Integrating UAV-LiDAR and Field Experiments to Survey Soil Erosion Drivers in Citrus Orchards Using an Exploratory Machine Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

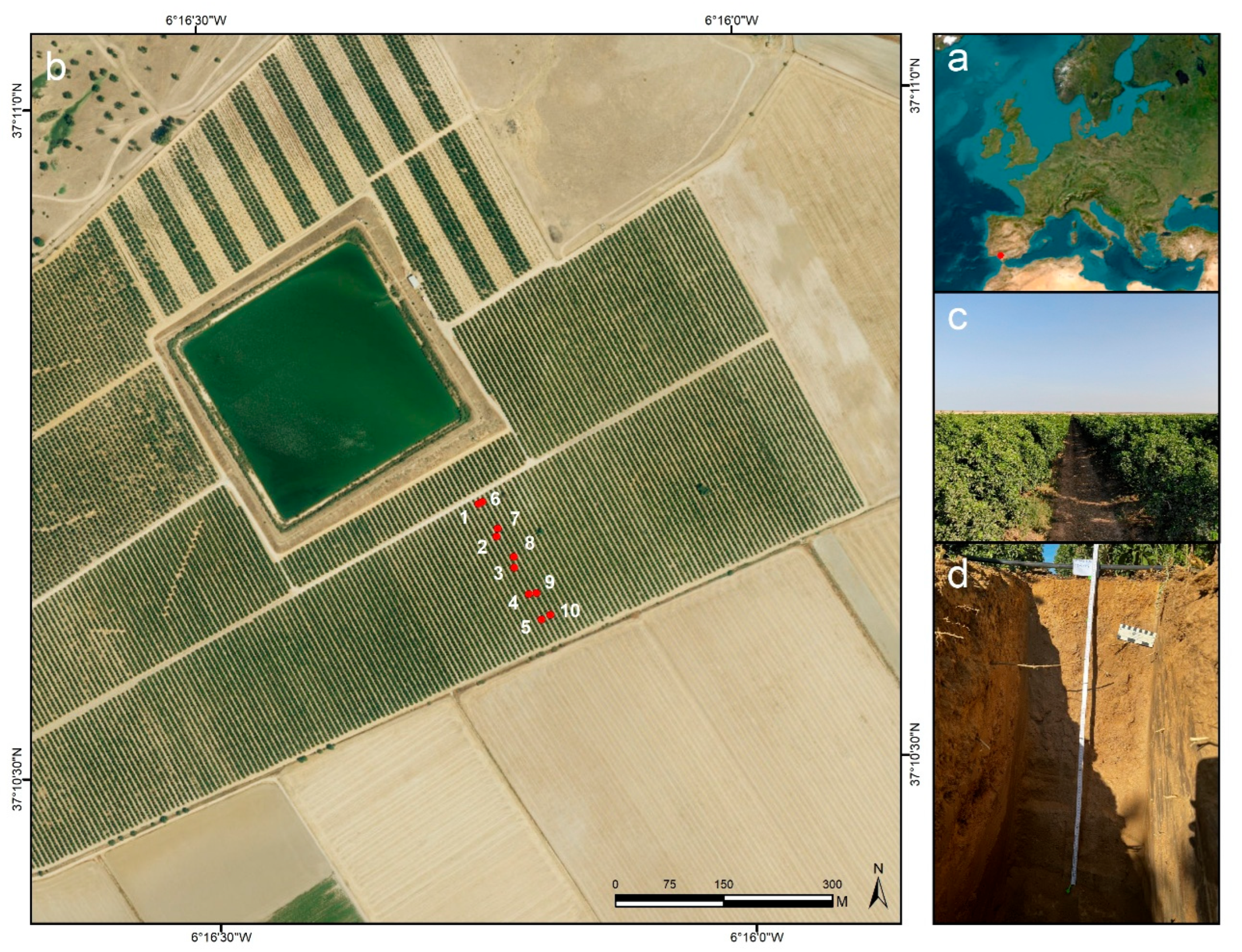

2.1. Study Area Description

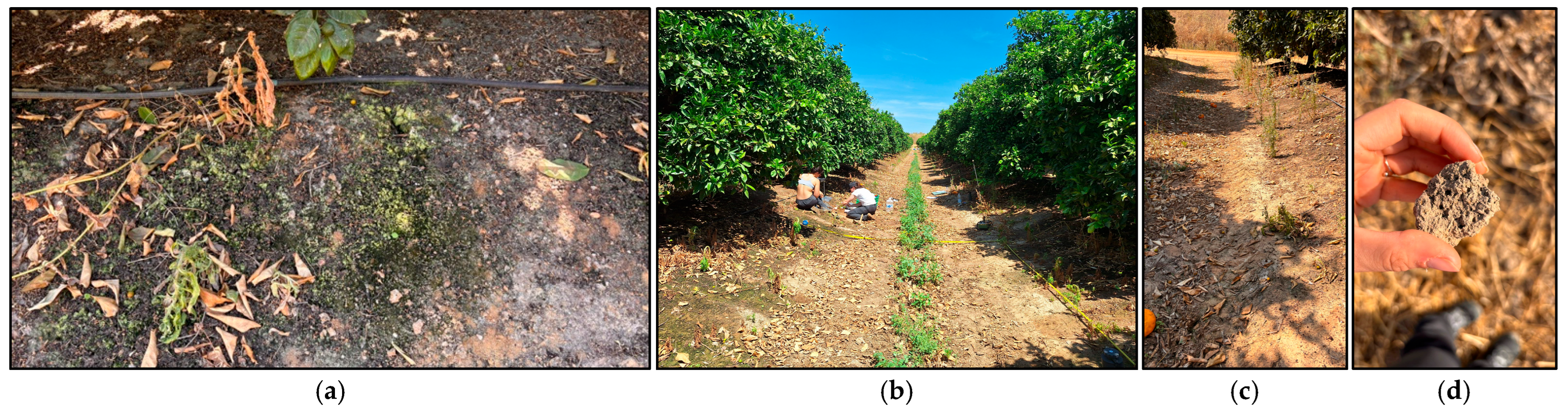

2.2. UAV-Based Photogrammetry, Field Experiments and Laboratory Analysis

2.2.1. UAV Survey and LiDAR Data Acquisition Workflow

2.2.2. Rainfall Simulation Experiments

2.2.3. Infiltration and Permeability Experiments

2.2.4. Soil Compaction and CO2

2.3. Dataset Description, Preprocessing, Analysis and Model Construction

2.3.1. Correlation Analysis and Exploratory Visualization

2.3.2. Model Construction

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the In-Situ Experiments and Measurements, and UAV-Survey

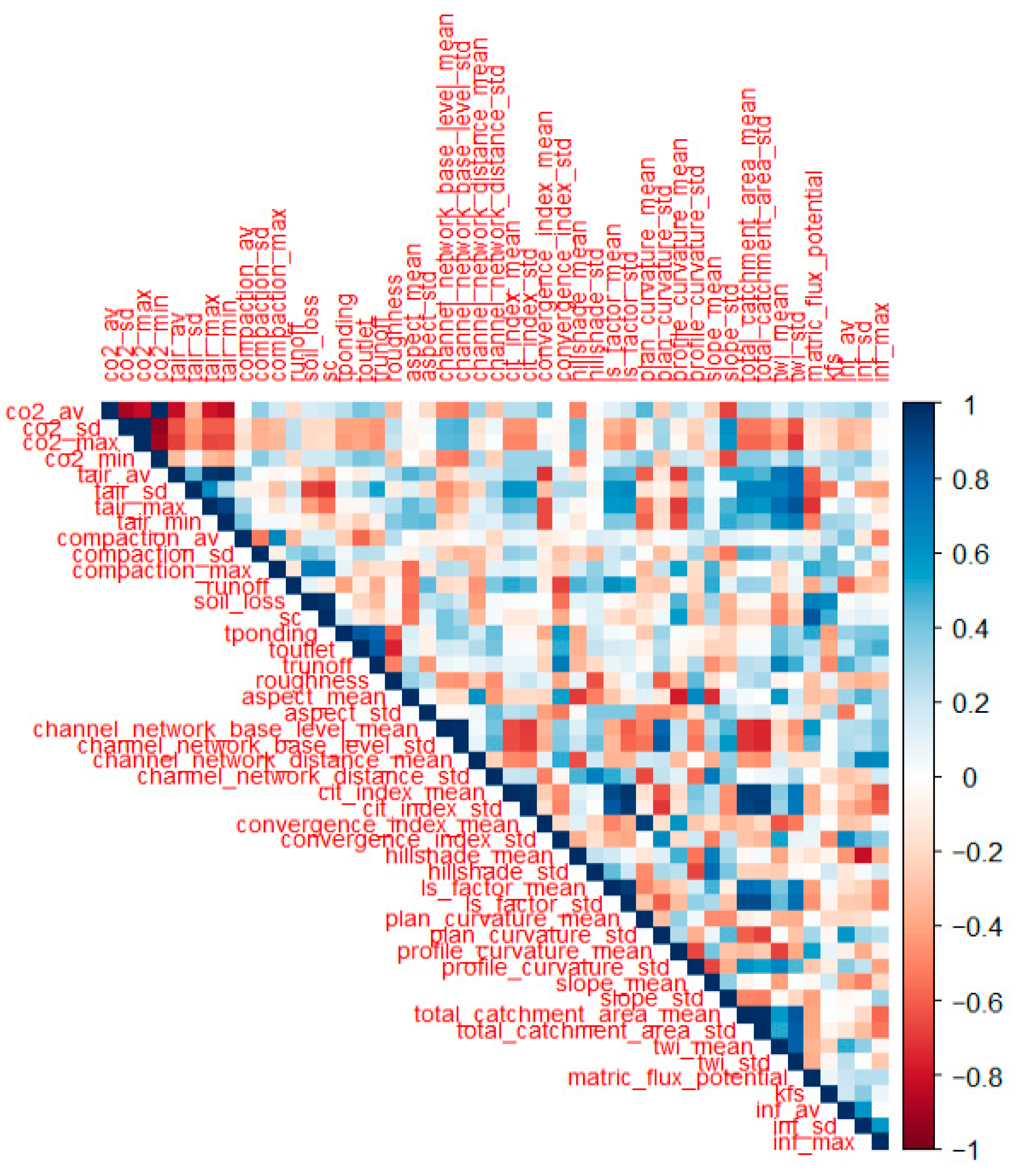

3.2. Correlation Matrix to Define Key Related Hydro-Pedological Variables

3.3. Prediction of Key Hydro-Pedological Variables and Processes

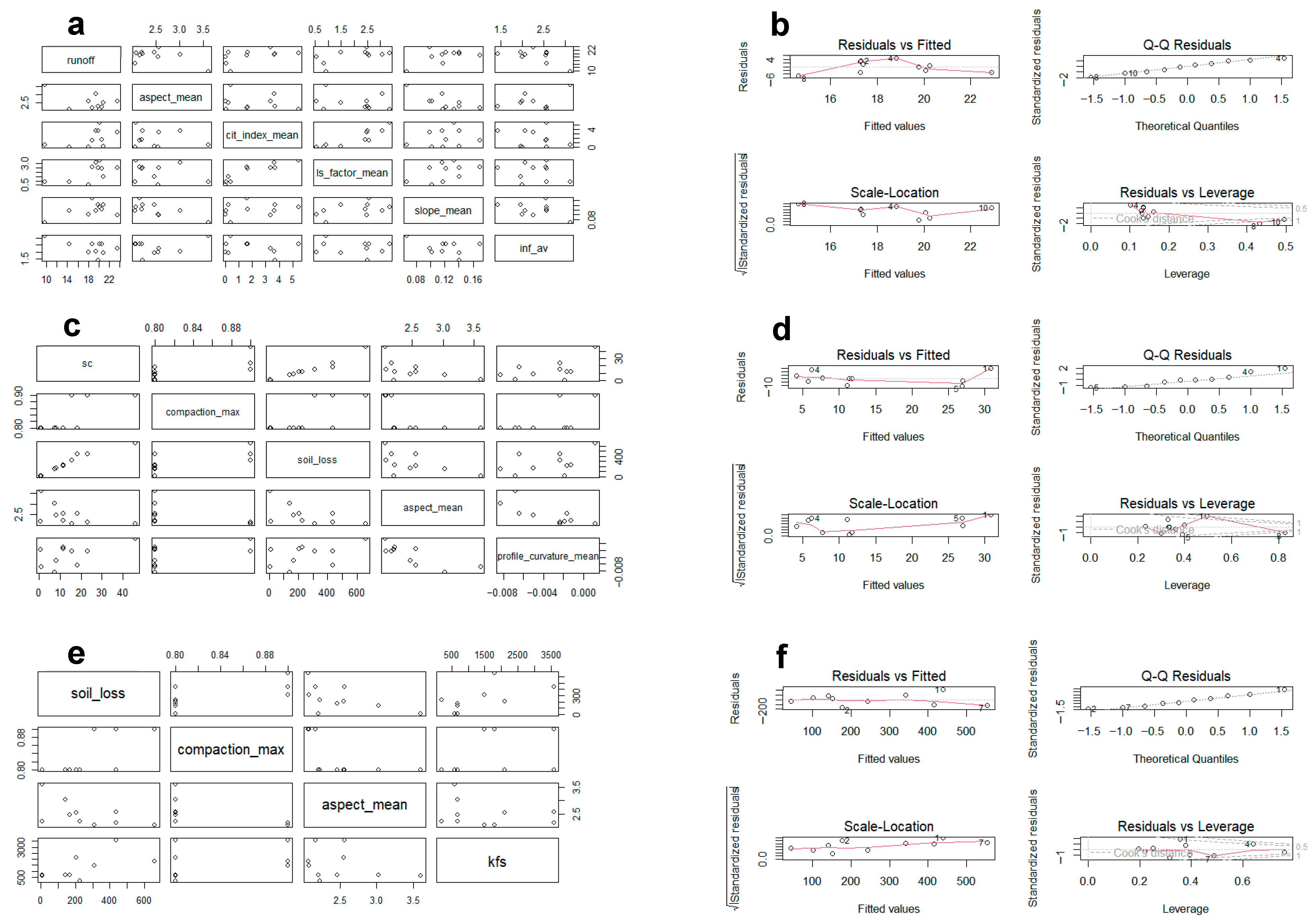

3.3.1. Runoff

3.3.2. Sediment Concentration

3.3.3. Soil Loss

3.4. Challenges and Main Weaknesses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seeger, M. (Ed.) Understanding and Preventing Soil Erosion; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-003-58788-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; De Geeter, S.; Poesen, J.; Matthews, F.; Campforts, B.; Borrelli, P.; Panagos, P.; Vanmaercke, M. Global Patterns of Gully Occurrence and Their Sensitivity to Environmental Changes. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, S.; Keesstra, S.; Maas, G.; de Cleen, M.; Molenaar, C. Soil as a Basis to Create Enabling Conditions for Transitions Towards Sustainable Land Management as a Key to Achieve the SDGs by 2030. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaullah, M.; Usman, M.; Wakeel, A.; Cheema, S.A.; Ashraf, I.; Farooq, M. Terrestrial Ecosystem Functioning Affected by Agricultural Management Systems: A Review. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 196, 104464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliaume, F.; Rossing, W.A.H.; Tittonell, P.; Jorge, G.; Dogliotti, S. Reduced Tillage and Cover Crops Improve Water Capture and Reduce Erosion of Fine Textured Soils in Raised Bed Tomato Systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 183, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalí, J.; Gastesi, R.; Álvarez-Mozos, J.; De Santisteban, L.M.; de Lersundi, J.D.V.; Giménez, R.; Larrañaga, A.; Goñi, M.; Agirre, U.; Campo, M.A.; et al. Runoff, Erosion, and Water Quality of Agricultural Watersheds in Central Navarre (Spain). Agric. Water Manag. 2008, 95, 1111–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Merritt, W.S.; Croke, B.F.W.; Weber, T.R.; Jakeman, A.J. A Review of Catchment-Scale Water Quality and Erosion Models and a Synthesis of Future Prospects. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 114, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesstra, S.; Nunes, J.; Novara, A.; Finger, D.; Avelar, D.; Kalantari, Z.; Cerdà, A. The Superior Effect of Nature Based Solutions in Land Management for Enhancing Ecosystem Services. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo, J.; Díaz-Pereira, E.; de Vente, J. Eco-Holistic Soil Conservation to Support Land Degradation Neutrality and the Sustainable Development Goals. Catena 2021, 196, 104823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdan, O.; Govers, G.; Le Bissonnais, Y.; Van Oost, K.; Poesen, J.; Saby, N.; Gobin, A.; Vacca, A.; Quinton, J.; Auerswald, K.; et al. Rates and Spatial Variations of Soil Erosion in Europe: A Study Based on Erosion Plot Data. Geomorphology 2010, 122, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, J.M.; Beguería, S.; Nadal-Romero, E.; González-Hidalgo, J.C.; Lana-Renault, N.; Sanjuán, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Soil Erosion Rates across the World. Geomorphology 2015, 239, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P.; Meusburger, K.; Alewell, C.; Lugato, E.; Montanarella, L. Estimating the Soil Erosion Cover-Management Factor at the European Scale. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Giménez-Morera, A.; Novara, A.; Pulido, M.; Kapović-Solomun, M.; Keesstra, S.D. Policies Can Help to Apply Successful Strategies to Control Soil and Water Losses. The Case of Chipped Pruned Branches (CPB) in Mediterranean Citrus Plantations. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liu, Y.-J.; Yang, J.; Tang, C.-J.; Shi, Z.-H. Role of Groundcover Management in Controlling Soil Erosion under Extreme Rainfall in Citrus Orchards of Southern China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 582, 124290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianjun, W.; Quansheng, L.; Lijiao, Y. Effect of intercropping on soil erosion in young citrus plantation—A simulation study. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 8, 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, F.; Monfared, A.B.; Jahansooz, M.R.; Esparza, E.T.; Keshavarzi, A.; Morera, A.G.; Fernández, M.P.; Cerdà, A. Analyzing Long-Term Soil Erosion in a Ridge-Shaped Persimmon Plantation in Eastern Spain by Means of ISUM Measurements. Catena 2019, 183, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anache, J.A.A.; Wendland, E.C.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Flanagan, D.C.; Nearing, M.A. Runoff and Soil Erosion Plot-Scale Studies under Natural Rainfall: A Meta-Analysis of the Brazilian Experience. Catena 2017, 152, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernoux, M.; Cerri, C.C.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Neto, M.S.; Metay, A.; Perrin, A.-S.; Scopel, E.; Tantely, R.; Blavet, D.; de Piccolo, M.C.; et al. Cropping Systems, Carbon Sequestration and Erosion in Brazil: A Review. In Sustainable Agriculture; Lichtfouse, E., Navarrete, M., Debaeke, P., Véronique, S., Alberola, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 75–85. ISBN 978-90-481-2665-1. [Google Scholar]

- Di Prima, S.; Bagarello, V.; Lassabatere, L.; Angulo-Jaramillo, R.; Bautista, I.; Burguet, M.; Cerdà, A.; Iovino, M.; Prosdocimi, M. Comparing Beerkan Infiltration Tests with Rainfall Simulation Experiments for Hydraulic Characterization of a Sandy-Loam Soil. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 3520–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserloh, T.; Ries, J.B.; Arnáez, J.; Boix-Fayos, C.; Butzen, V.; Cerdà, A.; Echeverría, M.T.; Fernández-Gálvez, J.; Fister, W.; Geißler, C.; et al. European Small Portable Rainfall Simulators: A Comparison of Rainfall Characteristics. Catena 2013, 110, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, D.K.; Yadav, D.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Bhat, S.A.; Mirzania, E.; Kuriqi, A. Assessing the Performance of Various Infiltration Models to Improve Water Management Practices. Paddy Water Environ. 2025, 23, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogunovic, I.; Telak, L.J.; Pereira, P. Experimental Comparison of Runoff Generation and Initial Soil Erosion Between Vineyards and Croplands of Eastern Croatia: A Case Study. Air Soil Water Res. 2020, 13, 1178622120928323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telak, L.J.; Dugan, I.; Bogunovic, I. Soil Management and Slope Impacts on Soil Properties, Hydrological Response, and Erosion in Hazelnut Orchard. Soil Syst. 2021, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, A.; Frangi, P.; Mori, J.; Donzelli, D.; Ferrini, F. Nature Based Solutions to Mitigate Soil Sealing in Urban Areas: Results from a 4-Year Study Comparing Permeable, Porous, and Impermeable Pavements. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.O.; Keesstra, S.D.; Słowik-Opoka, E.; Klamerus-Iwan, A.; Liaqat, W. Determining the Role of Urban Greenery in Soil Hydrology: A Bibliometric Analysis of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Ecosystem. Water 2025, 17, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayen, A.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Saha, S.; Keesstra, S.; Bai, S. Gully Erosion Susceptibility Assessment and Management of Hazard-Prone Areas in India Using Different Machine Learning Algorithms. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, S.; Efthimiou, N.; Karamesouti, M.; Papanikolaou, I.; Psomiadis, E.; Charizopoulos, N. Measuring Annual Sedimentation through High Accuracy UAV-Photogrammetry Data and Comparison with RUSLE and PESERA Erosion Models. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Gutiérrez, Á.; Schnabel, S.; Lavado Contador, F.; De Sanjosé, J.J.; Atkinson Gordo, A.; Pulido Fernández, M.; Sánchez Fernández, M. Studying the Influence of Livestock Pressure on Gully Erosion in Rangelands of SW Spain by Means of the Uav+sfm Workflow. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2018, 78, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS-WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Crema, S.; Cavalli, M. SedInConnect: A Stand-Alone, Free and Open Source Tool for the Assessment of Sediment Connectivity. Comput. Geosci. 2018, 111, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, J.B.; Iserloh, T.; Seeger, M.; Gabriels, D. Rainfall Simulations—Constraints, Needs and Challenges for a Future Use in Soil Erosion Research. Z. Geomorphol. 2013, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Caruso, R.; Ferro, V.; Serio, M.A. Characterizing the Kamphorst Rainfall Simulator for Soil Erosion Investigations. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 132025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavčová, K.; Danáčová, M.; Kohnová, S.; Szolgay, J.; Valent, P.; Výleta, R. Estimating the Effectiveness of Crop Management on Reducing Flood Risk and Sediment Transport on Hilly Agricultural Land—A Myjava Case Study, Slovakia. Catena 2019, 172, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserloh, T.; Fister, W.; Seeger, M.; Willger, H.; Ries, J.B. A Small Portable Rainfall Simulator for Reproducible Experiments on Soil Erosion. Soil Tillage Res. 2012, 124, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A. The Influence of Aspect and Vegetation on Seasonal Changes in Erosion under Rainfall Simulation on a Clay Soil in Spain. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1998, 78, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Jurgensen, M.F. Ant Mounds as a Source of Sediment on Citrus Orchard Plantations in Eastern Spain. A Three-Scale Rainfall Simulation Approach. Catena 2011, 85, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A. Soil Roughness Measurement: Chain Method. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1993, 48, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.P.; Cambronero, L.; Alcarria Salas, M.; Rodríguez, J.L.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Keesstra, S.D.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Conducting an in Situ Evaluation of Erodibility in a Mediterranean Semi-Arid and Conventional Vineyard in Granada Province (Southern Spain) through Rainfall Simulation Experiments. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2024, 9, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Bogunovic, I.; Mohajerani, H.; Pereira, P.; Cerdà, A.; Ruiz-Sinoga, J.; Ries, J. The Impact of Vineyard Abandonment on Soil Properties and Hydrological Processes. Vadose Zone J. 2017, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbágy, J.; Krištof, K.; Angelovič, M.; Zsembeli, J. Evaluation of Soil Infiltration Variability in Compacted and Uncompacted Soil Using Two Devices. Water 2023, 15, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.P.; Pekkat, S. Time Dependence of Hydraulic Parameters Estimation from Transient Analysis of Mini Disc Infiltrometer Measurements. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, W.D. The Guelph Permeameter Method for in Situ Measurement of Field-Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity and Matric Flux Potential. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo, A.M.; Mirzaei, M.; Wu, G.-L.; Keshavarzi, A.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Bernardo, F.S.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Evaluating Soil Respiration and Water Infiltration in Esparto Grasslands: The Effects of Hillslope Position and Soil Management in Arid, Human-Affected Mediterranean Environments. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madalina, V.; Valentina, C.; Natalia, E.; Lucian, L.; Monica, M.; Anda, R.; Norbert, B.; Madalina, B.; Silvius, S.; György, D. Experimental Determination of Carbon Dioxide Flux in Soil and Correlation with Dependent Parameters. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 616, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.; Colombi, T.; Ruiz, S.; Schymanski, S.J.; Weisskopf, P.; Koestel, J.; Sommer, M.; Stadelmann, V.; Breitenstein, D.; Kirchgessner, N.; et al. Soil Structure Recovery Following Compaction: Short-Term Evolution of Soil Physical Properties in a Loamy Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2021, 85, 1002–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemis, C.; Abrougui, K.; Mohammadi, A.; Gabsi, K.; Dorbolo, S.; Mercatoris, B.; Mutuku, E.; Cornelis, W.; Chehaibi, S. Development of Artificial Neural Networks to Predict the Effect of Tractor Speed on Soil Compaction Using Penetrologger Test Results. Processes 2022, 10, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, M.; Schnabel, S.; Lavado Contador, J.F.; Lozano-Parra, J.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, Á.; Brevik, E.C.; Cerdà, A. Reduction of the Frequency of Herbaceous Roots as an Effect of Soil Compaction Induced by Heavy Grazing in Rangelands of SW Spain. Catena 2017, 158, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A Review of Methods to Deal with It and a Simulation Study Evaluating Their Performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.; Poga, M. Dealing with Multicollinearity in Factor Analysis: The Problem, Detections, and Solutions. Open J. Stat. 2023, 13, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Prima, S.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Novara, A.; Iovino, M.; Pirastru, M.; Keesstra, S.D.; Cerdà, A. Soil Physical Quality of Citrus Orchards Under Tillage, Herbicide, and Organic Managements. Pedosphere 2018, 28, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basche, A.D.; DeLonge, M.S. Comparing Infiltration Rates in Soils Managed with Conventional and Alternative Farming Methods: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagdale, S.; Nimbalkar, P. Infiltration Studies of Different Soils under Different Soil Conditions and Comparison of Infiltration Models with Field Data. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2012, 3, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Taguas, E.; Seeger, M.; Ries, J.B. Quantification of Soil and Water Losses in an Extensive Olive Orchard Catchment in Southern Spain. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Ruiz Sinoga, J.D.; Senciales González, J.M.; Guerra-Merchán, A.; Seeger, M.; Ries, J.B. High Variability of Soil Erosion and Hydrological Processes in Mediterranean Hillslope Vineyards (Montes de Málaga, Spain). Catena 2016, 145, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Rasoulzadeh, A.; Mobaser, J.A.; Ahmadabad, Y.H.; Pollacco, J.A.P.; Fernández-Gálvez, J. Hydro-Pedotransfer Functions to Estimate Evaporation from Bare Soil Surface in Semi-Arid Regions. Air Soil Water Res. 2025, 18, 11786221251349047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Jaramillo, R.; Bagarello, V.; Iovino, M.; Lassabatere, L. Infiltration Measurements for Soil Hydraulic Characterization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-31788-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdà, A.; González-Pelayo, Ó.; Giménez-Morera, A.; Jordán, A.; Pereira, P.; Novara, A.; Brevik, E.C.; Prosdocimi, M.; Mahmoodabadi, M.; Keesstra, S. Use of Barley Straw Residues to Avoid High Erosion and Runoff Rates on Persimmon Plantations in Eastern Spain under Low Frequency–High Magnitude Simulated Rainfall Events. Soil Res. 2016, 54, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesstra, S.; Pereira, P.; Novara, A.; Brevik, E.C.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Parras-Alcántara, L.; Jordán, A.; Cerdà, A. Effects of Soil Management Techniques on Soil Water Erosion in Apricot Orchards. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Ackermann, O.; Terol, E.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Impact of Farmland Abandonment on Water Resources and Soil Conservation in Citrus Plantations in Eastern Spain. Water 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, J.L.M.P.; Carvalho, S.C.P.; de Lima, M.I.P. Rainfall Simulator Experiments on the Importance o of When Rainfall Burst Occurs during Storm Events on Runoff and Soil Loss. Z. Geomorphol. 2013, 57, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, M. Uncertainty of Factors Determining Runoff and Erosion Processes as Quantified by Rainfall Simulations. Catena 2007, 71, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiener, P.; Dlugoß, V.; Korres, W.; Schneider, K. Spatial Variability of Soil Respiration in a Small Agricultural Watershed—Are Patterns of Soil Redistribution Important? Catena 2012, 94, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, T.B.; Doran, J.W. Field and Laboratory Tests of Soil Respiration. In Methods for Assessing Soil Quality; Doran, J.W., Jones, A.J., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America Incorporated: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; Volume SSSA Special Publication 49, pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Bogunović, I.; Kisić, I.; Maletić, E.; Perčin, A.; Matošić, S.; Roškar, L. Soil Compaction in Vineyards of Different Ages in Pannonian Croatia. Part I. Influence of Machinery Traffic and Soil Management on Compaction of Individual Horizons. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2016, 17, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttmann, R.; Schwanebeck, M.; Nolde, M.; Horn, R. Predicting Soil Compaction Risks Related to Field Traffic during Silage Maize Harvest. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, C.C.; Nemergut, D.R.; Schmidt, S.K.; Townsend, A.R. Increases in Soil Respiration Following Labile Carbon Additions Linked to Rapid Shifts in Soil Microbial Community Composition. Biogeochemistry 2007, 82, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, E.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Terol, E.; Mora-Navarro, G.; Marco da Silva, A.; N. Daliakopoulos, I.; Khosravi, H.; Pulido Fernández, M.; Cerdà, A. Quantifying Soil Compaction in Persimmon Orchards Using ISUM (Improved Stock Unearthing Method) and Core Sampling Methods. Agriculture 2020, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabameri, A.; Cerda, A.; Pradhan, B.; Tiefenbacher, J.P.; Lombardo, L.; Bui, D.T. A Methodological Comparison of Head-Cut Based Gully Erosion Susceptibility Models: Combined Use of Statistical and Artificial Intelligence. Geomorphology 2020, 359, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzi, A.; Omran, E.-S.E.; Bateni, S.M.; Pradhan, B.; Vasu, D.; Bagherzadeh, A. Modeling of Available Soil Phosphorus (ASP) Using Multi-Objective Group Method of Data Handling. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2016, 2, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, D.; Van Niekerk, A. Machine Learning Performance for Predicting Soil Salinity Using Different Combinations of Geomorphometric Covariates. Geoderma 2017, 299, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, G.; Biddoccu, M.; Ferraris, S.; Cavallo, E. Effects of Tractor Passes on Hydrological and Soil Erosion Processes in Tilled and Grassed Vineyards. Water 2019, 11, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, M.; Lapetite, J.M. A Multi-Scale Approach of Runoff Generation in a Sahelian Gully Catchment: A Case Study in Niger. Catena 2003, 50, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Carreras, N.; Krein, A.; Gallart, F.; Iffly, J.F.; Pfister, L.; Hoffmann, L.; Owens, P.N. Assessment of Different Colour Parameters for Discriminating Potential Suspended Sediment Sources and Provenance: A Multi-Scale Study in Luxembourg. Geomorphology 2010, 118, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.P.; Seixas, J.; Keizer, J.J. Modeling the Response of Within-Storm Runoff and Erosion Dynamics to Climate Change in Two Mediterranean Watersheds: A Multi-Model, Multi-Scale Approach to Scenario Design and Analysis. Catena 2013, 102, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameda, D.; Villar, R.; Iriondo, J.M. Spatial Pattern of Soil Compaction: Trees’ Footprint on Soil Physical Properties. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 283, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.H.; Wang, L.; Wan, X.G.; Peng, Q.Z.; Huang, Q.; Shi, Z.H. A Systematic Review of Soil Erosion in Citrus Orchards Worldwide. Catena 2021, 206, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đomlija, P.; Bernat Gazibara, S.; Arbanas, Ž.; Mihalić Arbanas, S. Identification and Mapping of Soil Erosion Processes Using the Visual Interpretation of LiDAR Imagery. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez, C.; Villi, O.; Berberoglu, S.; Cilek, A. Computer Vision-Based Citrus Tree Detection in a Cultivated Environment Using UAV Imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | CNBL | CND | CIT Index | Conv. Index | Hillshade | LSFactor | Plan Curv. | Prof. Curv. | Slope | Catch. Area | TWI (Mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 ± 1.4 | 4.5 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0 | −2.6 ± 14.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 6.6 ± 5.9 | 3.4 ± 1.5 |

| 2.2 ± 1.3 | 3.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 2.3 | −3.3 ± 22.3 | 0.8 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 129.8 ± 156.6 | 4.8 ± 2.6 |

| 3.0 ± 2.0 | 2.6 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 6.7 | −13.3 ± 12.7 | 0.8 | 3.1 ± 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 246.7 ± 345.1 | 5.0 ± 2.8 |

| 2.6 ± 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 5.9 | −8.3 ± 6.6 | 0.8 | 2.5 ± 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 344.5 ± 483.9 | 5.0 ± 3.0 |

| 2.1 ± 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 9.9 | −6.1 ± 8.6 | 0.8 | 3.3 ± 4.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 427.7 ± 601.9 | 4.7 ± 3.2 |

| 2.5 ± 1.7 | 4.4 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | −11.7 ± 13.7 | 0.8 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 8.4 ± 6.9 | 3.8 ± 1.5 |

| 2.2 ± 1.8 | 3.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 2.7 | −9.6 ± 10.1 | 0.8 | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 108.5 ± 150.7 | 4.0 ± 2.8 |

| 3.6± | 2.7 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | −7.4 ± 27.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 183.6 ± 260.6 | 6.0 ± 3.1 |

| 2.6± | 2.1 | 0.6 ± 0 | 0.0 ± 0 | 13.7 ± 9.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.8 |

| 2.2± | 1.8 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 9.1 | 1.8 ± 7.6 | 0.8 | 2.5 ± 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 290.5 ± 539.6 | 4.0 ± 3.0 |

| Model | Dataset | R2 | RMSE | MAE | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF (soil_loss) | Test (20%) | 0.29 | 141.9 | 113.6 | Train/test split, ntree = 500 |

| RF (SC) | Test (20%) | 0.28 | 124.2 | 95.4 | Low signal, short range |

| RF (Runoff) | Test (20%) | −0.46 | NaN | NaN | Poor model fit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Cambronero-Ruiz, L.; Moreno-Cuenca, L.; González-Vivar, J.; González-Moreno, M.T.; Rodríguez-Galiano, V. Integrating UAV-LiDAR and Field Experiments to Survey Soil Erosion Drivers in Citrus Orchards Using an Exploratory Machine Learning Approach. Water 2025, 17, 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243541

Rodrigo-Comino J, Cambronero-Ruiz L, Moreno-Cuenca L, González-Vivar J, González-Moreno MT, Rodríguez-Galiano V. Integrating UAV-LiDAR and Field Experiments to Survey Soil Erosion Drivers in Citrus Orchards Using an Exploratory Machine Learning Approach. Water. 2025; 17(24):3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243541

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigo-Comino, Jesús, Laura Cambronero-Ruiz, Lucía Moreno-Cuenca, Jesús González-Vivar, María Teresa González-Moreno, and Víctor Rodríguez-Galiano. 2025. "Integrating UAV-LiDAR and Field Experiments to Survey Soil Erosion Drivers in Citrus Orchards Using an Exploratory Machine Learning Approach" Water 17, no. 24: 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243541

APA StyleRodrigo-Comino, J., Cambronero-Ruiz, L., Moreno-Cuenca, L., González-Vivar, J., González-Moreno, M. T., & Rodríguez-Galiano, V. (2025). Integrating UAV-LiDAR and Field Experiments to Survey Soil Erosion Drivers in Citrus Orchards Using an Exploratory Machine Learning Approach. Water, 17(24), 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243541