical performance and corrosion resistance of Ni-free Zr59Ti6Cu17.5Fe10Al7.5 bulk metallic glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 537, 120013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.Y.; Li, P.; Chen, W.; Song, X.D. Spheroidization behavior of dendritic bcc phase in Zr-based β-phase composite. China Foundry 2013, 10, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Flores, K.M. Spherulitic crystallization behavior of a metallic glass at high heating rates. Intermetallics 2011, 19, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimens | Yield Strength σy/MPa | Plasticity εp/% | Maximum Strength σmax/MPa |

|---|---|---|---|

| As-cast | 1372 | 4.9 | 1641 |

| 5 | 1309 | 9.3 | 1645 |

| 10 | 1264 | 11.6 | 1611 |

| 20 | 1235 | 13.9 | 1695 |

| 30 | 1201 | 16.2 | 1580 |

| 40 | 1325 | 12.5 | 1498 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, B.; Wei, C.; Zhao, J.; Wu, L.; Li, Q.; Ouyang, Y. Analysis of the Regulatory Effect of Semi-Solid Isothermal Treatment Time on Crystallization and Plasticity of Amorphous Composites. Metals 2025, 15, 1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121363

Huang X, Wang G, Chen B, Wei C, Zhao J, Wu L, Li Q, Ouyang Y. Analysis of the Regulatory Effect of Semi-Solid Isothermal Treatment Time on Crystallization and Plasticity of Amorphous Composites. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121363

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Xinhua, Guang Wang, Bin Chen, Chenghao Wei, Jintao Zhao, Longguang Wu, Qi Li, and Yuejun Ouyang. 2025. "Analysis of the Regulatory Effect of Semi-Solid Isothermal Treatment Time on Crystallization and Plasticity of Amorphous Composites" Metals 15, no. 12: 1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121363

APA StyleHuang, X., Wang, G., Chen, B., Wei, C., Zhao, J., Wu, L., Li, Q., & Ouyang, Y. (2025). Analysis of the Regulatory Effect of Semi-Solid Isothermal Treatment Time on Crystallization and Plasticity of Amorphous Composites. Metals, 15(12), 1363. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121363