Abstract

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) produced by Medicinal Aromatic Plants (MAPs) are bioactive signaling molecules that play key roles in plant defense, acting against pathogens and triggering resistance responses. Intercropping with VOC-emitting MAPs can therefore enhance disease resistance. This study investigated VOCs emitted by sage (Salvia officinalis) as potential resistance inducers in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) against Plasmopara viticola, the causal agent of downy mildew, under consociated growth conditions. Sage and grapevine plants were co-grown in an airtight box system for 24 or 48 h, after which grape leaves were inoculated with P. viticola. Disease assessments were integrated with grapevine leaf metabolic profiling to evaluate responses to VOC exposure and pathogen infection. Untargeted and targeted metabolomic analysis revealed that sage VOCs consistently reprogrammed grapevine secondary metabolism, without substantial differences between 24 and 48 h exposures. Lipids, phenylpropanoids, and terpenoids were markedly accumulated following VOC exposure and persisted following inoculation. Correspondingly, leaves pre-exposed to sage VOCs exhibited a significant reduction in disease susceptibility. Overall, our results suggest that exposure to sage VOCs induces signaling and metabolic reprogramming in grapevine. Further research should elucidate how grapevines perceive and integrate these signals, as well as the broader processes underlying MAP VOC-induced defense, and evaluate their translation into sustainable viticultural practices.

1. Introduction

European vineyards represent nearly 50% of global vine area and production [1], contributing not only to distinctive cultural landscapes and heritage but also to the economic value of agriculture [2]. However, the pursuit of high production standards has made viticulture one of the most pesticide-intensive agricultural sectors in Europe [3,4,5]. Among the most serious threats to viticulture is downy mildew (DM), caused by the oomycete Plasmopara viticola, which is considered one of the most devastating grapevine diseases. Control of DM accounts for the highest number of annual pesticide applications [6,7]. The widespread use of pesticides has led to significant environmental degradation, including soil and water contamination [8], biodiversity loss [9], the emergence of pesticide-resistant strains [10], and serious health risks for humans [11,12].

In response to increasing concerns from both the scientific community and society, strategies have been developed to reduce pesticide reliance in the management DM. These include the introduction of resistant cultivars [13], the development of predictive models for more targeted and timely applications [14], the adoption of advanced precision spraying technologies [15], and the use of alternative solutions to chemical pesticides [16,17,18]. Among these alternatives, one of the most promising is the use of compounds that can induce plant resistance. These substances trigger complex plant–pathogen interactions that activate the plant immune system [19]. Specifically, plants can develop a form of “immune memory” through a process called priming, which enhances or accelerates the activation of inducible resistance (IR) [20]. This response can result in the establishment of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and/or induced systemic resistance (ISR) [19]. SAR is typically initiated by pathogen attacks and involves the phytohormone salicylic acid and the activation of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins. In contrast, ISR is induced by beneficial organisms or abiotic stimuli and is mediated through the phytohormones ethylene and jasmonic acid [21].

Several compounds of different origins have been demonstrated to trigger defense responses and control P. viticola in grapevines. These compounds include chemicals such as benzothiadiazole, acibenzolar-S-methyl, fosetyl-Al, and potassium phosphonate [22]. They are classified as synthetic molecules, some of which are highly persistent in the environment and therefore forbidden in organic viticulture (EU 2021/1165). Resistance inducers of natural origin offer promising alternatives for sustainable and organic vineyard management [23]. Notable examples include laminarin (a beta-glucan extracted from the brown alga Laminaria digitata) and its sulfate derivatives [24,25,26]; chitosan (produced by the alkaline deacetylation of chitin obtained from insects, the exoskeleton of crustaceans, and fungal cell walls) [23,27,28]; and cerevisane (extracted from the cell walls of Saccharomyces cerevisiae) [29]. Other resistance inducers consist of living microorganisms, such as Trichoderma harzianum [30] or Pythium oligandrum [31], which have shown promising biocontrol activity against P. viticola through the stimulation of host defense mechanisms.

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the role of plant-emitted volatile organic compounds (VOCs) as signaling molecules capable of inducing resistance in grapevine against DM [32,33]. These compounds constitute a broad class of secondary lipophilic metabolites, characterized by low molecular weight (100–500 Da) and high vapor pressure (≥0.01 kPa at 20 °C). These physicochemical properties allow VOCs to permeate cellular membranes and diffuse through the air to reach nearby biological targets [34,35,36]. Based on their chemical structure and biosynthetic pathways, plant VOCs can be classified into four main classes: terpenoids, phenylpropanoids/benzenoids, fatty acid derivatives, and amino acid-derived compounds [37,38]. In general, these compounds are known as intra- and inter-plant signaling molecules, particularly under biotic and abiotic stress conditions [39,40,41]. The emission of VOCs in response to mechanical and herbivory damage has been widely demonstrated [39,40,42], and it is also well established that pathogen infection can trigger the release of specific VOCs such as methyl salicylate (MeSA), mono- and sesquiterpenes, heterocyclic compounds, green leaf volatiles (GLVs), and ketones [36,38,43]. These compounds can directly inhibit pathogen growth or indirectly activate SAR or ISR in neighboring plants, resulting in “associational resistance” [44].

Plant VOC-mediated communication occurs through a complex dynamic network of interactions that is only partially understood. Once released, VOCs can interact with neighboring plants via stomatal openings [45,46] or be absorbed into the cuticle due to their lipophilic properties [47,48]. Although some VOCs are present upon entry, others may persist in the cuticle and exert antimicrobial activity [47]. VOCs can partition between intercellular spaces and the cytosolic liquid phase, readily diffusing across cellular membranes. Once in the cytoplasm, they undergo enzymatic degradation, which aids in detoxification and facilitates their uptake [45,49]. These metabolic processes can also produce toxic intermediates for pathogens and initiate oxidative stress-like responses by consuming glutathione and NADPH [45].

Both intraspecific and interspecific VOC-mediated resistance induction has been demonstrated. Resistant grapevine cultivars have been shown to emit higher levels of defense-related VOCs in response to P. viticola infection compared to susceptible cultivars [43]. These compounds include mono- and sesquiterpenes (i.e., farnesene, nenolidol, ocimene, valencene, geranylacetone, β-ocimene, (E)-2-hexen-1-ol, humulene, limonene, and linalool), which correlate with reduced disease susceptibility [43,50,51,52,53,54]. Medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) produce a wide range of bioactive volatile metabolites (e.g., alkaloids, phenolics, terpenes, anthocyanins, and carotenoids) capable of inducing resistance in neighboring crops [55,56,57,58]. MAPs encompass approximately 17,500 species from families such as Lamiaceae, Apiaceae, Asteraceae, and Myrtaceae, with Lamiaceae being well-known for their antioxidant (e.g., carnosoic acid, carnosol, and rosmarinic acid) and antifungal (e.g., carvacrol, thymol, linalool, and p-cymene) properties [59].

MAP consociations are widely used to manage abiotic stresses or against insect pests; their role in controlling fungal pathogens is increasingly recognized [60,61]. For instance, MAPs from Lamiaceae and Amaryllidaceae families have shown efficacy in enhancing resistance against Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, and Phytophthora species in tomato and pepper [55,62,63]. Intercropping grapevines with the hoary stock (Matthiola incana), particularly during the flowering stage, resulted in a 50% reduction in DM incidence over two years [64]. Chemical analysis revealed 15 bioactive VOCs, including terpenoids, benzenoids, and aliphatics, with direct inhibitory effects on P. viticola when applied as VOCs on leaf disks. Linalool—a common VOC in MAPs belonging to Lamiaceae, Apiaceae, and Lauraceae families—primed grapevine defense responses to P. viticola, including the upregulation of defense-related genes and metabolic reprogramming of amino acid, phenylpropanoid, and terpenoid metabolisms [33]. VOCs emitted by Origanum vulgare have also been extensively studied using multi-omics approaches for their capacity to prime grapevine defense against P. viticola [32,59,65]. Intercropping vineyards with VOC-emitting MAPs therefore has the potential to enhance disease resistance in grapevines.

The present study aims to investigate the potential of VOCs emitted by Salvia officinalis (sage) as resistance inducers in grapevines against DM under consociation. To provide a proof of concept, sage—a species within the Lamiaceae family recognized for its production of antifungal compounds effective against oomycetes [59,66]—and grapevines were grown in a confined airtight box system for either 24 or 48 h, thereby exposing grapevines to sage VOCs. After consociation, grape leaves were artificially inoculated with P. viticola, and the resistance induction was evaluated by assessing the disease severity in comparison with leaves from non-consociated grapevines. The metabolic profiles of leaves from both consociated and non-consociated grapevines were evaluated in response VOC exposure and P. viticola inoculation, and compounds putatively involved in resistance were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

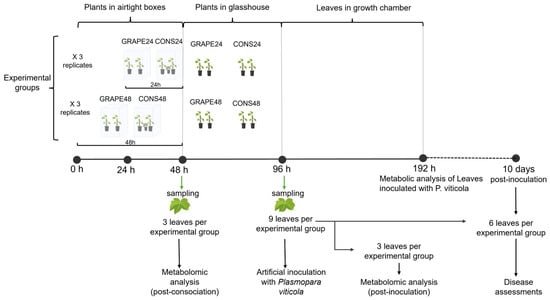

The experiment was conducted in the glasshouse of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Piacenza, Italy) using “consociation boxes”. The boxes were 39 cm long × 58 cm wide × 65 cm high; the structure was made of PVC tubes (16 mm in diameter) with walls of transparent polyethylene sheets, ensuring a watertight closure (Supplementary Material S1A). Each consociation box contained two 2-year-old cuttings of Vitis vinifera cv. Chardonnay grafted onto Kober 5BB rootstocks and grown in pots (13 × 15 cm; see Supplementary Material S1B for the canopy size), each with two primary shoots with 10–12 leaves per shoot, as well as one potted sage plant (Salvia officinalis; pots of 28 × 28 cm; see Supplementary Material S1C for the canopy size). The sage–grapevine consociation was conducted for 24 h (CONS24) in some boxes and for 48 h (CONS48) in others. The control treatment consisted of two grapevine plants enclosed in boxes without sage for 24 h (GRAPE24) or 48 h (GRAPE48). Each treatment was replicated three times (i.e., three boxes per treatment). Therefore, 12 boxes were used (3 for CONS24, 3 for CONS48, 3 for GRAPE24, and 3 for GRAPE48), with two grapevine plants per box. The experimental setup is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental setup.

At the end of each consociation period (24 or 48 h), the boxes were opened and the sage plants were removed to interrupt grapevine exposure to sage VOCs. One leaf per box (three leaves in aggregate) was then collected for metabolomic analysis (post-consociation). After 48 h, three leaves per box (nine leaves in aggregate) were collected for artificial inoculation with P. viticola. Four days post-inoculation (DPI), three inoculated leaves were used for metabolomic profiling (post-inoculation), while the remaining six were maintained under incubation conditions for disease severity assessment. The timing selected for metabolomic analysis (i.e., 4 DPI) was determined through a preliminary study in which leaves inoculated with P. viticola were analyzed at 1, 3, and 4 DPI (see Supplementary Material S2). At all sampling times, leaves were collected from the 3rd or 4th position below the first unfolded leaf from the apex of actively growing shoots, which are highly susceptible to P. viticola infection [67,68].

Sensors (Tinytag, Gemini data loggers, Chichester, West Sussex, UK) were placed inside watertight boxes to measure temperature (T, °C) and relative humidity (RH, %). During the 48 h periods, the average temperature in daylight was 26.6 ± 2.3 °C, while it was 24.7 ± 1.7 °C in the dark, with no differences between GRAPE and CONS boxes. After box closure, RH increased to 100% in approximately 4 h, with no further variation. Sunlight inside the glasshouse was complemented with an LED lamp (MIR/S5, TEC-MAR, Lodi, Italy) providing an output of 28750 lumens, a color temperature of 4000 °K, and a CRI (Color Rendering Index) > 90; the lamp was operated 12 h per day. Before and after the period in watertight boxes, grapevine plants were grown in the glasshouse under the lamp, with an average T of 24.4 ± 2.5 °C and 22.5 ± 2.0 °C in daylight and in the dark, respectively, and an average RH of 67.7 ± 15.3%.

A preliminary experiment showed that, after 12 h, the main VOCs released by sage into the box atmosphere were o-xylene, p-xylene, alpha-pinene, linalool, camphene, beta-pinene, D-limonene, eucalyptol, beta-thujone, and camphor (see Supplementary Material S3).

2.2. Metabolomic Analysis

Each leaf was carefully placed into a 15 mL Falcon™ tube (Sigma Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germania) and immediately frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen. Once frozen, the leaves were finely ground using a mortar and pestle, and the resulting powder was transferred into 2 mL Eppendorf® (Eppendorf Safe-Lock® Tubes, Hamburg, Germany) tubes and stored at −18 °C until further analysis. For the extraction, a total of 0.3 g of powdered tissue per sample was used.

Metabolites were extracted using an 80% (v/v) methanol (MeOH) solution acidified with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. The samples underwent ultrasonic treatment using a sonicator (Fisher Scientific model FB120, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C (Eppendorf 5810R, Hamburg, Germany). The supernatants were subsequently filtered through 0.22 µM cellulose membrane filters and transferred into glass vials for analysis. Metabolomic profiling was performed in duplicate for each leaf sample (technical replicates) using UHPLC/IM-QTOF-MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry featuring an ion mobility quadrupole/time-of-flight system), as described by [69]. Briefly, chromatographic separation was conducted using an Agilent InfinityLab Poroshell 120 pentafluorophenyl (PFP) column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.9 μm) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a binary mixture of water and acetonitrile, acidified with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid as the mobile phase (LC-MS grade, VWR, Milan, Italy). Mass spectrometry was operated in positive polarity using full SCAN (100–1200 m/z) with a nominal mass resolution of 30,000 FWHM, as previously reported by Bouaicha et al. [70]. Comprehensive details on the metabolomic profiling are provided in the Supplementary Materials S4.

2.3. Inoculation of P. viticola and Disease Assessment

Artificial inoculation was performed using a sporangial suspension obtained as follows. A population of P. viticola collected from different commercial vineyards and untreated plots located in Northern Italy between 2023 and 2024 was maintained in a glasshouse on potted plants of V. vinifera cv. Merlot. Before each inoculation, leaves with fresh DM lesions were cut from plants, enclosed in moistened polyethylene bags, and incubated in a growth chamber for 24 h at 20 °C under a 12 h photoperiod to stimulate the production of fresh sporangia. These sporangia were then gently removed from the lesions with a sterile cotton swab and suspended in sterile distilled water. The sporangial concentration was then determined using a hemocytometer (Bürker-Türk, BLAUBRAND, Wertheim Germany) under a bright-field optical microscope (40× magnification) and adjusted to 1 × 105 sporangia/mL.

Chardonnay leaves from consociation boxes were inoculated by distributing the sporangial suspension on the abaxial leaf blade using a manual nebulizer. To ensure infection, inoculated leaves were sealed in Petri dishes (90 mm in diameter) with Parafilm to maintain a saturated atmosphere and incubated at 20 °C under a 12 h photoperiod. After 24 h, leaf surfaces were dried out with sterile filter paper to remove excess moisture and incubated again under the same conditions until the 10th day after inoculation. At this time, leaves were observed with a stereomicroscope at 10× magnification to detect DM-sporulating lesions. Disease severity (0–100%) (i.e., the percentage of leaf area showing typical DM symptoms with white sporulation) was visually assessed using the EPPO scale (1 = no disease; 2 = <5%; 3 = 5–10%; 4 = 10–25%; 5 = 25–50%; 6 = 50–75%; 7 = 75–100%) [71]. Average DM severity was then calculated using the intermediate severity value of each class (i.e., 1 = 0; 2 = 2.5%; 3 = 7.5%; 4 = 17.5%; 5 = 37.5%; 6 = 62.5%; 7 = 87.5%). Sporulation intensity (i.e., the abundance of sporangiophores per surface unit of diseased tissue) was assessed using the following categorical scale: 0 = no sporulation, 1 = 1–20 sporangiophores, 2 = >20 but not very dense, and 3 = very dense sporulation. Leaves were then immersed in a beaker containing 5 mL of distilled water and vortexed for 5 min. The concentration of sporangia in the resulting suspension was determined by counting the number of sporangia per mL (sporangia/mL) using a hemacytometer under a light microscope; 4 replicate counts were performed for each suspension. All assessments and counts were conducted by experts using blinded samples.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

For metabolomics, UHPLC/QTOF-MS raw data alignment and annotation were performed using MS-DIAL software (version 4.90) [72] and two different MS/MS libraries: Fiehn/Vaniya natural product library (https://systemsomicslab.github.io/compms/msdial/main.html, date of access: 15 March 2023) and BMDMS-NP [73]. According to COSMOS standards in metabolomics [74], a level 2 confidence in annotation (putatively annotated compounds) was achieved. Data filtering and normalization were then performed using Mass Profiler Professional B.12.6 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The data acquired from MS-DIAL were initially processed using Mass Profiler Professional B.12.06 (Agilent Technologies). The raw abundances of the annotated features were normalized to the 75th percentile, log2-transformed, and baseline-corrected to the median of all samples. The 75th percentile normalization was adopted to reduce technical variation and improve comparability across samples. The dataset was initially explored using hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA; Euclidean distance) as an unsupervised multivariate approach to identify data patterns. Before conducting supervised analysis, the Boruta algorithm was applied using the “Boruta” R package (version 4.2.3), based on a random forest algorithm approach, to identify and confirm significant metabolites for discrimination. The model was constructed using 100 permutations and further optimized by selecting the lowest number of orthogonal predictive components (n = 1) to ensure the consistency in ANOVA partitioning. To analyze the specific effects of the different experimental factors, i.e., the consociation length (24 h and 48 h), treatment (GRAPE and CONS), and their interaction, a supervised ANOVA Multiblock Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis (AMOPLS-DA) was performed using R software (v. 4.2.3) with the “rAMOPLS” package (v. 0.2). This method allowed for the decomposition of the total data variance and isolation of the variation attributable to each factor and their interactions. The results were expressed as the relative sum of squares (RSS), representing the percentage of variability explained by each factor; the residual structure ratio (RSR), indicating the consistency of ANOVA attribution relative to the residuals; the p-value, denoting the statistical significance of each factor; and the principal predictive components, corresponding the highest block contributions associated with each factor.

The analysis identified markers that most strongly discriminated between the significant factors. The 50 markers with the highest VIP2 (Variable Importance in Projection) scores were selected and analyzed, as their role as primary biomarkers represents the model’s discriminative capacity. VIP2 is a metric used to identify and evaluate variable importance within a multivariate regression model. Binary comparisons were subsequently performed, such as comparing GRAPE vs. CONS, using a supervised Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA; SIMCA 16, Umetrics, Malmö, Sweden). The model was ANOVA cross-validated, permutated (999 permutations), and inspected for the presence of outliers using Hotelling’s T2 test. This analysis enabled the extraction of metabolites discriminating between treatments. Variable importance in projection (VIP) metabolites with scores higher than 1.4 were selected as the primary biomarkers representing the model’s discriminative capacity, and fold change (FC) analysis was conducted to identify trends of increased or decreased accumulation in each group.

Disease severity and sporangial concentration were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA), with treatment (GRAPE and CONS), consociation length (24 h or 48 h), and their interaction considered as fixed factors. Three replicates (boxes) were used, each obtained by averaging the data from six leaves. Disease severity data were transformed using the arcsine function prior to ANOVA, while sporangial concentration data were normalized using the natural logarithm (ln) function. Averages were compared using the Least Square Difference (LSD) test at p = 0.05 using the ‘agricolae’ package in R Studio (v. 4.4.0). Sporulation intensity was analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test in R Studio.

3. Results

3.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Metabolic Profiles

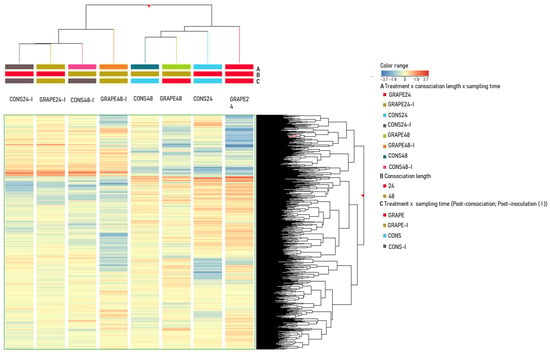

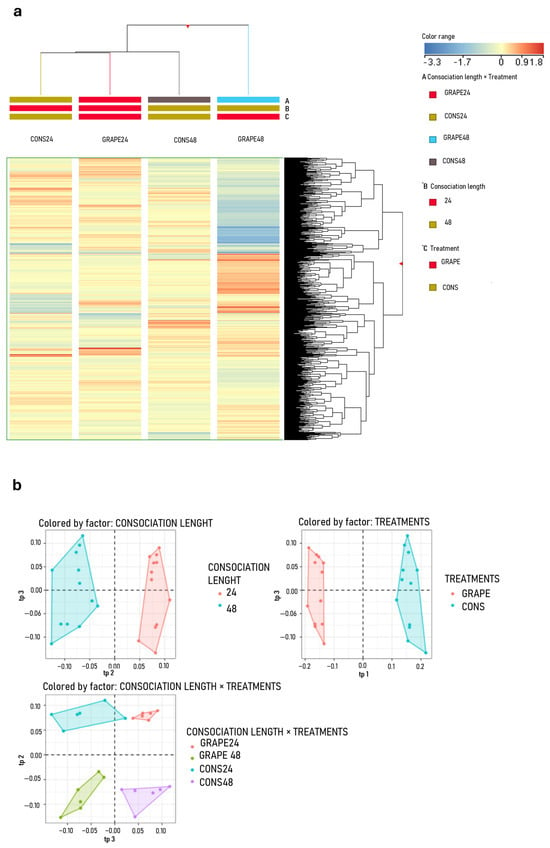

The metabolomic analysis resulted in the annotation of 1210 putatively identified metabolites, as reported in the Supplementary Materials S7, including metabolite classes; scores of identification; average S/N, MS, and MS/MS spectra; and other peak information. Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) examining the effects of treatment (GRAPE and CONS), consociation length (24 and 48 h), and sampling time (post-consociation and post-inoculation) on similarities and dissimilarities among samples (Figure 2) highlighted significant differences in metabolic signatures between leaves collected post-consociation from both GRAPE and CONS and those collected post-inoculation with P. viticola. In the following sections, data were analyzed separately for post-consociation and post-inoculation phases. The post-consociation analysis considered the metabolic profiles of leaves collected immediately after box opening, focusing on interspecific signaling mediated by VOCs, with particular emphasis on the potential priming of grapevines induced by sage-emitted VOCs. The post-inoculation analysis evaluated the potential resistance responses that VOCs emitted by sage may have triggered in grapevine leaves.

Figure 2.

Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was performed based on the metabolic profiles of grapevine leaves consociated with sage or maintained without sage (i.e., treatment with levels CONS and GRAPE, respectively) for 24 or 48 h (i.e., consociation length), and sampled at both post-consociation and post-inoculation times (i.e., sampling time). Leaves were analyzed at two stages of the experiment: post-consociation and after inoculation with sporangia of Plasmopara viticola (I). For example, GRAPE48-I indicates leaves sampled from grapevine plants not consociated with sage, maintained in boxes for 48 h, inoculated 48 h after consociation end, and analyzed 96 h post-inoculation; CONS48 indicates leaves sampled from grapevine plants consociated with sage, maintained in boxes for 48 h, and then analyzed. The analysis was performed using Ward’s linkage and Euclidean distance applied to normalized metabolite abundances. In the legend, colors refer to each combination (A, B, or C) of factors (treatment, consociation length, and sampling time).

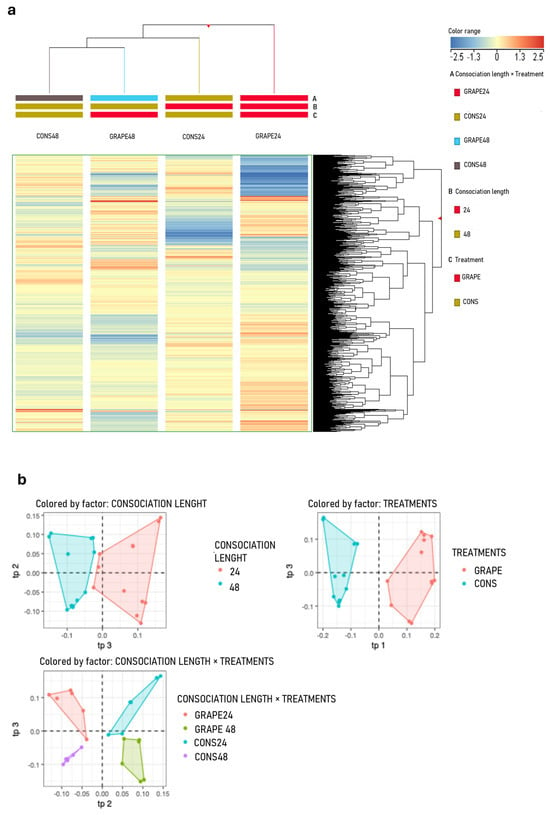

3.2. Post-Consociation Analysis

The HCA revealed that the treatment factor (GRAPE and CONS) was the main discriminating factor for the leaf metabolome after consociation with sage (Figure 3a). Supervised AMOPLS-DA analysis confirmed that treatment accounted for 69.0% of the total variability in the dataset, while consociation duration and the interaction between the two factors accounted for 2.4 and 2.3% of total variability, respectively (Figure 3b). Model parameters are reported in the Supplementary Materials S5.

Figure 3.

(a) Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was performed based on the metabolic profiles of grapevine leaves consociated with sage or maintained without sage (i.e., treatment with levels CONS and GRAPE, respectively) for 24 or 48 h (i.e., consociation length), sampled post-consociation. The analysis was performed using Ward’s linkage and Euclidean distance on normalized metabolite abundances. In the legend, colors refer to consociation length (B), treatment (C), and their interaction (A). (b) AMOPLS-DA score plots illustrating the predictive components (Tp) identified in the metabolomic analysis, representing the effects of treatment, consociation length, and their interaction.

A specific OPLS-DA model comparing the GRAPE and CONS groups showed strong performance in capturing the main sources of variation associated with treatment, with high discrimination between the two groups The model explained 52.2% of the cumulative variance in the predictor matrix (R2X = 0.522) and accounted for 99.8% of the variance in the response variable (R2Y = 0.998). The model demonstrated excellent predictive performance (Q2 = 0.961) and was significantly cross-validated with ANOVA (p < 0.0001).

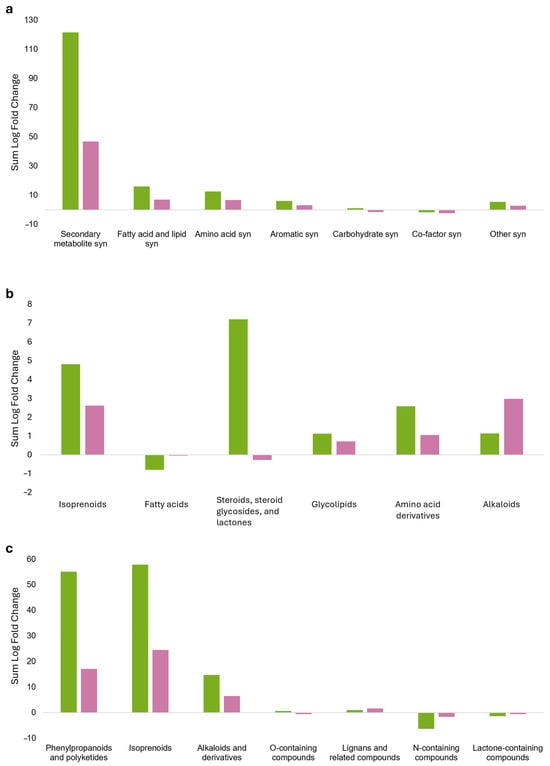

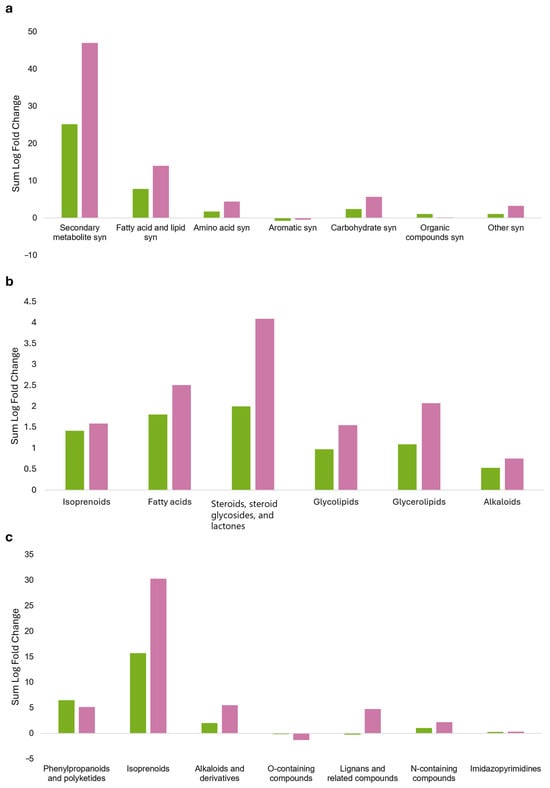

Metabolic pathways constructed with the most discriminant, treatment-specific metabolites (VIP > 1.4) identified through OPLS-DA (see Supplementary Material S8A) are shown in Figure 4. Exposure to sage VOCs did not significantly affect the primary metabolism of grapevine but strongly modulated secondary metabolism (Figure 4a). A general accumulation of lipids was observed, particularly in the CONS24 group. This increase primarily involved isoprenoids, including long-chain polyterpenoids and triterpenes, as well as vitamin K (a naphthoquinone terpenoid) and its derivatives, and cucurbitacin glycosides. In particular, a significant accumulation of steroids was recorded in CONS24, characterized by the presence of 12-hydroxysteroids, while a decrease in 21-hydroxysteroids was observed. In addition, steroidal saponins and withanolides (a group of naturally occurring steroidal lactones) also accumulated. Among the examined lipids, only glyceryl linolenate (a derivative of linoleic acid) exhibited an increasing pattern. A positive modulation of glycolipids was also observed (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Pathway plots concerning the differential VIP marker metabolites, discriminating between grapevine plants consociated with sage for 24 (green bars) and 48 h (pink bars) under airtight box conditions. Leaves collected from grapevine plants were analyzed using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry featuring an ion mobility quadrupole/time-of-flight system (UHPLC/IM-QTOF-MS). (a) Global metabolic pathway; (b) lipid metabolic pathway; (c) secondary metabolic pathway. The bar chart shows logarithmic fold change (Log FC), which quantifies the magnitude of change between the treatment (consociation with sage) and the untreated control (without sage); positive values indicate increased abundance, whereas negative values indicate decreased abundance. Note that the y-axis scale differs among panels (a–c).

The accumulation of secondary metabolites was higher in the CONS24 group, with phenylpropanoids and polyketides contributing to enhanced flavonoid accumulation, with a high prevalence of glycosylated forms (flavonoid-7-O-glycosides and flavonoid-3-O-glycosides). Moreover, flavonoids conjugated with glucuronic acid were detected, together with methylated and prenylated variants. These were accompanied by isoflavones, coumarins (with and without sugar moieties), and resorcinols. Single occurrences of curcuminoids, stilbenes, acetophenones, and annonaceous acetogenins were also detected. Similarly, the isoprenoid pathway was elicited, with increased accumulation of triterpenes, including triterpene saponins and diterpenes, their glycosidic forms, and kaurene diterpenes. In addition, sesquiterpenes (i.e., germacrene and eudesmane), xanthophylls, and iridoid glycosides also accumulated. Conversely, the production of aconitane-type diterpenoid alkaloids showed a marked decrease. A diverse set of alkaloids accumulated, including yohimbine-type indole alkaloids, camptothecins, dihydrobenzophenanthridine alkaloids, and matrine-type quinolizidine alkaloids (Figure 4c).

3.3. Metabolomics Change Post-Inoculation

The HCA (Figure 5a) showed that the treatment was the main factor influencing the metabolome of infected leaves, with CONS24 and CONS48 clustering together, while GRAPE48 showed a distinct metabolic profile, forming a separate cluster. AMOPLS-DA analysis confirmed treatment as the main factor, explaining 36.9% of the total variability in the dataset; consociation duration and the interaction between the two factors accounted for 6.4 and 4.1% of total variability (Figure 5b), respectively, and the model parameters are reported in the Supplementary Materials S6.

Figure 5.

(a) Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was performed based on the metabolic profiles of grapevine leaves consociated with sage or maintained without sage (i.e., treatment with levels CONS and GRAPE, respectively) for 24 or 48 h (i.e., consociation length), sampled post-inoculation (96 hpi). Inoculation was performed 48 h after the end of consociation. The analysis was performed using Ward’s linkage and Euclidean distance on normalized metabolite abundances. In the legend, colors refer to consociation length (B), treatment (C), and their interaction (A). (b) AMOPLS-DA score plots illustrating the predictive components (Tp) identified in the metabolomic analysis, representing the effects of treatment, consociation length, and their interaction.

The OPLS-DA model comparing the GRAPE and CONS groups strongly captured the main sources of variation associated with treatment, with high discrimination between the two groups. The model explained 57% of the cumulative variance in the predictor matrix (R2X = 0.57) and accounted for 99.8% of the variance in the response variable (R2Y = 0.99). The model showed a strong predictive performance, with a Q2 value of 0.913, and was significantly cross-validated with ANOVA (p < 0.0001).

The metabolic pathways constructed from the most discriminant, treatment-specific metabolites (VIP > 1.4) identified by OPLS-DA modeling (see Supplementary Material S8B) are shown in Figure 5.

The primary metabolism of leaves collected from CONS24 and CONS48 did not exhibit significant alterations compared with GRAPE24 and GRAPE48 (Figure 5a). In contrast, the secondary metabolism was strongly modulated in both CONS24 and CONS48, with a wider modulation of secondary metabolites observed in CONS48 (Figure 6a). Lipid accumulation was mainly observed for isoprenoids, including cardenolides, cucurbitacins, and their glycosides. Steroids and steroidal saponins, including bufadienolides, accumulated alongside glycerolipids (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Pathway plots of differential VIP marker metabolites measured at 96 h post-inoculation (hpi) that discriminate the effects of grapevine consociation with sage for a period of 24 (green bars) or 48 h (pink bars) under airtight box conditions. Inoculated leaves were analyzed using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry featuring an ion mobility quadrupole/time-of-flight system (UHPLC/IM-QTOF-MS). (a) Global metabolic pathway; (b) lipid metabolic pathway; (c) secondary metabolic pathway. The bar chart shows logarithmic fold change (Log FC), which quantifies the magnitude of change between the treatment (consociation with sage) and control conditions (without sage); positive values indicate increased abundance, while negative values indicate decreased abundance. Note that the y-axis scale differs among panels (a–c).

With respect to the secondary metabolism, the isoprenoid pathway was the most strongly activated, predominantly involving triterpenes, triterpene saponins, and diterpenes such as colensane and aconitane-type diterpenoid alkaloids. Moreover, xanthophylls and sesquiterpenes like eudesmane, as well as iridoids, also accumulated. Other pathways were positively modulated to a lesser extent, including phenylpropanoids—mainly flavonoids and isoflavones in both glycosidic and aglycone forms—followed by p-coumaric acids, coumarins, and coumestans showing intermediate accumulation, and by alkaloids and lignans (Figure 6c).

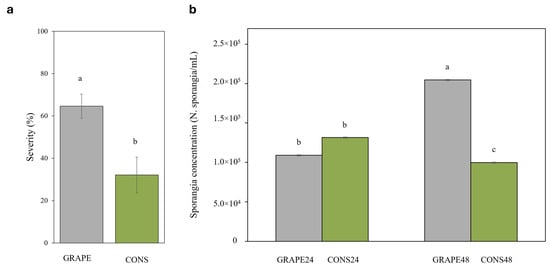

3.4. Disease Assessments

Based on ANOVA, the treatment was the only significant factor affecting disease severity (p = 0.003), accounting for 77% of the variance. Leaves collected from GRAPE boxes showed approximately twice the disease severity compared with leaves collected from CONS boxes (64.6 ± 5.7% and 32.1± 8.5%, respectively). The sporulation intensity, however, was not significantly affected by treatment. The number of sporangia produced on leaves was significantly affected by both treatment and its interaction with the consociation length (p < 0.001). The sporangial concentration in inoculated leaves of GRAPE48 (2.05 × 105 ± 0.09) was significantly higher than in all other combinations, whereas GRAPE24 (1.09 × 105 ± 0.05) and CONS24 (1.32 × 105 ± 0.1) did not differ significantly from each other and were both higher than CONS48 (9.9 × 104 ± 0.24) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Disease severity (graph a) and number of Plasmopara viticola sporangia per mL of suspension (graph b) on grapevine leaves consociated with sage (CONS, green bars) or maintained without sage (GRAPE, gray bars) for either 24 or 48 h under airtight box conditions. After the consociation period, the boxes were opened and the sage plants were removed; after 48 h in open air, leaves were artificially inoculated with a sporangial suspension of P. viticola. Disease and sporulation assessments were performed 10 days after inoculation. Sporangial suspension was obtained by immersing leaves in a beaker with distilled water and vortexing for 5 min, and the number of sporangia per mL (sporangia/mL) was counted under a light microscope. In (a), the effect of the consociation period was averaged because the interaction consociation × time was not significant. Data are the averages of three boxes (two leaves per box), and whiskers are standard errors. Different letters show significant differences according to the LSD Test (p ≤ 0.05).

4. Discussion

Our study investigates the potential of consociation, defined here as the proximity growth of two or more plant species, to control P. viticola, the causal agent of downy mildew (DM) in grapevine. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to examine chemical communication via volatile organic compounds (VOCs) between V. vinifera and S. officinalis and to evaluate its impact on grapevine metabolism and DM severity. By integrating metabolic profiling, we provide insights into how sage–grapevine consociation influences grapevine responses to VOC exposure and pathogen infection.

In viticulture, consociation with aromatic plants has mainly been investigated in relation to its effects on yield and grape quality [75], the organoleptic profile of grapes [76], and soil functions [77]. The potential of consociation for disease control, however, has so far been examined in only one study. Deng et al. [64] reported a reduction in DM incidence through intercropping M. incana (hoary stock) with grapevine under vineyard conditions. In that study, VOCs emitted by hoary stock exhibited antifungal activity, with 17 compounds (mainly terpenoids, benzenoids, and aliphatics) demonstrating consistent inhibitory effects against P. viticola [64].

In contrast to that study, we conducted controlled experiments using potted grapevine and sage plants enclosed in airtight boxes to prevent VOC dispersion during the consociation period. This approach aimed to provide proof-of-concept evidence for the potential interaction between sage and grapevine, focusing on metabolic modifications and induced resistance to P. viticola, rather than demonstrating effects under vineyard conditions. Although we acknowledge that the enclosed environment could have imposed some stress on the plants, the comparison between consociated grapevines (CONS) and grapevine-only controls (GRAPE) allowed us to isolate the effect of sage VOCs and rule out potential root-to-root interactions mediated by exudates, as may occur in field intercropping systems [78].

4.1. Main Metabolic Changes in Consociated Grapevine Leaves

Untargeted and targeted metabolomic analyses revealed that sage-derived VOCs modulated grapevine leaf metabolism, with no substantial differences between 24 and 48 h of consociation. While primary metabolism remained relatively stable, consistent with the minor role of primary pathways in elicitor-triggered responses [79], secondary metabolism showed marked changes. Pathways related to lipids, phenylpropanoids, and terpenoids were significantly reprogrammed following both consociation and subsequent pathogen inoculation. The activation of these pathways persisted after pathogen inoculation, specifically at 96 hpi, although with reduced intensity. The strongest metabolic readjustments involved the accumulation of secondary metabolites, which are known to play crucial roles in plant defense [32,33,79,80,81]. Specifically, an accumulation of terpenoids was observed in grape leaves following consociation, especially triterpenes such as limonoids and triterpene saponins, followed by diterpenes and, to a lesser extent, sesquiterpenes.

The role of terpenes and terpenoids as plant defense compounds against biotic stresses is well-documented [82], particularly regarding their ecological interactions with insects [83]. In contrast, their involvement in plant–pathogen interactions remains poorly understood [84]. Many of the triterpenes identified in our study have not been extensively studied in grapevine but are generally considered to be constitutive defense molecules (phytoanticipins) rather than inducible phytoalexins [85,86,87]. The accumulation of triterpenoids in healthy grapevine tissues has been reported following application of the elicitor chitosan [88], and compounds belonging to this class (specifically β-Amirina) have been proposed as resistance markers against P. viticola [89]. Sesquiterpenes were less abundant than triterpenes; nevertheless, their relevance was highlighted through the defense mechanisms of grapevines resistant to P. viticola, as revealed by both transcriptomic [90] and volatilome [54,91,92] analyses.

Triterpenoid accumulation was highly associated with steroid accumulation (phytosteroids, particularly steroidal saponins) observed in the primary lipid metabolism, as both share the same biosynthetic precursor. In plants, steroidal saponins, like other plant antitoxins, act as a line of defense against pathogen infection [93,94,95].

Polyterpenoids, including cucurbitacins, cardenolides, and bufanolides, were also observed in our analysis. These compounds are known for their action against biotic stressors [96,97]. Given their accumulation in grapevine leaves following consociation with sage, it would be intriguing to explore their role in V. vinifera. Inoculated leaves also exhibited increased levels of fatty acids and glycerolipids (1-monoacylglycerols). Lipids and fatty acids play an important role in the defense of grapevines against DM, and increased levels of neutral lipids, saturated fatty acids and monogalactosyldiacylglycerol have been proposed as markers of reduced susceptibility to P. viticola [98].

Our results also highlight significant modulation of phenylpropanoids; flavonoids (including glycosylated forms), isoflavonoids, and coumarins accumulated in grapevine leaves after both the sage–grapevine consociation and P. viticola inoculation. These compounds are known for their antioxidant properties and protective roles against biotic and abiotic stress in grapevines [99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. Phenolic compounds, such as phenylpropanoids and flavonoids, are considered key factors distinguishing resistant from susceptible cultivars [106]. Chitarrini et al. [52] found high concentrations of these compounds in P. viticola-infected samples compared to uninoculated controls at 96 hpi and proposed their involvement as biomarkers of resistance to P. viticola in the resistant ‘Bianca’ grapevine cultivar. Some compounds found in our study (namely, the coumarin fraxin and various kaempferol derivatives) were also detected by Chitarrini et al. [52]. The detection of antifungal flavonoid phytoalexins, such as coumestans and sakuranetin, further supports the activation of defense responses [33,59,65,107,108,109,110,111,112].

Interestingly, stilbenes—key grapevine phytoalexins—were not significantly upregulated in our consociated leaves. These compounds are well-documented in the literature for their important role in grapevine defense against biotic stress, including P. viticola [113]. However, recent findings suggest that their role may vary depending on several factors [32,90].

4.2. Downy Mildew in Consociated Grapevine Leaves

A significant reduction in both disease severity and sporulation was observed in inoculated leaves pre-exposed to sage VOCs, demonstrating reduced susceptibility to the pathogen due to sage consociation. This effect could be related to the three possible mechanisms: (i) VOC-induced priming of grapevine plants; (ii) direct activation of grapevine defense responses by exposure to sage VOCs; and (iii) direct action of VOCs on the pathogen.

The first hypothesis refers to priming, i.e., a subtle, initial metabolic response of the plant that enables a more prompt and robust reaction to future stress [114]. In our study, a significant metabolic shift was observed in grape leaves during consociation with sage plants, which decreased following the inoculation with P. viticola, suggesting that some accumulated compounds played a role in the defense against the pathogen challenging the plant 48 h later. Our results are in general agreement with previous studies demonstrating priming following exposure to oregano oil vapors [32,59,65] or pure VOCs (i.e., linalool, 2-phenylethanol and β-cyclocitral) [33,115]. Metabolic analysis of inoculated leaves was conducted at 96 hpi, which may have prevented the detection of some early post-inoculation responses that could more directly support the priming hypothesis. Further studies analyzing the metabolic profiles of grape leaves consociated with sage and subsequently inoculated with P. viticola at 24 and 48 hpi would be useful for better understanding this aspect.

The second hypothesis refers to VOC-triggered activation of the defense-related metabolites discussed above; unlike priming, these metabolites may not be activated in response to pathogen challenge (as in priming) but instead reflect a preventative accumulation of protective compounds initiated during VOC exposure [116]. This preventative accumulation may be used by the plant in the early stages of P. viticola infection in grapevine leaves. Plants are known to absorb VOCs through stomata [45,46] and potentially metabolize them, thereby triggering redox changes and defense responses [47,117,118]. Although glutathione metabolites were not detected, strong ROS scavengers were observed among phenylpropanoids and isoprenoids, including xanthophylls, which are known to mitigate oxidative stress. This observation supports earlier findings showing that exposure to oregano EO downregulates photosynthetic genes and triggers antioxidant defenses [63].

The third hypothesis, referring to a direct action of VOCs deposited on or absorbed by leaves, appears unlikely because sage-specific metabolites were not detected in the tissues of consociated grapevine leaves. Indeed, none of the terpenoid VOCs emitted by sage were detected in our grapevine leaves, despite their identification in the sage volatilome (i.e., o-xylene, p-xylene, α-pinene, linalool, camphene, β-pinene, D-limonene, eucalyptol, β-thujone, and camphor, as detected in the preliminary study shown in SM3) and sage EO (i.e., eucalyptol, α-thujone, β-thujone, and camphor) [119,120,121,122,123,124,125]. The terpenoids identified in our study (e.g., triterpenes) are biosynthesized via the oxidosqualene cycle, which is distinct from the short-chain terpene biosynthesis of polyisoprenyl diphosphates, typical of sage VOCs [126]. Thus, the accumulated terpenoids observed in our study appear to be endogenously synthesized by grapevine in response to VOC exposure rather than absorbed from the air. This result, however, does not contradict previous works demonstrating a direct action of VOCs on P. viticola [33,50,127]. The presence of typical sage VOCs was confirmed in the air of boxes in preliminary tests, but their concentration was very low. Possibly, this concentration—together with a short consociation time (24 or 48 h)—was insufficient to cause accumulation in foliar tissues at levels that can be detected by our analysis and to exert a direct effect on the pathogen. Specific assays targeting the direct effects of sage-emitted VOCs on P. viticola should be conducted to further investigate this aspect.

5. Conclusions

Our findings provide the first evidence that consociation with sage results in substantial metabolic changes in grapevine leaves, with an over-accumulation of several compounds contributing to an enhanced defense against P. viticola infection. Overall, our results support the hypothesis that sage VOCs elicit both direct signaling and metabolic reprogramming in grapevines. Our study further supports the idea that airborne terpenes are recognized as immune signals in systemic tissues of neighboring plants, inducing phytohormone signaling pathways and defense-related gene expression [97]. Further studies are nevertheless needed at the cellular, biochemical, physiological, and gene expression levels to better understand the relationships between VOCs emitted by sage, the mechanisms by which grapevines perceive and integrate terpene signals, the role of over-expressed compounds, and the enhanced resistance of consociated grapevine leaves. Possible direct effects of sage-emitted VOCs on P. viticola should also be further investigated.

It can be speculated that, under vineyard conditions, aromatic plants may act as continuous, low-level sources of natural VOCs, thereby increasing resistance to P. viticola infection during the growing season. This possibility requires further investigation to unravel the mechanisms of VOC signaling and enhanced resistance to biotic stressors, as well as field-level validation. Such studies should also consider plant metabolism under continuous VOC exposure, grape yield and quality, and additional benefits beyond disease control, including pollinator support, aesthetic enhancement, and potential value-added products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020201/s1. S1A–C: Images of the experimental boxes and plants used for the consociation of sage and grapevine; S2: Unsupervised HCA for the preliminary evaluation of the optimal timing to assess the effect of sage–grapevine consociation on the grapevine leaf metabolic profile following infection with Plasmopara viticola; S3: Preliminary sampling and detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) produced by sage. Ref. [128] is cited in the Supplementary Materials; S4: Detailed description of the UHPLC/IM-QTOF-MS metabolic analysis; S5: AMOPLS-DA model parameters for post-consociation; S6: AMOPLS-DA model parameters for post-inoculation; S7: Annotation of putative metabolites; S8: OPLS-DA model parameters and VIP fold change values for the analysis of grapevine leaves following consociation with sage (post-consociation; S8A) and inoculation with Plasmopara viticola (post-inoculation; S8B).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R.; methodology, V.R., T.C. and L.L.; formal analysis, L.Z., I.R., V.F., C.C. and M.F.B.; investigation, M.F.B. and C.C.; data curation, L.Z., G.F., I.R., V.F. and M.F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.B., I.R., V.F. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, G.F., V.R., L.L. and T.C.; visualization, M.F.B.; supervision, V.R. and G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author in accordance with the authors’ data use agreement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Giulia Leni for assisting with the preliminary analysis of VOCs in the air and Margherita Furiosi, Luca Nassi, and Paolo Debenedettis for their collaboration in some practical work. Monica Fittipaldi Broussard and Ilaria Ragnoli were supported by the Doctoral School on the Agro-Food System (Agrisystem) of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Piacenza, Italy). During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Writefull for the purposes of language revision. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eurostat. Vineyards in the EU—Statistics. European Union. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Vineyards_in_the_EU_-_statistics (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Straffelini, E.; Wang, W.; Tarolli, P. European Vineyards and Their Cultural Landscapes Exposed to Record Drought and Heat. Agric. Syst. 2024, 219, 104034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, A.; Beaumelle, L.; Giffard, B.; Alonso Ugaglia, A. Harnessing Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services to Safeguard Multifunctional Vineyard Landscapes in a Global Change Context. In The Future of Agricultural Landscapes, Part III; Bohan, D.A., Dumbrell, A.J., Vanbergen, A.J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 65, pp. 305–335. ISBN 0065-2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Bauer, T.; Strauss, P.; Kratschmer, S.; Daniela, P.; Blanca, P.; Gema, L.; José, G.; Muriel, G.; Johann, G.; et al. Effects of Vegetation Management Intensity on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services in Vineyards: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 2484–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Gold, K.M.; Combs, D.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Jiang, Y. Deep Semantic Segmentation for the Quantification of Grape Foliar Diseases in the Vineyard. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 978761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, B.; Zito, S.; Calonnec, A. Climate vs Grapevine Pests and Diseases Worldwide: The First Results of a Global Survey. OENO One 2017, 51, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffolatti, S.L.; Lecchi, B.; Maddalena, G.; Marcianò, D.; Stuknytė, M.; Arioli, S.; Mora, D.; Bianco, P.A.; Borsa, P.; Coatti, M.; et al. The Management of Grapevine Downy Mildew: From Anti—Resistance Strategies to Innovative Approaches for Fungicide Resistance Monitoring. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2024, 131, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, Environment, and Food Safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, M.; Falquet, L.; Fragnière, L.; Brown, A.; Bacher, S. Effects of Pesticides on Soil Bacterial, Fungal and Protist Communities, Soil Functions and Grape Quality in Vineyards. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2024, 5, e12327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, F.; Molitor, D.; Evers, M.; Bleunven, D. Fungicide Sensitivity Profiles of the Plasmopara Viticola Populations in the Luxembourg Grape-Growing Region. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 1, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Teysseire, R.; Barron, E.; Baldi, I.; Bedos, C.; Chazeaubeny, A.; Le Menach, K.; Roudil, A.; Budzinski, H.; Delva, F. Pesticide Exposure of Residents Living in Wine Regions: Protocol and First Results of the Pestiprev Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Gai, L.; Harkes, P.; Tan, G.; Ritsema, C.J.; Alcon, F.; Contreras, J.; Abrantes, N.; Campos, I.; Baldi, I.; et al. Pesticide Residues with Hazard Classifications Relevant to Non-Target Species Including Humans Are Omnipresent in the Environment and Farmer Residences. Environ. Int. J. 2023, 181, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadalini, S.; Puopolo, G. Biological Control of Plasmopara viticola: Where Are We Now? In Plant and Soil Microbiome, Biocontrol Agents for Improved Agriculture; Kumar, A., Santoyo, G., Singh, J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 67–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffi, T.; Rossi, V. Fungicide Models Are Key Components of Multiple Modelling Approaches for Decision-Making in Crop Protection. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2018, 57, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Llorens, J.; Landers, A.; Llop, J.; Giralt, L. Field Validation of Dosaviña, a Decision Support System to Determine the Optimal Volume Rate for Pesticide Application in Vineyards. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 35, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-B.; Song, H.-J.; Liu, Y.-Q.; Ren, Q.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Li, X.-F.; Pan, H.-X.; Huang, X.-Q. The Potential of Microorganisms for the Control of Grape Downy Mildew—A Review. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Kang, X.; Ma, X.; Ran, L.; Zhen, Z. New Strain of Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens G1 as a Potential Downy Mildew Biocontrol Agent for Grape. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveau, R.; Ilbert, C.; Marie-claire, H.; Palavioux, K.; Anthony, P.; Marzari, T.; Valls-fonayet, J.; Adrian, M.; Fermaud, M. Broad-Spectrum Efficacy and Modes of Action of Two Bacillus Strains against Grapevine Black Rot and Downy Mildew. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaunois, B.; Farace, G.; Jeandet, P.; Clément, C.; Baillieul, F.; Dorey, S.; Cordelier, S. Elicitors as Alternative Strategy to Pesticides in Grapevine? Current Knowledge on Their Mode of Action from Controlled Conditions to Vineyard. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 4837–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, S.W.; Magerøy, M.H.; López Sánchez, A.; Smith, L.M.; Furci, L.; Cotton, T.E.A.; Krokene, P.; Ton, J. Surviving in a Hostile World: Plant Strategies to Resist Pests and Diseases. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019, 57, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallad, G.E.; Goodman, R.M. Systemic Acquired Resistance and Induced Systemic Resistance in Conventional Agriculture. Crop Sci. 2004, 44, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekanović, E.; Potočnik, I.; Stepanović, M.; Milijašević, S. Field Efficacy of Fluopicolide and Fosetyl-Al Fungicide Combination (Profiler ®) for Control of Plasmopara in Grapevine. Pestic. Fitomed. 2008, 23, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, G.; Mancini, V.; Feliziani, E.; Servili, A.; Endeshaw, S.; Neri, D. Impact of Alternative Fungicides on Grape Downy Mildew Control and Vine Growth and Development. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héloir, M.-C.; Li Kim Khiook, I.; Lemaître-Guillier, C.; Clément, G.; Jacquens, L.; Bernaud, E.; Trouvelot, S.; Adrian, M. Assessment of the Impact of PS3-Induced Resistance to Downy Mildew on Grapevine Physiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 133, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, O.; Salotti, I.; Rossi, V. Plant Resistance Inducers Affect Multiple Epidemiological Components of Plasmopara viticola on Grapevine Leaves. Plants 2023, 12, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Poinssot, B.; Daire, X.; Adrian, M.; Bézier, A.; Lambert, B.; Joubert, J.-M.; Pugin, A. Laminarin Elicits Defense Responses in Grapevine and Induces Protection against Botrytis cinerea and Plasmopara viticola. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 2003, 16, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Trotel-Aziz, P.; Conreux, A.; Dhuicq, L.; Jeandet, P.; Couderchet, M. Chitosan Induces Phytoalexin Synthesis, Chitinase and β-1, 3-Glucanase Activities, and Resistance of Grapevine to Fungal Pathogens. In Macromolecules and Secondary Metabolites of Grapevine and Wine; Jeandet, P., Clément, C., Conreux, A., Eds.; Intercept: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Mancini, V.; Carrasco-Quiroz, M.; Servili, A.; Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Foglia, R.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Romanazzi, G. Chitosan and Laminarin as Alternatives to Copper for Plasmopara Viticola Control: Effect on Grape Amino Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7379–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujos, P.; Martin, A.; Farabullini, F.; Pizzi, M. RomeoTM, cerevisane-based biofungicide against the main diseases of grapes and of other crops: General description. In Proceedings of the Atti, Giornate Fitopatologiche, Chianciano Terme, Siena, Italy, 18–21 March 2014; Volume 2, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Perazzolli, M.; Dagostin, S.; Ferrari, A.; Elad, Y.; Pertot, I. Induction of Systemic Resistance against Plasmopara viticola in Grapevine by Trichoderma harzianum T39 and Benzothiadiazole. Biol. Control 2008, 47, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, O.; Fedele, G.; Salotti, I.; Rossi, V. Infection Risk-Based Application of Plant Resistance Inducers for the Control of Downy and Powdery Mildews in Vineyards. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandino, A.C.A.; Vigneron, N.; Alfonso, E.; Burdet, J.P.; Remolif, E.; Cattani, A.M.; Sadki, T.S.; Cluzet, S.; Fonayet, J.V.; Pétriacq, P.; et al. Priming Grapevines with Oregano Essential Oil Vapour Results in a Metabolomic Shift Eliciting Resistance against Downy Mildew. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avesani, S.; Lazazzara, V.; Robatscher, P.; Oberhuber, M.; Perazzolli, M. Current Plant Biology Volatile Linalool Activates Grapevine Resistance against Downy Mildew with Changes in the Leaf Metabolome. Curr. Plant Biol. 2023, 35–36, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebesin, F.; Widhalm, J.R.; Boachon, B.; Lefèvre, F.; Pierman, B.; Lynch, J.H.; Alam, I.; Junqueira, B.; Benke, R.; Ray, S.; et al. Emission of Volatile Organic Compounds from Petunia Flowers Is Facilitated by an ABC Transporter. Science 2017, 356, 1386–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widhalm, J.R.; Jaini, R.; Morgan, J.A.; Dudareva, N. Rethinking How Volatiles Are Released from Plant Cells. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E.; Noel, J.P.; Dudareva, N. Biosynthesis of Plant Volatiles: Nature’s Diversity and Ingenuity. Science 2006, 311, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Orlova, I.; Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; Nagegowda, D.A.; Orlova, I.; Dudareva, N.; Negre, F.; et al. Plant Volatiles: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2006, 25, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N.; Klempien, A.; Muhlemann, K.; Kaplan, I. Tansley Biosynthesis, Function and Metabolic Engineering of Plant Volatile Organic Compounds. New Phythologist 2013, 198, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brilli, F.; Baccelli, I. Exploiting Plant Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in Agriculture to Improve Sustainable Defense Strategies and Productivity of Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, M.; Silva Bueno, J.C. Within-Plant Signaling by Volatiles Leads to Induction and Priming of an Indirect Plant Defense in Nature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5467–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, I.T.; Halitschke, R.; Paschold, A.; von Dahl, C.C.; Preston, C.A. Volatile Signaling in Plant-Plant Interactions: “Talking Trees” in the Genomics Era. Science 2006, 311, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heil, M. Herbivore-Induced Plant Volatiles: Targets, Perception and Unanswered Questions. New Phythologist 2014, 204, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazazzara, V.; Buesc, C.; Parich, A.; Pertot, I.; Schuhmacher, R.; Perazzolli, M. Downy Mildew Symptoms on Grapevines Can Be Reduced by Volatile Organic Compounds of Resistant Genotypes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Rodriguez, E.; Morales-Vargas, A.T.; Molina-Torres, J.; Adame-Alvarez, R.M.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A.; Heil, M.; Norte, K.L. Plant Volatiles Cause Direct, Induced and Associational Resistance in Common Bean to the Fungal Pathogen Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. A Portion of Plant Airborne Communication Is Endorsed by Uptake and Metabolism of Volatile Organic Compounds. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016, 32, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofikoya, A.O. Foliar Behaviour of Biogenic Semi-Volatiles: Potential Applications in Sustainable Pest Management. Arthropod. Plant. Interact. 2019, 13, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Coronel, X.; Molina-torres, J.; Heil, M. Sequestration of Exogenous Volatiles by Plant Cuticular Waxes as a Mechanism of Passive Associational Resistance: A Proof of Concept. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, M.; Mclachlan, M.S. Atmospheric Deposition of Semivolatile Organic Compounds to Two Forest Canopies. Atmos. Environ. 1998, 32, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Khare, P. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances The Role of Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Aromatic Crops in the Management of Bioaerosols at Agricultural Sites: An Overview. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V.; Marcianò, D.; Sargolzaei, M.; Maddalena, G.; Maghradze, D.; Tirelli, A.; Casati, P.; Bianco, P.A.; Failla, O.; Fracassetti, D.; et al. From Plant Resistance Response to the Discovery of Antimicrobial Compounds: The Role of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in Grapevine Downy Mildew Infection. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 160, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štambuk, P.; Šikuten, I.; Preiner, D.; Maleti, E.; Konti, J.K. Croatian Native Grapevine Varieties ’ VOCs Responses upon Plasmopara viticola Inoculation. Plants 2023, 12, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitarrini, G.; Soini, E.; Riccadonna, S.; Franceschi, P.; Zulini, L.; Masuero, D.; Vecchione, A.; Stefanini, M.; Di Gaspero, G.; Mattivi, F.; et al. Identification of Biomarkers for Defense Response to Plasmopara viticola in a Resistant Grape Variety. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitarrini, G.; Riccadonna, S.; Zulini, L.; Vecchione, A.; Stefanini, M.; Larger, S.; Pindo, M.; Cestaro, A.; Franceschi, P.; Magris, G.; et al. Two—Omics Data Revealed Commonalities and Differences between Rpv12—And Rpv3—Mediated Resistance in Grapevine. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algarra Alarcon, A.; Lazazzara, V.; Cappellin, L.; Bianchedi, P.L.; Schuhmacher, R.; Wohlfahrt, G. Emission of Volatile Sesquiterpenes and Monoterpenes in Grapevine Genotypes Following Plasmopara viticola Inoculation in Vitro. J. Mass Spectrom. 2015, 50, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greff, B.; Sáhó, A.; Lakatos, E.; Varga, L. Biocontrol Activity of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants and Their Bioactive Components against Soil-Borne Pathogens. Plants 2023, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanen, S.J.; Blande, J.D.; Klemola, T.; Pulkkinen, J.; Heijari, J.; Holopainen, J.K. Birch (Betula Spp.) Leaves Adsorb and Re-Release Volatiles Specific to Neighbouring Plants—A Mechanism for Associational Herbivore Resistance? New Phytol. 2010, 186, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, I.; Hörtnagl, L.; Ruuskanen, T.M.; Schnitzhofer, R.; Müller, M.; Graus, M.; Karl, T.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Hansel, A. Deposition Fluxes of Terpenes over Grassland. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. JGR 2011, 116, D14305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagmir, A.N.M. Pharmacognostical Botany: Classification of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs), Botanical Taxonomy, Morphology, and Anatomy of Drug Plants. In Therapeutic Use of Medicinal Plants and Their Extracts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienth, M.; Crovadore, J.; Ghaffari, S.; Lefort, F. Oregano Essential Oil Vapour Prevents Plasmopara viticola Infection in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) and Primes Plant Immunity Mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.G.; Bortolotto, O.C.; Ventura, M.U. Aromatic Plants Affect the Selection of Host Tomato Plants by Bemisia tabaci Biotype B. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2017, 162, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togni, P.H.B.; Venzon, M.; Muniz, C.A.; Martins, E.F.; Pallini, A.; Sujii, E.R. Mechanisms Underlying the Innate Attraction of an Aphidophagous Coccinellid to Coriander Plants: Implications for Conservation Biological Control. Biol. Control 2016, 92, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczech, M.; Kowalska, B.; Wurm, F.R.; Ptaszek, M.; Løvschall, K.B.; Velasquez, S.T.R. The Effects of Tomato Intercropping with Medicinal Aromatic Plants Combined with Trichoderma Applications in Organic Cultivation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweellum, T.A.; Naguib, D.M. Tomato Potato Onion Intercropping Induces Tomato Resistance against Soil Borne Pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum through Improvement Soil Enzymatic Status, and the Metabolic Status of Tomato Root and Shoot. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2023, 130, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Du, F.; Yang, R.; Yao, H.; Yang, M.; Mei, X.; Ye, C.; Li, S. Volatile Organic Compounds of Hoary Stock Are Responsible for Suppressing Downy Mildew of Grape in an Intercropping System. Phytopathol. Res. 2025, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, N.; Grimplet, J.; Remolif, E.; Rienth, M. Unravelling Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Resistance Priming against Downy Mildew (Plasmopara viticola) in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagostin, S.; Formolo, T.; Giovannini, O.; Pertot, I.; Schmitt, A. Salvia officinalis Extract Can Protect Grapevine against Plasmopara viticola. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennelly, M.M.; Gadoury, D.M.; Wilcox, W.F.; Magarey, P.A.; Seem, R.C. Primary Infection, Lesion Productivity, and Survival of Sporangia in the Grapevine Downy Mildew Pathogen Plasmopara viticola. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steimetz, E.; Trouvelot, S.; Gindro, K.; Bordier, A.; Poinssot, B.; Adrian, M.; Daire, X. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology In Fl Uence of Leaf Age on Induced Resistance in Grapevine against Plasmopara viticola. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 79, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Vaccari, F.; Ardenti, F.; Fiorini, A.; Tabaglio, V.; Puglisi, E.; Trevisan, M.; Lucini, L. The Dosage- and Size-Dependent Effects of Micro- and Nanoplastics in Lettuce Roots and Leaves at the Growth, Photosynthetic, and Metabolomics Levels. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 208, 108531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaicha, O.; Tiziani, R.; Maver, M.; Lucini, L.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Zhang, L.; Trevisan, M.; Cesco, S.; Borruso, L.; Mimmo, T. Plant Species-Specific Impact of Polyethylene Microspheres on Seedling Growth and the Metabolome. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 840, 156678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. Guidelines for the Efficacy Evaluation of Fungicides: Plasmopara viticola. EPPO Bull. 2001, 31, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-Independent MS/MS Deconvolution for Comprehensive Metabolome Analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, S.; Seo, M.; Shin, K.B.; Kim, K.H.; Park, G.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Yoo, J.S.; No, K.T. BMDMS-NP: A Comprehensive ESI-MS/MS Spectral Library of Natural Compounds. Phytochemistry 2020, 177, 112427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, R.M.; Steinbeck, C.; Viant, M.R.; Goodacre, R.; Dunn, W.B. The Role of Reporting Standards for Metabolite Annotation and Identification in Metabolomic Studies. Gigascience 2013, 2, 2013–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, F.; Iserloh, T.; Treseler, C.-H.; Hüppi, R.; Ogan, S.; Seeger, M.; Thiele-Bruhn, S. Crop Diversification in Viticulture with Aromatic Plants: Effects of Intercropping on Grapevine Productivity in a Steep-Slope Vineyard in the Mosel Area, Germany. Agriculture 2021, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-segantini, D.; Lombini, A.; Rodríguez-Declet, A.; De Giorgio, R.; D’onofrio, C.; Rombolà, A.D. Effects of Intercropping Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs) on Grapevine Cv. Sangiovese Berry Volatile Compounds. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, F.; Liu, B.; Tebbe, C.C. Diversifying Grapevines with Aromatic Plants Changes the Soil Habitat, Microbial Community Composition and Functions Toward More Efficient Substrate Use and Nutrient Allocation. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2025, 4, e70071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyard, A.; Ciuraru, R.; Lafouge, F.; Decuq, C.; Fortineau, A.; Loubet, B.; Staudt, M.; Rees, F. Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds from Aboveground and Belowground Parts of Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) and Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Matas, E.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Bonfill, M.; Lucini, L.; Hidalgo-Martinez, D.; Palazon, J. Impact of Elicitation on Plant Antioxidants Production in Taxus Cell Cultures. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Estrada, K.; Vidal-Limon, H.; Hidalgo, D.; Moyano, E.; Golenioswki, M.; Cusidó, R.M.; Palazon, J. Elicitation, an Effective Strategy for the Biotechnological Production of Bioactive High-Added Value Compounds in Plant Cell Factories. Molecules 2016, 21, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Davis, L.C.; Verpoorte, R. Elicitor Signal Transduction Leading to Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2005, 23, 283–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E.; Raguso, R.A. Why Do Plants Produce so Many Terpenoid Compounds? New Phythologist 2018, 220, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljbory, Z.; Chen, M.-S. Indirect Plant Defense against Insect Herbivores: A Review. Insect Sci. 2018, 25, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffolatti, S.L.; Maddalena, G.; Passera, A.; Casati, P.; Bianco, P.A.; Quaglino, F. Chapetr 16—Role of Terpenes in Plant Defense to Biotic Stress. In Biocontrol Agents and Secondary Metabolites; Jogaiah, S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensec, F.; Szakiel, A.; Pa, C.; Grabarczyk, M.; Bertsch, C.; Fischer, M.J.C.; Chong, J. Characterization of Triterpenoid Profiles and Triterpene Synthase Expression in the Leaves of Eight Vitis vinifera Cultivars Grown in the Upper Rhine Valley. J. Plant Res. 2016, 129, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakiel, A.; Pączkowski, C.; Henry, M. Influence of Environmental Abiotic Factors on the Content of Saponins in Plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2011, 10, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdziej, A. Effect of Selected Elicitors on Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) Primary and Secondary Metabolism: Focus on Stilbenes and Triterpenoids. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, the University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lucini, L.; Baccolo, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Bavaresco, L.; Trevisan, M. Chitosan Treatment Elicited Defence Mechanisms, Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and Stilbene Accumulation in Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) Bunches. Phytochemistry 2018, 156, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batovska, D.I.; Todorova, I.T.; Parushev, S.P.; Nedelcheva, D.V.; Bankova, V.S.; Popov, S.S.; Ivanova, I.I.; Batovski, S.A. Biomarkers for the Prediction of the Resistance and Susceptibility of Grapevine Leaves to Downy Mildew. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toffolatti, S.L.; De Lorenzis, G.; Costa, A.; Maddalena, G.; Passera, A.; Bonza, M.C.; Pindo, M.; Stefani, E.; Cestaro, A.; Casati, P.; et al. Unique Resistance Traits against Downy Mildew from the Center of Origin of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, P.; Vlot, A.C. Volatile Terpenes—Mediators of Plant-to-Plant Communication. Plant J. 2021, 108, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre-Guillier, C.; Chartier, A.; Dufresne, C.; Douillet, A.; Cluzet, S.; Valls, J.; Aveline, N.; Daire, X.; Adrian, M. Elicitor-Induced VOC Emission by Grapevine Leaves: Characterisation in the Vineyard. Molecules 2022, 27, 6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J. Genome-Wide Identification of CYP72A Gene Family and Expression Patterns Related to Jasmonic Acid Treatment and Steroidal Saponin Accumulation in Dioscorea zingiberensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, S.; Shriram, V.; Khare, T.; Kumar, V. Biotic Elicitors Enhance Diosgenin Production in Helicteres isora L. Suspension Cultures via up-Regulation of CAS and HMGR Genes. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Li, J. Advances in the Biosynthesis and Molecular Evolution of Steroidal Saponins in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujváry, I. Chapter 3—Pest Control Agents from Natural Products. In Hayes’ Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Krieger, R., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 119–229. ISBN 978-01-2374367-1. [Google Scholar]

- Viterbo, A.; Staples, R.C.; Yagen, B.; Mayer, A.M. Selective Mode of Action of Cucurbitacin in the Inhibition of Laccase Formation In Botrytis cinerea. Phytochemistry 1994, 35, 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureano, G.; Cavaco, A.R.; Matos, A.R.; Figueiredo, A. Fatty Acid Desaturases: Uncovering Their Involvement in Grapevine Defence against Downy Mildew. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidot, E.; Zancani, M.; Petrussa, E.; Peresson, C.; Bertolini, A.; Patui, S.; Macrì, F.; Vianello, A. Transport and Accumulation of Flavonoids in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomali, A.; Das, S.; Arif, N.; Sarraf, M.; Zahra, N.; Yadav, V.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Chauhan, D.K.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Diverse Physiological Roles of Flavonoids in Plant Environmental Stress Responses and Tolerance. Plants 2022, 11, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Lam, P.Y.; Andreote, F.D.; Dai, L.; Wei, Z. Multifaceted Roles of Flavonoids Mediating Plant—Microbe Interactions. Microbiome 2022, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, N.-Q.; Lin, H.-X. Contribution of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism to Plant Development and Plant—Environment Interactions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 180–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Roy, J.; Huss, B.; Creach, A.; Hawkins, S.; Neutelings, G. Glycosylation Is a Major Regulator of Phenylpropanoid Availability and Biological Activity in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, K.; Shimizu, B.; Mizutani, M.; Watanabe, K.; Sakata, K. Accumulation of Coumarins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2006, 67, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čulina, P.; Cvitković, D.; Pfeifer, D.; Zorić, Z.; Repajić, M.; Elez Garofulić, I.; Balbino, S.; Pedisić, S. Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Selected Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Diversity upon Plant Species and Extraction Technique. Processes 2021, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.; Maltese, F.; Figueiredo, A.; Rex, M.; Fortes, A.M.; Zyprian, E.; Pais, M.S.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Alterations in Grapevine Leaf Metabolism upon Inoculation with Plasmopara viticola in Different Time-Points. Plant Sci. 2012, 191–192, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Hoyos, L.; Stam, R. Metabolomics in Plant Pathogen Defense: From Single Molecules to Large-Scale Analysis. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 760–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, H.K.; Banerjee, D. Natural Products as Fungicide and Their Role in Crop Protection. Nat. Bioact. Prod. Sustain. Agric. 2020, 12, 131–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Brunetti, C.; Fini, A.; Gori, A.; Guidi, L.; Landi, M.; Sebastiani, F.; Tattini, M. Are Flavonoids Effective Antioxidants in Plants? Twenty Years of Our Investigation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Azzarello, E.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Flavonoids as Antioxidants in Plants: Location and Functional Significance. Plant Sci. 2012, 196, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]