Abstract

Rainfall characteristics during the rice growth period were analyzed using long-term data (1986–2017) from three typical irrigation stations, namely, Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang in East China. Annual rainfall, concentration indices, and monthly distributions were examined, and the soil–water balance method was applied to estimate effective rainfall (precipitation) from 2018 to 2020. Results showed that rainfall during the growth period generally accounted for 40–80% of the annual total rainfall, with more than 60% of the years exceeding half of the annual rainfall. The effective precipitation utilization coefficients at Pinghu Station reached 0.573, 0.644, and 0.764 in 2018, 2019 and 2020, respectively, indicating relatively high utilization efficiency and confirming effective precipitation as a major water source during rice growth. High utilization was observed for extreme rainfall events (≥30 mm or ≤5 mm), whereas moderate rainfall (5–30 mm) showed larger variability due to soil and management factors. To further improve quantitative assessment, a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model was employed to predict daily effective precipitation using rainfall, antecedent precipitation index (API), drought days, and extreme rainfall indicators as inputs. The effective precipitation utilization coefficient was then derived as the ratio of effective to total precipitation. The optimized SVR model achieved a coefficient of determination of and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 4.58 mm for daily effective precipitation, effectively capturing the nonlinear relationship between rainfall characteristics and effective precipitation. These findings highlight that the machine learning method can complement existing estimation models, offering an alternative tool for irrigation scheduling and water-saving crop cultivation.

1. Introduction

Rice is a water-intensive crop that requires substantial water throughout its growth cycle. In addition to artificial irrigation, rainfall serves as a major source for meeting the crop’s water demand during development [1,2,3]. Consequently, analyzing the characteristics of rainfall and its effective precipitation during the rice-growing season is of critical importance for understanding the hydrological environment of paddy fields [4,5]. Furthermore, effective precipitation, as one of the key components of the paddy water balance, is also an essential element in the development of irrigation forecasting models. Study on effective precipitation in paddy fields has therefore become a necessary step in supporting the modernization of irrigation district information systems [6,7].

In recent years, numerous studies have examined the rainfall characteristics and effective precipitation for different crops across various regions. For example, Wei [8] investigated the spatial and temporal distribution of precipitation during the summer maize growing season in the Heilonggang Basin, where groundwater over exploitation is severe, providing a scientific basis for improving effective precipitation efficiency. Wu et al. [9] analyzed effective precipitation and crop water demand for cassava in Guangxi and reported significant differences in water requirements across growth stages, with a southeast–northwest distribution gradient. Zhang et al. [10] assessed the effective utilization of precipitation for flue-cured tobacco in Guizhou to optimize irrigation allocation and water-use efficiency. Similarly, Chen [11] and Chen et al. [12] explored the temporal and spatial characteristics of effective precipitation for wheat and cotton, offering valuable references for irrigation planning and land water management. However, research focusing on rainfall characteristics and effective precipitation in paddy fields remains relatively limited, which has gradually emerged as a key research gap in the study of water and soil cycling in rice cultivation systems.

Recent years have seen a growing body of data-driven studies that integrate machine learning with irrigation management and hydrological prediction. Dehghanisanij et al. [13] applied an intelligent model to evaluate functional properties of irrigated cotton under treated wastewater, demonstrating the potential of machine learning for optimizing water use efficiency. Emami et al. [14] employed a meta-heuristic-optimized SVR model for discharge coefficient prediction on labyrinth weirs, further highlighting the suitability of SVR for nonlinear hydrological processes. Achite et al. [15] combined an election algorithm with support vector regression to estimate hydrological drought indices with improved accuracy. However, few studies have focused on effective precipitation utilization in paddy fields, particularly in East China.

Previous studies have mainly focused on characterizing rainfall regimes or estimating effective precipitation for individual crops and regions, while systematic analyses for paddy fields in East China remain scarce. In particular, there is a lack of studies that combine long-term rainfall statistics, soil–water balance-based effective precipitation, and data-driven prediction models within a unified framework for irrigated rice systems. It is hypothesized that the utilisation coefficients of effective precipitation can be predicted with reasonable accuracy using the SVR model, drawing on input variables related to rainfall characteristics and field water conditions. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that these factors play a key role in determining how efficiently rainfall is utilised in rice cultivation, and that a machine learning model like SVR can capture these complex relationships. Therefore, this study aims to: (i) characterise the long-term rainfall pattern during the rice-growing season at three typical irrigation stations in East China; (ii) quantify the effective precipitation and its utilisation coefficient using a soil–water balance approach; (iii) develop a Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to predict daily effective precipitation utilisation coefficients based on rainfall characteristics and field-water conditions. This integrated framework provides new insights and a practical tool for irrigation scheduling and water-saving rice cultivation in East China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

The Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang Irrigation Experimental Stations are key sites within the irrigation experiment system of Zhejiang Province, East China. The Pinghu station (121°16′ E, 30°71′ N) has silty clay soil derived from marine sediments, with a bulk density of 1.3–1.4 g/cm3. The Jinqing station (121°51′ E, 28°51′ N) is characterized by tidal clay soils with a bulk density of 1.1–1.2 g/cm3. The Yongkang station (119°96′ E, 28°93′ N) is situated at an elevation of 85.4 m, with sandy clay soils and a bulk density of 1.4–1.5 g/cm3.

These three stations are representative of typical agricultural regions in East China: the Hangjiahu Plain (Pinghu), the coastal island zone of eastern Zhejiang (Jinqing), and the hilly low-mountain region of southeastern Zhejiang (Yongkang). Each station is equipped with instruments such as soil moisture sensors, field water level gauges, leaf area meters, chlorophyll meters, and soil solution samplers, enabling research on water-saving irrigation technologies for rice, water-saving and pollution-reduction practices, and irrigation regimes for crops.

2.2. Data Sources

Rainfall data during the rice-growing season (June–November) from 1986 to 2017 at the three irrigation stations (Pinghu, Jinqing and Yongkang) were obtained from routine meteorological observations at the experimental sites. Daily rainfall represents the accumulated precipitation from 08:00 to 08:00 of the following day. Before analysis, the long-term daily series were subjected to basic quality control. The records were checked for completeness and internal consistency, and obviously erroneous values (such as negative rainfall or isolated unrealistically large peaks inconsistent with neighbouring days) were removed. Years with substantial data gaps during the rice-growing season were excluded from the statistical analysis. Based on the cleaned daily series, the seasonal rainfall totals, monthly average rainfall and rainfall concentration indices were calculated for each station. For Pinghu station, effective precipitation during the rice-growing seasons of 2018–2020 was further analysed using field-measured data, including crop transpiration, deep percolation, irrigation depth and crop water requirement. In combination with the observed daily rainfall, these field data were used as inputs to the soil–water balance method [16] described in Section 2.3 to calculate daily effective precipitation in the root zone and the corresponding effective precipitation utilisation coefficient. The soil–water balance was evaluated at the field scale under the assumption that soil properties and management practices are spatially uniform within each experimental plot. This simplification is necessary because only plot-averaged data are available from the irrigation stations.

2.3. Methods

The three irrigation stations (Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang) were selected as representative sites to analyze the interannual spatial–temporal variations of rainfall, rainfall concentration index, and the long-term trend of mean monthly rainfall during the rice-growing season (June–November) from 1986 to 2017. The objective was to identify rainfall characteristics across different regions of Zhejiang Province in East China.

For Pinghu station, data from the rice-growing seasons of 2018, 2019, and 2020 were analyzed, including transpiration, deep percolation, and crop water requirements. Effective precipitation was estimated, and the effective precipitation utilization coefficient was calculated to explore the distribution and characteristics of effective precipitation at the representative site.

In the soil–water balance calculation, an effective root zone depth of 0.20 m was assumed uniformly for the Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang irrigation stations, representing the typical plough layer and main rooting zone of lowland rice in the study region.

2.3.1. Effective Precipitation

According to the handbook [17] and based on the soil–water balance equation, a real-time estimation method was applied. The formula is expressed as:

where is the effective rainfall or precipitation (mm), is the soil water storage on the second day after rainfall (mm), is the soil water storage before rainfall (mm), and is the field evapotranspiration during the rainfall period (mm), which can be estimated using the Penman–Monteith equation. Surface drainage and deep percolation losses are represented by the term in Equation (1). Due to limited field measurements, was estimated using empirical coefficients recommended in the regional irrigation guidelines [18].

2.3.2. Effective Precipitation Utilization Coefficient

The effective precipitation utilization coefficient is defined as the ratio of effective precipitation to total precipitation within a given period:

where is the effective precipitation utilization coefficient, is the effective precipitation (mm), and is the total precipitation (mm).

In this study, rainfall, effective precipitation and utilisation coefficients during the rice-growing season were first summarised using descriptive statistics (such as interannual means and ranges) before further analysis of their temporal variation and spatial differences among the three stations

2.4. Prediction with a Machine Learning Model

To further enhance the quantitative analysis of water utilization processes in paddy fields, this study introduces a machine learning approach to predict the effective precipitation utilization coefficient. In this study, an ε-insensitive support vector regression (SVR) model [19] with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel was employed to predict the effective precipitation utilisation coefficient. Given an input vector that contains daily rainfall, the 7-day antecedent precipitation index, the number of consecutive dry days and the extreme rainfall indicator, the SVR seeks a regression function

where is the RBF kernel, and are Lagrange multipliers, is the kernel width, is the regularisation parameter controlling the trade-off between model complexity and training error, and defines the width of the ε-insensitive loss function.

2.4.1. Input and Output

The selection of input variables was based on a comprehensive consideration of rainfall characteristics and field water conditions, including:

- (1)

- Daily rainfall , representing the precipitation on day ;

- (2)

- Antecedent wetness indicators, including the cumulative rainfall over the previous seven days and the number of consecutive dry days. The former was represented by the Antecedent Precipitation Index (API), calculated as follows [20]:

- (3)

- Extreme rainfall events, where precipitation exceeding a threshold (≥50 mm) was assigned a value of 1, otherwise 0.

The output variable was defined as daily effective precipitation (mm).

2.4.2. Model Construction and Parameter Optimization

During model training, the dataset was first randomly shuffled and then divided into a training set (75%), validation set (15%), and test set (15%). The Support Vector Regression (SVR) model with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel was adopted. The penalty parameter and kernel parameter were optimized using grid search.

2.4.3. Model Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the predictive performance, this study employed the root mean square error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination () as evaluation metrics.

where denotes the observed values, the predicted values, the mean of observed values, and the number of samples. RMSE reflects the magnitude of prediction errors, while measures the consistency between predicted and observed values.

Based on the available rainfall and field water condition data, the proposed approach enables the prediction of the effective precipitation utilization coefficient. Compared with traditional empirical models, the support vector regression (SVR) method is capable of capturing nonlinear relationships, making it more suitable for scenarios in which paddy water processes are influenced by multiple interacting factors. The prediction results can provide both data support and theoretical basis for irrigation scheduling optimization and water-saving rice cultivation.

3. Results

3.1. Rainfall Characteristics in Typical Regions

3.1.1. Interannual Rainfall Analysis

Rainfall data from the rice-growing season (June–November) during 1986–2017 at Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang stations were analyzed. Assuming spatial uniformity of rainfall within the representative regions, the temporal distribution and variability of rainfall at each station were examined.

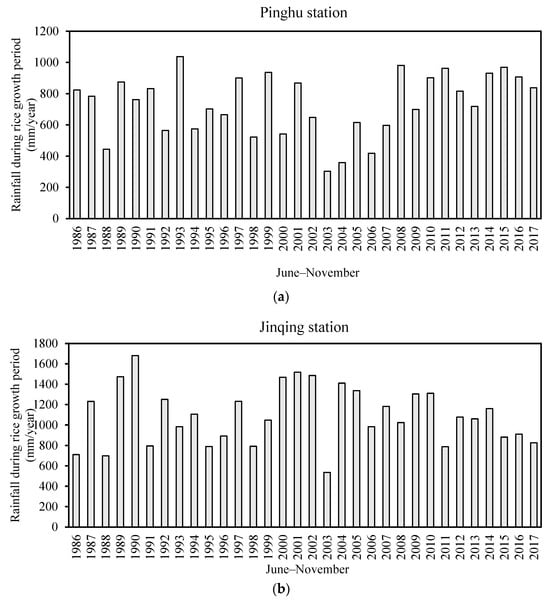

As shown in Figure 1, the average rainfall during the rice-growing season at Pinghu Station was 734 mm, ranging from 303 mm in 2003 to 1038 mm in 1993. At Jinqing Station, the average seasonal rainfall was 1092 mm, with a range of 536 mm (2003) to 1681 mm (1990). Yongkang Station recorded an average of 817 mm, with values ranging from 392 mm (2003) to 1304 mm (1989). Among the three sites, Jinqing Station exhibited the highest long-term average rainfall, followed by Yongkang, while Pinghu recorded the lowest. Notably, the minimum rainfall in all three stations occurred in 2003, consistent with the widespread summer–autumn drought reported in Zhejiang Province during that year.

Figure 1.

Statistical distribution of rainfall during the rice-growing season (June–November) from 1986 to 2017 for (a) Pinghu; (b) Jinqing; (c) Yongkang.

The ratios of maximum to minimum seasonal rainfall were 2.43, 2.14, and 2.33 at Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang stations, respectively, indicating substantial interannual variability in rainfall during the rice-growing season.

Based on the trend analysis of rainfall during the rice-growing season from 1986 to 2017, the regression slopes at Pinghu and Yongkang stations were 3.8 and 3.3, respectively, indicating upward trends. This suggests that rainfall during the rice-growing season at these two stations has gradually increased, with a high likelihood of continuous increases in the future. In contrast, Jinqing station exhibited a downward trend with a slope of −1.9, suggesting that seasonal rainfall has been decreasing over the same period, with a high probability of further reductions in the future.

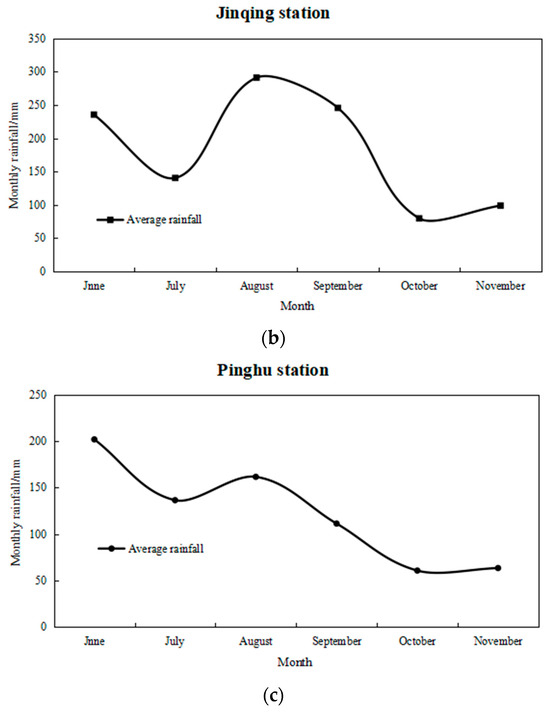

3.1.2. Rainfall Concentration During the Rice-Growing Season

Rainfall concentration reflects the proportion of rainfall occurring within a specific period relative to the annual total, thereby indicating the degree of temporal clustering. In this study, the rainfall concentration of the rice-growing season was defined as the ratio of rainfall from June to November to the total annual rainfall. Analyzing the proportion of seasonal rainfall to annual totals provides valuable insights into the extent to which rainfall influences rice water availability during the growing season.

The rainfall concentration index during the rice-growing season generally falls between 40% and 80% at the three stations (Figure 2), indicating that a considerable portion of the annual rainfall is received during the rice-growing period. Years with a concentration index exceeding 50% account for 25, 28 and 21 years at Pinghu, Jinqing and Yongkang, respectively, corresponding to more than 60% of the study period at each site. In these years, over half of the annual rainfall occurs during the rice-growing season, providing favourable hydrological conditions for rice growth and development.

Figure 2.

Statistical distribution of rainfall concentration during the rice-growing season (1986–2017) at the representative stations (Pinghu, Jinqing and Yongkang).

Extreme concentration can also occur. For example, in 2011 the rainfall concentration index reached 84.8% at Pinghu, 68.3% at Jinqing and 75.0% at Yongkang, implying that most of the annual rainfall was concentrated in the growing season. Such years are characterised by not only high seasonal rainfall but also relatively long and intense rainfall events, which may increase the risk of flooding and waterlogging. On the basis of these observations, a further analysis of the monthly rainfall distribution is needed to reveal how rainfall timing interacts with the critical stages of rice growth.

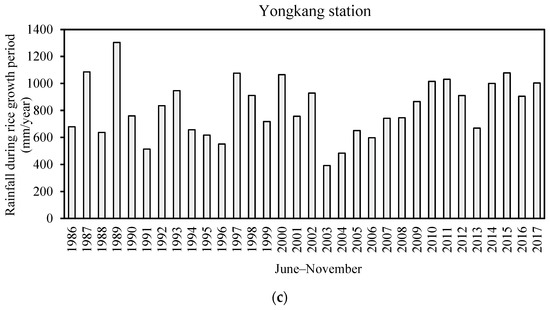

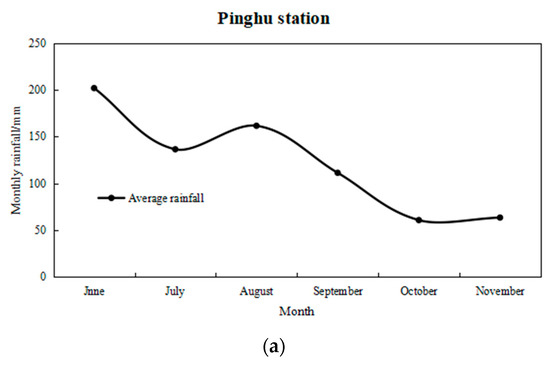

3.1.3. Monthly Rainfall During the Rice-Growing Season

The monthly average rainfall during the rice-growing season (June–November) from 1986 to 2017 was calculated for Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang stations, and corresponding trend and distribution plots were generated.

As shown in Figure 3, rainfall at Pinghu Station ranged from 61 mm in October to 202 mm in June. Rainfall from June to September accounted for 83% of the seasonal total, showing an overall decreasing trend, with a pronounced decline after August. At Jinqing Station, monthly rainfall ranged from 80 mm (October) to 291 mm (August). Rainfall from June to September accounted for 84% of the seasonal total, also displaying an overall decreasing trend with a sharp reduction after August. In addition, rainfall fluctuated between June and August, first decreasing and then increasing, followed by a marked decline from August to November. At Yongkang Station, rainfall ranged from 64 mm (October) to 268 mm (June). Rainfall from June to September accounted for 82% of the seasonal total, showing a pattern similar to Pinghu Station, with an overall downward trend and a sharp decline after August.

Figure 3.

Variation of average monthly rainfall during the rice-growing season (June–November) from 1986 to 2017 at the representative stations (a) Pinghu, (b) Jinqing and (c) Yongkang.

Overall, the rainfall at the three representative stations was predominantly concentrated between June and September, contributing more than 80% of the seasonal total. According to the rice irrigation schedule in East China, this period coincides with the critical growth stages of tillering, jointing–booting, and heading–flowering, during which rice is highly sensitive to water stress. Higher rainfall during these stages is therefore crucial for meeting water requirements and ensuring normal crop development. Furthermore, during the flood season, when individual rainfall events may be intense, effective utilization of rainfall—while avoiding waterlogging—should be considered, which has positive implications for water-saving irrigation in rice production.

3.2. Analysis Based on the Soil–Water Balance Method

3.2.1. Results of Effective Precipitation Calculation

In this study, the rainfall data from 2018 to 2020 at Pinghu Station were used to calculate effective precipitation using the soil–water balance equation. The effective precipitation utilization coefficient was defined as the ratio of effective precipitation to total precipitation.

As shown in Table 1, during the 2018 rice-growing season, there were 14 rainfall days with a total precipitation of 429.2 mm, of which 245.9 mm was classified as effective precipitation. The overall effective precipitation utilization coefficient for the season was 0.573. Among these events, there were four instances of consecutive rainfall lasting more than two days, with a total precipitation of 121.7 mm, effective precipitation of 88.4 mm, and an effective precipitation utilization coefficient of 0.726. The highest utilization was recorded on 12 August and 25 August, when the effective precipitation utilization coefficients both reached 1.000. By contrast, the lowest utilization occurred on 23 September, with a rainfall of 3.5 mm and effective precipitation of only 0.5 mm, corresponding to a coefficient of 0.143. This low value was attributed to consecutive rainfall events on 21–22 September, which reduced the subsequent effective utilization.

Table 1.

Effective precipitation and coefficients at Pinghu station in 2018.

In 2018, a total of 11 rainfall events exhibited an effective precipitation utilization coefficient greater than 0.5, accounting for 79% of the rainfall days during the growing season, which indicates relatively high utilization. However, the degree of effective precipitation utilization coefficients varied considerably throughout the season, with some events showing very high efficiency and others much lower. As a result, the overall effective precipitation utilization coefficient in 2018 was the lowest among the three representative years.

At Pinghu station in 2019, the calculated effective precipitation and corresponding coefficients are shown in Table 2. During the rice-growing season, there were 11 rainfall days with a cumulative precipitation of 451.0 mm, of which 290.4 mm was effective precipitation. The seasonal effective precipitation utilization coefficient reached 0.644. Within this period, three episodes of consecutive rainfall lasting more than two days were observed, with a total precipitation of 286.0 mm, effective precipitation of 199.5 mm, and a coefficient of 0.698. The highest daily utilization occurred on 10 August, when rainfall reached 75.0 mm, effective precipitation was 71.5 mm, and the coefficient rose to 0.953. In contrast, the lowest efficiency was recorded on 24 August, with only 1.0 mm of effective precipitation out of 4.5 mm of rainfall, corresponding to a coefficient of 0.222. Overall, eight rainfall days (73% of the total) had coefficients greater than 0.5, suggesting that rainfall in 2019 was effectively utilized at a relatively high level.

Table 2.

Effective precipitation and coefficients at Pinghu station in 2019.

According to Table 3, during the 2020 rice-growing season at Pinghu station, there were 14 rainfall days with a total precipitation of 581.5 mm, of which 444.3 mm was classified as effective precipitation. The overall effective precipitation utilization coefficient for the season was 0.764. Among these events, four episodes of consecutive rainfall lasting more than two days were observed, with a cumulative precipitation of 495.5 mm, effective precipitation of 390.7 mm, and an effective coefficient of 0.788.

Table 3.

Effective precipitation and coefficients at Pinghu station in 2020.

The highest daily utilization was recorded on 19 September, when rainfall reached 12.0 mm and was fully effective, yielding a coefficient of 1.000. In contrast, the lowest utilization occurred on 6 August, with 21.0 mm of rainfall but only 0.5 mm of effective precipitation, corresponding to a coefficient of 0.024. This exceptionally low value was attributed to a preceding extreme rainfall event on 5 August, when precipitation reached 316.5 mm and effective precipitation was 266.5 mm, thereby significantly reducing the effective utilization of the subsequent day’s rainfall.

Overall, eight rainfall days exhibited coefficients greater than 0.6, accounting for 57% of the total rainfall days during the season, suggesting that rainfall utilization efficiency in 2020 was relatively high.

3.2.2. Analysis of Effective Precipitation Utilization Coefficients

Daily rainfall events during the representative years 2018–2020 were ranked in descending order, and the corresponding distribution of rainfall and effective precipitation utilization coefficients is shown in Figure 4. When daily rainfall exceeded 30 mm, the utilization coefficient was generally above 0.67, indicating that nearly 70% of the rainfall was converted into effective precipitation in paddy fields. Exceptions occurred on 17 September 2018 (144 mm) and 5 August 2019 (54.5 mm), where the coefficients were only 0.257. These low values were mainly attributed to full irrigation applied prior to the rainfall events, which reduced the effective utilization of the subsequent precipitation.

Figure 4.

Distribution of daily rainfall and corresponding effective precipitation utilization coefficients at Pinghu station during 2018–2020.

When daily rainfall was less than 5 mm, four events recorded a coefficient of 1.000, while two events had coefficients of 0.900 and 0.800, respectively; all other cases remained above 0.5. This suggests that under such conditions, small rainfall events were effectively utilized by paddy fields. In contrast, when daily rainfall fell within the range of 5–30 mm, the utilization coefficient varied widely between 0.024 and 1.000, showing a highly scattered distribution. This indicates that in this range, the conversion of rainfall into effective precipitation was less consistent and likely influenced by additional field factors.

In summary, when rainfall is relatively high ( mm), the effective precipitation utilization coefficient is generally large, indicating a higher efficiency of rainfall use in paddy fields. Under conditions where waterlogging is prevented, such rainfall is beneficial for rice growth and development during critical stages such as tillering, jointing–booting, and heading–flowering. When rainfall is relatively low ( mm), the coefficient is also high, suggesting that rice paddies, as a water-intensive cropping system, possess a certain storage capacity that enables efficient retention and absorption of small rainfall events. This process contributes to regulating soil moisture conditions and supporting crop growth and development. By contrast, when rainfall is moderate (), the precipitation coefficient exhibits a highly scattered distribution. This implies that the effective use of rainfall in this range is more sensitive to additional factors, such as antecedent soil moisture, irrigation–drainage practices, and field engineering conditions, which require further investigation. It should be noted that the class boundaries P ≤ 5 mm, 5 mm < P < 30 mm, and P ≥ 30 mm were not taken from technical standards but were chosen empirically, after preliminary analysis indicated distinct patterns of effective precipitation utilization within these three rainfall ranges.

3.3. Analysis Based on Support Vector Regression

3.3.1. Model Evaluation

To further investigate the prediction of the effective precipitation utilization coefficient, this study selected daily rainfall data from the Pinghu station during 2018–2020, together with the corresponding effective precipitation data, as the modeling samples. Considering that extremely small or large outliers might lead to bias in model training, the raw data were subjected to screening and cleaning. Only representative samples that are physically meaningful and capable of accurately reflecting the dynamics of paddy field water conditions were retained to ensure the scientific validity and reliability of the modeling process.

Table 4 summarizes the processed dataset used for model construction, which includes daily rainfall (), the 7-day antecedent precipitation index (API), consecutive dry days (), extreme rainfall event indicator (), as well as the effective precipitation and the effective precipitation utilization coefficient () calculated based on the soil–water balance method. These variables together constitute the core inputs and outputs for machine learning modeling, providing the fundamental basis for model training, validation, and prediction.

Table 4.

Modeling data at Pinghu station from 2018 to 2020.

In terms of data partitioning, 10% of the overall dataset was first set aside as a validation set to evaluate the model’s generalization capability on unseen data. The remaining 90% of the samples were further divided into training and testing sets in a 7:3 ratio, ensuring a balance between parameter optimization and performance evaluation. This design allowed the model to fully learn data characteristics during training while enabling independent validation of its prediction stability and practical applicability.

3.3.2. Prediction Results of the Effective Precipitation Utilization Coefficient

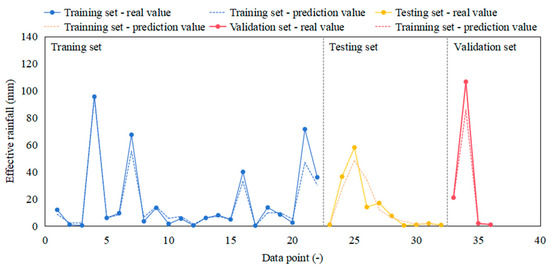

The results indicate that the optimal parameters were obtained as and . On the testing dataset, the coefficient of determination reached , and the root mean square error (RMSE) was 4.584 mm. These results demonstrate that the predicted values are highly consistent with the observed values, suggesting that the SVR model can effectively capture the nonlinear relationship between rainfall characteristics and the effective precipitation coefficient. Because the field-measured data required for the soil–water balance (including crop transpiration, deep percolation, irrigation depth and drainage) were only available at Pinghu station during 2018–2020, the SVR model was developed and validated exclusively for this station, which is taken as a representative irrigated paddy area in East China.

Figure 5 presents the comparison between predicted and observed values in the form of line plots. The overall trends show a high degree of agreement, indicating that the model can accurately reflect the variation of the effective precipitation utilization coefficient under different rainfall events. For most samples, the prediction errors are relatively small, and the discrepancies between observed and predicted values remain within a reasonable range, which demonstrates the strong fitting capability of the SVR model.

Figure 5.

Comparison between observed and SVR-predicted effective precipitation at Pinghu Station during 2018–2020.

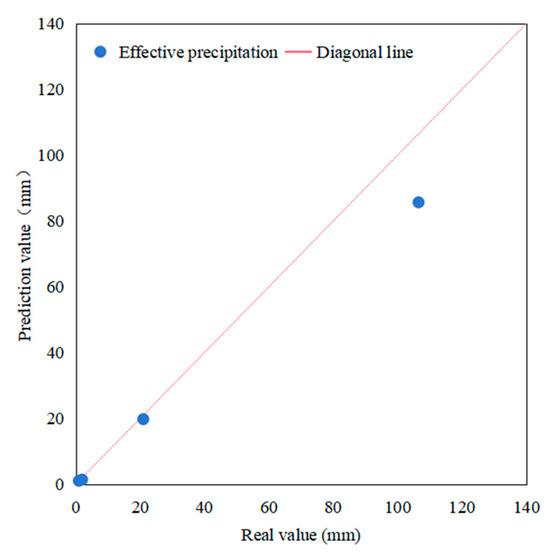

The scatter comparison (Figure 6) shows that the predicted and observed values exhibit good overall agreement in the low-value range (effective precipitation ≤ 20 mm), with most points distributed near the 1:1 reference line, indicating that the model provides reliable predictions under light and moderate rainfall conditions. However, in the high-value range (>80 mm), the model demonstrates a clear underestimation, with predicted values significantly lower than the observed ones. This suggests that the SVR model has limited fitting capability under extreme rainfall events, which may be attributed to the scarcity of high-value samples in the training set and the insufficient representation of threshold processes by the input features. Consequently, the extrapolation capability of the SVR model under extreme rainfall conditions remains limited and should be improved in future work by extending the time series and enriching the predictor variables. Overall, the model performs with satisfactory stability and accuracy in the low-value range, but prediction bias emerges in the high-value range, implying that further optimization is required through sample augmentation or improvements in the modeling approach.

Figure 6.

Scatter plot comparing observed and predicted effective precipitation utilization coefficients.

3.4. Discussion

The results reveal pronounced interannual variability in rainfall at Pinghu, Jinqing, and Yongkang, with Pinghu showing the lowest and Jinqing the highest seasonal totals. Similar spatial contrasts and strong year-to-year fluctuations in rice-growing rainfall have been reported for East-China paddy regions, where such variability is a key driver of irrigation demand and soil–water balance [21]. The relatively high rainfall concentration indices at Jinqing and Yongkang indicate that a large share of seasonal rainfall is delivered by a limited number of events, consistent with studies noting increasing precipitation concentration and its implications for waterlogging and flood risk in Asian rice systems [22,23,24].

The monthly patterns show an early-season rainfall peak at Pinghu and a more uniform distribution at Jinqing, underscoring intra-regional differences in rainfall timing that may require station-specific irrigation scheduling and field-management strategies. This spatial heterogeneity agrees with previous work highlighting that even within a single climatic region, local rainfall regimes can diverge sufficiently to justify differentiated water-saving measures in rice production [24,25].

The SVR model reproduces effective precipitation utilization coefficients well under light and moderate rainfall, in line with earlier applications of machine-learning models for hydro-meteorological prediction in agriculture [26,27,28]. Underestimation in the high-rainfall range reflects a common limitation of data-driven approaches, which often struggle to extrapolate to rare extremes that are under-represented in the training set [27,28]. Enlarging the sample to include more extreme events and enriching the predictor set with additional climatic and soil–water indicators should enhance robustness, while the current performance already demonstrates the potential of SVR as a practical tool to support water-saving irrigation scheduling in paddy fields.

4. Conclusions

This study analyzes the rainfall characteristics and effective precipitation utilization in the rice-growing season at three representative stations in East China. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The mean seasonal rainfall during 1986–2017 show significant interannual variability among the three stations of interest. The historical data suggests that more than 60% of the rainfall occurs during the rice-growing season, providing favorable water availability for rice production.

- (2)

- Over 80% of the rainfall occurred from June to September at all stations, which coincides with critical growing stages. This highlights the importance of early-season rainfall in supporting crop water requirements.

- (3)

- At Pinghu, between 2018 and 2020, effective precipitation accounted for 57% to 76% of the seasonal rainfall, demonstrating that effective precipitation is a crucial water source for paddy fields under the study conditions.

- (4)

- The effective precipitation utilization coefficient showed non-linear responses to rainfall magnitude. High coefficients were observed for both heavy rainfall events and small showers, suggesting efficient water use, whereas moderate rainfall showed more variability, influenced by soil moisture and field management practices.

- (5)

- The SVR model generally well predicts the effective precipitation utilization coefficient. It can be an alternative approach for prediction of effective precipitation utilization, which could be helpful to optimize irrigation schedules based on forecasted rainfall. However, the model underestimates high-value cases due to limited extreme event samples. Further improvements could be made by expanding the dataset and enhancing the predictor variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F., Z.W. and M.H.; methodology, X.F. and Q.L.; software, Q.L.; validation, H.F., M.H. and Q.L.; formal analysis, H.F. and X.F.; investigation, H.F. and Q.L.; resources, Z.W. and M.H.; data curation, H.F.; writing—original draft preparation, H.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.W., M.H., X.F. and Q.L.; visualization, M.H. and Q.L.; supervision, X.F. and Q.L.; project administration, M.H. and X.F.; funding acquisition, X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB3711500) and the APC was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB3711500).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhan Weng and Miao Hu were employed by Zhejiang Guangchuan Engineering Consulting Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, S.; Rasool, G.; Guo, X.; Sen, L.; Cao, K. Effects of different irrigation methods on environmental factors, rice production, and water use efficiency. Water 2020, 12, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Tong, W.; Li, H.; Li, K.; Xu, W.; Liang, B. Temporal variations in rice water requirements and the impact of effective rainfall on irrigation demand: Strategies for sustainable rice cultivation. Water 2025, 17, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, A.H.; Murty, V.V.N.; Phien, H.N. Modeling irrigation schedules for lowland rice with stochastic rainfall. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 1992, 118, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Tan, J.; Cui, Y.; Luo, Y. Irrigation scheduling of paddy rice using short-term weather forecast data. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Tuong, T.P. Field water management to save water and increase its productivity in irrigated lowland rice. Agric. Water Manag. 2001, 49, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D. Deficit irrigation as an on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Cordery, I.; Iacovides, I. Improved indicators of water use performance and productivity for sustainable water conservation and saving. Agric. Water Manag. 2012, 108, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Bian, D.; Du, X.; Pushpa, R.; Cui, Y. Spatio-temporal distribution characteristics of precipitation, water demand, and drought during the summer maize growth period in the Heilonggang Basin. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 124–133, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Mo, M. Variation characteristics of effective precipitation and water requirement of cassava in Guangxi from 1958 to 2015. Water Sav. Irrig. 2020, 80–87, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Pei, X.; Cao, H.; Gu, S.; Mo, J. Characteristics of water requirement and irrigation demand index for flue-cured tobacco in Guizhou Province. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2019, 26, 215–221, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Pang, Y.; Pan, X. Variation characteristics of water surplus and deficit of single-season rice in Sichuan Province under climate change. J. Nat. Resour. 2014, 29, 1508–1519, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Chen, L.; Sun, C.; Zheng, Z.; Li, X. Spatial distribution pattern of water requirement for main crops in the eastern Loess Plateau. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 27, 166–176, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Dehghanisanij, H.; Emami, S.; Khasheisiuki, A. Functional properties of irrigated cotton under urban treated wastewater using an intelligent method. Appl. Water Sci. 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, H.; Emami, S.; Parsa, J. A Walnut optimization algorithm applied to discharge coefficient prediction on labyrinth weirs. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 12197–12215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achite, M.; Emami, S.; Jehanzaib, M.; Katipoğlu, O.M.; Emami, H. An election algorithm combined with support vector regression for estimating hydrological drought. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hu, X.; Jiang, X.; Wang, W. Simulation and analysis of soil moisture at different growth stages of paddy fields based on HYDRUS. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2022, 40, 729–736, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Water Resources, Department of Rural Water Resources. Practical Manual of Water-Saving Irrigation Engineering; China Water Power Press: Beijing, China, 2005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Linsley, R.K.; Kohler, M.R. Predicting the runoff from storm rainfall. US Weather Res. Pap. 1951, 30. Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0819/ML081900279.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration—Guidelines for computing crop water requirements—FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO Rome 1998, 300, D05109. [Google Scholar]

- Pisner, D.A.; Schnyer, D.M. Support vector machine. In Machine Learning; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, Z. Climate change, high-temperature stress, rice productivity, and water use in Eastern China: A new superensemble-based probabilistic projection. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.K.; Manivasagam, V.S.; Nikoo, M.R.; Saravanane, P.; Narayanan, A.; Manalil, S. Rainfall variability and rice sustainability: An evaluation study of two distinct rice-growing ecosystems. Land 2022, 11, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Wang, W.; Kunkel, K.E.; Shao, Q.; Xing, W.; Wei, J. Heterogeneous response of global precipitation concentration to global warming. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, E2347–E2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Influence of Spring Water Residence Time on the Irrigation Water Stability in the Hani Rice Terraces. Water 2024, 16, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belder, P.; Bouman, B.A.M.; Spiertz, J.H.J. Exploring options for water savings in lowland rice using a modelling approach. Agric. Syst. 2007, 92, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E.M.P.; Wickramasinghe, L.C.D.; Weliwatta, R.T. Use of regression techniques for rice yield estimation in the North-Western province of Sri Lanka. Ceylon J. Sci. 2021, 50, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Tazwar, M.T.; Khan, H.; Roy, S.; Iqbal, J.; Rabiul Alam, M.G.; Hassan, M.M. Yield Response of Different Rice Ecotypes to Meteorological, Agro-Chemical, and Soil Physiographic Factors for Interpretable Precision Agriculture Using Extreme Gradient Boosting and Support Vector Regression. Complexity 2022, 2022, 5305353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hafyani, M.; El Himdi, K.; El Adlouni, S.E. Improving monthly precipitation prediction accuracy using machine learning models: A multi-view stacking learning technique. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1378598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).