Abstract

The degree diameter problem is a quest to determine the largest graph in terms of vertices satisfying given degree and diameter constraints. The largest possible graphs that can exist and that are subject to degree and diameter constraints are called Moore graphs. Since Moore graphs are rare, researchers are eager to build graphs closer to Moore graphs. This paper discusses the possibility of constructing graphs closer to Moore graphs, keeping a fixed order and minimizing the number of vertex pairs that break the diameter constraint, and suggests a new general relative index that measures the closeness to optimality. Based on the proposed index, it is highlighted that some of the graphs constructed in this work are closer to Moore graphs than the existing best results in the degree diameter problem. Furthermore, a fitness landscape analysis is conducted to identify the nature and the difficulty of the problem. This new method can be considered a new approach to constructing graphs closer to Moore graphs.

MSC:

05C85; 05C12; 90C27

1. Introduction

The degree diameter problem is a quest to determine the largest graph subject to given degree and diameter constraints [1]. The degree diameter problem intends to construct the largest graph in terms of vertices without exceeding diameter k and degree d. The largest number of vertices that can be acquired by a graph with degree d and diameter k is called a Moore bound. Graphs that acquire the Moore bound are called Moore graphs [2]. The Moore bound for degree d and diameter k is derived from adding the vertices of k layers of a d regular expansion tree [1]. Thus, the number of vertices of a Moore graph with degree d and diameter k is provided by the following:

Moore graphs are rare. When the degree is 2 and the diameter is k, the Moore graphs are cycles with vertices. It has already been proven that Moore graphs do not exist when both the degree and diameter are greater than 2. When the diameter is 2, Moore graphs exist for degrees 2, 3, and 7, namely the Pentagon, Peterson, and Hoffman–Singleton graphs. In [2], the authors suggest that a Moore graph may possibly exist for degree 57 and diameter 2, which is named the 57-regular Moore graph. However, the existence of this graph is undetermined and it remains an open problem. It has been observed that the 57-regular Moore graph cannot be vertex-transitive [3], in contrast to all existing Moore graphs.

Motivated by their rarity, researchers are seeking to determine graphs whose order is closer to the Moore bound. The gap between the number of vertices of a given graph and that of the corresponding Moore graph is called a defect [4]. The optimum graphs for different degrees and diameters are constructed using two approaches. The upper bound can be reduced by proving the non-existence of graphs, and the lower bound can be increased by constructing new graphs. Furthermore, the construction of graphs closer to Moore graphs has been pursued by relaxing the degree and diameter conditions. For instance, the construction of radial Moore graphs requires one to retain an order, degree, and radius equal to those of a Moore graph while allowing the diameter to exceed its radius by one [5]. The existence and the properties of radial Moore graphs have been studied by several researchers [6,7]. The optimum graphs are constructed using various methods, including algebraic and algorithmic methods [8,9].

In addition to the above, numerous related problems and subproblems, such as the degree diameter problem for special graph classes, the degree diameter problem for directed graphs, the degree diameter problem for mixed graphs [1,10], and the maximum degree diameter bounded subgraph problem (MaxDDBS), have been examined in the literature [11,12,13].

The order degree problem is a related problem in graph theory that can be thought of as a complementary aspect of the degree diameter problem within the same theoretical framework. It suggests determining the graph with the lowest diameter when the order and degree of the graph are fixed. This problem is more applicable in practical scenarios than the degree diameter problem since minimizing the average distance with a fixed order, subject to budget constraints, is highly relevant in network design [14]. Optimizing the network efficiency by reducing the average shortest path length (ASPL) while complying with budget constraints and resource limitations is vital in real-world applications, such as in communication networks and transportation systems [15]. The problem can be stated as finding an undirected graph with the minimum diameter, with the number of vertices equal to n and a degree less than or equal to d. If there is more than one graph with the same diameter, a graph with the minimum ASPL is determined.

The concept of generalized Moore graphs was introduced in [16] as a candidate solution for the order degree problem. However, generalized Moore graphs do not exist for all degrees and diameters. The authors in [17] conducted further studies on generalized Moore graphs, developed an algorithm to solve the problem, and provided some reasonable solutions to the problem. The authors in [18] proposed a method to solve some instances of the order degree problem with a new sampling method called Estimation of Distribution Algorithms with Graph Kernels (EDA-GK). The ASPL of the generalized Moore graph can be considered as a lower bound for the ASPL of a graph. A generalized Moore graph can be defined as follows [17].

Definition 1.

Let G be a k-regular graph with order n, and represents the set of all vertices of the graph G. Suppose that represents the set of all vertices where the shortest path length from the vertex is l. Then, a connected k-regular graph of order n is called a generalized Moore graph if all vertices satisfy the following condition:

where, and

Numerous methods and algorithms have been developed to solve cases related to the order degree problem, such as the genetic algorithm, which is an optimization heuristic inspired by natural selection [19]. The authors in [20] proposed a genetic algorithm-based method to produce an approximate solution to the problem, while, in [15], the authors suggested a heuristic method to solve the order degree problem, maximizing the number of pentagons inside the graph. Furthermore, the researchers in [21] proposed three algorithms in order to minimize the diameter of a graph by adding k new edges while satisfying the degree constraint.

In network design, maximizing the number of vertices while minimizing the diameter is crucial in improving performance while minimizing the cost [22]. Therefore, for a given degree and diameter, designing a network as close to a Moore graph as possible possesses significant theoretical value in this scenario. However, since Moore graphs are available only for a few cases, approaching the Moore bound is impossible in most cases. When constructing a graph satisfying degree and diameter constraints, all distances between all pairs of vertices must not exceed the diameter value. However, the Moore bound can be acquired if a few pairs of vertices are released from the diameter constraint. In this paper, we suggest constructing graphs closer to Moore graphs, keeping the order equal to the Moore bound, and minimizing the pairs of vertices that violate the diameter constraint. Furthermore, a new relative index is introduced to measure how close a given graph is to optimality.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the order degree problem for the Moore bound is introduced with a new index to measure the closeness of a graph to optimality. In Section 3, a heuristic algorithm based on simulated annealing is introduced, and the results are presented. In Section 4, a fitness landscape analysis is conducted to identify the problem difficulty. In Section 5, a Latin square-based problem-specific algorithm is suggested, and the conclusions and future developments are described in Section 6.

2. Order Degree Problem for Moore Bound

Let be the Moore bound for degree d and diameter k. Then, the order degree problem for Moore bound is defined as follows.

Problem 1.

Construct a graph minimizing the number of vertex pairs that exceed the shortest path length k when the order is equal to and the maximum degree is d, such that the maximum distance between any given vertices does not exceed .

This problem seeks to build graphs with an order equal to the Moore bound, minimizing the average shortest path length. With this definition, the problem essentially becomes a study of radial Moore graphs minimizing the average shortest path length. Therefore, the problem can be considered as an intersection of the order degree problem and the study of radial Moore graphs. The existence of radial Moore graphs with radius 2 and 3 has already been confirmed [7]. Furthermore, it is known that, for any given radius k, there exists a positive integer such that radial Moore graphs with radius k exist for all degrees [5]. This paper considers the order degree problem for the Moore bound for .

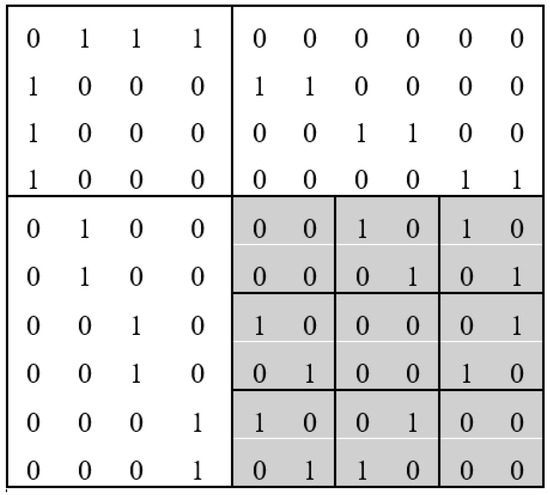

The adjacency matrix A of a Moore graph with degree d and diameter 2 can be described as a -sized block matrix containing four sub-matrices [2]

where L and D are defined as follows.

Let L be a square matrix of size , where is defined as

Let D be a matrix, where for and ,

The sub-matrix P is a block matrix, which consists of permutation matrices, each of size . Permutation matrices are formed by permuting the rows of an identity matrix [23]. All the diagonal blocks are zero, and all the blocks in the first row (and column) of blocks (except the diagonal) are identity matrices. The Moore graphs are obtained by arranging the other permutation matrices in an optimized way. Figure 1 presents the adjacency matrix of the Peterson graph (a Moore graph with degree 3 and diameter 2) for a better understanding. The shaded area of the matrix represents the block matrix P. However, since only a few Moore graphs exist, we consider graphs whose order is equal to that of a Moore graph with diameter 2 and aim to minimize the number of vertex pairs whose distance exceeds 2.

Figure 1.

Adjacency matrix of Peterson graph.

Problem 2.

Construct a graph minimizing the number of vertex pairs that exceed the shortest path length 2 when the order is equal to and the degree does not exceed d, such that the maximum distance between any given vertices does not exceed 3.

The aim of this problem is to construct graphs structurally similar to Moore graphs. The defined problem can also be viewed as an approach to constructing radial Moore graphs with radius 2. The existence problem of radial Moore graphs with radius 2 has already been addressed, and all radial Moore graphs with degree 3 and radius 2 have been constructed [6]. Moreover, some specific families of radial Moore graphs have been studied in the literature [24,25]. However, while the construction of radial Moore graphs aims to minimize the number of vertices with eccentricity 3, this problem focuses on minimizing the average shortest path length of the graph and minimizing the number of vertex pairs with a shortest path length greater than 2. Several quantitative measures can be employed to quantify the similarity or the deviation between two graphs. These measures are theoretically significant as they can be applied to provide insight into the structural similarities and deviations between the graphs. For instance, the graph edit distance (GED), applied in inexact graph matching, indicates the similarity between two graphs through the number of edit operations required to transform one graph into another [26]. The spectral distance of two graphs quantifies the structural similarity between two graphs in terms of the norm of the difference between the spectra of the two graphs [27].

The indices include the Lanzhou index [28], which describes the connectivity of a graph; the harmonic index [29], which calculates the sum of the harmonic means of the degrees of pairs of adjacent vertices; the Wiener index [30], which provides the sum of the shortest path distances between all pairs of vertices in a graph; and the Balaban index [31], which is based on the distances between vertices and measures the cyclicity of a graph. Ref. [32] provides insight into the topological structure of a graph.

Furthermore, these measures can be applied to depict the closeness or deviation of a graph to or from optimality. For instance, defect or excess indicate the number of vertices required to acquire the Moore bound for a given graph and can be considered as a measure of deviation from optimality [4]. However, defining an index to quantify the similarity or deviation between a provided graph and a hypothetical Moore graph in terms of vertex pairs is significant, since the graphs are used to represent the pairwise relationships between entities. For this purpose, a new index, namely the Moore Deviation Index (MDI), is introduced. The MDI is defined as follows.

Definition 2.

Let G be a graph with n number of vertices and maximum degree d; then, the deviation index of graph G with respect to the Moore bound is given by

where is the number of vertex pairs of the hypothetical Moore graph with diameter k and degree d. Furthermore, ρ is the total pairs of vertices and

where represents the number of vertex pairs in which the shortest path length exceeds the diameter constraint by r. Conveniently, it can be observed that the MDI of a Moore graph is 0. As the number of vertex pairs that violate the diameter constraint increases or the size of the graph decreases, the MDI value deviates from zero. The index is sensitive to the vertex pairs that break the diameter constraint.

In earlier studies, ranking measures to indicate the proximity of a radial Moore graph to a hypothetical Moore graph have been applied, such as by Carles Capdevila et al. [6]. When G is a radial Moore graph, the status of a vertex can be defined as . The status vector is a vector that contains all statuses of the vertices of the graph G. Then, the closeness measure is defined as for any integer p, where denotes the of a vector and represents the status vector of the Moore graph with degree d and diameter k. Furthermore, a similar method based on the girths of the vertices has also been employed for the same purpose. However, the two ranking measures described above have only been applied to indicate the proximity of radial Moore graphs to a hypothetical Moore graph. In contrast, we apply the MDI to measure the closeness of the non-radial Moore graphs constructed in the degree diameter problem, in addition to radial Moore graphs. Furthermore, the new measure offers an inclusive approach to comparing the graphs constructed in the degree diameter problem and the order degree problem.

In the present study, several graphs are generated, keeping the order fixed to and minimizing the number of vertex pairs for which the shortest path length between them is greater than 2.

3. Heuristic Algorithms to Construct Graphs Closer to Moore Graphs

Heuristic algorithms are used to determine solutions closer to optimality using probabilistic approaches. In general, heuristic algorithms are applied when deterministic algorithms fail to identify exact solutions. Heuristic algorithms do not guarantee the best solution. However, they provide approximate or near-optimal solutions. Simulated annealing is a heuristic algorithm that simulates the natural cooling process of a material [33]. Unlike greedy algorithms, such as hill climbing, simulated annealing searches not only in the direction of improving the solution. This method increases the possibility of finding the most efficient solution by escaping from local optima. The authors in [34,35] have applied simulated annealing for the order degree problem, particularly for graphs with order and degree , making the graph topology symmetrical.

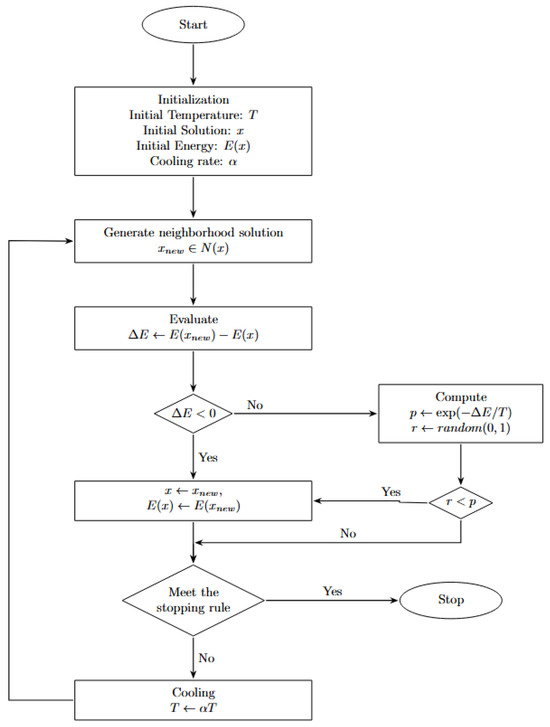

Simulated annealing starts with a random solution and a parameter called the temperature. The temperature is gradually decreased using a predefined schedule. At each iteration, a new solution is generated from a defined neighborhood. If the new solution is better than the previous one, it is accepted. Otherwise, the solution is accepted with a probability that decreases with the cooling process. Initially, this results in a high probability of accepting an inferior solution, and, gradually, the algorithm starts behaving in a greedy manner. The flow chart in Figure 2 depicts the simulated annealing process.

Figure 2.

Simulated annealing process.

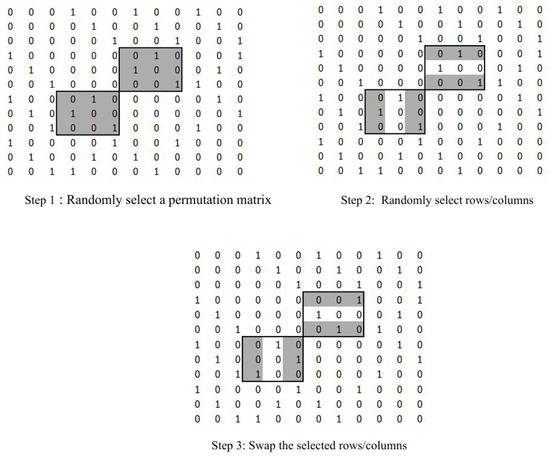

This problem can be viewed as a combinatorial optimization problem. The objective function (energy in the simulated annealing algorithm) is the number of vertex pairs that exceed the shortest path length 2. The neighborhood operator is selected, preserving the symmetry of the adjacency matrix. The neighborhood operator follows three steps. The neighborhood operator is somewhat similar to the operator applied in [36] to solve Sudoku puzzles.

- Step 1:

- Randomly select a permutation matrix and the corresponding diagonal reflection matrix inside the matrix P.

- Step 2:

- Randomly select two rows of and the corresponding two columns of the submatrix .

- Step 3:

- Swap the two selected rows (and columns).

The neighborhood operation ensures that the degree of the graph does not change. Figure 3 describes the three-step neighborhood operation. It is observed that the new adjacency matrix is generated with the new matrix P and then the new E value is calculated. The new E and the new adjacency matrix A are accepted if the new E value is less than the existing one. Otherwise, it is accepted with the probability , where T is the temperature and is the difference between the new energy and old energy.

Figure 3.

Three steps of the neighborhood operation.

For a given degree d of the graph, the algorithm is initialized by setting the initial temperature to . The simulated annealing algorithm is executed times, setting all permutation submatrices of the matrix P in the adjacency matrix to the identity matrix. The cooling rate is . After the initial run, the solution is refined with a cyclic reheating process. During each reheating phase, the algorithm runs for 600 iterations with the initial temperature 1000 and cooling rate . The reheating process is carried out ten times recursively. A summary of the obtained results is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results generated by the proposed algorithm.

In addition to simulated annealing, algorithms such as stochastic tunneling [37] and the noising method [38] have been applied to find a solution with the same neighborhood operation for degree 7, yielding ASPL values of and , respectively.

4. Fitness Landscape Analysis

Fitness landscape analysis can be applied to understand the difficulty levels and structural properties of the solution spaces of combinatorial optimization problems [39]. The concept of fitness landscape analysis was proposed by Sewall Wright to study the influence of genetic variations on the evolutionary success of organisms in theoretical biology [40]. Subsequently, it was adapted to analyze the difficulty levels, structural properties, and success of algorithms in various optimization problems. The landscape of an optimization problem is defined in terms of three components, namely the solution space, fitness function, and neighborhood structure. The solution space is the set of all possible solutions under consideration, while the neighborhood structure determines the connections between the solutions. A distance measure, such as the Hamming distance [39], quantifies the difference between two solutions in the solution space. A fitness function can be described as a mapping from the solution space to real numbers, which describes the quality of the solution [41].

The landscape related to our problem can be defined as , where X is the set of matrices under consideration, , where is the energy function of the matrix x. The distance measure is defined as the number of swaps required to transform matrix A to B. It is evident that the distance satisfies the following conditions:

Fitness landscape analysis techniques have been applied to study the nature of various classical combinatorial optimization problems [42,43]. Several measures have been introduced to examine the properties of the fitness landscape. For instance, autocorrelation and the fitness distance correlation (FDC) provide insight into the ruggedness of the landscape and the difficulty level of the problem [44].

Autocorrelation: Autocorrelation measures the similarity between neighboring solutions. A higher correlation value is an indication of a smooth landscape, while a rugged landscape shows a lower correlation [41,45]. A rugged landscape may result in trapping the local search algorithm in local optima.

where

- = autocorrelation at lag l;

- T = total number of solutions;

- l = lag ();

- = fitness value of the tth solution;

- = mean of the fitness values;

- = variance of the fitness values f.

The correlation length of the landscape is defined as follows:

We calculate the autocorrelation values and correlation lengths of the fitness landscapes for degrees 4 to 16. The correlation lengths for degrees 4 to 16 are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Correlation lengths for to .

Table 3.

Correlation lengths for to .

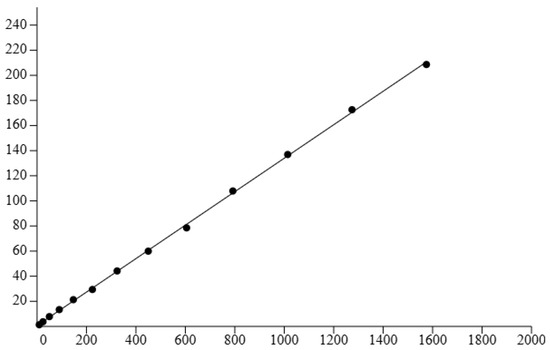

The total number of rows of the permutation matrices that are crucial for the final solution for degree d is given by . The graph in Figure 4 presents the relationship between and the correlation length for the corresponding degree. It appears to be an approximate linear relationship.

Figure 4.

: The total number of rows of the permutation matrices that have a direct impact on the final solution for degree d vs. the correlation length for degree d.

Thus, or the correlation length for degree d can be approximated as . This represents a significant sign of the predictability of the landscape structure of the problem. This observation may provide insight for the design of a unified algorithm to solve the optimization problem and for the scale-free characterization of the landscape structure.

Fitness Distance Correlation (FDC): The fitness distance correlation evaluates the correlation between the fitness values and their distance from the global optimum. The fitness distance correlation (FDC) can be expressed as the Pearson correlation coefficient between the fitness values and their distances to the global optimum. Therefore, it always lies between and 1. In a minimization problem, a positive value of FDC indicates a smooth landscape, while a negative value indicates a misleading landscape, while the opposite is true for a maximization problem [44].

where

- f: fitness value;

- d: distances to the global optimum;

- : covariance between fitness and distance;

- , : standard deviations of fitness and distance, respectively.

We compute the FDC for degree 7 as the global optimum, currently known only for degree 7, yielding . This result suggests that the problem contains a highly rugged landscape as the FDC is closer to zero. Since the fitness landscapes for other degrees exhibit similar characteristics, the result is expected to be consistent across the fitness landscapes of the other degrees.

Modality is another measure that is used to analyze the number of local optima in the landscape. Since it is possible to form multiple adjacency matrices for isomorphic graphs, it is evident that modality refers to a multi-modal landscape [46]. The selection of the most suitable algorithm complying with a specific optimization problem is challenging, since it requires studying various aspects of the problem [47]. The current results of this problem obtained from simulated annealing represent only a marginal enhancement over the results given by the greedy algorithm (the results given by the greedy algorithm are not provided here, as presenting all the values in detail is not essential for this discussion). The underlying cause of this slight improvement is the rugged nature of the fitness landscape. However, a largely complete picture of the fitness landscape can be obtained for cases with small degrees. The experimental results for small degrees suggest that global optimum solutions are extremely rare in the solution space. Furthermore, the scarcity of high-quality solutions grows as the degree increases, making the problem more challenging. Thus, expanding the area of exploration or identifying a more problem-specific algorithm is vital in acquiring better outcomes.

5. A Latin Square-Based Algorithm

In this section, the algorithm is developed further in a problem-specific manner by amplifying the impact of the neighborhood operation. The major task of the problem is to identify the most suitable arrangement of the permutation matrices inside the adjacency matrix. As is known already, the optimum graph for degree 7 is produced by arranging involution permutation matrices in a specific order [2]. Motivated by the above result, we examine the results for other degrees by arranging the involution matrices in a predefined pattern. Evidently, this generates a substantial improvement in the quality of the results. The algorithm is developed by defining a mapping between the permutation blocks inside the submatrix P and a new square matrix .

Definition 3.

Let P be the block matrix described in Equation (3). Then, the corresponding square matrix is defined in terms of blocks inside P as follows.

- Let be the matrix in the ith row of blocks and jth column of blocks inside the matrix P. Then,

- if is a zero matrix;

- if is an identity matrix;

- if is a permutation matrix where 1 in the first row is in the kth column.

Observe that all the diagonal entries of are zero, and the non-diagonal entries of the first row and column are 1. All other entries are defined according to the corresponding permutation matrices inside P. The key structure of interest is the matrix that remains after deleting the first row and column of the matrix . We refer to this matrix as henceforth. The matrix formed by the Hoffman–Singleton graph is a Latin square with diagonal entries that are zero [48]. The initial step of our algorithm is creating the matrix and hence . The corresponding matrix P is formed by arranging the involutions following the relationship described in Section 2. Then, the simulated annealing method is applied, following a new neighborhood operation. The new neighborhood operator follows two steps. In the first step, it randomly picks a non-diagonal entry from the matrix . Then, the corresponding permutation matrix in the matrix P is replaced by a new involution matrix accordingly.

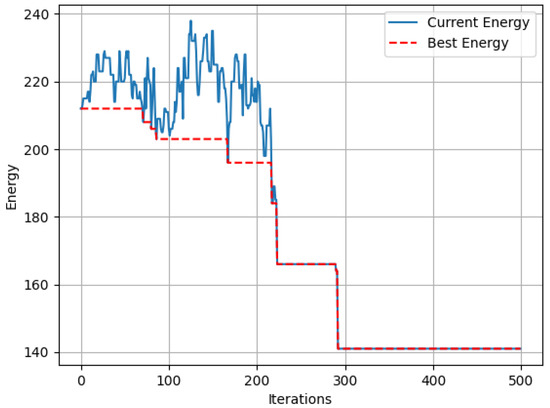

The algorithm begins with constructing the matrices and . Our focus is to construct as a Latin square since the corresponding matrix of the Hoffman–Singleton graph also forms the structure of a Latin square. The matrix must be a symmetric matrix where the entries of the main diagonal are zero. However, constructing a matrix adhering to the above conditions is only possible when the degree of the graph is odd (i.e., the order of the matrix is even) [48]. Therefore, for even degrees, we focus on constructing to be structurally closer to a Latin square. The obtained results are fine-tuned by swapping the rows as described in Section 3. Figure 5 presents the change in the energy function of the graph with degree 7 over the first 500 iterations of the new algorithm.

Figure 5.

Energy fluctuations in Latin square-based algorithm over first 500 iterations for the graph with degree 7.

The final results obtained with this new algorithm are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Graph statistics including ASPL, MDI, and excess vertex pairs for various orders and degrees.

The MDI values of some of the selected graphs from the table of the degree diameter problem for general graphs are presented in Table 5 [9]. By comparing the MDI values of the graphs presented in Table 4 with those in Table 5, it can be observed that the graphs can be moved closer to optimality by releasing a few vertex pairs from the diameter constraint. For instance, the graphs of degree and 16 in Table 4 are closer to Moore graphs than those in Table 5. In general, since the graphs represent the pairwise relationships between entities, assessing their closeness to optimality based on the number of vertex pairs, rather than merely the number of vertices, may be beneficial in assessing the efficiency of real-world networks.

Table 5.

MDI values of the existing solution graphs of the degree diameter problem.

6. Conclusions

The present study developed a method to search for a graph with the minimum average shortest path length when the order is equal to the Moore bound. The required task was tested with two heuristic algorithms based on simulated annealing, a well-established heuristic method. Although the first algorithm produces the best solutions for small degrees, the quality of the solutions is reduced for higher degrees due to the rugged nature of the solution space. The second algorithm is more problem-specific with a comparatively large neighborhood operator. This was applied to solve the order degree problem for , , , , , , and . Moreover, the constructed graphs were compared with the existing best graphs in the degree diameter problem, focusing on vertex pairs instead of the number of vertices of the graph. A new and simple index was used for this comparison. It was highlighted that, although Moore graphs do not exist for some degrees and diameters, it might be possible to construct graphs structurally closer to a Moore graph by releasing a few vertices from the diameter constraint of the degree diameter problem. Although this paper focuses only on the Moore bound of graphs with diameter 2, a similar method can be applied to find solutions for higher diameters with slight changes in the objective functions.

The quality of the solutions produced in the degree diameter problem is measured by focusing on the number of vertices of the graph, and, for the order degree problem, the focus is on the diameter or average shortest path length. However, since a graph is used to represent pairwise relationships, we introduce a new, simple index to measure the closeness to optimality of a graph relative to the Moore bound, focusing on the number of vertex pairs. This new index provides a pathway to compare the solutions obtained in both the degree diameter problem and order degree problem using a common criterion. In the future, this suggested method can be applied to build graphs closer to the 57-regular Moore graph in different approaches. Further development of the proposed method may possess practical value in network design, and it may provide theoretical insights for the study of the existence of the missing Moore graphs, in addition to traditional approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.C.W.; methodology, H.M.C.W., J.L., K.P. and C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.C.W., J.L., K.P. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, C.W., J.L., K.P. and H.M.C.W.; supervision, J.L. and K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The Python implementation to test our proposed algorithms (Python version 3.10.11, 64-bit, Windows) is available at https://github.com/chinthakakln/ODPofMoorebound.git (accessed on 21 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miller, M.; Širáň, J. Moore graphs and beyond: A survey of the degree/diameter problem. Electron. J. Comb. 2013, 20, 1–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Singleton, R.R. On Moore Graphs with Diameters 2 and 3. Ibm J. Res. Dev. 1960, 4, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducey, J.E. On the critical group of the missing Moore graph. Discret. Math. 2017, 340, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, J.; Gimbert, J. On the existence of graphs of diameter two and defect two. Discret. Math. 2009, 309, 3166–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez, J.; Miller, M. On the existence of radial Moore graphs for every radius and every degree. Eur. J. Comb. 2015, 47, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capdevila, C.; Conde, J.; Exoo, G.; Gimbert, J.; López, N. Ranking Measures for Radially Moore Graphs. Networks 2010, 56, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exoo, G.; Gimbert, J.; López, N.; Gómez, J. Radial Moore graphs of radius three. Discret. Appl. Math. 2012, 160, 1507–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pérez-Rosés, H. Algebraic and Computer-Based Methods in the Undirected Degree/Diameter Problem—A Brief Survey. Electron. J. Graph Theory Appl. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Loz, E.; Pérez-Rosés, H.; Pineda-Villavicencio, G. Combinatorics Wiki. 2010. Available online: http://combinatoricswiki.org (accessed on 27 February 2025).[Green Version]

- López, N.; Pérez-Rosés, H. Degree/diameter Problem for Mixed Graphs. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 74, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijerathne, H.M.C.; Lanel, G.H.J.; Perera, K.K.K.R.; Wanigasekara, C. Maximum Degree Diameter Bounded Subgraph Problem for Square-Octagonal Lattice. In Proceedings of the 2025 Global Conference in Emerging Technology (GINOTECH), Pune, India, 9–11 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, A.; Pérez-Rosés, H.; Pineda-Villavicencio, G.; Watters, P. The Maximum Degree & Diameter-Bounded Subgraph and its Applications. J. Math. Model. Algorithms 2012, 11, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijerathne, H.; Lanel, G.; Perera, K. Review on Maximum Degree Diameter Bounded Subgraph Problem. In Proceedings of the SLIIT International Conference on Advancements in Sciences and Humanities, Malabe, Sri Lanka, 25 September 2021; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Informatics. Graph Golf—Benchmark Problems for Network Topologies, 2024. Available online: https://research.nii.ac.jp/graphgolf/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Kitasuka, T.; Iida, M. A heuristic method of generating diameter 3 graphs for order/degree problem (invited paper). In Proceedings of the 2016 Tenth IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Networks-on-Chip (NOCS), Nara, Japan, 31 August–2 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampels, M. Vertex-symmetric generalized Moore graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2004, 138, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Satotani, Y.; Takahashi, N. Depth-First Search Algorithms for Finding a Generalized Moore Graph. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2018—2018 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 0832–0837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, H.; Hasegawa, R. Solving order/degree problems by using EDA-GK. In Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Berlin, Germany, 15–19 July 2017; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, R.; Migita, T.; Takahashi, N. A Genetic Algorithm for Finding Regular Graphs with Minimum Average Shortest Path Length. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Canberra, Australia, 1–4 December 2020; pp. 2431–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.; Kumar, V. A review on genetic algorithm: Past, present, and future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaens, F.; Gionis, A. Diameter Minimization by Shortcutting with Degree Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Orlando, FL, USA, 28 November–1 December 2022; pp. 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesnik, J. The complexity of designing a network with minimum diameter. Networks 2006, 11, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, R.A.; Johnson, C.R. Matrix Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ceresuela, J.M.; López, N. Bounds in radial Moore graphs of diameter 3. Discret. Math. 2025, 348, 114533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knor, M. Small radial Moore graphs of radius 3. Australas. J. Comb. 2012, 54, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Xiao, B.; Tao, D.; Li, X. A survey of graph edit distance. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2010, 13, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, I.; Stanić, Z. Spectral distances of graphs. Linear Algebra Its Appl. 2012, 436, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Jia, W.; Belardo, F.; Liu, M. Maximal Lanzhou index of trees and unicyclic graphs with prescribed diameter. Appl. Math. Comput. 2025, 488, 129116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shiu, W.C. The harmonic index of a graph. Rocky Mt. J. Math. 2014, 44, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eliasi, M.; Raeisi, G.; Taeri, B. Wiener index of some graph operations. Discret. Appl. Math. 2012, 160, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knor, M.; Kranjc, J.; Škrekovski, R.; Tepeh, A. On the minimum value of sum-Balaban index. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 303, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Ma, Z.W.; Zhang, X.D.; Chen, Y.H. The minimum Wiener index of unicyclic graphs with maximum degree. Appl. Math. Comput. 2024, 470, 128581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahaye, D.; Chaimatanan, S.; Mongeau, M. Simulated Annealing: From Basics to Applications. In Handbook of Metaheuristics; International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Gendreau, M., Potvin, J.Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Murai, H.; Sato, M. A Method for Order/Degree Problem Based on Graph Symmetry and Simulated Annealing with MPI/OpenMP Parallelization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on High Performance Computing in Asia-Pacific Region, Guangzhou, China, 14–16 January 2019; HPCAsia’19, pp. 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, M.; Sakai, M.; Hanada, Y.; Murai, H.; Sato, M. Graph optimization algorithm for low-latency interconnection networks. Parallel Comput. 2021, 106, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R. Metaheuristics can solve Sudoku puzzles. J. Heuristics 2007, 13, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, W.; Hamacher, K. A Stochastic Tunneling Approach for Global Minimization of Complex Potential Energy Landscapes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, I.; Hudry, O. The noising method: A new method for combinatorial optimization. Oper. Res. Lett. 1993, 14, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidys, C.; Stadler, P. Combinatorial Landscapes. Siam Rev. 2001, 44, 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. The Roles of Mutation, Inbreeding, crossbreeding and Selection in Evolution. Proc. Int. Congr. Genet. 1932, 8, 209–222. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, C.R. Fitness Landscapes and Evolutionary Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Artificial Evolution, AE 1999, Dunkerque, France, 3–5 November 1999; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Fonlupt, C., Hao, J.K., Lutton, E., Schoenauer, M., Ronald, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 1829, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najaran, M.; Prugel-Bennett, A. On the Landscape of Combinatorial Optimization Problems. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2014, 18, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, P.; Freisleben, B. Fitness landscape analysis and memetic algorithms for the quadratic assignment problem. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2000, 4, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, K.M.; Engelbrecht, A.P. Fitness Landscape Analysis for Metaheuristic Performance Prediction. In Recent Advances in the Theory and Application of Fitness Landscapes; Emergence, Complexity and Computation; Richter, H., Engelbrecht, A.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkuryeva, G.; Bolshakov, V. Benchmark Fitness Landscape Analysis. Int. J. Simulation Syst. Sci. Technol. 2011, 12, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.; Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithm Difficulty and the Modality of Fitness Landscapes. In Foundations of Genetic Algorithms; Whitley, L.D., Vose, M.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, K.M.; Engelbrecht, A.P. Ruggedness, funnels and gradients in fitness landscapes and the effect on PSO performance. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Cancun, Mexico, 20–23 June 2013; pp. 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keedwell, A.D.; Dénes, J. Chapter 2—Special types of latin square. In Latin Squares and their Applications, 2nd ed.; Keedwell, A.D., Dénes, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 37–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).