Abstract

Artificial intelligence is often framed as a neutral technical tool that enhances efficiency and consistency in institutional decision-making. This article challenges that framing by showing that automated systems now operate as social and institutional actors that reshape recognition, opportunity, and public trust in everyday life. Focusing on employment screening, welfare administration, and digital platforms, the study examines how algorithmic systems mediate social relations and reorganise how individuals are evaluated, classified, and legitimised. Drawing on regulatory and policy materials, platform governance documents, technical disclosures, and composite vignettes synthesised from publicly documented evidence, the article analyses how automated judgement acquires institutional authority. It advances three core contributions. First, it develops a sociological framework explaining how delegated authority, automated classification, and procedural opacity transform institutional power and individual standing. Second, it demonstrates a dual logic of inequality: automated systems both reproduce historical disadvantage through patterned data and generate new forms of exclusion through data abstraction and optimisation practices that detach individuals from familiar legal, social, and moral categories. Third, it shows that automation destabilises procedural justice by eroding relational recognition, producing trust deficits that cannot be resolved through technical fairness or explainability alone. The findings reveal that automated systems do not merely support institutional decisions; they redefine how institutions perceive individuals and how individuals interpret institutional legitimacy. The article concludes by outlining governance reforms aimed at restoring intelligibility, accountability, inclusion, and trust in an era where automated judgement increasingly structures social opportunity and public authority.

1. Introduction: Everyday Encounters with Automated Judgement

Across many ordinary decisions, people increasingly find themselves responding to outcomes produced by systems rather than by other human beings. A job applicant is removed from a shortlist before anyone reads their application. A family seeking social support receives an automated denial with no explanation. A content creator watches their audience disappear overnight without knowing what rule was applied. These experiences may feel isolated or personal, yet together they reflect a wider shift in how institutions classify, recognise, and act upon individuals. Automated systems have become routine intermediaries of social life, shaping access to opportunity, structuring visibility, and influencing whose claims or aspirations are treated as legitimate.

Early scholarship often framed automation as an efficiency upgrade. Automated systems were presented as tools capable of reducing human inconsistency and improving procedural regularity, particularly in complex urban governance and administrative settings [1]. From this perspective, automation appeared as a continuation of bureaucratic rationalisation. However, research in platform governance and digital labour reveals a more complicated reality. Rather than merely applying rules, automated systems actively shape who becomes visible, influential, or marginal within digital and institutional environments [2,3]. At the same time, studies in organisational and AI governance show that assumptions embedded at the design stage frequently acquire institutional authority long before systems are deployed, embedding power into technical infrastructures that remain largely unexamined [4,5]. These findings challenge the idea that automated systems are neutral extensions of existing procedures. Instead, they suggest that such systems increasingly operate as institutional actors in their own right.

A persistent tension follows from this shift. On one hand, experimental research shows that administrators and citizens often interpret algorithmic decisions as objective or impartial, even when they cannot access the reasoning behind them [6]. On the other hand, studies of digital platforms and welfare systems show that many individuals experience automated outcomes as arbitrary, exclusionary, or unjust precisely because the rules remain opaque and unchallengeable [2,3,7]. This tension raises a sociological question that technical AI ethics debates do not fully resolve: why do automated systems continue to command authority while simultaneously producing feelings of misrecognition, alienation, and distrust?

Much existing AI research focuses on technical solutions such as bias mitigation, fairness optimisation, explainable AI, and auditing mechanisms. These approaches are valuable and can improve decision accuracy and transparency. However, this article advances a complementary claim: even systems that are technically fair or explainable can still produce social and relational harm. The central argument is that automated judgement reshapes not only outcomes, but also the relationship between individuals and the institutions that evaluate them. In doing so, it alters how recognition, legitimacy, and trust are experienced in everyday institutional encounters.

This study examines how algorithmic systems reorganise three interrelated dimensions of social life. The first is social relations, understood as how individuals experience institutional recognition or disregard. The second is opportunity, shaped by automated sorting in employment, welfare administration, and digital participation. The third is public trust, particularly in contexts where decisions appear final even though the reasoning remains inaccessible.

To explore these dynamics, the article adopts a multi-source interpretive design, drawing on policy and regulatory documents, platform governance materials, public accountability reports, and composite vignettes constructed from recurring patterns documented in public inquiries, investigative journalism, and scholarly research. The study does not rely on interviews, surveys, or direct participant observation. The vignettes used here are not real cases; rather, they are synthetic narratives designed to illustrate typical ways people encounter automated systems, allowing the analysis to examine social meaning without claiming to measure frequency or lived experience directly.

The article makes two principal contributions. Conceptually, it argues that automated judgement should be understood as a form of institutional power that operates through classification rather than deliberation. By linking insights from public governance, digital labour, and welfare automation, it shows that classification is not only a technical function but a social process that shapes recognition, credibility, and access. Empirically, it develops a dual account of inequality, demonstrating that automated systems both amplify historical disadvantage through patterned data and produce new forms of exclusion through data-driven abstraction that detach individuals from familiar legal or moral categories.

The sections that follow develop a framework for understanding algorithmic authority, outline the methodological approach, present cross-domain findings, interpret these findings through sociological theory, and propose governance reforms aimed at strengthening intelligibility, accountability, inclusion, and public trust. The central claim is that artificial intelligence is no longer peripheral to social life. It has become an emerging institutional force that reshapes how people understand judgement, opportunity, and their place within systems of public value.

2. Conceptual Architecture: Locating Algorithmic Power in the Social Realm

Automated systems are commonly presented as technical instruments designed to make routine decisions faster, cheaper, and more consistent. While this framing highlights efficiency gains, it understates the broader social implications of automation. Contemporary research increasingly indicates that automated systems do more than execute predefined rules. They function as classificatory infrastructures that influence how institutions categorise individuals, how people understand their own social standing, and how opportunities are distributed across populations. For this reason, this article treats automated systems not merely as technological tools but as institutional actors whose classifications carry social, political, and moral consequences.

Prior scholarship suggests that encounters with automated systems are shaped as much by institutional contexts as by computational logic. Fang et al. [7] show that algorithmic outputs are often perceived as authoritative even when their reasoning remains inaccessible, reflecting the institutional credibility attached to automation. Research on digital welfare infrastructures further indicates that automated scoring systems embed normative assumptions about deservingness, risk, and compliance, producing categories that implicitly express moral judgement rather than neutral assessment [8]. Related work on algorithmic imaginaries demonstrates that classification systems also shape which identities, claims, and narratives appear legitimate in digital and public communication environments [9]. These effects are especially visible in studies of marginalised communities, where algorithmic misclassification or suppression can operate as a mechanism of exclusion rather than impartial governance [10].

The institutional consequences of automation extend beyond individual classification and into broader governance relationships. Parviainen et al. [11] argue that algorithmic decision systems alter how citizens relate to public institutions by replacing interpersonal judgement with data-driven representation. In media and communication contexts, algorithmic filtering has been shown to recalibrate perceptions of credibility and authority, influencing what information is amplified and what is disregarded [12]. Grimmelikhuijsen [13] further observes that automated infrastructures increasingly perform organisational gatekeeping functions, determining which claims enter formal administrative processes and which are filtered out before human review.

Taken together, these strands of research suggest that automated systems reshape three interrelated domains: institutional authority, social visibility, and the normative foundations of legitimacy. The conceptual framework developed in this article builds on these insights by focusing on automation as a social and institutional phenomenon rather than solely a technical one. It does not claim to measure the prevalence of specific public attitudes or lived experiences. Instead, it synthesises documented evidence from policy materials, platform governance texts, regulatory reports, and prior scholarly research to interpret how algorithmic systems restructure recognition, classification, and trust.

To operationalise this framework, Section 2.1 examines delegated authority, referring to the institutional process through which organisations treat algorithmic outputs as binding judgements. Section 2.2 analyses classification as the mechanism through which automated systems construct visibility, credibility, and social presence. Section 2.3 explores opacity and procedural justice, focusing on how limited intelligibility alters normative expectations of fairness and accountability. Finally, Section 2.4 introduces a dual-pathway model of inequality, conceptualising how automated systems both amplify historical disadvantage and generate new forms of exclusion through computational abstraction.

2.1. Delegated Authority and the Rise of Automated Judgement

Delegated authority describes the institutional process through which organisations transfer decision-making power from human officials to automated systems and subsequently treat algorithmic outputs as binding judgements. This shift does not merely replace one decision-maker with another. It transforms how decisions are justified, how responsibility is distributed, and how individuals interpret institutional fairness and legitimacy.

Importantly, delegation often occurs well before a system is deployed in practice. Herrera Poyatos et al. [14] show that value judgements are frequently embedded during early design stages, including the selection of optimisation goals, feature weighting, and audit criteria. These choices shape how systems prioritise efficiency, risk, or compliance, yet they are rarely subjected to public scrutiny or democratic deliberation. Once implemented, these design decisions acquire institutional authority even though they remain largely invisible to those affected by them.

Evidence from recruitment systems illustrates the downstream consequences of this delegation. Fabris et al. [15] document how hiring algorithms trained on historical organisational data tend to reproduce existing employment patterns. Variables such as educational background, employment gaps, or career trajectories may appear neutral, but they often function as indirect carriers of long-standing social inequalities. In this context, delegation does not eliminate bias. Instead, it stabilises and scales existing patterns under the appearance of technical objectivity.

From a broader sociological perspective, Zajko [16] argues that automated judgement replaces deliberative reasoning with what can be described as statistical inheritance. Rather than evaluating individuals in context, automated systems infer future behaviour from past patterns, effectively converting historical inequalities into predictive evidence. Atoum et al. [17] further note that this shift complicates accountability. Because the internal logic of automated systems is typically opaque, individuals cannot easily challenge decisions, even though those decisions carry institutional weight.

Taken together, these studies suggest that delegated authority should not be understood as a neutral efficiency reform. It represents a redistribution of institutional power from identifiable human actors to computational infrastructures whose assumptions are difficult to inspect, contest, or explain. Automated decisions often appear objective because their underlying criteria remain hidden, and they appear final because institutions present them as final. As a result, delegated authority reshapes the moral and procedural foundations through which legitimacy has traditionally been constructed.

This conceptualisation does not assume direct access to the lived experiences of affected individuals. Rather, it synthesises documented institutional practices and prior scholarly analyses to interpret how authority is reorganised when organisations rely on automated judgement. The next section builds on this foundation by examining how classification functions as the primary mechanism through which automated systems construct visibility, credibility, and institutional recognition.

2.2. Classification, Sorting, and the Social Construction of Visibility

Classification is the primary mechanism through which automated systems organise social visibility and institutional relevance. Through sorting, ranking, and scoring processes, automated systems determine which individuals, behaviours, or claims become visible, marginal, credible, or dismissible within institutional and digital environments. Unlike traditional bureaucratic categorisation, algorithmic classification operates continuously, at scale, and without granting those subject to it access to the rules that shape their classification.

Research on platform governance illustrates how classification structures visibility. Kojah et al. [18] show that creators often experience ranking systems as dynamic authorities that influence whether their content is surfaced or suppressed. In this context, visibility is not merely the outcome of merit or effort but is shaped by engagement-driven metrics embedded in platform architectures. Duffy and Meisner [19] further demonstrate that these classificatory processes generate stratified attention economies in which certain content styles, identities, or communicative norms are systematically advantaged over others.

Public administration scholarship highlights a parallel dynamic in institutional settings. Fang et al. [20] find that individuals frequently interpret algorithmic classifications as procedural facts, even when they lack insight into how those determinations were made. This effect is reinforced by organisational narratives that frame automated systems as neutral or objective instruments, thereby masking the political, managerial, and normative choices embedded in their design.

Welfare automation research provides additional insight into the moral dimensions of classification. Larasati et al. [21] show that risk-scoring systems encode implicit assumptions about compliance, responsibility, and deservingness, producing categories that carry symbolic and normative significance beyond their administrative function. Parviainen et al. [22] extend this analysis by arguing that algorithmic assessments can influence how individuals anticipate institutional judgement, encouraging behavioural adaptation in response to expected sorting practices. In this way, classification shapes both institutional recognition and how individuals understand their own positioning within institutional systems.

Beyond administrative and welfare contexts, classificatory infrastructures also influence epistemic authority. Walter and Farkas [23] demonstrate that algorithmic relevance-ranking systems affect which knowledge claims gain legitimacy within digital public discourse. Decker et al. [24] similarly note that automated categorisation influences perceptions of fairness by shaping the informational environment in which institutional decisions are interpreted and evaluated.

The contribution of this section lies in conceptualising classification as an institutional process rather than a purely technical operation. The existing literature often treats algorithmic sorting as either a computational function or a cultural phenomenon tied to visibility. The framework developed here integrates these perspectives by interpreting classification as a relational mechanism through which institutions construct recognition, credibility, and social presence. In this sense, automated classification does not merely process information. It performs institutional work by defining who is seen, how they are evaluated, and what forms of participation or opportunity become available.

2.3. Trust and the Perception of Procedural Justice

Trust in institutional decision-making has traditionally rested on three core expectations: that individuals can understand how decisions are made, that their circumstances are meaningfully considered, and that outcomes can be questioned or reviewed. Automated decision systems complicate each of these expectations by relocating judgement into computational processes that are typically opaque, standardised, and procedurally closed to those affected by them.

Research in public administration suggests that automation can sometimes enhance perceived legitimacy. Goldsmith et al. [1] show that some individuals interpret algorithmic outputs as impartial or neutral, even when they cannot access the reasoning behind them. In these contexts, the presence of technology itself can operate as a symbolic marker of objectivity, encouraging the acceptance of decisions without requiring transparency.

However, studies in welfare governance and platform regulation reveal a different pattern. Larasati et al. [25] document that, when automated determinations conflict with individuals’ understanding of their own circumstances, opacity is often interpreted not as technical complexity but as institutional disengagement. In these cases, unexplained outcomes are experienced as evidence that decision-making processes failed to acknowledge personal context or social reality. Rather than reinforcing trust, automation can signal detachment or indifference.

This contrast highlights a broader sociological tension in how procedural justice is understood under automation. Some policy and technical frameworks assume that improving explanation or transparency will restore legitimacy. Zajko [26], however, argues that this framing underestimates the relational dimensions of trust. The challenge is not only that algorithmic systems obscure reasoning, but that they reduce opportunities for dialogue, contestation, and recognition. Automated processes typically provide limited space for individuals to clarify meaning, express disagreement, or feel heard within institutional procedures.

Related findings reinforce this interpretation. Fang et al. [7] observe that people often treat automated decisions as final, even when they do not understand them, suggesting that authority is being relocated from interpersonal judgement to system-based classification. Platform governance research further indicates that when visibility or ranking shifts occur without explanation, users may interpret these changes as punitive or arbitrary rather than procedural [18]. Across these settings, perceptions of fairness are shaped less by technical accuracy and more by whether institutional processes appear attentive, responsive, and accountable.

The contribution of this section lies in reframing trust in automated systems as a relational rather than purely informational phenomenon. Trust is not determined solely by whether rules are disclosed or models are explainable. It is shaped by whether individuals perceive that institutions meaningfully recognise them within decision-making processes. Automated judgement can weaken this perception by replacing interpersonal evaluation with abstract classification, thereby limiting the social cues through which fairness, care, and accountability have historically been communicated.

This perspective helps explain why automation can generate acceptance in some institutional contexts while producing scepticism or resistance in others. It also clarifies why technical interventions such as explainable AI, fairness auditing, or transparency tools—while valuable—may be insufficient on their own to restore legitimacy. The challenge is not only to make automated systems more interpretable, but to embed them within institutional practices that preserve recognition, responsiveness, and procedural voice.

2.4. Inequality Through Automated Pathways

Discussions of algorithmic inequality often frame automated systems as mirrors of society, reproducing historical disparities when training data reflect entrenched bias. While this account captures an important mechanism, it does not fully explain the new patterns of inequality emerging in automated recruitment, welfare assessment, and platform visibility systems. Automated systems do not merely inherit inequality; they actively reorganise how inequality is produced, classified, and experienced.

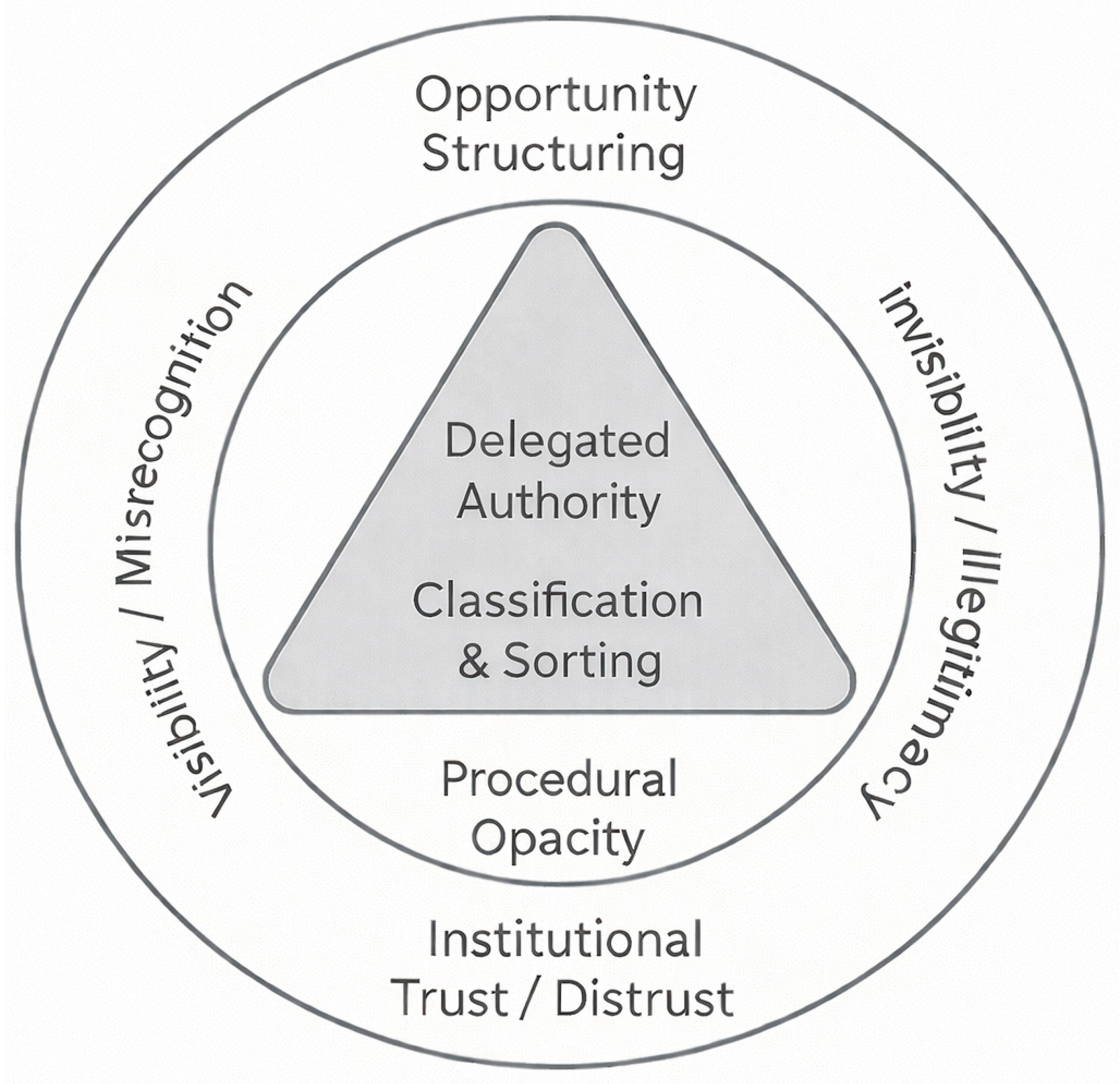

Figure 1 illustrates this reorganisation by conceptualising two interconnected pathways through which automated systems generate inequality: amplification and novelty. These pathways arise from the combined effects of delegated institutional authority, automated classification, and procedural opacity.

Figure 1.

Automated Judgement as Institutional Power: A Relational Architecture of Delegated Authority, Classification, Opacity, and Inequality Pathways. Source: Author’s conceptual model based on synthesis of policy, governance, and scholarly sources analysed in this study.

The first pathway, amplification, describes how automated systems reinforce existing social hierarchies by encoding historical patterns into predictive models. Recruitment research shows that algorithmic hiring tools often treat past employment trends as indicators of suitability, thereby stabilising gendered and racialised disparities within computational decision-making routines [27]. Zajko [28] argues that this is not simply a design flaw but a structural feature of predictive analytics, which rely on historical regularities to forecast future outcomes. As shown in Figure 1, amplification operates through statistical inheritance: past inequalities are translated into present classifications, even when sensitive demographic attributes are formally excluded.

The second pathway, novelty, refers to inequalities produced through computational abstraction rather than historical replication. Automated systems increasingly generate categories that have no direct counterpart in legal, social, or moral frameworks. Welfare scoring systems, for instance, assign individuals to newly constructed classifications such as predicted non-compliance or administrative risk—labels that citizens may not recognise as meaningful descriptions of their lived circumstances [8]. Parviainen et al. [11] further demonstrate that algorithmic profiling can assign people to categories defined entirely within the internal logic of a model, detached from conventional identity markers or institutional norms. As represented in Figure 1, this pathway produces inequality by creating new classificatory regimes rather than reproducing old ones.

Platform governance provides a clear illustration of how these two pathways interact. Kojah et al. [18] show that marginalised creators can experience disproportionate suppression not only because of pre-existing inequalities, but also because platform optimisation metrics privilege particular behavioural patterns, aesthetic styles, or temporal rhythms. Duffy and Meisner [19] similarly document how visibility hierarchies emerge from engagement-based ranking systems that generate new standards of credibility and relevance. These hierarchies are not direct extensions of offline social structures; they are produced by platform architectures themselves, as reflected in Figure 1’s depiction of optimisation-driven classification.

What the existing scholarship has largely lacked is a framework that accounts for both amplification and novelty within a single institutional model. Research on predictive policing, automated eligibility, and platform moderation often isolates one mechanism while overlooking the others. Figure 1 responds to this gap by situating both pathways within a unified structure of automated judgement, showing how inherited inequality and newly generated exclusion operate simultaneously rather than independently.

This dual process has important implications for how inequality is understood and experienced. When automated systems amplify historical disadvantage, individuals may interpret outcomes as continuations of familiar injustice. When systems generate novel classifications, individuals may instead experience decisions as arbitrary, opaque, or disconnected from recognisable social categories. In both cases, inequality extends beyond material disadvantage to affect how fairness, legitimacy, and institutional responsibility are perceived.

The contribution of this section lies in reframing algorithmic inequality as a two-track process that cannot be reduced to bias alone. Amplification accounts for continuity with past hierarchies, while novelty explains how automated systems create new forms of exclusion that reshape identity, opportunity, and trust. As synthesised in Figure 1, these pathways operate together within contemporary automated systems, helping to explain why algorithmic inequality can appear both familiar and unprecedented at the same time.

3. Methodology: A Multi-Source Sociological Inquiry

Examining how automated systems reshape opportunity, identity, and public trust requires a method that captures both institutional design and social meaning. Many algorithmic systems operate behind organisational and technical opacity, meaning neither public policy documents nor engineering disclosures alone provide a full account of how decisions are produced or how they are experienced. To address this challenge, this study adopts a qualitative, multi-source research design that analyses institutional texts, platform governance materials, technical system descriptions, and composite vignettes derived from publicly documented evidence.

The core empirical foundation of the study consists of policy frameworks, regulatory reports, oversight reviews, platform governance guidelines, transparency disclosures, and publicly available technical documentation relating to automated decision systems in employment, welfare administration, and digital platforms. These materials are treated not as neutral records, but as institutional artefacts that reveal how organisations frame automation, justify algorithmic authority, and embed normative assumptions about risk, merit, compliance, visibility, and fairness. Prior research supports the analytical value of such sources, demonstrating that official documentation often exposes the discursive and moral logics through which automated systems gain legitimacy, even when their internal mechanics remain inaccessible [7,8,18].

However, institutional documents alone cannot explain how automated decisions are interpreted, felt, or socially negotiated. To capture this experiential dimension, the study employs composite vignettes constructed from recurring patterns documented in regulatory inquiries, investigative journalism, public complaints, audit reports, and the existing scholarly literature. These vignettes do not represent real individuals and do not claim empirical measurement of frequency. Instead, they function as analytical devices designed to illustrate typical modes of encounter with automated judgement—including experiences of exclusion, misrecognition, uncertainty, and behavioural adaptation—without involving direct human participants. This approach reflects findings in digital labour and welfare research showing that people interpret algorithmic outcomes through relational, moral, and emotional frameworks that are not visible in technical records alone [19,25].

The methodological strategy rests on two central commitments. First, institutional texts are analysed as expressions of the value systems, incentives, and governance priorities that shape automated decision infrastructures. Second, vignette-based interpretation is used to surface how these infrastructures are likely to be experienced in everyday social contexts, drawing on documented public evidence rather than primary fieldwork. Together, these sources enable a sociologically grounded analysis of algorithmic authority that traces how automation operates across design, organisational framing, and social interpretation.

The subsections that follow specify how sources were selected, how policy and platform materials were analysed, how composite vignettes were constructed, and how thematic and conceptual insights were derived. This structure ensures transparency about the study’s scope, strengthens methodological reproducibility, and situates the findings as interpretive and theory-building rather than statistical or ethnographic claims.

3.1. Rationale for a Multi-Source Design

Automated decision systems cannot be meaningfully understood through a single type of evidence. Technical documentation offers limited insight into how systems operate in practice. Policy texts describe institutional intentions but frequently conceal how automation reshapes power, discretion, and responsibility. Platform governance materials outline formal rules yet rarely reveal how ranking, filtering, or visibility mechanisms actually function in everyday use. Relying on only one method would therefore produce an incomplete and potentially distorted account of algorithmic influence.

This study adopts a multi-source qualitative design in order to capture the technical, institutional, and social dimensions of automated judgement. The approach allows the analysis to examine how automated systems are justified in policy, implemented within organisations, and experienced in real-world social settings.

One component of the dataset consists of institutional and regulatory documents. These include public sector automation strategies, algorithmic accountability frameworks, regulatory oversight reports, audit findings, procurement records, platform transparency disclosures, and governance guidelines relating to automated hiring, welfare administration, and digital content ranking. These materials are analysed because they reveal how institutions define fairness, assign responsibility, frame automation as legitimate, and embed normative assumptions about risk, efficiency, and deservingness. Prior research demonstrates that such documents provide insight into the values and power structures shaping automated systems, even when technical details remain inaccessible [7,8,18].

A second source category includes platform governance materials and publicly available technical documentation. This includes moderation policies, ranking explanations, recommendation system disclosures, engineering publications, patent filings, and official statements describing algorithmic design priorities. These materials are not treated as complete representations of system logic. Instead, they are analysed as institutional narratives that shape public expectations and legitimise algorithmic authority. Existing scholarship shows that platforms often present a rhetoric of transparency while maintaining significant operational opacity [19,25].

A third source consists of composite vignettes developed from recurring patterns documented in regulatory inquiries, public complaints, investigative journalism, court records, and peer-reviewed research. These vignettes do not represent real individuals, nor do they claim to measure population-level prevalence. Rather, they function as structured interpretive tools that synthesise publicly documented experiences into analytically coherent scenarios. This method enables the study to examine how automated decisions are interpreted and felt in everyday contexts while preserving ethical safeguards and avoiding reliance on unverifiable anecdotal claims.

The study does not present itself as a statistical assessment of frequency or causal impact. Instead, it is a qualitative and interpretive investigation designed to identify recurring mechanisms, institutional logics, and relational consequences of automated decision-making across domains. The multi-source strategy strengthens analytical credibility by enabling triangulation across policy discourse, governance practice, technical framing, and documented public encounters.

By clearly defining the categories of sources used, the institutional contexts examined, and the interpretive role of composite vignettes, this design directly addresses concerns about transparency, traceability, and reproducibility. Readers are therefore able to understand the scope, limits, and evidentiary basis of the study’s claims.

3.2. Policy and Regulatory Document Analysis

Policy and regulatory documents provide a critical lens for examining how automated decision systems acquire institutional authority and legitimacy. These texts do not merely describe how systems function; they reveal the normative assumptions, governance priorities, and accountability narratives that shape why and how automation is adopted in public and quasi-public settings. For this reason, policy materials are treated in this study not as neutral background sources but as sociologically meaningful artefacts that encode institutional power, moral judgement, and public justification.

Consistent with earlier research, institutional documentation often offers insight into how organisations frame automated systems, even when the technical logic remains opaque [7]. Larasati et al. demonstrate that welfare policies and administrative manuals frequently embed implicit moral assumptions about risk, compliance, and deservingness, which later become operationalised through automated scoring systems [8]. In a similar vein, platform governance research shows that formal rules and transparency statements shape user expectations while concealing deeper optimisation priorities that determine visibility and ranking outcomes [18].

The document corpus analysed in this study includes public automation strategies, regulatory oversight reports, algorithmic accountability frameworks, transparency guidelines, data protection assessments, and governance statements relevant to employment screening, welfare administration, and digital platform moderation. These materials were drawn primarily from governance contexts in the United Kingdom, the European Union, and North America, with publication dates spanning approximately 2018 to 2025. This timeframe captures the period in which automated decision systems transitioned from pilot initiatives into routine institutional infrastructures.

Selection criteria focused on documents that explicitly addressed automated or algorithmic decision-making, institutional accountability, fairness, transparency, risk management, or public legitimacy. Sources were chosen where they offered substantive engagement with governance questions rather than purely technical descriptions or promotional narratives.

The analytical focus was interpretive rather than technical. Documents were examined for how they define decision-making authority, construct fairness and legitimacy, frame the delegation of judgement to automated systems, and describe institutional responsibility when automated outcomes cause harm. Particular attention was paid to how policies articulate categories such as risk, fraud, efficiency, deservingness, neutrality, and public trust, as these concepts frequently shape the social meaning of automated classifications.

This approach aligns with scholarship showing that organisational narratives play a powerful role in legitimising algorithmic authority, often well before systems are publicly deployed [1,7]. It also reflects findings that governance documents frequently present automation as objective or neutral while embedding value-laden assumptions that influence how individuals are classified and treated [8].

In addition to policy texts, oversight and audit reports were analysed to identify tensions between stated institutional commitments and documented real-world effects. This enabled the study to trace where accountability gaps emerge, how institutional responsibility becomes diffused, and how automated decision systems are justified even when their social consequences remain contested.

Rather than treating policy materials as direct evidence of system performance, this study uses them to reconstruct the institutional narratives that surround automation. These narratives shape how automated decisions come to be accepted as authoritative, how responsibility is framed, and how legitimacy is socially produced. By grounding the analysis in clearly defined policy sources while maintaining an interpretive lens, this section strengthens both methodological transparency and analytical credibility.

3.3. Platform Governance and Technical Documentation Review

Digital platforms are among the most visible sites where automated systems shape public voice, credibility, and access to attention. Ranking and recommendation systems determine whose content circulates widely, whose labour becomes economically viable, and whose perspectives remain marginal. To understand these dynamics, this study examines both platform governance documents and publicly available technical materials as sources of institutional meaning and infrastructural power.

Platform governance texts include community standards, content moderation rules, ranking disclosures, and transparency reports published by major social and content platforms. These materials provide insight into how platforms justify automated decision-making, communicate fairness commitments, and shape user expectations about visibility and legitimacy. However, as Kojah et al. show, governance narratives frequently present simplified explanations that conceal the deeper optimisation logics that actually structure visibility outcomes [18]. Duffy and Meisner similarly demonstrate that platforms often portray stability and predictability while routinely adjusting algorithmic parameters in ways that creators cannot anticipate or contest [19]. In this study, such documents are therefore treated not as direct descriptions of algorithmic function but as institutional narratives that reveal platform priorities and power relations.

Publicly accessible technical materials offer a complementary perspective. Although full algorithmic models remain proprietary, platforms and affiliated researchers routinely publish engineering blog posts, research summaries, patent filings, and technical white papers that disclose ranking objectives, feedback signals, and performance metrics. These sources make it possible to infer the behavioural incentives and commercial priorities embedded in platform architectures. Zajko observes that attention-driven ranking systems are structured to maximise engagement rather than user wellbeing or representational equity, thereby privileging particular communication styles and participation patterns [16]. Parviainen et al. further show that technical classification systems shape how individuals understand their own social positioning, particularly when algorithmic feedback becomes a key measure of relevance or worth [22].

The analytical approach applied to these materials is interpretive rather than computational. Governance and technical texts were examined for how they define relevance, construct quality, classify user behaviour, and justify automated authority. This interpretive stance follows Walter and Farkas, who demonstrate that algorithmic documentation functions as a narrative device that frames automated decisions as reasonable, neutral, or inevitable, even when their social consequences remain opaque [23]. Reading these materials as cultural and institutional artefacts allows the analysis to uncover how platforms construct legitimacy while simultaneously restricting meaningful accountability.

Across the reviewed sources, several consistent patterns emerged. Platforms publicly emphasise transparency while withholding information about the ranking signals that most strongly influence visibility. They promote ideals of fairness and merit while relying on engagement metrics that advantage specific temporal rhythms, linguistic styles, aesthetic conventions, and behavioural norms. They assert neutrality while embedding optimisation priorities that align more closely with commercial performance than with democratic or civic values. These dynamics resonate with Lopezmalo’s findings that marginalised creators often experience unexplained suppression that cannot be justified through formal platform rules but can be traced to opaque ranking incentives [10].

Integrating governance narratives with technical disclosures serves two analytical purposes. First, it reveals how platforms frame automated authority in ways that manage public perception and deflect responsibility. Second, it exposes the infrastructural mechanisms through which visibility becomes a form of social power that distributes recognition, opportunity, and symbolic legitimacy. This component of the methodology is therefore essential for understanding how individuals encounter algorithmic judgement in digital spaces and how platform architectures contribute to the reproduction and transformation of inequality.

3.4. Composite Vignettes as Analytical Tools

Automated decision systems are rarely experienced through policy documents or technical interfaces alone. They are encountered through concrete moments in everyday life, such as receiving an unexplained welfare denial, being excluded from a recruitment shortlist, or watching online visibility decline without warning. These encounters often generate confusion, frustration, resignation, or adaptation, yet such experiential dimensions are difficult to capture through institutional texts or technical disclosures alone.

Because this study does not rely on interviews, surveys, or direct observation of individuals, it uses composite vignettes as an interpretive method to examine how automated decisions are commonly experienced and understood. The vignettes are not representations of real individuals. Instead, they are carefully constructed narrative syntheses drawn from recurring patterns documented in public inquiries, regulatory reports, investigative journalism, court cases, and prior peer-reviewed scholarship. Their purpose is not to measure frequency or prevalence, but to illustrate typical ways in which automated authority is encountered and interpreted across institutional settings.

This approach builds on prior research showing that people interpret algorithmic decisions through moral, relational, and identity-based frameworks rather than purely technical reasoning. Studies of welfare automation demonstrate that individuals often evaluate automated outcomes in terms of dignity, recognition, and fairness rather than procedural correctness [25]. Research on digital labour similarly shows that creators interpret algorithmic visibility shifts through narratives of value, legitimacy, and exclusion [19]. Composite vignettes allow these interpretive dynamics to be analysed in a structured way while avoiding the ethical and procedural requirements associated with collecting primary data from human participants.

To ensure transparency and methodological integrity, each vignette was constructed from publicly documented cases rather than imagined scenarios. Source materials included published regulatory investigations, parliamentary inquiries, civil society reports, platform transparency disclosures, legal challenges, and academic studies. The vignettes therefore do not invent experiences but condense recurring patterns into analytically coherent scenarios that reflect institutional and social realities reported in existing evidence.

The use of vignettes serves two primary analytical functions. First, it allows the study to examine how automated decisions are perceived and interpreted in practice, rather than only how they are designed or justified by institutions. While governance documents and technical materials reveal how automated systems are framed, they cannot fully capture how people experience opacity, misclassification, or denial. Vignettes bridge this gap by showing how institutional decisions are emotionally processed, morally evaluated, and socially negotiated.

Second, vignettes enable a systematic comparison across domains. For example, patterns observed in welfare automation can be analytically compared with experiences documented in platform governance or hiring systems, allowing the study to identify cross-domain similarities in how automated authority affects recognition, opportunity, and trust. This comparative function supports the broader goal of tracing structural dynamics that extend beyond any single institutional setting.

It is important to clarify the limitations of this method. Because the study does not involve direct engagement with participants, the vignettes do not claim to represent lived experience in a statistical or demographic sense. They are interpretive tools rather than empirical measurements. Their value lies in illustrating social mechanisms and meaning making processes, not in quantifying prevalence or predicting individual behaviour. This limitation is acknowledged explicitly to ensure that conclusions drawn from the vignettes are understood as conceptual and analytical rather than empirical generalisations.

The analytical strategy applied to all sources treats automated decision systems as institutional actors rather than neutral technical instruments. This follows sociotechnical and public administration research showing that automated tools acquire authority through organisational endorsement, legal framing, and cultural legitimacy as much as through computational design [7,8,10]. The analysis therefore reconstructs how institutional priorities, model design choices, governance narratives, and public interpretation converge to produce outcomes experienced as authoritative, legitimate, or exclusionary.

The interpretive process unfolded in three stages. First, institutional and platform materials were examined thematically to identify recurring assumptions about fairness, risk, compliance, relevance, and legitimacy. Second, these institutional logics were connected to documented public responses, reported harms, and observed adaptation strategies through process tracing that mapped how technical design choices translate into lived consequences. Third, insights from all materials were organised using the analytical matrix presented in Table 1, which clarifies how different categories of evidence contribute to understanding automated authority as a social structure rather than a technical output.

Table 1.

Conceptual–Methodological Matrix for Analysing Algorithmic Power as Institutional Authority Across Evidence Types and Domains. Source: Author’s analytical framework and classification of source materials used in this study.

This matrix functions as more than a summary device. It serves as the analytical backbone of the study by linking institutional rationales, classification mechanisms, behavioural adaptation, symbolic legitimacy, and inequality outcomes across domains. Through this structure, the study identifies recurring mechanisms such as the normalisation of opacity as a substitute for justification, the transformation of classification into a signal of recognition or exclusion, and the dual production of inequality through both historical reproduction and data-driven novelty.

Taken together, this methodological approach strengthens the article’s central claim. Automated judgement is not merely a computational procedure. It is a form of institutional power that operates through classification, narrative framing, and social interpretation. Composite vignettes, when grounded in public evidence and analysed transparently, provide a rigorous way to connect institutional design with the everyday meanings people attach to automated decisions.

3.5. Analytical Strategy and Evidence Integration

The analytical strategy adopted in this study is designed to ensure that interpretations remain grounded in documented evidence while allowing for sociological theorisation about how automated authority operates across institutional settings. Rather than treating automated systems as isolated technical artefacts, the analysis reconstructs the institutional, legal, technical, and interpretive processes through which algorithmic decisions become authoritative in everyday life.

All materials were examined through a structured thematic reading aimed at identifying recurring logics of judgement, classification, legitimacy, and institutional responsibility. Policy texts, regulatory reports, welfare manuals, platform governance documents, and technical disclosures were analysed to uncover the assumptions they encode about risk, deservingness, relevance, compliance, and credibility. This step follows prior research showing that legitimacy is shaped not only by outcomes but also by the narratives institutions construct to justify automated decisions [7,8].

To strengthen transparency and analytical traceability, sources were grouped into defined categories, including regulatory and policy documents, platform governance materials, technical system descriptions, legal and investigative reports, and composite vignettes derived from publicly documented cases. Each category was treated according to its epistemic role, meaning that institutional texts were analysed as expressions of organisational intent, technical materials as indicators of design priorities, and vignettes as interpretive syntheses of reported social experience. This layered approach ensures that claims about institutional behaviour, system design, and lived interpretation are not conflated.

The study applies process tracing to connect institutional design choices with their observable social consequences. This involved mapping how organisational objectives, optimisation targets, training data assumptions, and governance narratives translate into classification outcomes that individuals encounter as final or authoritative. Through this approach, it becomes possible to trace how discretion shifts from frontline workers into computational systems, how historical data patterns shape present decision-making, and how opacity influences perceptions of fairness and recognition [4,8,10].

To enhance coherence and cross-domain comparison, insights from all source categories were organised using the analytical matrix presented in Table 1. The matrix does not merely summarise evidence. It structures how institutional rationalities, legal frameworks, model design choices, behavioural responses, and symbolic legitimacy intersect to produce the social effects of automated judgement. By aligning each analytical dimension with a specific category of source material, the matrix clarifies how conclusions are grounded in documented evidence rather than speculative inference.

For example, rows addressing institutional rationality and legal framing draw directly on regulatory and policy sources. Rows concerning classification and optimisation reflect insights from technical documentation and platform governance texts. Rows analysing lived interpretation and trust are informed by composite vignettes synthesised from publicly reported cases. This structure improves reproducibility by making explicit which forms of evidence support each analytical claim, even where proprietary system details remain unavailable.

Across domains including recruitment, welfare administration, and platform governance, the analysis identifies recurring mechanisms. These include the institutional normalisation of opacity as a substitute for justification, the use of classification as a signal of legitimacy or exclusion, the reproduction of inequality through statistical inheritance, and the emergence of new forms of stratification through data driven abstraction. By tracing these mechanisms across multiple evidence sources, the study avoids reliance on single-case interpretations and instead builds a cumulative argument about how automated authority functions socially.

The analytical strategy does not claim to measure prevalence, predict outcomes, or reconstruct proprietary system behaviour. Its aim is interpretive rather than predictive. It seeks to explain how automated systems become socially meaningful, how they acquire legitimacy, and how they reshape recognition, opportunity, and trust. By grounding each interpretive step in traceable source categories and clearly distinguishing empirical documentation from conceptual synthesis, the approach responds directly to concerns about methodological transparency and reproducibility.

In sum, this strategy allows the study to move beyond surface descriptions of automated systems and toward a sociological explanation of how algorithmic judgement becomes embedded in institutional practice and everyday social life.

3.6. Methodological Limitations

This study uses a document-based and vignette-driven qualitative design. It does not measure how frequently the observed patterns occur, nor does it claim statistical generalisability. The composite vignettes are interpretive syntheses based on publicly documented cases rather than firsthand interviews, meaning the analysis captures typical interaction patterns rather than individual life histories.

The findings should therefore be understood as conceptual and sociological explanations of how automated systems shape recognition, opportunity, and trust, rather than empirical claims about prevalence. While this approach limits direct observation of lived experience, it enables systematic examination of institutional logics, governance practices, and public evidence that would be difficult to access through participant-based research alone.

4. Findings: Cross-Domain Patterns in Automated Judgement

This section presents patterns observed across policy documents, regulatory reports, platform governance materials, public complaints, investigative journalism, and composite vignettes constructed from publicly documented cases. Rather than treating automated hiring, welfare systems, and platform algorithms as separate technical domains, the findings highlight recurring institutional dynamics in how automated systems classify individuals, shape access to opportunities, and influence perceptions of legitimacy.

Across sources, a consistent pattern emerges: automated systems are experienced not only as tools that process information but as institutional decision-makers whose outputs carry social meaning. Public records, oversight reports, and platform transparency disclosures repeatedly show that individuals interpret automated outcomes as signals about their credibility, deservingness, employability, or relevance, even when no explanation is provided. These interpretations appear across employment screening, welfare eligibility processes, and digital visibility regimes.

The findings do not claim to measure the frequency of these experiences. Instead, they identify recurrent institutional patterns documented across multiple public sources. Composite vignettes are used as illustrative devices to synthesise these recurring patterns and to demonstrate how institutional decisions may be encountered in everyday contexts. They do not represent real individuals, nor do they serve as empirical case studies. Rather, they summarise typical modes of interaction reported in public evidence.

Four cross-domain patterns are especially salient in the reviewed materials. First, automated systems frequently replace interpersonal judgement with silent or opaque classification, leaving affected individuals without a clear understanding of how decisions were made. Second, automated decisions tend to function as institutional verdicts rather than provisional recommendations, even when mechanisms for appeal exist in principle. Third, automated classification systems appear to reshape how individuals understand their own status within institutional hierarchies, particularly when outcomes affect employment prospects, access to welfare, or online visibility. Fourth, patterns of inequality arise not only from the reproduction of historical disadvantage but also from the creation of new data-driven categories that lack clear grounding in legal or social norms.

The subsections that follow examine how these patterns manifest in three domains where automated judgement is highly visible: recruitment and hiring, welfare administration, and digital platform governance. Each subsection first outlines documented institutional patterns, then illustrates how these patterns may be encountered through composite vignettes and finally identifies the sociological implications that arise from these observations.

4.1. Automated Recruitment and the Normalisation of Silent Exclusion

Public reports, regulatory discussions, and hiring platform disclosures indicate that automated recruitment systems are increasingly used to screen, rank, and filter job applicants before any human review occurs. These systems typically rely on historical hiring data, CV parsing tools, psychometric indicators, and behavioural proxies to predict candidate suitability or organisational “fit” [15]. Official narratives often frame these tools as efficiency-enhancing and bias-reducing. However, the reviewed materials reveal a different institutional dynamic.

Across documented cases, applicants frequently receive rejection outcomes without explanation, meaningful feedback, or clear routes for appeal. Regulatory complaints and investigative reporting show that candidates are often unable to determine whether they were rejected due to skills mismatch, data error, automated filtering thresholds, or other model-based criteria. This creates a recurring pattern in which exclusion is experienced as procedurally final but informationally empty.

Evidence from algorithmic hiring research suggests that predictive recruitment tools commonly reproduce historical hiring preferences when trained on past organisational data [15]. Even when explicit demographic indicators are removed, proxy variables such as educational background, employment gaps, geographic location, or linguistic markers can indirectly reproduce existing patterns of stratification [16]. As a result, exclusion may occur without any visible discriminatory intent, yet still reflect embedded institutional histories.

The composite vignette synthesises multiple publicly reported cases in which job seekers describe receiving rapid automated rejections without any explanation or human contact. In these narratives, applicants do not merely experience rejection as a routine administrative outcome. Instead, they attempt to interpret the silence itself, speculating whether they were misclassified, deemed unsuitable, or simply filtered out by an unseen process. What emerges from these accounts is not only a concern about fairness, but a broader uncertainty about whether their application was meaningfully evaluated at all.

This pattern highlights a sociological dimension that is not fully captured in dominant hiring-bias debates. Much of the existing literature focuses on whether recruitment algorithms produce accurate or fair predictions. The reviewed materials suggest an additional institutional effect: automated hiring systems can transform exclusion into an opaque and depersonalised process that weakens applicants’ sense of procedural recognition. The absence of explanation does not only limit transparency; it also reshapes how individuals interpret their standing within labour market institutions.

The key finding in this domain is therefore not limited to bias replication. Rather, automated recruitment appears to normalise a mode of institutional silence in which exclusion is delivered without relational engagement or interpretive grounding. This shifts how rejection is understood, from a contestable decision to an automated verdict whose rationale remains inaccessible.

4.2. Eligibility Automation and the Administrative Production of Misrecognition

Public audits, welfare oversight reports, and policy evaluations indicate that automated eligibility systems are increasingly used to assess benefit entitlement, detect risk, and prioritise cases for review [8]. These systems typically rely on administrative records, behavioural indicators, geospatial markers, and predictive scoring to classify claimants according to perceived risk, compliance likelihood, or eligibility status. While institutions often justify automation as a way to improve consistency and reduce administrative burden, documented cases reveal recurring concerns about misclassification and opaque decision-making.

Across reviewed materials, claimants frequently report receiving automated denials or benefit adjustments without clear explanations. Ombudsman complaints, investigative journalism, and regulatory inquiries show that individuals often struggle to understand why their circumstances were categorised as high-risk, non-compliant, or ineligible. In many cases, affected individuals are unable to determine whether decisions were based on outdated records, data errors, rigid thresholds, or predictive inferences.

Existing welfare research suggests that automated scoring systems embed normative assumptions about deservingness, responsibility, and risk [8]. These assumptions are not always explicit in policy texts, yet they shape how individuals are categorised and how their claims are evaluated. Rather than assessing people through direct engagement with their lived conditions, automated systems often translate complex social realities into simplified risk indicators or compliance profiles.

The composite vignette draws on recurring public cases in which parents, carers, or low-income claimants describe receiving benefit denials that conflict with their actual circumstances. In these documented patterns, individuals interpret automated outcomes not merely as bureaucratic decisions but as signals that institutions misunderstand or misjudge them. The sense of harm arises less from the financial decision alone and more from the perception that personal realities, vulnerabilities, or caregiving responsibilities have been reduced to abstract data points.

This pattern reveals a form of institutional misrecognition. Rather than feeling evaluated as persons with specific needs, individuals often experience automated welfare decisions as categorical judgements that misrepresent their identity, intentions, or moral standing. Prior research supports this interpretation, showing that automated welfare infrastructures can transform support systems into surveillance-oriented risk regimes [25].

The findings therefore suggest that harm in automated welfare governance is not limited to technical error or bias. It also stems from the way predictive classification replaces relational assessment. When automated systems substitute lived understanding with risk scoring, they reshape how citizens perceive state institutions, shifting welfare encounters from sites of support toward experiences of procedural distance and moral detachment.

4.3. Platform Visibility and the Algorithmic Rewriting of Social Worth

Digital platforms increasingly rely on ranking, recommendation, and moderation systems to determine which content gains visibility and which remains marginal. Platform transparency reports, governance policies, and prior research indicate that engagement metrics, user interaction patterns, posting frequency, and behavioural signals play a central role in shaping algorithmic visibility [18,19]. These systems therefore influence not only content reach but also whose voices, identities, and perspectives become prominent within digital public spaces.

Documented cases from creators, journalists, and civil society groups reveal recurring experiences of unexplained visibility fluctuations. Users frequently report sudden drops in audience reach, engagement, or monetisation without receiving a clear justification from platform operators. Governance policies typically provide broad explanations centred on quality, safety, or community standards, yet these high-level narratives rarely explain how specific ranking or suppression decisions are made in practice.

Research on platform governance suggests that algorithmic visibility is shaped less by neutral assessments of content value and more by optimisation strategies that prioritise retention, engagement velocity, and commercial performance [18]. Duffy and Meisner [19] further show that creators interpret shifts in visibility not simply as technical outcomes but as reflections of personal credibility, relevance, or social worth. In this sense, platform ranking systems operate as informal gatekeepers of recognition and legitimacy.

The composite vignette synthesises publicly documented patterns in which creators experience visibility loss as arbitrary, punitive, or targeted, even when they cannot identify any violation of platform rules. These patterns align with evidence that ranking systems can privilege particular expressive styles, posting rhythms, language patterns, or audience behaviours, thereby producing uneven exposure across different communities and identity groups [10].

Beyond economic consequences, visibility systems shape how individuals understand their social presence. Walter and Farkas [23] show that algorithmic curation influences perceptions of credibility and authority by determining which voices appear prominent or trustworthy within information environments. When visibility becomes algorithmically mediated, creators and users may begin to interpret reach and engagement as indicators of legitimacy, influence, or personal value.

This produces a distinct form of institutional power. Platforms do not merely distribute attention; they indirectly shape reputational standing, perceived relevance, and symbolic status within digital communities. In this context, algorithmic visibility functions as a form of social classification that affects how individuals are seen by others and how they understand themselves.

The findings therefore suggest that algorithmic ranking systems operate not only as technical filters but as social sorting mechanisms that structure recognition, legitimacy, and participation. Harm in this domain does not arise solely from economic disadvantage or content suppression. It also emerges from the way platform infrastructures transform visibility into a proxy for credibility and worth, reshaping the social meaning of presence in digital life.

4.4. The Cross-Domain Logic of Algorithmic Power

Across recruitment, welfare administration, and digital platforms, automated systems operate in different institutional contexts, yet they generate structurally similar effects on how individuals encounter authority, opportunity, and recognition. Although the technical architectures vary, the underlying pattern remains consistent: decisions are produced at scale, delivered with limited explanation, and experienced as authoritative despite being difficult to interpret or contest.

In employment screening, automated filtering systems remove applicants from consideration without meaningful feedback, leaving individuals unable to determine the basis of exclusion [15,16]. In welfare contexts, automated eligibility or risk scoring systems produce classifications that claim administrative legitimacy but may conflict with lived circumstances [8,25]. On digital platforms, ranking systems shape visibility and reach without transparent justification, leading users to speculate about hidden rules or implicit penalties [18,19].

Across these domains, individuals tend to interpret automated outcomes not only as technical decisions but as institutional signals. Decisions are read as messages about employability, deservingness, credibility, or social relevance. This pattern appears repeatedly in public complaints, regulatory inquiries, platform governance research, and documented user responses. The shared feature is not simply the presence of automation, but the way automation reshapes how institutional judgement is communicated and understood.

Existing research often examines algorithmic systems within isolated sectors, focusing on bias in hiring, error in welfare automation, or moderation in platform governance. However, the cross-domain material analysed here suggests that automated systems produce a broader institutional transformation. Classification becomes faster, more standardised, and less dialogic. Explanation becomes more limited. Opportunities to contest or contextualise decisions become more constrained.

This shift alters how institutional power is exercised. Instead of judgement being communicated through interaction, deliberation, or narrative reasoning, it is increasingly expressed through categorical outputs such as acceptance or rejection, eligibility or denial, and visibility or suppression. Individuals must then interpret these outputs without access to the reasoning that produced them.

The evidence indicates that this transformation affects not only outcomes but also perceptions of legitimacy. When people cannot understand how a decision was made, they often struggle to determine whether it was fair, mistaken, biased, or indifferent. This uncertainty can weaken confidence in institutional processes, even when formal rules or technical safeguards exist.

Importantly, the cross-domain findings do not suggest that automated systems operate identically across sectors. Rather, they show that automation introduces recurring institutional dynamics: reduced transparency, expanded classification, constrained contestability, and greater distance between decision-makers and decision subjects. These dynamics help explain why automated systems can simultaneously improve administrative efficiency while generating new forms of frustration, mistrust, and perceived exclusion.

This section therefore identifies a unifying institutional pattern rather than a single technical failure. Automated systems increasingly function as intermediaries between individuals and institutions, shaping how decisions are produced, communicated, and interpreted. Understanding their impact requires attention not only to technical performance, but also to how automation transforms recognition, accountability, and the experience of institutional authority.

5. Interpretation: Automated Systems as Emerging Social Institutions

The findings across recruitment, welfare administration, and digital platforms point to a shared institutional transformation. Automated systems are no longer functioning merely as decision-support tools. They increasingly perform roles that were historically associated with institutional judgement, including classification, evaluation, prioritisation, and exclusion. Decisions that once relied on interpersonal reasoning and contextual discretion are now produced through rapid, standardised, and opaque computational processes.

This shift matters because it changes not only how decisions are made, but how authority is exercised and experienced. Prior research shows that automation redistributes discretion from frontline officials to technical infrastructures, altering internal power dynamics within organisations [1]. Comparable dynamics appear in welfare administration [8] and platform governance, where ranking systems perform functions once carried out by editors, caseworkers, or gatekeepers [2,3,9]. The present findings extend this literature by showing that automation also transforms how individuals interpret institutional decisions, how legitimacy is perceived, and how inequality is produced and justified.

Across domains, automated outputs are commonly treated as final, even when their reasoning is inaccessible. This creates a situation in which institutional authority is exercised without explanation, dialogue, or visible accountability. The result is not simply procedural change, but a reconfiguration of legitimacy, recognition, and public trust.

5.1. Automated Systems as Institutional Actors

Institutional theory suggests that authority emerges when outputs are routinely accepted as binding within formal decision processes [29]. Automated systems increasingly meet this condition. In recruitment, welfare, and platform environments, algorithmic decisions are acted upon as authoritative even when affected individuals cannot contest or interpret them.

This reflects what has been described as the cultural construction of automated authority, in which algorithmic outputs are framed as more neutral or objective than human judgement [13]. The evidence in this study indicates that automated systems derive their power not from transparency or technical superiority, but from institutional embedding. When organisations integrate algorithmic outputs into routine governance practices, the system effectively becomes the decision-maker.

Individuals tend to interpret automated outcomes as institutional verdicts rather than technical suggestions. Rejections, risk scores, and visibility shifts are experienced as judgments about competence, deservingness, or credibility. In this sense, automated systems do not simply serve institutional goals. They increasingly participate in defining what counts as merit, risk, relevance, or legitimacy. This represents a substantive expansion of algorithmic power beyond technical assistance into institutional governance.

5.2. The Emergence of Datafied Citizenship

Automated classification systems also reshape how individuals understand their relationship with institutions. Prior research suggests that algorithmic governance alters how citizens perceive what the state values and recognises [11]. The findings here indicate that this process extends beyond governance into everyday identity formation.

Across the analysed domains, individuals interpret automated classifications as signals about their social worth. In recruitment, exclusion becomes a marker of institutional non-recognition. In welfare contexts, risk scoring is read as a moral assessment of deservingness. On platforms, visibility becomes a proxy for credibility and social relevance. These interpretations emerge not from direct interaction with decision-makers, but from how algorithmic systems categorise and display individuals.

This aligns with arguments that inequality in automated systems operates through data-driven stratification rather than explicit discrimination [16]. Individuals increasingly encounter institutions through predictive profiles and behavioural inferences rather than interpersonal engagement. The concept of datafied citizenship captures this transformation: people come to understand their institutional standing through algorithmic categories that shape access to opportunities, recognition, and participation.

5.3. Trust as a Sociotechnical Relationship

Trust in institutional decision-making has traditionally depended on both procedural fairness and perceived recognition. Experimental studies indicate that people may initially accept automated decisions as credible even without understanding them [7]. However, evidence from welfare systems and digital platforms shows that this credibility weakens when automated outcomes conflict with lived experience or appear indifferent to personal context [2,3,18].

The findings suggest that trust in automated systems is not determined solely by technical accuracy or formal transparency. Instead, trust depends on whether individuals feel seen, understood, and acknowledged by the institution behind the system. Where automated processes eliminate relational cues, opportunities for explanation, or meaningful avenues for contestation, individuals interpret decisions as impersonal, arbitrary, or unjust.

This supports the view that legitimacy in automated governance depends on engagement rather than technical disclosure alone [24]. In the cases examined, distrust arises not simply because systems are opaque, but because they replace interpersonal accountability with impersonal classification. Trust therefore emerges as a sociotechnical relationship shaped by recognition, responsiveness, and institutional care, not merely by computational performance.

5.4. A Dual Logic of Inequality in Automated Societies