Abstract

Climate change brings significant challenges to developing countries whose primary livelihood is agriculture. Farmers are directly perceiving and being affected by climate change, and their correct perception of climate change is critical for choosing effective adaptation strategies. The purpose of this paper is to examine farmers’ perceptions of climate change and to analyze the factors that affect the accuracy of their perception. Taking Aohan Banner, Inner Mongolia, China, as a study area, we surveyed 630 farmers and 42 experts in 2021, the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change was measured by comparing it with meteorological data. Farmers and experts then ranked the impact of 12 meteorological disasters. Finally, the factors affecting farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change were analyzed by ordinal logistic regression. We determined the following: (1) Most farmers’ perceptions of temperature is that it is increasing, while their perception of precipitation is that it is decreasing, consistent with the meteorological data and most expert views. (2) Most farmers’ perceptions of wind speed is that it has increased, which is contrary to the meteorological data and most expert views. (3) Farmers’ perceptions of the impact degree of meteorological disasters is drought, then frost, and then rainstorms. This impact degree is different from expert opinions, but the perception of drought is the same, in that drought is considered to be the most severe meteorological disaster affecting farmers. (4) The years of farming, agricultural income, access to information via the Internet and television, and concern about climate change are positively correlated with farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. Based on our research, we suggest the following: (1) Take measures to deal with drought disasters, such as the rational development and use of water resources, adoption of water-saving measures, and cultivation of drought-resistant and cold-resistant herbs. (2) Improve farmers’ knowledge level through agricultural technology and climate knowledge education. (3) Strengthen the promotion and exchange of climate information.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a globally challenging problem that affects ecological, environmental, social, and economic sectors [1,2,3,4]. Among these impacts, climate change-induced meteorological disasters, such as cold waves, sandstorms, haze, fog, strong winds, mountain torrents, droughts, floods, hail, frost, snowstorms, and rainstorms [5,6,7,8], have brought some dire results for the agricultural industry especially in developing countries, seriously threatening the welfare and livelihoods of farmers [4,9,10,11]. The risks to agriculture include decreasing crop yields [12], increasing pest and disease pressure [13], water scarcity and irrigation challenges [14], changing growing seasons and phenology [15], and rising economic risk [16].

Climate change perception plays a pivotal role in shaping behaviors regarding climate change adaptation [17,18]. Climate change perception is defined as how people receive the new information conveyed by climate change through their senses and use their knowledge, experience, and values to organize, judge, and summarize the awareness, attitude, and understanding of the information from climate change [19,20]. For farmers, their perceptions of climate change affect their decision-making in agriculture [21,22], such as choosing plant varieties and adjusting farming practices to mitigate the effects of climate change [23,24,25]. Recent studies underscore the paramount importance of behavioral models for understanding decision-making processes related to climate adaptation and mitigation in land-based sectors, particularly agriculture [26]. Meanwhile, stakeholder co-creation approaches, such as those applied in coastal tourism systems, demonstrate that participatory processes can effectively enhance climate resilience [27]. When farmers are aware of the potential risks and challenges of climate change and meteorological disasters, they are more likely to make sensible choices to promote agricultural resilience and sustainability [28,29]. By correctly perceiving changes in the temperature, rainfall patterns, meteorological disasters, and extreme weather events, farmers can better assess the risks and adapt their strategies accordingly [30,31]. However, the wrong perception of climate change can lead to maladaptation in the implementation of adaptation measures [32]. Maladaptation refers to intentional adaptation actions that result in increased vulnerability or erode the preconditions for sustainable development [33].

To support well-informed decision-making and reduce the risk of maladaptation, providing actionable climate information through “climate services” is essential. The World Meteorological Organization (2011) [34] defines climate services as “the provision of climate information in a way that assists decision-making”. However, the successful development of these services faces numerous challenges. It requires not only advanced technical infrastructure but also intermediaries who can bridge the gap between data providers and end-users [35]. A key barrier in many regions, particularly in Africa, is the widespread absence of reliable historical climate and agricultural data, which hampers the comprehensive evaluation and customization of climate services [36]. Importantly, the effectiveness of any climate service is closely linked to how end-users, especially farmers, perceive climate change.

Currently, research on farmers’ perceptions of climate change primarily encompasses the following aspects: (1) Research on climate change perception and adaptation: Mahmood et al. (2021) [37] demonstrated that a correct climate risk perception can help to plan and implement adaptation strategies; Asrat and Simane (2018) [38] analyzed the perception and adaptation of farmers to climate change in the Dabus watershed in Ethiopia. (2) Comparison of climate change perception: Nisbet and Myers (2007) [39] summarized the public’s perception of the certainty of the science related to global warming and the extent of consensus among experts; Ayanlade et al. (2017) [40] compared farmers’ perceptions of climate change with meteorological data in Nigeria. (3) Research on influencing factors of climate change perception: Cao (2021) [41] found that gender, age, education level, and family size significantly impact climate change perception; Zhang et al. (2022) [42] revealed a significant positive correlation between education level, years of farming, cultivated land area, and agricultural income with farmers’ perceptions of climate change and meteorological disasters. Despite extensive research on the public’s perception of climate change, there is currently no standardized assessment tool for quantifying the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions regarding climate change. Moreover, the factors affecting the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change have not been systematically summarized. To fill these research gaps, we will enhance the quantitative accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change by comparing them with expert opinions and actual meteorological data. Simultaneously, we will systematically analyze various factors and their impact on farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change.

The objective of this study is to examine farmers’ perceptions of climate change and meteorological disasters and to analyze the factors influencing the accuracy of their perceptions of climate change. To achieve these objectives, we attempt to answer the following three research questions in this study: (1) Are farmers correct in their perceptions of climate change? (2) How do farmers perceive meteorological disasters? (3) What factors influence the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change? Our study can provide a quantitative basis for policy-makers in the region and provide farmers with scientific guidelines for tackling climate change for sustainable agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Details

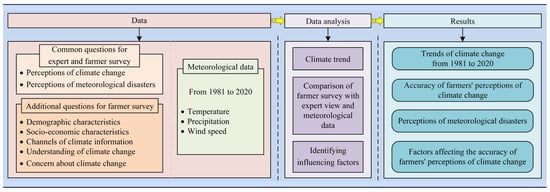

We conducted a questionnaire survey with 630 farmers on climate change perception in this study. The questionnaire items were designed based on the historical weather events of the research area and the literature review. We took Aohan Banner as a study area, a representative agricultural county in China that is seriously affected by climate change. In the survey results, the historical meteorological data (Xinhui Meteorological Station) were used to evaluate the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change. To understand the impact of meteorological disasters on farmers’ livelihoods, the order of impact severity was ranked and compared to farmers’ perceptions with experts’ opinions. Finally, ordinal logistic regression analysis was applied to examine the factors that affected farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research flow chart (We obtained data from three sources: farmer surveys, expert surveys, and meteorological data. Farmers and experts were asked common questions about climate change perceptions, and farmers were additionally asked questions about factors that affect climate change perceptions. The common questions are to compare the perceptions of farmers with the opinions of experts. We analyzed farmers’ perceptions of meteorological disasters and correct perceptions of climate change, and the factors that affect farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change were obtained. The meteorological data are from the Xinhui Meteorological Station).

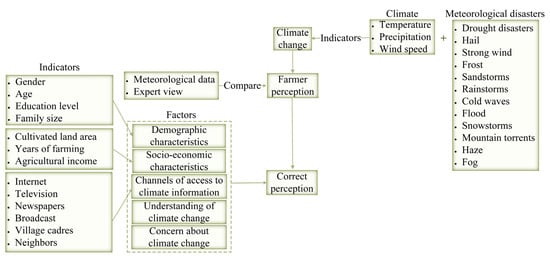

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Given that research site is characterized as arid and windy [43], temperature, precipitation, and wind speed were selected as indicators for assessing climate change perception [44,45]. Based on the historical weather events and the literature review, we selected 12 meteorological disasters, which are cold waves, sandstorms, haze, fog, strong wind, mountain torrents, drought disasters, floods, hail, frost, snowstorms, and rainstorms as important meteorological disasters affecting the region [5,6,7,8].

Farmers may fail to perceive climate change, leading to a lack of motivation to take action in addressing it [19]. Conversely, when farmers perceive climate change, they are more likely to take proactive measures [19]. However, if farmers have misconceptions about climate change, they may undertake inappropriate actions [32]. When farmers have correct perceptions of climate change, they are better equipped to adopt suitable and effective strategies to address climate change [30,31]. We assessed the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change by comparing them with the meteorological data.

Falaki et al. (2013) [46] demonstrated that age, gender, education level, and family size had a positive impact on farmers’ perceptions of climate change. Similarly, Ado et al. (2019) [18] found that farming experience and access to climate information significantly affect farmers’ perceptions of climate change. However, Ado et al. (2019) [18] reported a negative association between farm size and farmers’ perceptions of climate change. Additionally, Shi (2016) [19] identified household agricultural income as an important socio-economic factor affecting climate change perception and adaptation behavior. Jiang et al. (2021) [47] discovered that higher levels of attention to climate issues among farmers corresponded to a stronger perception of climate change.

According to the above studies, we determined that demographic characteristics [28], socio-economic characteristics [21], access channels to climate information [48], understanding of climate change, and concern about climate change [49] can influence farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. Among these, the demographic characteristics were gender, age, education level, and family size [41,42,46]. The socio-economic characteristics included cultivated land area, years of farming, and agricultural income [18,19,42]. The access channels to climate information included the internet, villagers’ collective meetings, television, newspapers, broadcast, village cadres, and neighbors [18,50].

Building upon the aforementioned theoretical background, this study developed a theoretical framework (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework.

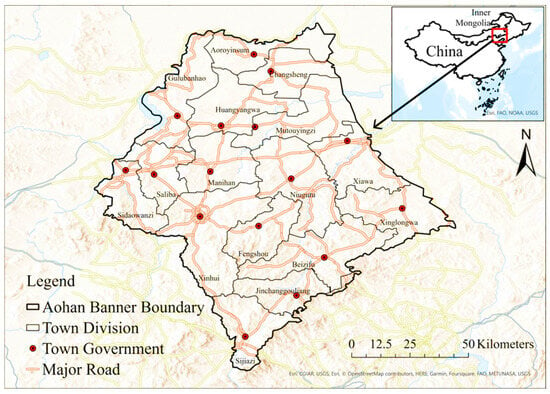

2.3. Research Site Description

Aohan Banner is located in the southeast of Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China (41°42′–42°02′ N, 119°30′–120°54′ E), with 16 towns, a total area of 8294 km2 [51], and an altitude range of 300–1250 m (Figure 3). The annual mean temperature is 7 °C. The region has a temperate semi-arid continental climate, with cold and dry winters and warm summers [52]. The annual precipitation ranges from 250 mm to 540 mm. The precipitation is mainly concentrated in summer [52]. According to the Chifeng Statistical Yearbook 2022 [51], the total population in 2021 was 595,743, of which 492,700 lived in rural areas. Aohan Banner is a national commodity grain base, where agriculture is the local leading industry, and most people are engaged in agriculture [43]. However, drought occurs frequently, and desertification has become increasingly severe, causing significant agricultural losses [43]. Climate change affects agriculture, livestock, and forestry in this region [43] and the livelihoods of the farmers who depend on them [53]. Aohan Banner is extremely sensitive to climate change, the adaptability of farmers to climate change is relatively weak, and the degree of livelihood vulnerability is high [43]. To better understand these climatic changes, we analyzed meteorological data for the period 1981–2020, which were provided by the Aohan Banner Meteorological Bureau of Inner Mongolia. The data originate from the Xinhui Meteorological Station (located in Xinhui Town at 42°31′ N, 119°90′ E) and include time series of the annual mean temperature, annual precipitation, and annual mean wind speed.

Figure 3.

Map of China including Inner Mongolia (on the top right side) and zoomed-in map of Aohan Banner (center)—study area.

2.4. Questionnaires of Farmers and Experts

In the survey, farmers and experts were asked about their perceptions of climate change and meteorological disasters, and the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change was evaluated by comparing it to the experts’ answers. In addition to the common questions asked to experts, questions were added to the farmers’ survey questions to identify factors that affect climate change perception. The details of the survey are as follows.

The common questions consisted of two parts. The first part is the perception of climate change. To find out farmers’ perceptions of climate change trends, farmers were asked: “How has the climate changed over the past decade (temperature/precipitation/wind speed)?” They were required to select one of three options: increase, decrease, or no change for each indicator. The second part is the perception of meteorological disasters. To find out the impact of these 12 meteorological disasters on farmers’ livelihoods, they were ranked according to the degree of impact. The survey question is “How have the following 12 meteorological disasters affected your livelihood?” (Rated on a scale of 12: 1 = low impact, 12 = high impact). Considering that survey subjects may not have the time and patience to rank all 12 meteorological disasters, it was essential to rank the top six items that had a serious impact on livelihoods to improve the completeness of the questionnaire.

The farmer questionnaire included the above common questions and specific questions for farmers. We designed questions that included the following four parts: (1) demographic characteristics of farmers; (2) socio-economic characteristics of farmers; (3) channels of access to climate information; (4) understanding of climate change; and (5) concern about climate change (Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

This study involved a non-invasive and anonymous questionnaire survey of adult farmers. Prior to the survey, all participants were clearly informed that the purpose of the study was solely for academic research. Participation was entirely voluntary, and the rights and privacy of the respondents were fully respected and protected. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the survey. No sensitive personal information or biological data were collected, and no minors or vulnerable populations were involved. All responses were anonymized and securely stored to ensure data confidentiality and security. The study was conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. We also adhered to the principles of transparency, honesty, and replicability throughout the research process to ensure the legitimacy, ethics, and credibility of the study.

At a 98% confidence level, a margin of error of 4–5% was set, and a sample size of 543 to 847 people was considered most appropriate [54]. We selected five towns representing the east, south, west, north, and central parts of Aohan Banner, encompassing a total of 63 administrative villages. Accordingly, 630 questionnaires were distributed in August, September, and October 2021, and 10 farmers were randomly sampled from each village for investigation. Of these, 34 invalid questionnaires that were answered incompletely because farmers did not understand the questions were removed from the data set, and the remaining 596 were valid for analysis, with an effective rate of 94.6%.

In the expert survey, 42 experts, 20 in meteorology and 22 in agriculture provided their views on the perceptions of climate change and meteorological disasters.

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Climate Trend

The historical meteorological data originate from the Xinhui Meteorological Station as a single source, which provides representative climatic data for the study area. Meteorological data from 1981 to 2020 were used to establish the long-term climatic trend. As per World Meteorological Organization (WMO) guidelines, a minimum 30-year period is required to define a climate norm and assess robust trends [55]. By the Independent Samples T-Test, we analyzed the annual mean temperature, annual mean precipitation, and annual mean wind speed of two 20-year periods (1981–2000 and 2001–2020) to find out the trend of climate change. The trend identified through this analysis served as the objective benchmark against which farmers’ perceptions were compared.

2.5.2. Comparison of Farmers’ Surveys with Meteorological Data and Expert Views

Using the meteorological data and the expert survey results, we analyzed the accuracy of farmers’ perceptions of climate change and the level of their perception of meteorological disasters. Among the three answers of increase, decrease, and no change in terms of temperature, precipitation, and wind speed, compared with the analysis results of the meteorological data trends, the correct answer is 1, and the wrong answer is 0. Then, the total number of correct perceptions for each farmer is calculated as the dependent variable.

Regarding the impact of meteorological disasters, first, the impact rating of each disaster was assigned: Highest impacting first-rank disaster = 12, second-rank disaster = 11, and so on, 12th-rank disaster = 1, unsorted disaster = 0 (Note: The first six items were mandatory; so, some items may not be sorted). Then, the final impact severity of each disaster was calculated by averaging. For comparison, the same calculation was performed on the data from experts.

2.5.3. Identifying the Factors Influencing Farmers’ Correct Perceptions of Climate Change

There are 15 variables that may affect farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change (Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials). In order to prevent the deviation of the results due to strong correlation between the variables, it was necessary to conduct correlation analysis.

Ordinal logistic regression analysis [56] was applied to analyze the factors affecting farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. The statistics package IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 [57] was used for the analysis. The model is shown in Equation (1) [58]:

where j is the number of farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change; i is the independent variable subscript; represents the occurrence probability of farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change; represents the independent variables, including X1–X15 (Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials); is the constant term; is the regression coefficient of each variable; is the error term.

3. Results

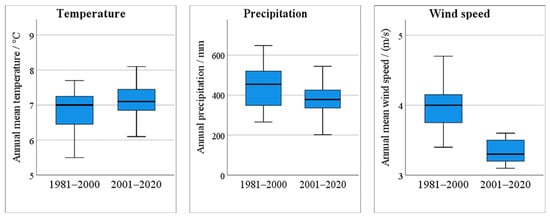

3.1. Trends of Climate Change from 1981 to 2020

The annual mean temperature from 2001 to 2020 (7.115 °C) was higher than that from 1981 to 2000 (6.805 °C), showing an increasing trend. The annual mean precipitation (380.675 mm) and annual mean wind speed (3.33 m/s) from 2001 to 2020 were lower than the annual precipitation (445.150 mm) and annual mean wind speed (3.98 m/s) from 1981 to 2000, respectively, showing a decreasing trend (Table 1).

Table 1.

Trends of annual mean temperature, annual mean precipitation, and annual mean wind speed from 1981 to 2020.

The comparison of the annual mean temperature, annual mean precipitation, and annual mean wind speed for the two 20-year data sets from 1981 to 2000 and 2001 to 2020 is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Annual mean temperature, annual mean precipitation, and annual mean wind speed in 1981–2000 and 2001–2020.

3.2. Characteristics of the Farmers Who Responded to the Survey

Among the 596 surveyed farmers, males and females accounted for 47.0% and 53.0% of the total sample. Farmers aged 40–49 and 50–59 were the largest proportion, accounting for 34.1% and 32.7% of the total farmers, respectively. The education level of junior high school accounted for 57.7%. Two-person and three-person households accounted for the largest proportion, with 38.8 and 27.3%, respectively. The average total household area of cultivated land was 30.05 Mu (1 Mu = 0.0667 ha). Agricultural experience exceeding 20 years was possessed by 59.7% of the farmers. The average annual agricultural income of farmers was 20,000–39,999 RMB and 40,000–59,999 RMB, accounting for the most significant proportion, with 26.8% and 22.1%, respectively. The main mediums to obtain climate information were television, neighbors, the internet, newspapers, broadcast, and village cadres, accounting for 74.7%, 73.2%, 71.5%, 67.8%, 66.8%, 59.2%, respectively. Farmers with a general understanding of climate change made up 38.9%. Less concern about climate change was expressed by 43.0% of farmers (Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials).

3.3. Accuracy of Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Change

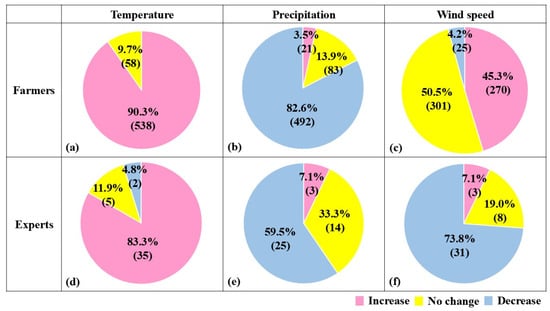

We found that the majority of farmers believed that the annual mean temperature had increased, and the annual precipitation had decreased, which is consistent with the majority of experts. However, half of the farmers believed the annual mean wind speed had not changed, while most experts thought it had decreased (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Farmers’ perception of changes in temperature (a), precipitation (b), and wind speed (c) compared with corresponding experts’ views (d–f). Colors represent the following: pink = increase, yellow = no change, blue = decrease. Numbers in parentheses indicate respondent counts.

Most farmers (90.3%) perceived that the annual mean temperature in Aohan Banner had increased, while 9.7% perceived no change, and none reported a decrease (Figure 5a). The majority of farmers (82.6%) perceived a reduction in annual precipitation, with 13.9% perceiving no change, and 3.5% noting an increase (Figure 5b). Regarding the annual mean wind speed, about half of the farmers (50.5%) believed there was no change, 45.3% perceived an increase, and 4.2% observed a decrease (Figure 5c). On the other hand, 83.3% of experts believed that the annual mean temperature in Aohan Banner had increased, with 11.9% thinking there was no change, and 4.8% perceiving a decrease (Figure 5d). In terms of annual precipitation, 59.5% of the experts noted a decrease, 33.3% perceived no change, and 7.1% observed an increase (Figure 5e). Concerning the annual mean wind speed, 73.8% of experts observed a decrease, 19.0% thought there was no change, and 7.1% perceived an increase (Figure 5f).

Compared with the meteorological data, the percentage of experts and farmers’ correct perceptions of temperature, precipitation, and wind speed is shown in Table 2. In total, 83.3% of experts and 90.3% of farmers believe that the annual mean temperature has increased, which is consistent with the trend of the meteorological data. Further, 59.5% of experts and 82.6% of farmers think that the annual mean precipitation has declined, which is consistent with the trend of the meteorological data. Finally, 73.8% of experts believe that the annual mean wind speed has declined, which is consistent with the trend of meteorological data. However, only 4.2% of farmers think that the annual mean wind speed has decreased.

Table 2.

Percentage of correct perceptions of temperature, precipitation, and wind speed by experts and farmers compared to meteorological data.

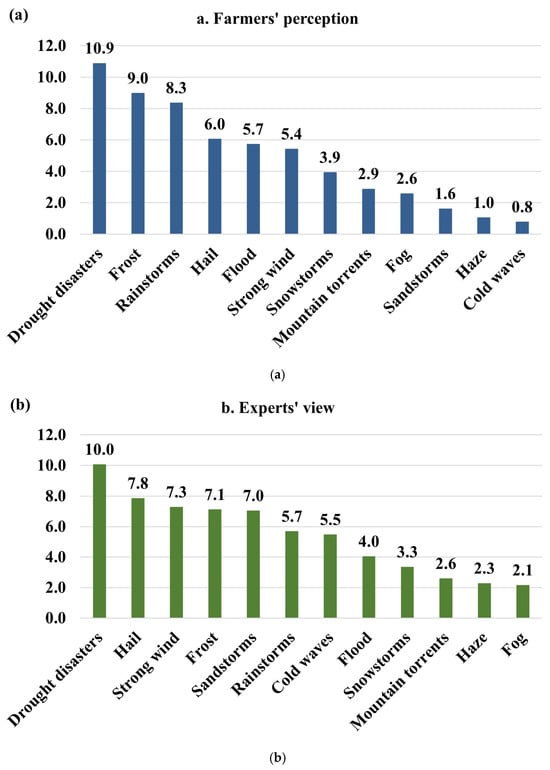

3.4. Perception of Meteorological Disasters

The severity of meteorological disasters that farmers perceived as affecting their livelihoods were drought disasters, frost, rainstorms, hail, flood, strong wind, snowstorms, mountain torrents, fog, sandstorms, haze, and cold waves, respectively (Figure 6a). According to the experts’ view (Figure 6b), the severity ranking of meteorological disasters was drought disasters, hail, strong wind, frost, sandstorms, rainstorms, cold waves, flood, snowstorms, mountain torrents, haze, and fog.

Figure 6.

Farmers’ (a) and experts’ (b) perception of meteorological disasters from 2010 to 2020 (note: the numbers represent the mean value of the impact severity calculated by farmers’ or experts’ perception of meteorological disasters).

Farmers thought drought, frost, and rainstorms were the worst meteorological disasters to affect their livelihoods, while experts pointed to drought, hail, and strong wind. Farmers and experts have reached an agreement that drought was the worst meteorological disaster. Farmers thought that fog, sandstorms, haze, and cold waves had little impact on farmers’ livelihoods. Similarly, experts agreed that haze and fog have little effect on farmers. Detailed comparisons are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ranking of meteorological disasters about farmers’ perception and experts’ view.

3.5. Factors Affecting Farmers’ Correct Perceptions of Climate Change

The correlation analysis of influencing factors is shown in Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials. If the Pearson correlation coefficient is greater than 0.7 and significant, it is considered to be correlated. It showed that “Broadcast (X9)” is related with “Television (X11)” and “Neighbors (X13)”; so, the variable of “Broadcast (X9)” was deleted. The other 14 variables were used as independent variables for ordinal logistic regression.

The model likelihood ratio test is used to analyze the effectiveness of the overall model. The analysis results are shown in Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials. The p value (0.000) is less than 0.05, indicating that the model is effective.

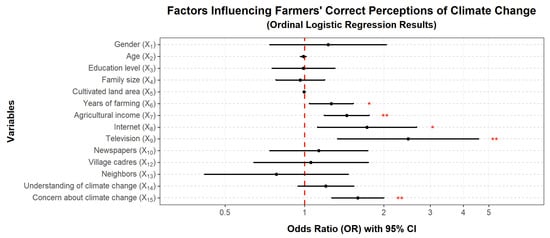

The results from the ordinal logistic regression analysis, as presented in Table S5 in the Supplementary Materials, unveil the factors influencing farmers’ accurate perceptions of climate change. The variables demonstrating significant effects on farmers’ accurate perceptions of climate change, ranked by significance (Figure 7), include agricultural income (p = 0.000), concern about climate change (p = 0.000), access to information through television (p = 0.004), access to information through the internet (p = 0.013), and years of farming (p = 0.017). These are the pivotal variables necessitating analysis in this paper. Notably, agricultural income (p = 0.000) and concern about climate change (p = 0.000) have the most significant impacts. Regarding the regression coefficient, television (0.904) holds the highest value, followed by the internet (0.546), concern about climate change (0.465), agricultural income (0.369), and years of farming (0.234).

Figure 7.

Ordinal logistic regression of factors associated with farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change (significance level: ** 1%, * 5%).

The regression coefficient for obtaining climate information through television stands at 0.904, indicating a positive influence on the correct perception of climate change. The corresponding odds ratio (OR value) of 2.470 signifies that, with each one-unit increase in obtaining climate information through television, there is a 2.470-times increase in the likelihood of having a correct perception.

Similarly, the regression coefficient for accessing climate information through the internet is 0.546, signifying a positive effect on the correct perception of climate change. The associated odds ratio of 1.727 implies that a one-unit increase in obtaining climate information through the internet leads to a 1.727-times increase in the odds of having a correct perception.

Climate change concern is also found to positively impact the correct perception of climate change, with a regression coefficient of 0.465. The odds ratio of 1.593 suggests that a one-unit increase in concern about climate change corresponds to a 1.593-times increase in the odds of having a correct perception.

Likewise, agricultural income is positively linked to the correct perception of climate change, supported by a regression coefficient of 0.369. The odds ratio of 1.446 indicates that a one-unit increase in agricultural income results in a 1.446-times increase in the odds of having a correct perception.

Finally, the regression coefficient for farming years is 0.234, reflecting a positive effect on the correct perception of climate change. The odds ratio of 1.264 means that a one-unit increase in farming years corresponds to a 1.264-times increase in the odds of having a correct perception.

4. Discussion

The study surveyed 630 farmers and 42 experts to measure the accuracy of their perceptions on climate change based on the meteorological data. The survey also included farmers’ and experts’ rankings of the impact of 12 meteorological disasters. Additionally, we conducted an ordinal logistic regression analysis to identify factors that influence farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. The results revealed some noteworthy findings, in that most farmers’ and experts’ perceptions of increasing temperatures and decreasing precipitation were consistent with the meteorological data. Interestingly, most farmers perceived an increase in wind speed, which was contrary to most expert opinions and the meteorological data. Meanwhile, although farmers and experts differed in their assessment of the impact severity of various meteorological disasters, both acknowledged drought as the most severe meteorological disaster affecting farmers’ livelihoods. The study found that the key factors affecting farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change were farming years, agricultural income, information access channels—the internet and television, and concern about climate change.

4.1. Analysis of Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Change

The experts’ correct perception of temperature, precipitation, and wind speed was 83.3%, 59.5%, and 73.8%, indicating that most experts’ perceptions of climate change were correct. However, it is worth noting that the correct perception of temperature and precipitation was lower than the 90.3% and 82.6% of farmers, respectively. Horn (2006) [59] shows that extensive professional knowledge and working memory help experts to have correct perceptions. However, the fact that farmers are more correct than experts here may be because experts rely mainly on data and expertise to perceive the climate, while farmers rely mainly on agricultural practices. Agricultural practices are more likely to give farmers a more accurate perception of climate change. This view is also supported by the consistency, whereby years of farming are positively correlated with correct perceptions.

Most farmers’ perceptions of temperature and precipitation were relatively accurate, but their perception of wind speed was not, which may be related to farmers’ inherent cognition of Aohan Banner’s climate. Aohan Banner is a typical arid grassland region [52,60], which is dry and windy all year round [61]; so, this may make farmers perceive the wind speed to be increased. At the end of 1978, the Chinese government made a major decision to implement the Three-North Shelter Forest Program, a large-scale human-planted windbreaking forest strip project built in the three northern areas of China (northwest, north, and northeast) to combat desertification, control sandstorms, and improve ecological conditions, which would take 73 years from 1979 to 2050 [62], and Aohan Banner participated in it [63]. Now meteorological data show that the wind speed is reduced, which may benefit from the Three-North Shelter Forest Program. However, the correct perception of wind speed has a positive impact on agriculture in avoiding natural disasters and taking effective measures [64]. When farmers accurately perceive the wind speed, they can better protect crops and effectively manage agricultural production, thus improving agricultural productivity. This requires farmers to possess some basic traits. For example, they usually need to have some knowledge of meteorology and climate, which can be acquired through relevant education. In addition, they need to be able to quickly access and trust reliable weather information and be sensitive to changes in weather conditions. The combination of these elements helps to improve the performance of farmers in agricultural decisions and practices, thus making agricultural production more efficient.

Our study design deliberately juxtaposed farmers’ decadal-scale experiential perceptions with a multi-decadal climatological trend. This comparison yields a critical insight: for climatic variables with strong monotonic trends (e.g., rising temperature, declining precipitation), even a decade of lived experience provides a reliable signal. In contrast, for variables with high interannual variability and strong episodic signatures, such as wind speed, short-term perception can be dominated by recent memorable events, leading to a significant divergence from the underlying long-term statistical trend. This cognitive bias towards salience and recency presents a fundamental challenge for climate communication: effective services must bridge the gap between statistical reality and experiential reality.

The marked discrepancy between farmers’ perception (predominantly ‘increased’ or ‘no change’) and the meteorological data showing a decrease in wind speed is a critical finding. Several interconnected factors may explain this: first, Aohan Banner has historically been characterized as a windy region [61]. This long-standing environmental identity may anchor farmers’ perceptions, making them less sensitive to gradual decreases over decades. Second, farmers’ perceptions are often shaped by memorable recent experiences. If the period preceding the survey included notable windy episodes, these could disproportionately influence their judgment. Third, as noted in the methodology limitation, farmers likely base responses on their lived experience (e.g., 10 years) rather than the full 40-year climatological record. Fourth, farmers may associate wind with its effects (e.g., soil erosion, sandstorms) rather than measuring the speed. Fifth, the single meteorological station data may not capture localized wind patterns experienced on individual farms.

This misperception has practical implications. If farmers believe the wind speed is increasing, they might undervalue the ecological benefits of windbreak forests. Targeted communication is needed to convey the success of ecological programs like the Three-North Shelter Forest Program.

4.2. Analysis of Farmers’ Perception of Meteorological Disasters

Riley (2008) [65] observed a disparity in the perception of environmental vulnerability between experts and farmers. Our research findings also indicated differences in the ranking of the severity of meteorological disasters between farmers and experts. This discrepancy may stem from the distinct reference points used by experts and farmers, with experts relying on data and farmers drawing from agricultural practices. Nevertheless, both experts and farmers concur that drought is the most serious meteorological disaster affecting farmers’ livelihoods. This is consistent with Li et al. (2018) [61] that drought and water shortage are significant limiting factors affecting agricultural development in Aohan Banner. The increasing lack of water resources has become an increasingly restrictive factor for regional social and economic growth [43]. With global warming, the effect of rising temperatures on agriculture is two-sided [20]. On the one hand, the rise in the temperature leads to the occurrence of drought; the growth of crops needs sufficient water, and a high temperature is not conducive to the development of crops and soil moisture retention. If irrigation is not conducted in time, the yield and quality of crops will be affected. On the other hand, the temperature rise provides favorable natural conditions for the growth and survival of temperature-loving crops. It is recommended that the government develop policies to deal with drought disasters to improve farmers’ livelihoods: (1) Rational development and utilization of water resources and water-saving measures. In arid areas, the government should formulate water resources management and protection policies, strengthen the allocation and utilization of water resources, and improve the construction and maintenance of water conservancy facilities. Additionally, the government may encourage farmers to adopt water-saving measures [61], such as drip irrigation and sprinkler irrigation, to reduce water waste and improve the water utilization efficiency. (2) Planting drought-resistant and cold-resistant herbs. The government may encourage farmers in arid areas to plant drought-resistant and cold-resistant herbs [61], such as astragalus, ginseng, and angelica, which can improve the productivity of the land, increase farmers’ income sources, and protect the ecological environment while adapting to climate change.

4.3. Analysis of Factors Affecting Farmers’ Correct Perception of Climate Change

The years of farming have a positive statistical significance on farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. The longer the years of farming, the more accurately farmers can perceive climate change. This is consistent with studies by Ayanlade et al. (2017) [40] and Asrat and Simane (2018) [38]. Mwadzingeni et al. (2023) [66] also revealed that agricultural experience is an important factor affecting farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change. The longer the years of farming, the more corresponding agricultural experience, with long-term agricultural experience accumulated by past and present agricultural and meteorological knowledge, affecting the level of climate change perception, to effectively respond to climate change risks [67]. Mwadzingeni et al. (2023) [66] showed that the length of irrigated farming experience has a significant impact on climate change perception. Due to the frequent occurrence of drought disasters in Aohan Banner, the high-efficiency water-saving irrigation technology of drip irrigation under film has been developed since 2011 [68]. Farmers can adapt effectively to climate change if they have experience in irrigated agriculture [69]. This suggests that farmers with more experience in irrigated agriculture are more resilient to climate change than less experienced farmers, because experienced farmers have the confidence and courage to make sound judgments [66,70]. Therefore, it is recommended that the government carry out agricultural skills training to increase farmers’ farming experience.

Agricultural income also has positive statistical significance on farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change, which is consistent with Xie et al. (2022) [71] and Zhang et al. (2022) [42]. Zhang et al. (2022) [42] showed a significant positive correlation between household agricultural income and the perceived impact of hail. Hasan and Kumar (2019) [72] revealed a significant correlation between farmers’ perceptions of climate change and their actual adaptation practices. From the studies, we conclude that the higher the agricultural income of farmers, the more correctly they can perceive climate change, and the more effective adaptive behaviors and practices they can adopt to cope with climate change. Moreover, to ease the constraints of farmers’ income on adaptive behavior, we also suggest that government should continue to increase agricultural investment in areas such as farmland protection subsidies, subsidies for the purchase of agricultural machinery, and free irrigation technology training [73].

Accessing climate information through the internet has a positive impact on the correct perception of climate change. Roco et al. (2015) [74] showed that obtaining climate information via the internet increased the possibility of climate change perception. With the increase in the use of mobile phones and internet penetration, farmers can quickly and accurately obtain climate information through the internet, which plays an important role in understanding climate change information. Therefore, promoting internet connectivity among farmers is a good strategy to improve farmers’ correct perception of climate change [74]

Obtaining climate information through television enables farmers to accurately perceive climate change, which is contrary to Hirons et al. (2018) [75], Chepkoech et al. (2018) [76], and Asare-Nuamah and Botchway (2019) [77]. Past studies have shown that these study areas (Ghana, Kenya, and Ghana) do not trust climate information from the media; so, access to climate information through television had little effect on farmers’ perception of climate change [77]. Aohan Banner has a high television penetration rate, and daily weather forecasts are provided through TV programs, allowing climate information to be obtained quickly and accurately. Therefore, television played an important role in improving farmers’ correct perception of climate change.

Concern about climate change has a significant impact on farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. The higher the farmers’ attention to climate, the stronger the awareness of observing climate change and, thus, the more accurate the perception of climate change. This is consistent with Jiang et al. (2021) [47], where the more farmers are concerned about climate change, they may obtain climate information in more ways, and to a certain extent, they may grasp more information about climate change. The higher the frequency with which farmers watch weather forecasts, the more timely and accurate their grasp of meteorological information becomes, strengthening their accurate perception of climate change. In addition, Shi et al. (2015) [78] showed that knowledge related to climate was crucial for public attention to climate change. Therefore, it is recommended that the government expand climate-related knowledge training to increase farmers’ attention to climate change. This initiative will help farmers more fully understand the impacts of climate change and increase their sensitivity to weather forecasts, allowing them to respond more effectively to changing meteorological conditions.

4.4. Significance and Limitations of the Research

This study has important research significance. It can help farmers more accurately perceive climate change and adjust planting strategies, thereby reducing economic losses. In addition, we also analyzed the factors that affect farmers’ accurate perceptions of climate change, which can provide effective policy recommendations for decision-makers to better address the challenge of climate change and achieve sustainable agricultural development. We believe that this study makes a significant contribution to the literature, because it forms a theoretical framework for farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change. It can provide a reference for strengthening farmers’ adaptability to climate change in similar rural areas globally.

However, this study has several limitations, which point to the following directions for future research. First, in the questionnaire design, we used temperature, precipitation, and wind speed as climate indicators and used increase, decrease, and no-change to represent climate change. This design is relatively simple. For wind speed in particular, it is often difficult to perceive changes, and even for experts, there can be a risk of misjudgment. Furthermore, the meteorological data used in this study were obtained from the Aohan Banner Meteorological Bureau (Xinhui Meteorological Station) and represent annual averages for the entire county from 1981 to 2020. However, such aggregated data may not fully reflect localized or heterogeneous climate trends within the study area, as temperature and precipitation can vary spatially due to topography and other local factors. Therefore, future research should consider incorporating more fine-grained meteorological data or conducting spatial analyses to better capture sub-regional climate variability and its influence on farmers’ perceptions.

Second, to balance data quality with practical survey constraints (e.g., minimizing respondent fatigue and ensuring completion rates), participants were asked to select and rank only the six most impactful disasters from the list of twelve. While this pragmatic approach secured reliable data on the highest-priority threats, the subsequent scoring method (whereby unranked items received a score of 0) may introduce a systematic distortion by conflating “less impactful” with “no impact”. Future studies could employ more nuanced methods, such as requiring a full ranking or using rating scales for each disaster, to mitigate this bias while addressing the challenge of respondent burden.

Third, the meteorological data used were derived from a single station (Xinhui) and represent county-level averages. However, Aohan Banner exhibits clear topographic variations from south to north [79], which can create microclimates. Farmers in different topographic settings may experience different climatic trends, which could explain some variation in perceptions [80,81]. Future research should explicitly incorporate topographic variables (e.g., elevation, slope position) into the analysis. Stratifying the sample or analysis by topographic zone could reveal how the terrain modulates both climate exposure and perception. Further refinement of topographic analysis would help to better understand regional differences in climate change perception, thereby providing more comprehensive guidance for policy-making.

Fourth, due to resource constraints, the survey could not comprehensively investigate the long-term evolution of farmers’ perceptions of climate change. Additionally, there is room to improve the coverage and representativeness of the sample. Future studies could focus on the following two areas: (1) Comprehensiveness and representativeness of data: increasing the sample size by interviewing more farmers and expanding the survey area to ensure broader coverage and better representativeness. (2) Long-term dynamic observation: conducting long-term observations and tracking to capture the evolution of farmers’ perceptions and changes in adaptation strategies, thereby improving understanding of the long-term impacts of climate change on farmers.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found that most farmers’ perception of temperature was that it was increasing, while their perception of precipitation was that it was decreasing, which is consistent with the meteorological data and most expert views. However, most farmers’ perception of wind speed was that it has increased, which is contrary to the meteorological data and expert opinions. In addition, farmers’ perception of meteorological disasters showed the following impact degree in order: drought, frost, rainstorms, hail, flood, strong wind, snowstorms, mountain torrents, fog, sandstorms, haze, and cold waves, which was slightly different from experts’ opinion, but the perception of drought is the same, in that drought is considered to be the most severe meteorological disaster affecting farmers. Finally, we found that the factors influencing farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change included the years of farming, agricultural income, access to information via the internet and television, and concern about climate change. These were positively correlated with farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change.

According to these findings, we suggest that the government should implement the following: (1) Mitigate drought disasters: for example, implement measures to address drought disasters, including the rational development and utilization of water resources; promote water-saving practices and technologies in agriculture to enhance water-use efficiency; and encourage farmers to cultivate drought-resistant and cold-resistant crops to reduce vulnerability to extreme weather conditions. (2) Enhance farmers’ climate knowledge and awareness: for example, provide training programs and workshops for farmers to improve their knowledge and skills in agricultural technology and climate change adaptation, and disseminate climate-related information and educational materials to raise farmers’ awareness of climate change and its potential impacts on agriculture. (3) Strengthen climate information dissemination: for example, establish and promote efficient channels (the internet, and television) for the dissemination of climate information to rural communities; foster communication and exchange platforms where farmers can access timely climate data and share their experiences and observations; and encourage the use of modern communication tools and technologies to ensure that climate information reaches farmers effectively. By implementing these strategies, the government could contribute to enhancing the resilience of farmers in Aohan Banner to the challenges posed by climate change and meteorological disasters.

Future work should leverage higher-resolution spatial climate data, extend sampling to broader geographic and socio-economic contexts, and adopt longitudinal approaches to monitor how perceptions and adaptations evolve over time.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos17010040/s1, Table S1: Definition of variables; Table S2: Descriptive characteristics of farmers; Table S3: Pearson correlation of influencing factors; Table S4: Model fitting information; Table S5: Influencing factors of farmers’ correct perceptions of climate change (ordinal logistic regression results).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript writing. Z.H. conceived the idea, designed the study, and wrote the original draft; Y.-C.Y. contributed to the manuscript review and editing; X.Y. collected and analyzed meteorological data; Y.L. and H.C. jointly supervised and guided this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant, funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1A4A1025553 and No. RS-2023-00277059).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the 42 experts for sharing their knowledge with our study. We express our gratitude to Seunguk Kim and Jumi Cha for their contributions to creating the map and research flow chart. Additionally, we would like to thank all the respondents who diligently completed the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Adger, W.N.; Arnell, N.W.; Tompkins, E.L. Successful adaptation to climate change across scales. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Balogun, A.-L.; Setti, A.F.F.; Mucova, S.A.; Ayal, D.; Totin, E.; Lydia, A.M.; Kalaba, F.K.; Oguge, N.O. The influence of ecosystems services depletion to climate change adaptation efforts in Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.; Recha, J.; Ambaw, G.; MacSween, K.; Solomon, D.; Wollenberg, E. Assessment of agricultural emissions, climate change mitigation and adaptation practices in Ethiopia. Clim. Policy 2022, 22, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Xue, C. Study on the risk evaluation technologies of main agrometeorological disasters and their application. J. Nat. Resour. 2003, 18, 692–703. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Lou, X.; Wang, J. Influence of agricultural meteorological disasters on output of crop in China. J. Nat. Disasters 2007, 16, 37–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, N. Meteorological disaster trend analysis in China: 1949–2013. J. Nat. Resour. 2014, 29, 1520–1530. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y. Study on the problems and countermeasures of the development of atmospheric control industry under the influence of haze. Environ. Dev. 2019, 5, 46–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, P.; Kotani, K.; Managi, S. How do farm size and perceptions matter for farmers’ adaptation responses to climate change in a developing country? Evidence from Nepal. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Moqadas, R.S. Assessing rural households’ resilience and adaptation strategies to climate variability and change. J. Arid Environ. 2021, 184, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Khan, S.; Ma, X. Climate change impacts on crop yield, crop water productivity and food security–A review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilas, C.; Goebel, F.-R.; Babin, R.; Avelino, J. Tropical crop pests and diseases in a climate change setting—A few examples. In Climate Change and Agriculture Worldwide; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, G.; Neocleous, D.; Christou, A.; Kitta, E.; Katsoulas, N. Implementing sustainable irrigation in water-scarce regions under the impact of climate change. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, A.; Janssens, I.A.; Fu, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, L.; Lian, X.; Shen, M.; Zhu, X. Plant phenology and global climate change: Current progresses and challenges. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1922–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Meza, L.E. Adaptive capacity of small-scale coffee farmers to climate change impacts in the Soconusco region of Chiapas, Mexico. Clim. Dev. 2015, 7, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Dessai, S.; Goulden, M.; Hulme, M.; Lorenzoni, I.; Nelson, D.R.; Naess, L.O.; Wolf, J.; Wreford, A. Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Clim. Change 2009, 93, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, A.M.; Leshan, J.; Savadogo, P.; Bo, L.; Shah, A.A. Farmers’ awareness and perception of climate change impacts: Case study of Aguie district in Niger. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. Research progress in public perception and adaption behavior of climate change. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2016, 36, 258–264. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. A Study on the Livelihood Resilience of the Households Under Climate Disasters in the Loess Plateau—Based on Apple Households Survey. Master’s Thesis, Northwest Agriculture & Forestry University, Xianyang, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M.; Shrestha, R.P.; Datta, A. Comparing farmers’ perceptions of climate change with meteorological data in three irrigated cropping zones of Punjab, Pakistan. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2121–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A. Riders under storms: Contributions of nomadic herders’ observations to analysing climate change in Mongolia. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, G.; Mijatović, D.; Rojas, W.; Flores, J.; Pinto, M.; Mamani, G.; Condori, E.; Hilaquita, D.; Gruberg, H.; Padulosi, S. Climate change and crop diversity: Farmers’ perceptions and adaptation on the Bolivian Altiplano. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 703–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos Carlos, S.; da Cunha, D.A.; Pires, M.V.; do Couto-Santos, F.R. Understanding farmers’ perceptions and adaptation to climate change: The case of Rio das Contas basin, Brazil. GeoJournal 2020, 85, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierros-González, I.; López-Feldman, A. Farmers’ perception of climate change: A review of the literature for Latin America. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 672399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Alexander, P.; Holzhauer, S.; Rounsevell, M.D. Behavioral models of climate change adaptation and mitigation in land-based sectors. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2017, 8, e448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boqué-Ciurana, A.; Saladié, Ò.; Rovira-Soto, M.T.; Garcia-Lozano, C.; Martí, C.; Tonda, M.; Borràs, G.; Aguilar, E. How Can Stakeholder Co-Creation Foster Climate-Resilient Coastal Tourism Through Integrated Management of Climate, Water-Energy, and Beach-Dune Systems? Sustainability 2025, 17, 10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Cao, Z.; Shi, X. Comparison of farmers’ climate change perceptions with measured data and influencing factors—A case study of farmers in the Loess Plateau of northern Shaanxi. Geogr. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 161–166. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Geographical indication agricultural products, livelihood capital, and resilience to meteorological disasters: Evidence from kiwifruit farmers in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 65832–65847. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deressa, T.T.; Hassan, R.M.; Ringler, C.; Alemu, T.; Yesuf, M. Determinants of farmers’ choice of adaptation methods to climate change in the Nile Basin of Ethiopia. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshuka, A.; van Ogtrop, F.F.; Sanderson, D.; Thomas, E.; Neef, A. Vulnerabilities shape risk perception and influence adaptive strategies to hydro-meteorological hazards: A case study of Indo-Fijian farming communities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.D.; Mildenberger, M.; Marlon, J.R.; Leiserowitz, A. Geographic variation in opinions on climate change at state and local scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhola, S.; Glaas, E.; Linnér, B.-O.; Neset, T.-S. Redefining maladaptation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 55, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Climate Knowledge for Action: A Global Framework for Climate Services–Empowering the Most Vulnerable, Report of the High-Level Taskforce for the Global Framework for Climate Services; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buontempo, C.; Hutjes, R.; Beavis, P.; Berckmans, J.; Cagnazzo, C.; Vamborg, F.; Thépaut, J.-N.; Bergeron, C.; Almond, S.; Amici, A.; et al. Fostering the development of climate services through Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) for agriculture applications. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2020, 27, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tall, A.; Coulibaly, J.Y.; Diop, M. Do climate services make a difference? A review of evaluation methodologies and practices to assess the value of climate information services for farmers: Implications for Africa. Clim. Serv. 2018, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Arshad, M.; Mehmood, Y.; Shahzad, M.F.; Kächele, H. Farmers’ perceptions and role of institutional arrangements in climate change adaptation: Insights from rainfed Pakistan. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrat, P.; Simane, B. Farmers’ perception of climate change and adaptation strategies in the Dabus watershed, north-west Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2018, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, M.C.; Myers, T. The polls—Trends: Twenty years of public opinion about global warming. Public Opin. Q. 2007, 71, 444–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanlade, A.; Radeny, M.; Morton, J.F. Comparing smallholder farmers’ perception of climate change with meteorological data: A case study from southwestern Nigeria. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2017, 15, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z. Climate Change Perception and Adaptation Behavior of Farmers in Dry Farming Area of Northern Shaanxi Province. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, X. Research on walnut planters’ perception of climate change and meteorological disasters in Shangluo city. South-Cent. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 43, 5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, X. Impact of climatic and geological conditions on the industry structure of agriculture, forestry, and animal husbandry in Aohan Banner. Mod. Agric. 2016, 12, 92–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dhanya, P.; Ramachandran, A. Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and the proposed agriculture adaptation strategies in a semi arid region of south India. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2016, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kamruzzaman, M. Farmers’ perceptions on climate change: A step toward climate change adaptation in Sylhet Hilly Region. Univers. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 3, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaki, A.; Akangbe, J.; Ayinde, O.E. Analysis of climate change and rural farmers’ perception in north central Nigeria. J. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 43, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wu, X.; Pan, Y.; Lan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S. Farmers’ perception of climate change and its influencing factors in mountainous areas of northern Guangdong. Rural Econ. Sci.-Technol 2021, 32, 3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ruth, K.; Wemali, E.C.; James, K.; Boaz, W.; Innocent, N. Small scale farmers perception of institutions and information channels on climate change and adaptation, Embu County, Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 17, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, H.; Larcher, M.; Schönhart, M.; Stöttinger, M.; Schmid, E. Exploring farmers’ climate change perceptions and adaptation intentions: Empirical evidence from Austria. Environ. Manag. 2019, 63, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yegbemey, R.N.; Egah, J. Reaching out to smallholder farmers in developing countries with climate services: A literature review of current information delivery channels. Clim. Serv. 2021, 23, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chifeng, S.B. Chifeng Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Qin, F.; Jiang, L.; Yao, X. Vertical distribution of soil organic carbon content and its influencing factors in Aohan, Chifeng. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 345–354. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Funk, C.; Sathyan, A.R.; Winker, P.; Breuer, L. Changing climate-changing livelihood: Smallholder’s perceptions and adaption strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 259, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Youn, Y.-C.; Kim, S.; Choe, H. Improving farmer livelihood resilience to climate change in rural areas of Inner Mongolia, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. WMO Guidelines on the Calculation of Climate Normals; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Koletsi, D.; Pandis, N. Ordinal logistic regression. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Zhao, S. Analysis of immigrants’ satisfaction degree in water quality—Empirical research of ordinal logistic regression. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2018, 27, 1454. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Horn, C. How experience affects perception in expert decision-making. Perception 2006, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H. The Application of 3S Technology in Returning Farmland to the Forest (Grassland) in the County Area—Taking Chifeng City Aohan Banner as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2008. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Li, X.; Chu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Yu, L. Discussion on influencing factors and techniques of afforestation in arid area of Aohan Banner. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2018, 20, 166–168. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zhou, Y. Present situation and development countermeasures of shelter forest system in three north areas. For. Investig. Des. 2022, 51, 18–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Liu, Z.; Chang, W.; Ai, Z. Green hope—A memorial to the construction of Aohan Banner Three-North Shelterbelt Forest. J. Inn. Mong. For. 2021, 4, 4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Xu, C.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y. Analysis of main agrometeorological disasters and preventive measures in Zhuozhou. Mod. Rural Sci. Technol. 2023, 9, 100+124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Riley, M. Experts in their fields: Farmer—Expert knowledges and environmentally friendly farming practices. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwadzingeni, L.; Mugandani, R.; Mafongoya, P.L. Perception of climate change and coping strategies among smallholder irrigators in Zimbabwe. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; King, N.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Pearce, T.; McDowell, G.; Harper, S.L. The resilience of indigenous peoples to environmental change. One Earth 2020, 2, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q. Countermeasures and suggestions for winter and spring drought in Aohan Banner, Inner Mongolia. Drought Prev. Mitig. 2015, 3, 36–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli, J.; Eakin, H.; Chhetri, N. Small irrigation users’ perceptions of environmental change, impacts, and response in Nepal. Clim. Dev. 2021, 13, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Scheffran, J.; Schneider, U.A.; Elahi, E. Farmer perceptions of climate change, observed trends and adaptation of agriculture in Pakistan. Environ. Manag. 2019, 63, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Ding, W.; Ye, W.; Deng, Z. Agro-pastoralists’ perception of climate change and adaptation in the Qilian mountains of northwest China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.K.; Kumar, L. Comparison between meteorological data and farmer perceptions of climate change and vulnerability in relation to adaptation. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Shi, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Li, H. The farmers’ perception of climate change and diversity of adaptive behavior in day farming region. J. Shaanxi Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 48, 116–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Roco, L.; Engler, A.; Bravo-Ureta, B.E.; Jara-Rojas, R. Farmers’ perception of climate change in mediterranean Chile. Reg. Environ. Change 2015, 15, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirons, M.; Boyd, E.; Mcdermott, C.; Asare, R.; Morel, A.; Mason, J.; Malhi, Y.; Norris, K. Understanding climate resilience in Ghanaian cocoa communities–advancing a biocultural perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 63, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkoech, W.; Mungai, N.W.; Stöber, S.; Bett, H.K.; Lotze-Campen, H. Farmers’ perspectives: Impact of climate change on African indigenous vegetable production in Kenya. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2018, 10, 551–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare-Nuamah, P.; Botchway, E. Comparing smallholder farmers’ climate change perception with climate data: The case of Adansi north district of Ghana. Heliyon 2019, 5, e03065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Public perception of climate change: The importance of knowledge and cultural worldviews. Risk Anal. 2015, 35, 2183–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Spatial-Temporal Variability of Soil Organic Carbon in Aohan County, Chifeng; Inner Mongolia Agricultural University: Hohhot, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. Study on Farmers’ Perceptions and Adaptive Behaviors to Climate Change in the Hilly and Gully Area of Northern Shaanxi; Shaanxi Normal University: Xi’an, China, 2018. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kichamu, E.A.; Ziro, J.S.; Palaniappan, G.; Ross, H. Climate change perceptions and adaptations of smallholder farmers in eastern Kenya. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2663–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.