Abstract

Bacterial and viral diseases significantly reduce soybean (Glycine max) yield and quality. RNA modifications, particularly N6-methyladenosine (m6A), are increasingly recognized as having a regulatory role in plant–pathogen interactions, but the m6A methylome of soybean during viral and bacterial infection has not yet been characterized. Here, we performed transcriptome sequencing and MeRIP-seq (methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing) of soybean leaves infected with Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) and/or Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg). In general, m6A peaks were highly enriched near stop codons and in 3′-UTR regions of soybean transcripts, and m6A methylation was negatively correlated with transcript abundance. Multiple genes showed differential methylation between infected and control plants: 1122 in Psg-infected plants, 539 in SMV-infected plants, and 2269 in co-infected plants; 195 (Psg), 84 (SMV), and 354 (Psg + SMV) of these transcripts were both differentially methylated and differentially expressed. Interestingly, viral infection was predominantly associated with hypermethylation and downregulation, whereas bacterial infection was predominantly associated with hypomethylation and upregulation. GO and KEGG enrichment analysis revealed shared processes likely affected by changes in m6A methylation during bacterial and viral infection, including ATP-dependent RNA helicase activity, RNA binding, and endonuclease activity, as well as specific processes affected by only one pathogen. Our findings shed light on the role of m6A modifications during pathogen infection and highlight potential targets for epigenetic editing to increase the broad-spectrum disease resistance of soybean.

1. Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.) is a major crop that provides 44% of the plant-derived protein and 27% of the oil for the global food market (www.soystats.com). However, soybean production is significantly affected by diseases caused by viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens, which reduce both yield and quality [1]. Viral infections are particularly debilitating owing to their rapid spread and ability to manipulate host cellular machinery. Soybean mosaic virus (SMV), one of the most prevalent viral pathogens affecting soybean production, belongs to the Bean common mosaic virus lineage of potyviruses and has been widely studied because of its severe economic impacts [2]. Bacterial leaf spot is a common epidemic disease in soybean production that can significantly reduce yield. It is caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg), a member of the genus Pseudomonas [3]. Understanding the mechanisms by which SMV and Psg infect soybean, as well as the strategies by which plants respond to these infections, is crucial for the development of resistant cultivars.

Although a number of genes have been identified as critical for viral disease resistance, the regulatory roles of RNA modifications, particularly N6-methyladenosine (m6A), are increasingly recognized [4]. m6A is the most common internal RNA modification in higher eukaryotes [5], accounting for ~80% of RNA methylation modifications and ~50% of the methylated nucleotides in polyadenylated mRNA [5,6]. m6A modifications have been found across diverse organisms, including mammals, plants, yeast, and viruses with a nuclear replication phase [7]. Initially thought to be static and irreversible, m6A modifications are now understood to be dynamically regulated by proteins such as the RNA demethylase FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein) and to be crucial for the regulation of gene expression [8]. The m6A consensus motif, RRACH (R = A or G; H = A, U, or C), is enriched in long exons, near stop codons, and in 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTRs) [9,10].

m6A modifications function as part of a dynamic network of methyltransferases (writers), demethylases (erasers), and binding proteins (readers) [11]. The writer function is provided by members of the 70-kD S-adenosylmethionine-binding subunit methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) family [12]. METTL3 proteins identified in Arabidopsis thaliana include the two METTL3 orthologs MTA and MTB, FK506-binding protein 12 (FKBP12)-interacting protein 37 (FIP37, an ortholog of Wilms tumor 1-associated protein), VIRLIZER (VIR), and HAKAI [13,14,15]. The eraser function is performed by demethylases that remove the m6A modification, which are encoded by the AlkB homolog (ALKBH) gene family [16]. Three ALKBH proteins have been identified in plants to date: ALKBH9B [17], ALKBH10B [18], and SLALKBH2 [19]. The reader function is provided by YTH-domain-containing (YTHDC) proteins or eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) [20,21]. YTHDC proteins recognize m6A-modified mRNAs and include EVOLUTIONARILY CONSERVED C-TERMINAL REGION 2 (ETC2), ETC3, and ETC4 in Arabidopsis [22]. Together, writer, eraser, and reader proteins fine-tune gene expression networks by dynamically adding, removing, and interpreting m6A marks in order to influence downstream processes such as mRNA stability and translation [23].

The development of methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (MeRIP-seq) has enabled the identification of transcriptome-wide m6A modifications. m6A modifications have even been found in viral RNAs, where they enable the virus to avoid detection by host innate immunity and thus promote successful viral infection [24]. One recent study characterized the dynamics of m6A modification in rice during infection by Rice stripe virus or Rice black-streaked dwarf virus [25], and another showed that m6A is associated with transcriptionally active genes in early-diverging fungal lineages [26].

Because soybean is an ancient polyploid species, its gene expression mechanisms are particularly complex [27]. In this study, we used MeRIP-seq and transcriptome analyses to characterize m6A modification levels in soybean during infection by SMV and/or Psg the causative agent of bacterial blight. Specifically, we aimed to characterize the distribution of m6A peaks in the soybean genome during viral and bacterial infections and to identify genes whose m6A modifications were altered in response to both infections or were specific to one pathogen. The results of this study provide valuable genetic resources for soybean resistance breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The soybean cultivar Williams 82 (W82), used as the soybean reference genotype, is susceptible to SMV and bacterial blight [28,29]. W82 seeds were planted in pots and grown in a greenhouse at Northeast Agricultural University (Harbin, Heilongjiang, China) under controlled conditions (16 h light/8 h dark). Plants were supplied with regular fertilizer and supplementary lighting as needed.

2.2. Inoculation and Sample Collection

Inoculation of SMV: SMV-infected leaves were ground to extract virus-containing sap, to which carborundum was added. The mixture was then stored at low temperature. When the second trifoliate leaf of the soybean plant was fully expanded, inoculation was performed. The carborundum-containing sap was evenly sprayed onto the leaf surface and gently rubbed by hand to facilitate entry of the virus. The mechanical friction caused by the carborundum abraded the epidermal layer, allowing the virus to penetrate the leaf tissue. Following inoculation, the leaf surface was rinsed with water to remove residual sap [30]. Inoculation was performed on three plants exhibiting uniform growth, and three biological replicates were ensured.

Inoculation of Psg: A pre-prepared medium consisting of 50 mL NYGB medium and 50 μL carbenicillin was used. A total of 500 μL of Psg bacterial suspension was added and mixed thoroughly. The culture was incubated on a shaker at 220 rpm and 28 °C for 12 h. After incubation, the culture was transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube, balanced with an equal mass of water, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 25 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 4 mL MgCl2. After washing, the OD600 was adjusted to 0.8. Inoculation was carried out when the second trifoliate leaf was fully expanded. Trifoliate leaves with similar growth status were selected. The bacterial suspension was sprayed onto the abaxial (underside) leaf surface using an electric high-pressure spray gun, avoiding the main vein. Inoculation was considered complete when the leaf surface at the inoculation site appeared wet and water-soaked, while over-inoculation was avoided to prevent leaf damage [31]. Three biological replicates were ensured.

2.3. Confirmation of Infection by PCR and RT–PCR

Seven days after inoculation, total RNA was extracted from leaves inoculated with SMV alone and from those inoculated with both SMV and Psg. The extracted RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) with primers SMV-CPF and SMV-CPR. Similarly, seven days after inoculation, total DNA was extracted from leaves inoculated with Psg alone and from those inoculated with both SMV and Psg. The extracted DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification using primers 27F and 1492R.

2.4. Total RNA Extraction and mRNA Isolation

Total RNA was extracted and purified using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantity, purity, and quality were evaluated using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA) and a Bioanalyzer 2100 instrument (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). mRNA was purified from 50 μg of total RNA using Oligo-dT beads (Thermo Fisher, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and then fragmented using the Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (NEB, cat. New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA, Cat. No. E6150).

2.5. m6A Immunoprecipitation and cDNA Library Construction

Cleaved RNA fragments from each sample were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with an m6A-specific antibody (No. 202003, Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 750 mM NaCl, and 0.5% [v/v] Igepal CA-630). Protein-A-conjugated beads were added for further incubation (2 h, 4 °C). After washes to remove nonspecifically bound components, fragments were eluted using IP elution buffer (6.7 mM N6-methyladenosine). Immunoprecipitated RNA (IP group) and input RNA (Input group) were reverse transcribed to generate cDNA libraries using SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The average insert length before paired-end library construction was 100 ± 50 bp. Illumina libraries were prepared using a previously established protocol [32].

2.6. High-Throughput MeRIP-Seq and RNA-Seq

High-throughput sequencing was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform at LC-Bio Technology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) according to the vendor’s recommended protocol. Raw m6A-seq and RNA-seq data were cleaned using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/, accessed on 18 December 2022) to remove adapter contamination, low-quality bases, and ambiguous bases.

2.7. Analysis of Genome-Wide m6A Modifications

We analyzed the basic RNA-seq datasets using our previous protocol with some modifications [33]. Clean IP and Input reads from the Mock, SMV, Psg, and SMV + Psg groups were mapped to the soybean reference genome [34] (Glycine max, Wm82.a4.v1), guided by transcript annotations, using HISAT2.21 [35]. Read numbers were counted with Htseq-count [36]. Values of fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM) were calculated using the Cufflinks programs Cuffcompare and Cuffdiff 2.2.1 with global normalization parameters [37]. Fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM) were used to quantify transcript abundance. Differentially modified m6A peaks (DMPs) and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between treatments were identified based on the criteria |log2(fold change)| > 1 and p < 0.05 [38].

2.8. Analysis of m6A Peaks and Enriched Motifs

Mapped reads from the IP and Input libraries were analyzed using exomePeak 1.18.0 to identify m6A peaks [39]. Peaks were defined as regions where read coverage in the IP library was significantly higher than in the Input library. Identified peaks were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer 2.16.0 (IGV, http://www.igv.org, accessed on 18 December 2022). Motif analysis of peak regions was conducted using MEME 5.5.4 (http://meme-suite.org, accessed on 18 December 2022) for de novo motif discovery and HOMER 4.11 for known motif identification, based on peak localization [40,41]. Identified peaks were annotated according to their overlap with gene architecture using ChIPseeker 1.34.0 [42].

2.9. Statistical Analysis and Data Visualization

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA or independent t-tests (p < 0.05) in SPSS 17.0 (IBM) and Microsoft Excel (version 2019). Bar plots were created using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), and statistical visualizations were performed using R (https://www.r-project.org/, accessed on 18 December 2022). Some images were produced using FigDraw2.0 (https://www.figdraw.com/#/, accessed on 16 December 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Growth of Soybean Seedlings After Infection by SMV and Psg

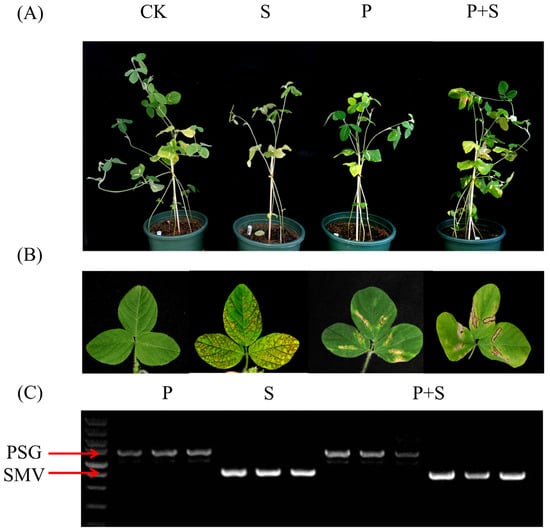

Psg-inoculated plants displayed different symptoms, including water-soaked lesions with necrotic margins (Figure 1B). Unlike the widespread chlorosis in SMV-inoculated plants, chlorosis in Psg-inoculated plants was limited to the inoculation site, and no obvious lesions were observed along the veins (Figure 1B). These plants also exhibited reduced plant height (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Soybean seedlings infected with Soybean mosaic virus (SMV) and Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg). (A) Growth of representative W82 soybean plants from the control (CK), SMV (S), Psg (P), and Psg + SMV (P + S) treatment groups. (B) Representative W82 soybean leaves from the CK, S, P, and P + S treatment groups. (C) SMV and Psg infections were confirmed in replicate seedlings by PCR and RT–PCR using primers targeting the SMV coat protein and the bacterial 16S ribosomal gene, respectively.

Symptoms characteristic of both pathogens were present in co-inoculated plants: necrotic veins, prominent vein-associated lesions, and water-soaked lesions (Figure 1A,B). Notably, viral symptoms were less severe in co-infected plants than in plants infected with SMV alone, and the number of branches was not reduced. These observations suggest potential interactions between the two pathogens.

To confirm Psg infection, DNA was extracted from infected leaves and subjected to PCR using universal primers (27F and 1492R) for the bacterial 16S ribosomal gene (Figure 1C). To confirm SMV infection, RNA was extracted from the same samples, reverse transcribed, and analyzed by PCR with SMV-specific primers SMV-CPF and SMV-CPR (Figure 1C).

3.2. Patterns of m6A Methylation in the Soybean Leaf Transcriptome

m6A modification plays a crucial role in host responses to microbial infections, and both viruses and bacteria have been reported to alter m6A RNA methylation patterns in their hosts [43,44]. We therefore performed MeRIP-seq to characterize changes in the m6A RNA methylome of soybean leaves infected with SMV (S), Psg (P), or both pathogens (P + S).

Leaf samples (with three replicates) from four experimental groups—CK, P, S, and P + S—each with three biological replicates, were subjected to m6A immunoprecipitation. Antibody-enriched fractions were designated as the IP group, while the non-immunoprecipitated fractions served as the Input group. After quality control, we obtained approximately 50 Mb of clean reads per sample; Q30% values ranged from 93.48% to 94.93% per sample, indicating the high quality of the sequencing data (Table S1).

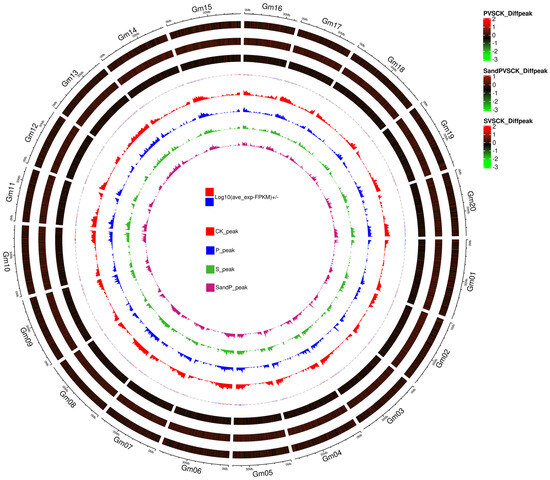

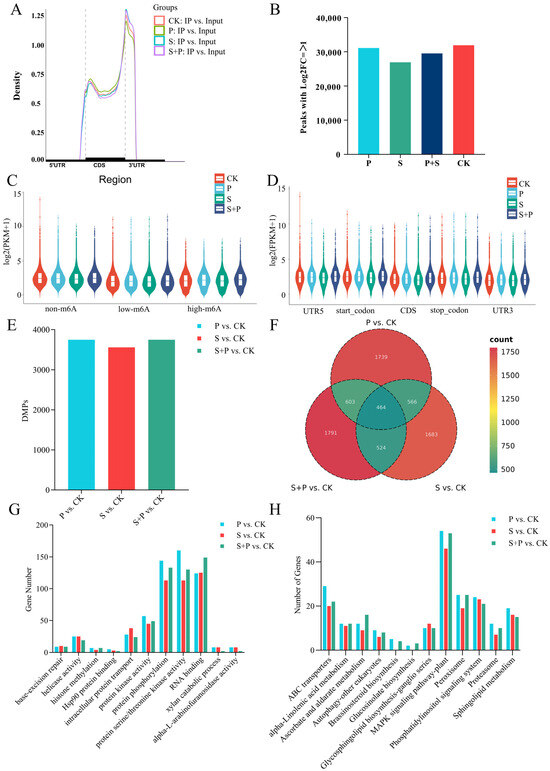

Distinct patterns of m6A modification were observed at both the genome and transcript levels. At the genome level, m6A peaks were highly concentrated near chromosomal telomeres, consistent with gene density (Figure 2). At the transcript level, m6A peaks were highly enriched near stop codons and in 3′-UTR regions, but they were also present in CDS and 5′-UTR regions (Figure 3A). We identified 51,618, 54,939, 49,284, and 50,147 peaks in the CK, P, S, and P + S samples, respectively. Of these, 31,909, 31,109, 26,938, and 29,510 peaks were confidently associated with 22,776, 22,890, 20,921, and 22,042 genes (log2|foldchange| ≥ 1 and p < 0.05) (Tables S2–S5, Figure 3B). Therefore, fewer m6A peaks were detected in the P, S, and P + S groups than in the CK. Compared with the Input group, these peaks showed a greater degree of enrichment at transcription start sites (TSSs) and transcription end sites (TESs) (Figure S1). Overall, the expression levels of m6A-modified genes were lower than those of genes without such modifications (Figure 3C). Genes with m6A modifications in the 5′-UTR and TSS regions had higher expression than genes with m6A modifications in the 3′-UTR, TES, and CDS regions; genes with m6A modifications in the 3′ UTR had the lowest expression (Figure 3D).

Figure 2.

Circos plot of genome-wide m6A modifications in soybean roots inoculated with SMV and/or Psg. From outside to inside, the eight rings represent: (1) genomic location, (2) density of differentially modified m6A peaks between P and CK plants, (3) density of differentially modified m6A peaks between S + P and CK plants, (4) density of differentially modified m6A peaks between S and CK plants, (5) genome-wide distribution of m6A peak density in CK plants, (6) genome-wide distribution of m6A peak density in P plants, (7) genome-wide distribution of m6A peak density in S plants, and (8) genome-wide distribution of m6A peak density in S + P plants.

Figure 3.

Global analysis of the m6A methylome in soybean leaves under control conditions (CK) and after inoculation with SMV, Psg, or both pathogens. (A) Density of m6A peaks in the 5′ UTR, CDS, 3′ UTR, start codon, and stop codon. (B) Numbers of m6A peaks identified in the CK, P, S, and P + S groups (log2 |fold change| ≥ 1 and p < 0.05). (C) Expression levels (log10 [FPKM + 1]) of genes with three m6A levels: no m6A (m6A sites = 0), low m6A (m6A sites < 3), and high m6A (m6A sites ≥ 3). (D) Expression levels (log10 [FPKM + 1]) of genes classified according to the location of the m6A peak: 3′ UTR, start codon, CDS, stop codon, and 5′ UTR. (E) Numbers of differentially methylated m6A peaks (DMPs) in three comparison groups: P vs. CK, S vs. CK, P + S vs. CK. (F) Venn diagram of genes associated with DMPs in the three comparison groups. (G,H) Numbers of differentially m6A-methylated genes associated with specific GO terms (G) and KEGG pathways (H) in three comparison groups: P vs. CK, S vs. CK, P + S vs. CK.

3.3. Differences in m6A Modification in Response to SMV and Psg Infection

To investigate differences in m6A modifications in response to SMV and Psg infection, we identified differentially methylated peaks (DMPs) between three pairs of treatments: P vs. CK (3751 DMPs), S vs. CK (3559 DMPs), S + P vs. CK (3751 DMPs). These DMPs corresponded to 3372, 3237, 3382 differentially m6A-modified genes, respectively (Figure 3E,F, Tables S6–S8), and 1739, 1683 and 1791 of these genes were unique to individual comparisons. 464 genes exhibited differential m6A modification across all three comparisons (Figure 3F).

We next identified Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways enriched in the differentially m6A-modified genes from each of the three comparisons. Many of the enriched terms and pathways were associated with RNA metabolism, including RNA binding, mRNA methylation, RNA degradation, RNA transport, and helicase activity (Figure 3G,H). Enriched GO terms that were common to multiple comparisons included ATP-dependent RNA helicase activity, helicase activity, RNA binding, and endonuclease activity. Enriched KEGG pathways common to multiple comparisons included base-excision repair and RNA degradation. Certain terms and pathways were enriched in only one comparison, such as chloroplast RNA processing and ascorbic acid metabolism (S + P vs. CK) or starvation stress response and phosphatidylinositol signaling (S vs. CK) (Figure S2). The number of genes enriched in disease resistance-related pathways was quantified for each treatment. In the GO enrichment analysis, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were primarily enriched in terms related to intracellular protein transport, protein kinase activity, protein phosphorylation, protein serine/threonine kinase activity, and RNA binding. KEGG pathway analysis revealed that DEGs were mainly enriched in ABC transporters, α-linolenic acid metabolism, ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway in plants, peroxisome, phosphatidylinositol signaling system, proteasome, and sphingolipid metabolism (Figure 3G,H).

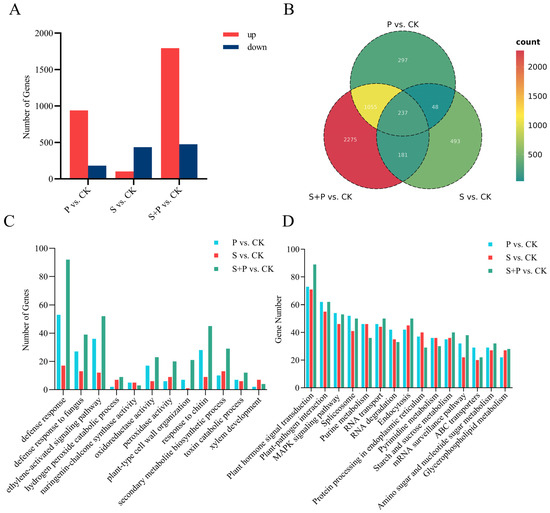

3.4. Differentially Expressed Genes in Soybean Leaves in Response to SMV and Psg Infection

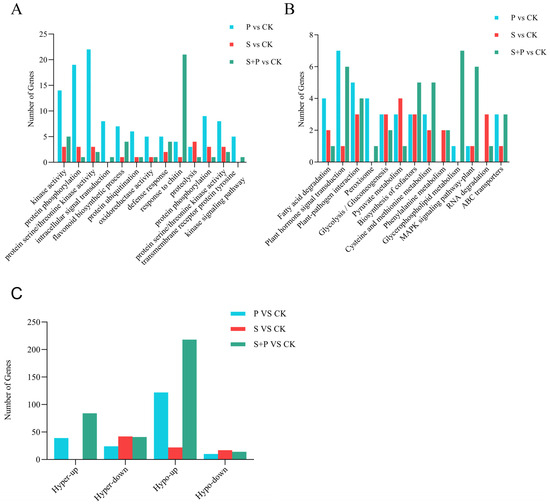

In addition to identifying genes whose m6A modification status changed, we also performed a basic transcriptomic analysis to identify genes whose expression changed in soybean leaves in response to SMV and Psg infection. We identified 1122 DEGs in the P vs. CK comparison (Table S9), with 939 upregulated and 183 downregulated (Figure 4A,B). Many of these DEGs were enriched in GO terms related to transcription and defense responses, and they were enriched in KEGG pathways such as plant–pathogen interaction, plant hormone signal transduction, RNA degradation, the MAPK signaling pathway-plant, and ABC transporters (Figure 4C,D). There were 103 upregulated and 436 downregulated DEGs in the S vs. CK comparison (Table S10, Figure 4A). Their GO annotations were similar to those from the P vs. CK comparison, and 14 of their top 20 enriched KEGG pathways were also the same. KEGG pathways enriched only in P vs. CK included glycerophospholipid metabolism, RNA transport, and mRNA surveillance, whereas those enriched only in S vs. CK included cyanoamino acid metabolism and phenylalanine metabolism (Figure 4C,D).

Figure 4.

Transcriptome-wide analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in soybean leaves during SMV and Psg infection. (A) Numbers of DEGs identified in the three comparisons: P vs. CK, S vs. CK, P + S vs. CK using the criteria log2|fold change| ≥ 1 and p < 0.05. (B) Venn diagram of DEGs identified in the three comparisons. (C,D) Numbers of DEGs associated with specific GO terms (C) and KEGG pathways (D) across three comparison groups: P vs. CK, S vs. CK, P + S vs. CK.

There were 1794 upregulated and 475 downregulated DEGs in the S + P vs. CK comparison (Table S11, Figure 4A), many of which were again annotated with GO terms related to transcription and defense responses. They shared 16 of the same top 20 enriched KEGG pathways with DEGs from the P vs. CK comparison, but they were also enriched in fructose and mannose metabolism, cyanoamino acid metabolism, and linoleic acid metabolism. Compared with the S vs. CK DEGs, the S + P vs. CK DEGs were uniquely enriched in glycerophospholipid metabolism, fatty acid degradation, RNA transport, other glycan degradation, and linolenic acid metabolism (Figure 4C,D).

3.5. Differentially Expressed, Differentially m6A-Modified Genes in Psg-Infected Soybean Leaves

We next identified genes that showed significant changes in both expression level and m6A methylation during Psg infection. A comparison of DEGs and DMPs from the P vs. CK comparison revealed 195 such genes: 39 were m6A hypermethylated and upregulated during infection (hyper-up), 24 were m6A hypermethylated and downregulated (hyper-down), 122 were m6A hypomethylated and upregulated (hypo-up), and 10 were m6A hypomethylated and downregulated (hypo-down) (Figure 5C). Thus, approximately 60% of the genes whose expression and methylation status changed during infection were hypo-up. Highly enriched GO annotations in the 195 genes included cutin biosynthetic process, flavonoid biosynthetic process, protein phosphorylation, and intracellular signal transduction (Figure 5A); enriched KEGG pathways included plant–pathogen interaction, plant hormone signal transduction, and ABC transporters (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Differentially m6A-methylated DEGs in soybean leaves during SMV and Psg infection. (A,B) Numbers of DMPs and DEGs associated with specific GO terms (A) and KEGG pathways (B) in three comparison groups: P vs. CK, S vs. CK, and P + S vs. CK. (C) Distribution of differentially m6A-methylated DEGs across four categories: hyper-up (hypermethylated and upregulated), hyper-down (hypermethylated and downregulated), hypo-up (hypomethylated and upregulated), and hypo-down (hypomethylated and downregulated).

We next examined individual genes that showed changes in both expression and m6A methylation upon Psg infection. Their annotations suggested that many had roles in several well-known biological processes related to defense against Psg. The salicylic acid (SA) and ethylene (ET)/jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathways are considered pillars of the plant immune response [45]. In our data, Glyma.09G032100 (hypo-up) was annotated as encoding the transcription factor MYB2, which contains a SANT/Myb domain. Previous studies have shown that QYR-APR-2A.2 encodes a SANT/Myb domain, and transcription factors with this domain play important roles in conferring resistance to stripe rust [46]. Likewise, the MYB transcription factor JMTF1 in rice promotes resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae by coordinating the crosstalk between jasmonic acid and auxin signaling [47]. Glyma.18G004200 (hypo-up) was annotated as a membrane attack complex/perforin (MACPF) protein. Overexpression of MACP2 in Arabidopsis can accelerate SA accumulation, activating the SA signaling pathway in response to pathogen invasion [48]. Another gene with potential roles in SA signaling was Glyma.10G018800 (hypo-up), annotated as the RING-type E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase BAH1, whose tomato homolog regulates the immune response to Psg by modulating SA accumulation [49].

Many of the 195 differentially m6A-methylated DEGs had serine/threonine protein kinase structures or related domains and were annotated as various types of receptor-like kinase (RLK). RLKs play central roles in pathogen recognition, signal transduction, and plant defense activation [50]. Glyma.17G103400 (hypo-up) and Glyma.05G024000 (hyper-up) were both annotated as leucine-rich repeat RLKs (LRR-RLKs). Members of this large protein family (200 in Arabidopsis) [51] act as receptors for plant hormones, endogenous peptides, and pathogen-derived molecules, regulating plant growth, development, and defense responses [52,53]. Glyma.06G086800 (hypo-up) was annotated as a potentially inactive LRR-RLK. Its homolog, At2g25790 in Arabidopsis thaliana, is also classified as an inactive LRR-RLK and has been identified as a hub gene associated with disease resistance [54]. Glyma.15G074600 (hypo-up) was annotated as an RLK with an L-type lectin domain. A similar protein, LLecRK-IX.2, promotes Psg resistance in Arabidopsis by acting as a positive regulator of PAMP-triggered immunity [55]. Glyma.10G253100 (hypo-up) was annotated as cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinase (CRK) 26 subtype X1. CRKs regulate pattern-triggered and effector-triggered immunity by modulating the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), influx of Ca2+ ions, activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, plant hormone signaling, and callose deposition [56]. Glyma.20G162300 (hypo-up) was annotated as a protein tyrosine kinase. Its homolog, AT5G24010 in Arabidopsis thaliana, belongs to the CrRLK1L family, members of which are involved in both biotic and abiotic stress responses [57].

Several ABC transporters were also identified among the differentially m6A-methylated DEGs in response to Psg. ABC transporters are known to play essential roles in abiotic stress responses, pathogen resistance, and plant-environment interactions [58]. Glyma.03G168000 (hypo-up), Glyma.06G191400 (hypo-up), Glyma.16G110100 (hypo-up), and Glyma.17G041200 (hypo-up) were all annotated as ABC transporters, with their respective Arabidopsis thaliana homologs being ABCG40, ABCA7, ABCG14, and ABCB11, respectively. In Arabidopsis, ABCG40 has been identified as a potential component of resistance to Phytophthora [59]. ABCG14 is responsible for transporting the phytohormone cytokinin (CK) from roots to shoots; deletion of ABCG14 inhibits SNC1-mediated defense responses, while exogenous application of tZ-type CK enhances basal resistance to p. syringae pv. [60]. ABCB transporters significantly contribute to directional auxin movement in tissue-level auxin transport assays [61]. Notably, in Arabidopsis, phosphorylation of ABCG36 by an LRR-RLK switches its substrate preference from the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid to the defense metabolite camalexin in response to pathogen infection [62]. Whether a similar regulatory mechanism involving LRR-RLKs and ABC transporters operates in soybean remains to be determined.

Additional differentially m6A-methylated DEGs during Psg infection were associated with fatty acid (FA) metabolism, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and gamma amino butyric acid (GABA). In particular, Glyma.07G161900 (hypo-up), Glyma.03G221350 (hypo-up), and Glyma.19G218300 (hypo-up) were all annotated as long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (LACs). In apple, MdLACS1 enhances pathogen resistance by promoting cuticular wax accumulation and altering endogenous immune responses [63]. Glyma.14G004500 (hypo-up) was annotated as a BC1 complex kinase; a related gene, wheat TaAbc1, mediates the hypersensitive response (HR) to specific pathotypes of wheat stripe rust through a mechanism that appears to involve ROS [64]. Glyma.12G207400 (hypo-up) was annotated as a glutaredoxin (GRX). These ubiquitous redox enzymes can reduce dehydroascorbic acid, peroxiredoxin, and methionine sulfoxide reductase, contributing to ROS removal and repair of oxidative damage [65]. In rice, OsGRX20 positively regulates responses to bacterial attack and abiotic stress [66]. Finally, Glyma.10G032700 (hypo-up) was annotated as a GABA transporter, and increased GABA levels at infection sites have been linked to reduced symptoms and reduced bacterial growth during P. syringae infection of Arabidopsis and tomato [67].

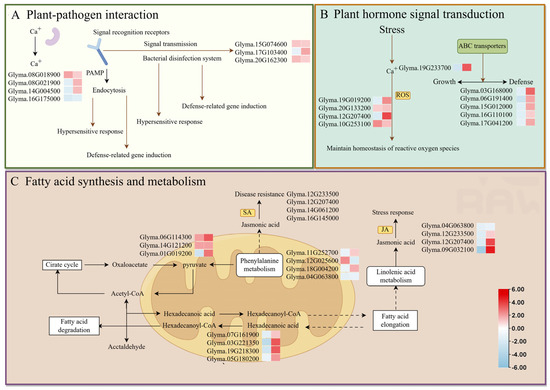

We examined the expression of genes involved in plant-pathogen interactions, hormone signal transduction, and long-chain fatty acid synthesis. DEGs with distinct m6A methylation levels in these pathways are speculated to play important roles in the response of soybean to Pseudomonas infection (Figure 6). Most DEGs exhibited hypomethylation coupled with high expression, whereas a smaller subset showed hypermethylation with low expression, hypermethylation with high expression, or hypomethylation with low expression. These results suggest a potential negative correlation between gene methylation and expression, indicating that gene hypomethylation during Psg infection may play a key role in promoting the upregulation of defense-related genes.

Figure 6.

Proposed model showing how significant changes in the m6A-methylation status and expression of soybean genes during Psg infection could influence (A) plant–pathogen interactions, (B) hormone signal transduction, and (C) fatty acid synthesis and metabolism. In the small heatmaps, the left-hand box shows the change in m6A-methylation upon infection (blue, reduced; red, increased), and the right-hand box shows the change in gene expression.

3.6. Differentially Expressed, Differentially m6A-Modified Genes in SMV-Infected Soybean Leaves

Eighty-four genes showed significant changes in both expression level and m6A methylation during SMV infection: 0 hyper-up, 45 hyper-down, 22 hypo-up, and 17 hypo-down (Figure 5C). In contrast to Psg infection, which was associated with more hypo-up DEGs, SMV infection was associated with more hyper-down DEGs.

Among the 84 m6A-modified DEGs identified, some GO annotations overlapped with those from the P vs. CK comparison, such as defense response and protein phosphorylation. However, many others were specific to the S vs. CK comparison, including rRNA methylation and histone glutamine methylation, or to the P vs. CK comparison, including cutin biosynthesis and alanine-glyoxylate transaminase activity (Figure S4A–C). In the GO enrichment analysis of disease resistance-related terms, genes from the S vs. CK comparison were predominantly enriched in categories such as kinase activity, protein phosphorylation, proteolysis, and protein serine/threonine kinase activity (Figure 5A). Common KEGG pathways enriched in m6A-modified DEGs from both comparisons included plant–pathogen interaction, flavonoid biosynthesis, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and fatty acid degradation. Pathways specifically enriched in the S vs. CK comparison included limonene and pinene degradation and glucosinolate biosynthesis, whereas those specifically enriched in the P vs. CK comparison included amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and cyanoamino acid metabolism (Figure S4D–F). In the KEGG annotation analysis related to disease resistance, genes from the S vs. CK comparison were mainly enriched in plant–pathogen interaction, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and RNA degradation pathways (Figure 5B).

Plant immunity relies on the perception of extracellular signals by transmembrane receptors. Numerous receptor-like proteins (RLPs) and RLKs have been identified as PRRs with key functions in plant development and innate immunity [68], and plants may use pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) to combat viral infections as well as other microbial infections [69]. A number of receptor-like genes were differentially m6A-methylated and differentially expressed during SMV infection. Glyma.13G253300 (hyper-down) and Glyma.14G111900 (hyper-down) were annotated as RLKs; Glyma.11G204766 (hyper-down) and Glyma.11G207500 (hypo-down) were annotated as cysteine-rich RLKs; and Glyma.13G353052 (hyper-down) and Glyma.16G112600 (hyper-down) were annotated as intracellular Ras-group-related LRR proteins. In rice, the LRR RLP gene OsRLP1 was significantly upregulated upon infection with Rice black-streaked dwarf virus (RBSDV), and further experiments demonstrated that OsRLP1 promotes rice RBSDV resistance by positively regulating the activation of MAPKs and the expression of PTI-related genes [70].

Fine-tuning of signal transduction and gene expression is required to regulate plant defense mechanisms [71], and transcription factors play an important part in this process through their roles as transcriptional activators and inhibitors [72]. For example, TFs from the MYB and AP2/ERF families have been shown to regulate the transcription of virus-responsive genes, including R genes, the tobacco N gene, and genes related to RNA silencing and transcriptional repression [73,74,75,76,77,78]. Among the differentially m6A-methylated DEGs identified during SMV infection, Glyma.06G163700 (hyper-down) encodes an AP2/ERF transcription factor, with its Arabidopsis homolog annotated as ERF114. Both Glyma.16G047600 (hyper-down) and Glyma.17G210500 (hypo-down) have Arabidopsis homologs annotated as AP2. ERF114 is known to enhance disease resistance by positively regulating lignin and SA accumulation [79]. In Arabidopsis thaliana infected with Turnip Crinkle Virus (TCV), the flower structure-related gene APETALA2 (AP2) is downregulated, and its expression has been shown to affect plant resistance [80]. Glyma.20G224000 (hypo-up) and Glyma.13G195800 (hypo-up) were annotated as trihelix (or GT) transcription factors, and a role for GT-3b in the response of Arabidopsis to Psg has long been verified [81]. Finally, Glyma.07G109600 (hypo-up) was annotated as a squamosa promoter-binding-like TF. A rice protein from the same family, SPL9, negatively regulates antiviral defenses through transcriptional activation of the microRNA miR528 [82].

Perturbation of antioxidant metabolism during late-stage viral infection can lead to senescence-like symptoms in susceptible plant tissues [83], and a number of differentially m6A-methylated DEGs during SMV infection had potential associations with ROS accumulation. Glyma.09G277800 (hyper-down) was annotated as a peroxidase precursor, and Glyma.04G123800 (hyper-down) was annotated as a mitochondrial-associated alternative oxidase (AOX). AOX can reduce levels of ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) by preventing over-reduction in the mitochondrial electron transport chain [84], and its induction during TMV infection has been shown to initiate antiviral defense responses in tomato [85]. Other differentially m6A-methylated DEGs in SMV-infected plants included Glyma.04G088200 (hypo-up) and Glyma.06G090200 (hypo-up), encoding amino acid permeases (AAPs), and Glyma.09G109200 (hypo-up), encoding a 90 kDa heat-shock protein ATPase. AAPs promote pathogen susceptibility in Arabidopsis, tomato, and cucumber [86], and heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90) is crucial for pathogen defense mediated by R proteins [87].

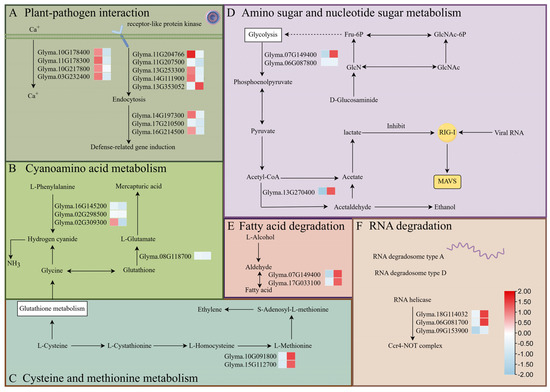

We examined the expression of genes involved in plant-pathogen interaction, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, cyanoamino acid metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, RNA degradation, and fatty acid degradation. DEGs with distinct m6A methylation levels in these pathways are speculated to play important roles in the response of soybean to SMV infection. Most differentially expressed genes exhibited hypermethylation coupled with low expression, while a few showed hypermethylation or hypomethylation with low expression (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed model showing how significant changes in the m6A-methylation status and expression of soybean genes during SMV infection could influence (A) plant-pathogen interaction, (B) cyanoamino acid metabolism, (C) cysteine and methionine metabolism, (D) amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, (E) the fatty acid degradation pathway, and (F) the RNA degradation pathway. In the small heatmaps, the left-hand box shows the change in m6A-methylation upon infection (blue, reduced; red, increased), and the right-hand box shows the change in gene expression.

3.7. Differentially Expressed, Differentially m6A-Modified Genes in Soybean Leaves During Simultaneous Psg and SMV Infection

There were 357 genes with significant changes in both expression and m6A methylation during co-infection with Psg and SMV: 84 hyper-up, 41 hyper-down, 218 hypo-up, and 14 hypo-down (Figure 5C). Approximately 60% of these genes were hypo-up, a pattern more similar to infection with Psg alone than with SMV alone. Some GO annotations were shared among all three comparisons (P vs. CK, S vs. CK, and P + S vs. CK), including protein phosphorylation and protein serine/threonine kinase activity (Figure 5A). However, other terms were specific to the P + S vs. CK comparison, such as response to chitin and DNA unwinding involved in DNA replication. KEGG pathways unique to the P + S vs. CK comparison included glycerophospholipid metabolism and the MAPK signaling pathway (Figure 5B).

A number of NBS-LRR and PRR proteins were among the differentially m6A-modified DEGs during co-infection with Psg and SMV. Glyma.04G165400 (hypo-up), Glyma.04G012800 (hyper-up), and Glyma.08G198900 (hyper-up) were annotated as putative LRR receptor-like serine/threonine protein kinases, and Glyma.08G229100 (hypo-up) was annotated as a potentially inactivated LRR-RLK. Glyma.06G112500 (hypo-up) was annotated as a GPI-anchored protein with a LysM domain. LYP4 and LYP6 are promiscuous PRRs that sense bacterial peptidoglycans and chitin in rice innate immunity [88]. Glyma.09G210600 (hypo-up) was annotated as the disease-resistance protein RPM1, an NBS-LRR protein. The similar rice protein encoded by RPM1-like resistance gene 1 (OsRLR1) mediates responses to fungal and bacterial pathogens through direct interaction with OsWRKY19 in the nucleus [89].

Additional differentially m6A-modified DEGs also had potential roles in defense, given their similarity to defense-related genes characterized previously in other species. The Arabidopsis homolog of Glyma.08G018300 (hypo-up) is WRKY29; Glyma.05G127600 (hypo-up) also corresponds to a WRKY transcription factor, and Glyma.17G011400 (hypo-up) is homologous to WRKY6. In Arabidopsis, WRKY29 is induced by the MAPK pathway and confers resistance to bacterial and fungal pathogens, with transient expression reducing leaf disease symptoms [90]. In rice, OsWRKY6 activates defense responses by directly regulating OsPR10a and OsICS1, the latter promoting salicylic acid (SA) biosynthesis and SA-mediated defense signaling [91]. Glyma.07G051500 (hypo-down) was annotated as MYC2, and phosphorylation-coupled proteolysis of MYC2 is important for Arabidopsis immunity mediated by jasmonate signaling [92]. Glyma.03G088800 (hypo-up) was annotated as the serine/threonine protein kinase OXI1, which functions in an H2O2-regulated pathway by activating MPK3 during soybean defense against SMV [93]. Glyma.02G042500 (hypo-up) was annotated as a class I chitinase precursor, and chitinase expression is often induced by pathogens [94,95]. Glyma.04G187600 (hypo-up) and Glyma.01G007800 (hypo-up) are homologous to Arabidopsis DMT1 and CMT3, respectively. The repertoire of PRR and NLR immune receptors is critical for plant resistance to pathogens. DMT1, CMT3, MOM1, SUVH4/5/6, and DDM1, along with REF6, help establish chromatin states that repress constitutive PRR/NLR gene activation while facilitating their priming via epigenetic modifications at their promoters [96]. Glyma.13G001200 (hypo-up) was annotated as methionine γ-lyase. Viral proteins have been shown to interact with methionine cycle enzymes to promote infection: virus-induced changes in the activities of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase and S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase can weaken RNA silencing and affect antiviral defenses related to the ethylene and polyamine biosynthetic pathways [97]. Glyma.08G281700 (hypo-up) encodes a BTB/POZ-domain-containing protein. In soybean, GmBTB/POZ and the homolog NbBTB in Nicotiana benthamiana have been shown to negatively regulate basal defense and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) against Phytophthora parasitica [98]. Glyma.08G299300 (hypo-up) was annotated as an HVA22-like protein. ER-associated HVA22 proteins regulate immune activation, and the rice HVA22 protein OsHLP1 is a key component of ER homeostasis that helps to balance growth and disease resistance [99]. Glyma.13G233300 (hypo-up) was annotated as a glutamate receptor-like protein, and signaling mediated by GLRs negatively regulates regeneration but positively regulates defense responses via SA in multiple species [100]. Glyma.02G244700 (hypo-up) and Glyma.02G269000 (hypo-up) were both annotated as endo-1,3-β-glucanases. Many studies have shown that fungal, bacterial, and viral infections stimulate the synthesis of endo-1,3-β-glucanases in plants; examples include barley infected with powdery mildew, maize infected with Aspergillus flavus, and wheat infected with Fusarium graminearum [101,102,103,104]. All of these putative defense-related soybean genes are potential targets for experimental validation and for use in the breeding or engineering of disease-resistant soybean.

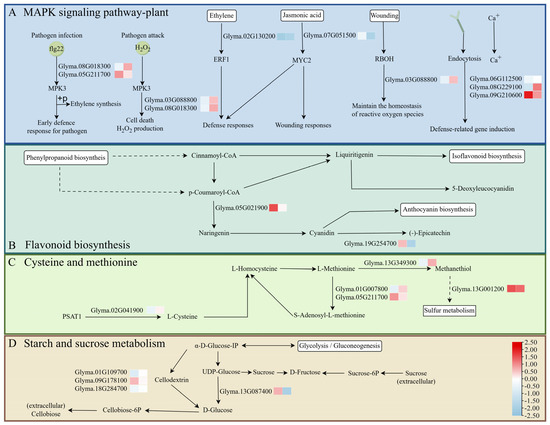

We examined the expression of genes involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, flavonoid biosynthesis, cysteine and methionine metabolism, as well as starch and sucrose metabolism. DEGs with distinct m6A methylation levels in these pathways are speculated to play key roles in soybean responses to SMV (Soybean Mosaic Virus) and Psg (Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea) infections. Most of the DEGs exhibited hypomethylation coupled with high expression (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed model showing how significant changes in the m6A-methylation status and expression of soybean genes during co-infection with Psg and SMV could influence (A) the MAPK signaling pathway, (B) the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway, (C) the cysteine and methionine pathway, and (D) starch and sucrose metabolism. In the small heatmaps, the left-hand box shows the change in m6A-methylation upon infection (blue, reduced; red, increased), and the right-hand box shows the change in gene expression.

4. Discussion

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent post-transcriptional RNA modification in eukaryotes and is present in various RNA types, including mRNA, tRNA, miRNA, and long non-coding RNA. It plays a vital role in regulating plant responses to both biotic and abiotic stresses [105] by modulating transcript stability and abundance. Disruption of the m6A methyltransferase complex or overexpression of major demethylases significantly alters basal immune responses, likely through m6A-mediated transcriptome reprogramming [106]. Recent studies have further highlighted m6A’s role in plant–virus interactions and viral pathogenesis: host methyltransferases and demethylases can stabilize or degrade viral RNAs, while viral infection can in turn affect host m6A machinery and influence viral life cycle and pathogenesis [107].

Here, we performed transcriptome sequencing and m6A methylation profiling of soybean plants infected with Psg, SMV, or both, to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying soybean defense against these pathogens, with an emphasis on differential m6A methylation. Our results reveal the transcriptional dynamics of m6A-mediated immune responses and provide strong evidence that m6A plays a critical role in fine-tuning plant immunity during pathogen challenge.

In the innate immune response, Arabidopsis detects bacterial and fungal proteins by recognizing conserved pathogen/microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs/MAMPs), thereby initiating PAMP/MAMP-triggered immunity (PTI/MTI) [108]. A well-characterized Pseudomonas PAMP is flagellin (flg22), which activates downstream signaling cascades, including ROS production, MAPK activation, and the expression of defense-related genes characteristic of PTI [109]. PTI also modulates defense-related hormone pathways, such as SA and JA, to coordinate immune output and balance growth-defense trade-offs [110,111]. Studies on the role of m6A methylation in crop antibacterial resistance show that m6A modification regulates the expression of crop immune-related genes. For example, the transcriptome-regulating role of m6A in Arabidopsis plant immunity indicates that plant defense is coordinated through the complex regulation of post-transcriptional m6A modification of a specific set of mRNAs in the plant transcriptome [112]. These complex immune responses require precise regulation at multiple levels of gene expression [113].

Virus infection can change the host’s m6A mechanism, thereby affecting the virus life cycle [114]. Studies have found that crops regulate the expression of antiviral genes through m6A modification. The m6A methylation level increases in the response of rice to virus infection. Some genes related to antiviral pathways, such as those related to RNA silencing, resistance, and basic antiviral plant hormone metabolism, are also m6A-methylated. The m6A methylation level is closely related to its relative expression level [115]. As one of the core post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, m6A modification can target and modify the mRNAs of crop immunity-related genes, thereby regulating the bacterial resistance pathways and acting as a key molecular switch for plants to coordinate the activation of defense responses and balance growth and disease resistance.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis revealed that m6A peaks in soybean transcripts are predominantly enriched near stop codons and within 3′-UTRs (Figure 3A), a distribution pattern consistent with previous observations in Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, maize, wheat, and tomato [116,117]. Transcriptome-wide m6A methylation was generally negatively correlated with transcript abundance (Figure 3C), although genes with m6A modifications in the 5′ UTR or TSS showed higher expression than those with m6A modifications in the 3′ UTR, TES, or CDS (Figure 3D).

The total number of high-confidence m6A peaks was somewhat lower in infected soybean plants than in control plants (Figure 3B), but there were a large number of differentially methylated transcripts in infected plants: 1122 in Psg, 539 in SMV, and 2269 in co-infected plants relative to controls. In addition, 195 (Psg), 84 (SMV), and 354 (Psg + SMV) transcripts were both differentially methylated and differentially expressed in infected plants compared with controls. Interestingly, the predominant category of these differentially methylated DEGs differed between the treatments: in the Psg treatment, the majority (63.5%) were hypomethylated and upregulated, whereas in the SMV treatment, the majority (54%) were hypermethylated and downregulated. Both of these patterns are consistent with the general observation that m6A methylation is associated with lower gene expression.

Differentially methylated DEGs in response to Psg infection were primarily enriched in plant–pathogen interaction, hormone (JA and SA) signal transduction, long-chain fatty acid synthesis, and immune receptor recognition pathways, accompanied by increased ROS production (Figure 6). Psg triggered changes in immune receptor recognition, hormone (SA and JA) signaling, and ROS production, consistent with patterns seen in wheat [44]. Plant hormones, particularly JA and SA, play key roles in responses.

In contrast, SMV infection mainly affected DEGs involved in plant–pathogen interaction, amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, RNA degradation, and fatty acid degradation (Figure 7). SMV also altered immune recognition and stimulated the synthesis of antibacterial compounds, as well as DEGs associated with RNA degradation and plant–pathogen interaction.

Co-infection with Psg and SMV triggered even more extensive changes in both gene expression and m6A methylation, with 195, 84, and 357 genes exhibiting concurrent changes under Psg, SMV, and co-infection, respectively. Enriched pathways included MAPK signaling, flavonoid biosynthesis, cysteine and methionine metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism and RNA degradation (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The MAPK pathway is the core of antiviral defense, and secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, phytoalexins, and phytoantigens play important roles under biotic stress. In summary, our results demonstrate that m6A methylation dynamically regulates distinct defense pathways in response to Psg, SMV, and co-infection in soybean leaves, contributing to enhanced immune responses against both bacterial and viral pathogens.

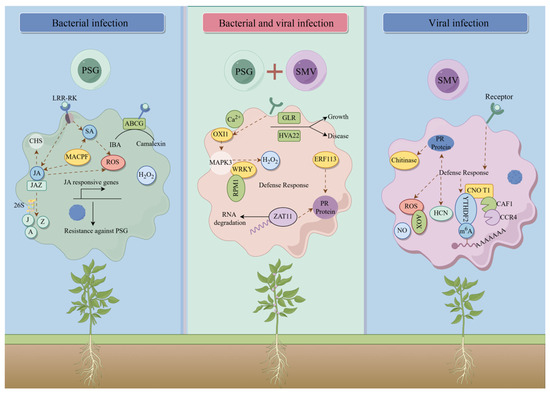

Figure 9.

A model of the process influenced by transcriptome-wide m6A methylation under SMV and Psg stresses was proposed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020208/s1.

Author Contributions

G.P.: Writing—original draft preparation; J.Z.: data curation, visualization, investigation; H.D.: data curation, visualization; J.W.: data curation, visualization; Q.W.: data curation, visualization; D.X.: supervision and reviewing; Q.C.: supervision and reviewing; Z.Q.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (ZL2024C007), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023ZD0403201-03, 2021YFD1201103), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472108, 32201755, 32272072), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023MD744203), the Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Science Foundation (LBH-Z23011), and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-04-PS15).

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data has been deposited in the BIG Submission (BIG Sub) database, with the GSA accession number subCRA047873. Other related data are available in the Supplementary Tables.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Soybean Genetic Improvement Team for their support and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Byamukama, E.; Robertson, A.E.; Nutter, F.W., Jr. Bean pod mottle virus Time of Infection Influences Soybean Yield, Yield Components, and Quality. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gao, L.; Xie, L.; Xiao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Pu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, H.; et al. CRISPR/CasRx-mediated resistance to soybean mosaic virus in soybean. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.J.; Nyvall, R.F. Leaf infection and yield losses caused by brown spot and bacterial blight diseases of soybean. Phytopathology 1980, 70, 900–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, T.; Xie, H.; Hu, H.; Shi, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, J.; Xu, G.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; et al. An m6A methyltransferase confers host resistance by degrading viral proteins through ubiquitination. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.S.; Li, M.M.; Wang, X.J.; Yang, Y.G. N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: An old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2013, 11, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzbieta, K.; Ryszard, K. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 4472–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Nie, X.; Yan, Z.; Song, W. N6-methyladenosine regulatory machinery in plants: Composition, function and evolution. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1194–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.E.; Zhao, X.U.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.D.; Saletore, Y.; Zumbo, P.; Elemento, O.; Mason, C.E.; Jaffrey, S.R. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 2012, 149, 1635–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6ARNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hsu, P.J.; Chen, Y.S.; Yang, Y.G. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: Writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokar, J.A.; Shambaugh, M.E.; Polayes, D.; Matera, A.G.; Rottman, F.M. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA 1997, 3, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S.; Li, H.; Bodi, Z.; Button, J.; Vespa, L.; Herzog, M.; Fray, R.G. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Růžička, K.; Zhang, M.; Campilho, A.; Bodi, Z.; Kashif, M.; Saleh, M.; Eeckhout, D.; El-Showk, S.; Li, H.; Zhong, S.; et al. Identification of factors required for m6 A mRNA methylation in Arabidopsis reveals a role for the conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Liang, Z.; Gu, X.; Chen, Y.; Norman Teo, Z.W.; Hou, X.L.; Cai, W.L.; Dedon, P.C.; Liu, L.; Yu, H. N(6)-Methyladenosine RNA Modification Regulates Shoot Stem Cell Fate in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.A.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.M.; Li, C.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.L.; Song, S.H.; et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, M.; Aparicio, F.; López-Gresa, M.P.; Pallás, V. Arabidopsis m6A demethylase activity modulates viral infection of a plant virus and the m6A abundance in its genomic RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10755–10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, H.C.; Wei, L.H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Lu, Z.; Chen, P.R.; He, C.; Jia, G. ALKBH10B Is an RNA N6-Methyladenosine Demethylase Affecting Arabidopsis Floral Transition. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 2995–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, G.; Tang, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Tian, S.; Qin, G. Redox modification of m6A demethylase SlALKBH2 in tomato regulates fruit ripening. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.N.; Han, D.L.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.F.; et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.Y.; et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arribas-Hernández, L.; Bressendorff, S.; Hansen, M.H.; Poulsen, C.; Erdmann, S.; Brodersen, P. An m6A-YTH Module Controls Developmental Timing and Morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, T.; Kang, H. Crosstalk between RNA m6A modification and epigenetic factors in plant gene regulation. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, M.; Zhao, B.S.; Harder, O.; Li, A.Z.; Liang, X.Y.; Gao, T.Z.; Xu, Y.S.; Zhou, J.Y.; et al. N6-methyladenosine modification enables viral RNA to escape recognition by RNA sensor RIG-I. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Zhuang, X.; Dong, Z.; Xu, K.; Chen, X.J.; Liu, F.; He, Z. The dynamics of N6-methyladenine RNA modification in interactions between rice and plant viruses. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondo, S.J.; Dannebaum, R.O.; Kuo, R.C.; Louie, K.B.; Bewick, A.J.; LaButti, K.; Haridas, S.; Kuo, A.; Salamov, A.; Ahrendt, S.R.; et al. Widespread adenine N6-methylation of active genes in fungi. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, J.; Cannon, S.B.; Schlueter, J.; Ma, J.X.; Mitros, T.; Nelson, W.; Hyten, D.L.; Song, Q.; Thelen, J.J.; Cheng, J.L.; et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 2010, 463, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimorad, M.R.; Domier, L.L.; Tolin, S.A.; Whitham, S.A.; Saghai Maroof, M.A. Soybean Mosaic Virus: A successful potyvirus with a wide distribution but restricted natural host range. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.L.; Rupe, J.C.; Chen, P.; Mozzoni, L.A. Inheritance and Genetic Mapping of Resistance to Pythium Damping-Off Caused by Pythium aphanidermatum in ‘Archer’ Soybean. Crop Sci. 2008, 48, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xin, X.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Zou, J.N.; Cheng, X.F.; Zhang, N.; Hu, Y.X.; et al. GsRSS3L, a Candidate Gene Underlying Soybean Resistance to Seedcoat Mottling Derived from Wild Soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Kørner, C.J.; Du, X.R.; Vollmer, M.E.; Pajerowska-Mukhtar, K.M. Bacterial Leaf Infiltration Assay for Fine Characterization of Plant Defense Responses using the Arabidopsis thaliana-Pseudomonas syringae Pathosystem. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 104, 53364. [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Amariglio, N.; Rechavi, G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N(6)-methyladenosine by m6A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Dong, H.; Feng, X.; Li, T.; Zhou, C.; Yu, J.; Xin, D.; et al. Changes in the m6A RNA methylome accompany the promotion of soybean root growth by rhizobia under cadmium stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliyodan, B.; Cannon, S.B.; Bayer, P.E.; Shu, S.Q.; Brown, A.V.; Ren, L.H.; Jenkins, J.; Chung, C.Y.L.; Chan, T.F.; Daum, C.G.; et al. Construction and comparison of three reference-quality genome assemblies for soybean. Plant J. 2019, 100, 1066–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Rao, M.K.; Huang, Y. A protocol for RNA methylation differential analysis with MeRIP-Seq data and exomePeak R/Bioconductor package. Methods 2014, 69, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, w202–w208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, S.; Benner, C.; Spann, N.; Bertolino, E.; Lin, Y.C.; Laslo, P.; Cheng, J.X.; Murre, C.; Singh, H.; Glass, C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; He, Q.Y. ChIPseeker: An R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2382–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado-Marchena, L.; Martínez-Pérez, M.; Úbeda, J.R.; Bertolino, E.; Lin, Y.C.; Laslo, P.; Cheng, J.X.; Murre, C.; Singh, H.; ∙Glass, C.K. Impact of the Potential m6A Modification Sites at the 3′UTR of Alfalfa Mosaic Virus RNA3 in the Viral Infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.F.; Balcerzak, M.; Rocheleau, H.; Leung, W.; Wei, Y.M.; Zheng, Y.L.; Ouellet, T. Jasmonic acid and abscisic acid play important roles in host–pathogen interaction between Fusarium graminearum and wheat during the early stages of fusarium head blight. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 93, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Han, X.; Feng, D.; Yuan, D.; Huang, L.J. Signaling Crosstalk between Salicylic Acid and Ethylene/Jasmonate in Plant Defense: Do We Understand What They Are Whispering? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, I.; Saripalli, G.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Batra, R.; Sharma, P.K.; Balyan, H.S.; Gupta, P.K. Meta-QTLs and candidate genes for stripe rust resistance in wheat. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uji, Y.; Suzuki, G.; Fujii, Y.; Kashihara, K.; Yamada, S.; Gomi, K. Jasmonic acid (JA)-mediating MYB transcription factor1, JMTF1, coordinates the balance between JA and auxin signalling in the rice defence response. Physiol. Plant 2024, 176, e14257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Dai, Y.S.; Wang, Y.X.; Su, Z.Z.; Yu, L.J.; Zhang, Z.F.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.F. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis MACPF Protein AtMACP2 Promotes Pathogen Resistance by Activating SA Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaeno, T.; Iba, K. BAH1/NLA, a RING-type ubiquitin E3 ligase, regulates the accumulation of salicylic acid and immune responses to Pseudomonas syringae DC3000. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A.J.; Wood, A.J.; Lightfoot, D.A. Plant receptor-like serine threonine kinases: Roles in signaling and plant defense. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2008, 21, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, S.H.; Bleecker, A.B. Plant receptor-like kinase gene family: Diversity, function, and signaling. Sci. STKE 2001, 2001, re22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, D.; Zipfel, C. Regulation of pattern recognition receptor signalling in plants. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Wang, G.; Zhou, J.M. Receptor Kinases in Plant-Pathogen Interactions: More Than Pattern Recognition. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Dong, Y.; Feng, S.; Zhou, R.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.Q. Transcriptome and proteome analysis of walnut (Juglans regia L.) fruit in response to infection by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Wu, W.; Liang, Y.; Xu, N.; Wang, Z.; Zou, H.; Liu, J. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the lectin receptor-like kinase LORE regulates plant immunity. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Tian, H.; Chen, D.; Zhang, H.; Sun, M.; Chen, D.; Qin, Z.; Ding, Z.; Dai, S. Cysteine-rich receptor-like protein kinases: Emerging regulators of plant stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, H.; Müller, L.M.; Boisson-Dernier, A.; Grossniklaus, U. CrRLK1L receptor-like kinases: Not just another brick in the wall. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Park, J.; Choi, H.; Burla, B.; Kretzschmar, T.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E. Plant ABC Transporters. Arab. Book 2011, 9, e0153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cordewener, J.H.; America, A.H.; Shan, W.X.; Bouwmeester, K.; Govers, F. Arabidopsis lectin receptor kinases LecRK-IX. 1 and LecRK-IX. 2 are functional analogs in regulating Phytophthora resistance and plant cell death. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Sun, Q.; Yang, L.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, Y.P.; Hua, J. A role of cytokinin transporter in Arabidopsis immunity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Cho, H.T. The function of ABCB transporters in auxin transport. Plant Signal Behav. 2013, 8, e22990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryal, B.; Xia, J.; Hu, Z.; Stumpe, M.; Tsering, T.; Liu, J.; Huynh, J.; Fukao, Y.; Glöckner, N.; Huang, H.Y. An LRR receptor kinase controls ABC transporter substrate preferences during plant growth-defense decisions. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 2008–2023.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Gao, H.M.; Wang, H.B.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.Y. An apple long-chain acyl-CoA synthase, MdLACS1, enhances biotic and abiotic stress resistance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 189, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Yin, S.N.; Zhang, H.C.; Huang, L.; Kang, Z.S. TaAbc1, a member of Abc1-like family involved in hypersensitive response against the stripe rust fungal pathogen in wheat. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, S.; Yamashita, Y.; Fujiki, M.; Todaka, R.; Nishikawa, Y.; Hosoki, A.; Yabe, C.; Nakamura, J.; Kawamura, K.; Suwastika, I.N.; et al. Expression of a rice glutaredoxin in aleurone layers of developing and mature seeds: Subcellular localization and possible functions in antioxidant defense. Planta 2015, 242, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Sun, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. A Rice CPYC-Type Glutaredoxin OsGRX20 in Protection against Bacterial Blight, Methyl Viologen and Salt Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Mirabella, R.; Bronstein, P.A.; Preston, G.M.; Haring, M.A.; Lim, C.K.; Collmer, A.; Schuurink, R.C. Mutations in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase genes in plants or Pseudomonas syringae reduce bacterial virulence. Plant J. 2010, 64, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Feng, B.; He, P.; Shan, L. From Chaos to Harmony: Responses and Signaling upon Microbial Pattern Recognition. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017, 55, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehl, A.; Wyrsch, I.; Boller, T.; Heinlein, K. Double-stranded RNAs induce a pattern-triggered immune signaling pathway in plants. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, C.; Li, L.; Tan, X.; Wei, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, F.; Chen, J.; Sun, Z. A rice LRR receptor-like protein associates with its adaptor kinase OsSOBIR1 to mediate plant immunity against viral infection. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2319–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaill, P.; Rivas, S. Transcriptional control of plant defence responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 20, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, E.; Choi, D.C. Functional studies of transcription factors involved in plant defenses in the genomics era. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2015, 14, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Klessig, D.F. Isolation and characterization of a tobacco mosaic virus-inducible myb oncogene homolog from tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 14972–14977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, B.L.; Sun, S.; Xing, G.M.; Wang, F.; Li, M.Y.; Tian, Y.S.; Xiong, A.S. AP2/ERF Transcription Factors Involved in Response to Tomato Yellow Leaf Curly Virus in Tomato. Plant Genome 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.C.; Yeam, I.; Jahn, M.M. Genetics of plant virus resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2005, 43, 581–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathe, R.; Anandalakshmi, R.; Liu, Y.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P. The tobacco mosaic virus resistance gene, N. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Nandety, R.S.; Zhang, Y.; Reid, M.S.; Niu, L.; Jiang, C.Z. A petunia ethylene-responsive element binding factor, PhERF2, plays an important role in antiviral RNA silencing. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 3353–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzatto, C.; Machado, J.P.; Lopes, K.V.; Nascimento, K.J.T.; Pereira, W.A.; Brustolini, O.J.B.; Reis, P.A.B.; Calil, I.P.; Deguchi, M.; Sachetto-Martins, J.; et al. NIK1-mediated translation suppression functions as a plant antiviral immunity mechanism. Nature 2015, 520, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Jia, F.; Zeng, H.; Li, G.; Yang, X. Ethylene-responsive factor ERF114 mediates fungal pathogen effector PevD1-induced disease resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Liu, P.; Irwanto, N.; Loh, D.R.; Wong, S.M. Upregulation of LINC-AP2 is negatively correlated with AP2 gene expression with Turnip crinkle virus infection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 2257–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Kim, M.L.; Kang, Y.H.; Jeon, J.M.; Yoo, J.H.; Kim, M.C.; Park, C.Y.; Jeong, J.C.; Moon, B.C.; Lee, J.K.; et al. Pathogen- and NaCl-induced expression of the SCaM-4 promoter is mediated in part by a GT-1 box that interacts with a GT-1-like transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Yang, Z.; Yang, R.; Huang, Y.; Guo, G.; Kong, X.; Lan, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; et al. Transcriptional regulation of miR528 by OsSPL9 orchestrates antiviral response in rice. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, J.A. Oxidative stress and antioxidative responses in plant-virus interactions. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 94, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.J.; Igamberdiev, A.U.; Mur, L.A. NO and ROS homeostasis in mitochondria: A central role for alternative oxidase. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.J.; Shi, K.; Gu, M.; Zhou, Y.H.; Dong, D.K.; Liang, W.S.; Song, F.M.; Yu, J.Q. Systemic induction and role of mitochondrial alternative oxidase and nitric oxide in a compatible tomato-Tobacco mosaic virus interaction. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J.A.; Hermans, F.W.K.; Beenders, F.; Abedinpour, H.; Vriezen, W.H.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bai, Y.; Schouten, H.J. The amino acid permease (AAP) genes CsAAP2A and SlAAP5A/B are required for oomycete susceptibility in cucumber and tomato. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2021, 22, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangster, T.A.; Queitsch, C. The HSP90 chaperone complex, an emerging force in plant development and phenotypic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2005, 8, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, J.F.; Ao, Y.; Qu, J.; Li, Z.; Su, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, D.; Qi, K.; et al. Lysin motif-containing proteins LYP4 and LYP6 play dual roles in peptidoglycan and chitin perception in rice innate immunity. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3406–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Zhang, C.; Xing, Y.; Lu, X.; Cai, L.; Yun, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, M.; et al. The CC-NB-LRR OsRLR1 mediates rice disease resistance through interaction with OsWRKY19. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, T.; Tena, G.; Plotnikova, J.; Willmann, M.R.; Chiu, W.L.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Boller, T.; Ausubel, F.M.; Sheen, J. MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 2002, 415, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Hwang, S.H.; Fang, I.R.; Kwon, S.I.; Park, S.R.; Ahn, I.; Kim, J.B.; Hwang, D.J. Molecular characterization of Oryza sativa WRKY6, which binds to W-box-like element 1 of the Oryza sativa pathogenesis-related (PR) 10a promoter and confers reduced susceptibility to pathogens. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Q.; Yan, L.; Tan, D.; Chen, R.; Sun, J.Q.; Gao, L.Y.; Dong, M.Q.; Wang, Y.C.; Li, C.Y. Phosphorylation-coupled proteolysis of the transcription factor MYC2 is important for jasmonate-signaled plant immunity. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yue, A.; Zhao, J.; Yin, C.; Wang, M.; Du, W. WGCNA Reveals Hub Genes and Key Gene Regulatory Pathways of the Response of Soybean to Infection by Soybean mosaic virus. Genes 2024, 15, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabre, L.; Peyrard, S.; Sirven, C.; Gilles, L.; Pelissier, B.; Ducerf, S.; Poussereaul, N. Identification and characterization of a new soybean promoter induced by Phakopsora pachyrhizi, the causal agent of Asian soybean rust. BMC Biotechnol. 2021, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, S.K.; Sivalingam, P.N.; Sridhar, J.; Singh, D.; Haldhar, S.M.; Kaushal, P. Biotic stress inducible promoters in crop plants-a review. J. Agric. Ecol. 2017, 4, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambiagno, D.A.; Torres, J.R.; Alvarez, M.E. Convergent Epigenetic Mechanisms Avoid Constitutive Expression of Immune Receptor Gene Subsets. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 703667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkinen, K.; De, S. The significance of methionine cycle enzymes in plant virus infections. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2019, 50, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ge, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ouyang, X.; Jia, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; An, Y. A BTB/POZ domain-containing protein negatively regulates plant immunity in Nicotiana benthamiana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 600, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yang, C.; Liu, R.; Pang, J.H.; Zhao, W.S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, M.X.; Zhang, Z.G.; et al. A rice protein modulates endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis and coordinates with a transcription factor to initiate blast disease resistance. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Coronado, M.; Dias Araujo, P.C.; Ip, P.L.; Nunes, C.O.; Rahni, R.; Wudick, M.M.; Lizzio, M.A.; Feijó, J.A.; Birnbaum, K.D. Plant glutamate receptors mediate a bet-hedging strategy between regeneration and defense. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 451–465.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.; Kebede, M. In silico analysis of promoter region and regulatory elements of glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase encoding genes in Solanum tuberosum: Cultivar DM 1-3 516 R44. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatius, S.M.J.; Renu, K.; Muthukrishnan, S. Effects of fungal infection and wounding on the expression of chitinases and β-1, 3 glucanases in near-isogenic lines of barley. Physiol. Plant. 1994, 90, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozovaya, V.V.; Waranyuwat, A.; Widholm, J.M. β-l, 3-Glucanase and Resistance to Aspergillus flavus Infection in Maize. Crop Sci. 1998, 38, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.L.; Faris, J.D.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Liu, D.J.; Chen, P.D. Isolation and characterization of novel cDNA clones of acidic chitinases and β-1, 3-glucanases from wheat spikes infected by Fusarium graminearum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2001, 102, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Hernández, L.; Brodersen, P. Occurrence and Functions of m6A and Other Covalent Modifications in Plant mRNA. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.C.; He, C. m6A RNA methylation: From mechanisms to therapeutic potential. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e105977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, N.; Sheikh, A.H.; Hirt, H. Insights into the role of N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in plant-virus interactions. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0159824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoux, C.; Galletti, R.; Mammarella, N.; Gopalan, S.; Werck, D.; De Lorenzo, G.; Ferrari, S.; Ausubel, F.M.; Dewdney, J. Activation of defense response pathways by OGs and Flg22 elicitors in Arabidopsis seedlings. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 423–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]