Abstract

This study investigates the lubrication properties of GCr15 steel textured surfaces under the conditions of low speed, heavy load, and boundary lubrication, with varying concentrations of Al2O3 particles. Through pin-on-disk tests in 46# hydraulic fluid, it was found that the texture density had little effect on the friction in the absence of abrasive particles and that the friction increases with an increasing texture density in the presence of abrasive particles. Abrasive particle concentration significantly increases the friction on smooth surfaces, while textured surfaces can retain abrasive particles and lubricants, mitigating the increase in friction. The impact of abrasive particles can wear down the texture edges and weaken its friction-reducing effect. This study reveals the interaction between abrasive particle concentration and texture density, providing a theoretical basis for designing textured surfaces suitable for abrasive-containing lubrication environments.

1. Introduction

Lubrication phenomena are common and play a key role in industrial and mechanical engineering. Friction has a great impact on the performance, energy efficiency, and lifetime of mechanical devices such as piston pumps [1], engines [2], and brake pads [3]. Therefore, improving the lubrication properties of surfaces is a pressing issue. Surface technologies including surface coating [4], surface modification [5], and surface texturing [6] have been widely used to enhance the tribological properties of materials. Due to environmental pollution and extreme working conditions, abrasive debris commonly exists in lubrication conditions [7], which has an important effect on the wear behaviors. The corresponding wear mechanism has been rarely reported.

Surface texturing, a method of enhancing the lubrication characteristics of the relative sliding surfaces by machining grooved areas on the surfaces of the friction pair, is a key technology for reducing the coefficient of friction of the contact surfaces and improving the friction performance [8,9]. As early as the mid-1960s, Hamilton et al. [10] demonstrated that micrometer-scale irregular shapes on rotating shaft seals add additional dynamic water pressure, thus increasing the load-carrying capacity. In hydrodynamic lubrication conditions, the surface texture can enhance the load-carrying capacity and oil film thickness of the contact surfaces, effectively reducing the friction contact area, and decreasing the wear [11]. Zhou et al. [12] investigated the mechanism of the influence of the texture parameters on the lubrication performance and pointed out that the surface texture can increase the carrying capacity by enhancing the cavitation effect. Zhang et al. [13] established a numerical analysis model of a textured surface under lubrication conditions and found that the surface texture can generate greater hydrodynamic lift, which increases the fit gap and reduces the surface contact. Another lubrication condition is the boundary lubrication condition, wherein solid contact also occurs. The surface texture can be used as a lubricant storage container to provide the necessary lubrication for the friction pair and in the case of insufficient lubrication will provide secondary lubrication. Liu’s team [14] designed a bionic scale surface texture and experimentally demonstrated that the texture reduces the surface friction and wear by the secondary lubrication effect under oil-poor conditions. Li et al. [15] experimentally concluded that the friction coefficient of the textured surface was reduced by 32.6% compared with the surface without texture. During the operation of the friction pair, particles can appear due to solid contact or the intrusion of environmental contaminants, destroying the lubrication between friction pairs and causing severe three-body wear [16,17]. The lubricant reservoir function is particularly critical under starved or boundary lubrication, yet its effectiveness is highly sensitive to geometric parameters. Kelley et al. [18] experimentally validated this in textured rolling bearings, where friction reduction was attributed to grease storage capacity rather than hydrodynamic enhancement under oscillating motion. In the context of abrasive-laden lubrication, this reservoir effect may simultaneously supply lubricant and capture wear particles. Zou et al. [19,20] investigated the tribological properties of surface textures on particles of different grain sizes and found that textures can store particles and reduce abrasive wear. As systematically reviewed by Etsion [21], micro-dimples serve three primary functions: they act as micro-hydrodynamic bearings to enhance load capacity under full or mixed lubrication, they function as lubricant reservoirs to improve lubrication under starved conditions, and they serve as micro-traps for wear debris to reduce abrasive wear. He et al. [22] recently employed discrete element simulation to reveal how particle breakage and escape dynamics mediate these functions under high contamination, yet experimental validation under controlled particle concentrations remains limited. The influence of abrasive concentration on boundary lubrication conditions has attracted less attention, which is therefore the first objective of this paper.

In addition to the aforementioned benefits, the negative impacts of texture should not be overlooked when designing micro-textured surfaces [23]. For instance, texture edges can lead to stress concentration, thereby increasing frictional losses [24]. Kovalchenko et al. [25] found that laser surface texturing in lubricated non-conformal point contacts, while reducing friction by accelerating lubrication regime transition, significantly increases wear, thereby limiting its applicability in high-precision components. Vladescu et al. [26] found that surface texture in reciprocating contacts exhibits significant lubrication-regime-dependent effects, with grooves parallel to the sliding direction underperforming the smooth surface across all lubrication regimes and texture positioned at stroke ends causing oil film collapse and inducing friction spikes.

On the other hand, the magnitude of the load has a significant effect on the lubrication of the textured surface [27,28,29]. Ding et al. [30] applied different loads ranging from 100 to 700 N to textured samples under different lubrication conditions and found that under the sufficient lubrication condition the friction coefficient decreases with the load, whereas under the insufficient lubrication condition an optimal load was observed to minimize the friction coefficient. In industries such as aerospace and construction machinery, heavy-load conditions are common [31,32]. As the load increases, the oil film thickness decreases, leading to a shift in the lubrication state [33]. Nevertheless, the effect of heavy loads on the effectiveness of textured lubrication under conditions of abrasive-containing lubrication has not been fully investigated. Therefore, the second research objective of this paper is to clarify the performance of different texture densities under heavy-load conditions with abrasive debris lubrication.

This paper studies the interaction between particle concentration and texture density under low-speed and heavy-load conditions and reveals the corresponding wear mechanism. This paper will be organized in the following sequence. The Materials and Methods are presented in Section 2. The Results and the Discussion are introduced in Section 3. Finally, conclusions are presented in Section 4. This study provides a basis for the design of surface textures under particle-contaminated lubrication sliding conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

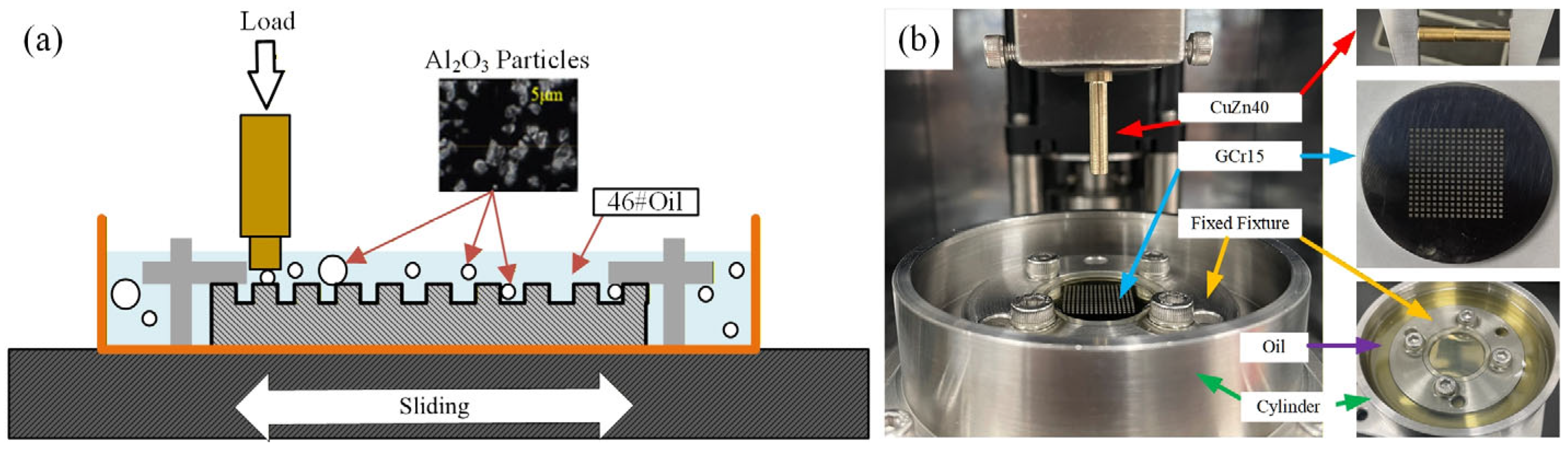

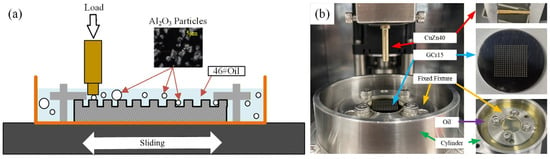

Pin-on-disk tribological tests were conducted to analyze the lubricating properties of the textured surfaces as affected by low-speed, heavy load, and abrasive particles. The experimental form was a uniform reciprocating slide. The HSR-2M (high-speed reciprocating friction and wear tester) apparatus was used to determine the coefficient of friction and wear of the textured surface [34,35]. The experimental principle and its installation are shown in Figure 1. The friction experiment was carried out between the upper and lower samples and the specific experimental assembly is shown in Figure 1b. The load generated by the spring was applied on top of the CuZn40 pin so that the pin was pressed against the surface of the GCr15 disk, which contained the textured surface. The disk was submerged in an oil solution in which the alumina particles are uniformly dispersed. The lower sample is moved horizontally in a reciprocating manner by a motorized drive, and the coefficient of friction is monitored in real time during the experiment.

Figure 1.

Experimental principle and installation, (a) experimental principle, (b) installation.

2.1. Materials

GCr15 steel is widely used in key mechanical transmission components for its excellent mechanical properties [36]. In this study, GCr15 steel disks served as the lower sample. Each disk has a diameter of 32 mm and a thickness of 5 mm. The pin was made from a brass alloy (CuZn40). The diameter of the pin’s convex bottom clamping part is 6 mm, while the diameter of the top friction part is 4 mm. Table 1 and Table 2 show the chemical composition of the pin and disk. The lubricant applied is No. 46 hydraulic oil (46# oil) with a viscosity of 46 mm2/s at 40 Celsius degrees. Before processing the surface texture, the disk surface is polished with a metallographic polishing instrument to achieve a surface roughness of Ra0.3.

Table 1.

The main chemical composition of GCr15 steel.

Table 2.

The chemical composition of the CuZn40 brass alloy.

2.2. Surface Texturing

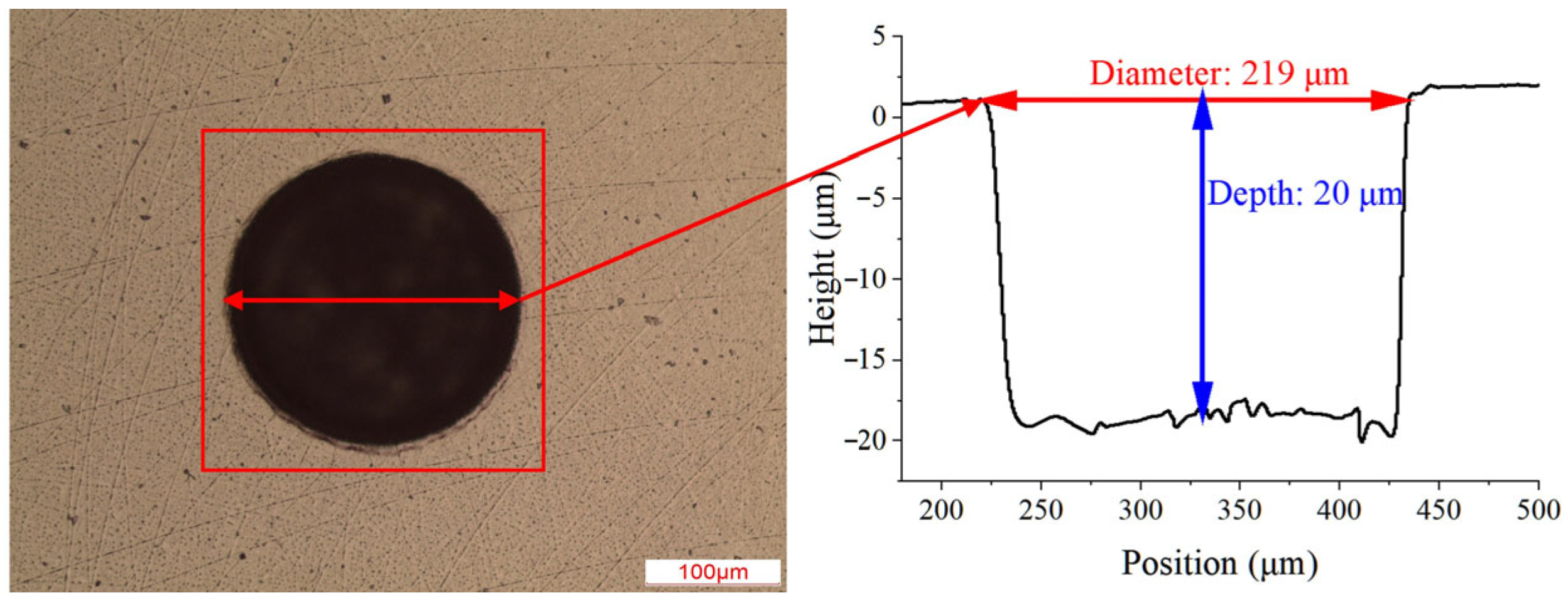

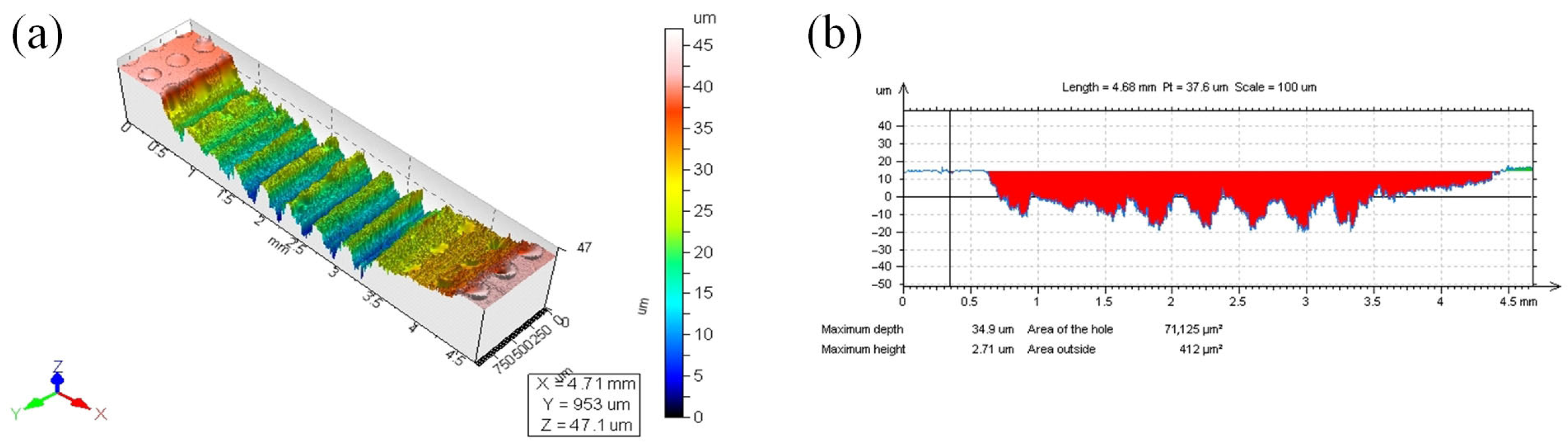

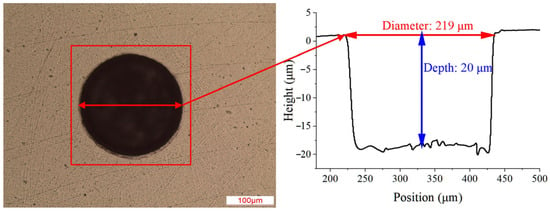

To better elucidate the relationship between texture density and abrasive particle concentration, this paper focuses on a single surface texture parameter. It has been demonstrated that a texture with a depth-to-diameter ratio of 0.1 [37] and a depth of 20 μm [38] exhibits optimal friction performance. Referring to the conclusion of the above paper, this paper used laser surface texturing to create circular textures on the surface of the GCr15 disk, featuring a depth of 20 μm and a constant texture diameter of 0.219 mm, which takes into account the size of the abrasive particles. The optical profile and specific parameters of the texture are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The Optical profile of the texture with specific parameters.

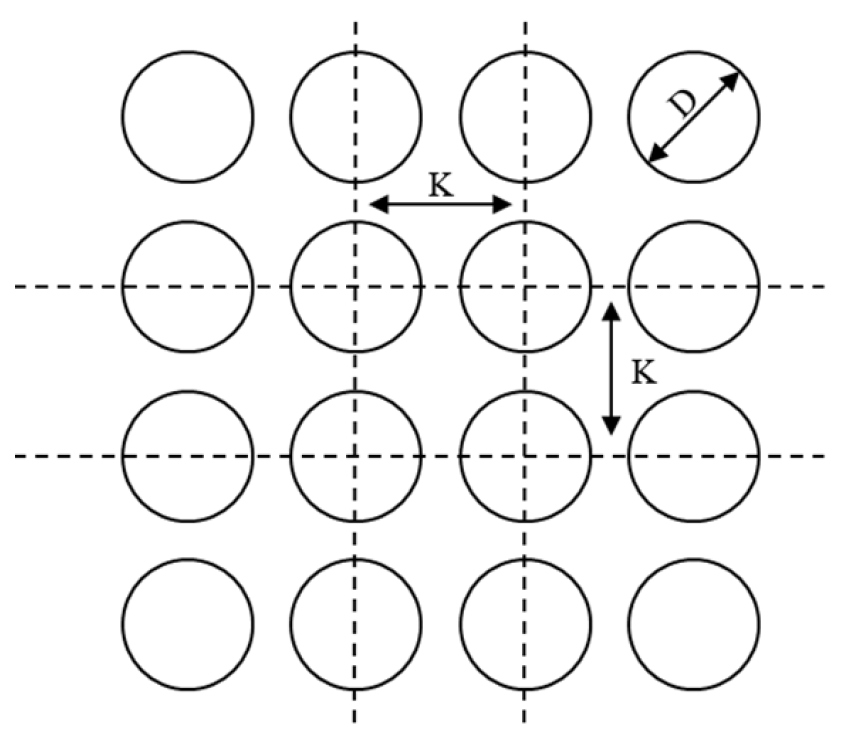

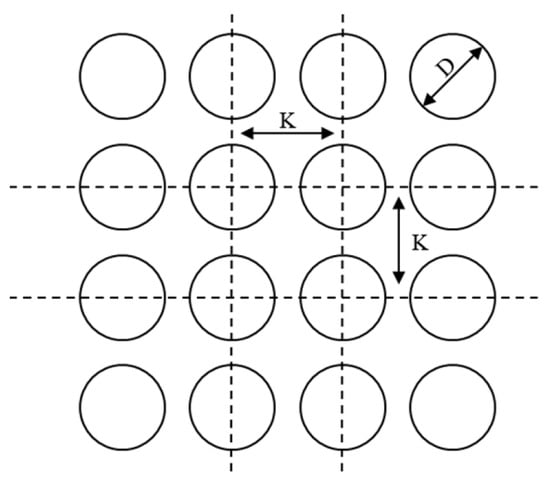

The texture density is calculated as follows:

where

is the texture density;

is the area of the texture ();

is the area of the texture unit ();

is the diameter of the texture; and

is the variable length of the texture unit as shown in Figure 3. Similar descriptions of textures can be found in the literature [38].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of texture arrangement.

2.3. Al2O3 Particle Parameters

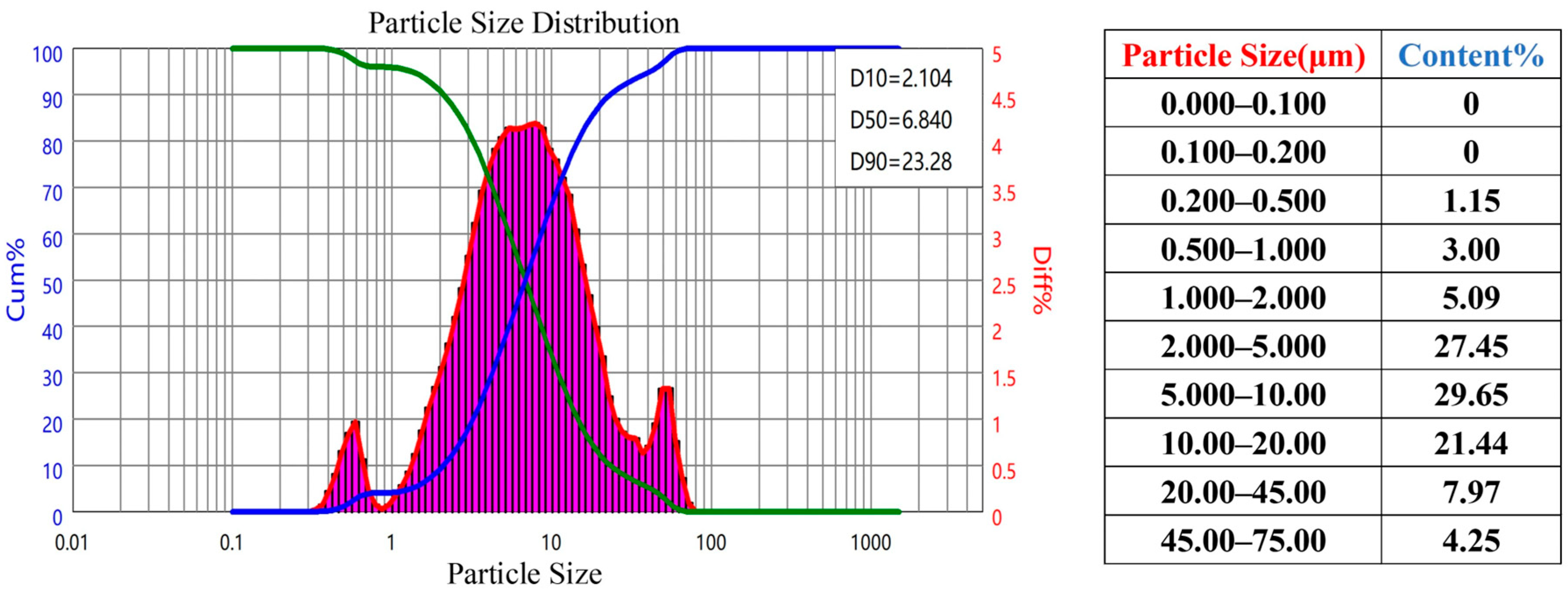

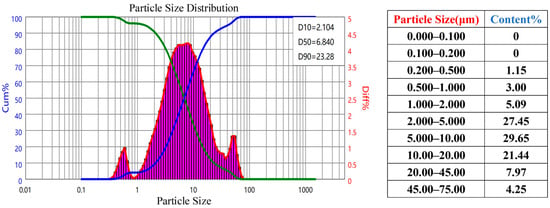

The size of the abrasive particles has an important influence on friction. To examine how abrasive concentration affects the lubricating performance of textured surfaces, this experiment added precisely measured alumina particles into No. 46 hydraulic oil. The parameters for the abrasive content are detailed in Table 3. The average diameter of the chosen alumina particles is 7 μm. The size distribution of the alumina particles is analyzed using a Bettersize 2600E laser particle size analyzer (Dandong Bettersize Instruments Ltd., Dandong City, China), with the results shown in Figure 4. The texture depth of 20 μm was chosen to be approximately three times the average abrasive particle diameter (7 μm), ensuring sufficient capacity to capture particles and prevent them from escaping the texture during sliding. The texture diameter of 0.219 mm is significantly larger than the particle size to avoid clogging of the texture by individual particles while still maintaining a high density of storage sites.

Table 3.

The Experimental parameters of the wear tests.

Figure 4.

Al2O3 particle size distribution.

To create lubricant samples with various concentrations of abrasive particles, a precise mass of alumina particles (Al2O3) is weighed and added into No. 46 hydraulic oil. After thorough mixing, the abrasive particles are uniformly dispersed in the oil. Three lubricant samples with different concentrations of abrasive particles were successfully prepared: 0%, 5%, and 10%. The specific parameters for each sample are listed in Table 3. These samples are subsequently used in tribological tests to evaluate particle concentration effects on lubrication performance.

The three abrasive concentrations (0%, 5%, and 10%) were selected to represent clean, light, moderate, and severe contamination levels commonly encountered in lubrication systems operating under particle-laden conditions. The chosen range is consistent with documented sand contamination levels observed on sand-molding machine guide rails [39], ensuring relevance to both hydraulic and other heavy-load lubricated interfaces.

2.4. Wear Testing

Prior to the experiment, the GCr15 disks and brass pins are cleaned using deionized water for 2 min to remove any contaminants. They are then securely mounted on the test bench and their surfaces are wiped down with anhydrous ethanol for further purification. As shown in Figure 1, the pre-mixed oil is poured into the oil reservoir to ensure complete coverage of the disk surface. During the experiment, the base containing the disk moved in a uniform reciprocating motion, while the upper specimen pin remained stationary. Motor speed was maintained at 200 rpm, while the friction reciprocating distance was set at 10 mm, which corresponds to a reciprocating speed of 0.066 m/s. A normal load of 100 N was applied to the pin so that the contact pressure is about 8.0 MPa. The ambient temperature was controlled at 25 °C throughout the experiment. Each experiment lasted for 1800 s and each condition was repeated three times to reduce the experimental error. The specific experimental parameters and working conditions are given in Table 3. After the experiment, the GCr15 disk wear surface is observed by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM, Leica DCM3D, Frankfurt, Germany) and Optical Microscopy (OM, Leica DMI 3000 M, Frankfurt, Germany) to evaluate the lubricating performance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Coefficient of Friction

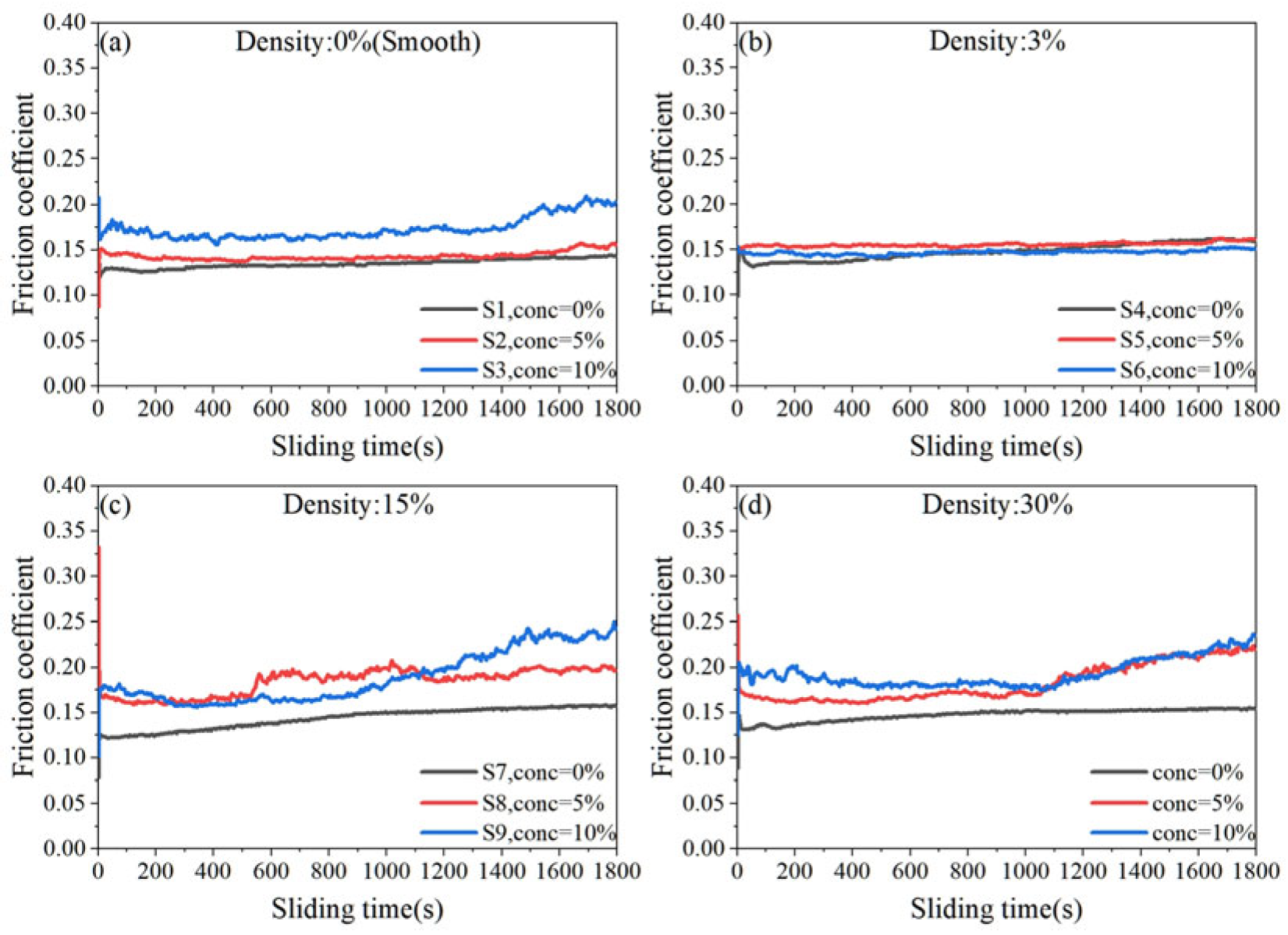

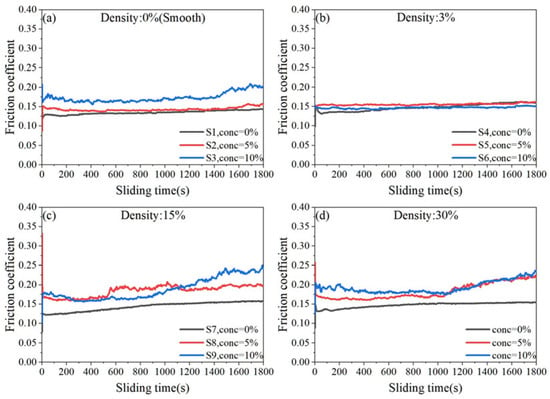

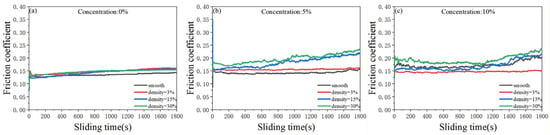

Time evolutions of the friction coefficient are presented in Figure 5, for the same density textured surface at different concentrations. For the smooth surface (Figure 5a), the curve S2 shows that the friction coefficient starts at 0.151 for the first 20 s, drops sharply to 0.139 after 300 s and stabilizes, then gradually rises after 1400 s, and finally stabilizes near 0.154. The curve S3 has an initial friction coefficient of 0.160, which quickly rises to 0.183, then slowly drops to 0.165 and remains there until 1450 s. After that, it experiences a wave-like increase in amplitude and eventually stabilizes near 0.200. Comparing the three friction coefficient curves, the data indicates that as the abrasive content increases, the friction coefficient increases, producing more pronounced fluctuations. The abrasive particles act as a third body in the friction process, increasing the surface unevenness and roughness of the specimen, thereby increasing friction [40]. This phenomenon indicates that the number of abrasive particles significantly affects the friction properties of smooth surfaces.

Figure 5.

Friction coefficient curves for the same density textured surface at different concentrations. (a) Density of 0%; (b) density of 3%; (c) density of 15%; (d) density of 30%.

For the texture with a density of 3% (Figure 5b), the curve S5 shows that the friction coefficient remains stable at approximately 0.153 for the first 840 s, then slowly increases and stabilizes at 0.160. The curve S6 exhibits a pattern of decreasing, stabilizing, and then increasing, but the overall change amplitude is relatively small, with a fluctuation of only 0.005. Compared to the smooth surface, the fluctuation of the friction coefficient curve for a high concentration of abrasive chips on textured surfaces is significantly slower than on smooth surfaces. This is because the texture has the ability to store abrasive particles [41], which can reduce the impact of abrasive particles on surface roughness, resulting in a more stable friction coefficient performance.

However, the enhancement of lubrication behavior stability is lost at higher texture densities, as shown in Figure 5c,d. The curve S8 shows that the coefficient of friction remains stable around 0.164 until 535 s, then increases sharply and stabilizes around 0.193. The curves S9, S11, and S12 exhibit similar trends, stabilizing around 0.157, 0.183, and 0.185, respectively, within the first 1000 s and then continue to rise to near 0.210, 0.214, and 0.203.

Figure 6 systematically illustrates the influence of texture density on friction behavior under different particle concentrations. The friction coefficient curves for all conditions show an upward trend with sliding time, indicating progressive wear. Under clean lubrication (Figure 6a), the friction coefficients of all samples stabilize rapidly, with texture density exhibiting a negligible effect. Following the introduction of Al2O3 particles (Figure 6b,c), the friction coefficients rise markedly and fluctuate severely due to three-body abrasion. Concurrently, the disparity in friction performance between different texture densities is amplified. Specifically, a higher texture density corresponds to an increased friction coefficient. This trend suggests that an excessively high texture density may compromise the friction-reduction performance in high particle concentrations, potentially due to mechanisms such as particle accumulation at texture edges or loss of texture integrity, which will be further discussed in Section 3.3.

Figure 6.

Friction coefficient curves for the same particle concentrations at different densities. (a) Concentration of 0%; (b) concentration of 5%; (c) concentration of 10%.

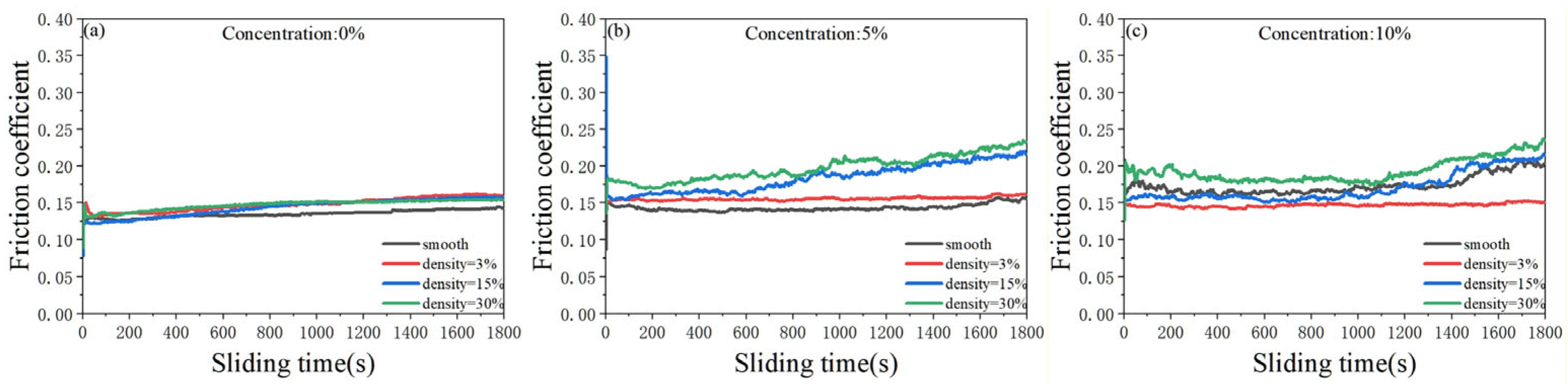

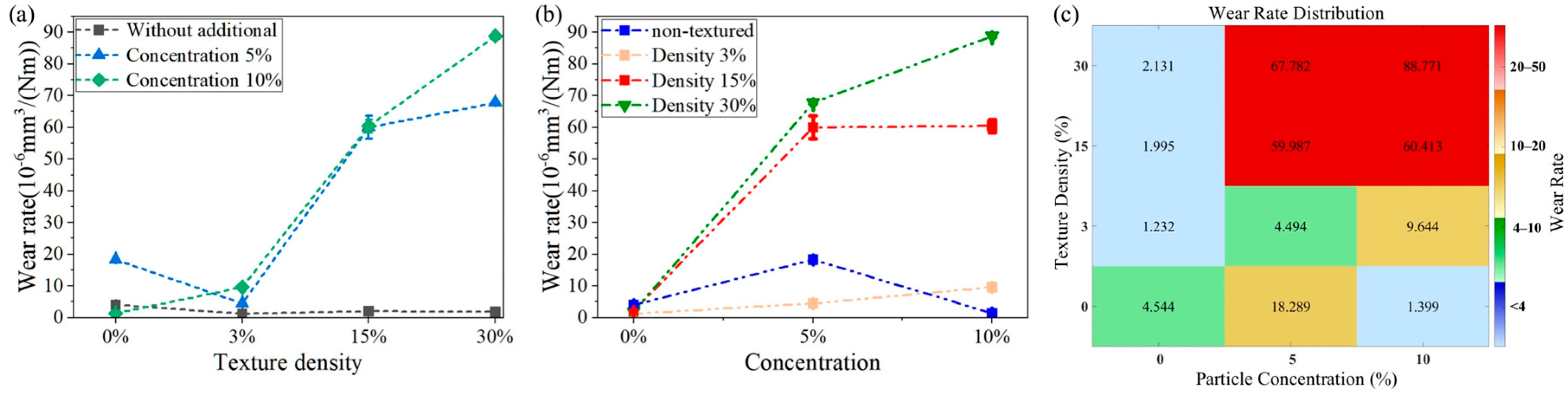

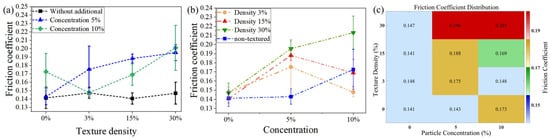

The mean coefficients of friction for all of the conditions are presented in Table 4, with each condition repeated 3–5 times. Figure 7a displays the mean friction coefficients for surfaces with different densities and the influence of the concentration is presented in Figure 7b. We first consider the influence of the texture density. To intuitively illustrate the combined influence, Figure 7c presents a heat map of the average friction coefficient. The color distribution reveals that the coefficient does not increase linearly with either texture density or particle concentration alone; instead, its magnitude is governed by the simultaneous effect of both parameters.

Table 4.

Average friction coefficients under different sample types and concentrations.

Figure 7.

Performance of friction coefficients for different texture densities and abrasive particle concentrations. (a) Friction coefficients for different texture densities; (b) friction coefficients for different abrasive concentrations; (c) heat map of friction coefficient distribution under different combinations of texture density and particle concentration.

For experiments with no abrasive particles, the friction coefficient is reasonably independent of the texture density, as shown in Figure 7a. This phenomenon is attributed to the significant difference in hardness between the brass alloy and the GCr15 test pieces. Under heavy-load conditions, the brass alloy is prone to damage and generates abrasive particles, which prevents the formation of a reliable oil film. Consequently, the lubrication effect of the texture is inhibited.

For the abrasive particle concentrations of 5% and 10%, the coefficient of friction generally exhibited an increasing trend with higher texture density. This observation is consistent with the findings reported by Chen et al. [42]; they investigated the friction performance of a DLC-film textured surface of a high-pressure dry gas sealing ring. Dong et al. [43] also noted that the coefficient of friction increased with elevated texture density. The rise in texture density leads to a reduction in inter-texture distance, a decrease in the smooth area, and a decline in overall surface smoothness. Consequently, these changes enhance the resistance to the motion of the friction pair, resulting in an elevated coefficient of friction and the formation of more furrows during the friction process. For further details, refer to Section 3.3.

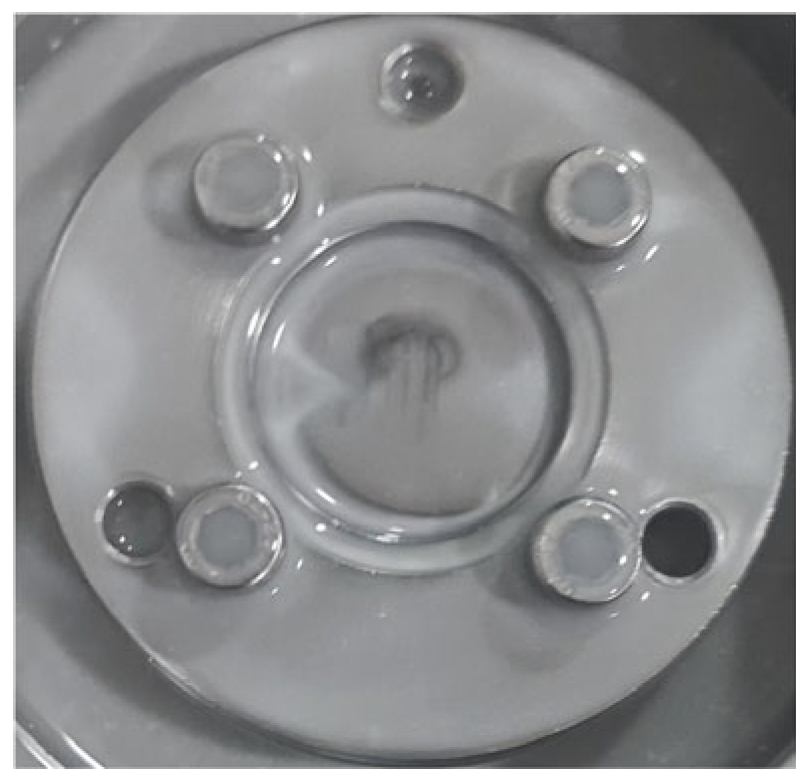

The influence of the particle concentration is subsequently considered. For non-textured surfaces, the coefficient of friction increased with an increase in abrasive particle concentration. When the texture density is high, for example, at a texture density of 30%, the coefficient of friction significantly increased with an increase in abrasive particle concentration. A similar situation is also found in Dong et al. [43], which pointed out that abrasive debris destroyed the lubricating film between the friction pairs, reducing their tribological performance. However, for medium-density textured surfaces, such as those with a surface texture density of 3% and 15%, a decrease in the coefficient of friction occurred at high particle concentrations. This is because, compared with high-density textured surfaces, medium-density surfaces are subjected less to impact grinding and retain a certain texture function. Meanwhile, high-concentration abrasive debris can form a solid lubrication film on the surface [44]. To visually confirm the composition of this lubrication film, Figure 8 (before-cleaning image of the lower specimen) is presented, showing white Al2O3 particles, black mixed metal debris (from both the GCr15 disk and the CuZn40 pin wear), and residual hydraulic oil. The Al2O3 particles act as hard abrasive components dispersed in the oil, while the mixed metal debris serves as soft metallic fillers. This mixed phase reduces shear resistance during sliding, which is consistent with the observed friction coefficient reduction in medium-density textured surfaces under high particle concentrations (e.g., 5% and 10% in Figure 7b). Notably, the solid lubrication film initially covers the texture topography, preserving its structural integrity and enhancing the lubrication reservoir function under abrasive conditions. However, as sliding progresses, the film deteriorates due to abrasive wear, leading to a loss of protection and a subsequent rise in the friction coefficient (evident in Figure 6c, where the coefficient remains stable for the first 1000 s before increasing sharply). This deterioration aligns with the texture degradation process described in Section 3.3, where the gradual wear of the textured structure reduces its ability to trap particles, ultimately triggering functional failure.

Figure 8.

Before-cleaning optical image of the lower GCr15 specimen showing Al2O3 particles (white), mixed metal debris (black), and residual hydraulic oil after tribological testing at 10% abrasive concentration.

3.2. Wear Rate

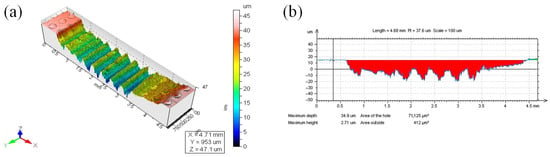

As shown in Figure 9a, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM, Leica DCM3D, Germany) is used to characterize the specimens, enabling the acquisition of wear volume and the calculation of wear rate. To ensure a more accurate derivation of the wear volume, each specimen is rinsed with a 1 min stream of water before imaging. The wear rate is calculated as follows:

where

Figure 9.

Surface wear maps of the GCr15 disk captured by CLSM. (a) three-dimensional topography; (b) two-dimensional profile.

ΔV is the volume lost (mm3),

is the contact force (N),

is the reciprocating speed (m/s), and

is the experimental time (s). The cross-sectional area of the abrasion mark

(mm2) was calculated from the two-dimensional profile (Figure 9b, area of the hole in red) using CLSM analysis software (Leica Map, version 6.2) with the unworn surface as reference. The scratch length

is the 10 mm reciprocating distance. A summary table of the calculated wear rates is shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Wear rate [10−6 mm3/(Nm)] using different sample types and concentrations.

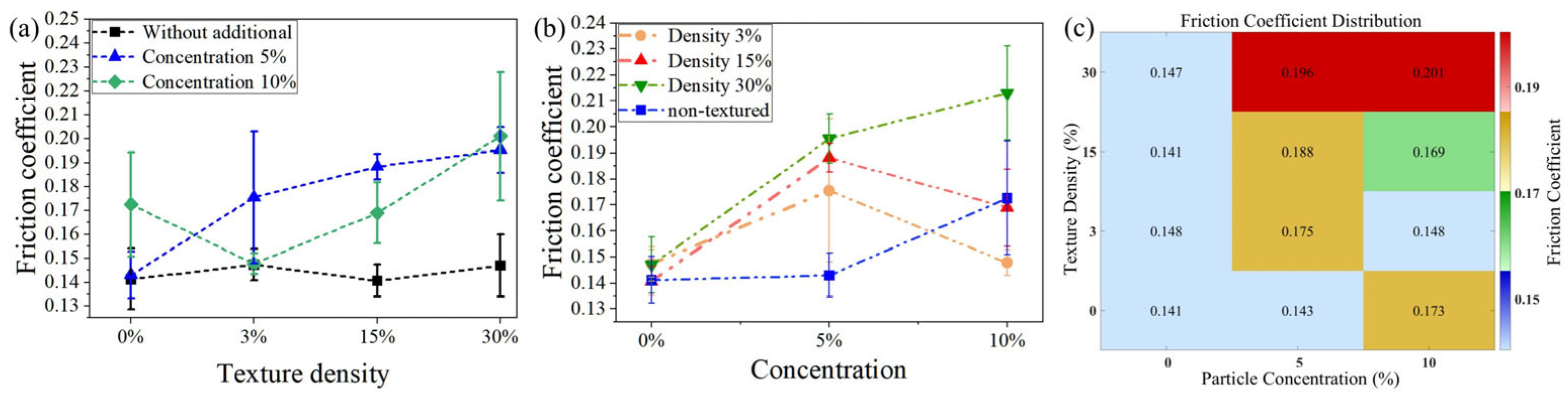

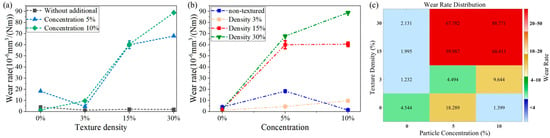

Consistent with the friction coefficient heat map (Figure 7c), the wear rate heat map in Figure 10c demonstrates that the wear rate is also simultaneously dictated by both texture density and particle concentration, rather than by either variable in isolation. The effect of texture density on the wear rate is not significant in the absence of applied abrasive particles. As shown in Figure 10a, even though the texture area ratio increases, the wear rate exhibited a slight tendency to decrease and then increase. However, the overall change is minimal, indicating that the influence of texture density on the wear rate is limited under lubrication conditions with minimal abrasive particles. The effect of texture density becomes significant when abrasive particles are applied. As shown in Figure 10a, the wear rate increased significantly with an increasing texture–area ratio, at 5% and 10% abrasive particle concentrations. Notably, the increase is more pronounced at the higher particle concentration of 10%. This observation suggests that higher texture density adversely affects friction performance under high-particle-concentration conditions. Further analysis indicates an interaction between texture density and particle concentration, as shown in Figure 10b: at low texture densities (3%), the influence of abrasive concentration on wear rate is not significant; in contrast, at higher texture densities (15% or 30%), the wear rate exhibited a marked increase correlating with the rise in particle concentration.

Figure 10.

Wear rate performance at different texture densities and abrasive particle concentrations. (a) Wear rate at different texture densities; (b) wear rate at different particle concentrations; (c) heat map of wear rate distribution under different combinations of texture density and particle concentration.

3.3. Wear Mechanism of Lubrication Containing Abrasive Particles

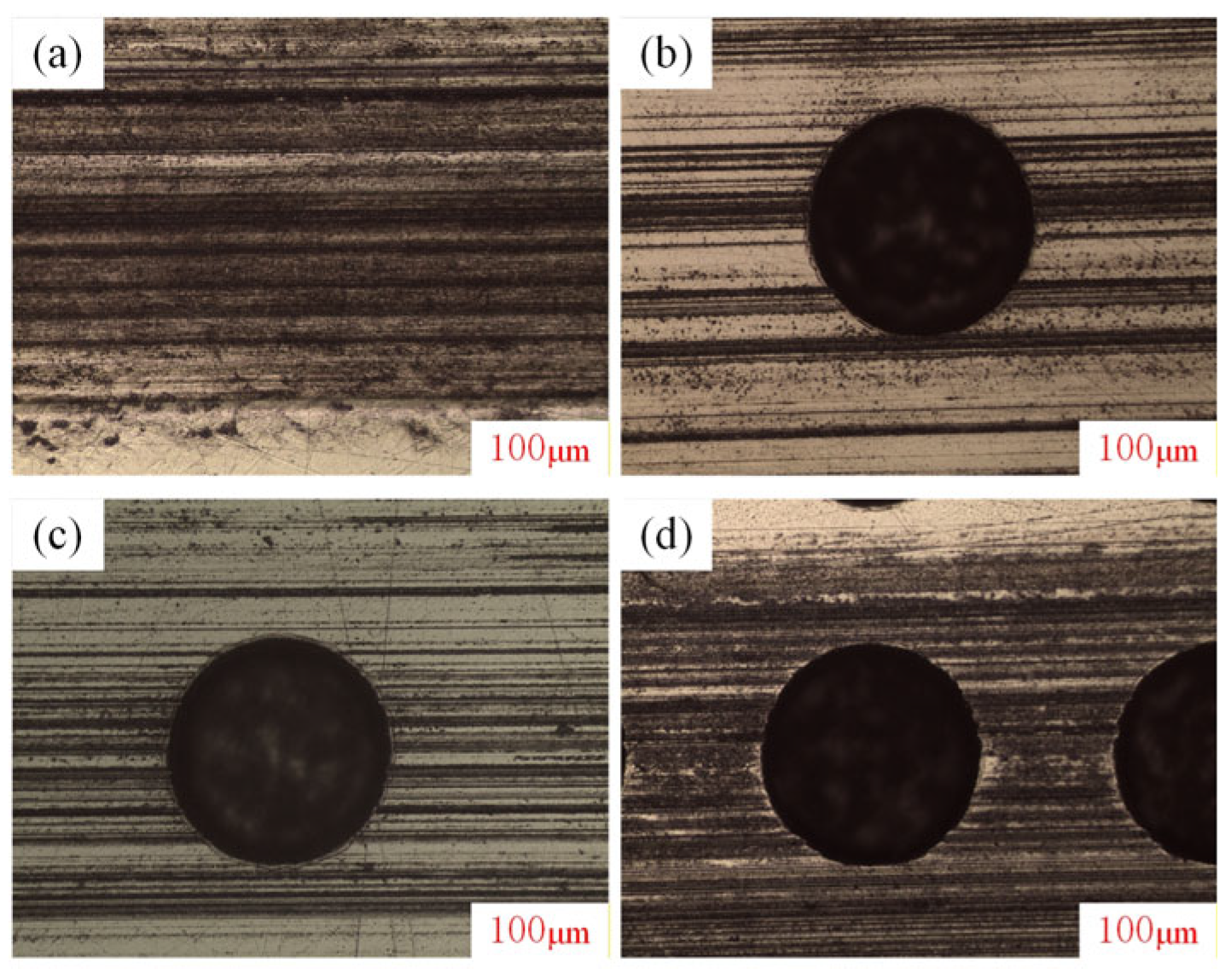

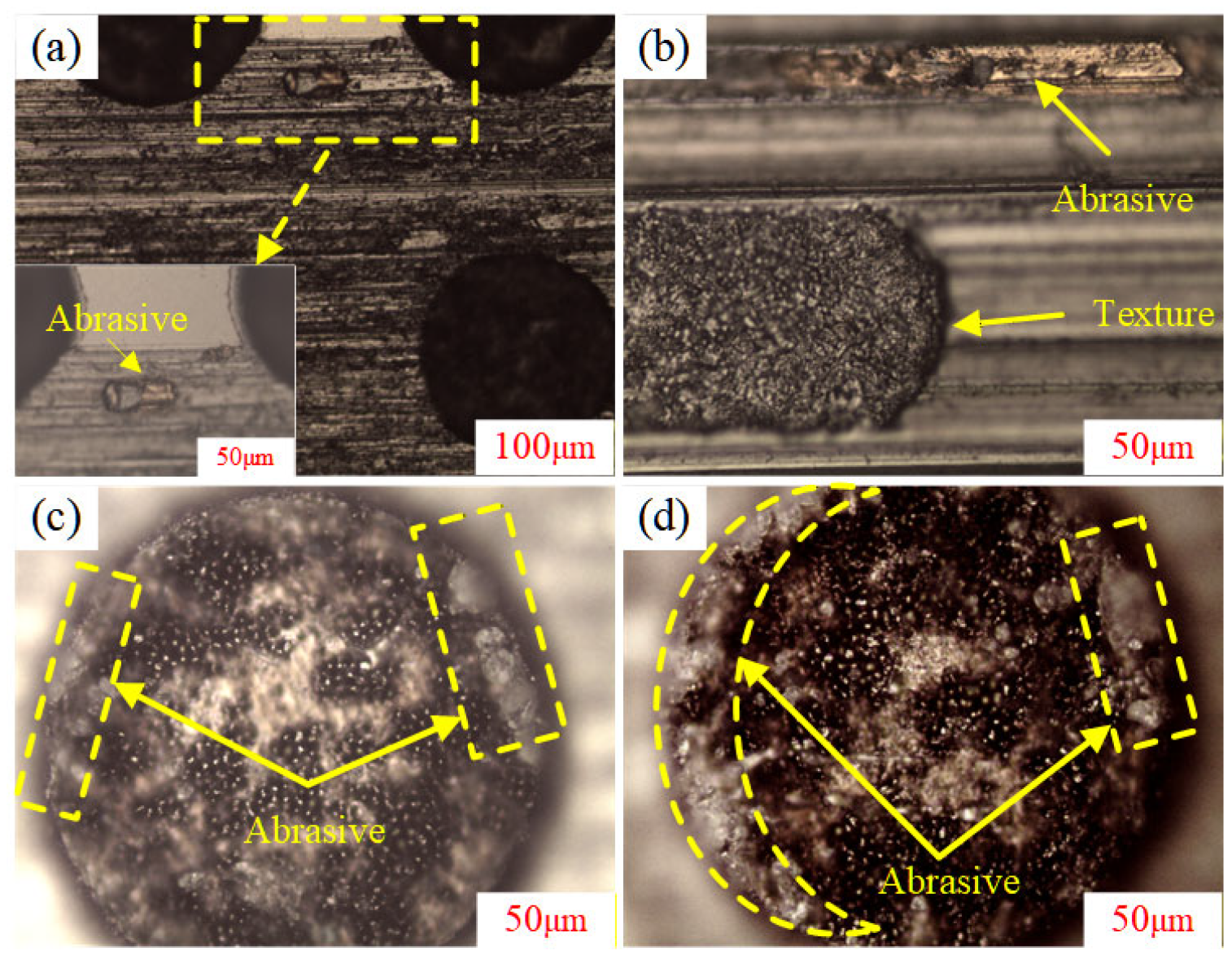

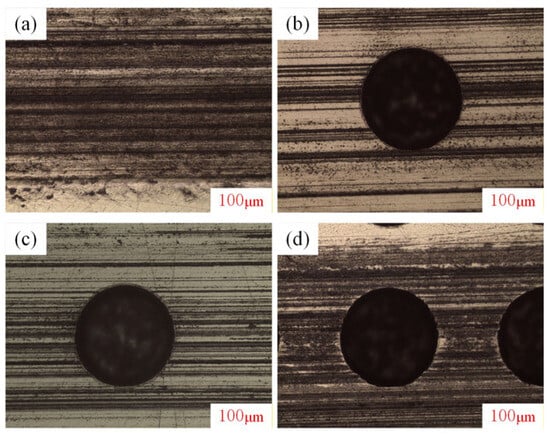

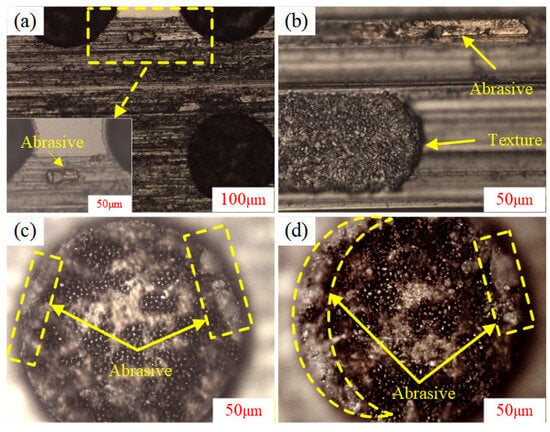

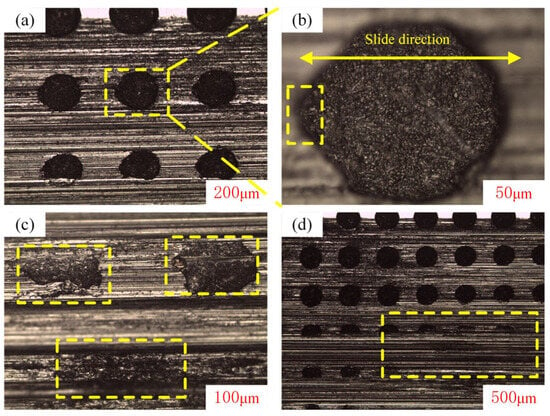

Microscope images of the edges of wear marks are presented in Figure 11a–d, with different area ratios at 0% abrasive concentration. Observations revealed a significant presence of furrows in the wear area of the GCr15 material, indicating that the wear surface experienced substantial plowing action. Consequently, the primary wear mechanism is abrasive wear. When abrasive particles are introduced into the lubricant, particularly under heavy loading conditions, some of these particles may become embedded between the friction partners, leading to furrow formation during relative motion (see Figure 12a,b). This process initiates three-body wear. Furthermore, residual abrasive particles are detected within the texture (Figure 12c,d), suggesting that the texture has a function of storing abrasive particles. This reduces the abrasive grain content in the friction sub-surface, explaining the significantly fewer furrows on the surface of low-density textures compared to non-textured surfaces. Furthermore, as the texture density increases, the distribution of furrows becomes denser (Figure 11b–d), indicating an escalation in wear. Therefore, proper texture design can enhance friction performance and mitigate wear, especially when the abrasive particle concentration is high, when the texture density should not be excessively high to prevent exacerbating the wear phenomenon.

Figure 11.

Wear behavior of different surfaces at 0% abrasive concentration. (a) Non-texture (density of 0%); (b) density of 3%; (c) density of 15%; (d) density of 30%.

Figure 12.

Abrasive particles on abrasion marks. (a) Density of 30% and concentration of 5%; (b) density of 30% and concentration of 10%; (c) density of 3% and concentration of 5%; (d) density of 3% and concentration of 10%.

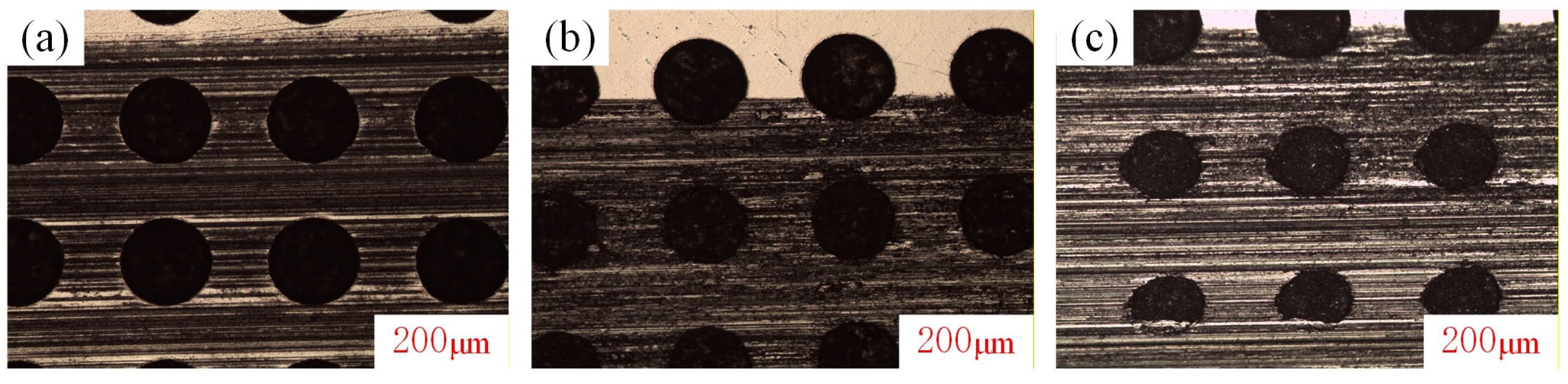

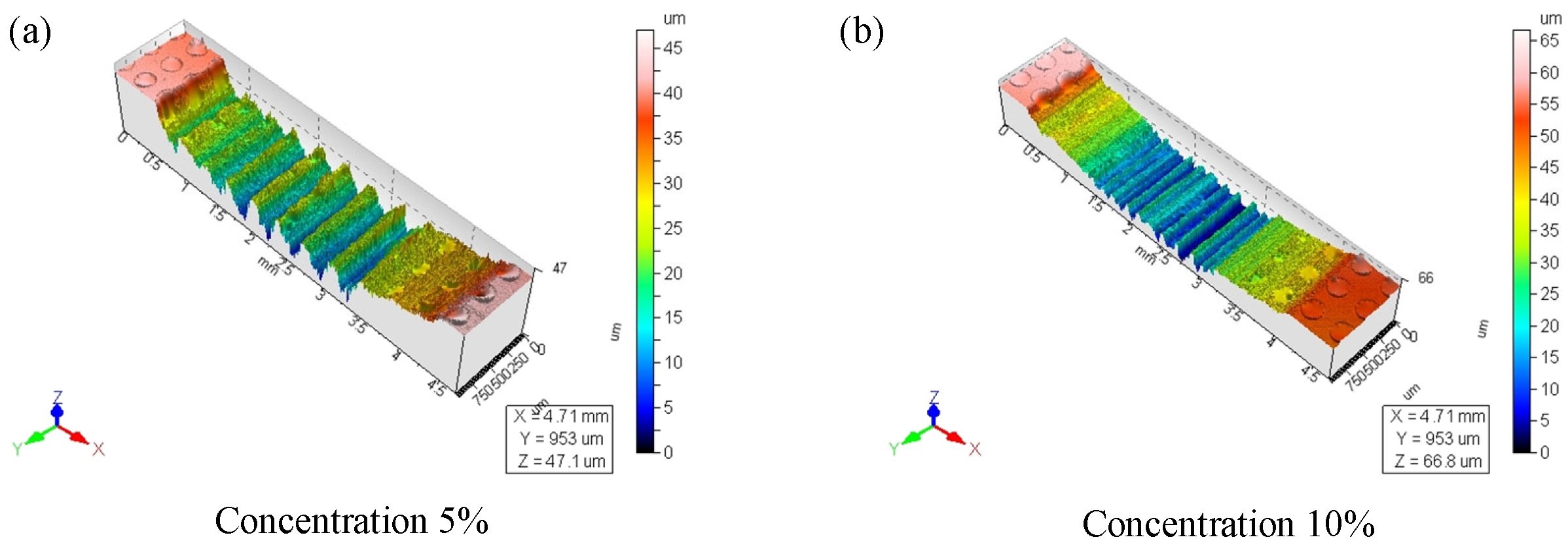

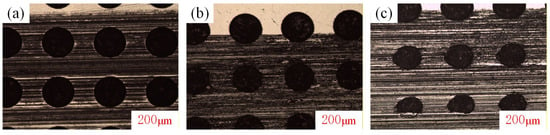

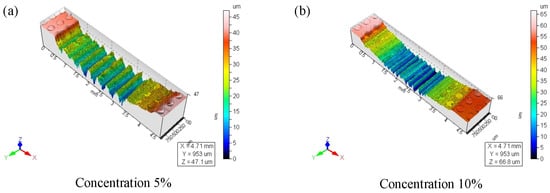

Figure 13 presents microscope images depicting the effect of varying particle concentrations at a density of 30%. At lower particle concentrations (Figure 13a), furrows are relatively sparsely distributed and exhibit a broader morphology, indicating milder wear. As the particle concentration increased, more abrasive particles participated in the grinding process, resulting in the removal of more material and the formation of deeper and denser furrows. Further observation of Figure 13c revealed that the rate of increase in furrow density began to slow with further increases in particle concentration. This phenomenon is attributed to the gradual filling of the space between the abrasive particles, resulting in a relatively balanced interaction among them. The increased wear is primarily reflected in the depth of the furrows, which reached a maximum of 47 μm at a concentration of 5% (Figure 14a) and a maximum of 66 μm at a concentration of 10% (Figure 14b). Additionally, it is evident that the friction process significantly damages the texture.

Figure 13.

Wear on surfaces with a texture density of 30%. (a) Concentration of 0%; (b) concentration of 5%; (c) concentration of 10%.

Figure 14.

Three-dimensional wear map of the textured surfaces at a density of 30%. (a) With particle concentration of 5%; (b) with particle concentration of 10%.

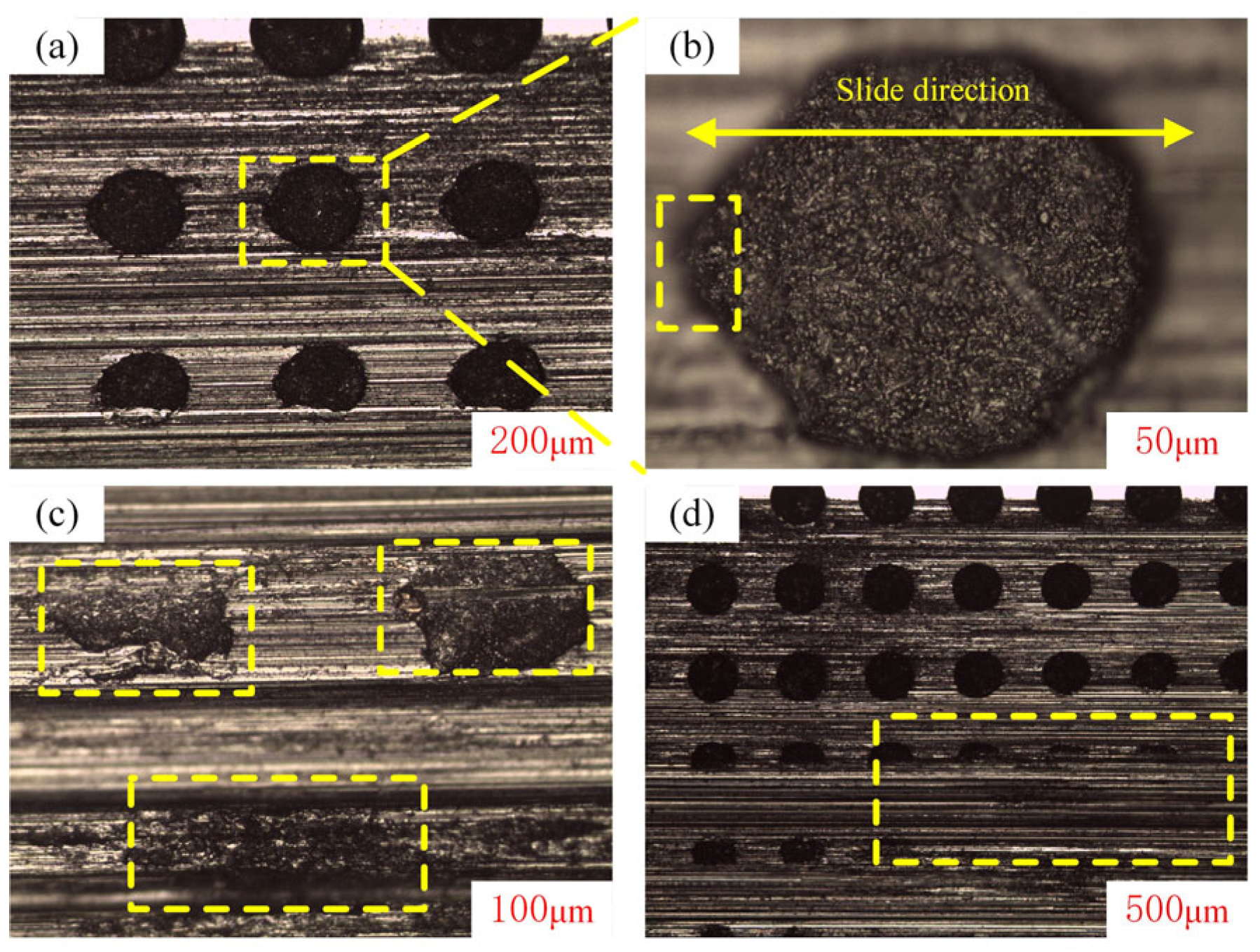

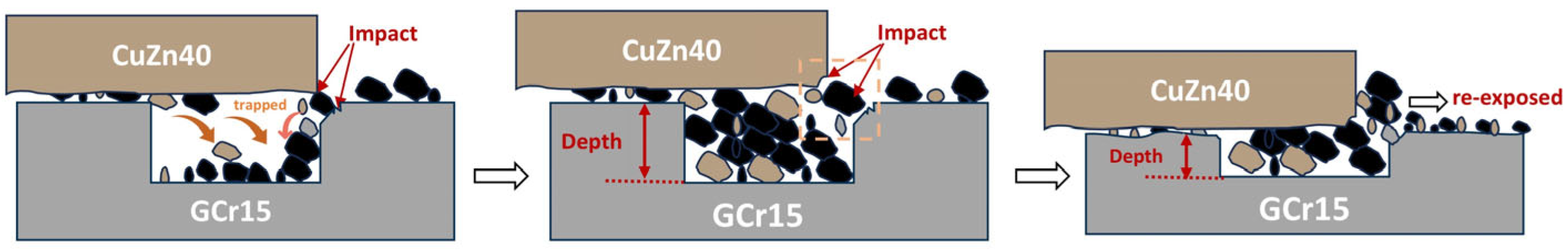

Under conditions of heavy load and high concentrations of abrasive particles, the integrity of the texture is not assured. It can be observed in Figure 12c,d that abrasive particles within the intact texture predominantly accumulated at the edges, specifically on both sides of the sliding direction. This suggests that the frictional pairs transported surface abrasives that impacted texture edges before settling into texture interiors during reciprocation. This reduces the abrasive grain content in the friction sub-surface, explaining the significantly fewer furrows on low-density textures. Simultaneously, Figure 15 illustrates that, for textures with varying degrees of wear, the initial damage occurred in the sliding region. This suggests frictional pairs transported surface abrasives that impacted texture edges before settling into texture interiors during reciprocation.

The progression of wear involves two concurrent material introduction pathways. The schematic diagram of the texture wear degradation mechanism is shown in Figure 16. On one hand, the wear of the counterpart (e.g., the brass pin, Figure 12a,b) generates debris that enters the interface as new abrasive particles, which mix with the initially added Al2O3 particles to form a hybrid third body. On the other hand, the gradual wear of the textured structure itself leads to a continuous reduction in its depth. This causes the abrasive particles originally trapped within the textures to be re-exposed to the contact surface, thereby continuously supplying abrasives for subsequent impact wear. This self-accelerating wear mechanism persists until the textured features are completely worn away (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Destroyed surface texture along the sliding direction for a sample with 30% texture density and 10% abrasive concentration. (a) microscopic image of the wear mark edge; (b) initial wear damage located in the sliding direction; (c) different degrees of wear and tear; (d) almost complete disappearance of the texture features.

Figure 15.

Destroyed surface texture along the sliding direction for a sample with 30% texture density and 10% abrasive concentration. (a) microscopic image of the wear mark edge; (b) initial wear damage located in the sliding direction; (c) different degrees of wear and tear; (d) almost complete disappearance of the texture features.

Figure 16.

Schematic showing abrasive particle generation, trapping, and texture degradation during reciprocating sliding.

Figure 16.

Schematic showing abrasive particle generation, trapping, and texture degradation during reciprocating sliding.

This dynamic wear process ultimately triggers functional texture failure, quantifiable by the critical onset time of a sharp increase in the friction coefficient. As demonstrated in Figure 6c, at a particle concentration of 10%, the coefficient of friction remained relatively stable during the first 1000 s for both 15% and 30% texture density samples, followed by a sharp increase. This observation identifies the 1000 s duration as the critical temporal threshold for texture degradation under these severe conditions.

Consequently, in terms of overall friction performance, the texture did not contribute positively to friction reduction, particularly in environments with high concentrations of abrasive particles.

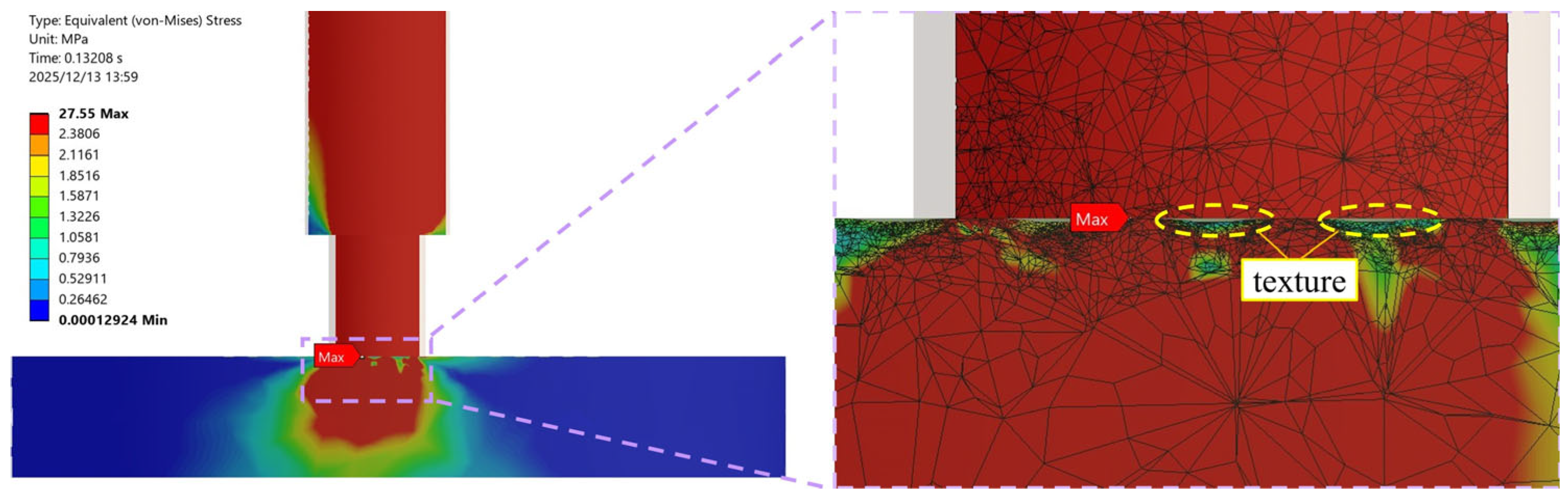

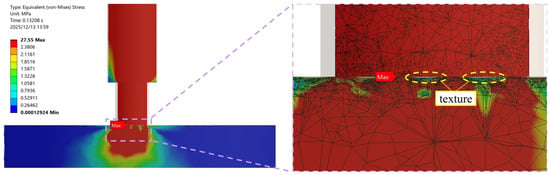

To further elucidate the mechanism behind the detrimental effect of high texture density, a simplified finite element analysis was conducted using ANSYS Workbench (version 2024 R2) under dry contact conditions (no abrasive particles) to study the influence of texture on the surface stress distribution, as shown in Figure 17. The stress distribution results clearly show that stress is primarily concentrated at the plane between texture features. This finding provides a crucial complement to our experimental observations: at high texture densities, the reduction in effective load-bearing smooth area forces the contact pressure to be distributed over smaller, isolated planar regions. This not only increases the resistance to motion but also generates localized stress concentrations, which weaken the material and thus dramatically aggravate abrasive wear when particles are present. This is one of the reasons for the sharp increase in wear rate of high-density textures (15% and 30%) under high concentrations of abrasive particles.

Figure 17.

Stress distribution in textured surfaces.

3.4. Practical Design Guidelines for Texture Selection

Based on the experimental data summarized in Table 4 and Table 5, a comprehensive guideline for selecting optimal surface configuration under abrasive-laden boundary lubrication is proposed (Table 6). This guideline assists engineers in designing surfaces for heavy-load applications (contact pressure approximately 8 MPa) with varying contamination levels, considering both friction and wear performance.

Table 6.

Engineering guidelines for texture selection under abrasive-laden boundary lubrication.

Under clean lubricant conditions (0% particulate), surface topography is selected primarily for manufacturing simplicity because the friction coefficients of the competing configurations are statistically indistinguishable. When the oil is contaminated, two critical design trade-offs emerge. At 5% contamination, non-textured surfaces minimize friction for energy-efficient short-duration applications, whereas 3% textures reduce wear rate by 75% (from 18.3 to 4.5 × 10−6 mm3/Nm) for extended service life. At 10% contamination, 3% texture reduces friction by 15%, but increases the wear rate by a factor of 6.9 relative to non-textured surfaces. Overall, under heavy-load, abrasive-laden boundary lubrication, elevated texture densities (>15%) consistently produce adverse tribological performance, whereas low-density textures (3%) or non-textured surfaces represent more favorable configurations based on application-specific priorities.

Although the present experiments were intentionally run in a boundary-lubrication regime, the same texture-density question is often asked for hydrodynamic sliding, where a full oil film separates the surfaces. Numerous studies have demonstrated that micro-texture generally improves lubrication performance under full-film conditions by enhancing hydrodynamic lift and oil entrainment [6,12,21], a benefit that stands in stark contrast to the wear-accelerating effect observed in the current particle-laden boundary regime. This is the opposite trend to the boundary-lubrication recommendation given in Table 6, emphasizing that lubrication regime must be the first selection filter in texture design.

4. Conclusions

In summary, the effects of texture density and particle concentration on the wear resistance of GCr15 textured samples were investigated. The influences of abrasive particles on the texture were examined under conditions of low speed, heavy load, and boundary lubrication.

The specific research points are summarized as follows:

- The synergistic effect between texture density and particle concentration is a critical determining factor for friction performance. Under clean lubrication conditions (0% particles), the effect of texture density on the coefficient of friction was negligible. However, when abrasive particles were present, the coefficient of friction increased significantly with rising texture density. This is attributed to the increased number of texture edges at higher densities, which exacerbate impact wear from particles and reduce the effective load-bearing smooth area. Notably, at high particle concentrations, the wear rate deteriorated sharply with increasing texture density, indicating inherent drawbacks for high-density textures under such operating conditions.

- Textures influence friction behavior through particle entrainment and removal mechanisms. An increase in abrasive particle concentration significantly raised the coefficient of friction on smooth surfaces, as particles acted as a third body to intensify surface plowing. In contrast, textured surfaces exhibited a unique response: their dimple structure could capture and store abrasive particles, effectively removing them from the primary frictional contact interface and thereby reducing the abrasive content in the friction subsurface. Concurrently, the lubricant storage function of the texture, combined with the captured particles and wear debris, formed a mixed lubrication layer. This layer mitigated the friction increase caused by high particle concentrations to a certain extent. However, this beneficial effect is limited by the integrity of the texture.

- Texture degradation under severe conditions was observed; heavy loads combined with high particle concentrations caused progressive wear at texture edges, reducing texture depth until complete feature disappearance. This self-accelerating wear process re-exposes trapped particles to the contact surface, ultimately leading to texture failure. The relatively large dimples (diameter 0.219 mm, depth 20 μm) were designed to optimize particle–dimple interaction—the depth was approximately three times the particle diameter (7 μm) for sufficient storage capacity, while the larger diameter prevented clogging. However, this design’s integrity was compromised under severe conditions, leading to degraded friction performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing—original draft, D.W.; Resources, Writing—original draft, W.Z.; Investigation, Visualization, Writing—review and editing, H.D.; Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, X.W.; Investigation, Validation, Writing—review and editing, W.H.; Data Curation, Visualization, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [(D.W.) Grant No. 52375068, (X.W.) Grant No. 12202399], Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province [(X.W.) Grant No. LY24A020004, (W.H.) Grant No. ZCLY24E0202].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ma, X.; Wang, Q.J.; Lu, X.; Mehta, V.S. Piston surface design to improve the lubrication performance of a swash plate pump. Tribol. Int. 2019, 132, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zuo, Z.; Jia, B.; Feng, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Smallbone, A.; Paul Roskilly, A. Comparative analysis on friction characteristics between free-piston engine generator and traditional crankshaft engine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Liu, G.; Xie, S.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Z.; He, D. The effect of interfacial wear debris on the friction-induced stick-slip vibration. Tribol. Int. 2024, 199, 109999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Larbi, A.; Dong, H.; Wang, D.; Li, S. A comparative investigation on wear behaviors of physical and chemical vapor deposited bronze coatings for hydraulic piston pump. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zum Gahr, K.H.; Schneider, J. Surface modification of ceramics for improved tribological properties. Ceram. Int. 2000, 26, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropper, D.; Wang, L.; Harvey, T.J. Hydrodynamic lubrication of textured surfaces: A review of modeling techniques and key findings. Tribol. Int. 2016, 94, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labiapari, W.d.S.; de Alcântara, C.M.; Costa, H.L.; De Mello, J.D.B. Wear debris generation during cold rolling of stainless steels. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2015, 223, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, M.; Almqvist, A.; Rosenkranz, A.; Fillon, M. Numerical micro-texture optimization for lubricated contacts—A critical discussion. Friction 2022, 10, 1772–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, R.; Xiang, J. The performance of textured surface in friction reducing: A review. Tribol. Int. 2023, 177, 108010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.B.; Walowit, J.A.; Allen, C.M. A Theory of Lubrication by Microirregularities. J. Basic Eng. 1966, 88, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tala-Ighil, N.; Fillon, M.; Maspeyrot, P. Effect of textured area on the performances of a hydrodynamic journal bearing. Tribol. Int. 2011, 44, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wei, X.; Haidak, G.; Wang, D. Numerical study on the lubrication performance of oil films in textured piston/cylinder pairs. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 073606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hua, M.; Dong, G.-N.; Zhang, D.-Y.; Chin, K.-S. A mixed lubrication model for studying tribological behaviors of surface texturing. Tribol. Int. 2016, 93, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dai, S.; Dong, G. Designing a bioinspired scaly textured surface for improving the tribological behaviors of starved lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2022, 173, 107594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, H.; Luo, T.; Xiao, G.; Yi, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C. Tribological properties of laser surface texturing modified GCr15 steel under graphene/5CB lubrication. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 3598–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.-x.; Li, B.; Ji, D.-h.; Xiong, G.-y.; Zhao, L.-z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.-n. Effect of Particle Size on Tribological Properties of Rubber/Steel Seal Pairs Under Contaminated Water Lubrication Conditions. Tribol. Lett. 2020, 68, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccoli, M.; Provezza, L.; Petrogalli, C.; Ghidini, A.; Mazzù, A. Effects of full-stops on shoe-braked railway wheel wear damage. Wear 2019, 428–429, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.; Poll, G.; Pape, F. Investigation of the possible applications for microtextured rolling bearings. Front. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 2, 1012343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhao, F.; Wei, X.; Gao, F.; Li, P.; Dong, G. Effect of texture parameters on the tribological properties of spheroidal graphite cast iron groove-textured surface under sand-containing oil lubrication conditions. Wear 2019, 428–429, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Lin, B.; Ren, X.; Li, H.; Diao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sui, T.; Yan, S. Particle size effects on efficiency of surface texturing in reducing friction. Tribol. Int. 2022, 176, 107895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etsion, I. Modeling of surface texturing in hydrodynamic lubrication. Friction 2013, 1, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Zheng, H.; Deng, H.S.; Fang, S.Y.; Wang, C.L.; Luo, G. Study on abrasive wear of textured slider friction pair of horizontal pump. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2025, 239, 1478–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Qu, J.; Xu, J.; Li, C. Effects of double-sided textures matching on friction and wear performance in reciprocating contact interface. Wear 2024, 556–557, 205522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Z. Investigating the Effects of Surface Texture Direction and Poisson’s Ratio on Stress Concentration Factors. Materials 2025, 18, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchenko, A.; Ajayi, O.; Erdemir, A.; Fenske, G. Friction and wear behavior of laser textured surface under lubricated initial point contact. Wear 2011, 271, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladescu, S.-C.; Olver, A.V.; Pegg, I.G.; Reddyhoff, T. The effects of surface texture in reciprocating contacts—An experimental study. Tribol. Int. 2015, 82, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, J.; Muhr, A.; Stephens, I. The effects of surface texture on natural rubber/metal friction at high pressures. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2003, 32, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Lin, N.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wu, Y. Correlation between surface textural parameter and tribological behaviour of four metal materials with laser surface texturing (LST). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 583, 152410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Seguedo, J.L.; Dominguez-Lopez, I.; Barceinas-Sanchez, J.D.O. Effect of surface texturing of UHMWPE on the coefficient of friction under arthrokinematic and loading conditions corresponding to the walking cycle. Mater. Lett. 2021, 284, 129039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Wei, H.; Yang, O.; Deng, L.; Mu, D. Tribological behaviors of laser textured surface under different lubrication conditions for rotary compressor. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, N.; Fan, Z.; Wang, G. Design and research of a heavy load fatigue test system based on hydraulic control for full-size marine low-speed diesel engine bearings. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 288, 116174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yuan, J.; Hu, L.; Lyu, B. Multidimensional Study on the Wear of High-Speed, High-Temperature, Heavy-Load Bearings. Materials 2023, 16, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Tang, B.; Wang, S.; Han, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, M.; Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Jiao, J.; Jiang, H. High-speed and heavy-load tribological properties of hydrostatic thrust bearing with double rectangular recess. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 21273–21286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Li, W.; Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Zhang, K.; Ma, F.; Chen, X.; Feng, R.; Liaw, P.K. The influence of WS2 layer thickness on microstructures and mechanical behavior of high-entropy (AlCrTiZrNb)N/WS2 nanomultilayered films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 433, 128091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Puoza, J.C.; Zhang, P. The influence of laser surface texture on the tribological properties of friction layer materials in ultrasound motors. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2022, 236, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Su, G.; Fan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, C. Investigation of the Surface Characteristics of GCr15 in Electrochemical Machining. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.; Greiner, C.; Schneider, J.; Gumbsch, P. Efficiency of laser surface texturing in the reduction of friction under mixed lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2014, 77, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Puoza, J.C.; Zhang, P.; Xie, X.; Yin, B. Experimental Analysis of Grease Friction Properties on Sliding Textured Surfaces. Lubricants 2017, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhao, F.; Gao, F.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Dong, G. Study on tribological behavior of grooved-texture surfaces under sand–oil boundary lubrication conditions. Tribol. Trans. 2021, 64, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.L.; Gao, F.; Tao, H.L.; Han, X.M.; Fu, R. Correlations between third body evolution and tribological performance of copper-matrix friction material under abrasive paper interference conditions. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2018, 232, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Fu, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, J.; He, Y.; Ji, J. Effects of Micro Dimple’s Topography Parameters on Wear Resistance of Laser Textured AlCrN Coating Under Starved Lubrication Condition. Surf. Topogr. Metrol. Prop. 2021, 9, 045005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ding, X.; Yu, S.; Zhang, W. Friction performance of DLC film textured surface of high pressure dry gas sealing ring. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.L.; Yuan, C.Q.; Bai, X.Q.; Yang, Y.; Yan, X.P. Study on wear behaviours for NBR/stainless steel under sand water-lubricated conditions. Wear 2015, 332–333, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, P.; Ye, F. Wear performance of the WC/Cu self-lubricating textured coating. Vacuum 2018, 157, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).