Abstract

Urban park accessibility is often planned with fixed service radii, that is, circular walking catchments around each park defined by a maximum walking distance of about 1500 m, roughly a 15–20 min walk in this study, yet real visitation is uneven and dynamic, leaving persistent gaps between normative coverage and where people actually originate. We propose an interpretable discovery-to-parameter workflow that converts behavior evidence into localized accessibility and actionable planning guidance. Monthly Origin–Destination (OD) and heatmap samples are fused to construct visitation intensity on a 200 m grid and derive empirical park service boundaries. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) then quantifies spatial heterogeneity, and its local coefficients are embedded into the enhanced two-step floating catchment area (E2SFCA) model as location-specific supply weights and distance-decay bandwidths. Compared with network isochrones and uncalibrated E2SFCA, the MGWR–E2SFCA achieves higher Jaccard overlap and lower population-weighted error, while maintaining balanced coverage–precision across districts and day types. A -surface lens decomposes gains into corridor correction and envelope contraction, revealing where conventional radii over- or under-serve residents. We further demonstrate an event-sensitivity switch, in which temporary adjustments of demand and decay parameters can accommodate short-term inflows during events such as festivals without contaminating the planning baseline. Together, the framework offers a transparent toolset for diagnosing mismatches between normative standards and observed use, prioritizing upgrades in under-served neighborhoods, and stress-testing park systems under recurring demand shocks. For land planning, it pinpoints where barriers to access should be reduced and where targeted connectivity improvements, public realm upgrades, and park capacity interventions can most effectively improve urban park accessibility.

1. Introduction

Urban parks are essential components of sustainable and livable cities, providing critical services such as ecological regulation, recreation, psychological restoration, and social interaction [1,2]. In rapidly densifying urban cores, however, assumed and uniform service radii fail to explain emerging urban maladies: flagship parks are overcrowded while local parks remain underused; long-distance weekend trips exceed nominal walking envelopes; and “last-mile” gaps—including unsafe crossings, discontinuous sidewalks, and weak wayfinding systems—collectively suppress nearby use [3,4]. Fixed thresholds and generic distance-decay functions thus over-claim areas that do not generate actual trips while omitting corridors that effectively feed parks, thereby risking mis-targeted investments and inequitable green space provision [5,6]. A central task is therefore to delineate the actual service boundary—defined as the geographic origins that truly supply visitors—so that omissions, which signify access deficits, and commissions, referring to inflated service envelopes, can be accurately diagnosed and systematically corrected.

Traditional delineation methods, including isochrone, gravity, and two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) variants, largely retain fixed distance thresholds and generic decay functions [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Empirical evidence shows that such assumptions miss behaviorally observed long-range trips and under-represent micro-frictions near parks, producing envelopes that diverge from realized use [14,15,16,17,18]. At the same time, large-scale mobility data now permit direct observation of visitation: mobile phone signaling and OD trajectories capture dynamic origins and routing [19,20,21], while Baidu heatmaps (HT) and related urban vibrancy indices reveal fine-grained spatiotemporal activity patterns at city and urban agglomeration scales [22,23,24]. Combined, OD and HT can expose where nominally “high-access” areas fail to generate visits due to socio-economic barriers, perceived safety, or subjective costs [12,25,26], motivating a behavior-grounded alternative that preserves interpretability but replaces uniform parameters with locally calibrated ones.Beyond green space provision, a growing body of research has shown that complex interactions between urban built environments and socio-demographic characteristics shape crime, health risks, and neighborhood well-being [27,28]. Our focus on behavior-validated park service areas extends this line of inquiry to recreational access, using mobility-derived visitation as the outcome.

This study addresses the persistent miscalibration of park service areas by exploiting directly observed visitation intensity rather than assumed radii. We operationalize the “actual service boundary” as an empirical polygon K for each park and day type, constructed from OD-origin clustering and HT aggregation, and use K as the reference against which model-based envelopes are audited. Methodologically, we adopt a transparent three-stage analytical framework, progressing from determinant discovery through heterogeneity analysis to model embedding. Specifically, XGBoost screens key determinants, MGWR quantifies their spatial non-stationarity, and the resultant local effects are embedded into enhanced E2SFCA and potential models to generate location-specific accessibility surfaces. Network isochrones serve solely as routing-aware baselines.

Using Tianjin’s six central districts as a case, we fuse monthly stratified OD (China Mobile) and HT (Baidu) aggregates on a 200 m grid (weekday/weekend) to answer four integrated questions: (i) which factors explain observed visitation intensity in a dense metropolis; (ii) how their spatial heterogeneity can calibrate localized parameters of E2SFCA/potential models; (iii) how OD and HT layers differ by day type and what this implies for omissions vs. commissions; and (iv) how overlap and population-weighted error diagnostics (including coverage, precision, and AUM) can be translated into actionable guidance. Our contributions are threefold: (1) we shift from assumed radii to behavior-validated park service boundaries using OD and HT in a large Chinese city; (2) we establish a structured discovery-to-embedding workflow that begins with XGBoost for variable screening, proceeds to MGWR for spatial heterogeneity analysis, and culminates in parameter embedding for E2SFCA and potential models, with network isochrones with Gaode API retained as routing-aware baselines; and (3) we operationalize diagnostic metrics into a citywide triage framework and time/mode-specific interventions (last-mile links, programming, and capacity tuning), enabling more equitable and evidence-based green space planning.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

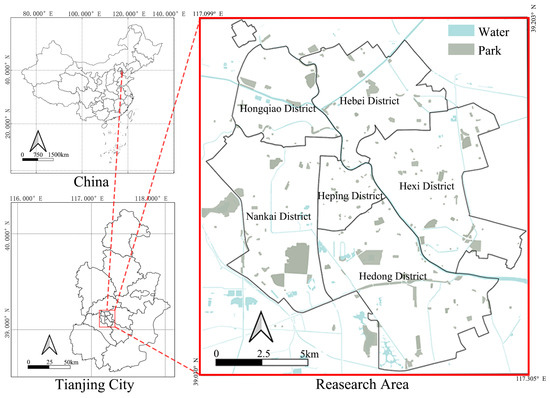

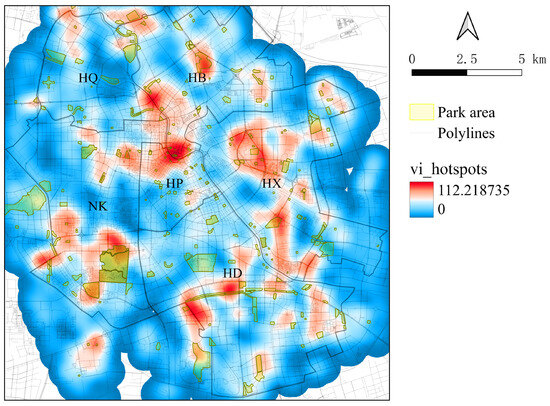

This study focuses on the six central districts of Tianjin, China—Heping (HP), Nankai (NK), Hedong (HD), Hexi (HX), Hebei (HB), and Hongqiao (HQ)—where population density, urban vitality, and demand for urban parks are most concentrated (Figure 1). First, we construct behavior-grounded visitation intensity (VI).

Figure 1.

Study area comprising Tianjin’s six central districts and surrounding buffer zone.

2.2. Data Sources and Harmonization

We assemble a multi-source dataset representing park supply characteristics, socio-demographic context, mobility patterns, and transportation infrastructure. Urban parks and public open spaces are compiled from official planning inventories and point-of-interest datasets [29]. Population distribution is represented using 100 m resolution WorldPop gridded data, projected to 2024 based on 2020 estimates [30,31,32]. Housing prices and census indicators provide socio-economic context and serve as candidate explanatory variables [33].

Mobility patterns are captured through aggregated mobile phone signaling origin–destination data from China Mobile, which records trip counts to parks, and Baidu heatmap data, which reveals fine-grained spatiotemporal activity patterns [21,22,23]. These complementary data sources collectively support the construction of visitation intensity metrics and empirical service boundaries. The street network is derived from OpenStreetMap and processed into functional classifications to support routing analyses [34], with Gaode travel-time estimates generating walking-based isochrones as routing-aware baselines [35]. A composite park quality score ranging from zero to one integrates platform ratings and amenity inventories [36], consistent with recent evidence that user-generated content and online reviews can significantly affect park visitation patterns [36], and serves both as a supply-side weighting factor and an explanatory variable within the analytical workflow.

All datasets are harmonized to establish a consistent 2024 reference year. To address single-day sensitivity and seasonal variations, we implement a monthly stratified sampling approach, selecting one weekday and one weekend day per month for analysis. Mobile origin–destination and heatmap data undergo within-day averaging followed by day-level z-score standardization to mitigate platform-specific scale variations, with subsequent aggregation by day type. All analytical procedures are conducted on a consistent 200 m grid framework, with WorldPop raster data aggregated using areal weighting and other spatial layers aligned through standard raster-vector resampling techniques. Comprehensive parameter details regarding spatial processing, network refinement, and additional validation checks are documented in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Key parameter choices and their roles in the analytical pipeline.

2.3. Privacy and Data Protection

All mobility data inputs consist of provider-aggregated products at 200 m resolution, accessed under commercial licensing agreements that preclude individual-level data access or storage. According to provider documentation, k-anonymity protocols and cell suppression mechanisms are applied during upstream processing of origin–destination and heatmap data tiles [37,38]. All modeling and evaluation procedures operate exclusively on these pre-aggregated, anonymized data products.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Framework

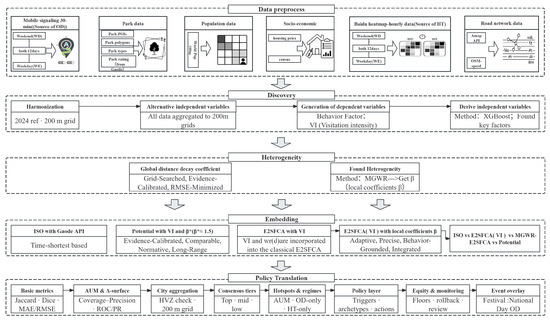

We adhere to a transparent workflow comprising discovery, heterogeneity analysis, and parameter embedding (Figure 2). First, we construct behavior-grounded visitation intensity (VI) and empirical park service boundaries from OD and HT data. Second, XGBoost and MGWR are used to identify and quantify spatially varying determinants of visitation. Third, these local effects are embedded into classical accessibility models (E2SFCA and potential) to obtain location-specific parameters. Finally, we benchmark calibrated and baseline models against empirical boundaries using geometric overlap, population-weighted errors, and area–use mismatch (AUM) and interpret the results for planning and operations.

Figure 2.

Research framework: behavior evidence (, K), determinant discovery (XGBoost), MGWR-based parameter embedding, and evaluation.

3.2. Visitation Intensity and Empirical Boundaries

For each park i and month m, let and be the sampled weekday and weekend day. We combine provider-aggregated OD inflows and HT densities within a 200 m buffer around park entrances to construct day-type-specific visitation intensity:

with unless otherwise stated. For a composite index,

OD represents dynamic realized trips; HT captures ambient activity. Both are normalized within day, aggregated across months by day type, and aligned to the 200 m grid.

The empirical actual service boundary K for each park is defined as the union of high-intensity origin clusters derived from OD/HT on the 200 m grid (weekday/weekend separately). These behavior-validated polygons serve as the reference against which all model-based envelopes B are audited. Clustering details and sensitivity checks are reported in Appendices Appendix D and Appendix E.

For any continuous grid field (ISO with Gaode API, E2SFCA with VI, MGWR–E2SFCA, and potential with ), we obtain a binary service envelope by thresholding . The default operating point is chosen by maximizing Jaccard overlap with an empirical reference surface R (either K or ):

When a reference is not required, is robustly standardized (median and MAD-based scale), and fixed z-cut points on the standardized field define three high-value visitation tiers:

These HVZ tiers provide park-by-park verification envelopes and support citywide aggregation on the 200 m grid; unless stated otherwise, the mid tier serves as the planning-grade envelope in subsequent analyses (Section 3.6).

In event sensitivity experiments, the operating threshold is held constant and only demand weights and decay bandwidths are temporarily adjusted within a preset event radius to ensure comparability with the planning baseline. Operationally, we implement a simple bounded scaling,

with governed by event intensity indicators (see Appendix D for related threshold choices and examples). This event-sensitive overlay yields short-term envelopes for festival or holiday operations while preserving the long-term planning baseline.

3.3. Determinant Discovery and MGWR

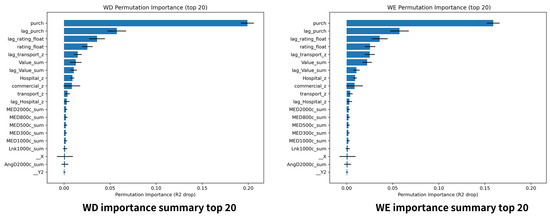

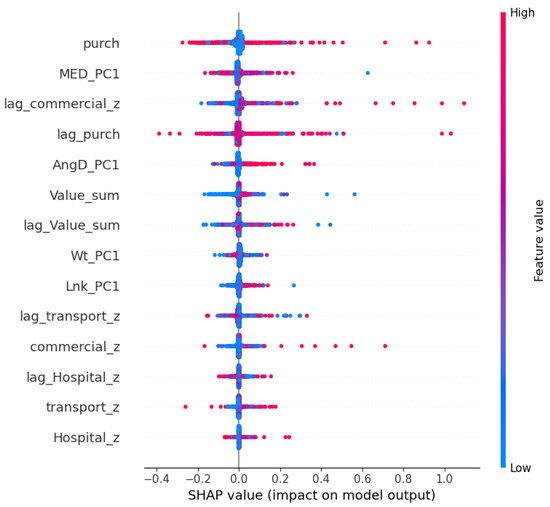

XGBoost is used as a screening tool, not a final predictor, to identify determinants of VI, including population density, road centrality, transit access, land-use mix, POI intensity, housing price, and park quality [39]. Models are trained separately for weekdays and weekends with standard cross-validation; variables with consistent importance and structured residuals are passed to MGWR (see Appendix C and Table A2 for evaluation summaries, feature importance, and SHAP-based interpretation).

Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) is then fitted with as the response, providing location-specific coefficients for selected covariates. These local effects quantify spatial heterogeneity in how infrastructure, land use, and socio-economics shape visitation and form the basis for parameter embedding; see Appendix I for detailed MGWR lenses and co-driver maps.

3.4. Behavior-Informed E2SFCA and MGWR Embedding

We adopt a behavior-informed enhanced two-step floating catchment area method (E2SFCA) [7,8] as the core accessibility model. The structure follows the classic two-step logic, but with three substantive modifications: (1) demand is proxied by the behavior-derived field (OD + HT) on the 200 m grid, instead of the static residential population; (2) supply is quality-weighted as , where encodes park size, facilities, and ratings; and (3) distance decay within a walking catchment m is modeled by a Gaussian kernel (with optional rings), providing a smooth and calibratable decay profile.

Because these changes are primarily in parameterization and inputs, the full uncalibrated E2SFCA equations follow Luo & Qi (2009) [40] and are given in Appendix F for completeness. In the main text, we focus on the calibrated variant where MGWR-derived local effects modify both supply and decay:

where is the calibrated park capacity and the location-specific decay bandwidth for grid cell i. These calibrated parameters replace in the two E2SFCA steps, yielding the MGWR–E2SFCA surface. Analogous embeddings are applied to demand ring weights and, where relevant, to the potential model (details in Table 1).

3.5. Evaluation and AUM

Let B be a model-based service envelope and K the empirical boundary (per park or union). We report standard metrics (formulas in Appendix J, Table A5), including Jaccard and Dice overlap, coverage (), precision (), and population-weighted MAE/RMSE on .

Our main diagnostic is the area–use mismatch:

An AUM value greater than zero indicates over-claiming or commission error, whereas a value less than zero signals under-coverage or omission error. A value approximating zero, in contrast, reflects a well-balanced service envelope. As AUM is a study-specific metric central to our policy interpretation, we have retained its explicit formulation in the main text.

District-level metrics are computed on the same 200 m grid by restricting B and K to each district. Threshold-swept ROC/PR results used to select operating tiers are reported in the Supplement to avoid overloading the main text, and baseline metrics against K for uncalibrated models are summarized in Appendix A, Table A1; also Appendix H shows district-level AUM distributions and rankings.

To provide an intuitive comparison with classical approaches, we decompose model performance into excess and missing areas relative to the empirical boundary. Let K denote the empirical service polygon (per park or union) and B a model-based envelope.

We define

where captures commission (claimed but behaviorally unsupported area) and captures omission (behaviorally supported area left outside the model envelope).

For comparability across parks and districts, we report normalized values

and, in robustness checks, alternatives normalized by total city area. These -surface indicators are computed for the following:

- Network-based isochrones (Gaode; fixed-radius baselines);

- Behavior-informed E2SFCA (with ) and the potential model (global parameters, no MGWR calibration);

- The calibrated MGWR–E2SFCA variant (with local supply and decay).

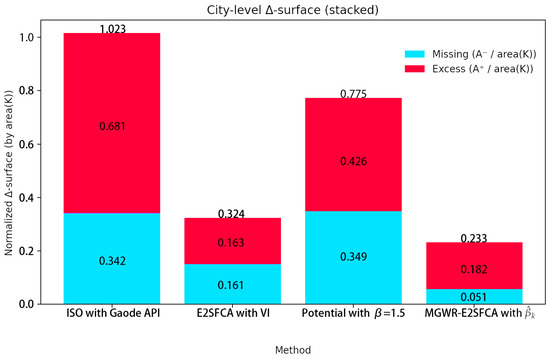

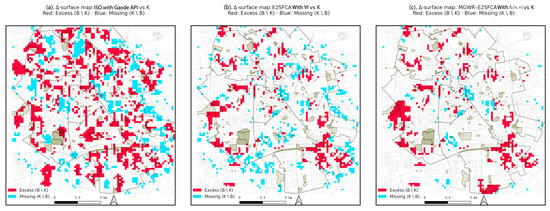

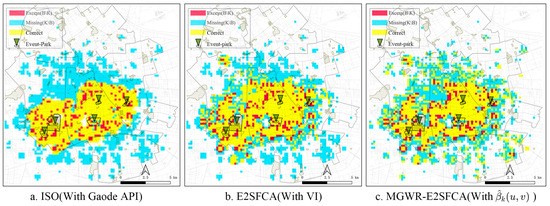

In the results (Section 4.1), stacked bars summarize and by method (Figure 3), and maps visualize spatial patterns of (excess) and (missing) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

City-level -surface diagnostics across methods. Bars show missing area (, cyan) and excess area (, magenta) for ISO (Gaode API), E2SFCA with , the potential model, and MGWR–E2SFCA. Numbers label the contribution of each component and their sum.

Figure 4.

-surface maps for three representative methods. Red cells indicate excess (); blue cells indicate missing (). Panels show (a) ISO with Gaode API, (b) E2SFCA with , and (c) MGWR–E2SFCA with spatially varying coefficients. Park polygons and major roads provide spatial context.The grey-green area in the figure represents the area of each park.

3.6. Hvz-Validated Citywide Aggregation on the 200 m Grid

All model envelopes are first computed per park and per method and then evaluated on the common 200 m grid. Using the HVZ tiers defined in Section 3.2, we verify that per-park envelopes intersect high-value visitation cells and discard isolated low-confidence patches at the park scale (details in the Appendix E).

For citywide reporting in the main text, we adopt a deliberately simple and interpretable consensus tier scheme. Let denote the per-park envelope for park j and method , and let g index 200 m grid cells. We define a method-consensus count

and classify each cell into three tiers:

Cells with fall outside all model-based envelopes and are not displayed.

This cross-model consensus surface on the 200 m grid underpins the citywide tier map (Figure 5) and subsequent policy translation. A more general HVZ-weighted aggregation, including a Validated Contribution Index (VCI) that combines per-park priors, method reliabilities, and tier weights, is reported in Appendix G for readers interested in alternative weighting schemes.

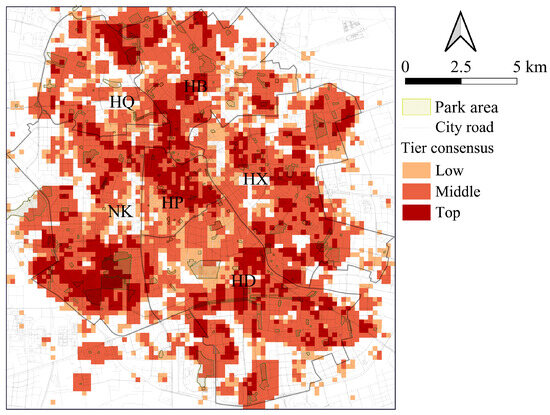

Figure 5.

Citywide tier consensus across ISO, E2SFCA (with ), and MGWR–E2SFCA on the 200 m grid. Park areas and city roads provide spatial context; colors denote low, middle, and top consensus tiers, with warmer colors indicating stronger cross-model agreement. District labels (NK, HP, HB, HX, HD, and HQ) mark administrative context.

4. Results

We first anchor behavioral targets, then compare classical baselines with calibrated variants using -surface totals, proceed to district heterogeneity and spatial -maps, and finally set operating points via consensus tiers.

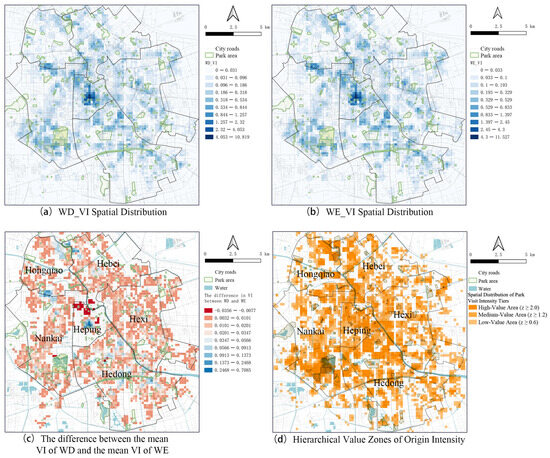

Based on the results in Figure 6c, observed visitation intensity (VI) is concentrated in the urban core and expands toward flagship parks on weekends. On weekdays, VI forms compact, path-dependent catchment areas around community parks, while weekends exhibit larger service footprints along high-centrality corridors—particularly notable near the Heping–Hexi interface. On weekends, VI is more concentrated in Heping District and near several city-level parks located in the southern part of Hebei District. Although VI in Heping District increases markedly on weekends, this may be influenced by its proximity to the railway station and the high density of tourist attractions in the area.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of observed visitation intensity (weekday vs. weekend, i.e., WD vs. WE) across Tianjin’s central districts, showing core concentration and weekend extensions.

In contrast, weekday VI is more spatially dispersed (Figure 6c), suggesting that people tend to visit parks closer to their daily locations rather than traveling to larger or more distant ones. Nonetheless, Heping District still records the highest number of park visits on weekdays, which is closely associated with its high population density and concentration of commercial centers.

The data in Figure 6d are used for subsequent validation and calibration of simulated park service areas. The figure reveals that high mean VI values are not concentrated around the parks—as predicted by traditional ISO and E2SFCA methods—but are instead more widely scattered. Some high-VI areas even appear beyond 5 km from the target parks, outside the central six districts. These scattered high-value points outside the core urban area support the above observation. While some points located along highways may reflect intercepted OD traces from individuals traveling by car or metro from outside the central districts—meaning their true origins could be farther than shown—traditional ISO and E2SFCA methods often fail to simulate such large-volume long-distance travel behavior. These findings underscore the necessity of incorporating empirical OD data to refine conventional modeling approaches.

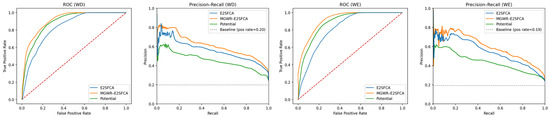

4.1. Multi-Method Comparison and Best Performer

Across weekday and weekend regimes on the 200 m grid, MGWR–E2SFCA is the most balanced: it attains the strongest geometric overlap while keeping population-weighted errors low at the district scale (Figure 3 and Figure 4) (see Appendix A, Table A1). E2SFCA with VI yields compact, ring-weighted envelopes but misses longer-reach flows, especially weekends. The potential model captures broad attraction fields and inter-district corridors but tends to over-extend into ambient-only areas. MGWR–E2SFCA combines the advantages: it selectively extends along high-centrality spines and tightens around compact community parks, reducing commission without sacrificing coverage.

To summarize these method-specific envelopes in a planning-friendly way, we derive a three-level consensus tier map on the 200 m grid (Figure 5). For each grid cell, we count how many of the three benchmark envelopes—ISO isochrones (Gaode API), E2SFCA with , and MGWR–E2SFCA—agree that the cell belongs to the service area. Cells selected by all three methods form the top tier; cells supported by any two methods form the middle tier; and cells covered by at least one method but disagreed upon by others form the low tier. This compresses detailed morphology into a single surface that still reflects MGWR–E2SFCA’s better balance of coverage and precision. Moving from the restrictive top tier to the inclusive low tier, coverage increases while precision declines; population-weighted error is minimized near the middle tier, which we adopt as the default envelope for subsequent diagnostics and policy translation (see Appendix K, Table A6 for quantitative tier summaries).

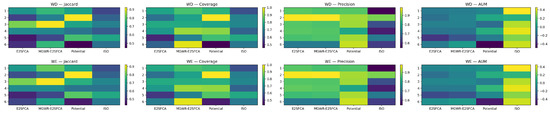

Metrics by district (Figure 7) show that MGWR–E2SFCA is closest to zero area–use mismatch while improving Jaccard over uncalibrated variants. Performance holds from the dense core to peripheral districts. Weekend mismatch is generally higher across methods, reflecting longer-reach, purpose-driven trips that require behavioral calibration.

Figure 7.

District metrics by method: overlap, coverage–precision balance, and area–use mismatch.

Threshold-agnostic evaluation (ROC; Figure 8) indicates complementary strengths. The potential model ranks well at low false-positive rates (precision-oriented use). MGWR–E2SFCA is competitive across broader thresholds (balanced use). Planning translation follows: precision-leaning settings suit HT-only contexts to control commission; recall-leaning settings suit OD-only corridors to repair omission.

Figure 8.

ROC for weekday visitation: three methods are evaluated: E2SFCA (blue), MGWR-E2SFCA (orange), and the Potential model (green). In the ROC plots, the red dashed diagonal represents the performance of a random classifier (AUC = 0.5).In the Precision-Recall plots, the gray dashed horizontal line indicates the baseline precision equal to the positive class prevalence.

Beyond overlap and ROC behaviour, -surface diagnostics summarize how much each envelope over- or under-shoots the behavior-derived reference K. For each method, we compute excess area and missing area and normalize both by . At the city level (Figure 3), ISO shows by far the largest combined -surface (), dominated by over-claimed blocks () in peripheral and corridor-adjacent areas. The potential model also exhibits a large imbalance (≈0.78), with strong commission () and substantial omission (). E2SFCA with improves markedly (≈0.32 in total), keeping over- and under-coverage roughly symmetric. MGWR–E2SFCA performs best, with the smallest normalized -surface (≈0.23) and, critically, a sharp reduction in omission () while maintaining only moderate excess (). In other words, the calibrated variant recovers more behavior-validated area without inflating the envelope.

The spatial pattern of these errors further clarifies how calibration improves envelopes (Figure 4). ISO produces diffuse bands of excess (red) along ring roads and in outer districts, while still leaving scattered missing cells (blue) near barriers and fragmented entries. E2SFCA with compresses the envelope, reducing peripheral excess, but leaves corridor-shaped missing streaks feeding flagship parks, indicating that long-reach inflows are still under-represented. MGWR–E2SFCA realigns the envelope along high-centrality spines and park gateways: missing cells shrink and concentrate around a few residual bottlenecks, and excess becomes more localized around specific over-served fringes rather than citywide halos. These -surface maps are consistent with the stacked indicators and visually illustrate how calibration trades diffuse commission for targeted, behavior-aligned extensions.Taken together, the bar and map diagnostics show that MGWR–E2SFCA repurposes excess from diffuse halos into targeted extensions along behaviorally validated corridors and gateways, which is exactly the type of adjustment planners can act on.

4.2. Citywide Consensus Tiers and Trade-Offs

Using the three-level consensus tiers derived above (Figure 5), we now summarize citywide trade-offs and downstream diagnostics. Consensus tightens from peripheral areas toward the core, with top-tier clusters around the Heping–Hexi interface and along major access spines in Nankai and Hedong. Peripheral disagreements mark locations needing further validation or connectivity upgrades (see Appendix L for detailed district-level narratives).

Intersecting consensus tiers with observed visitation identifies behavior-validated hotspots for priority action (Figure 9). These include core multi-park nodes, corridor nodes, and peripheral flagship destinations, where high model certainty and high visitation coincide.

Figure 9.

Behavior-validated hotspots from intersecting top-tier consensus areas with high visitation intensity.

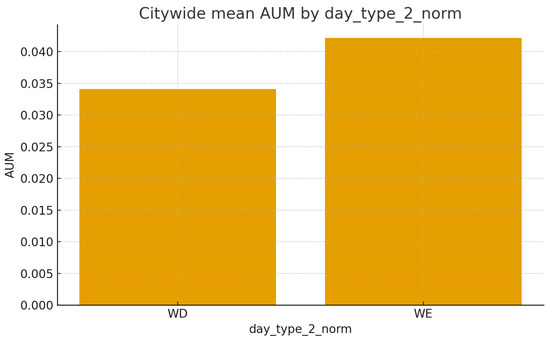

Day type variation in AUM (Figure 10) confirms a weekend tendency toward commission without behavioral calibration, underscoring the need for day-type-specific parameters.

Figure 10.

Citywide comparison of area–use mismatch by day type, showing a weekend commission tendency without behavioral calibration.

Operationally, the top tier marks high-certainty cores for capacity and programming with low risk of over-provision. The middle tier provides a balanced envelope for general planning and standards compliance. The low tier flags potential omission areas where routing suggests opportunity but behavior indicates barriers, guiding targeted connectivity fixes. Coupled with delta-surface diagnostics, the tiers support spatially specific evidence-based interventions and form the basis for the policy translation that follows.

4.3. Holiday-Day Validation: ISO vs. E2SFCA vs. MGWR–E2SFCA

Using the single National Day festival as a one-day stress test, we benchmark three envelopes against the empirical holiday OD field on the 200 m grid and treat five municipal parks as event venues. The holiday reference K is defined from OD hotspots (same quantile and smoothing settings as in the baseline), and each model produces a binary envelope B using the baseline operating threshold fitted by Jaccard so that differences reflect modeling logic rather than threshold drift. We visualize three mutually exclusive sets: excess (), missing (), and correct (), which correspond to commission, omission, and successful hits of observed holiday origins (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Holiday-day (National Day) validation on the 200 m grid. Colors denote excess (, red), missing (, cyan), and correct (, yellow). Panels show (a) ISO (Gaode API), (b) E2SFCA (with ), and (c) MGWR–E2SFCA (with local coefficients). Thresholds are held fixed across methods (baseline Jaccard fit) to ensure comparability.

The comparison confirms the expected trade-offs (Figure 11). The ISO envelope derived from Gaode API travel times attains broad reach but over-claims peripheral areas and street blocks that do not generate holiday trips, yielding extensive excess while still leaving local missing near last-mile barriers. The behavior-informed E2SFCA (with ) reduces excess relative to ISO through a more compact morphology, but shows corridor-shaped missing where long-reach inflows feed flagship parks. The MGWR–E2SFCA variant improves the spatial balance by increasing correct both within core nodes and along approach corridors, while keeping excess controlled; the largest gains appear on transit-aligned spines and park gateways where local coefficients relax decay or upweight mid-distance demand. These patterns indicate that the calibrated variant translates single-day festival evidence into targeted extensions without inflating envelopes, consistent with the short-term operational overlay used elsewhere in this paper. For reporting, we recommend pairing the map with normalized surface indicators , , and the correct-share at both citywide and venue radii.

5. Policy Translation Layer

5.1. Objective and Framework

This layer converts model diagnostics—consensus tiers, area–use Mismatch (AUM), OD–HT regimes, and MGWR-derived determinant geography—into deployable interventions through a compact workflow that starts from quantified triggers, maps locations to operational archetypes, and assembles proportionate action bundles. The aim is consistent, evidence-based prioritization of park access improvements across heterogeneous urban contexts without overloading the main text with procedure.

5.2. Diagnostic Thresholds and Decision Rules

Operational decisions use the mid-tier consensus as the default operating point (coverage target about 0.70; precision target about 0.80). Interventions are triggered when the absolute AUM exceeds 0.10; positive values indicate commission-prone areas that require threshold tightening and activation, while negative values indicate omission-prone corridors that require last-mile connectivity (Table 2). Quarterly deterioration alerts are raised when the change in Jaccard falls below −0.05 or when population-weighted errors increase beyond routine variation. OD-only belts and HT-only pockets identified at tier boundaries are addressed first with corridor fixes or activation before any expansion of service envelopes.

5.3. Spatial Archetypes and Intervention Strategies

Core multi-park nodes combine high visitation and strong model consensus and are managed through entrance load balancing and wayfinding during peaks, targeted transit frequency increases and micromobility placement, temporary amenities in high-use periods, and quality-weighted capacity caps for small parks within clusters. Corridor catchments are defined by weekday OD-only patterns, negative AUM, and transport dominance; the priority is to upgrade the last 200 m of access (crossings, sidewalk continuity, and cycle links), refine gate placement and timing along access spines, strengthen micromobility links to transit, and calibrate models via local bandwidth extension and mid-ring weighting. Peripheral flagship destinations exhibit weekend visitation extensions and mixed drivers; they require timed feeder services and crowd-responsive programming, threshold tightening on ambient-only fringes, bounded weekend-specific multipliers and decay adjustments, and enhanced visitor information and wayfinding for inter-district trips.

Table 2.

Diagnostic–action linkages for evidence-based intervention planning.

Table 2.

Diagnostic–action linkages for evidence-based intervention planning.

| Diagnostic Signal | Interpretation | Priority Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Substantial positive AUM with HT-only presence | Systematic over-estimation of service areas | Threshold tightening through quantile adjustment, quality–capacity capping for smaller parks, localized decay reduction, and activation strategies including lighting and safety improvements |

| Substantial negative AUM with OD-only patterns | Under-service along mobility corridors | Pedestrian infrastructure upgrades including crossing improvements and sidewalk continuity, localized bandwidth extension, mid-ring demand weighting, and micromobility access enhancements |

| High coverage with low precision | Broad but imprecise service delineation | Tier-based intervention targeting, time-dependent capacity adjustments, and entrance placement optimization to reduce spurious reach |

| High precision with low coverage | Restricted service area definition | Tier expansion along corridors, supplemental transit services, access point diversification, and pedestrian timing improvements |

| Quarterly performance deterioration | Emerging access barriers or changing patterns | Rapid barrier assessment, temporary wayfinding deployment, and parameter recalibration based on marginal impact analysis |

5.4. Model Parameter Calibration

Parameter updates remain bounded and documented to avoid oscillation. Bandwidths are adjusted where transport dominance or HT-only fringes are observed; ring weights and capacity factors follow the local determinant geography; and weekday and weekend changes are logged separately. Each update records before–after values for AUM, Jaccard, and population-weighted errors, with reversion to previous settings if trigger conditions persist.

5.5. Temporal and Modal Considerations

Weekday operations emphasize corridor safety, sidewalk continuity, and bicycle access, reflected in the model emphasis on corridor bandwidth and mid-ring weights. Weekend operations emphasize service frequency, temporary infrastructure, and programming, reflected in mixed-use sensitivity and capacity management within predefined bounds.

5.6. Equity Integration and Performance Monitoring

Equity is integrated by stratifying metrics by income and age and by setting minimum service floors for vulnerable groups. A quarterly review tracks AUM distributions, the coverage–precision balance, population-weighted errors, and crowding indicators; tracts with persistent shortfalls are escalated for targeted interventions and, where warranted, capital investment.

5.7. Implementation Pathway

Implementation proceeds from pilots at representative sites to corridor-scale deployment, followed by an annual citywide reassessment and parameter refinement. A change log links triggers, parameter edits, and outcomes to ensure traceability and auditability throughout the cycle.

6. Discussion

6.1. Evidence-Anchored Contributions

Behavior-informed calibration of classical accessibility models yields substantive accuracy gains. The MGWR–E2SFCA variant raises geometric overlap across weekday and weekend regimes and lowers population-weighted errors relative to uncalibrated baselines, with threshold-agnostic checks (ROC/PR) corroborating these patterns. Two failure modes explain the gains: omission along weekday mobility corridors and commission around weekend ambient pockets. Embedding spatially varying determinants—particularly transport accessibility and mixed-use context—into local supply and decay parameters addresses both modes and aligns evaluation metrics (coverage, precision, and AUM) with planning targets.

6.2. Mechanistic Insights Through Parameter Embedding

Determinant geography differs by day type: weekdays are path-dependent along commuting spines, whereas weekends are purpose-driven and co-driven by transport and mixed-use contexts. Parameter embedding reflects these contrasts by extending bandwidth and mid-ring weights along corridors to repair omission, while tightening decay and capping quality-weighted capacity on ambient-only fringes to control commission. Morphological differences across models (compact near-field, corridor-tracing, and broad attraction fields) are interpretable as alternative parameter regimes.

6.3. Robustness and Operational Considerations

Comparative evaluation shows complementary strengths: the potential model ranks well at low false-positive rates for precision-leaning use, while MGWR–E2SFCA offers balanced performance across thresholds for planning-grade use. Operating points therefore trade commission control for omission repair; precision-leaning settings suit HT-only contexts, and recall-leaning settings suit OD-only corridors. Using a common metric set from evaluation through to deployment ensures coherent tuning and traceable interventions.

6.4. Limitations and Validation Safeguards

Provider-aggregated mobility inputs may induce representation bias; determinant effects are correlational rather than causal; unobserved perception and safety factors are not explicitly modeled; evolving infrastructure and amenities require periodic recalibration; parameter updates are bounded, documented, and subject to rollback when trigger violations persist; and uncertainty is quantified via bootstrap confidence intervals and sensitivity analyses reported in the Appendix K.

6.5. Transferability and Implementation Pathway

Transferability rests on four elements. First, standardized data ingestion and baseline establishment ensure that OD, HT, population grids, and park attributes can be imported with minimal local customization. Second, the discovery-to-embedding workflow—XGBoost screening followed by MGWR and parameter embedding—allows existing accessibility tools to inherit local behavioral patterns without changing their core structure. Third, routine monitoring with coverage, precision, AUM, and population-weighted errors, combined with guarded rollback on triggers (e.g., or Jaccard on a quarterly basis), provides a controlled environment for updating parameters rather than ad hoc retuning. Fourth, an equity overlay that enforces minimum service floors and prioritizes underperforming tracts ensures that diagnostic gains translate into fairer outcomes. Together, these elements make the framework portable across cities that can access aggregated mobility and population data while retaining a transparent link between evidence, parameters, and planning actions.

7. Conclusions

This study advances an interpretable analytical pipeline that systematically connects machine learning-based determinant discovery with parameterized accessibility modeling. By integrating XGBoost screening, MGWR heterogeneity quantification, and behavioral embedding into established accessibility frameworks, the approach demonstrates substantial improvements in service area delineation accuracy for Tianjin’s core urban districts. The calibrated models achieve significantly higher geometric alignment with empirical visitation patterns while reducing population-weighted errors, providing planners with more reliable tools for equitable green space provision.

A key methodological innovation lies in the development of an event-sensitive operational overlay that enables responsive management of temporary visitation surges without compromising long-term planning baselines. During festival periods and seasonal events, this framework temporarily adjusts demand weights, relaxes decay parameters within designated radii, and stages supplemental capacity at key venues. The dual-output reporting mechanism—maintaining distinct baseline and operational modes—ensures that transient visitation patterns do not distort fundamental planning parameters, while delta-surface comparisons provide clear visual guidance for temporary envelope adjustments.

The Policy Translation Layer operationalizes these analytical advances through a structured decision framework that converts coverage–precision diagnostics into targeted interventions. The integration of consensus tiers with area–use mismatch metrics enables systematic triage across urban contexts, with positive mismatches triggering threshold refinement and activation strategies, while negative values guide connectivity improvements and service enhancements. This diagnostic framework establishes an explicit coverage–precision frontier that supports evidence-based resource allocation aligned with municipal priorities and equity objectives.

The methodological pipeline maintains the conceptual transparency and practical familiarity of established accessibility tools while incorporating locally calibrated, behaviorally validated parameters. The approach demonstrates robust transferability through standardized implementation protocols and conservative parameter update bounds. While acknowledging limitations related to data aggregation and correlational calibration, sensitivity analyses confirm consistent performance improvements across threshold selections and spatial contexts.

Future methodological development will focus on extending temporal stratification to capture seasonal variations, incorporating finer demographic disaggregation to enhance equity analysis, and developing quasi-experimental frameworks for evaluating access interventions. The event-sensitive overlay will be generalized through integration with richer intensity indicators, including permit data, ticketing information, and IoT sensor networks, supported by more sophisticated automatic reversion protocols. These advancements will further strengthen the framework’s capacity to support dynamic, evidence-based planning in complex urban environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W., L.Z. and S.Z.; methodology, L.W.; software, L.W. and L.Z.; validation, L.W., L.Z. and Y.H.; formal analysis, L.W.; investigation, L.W.; resources, L.W. and L.H.; data curation, L.W. and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, L.Z., S.Z. and Y.H.; visualization, L.W. and S.Z.; supervision, L.Z. and Y.H.; project administration, L.Z. and Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it used only provider-released, k-anonymized, 200 m × 200 m aggregate mobility and heatmap data with no personally identifiable information and involved no interaction with human participants or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study used only provider-released, k-anonymized, 200 m × 200 m aggregate mobility and heatmap data with no personally identifiable information and involved no interaction with human participants. Written informed consent for publication was not required because no identifiable individuals are included.

Data Availability Statement

Public datasets used in this study include OpenStreetMap (April 2024 snapshot) and WorldPop gridded population (https://www.worldpop.org/; accessed on 30 October 2024). Licensed mobility datasets (China Mobile OD aggregates and Baidu heatmaps) cannot be shared publicly. Replication code and derived 200 m grid indicators are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank China Mobile and Baidu Inc. for licensed mobility aggregates, Gaode for routing-time APIs, OpenStreetMap contributors for the road network data, and the WorldPop project for gridded population data. We also acknowledge administrative and technical support from our institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders and data providers had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUM | Area–Use Mismatch |

| E2SFCA | Enhanced Two-Step Floating Catchment Area |

| 2SFCA | Two-Step Floating Catchment Area |

| MGWR | Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression |

| OD | Origin–Destination (mobile-signaling flows) |

| HTs | Heatmap Tiles (Baidu) |

| VI | Visitation Intensity |

| WD/WE | Weekday/Weekend |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| AP | Average Precision |

| MAEw | Population-weighted Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSEw | Population-weighted Root Mean Square Error |

| JSD | Jensen–Shannon Divergence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| POI | Point of Interest |

| CRS | Coordinate Reference System |

| EPSG | EPSG Code (projection identifier) |

| GCJ-02 | Chinese Geodetic Datum (“Mars” coordinates) |

| AICc | Corrected Akaike Information Criterion |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting (GBDT implementation) |

| K | Empirical Service Boundary Polygon |

| Consensus Tiers (top/mid/low) | |

| HP/NK/HD/HX/HB/HQ | Heping, Nankai, Hedong, Hexi, Hebei, Hongqiao (districts) |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Calibrated models vs. baselines on a 200 m grid (weekday/weekend). Per-district stats use the median across districts; citywide-union Jaccard shown below. Population-weighted errors use WorldPop as weights.

Table A1.

Calibrated models vs. baselines on a 200 m grid (weekday/weekend). Per-district stats use the median across districts; citywide-union Jaccard shown below. Population-weighted errors use WorldPop as weights.

| Weekday (WD) | Weekend (WE) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model/Stat | Jaccard (Med) | AUM | Jaccard (Med) | AUM | ||||

| E2SFCA (uncal.) | 0.434 | 0.248 | 0.321 | −0.154 | 0.462 | 0.244 | 0.322 | −0.155 |

| Potential ( = 1.5) | 0.515 | 0.235 | 0.288 | −0.135 | 0.509 | 0.213 | 0.284 | −0.137 |

| Isochrone (Gaode API) | 0.112 | 0.181 | 0.382 | 0.437 | 0.098 | 0.185 | 0.381 | 0.441 |

| MGWR–E2SFCA | 0.744 | 0.161 | 0.244 | −0.141 | 0.723 | 0.165 | 0.241 | −0.143 |

| Potential (calibrated) | 0.664 | 0.166 | 0.231 | −0.133 | 0.667 | 0.171 | 0.237 | −0.136 |

Citywide-union Jaccard: WD = 0.613, WE = 0.609.

Appendix B

Table A2.

XGB evaluation summary.

Table A2.

XGB evaluation summary.

| Tag | Train_R2 | Train_RMSE | OOF_R2 | OOF_RMSE | CV_Best_R2 | Moran_ Residual_ Train_I | Moran_ Residual_ Train_p | Moran_ Residual_ OOF_I | Moran_ Residual_ OOF_p | y_source | y_name | Groups | knn_k | ES_rounds | ES_val_frac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WD | 0.619 | 0.892 | 0.502 | 1.939 | 0.584 | 0.071 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.21 | constructed_ts | VI_target | 12 | 12 | 40 | 0.2 |

| WE | 0.598 | 0.871 | 0.499 | 1.934 | 0.595 | 0.076 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.34 | constructed_ts | VI_target | 12 | 12 | 40 | 0.2 |

Appendix C. Screening and Variable Dictionary

Presentation of XGBOOST Training Results.

Figure A1.

XGBoost feature importance (weekday vs. weekend). Transport centrality dominates on WD; mixed-use/amenity context gains on WE.

Table A3.

Variable dictionary used in screening and MGWR embedding.

Table A3.

Variable dictionary used in screening and MGWR embedding.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| purch, lag_purch | Park type indicator; kNN spatial lag |

| rating_float, lag_rating_float | Mean user rating (0–5) and spatial lag |

| Value_sum | Population/value aggregate within grid cell |

| transport_z, commercial_z, Hospital_z | POI densities (z-scores) |

| lag_* | kNN spatial lags of corresponding variables |

| MED300/500/800/1000/2000c_sum | sDNA Mean Euclidean Depth within radius (m) |

| AngD2000c_sum | sDNA Mean Angular Depth (2 km along-network) |

| Lnk1000c_sum | Reachable link count (1 km along-network) |

| __X, __Y2 | Coordinate trend terms (x, ) |

The asterisk (*) serves as a placeholder, representing all corresponding variables involved in the XGB calculations within this study.

Figure A2.

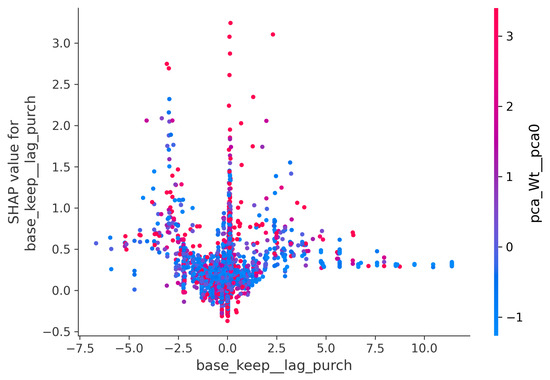

The SHAP values of the WD_XGBoost model. WE values.

Figure A3.

Commercial density.

Figure A4.

Neighborhood transport accessibility.

Figure A5.

Neighborhood rating.

Figure A6.

Neighborhood park typology.

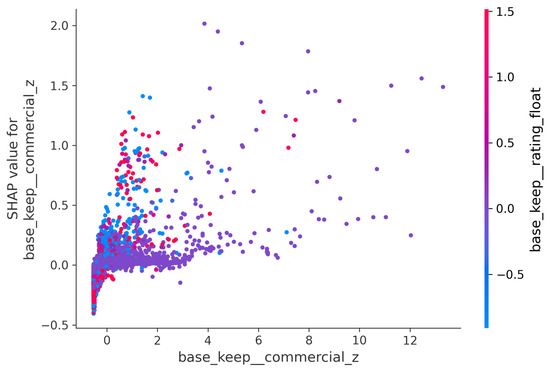

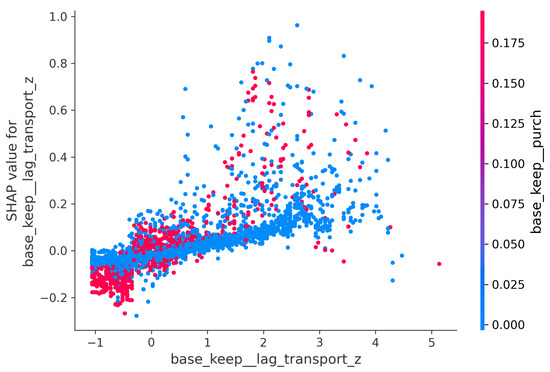

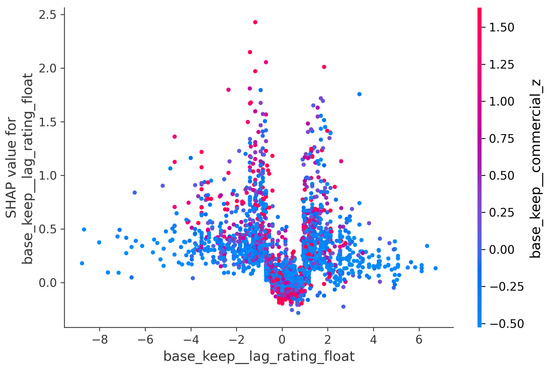

Interpretation of SHAP dependence (WD). For readability we drop the pipeline prefix base_keep__. Overall, the dependence plots confirm interpretable, policy-relevant patterns with clear thresholds and interactions:

- (1)

- Commercial density (commercial_z, colored by rating_float): SHAP effects increase nonlinearly—rising quickly from low to moderate levels (∼0–2 z) and then showing diminishing returns. Warmer colors (higher park ratings) shift points upward, indicating that higher-quality parks amplify the gains along commercial corridors.

- (2)

- Neighborhood transport accessibility (lag_transport_z, colored by purch): This shows a largely monotonic positive effect with a practical threshold around 1–2 z. When accessibility is poor (<0 z), certain park types (higher purch) exhibit a negative intercept, implying that “weak transit × specific typologies” depress usage; beyond the threshold, improvements in transport lag produce sizeable gains regardless of type.

- (3)

- Neighborhood rating (lag_rating_float, colored by commercial_z): This shows a nonlinear pattern with weak contributions near the citywide mean and stronger positive effects as neighborhood ratings deviate upward. Higher commercial intensity (warmer colors) magnifies the rating effect, evidencing a synergy between popular parks and commercially active areas.

- (4)

- Neighborhood park typology (lag_purch, colored by pca_Wt_pca0): This shows a convex (“”) relationship—minimal contribution around zero and higher contributions at both tails (typology scarcity or concentration). The effect is amplified where the street network principal component (pca_Wt_pca0) is high, suggesting that typology structure is more salient in well-connected networks.

Taken together, the plots indicate monotonic or thresholded positive effects for accessibility and commercial context, a rating–commercial synergy, and a convex typology effect modulated by network centrality—consistent with behavioral mechanisms for weekday park visitation.

Appendix D. Od–Ht Numerical Decompositions and Thresholds

This section documents the intermediate diagnostics used to construct empirical visitation fields and boundaries, without overloading the main text with technical detail.

Table A4.

Citywide OD–HT decomposition by day type at the chosen high quantiles (held constant within day type). Areas in km2; shares in %.

Table A4.

Citywide OD–HT decomposition by day type at the chosen high quantiles (held constant within day type). Areas in km2; shares in %.

| Day Type | Union | OD-Only | HT-Only | Overlap | Jaccard (OD, HT) | Quantile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WD | 55.8 | 39.9 (71.5%) | 13.1 (23.5%) | 2.7 (4.8%) | 0.048 | (as used) |

| WE | 34.7 | 18.8 (54.2%) | 14.2 (40.9%) | 1.6 (4.6%) | 0.046 | (as used) |

Quantile choices are fixed by day type to isolate regime shifts. OD-only belts indicate mobility conduits (omission risk if envelopes too tight); HT-only pockets indicate ambient without entries (commission risk if envelopes too fat).

Appendix E. Construction of Empirical Boundaries K (Brief)

For each park i and day type (WD/WE), we first allocate OD inflows and HT densities to 200 m grid cells to obtain a visitation field . We then robustly standardize within park and day type and retain cells above a high quantile (equivalently, a z-score threshold) as candidate origins.

Spatially contiguous candidate cells are grouped using 8-neighborhood connectivity; very small, isolated patches are discarded as noise. The remaining clusters are converted to polygons by taking the union of their grid footprints and lightly simplifying boundaries.

For each park, the main empirical boundary is defined as the largest polygon plus any stable distant clusters that account for non-trivial shares of (e.g., long-reach origins of flagship parks). Sensitivity checks confirm that cores of are stable across a range of reasonable thresholds.

Appendix F. Classical Accessibility Models (Summary)

For completeness, we briefly summarize the classical formulations that our behavior-informed variants build on.

The two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) family follows Luo and Qi (2009) [40]. Step 1 computes a park-side ratio , and Step 2 computes grid-level accessibility , where is demand, supply, distance, and a decay function. In this study we adopt a Gaussian and replace population-based by behavior-derived , as described in the main text.

The potential model uses a standard distance-decay potential: within a maximum interaction distance; our calibrated variant embeds MGWR-derived local effects into and/or , again as detailed in the main text. Full derivations are omitted here because they are well known in the literature.

Appendix G. Validated Contribution Index

Define . The city-level Validated Contribution Index is

If and , then and reduces to the Boolean OR over all , i.e., the current “max-overlays” product.

Appendix H. District AUM Details

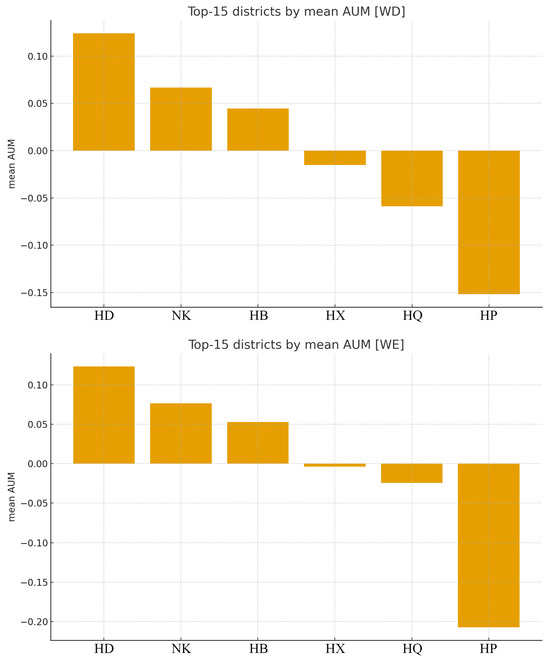

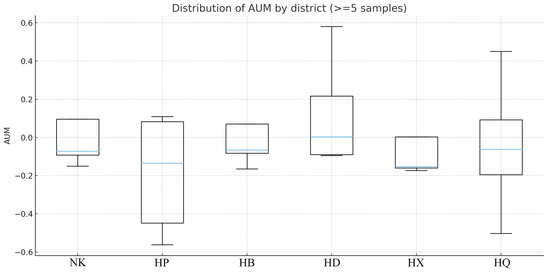

Districts with strongly positive AUM require threshold tightening and activation, whereas negative AUM highlights corridors where last-mile connectivity is insufficient.

Figure A7.

Top-15 districts by mean AUM (WD on top, WE on bottom). Positive bars ⇒ boundary tightening (threshold/capacity recalibration); negative bars ⇒ last-mile fixes.

Figure A8.

Distribution of AUM by district (parks with ). Large IQR indicates strong within-district heterogeneity, suggesting differentiated actions between community and flagship parks.

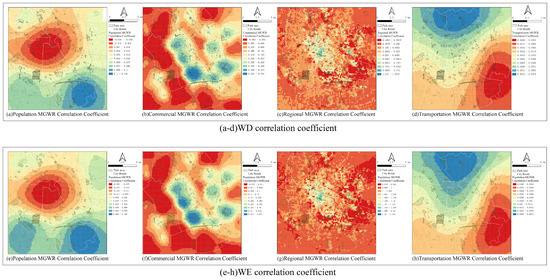

Appendix I. MGWR Lenses: Co-Drivers, Dominance, Contrasts, and WE–WD

This section provides supporting diagnostics for the MGWR models, illustrating how key determinants and spatial heterogeneity underpin the calibrated accessibility surfaces.

Figure A9.

Spatial distribution of MGWR coefficients for selected determinants.

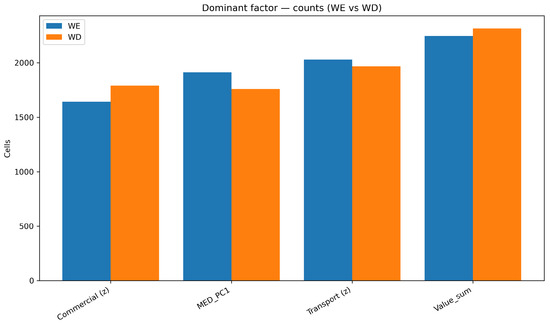

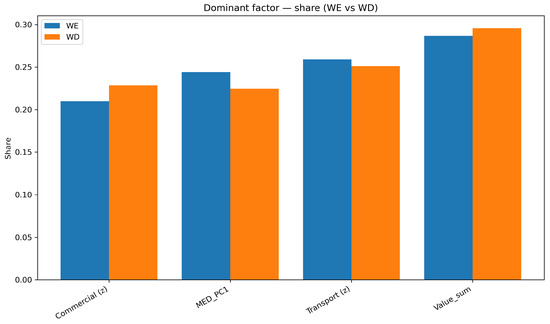

Figure A10.

Dominant-factor (Top-1) grid counts: WE vs. WD. On WE, Transport and MED_PC1 expand; on WD, Commercial and Value_sum occupy relatively more cells.

Figure A11.

Dominant-factor (Top-1) shares: WE vs. WD. Weekend shifts toward purpose/scene-driven travel (Transport/MED_PC1) vs. the weekday path-dependent pattern (Commercial/Value_sum).

Appendix J. Metric Definitions and Notes

This section provides formal definitions of the evaluation metrics used in the main text, clarifying how coverage–precision balance and area–use mismatch (AUM) are computed from model envelopes B and empirical boundaries K.

Table A5.

Definitions used in evaluation. B = model envelope; K = empirical boundary; and = area.

Table A5.

Definitions used in evaluation. B = model envelope; K = empirical boundary; and = area.

| Metric | Definition |

|---|---|

| Jaccard | |

| Dice | |

| Coverage | |

| Precision | |

| AUM | (balance: 0 ideal) |

Extremes: If : coverage and precision ⇒ AUM (omission). If : coverage and precision ⇒ AUM (commission).

Appendix K. Consensus Tiers: Quantitative Summary

This section summarizes quantitative properties of the three consensus tiers, showing how coverage, precision, and population-weighted errors evolve from the top tier to the low tier and thereby supporting the tier-based operating point used in the main text.

Table A6.

Indicative coverage/precision patterns and relative weighted errors at three consensus tiers . Values in parentheses are approximate or relative, summarizing the operating point trade-offs.

Table A6.

Indicative coverage/precision patterns and relative weighted errors at three consensus tiers . Values in parentheses are approximate or relative, summarizing the operating point trade-offs.

| Tier | Coverage | Precision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top | ∼0.76 (moderate) | ∼0.98 (very high) | low–mid | low–mid |

| Middle | ∼0.83 (balanced) | ∼0.73 (balanced) | minimum | minimum |

| Low | ∼0.94 (very high) | ∼0.64 (lower) | higher | higher |

Interpretation: Top = precision-first (least-regret cores); Middle = planning-grade default (balance); and Low = coverage-first (conservative audit).

Appendix L. District Narratives (Long Form)

- HP.

- Large, continuous consensus core with potential-only extensions along southern/eastern access spines (longer-reach inflows to comprehensive/specialized parks). MGWR–E2SFCA maintains breadth while containing near-field commission.

- NK.

- Interior dominated by consensus; CAL-only islands on western flank (corridor selectivity); scattered POT-only patches on the periphery. Corridor-shaped demand argues for selective extension along spines.

- HB.

- Patchwork of CAL-only and consensus cells around clusters, indicating heterogeneous conversion from ambient to realized trips. Rim excess suggests threshold/capacity tightening.

- HD.

- Broad consensus swath with POT-only margins along outer corridors, coherent with a cross-district linkage role. Selective MGWR extensions trace the eastward spine.

- HX.

- POT-only coverage in the north (longer-reach draws) co-exists with CAL-only belts along the southern edge (last-100 m frictions near gates). Tighten near-field while preserving connectors.

- HQ.

- Dispersed CAL-only and consensus pockets shaped by local street access and small-park distribution; focus on micro-connectivity and gate wayfinding.

References

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Urban Green Spaces and Health: A Review of Evidence; Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Guo, S.; Song, C.; Pei, T.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Du, Y.; Chen, J.; Fan, Z.; Tang, X.; Peng, Y.; et al. Accessibility to urban parks for elderly residents: Perspectives from mobile phone data. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, M.; Wu, S.; Li, B. Exploring the disparities in park accessibility through mobile phone data: Evidence from Fuzhou of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neutens, T. Accessibility, equity and health care: Review and research directions for transport geographers. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 43, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lyu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, D. An Improved Two-Step Floating Catchment Area (2SFCA) Method for Measuring Spatial Accessibility to Elderly Care Facilities in Xi’an. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 10, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, R.; Tian, G.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Fekete, A. Equity Study on Urban Park Accessibility Based on Improved 2SFCA Method in Zhengzhou, China. Land 2022, 11, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.S.; Liao, C.H. Exploring an integrated method for measuring the relative spatial equity in public facilities in the context of urban parks. Cities 2011, 28, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, W.; Qian, C.; Cao, M.; Yang, T. Gravity-based models for evaluating urban park accessibility: Why does localized selection of attractiveness factors and travel modes matter? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2023, 51, 904–922, (Original work published 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. Assessment and optimization of spatial equity for urban parks: A case study in Nanjing, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Jiang, H.; Yi, D.; Liu, R.; Qin, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. PM2SFCA: Spatial Access to Urban Parks, Based on Park Perceptions and Multi-Travel Modes. A Case Study in Beijing. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Song, J.; Keith, M.; Akiyama, Y.; Shibasaki, R.; Sato, T. Delineating urban park catchment areas using mobile phone data: A case study of Tokyo. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 81, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, X. An SCM-G2SFCA Model for Studying Spatial Accessibility of Urban Parks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, H.; Lin, G.; Lu, Y. Exploring temporal and spatial patterns and nonlinear driving mechanism of park perceptions: A multi-source big data study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 119, 106083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Lee, J.; Kim, H. Sheltering in place: Unveiling how urban park characteristics shaped visiting patterns during the pandemic using machine learning, Seoul, South Korea. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, J.; Chuang, I.-T.; Sila-Nowicka, K. Measuring spatial inequality of urban park accessibility and utilisation: A case study of public housing developments in Auckland, New Zealand. Landscape Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guan, C.; Wu, L.; Li, Y.; Nie, X.; Song, J.; Kim, S.; Akiyama, Y. Visitation-based classification of urban parks through mobile phone big data in Tokyo. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 167, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwu, M.; Atkinson, P.; Jiang, B. Urban park accessibility assessment using human mobility. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2024, 30, 2341700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Li, J.; Yan, H. Measuring the Spatial Accessibility of Parks in Wuhan, China, Using a Comprehensive Multimodal 2SFCA Method. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Cheng, Y. Improving the multi-modal two-step floating catchment area method in spatial accessibility evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, E.; Zhu, K. Human Origin–Destination Flow Prediction Based on Large Scale Mobile Signal Data. In Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhou, M. Urban human activity density spatiotemporal variations and the relationship with geographical factors: An exploratory Baidu heatmaps-based analysis of Wuhan, China. Growth Change 2020, 51, 12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, L. Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Vitality in the Central Area of Chongqing Based on Bai-du Heatmap. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2021, 37, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wei, D.; Zhao, P.; Yang, L.; Lu, Y. Revealing the Spatiotemporal Pattern of Urban Vibrancy at the Urban Agglomeration Scale: Evidence from the Pearl River Delta, China. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 181, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, J.; Li, P.; Kobayashi, H.; Song, X.; Shibasaki, R. Utilizing mobile phone big data to simulate the impact of park boundary openness on the accessibility. Cities 2025, 156, 105547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, D.; Peng, H.; Cao, M.; Yao, Y. Is Perceived Safety a Prerequisite for the Relationship Between Green Space Availability, and the Use and Perceived Comfort of Green Space? Wellbeing, Space Soc. 2025, 8, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, L.; Tsou, S.; Wang, L.; Hu, Y.; Yang, K. Exploring the Complex Association Between Urban Built Environment, Sociodemographic Characteristics and Crime: Evidence from Washington, D.C. Land 2024, 13, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, L. Mechanisms Influencing the Factors of Urban Built Environments and Coronavirus Disease 2019 at Macroscopic and Microscopic Scales: The Role of Cities. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1137489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M. Decoding the Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Ecological Resilience in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Urban Agglomeration: A Deep Learning Approach. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldPop. WorldPop China 100 m Population Density, Version 2.0; WorldPop: Southampton, UK, 2020; Available online: https://hub.worldpop.org/geodata/summary?id=49919 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Rakotoarisoa, M.; Jones, J.; Rakotonarivo, O.; Rajaonarivelo, M.; Schüßler, D. Invisible people: Exploring how well remote-sensed datasets reveal the distribution of forest-proximate populations. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WorldPop. WorldPop China 100 m Population Density; Version 1.0; WorldPop: Southampton, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, C. The Use of Housing Price As a Neighborhood Indicator for Socio-Economic Status and the Neighborhood Health Studies. Spat. Inf. Res. 2013, 21, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gil, J. Building a Multimodal Urban Network Model Using OpenStreetMap Data for the Analysis of Sustainable Accessibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Lin, X.; Yu, J.; Tang, C. Integrating Travel Survey and Amap API Data Into Travel Mode Choice Analysis with Interpretable Machine Learning Models: A Case Study in China. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 27852–27867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, X.; Lu, Y. Deciphering the Effect of User-Generated Content on Park Visitation: A Comparative Study of Nine Chinese Cities in the Pearl River Delta. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Martínez, S.; Sánchez, D. Decentralized k-anonymization of trajectories via privacy-preserving tit-for-tat. Comput. Commun. 2022, 190, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cai, M.; Chen, X. Privacy Protection Method for Cellular Signaling Data Based on Genetic Algorithm. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2023, 149, 7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ji, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, Y. Exploration of Differences in Housing Price Determinants Based on Street View Imagery and the Geographical-XGBoost Model: Improving Quality of Life for Residents and Through-Travelers. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Qi, Y. An Enhanced Two-Step Floating Catchment Area (E2SFCA) Method for Measuring Spatial Accessibility to Primary Care Physicians. Health Place 2009, 15, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).