1. Bodies in the Frame: The Esthetics of Fashion and Identity

The current historical era is characterized by the predominance of sight as the sense that directs human perception, both individual and collective. The esthetic dimension, which not only includes the attractiveness of places and objects, but also the people around us, both in its in-person reception and in its media-mediated form, has therefore assumed an increasingly decisive role in the success of social relations [

1] (pp. 524–559).

This emphasis on visuality reconfigures the body itself as a site of performance and display, mediated through culturally encoded esthetics [

2]. Attractiveness, excluding a peculiar category that includes a fascination with the grotesque, the macabre, and the ugly, is typically associated with beauty, a concept that has strong social implications, anchored in time and space, and traditionally defined and normed.

In terms of human beauty, the 18th and 19th centuries in the West specifically saw a clear overlap—of very ancient origin—between beauty and standardization, exemplified in the concept of the ‘ideal’: something to strive for or to try to conform to, but which is, by its very nature, unobtainable [

3] (pp. 207–228).

Since the 1970s, the very conception of the West has been constantly redefining itself through its relationship with what it excludes or identifies as other [

4]. Here, the concept of the West is being used critically, not as a fixed geographical or cultural category, but as an historical and discursive construct. Critical reflections on Orientalism—a phenomenon similar in several respects to Occidentalism—reveal how Western identity has often been shaped by such oppositional narratives [

5]. In this sense, the ideal of Western beauty referred to in this work is to be understood as part of a broader esthetic regime rooted in Euro-American modernity, whose norms have become influential globally through processes of cultural and media circulation—and domination [

6,

7].

Over time, this ideal was not only aspirational, but disciplinary, institutionalized through esthetic regimes that made individuals feel responsible for attaining culturally sanctioned appearances. Moreover, the past few decades have seen a surge of globalized imagery, where the media—particularly in fashion and cosmetics—have predominantly showcased individuals with similar body types. These representations have contributed to what can be understood as the ‘formatted body’, a standardized corporeal template promoted by globalized fashion and media industries, privileging traits associated with youth, slimness, athleticism, and whiteness. This has resulted in a delicate and controversial balance between local and global trends and desires [

8] (pp. 1–19).

The most proposed and sought-after traits are not only more common in Western Caucasian populations, but are also linked to transversal values that represent the societies within which they develop: able and athletic bodies are perceived as ‘healthy’ and ‘young’, following the myth of eternal youth and immortality. Such bodies are not neutral, but are socially constructed, and are thus inscribed with social meaning and mobilized as visual capital within global fashion discourses. As far as gender is concerned, women in particular are still expected to conform to a certain degree of desirability linked to what has been called ‘the male gaze’ [

9], but we increasingly see how masculinity is also being challenged, criticized, and renegotiated in its representations of beauty.

However, although global body and beauty standards have become more universal, they are neither fixed nor unchallenged. Alternative body forms, often promoted through new media platforms, challenge the traditional representations seen in older, more centralized media outlets. These digital platforms facilitate embodied resistance, a set of practices through which non-normative bodies assert agency, diversify beauty standards, and destabilize hegemonic representations [

10] (pp. 153–159). Yet even here, resistance is not immune to appropriation. As fashion and media industries respond to calls for inclusion, difference itself is increasingly styled, packaged, and sold.

This dynamic points to a third crucial concept: the commodification of inclusion [

11] (pp. 309–323). Diversity, once framed as a challenge to hegemonic esthetics, risks becoming a consumable esthetic in its own right, stripped of its political potential and reintegrated into existing market logics. Fashion thus stages alterity while reaffirming hierarchies of desirability and visibility.

Within this framework, the media operates as a pivotal site for interrogating the tension between codified esthetic ideals and practices of embodied resistance. Although digital platforms have expanded the range of representational possibilities, legacy media, and notably fashion print magazines, still act as loci of bodily representation. Their continued centrality not only renders them as relevant, but also as essential objects of critical investigation.

2. The Cultural Work of Fashion Magazine Covers

Historically, fashion magazines have played a central role in the formation of socio-cultural imaginaries [

12] (pp. 15–52), using visual and textual codes to construct and disseminate aspirational ideals [

13] (pp. 37–57). Roland Barthes [

14] (1967) argued that fashion journalism is not merely a medium for reflecting trends, but also a process that actively constitutes the idea of fashion itself. The covers, in particular, function not only as commercial tools, but also as cultural artefacts that reflect and shape social values, politics, and esthetics. Through a calculated blend of typography, colour, styling, and facial expression, they project ideals that readers may internalize, aspire to, or resist, thereby participating in an ongoing dialogue between media, identity, and culture. By merging editorial judgement with semiotic and symbolic elements, they encapsulate the multifaceted narratives and societal aspirations of fashion, influencing both the formation of individual identities and collective imaginaries [

15,

16] (pp. 83–108).

For example, Vogue’s September 2018 cover, featuring Beyoncé photographed by Tyler Mitchell—the first Black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover—was more than a celebration of beauty and celebrity; it represented a deliberate disruption of traditional fashion hierarchies. The choice of subject, photographer, and esthetic conveyed messages about race, representation, and power in the fashion world. Similarly, Dazed and i-D magazine covers often challenge conventional beauty standards by featuring androgynous models, non-Western fashion narratives, or subcultural references, thereby expanding the boundaries of who and what is deemed fashionable.

These examples illustrate how fashion magazines have increasingly functioned as cultural sites where issues of identity, power, and representation are negotiated. While such shifts toward inclusivity have extended beyond race and gender to encompass religious forms of bodily expression, this dimension lies outside the scope of the dataset analyzed in this study. However, it is important to note that, in recent years, this diversification has also involved religious forms and their techniques of bodily embodiment. For instance, models wearing the hijab have become a more common sight on the covers of international editions of

Vogue [

17]. Once mainly considered a symbol of modesty [

18], the hijab has been reinvented as a means of expressing esthetics and politics, negotiating both belonging and modernity in Muslim and Western contexts [

19,

20]. However, to date,

Vogue Italia has not editorialized models wearing the hijab on its covers, thus demonstrating the ongoing tension between inclusion and cultural selectivity.

When it comes to body representation, although much of the existing literature has analyzed the content of fashion magazines, covers have received comparatively less attention. When studied, they are often treated as auxiliary tools for understanding gendered representations or consumer engagement strategies [

21] (pp. 647–655) [

22] (pp. 47–94). In addition, much of the existing literature on fashion covers—and fashion magazines more broadly—has traditionally focused on global or central publications, often overlooking more localized editions. Analyses have tended to privilege flagship magazines like

Vogue US, using it as a proxy for Western culture at large [

23,

24] (pp. 65–78). This perspective fails to account for the fact that local fashion magazines have not necessarily reflected local fashion systems, but have instead functioned as localized entry points into the inherently global discourse of fashion communication.

To address these gaps,

Vogue Italia was selected as a case. Its role, alongside that of Italian designers, in setting global standards for esthetics, creativity, and production it is known and recognized [

25] (pp. 632–648). Although it historically cultivated a distinct editorial voice and esthetic—often diverging significantly from its American counterpart—this uniqueness has increasingly diminished in recent years. The ongoing standardization of global markets and the consolidation of media ownership have contributed to the homogenization of content. As a result, the editorial specificity that once characterized magazines like

Vogue Italia is being eroded in favour of a more uniform, globally orientated approach. This raises critical questions: How have representations of ethnic, age, and body diversity evolved within this shifting terrain? To what extent do such representations reveal underlying tensions between globalized esthetic logics and local cultural contexts?

The research presented here pursues a twofold objective: First, it positions magazine covers as strategic visual dispositifs that actively participate in the social construction of the body, negotiating tensions between inclusion, exclusion, and commodification. Second, it examines the role of Vogue Italia as a cultural agent that both reflects and shapes social values, norms, and aspirations on a global scale over time. Through its covers, one can trace evolving imaginaries of the body, beauty, identity, and inclusion, as well as the interplay between global standardization and local particularities in the articulation of fashion.

3. Ongoing Narratives in Fashion Magazines

3.1. Gender Representation and Traditional Fashion Communication

Since their emergence, fashion magazines have contributed substantially to the definition of canons of beauty and gender roles. This is especially true if we consider the impact of the narratives proposed by fashion magazines on the education of middle- and upper-class women and girls, mainly in the West, and on the broader definition of what beauty means, what it means to be a woman, and what counts as role models. In this scenario, Vogue exerts significant influence precisely because of its specific readership: its power to transmit values, ideas, esthetic canons, and social norms is inseparable from the social and cultural positioning of its target audience.

In the history of Italian culture, costume, and fashion,

Vogue Italia has visually and materially represented the evolution of society, and, during the editorial era of Franca Sozzani (1988–2016),

Vogue Italia was transformed into a space for critical and political reflection, not only on the role of those women—as mentioned above, belonging to a privileged segment of the population—and fashion in society, but also on the contradictions that animate fashion and, more generally, on the processes of production, consumption, and representation in relation to the environment, the body, race, and gender [

26] (pp. 125–132).

The relationship between fashion and gender is an inextricable link between representations of the body and beauty. Vogue has contributed to the spread of esthetic and beauty models and norms, emphasizing both fashion and femininity in all its conflicting expressions: the desire for newness and youth, but also its consequences for health (see the iconic ‘Makeover Madness’ cover, July 2005) and the Earth (see ‘The Last Wave’ cover, August 2010). The covers of Vogue Italia from the 2000s onwards therefore seem to reveal aspects of reflection that, together with movement and citizen demands, have contributed to a more committed redefinition of fashion communication’s role in society. In this sense, by questioning canons about body, gender, age, and race, the covers reveal the adoption of more plural and inclusive narratives.

Thus, the first consideration in this analysis is related to the representation of gender by examining how, within fashion, it has changed and continues to evolve towards greater gender inclusiveness.

Vogue has always promoted strength, independence, and female empowerment, privileging the representation of the body over that of the face, beginning with the first cover by Steven Maisel, under the direction of Franca Sozzani. This was the case with

Vogue Italia from 1964 to 1988, and it remains still a theme and homage to the past in the more contemporary covers [

16] (pp. 83–108). However, in recent years, the reinterpretation of the representation of the male body in relation to the female body, as well as the even more recent attempt to go beyond gender, has been prompted by the growing demand from an increasingly sensitive public for plurality in the representation of the body and gender.

3.2. Race Representation and Traditional Fashion Communication

The most recent developments in fashion media stand in stark contrast to the traditional trajectory in which beauty standards were often shaped by locally determined canons specific to Indigenous cultures [

27] (pp. 41–74). Although local beauty standards have certainly not disappeared, the rise of globalization has seen the widespread dissemination of Western ideals, especially through media, which have significantly influenced beauty standards worldwide. The media has played a central role in promoting Western esthetics, incorporating these standards into various cultures, often eroding indigenous beauty norms in the process.

Traits such as high eyebrows, large eyes, high cheekbones, a small nose, and a narrow face—qualities often associated with Western Caucasian features—have increasingly become the standard of beauty globally [

28] (pp. 261–279). This standard, heavily influenced by fashion and media representations, has contributed to a long-standing issue of under-representation and misrepresentation of Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC) [

29] models in fashion. The use and appreciation of the acronym BIPOC can vary depending on geographical and socio-political contexts; in Italy, it is preferred to

“di colore”, which carries negative connotations as a “race-neutral euphemism for Black” [

30] (p. 1626); as authors, we have chosen to use BIPOC, as encouraged by lead activists like the Afro Fashion Association and WAMI Collective (

https://afrofashion.org/our-work/wami/ accessed on 7 October 2025). Fashion magazines, which have historically presented a narrow and homogenized definition of beauty, continue to uphold these beauty standards, often to the exclusion of diverse representations of race and ethnicity [

31] (pp. 83–108).

However, the rise of digital platforms has disrupted this longstanding norm, challenging the status quo. These new media spaces provide platforms for alternative beauty standards and subcultural trends, offering more inclusive portrayals of beauty that go beyond the Eurocentric ideals traditionally espoused by mainstream fashion media [

10] (pp. 153–159). Nevertheless, the ethical responsibility of traditional media in promoting social justice remains crucial [

32]. Despite the growth of digital spaces potentially offering alternative beauty representations, the systemic under-representation of non-White bodies in fashion communication remains a significant issue in both older and new media [

33].

However, the representation of BIPOC models on magazine covers is just the tip of the iceberg. Systemic under-representation pervades the entire fashion industry, affecting runway shows, advertising campaigns, and editorial content. Moreover, under-representation is not the only issue; stereotyping misrepresentation is equally common and sometimes even more harmful.

Black models portrayed on fashion magazine covers generally do not reflect the majority of Black bodies and features; furthermore, Black models often straighten their hair or wear wigs and use Western-style makeup, thereby minimizing their racial characteristics. The other side of the coin is potentially even more problematic because it is subtler. In this case, Black models often exhibit particularly dark skin, very curly or braided hair, and other pronounced “Afro” features. This over-accentuation of natural markers is the result of a “performance mechanism” aimed at a white audience, which enhances so-called “exotic” looks that accentuate a sense of “otherness” compared to Western expectations.

Furthermore,

Vogue Italia has also featured models from Asian countries, such as China and Korea, but their visual treatment frequently adheres to an alternative representational logic. In such cases, the emphasis is shifted towards an aestheticized version of “Asianness”, aligning with Western ideals of minimalism, refinement, and exotic delicacy. This shift in focus away from hyper-visible racial difference is a notable development in the study of Asian American identity. This form of racialized representation, while less overtly marked than the hyper-exoticisation of Blackness, nonetheless reproduces Orientalist tropes by constructing East Asian models as embodiments of elegance and restraint, rather than as complex or culturally situated subjects [

34]. Such representational strategies are not isolated, but rather reproduce a broader visual hegemony rooted in historical dynamics of power. The visual legacy of Orientalism and colonial discourse is evident in the construction of non-Western bodies through the aestheticization of difference, which functions as a form of representation that simultaneously fascinates and marginalizes [

35,

36].

Unsurprisingly, gender and race are also intricately connected in relation to this issue. Although the Black male body is often perceived by whites as “dangerous” [

37], Black female bodies, caught in a precarious balance between familiarity and otherness, are frequently hyper-sexualized, and their exoticism becomes almost fetishized. This hyper-sexualization often results in depictions of Black bodies with a higher degree of nudity, as if to allude to a primitive, natural state of humankind, almost recalling the colonial imaginary of the “noble savage”.

Thus, the representation of racialized bodies is the second element we consider in order to discuss how the history of the covers of Vogue Italia represents a wider social and cultural evolution. In terms of the representation of racialized people, Vogue Italia allows us to reconstruct a social and cultural change in Italian society, both through the entry of new human capital, and in terms of a public debate too often polluted by prejudices and racist positions.

4. Fashion Magazine Covers Through Digital Archives: A Longitudinal Analysis of Vogue Italia

The role of fashion in shaping imaginaries, co-producing self-awareness, and constructing bodies has long been studied within fashion scholarship [

38]. Building on this tradition, this research aims to contribute to the growing body of studies that place fashion studies within broader socio-cultural and political debates. By focusing on visual and semiotic narratives constructed by

Vogue Italia, this study aims to shed light on how fashion media, both from a historiographical and contemporary perspective, interacts with and represent diversity, while also engaging with global dynamics [

39] (pp. 97–114). The decision to focus on the visual dimension of the phenomenon stems precisely from the very nature of the object of study: fashion, in its essence, has a very strong visual inclination [

40] (pp. 152–171). The cover of a fashion magazine, in its modern form, is a case in which different aspects of the fashion world come together—communication, media, art, textiles, and bodies—all distilled and condensed into a single medium.

This work employs a qualitative longitudinal methodology focused on the analysis of Vogue Italia digital archive. Digital archives provide an invaluable resource for exploring fashion’s role in producing and disseminating cultural imaginaries, as they allow for the access to a rich and varied body of materials over time. Specifically, this study examines the Vogue Italia covers from 1964 to 2024, with a specific focus on the last 14 years, a period marked by increased attention to diversity, inclusion, and the effects of digitalization on fashion narratives.

The choice of

Vogue Italia as the primary case study is deliberate. As a central figure in the Italian fashion system, the magazine has historically embodied the distinctive qualities of Made in Italy creations, functioning as both a cultural product and a key player in the global fashion network [

39] (pp. 97–114) [

41] (pp. 113–123). Its digital archive, inaugurated in 2013 to celebrate the magazine’s 50th anniversary, offers unprecedented access to historical materials, making it an essential tool for examining the evolution of fashion imaginaries over time [

42] (pp. 129–142).

To explore the role of

Vogue Italia covers in shaping and reflecting socio-cultural imaginaries, this study employed a visual analysis [

43,

44] based on a grounded analytical approach [

45] (pp. 34–35). All 881

Vogue Italia covers (from 1964 to 2024) were sampled and coded using a multi-level semiotic approach [

46]. A first level of coding involved the objective description of the images, based on the number of subjects on the covers, their gender, the composition of the image itself (close-up, half-length, whole subject) and their ethnic origin. The next level of analysis consisted of the description of certain characteristics of the images, particularly the direction of the gaze of the portrayed subject (frontal or lateral, non-directed, eyes closed). A third level of analysis consisted of detecting the presence or otherwise of bodies ‘conforming’ to the beauty standards of the mainstream fashion, the detection of aspects such as excessive thinness, sexualization (consisting of exposure of erogenous parts of the body, provocative attitudes, and explicit or ambiguous photographic compositions with clear references to the sexual sphere).

An aspect that needs to be considered is that, in visual analysis, no matter how much we may try to limit arbitrariness with methodological countermeasures, judgement is, inevitably, subject to biases of various kinds [

47] (pp. 29–42), such as cultural background, age, social position, and gender. When we talk about the stories that images can tell, they are elicited by the observer. Imaginaries, however, although socially shared, are infinitely plural, multifaceted, and non-repeatable. If subjected to an observer coming from another cultural, geographical, or demographic context, the same image would arouse reactions and evoke totally or partially different imaginaries.

If this is generally true of visual culture, it is particularly relevant in the context of a visually sensitive phenomenon such as fashion. As we know, until very recently, fashion was a Eurocentric phenomenon peculiar to Western society [

48] (pp. 247–255). Besides its global attire and influence, people have always practised mixing and cultural hybridisation in distinctive social and geographical contexts. In the global and digital panorama, these practices remain a key component in understanding some of the mechanisms of the phenomenon.

5. Discussion

5.1. First Level of Coding

Firstly, all 881 covers were coded using several objective parameters. Specifically, these parameters included the number of subjects in the image, their gender, and their ethnicity. Below are some graphs illustrating the distribution of these parameters over the 60 years analyzed.

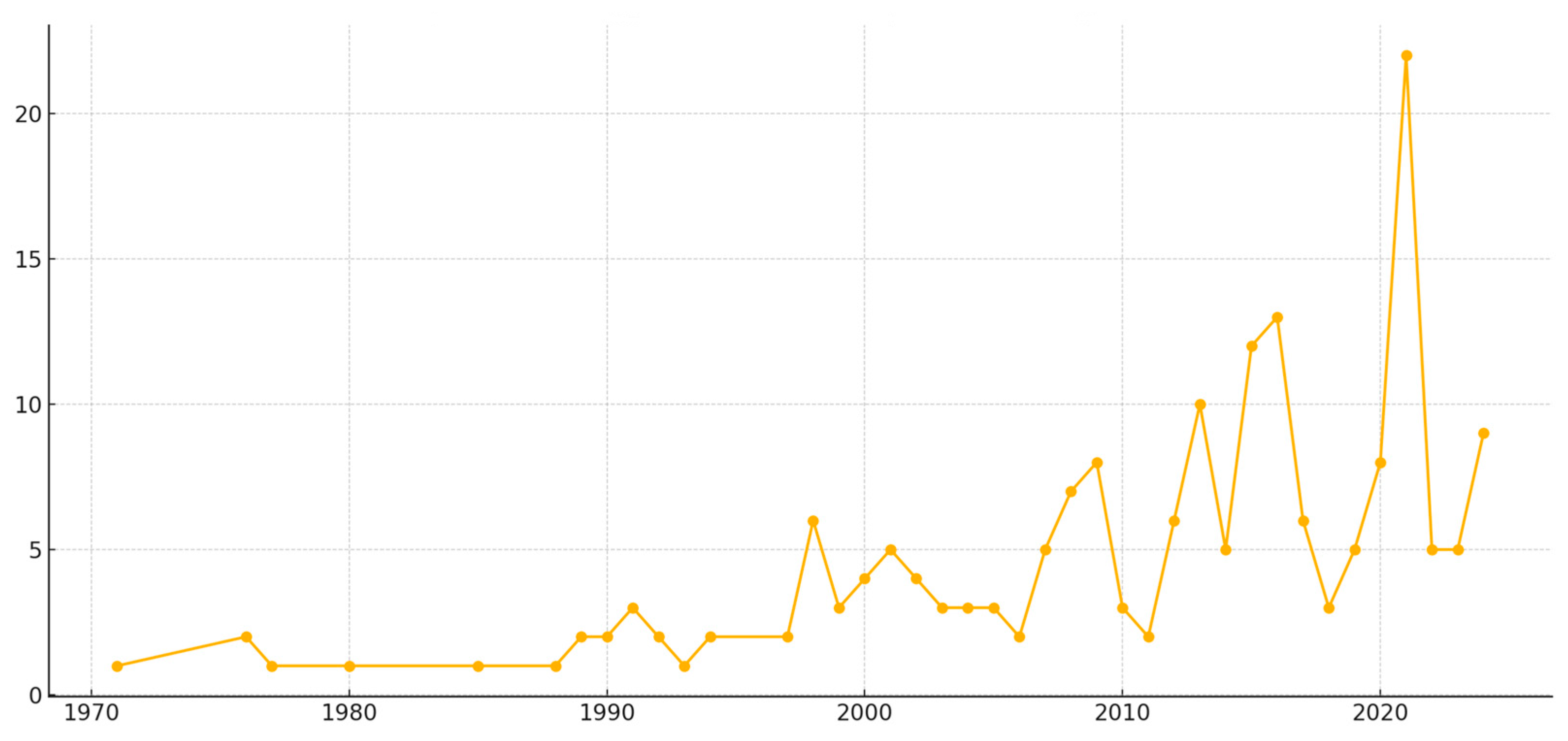

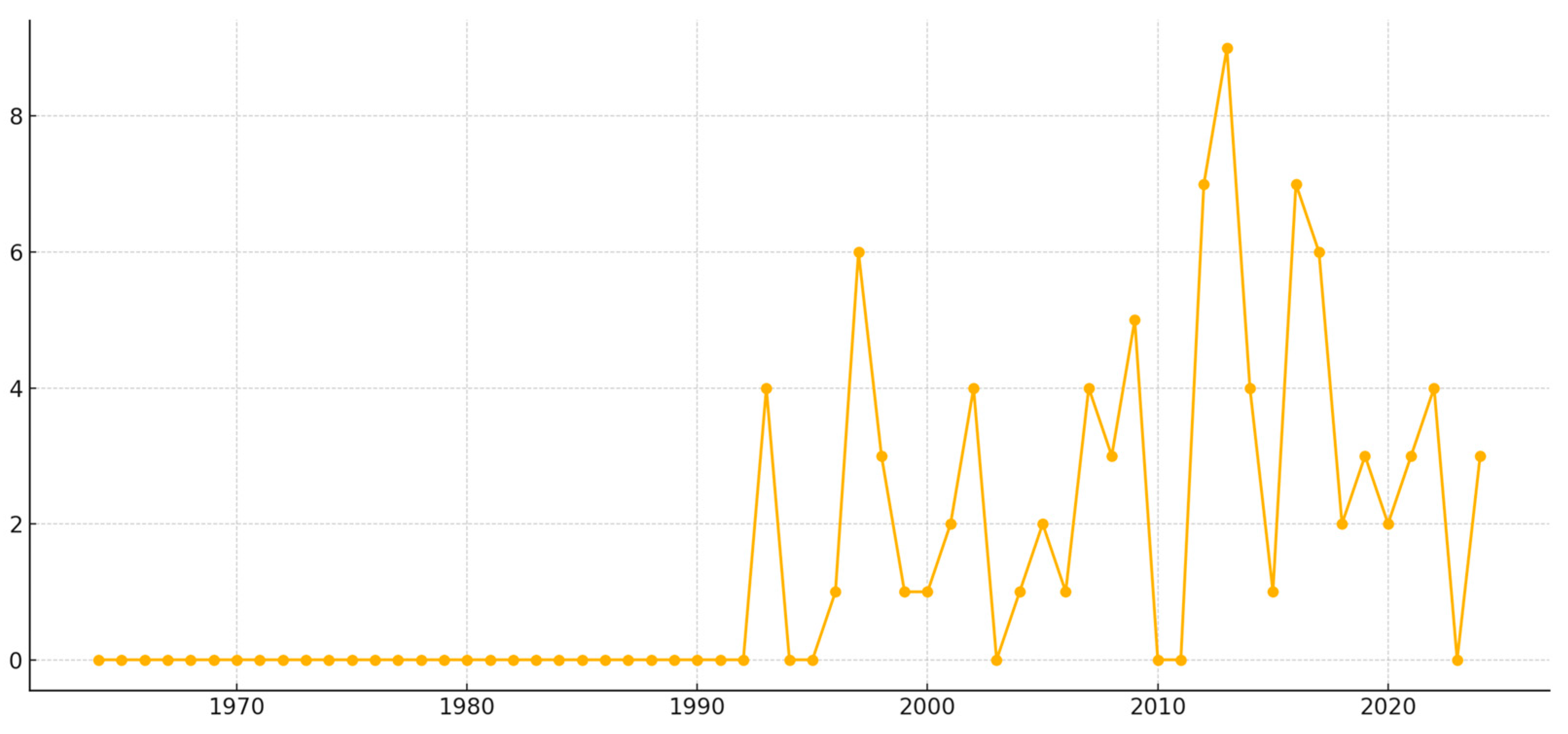

As can be seen from the graphs in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, both the presence of non-Caucasian subjects and the presence of male subjects have increased significantly since 2010 onwards.

5.2. Second Level of Coding

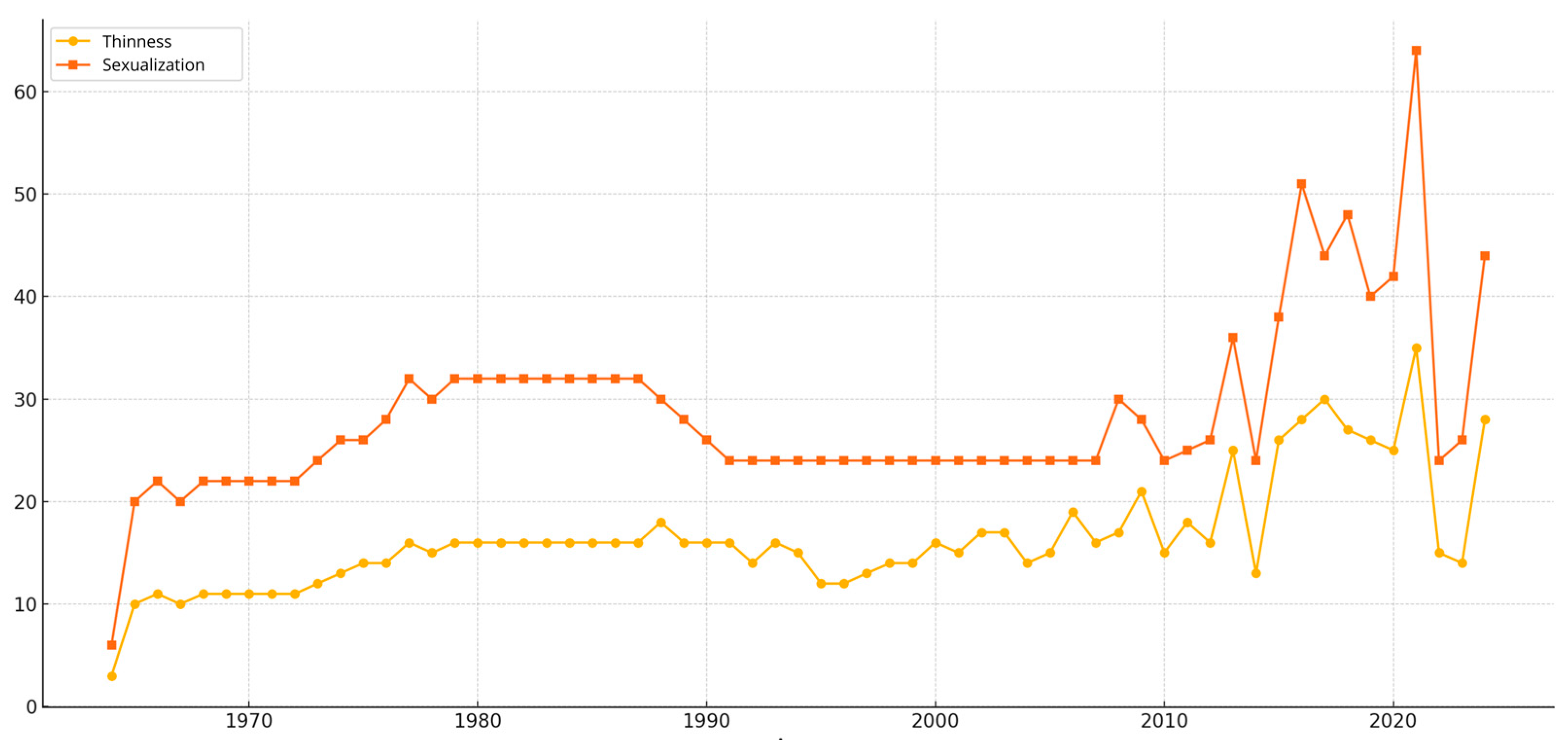

Upon advancement into the coding process, the second level of the process involves creating categories with a higher level of subjectivity (as mentioned above, partly dependent on the social, cultural, demographic, and geographical background of the researchers). An attempt to limit the arbitrariness of this categorization was made by having multiple researchers working together on the same material, each bringing different sensibilities and backgrounds, thereby limiting the inevitable subjectivity inherent in this methodological approach. The categories developed in this phase of the analysis are in accordance with mainstream fashion standards: the thinness and sexualization of the subjects represented on the covers of magazines. Regarding the category of conformity, there was almost total adherence. This is not surprising, given that Vogue Italia, as specified, has represented—and continues to represent—one of the gatekeepers that define these parameters within the fashion world and, to a certain extent, society. When discussing the other two analyzed dimensions, thresholds were established for the intensity with which thinness and sexualization are displayed.

It is immediately clear that the phenomenon of thinness and sexualization is present throughout the history of the magazine, with a rather noticeable increase since the 2000s. It is also interesting to see how both phenomena were combined, as shown in

Figure 3, follow a rather similar trend. This is also true when considering the phenomenon of ethnicization of the subjects represented (

Figure 4).

It would appear that the recurrence of the three parameters has remained fairly consistent throughout the magazine’s history to date. Having concluded this summary of the results of the first two levels of coding, we will now proceed in greater detail with the third level of coding, addressing each of the aspects that emerged from the grounded analysis in a more specific and in-depth manner.

5.3. Vogue Italia and Gender

Since 1967, L’UOMO Vogue has been the first magazine for men in Italy, published by Condé Nast and designed as a supplement to Vogue Italia by Fabio Lucchini. We have therefore chosen to analyze the male representations in Vogue Italia rather than the emerging ones in L’UOMO Vogue, because of Vogue’s power over imaginaries related to fashion, beauty, and the body in a broader sense, allowing us to reflect on the ways in which the relationship between genders is rewritten in a time that requires new representations.

Looking at the covers of Vogue Italia over time, we can clearly see a rewriting of the role of women, represented throughout the Sartori era (1964–1988) with close-ups of models adorned or framed by fashion objects. This season is characterized by an almost constant recurrence of close-up images (or barely discernible half-busts) with frontal perspectives, in which the focus is on the face. There are no elements of sexualization, and the canons of beauty are extremely stereotyped (the models are white, with a strong majority of models with blue eyes and light hair, recurrently adorned with rather garish red lipstick). All the covers except the December 1988 cover (in which there are three models) depict a single subject; all the covers feature exclusively female models. Franca Sozzani’s revolution in the representation of the body has led to the representation of a woman asserting herself in society with courage and determination. The new image, and thus the affirmation of empowerment, can only take place along two lines. The first is a change in the composition of the images, which begin to shift away from the focus on the face alone and gradually move towards images with a more open field, where the body and its expressions play a more prominent role. Secondly, there is the confrontation with the male world, first seen with the July 1991 cover. Male bodies continue to play an auxiliary role in this period, but they seem to be beginning to take on a more pronounced flanking role during Franca Sozzani’s directorship. Male models appear on 42 covers over these 18 years.

Some covers show male models in an almost marginal position, supporting the image construction centred on the cover girl (below, edgeways), such as those of July 1991, December 1993, and May 1996. Other covers show pairs of models on the same plane, such as those of March and October 1997 and April, November, and December 1998. The male figures still tend to be complementary to the image, but are not central, as the light, colour, and clothing draw attention to the cover girls, but there are exceptions where the presence of the male figure enhances references of a sexual or explicit nature (as in the case of the June 1977 or April 2000 covers, to name a few where the phenomenon is quite conspicuous). Franca Sozzani’s revolution in representing the body led to the representation of a woman asserting herself in society with courage and determination. The new image, and therefore the asserting of empowerment, can only occur in the confrontation with the male world that began appearing on the covers of Vogue Italia in 1991. Male bodies seem to have the role of flanking the model(s) in a secondary position until the 2000s.

In the first decade of the 2000s, this narrative trend seems to be confirmed, with the first covers showing a different representation in the second decade of the century. The November 2016 cover, ‘Smile!’, with Alicia Burke hugging Hussein Abdulrahman in the foreground, recalls the topos of the early Vogue Italia era in a new way, reworking the representation of gender relations and racialization. Also relevant in the same year is the presence of two covers (both dedicated to the December issue) in which there are no female models. The first of these depicts two men dancing, the second depicts a child sitting next to a German shepherd, demonstrating a strong innovative thrust with respect to a trend that had been going on since 1964. The October 2019 cover seems to follow the same line started with the November 2016 cover, depicting Jaden and Willow Smith standing in profile facing each other, with the photograph placed vertically on the cover. Here, we also find references to the history of Vogue Italia, but the reference also seems to be to Italian art history, and, in particular, to Piero della Francesca’s diptych depicting the Dukes of Urbino (1465–14729). However, the covers of Vogue Italia from the end of 2016 mark the start of a new course, one that succeeds the luminous era of Franca Sozzani and which demonstrates an attempt to reread her immense legacy in order to elaborate and communicate the more contemporary approaches to fashion, body, gender, and race.

In the years between 2020 and 2022, another interesting phenomenon manifests itself: in the case of 18 covers (out of a total of 73), bodies are replaced by illustrations or non-human bodies (particularly in the cases of the covers of the January 2021 issue, featuring a baby ostrich and a dog).

From this point of view, the latest period of Vogue Italia, especially with the appointment of Francesca Ragazzi as Editor-in-Chief, the visual language of Vogue Italia and its representations seem to be moving in the direction of a more contemporary fashion communication, and one that speaks to a wide audience, albeit not always through print, but increasingly through digital fruition.

The last few years therefore mark further changes, which we witness just by looking at the covers. Although, since 1991, the presence of men has been felt (albeit a minority and secondary presence), 2023 was a year in which all the covers represented only a cover girl, alone, in the more classic use of the fashion cover, but with a very contemporary content: in fact, female characters appear, always alone and always full-length, telling the story of the contemporary woman between references and rediscovery of the past (Isabella Rossellini, October 2023; Angelina Kendall on the La Novità cover, September 2023), and more contemporary representations (Elodie, February 2023; Bella Hadid in the first shoot to use artificial intelligence, May 2023).

The year 2024, from this point of view, is also extremely important for understanding the new fashion communication: out of ten covers (January–October 2024), four represent a fashion narrative that plays with diversity.

September 2024 saw the return of Isabella Rossellini on the cover, recalling, for Vogue Italia’s 60th anniversary, the beauty of experience and reshaping the myth of youth. The year 2024 was also an important year for the publication, with the first cover featuring a transsexual model, actress and artist, Hunter Schafer, in June 2024; and for the first cover featuring a man in July 2024. The ‘First Man’ cover features the Latin pop star Bad Bunny. Francesca Ragazzi writes in her editorial, “After all, the relationship between Vogue Italia and men is long-standing”. However, it is interesting here to note how this cover reveals an evolution in the representation of gendered images and in the narrative around gendered encounters.

5.4. Vogue Italia and Race

In 1966, the first Black model, Donyale Luna, appeared in Vogue UK. In Italy, the first non-Caucasian model was photographed on the cover of the July 1971 issue, and it was followed by the covers of March, May, and December 1976, December 1977, February 1980, November 1985, and June 1988 (8 covers out of a total of 331). Only three covers with beauties outside the Western canon would follow until the 1990s. The entire decade from 1990 to 2000 is also characterized by a sparse presence of non-White models. The period from 2001 to 2011 is almost entirely devoid of racial representation (with the exception of the November 2001, October 2002, and May 2008 covers) despite the publication of the iconic Black Issue in July 2008 when, in response to the outcry over the apparent reluctance of fashion magazines to feature Black models on their covers and editorial spreads, Franca Sozzani took action by commissioning Steven Meisel to create four separate covers featuring the Black supermodels Naomi Campbell, Liya Kebede, Jourdan Dunn, and Sessilee Lopez, styled by Edward Enninful.

In an editorial published in October 2010, Sozzani recalled how, in those years, the prevailing rhetoric suggested that Black models were less sought after and employed because they “sold less”. She vehemently rejected the assumption, arguing that the issue, particularly in the Italian and European contexts, lay in the scouting process. She also refuted the assumption that the problem of under-representation was based on racial discrimination, asserting that the only thing that matters is that a model is as beautiful as one expects a model to be, regardless of ethnicity and colour (

https://www.vogue.it/magazine/blog-del-direttore/2010/10/15-ottobre accessed on 7 October 2025). However, the statement still contains the underlying issue of beauty standards. Among all the Black models featured in the issue, there was no trace of curly or braided hairstyles; the models were skinny with aquiline noses and high cheekbones. The only “Black” feature was their non-white skin, yet Blackness encompasses much more than just skin tone.

Moreover, despite being a landmark issue, pioneering for its time and one of the best-selling editions of Vogue Italia, the Black Issue did not truly bring about any revolutions. Black models remain a minority, often conforming to white beauty standards or being exoticized. The fight to make the fashion industry more diverse and inclusive was far from over.

The advent of the 2020s sent an encouraging message with the second February cover, for which Paolo Roversi captured Maty Fall Diba, a model of Senegalese origin who had just turned 18 and obtained Italian citizenship. She is portrayed holding a stone block with the word “ITALIA”, and the caption reads “Italian beauty”. Fall challenged deeply ingrained perceptions of Italian identity, showing how “Italian Beauty” can transcend ethnic and racial homogeneity; Italian identity requires explicit affirmation, reflecting an inherent tension in expanding the boundaries of Italianness.

On initial observation, the cover appears to celebrate a redefinition of national identity, suggesting that “Italian beauty” can transcend ethnic and racial homogeneity. Nevertheless, this depiction is by no means a simple symbol of inclusivity. By positioning a Black model who has recently acquired Italian citizenship as the living manifestation of Italian beauty, Vogue Italia performs a carefully orchestrated display of diversity that serves to simultaneously reinforce the exceptionalism of racialized inclusion. The necessity to explicitly affirm Fall’s Italian identity reveals an inherent tension in the magazine’s visual discourse: rather than reflecting genuine pluralism, it demonstrates the limits and performativity of racial representation within the Italian fashion system.

Throughout 2021, we see several non-White models and celebrities being portraited, including Ifrah Quuasim (January 21), Binx Walton, Adut Akech, Tao Okamoto (March 21), Selena Forrest, Amar Akway, Caren Jepkemei, and Maty Fall Diba (May 21), Rihanna (June 21), and Mona Tougaard (August 21). All of these covers reflect both an increase in the number of Black models and a shift in stylistic norms.

It is evident that these covers not only signify an augmentation in the number of Black models, but also a deviation from conventional stylistic norms. Nevertheless, this diversification frequently obscures a more intricate reality. The featured models, hailing from diverse nationalities and cultural backgrounds, are predominantly characterized by a homogenized esthetic of “Blackness”. This flattening of distinct identities is reminiscent of colonial visual regimes [

49], in which racial difference is emphasized while cultural specificity is obscured. In this sense,

Vogue Italia’s approach to diversity remains anchored in an optics of exoticization and symbolic inclusion, rather than in a genuine recognition of plurality within the African diaspora.

The most noteworthy cover from 2021 in this regard is the December issue, which portrays Maty Fall Diba and two of her closest friends, Khady Sow and Ndack Ndiaye, who share her Senegalese heritage and are not professional models. This end-of-year issue, titled ‘Memories’, is dedicated to personal recollections. The cover aims to pay homage to personal bonds, with an esthetic reminiscent of family photo albums. The three young women are depicted in voluminous white dresses with their natural hair.

In 2022, the trend of featuring Black models and celebrities on the covers of Vogue Italia continued. Joan Smalls graced the May cover, followed by Adut Akech in June and Zendaya in July. The February 2022 cover featured an Italo-Nigerian model and actress, Coco Rebecca Edogamhe. The Afro-Italian features of Edogamhe, combined with traditional Afro braids and an Italian Prada jacket, exemplify the merging of multicultural influences within the Italian identity. Her direct gaze and confident pose further assert agency, challenging the viewer to reconcile traditional perceptions with the reality of Italy’s diverse population.

In June 2023, the cover features Anok Yai, dressed in white and with braided hair, photographed on a train. In December, Liya Kebede graced the cover of an issue dedicated to art and features the Ethiopian-origin painter Jem Perucchini in a shot by the Ghanaian-origin photographer Campbell Addy.

In February 2024, Vogue Italia’s cover, titled ‘Ciao Ragazze’, features seven Italian models under 26 years of age: Adele Aldighieri, Ajok Daing (of Sudanese origin), Malika El Maslouhi (Italo-Tunisian), Marina Moioli, Maty Fall Diba (of Senegalese origin), Paola Manes, and Valerie Buldini. In total, between 2017 and 2024, Black bodies appear on 33 covers (out of a total of 174), marking a clear change from the past.

6. Conclusions: A Reflection on the Journey of Vogue Italia

Fashion magazine covers, as symbolic and cultural artefacts, have the unique ability to reflect the evolution of societal discourses that extend far beyond fashion itself. They serve as mirrors to contemporary social and cultural changes, revealing how fashion both shapes and responds to shifting norms.

In recent years, the demand for broader representation, particularly among younger generations, who are more active online and do not always engage with Vogue Italia medium directly, has challenged traditional forms of fashion communication. This has prompted a rethinking of visual and semiotic narratives that can portray fashion in a more inclusive, plural, and nuanced way.

The public conversation about gender equality, the need to combat gender-based violence, and the broader discourse on social justice have significantly influenced the way we view the representation of models on magazine covers. No longer merely symbols of fashion and femininity rooted in the Western ideal, the representation of diverse bodies, skin tones, ages, and genders on the covers of Vogue Italia has become a means of restoring dignity and affirming presence and voice. The shift towards more inclusive representations acknowledges the changing societal landscape, where the need for diversity and equality has become central.

Our historical analysis highlights the evolution of the relationship between fashion, gender, and race, with a significant shift occurring after the 1990s. From this period onwards, there has been a gradual yet undeniable increase in the representation of gender and racial diversity. Although the dominant fashion image still favours the idealized, youthful, white female body, the inclusion of models from different racial and gender backgrounds has grown. Despite this progress, traditional stereotypes continue to persist, and the power dynamics between the sexes remain a visible element on the covers of the magazine, where women are still positioned as central figures. Similarly, representations of race continue to be influenced by exoticization and stereotypes, with Black and non-Caucasian models often portrayed through a narrow lens.

However, there has also been an evolution in public discourse and sensibility, especially in recent years, and this has had an impact on the covers of Vogue Italia. The affirmation of women’s strength, power, and independence—of their creativity, harmony, and art—is increasingly depicted in different ways: in mature years, in dialogue with the male universe, in the representation of an Italian society that is changing as a result of migration processes.

Although we note that diversity representations are still limited to a minority, we register an increasing sensitivity over time that reveals not only an awareness of the role of fashion in society, but also the importance of listening to and acknowledging the voice of the reading public and consumers. The challenge for Vogue Italia, from this point of view, concerns its language and its choices: how can it respond to this demand for representation and inclusion of categories of bodies traditionally excluded from fashion communication?

From this point of view,

Vogue Italia reflects an international trend, with

Vogue editors around the world repeatedly reaffirming a progressive, anti-racist position, reflected in the values of inclusiveness, love, nature, democracy, sustainability, respect, freedom, equality, education, and beauty. This is highlighted in the joint declaration of

Vogue values signed by the 26 editors of the global issues in 2019, under the leadership of Emanuele Farneti. The text states as follows:“For over a century,

Vogue has empowered and embraced creativity and craftsmanship; celebrated fashion and shined a light on the critical issues of the time.

Vogue stands for thought-provoking imagery and intelligent storytelling. We devote ourselves to supporting creators in all shapes and forms.

Vogue looks to the future with optimism, remains global in its vision, and stands committed to practices that celebrate cultures and preserve our planet for future generations. We speak with a unified voice across 26 editions standing for the values of diversity, responsibility and respect for individuals, communities and for our natural environment” (

https://www.vogue.it/news/article/vogue-values-i-valori-di-vogue-dichiarazione accessed on 7 October 2025). It has also been reaffirmed in the June 2024 editorial signed by the current Editor-in-Chief, Francesca Ragazzi, commenting on Marco Rambaldi’s manifesto, drawn up thanks to the collaboration between

Vogue Italia and the European Parliament.

Our analysis shows that these editorial choices, along with in the selection of subjects, the framing of photographs, or the body language of models, are crucial in reshaping societal perceptions of fashion, beauty, and identity. The central shift from face to body, which marked Franca Sozzani’s transition to the new era of representation, is an example of how choices about covers have the power to mark new standards, but also new meanings and values. In fact, the entire Sozzani era is marked by choices that tell of a change in fashion’s approach to society. Choices regarding the subjects, the cuts of the photographs, and the poses of the models affect the relationship between the bodies and the elements that surround them. From these choices, it is possible to define a new way of telling the story of fashion, beauty, the body, and gender, now demanded by a different public than before, capable of interacting, stimulating debate, raising new issues. Social networks have indeed affected the processes of power and influence over imaginaries, with the emergence of prosumer culture [

50] (pp. 37–55), but also the way of fruition (paper to virtual, slow to fast, etc.).

Moreover, the narratives and imaginaries propagated by Vogue are elaborated and reflect the cultural substratum to which they belong. As authors, from this point of view, we also recognize the biases of this analysis, caused by having shared imaginaries and representations peculiar to the West and the Western media culture. However, with the advent of the Internet, the elements such as canons, poses, esthetic models, as well as the role of gatekeeper that Vogue Italia played, were increasingly questioned in the 2000s by consumers who became more and more involved in the production processes.

Reflecting on the trajectory of Vogue Italia, it is evident that the magazine’s editorial decisions have been pivotal in exploring innovative approaches to the representation of fashion and beauty. These decisions extend beyond esthetic considerations; they reflect a broader cultural shift, addressing the challenge of dismantling established paradigms and the development of more inclusive visual languages. In this regard, the evolution of Vogue Italia can be understood as a case study in the changing dynamics of fashion communication, which continues to be influenced by the growing demand—both authentic and constructed—for a more inclusive and diverse future.