Abstract

Fruit growing is a traditional component of Bulgarian agricultural production. According to the latest statistical data, the share of areas planted with cherries is 10.5% of the total orchard area, and with apples, 7.2%, totaling 67,800 ha. This article presents the results of ground and remote (satellite) measurements and observations of cherry and apple orchards, along with the methods for their processing and interpretation, to define the current state and forecast their expected development. This research aims to combine the capabilities of the two approaches by improving and expanding observation and forecasting activities. Ground-based measurements and observations consider the dates of a permanent transition in air temperature above 5 °C and several cardinal phenological stages, based on the idea that a certain temperature sum (CU, GDH, GDD) must accumulate to move from one phenological stage to another. The obtained data were statistically analyzed, and by means of classification with the Random Forest algorithm, the dates for the occurrence of the stages of bud break, flowering, and fruit ripening in the development of cherry and apple orchards were predicted with an accuracy of −6 to +2 days. Satellite studies include creating a database of Sentinel-2 digital images across different spectral bands for the studied orchards, investigating various post-processing approaches, and deriving indicators of developmental phenostages. Ground data from the 2021–2023 experiment in Kyustendil and Plovdiv were used to determine the phases of fruit bursting, flowering, and ripening through satellite images. An assessment of the two approaches to predicting the development of the accuracy of the models was carried out by comparing their predictions for bud swelling and bursting (BBCH 57), flowering (BBCH 65), and fruit ripening (BBCH 87/89) of the observed phenological events in the two selected orchard types, representatives of stone and pome fruit species.

1. Introduction

Fruit growing is a vital component of Bulgaria’s agricultural production. Unfortunately, the production area has decreased significantly over time. Orchards and vineyards constitute an entire agricultural sector. According to the CAP and the prospects for the sector’s development in the context of climate change, which requires reducing the carbon footprint and adapting to and mitigating its consequences, it is necessary to change the approaches to monitoring and forecasting the development of these orchards.

In this case, we want to share the results of our research on several varieties of apples and cherries grown in the Plovdiv and Kyustendil regions.

Fruit species originate from temperate geographical regions, whose climate is characterized by four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The cold winter and the warm spring–summer period determine the periods of rest and development of trees [1].

In temperate zones, dormancy in fruit trees is an annual stage that enables them to withstand adverse winter conditions [2]. To overcome this stage, trees must satisfy their cooling requirements [3,4]. Once the necessary cooling units are accumulated, buds can develop and resume tree growth. Since this occurs at the end of winter, external adverse environmental factors inhibit growth, and the trees enter their ecodormancy period [5]. The phenological calendar represents the annual progression of a plant’s biological development, presented in a sequence of interconnected events. In fruit species, it includes the stages from the beginning of dormancy. A strong interaction between genotype and environmental conditions controls these stages. The phenological development calendar is essential for crop cultivation, as it allows for specific agrotechnical operations to be carried out at precisely defined times [6]. Climatic conditions cannot be controlled, and under their influence, significant variations in the occurrence of phenostages are observed from year to year [7]. Predicting the timing of phenological stages is crucial for informed crop management decisions, including pesticide applications, irrigation planning, fertilization, pruning, and thinning [8].

Fruit buds set in fruit species begin in the summer of the previous year, which usually leads to flowering with an extension of the apical meristem. They then continue to develop for eight months with interruptions during the tree’s dormancy [9]. The flowering period of fruit species is one of the most important agrotechnical indicators. It is crucial in the cultivation of self-sterile varieties that require cross-pollination and determine the crop’s vulnerability to late frosts [10].

The flowering date is a crucial characteristic of fruit species, particularly in relation to their adaptation to global climate change. Documented changes in phenology serve as reliable indicators of the impact of climate change and its variability on natural and managed ecosystems. From this perspective, models are necessary to predict phenological transition dates for various applications, including a deeper understanding of physiological mechanisms and the prediction of climate change impacts [11].

Although apples and cherries are highly adaptable to diverse soil and climatic conditions, recent climate changes have brought to the fore the tolerance of varieties to abiotic and biotic stressors. A limiting factor for the cultivation of fruit species, including apples and cherries, is temperature conditions. The specialized literature indicates that the critical temperatures during deep dormancy of apples range from −20 to −27 °C, and for cherries, up to −25 °C; however, these values can be reached in individual years, in which case opportunities are created for assessing the response of individual apple varieties [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. When fruit trees emerge from deep dormancy and enter forced dormancy, the sensitivity of fruit trees increases significantly.

In temperate regions, damage from late-spring frosts during flowering is greater than that from low winter temperatures. From deep dormancy to fruit set, fruit buds go through several stages of development, each associated with progressively greater sensitivity to low temperatures. It has been proven that the degree of damage from late spring frosts depends to the greatest extent on the developmental stages of reproductive organs, and tissue reserves with reserve nutrients, and the response of apple and cherry varieties to late spring frosts and extreme winter frosts is the subject of many studies, as they cause significant damage to fruit crops [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Climate change is a significant factor in determining the need for predictive models. An important aspect of these processes is not only the average values of precipitation or temperature, but also the occurrence of extreme precipitation events, such as those that are followed by drought in an atypical period. Precipitation is a driver of many crop diseases [26,27].

Different climatic factors influence various phenological parameters of vegetation within their optimal duration [28,29,30,31], revealing distinct trends in the relationships between the start of season (SoS) and the end of season (EoS).

Phenological models are based on the relationship between temperature conditions and the phenological development of fruit species. Depending on the approach to characterizing the conditions during the dormancy period, the models are of two types: single-phase and two-phase. Single-phase models estimate the heat required to reach a specific stage of bud development, such as bud swelling or flowering [32,33]. Thermal weather models are commonly used to predict the rate of development of temperature-dependent processes in plants, such as seed germination [34] and leaf development [35,36]. Thermal time models assume that the rate of development increases linearly with temperature [32,33] and implicitly assume that chilling requirements are always satisfied, as they describe accumulation only during the forced dormancy period, omitting the deep dormancy phase. Although they are often used to predict the flowering period in annual plants [37], single-phase models alone are not typically used in fruit crops, as bud break in these species depends on CU accumulation [38,39,40]. Two-phase models can be classified according to the interaction between the chilling and heat requirements submodels: parallel [41], sequential [42,43], and overlapping models [1].

In recent years, machine learning methods have been increasingly used to improve model accuracy, as shown for 10 plant species by Czernecki et al. [44]. Satellite and meteorological products were used as predictors to build models for predicting the selected phenological phases. Regarding meteorological variables, the authors found better agreement when using the Random Forest learning and correlation procedure.

Using data on flowering, fruiting, and maturity dates recorded at 25 locations across 11 European countries, a team of researchers revealed a clear trend towards earlier flowering and fruiting times, associated with increasing temperatures and changing climatic conditions. The study provided a valuable dataset for future research on strategies to adapt fruit trees to climate change. It also emphasizes the importance of long-term phenological data collection for predicting future trends and making informed decisions in agriculture [32].

The impact of climate change on phenological stages can also be observed using satellite imagery, which, in combination with various models, is used to analyze and track past events. The process of recording phenological stage transitions at the ground level is fundamentally different from that at a satellite-based level [36]. The first level uses information obtained from experts who regularly observe individual fields or test sites. Agrometeorological forecasting models are based on empirical relationships well established in practice and derived from multiple regression analysis. In this case, their success depends on the correct selection of independent variables.

Remote sensing is applied to land surface phenology (LSP), which examines how vegetation changes over time and space when observed from satellites. Here, information is derived from models that utilize data from satellite sensors with varying spectral, spatial, and temporal resolutions. The optimal method for assessing vegetation health from satellite images remains a subject of ongoing debate [37]. Many studies rely on the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) [38,39], a widely used indicator for quantifying plant growth. Over 75% of phenology studies use NDVI [39]. Satellite data are often confounded by noise and incompleteness, which makes direct analysis challenging. Cloud cover and other atmospheric factors can cause gaps in the data. To address these issues, techniques such as gap-filling and smoothing are used to create a clean, continuous record of vegetation changes over time. Traditional methods for smoothing and reconstructing time series can be categorized into three main approaches: empirical, curve-fitting, and data transformation. In recent years, machine learning techniques have emerged as promising alternatives for phenological monitoring [40]. To identify the number of growing seasons, software tools typically analyze the high and low points of the growth curve [41]. After identifying the seasons, LSP indicators such as the start (SoS) and end (EoS) of the growing season are calculated from the smoothed and reconstructed time series. The time series of the vegetation index (VI) obtained from these data is used in phenological models for a specific crop or plantation to prepare global LSP products and map crop phenology in near real time [42]. In our study, we focused on phenological models based on phenological parameters (PM) associated with crop growth stages during the growing season, derived from satellite-based time series of vegetation indices. Methods for extracting different phenological indicators have been classified by [39] into two main categories: threshold-based age methods and methods for detecting changes in vegetation indices (VIs). Both categories have been utilized in the definition of phenological monitoring of orchards [43,45,46]. Most researchers have focused on using time-series vegetation indices to determine the phenological stages of greenness, maturity, senescence, and dormancy [47,48]. The sanitary condition of an orchard during the critical phenological stages of inflorescence emergence and flowering significantly impacts development and yield formation. Numerous studies have investigated the use of remote sensing data to distinguish the colors of different plant parts [49]. In recent years, monitoring orchard flowering using high-resolution NDVI images from the Sentinel-2 satellite has attracted growing interest among researchers [50]. To quantify the flowering status of almond orchards, a flowering index (EBI) [51] based on multispectral remotely sensed data has been developed. Good results have been obtained from experimental tests of the EBI conducted in the Central Valley of California, USA, using data from unmanned aerial vehicles and time-series satellite images from PlanetScope, Sentinel-2, and Landsat. We found no publications examining the use of phenological models derived from remotely sensed data to determine key phenological growth stages (PGSs), such as inflorescence emergence, flowering, and fruit/seed maturity, in apple and cherry orchards. Apples follow a leaf-after-flowering pattern, where leaves emerge first, followed by the appearance of inflorescences and white flowers. In contrast, cherry trees bloom pink before the leaves appear. Therefore, given these specificities and the different phenological modeling approaches described above, this study aims to evaluate the performance of phenological models for apples and cherries using agrometeorological and Sentinel-2 satellite data. Their performance is intended to be determined by a comparative assessment of the accuracy of models for inflorescence emergence, flowering, and maturity dates.

The empirical models, which are based entirely on meteorological and phenological data, included daily air temperature values during the period of 2021–2023 and derived characteristics such as dates of a sustained transition of the average daily temperature through 5 °C in spring and autumn, and sums of active temperatures for different periods—from the transition through 5 °C to bud bursting, from bud bursting to flowering, and from flowering to fruit ripening. Data on the values of cold units (CUs) and the sum of hourly temperatures above the biological minimum during the dormant period were also used. Data on the mass occurrence of phenological stages by year were also used.

This study aims to develop an algorithm to predict the occurrence of specific phenological stages in cherry and apple plantations, using both ground-based and satellite observations and measurements. This aim can be solved by conducting the following tasks: to test the possibility of applying satellite images to monitor and identify the development and condition of orchards; to find sufficiently informative indicators that would correspond unambiguously and adequately to the phenological development of fruit trees; to propose an appropriate protocol for conducting satellite observations of orchards; and to create and test an empirical model for predicting the dates of occurrence of phenological stages depending on the date of a sustained temperature transition above 5 °C in spring for each specific type of orchard.

In the literature we have studied, data from such investigations are rarely found, and when they are, they are mainly for cherries [27,30,32,33,47,51]. Even fewer are combined ground-based and remote observations and measurements on cherry and apple plantations. Given this fact, this development is relevant and forms part of a system for monitoring and forecasting the growth and development of orchards in Bulgaria. It is to be further developed through the application of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for forecasting and early warning, as well as for diagnosing the physiological state of fruit trees in response to extreme weather events, especially during the flowering and fruit formation periods [19,20,21,22]. Their frequent occurrence in a given area and the degree of damage to fruit crops are limiting factors in fruit crop cultivation.

2. Materials and Methods

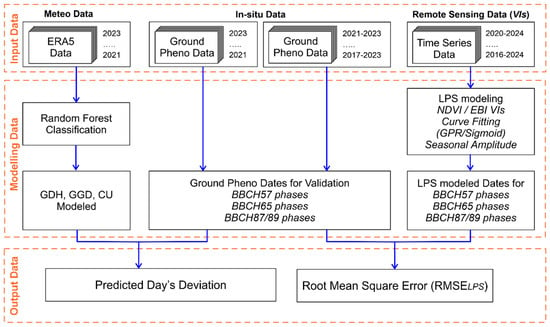

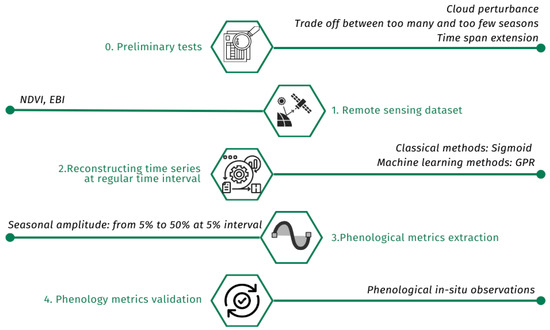

Figure 1 presents the methodology followed in this study.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of methodology followed in this study.

2.1. Study Area

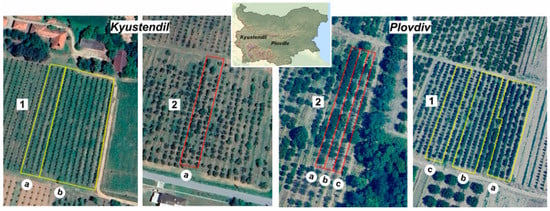

This study was conducted in the experimental orchards of the Institute of Agriculture in Kyustendil and the Institute of Fruit Growing in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, from 2021 to 2023 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Experimental fields and experimental plots with apples: (1) Florina (a), Mutsu (b); and cherries (2) Bing (a) at the Institute of Fruit Growing—Kyustendil (left) and plots with apples (1)“Florina” (a), “Chadel” (b), “Cooper 4” (c); and sweet cherries (2)“Rozalina” (a), “Rosita” (b), “Kosara” (c) at the Institute of Fruit Growing—Plovdiv (right); source of map data: Google Earth, image© 2024 Airbus.

Kyustendil Plain, situated at 527 m above sea level in western Bulgaria, is transitional continental, characterized by relatively mild winters and warm, dry summers. The region’s climatic conditions are primarily determined by its location and the good protection it receives from mountain ranges, which diversify the relief and contribute to some diversity in the individual micro-districts. Winter is generally mild, summer is relatively warm for the region’s altitude, and precipitation levels are slightly lower than the national average. The average annual temperature is 12.5 °C. The highest average monthly temperature is in July (21.8 °C), and the lowest is in January (−0.8 °C). Summer is warm and long, winter is short and mild to slightly cold (only 30 days with air temperature below or equal to 0 °C), spring comes early and continues steadily after the first days of March, and autumn is long, warm, and sunny, which remains stable until the end of November. Precipitation is moderate, an average of 624 mm per year, and snow cover lasts no longer than 30–40 days in winter.

In Kyustendil, the experimental apple orchard consists of two varieties: “Florina” and “Mutsu”. In the cherry orchard, the variety is “Bing”. The area occupied by apple trees is located at coordinates: 42°18′50″ N; 22°43′40″ E (42.3133° N; 22.7283° E), which were grafted onto rootstock MM 106 and planted in the spring of 2008 at a distance of 4.5 × 3.0 m. The area occupied by cherry trees is located at coordinates 42°18′30′’ N; 22°44′00′’ E (42.350° N; 22.733° E) and was planted in 1991 in a 6.0 × 5.0 m scheme, grafted onto Prunus mahaleb L. rootstock. Ten trees represent each variety, and each tree is counted as a separate specimen. The trees are in full fruiting and have been grown using standard technology. The soil is a leached cinnamon forest soil with a slightly sandy–loamy structure and a neutral reaction. The soil surface in the inter-rows is maintained by regular mowing with a mulcher, and in the inter-row strips, it is treated with a total herbicide. The horizontal projection of the crown, which we measured in 2023, is 5.72 m2 (Mutsu) and 7.01 m2 (Florina) for the apple trees, and 16.6 m2 for the cherry trees.

Plovdiv is situated at an altitude of 160 m above sea level, spanning both banks of the Maritsa River. The climate here is also transitional–continental. Winter in the Plovdiv region is relatively mild, with an average monthly temperature of −0.4 °C in January, and an average winter temperature (December, January, and February) of +4.0 °C. Spring usually comes early, in the first days of March. The average last frost date is around April 10. Summer is hot. The average monthly temperature in the warmest month, July, is 23.2 °C.

For the experiment at the Institute of Fruit Growing—Plovdiv, two orchards planted in 2011 were also used. The apple trees were spaced 4 × 3 m apart, with coordinates 42°06′20.6″ N 24°43′29.8″ E (42.105729, 24.724948). The varieties “Florina”, “Chadel”, and “Cooper 4” were used for the observations. In the experimental cherry orchard, at a distance of 6 × 4 m and coordinates 42°06′19.6” N 24°43′21.5” E (42.105433, 24.722627), the varieties “Kosara”, “Rosita”, and “Rozalina” were planted. The horizontal projection of the crown, which we measured in 2023, of apple trees was 11.38 m2 (Chadel), 20.78 m2 (Florina), and 17.54 m2 (Cooper 4), and that of cherry trees was 19.84 m2 (Rosita), 20.47 m2 (Kosara), and 20.84 m2 (Rozalina). The soil of the experimental field in Plovdiv is typical meadow cinnamon. It is characterized by a slightly sandy–clayey mechanical composition and a strong humus horizon [51]. The soil reaction of the medium (pH) is as follows: from 0 to 30 cm = 6.8; from 31 to 60 cm = 6.8, and from 61 to 90 cm = 7.4 [52].

2.2. Ground Data

Meteorological and phenological data

To predict the dates of the onset of the phases BBCH57, BBCH65, and BBCH87 for cherry trees and BBCH89 for apple using meteorological data and agrometeorological indices, we chose a Random Forest algorithm. Temperature conditions during dormancy and the early stages of fruit crop development determine the rates of phenological development in subsequent periods. Therefore, we chose to use the following three agrometeorological indices: chilly units (CUs), sum of hourly values of the temperatures above biological minimum during dormancy, GDH, and sum of effective temperatures, GDD. To estimate these indices, hourly air temperature values were used using the methodology described in [53,54]. The hourly values were calculated with data downloaded from Climate Data Store ERA5-Land Hourly Data (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets, accessed on 15 November 2024). The ERA 5-Land Dataset is a product resulting from a thorough reanalysis of the dataset, providing a consistent view of the evolution of land variables over several decades at an enhanced resolution compared to ERA5. ERA5-Land has been produced by replaying the land component of the ECMWF ERA5 climate reanalysis. Reanalysis combines model data with observations from around the world into a globally complete and consistent dataset, utilizing the laws of physics.

Phenological observations were conducted in the Institute of Agricultural Sciences’ agrometeorological network and the experimental fields of Kyustendil and Plovdiv to determine the dates of the main phenological stages of the studied fruit species and varieties.

For this study, we had a set of phenological and meteorological data for the period of 2021–2023. Meteorological and agrometeorological data are listed in Table 1. We must make the following clarification: The object of this study is the three phenophases already mentioned, but because biological development is a continuous process and the timing and intensity of processes during a given phase are set in the previous one, we are also considering the phase of bud swelling.

Table 1.

Meteorological data and agrometeorological indices, and the relationship with the frequency of occurrence of some phenological stages.

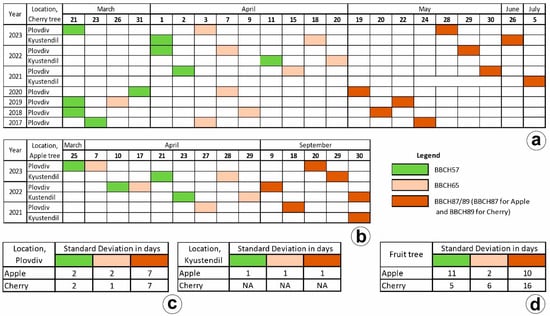

For the entire period of the experiment (2021–2023), phenological observations were conducted using the methodology described in the Federal Biological Research Center for Agriculture and Forestry’s “Growth Stages of Monocotyledonous and Dicotyledonous Plants” (Meier et al. 2001) [55]. Several main stages were defined for apple: BBCH57—rosebud stage: flower petals elongate; sepals slightly open; petals only visible; BBCH65—full bloom: at least 50% of flowers open, first petals falling; and BBCH87—fruit ripening for picking. For cherry, these stages are BBCH57—sepals open: petal tips visible; single flowers with white or pink petals (still closed); BBCH65—full flowering: at least 50% of flowers are open, first petals falling, and for apple trees; and BBCH89—fruit ripening for picking. Phenological information for fruit trees in the study area is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Description of fruit tree phenology for the BBCH57, BBCH65, and BBCH89 stages in the study area for (a) cherry, (b) apple, (c) standard deviation in days for cherry and apple in Plovdiv and Kyustendil, (d) standard deviation in days for all apple and BBCH87 all cherry trees.

2.3. Remote Sensing Dataset

Orchard experiments have a wide variety of situations associated with many multispectral images and VI. They are influenced by both orchard phenological development and age differences, as well as row spacing, grass, and temporal characteristics of tree crown development [43,44]. To minimize their effects on phenological indicators while fulfilling the objective of our study, we selected plots occupied by apple and cherry trees in two experimental fields.

Sentinel-2 imagery was used as the primary source of remote sensing data, with time series extracted using the Sentinel-Hub Request Builder (https://apps.sentinel-hub.com/requests-builder, accessed on 7 January 2026) from Sentinel-Hub (https://www.sentinel-hub.com/, accessed on 7 January 2026). Preliminary tests were conducted to optimize data quality by correcting for cloud cover and determining the optimal data collection period. A cloud-free time series is preferred to minimize errors; however, including more data points in the series improves phenological analysis. After evaluating images with cloud cover ranging from 0% to 5%, we selected images with cloud cover of up to 5%. For effective phenological analysis, the time series must span the modeled seasons. Since we focused on the phenological stages of apples and cherries within the same calendar year, we considered remotely sensed data from January 1 of the year prior to the in situ phenological data until 31 July 2024. Two vegetation indices (VIs) were downloaded for each location and fruit tree type using 10 m × 10 m raster data with a maximum of 5% cloud cover. The data were checked for anomalies, and the study used data summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of the time series downloaded from Sentinel-Hub.

As we aim to identify bud swelling, full bloom, and ripening phenological stages in apple and cherry orchards, we selected two vegetation indices for our study: NDVI and EBI. NDVI captures the seasonal dynamics of canopy greenness and senescence, while EBI has been reported as an effective index for flowering detection. The two VI that were downloaded were NDVI (1) and modified EBI (2) are as follows [56]:

where NIR, R, G, and B are reflectance characteristics in near-infrared, red, green, and blue bands, and ε is an empirical constant. The ε value was set to 1 for the reflectance data, which ranged from 0 to 1, and to 256 for the raw data, which ranged from 0 to 255.

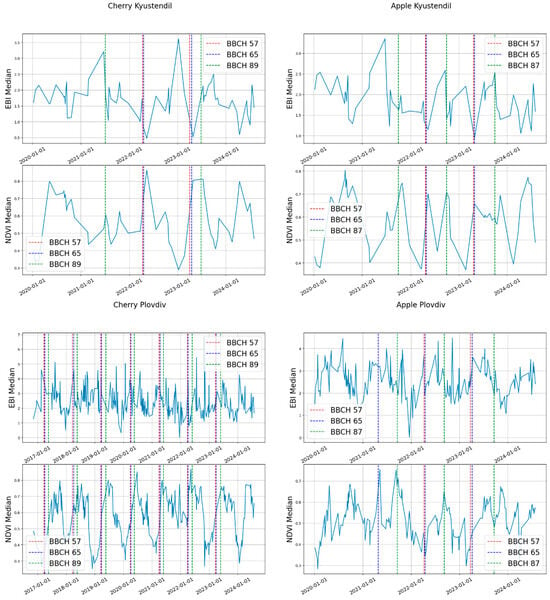

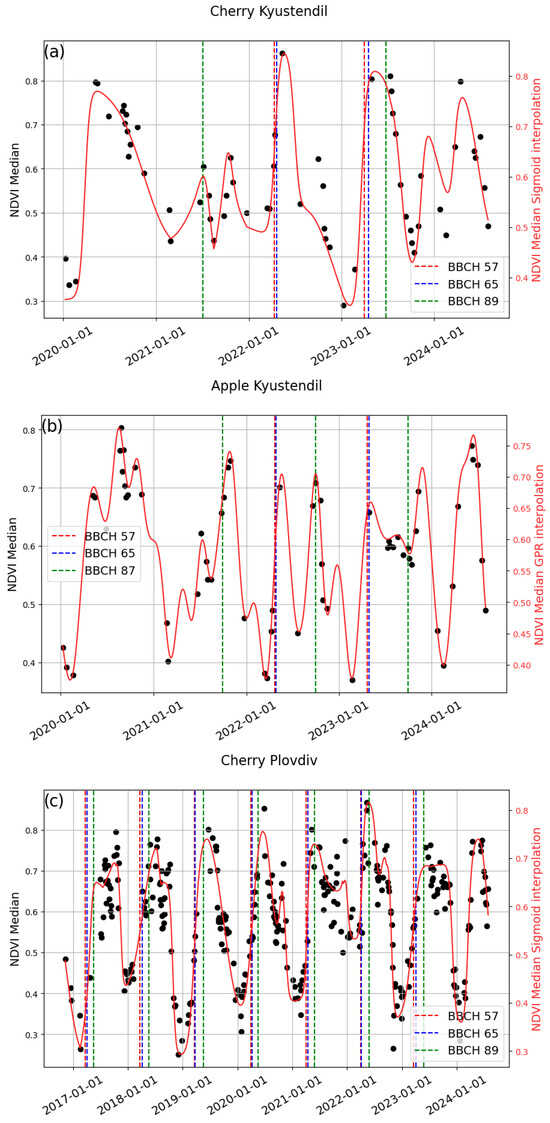

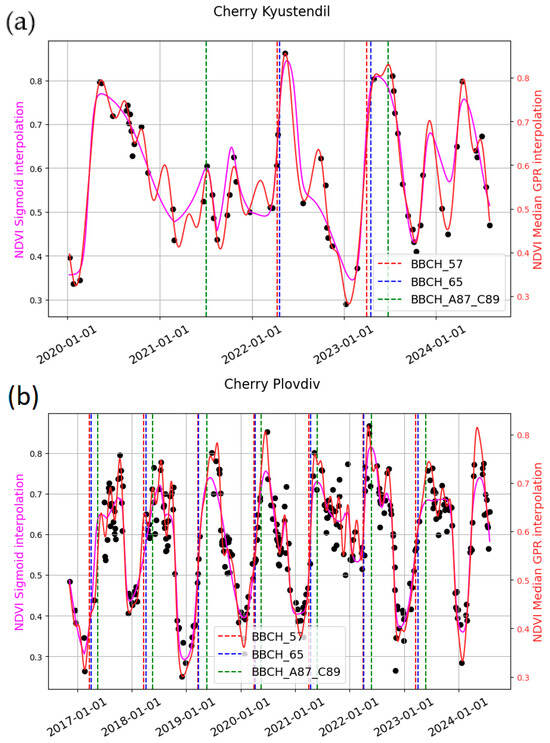

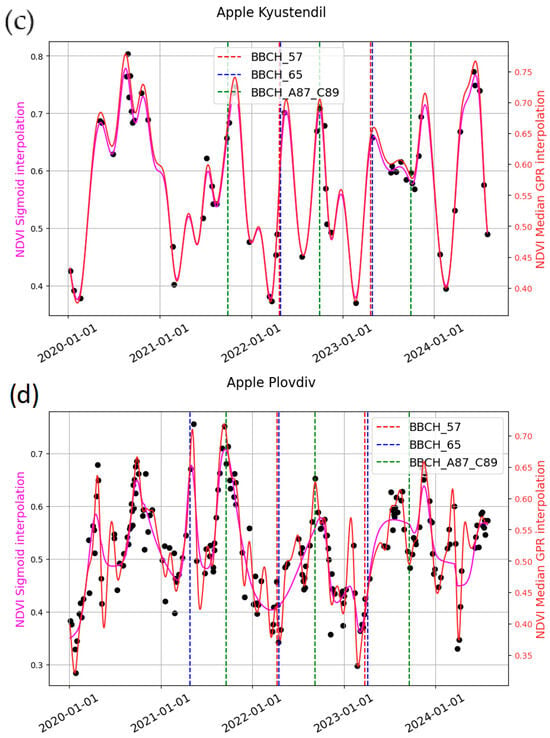

Once the images were downloaded, we calculated the median pixel value for each location and fruit tree type (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Plot of average NDVI and EBI values for each location and fruit tree type, and the dates of occurrence of the BBCH 57, BBCH 65, and BCH 87 for apple, and BBCH 89 for cherry.

2.4. Empirical Modeling

For this study, we tested the empirical models we developed to determine the occurrence of bud burst, flowering, and fruit ripening as a function of temperatures and agrometeorological indices.

A Random Forest algorithm is an extremely popular supervised machine learning algorithm used for Classification and Regression problems, based on the concept of ensemble learning. Ensemble learning is a process of combining multiple classifiers to solve complex problems and improve model performance. This method reduces variances by generating multiple datasets through sampling with replacement. It also helps to identify the important attributes.

As a result of the numerical processing conducted and the application of the Random Forest procedure, the variables that have the greatest influence on the dates of the onset of the phenological stages BBCH 57, BBCH 65, and BBCH 89 for cherry and BBCH 57, BBCH 65, and BBCH 89 in apple orchards were identified.

All statistical tasks for the present study were performed using R Statistical Software v. 4.4.0 [53,57].

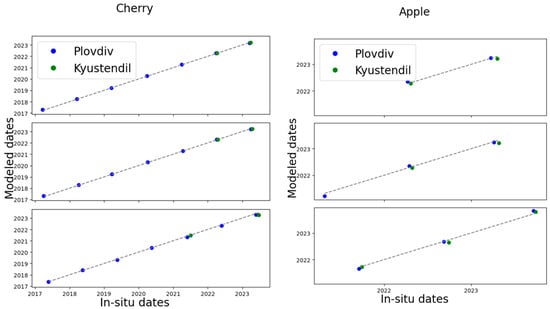

2.5. LSP Modeling

LSP research typically follows the following steps [58]: (1) data processing: converting raw satellite data into a measure of vegetation health, such as a vegetation index; (2) time series generation: creating a smooth and continuous record of vegetation changes over time; (3) metric extraction: identifying seasons and key moments in the vegetation cycle, such as the beginning and end of growing seasons; and (4) validation: comparing satellite-derived results with ground-based observations. Land surface phenology (LSP) studies how vegetation changes over time and space, as observed from satellite imagery [59,60]. We followed the steps outlined to analyze LSP using remotely sensed data. Time series reconstruction and phenological metric extraction were performed using the free DATimeS tool [57]. We used a modified version of DATimeS known as the “Intercomparison tool VIs”, which can be downloaded from the ARTMO toolbox page (https://artmotoolbox.com/) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Steps for phenological analysis with Sentinel-2 data.

DATimeS uses a method to identify changes in the growing season by searching for local minima and maxima in the growth curve. A salience threshold is used to filter out noise and artifacts. This threshold determines whether a peak is significant enough to be considered a true seasonal change. Adjusting the salience threshold fine-tunes the method’s sensitivity, helping avoid false season identification. In this study, we tested visibility thresholds at 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% in 10% increments. Our results show that a 20% salience threshold provides the most accurate results. The growing seasons of cherries and apples typically occur within a single calendar year. Therefore, when two growing seasons are detected within a single year, they are merged by concatenating the two seasons. We used two methods to reconstruct the time series: sigmoid and Gaussian process regression (GPR) [61]. The double logistic curve, or sigmoid, uses a double-sigmoidal model by combining two regular sigmoidal functions to characterize phenological indices [51]. The double sigmoidal model is uniquely defined by six parameters: two midpoints (c and d), two slope parameters (d and e), a maximum value (b), and a baseline (a). GPR is a kernel-based, non-parametric method. It fits a curve without making strong assumptions about the shape. The kernel function used in our study is the Squared Exponential kernel (SE). The choice of kernel hyper-parameters minimizes the squared prediction error while maximizing the marginal likelihood. Phenological indices, such as the start of season (SoS) and end of season (EoS), are derived from the seasonal amplitude. This amplitude is calculated as the difference between the peak value and the average of the left and right minimum values for each season. SoS and EoS are determined at the point where the left or right side of the curve reaches a certain fraction of this seasonal amplitude. In this study, we examined seasonal amplitude at 5% increments, ranging from 5% to 95%. We analyzed the seasonal amplitudes of SoS to identify the three phenological stages, BBCH57, BBCH65, and BBCH89. For BBCH89, we also estimated the seasonal amplitude of EoS. The dual analysis for BBCH87/89 was necessary because it was unclear whether this stage occurred before or after the peak values of the studied VIs, as evident in the original remote sensing data (Figure 4). In summary, as indicated in Table 3, we used the following parameters in the modified version of DATimeS, known as the “internal comparison VIs tool”.

Table 3.

Input parameters in the modified version of DATimeS, known as the “internal comparison VIs tool”.

The phenology metrics evaluation is performed using the root-mean-square error (RMSE) with the equations:

where:

—measured (in situ) on the date of observation i.

—modeled date for observation i.

N—the total number of observations.

For metric calculations, all dates were converted to the number of days from January 1st of the corresponding season.

3. Results

3.1. Empirical Models

For the Random Forest algorithm, the two datasets for Plovdiv and Kyustendil, which include daily and hourly air temperature values, were split into training and test sets. Specifically, 75% of the data were used for training, and the remaining 25% for testing. The number from classification decision trees was set to 600. As predictors, the following daily parameters are used: CU, GDD, GDH, and Julian Day (the day of the year).

By using the mentioned algorithm, we first evaluated the importance of the parameters used in forecasting the discrimination in the different phases—bud burst, flowering, and fruit ripening based on the values of the predictors. The influence of each predictor for cherries and apples in both experimental fields is shown in Table 4. Although the importance percentages are similar across all predictors, GDH appears to be the most important across all data sets, followed by day.

Table 4.

Importance of parameters for cherry orchards in Kyustendil and Plovdiv for the whole stages of investigation (from bud burst to fruit ripening).

After applying machine learning with the selected algorithm, data on the distribution of predicted cases across the investigated phenological phases were obtained. The results from testing the cherry model (Table 5 and Table 6) demonstrate clear differentiation of cases by phenological phase.

Table 5.

Random forest number of cases for cherry development prediction for the investigated stages in Kyustendil and Plovdiv.

Table 6.

Random forest number of cases for apple development prediction for the investigated stages in Kyustendil and Plovdiv.

The average values of the date of onset of the BBCH 57, BBCH 65, and BBCH 87/89 phases for cherry and apple, and the sums of GDD and GDH for each of the mentioned phases by year were obtained (Table 7 and Table 8). The specific meteorological conditions during the three-year study period affect the timing of individual phenophases, which are directly dependent on GDH and GDD values.

Table 7.

Values of predictors on occurrence for cherry different phenological stages for the validation period for Kyustendil and Plovdiv.

Table 8.

Values of predictors on occurrence for apple different phenological stages for the validation period for Kyustendil and Plovdiv.

By applying the Random Forest algorithm, a high degree of prediction for the occurrence of the studied phases in cherry plantations was achieved, with an accuracy range of −2 to +1 days, compared to our ground observations in Kyustendil and Plovdiv during the study period 2021–2023. For apple plantations, the deviations are larger, ranging from −6 to +2 days, at the exact locations and during the same study period (Table 9).

Table 9.

Predicted days’ deviations in dependence on observed cherry and apple development in Kyustendil and Plovdiv.

3.2. Sentinel-2 Results

The best results are presented in Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13. The best results are selected according to (1) the number of seasons detected closest to the actual number, and (2) the lowest root mean square error (RMSE).

3.2.1. By Location and Fruit Tree

For each location and fruit tree type, the best RMSE for BBCH57 ranges from 4 to 12 days, for BBCH65 from 5 to 23 days, and for BBCH87/89 from 8 to 27 days. NDVI outperforms EBI in most cases. An exception is observed for Plovdiv apple trees at BBCH 87/89, where EBI outperforms NDVI. GPR outperforms sigmoid at the Kyustendil location, while sigmoid gives better results at the Plovdiv location. There is no clear pattern to indicate whether SoS or EoS is a more suitable phenological indicator for BBCH 87/89.

- With GPR

Table 10.

Best RMSE with GPR modeling for each location and fruit tree. AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

Table 10.

Best RMSE with GPR modeling for each location and fruit tree. AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

| Location, Fruit Tree | SoS for BBCH57 | SoS for BBCH65 | BBCH87/89 as |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plovdiv, apple | Samples: 2, RMSE = 17, with NDVI& = 0.2 | Samples: 3, RMSE = 26, with NDVI& = 0.3 | Samples: 3, EoS: RMSE = 13, with EBI& = 0.55 |

| Plovdiv, cherry | Samples: 7, RMSE = 18 with NDVI& = 0.35 | Samples: 7, RMSE = 21, with NDVI& = 0.5 | Samples: 7, SoS: RMSE = 38, with NDVI& = 0.7 |

| Kyustendil, apple | Samples: 2, RMSE = 10, with NDVI& = 0.8 | Samples: 2, RMSE = 9, with NDVI& = 0.95 | Samples: 3, SoS: RMSE = 25, with NDVI& = 0.7 |

| Kyustendil, cherry | Samples: 2, RMSE = 4, with NDVI& = 0.65 | Samples: 2, RMSE = 5, with NDVI& = 0.85 | Samples: 2, EoS: RMSE = 12, with NDVI& = 0.95 |

- With Sigmoid

Table 11.

Best RMSE with sigmoid modeling for each location and fruit tree. AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

Table 11.

Best RMSE with sigmoid modeling for each location and fruit tree. AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

| Location, Fruit Tree | SoS for BBCH57 | SoS for BBCH65 | BBCH87/89 as |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plovdiv, apple | Samples: 2, RMSE = 8, with NDVI& = 0.05 | Samples: 3, RMSE = 23, with NDVI& = 0.1 | Samples: 3, SoS: RMSE = 24, with NDVI& = 0.9 |

| Plovdiv, cherry | Samples: 7, RMSE = 12, with NDVI& = 0.4 | Samples: 7, RMSE = 12, with NDVI& = 0.55 | Samples: 7, SoS: RMSE = 27, with NDVI& = 0.85 |

| Kyustendil, apple | Samples: 2, RMSE = 15, with NDVI& = 0.55 | Samples: 2, RMSE = 20, with NDVI& = 0.55 | Samples: 3, SoS: RMSE = 27, with NDVI& = 0.85 |

| Kyustendil, cherry | Samples: 2, RMSE = 7, with NDVI& = 0.65 | Samples: 2, RMSE = 10, with NDVI& = 0.85 | Samples: 2, EoS: RMSE = 8, with NDVI& = 0.95 |

3.2.2. Results by Fruit Tree Type

For each fruit tree type, regardless of location, the best RMSE for BBCH 57 ranged from 12 to 23 days, for BBCH 65 from 14 to 29 days, and for BBCH 87/89 between 26 and 36 days. NDVI outperformed EBI. SoS proved to be a more appropriate phenological metric for BBCH 87/89. GPR outperformed sigmoid for apple trees in two phenostages, while sigmoid gave better results for cherry trees and BBCH87/89 for both fruit tree types.

- With GPR

Table 12.

Best RMSE with GPR modeling for the two locations, Plovdiv and Kyustendil, and by fruit tree type. BBCH89 for cherry and BBCH87 for apple AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

Table 12.

Best RMSE with GPR modeling for the two locations, Plovdiv and Kyustendil, and by fruit tree type. BBCH89 for cherry and BBCH87 for apple AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

| Location, Fruit Tree | SoS for BBCH57 | SoS for BBCH65 | BBCH87/89 as |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plovdiv and Kyustendil, cherry | Samples: 9, RMSE = 18, with NDVI& = 0.4 | Samples: 9, RMSE = 21, with NDVI& = 0.6 | Samples: 9, EoS: RMSE = 60, with EBI& = 0.75 |

| Plovdiv & Kyustendil, apple | Samples: 4, RMSE = 23, with NDVI& = 0.3 | Samples: 5, RMSE = 29, with NDVI& = 0.3 | Samples: 6, EoS: RMSE = 29, with EBI& = 0.55 |

- With Sigmoid

Table 13.

Best RMSE with sigmoid modeling for the two locations, Plovdiv and Kyustendil, and by fruit species, BBCH89 for cherry and BBCH87 for apple. AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

Table 13.

Best RMSE with sigmoid modeling for the two locations, Plovdiv and Kyustendil, and by fruit species, BBCH89 for cherry and BBCH87 for apple. AMP stands for seasonal amplitude.

| Location, Fruit Tree | SoS for BBCH57 | SoS for BBCH65 | BBCH87/89 as |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plovdiv & Kyustendil, cherry | Samples: 9, RMSE = 12, with NDVI& = 0.4 | Samples: 9, RMSE = 14, with NDVI& = 0.55 | Samples: 9, SoS: RMSE = 36, with NDVI& = 0.85 |

| Plovdiv and Kyustendil, apple | Samples: 4, RMSE = 27, with NDVI& = 0.1 | Samples: 5, RMSE = 30, with NDVI& = 0.2 | Samples: 6, SoS: RMSE = 26, with NDVI& = 0.85 |

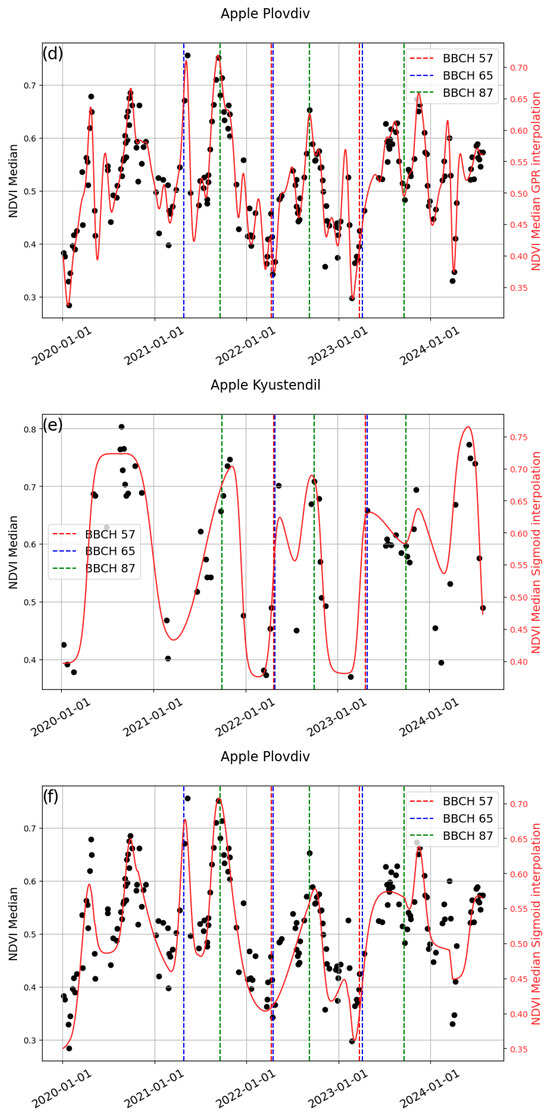

The best results for BBCH57 and BBCH65 by fruit tree type, regardless of location, were obtained by GPR for apple (Table 12 and Figure 6b,d) and sigmoid for cherry (Table 13 and Figure 6a,c). The best results, by fruit tree type, regardless of location, were obtained for apple at BBCH 87 (Figure 6e,f) and for cherry at BBCH 89 (Figure 6a,c) with the sigmoid model. The scatterplot of the best results by fruit tree type, regardless of location, is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Original, in black, and interpolated, in red, Sentinel-2 NDVI time series with in situ dates for BBCH 57, BBCH 65, and BBCH 87 for apple, and BBCH 89 for cherry.

Figure 7.

Scatter plot between measured in situ phenological dates and modeled dates for BBCH 57, top figures; for BBCH 65, middle figures; for BBCH 89 for cherry, bottom left; and BBCH 87 for apple, bottom right.

Figure 6a,c, for sweet cherries, shows the bell-shaped curve of the reconstructed NDVI for the growing season. The studied phenological stages are often located on the rising part of the curve or close to the SoS metric.

In Figure 6b,d–f, the reconstructed NDVI curve for apples during the growing season typically exhibits two bell-shaped peaks: one around BBCH 57 and BBCH 65, and another around BBCH 87. This pattern suggests a change in the spectral signal between BBCH 65 and BBCH 87, probably due to a decrease in canopy greenness. This can be attributed to the phenological pattern of apple trees, in which leaves appear first, followed by inflorescences bearing white flowers.

4. Discussion

4.1. With an Empirical Model

Through RF classification, a prognostic value of the day for the occurrence of each of the phases—bud swelling, bud bursting, flowering, and fruit ripening—was obtained after passing the average day-night temperatures above 5 °C, during which the phenological phases of flowering and fruit ripening occur in cherry and apple orchards at the studied sites. It was established that for cherries in Kyustendil, the necessary temperature sum for flowering depends mainly on the size of the cold units (CUs) during dormancy and the sum of the active temperatures during dormancy (GDH) for the beginning of the bud burst phase. For cherry ripening, this model dependence is determined in the same way, using the same CUs and GDD as for bud burst. Similarly, empirical dependences were obtained for the flowering and fruit ripening of apples in the orchards of Kyustendil. It was found that the GDH indicator does not affect the flowering process during dormancy either. The exact dates of bud break, flowering, and fruit ripening are determined by converting the predicted day number into a date from the beginning of the year.

4.2. With Sentinel-2

Using cloud-free Sentinel-2 data (≤5% cloud cover), we applied a Land Surface Phenology (LSP) approach to model three phenological stages—BBCH57, BBCH65, and BBCH87/89—in apple and sweet cherry orchards at two locations, Kyustendil and Plovdiv. We used a freely available, modified version of DATimeS called “Intcomparson tool VI”. Phenological stages were modeled using NDVI and EBI derived from quasi-cloud-free Sentinel-2 observations and fitted with both Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) and sigmoid models. Seasonal amplitudes derived from the start of season (SoS) and end of season (EoS) were used to estimate phenological timing, and the modeled phenological stages were evaluated against field observations.

NDVI outperformed EBI in most cases. However, no single modeling approach consistently outperformed the others, as model performance depended strongly on the quality and temporal density of the input data. As depicted in Figure 8, GPR closely adheres to the original data points, while the sigmoid generates smoother curves.

Figure 8.

Example of curve fitting and field data for the studied stages for (a) Kyustendil—cherry; (b) Plovdiv—cherry; (c) Kyustendil—apple; (d) Plovdiv—apple.

Across locations and fruit tree types, the best root mean square error (RMSE) for phenological stage detection ranged from 4 to 27 days (Table 10 and Table 11). No consistent pattern was observed regarding whether SoS or EoS was a more suitable phenological indicator for BBCH89, partly due to the limited number of field observations in some datasets. In orchard types and locations with only two in situ measurements, model performance was less stable, underscoring the importance of data aggregation.

To address this limitation, datasets were aggregated by fruit tree type irrespective of location, thereby increasing the number of samples per cluster. Under this aggregation, the best RMSE values for phenological stage estimation ranged from 12 to 36 days (Table 12 and Table 13). NDVI again outperformed EBI, and SoS emerged as the more suitable phenological metric for BBCH89. GPR outperformed the sigmoid model for apple trees in two phenological stages, whereas the sigmoid model performed better for cherry trees and for BBCH89 in both fruit tree species (Figure 6a–f).

For sweet cherry orchards, regardless of location, the sigmoid model achieved the best RMSE values of 12, 14, and 36 days for BBCH57, BBCH65, and BBCH89, respectively. For apple orchards, GPR yielded the best RMSE for BBCH57 and BBCH65 (23 and 29 days, respectively), while the sigmoid model provided the best performance for BBCH87, with an RMSE of 26 days.

The detection of phenological changes can be affected by several factors, as detailed below.

Errors or artifacts in the remote sensing data can distort the phenological signals [51], and the chosen method may have inherent shortcomings that affect the detection accuracy [51]. For example, GPR generally performed better when the number of available images was limited, whereas the sigmoid model showed superior performance for datasets with a higher temporal resolution. GPR outperformed sigmoid for the BBCH 57 and BBCH 65 stages in Kyustendil. This suggests that GPR better accommodates the limited data points. Conversely, the abundance of Plovdiv data allowed sigmoid to effectively simplify the underlying complexity, resulting in superior performance compared to GPR, as shown in Table 10 and Table 11.

Observation of phenology at the level of an individual plant or fruit variety may differ from the larger scale captured by satellite imagery, leading to potential discrepancies [51]. This study did not analyze phenology at the level of individual plants or varieties, but rather the mass occurrence of the studied stages. In Plovdiv, we studied three apple and cherry varieties, each with different dates for the onset of the stages BBCH 57, BBCH 65, and BBCH 87/89. However, we did not differentiate among these varieties and instead treated them as a single fruit species. In Kyustendil, we analyzed two apple varieties, while the cherry analysis focused on one variety. In Plovdiv, we examined three apple and cherry varieties. The standard deviation across phenostages per tree type ranged from 2 to 16 days (see the crop calendar in the figure), which may partly explain the higher RMSE observed when detecting the different phenostages studied.

Vegetation cover significantly affects the ability to detect phenological changes [51] and environmental factors accurately. The timing of phenological events can change rapidly; so, frequent satellite observations are crucial. Unfortunately, cloud cover often limits the availability of explicit images, making it difficult to accurately track these changes [51]. The vegetation cover of the study area is not homogeneous. In the plots in Plovdiv, there was no grass between the trees in the inter-row, whereas in Kyustendil, there was grass cover in the rows. The presence of mixed pixels—including trees, grass, or soil—adds complexity to the phenological analysis based on satellite observations; see the explanation in Section 2.2. Data collection is another complication arising from the different phenological patterns of the trees: cherry trees’ leaves appear before flowering, while in apple trees, the appearance of leaves precedes flowering.

When working with fewer high-quality observations, it becomes more challenging to estimate phenological dates reliably, and in some cases, it may even be impossible to detect phenological events. In our study, the time series from Plovdiv has nearly three times as many observation dates for apples and cherries as those from Kyustendil. Despite this advantage, the phenological detection results from Plovdiv do not outperform those from Kyustendil. In addition to temporal resolution, spatial resolution has been identified as a major source of uncertainty and bias in the extraction of phenological information from satellite imagery [51]. In our study, most pixels are likely mixed, given the Sentinel-2 spatial resolution, the horizontal projection of tree crowns, and the spacing between trees.

For BBCH87/89, we analyzed the seasonal amplitudes of SoS and EoS. This double analysis was necessary because it was uncertain whether this stage occurs before or after the peak values of the studied VI. Furthermore, detecting this stage using remote sensing is challenging, as fruits are often hidden under leaves, and some, such as green apples, do not have pronounced color changes.

Furthermore, due to environmental factors, different locations may exhibit varying levels of seasonal variation, which affects each model’s ability to capture phenological changes adequately. For example, locations with extreme temperature or precipitation fluctuations may yield inaccurate estimates using satellite observations, making accurate predictions more challenging for specific applications.

Few studies have analyzed orchard phenology using satellite imagery [56], and several challenges remain in accurately detecting phenological stages. One key factor is the quality of satellite imagery, including the accurate detection of clouds and shadows, which influences the choice of curve-fitting technique. However, finding the optimal curve-fitting method for different vegetation types and satellite data remains a complex task.

It is challenging to accurately estimate the phenological characteristics of individual fruit species represented in satellite phenology data [62]. Future research should aim to integrate observations from multiple sources and at different scales to enhance the understanding of the relationship between remotely sensed phenology and the biometric and physiological characteristics of plants.

Our study included 3 years of phenological observations, except for cherries in Plovdiv, where we had 7 years of data. A larger number of field observations is needed to analyze the applicability of LSP for cherries and apples comprehensively. Digital cameras provide a reliable, consistent method for ground-based satellite phenological observations [63]. By providing standardized measurements and definitions, they can improve the accuracy and reliability of long-term phenological monitoring.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies key characteristics in the growth, and development of cherry and apple orchards in Kyustendil and Plovdiv during a field experiment (2021–2023 for three important phenostages of the studied cherry and apple orchards: bud swelling (BBCH57), flowering (BBCH65), and fruit ripening (BBCH87/89). Using statistical forecasting (Random Forest) and LSP, empirical relationships between phenology and other variables have been established. The forecasting model utilizes meteorological data, whereas the LSP method relies on phenological indicators derived from Sentinel-2 satellite images. The most significant results related to the application of these two approaches are the following:

- With LSP modeling, NDVI outperforms EBI in most cases. Depending on the dataset, GPR or sigmoid models performed better. SOS proved to be the more appropriate phenological metric for BBCH 87/89. The best RMSE for cherry and apple trees falls within 12 to 36 days, but it is unsuitable for operational use in orchard monitoring. Modeling homogeneous and large orchards of only one species should provide better results using Sentinel-2 images.

- All results presented in this study are at the species level. Attempts at separation by variety are tentative and possible only if the variety data are presorted. This type of separation is difficult or impossible to perform numerically and remotely from satellite images at this stage.

- In compiling the empirical relationships, multi-year average values of GDD for mass occurrence of bud burst, flowering, and fruit ripening were used as predictors. In addition, the values of CU and GDH from the dormant period, and GDD for bud swelling were used as predictors.

- To prepare more precise forecasts, it is recommended to combine both methods, as their positive qualities complement each other well. Satellite images facilitate the mapping of fruit plant conditions and development, while meteorological and agrometeorological indices data support the forecasting process. These data are recommended for predicting the timing of bud burst, flowering, and fruit ripening.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and E.R.; data curation, M.N. and S.M., methodology, M.N., S.D., S.M., V.G., A.S., D.G. and E.R.; visualization, G.J. and D.G.; formal analysis, V.G., B.T., P.M., and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation—V.K., E.R. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, V.K., E.R. and D.G.; supervision V.G.; funding—V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Decision of the Council of Ministers No. 866/26.11.2020, PO-09-11, dated 12 April 2021.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science under the National Research Program “Smart Plant Breeding,” as approved by Decision of the Council of Ministers No. 866/26.11.2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pio, R.; de Souza, F.B.M.; Kalcsits, L.; Bisi, R.B.; Farias, D.H. Advances in the production of temperate fruits in the tropics. Acta Sci. 2019, 41, e39549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoy, J.A.; Ruiz, D.; Egea, J. Dormancy in temperate fruit trees in a global warming context: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadón, E.; Fernández, E.; Behn, H.; Luedeling, E. A conceptual framework for winter dormancy in deciduous trees. Agronomy 2020, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wu, X.; Moriguchi, T.; Bai, S.; Teng, Y. Bud endodormancy in deciduous fruit trees: Advances and prospects. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saure, M.C. Dormancy release in deciduous fruit. Hortic. Rev. 2011, 7, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Mounzer, O.H.; Conejero, W.; Nicolás, E.; Abrisqueta, I.; Garcia-Orellana, Y.V.; Tapia, L.M.; Vera, J.; Abrisqueta, J.M.; del Carmen Ruiz-Sánchez, M. Growth pattern and phenological stages of early-maturing peach trees under a Mediterranean climate. HortScience 2008, 43, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, M.R.; Jones, J.W.; Chaves, B.; Cooman, A.; Fischer, G. Base temperature and simulation model for nodes appearance in Cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.). Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2008, 30, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viator, R.P.; Nuti, R.C.; Edmisten, K.L.; Wells, R. Predicting cotton boll maturation period using degree days and other climatic factors. Agron. J. 2005, 97, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeckeritz, C.; Hollender, C.A. There is more to flowering than those DAM genes: The biology behind bloom in rosaceous fruit trees. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 59, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicenta, F.; García-Gusano, M.; Ortega, E.; Martinez-Gómez, P. The possibilities of early selection of late-flowering almonds as a function of seed germination or leafing time of seedlings. Plant Breed. 2005, 124, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.D.; Keenan, T.F.; Migliavacca, M.; Ryu, Y.; Sonnentag, O.; Toomey, M. Climate change, phenology, and phenological control of vegetation feedbacks to the climate system. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 169, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haokip, S.W.; Shankar, K.; Lalrinngheta, J. Climate Change and Its Impact on Fruit Crops. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Grab, S.; Craparo, A. Advance of apple and pear tree full bloom dates in response to climate change in the south-western Cape, South Africa: 1973–2009. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedwan, N.; Rhoades, R.E. Climate change in the Western Himalayas of India: A study of local perception and response. Clim. Res. 2001, 19, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narandžić, T.; Ljubojević, M.; Ostojić, J.; Barać, G.; Ognjanov, V. Investigation of stem anatomy about hydraulic conductance, vegetative growth, and yielding potential of ‘Summit’ Cherry trees grafted on different rootstock candidates. Folia Hortic. 2021, 33, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglovski, M.; Dawidko, T. Wpliw Przewodniej na Regeneracje Uszkodzen Mrozowych u Odmiany Idared. Prace ISK-Skierniewire, No 1-4; University of Prgue: Prague, Czech Republic, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jaumien, F.; Starzynski, R. Ocena Uszkodgen Mrozowych Drzew Jabloni Odmiany Bankroft po Zimie 1986/87; Prace ISK Skierniewicach, No 1-4; University of Prgue: Prague, Czech Republic, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, V.; Borovinova, M.; Koleva, A. Cherry; Matkom: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2007; p. 351. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Aygün, A.; Şan, B. The late-spring frost hardiness of some apple varieties at various stages of flower bud development. Tarim Bilim. Derg. 2005, 11, 283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasz, L.; Lipecki, J.; Janisz, A.; Sienkiewicz, P. Effects of spring frosts in selected apple and pear orchards in the Lublin region in the years 2000, 2005, and 2007. Acta Agrobot. 2008, 61, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cebulj, A.; Mikulič-Petkovšek, M.; Veberič, R.; Jakopic, J. Effect of Spring Frost Damage on Apple Fruit (Malus domestica Borkh.) Inner Quality at Harvest. Agriculture 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirsoy, H.; Demirsoy, L.; Lang, G.A. Research on spring frost damage in cherries. Hort. Sci. 2022, 49, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccher, T.; Hajnaajar, H. Fluctuations of endogenous gibberellin A4 and A7 content in apple fruits with different sensitivity to russet. Acta Hortic. 2006, 727, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccel, E.; Rea, R.; Caffarra, A.; Crisci, A. Risk of spring frost to apple production under future climate scenarios: The role of phenological acclimation. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 53, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanke, M.; Kunz, M.A. Effects of climate change on pome fruit phenology and precipitation. Acta Hortic. 2011, 922, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhelev, Z. Development Conditions and Prognosis of Dangerous Pathogens in Cereal Crops. “Plant protection”. 2018. Available online: https://www.plant-protection.com/article/852?lang=en (accessed on 7 January 2026). (In Bulgarian)

- Ilic, M.; Ilic, S.; Jovic, S.; Panic, S. Early Cherry fruit pathogen disease detection based on data mining prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 150, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Giosuè, S.; Bugiani, R. A-scab (Apple-scab), a simulation model for estimating the risk of Venturia inaequalis primary infections. EPPO Bull. 2007, 37, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Wang, T.C.; Yang, X.B. Simulation of apparent infection rate to predict severity of soybean rust using a fuzzy logic system. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Darbyshire, R.; Lopez, N.J.; Song, X.; Wenden, B.; Close, D. Modeling Cherry full bloom using ‘space-for-time’ across climatically diverse growing environments. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 284, 107901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Xu, F.; Bento, V.A.; Zhang, R.; Wu, X.; Guo, P. Understanding vegetation phenology responses to easily ignored climate factors in China’s mid-high latitudes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.T.; NeSmith, D.S. Temperature and crop development. In Modeling Plant and Soil Systems; Hanks, J., Ritchie, J.T., Eds.; Agronomy Monographs Serie; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; Volume 31, pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, D.; Honek, A.D.L.I.; Li, D.; van Straalen, N.M. Thermal time–concepts and utility. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2005, 146, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmaus, S.J.; Prather, T.S.; Holt, J.S. Estimation of Base Temperatures for Nine Weed Species. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.H.; Covell, S.; Roberts, E.H.; Summerfield, R.J. The influence of temperature on seed germination rate in grain legumes. J. Exp. Bot. 1986, 37, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, C.; Tardieu, F. Water deficit and spatial pattern of leaf development: Variability in responses can be simulated using a simple model of leaf development. Plant Physiol. 1999, 119, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, T.; Aikawa, M.; Miller, L.H. Plasmodium knowlesi: Studies on invasion of rhesus erythrocytes by merozoites in the presence of protease inhibitors. Exp. Parasitol. 1983, 55, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegis, A. Dormancy in Higher Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 1964, 15, 185–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G.A.; Lang, G.; Early, J.D.; Martin, G.C.; Darnell, R.L.; Martin, A.J.; Darnell, R.; Lang, G.; Early, J.D.; Martin, A.J.; et al. Endodormancy, Paradormancy, and Ecodormancy-Physiological Terminology and Classification for Dormancy Research. Hortscience 1987, 22, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, O.M.; Prestrud, O.M. Low temperature, but not photoperiod, controls growth cessation and dormancy induction and release in apple and pear. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landsberg, J. Apple Fruit Bud Development and Growth; Analysis and an Empirical Model. Ann. Bot. 2005, 38, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannell, M.G.R.; Smith, R.I. Thermal Time, Chill Days and Prediction of Budburst in Picea sitchensis. J. Appl. Ecol. 1983, 20, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, B.D.; Ryba, T.; Dileep, V.; Yue, F.; Wu, W.; Denas, O.; Vera, D.L.; Wang, Y.; Hansen, R.S.; Canfield, T.K.; et al. Topologically associating domains are stable units of replication- timing regulation. Nature 2014, 515, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernecki, B.; Nowosad, J.; Jabłońska, K. Machine learning modeling of plant phenology based on coupling satellite and gridded meteorological dataset. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenden, B.; Campoy, J.A.; Lecourt, J.; López Ortega, G.; Blanke, M.; Radičević, S.; Schüller, E.; Spornberger, A.; Christen, D.; Magein, H.; et al. A collection of European.Cherry phenology data for assessing climate change. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimont, N.; Schwarzenberg, A.; Domijan, M.; Donkpegan, A.S.L.; Beauvieux, R.; le Dantec, L.; Arkoun, M.; Jamois, F.; Yvin, J.-C.; Wigge, P.A.; et al. Fine-tuning of hormonal signaling is linked to dormancy status in sweet Cherry flower buds. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castède, S.; Campoy, J.A.; García, J.Q.; Le Dantec, L.; Lafargue, M.; Barreneche, T.; Wenden, B.; Dirlewanger, E. Genetic determinism of phenological traits highly affected by climate change in Prunus avium: Flowering date dissected into chilling and heat requirements. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henebry, G.M.; de Beurs, K.M. Remote sensing of land surface phenology: A prospectus. In Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science; Schwartz, M.D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Jacob, F.; Duveiller, G. Remote Sensing for Agricultural Applications: A Meta-Review. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.; Deering, D. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the Goddard Space Flight Center 3d ERTS-1 Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 December 1973; NASA Special Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Wardlow, B.D.; Xiang, D.; Hu, S.; Li, D. A Review of Vegetation Phenological Metrics Extraction Using Time-Series, Multispectral Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros-Santiago, J.A.; Rodriguez-Galiano, V.; Dash, J. Land Surface Phenology as an Indicator of Global Terrestrial Ecosystem Dynamics: A Systematic Review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 171, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Richardson, E.A.; Kesner, C.D. Validation of chill unit and flower bud phenology models for “Montmorency” sour cherry. Acta Hort. 1986, 184, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.A.; Seeley, S.D.; Walker, D.R. A model for estimating the completion of rest for ‘Redhaven’ and ‘Alberta’ peach trees. HortScience 1974, 9, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, U.; Graf, H.; Hess, M.; Kennel, W.; Klose, R.; Mappes, D.; Seipp, D.; Stauss, R.; Streif, J.; van den Boom, T. Phänologische Entwicklungsstadien des Kernobstes (Malus domestica Borkh. und Pyrus communis L.), des Steinobstes (Prunus-Arten), der Johannisbeere (Ribes-Arten) und der Erdbeere (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.). Nachrichtenbl. Deut. Pflanzenschutzd. 1994, 46, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Jin, Y.; Brown, P. An enhanced bloom index for quantifying floral phenology using multi-scale remote sensing observations. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 156, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, S.; Pipia, L.; Morcillo-Pallarés, P.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P.; Amin, E.; De Grave, C.; Verrelst, J. DATimeS: A Machine Learning Time Series GUI Toolbox for Gap-Filling and Vegetation Phenology Trends Detection. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 127, 104666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, L.; Berger, K.; Brede, B.; Graf, L.V.; Aasen, H.; Roujean, J.-L.; Machwitz, M.; Schlerf, M.; Atzberger, C.; Prikaziuk, E.; et al. Reviews and syntheses: Remotely sensed optical time series for monitoring vegetation productivity. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 473–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beurs, K.M.; Henebry, G.M. Land Surface Phenology, Climatic Variation, and Institutional Change: Analyzing Agricultural Land Cover Change in Kazakhstan. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 89, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beurs, K.M.; Henebry, G.M. Land Surface Phenology and Temperature Variation in the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program High-Latitude Transects. Glob. Change Biol. 2005, 11, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.; Williams, C. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; The MIT Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Berra, E.F.; Gaulton, R. Remote Sensing of Temperate and Boreal Forest Phenology: A Review of Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities in the Intercomparison of in-Situ and Satellite Phenological Metrics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 480, 118663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.D.; Braswell, B.H.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Jenkins, J.P.; Ollinger, S.V. Near-Surface Remote Sensing of Spatial and Temporal Variation in Canopy Phenology. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.