Abstract

Urban coastal areas along the Mediterranean are exposed to short-duration convective rainfall, producing infrastructure disruptions and flood-related impacts. This study analyzes 45 rainfall episodes in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona between 2014 and 2022, combining radar products, rain gauge observations, and urban-scale impact datasets. Storm radar tracking enabled the identification of key spatiotemporal features and assessment of short-term forecasting performance. Convective cells were typically short-lived, lasting less than 30 min in most cases. The main goal of the research has been the comparison between VIL density (DVIL) radar field and short-duration rainfall intensity provided by rain gauges. This is the first study comparing both data types, being a pioneer in this field. We have found a linear relationship between both data types, with weaker values for larger values. More persistent cells had higher DVIL values, observing a difference in behavior with a break point at 2 g/m3. The tracking and nowcasting system were evaluated based on its ability to anticipate convective precipitation. It achieved good scores values (POD of 0.73 and FAR of 0.33), considering the difficulties of tracking this type of convective system. Finally, false alarms associated with elevated DVIL values suggested the difficulty of capturing storm severity by surface-based precipitation measurements.

1. Introduction

Intense short-duration rainfall events are becoming increasingly problematic in many urban areas around the world. The risk is particularly acute in densely populated coastal regions. Tourism constitutes a major economic sector in these areas, leading to seasonal population surges and elevated stress on infrastructure [1,2]. Intense rainfall and floods in such environments pose significant challenges for urban management and public safety. These events frequently disrupt transportation systems, overwhelming drainage networks, and affecting critical infrastructure [3,4,5]. The Mediterranean region exemplifies intense urbanization, with over 50% of its coastal cities among Europe’s most densely populated [6]. Tourism amplifies this pressure, temporarily inflating populations by 30–50% during peak periods. This trend increases beyond summer due to shifting travel patterns [7]. In addition, according to the latest MedECC report [8], climate change is projected to exacerbate this by likely increasing the frequency and intensity of phenomena such as droughts, heatwaves, and heavy rains and associated flooding.

In this context, the development of early warning systems has become a key objective for enhancing urban resilience. These tools can deliver very high-resolution precipitation forecasts. The effectiveness of these forecasts relies heavily on the availability of dense and accurate observational networks, because they can capture the rapidly evolving dynamics of convective storms [9]. Rain gauge networks remain essential for hydrological research, flood forecasting, storm frequency analysis, and the calibration of meteorological remote sensing systems [10,11]. Their high temporal resolution and point-based accuracy make them a critical source of information on rainfall intensity, especially for deriving design parameters such as intensity–duration–frequency (IDF) curves [12,13]. However, their limited spatial coverage constrains their utility in real-time applications. In contrast, weather radar offers volumetric data on storm structure and vertical development, presenting clear advantages for the detection, tracking, and nowcasting of convective systems [14,15]. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of intense rainfall episodes is crucial for improving early warning systems, considering that the predictability of convective precipitation is highly dependent on both spatial and temporal scales, as well as the prevailing convective forcing regimes [16].

The Mediterranean basin is characterized by complex interactions between synoptic-scale atmospheric patterns and local circulations. The small-scale structures include sea breeze convergence, cold-air intrusions, and urban heat island effects. These processes contribute to pronounced seasonal and diurnal variability in convective activity [17,18]. Recent studies have reported a relative increase in convective rainfall compared to stratiform [19]. These research works have underscored the need for tools capable of detecting and anticipating localized convective outbreaks.

In the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona (AMB), urban flood mitigation efforts began in the early 1990s. First studies consisted of the construction of underground retention tanks. Furthermore, the establishment of a dense rain gauge network managed by BCASA (Barcelona Cicle de l’Aigua SA–from the Catalan, Water Cycle from Barcelona SA, see [20] for more information) began. Despite the yearly drought period [21], the region experiences short-lived but highly disruptive rainfall episodes. These events are often associated with rapidly developing convective cells that remain difficult to forecast some hours in advance. As shown by [22,23,24], such events can lead to airport delays, but also to drainage system overflows and flood impacts, despite the commented engineering measures.

Several regional studies have examined the climatology precipitation structures, large convective systems and flash floods in the Iberian Peninsula [17,19,25]. However, only a few works have provided high-resolution characterizations of intense storms and their observed surface impacts using models and satellite in more specific areas [26,27,28], such as the AMB. Some recent works have contributed to the understanding of local convective processes and hydrometeorological impacts in limited domains [29,30,31,32]. In addition, only a small number of studies have focused on adapting and implementing centroid-based tracking algorithms for such concrete areas. The final aim of these works is to integrate them operationally, to improve short-term decision-making and early warning systems [2].

Bearing in mind the increasing effects caused by climate change on the Catalan coast [1,33] and the negative impact of human activity in the region, it is necessary to improve the capability to understand thunderstorms affecting Barcelona city and its surroundings. Therefore, a better understanding of the life cycle of storms will improve the future capabilities of nowcasting. This study applies the RaNDeVIL (Radar Nowcasting with Density of VIL) algorithm [22] to identify and track convective cells. We have used radar-derived DVIL data in the AMB from 2014 to 2022. The resulting storm trajectories and intensity metrics are compared with urban-scale impact data. The analysis also includes airport delays, drainage network incidents, and recorded flood events. The objectives of this work are to: (1) characterize the spatiotemporal structure of intense convective events in the AMB; (2) examine the relationship between DVIL and extreme rainfall; (3) assess the nowcasting potential of radar-derived storm tracking; and (4) analyze directional patterns, propagation speeds, and seasonal variability of convective storms. To sum up, the research has provided new clues in the understanding of those thunderstorms that produce damages on the city environment.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

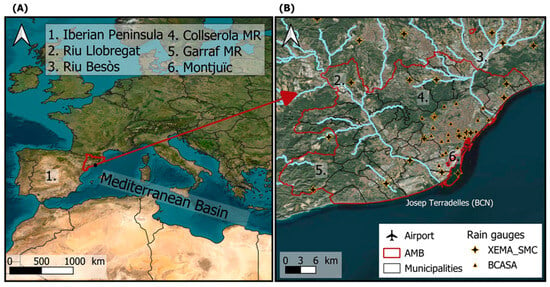

The area of study is the northwestern Mediterranean coast (Figure 1A), in central Catalonia (northeastern Spain). More specifically the research is concentrated within the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona (AMB). The region spans approximately 636 km2 and is home to 3.4 million inhabitants. Therefore, it has a high population density of 5340 people per km2. It is a densely urbanized landscape shaped by complex topography, including coastal plains, river basins (Figure 1B, numbers 2 and 3), and the nearby Collserola mountain range (Figure 1B). The presence of impervious surfaces and varied terrain makes the area particularly vulnerable to intense rainfall and urban flooding. Furthermore, the Josep Tarradellas Barcelona-El Prat Airport (Figure 1B), located near the coastline, is one of the critical infrastructures often affected by adverse meteorological events.

Figure 1.

Study area. (A) The location of Spain within Europe and the Mediterranean Basin with a legend at the top for the locations indicated by numbers in both images. (B) Zoom into the central area of Catalonia (red outline), showing the geopolitical boundaries of the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona municipalities (in grey) and the locations of the SMC (“XEMA_SMC”, stars) and BCASA (triangles) rain gauge networks. Base map from Esri “World Imagery.” Clear blue lines show the main rivers of the area. Sources: Esri, Maxar.

Figure 1 shows the location of the AMB within the broader Mediterranean context. Furthermore, the network of pluviometers (XEMA_SMC -Automatic Rain Gauges Network of the Servei Meteorologic de Catalunya, and BCASA) used and the administrative boundaries of municipalities within the AMB are also presented.

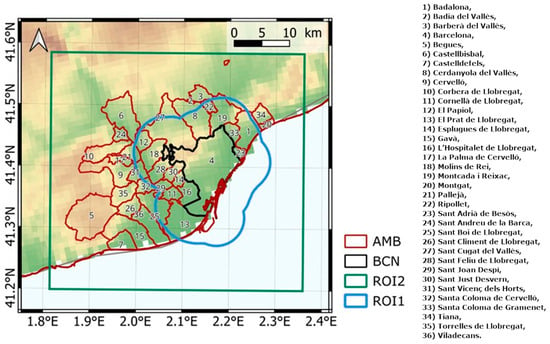

Two different regions of interest (ROIs) were defined to answer the objectives of the project:

- ROI1 (Figure 2): The municipality of Barcelona (101.3 km2) plus a 5 km buffer zone. It is used to compare maximum radar intensities with surface rainfall observations from BCASA. The area is restricted to Barcelona Municipality since it is where the networks are deployed;

Figure 2. Regions of interest (ROI) considered in this study. ROI1 (blue line polygon): 5 km buffer around the municipality of Barcelona used to apply a mask to the daily maximum DVIL products and extract the maximum value for comparison with the rain gauges. ROI2 (green rectangle): buffer of approximately 20 km2 around Barcelona that includes the municipalities of the AMB (Barcelona Metropolitan Area), within which the centroids of interest are identified.

Figure 2. Regions of interest (ROI) considered in this study. ROI1 (blue line polygon): 5 km buffer around the municipality of Barcelona used to apply a mask to the daily maximum DVIL products and extract the maximum value for comparison with the rain gauges. ROI2 (green rectangle): buffer of approximately 20 km2 around Barcelona that includes the municipalities of the AMB (Barcelona Metropolitan Area), within which the centroids of interest are identified. - ROI2 (Figure 2): A square area of 20 km approximate side around Barcelona encompassing the entire AMB. It is used to define and characterize the thunderstorms that affected the AMB. This secondary ROI is necessary to consider the complete path of thunderstorms that affect ROI1, because most grow far from and move to the area of interest.

2.2. Data Sources and Study Period

The research consisted of the combination of radar, rain gauge, and impact-related datasets to characterize high-intensity convective rainfall events in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona (AMB) during the 2014–2022 period. This period was chosen to ensure the simultaneous availability of all relevant datasets (see more details about this point and of spatial and time resolution for each data source in the next lines), allowing for consistent and comprehensive analysis.

- Radar data: Volumetric radar products from the Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya’s (SMC) XRAD network were used to characterize the convective structures and intensity of the selected events. The XRAD network comprises four C-band Doppler weather radars, strategically located to provide overlapping coverage of Catalonia with a typical range of up to 130 km [34,35]. The system operates at a spatial resolution of 1 km and a temporal resolution of 6 min, delivering corrected volumetric reflectivity fields that are operationally filtered to remove non-meteorological echoes as described in [2,36]. All radar data were pre-processed and provided by the SMC following their internal quality-control and composite procedures. Data in geoTIFF format have been available from April 2013. For this study, three radar-derived products were used: (a) Vertically Integrated Liquid (VIL), providing an estimate of the total liquid water content in the atmospheric column; (b) Echo Top 12 dBZ (TOP12), indicating the maximum height at which a reflectivity of 12 dBZ is observed, as a proxy for storm vertical development; (c) Constant Altitude Plan Position Indicator (CAPPI), reflectivity products at fixed altitudes, used to assess horizontal storm structure at different vertical levels. As part of these products, DVIL fields were estimated from dividing the VIL by the TOP12, similarly to [22];

- Rain gauge data: High-resolution rainfall data (1 min and 5 min intensities) from the dense network of balancing rain gauges (24 tipping bucked sensors) from the BCASA network in Barcelona city [20,37]. Rain gauges are distributed irregularly through the complex city geography (see Table 1 in [37] for the exact location of all the sensors). Data have been available since 2000. The sensors have a collector area of 400 cm2 with a resolution of 0.1 mm and an integration time of 1 min [37];

- Drainage network incident reports: Records of drainage system disruptions caused by heavy rainfall (2011–2022) facilitated by the Barcelona Municipality and BCASA. Those records included precise location and disruption type;

- Airport delays: Arrival ATFM Delays at Josep Tarradellas Barcelona-El Prat Airport (airport of Barcelona) attributed to meteorological causes from EUROCONTROL open data. Arrival ATFM delay data from EUROCONTROL (“apt_dly” files) are available as daily CSV files from 2014 onwards via the ANS Performance portal;

- INUNGAMA flood database: Historical database of flood events across Catalonia (1901–2022), from which those affecting the AMB were extracted [38].

Table 1 summarizes the particular use of each type of source and the time and spatial resolution.

Table 1.

Summary of the different sources used in the research.

Table 1.

Summary of the different sources used in the research.

| Source | Time Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radar | 6 min | 1 km × 1 km | Identification, tracking, and characterization of thunderstorms in ROI2 |

| Rain gauges | 1 min | Irregular | Selection of heavy rainfall episodes in ROI1 |

| Airport delays | Daily | Null | Selection of days with effects on the airport |

| INUNGAMA | Daily | Municipal | Selection of days with effects in ROI2 |

Information from INUNGAMA, airport ATFM arrival delay records, and incident reports from the drainage network were used to identify episodes of interest for analysis in this study. The identification of the episodes of interest is described in the following lines.

Since the rain gauge network within the AMB is not uniformly dense but rather concentrated in Barcelona, while other rain gauge networks have scarce coverage across the area, we adopted a combination of a top-down and bottom-up approaches to define the sample of relevant dates to analyze. As has been explained before, radar and rain gauge time resolution are quite similar (six and five minutes). Therefore, the data of both sources are comparable, directly or considering thirty minutes cumulation (adding five radar images or six rain gauge registers). Furthermore, spatial resolution of both sources is similar, in spite the irregularity of the rain gauge network. In consequence, both networks can be integrated into a unique system. Meteorological and impact-based criteria from different sources were integrated. The final selection includes 45 days (Table 2) that simultaneously meet the following conditions:

Table 2.

Dates resulting from the sample selection criteria described: (B∪C)∩D∩A.

- Sample A: Rainfall days exceeding 10 mm of precipitation in at least one rain gauge from BCASA’s rain gauge network;

- Sample B: Days with reported incidents in the drainage network of Barcelona;

- Sample C: Days included in the INUNGAMA database as part of a flood affecting the Barcelona region;

- Sample D: Days with reported impacts in the form of meteorological-related arrival delays at the airport of Barcelona.

This strategy ensures that selected days do not only exhibit significant rainfall. In addition, the events present a clear convective nature and tangible urban impact. While this prioritizes high-impact cases, it may exclude moderate-intensity convective events and does not guarantee full representativeness of all convective episodes during 2014–2022. Consequently, some convective storms might not be included.

2.3. Convective Storm Tracking with RaNDeVIL

The RaNDeVIL storm tracking module is an algorithm developed within the SINOPTICA (Satellite-borne and IN situ Observations to Predict The Initiation of Convection for ATM) SESAR JU project [22]. In that project it was applied to identify, monitor, and characterize intense storms affecting Italian airports. Using 6 min DVIL magnitude (computed from VIL and TOP12 composite radar products), storm cells were detected as clusters of minimum two pixels exceeding the threshold of 0.5 g/m3. One advantage of using DVIL instead of VIL is that the first parameter is not dependent on the seasonality, as happens with the second one [39]. Therefore, the threshold can be applied to any rainfall structure detected with the radar for any season of the year. Furthermore, although the size of the winter thunderstorms is smaller than summer ones [2,14,19,20,34,39], the minimum size of 2 pixels is exceeded for those storms with some convective signature. The temporal tracking was implemented by linking overlapping cell areas in consecutive images and assigning each a unique identifier. We considered only those cells detected in at least two consecutive time steps and located within ROI2 at some point of their trajectory. For each cell, we estimated the life cycle characteristics (trajectory, duration, movement direction, and speed). Furthermore, the radar parameters (DVIL, TOP12, and area) were estimated for the whole tracking period. These properties were later used to evaluate storm behavior and monthly or seasonal variability in a descriptive way.

Finally, we have analyzed the relationship between storm life cycle and precipitation intensity and urban impacts.

The predictive skill of RaNDeVIL centroid detections for 5 min convective precipitation was evaluated in two steps. First, each detection was categorized according to the temporal relationship between radar-identified storm cells and observed precipitation. The definition of convective precipitation adopted in this study follows [36], who considered it as the exceedance of a 5 min precipitation intensity of 35 mm/h. This threshold has been adopted according to previous analysis of the precipitation regime in the region of study (see, for instance, [1,19,20,34,35,40]). All these previous analyses converged in the high correlation between this threshold and 43 dBZ reflectivity value, which also corresponds to convective rainfall in radar fields. Two time-based metrics were computed for each detected cell:

- The time difference (in minutes) between the detection of a cell that affected AMB and the start of a convective precipitation period (TimeDiffToConvection). Positive values indicate that the cell was detected before the convective precipitation;

- The time difference between the first detection of a storm cell that affected the AMB and the closest time belonging to a convective period (based on 5 min intensity precipitation, TClosestToConv).

Each cell was then assigned to one of the mutually exclusive categories, using a logical hierarchy. This approach ensures that only one label is assigned to each case and accounts for both forecast lead time and proximity to convective period.

Second, based on this classification, the forecast skill was assessed using standard categorical metrics [41]:

- Probability of Detection (POD): fraction of convective rainfall successfully forecasted with previous initiation of the RaNDeVIL tracking;

- False Alarm Ratio (FAR): fraction of RaNDeVIL tracked cells that were not followed by convective precipitation in BCASA’s and SMC’s pluviometers;

- Critical Success Index (CSI): proportion of correct forecasts among all attempts;

- Bias: ratio between forecasted and actual convective rainfall occurrence;

- Success Ratio (SR): complement of FAR (SR = 1 − FAR).

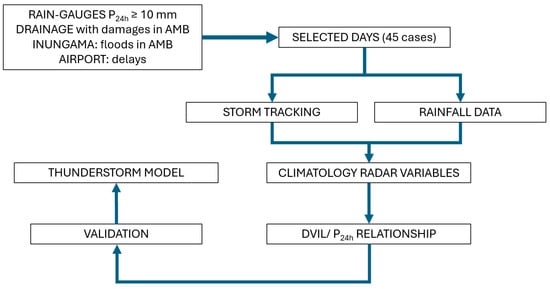

Late detections (i.e., TimeDiffToConvection = 0) were reported separately because they match with convective precipitation but with no lead time. Therefore, there is no predictive value for operational decision-making. Figure 3 shows the complete flow chart of the process followed in the research.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the applied methodology.

3. Results

It is worth noting that Section 3.1 compares radar data with surface registers in ROI1, to identify the events of study. From these days, we have searched for all thunderstorms that occurred in ROI2. However, they are not compared to rain gauge data in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, because the objective in these sub-sections is to characterize the radar detected storms in a general way, not for the case of ROI1.

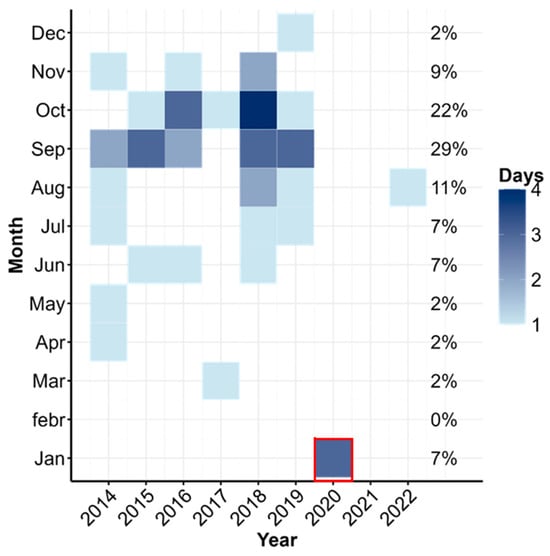

3.1. Temporal and Seasonal Distribution and Rainfall Properties of the Episodes

The 45 selected days show a strong seasonal pattern, with most episodes concentrated between June and November (Figure 4). September and October account for 29% and 22% of the events, respectively, highlighting the high convective activity during the late summer and early autumn in the Western Mediterranean region. It is important to consider the exceptional winter episode, Storm Gloria in January 2020 [41], which occurred out of the usual season. This episode of four days has a notorious impact on the results, but is an anomaly associated with climate change conditions. In any case, those days are the unique contribution of January days for the whole period.

Figure 4.

Climatology of the resulting 45 days after applying the selection criteria. The three days of January 2020 (highlighted in red) correspond to a highly unusual rainfall episode in the region that affected the entire Iberian Peninsula (see [33,41] for more details).

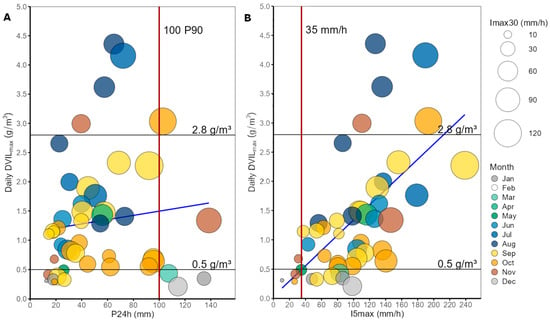

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of maximum DVIL (DVILmax) values within the ROI1 (municipality of Barcelona). Panel A shows the relationship between DVILmax and maximum 24 h accumulated precipitation (P24h). Panel B compares DVIL with 5 min maximum rainfall intensity (I5max). In both panels, the colors differentiate the different months of the studied days. Furthermore, the marker size is scaled according to the 30 min maximum rainfall intensity (I30max), providing additional insight into short-duration convective rainfall severity. The first-level intensity alert was overpassed in 30 of the 45 events. This threshold is based on the SMC operational warning system (more than 20 mm in 30 min).

Figure 5.

Relationship between DVILmax within the ROI and (A) maximum 24 h accumulated precipitation, and (B) maximum 5 min rainfall intensity in the municipality of Barcelona. Point colors indicate the month of occurrence, and marker size is scaled according to the corresponding maximum 30 min rainfall intensity. Blue lines indicate the Pearson correlation commented on the text.

Daily accumulated precipitation ranged from 41 mm at the 50th percentile (P50) to 100 mm at the 90th percentile (P90). The maximum recorded value was 139 mm. Those values indicate a combination of moderate and extreme rainfall days. Intense short-duration rainfall was also frequent, with P90 value of 83 mm/h for I30max. This result indicates even more intense short-term rainfall in 10% cases. Regarding DVIL, the daily maximum values reached 1.6 g/m3 at P50 and exceeded 2.8 g/m3 at P90. This last value identifies the upper decile of days with a higher estimate of liquid water. Furthermore, the P90 value coincides with the threshold found in the analysis of [39] for severe hail (2.75 g/m3). Therefore, severe weather probably occurred in those episodes in Figure 5 with DVIL values similar or higher to that threshold. In Catalonia the severe threshold consists of hail (>2 mm) or damaging convective wind gusts (>90 km/h). In consequence, these events have different characteristics from the rest. This fact reinforces the usefulness of DVIL as a diagnostic tool in the surveillance of high-impact meteorology.

From a seasonal perspective, the majority of the most extreme P24h values (above P90) occurred in early 2017, late 2018, and early 2020, while the most extreme I20max were mostly recorded in 2018 and 2019. These findings are consistent with previous studies, such as [38,40], who identified a seasonal concentration of intense rainfall episodes in autumn and summer, with fewer events in winter and spring.

Correlation tests revealed a positive Pearson correlation between DVILmax and I1max (R2 = 0.423, p < 0.001) and slightly lower but still significant correlation with I5max (R2 = 0.332). Among the non-linear models tested, only the Generalized Additive Model (R2 = 0.444) and the Segmented Regression (R2 = 0.389) showed improved performance, with similar R2 but reduced residuals. The segmented regression identified a break point in DVILmax at 1.14 for I1max and at 2.27 g/m3 for I5max, indicating a change in the relationship slope beyond these thresholds.

3.2. Storm Tracking Analysis

8117 instantly identifications corresponding to 322 life-cycle storm cells through RaNDeVIL across 30 of the 45 selected days. In this case, the research considered ROI2 to have a more representative set of thunderstorms. In the rest of the days, the DVIL did not exceed the 0.5 g/m3 threshold for a region of 2 pixels or more during at least 12 min. A seasonal analysis (Figure 6A and Table 3) revealed that most storm centroids were detected during autumn (SON) and summer (JJA). The average identifications for those seasons were 245 and 352, respectively. In contrast, spring (MAM) accounted for only 79 total identifications, concentrated in just two days of the sample. Due to the limited number of winter and spring cases, and the absence of consistently high DVIL values needed to sustain reliable tracking, no detailed characterization of storm cells is provided for these seasons. The storm cell properties and their seasonal variability are explored further in the following sections.

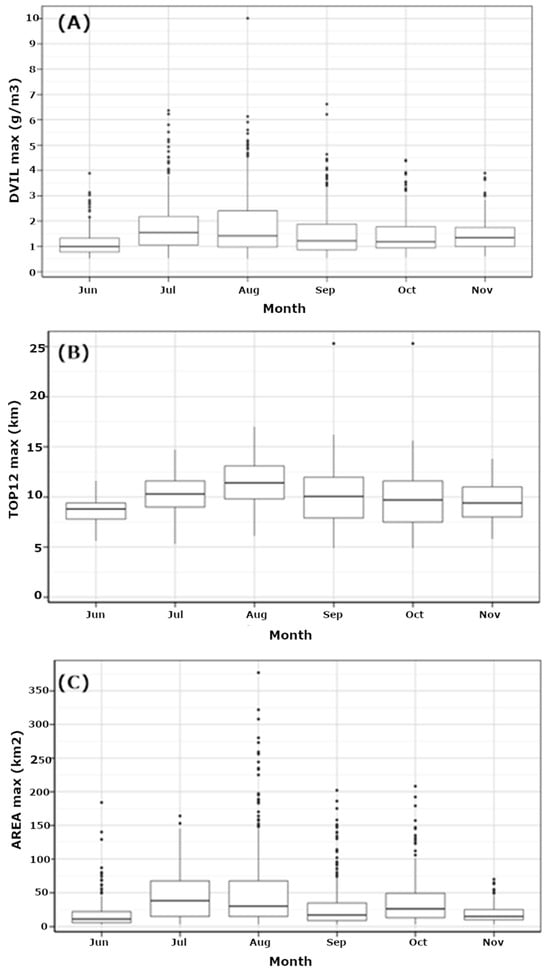

Figure 6.

(A) Monthly boxplot distribution of maximum DVILmax for storm cells tracked within ROI2 at any point during their lifecycle. (B) Monthly boxplot distribution of maximum TOP12 values (km) for storm cells tracked within ROI2 at any point during their lifecycle. (C) Monthly boxplot distribution of total storm area (km2) for storm cells tracked within ROI2 at any point during their lifecycle.

Table 3.

Mean radar variables for the different months.

3.2.1. Monthly Variability of Storm Parameters

The convective storm cells tracked with RaNDeVIL displayed marked differences in vertical extent, liquid water content, and spatial coverage across months. DVILmax values showed notable seasonal variability. July and August exhibited the widest interquartile ranges (1.1–2.2 g/m3 and 1.0–2.4 g/m3, respectively) and the highest medians (1.55 and 1.45 g/m3), consistent with more severe weather phenomena occurrence [39,42,43]. June and November, on the other hand, showed lower variability and median values, with June presenting the lowest DVIL values. Therefore, it is probable that there was lower water content in storm cores. Anomalously high DVILs were most frequent in late summer and early autumn, particularly in August and September. This is also coincidental with deep convection occurring near to the coast during those months, as explained by [44].

Seasonal patterns are also observed for TOP12 (Figure 6B). The medians increased from June to August (8.5–11.5 km), decreasing towards November. The widest interquartile ranges were observed in October and November, reflecting more variability in intensity. These results are coincidental with [45] for an analysis of the whole Catalan territory.

Storm area distributions revealed that June and November cases were typically smaller (Figure 6C), with median areas of 12 and 14 km2 and narrow interquartile ranges (<25 km2). July recorded the largest median storm size (~40 km2), whereas August, though with a smaller median, exhibited a greater number of extreme events, with some storms exceeding 150 km2. September and October also presented a significant number of large storm outliers (75–150 km2), despite more moderate central distributions.

3.2.2. Diurnal Patterns of Convective Activity

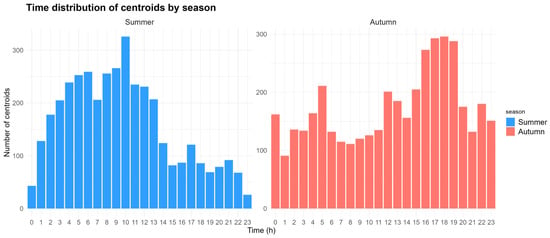

We have found that hourly distribution patterns also vary seasonally. In summer (Figure 7, left), convective centroids peak clearly between 3 and 13 UTC, with an absolute maximum at 10 UTC. This may be associated with daytime heating and the development of sea breezes. In contrast, autumn (Figure 7, right) shows a distribution with two peaks, early morning (around 5 UTC) and late afternoon (16–19 UTC), likely reflecting both synoptic-scale influences and local mesoscale dynamics.

Figure 7.

Total number of storm centroids at each timestep, separated by season, for the selected days within ROI2. Tracking was performed using the RaNDeVIL module with a minimum DVIL threshold of 0.5 g/m3.

In summer, a high number of storm centroids identified from late night to early morning may be partially influenced by the urban heat island (UHI) effect. This phenomenon maintains elevated surface temperatures overnight and can promote nocturnal convection [3]. A UHI, combined with abundant low-level moisture and sea-breeze interactions creates the perfect environment to trigger early-morning or nocturnal convective activity [18]. Around 8 UTC, the start of the sea breeze may enhance the upward motion of moist air, contributing to the absolute peak observed in the diurnal distribution.

In autumn, the hourly distribution of centroids substantially coincides with that described by [46,47] for mesoscale convective systems (MCSs) in Catalonia during autumn: a clear increase is observed from 12 UTC and an afternoon maximum around 17–19 UTC. Our distribution, however, is slightly more irregular and presents a secondary maximum in the early morning (~05 UTC). These differences are compatible with the different study samples: the present study has a much more restricted spatial scope (ROI1), and centroids correspond to small, intense storm nuclei instead of large MCSs. The morning peak is plausibly explained by the breakdown of the nighttime thermal inversion and the entry of sea breezes. Meanwhile, the mid-afternoon maximum is adjusted to the diurnal thermal convection cycle, with insolation, marine humidity, and convergence by breezes as the main mechanisms [48].

3.2.3. Storms’ Persistence

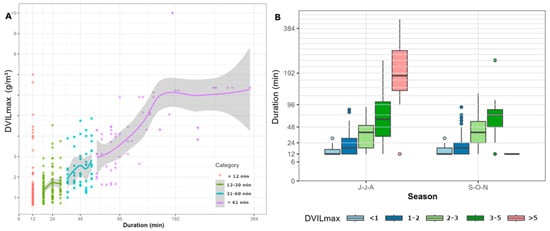

Figure 8A shows the distribution of DVILmax grouped into four duration classes, fitting a Generalized Additive Model (GAM). This model helps to identify the mean behavior with its corresponding uncertainty interval. For centroids tracked for less than 12 min, we obtained a large dispersion of DVILmax values. This is likely related to the causes mentioned above for this group. For the 13–30 min group (33%), DVILmax values mostly remained between 1 and 1.8 g/m3. In contrast, for the 31–60 min group (17%) there was a clear increase in DVILmax, with values between 1.7 and 2.94 g/m3. Finally, the most persistent cells (>61 min, 19%) generally exceeded (with some exceptions) 3 g/m3.

Figure 8.

(A) DVILmax values of the tracked centroids, classified by tracking duration, with a Generalized Additive Model (GAM) fitted. The x-axis is shown on a square-root scale to reduce the effect of very long durations and improve visual comparability; tick marks correspond to actual minutes. (B) Box-and-whisker plot of tracking duration for centroids affecting ROI1, grouped by season and by DVIL category, using a quadratic scale on the y-axis (duration). Note: one outlier from July 2016 corresponding to a storm with duration >7 h is excluded.

The smoothed trend in the figure (GAM) increased up to ~90–120 min, stabilized, and then increased again for very long durations; the uncertainty interval widened in this last segment because we had few cases. Complementarily, the interquartile ranges of duration were 12–24 min in summer and 12–18 min in autumn, confirming that most tracks were short.

Figure 8B summarizes the seasonal variability of duration by DVILmax category: <1, 1–2, 2–3, 3–5, and >5 g/m3. In summer, duration tended to increase with DVIL, although it became more variable in the 3–5 g/m3 range. In autumn, the longest durations were associated mainly with the 2–3 g/m3 category, whereas cells in the 1–2 g/m3 range tended to have shorter tracks. Very few autumn cells exceeded 5 g/m3. Overall, some summer maximums exceeded this threshold, in line with regional climatology that associates summer with greater vertical development and hydrometeor content (as was recently explained).

3.3. Predictive Capability of Intense Rainfall with RaNDeVIL

In this section we evaluate the nowcasting potential of DVIL-based tracking as early warning tool for intense precipitation events in the AMB. To do this, the predictive skill of centroid detections relative to convective precipitation intensities was analyzed as described in Section 3.2.1.

Of the 322 centroids considered in the analysis, 39% of them anticipated a period of convective precipitation at the BCASA rain gauges (Table 4). The median lead time was 30 min (similarly to the results obtained by [48]). However, there were 86 cases (27%) in which centroid identification began when the pluviometric convective criteria had already been met or were being met (late detections). Finally, fifteen percent of convective-precipitation onsets could not be associated with any RaNDeVIL tracking, and 19% of the onsets of tracked cells could not be related to a convective period in the available rain gauges. The mean DVIL values associated with each category did not show large differences; nonetheless, the highest mean DVIL values corresponded to the non-detections, followed by the false positives. Finally, late detections and hits exhibited virtually the same mean values.

Table 4.

Results of the categorical classification, which was based on the temporal relationship between cell detection (with RaNDeVIL) and convective precipitation observations (BCASA), and the averages of the average DVIL (DVILmean), minimum (DVILmin), and maximum (DVILmax) for each centroid considered as a predictor.

Table 5 shows the values obtained for the main categorical verification indicators, by which we assessed the ability of the RaNDeVIL-based tracking system to anticipate periods of convective precipitation observed in ROI1 rain gauges. In this process, late detections were tallied separately: although they indicated the existence of convective activity, they could not be considered hits because they did not provide a useful lead time for prediction; at the same time, they could not be considered false positives. For this reason, they were not included in the calculation of the verification metrics. The system achieved a Probability of Detection (POD) for convective precipitation (as observed by the BCASA rain gauges) of 72.8%, indicating that most convective intervals were preceded by centroid identification. The False Alarm Ratio (FAR) was 33.3%, meaning that one third of the detected cells were not associated with a convective period at the rain gauges. The Critical Success Index (CSI) was moderate, at 0.534, and the Bias was 1.092, indicating no tendency to over- or underestimate the occurrence of convective precipitation.

Table 5.

Statistic verification indicators about using the tracking as predictor for convective rainfall.

4. Discussion

This study offered an integrated characterization of the convective storms that affected the AMB by combining radar tracking (RaNDeVIL) with rain-gauge observations. The results showed distinct spatial and temporal patterns between summer and autumn and highlighted the potential of DVIL for short-term nowcasting of intense rainfall.

A marked positive correlation was observed between DVILmax and the 1 and 5 min rainfall intensities (I1max, I5max), reflecting the physical coupling between storm vertical structure (captured by DVIL) and surface precipitation. DVIL represents the vertically integrated liquid water content, so higher DVIL values typically indicate stronger updrafts and deeper convective cores capable of sustaining larger amounts of condensed water. These conditions favor intense rainfall at the surface when hydrometeors grow rapidly and precipitate through efficient collision-coalescence and melting processes. In consequence, we detected good fits from linear models. However, discrepancies at high DVILmax values and the small sample size in that range suggest that additional factors modulate this relationship. For instance, the presence of solid hydrometeors (hail, graupel) can inflate radar-derived DVIL without a proportional increase in liquid rainfall [20], while strong updrafts may temporarily suspend precipitation aloft. Attenuation, beam-filling effects, and bright band enhancement near the melting layer can also lead to localized DVIL overestimation without corresponding surface intensities [21,35]. Urban clutter and uneven rain-gauge coverage further limited the validation [11,49].

Segmented regression suggested a change in slope at high DVILmax values; however, the small sample in those ranges limited statistical significance. Even so, this behavior had a physical basis: high DVIL values reflect large amounts of ice in the radar scan, implying the possibility of heavy graupel or hail and strong winds, which do not always translate into higher surface rainfall intensities. This was consistent with studies that emphasize (i) the limitations of tipping-bucket gauges under very high intensities and (ii) radar sensitivity to non-liquid hydrometeors [50,51,52,53]. Additional high-resolution data on hail occurrence (e.g., [39]) could further refine the interpretation of DVIL thresholds for hail detection.

The RaNDeVIL algorithm was applied to the selected days analyzed, detecting storm cells in 90% of them. At least one tracking lasts 30 min in most cases. A salient finding from the tracking analysis was the short duration of many identified cells: 32% decayed below DVIL of 0.5 g/m3 in under 12 min, while 33% did so before 30 min. Although tracking exceeded one hour in some cases, most cells lasted between 6 and 24 min.

Regarding the radar-derived physical parameters (DVIL, TOP12, and storm area), the results were consistent with previous studies on convection in Catalonia. The highest medians of DVIL and TOP12 in summer and early autumn pointed to greater vertical development and the presence of graupel or hail, factors already highlighted by various authors in relation to the climatology of hail events and flash floods in the region [50,53]. By contrast, the smaller and less variable areas observed in June and November suggested more localized and less persistent convective systems.

As noted, the spatial distribution of centroids was seasonally differentiated and coherent with the region’s mesoscale dynamics. In summer, a more heterogeneous and inland distribution predominated, influenced by the urban heat island effect, thermal instability, and sea-breeze convergence [18]. In autumn, storms often initiated over the sea and moved parallel to the coast, in line with stronger synoptic forcing and the supply of marine moisture, frequently after the breakdown of the nocturnal inversion and within the diurnal convective cycle. This pattern was consistent with [54], who, through lightning density, identified an inland thunderstorm activity maximum in summer and a shift of activity toward coastal and maritime zones in autumn. In both seasons, the start of tracking occurred close to the AMB (0–24 km), but this distance was on average 6 km greater in summer than in autumn.

The propagation direction of storm cells also showed seasonal differences, with summer events predominantly moving from the S–SW to N–NE, while autumn cells exhibited greater variability, frequently aligning parallel to the coast. Mean propagation speeds ranged from 8 to 14 m/s in summer and 5 to 12 m/s in autumn, consistent with previous findings for the Catalan coast [2] and linking low-level circulation to convective trajectories in the region.

The diurnal distribution obtained here for autumn showed strong similarities to that described by Rigo et al. [46,47] for autumn MCSs in Catalonia. However, the distribution observed here was somewhat more irregular, with an increase around 05 UTC and a maximum between 17 and 19 UTC. These particularities were explained in part by the fact that RaNDeVIL captured a broader range of convective structures (multicellular systems, isolated or embedded convection). Furthermore, in the current analysis it was a more restricted spatial scope of the study (the AMB rather than all of Catalonia). In summer, the diurnal distribution showed an increase from the early night to early afternoon (03–13 UTC), with a maximum around 12 UTC.

Although differences across months and seasons were identified, these were not formally tested for statistical significance because of the limitations of the study sample and the exploratory nature of the research. Future work may benefit from addressing this aspect to confirm whether the observed patterns are statistically robust.

The categorical classification revealed that in 39% of cases RaNDeVIL tracking had predictive value for convective precipitation, while in 27% simultaneous centroids were detected with insufficient lead time to be considered predictive. These late detections showed a slightly higher mean DVILmax (2.84 g/m3) than the hits (2.67 g/m3), which could indicate sudden storm intensification that was harder to anticipate. The false positives (19%) showed higher mean DVIL than the hits (~1.09 g/m3). This suggests they were not always weak systems. These discrepancies could have been due both to limitations in rain-gauge coverage and to the presence of solid hydrometeors not reflected in rainfall records. Despite small differences among categories, DVIL values overlapped, which limited its discriminating capacity and underscored the need to consider additional variables. Regarding verification, tracking as a predictor of convective precipitation showed moderate performance: a POD of 0.728 and a CSI of 0.534 indicated reasonable sensitivity, with a bias close to neutrality (1.092) and a relatively high FAR (0.333).

While the results highlight the value of DVIL as a diagnostic tool for intense convective episodes, some limitations must be acknowledged. Radar-based parameters such as DVIL are sensitive not only to liquid water but also to solid hydrometeors (e.g., graupel, hail), which can result in high DVIL peaks without correspondingly high surface rainfall at gauges. Conversely, rain gauge networks may undersample extreme values during short, high-intensity bursts or miss hail-dominated events altogether. These limitations underline the importance of complementary multi-parameter and multi-sensor approaches. Future efforts should incorporate additional high-resolution impact data (e.g., hail, lightning, damaging winds) to improve discrimination of storm severity and operational nowcasting skill. The alignment of spatial and temporal patterns with impact-based and regional analyses reinforces the robustness and relevance of the identified mesoscale convective dynamics.

5. Conclusions

This study has combined the storm tracking algorithm, RaNDeVIL, and rainfall to characterize the convective storms that affected the AMB during the period 2014–2022 and has evaluated tracking with the DVIL as an operational indicator of short-term convective precipitation.

The DVILmax relationship with precipitation intensity is generally linear but shows a change in slope to high DVIL: increases in DVILmax do not always translate into more precipitation at the surface, a fact that may relate to the uneven distribution of the rain gauge network across the AMB or an intensification of the radar signal by the presence of solid hydrometeors.

For the identified centroids, seasonal patterns have been identified, with a more heterogeneous distribution in summer and more concentrated over the sea in autumn. The maximum frequency of identifications occurred between 05–13 UTC in summer and between 15–19 UTC in autumn. Typically tracked cells had short duration monitoring (often < 30 min), with more heterogeneous spatial distributions in summer, when the tracks also started at a greater distance from the AMB. In autumn the distribution is more concentrated over the sea.

As a precursor of convective precipitation (I5min > 35 mm/h), the proposed categorical classification method indicates that the tracking algorithm maintains a very good correlation with convective precipitation but can only anticipate it in 42% of cases (anticipation ≈ 18 min); in 21% of cases there was already convective precipitation when monitoring has begun. Having a rainfall network with sufficient resolution to calculate 5 min intensities throughout the AMB region would make it possible to check if the false alarm rate decreases or if it is related to the presence of solid hydrometeors.

Despite its limitations, RaNDeVIL shows good ability as a tool to support the immediate surveillance of convective episodes in urban environments. Its ability to anticipate intense precipitation is moderate, but useful, especially if it is integrated with dense and homogeneous surface networks and with complementary indicators, such as electrical discharges or the characterization of hydrometeors. To further improve predictive performance, future work should focus on: (i) refining threshold definitions and adopting adaptive criteria that account for regional and daily variability; (ii) incorporating additional radar-derived parameters and auxiliary data sources (e.g., lightning, vertical structure) to reduce false alarms and late detections; and (iii) expanding validation with larger datasets and including statistical significance on seasonal features to enhance robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.E.; methodology, L.E.; software, L.E.; validation, L.E. and T.R.; formal analysis, L.E.; investigation, L.E.; resources, M.d.C.L.; data curation, T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.E.; writing—review and editing, T.R. and M.d.C.L.; visualization, L.E.; supervision, T.R. and M.d.C.L.; project administration, M.d.C.L.; funding acquisition, M.d.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This Research has not received any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to (legal/contractual/third-party data) restrictions, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The codes used for data processing and the RaNDeVIL algorithm are openly available at the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/lauesbri/CodisPhD (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out within the framework of the I-CHANGE project (Individual Change of HAbits Needed for Green European transition), from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program. The work also received institutional support from the Water Research Institute of the University of Barcelona (IdRA) and was developed in collaboration with Barcelona Cicle de l’Aigua, S.A. (BCASA) and the Meteorological Service of Catalonia (SMC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IDF | Intensity–duration–frequency curves |

| VIL | Vertical Integrated Liquid |

| DVIL | VIL Density |

| AMB | Metropolitan Area of Barcelona |

| BCASA | Barcelona Water Cycle SA |

| XEMA_SMC | Rain gauges network of the Servei Meteorologic de Catalunya |

| RaNDeVIL | Radar Nowcasting with Density of VIL |

| TOP12 | Echo Top 12 dBZ |

| SINOPTICA | Satellite-borne and IN situ Observations to Predict The Initiation of Convection for ATM |

| ATM | Air Traffic Management |

References

- Llasat, M.C.; Marcos-Matamoros, R.; Pascual, R.; Rigo, T.; Insúa-Costa, D.; Crespo-Otero, A. Western Mediterranean flash floods through the Lens of Alcanar (NE Iberian Peninsula): Meteorological drivers and trends. Atmos. Res. 2025, 326, 108266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Moral, A.; del Carmen Llasat, M.; Rigo, T. Connecting flash flood events with radar-derived convective storm characteristics on the northwestern Mediterranean coast: Knowing the present for better future scenarios adaptation. Atmos. Res. 2020, 238, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.; Lin, Q. Urban heat islands and summertime convective thunderstorms in Atlanta: Three case studies. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.K.S.; Chuah, C.J.; Ziegler, A.D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Varis, O. Towards resilient flood risk management for Asian coastal cities: Lessons learned from Hong Kong and Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Leng, G.; Su, J.; Ren, Y. Comparison of urbanization and climate change impacts on urban flood volumes: Importance of urban planning and drainage adaptation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Urban sprawl in Europe. Joint EEA-FOEN report. 2016. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/urban-sprawl-in-europe (accessed on 23 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism. World tourism barometer. UN Tour. 2024, 22, 19. [Google Scholar]

- MedECC. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin—Current Situation and Risks for the Future. First Mediterranean Assessment Report; Union for the Mediterranean: Marseille, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Coll, M.; Ballester-Merelo, F.; Martinez-Peiró, M.; De la Hoz-Franco, E. Real-time early warning system design for pluvial flash floods—A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bournas, A.; Baltas, E. Analysis of Weather Radar Datasets through the Implementation of a Gridded Rainfall-Runoff Model. Environ. Process. 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overeem, A.; Leijnse, H.; Van Der Schrier, G.; Van Den Besselaar, E.; Garcia-Marti, I.; De Vos, L.W. Merging with crowdsourced rain gauge data improves pan-European radar precipitation estimates. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 649–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervos, N.A.; Baltas, E.A. Development of Experimental Low-Cost Rain Gauges and their Evaluation During a High Intensity Storm Event. Environ. Process. 2024, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtis, I.M.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. Update of intensity-duration-frequency (IDF) curves under climate change: A review. Water Supply 2022, 22, 4951–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Moral, A.; Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C. A radar-based centroid tracking algorithm for severe weather surveillance: Identifying split/merge processes in convective systems. Atmos. Res. 2018, 213, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.; Wiener, G. TITAN: Thunderstorm Identification, Tracking, Analysis, and Nowcasting—A Radar-based Methodology. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 1993, 10, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunobu, T.; Puh, M.; Keil, C. Flow- and scale-dependent spatial predictability of convective precipitation combining different model uncertainty representations. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 150, 2364–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasat, M.C.; Llasat-Botija, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Lindbergh, S. Flash floods in Catalonia: A recurrent situation. Adv. Geosci. 2010, 26, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazon, J.; Pino, D. Nocturnal offshore precipitation near the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2013, 120, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasat, M.C.; del Moral, A.; Cortès, M.; Rigo, T. Convective precipitation trends in the Spanish Mediterranean region. Atmos. Res. 2021, 257, 105581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbrí, L.; Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C.; Aznar, B. Identifying Storm Hotspots and the Most Unsettled Areas in Barcelona by Analysing Significant Rainfall Episodes from 2013 to 2018. Water 2021, 13, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hateren, T.C.; Sutanto, S.J.; Van Lanen, H.A. Evaluating skill and robustness of seasonal meteorological and hydrological drought forecasts at the catchment scale–Case Catalonia (Spain). Environ. Int. 2019, 133, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esbrí, L.; Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C.; Biondi, R.; Federico, S.; Gluchshenko, O.; Kerschbaum, M.; Lagasio, M.; Mazzarella, V.; Milelli, M.; et al. Application of Severe Weather Nowcasting to Case Studies in Air Traffic Management. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temme, M.-M.; Gluchshenko, O.; Nöhren, L.; Kleinert, M.; Ohneiser, O.; Muth, K.; Ehr, H.; Groß, N.; Temme, A.; Lagasio, M.; et al. Innovative Integration of Severe Weather Forecasts into an Extended Arrival Manager. Aerospace 2023, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, M.; Cabello, À.; Russo, B. Flood damage assessment in urban areas. Application to the Raval district of Barcelona using synthetic depth damage curves. Urban. Water J. 2016, 13, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, L.; Sánchez, E.; Yagüe, C. Climatology of precipitation over the Iberian Central System mountain range. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 33, 2260–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halladay, K.; Kahana, R.; Johnson, B.; Still, C.; Fosser, G.; Alves, L. Convection-permitting climate simulations for South America with the met office unified model. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 61, 5247–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Sun, Q.; Hu, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, K.; Ye, X.; Huang, G.; Hu, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, Z. Investigating kinematics and triggers of slow-moving reservoir landslide using an improved MT-InSAR method. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2289835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, M.T.; Lemes, M.R.; Hart, N.C.; Halladay, K.; Kahana, R.; Fisch, G.; Prein, A.; Ikeda, K.; Liu, C. The added value of using convective-permitting regional climate model simulations to represent cloud band events over South America. Clim. Dyn. 2024, 62, 10543–10564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlakas, P.; Stathopoulos, C.; Flocas, H.; Bartsotas, N.S.; Kallos, G. Precipitation climatology for the arid region of the Arabian Peninsula—Variability, trends and extremes. Climate 2021, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimalt-Gelabert, M.; Alomar-Garau, G.; Martin-Vide, J. Synoptic Causes of Torrential Rainfall in the Balearic Islands (1941–2010). Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus-Canovas, M.; Lopez-Bustins, J.A.; Martín-Vide, J.; Halifa-Marin, A.; Insua-Costa, D.; Martinez-Artigas, J.; Trapero, L.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Cuadrat, J.M. Characterisation of Extreme Precipitation Events in the Pyrenees: From the Local to the Synoptic Scale. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Tejeda, E.; Llorente-Pinto, J.M.; Ceballos-Barbancho, A.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Azorín-Molina, C.; Alonso-González, E.; Revuelto, J.; Herrero, J.; López-Moreno, J.I. The significance of monitoring high mountain environments to detect heavy precipitation hotspots: A case study in Gredos, Central Spain. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 146, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleoni Reluy, N.; Hürlimann, M.; Lantada, N. How are public compensation efforts implemented in multi-hazard events? Insights from the 2020 Gloria storm in Catalonia. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 3483–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Castillo, S. Evolution of Radar and Lightning Variables in Convective Events in Barcelona and Surroundings for the Period 2006–2020. Adv. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C.; Esbrí, L. The Results of Applying Different Methodologies to 10 Years of Quantitative Precipitation Estimation in Catalonia Using Weather Radar. Geomatics 2021, 1, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, J.; Pineda, N.; Rigo, T.; Aran, M.; Amaro, J.; Gayà, M.; Arús, J.; Montanyà, J.; van der Velde, O. A Mediterranean nocturnal heavy rainfall and tornadic event. Part I: Overview, damage survey and radar analysis. Atmos. Res. 2011, 100, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, M.C.; Rodríguez, R.; Redaño, Á. Analysis of extreme rainfall in Barcelona using a microscale rain gauge network. Meteorol. Appl. A J. Forecast. Pract. Appl. Train. Tech. Model. 2010, 17, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasat-Botija, M.; Llasat, M.C.; Marinelli, D.; Marcos, R.; Guzzon, C.; Díaz, A. FLOODGAMA: The new INUNGAMA. Beyond a flood events database for Catalonia. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Farnell, C. A Comparison between Radar Variables and Hail Pads for a Twenty-Year Period. Climate 2024, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasat, M.C.; Marcos, R.; Turco, M.; Gilabert, J.; Llasat-Botija, M. Trends in flash flood events versus convective precipitation in the Mediterranean region: The case of Catalonia. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences. In International Geophysics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 100, p. 676p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Farnell, C. A comparative analysis between radar and human observations of the Giant Hail Event of 30 August 2022 in Catalonia. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Rigo, T.; Pineda, N. Lightning jump as a nowcast predictor: Application to severe weather events in Catalonia. Atmos. Res. 2017, 183, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, A.; Marcos, M.; Carrió, D.S.; Gomez-Pujol, L. Coastal impacts of Storm Gloria (January 2020) over the north-western Mediterranean. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Farnell Barqué, C. Evaluation of the radar echo tops in Catalonia: Relationship with severe weather. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C. Analysis of mesoscale convective systems in Catalonia using meteorological radar for the period 1996–2000. Atmos. Res. 2007, 83, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Berenguer, M.; del Carmen Llasat, M. An improved analysis of mesoscale convective systems in the western Mediterranean using weather radar. Atmos. Res. 2019, 227, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doswell, C.A.; Brooks, H.E.; Maddox, R.A. Flash Flood Forecasting: An Ingredients-Based Methodology. Weather. Forecast. 1996, 11, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnell, C.; Rigo, T.; Heymsfield, A. Shape of hail and its thermodynamic characteristics related to records in Catalonia. Atmos. Res. 2022, 271, 106098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrosov, S.Y.; Cifelli, R.; Gochis, D. Measurements of Heavy Convective Rainfall in the Presence of Hail in Flood-Prone Areas Using an X-Band Polarimetric Radar. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C. Forecasting hailfall using parameters for convective cells identified by radar. Atmos. Res. 2016, 169, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypka, P. Dynamic real-time volumetric correction for tipping-bucket rain gauges. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 271, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnolas, M.; Llasat, M.C. A flood geodatabase and its climatological applications: The case of Catalonia for the last century. En Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 7, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, N.; Soler, X.; Vilaclara, E. Aproximació a la Climatologia de Llamps a Catalunya: Anàlisi de les Dades de l’SMC per al Període 2004–2008. 2014. Available online: https://static-m.meteo.cat/wordpressweb/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/18130754/Nota_dEstudi_SMC_73_PRINT.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.