Effect of Quenching and Partitioning on Microstructure, Impact Toughness and Wear Resistance of a Gray Cast Iron

Abstract

1. Introduction

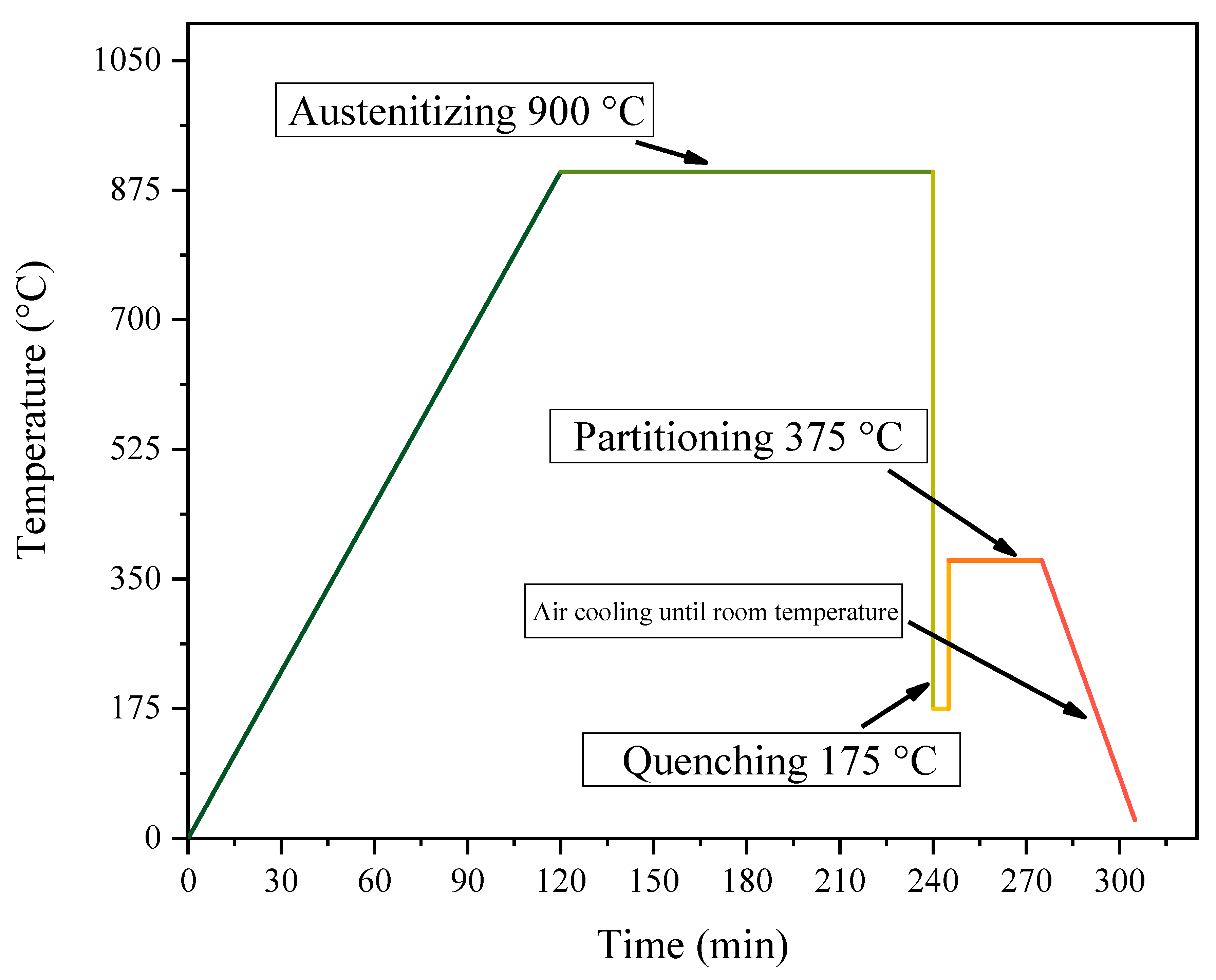

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microstructural Characterization

2.2. Mechanical Testing

2.3. Tribological Testing

3. Results and Discussion Influence of Partitioning Time

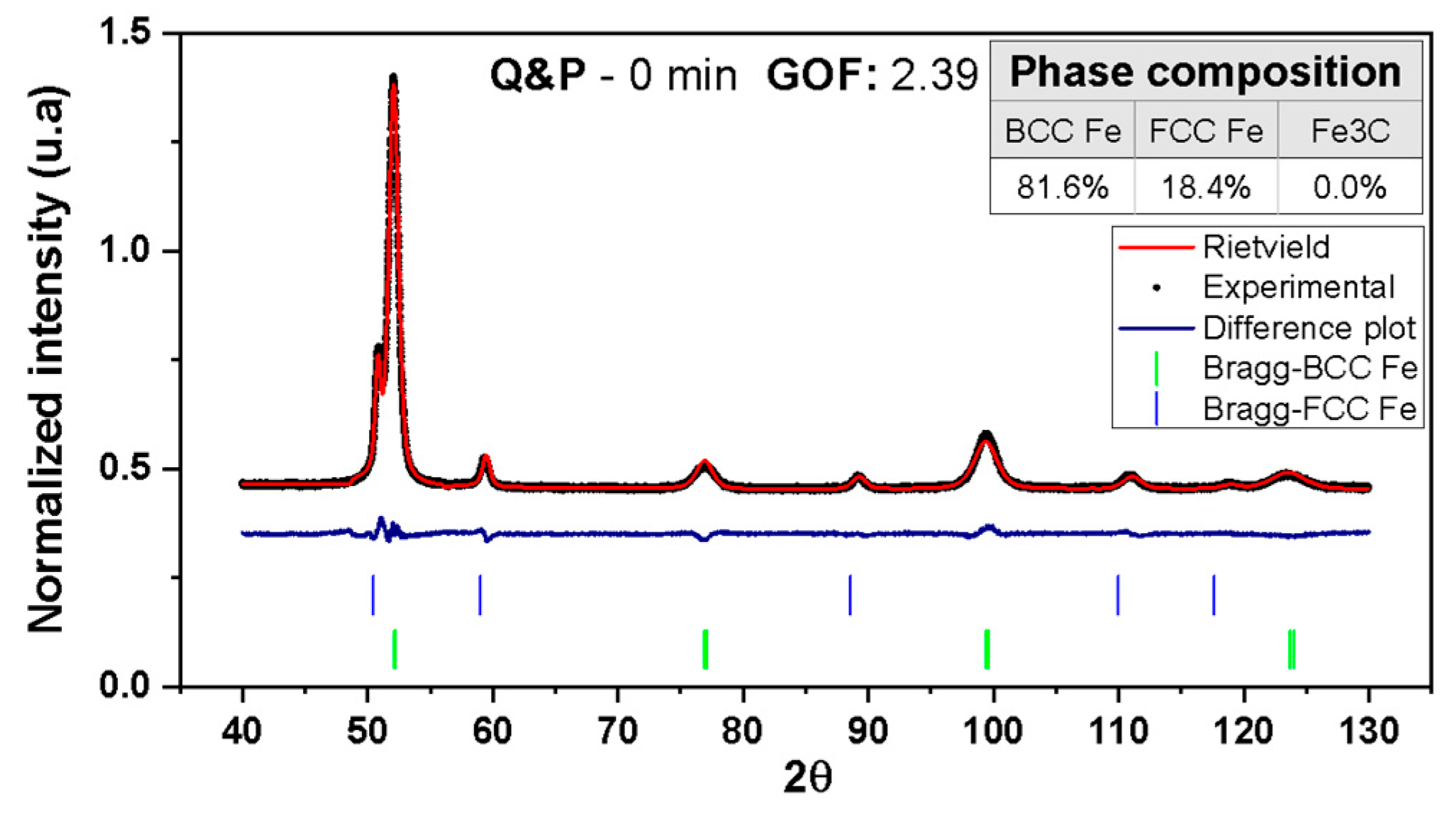

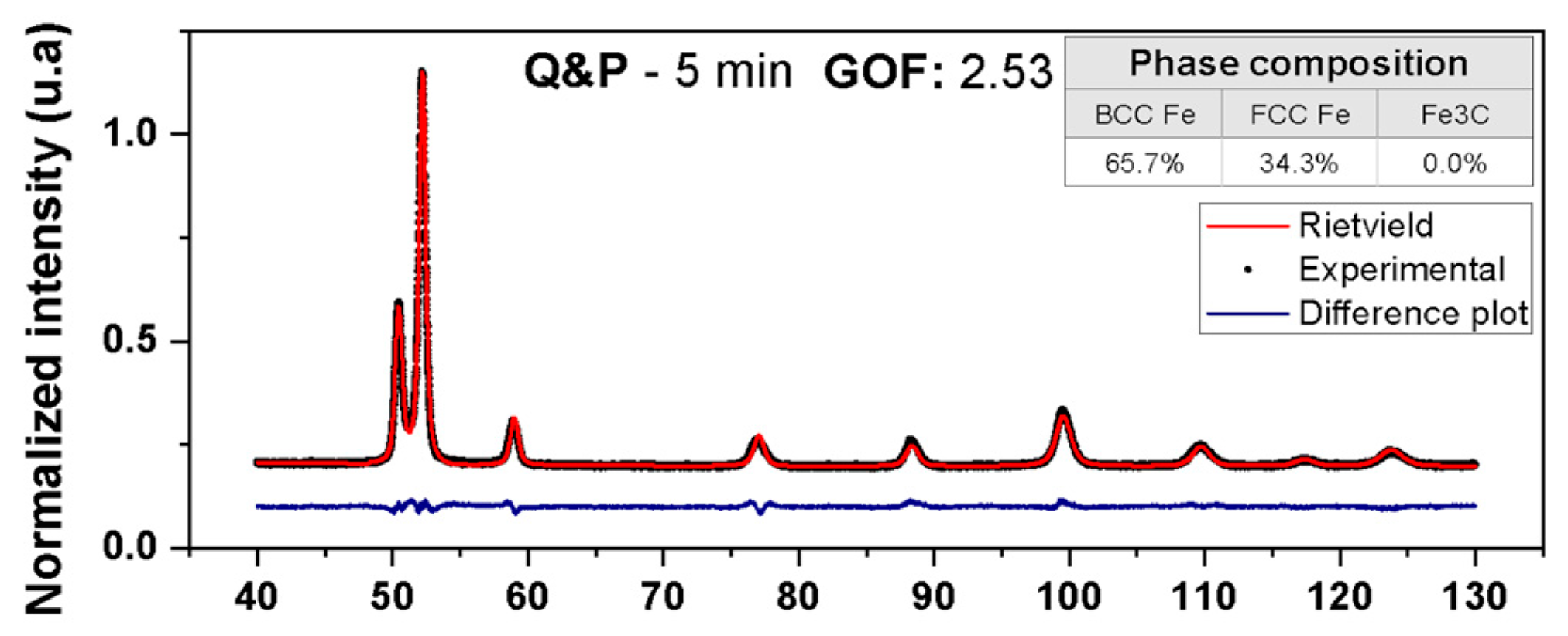

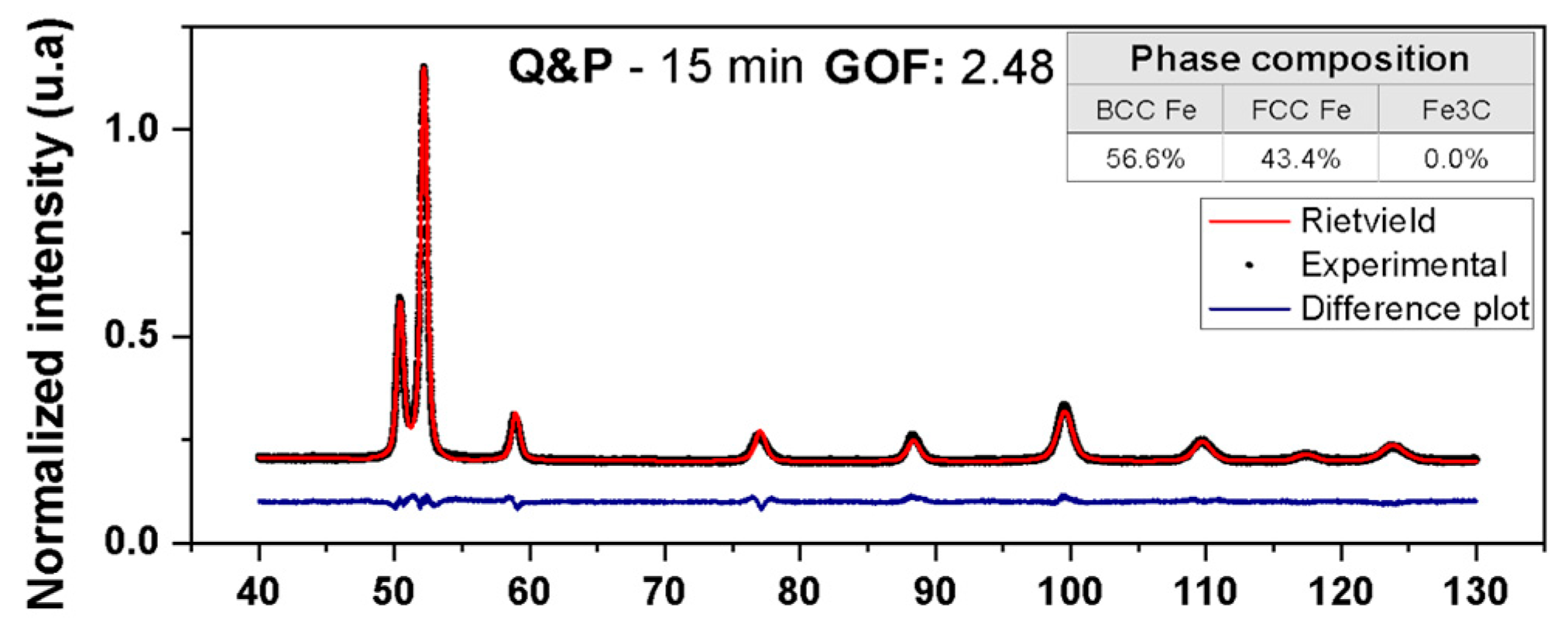

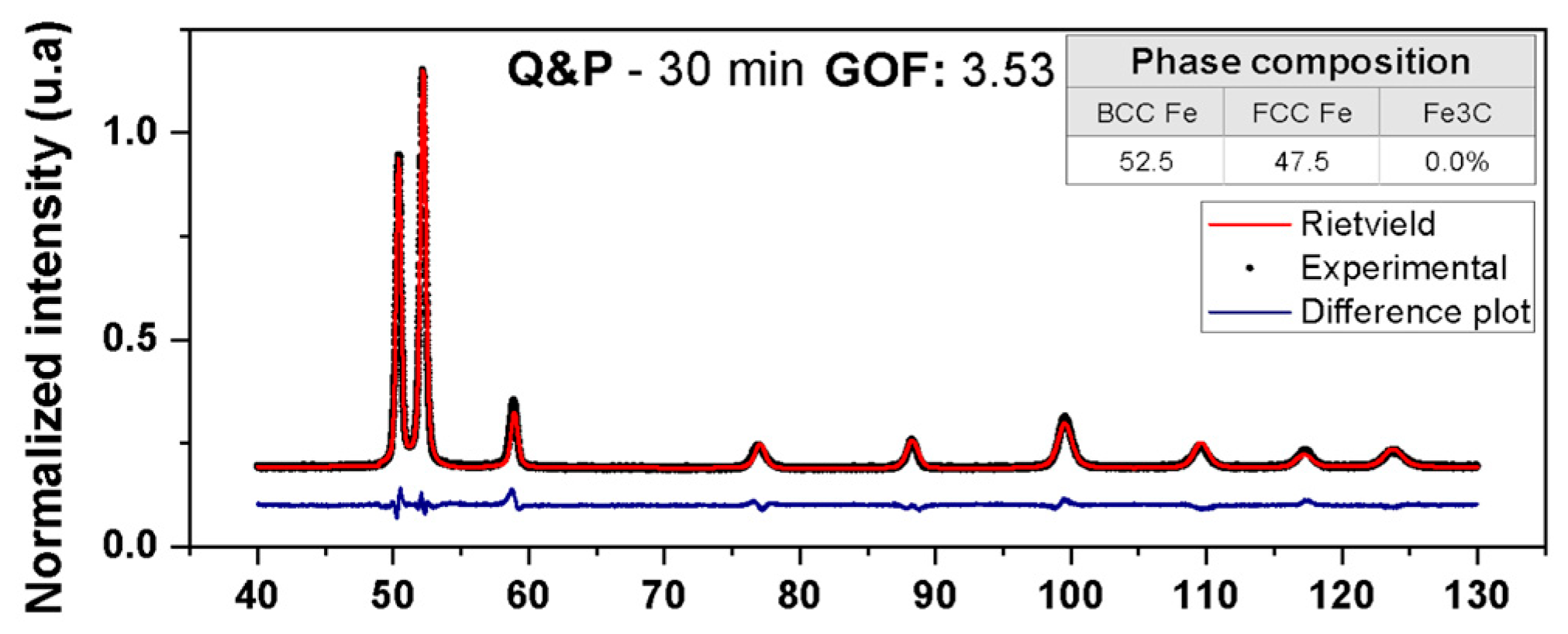

3.1. Influence of the Partitioning Time

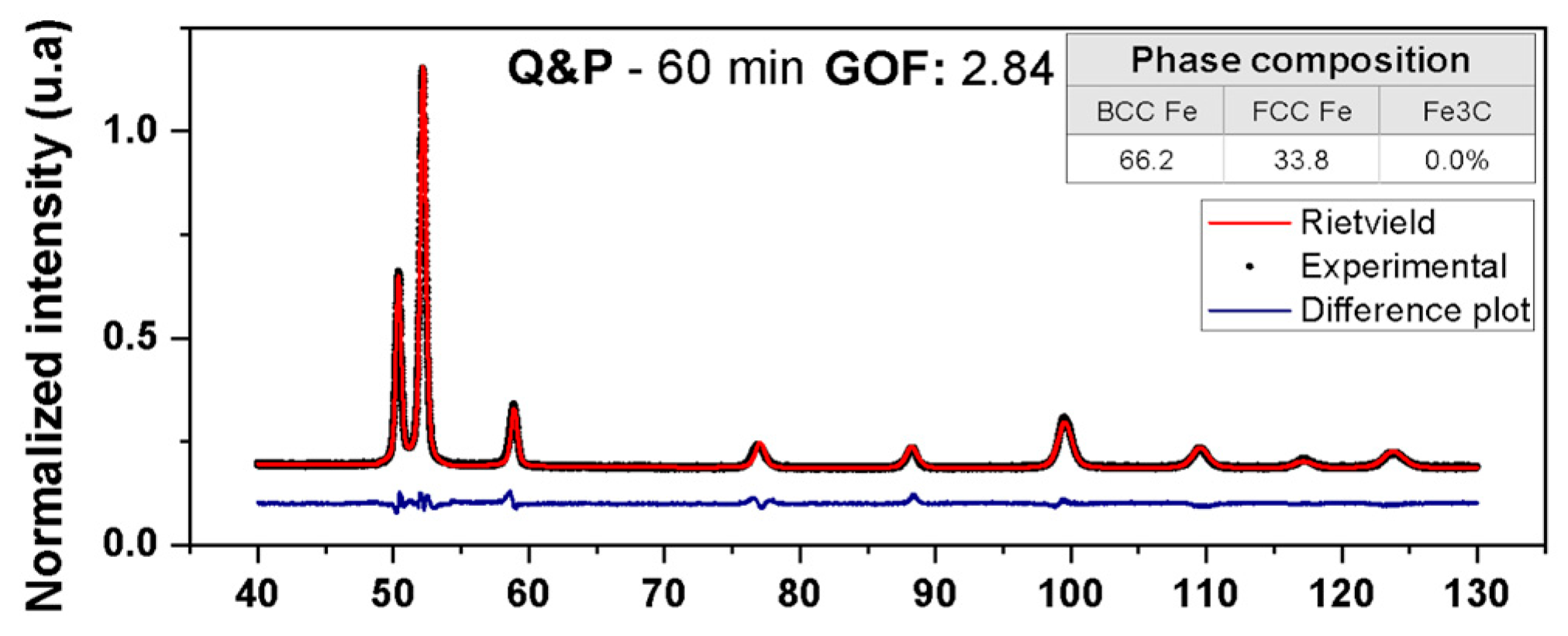

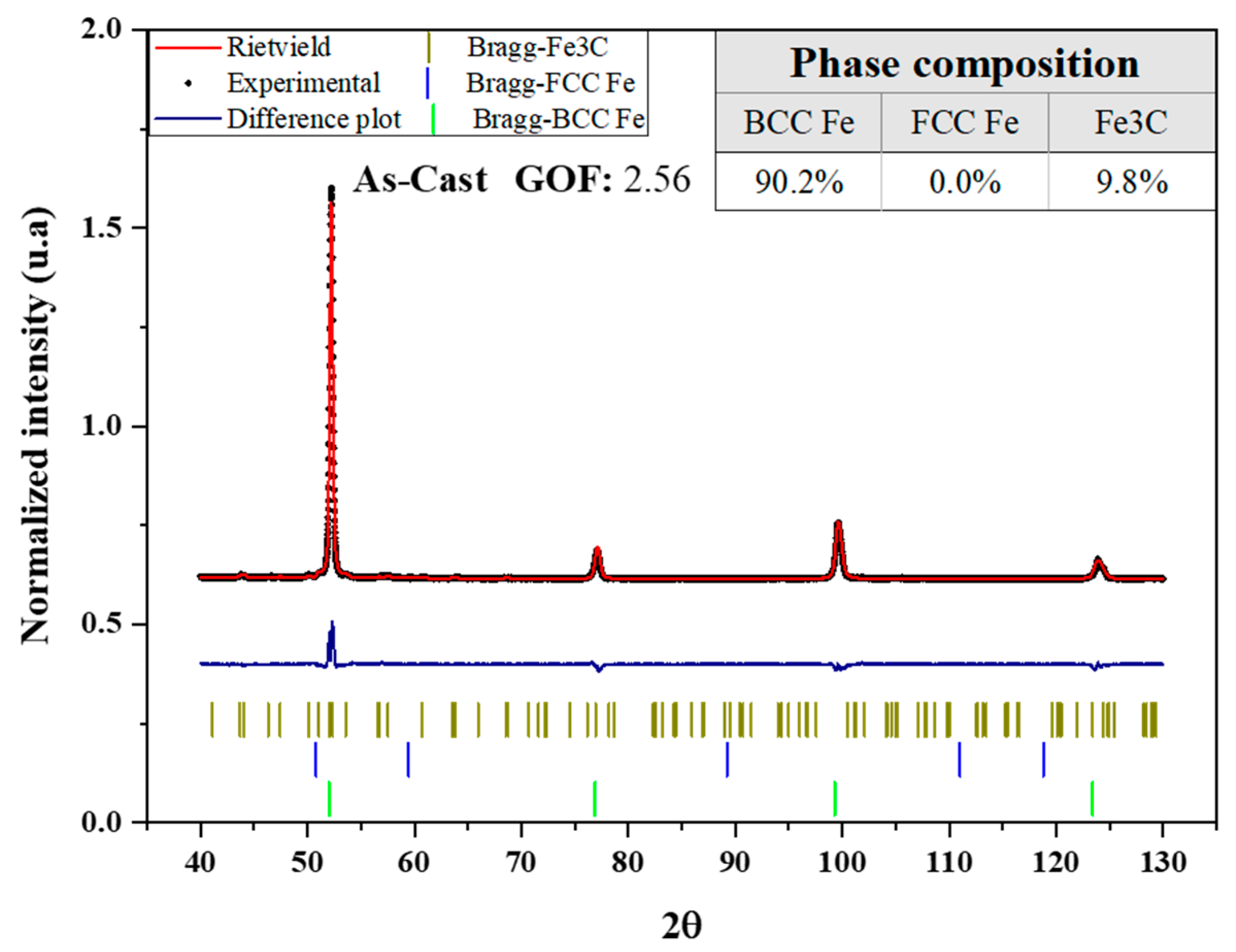

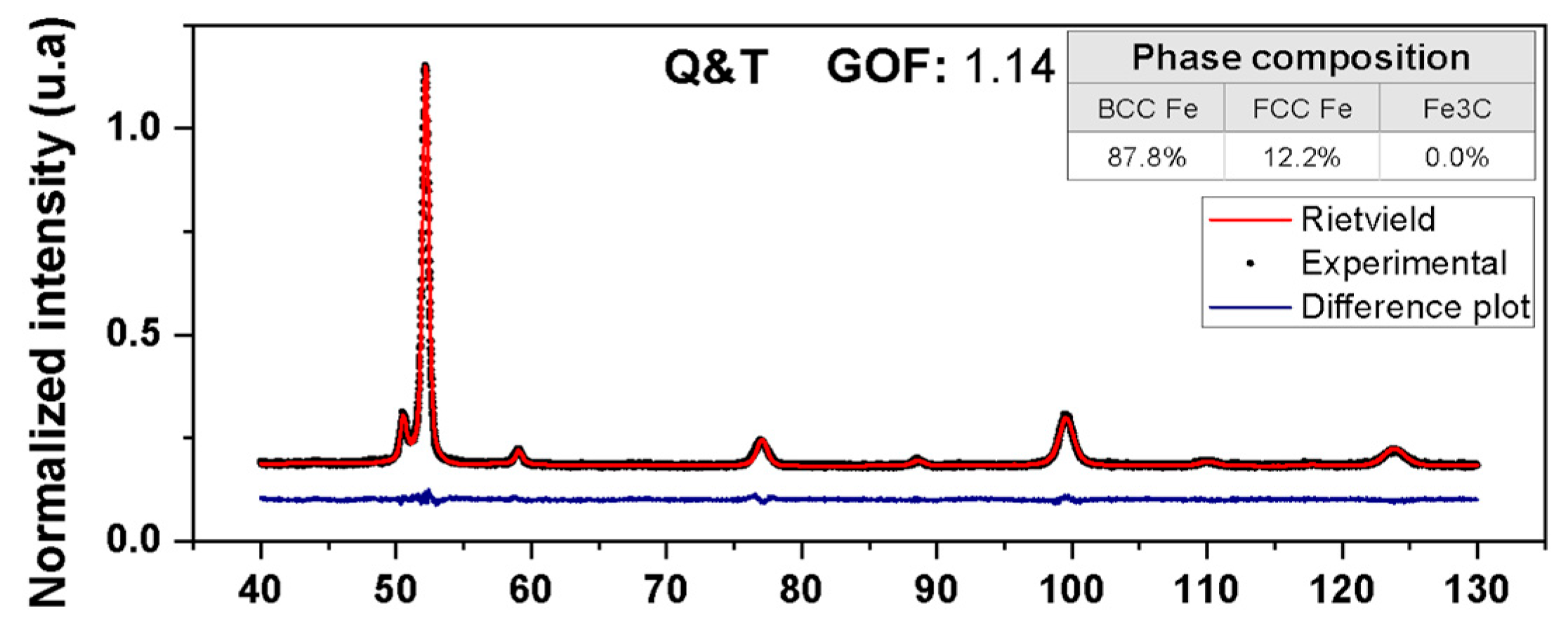

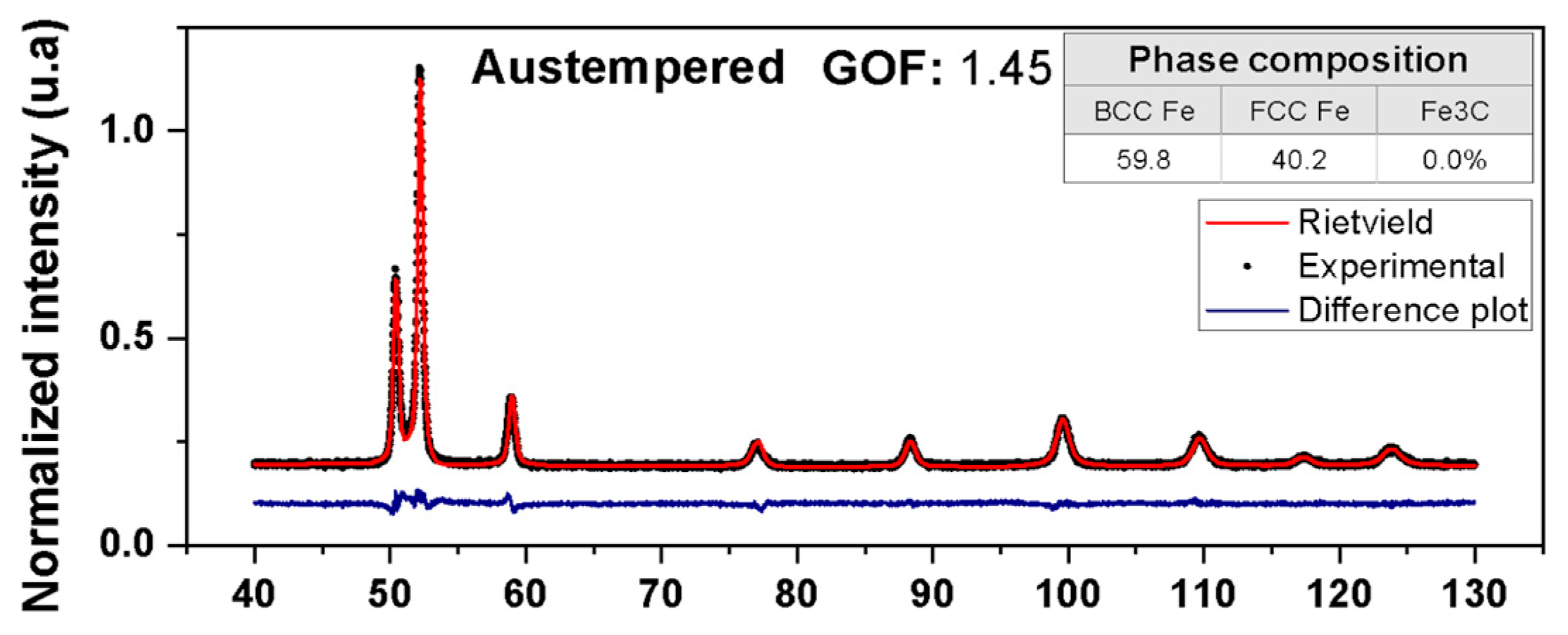

3.2. Microstructural Comparison with Other Heat Treatments

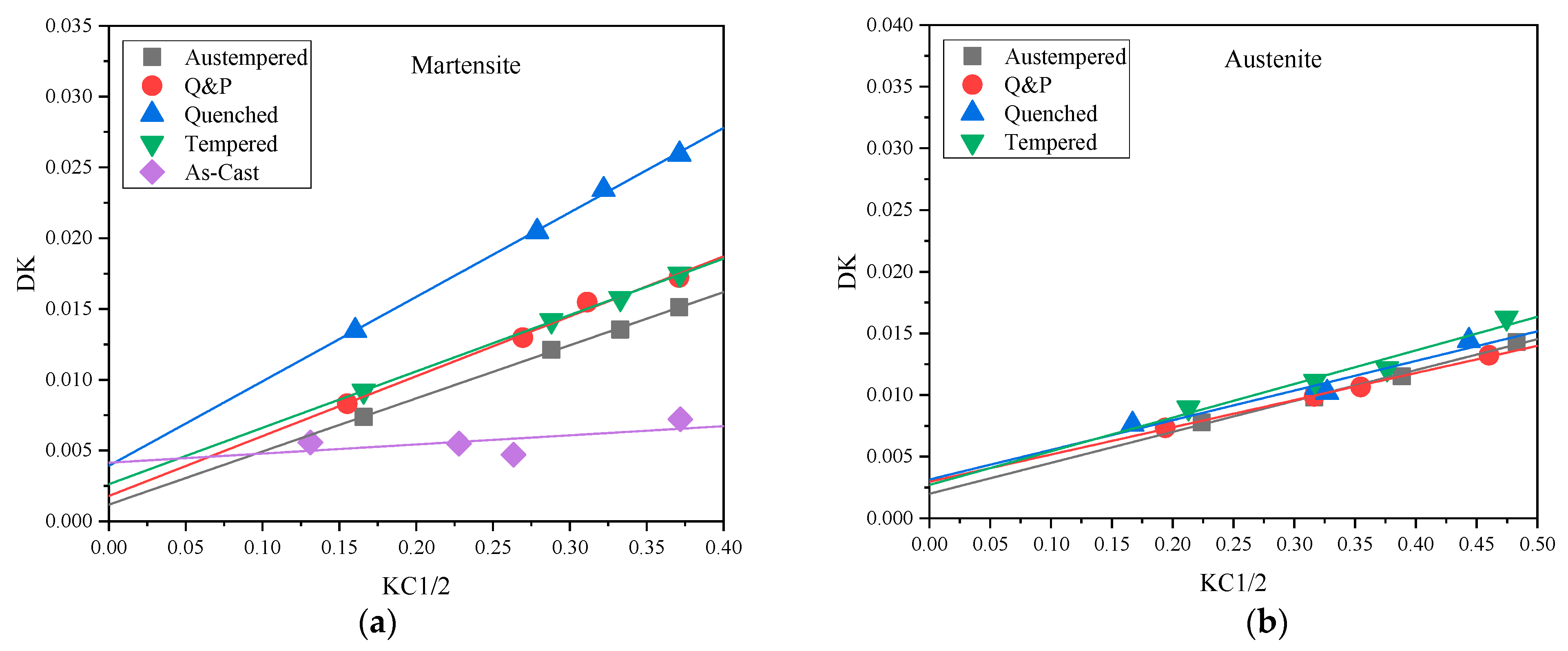

3.3. Effect of the Heat Treatments on Impact Toughness and Wear Resistance

4. Conclusions

- Microstructure and Carbon Partitioning: Q&P treatment significantly increases the fraction of retained austenite, with 30 min of partitioning yielding the highest fraction (~45.7%). Carbon rapidly diffuses into the retained austenite, stabilizing it at room temperature and promoting a microstructure composed of partitioned martensite, bainite ferrite and carbon-enriched austenite.

- Mechanical Properties: Q&P provides a good balance between hardness and toughness, with the highest Charpy impact energy (14.6 J) among all heat-treated samples. Austempered samples exhibit similar toughness, while quenched-only and quenched-and-tempered conditions show lower energy absorption.

- Wear Resistance: Quenched and tempered samples exhibit the highest wear resistance due to their elevated hardness, while Q&P and austempered materials show slightly lower wear resistance, influenced by plastic deformation of retained austenite and tribofilm formation.

- Implications: Q&P represents a promising approach for developing multiphase gray cast irons with enhanced impact toughness while retaining hardness. Optimization of partitioning parameters could further improve tribological performance, making Q&P-treated GG25 suitable for components subjected to impact and wear loading.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- American Society for Metals. Metals Handbook, Volume 1: Properties and Selection—Irons, Steels, and High-Performance Alloys; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Moonesan, M.; Raouf, A.H.; Madah, F.; Zadeh, A.H. Effect of alloying elements on thermal shock resistance of gray cast iron. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 520, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, M.M.J.; Davami, P.; Varahram, N. Effect of cooling rate on microstructure and mechanical properties of gray cast iron. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 528, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, T. The key role of applied university education in poverty alleviation by e-commerce: A case study of Rural Taobao in China. In Proceedings of the ICEIT 2019 8th International Conference on Educational and Information Technology, Cambridge, UK, 2–4 March 2019; pp. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J.D.; Sorondo, S.; Li, B.; Qin, H.; Rivero, I.V. Mechanical behavior of bimetallic stainless steel and gray cast iron repairs via directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 85, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.; Zanocco, M.; Rondinella, A.; Iodice, V.; Sin, A.; Fedrizzi, L.; Andreatta, F. Inhibitive effect of 8-hydroxyquinoline on corrosion of gray cast iron in automotive braking systems. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 449, 142221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.D.; Sorondo, S.; Greeley, A.; Zhang, X.; Cormier, D.; Li, B.; Qin, H.; Rivero, I.V. Property-structure-process relationships in dissimilar material repair with directed energy deposition: Repairing gray cast iron using stainless steel 316L. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 81, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xue, Z.; Song, S.; Cromarty, R.; Zhou, X. Evolution of microstructure and high temperature tensile strength of gray cast iron HT250: The role of molybdenum. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 863, 144511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ma, J.; Lai, D.; Zhanh, J.; Li, W.; Li, S.; He, S. Multi-response optimization of process parameters in nitrogen-containing gray cast iron milling process based on application of non-dominated ranking genetic algorithm. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balachandran, G.; Vadiraj, A.; Kamaraj, M.; Kazuya, E. Mechanical and wear behavior of alloyed gray cast iron in the quenched and tempered and austempered conditions. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 4042–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Barber, G.C.; Qiu, F.; Hu, M. Wear behavior of composite strengthened gray cast iron by austempering and laser hardening treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2037–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mesa, C.H.; Gómez-Botero, M.; Montoya-Mejía, M.; Ríos-Diez, O.; Aristizábal-Sierra, R. Wear resistance of austempered grey iron under dry and wet conditions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 21, 4174–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, S.B. Microstructure–property relationship in the quenching and partitioning (Q&P) steel. Mater. Charact. 2023, 196, 112561. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wu, R.; Song, S.-P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T. Influence of changes in alloying elements distribution and retained austenite (RA) on mechanical properties of high boron alloy during quenching and partitioning (Q&P) process. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 4748–4761. [Google Scholar]

- Mohtadi-Bonab, M.A.; Ariza, E.A.; Loureiro, R.C.; Centeno, D.; Carvalho, F.M.; Avila, J.A.; Masoumi, M. Improvement of tensile properties by controlling the microstructure and crystallographic data in commercial pearlitic carbon–silicon steel via quenching and partitioning (Q&P) process. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 845–858. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, J.; Matlock, D.K.; De Cooman, B.C.; Schroth, J.G. Carbon partitioning into austenite after martensite transformation. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 2611–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, J.G.; Assunção, F.C.R.; Matlock, D.K.; Edmonds, D.V. The “Quenching and Partitioning” process: Background and recent progress. Mater. Res. 2005, 8, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.J.S.T.; Goldenstein, H.; Guesser, W.; de Campos, M.F. Quenching and partitioning heat treatment in ductile cast irons. Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melado, A.C.; Nishikawa, A.S.; Goldenstein, H.; Giles, M.A.; Reed, P.A.S. Effect of microstructure on fatigue behaviour of advanced high strength ductile cast iron produced by quenching and partitioning process. Int. J. Fatigue 2017, 104, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungár, T.; Borbély, A. The effect of dislocation contrast on X-ray line broadening: A new approach to line profile analysis. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 69, 3173–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungár, T.; Dragomir, I.; Révész, Á.; Borbély, A. The contrast factors of dislocations in cubic crystals: The dislocation model of strain anisotropy in practice. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E23-16; Standard Test Methods for Notched Bar Impact Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- ASTM G99-23; Standard Test Method for Wear and Friction Testing with a Pin-on-Disk or Ball-on-Disk Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM A247-19; Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Microstructure of Graphite in Iron Castings. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Bugten, A.; Michels, L.; Mathiesen, R.; Bjørge, R.; Chernyshov, D.; McMonagle, C.; van Beek, W.; Pires, A.; Simões, S.; Ribeiro, C.; et al. Influence of B and Cu on microstructure and eutectoid transformation kinetics in spheroidal graphite cast iron. Materialia 2025, 43, 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, D.J.; Holmes, J.B. Effect of alloying additions on lattice parameter of austenite. J. Iron Steel Inst. 1970, 208, 469–470. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnhoff, G.; Findley, K.; De Cooman, B. The influence of silicon and aluminum alloying on the lattice parameter and stacking fault energy of austenitic steel. Scr. Mater. 2014, 92, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onink, M.; Brakman, C.; Tichelaar, F.; Mittemeijer, E.; van der Zwaag, S.; Root, J.; Konyer, N. The lattice parameters of austenite and ferrite in Fe–C alloys as functions of carbon concentration and temperature. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1993, 29, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Chen, G.; Xiang, G. Calculation of carbon content of austenite during heat treatment of cast irons. China Foundry 2010, 7, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, A.S.; Miyamoto, G.; Furuhara, T.; Tschiptschin, A.P.; Goldenstein, H. Phase transformation mechanisms during quenching and partitioning of a ductile cast iron. Acta Mater. 2019, 179, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, A.S.; Santofimia, M.J.; Sietsma, J.; Goldenstein, H. Influence of bainite reaction on the kinetics of carbon redistribution during the quenching and partitioning process. Acta Mater. 2018, 142, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilnyk, K.; Suzuki, P.; Sandim, H. Subtle microstructural changes during prolonged annealing of ODS-Eurofer steel. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 35, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, W.; Hu, F.; Yershov, S.; Wu, K. The role of Si in enhancing the stability of residual austenite and mechanical properties of a medium carbon bainitic steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Song, R.; Feng, Y.; Xu, J. Influence of martensite and bainite microstructure on local mechanical properties of a bainitic and martensitic multiphase cast steel. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 4517–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinribide, O.J.; Ogundare, O.D.; Oluwafemi, O.M.; Ebisike, K.; Nageri, A.K.; Akinwamide, S.O.; Gamaoun, F.; Olubambi, P.A. A review on heat treatment of cast iron: Phase evolution and mechanical characterization. Materials 2022, 15, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GG 25 Gray Cast Iron—Composition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Element | Average (wt.%) | Deviation |

| Fe | Bal. | |

| C | 3.55 | 0.01 |

| Mn | 0.64 | 0.03 |

| Si | 2.09 | 0.06 |

| P | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| S | 0.095 | 0.02 |

| Cr | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Cu | 0.325 | 0.045 |

| Sample | q | Crystallite Size (nm) | Microdeformation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC | FCC | BCC | FCC | BCC | FCC | |

| 0 min | 2.4 | 1.7 | 187 | 198 | 0.067 | 0.026 |

| 5 min | 2.5 | 1.7 | 347 | 478 | 0.044 | 0.035 |

| 15 min | 2.6 | 1.7 | 437 | 406 | 0.043 | 0.027 |

| 30 min | 2.6 | 1.7 | 477 | 303 | 0.041 | 0.022 |

| 45 min | 2.5 | 1.7 | 540 | 354 | 0.042 | 0.022 |

| 60 min | 2.3 | 1.7 | 431 | 356 | 0.037 | 0.023 |

| 90 min | 2.6 | 1.7 | 455 | 410 | 0.039 | 0.022 |

| Sample | q | Crystallite Size (nm) | Microdeformation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | γ | α | γ | α | γ | |

| As-Cast | 2.8 | - | 218 | - | 0.006 | - |

| As-Quenched | 2.5 | 1.9 | 225 | 286 | 0.059 | 0.024 |

| Q&T | 2.4 | 1.7 | 350 | 332 | 0.040 | 0.027 |

| Austempered | 2.4 | 1.7 | 800 | 451 | 0.038 | 0.025 |

| 30 min Q&P | 2.6 | 1.7 | 477 | 303 | 0.041 | 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva Junior, E.L.d.; Mariani, F.E.; Vurobi Junior, S.; Konno, C.Y.N.; Corrêa Batista, A.; Santos, T.M.d.O.; Barbosa, M.B.; Zilnyk, K.D. Effect of Quenching and Partitioning on Microstructure, Impact Toughness and Wear Resistance of a Gray Cast Iron. Metals 2025, 15, 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121361

Silva Junior ELd, Mariani FE, Vurobi Junior S, Konno CYN, Corrêa Batista A, Santos TMdO, Barbosa MB, Zilnyk KD. Effect of Quenching and Partitioning on Microstructure, Impact Toughness and Wear Resistance of a Gray Cast Iron. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121361

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva Junior, Edson Luiz da, Fábio Edson Mariani, Selauco Vurobi Junior, Camila Yuri Negrão Konno, Adriano Corrêa Batista, Tiago Manoel de Oliveira Santos, Mariana Botelho Barbosa, and Kahl Dick Zilnyk. 2025. "Effect of Quenching and Partitioning on Microstructure, Impact Toughness and Wear Resistance of a Gray Cast Iron" Metals 15, no. 12: 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121361

APA StyleSilva Junior, E. L. d., Mariani, F. E., Vurobi Junior, S., Konno, C. Y. N., Corrêa Batista, A., Santos, T. M. d. O., Barbosa, M. B., & Zilnyk, K. D. (2025). Effect of Quenching and Partitioning on Microstructure, Impact Toughness and Wear Resistance of a Gray Cast Iron. Metals, 15(12), 1361. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121361