Abstract

In this paper, the ranked set sampling method (RSS) is considered for estimating the inverse power Lindley distribution (IPLD) parameters and compared with the commonly simple random sampling. Different estimation methods are investigated including the commonly maximum likelihood, minimum distance estimation methods (Anderson Darling (AD), right tail Anderson Darling, left tail Anderson Darling, AD left tail second order, Cramér-von Mises), methods of maximum and minimum spacing distance (maximum product spacing distance, minimum spacing distance), methods of ordinary and weighted least squares, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov method. A simulation study is conducted to compare these methods using RSS and SRS based on the same number of measured units in terms of mean squared error, bias, efficiency, and mean relative estimation error. A failure data set is fitted to the IPLD and the proposed estimation methods are applied to the data.

Keywords:

ranked set sampling; inverse power Lindley distribution; maximum likelihood estimation; minimum distance estimation; Cramér-von Mises estimator; ordinary and weighted least squares MSC:

60E05; 62E10; 62G30

1. Introduction

Ranked set sampling (RSS) is an advanced statistical sampling technique introduced by [1] that improves parameter estimation accuracy compared to simple random sampling (SRS). It is particularly beneficial in situations where precise measurements are costly, time-consuming, or destructive, while ranking the units is relatively easy and inexpensive. The RSS is widely applied in various fields, including agriculture, environmental science, reliability analysis, and medical research. Over time, it has been adapted into different variations, such as modified RSS, extreme RSS, median RSS, and multistage RSS to suit specific research needs. Its efficiency and flexibility make RSS an essential tool in modern statistical inference and data collection methodologies.

Let X be a random variable representing a characteristic of interest with mean and variance . Let denote the j-th observation in the i-th set, where and .

The RSS process can be performed with m sets, each of size m as in the following steps:

- Chose m random sets from the population of interest as

- Rank the units in each set through an inexpensive technique, for example, visual ranking or using an auxiliary variable aswhere denotes the j-th smallest order unit in i-th set.

- From the i-th set, select the i-th ranked unit , by selecting from the first set, the smallest-ranked observation is measured, from the second set, the second-smallest observation is measured. This process continues, with the m-th set contributing the highest-ranked observation as

Then, the final RSS sample which can be used for actual measurement is:

Then, the final RSS sample which can be used for actual measurement is:

The probability density function (pdf) and cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the , respectively, are given by

and

The final RSS sample consists of the measured values for . The RSS-based estimator for the population mean is given by which is generally more efficient than the simple SRS estimator. It can be shown that , that is the RSS estimator is unbiased for [2]. The variance of the RSS mean estimator is generally lower than that of the SRS estimator () based on the same size of measured units with variance:

In general, the RSS enhances estimation accuracy by incorporating ranking information, particularly when ranking is highly correlated with actual measurements. The efficiency gain depends on the strength of ranking and the underlying population distribution. In many practical applications, RSS achieves the same estimation precision as SRS but with a smaller sample size, making it a valuable method in scenarios where exact measurements are costly or time-consuming.

Recently, numerous studies have explored RSS by introducing modifications or applying it to estimate population parameters across various fields.

Ref. [3] proposed balanced groups RSS for mean estimation. Ref. [4] suggested a multistage RSS for estimating the population mean, which increases efficiency for a fixed sample size. A modified robust extreme RSS is proposed by [5] for estimating the population mean. Ref. [6] offered a mixed RSS as a variation of the RSS for parameters estimation. Ref. [7] studied the maximum likelihood estimators using RSS of the log–logistic distribution parameters. Ref. [8] investigated the problem of estimating log–logistic parameters using the moving extremes RSS. Ref. [9] considered the RSS in estimating the inverted Kumaraswamy distribution parameters. Ref. [10] investigated the population mean under stratified RSS. Ref. [11] studied the RSS in estimating the Xgamma distribution parameters with an application to real data. Ref. [12] introduced a review of RSS and its modified methods in developing control charts. Ref. [13] proposed the dual RSS method. Ref. [14] investigated the RSS in various estimation methods for the power logarithmic distribution. Ref. [15] suggested new modification to the median quartile double RSS for estimating the population mean. Ref. [16] utilized the neutrosophic median RSS for mean estimation with an application to demographic data. Ref. [17] considered mean estimation using RSS in the presence of measurement errors. Ref. [18] recommended the RSS in evaluating the performance of control charts. Ref. [19] used the RSS in estimating the parameters of the unit Lindley distribution. Ref. [20] used the RSS for estimating the stress-strength reliability for the Beta-Lomax distribution. Ref. [21] investigated the RSS in estimating the parameter of the exponential-Poisson distribution. Ref. [22] considered the MRSS for estimating the log–logistic distribution using median RSS based on the maximum likelihood estimation.

The Lindley distribution is proposed by [23] by mixing the exponential and gamma distributions with respective pdfs:

to get the pdf of Lindley distribution as

Due to the importance of this distribution, many modifications and applications for this distribution are investigated in the literature as the inverse Lindley distribution by [24], the power Lindley distribution by [25], which is a mixture of Weibull distribution with shape parameter and scale parameter and the generalized gamma distribution with scale parameter , and shape parameters 2 and . Ref. [26] considered Bayesian and non-Bayesian estimations of truncated inverse power Lindley distribution under progressively type-II censored data and studied it by Bayesian and non-Bayesian estimations. Ref. [27] suggested heavy-tailed inverse power Lindley Type-I model.

The pdf of the inverse power Lindley distribution [28] is given by

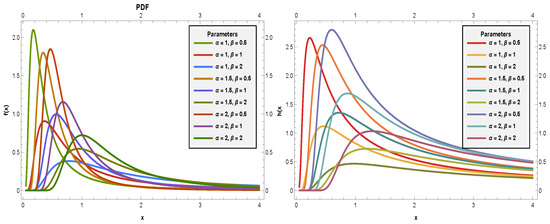

where is the location parameter and the scale parameter. The corresponding cumulative distribution function (CDF) and hazard rate function (HRF) for the PILD are respectively in Figure 1, given by

Figure 1.

The IPLD pdf and HRF plots.

The main objectives of the study are

- To estimate the parameters of the inverse power Lindley distribution using RSS technique, and to compare the performance of RSS with the SRS method in parameter estimation.

- To evaluate and compare multiple estimation techniques, including: maximum Likelihood estimation, minimum distance estimation methods (Anderson–Darling, right-tail AD, left-tail AD, left-tail second order AD, Cramér–von Mises), maximum and minimum spacing distance methods, ordinary and weighted least squares methods, and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov method.

- To conduct a simulation study assessing each estimation method under RSS and SRS using performance criteria such as mean squared error (MSE), bias, efficiency, and mean relative estimation error (MRE).

- To apply the proposed estimation approaches to a real failure data set to demonstrate the practical utility of RSS in estimating IPLD parameters.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, different estimation methods are introduced. A detailed numerical simulations are given in Section 3. An application of real data is presented in Section 4. In Section 5, main results for the work are presented along with some directions for further works.

2. Methods of Estimation

In this section, we investigate fifteen estimation method to estimate the parameters and of the I-PL distribution. Within this framework, we denote as the ranked observation (i.e., the order statistic) in the subset of the cycle, where s ranges from 1 to d and h ranges from 1 to v. These observations form the RSS data for T, with a total sample size of . For simplification, we represent the selected sample under the RSS design as

2.1. Maximum Likelihood Estimation

This section derives the maximum likelihood estimators (MLEs) for parameters and of the I-PL distribution using the RSS methodology. MLEs is the most widely used estimation method in statistics due to its optimal asymptotic properties (consistency, asymptotic efficiency, and asymptotic normality). Let represent the observed RSS data with sample size , where d indicates the set size and v denotes the number of cycles, all sampled from the I-PL distribution.

Based on this RSS data, the likelihood function is expressed as

where

The log-likelihood function of (2) is as follows:

where

The MLEs of , and of can be obtained by solving simultaneously the following normal equations:

and

where, and .

To solve for and , numerical methods are required since these estimators cannot be expressed in closed form. Nonlinear optimization algorithms such as the Newton–Raphson iterative method would be appropriate for computing these values.

2.2. Minimum Distance Estimation Methods

Estimation methods that rely on minimizing well-established goodness-of-fit statistics are often effective and yield reliable results in various scenarios. In this study, five widely used techniques are considered, each aiming to minimize the discrepancy between the theoretical and empirical cumulative distribution functions.

2.2.1. Anderson–Darling

The Anderson–Darling method is particularly appropriate for capturing tail behavior accurately. Consider an ordered sample obtained from a RSS of size , where d represents the set size and v is the cycle number, drawn from the I-PL distribution. The Anderson–Darling estimates (ADEs) for and , denoted as and , are obtained by minimizing the following function:

where represents the survival function. Instead of directly using (3), the values and can be numerically determined by solving the following nonlinear equations:

and

where

and

and and have similar expressions with the ordered sample .

2.2.2. Right-Tail Anderson–Darling

The Right-Tail Anderson–Darling specifically emphasizes the right tail of the distribution. Consider an ordered sample obtained from an RSS of size , where d represents the set size and v is the cycle number, drawn from the I-PL distribution. The right-tail Anderson–Darling estimates (RTADEs) for and , denoted as and , are obtained by minimizing the following function:

2.2.3. Left-Tail Anderson–Darling

The Left-Tail Anderson–Darling focuses on the left tail of the distribution. It is useful when early failures or small values are of particular concern, such as in quality control applications. Let be an ordered sample obtained from the I-PL distribution and forming an RSS of size , where s represents the set size and w is the cycle number. The Left-Tail Anderson–Darling estimates (LTADEs) for and , denoted as and , are determined by minimizing the following function:

2.2.4. AD Left-Tail Second Order

The Left-Tail Anderson–Darling second-order provides enhanced emphasis on the extreme left-tail with second-order weighting and offers even more sensitivity to the behavior of the distribution near zero, which can be critical for certain applications. Let be an ordered sample constructed using the I-PL distribution, resulting in an RSS of size with set size s and cycle number w. The Left-Tail Anderson–Darling second-order estimate (ADSOE) for and , denoted as and , is obtained by minimizing the function below:

2.2.5. Cramér–von Mises Estimators

The Cramér–von Mises provides balanced estimation across the entire support of the distribution without emphasizing any particular region, making it a robust general-purpose estimator. Let be an ordered sample created using the I-PL distribution, which yields an RSS of size , where d is the set size and v is the cycle number. The Cramér–von Mises estimates (CVMEs) for and , denoted as and , can be obtained by minimizing the following function:

Instead of using (9), one may solve the following nonlinear equations to obtain and :

and

where, amd are given in (4) and (5).

2.3. Method of Maximum and Minimum Spacing Distance

The MPS approach was first presented by Cheng and Amin [29,30]. This approach depends on maximizing the geometric mean of the data’s spacings. For the most part, the MPS method is particularly effective for small samples and distributions with complex functional forms. MPS is less sensitive to outliers and model misspecification than MLE.

2.3.1. Maximum Product Spacing Distance

Suppose that form an ordered sample creating an RSS of size , gathered from the I-PL distribution. The uniform spacing is then determined by

Note that and

The following function is maximized with respect to and to obtain the MPS estimates (MPSEs) and :

2.3.2. Minimum Spacing Distance

Minimum spacing distance estimators provide a distribution-free approach that does not require complete specification of the likelihood function and is computationally simpler in some cases. Consider as an ordered sample obtained from the I-PL distribution distribution, with cycle number w and set size s, forming an RSS of size . We can derive various parameter estimates by minimizing specific objective functions.

- Minimum spacing absolute distanceBy minimizing the following function, we obtain the minimum spacing absolute distance Estimates (MSADEs) of and of :

- Minimum spacing absolute-log distanceBy minimizing the following function, we obtain and the minimum spacing absolute-log distance Estimates (MSALDEs) of and of ,

- Minimum spacing square distanceNext, by minimizing the following function, we determine the minimum spacing square distance Estimates (MSSDEs) of and of :

- Minimum spacing square log-distanceBy minimizing the following function, we determine the minimum spacing square log-distance Estimates (MSSLDEs) of and of ,

- Minimum spacing Linex distanceFinally, we can obtain the minimum spacing Linex distance Estimates (MSLDE) of and of by minimizing the following function:

2.4. Methods of Ordinary and Weighted Least Squares

The OLS estimates (OLSE) and WLS estimates (WLSE) were introduced by [31] to estimate the parameters of the beta distribution. They are simple to implement, computationally efficient, and provides reasonable estimates without requiring iterative likelihood maximization. Consider an ordered sample obtained from the I-PL distribution, with cycle number v and set size d,forming an RSS of size . By minimizing the following function, the OLSEs of and of are found to be, respectively:

The following non-linear equations can also be solved to produce these estimators:

and

2.5. Kolmogorov Method

Kolmogorov method focuses on worst-case fit rather than average fit, ensuring that the estimated distribution does not deviate excessively from the data at any point. Consider an ordered sample obtained from the I-PL distribution, with cycle number v and set size d, forming an RSS of size . In order to obtain the Kolmogorov estimates (KEs) and the following function is minimized with regard to and

3. Numerical Simulation

This section evaluates different estimation methods for the IPLD discussed in Section 2. We compare both the SRS and RSS approaches under various configurations. All computations were performed using R software (R Core Team, 2024). All parameter estimates were obtained using the optim() function from the stats package with the Nelder-Mead method (method = "Nelder-Mead") for optimization. To ensure consistency and assess the robustness of all estimation methods, initial values were randomly selected from a uniform distribution around the true parameter values. Specifically, for true parameters , initial values were drawn from and , representing perturbations within of the true values. This approach allowed us to evaluate the stability and convergence properties of each estimation method across different starting points. All methods consistently converged to the same estimates regardless of the specific initial values, demonstrating the global convergence of the optimization algorithms. The convergence was verified in all cases with a tolerance level of .

To evaluate the accuracy of the estimation between methods and sampling designs, we calculate four statistical metrics:

where M = 10,000 represents the number of simulations and are the parameters of interest.

The efficiency of RSS relative to SRS is calculated as

where , , and represent the bias, mean squared error, and mean relative error under SRS, respectively, and , , and represent the corresponding metrics under RSS. Values of indicate that RSS outperforms SRS.

Our simulation examines two parameter set values: , which represents a case with pronounced right-skewness and heavy tails, and , which corresponds to a more moderate skewness and dispersion, reflecting data with lighter tails and wider spread. For RSS, we use set sizes of with cycle numbers of 4 and 9. For SRS, the sample size is calculated as the set size multiplied by the number of cycles to ensure comparable sizes between RSS and SRS approaches. The results are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 for both sampling methods in all configurations.

Table 1.

AE, Bias, MSE, MRE, and relative efficiency for MLE, OLSE, WLSE, MPSE and CVME for both RSS and SRS when .

Table 2.

AE, Bias, MSE, MRE, and relative efficiency for MSADE, MSALDE, MSSDE, MSSLDE, and MSLDE for both RSS and SRS when .

Table 3.

AE, Bias, MSE, MRE, and relative efficiency for KE, ADE, RTADE, LTADE, and ASLSOE for both RSS and SRS when .

Table 4.

AE, Bias, MSE, MRE, and relative efficiency for MLE, OLSE, WLSE, MPSE, and CVME for both RSS and SRS when .

Table 5.

AE, Bias, MSE, MRE, and relative efficiency for MSADE, MSALDE, MSSDE, MSSLDE, and MSLDE for both RSS and SRS when .

Table 6.

AE, Bias, MSE, MRE, and relative efficiency for KE, ADE, RTADE, LTADE, and ASLSOE for both RSS and SRS when .

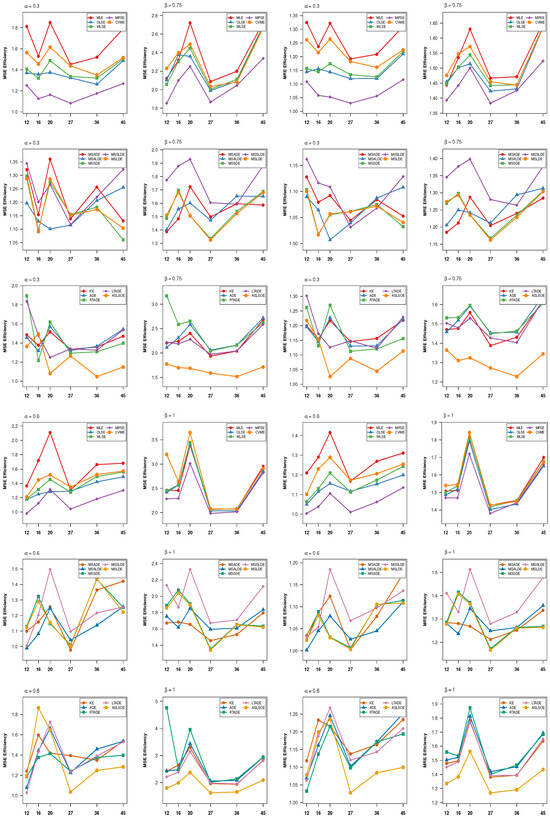

Also, in Figure 2, we plotted the efficiency values based on the RSS relative to SRS for the MSE and MRE using all estimation methods with different sample sizes for easy comparison.

Figure 2.

The efficiency values of the RSS based on MSE and MRE for all estimation methods.

Based on Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, the following observations can be concluded:

- A.

- Case 1:

For Parameter :

- Regarding MSE efficiency for , MLE and CVME in Table 1 show high performance, with Eff values ranging from 1.1088 to 1.8115. For instance, at under MLE, the MSE for decreases from (SRS) to (RSS), achieving an efficiency of 1.812. In Table 2, MSSLDE demonstrates good MSE reduction, with Eff values up to 1.5. Similarly, RTADE and LTADE in Table 3 are particularly effective in reducing MSE, showing Eff values between 1.3 and 1.8.

For Parameter :

- A substantial reduction in MSE for is a consistent observation across all methods. Specifically, MLE and CVME in Table 1 frequently achieve Eff values above 2.0, occasionally surpassing 3.0. For instance, at , the MLE for shows an MSE improvement from (SRS) to (RSS), resulting in an efficiency of 2.154. In Table 2, MSSLDE distinguishes itself with high MSE efficiency, typically ranging from 1.8 to 2.1. Most notably, RTADE in Table 3 exhibits exceptionally high MSE efficiency, with an Eff value reaching up to 3.138 for , underscoring a very strong advantage of RSS for this particular estimator.

- B.

- Case 2:

For Parameter :

- The MLE results in Table 4 consistently exhibit effective bias reduction. In contrast, the MSSLDE estimator in Table 5 shows a moderate improvement, while the KE and ADLSOE estimators in Table 6 achieve slightly greater reductions in bias, highlighting their relatively superior efficiency under the RSS framework.

- Furthermore, both MLE and CVME in Table 4 maintain robust MSE efficiency, with Eff values ranging from 1.3 to 1.7. Within Table 5, MSSDE and MSLDE typically achieve good MSE reduction, showing Eff values between 1.1 and 1.4, and MSSLDE’s efficiency also improves with increasing m (up to 1.556). For the estimators in Table 6, ADLSOE, KE, and RTADE demonstrate commendable MSE efficiency, ranging from 1.2 to 1.8.

For Parameter :

- A pronounced reduction in MSE is observed for under RSS. In Table 4, both MLE and CVME exhibit substantial improvement, with CVME reaching a notably high value of 3.174 for . MSSLDE in Table 5 also shows consistently strong performance, maintaining MSE reductions within the range of 1.7 to 2.3. The most remarkable gains, however, are achieved by RTADE in Table 6, which demonstrates exceptional variance reduction for , with values extending up to 4.750 for .

The RSS consistently shows superior performance over SRS in estimation. This superiority is clearly demonstrated by efficiency values consistently greater than 1 for MSE and MRE, which strongly validates the use of RSS to enhance the precision and accuracy of estimation.

4. Real Data Analysis

In this section, we demonstrate the utility of our proposed estimation approaches by analyzing a carefully selected dataset. Our goal is to showcase the practical applications and effectiveness of these estimation techniques through a comprehensive examination of the data set. By presenting a real data that present failure time of 40 items discussed by [32]. The data is reported on Table 7.

Table 7.

Failure dataset.

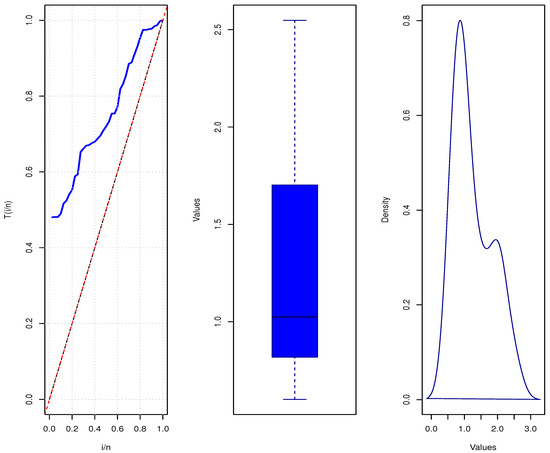

Table 8 and Figure 3 represent the descriptive statistical analysis and some graphical representations, including the TTT, box, and density plots, to illustrate the dataset used.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistical analysis of the selected dataset.

Figure 3.

TTT, box, and density plots for the proposed dataset.

The descriptive statistics in Table 8 and the graphical representation in Figure 3 demonstrate a right-skewed distribution, characterized by a skewness of 0.71. The mean (1.25) being higher than the median (1.02) indicates the presence of some notably large values that pull the average upward. The data exhibits moderate dispersion, with a standard deviation of 0.57 and a coefficient of variation of 45.66%. The slightly platykurtic kurtosis of 2.25 suggests a distribution with fewer extreme values compared to a normal distribution.

To evaluate the adequacy and superiority of the proposed estimation methods under the I-PLD, we compare its performance with three related lifetime distributions: the Lindley distribution [23], the Inverse Lindley distribution [33], and the Inverse Weibull distribution [34]. Each of these models provides a different degree of flexibility in modeling positively skewed data, which allows us to assess the robustness and accuracy of the I-PLD fit. These models were fitted to the same real dataset, and their performances were evaluated using several goodness-of-fit criteria, including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Corrected AIC (CAIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Hannan–Quinn Information Criterion (HQIC), and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test.

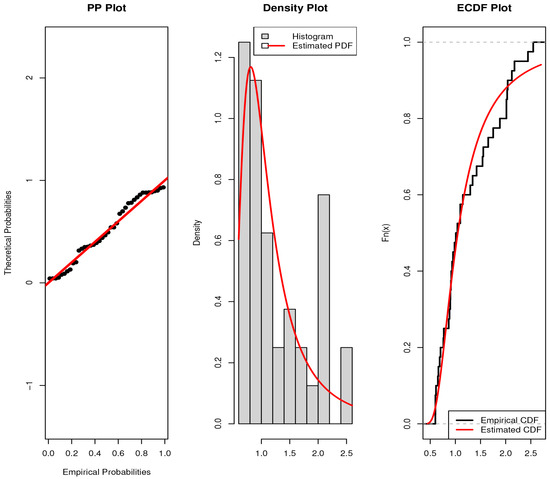

The results in Table 9 show that the IPLD provides the best fit to the data, as indicated by their lower AIC, CAIC, BIC, and HQIC values, and by their non-significant K–S test results (high p-values). Between these two, the IPLD demonstrates slightly better performance and stability, confirming its superiority and flexibility in modeling positively skewed lifetime data compared to the standard Lindley-type distributions. The graphical representation in Figure 4 provides visual confirmation of these statistical findings.

Table 9.

Comparison of fitted models for the real dataset.

Figure 4.

P-P, density and emperical CDF plots lots for the dataset.

To comprehensively examine the superiority of ranked set sampling over SRS across different estimation methods, an SRS sample of size 12 was chosen for comparability, while an RSS scheme was designed with a set size of 3 and four cycles to maintain the same total sample size. Assuming a perfect sampling design, an extensive evaluation was carried out using several goodness-of-fit statistics to assess the performance and reliability of each sampling approach. Specifically, we employed the Anderson–Darling test , the Cramér-von Mises test , and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test . These statistical measures were systematically applied to assess model fit and provide comparative insights into the effectiveness of RSS in capturing the underlying data distribution relative to SRS. A detailed comparison of the goodness-of-fit values for both sampling designs is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Estimates and test statistics for each method under the two sampling schemes (SRS and RSS).

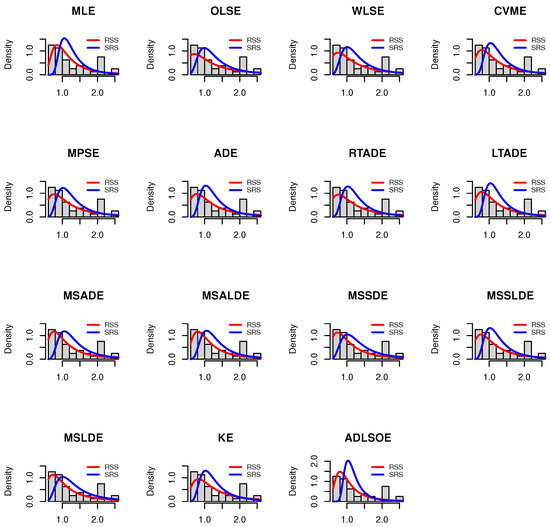

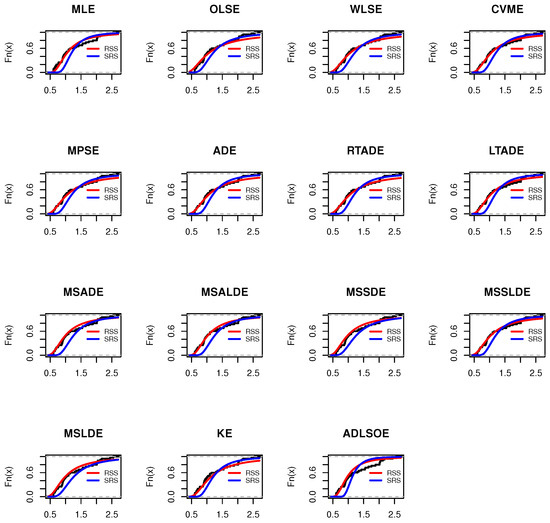

Table 10 revealed a consistent superiority of RSS over SRS across multiple estimation techniques. The RSS methodology demonstrated notably improved model fit, characterized by reduced , , and test values, coupled with elevated p-values. These empirical findings substantiate the theoretical advantages of RSS design. The graphical representations in Figure 5 and Figure 6 provide additional visual corroboration of these findings, reinforcing the robust performance of the RSS approach in statistical modeling.

Figure 5.

Plots of the estimated PDFs of the I-PL distribution for the two sampling method for and .

Figure 6.

Plots of the estimated CDFs of the I-PL distribution for the two sampling method for and .

5. Conclusions

This study provides strong evidence that ranked set sampling (RSS) outperforms simple random sampling (SRS) in estimating parameters of the inverse power Lindley distribution (IPLD). Through an extensive comparison of eleven estimation techniques, supported by large-scale simulations and empirical data, RSS consistently produced estimators with lower bias, smaller mean squared error, and improved mean relative error—all achieved without increasing the number of measurements. The results underline RSS’s intrinsic advantage in exploiting ranking information for greater estimation precision. While maximum likelihood estimation performed reliably, the most pronounced efficiency gains under RSS were seen in minimum distance estimators (based on Anderson–Darling and Cramér–von Mises criteria) and spacing-based approaches such as maximum product spacing and minimum spacing distance. Notably, MSSLDE and RTADE methods showed exceptional accuracy in estimating the scale parameter , substantially reducing variance and MSE. These advantages were further validated using real failure time data, confirming the practical significance of RSS in applied settings. Given its efficiency, simplicity, and low implementation cost, RSS emerges as a valuable and practical tool for researchers and professionals in reliability engineering, survival analysis, and quality control. Future investigations may extend this work by developing new RSS variants, testing additional distributions, or broadening empirical applications to demonstrate its versatility in statistical inference.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.B., G.A. and A.I.A.-O.; Methodology, A.I.A.-O., G.A. and S.A.B.; Software, S.A.B. and A.I.A.-O.; Validation, S.A.B., G.A. and A.I.A.-O.; Formal analysis, S.A.B.; Investigation, G.A., S.A.B. and A.I.A.-O.; Data curation, S.A.B.; Writing—original draft, G.A., S.A.B. and A.I.A.-O.; Writing—review & editing, G.A., S.A.B. and A.I.A.-O.; Visualization, S.A.B. and A.I.A.-O.; Funding acquisition, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R226), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

All the data sets used in this paper are available within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R226), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- McIntyre, G.A. A method of unbiased selective sampling, using ranked sets. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1952, 3, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Wakimoto, K. On unbiased estimates of the population mean based on the sample stratified by means of ordering. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 1968, 20, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemain, A.A.; Al-Omari, A.; Ibrahim, K. Some variations of ranked set sampling. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. Anal. 2008, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saleh, M.F.; Al-Omari, A.I. Multistage ranked set sampling. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2002, 102, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omari, A.I. Estimation of mean based on modified robust extreme ranked set sampling. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, A.; Brown, J.; Moltchanova, E.; Al-Omari, A.I. Mixed ranked set sampling design. J. Appl. Stat. 2014, 41, 2141–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, W.; Qian, W. Maximum likelihood estimators of the parameters of the log–logistic distribution. Stat. Pap. 2020, 61, 1875–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.F.; Chen, W.X.; Yang, R. Log–logistic parameters estimation using moving extremes ranked set sampling design. Appl. Math. J. Chin. Univ. 2021, 36, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, H.F.; Al-Omari, A.I.; Hassan, A.S.; Alomani, G.A. Improved estimation of the inverted Kumaraswamy distribution parameters based on ranked set sampling with an application to real data. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S.; Kumar, A.; Shahab, S.; Lone, S.A.; Akhtar, M.T. On efficient estimation of the population mean under stratified ranked set sampling. J. Math. 2022, 2022, 6196142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omari, A.I.; Benchiha, S.; Almanjahie, I.M. Efficient estimation of two-parameter Xgamma distribution parameters using ranked set sampling design. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkhani, A.; Amiri, A.; Khoo, M.B. A review of ranked set sampling and modified methods in designing control charts. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2023, 39, 1465–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taconeli, C.A. Dual-rank ranked set sampling. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2024, 94, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadat, N.; Hassan, A.S.; Elgarhy, M.; Johannssen, A.; Gemeay, A.M. Estimation methods based on ranked set sampling for the power logarithmic distribution. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, M.A.; Nisar, A.; Khan, A.; Emam, W.; Tashkandy, Y.; Khurram, H.; Al-Shbeil, I. Modified median quartile double ranked set sampling for estimation of population mean. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Singh, R.; Smarandache, F. New modification of ranked set sampling for estimating population mean: Neutrosophic median ranked set sampling with an application to demographic data. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadini, A.A.H.; Singh, R.; Raghav, Y.S.; Kumari, A. Estimation of population mean using ranked set sampling in the presence of measurement errors. Kuwait J. Sci. 2024, 51, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, W.H.; Haq, A.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Saleh, N.A. Reevaluating the performance of control charts based on ranked-set sampling. Qual. Eng. 2024, 36, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchiha, S.A.; Al-Omari, A.I.; Alomani, G. Enhanced estimation of the unit Lindley distribution parameter via ranked set sampling with real-data application. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhedary, M.Z.A.; Khamnei, H.J.; Heydari, A.A. Evaluating Stress-Strength Reliability Estimation Technique: A Study on Ranked Set Sampling for the Beta-Lomax Distribution. Contemp. Math. 2025, 6, 442–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, W.X.; Deng, C.H. Some new results on parameter estimation of the exponential-Poisson distribution in ranked set sampling. Appl. Math. J. Chin. Univ. 2025, 40, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Samuh, M.H. Efficiency comparison of maximum likelihood estimation in log–logistic distribution using median ranked set sampling. Kuwait J. Sci. 2025, 52, 100350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, D.V. Fiducial distributions and Bayes’ theorem. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1958, 20, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, U.; Agiwal, V. The inverse Lindley distribution: A stress-strength reliability model with application to head and neck cancer data. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2015, 32, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitany, M.E.; Al-Mutairi, D.K.; Balakrishnan, N.; Al-Enezi, L.J. Power Lindley distribution and associated inference. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2013, 64, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgarhy, M.; Mutairi, A.A.; Hassan, A.S.; Chesneau, C.; Abdel-Hamid, A.H. Bayesian and non-Bayesian estimations of truncated inverse power Lindley distribution under progressively type-II censored data with applications. AIP Adv. 2023, 13, 095130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.S.; Metwally, D.S.; Elgarhy, M.; Mohamed, R.E. The heavy-tailed inverse power Lindley type-I model: Reliability inference and actuarial applications. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco, K.; Mazucheli, J.; Janeiro, V. The inverse power Lindley distribution. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2017, 46, 6308–6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.C.H.; Amin, N.A.K. Maximum Product of Spacings Estimation with Application to the Lognormal Distribution; Technical Report; University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology: Cardiff, Wales, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R.C.H.; Amin, N.A.K. Estimating parameters in continuous univariate distributions with a shifted origin. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1983, 45, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, J.J.; Venkatraman, S.; Wilson, J.R. Least-squares estimation of distribution functions in Johnson’s translation system. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 1988, 29, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, D.P.; Xie, M.; Jiang, R. Weibull Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, U.; Singh, N.K. A new inverse Lindley distribution: Properties and applications. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2015, 139, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A.Z.; Kamath, M. Alternative life distributions for engineering reliability analysis: The Inverse Weibull and related distributions. Microelectron. Reliab. 1982, 22, 223–231. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).