Abstract

Exogenous application of methyl jasmonate (MeJ) at different concentrations (0, 1, 10, and 100 µM) during flowering was studied for its impact on phytochemical profile, antioxidant activity, and biomass accumulation in hemp inflorescences of the monoecious cv. Codimono. MeJ treatments had no significant effect on CBD levels, while a 23–54% decrease in total terpene levels was observed in plants treated with 1 and 10 μM MeJ. In particular, MeJ treatments reduced β-caryophyllene and α-humulene levels by 24–43%, α-bisabolol levels by 30–40%, and α-pinene, β-pinene, and β-myrcene levels by 32–61%. By contrast, MeJ treatments had a positive effect on all other classes of phytochemicals analyzed. Plants treated with 100 μM MeJ experienced the highest increases in total flavonoid and phenolic acid levels (+42% and +50%, respectively). In particular, this treatment increased orientin, vitexin, and isovitexin levels by 36–52%, while ferulic acid level increased by 103%. Treatments with 10 and 100 µM MeJ resulted in the highest increases in total carotenoid and tocopherol levels (+41% and +33%, respectively). In particular, lutein, β-carotene, and α-tocopherol levels increased by 44%, 35%, and 36%, respectively. In line with these findings, total antioxidant activity increased by 26% following treatment with 100 μM MeJ and by 13% following the other two treatments. Interestingly, MeJ treatments did not affect plant growth and biomass accumulation in the inflorescences. This implies higher yields for those phytochemicals whose concentrations were increased by MeJ. In summary, our results indicate that hemp plants treated with 100 μM MeJ represent an interesting source of phytochemicals, fiber, and biomass. These characteristics make them suitable for multiple industrial applications and enhance both the economic and health-related value of this crop.

1. Introduction

Cannabis sativa L. is an annual crop that belongs to the Cannabaceae family with a long history of domestication that starts from Central Asia [1]. It is primarily dioecious, but monecious cultivars occur to a lesser extent. C. sativa is classified into five chemotypes based on the concentration of the three major cannabinoids, namely, the psychoactive Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and the non-psychoactive cannabidiol (CBD) and cannabigerol (CBG): chemotype I or drug-type or marijuana characterized by a high level of THC (>0.3%), chemotype II or intermediate-type with high levels of both THC (>0.3%) and CBD (>0.5%), and three fiber-type hemp chemotypes that include chemotypes III and IV with low levels of THC (<0.3%) and high levels of CBD (>0.5%) and CBG (>0.3%), respectively, and chemotype V with almost no cannabinoids [2,3].

From ancient civilizations to modern markets, the cultivation and use of hemp have evolved significantly. Hemp was one of the first plants to be used for its fiber in the production of ropes, sails, clothing, and paper. However, in the 20th century, hemp’s importance declined due to the emergence of synthetic fibers. The enactment of strict anti-drug laws, which lumped hemp with marijuana, banned its cultivation, possession, and use in many countries. In the 21st century, legislative changes distinguished hemp from marijuana based on THC content and re-legalized hemp cultivation. This led to a new interest in hemp, which gained popularity as a sustainable and environmentally friendly crop for its ability to grow with minimal use of pesticides and fertilizers. It also found innovative applications in the production of emerging green materials, such as insulation, biocomposites, and bioplastics, as well as bioethanol and biofuels [4].

In addition, there is a growing interest in the hemp inflorescence and its wide range of chemically active compounds. The most important and abundant phytochemicals are cannabinoids, which are synthesized and accumulated in the glandular trichomes of the inflorescences and leaves in their acidic form. These acidic cannabinoids are thermally unstable and can be converted to the neutral form when exposed to favorable environmental conditions like high light or heat [5]. As said above, the inflorescences of hemp cultivars mainly accumulate CBD or CBG, which have no psychoactive effects but have recognized beneficial effects of medical relevance mediated by their interaction with the human endocannabinoid system. Notably, CBD is currently used as an ingredient of a drug approved for the treatment of seizures. Also, several studies have demonstrated its efficacy in treating pain, inflammation, epilepsy, and other neuropsychiatric disorders, including anxiety and schizophrenia [6]. CBG has also been identified as a potential treatment for neurological disorders, as well as inflammatory bowel disease [7]. Although researchers have focused on the major cannabinoids, the phytochemical characterization of the hemp plant has also revealed the presence of a number of non-cannabinoid compounds. Indeed, terpenes are also abundant in this crop, where they are responsible for its characteristic aroma [5]. They mainly include monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes that, together with cannabinoids, are produced by the glandular trichomes. These bioactive compounds have been extensively studied for their anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anticonvulsive, antidepressant, anxiolytic, anticancer, neuroprotective, and antidiabetic attributes [8]. In addition to their beneficial properties, terpenes can also enhance the positive effects of cannabinoids through what is known as the “entourage effect” [9]. Another relevant class of phytochemicals in hemp inflorescences is represented by phenolic compounds. These mainly include flavonoids, stilbenes, and lignans, which have all been recognized for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and antimicrobial properties [10]. Although in smaller amounts, other classes of phytochemicals, including alkaloids, tocopherols, carotenoids, and phytosterols, have also been detected in hemp inflorescences [5]. The high content of phytochemicals represents an added value for hemp and expands its potential applications in food, nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries.

In light of this, analyzing the various factors that may affect the accumulation of phytochemical compounds is crucial for optimizing inflorescence quality and commercial value. To date, several studies have examined the effects of genotype, environment, agronomical practices, harvesting stages, and storage conditions [11,12,13,14]. In addition, elicitation is emerging as a successful approach to achieve enhanced production of bioactive compounds in the hemp plant [15]. In particular, our research group has recently focused on the effect of chitosan, a biopolymer derived from chitin, which is able to elicit the defense responses in plants, including the accumulation of secondary metabolites [16]. Our results showed that foliar application of chitosan at the flowering stage significantly increased the accumulation of phenolic compounds and tocopherols, as well as the antioxidant activity of hemp inflorescences [17].

Elicitation of plant secondary metabolism can also be induced by phytohormones, which may act as signaling molecules triggering responses to both biotic and abiotic stresses. Among these, jasmonates are a group of lipid-derived hormones including jasmonic acid and its derivatives, which act synergistically with other phytohormones in response to environmental signals, triggering a series of response mechanisms, including the activation of secondary metabolism. This occurs through the regulation of key secondary metabolism genes (e.g., phenylalanine ammonia lyase, chalcone synthase, terpene synthase), through transcriptional networks controlled by JA-responsive transcription factors [18]. As a result, methyl jasmonate (MeJ), a noteworthy compound derived from jasmonic acid, has been widely employed as an elicitor for stimulating the accumulation of a variety of phytochemicals in different plant species, including medicinal plants [19]. By way of example, exogenous application of 250–500 ppm MeJ was found to increase total phenolic content and total flavonoid content in holy basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum L.), while higher concentrations (750–1000 ppm) increased anthocyanin, β-caryophyllene, and α-humulene content [20]. In lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.), treatments with 10–200 μM MeJ determined an increase in rosmarinic acid content, total phenolic content, and total flavonoid content [21]. An increase in terpenoid content, especially linalool and geraniol, was observed in tea (Camelia sinensis L.) leaves treated with 0.25% MeJ solution [22].

Regarding hemp, the majority of previous studies have focused on plants from chemotype I and chemotype II [15], which are of greater commercial interest due to their pharmaceutical applications. Only in recent years have studies on hemp plants been conducted, but these have been limited to evaluating the effect of MeJ mainly on the cannabinoid and terpene profile [23,24], with little or no attention given to its impact on other classes of phytochemicals. Keeping all this in mind, the current study was designed to investigate how foliar treatments with MeJ affected the accumulation of terpenes and cannabinoids as well as phenolic compounds, carotenoids, tocopherols, and antioxidant activity in the inflorescences of field-grown hemp plants of a chemotype III cultivar. The effect of MeJ treatments on plant growth and biomass accumulation in the inflorescences was also evaluated. The results obtained will be helpful to develop new agronomic practices aimed at improving the amount of compounds of interest and promoting future applications of hemp inflorescences in the food, nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic sectors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

The industrial hemp cv. Codimono was grown at the experimental field of the Research Centre for Cereal and Industrial Crops of Foggia, Italy (41°28′ N, 15°32′ E). The trial lasted from 15 April 2022 (sowing) to 21 August 2022 (inflorescence harvesting). Sixty kg ha−1 seeds were sown in 75 cm row-spaced plots having a surface area of 5 m2. In accordance with standard agronomic practices, the soil was fertilized before sowing, and weeds were manually controlled in the early stages of crop growth. The experimental field design was conducted in completely randomized blocks with four treatments: pure water (control), 1 μM MeJ, 10 μM MeJ, and 100 μM MeJ, and three replicates for each treatment. This MeJA dose range was chosen based on literature, as low to moderate doses (up to 100 µM) promote secondary metabolites without compromising plant growth, while higher doses boost secondary metabolism but may lower plant biomass accumulation [25]. Starting from full flowering (BBCH 65) until the end of flowering (BBCH 69) [26], leaves were sprayed at ten-day intervals with water or MeJ solutions until they were completely soaked. For each replicate, the apical inflorescence of the main stem was harvested from ten randomly selected plants. The pooled inflorescences were dried in a forced ventilation oven set at 40 °C for 72 h and sieved through a 2-mm mesh. Prior to analysis, each sample was finely ground into a powder using a planetary micro mill (Pulverisette 7, Fritsch, Milan, Italy).

2.2. GC/MS Measurements of Cannabinoids and Terpenes

Two hundred milligrams of ground sample were added with 10 μL of internal standard (pentadecane, 11.5 mg mL−1) and extracted with 5.5 mL of n-hexane by using an accelerated solvent extractor (Dionex ASE350, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at the following conditions: 50 °C, 10 MPa, 5 min heating, 15 min static extraction, 1 cycle. One microliter of the extract was analyzed following the method reported in Sicignano and coworkers [27] using a GC/MS system (Agilent 6890A coupled with a Triple Quadrupole mass Spectrometer 7000B, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a HP-5ms capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm film thickness). The injector and the transfer line temperature were set at 280 °C, while the source temperature was set at 240 °C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The oven temperature program began at 60 °C for 1 min, increased to 220 °C at a rate of 8 °C min−1 and maintained for 1 min, then further increased to 280 °C at a rate of 8 °C min−1 and maintained for 25 min. Data acquisition was performed over a mass range of 15–650 m/z and a scan rate of 4.9 scans s−1. The identification of the eluted compounds was carried out by comparing their mass spectra with those of authentic standards or by matching them with the commercial NIST 11 mass spectral library, and further confirmed by comparison of their linear retention indices with those of the n-hydrocarbon series. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed by normalizing peak areas to that of the internal standard. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as μg g−1 dry weight (DW).

2.3. HPLC Measurements

2.3.1. Phenolic Compounds

One hundred milligrams of ground sample were extracted with 5 mL of 80% methanol acidified with 1% HCl. The mixture was sonicated for 30 min at room temperature in an ultrasonic bath (Elmasonic P, Elma Schmidbauer GmbH, Singen, Germany) and then centrifuged at 9000× g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was recovered and analyzed immediately. The analysis of phenolic compounds was performed following the method reported in Beleggia and coworkers [14] by using an HPLC system (Series 1290, Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a degasser, a quaternary pump, an autosampler, a thermostated compartment column, and a diode-array detector (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). The separation was achieved by using a Zorbax SB-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 μm, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a mobile phase consisting of 1% acetic acid (solution A) and acetonitrile (solution B). The chromatographic conditions were set as follows: 0 min, 95% A; 30 min, 85% A; 40 min, 50% A; 44 min, 0% A; 46 min, 95% A; 46–50 min, isocratic elution at 95% A. The flow rate was set to 1 mL min−1, the column temperature to 35 °C, and the injection volume to 10 µL. Phenolic compounds were detected at 280 and 320 nm, and their identification and quantification were carried out using authentic standards. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as μg g−1 of DW.

2.3.2. Carotenoids

Carotenoids were extracted, separated, and quantified following the method reported in Sicignano and coworkers [27] using the same HPLC system employed for phenolic compound analysis, equipped with a C18 column (Synergi 4 μm Hydro RP 250 × 4.6 mm) and a C18 precolumn (4.0 × 3.0 mm) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of water (solution A) and acetone (solution B), and the elution gradient was set as follows: 0–5.1 min, 35% A; 5.1–9.1 min, from 35% to 10% A; 9.1–11.9 min, 10% A; 11.9–13.7 min, from 10% to 0% A; 13.7–16.8 min, 0% A; 16.8–17.7 min from 0% to 35% A; 17.7–23 min, 35% A as post-run. The flow rate was set at 0.8 mL min−1, the column temperature at 30 °C, and the injection volume at 20 μL. Carotenoids were detected at 450 nm, and their identification and quantification were performed using authentic standards. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as μg g−1 DW.

2.3.3. Tocopherols

Tocopherols were extracted, separated, and quantified following the method reported by Sicignano and coworkers [27], using the same HPLC system, column, and precolumn used for the determination of carotenoids. The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of acetonitrile, methanol, and 2-propanol (40:55:5, v/v/v) under isocratic conditions, with a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1 and a total run time of 30 min. The column temperature was set to 30 °C, and the injection volume to 20 μL. Tocopherols were detected using a fluorescence detector set to excitation and emission wavelengths of 290 nm and 330 nm, respectively. Identification and quantification were carried out using authentic standards. β- and γ-tocopherol co-eluted and were therefore measured as a combined content. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as μg g−1 DW.

2.4. Spectrophotometric Assays

All spectrophotometric assays were performed using a PerkinElmer Lambda 650 UV/Vis spectrometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), employing the same extract used for the determination of phenolic compounds by HPLC.

2.4.1. Total Phenolic Content

Total phenolic content (TPC) was determined following the method reported in Beleggia and coworkers [17] with minor modifications. Briefly, 200 μL of methanolic extract diluted 1:5 was mixed with 900 μL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent diluted 1:10 and 900 μL of 6% (w/v) Na2CO3. The mixture was incubated for 2 h in the dark. The absorbance was then measured at 765 nm. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mg of ferulic acid equivalents (FE) g−1 DW.

2.4.2. Total Flavonoid Content

Total flavonoid content (TFC) was measured following the method reported in Beleggia and coworkers [17] with minor modifications. Briefly, 1280 µL of ultrapure water were mixed with 60 µL of 5% (w/v) NaNO2 and 200 µL of methanolic extract diluted 1:2.5. Sixty microliters of 10% (w/v) AlCl3 were added after five minutes, and 400 µL of 1 M NaOH were added after five more minutes. The mixture was incubated for 15 min, and absorbance was measured at 510 nm. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mg of catechin equivalents (CE) g−1 DW.

2.4.3. Total Antioxidant Activity

The total antioxidant activity (TAA) of the extract was evaluated using the 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline) 6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) radical scavenging assay following the method reported in Beleggia and coworkers [17]. To produce the ABTS radical cation, A 7 mM ABTS solution was reacted with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate, and the combination was incubated for 16 h at room temperature in the dark. Prior to the assay, the ABTS radical solution was diluted with ethanol to obtain an absorbance of 0.8 at 734 nm. A volume of 100 µL of methanolic extract diluted 1:5 was mixed with 4.9 mL of diluted ABTS radical solution. Absorbance was measured at 734 nm after incubation for 30 min at room temperature. All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as μmol of Trolox equivalents (TE) g−1 DW.

2.5. Determination of Plant Height and Inflorescence Biomass

For each replicate, ten plants were randomly collected and analyzed for plant height from 14 May until 21 August (harvest). Plant height was measured as the distance from the plant base to the top of the main inflorescence. As regards the measurement of fresh and dry biomass, the ten inflorescences collected for chemical analyses were weighed immediately after harvesting and after drying.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p ≤ 0.05) was used to assess significant differences among mean values using JMP software version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The online platform MetaboAnalyst 6.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca, accessed on 10 September 2025) was used for correlation and multivariate analysis. Prior to analysis, all data were autoscaled using mean centering and standard deviation normalization.

3. Results and Discussion

The inflorescences of hemp plants treated with MeJ solutions at 0, 1, 10, and 100 μM were analyzed for their (i) cannabinoid and terpene content determined by GC/MS, (ii) phenolic compound, carotenoid, and tocopherol content determined by HPLC, and (iii) TPC, TFC, and TAA determined spectrophotometrically. A total of 42 compounds were detected, which included 5 cannabinoids, 24 terpenes, 4 flavonoids, 4 phenolic acids, 2 carotenoids, and 3 tocopherols. For each class of phytochemicals, the total content was obtained from the sum of the individual compounds detected for that class. Additionally, the effect of MeJ treatments on hemp plant height and biomass accumulation in the inflorescences was assessed.

3.1. The Phytochemical Content and the Total Antioxidant Activity of Hemp Inflorescences

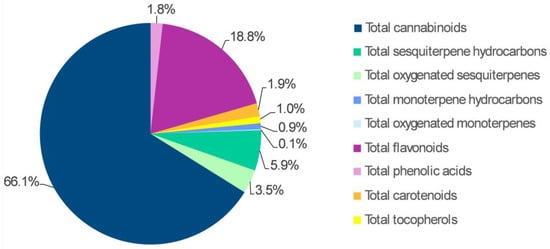

With regard to the average abundance of the different classes of phytochemicals in hemp inflorescences, cannabinoids were the most abundant class, representing 66.1% of all metabolites detected (Figure 1). The average content for this class ranged between 19,455.65 and 21,681.85 μg g−1 DW (Figure 2), with CBD accounting for 97% of the total cannabinoids (18,937.55–20,938.05 μg g−1 DW), and THC being well below the legal limit of 0.3% (283.86–381.84 μg g−1 DW) (Table 1). As said above, these features are unique to chemotype III cultivars like Codimono [3] and make them suitable for health purposes due to the therapeutic potential of CBD and the lack of psychoactive effects from THC [28].

Figure 1.

Average abundance of the different phytochemical classes in the inflorescences of hemp plants from the cv. Codimono. The percentage of each metabolite class was calculated relative to the total sum of all the metabolite classes.

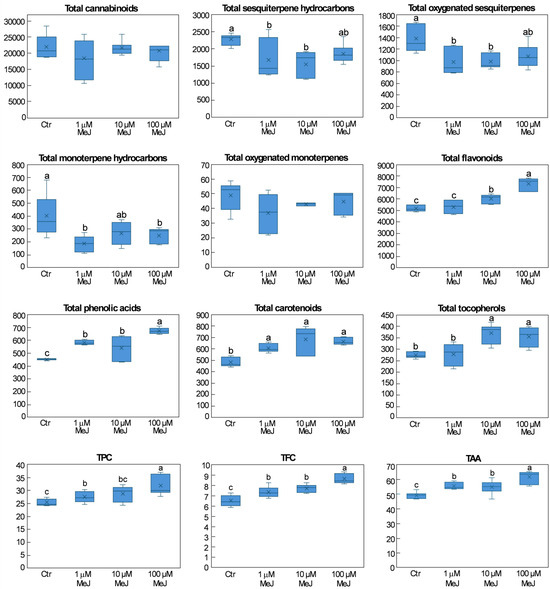

Figure 2.

Box plots of the different metabolite classes detected in the inflorescences of hemp plants from the cv. Codimono treated with different MeJ concentrations. Metabolite class contents were expressed as μg g−1 dry weight (DW), TPC was expressed as mg ferulic acid equivalents g−1 DW, TFC was expressed as mg catechin equivalents g−1 DW, and the TAA was expressed as μmol Trolox equivalents g−1 DW. For each metabolite class, different lowercase letters represent significant differences among treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1.

Terpenes and cannabinoids detected by GC/MS in the inflorescences of hemp plants from the cv. Codimono treated with different MeJ concentrations.

Flavonoids were the second most represented class of phytochemicals with levels ranging between 5186.13 and 7380.46 μg g−1 DW (Figure 2), which accounted for 18.8% of total metabolites detected (Figure 1). Within this class, orientin, vitexin, and isovitexin were present at high levels (1317.28–2996.86 μg g−1 DW) (Table 2). This result is in line with previous studies that identified these three compounds as the most abundant flavonoids in hemp inflorescences [17,29] and assessed their role as valuable markers in discriminating CBD-dominant from THC-dominant cultivars [30].

Table 2.

Phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and tocopherols detected by HPLC in the inflorescences of hemp plants from the cv. Codimono treated with different MeJ concentrations.

Regarding terpene compounds, total sesquiterpenes in their hydrocarbon and oxygenated form accounted for 5.9% and 3.5% of the metabolites detected, respectively (Figure 1), with values ranging between 1611.28 and 2258.01 μg g−1 DW and 966.79 and 1364.29 μg g−1 DW, respectively (Figure 2). The most abundant sesquiterpene hydrocarbons were β-caryophyllene and α-humulene (433.70–762.30 and 484.95–733.19 μg g−1 DW, respectively), which together accounted for 59% of this class of metabolites (Table 1), while α-bisabolol, which showed levels ranging from 348.35 to 578.34 μg g−1 DW (Table 1), represented 40% of the oxygenated sesquiterpenes. Total hydrocarbon and oxygenated monoterpenes ranged from 180.72 to 396.16 μg g−1 DW and from 36.94 to 47.59 μg g−1 DW, respectively, together accounting for 1% of the metabolites detected (Figure 1). Within these classes, the most abundant metabolites were α-pinene and β-myrcene, which accounted for 78% of total monoterpene hydrocarbons, with values of 80.79–204.59 and 48.48–122.76 μg g−1 DW, respectively (Table 1). These results are in line with previous studies, which detected β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, α-bisabolol, α-pinene, and β-myrcene as key components in the terpene profile of hemp inflorescences from almost all cultivars [31], capable of conferring a typical aroma bouquet, characterized by earthy, woody, fruity, and spicy odor notes [32]. Additionally, like orientin, vitexin, and isovitexin, α-bisabolol, α-pinene, and β-myrcene were found to be more abundant in chemotype III than in chemotype I and were therefore identified as compounds able to discriminate CBD-dominant from THC-dominant cultivars; however, due to the higher volatility of monoterpenes, only the more stable α-bisabolol was considered a reliable chemotypic marker [30].

Total phenolic acids, total carotenoids, and total tocopherols each represented 1.0–1.9% of all metabolites detected (Figure 1), with levels ranging from 275.36 to 688.51 μg g−1 DW (Figure 2). p-Hydroxybenzoic and ferulic acids (154.29–172.32 and 166.98–338.87 μg g−1 DW, respectively) represented 73% of the phenolic acids detected, lutein was more abundant than β-carotene (309.40–448.27 vs. 172.47–240.24 μg g−1 DW), and α-tocopherol significantly exceeded the other isomers (225.96–320.34 vs. 1.45–60.73 μg g−1 DW), accounting for 83% of the entire class of tocopherols (Table 2). The latter feature distinguished the inflorescences from hemp seeds, where γ-tocopherol was the predominant isomer [33,34].

According to the spectrophotometric measurements, TPC was between 25.49 and 31.89 mg FE g−1 DW, while TFC was between 6.55 and 8.69 mg CE g−1 DW (Figure 2). The correlation of TPC and TFC with the HPLC results, evaluated through Pearson’s correlation coefficient, revealed a strong positive correlation between TPC and the total phenolic content (given by the sum of total phenolic acids and total flavonoids) (r = 0.7226, p = 0.008) and between TFC and total flavonoid content (r = 0.8309, p = 0.0008). This result is not unique and has already been reported in previous studies carried out on both hemp [17,35] and other plant species [36], and testifies to the reliability of these spectrophotometric assays as a very useful simple tool to estimate the total phenolic content and the total flavonoid content in hemp inflorescences, especially when working with numerous samples, as in breeding programs or screenings for the identification of phenolic-rich cultivars intended for industrial uses.

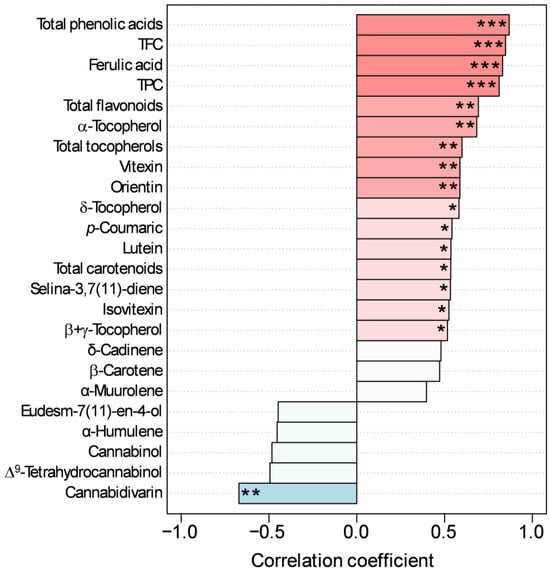

TAA, evaluated as scavenging activity of the ABTS radical, ranged between 49.18 and 61.90 μmol TE g−1 DW (Figure 2). Correlation analysis revealed that TAA was strongly positively correlated with total phenolic acids, ferulic acid, TPC, and TFC (Figure 3). A highly positive correlation was also observed with total flavonoids, total tocopherols, α-tocopherol, vitexin, and orientin, while a moderate positive correlation was detected with δ-tocopherol, p-coumaric acid, lutein, total carotenoids, selina-3,7(11)-diene, isovitexin, and β + γ-tocopherol (Figure 3). TAA was also negatively correlated with cannabidivarin (Figure 3). These results confirmed our previous findings on the same cultivar, which highlighted a high positive correlation between TAA evaluated through the ABTS assay and TPC, TFC, and phytochemicals belonging to the classes of phenolic compounds and tocopherols, especially vitexin, orientin, and α-tocopherols [17]. Other hemp cultivars have also shown a dominant role as antioxidants for these classes of compounds [11]. This is in line with the well-established antioxidant role of these compounds. Due to the presence of hydroxyl groups, phenolic compounds function well in aqueous environments by donating hydrogen atoms or electrons to stabilize reactive oxygen species, while the lipid-soluble tocopherols use hydrogen donation to quench lipid peroxyl radicals. Both neutralize free radicals, thereby protecting plant cells from oxidative damage [37]. Regarding the negative correlation of TAA with some cannabinoids, especially cannabidivarin, this does not necessarily mean that they are pro-oxidants per se, but rather that in the composition of the analyzed extract, a decrease in these cannabinoids occurs together with an increase in TAA linked to the increase in other dominant antioxidants such as phenolic compounds and tocopherols (see Section 3.2). Collectively, these findings contribute to the growing body of literature demonstrating the antioxidant potential of hemp inflorescences [11,38,39,40], a key factor underlying the health-promoting properties associated with their rich phytochemical composition.

Figure 3.

Pearson’s correlations using pattern search of the top 25 metabolites with the total antioxidant activity. Pink bars represent positive correlations, while blue bars represent negative correlations. *, **, and *** are significant at 0.1, 0.05, and 0.001 levels, respectively.

Although the composition of the phytochemical profile and the predominance of specific compounds resembled those reported in our earlier studies on the same cultivar [14,17], notable differences in the concentrations of individual compounds were observed. This is not surprising, as our previous study demonstrated that genotype, environment, and their interaction all influence phytochemical levels in hemp inflorescences, with environmental factors playing the most significant role [14].

3.2. Effect of MeJ Treatments on the Phytochemical Content and the Total Antioxidant Activity of Hemp Inflorescences

As shown in Figure 2, the total cannabinoid content was not significantly affected by MeJ treatments. This was because the accumulation of CBD, the most abundant of cannabinoids, did not change in MeJ-treated plants (Table 1). By contrast, cannabidivarin levels decreased by an average of 46% across all three MeJ treatments, while THC, CBG, and cannabinol levels decreased by 26–44% following 1 μM MeJ treatment; a 39% decrease in cannabinol level was also observed following 100 μM MeJ treatment (Table 1). To date, the information available on the effect of MeJ on cannabinoid accumulation is limited and contradictory. Hahm and coworkers [23] observed that CBD and THC levels in the inflorescences increased following treatment with 100 µM MeJ, whereas higher concentrations (200 and 400 µM) had no effect. Testone and coworkers [24], on the other hand, reported that CBD and THC levels increased significantly at 10 mM MeJ but not at 1 mM MeJ. Overall, these findings, together with those of the present study, suggest that the elicitation effects of exogenously applied MeJ depend not only on the elicitor concentration but may also be influenced by environmental conditions or genotype. Noteworthy is the ability of the 1 µM MeJ treatment to reduce THC levels while maintaining high CBD levels, an attractive outcome when seeking the specific therapeutic benefits of CBD without the psychotropic effects of THC, as in the production of full-spectrum CBD products (e.g., oils, capsules, topicals).

Compared to control plants, a decrease in the levels of both total non-oxygenated and oxygenated sesquiterpenes was observed in plants treated with 1 and 10 μM MeJ, which ranged between 23% and 29% (Figure 2). Consistently, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, aromadendrene, and cubenene levels decreased on average by 43%, 32%, 26%, and 27%, respectively, following 1 and 10 μM MeJ treatments (Table 1). A 24% and 30% decrease in β-caryophyllene and α-humulene levels, respectively, was also observed following 100 μM MeJ treatment, which also induced a 25–57% increase in δ-cadinene, α-muurolene, and seline-3,7(11)-diene levels compared to the other treatments (Table 1). As regards oxygenated sesquiterpenes, MeJ treatments determined a 20–40% decrease in the levels of selina-6-en-4-ol, α-bisabolol, and eudesm-7(11)-en-4-ol compared to the control, while a 31% decrease in the level of trans-longipinocarveol was observed only in plants treated with 1 μM MeJ (Table 1). MeJ treatments also negatively affected the levels of total monoterpene hydrocarbons, resulting in a 30–54% decrease compared to the control (Figure 2). This was consistent with the 32–61% decrease in α-pinene, β-pinene, and β-myrcene levels induced by MeJ treatments (Table 1). By contrast, the limonene level showed the opposite trend, increasing by 65% in the 1 μM MeJ treatment and by 20–35% in the other two treatments (Table 1). These findings are in contrast with those obtained by Testone and coworkers [24], who observed an increase in total terpene content of 51.8% and 69.7% in plants treated with 1 mM and 10 mM MeJ, respectively. As previously hypothesized for cannabinoids, the observed differences could be due to the different field trial conditions and genotypes employed or could be ascribable to the lower concentration of MeJ used in the current investigation compared to the previous one.

Regarding total flavonoid content, plants treated with 10 μM MeJ showed a 16% increase, while a 42% increase was observed in plants treated with 100 μM MeJ compared to control plants (Figure 2). Consistently, orientin, vitexin, and isovitexin levels were positively affected by 100 μM MeJ treatment, with increases ranging from 36% to 52%, while 10 μM MeJ treatment increased vitexin, isovitexin levels on average by 21%, and epicatechin levels by 58% (Table 2). Vitexin level also increased by 13% in plants treated with 1 μM MeJ (Table 2). The level of total phenolic acids also varied significantly under MeJ treatments, increasing on average by 24% at 1 and 10 μM MeJ and by 50% at 100 μM MeJ compared to the control (Figure 2). This was mainly due to the levels of ferulic acid, which increased on average by 48% in the first two treatments and by 103% in the third (Table 2). Although the differences were not statistically significant due to high variability among replicates, increases of 41–56% and 29–39% in the levels of caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid, respectively, were observed following MeJ treatments (Table 2).

All MeJ treatments positively affected total carotenoid content, with increases of 26% at 1 μM MeJ and 41% at 10 and 100 μM MeJ compared to the control (Figure 2). This was due to lutein and β-carotene levels, which were 33% and 15% higher, respectively, in plants treated with 1 μM MeJ, and 44% and 35% higher, respectively, in those treated with 10 and 100 μM MeJ (Table 2). Treatments with 10 and 100 μM MeJ also determined a 33% increase in total tocopherol levels (Figure 2). This was due to the increase in α-tocopherol level, which, following these two treatments, reached values that were, on average, 36% higher than the control (Table 2). Treatment with 100 μM MeJ also resulted in significant variations in δ-tocopherol and β + γ-tocopherol levels, which increased by 81% and 27%, respectively (Table 2).

TPC increased by 13% and 25% following 10 and 100 μM MeJ treatment, respectively, while TFC increased on average by 15% in 1 and 10 μM MeJ treatments and by 33% in 100 μM MeJ treatment (Figure 2). A positive effect of MeJ was also observed on TAA, which increased by 13% in plants treated with 1 and 10 μM MeJ and by 26% in those treated with 100 μM MeJ (Figure 2). The MeJ-induced increase in TPC and TFC was expected, given their positive correlation with the total phenolic compounds and the total flavonoids detected by HPLC, respectively. Similarly, the increase observed in TAA was mainly due to the increase in those phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and tocopherols that were found to be positively correlated with TAA (see Figure 3).

As said above, this is the first evidence demonstrating that MeJ-based treatments can induce the accumulation of flavonoids, phenolic acids, carotenoids, and tocopherols in hemp inflorescences. It is well known that phenolic compounds have beneficial effects on human health, particularly in the prevention and management of certain chronic diseases [41]. Regarding hemp, evidence exists that phenolic-rich extracts obtained from the inflorescences are effective in inhibiting the activity of neurodegenerative enzymes, such as acetylcholinesterase and monoaminooxidase A [42], as well as the growth of pathogenic bacterial, fungal, and dermatophyte species commonly associated with ulcerative colitis [43] and prostatitis [44]. Carotenoids and tocopherols are the two most abundant fat-soluble antioxidants in plants and, like phenolic compounds, protect against free radical damage and reduce the risk for various chronic diseases [45,46]. It is also known that phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and tocopherols can interact with each other to produce synergistic effects that can amplify their antioxidant properties [47]. Therefore, it is feasible that the suppression of terpene accumulation by MeJ represents a resource allocation trade-off determined by a pathway-specific MeJ signaling. MeJ can redirect metabolic flux from terpenoid biosynthesis toward the biosynthesis of antioxidant compounds that are directly involved in oxidative stress mitigation. Similar differential regulation of secondary metabolite classes has already been observed in other medicinal plants [48] and demonstrates how MeJ can yield secondary pathways priority over others in accordance with external stimuli.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

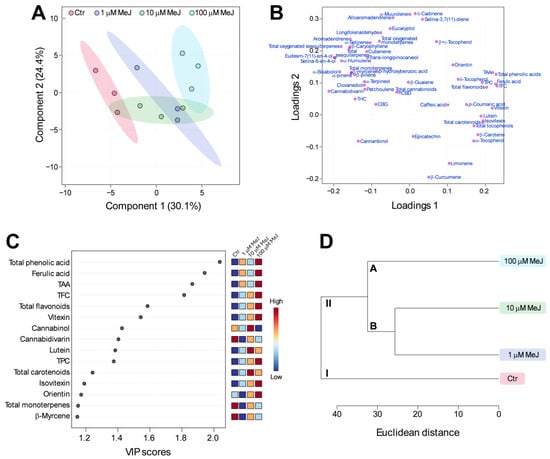

To identify significant metabolites differentiating control from MeJ treatments, multivariate analysis was carried out on the entire dataset (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 4A, the partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) score plot showed a clear separation between treatments. The differences were evident mainly in the Component 1 direction, with control positioned on the negative side of the Component 1 axis and MeJ treatments positioned on the positive side (Figure 4A). The greatest separation was observed between control and 100 μM MeJ treatment, followed by 1 and 10 μM MeJ treatments, which partially overlapped with each other (Figure 4A). Consistent with the distribution of metabolites observed in the different treatments, TPC, TFC, TAA, total phenolic compounds, total carotenoids, total tocopherols, and individual metabolites belonging to these classes were located on the right side of the loadings plot, while total cannabinoids, total terpenes, and individual cannabinoids and terpenes were located on the left side (Figure 4B). Moving on to the variable importance in projection (VIP) score plot (Figure 4C), it highlighted the top fifteen significant metabolites having VIP values greater than one, which indicated that these metabolites were the top contributors in the separation of treatments [49]. High-VIP metabolites included total phenolic acids, flavonoids, and carotenoids, ferulic acid, vitexin, isovitexin, orientin, lutein, and TAA, which, as already shown by ANOVA, were present at the highest levels in the 100 μM MeJ treatment and at the lowest levels in the control. The list of high-VIP metabolites also included the less abundant cannabinol, cannabidivarin, total monoterpenes, and β-myrcene, which instead showed the highest levels in the control (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Multivariate analysis of the entire dataset discriminating among the four treatments. (A) Partial least-squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) score plot in which the 95% confidence regions are displayed. (B) PLS-DA loadings plot showing how the variables are distributed on the two principal component axes. (C) PLS-DA variable importance in projection (VIP) score plot ranking the fifteen variables that are most significant in the separation among the four treatments. (D) Hierarchical clustering dendrogram showing the distance among treatments.

The hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) (Figure 4D) confirmed the grouping of treatments that emerged from the PLS-DA. In particular, two clusters were distinguished: cluster I, which comprised control, and cluster II, which included all three MeJ treatments. Cluster II was further subdivided into two subclusters: sub-cluster A, which included the 100 μM MeJ treatment, and sub-cluster B, which included the 1 and 10 μM MeJ treatments. Overall, the ANOVA combined with the multivariate analysis demonstrated that, under our experimental conditions, 100 μM MeJ represented the most effective dose for enhancing the total content of phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and tocopherol, as well as the TAA, without greatly affecting the levels of CBD or terpenes, the nutraceutical value of hemp inflorescences, and the functional quality of hemp-derived products.

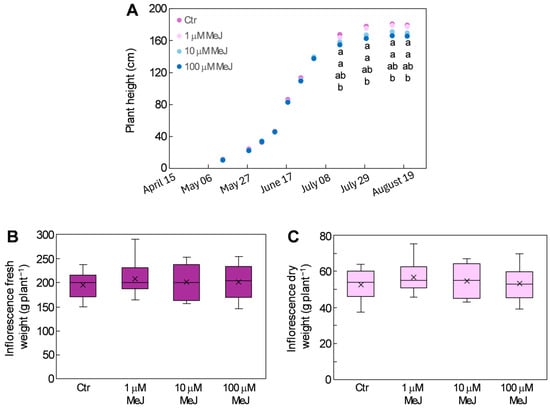

3.4. Effect of MeJ Treatments on Plant Growth and Inflorescence Biomass

Compared to control plants, MeJ-treated plants only slightly decreased in height over the course of treatment; the decrease was significant only in plants treated with 100 μM MeJ, where it did not exceed 8% (Figure 5A). A slight but not significant increase in fresh and dry weight of the inflorescences was observed in MeJ-treated plants compared to the control, which ranged from 3.3% to 6.9% for fresh weight (Figure 5B) and from 1.8% and 8.2% for dry weight (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Plant height (A), fresh biomass (B), and dry biomass (C) in the inflorescences of hemp plants from the cv. Codimono treated with different concentrations of MeJ. In (A), different lowercase letters in the same column represent significant differences among treatments (Tukey’s test p ≤ 0.05).

Evidence exists that jasmonate at high concentration can inhibit plant growth to promote defense responses [25,50]. This was also observed on cannabis plants, where treatments with 1–15 mM MeJ enhanced cannabinoid production but resulted in reduced plant height and lower aboveground biomass accumulation [51]. A similar effect was also observed in hemp plants treated with 200 and 400 μM MeJ, while treating the same plants with 100 μM MeJ proved more effective in inducing cannabinoid accumulation without impairing their growth [23]. The latter results are consistent with those obtained in the present study, in which the low concentrations of MeJ used stimulated the secondary metabolism of hemp plants without compromising their development. The finding that MeJ treatments did not affect inflorescence biomass is particularly noteworthy, as it implies higher yields of the phytochemicals whose concentrations were enhanced by MeJ.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, it emerged that the exogenous application of small doses of MeJ to hemp plants represents a useful strategy to improve the phytochemical properties of hemp inflorescences. In particular, our results identified 100 μM MeJ as the optimal dose among those tested, as it increased the content of phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and tocopherols, while maintaining plant growth, as well as CBD and terpene content, at levels comparable to the control. As a result, the inflorescences of plants treated with 100 μM MeJ could represent a suitable raw material for a variety of industrial end-uses, serving as a source of bioactive compounds, as well as biomass and fiber. Elicitation induced by signaling molecules such as MeJ is a widely demonstrated phenomenon. Therefore, it is likely that the increases in phytochemical accumulation observed in the cv. Codimono could also be induced, albeit to varying degrees, in other hemp cultivars, making our findings more generalizable. To verify this, further studies are needed on different genotypes and in different environments, including both open field and controlled conditions. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that, in addition to enhancing the phytochemical yields, using MeJ in hemp plant cultivation may help control pests and diseases and increase the resistance to abiotic stresses of this valuable crop. In line with the principle of “Circular Economy,” our findings innovatively support the hemp supply chain, suggesting industrial applications for hemp inflorescences that could contribute to increasing the economic value of this crop by transforming potential waste into high-quality byproducts with promising applications in the food, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and cosmetic sectors. This will lessen waste pollution and pave the way for novel health-promoting products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T.; Investigation, R.B., V.G., V.M. and S.S.; Data curation, R.B., V.G., V.M. and S.S.; Formal analysis, R.B. and D.T.; Writing—original draft, D.T.; Writing—review and editing, R.B., V.M. and D.T.; Funding acquisition, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FESR) (within the PON “R&I” 2017–2020—Axis 2—Action II—OS 1.b) under the “UNIHEMP” research project “Use of Industrial Hemp Biomass for Energy and New Biochemical Production” (Prot. n. 2016 of 27 July 2018, CUP B76C18000520005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Vito de Gregorio for his technical assistance in the management of the field trial.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Crocq, M.A. History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandolino, G.; Carboni, A. Potential of marker-assisted selection in hemp genetic improvement. Euphytica 2004, 140, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, D.; Miselli, F.; Carboni, A.; Moschella, A.; Mandolino, G. Time course of cannabinoid accumulation and chemotype development during the growth of Cannabis sativa L. Euphytica 2008, 160, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visković, J.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Sikora, V.; Noller, J.; Latković, D.; Ocamb, C.M.; Koren, A. Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) agronomy and utilization: A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, C.M.; Hausman, J.F.; Guerriero, G. Cannabis sativa: The plant of the thousand and one molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Arellano, J.; Canseco-Alba, A.; Cutler, S.J.; León, F. The polypharmacological effects of cannabidiol. Molecules 2023, 28, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachnani, R.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Vrana, K.E. The pharmacological case for cannabigerol. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2021, 376, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuutinen, T. Medicinal properties of terpenes found in Cannabis sativa and Humulus lupulus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 157, 198–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanuš, L.O.; Hod, Y. Terpenes/terpenoids in Cannabis: Are they important? Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2020, 3, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollastro, F.; Minassi, A.; Fresu, L.G. Cannabis phenolics and their bioactivities. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 1160–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- André, A.; Leupin, M.; Kneubühl, M.; Pedan, V.; Chetschik, I. Evolution of the polyphenol and terpene content, antioxidant activity and plant morphology of eight different fiber-type cultivars of Cannabis sativa L. cultivated at three sowing densities. Plants 2020, 9, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milay, L.; Berman, P.; Shapira, A.; Guberman, O.; Meiri, D. Metabolic profiling of Cannabis secondary metabolites for evaluation of optimal postharvest storage conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 583605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spano, M.; Di Matteo, G.; Ingallina, C.; Botta, B.; Quaglio, D.; Ghirga, F.; Balducci, S.; Cammarone, S.; Campiglia, E.; Giusti, A.M.; et al. A multimethodological characterization of Cannabis sativa L. inflorescences from seven dioecious cultivars grown in Italy: The effect of different harvesting stages. Molecules 2021, 26, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleggia, R.; Menga, V.; Fulvio, F.; Fares, C.; Trono, D. Effect of genotype, year, and their interaction on the accumulation of bioactive compounds and the antioxidant activity in industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) inflorescences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trono, D. Elicitation as a tool to improve the accumulation of secondary metabolites in Cannabis sativa. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 3119–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasińska-Jakubas, M.; Hawrylak-Nowak, B. Protective, biostimulating, and eliciting effects of chitosan and its derivatives on crop plants. Molecules 2022, 27, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beleggia, R.; Iannucci, A.; Menga, V.; Quitadamo, F.; Suriano, S.; Citti, C.; Pecchioni, N.; Trono, D. Impact of chitosan-based foliar application on the phytochemical content and the antioxidant activity in hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) inflorescences. Plants 2023, 12, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasternack, C.; Hause, B. Jasmonates: Biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot. 2013, 111, 1021–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasri, R.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Karthick, K.; Shin, H.; Choi, S.H.; Ramesh, M. Methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid as powerful elicitors for enhancing the production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants: An updated review. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 153, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutimanukul, P.; Thongtip, A.; Panya, A.; Phonsatta, N.; Thangvichien, S.; Mosaleeyanon, K.; Wanichananan, P.; Sae-Tang, W.; Chutimanukul, P. Enhancing the biochemical potential of holy basil through methyl jasmonate elicitation with insights into physiological responses in a plant factory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianersi, F.; Amin Azarm, D.; Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Poczai, P. Change in secondary metabolites and expression pattern of key rosmarinic acid related genes in Iranian lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) ecotypes using methyl jasmonate treatments. Molecules 2022, 27, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Ma, C.; Qi, D.; Lv, H.; Yang, T.; Peng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Z. Transcriptional responses and flavor volatiles biosynthesis in methyl jasmonate-treated tea leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahm, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, K.; Park, J. Optimization of cannabinoid production in hemp through methyl jasmonate application in a vertical farming system. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testone, G.; Douguè Kentsop, R.A.; Giannino, D.; da Silva Linge, C.; Galasso, I.; Genga, A.; Delledonne, A.; Biffani, S.; Roda, G.; Frugis, G.; et al. Effects of methyl jasmonate and chitosan nanoparticle treatments on field-grown hemp inflorescences: Integrating transcriptomic and secondary metabolite insights. Ind. Crop Prod. 2025, 235, 121749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.-I.; Pandian, S.; Rakkammal, K.; Largia, M.J.V.; Thamilarasan, S.K.; Balaji, S.; Zoclanclounon, Y.A.B.; Shilpha, J.; Ramesh, M. Jasmonates in plant growth and development and elicitation of secondary metabolites: An updated overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 942789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishchenko, S.; Mokher, J.; Laiko, I.; Burbulis, N.; Kyrychenko, H.; Dudukova, S. Phenological growth stages of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Codification and description according to the BBCH scale. Žemės Ūkio Moksl. 2017, 24, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicignano, M.; Beleggia, R.; del Piano, L.; Enotrio, T.; Suriano, S.; Raimo, F.; Trono, D. Effect of combining organic and inorganic fertilizers on the growth of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) plants and the accumulation of phytochemicals in their inflorescences. Plants 2025, 14, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinen, Z.J.; Mohan, R.; Premadasa, L.S.; Acharya, A.; Mohan, M.; Byrareddy, S.N. Therapeutic potential of cannabis: A comprehensive review of current and future applications. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Dai, K.; Xie, Z.; Chen, J. Secondary metabolites profiled in cannabis inflorescences, leaves, stem barks, and roots for medicinal purposes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Henry, P.; Shan, J.; Chen, J. Identification of chemotypic markers in three chemotype categories of cannabis using secondary metabolites profiled in inflorescences, leaves, stem bark, and roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, E.M.; Brown, P.N.; Murch, S.J. The terroir of Cannabis: Terpene metabolomics as a tool to understand Cannabis sativa selections. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, K.P.; Hoeng, J.; Lach-Falcone, K.; Goffman, F.; Schlage, W.K.; Latino, D. Exploring aroma and flavor diversity in Cannabis sativa L.—A review of scientific developments and applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, I.; Russo, R.; Mapelli, S.; Ponzoni, E.; Brambilla, I.M.; Battelli, G.; Reggiani, R. Variability in seed traits in a collection of Cannabis sativa L. genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irakli, M.; Tsaliki, E.; Kalivas, A.; Kleisiaris, F.; Sarrou, E.; Cook, C.M. Effect of genotype and growing year on the nutritional, phytochemical, and antioxidant properties of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, L.; Castaldo, L.; Narváez, A.; Graziani, G.; Gaspari, A.; Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y.; Ritieni, A. Analysis of phenolic compounds in commercial Cannabis sativa L. inflorescences using UHPLC-Q-orbitrap HRMS. Molecules 2020, 25, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, A.; Bunea, C.I.; Mocan, A. Total flavonoid content revised: An overview of past, present, and future determinations in phytochemical analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2025, 700, 115794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülçin, İ. Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spano, M.; Di Matteo, G.; Ingallina, C.; Sobolev, A.P.; Giusti, A.M.; Vinci, G.; Cammarone, S.; Tortora, C.; Lamelza, L.; Prencipe, S.A.; et al. Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) inflorescences as novel food: The effect of different agronomical practices on chemical profile. Foods 2022, 11, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, P.W.; Poudineh, Z.; Shearer, M.; Taylor, N.; MacPherson, S.; Raghavan, V.; Orsat, V.; Lefsrud, M. Relationship between total antioxidant capacity, cannabinoids and terpenoids in hops and cannabis. Plants 2023, 12, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascrizzi, R.; Flamini, G.; Rossi, A.; Santini, A.; Angelini, L.G.; Tavarini, S. Inflorescence yield, essential oil composition and antioxidant activity of Cannabis sativa L. cv ‘Futura 75’ in a multilocation and on-farm study. Agriculture 2024, 14, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The role of polyphenols in human health and food systems: A mini-review. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cásedas, G.; Moliner, C.; Maggi, F.; Mazzara, E.; López, V. Evaluation of two different Cannabis sativa L. extracts as antioxidant and neuroprotective agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1009868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, C.; Recinella, L.; Ronci, M.; Menghini, L.; Brunetti, L.; Chiavaroli, A.; Leone, S.; Di Iorio, L.; Carradori, S.; Tirillini, B.; et al. Multiple pharmacognostic characterization on hemp commercial cultivars: Focus on inflorescence water extract activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Simone, S.C.; Libero, M.L.; Pulcini, R.; Nilofar, N.; Chiavaroli, A.; Tunali, F.; Angelini, P.; Angeles Flores, G.; Venanzoni, R.; Cusumano, G.; et al. Phytochemical profiling and biological evaluation of the residues from industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) inflorescences trimming: Focus on water extract. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; de Camargo, A.C. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in common and emerging dietary sources: Occurrence, applications, and health benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, P.; Faienza, M.F.; Naeem, M.Y.; Corbo, F.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Muraglia, M. Overview of the potential beneficial effects of carotenoids on consumer health and well-being. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibsted, L.H. Vitamin and non-vitamin antioxidants and their interaction in food. J. Food Drug Anal. 2012, 20, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, J.; Xiao, Y. The methyl jasmonate-inducible and tissue-specific transcription factor MhbHLH87 promotes monoterpenoid biosynthesis while inhibiting phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in Mentha haplocalyx. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarachantachote, N.; Chadcham, S.; Saithanu, K. Cutoff threshold of variable importance in projection for variable selection. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2014, 94, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewedy, O.A.; Elsheery, N.I.; Karkour, A.; Elhamouly, N.; Arafa, R.; Mahmoud, G.; Dawood, M.; Hussein, W.; Mansour, A.; Amin, D.; et al. Jasmonic acid regulates plant development and orchestrates stress response during tough times. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 208, 105260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, M.T.; Deseo, M.A.; O’Brien, M.; Clifton, J.; Bacic, A.; Doblin, M.S. Metabolomic analysis of methyl jasmonate treatment on phytocannabinoid production in Cannabis sativa. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.