Abstract

This article examines digital inequalities in Italy through a sociological lens, arguing that the digital divide is not merely a technological issue but a manifestation of broader social stratification. Drawing on data from ISTAT (2023–2024), the analysis explores disparities in Internet access and computer use among families with minors and young people aged 6–24. While connectivity has reached near universality, significant territorial, educational, and social gaps persist, reflecting enduring inequalities in resources and opportunities. The study interprets these patterns through the framework of first-, second-, and third-level digital divides, linking them to theory of cultural capital and digital capital. Results indicate that inequalities extend beyond access, encompassing differences in digital skills, motivation, and the capacity to translate online participation into educational or social advantages. Gendered expectations further influence these dynamics, shaping distinct patterns of engagement with technology. The discussion highlights how digitalization acts as a mechanism of social reproduction, where access and competence are mediated by pre-existing disparities in education and culture. From a policy perspective, the paper calls for a shift from infrastructure-oriented strategies toward capability-based digital education that fosters critical, ethical, and future-oriented digital citizenship.

1. Introduction

| «As the digital divide understood as mere access to connectivity begins to close, |

| a deeper one emerges, concerning the opportunities for usage |

| and effective exploitation of digital networks, |

| which is likely to intensify social inequality». |

| (Van Dijk, 2005) [1] |

The rapid evolution of digital technologies has profoundly transformed how individuals learn, communicate, and participate in social, cultural, and economic life. In contemporary societies, access to and mastery of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have become fundamental prerequisites for education, full participation in the labor market, and civic engagement [2,3]. Digital competences are thus essential for individuals’ educational and professional development, influencing their ability to participate effectively in knowledge-based economies [4,5].

However, disparities in opportunities to access ICT resources and develop digital skills can exacerbate pre-existing inequalities, affecting students’ learning outcomes and their broader social mobility. Prior studies have identified significant disparities in digital access and usage among students of different genders and socioeconomic backgrounds, often described as digital gender divides [2,6,7,8,9,10]. These gaps indicate that the digitalization of education—rather than simply reducing inequalities—can, in certain contexts, reinforce them [11,12].

In Italy, this issue is particularly relevant. Despite significant progress in connectivity and digital infrastructure, national statistics reveal persistent territorial and socioeconomic gaps in both access to and mastery of digital tools [13]. These disparities reflect broader social inequalities, where education, income, and geography intersect to determine who benefits from digital transformation. Families and schools therefore play a crucial role as agents of digital socialization, shaping students’ opportunities to acquire and exercise meaningful digital competences [14,15].

In educational contexts, digital competence acts as a bridge between access and meaningful participation. It defines the ability to access, understand, and critically use digital tools for learning and civic engagement. This dimension is not only technical but also normative: according to Rawls’s principles of fair equality of opportunity and the difference principle, inequalities are acceptable only if social institutions are structured to benefit the least advantaged [16]. From this perspective, guaranteeing equitable opportunities to develop digital competences becomes an essential condition of educational justice.

This foundations aligns with the United Nations’ Agenda 2030, specifically Goal 4: Quality Education, which calls for inclusive and equitable access to quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all [17]. It also resonates with the European Commission’s Key Competences for Lifelong Learning framework, which identifies digital competence as a core skill for active citizenship [18]. However, despite the growing centrality of digital skills in education policy, empirical evidence continues to show persistent inequalities in both access and digital literacy, perpetuating broader patterns of social and educational disadvantage [12,19].

This paper examines how digital inequalities shape educational opportunities in Italy, with particular attention to disparities in access and gender within school and family contexts. It also explores how these patterns relate to broader social transformations and how the concept of future literacy can inform a more inclusive and anticipatory approach to digital education, promoting equity and participation across generations.

From Literacy to Digital Inequalities

The notion of literacy has progressively expanded beyond its traditional association with reading, writing, and basic numeracy to encompass a broader understanding of competence, the capacity to mobilize knowledge, skills, and attitudes for active participation in social, cultural, and economic life [20,21]. Within contemporary knowledge societies, literacy constitutes a central dimension of human development and agency, enabling individuals to navigate complexity and exercise autonomy in contexts characterized by rapid technological and informational change [22,23].

From a sociocultural perspective, literacy is not a neutral or purely technical skill but a socially situated practice embedded in relations of power and cultural reproduction [24]. It thus operates simultaneously as an individual capacity and as a form of social capital, shaping access to knowledge and opportunities for participation. In this view, literacy reflects broader social structures: the acquisition and exercise of such competences depend on the distribution of cultural and material resources within society. Educational institutions, for instance, play a decisive role in transforming these resources into learning advantages, often reinforcing rather than mitigating inherited [25].

Ensuring fair opportunities for individuals to develop and use literacy therefore requires not only equal access but also the reduction in structural disadvantages that hinder the full exercise of educational and digital rights [16]. In this sense, literacy represents both a tool for empowerment and a potential site of exclusion, depending on how social and institutional contexts distribute the means and motivations to acquire it. These dynamics extend into the digital sphere, where access to technology and the development of digital competences continue to mirror patterns of social stratification rooted in class, education, and geography.

As digitalization permeates everyday life, literacy has assumed new and overlapping forms: information, media, computer, and digital literacy, each describing specific yet interdependent dimensions of capability [18,26,27]. Together, they outline a continuum that ranges from basic operational proficiency (computer literacy), to the interpretation and evaluation of digital content (digital literacy), to the integrated mobilization of cognitive, social, and ethical skills in digital contexts (digital competence). Despite terminological variations across national and international frameworks [10,12,28], these concepts converge in defining literacy as the responsible and critical use of information and communication technologies for learning, creativity, and civic participation [3].

Recent models of digital competence also emphasize transversal abilities such as collaboration, problem-solving, ethical awareness, and digital citizenship [12,28,29]. Consequently, digital literacy can be understood as a composite and reflexive capability such as a constellation of technical, cognitive, and socio-ethical dimensions aligned with the competences required in 21st-century societies [30].

From a sociological standpoint, this evolution reveals how literacy itself functions as a stratified social resource. Individuals endowed with greater educational and cultural capital are better positioned to transform literacy into digital competence and, ultimately, into social and economic advantage. Digitalization thus reconfigures, rather than eliminates, traditional forms of inequality: access to knowledge remains unevenly distributed, mediated by differences in resources, values, and symbolic power that continue to define who benefits most from technological change.

2. First- and Second-Level Digital Divide: A Multi-Stage Perspective

Early studies on the digital divide conceptualized technological inequality primarily as a problem of access—that is, who has physical access to devices and connectivity [2,31,32,33]. This first-level divide was strongly correlated with socioeconomic status, education, and geography. As [31] argued, these disparities are not merely technological but reflect social inequalities in opportunity: families and schools endowed with greater economic and cultural capital offer richer technological environments, while disadvantaged contexts remain peripheral.

With the generalization of access, researchers began to highlight a second-level divide, concerning skills, uses, and purposes [1,11,34,35]. Attewell [31] distinguished between simple and enriching uses, noting that digital technologies may reinforce or mitigate inequalities depending on how they are employed. Similarly, Hargittai [35] and van Deursen and van Dijk [36] identified differences in online skills and usage quality linked to education, age, and social background. These contributions mark a shift from access to effective use, showing that digital inequalities are rooted in broader social structures.

More recent research introduced a third-level digital divide, focused on the outcomes of digital engagement: how individuals translate access and skills into tangible educational, economic, or civic benefits [12,37,38,39]. Across these three levels, inequalities accumulate and this means that those with more resources, support, and competences not only access technologies earlier but also derive greater returns from their use.

Building on this multi-level understanding of digital inequalities, the notion of digital capital [38,40] offers a conceptual synthesis that integrates the first, second, and third levels of the digital divide. Rooted in the Bourdieusian framework of capital accumulation and conversion, digital capital captures how access to technology and the mastery of digital skills become resources that can be accumulated, transmitted, and transformed into other forms of advantage. This perspective can be extended to the digital field, where access to and use of technology operate as new forms of cultural and social capital.

As Bourdieu [41] conceptualized, capital represents “the set of actually usable resources and powers” that shape individuals’ life opportunities. He expanded Marx’s economic view by including symbolic and cultural dimensions of capital—resources that are scarce, socially valued, and convertible across social fields [42]. Extending this logic, digital capital consists of both internalized abilities (digital competences such as information management, communication, content creation, safety, and problem-solving) and externalized resources (access to digital technologies and infrastructures). These resources, like other forms of capital, are historically accumulated and can be transferred or converted into economic, social, or cultural advantages.

From this perspective, digital capital functions as a mediating mechanism between social background and digital inequality. The amount of digital capital that individuals possess shapes both the quality of their Internet experience (that is, their position within the second-level divide) and the conversion of digital engagement into broader life outcomes, corresponding to the third-level divide) [43]. The continual accumulation and transmission of digital capital, however, tend to preserve existing social inequalities, mirroring the processes of reproduction theorized by Bourdieu and Passeron [25].

Empirical studies confirm the strong association between education and digital capital formation. Higher educational levels consistently predict greater access, engagement, and diversity of online activities [10,31,44,45,46]. Recent analyses [47] found that education significantly and positively influences individuals’ accumulation of digital capital, confirming that digital inequalities remain deeply tied to educational stratification. Similar findings in the Netherlands [10] and England [48] reinforce the conclusion that differences in schooling and digital competence are mutually reinforcing. Moreover, age-related disparities [49] indicate that digital capital also varies across generations, with older adults often disadvantaged by lower confidence and digital engagement.

In this sense, digital capital bridges the gap between structural inequalities and individual capabilities, providing a comprehensive framework to interpret how social advantages—particularly those related to education and cultural capital—are reproduced in the digital sphere. By integrating the notions of capital accumulation, transferability, and conversion, digital capital redefines the digital divide not merely as an issue of access or skills, but as a process of social stratification in the digital age.

3. Gender Digital Divide

Gender represents one of the most persistent dimensions of digital inequality, shaping both access to ICT resources and the ways technologies are used and valued. Research identifies multiple and interconnected levels of this divide [50], reflecting broader social and cultural patterns that structure opportunities in education and work.

The first-level gender digital divide concerns disparities in access to technological devices and connectivity. Several studies indicate that boys tend to have earlier and more autonomous access to computers and digital tools, both at home and at school, compared with girls [51]. Although this gap appears to be narrowing as digital infrastructures expand [2], subtle but meaningful differences persist in the quality and context of technological exposure. Access to ICT resources outside formal education, within the family or through extracurricular activities, plays a crucial role in shaping students’ familiarity and confidence with digital tools, thereby influencing their learning trajectories.

Beyond access, gendered differences emerge in the affective and motivational dimensions of technology use. Girls often report higher levels of computer anxiety and lower enjoyment in technology-related tasks than boys [52,53,54], reflecting long-standing processes of gender socialization that associate technical competence with masculinity. These dynamics are reinforced by cultural representations that, from childhood, differentiate what is “for boys” and “for girls”: for instance, Bucchetti [55] shows how the design and communication of STEM-related toys rely on visual and linguistic codes that target male audiences and reproduce gender stereotypes.

The second-level gender digital divide, focusing on differences in digital skills and uses, presents a more complex picture. Boys tend to excel in technical and problem-solving tasks [56], whereas girls often perform better in activities involving communication, collaboration, and learning management [5,9]. A large-scale meta-analysis by Siddiq and Scherer [9] found that, on average, girls slightly outperform boys in performance-based assessments of ICT literacy, although the direction of the gap varies across age groups and national contexts. Nevertheless, girls frequently report lower confidence in their digital abilities despite equal or superior performance [6,57], suggesting that gender differences are as much psychosocial as they are technical.

Online behavior mirrors—and in some cases amplifies—offline gendered norms. Women are more likely to use the Internet for communication and social support, while men employ it more often for informational or instrumental purposes [58], then online practices are extensions of broader social roles and expectations, and the symbolic gendering that structures offline interactions often reappears, sometimes in exaggerated forms, in digital environments [59].

Within this broader structure, the notion of digital capital offers a powerful lens for understanding gendered digital inequalities. Drawing on Bourdieu’s [41] conceptualization of capital as a set of scarce and socially valued resources that can be accumulated and converted, Ragnedda [38] interprets digital capital as comprising both internalized abilities and attitudes—such as confidence and competence—and externalized resources, such as technological access and connectivity. Gender differences influence both the accumulation and conversion of this capital: an empirical study, observed that men display slightly higher levels of digital capital [47], a result consistent with earlier analyses linking gender to differential access to social and technical capital [44,60].

Recent Italian research provides further nuance. Papa and Desimoni [14] found that adolescent males are more likely to own and use desktop computers, whereas females tend to possess laptops and tablets; when considered together, the ownership gap nearly disappears. However, Patti and Schifilliti [15] report that boys engage more frequently in gaming and technical tasks, while girls use digital tools primarily for communication and learning. These findings suggest that the gender digital divide has shifted from a question of access to one of use, confidence, and social meaning.

Overall, gendered expectations continue to influence how young people approach technology, shaping the accumulation of digital capital and, consequently, their educational and professional trajectories. Digital inequalities therefore appear not as isolated technical disparities but as socially and culturally embedded phenomena, sustained by the symbolic and institutional dynamics of the educational system.

4. Methodology

This study adopts a descriptive and explanatory approach [61,62] to interpret national data on digital competences through the conceptual lenses of digital capital and the gender digital divide. The goal is not to produce new empirical data, but to reinterpret existing evidence to understand how social and educational inequalities are reproduced in the digital sphere.

The analysis is based on the ISTAT (2023–2024) “Cittadini e ICT” survey, which provides official national data on Italians’ access to and use of information and communication technologies. For the purposes of this study, data were filtered to include families with at least one minor and individuals aged 18–24, in order to capture both intergenerational and youth-specific patterns of digital participation within educational contexts. Variables related to gender, age, and regional distribution were selected to explore how digital competences and access differ across social and territorial dimensions.

The descriptive graphs presented in the paper were created using the interactive data visualization tools available on the ISTAT. The resulting visualizations were exported from the ISTAT portal and refined using Microsoft Excel (2023).

5. Results

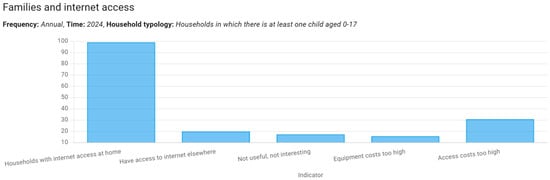

The descriptive analysis of ISTAT open data (2023–2024) highlights persistent though evolving patterns in digital access and usage across Italian households and individuals. The first level of the digital divide—access to Internet and technological infrastructures—shows substantial diffusion but enduring territorial and socioeconomic disparities. In 2024, 99.1% of families with at least one minor have Internet access at home, compared to 86.9% in the North-West, 88.8% in the North-East, and 82.6% in the South (Figure 1). Households in metropolitan areas report the highest access rates (89.6%), while smaller municipalities (under 2000 inhabitants) remain below 83%. The main barriers to Internet adoption continue to be the perceived lack of usefulness (23–27%), the high cost of connection (up to 30.8%), and insufficient digital skills within the household (55–64%). These data confirm that the digital divide in Italy still mirrors structural social inequalities, where economic, educational, and geographical factors jointly shape opportunities for digital inclusion.

Figure 1.

Our elaboration based on ISTAT (2024) data. Y-axis: Percentage of households.

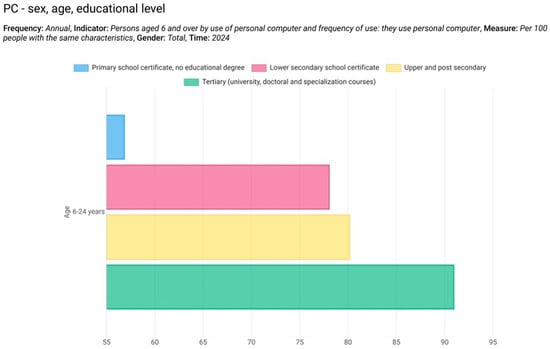

The second level of digital inequality—related to skills and use—was explored through indicators of computer utilization by gender, age, and educational level. Among individuals aged 6–24, 72.7% of females and 68.8% of males reported using a personal computer, with daily use declared by 32.7% of girls and 31.5% of boys. Non-users represent about one quarter of respondents in both groups (25.8% among females, 29.5% among males), revealing that a relevant minority of youth still lacks regular access to digital tools. Educational attainment remains strongly associated with digital engagement: the probability of using a computer increases progressively from those with a lower-secondary certificate (approximately 76%) to those with a university degree (close to 90%). These findings are consistent with international evidence that links digital competence to educational and occupational status, confirming that access alone does not ensure effective digital participation.

Further insights into online activities and learning behaviors provide a complementary picture of how young people use digital technologies (Figure 2). Data from ISTAT (2024) indicate that among individuals aged 6–24, over 85% regularly use instant messaging services and video calls, around 70% watch video content, and nearly half engage in social networking or information searching. However, only 25–30% report having participated in online educational or training activities over the past year. Gender differences appear modest overall, but a subtle specialization emerges: young women tend to use digital media more for communication and social interaction, whereas young men are slightly more engaged in content production and technical-oriented uses. This differentiated pattern reflects not only distinct interests but also the unequal conversion of access and skills into digital capital. While the widespread use of the Internet among youth signals progress in narrowing the first-level divide, the persistence of educational, gendered, and territorial gaps underscores the relevance of structural inequalities that continue to shape Italy’s digital landscape.

Figure 2.

Our elaboration based on ISTAT (2024) data. Y-axis: Percentage of individuals.

6. Discussion

The findings confirm that while Internet access among Italian families with minors has reached near universality, meaningful digital inclusion remains unequally distributed along social, educational, and territorial lines. Access to technology is not merely a technical condition but a socially mediated process shaped by the unequal distribution of material and cultural resources [1,12]. According to ISTAT data (2024), almost all households with at least one minor are now connected to the Internet, yet regional disparities persist, particularly between northern and southern regions, alongside differences associated with parents’ educational attainment and occupational status. Connectivity thus follows existing social hierarchies rather than overcoming them, indicating that the expansion of access alone does not guarantee equality of participation.

The reasons reported by families who remain offline reveal the persistence of first-level digital inequalities, which are as much cultural as infrastructural. Many cite a lack of digital skills or the perception that the Internet is not useful, highlighting motivational and cognitive barriers rather than purely material ones. As Hargittai [35] and Van Dijk [1] note, the digital divide is multidimensional, encompassing motivational, cognitive, and social dimensions. Families with limited digital familiarity are more likely to self-exclude, thereby reinforcing cycles of marginalization [63]. In line with Bourdieu’s [41] concept of cultural capital, digital participation depends not only on the possession of technological devices but also on the symbolic and educational resources that enable individuals to transform access into meaningful practices. Families with higher educational attainment and stronger learning orientations tend to foster more active and competent uses of digital media, transmitting both technical and cultural forms of digital capital to their children.

Empirical research within the Italian context supports this interpretation. Gui [64] demonstrated that students whose parents hold university or upper-secondary degrees are significantly more likely to use the Internet for informational and educational purposes than peers from less educated families. This confirms that the quality of online engagement is socially stratified: what the literature terms “capital-enhancing” uses of the Internet are more prevalent among privileged groups, reinforcing intergenerational advantages. Similarly, Papa and De Simoni [14] found that a clear digital divide persists between students from disadvantaged and more affluent households, not only in terms of personal computer ownership but across a variety of digital devices. These patterns illustrate the structural nature of digital inequality, which reflects socioeconomic status rather than technological availability [65,66].

The second level of the digital divide, concerning digital skills and uses, further demonstrates that inequality extends beyond access. Among youth aged 6–24, ISTAT data (2024) reveal that although more than two-thirds regularly use a computer, nearly one in four do not. Gender differences, though moderate, suggest differentiated patterns of engagement: while there is no significant gap in general access or ICT use between male and female students, males are more likely to use gaming consoles, whereas females favor communicative and collaborative uses of the Internet [14]. These differences point to the social meanings and purposes attached to technology, rather than to disparities in connectivity [67]. From a sociological perspective, such findings illustrate how digital inequalities function as mechanisms of social reproduction. As Bourdieu [41] argued, initial disadvantage, such as limited access or lower digital competence, tend to accumulate over time, influencing students’ educational trajectories and future opportunities. Similarly, the knowledge gap hypothesis [68,69] suggests that information dissemination through media and digital channels disproportionately benefits those already advantaged, as individuals with higher education possess stronger communication skills, prior knowledge, and motivation to seek information. Education and motivation thus interact as mutually reinforcing factors, widening informational and cultural gaps over time.

These cumulative dynamics prepare the ground for the third-level digital divide, which concerns the unequal capacity to transform digital engagement into tangible outcomes in learning, participation, and social mobility [1,47]. Even when individuals possess similar access to technology and comparable levels of digital competence, their ability to convert such resources into educational or social advantages depends on the structural and cultural contexts in which they are embedded. Data from ISTAT (2024) support this interpretation: although the majority of young people in Italy access the Internet daily, only a minority use it for educational or training purposes. This suggests that the current challenge is no longer primarily technological but functional and interpretive, linked to how individuals appropriate digital tools to produce value, acquire knowledge, and expand future opportunities. Those endowed with higher levels of digital capital are better positioned to transform online participation into empowerment and learning, whereas others remain confined to passive or recreational forms of use. In this sense, digital inequality not only reflects but also amplifies pre-existing social disparities.

Within this framework, digital capital functions as a bridge between structural conditions and individual outcomes, integrating access, skills, and the ability to mobilize digital networks for social and economic benefit [38]. Yet, consistent with Bourdieu’s [41] theory of capital conversion, such resources are unevenly accumulated and transformed: those with greater educational and cultural capital are more likely to reinvest digital advantages into further social benefits. Addressing this recursive process requires moving beyond infrastructure- and skills-based interventions toward capability-oriented digital education [70].

From a policy perspective, the reduction in digital inequalities calls for a paradigm shift, from connectivity to capability building. In the Italian context, the Piano Nazionale Scuola Digitale [71] and its evolution, the Piano Scuola Futura [72], represent important steps toward integrating digital technologies into education. However, as emphasized by the OECD [2], these initiatives must increasingly prioritize critical engagement, equity, and social inclusion, ensuring that digital education contributes to democratic participation and personal development rather than merely technical proficiency [73].

In line with the European Commission’s DigCompEdu [74] and Key Competences for Lifelong Learning [18] frameworks, as well as UNESCO’s Futures of Education [27], future digital education strategies in Italy should:

- Integrate critical, civic, and future-oriented competences across all educational levels;

- Family and community involvement in digital learning processes;

- Evaluate digital education not only by access or skills, but by its contribution to well-being, empowerment, and inclusion.

Within this broader vision, future literacy [75,76] offers a valuable framework for transformation. It emphasizes the capacity to anticipate, reflect on, and act upon emerging futures: these skills, when applied to digital contexts, foster critical awareness, ethical reasoning, and reflexive technology use. Embedding future literacy in digital education supports learners in evaluating information sources, recognizing algorithmic biases, and understanding the social construction of digital systems. These competences are essential to converting digital participation into empowerment and agency, the core outcomes at stake in the third-level digital divide [12].

Ultimately, bridging digital inequalities requires more than universal access: it demands the cultivation of critical and anticipatory digital citizenship, enabling individuals to consciously and collectively shape technological change. Ensuring that digital inclusion becomes both a right and a capability is therefore not only a matter of educational policy but a cornerstone of social justice and sustainable development in the digital age.

7. Conclusions

Digital inequality unfolds across multiple and interconnected levels (access, skills, and outcomes) each representing a distinct yet cumulative dimension of social stratification [1,35]. Understanding these levels requires shifting the analytical focus from technology to the social processes of mediation that condition how individuals and groups engage with digital environments. Inequality, in this sense, cannot be reduced to the absence of infrastructure or the inadequate supply of online content; it is instead a structural phenomenon, embedded in patterns of education, occupation, and cultural capital that shape people’s capacity and motivation to participate meaningfully in the digital sphere [68]. Non-use of the Internet, therefore, is not simply a matter of ignorance or indifference but often a rational choice within social contexts constrained by limited opportunities and resources. Even as overall Internet adoption rises, significant gaps persist regarding how and for what purposes people use digital technologies, differences that reflect enduring asymmetries in power, knowledge, and social position.

Within this broader framework, the Internet functions simultaneously as a networking tool and a mechanism of social reproduction. While designed to connect individuals and foster interaction, digital participation often mirrors the unequal distribution of social capital, amplifying pre-existing hierarchies. The benefits that derive from relational power that is, from the quality and usefulness of one’s social ties in cultural, economic, or political domain, depend on how effectively individuals can leverage digital media to create and sustain networks [40]. Online engagement may indeed strengthen social capital, producing advantages in employment, education, and personal development, yet such outcomes presuppose both access and the acquisition of diverse competences (technical, social, critical, and creative) together with the motivation to use them strategically. The qualitative experience of Internet use, corresponding to the second level of the digital divide, thus becomes a crucial mediating factor that determines who can convert digital participation into meaningful social or economic returns, defining the third level of inequality.

This multidimensional perspective underscores how digitalization acts as a social amplifier rather than an equalizer. It extends opportunities for those already endowed with cultural and material resources, while offering limited transformative potential to individuals facing structural disadvantages. Addressing these recursive mechanisms requires policy approaches that move beyond mere infrastructural expansion and focus instead on capability building and developing digital competences, critical awareness, and participatory motivation through inclusive educational and community initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and M.C.S.; methodology, E.M. and M.C.S.; formal analysis, M.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.S.; writing—review and editing, M.C.S. and E.M.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, E.M.; funding acquisition, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the University Project “Futures studies to observe society, science and technology and promote social and economic benefits”, approved by resolution of the Academic Senate of the Giustino Fortunato University, dated 11 September 2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Van Dijk, J. The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Siddiq, F.; Hatlevik, O.E.; Olsen, R.V.; Throndsen, I.; Scherer, R. Taking a future perspective by learning from the past—A systematic review of assessment instruments that aim to measure primary and secondary school students’ ICT literacy. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 19, 58–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Hmelo-Silver, C.E. Seven affordances of computer-supported collaborative learning: How to support collaborative learning? How can technologies help? Educ. Psychol. 2016, 51, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Hong, J.; Song, H. The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in digital learning performance. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2018, 66, 1109–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.; Fan, X.; Du, J. Gender and attitudes toward technology use: A meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2017, 105, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J. The digital divide: The special case of gender. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2006, 22, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, A.; van Deursen, A.; van Dijk, J. Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second- and third-level digital divide. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1607–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, F.; Scherer, R. Is there a gender gap? A meta-analysis of the gender differences in students’ ICT literacy. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 27, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.; van Dijk, J.A. The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media Soc. 2013, 16, 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Hargittai, E. From the “Digital Divide” to “Digital Inequality”: Studying Internet Use as Penetration Increases; Princeton University, Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, E.J. The Digital Disconnect: The Social Causes and Consequences of Digital Inequalities; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. Cittadini e ICT 2024; Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/2024+cittadini+e+ICT (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Papa, D.; Desimoni, M. Tackling the digital divide: Exploring ICT access and usage patterns among final-year upper secondary students in Italy. Ital. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 32, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, A.; Schifilliti, V. Keep up with the modern joneses: An empirical analysis of the digital divide in Italy. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 32, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice, Rev. ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- European Commission. Council Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (2018/C 189/01); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2018; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/291008 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Goudeau, S.; Sanrey, C.; Stanczak, A.; Manstead, A.; Darnon, C. Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castoldi, M. Valutare le Competenze; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pellerey, M. Le competenze Individuali e il Portfolio; La Nuova Italia: Firenze, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bennato, D.; Vitale, M.P. Trasformazione Digitale e Competenze per la Network Society. Contesti, Saperi Eprofessioni Emergenti Nelle Scienze Umane e Sociali; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Understanding the Digital Divide. In OECD Digital Economy Papers; No. 49; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzato, M. Literacy e complessità. TD Tecnol. Didatt. 2013, 21, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.C. Les heritiers. In Les Etudiants et la Culture; Les Editions de Minuit: Paris, France, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A. Digital Competence in Practice: An Analysis of Frameworks. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012; Volume 10, p. 82116. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aesaert, K.; van Braak, J. Gender and socioeconomic related differences in performance based ICT competences. Comput. Educ. 2015, 84, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatlevik, I.K.R.; Hatlevik, O.E. Examining the Relationship Between Teachers’ ICT Self-Efficacy for Educational Purposes, Collegial Collaboration, Lack of Facilitation and the Use of ICT in Teaching Practice. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraillon, J.; Schulz, W.; Ainley, J. International Computer and Information Literacy Study: Assessment Framework. 2013. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/ict_literacy/9 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Attewell, P. The first and second digital divides. Sociol. Educ. 2001, 74, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wellman, B. The Global Digital Divide. IT Soc. 2004, 1, 39–45. Available online: http://www.ITandSociety.org (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Guillén, M.F.; Suárez, S.L. Explaining the global digital divide: Economic, political and sociological drivers of cross-national internet use. Soc. Forces 2005, 84, 681–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucy, E.P. Social Access to the Internet. Int. J. Press. 2000, 5, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E. Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills. First Monday 2002, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J.; van Dijk, J.A. Using the Internet: Skill related problems in users’ online behavior. Interact. Comput. 2009, 21, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Digital Divide? Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M. Conceptualizing digital capital. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warschauer, M. Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, A.M.L. Social Capital and the Three Levels of Digital Divide; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatow, G.; Robinson, L. Pierre Bourdieu: Theorizing the digital. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, M.L. Digital Capital: A Bourdieusian Perspective on the Digital Divide; Emerald Group Publishing; Howard House: Wagon Lane, UK; Bingley, UK; Leeds, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, G.; Groselj, D. Examining Internet use through a Weberian lens. Int. J. Commun. 2015, 9, 2763–2783. Available online: http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3114 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Clark, C.; Gorski, P. Multicultural education and the digital divide: Focus on socioeconomic class background. Multicult. Perspect. 2002, 4, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.; Selwyn, N. Moving on-line? An analysis of patterns of adult Internet use in the UK. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2011, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M.; Ruiu, M.L.; Addeo, F. Measuring Digital Capital: An empirical investigation. New Media Soc. 2019, 22, 793–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, G.; Groselj, D. Dimensions of Internet use: Amount, variety, and types. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2014, 17, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-Y.; Qiu, J.L.; Kim, Y.-C. Internet Connectedness and Inequality: Beyond the “Divide”. Commun. Res. 2001, 28, 507–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J. The Digital Divide; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broos, A. Gender and information and communication technologies (ICT) anxiety: Male self-assurance and female hesitation. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2005, 8, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durndell, A.; Haag, Z. Computer self efficacy, computer anxiety, attitudes towards the Internet and reported experience with the Internet, by gender, in an East European sample. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2002, 18, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, A.; Comber, C. Age and gender differences in computer use and attitudes among secondary school students: What has changed? Educ. Res. 2003, 45, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchetti, V. Cattive Immagini: Design Della Comunicazione, Grammatiche e Parità di Genere; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarakainen, M.-T.; Kivinen, A.; Kaarakainen, S.-S. Differences between the genders in ICT skills for Finnish upper comprehensive school students: Does gender matter? Semin. Net. 2017, 13, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekiri, I.; Chronaki, A. Gender issues in technology use: Perceived social support, computer self-efficacy and value beliefs, and computer use beyond school. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R.; Jelenewicz, S.M. A disappearing digital divide among college students? Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2006, 24, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L. The cyberself: The self-ing project goes online, symbolic interaction in the digital age. New Media Soc. 2007, 9, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Zavodny, M. Digital inequality: A five country comparison using microdata. Soc. Sci. Res. 2007, 36, 1135–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 15th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gui, M. Formal and substantial Internet information skills: The role of socio-demographic differences on the possession of different components of digital literacy. First Monday 2007, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M. New patterns of digital inequality among adolescents: Evidence from three surveys in Nothern Italy. Quad. Sociol. 2015, 69, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, E. Settlement in the Digital Age: Digital Inclusion and Newly Arrived Young People from Refugee and Migrant Backgrounds. Centre for Multicultural Youth. 2017. Available online: https://www.cmy.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Settlement-in-the-digital-age_Jan2017.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Vassilakopoulou, P.; Hustad, E. Bridging digital divides: A literature review and research agenda for information systems research. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, A.; Maltby, J. Impact of the Internet on our lives: Male and female personal perspectives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 24, 2005–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfadelli, H. The Internet and Knowledge Gaps. Eur. J. Commun. 2002, 17, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichenor, P.J.; Donohue, G.A.; Olien, C.N. Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opin. Q. 1970, 34, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- MIM. Piano Nazionale Scuola Digitale; Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- MIM. Piano Scuola Futura; Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boeskens, L.; Meyer, K. Policies for the digital transformation of school education: Evidence from the Policy Survey on School Education in the Digital Age. In OECD Education Working Papers; No. 328; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators (DigCompEdu); Publications Office of the European Union: Seville, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. Introduction. In Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century; Miller, R., Ed.; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Poli, R. The challenges of futures literacy. Futures 2021, 132, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).