Analysis of Motor and Perceptual–Cognitive Performance in Young Soccer Players: Insights into Training Experience and Biological Maturation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Statistical Analysis

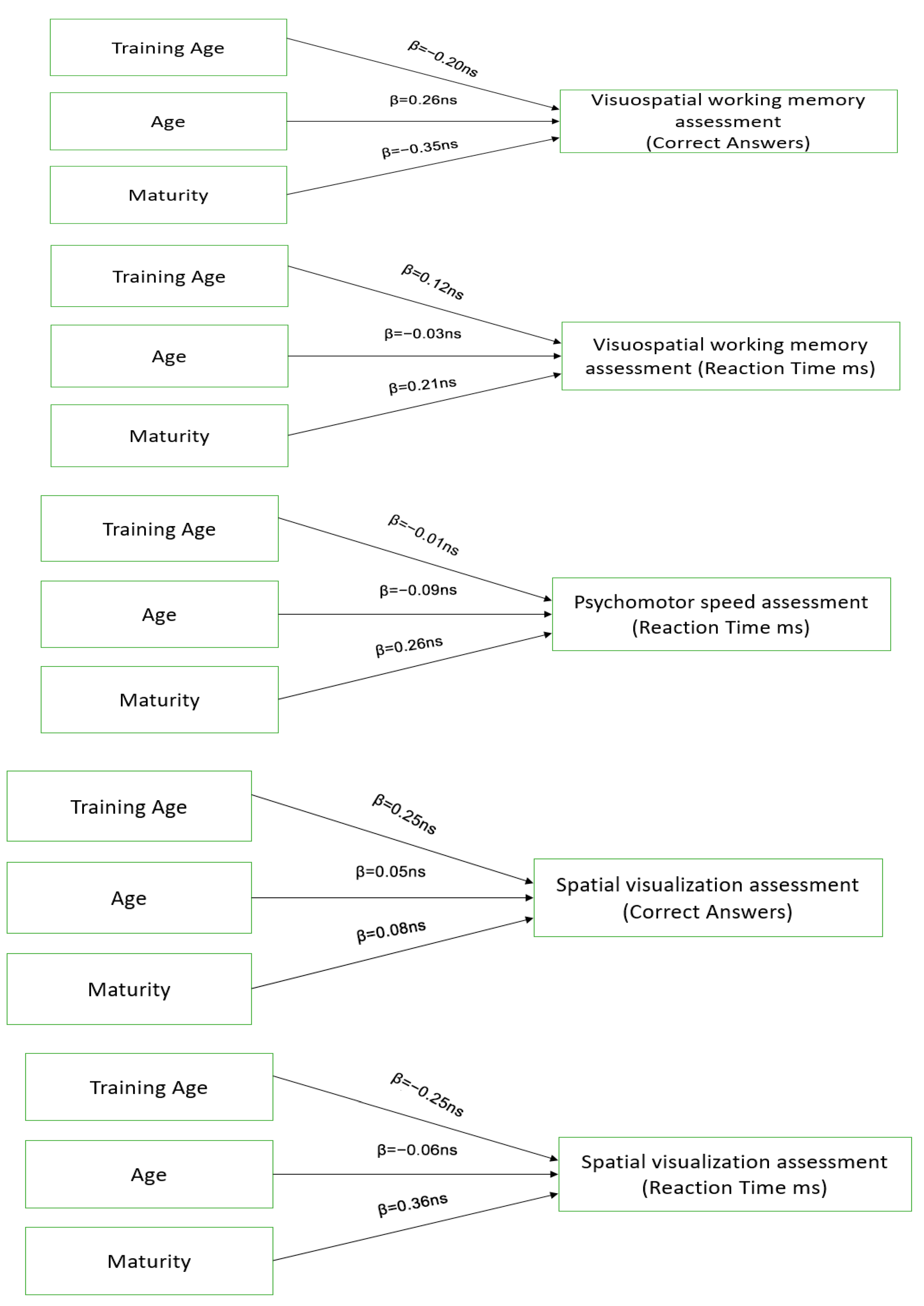

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHV | Peak Height Velocity |

| SJ | Squat Jump |

| CMJ | Countermovement Jump |

| DJ | Drop Jump |

| SC-CODS | Time in the pre-planned condition of the semicircular test |

| SC-RA | Time in random condition of the semicircular test |

| REAC-INDEX | Difference SC-CODS vs. SC-RA. |

References

- Cumming, S.P.; Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Eisenmann, J.C.; Malina, R.M. Bio-Banding in Sport: Applications to Competition, Talent Identification, and Strength and Conditioning of Youth Athletes. Strength Cond. J. 2017, 39, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, R.; Hirose, N. Relationship Among Biological Maturation, Physical Characteristics, and Motor Abilities in Youth Elite Soccer Players. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, K.; Lloyd, R.S.; McCormack, S.; Williams, G.; Baker, J.; Eisenmann, J.C. Optimising Long-Term Athletic Development: An Investigation of Practitioners’ Knowledge, Adherence, Practices and Challenges. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L. The Youth Physical Development Model: A New Approach to Long-Term Athletic Development. Strength Cond. J. 2012, 34, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, M.; Moreira, A.; Costa, R.A.; Lima, M.R.; Thiengo, C.R.; Marquez, W.Q.; Coutts, A.J.; Aoki, M.S. Biological Maturation Influences Selection Process in Youth Elite Soccer Players. Biol. Sport 2022, 39, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beunen, G.; Malina, R.M. Growth and Biologic Maturation: Relevance to Athletic Performance. In The Young Athlete; Hebestreit, H., Bar-Or, O., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-1-4051-5647-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Howard, R.; De Ste Croix, M.B.A.; Williams, C.A.; Best, T.M.; Alvar, B.A.; Micheli, L.J.; Thomas, D.P.; et al. Long-Term Athletic Development- Part 1: A Pathway for All Youth. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakidis, N.D.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Ribeiro, J.; Lola, A.C.; Manou, V. Maturation Stage Does Not Affect Change of Direction Asymmetries in Young Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 3440–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburgh, L.; Scherder, E.J.A.; Van Lange, P.A.M.; Oosterlaan, J. Executive Functioning in Highly Talented Soccer Players. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca, A.; Ford, P.R.; McRobert, A.P.; Williams, A.M. Perceptual-Cognitive Skills and Their Interaction as a Function of Task Constraints in Soccer. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 35, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Ford, P.R. Expertise and Expert Performance in Sport. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 1, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijgen, B.C.H.; Leemhuis, S.; Kok, N.M.; Verburgh, L.; Oosterlaan, J.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Visscher, C. Cognitive Functions in Elite and Sub-Elite Youth Soccer Players Aged 13 to 17 Years. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugan, J.A.; Lervold, K.; Kaalvik, H.; Moen, F. A Scoping Review of Empirical Research on Executive Functions and Game Intelligence in Soccer. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1536174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, K.; Bürger, D.; Pastel, S. Sports Training in Virtual Reality with a Focus on Visual Perception: A Systematic Review. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1530948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zheng, M.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Cao, C. Effects of Perceptual-Cognitive Training on Anticipation and Decision-Making Skills in Team Sports: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krampe, R.T.; Tesch-Römer, C. The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Reilly, T. Talent Identification and Development in Soccer. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, D.P.; Causer, J.; Williams, A.M.; Ford, P.R. Perceptual-cognitive Skill Training and Its Transfer to Expert Performance in the Field: Future Research Directions. European J. Sport Sci. 2015, 15, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, M.W.; Kramer, A.F.; Basak, C.; Prakash, R.S.; Roberts, B. Are Expert Athletes ‘Expert’ in the Cognitive Laboratory? A Meta-Analytic Review of Cognition and Sport Expertise. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2010, 24, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, F.; Gray, R.; Wachsmuth, S.; Höner, O. Perceptual-Motor and Perceptual-Cognitive Skill Acquisition in Soccer: A Systematic Review on the Influence of Practice Design and Coaching Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 772201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnithan, V.; White, J.; Georgiou, A.; Iga, J.; Drust, B. Talent Identification in Youth Soccer. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romann, M.; Cobley, S. Relative Age Effects in Athletic Sprinting and Corrective Adjustments as a Solution for Their Removal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadlow, S.M.; Panchuk, D.; Mann, D.L.; Portus, M.R.; Abernethy, B. Modified Perceptual Training in Sport: A New Classification Framework. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A Systematic Review of the Psychological and Social Benefits of Participation in Sport for Children and Adolescents: Informing Development of a Conceptual Model of Health through Sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirwald, R.L.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Bailey, D.A.; Beunen, G.P. An Assessment of Maturity from Anthropometric Measurements. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrakis, D.; Bassa, E.; Papavasileiou, A.; Xenofondos, A.; Patikas, D.A. Backward Running: Acute Effects on Sprint Performance in Preadolescent Boys. Sports 2020, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatthorn, J.F.; Gouge, S.; Nussbaumer, S.; Stauffacher, S.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Maffiuletti, N.A. Validity and Reliability of Optojump Photoelectric Cells for Estimating Vertical Jump Height. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čoh, M.; Vodičar, J.; Žvan, M.; Šimenko, J.; Stodolka, J.; Rauter, S.; Maćkala, K. Are Change-of-Direction Speed and Reactive Agility Independent Skills Even When Using the Same Movement Pattern? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, G.; Mitrotasios, M.; Iuliano, E.; Pistone, E.M.; Aquino, G.; Calcagno, G.; DI Cagno, A. Agility and Change of Direction in Soccer: Differences According to the Player Ages. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2017, 57, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, N.; Zaar, C.; Kovar, J.; Lahmann-Lammert, L.; Wollesen, B. Relation of General-Perceptual Cognitive Abilities and Sport-Specific Performance of Young Competitive Soccer Players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2024, 24, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, R.; Tavares, R. Training Spatial Intelligence in Football through the Cognitive Load Scale. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1628561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vítor de Assis, J.; Costa, V.; Casanova, F.; Cardoso, F.; Teoldo, I. Visual Search Strategy and Anticipation in Tactical Behavior of Young Soccer Players. Sci. Med. Footb. 2021, 5, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisladottir, T.; Petrović, M.; Sinković, F.; Novak, D. The Relationship between Agility, Linear Sprinting, and Vertical Jumping Performance in U-14 and Professional Senior Team Sports Players. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1385721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuriato, M.; Pellino, V.C.; Lovecchio, N.; Codella, R.; Vandoni, M.; Talpey, S. Do Maturation, Anthropometrics and Leg Muscle Qualities Influence Repeated Change of Direction Performance in Adolescent Boys and Girls? Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Read, P.; Graham-Smith, P.; Cardinale, M.; Jones, T.W. Differences in Sprinting and Jumping Performance Between Maturity Status Groups in Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 1405–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, R.W.; Oliver, J.L.; Hughes, M.G.; Cronin, J.B.; Lloyd, R.S. Maximal Sprint Speed in Boys of Increasing Maturity. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2015, 27, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, M.C.; Cronin, J.B.; Oliver, J.; Hughes, M. Kinematics and Kinetics of Maximum Running Speed in Youth Across Maturity. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2015, 27, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faude, O.; Koch, T.; Meyer, T. Straight Sprinting Is the Most Frequent Action in Goal Situations in Professional Football. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, F.; Brunetti, C.; Maver, P.; Galli, M.; Tarabini, M. The Role of Age and Maturation on Jump Performance and Postural Control in Female Adolescent Volleyball Players over a Season. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieschäfer, L.; Schorer, J.; Beppler, J.; Büsch, D. Selection Biases in Elite Youth Handball: Early Maturation Compensates for Younger Relative Age. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1579857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Chen, J.; Yan, R.; Deng, B.; Song, W.; Guan, B.; Sun, J. Effects of Maturation Stage on Physical Fitness in Youth Male Team Sports Players After Plyometric Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. Open 2025, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jávega, G.; Javaloyes, A.; Moya-Ramón, M.; Peña-González, I. Influence of Biological Maturation on Training Load and Physical Performance Adaptations After a Running-Based HIIT Program in Youth Football. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, J.; Julian, R.; Mentzel, S.V.; Hamilton, A.; Hughes, J.D.; De St Croix, M. Maturity Status Influences Perceived Training Load and Neuromuscular Performance during an Academy Soccer Season. Res. Sports Med. 2024, 32, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radnor, J.M.; Staines, J.; Bevan, J.; Cumming, S.P.; Kelly, A.L.; Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L. Maturity Has a Greater Association than Relative Age with Physical Performance in English Male Academy Soccer Players. Sports 2021, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horníková, H.; Hadža, R.; Zemková, E. The Contribution of Perceptual-Cognitive Skills to Reactive Agility in Early and Middle Adolescent Soccer Players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, e478–e484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, A.; Ling, D.S. Conclusions about Interventions, Programs, and Approaches for Improving Executive Functions That Appear Justified and Those That, despite Much Hype, Do Not. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2016, 18, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.M.; Young, W.B. Agility Literature Review: Classifications, Training and Testing. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, B.G.; Young, W.B.; Ford, M. Are the Perceptual and Decision-Making Components of Agility Trainable? A Preliminary Investigation. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1240–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerodimos, V.; Karatrantou, K.; Batatolis, C.; Ioakimidis, P. Sport-Related Effect on Knee Strength Profile during Puberty: Basketball vs. Soccer. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Ericsson, K.A. Perceptual-Cognitive Expertise in Sport: Some Considerations When Applying the Expert Performance Approach. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2005, 24, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestberg, T.; Gustafson, R.; Maurex, L.; Ingvar, M.; Petrovic, P. Executive Functions Predict the Success of Top-Soccer Players. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, M.; Żurek, A.; Jamro, D.; Serweta-Pawlik, A.; Żurek, G. Changes in Concentration Performance and Alternating Attention after Short-Term Virtual Reality Training in E-Athletes: A Pilot Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Hohmann, A.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Pion, J.; Gao, B. Physiological, Anthropometric, and Motor Characteristics of Elite Chinese Youth Athletes From Six Different Sports. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Osorio, F.; Campos-Jara, C.; Martínez-Salazar, C.; Chirosa-Ríos, L.; Martínez-García, D. Effects of Sport-Based Interventions on Children’s Executive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Rogol, A.D.; Cumming, S.P.; Coelho-e-Silva, M.J.; Figueiredo, A.J. Biological Maturation of Youth Athletes: Assessment and Implications. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macnamara, B.N.; Maitra, M. The Role of Deliberate Practice in Expert Performance: Revisiting Ericsson, Krampe & Tesch-Römer (1993). R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faigenbaum, A.D.; Kraemer, W.J.; Blimkie, C.J.R.; Jeffreys, I.; Micheli, L.J.; Nitka, M.; Rowland, T.W. Youth Resistance Training: Updated Position Statement Paper from the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, S60–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Schedule | Experimental Procedures |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | -Anthropometry (body mass, body height, sitting height, leg length, single arm reach test (MROA), both arms reach test (MRBA), and arm span) |

| -Assessment of perceptual skills (psychomotor speed, visuospatial working memory, and spatial visualization) | |

| -Assessment of reactive agility (RA) and change of direction speed (CODS) via the semicircular test (SC) | |

| Day 2 | -Assessment of speed (5 m and 10 m) |

| -Lower limb power assessment (SJ-Squat Jump, CMJ-Countermovement Jump, and DJ20-Drop Jump from a height of 20 cm) | |

| -Agility assessment (t-test) |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD | 95% CI Mean Upper | 95% CI Mean Lower | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | 1.47 | 1.89 | 1.72 ± 9.10 | 1.75 | 1.69 |

| Body mass | 38.10 | 100.40 | 66.06 ± 12.31 | 69.94 | 62.17 |

| Sitting height | 79 | 99 | 90.15 ± 5.05 | 91.74 | 88.55 |

| Leg length | 68 | 94 | 82.61 ± 5.13 | 84.23 | 80.99 |

| MROA | 1.88 | 2.42 | 2.24 ± 0.11 | 2.28 | 2.21 |

| MRBA | 1.85 | 2.40 | 2.21 ± 0.11 | 2.25 | 2.18 |

| Arm Span | 1.45 | 1.91 | 1.74 ± 0.09 | 1.77 | 1.71 |

| Training age | 1 | 12 | 7.43 ± 3.09 | 8.40 | 6.45 |

| Age | 12.52 | 16.71 | 14.86 ± 0.81 | 15.12 | 14.60 |

| Maturity | −0.52 | 2.84 | 1.30 ± 0.88 | 1.58 | 1.03 |

| Assessments | Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD | % * | 95% CI Mean Upper | 95% CI Mean Lower |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visuospatial working memory assessment (Correct Answers) | 6 | 10 | 8.59 ± 1.14 | 85.9% | 8.95 | 8.23 |

| Visuospatial working memory assessment (Reaction Time ms) | 1415.80 | 3974.50 | 2627.38 ± 620.92 | 2823.37 | 2431.39 | |

| Psychomotor speed assessment (Reaction Time ms) | 203.22 | 295.28 | 255.96 ± 22.16 | 262.95 | 248.96 | |

| Spatial visualization assessment (Correct Answers) | 14 | 24 | 18.49 ± 2.44 | 77% | 19.26 | 17.72 |

| Spatial visualization assessment (Reaction Time ms) | 508.12 | 1094.95 | 789.82 ± 158.96 | 840 | 739.65 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD | 95% CI Mean Upper | 95% CI Mean Lower | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprint 5 m (s) | 0.95 | 1.35 | 1.15 ± 0.08 | 1.17 | 1.12 |

| Sprint 10 m (s) | 1.74 | 2.35 | 1.97 ± 0.12 | 2.00 | 1.93 |

| SJ (cm) | 15.30 | 36.10 | 27.43 ± 5.16 | 29.06 | 25.80 |

| CMJ (cm) | 18.30 | 39.50 | 29.54 ± 5.43 | 31.25 | 27.82 |

| DJ20 (cm) | 14.60 | 36.30 | 27.05 ± 5.04 | 28.65 | 25.46 |

| t-test (sec) | 9.40 | 11.85 | 10.28 ± 0.62 | 10.47 | 10.08 |

| SC-CODS(s) | 9.22 | 13.22 | 11.24 ± 1.08 | 11.58 | 10.90 |

| SC-RA (s) | 12.26 | 18.14 | 14.5 ± 1.25 | 14.90 | 14.11 |

| REAC-INDEX (s) | 1.45 | 6.83 | 3.26 ± 1.16 | 3.62 | 2.89 |

| Visuospatial Working Memory Assessment (Correct Answers) | Visuospatial Working Memory Assessment (Reaction Time ms) | Psychomotor Speed Assessment (Reaction Time ms) | Spatial Visualization Assessment (Correct Answers) | Spatial Visualization Assessment (Reaction Time ms) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity | −0.12 ns | 0.12 ns | 0.27 ns | 0.01 ns | 0.18 ns | ||||

| Sprint 5 m | Sprint 10 m | t-test | SJ | CMJ | DJ20 | SC-CODS | SC-RA | REAC-INDEX | |

| −0.55 *** | −0.62 *** | −0.55 *** | 0.47 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.47 ** | −0.35 * | −0.26 | 0.04 ns |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | F | p | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training age | Sprint 5 m | 4.645 | 0.01 | −0.20 | 23.8% |

| Age | 0.03 ns | ||||

| maturity | −0.53 ** | ||||

| Training age | Sprint 10 m | 8.104 | 0.000 | −0.32 * | 37.8% |

| Age | 0.08 ns | ||||

| maturity | −0.61 ** | ||||

| Training age | t-test | 4.469 | 0.01 | −0.15 | 22.9% |

| Age | 0.05 ns | ||||

| maturity | −0.55 ** | ||||

| Training age | SJ | 6.466 | 0.01 | 0.34 * | 31.9% |

| Age | 0.06 ns | ||||

| maturity | 0.46 * | ||||

| Training age | CMJ | 6.247 | 0.01 | 0.33 * | 31% |

| Age | 0.09 ns | ||||

| maturity | 0.46 ** | ||||

| Training age | DJ20 | 4.255 | 0.02 | 0.23 ns | 21.8% |

| Age | 0.05 ns | ||||

| maturity | 0.45 * | ||||

| Training age | SC-CODS | 1.539 | 0.223 | −0.20 ns | 4.4% |

| Age | −0.23 ns | ||||

| maturity | −0.08 ns | ||||

| Training age | SC-RA | 0.684 | 0.568 | −0.14 ns | 2.8% |

| Age | 0.08 ns | ||||

| maturity | −0.24 ns | ||||

| Training age | REAC-INDEX | 0.614 | 0.611 | 0.03 ns | 3.4% |

| Age | 0.28 ns | ||||

| maturity | −0.18 ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lola, A.; Bassa, E.; Symeonidou, S.; Stavropoulou, G.; Papavasileiou, A.; Fregidis, K.; Bismpos, M. Analysis of Motor and Perceptual–Cognitive Performance in Young Soccer Players: Insights into Training Experience and Biological Maturation. Sports 2026, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010022

Lola A, Bassa E, Symeonidou S, Stavropoulou G, Papavasileiou A, Fregidis K, Bismpos M. Analysis of Motor and Perceptual–Cognitive Performance in Young Soccer Players: Insights into Training Experience and Biological Maturation. Sports. 2026; 14(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleLola, Afroditi, Eleni Bassa, Sousana Symeonidou, Georgia Stavropoulou, Anastasia Papavasileiou, Kiriakos Fregidis, and Marios Bismpos. 2026. "Analysis of Motor and Perceptual–Cognitive Performance in Young Soccer Players: Insights into Training Experience and Biological Maturation" Sports 14, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010022

APA StyleLola, A., Bassa, E., Symeonidou, S., Stavropoulou, G., Papavasileiou, A., Fregidis, K., & Bismpos, M. (2026). Analysis of Motor and Perceptual–Cognitive Performance in Young Soccer Players: Insights into Training Experience and Biological Maturation. Sports, 14(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports14010022