Abstract

A field trial was conducted at two locations in northern Ghana over two successive years to determine the optimal insecticide application timings for mitigating non-lepidopteran pest infestations in a cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) variety, Songotra-T. This variety was genetically engineered to resist damage by the Maruca pod borer (MPB) (Maruca vitrata Fab.; Lepidoptera: Crambidae). A split-plot design, with cowpea variety as the main plot factor (Songotra-T vs. Songotra) and insecticide spraying regimes as the sub-plot, was used. Spraying treatments ranged from no spray to three applications at key growth stages (50% flowering, pod initiation, and 50% podding). Data were collected on pest infestation, pod damage, and grain yield. An economic analysis of the spraying regimes tested was performed using yield data. Significant spraying regime effects were observed for non-lepidopteran pests such as whiteflies (p = 0.034), thrips (p = 0.006) and the pod-sucking bugs complex (p < 0.05). Variety effects were mainly significant for MPB infestation and damage to pods. Songotra-T consistently produced approximately 2-fold higher yields than Songotra. Among spraying regimes, two applications at pod initiation and 50% podding resulted in the highest yields, while additional sprays offered no significant advantage. This spraying regime also resulted in a higher return on investment. These findings demonstrate that the adoption of Songotra-T mitigates excessive insecticide use in cowpea production.

1. Introduction

Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp.) is an important leguminous crop cultivated worldwide [1,2,3]. It plays a vital role in the lives of millions across Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and other developing countries [4]. Cowpea is drought tolerant and can thrive in low-fertility soils [1]. Early-maturing varieties supply food before the main harvest season of other crops [5]. Cowpea serves as a cheap and common source of dietary protein for many people [1]. Additionally, it contributes to soil fertility improvement [4] and helps suppress weed growth [3].

Approximately 14.5 million hectares of land are used for cowpea cultivation each year, resulting in a total production of 6.2 million tonnes of grains annually [6]. Global cowpea production is growing at an annual rate of 5%, with 3.5% arising from an increase in cultivated area and 1.5% from a rise in yield [7]. The expansion of land area contributes by around 70% to the overall growth. Africa alone accounts for about 84% of the cowpea produced globally, with countries in West Africa alone contributing to over 80% of Africa’s cowpea output [8].

However, cowpea grain production in Africa is far below the achievable yield reported in other major cowpea-producing countries worldwide. This is due to factors such as disease, low soil fertility, drought, inadequate planting systems, insect pests and lack of inputs [3]. In SSA, insect pests are the number one constraint to cowpea grain production [4,9,10]. Key insect pests that affect cowpea on the field include Maruca pod borer (MPB) (Maruca vitrata Fab.), whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci Genn.), leafhoppers (Empoasca sp.), mites (Tetranychus spp.), thrips (Megalurothrips sjostedti Try.), Ootheca sp., pod-sucking bugs (PSB) complex (Clavigralla tomentosicollis Stall., Anoplocnemis curvipes Fab., Riptortus dentipes Fab., Mirperus spp., and Nezara viridula Linn.) and aphids (Aphis craccivora Koch.). These generally cause low yield and sometimes complete crop failure [10,11,12]. According to Abudulai et al. [13], insect pests that attack flowers and pods are the most damaging in cowpea cultivation.

Until recently, most cowpea breeding programmes have focused on grain yield and seed quality [14,15,16]. However, due to the enormity of yield losses caused by insect pest infestation in cowpea production, breeding programmes are now concentrating on developing varieties with in-built resistance to major insect pests of cowpea [4]. This is because the use of resistant cowpea varieties offers a sustainable alternative for pest control compared to chemical methods where at least eight rounds of insecticide sprays are applied to mitigate pest infestations [10]. However, resistant varieties are only effective against one or a few insect pests, and relying solely on them is insufficient for satisfactory control [13]. For instance, the MPB (M. vitrata) is the most cosmopolitan of all cowpea insect pests, damaging flowers, developing pods, and seeds [9,10]. To effectively tackle the damaging effects of this pest, cowpea was genetically engineered to produce the transgenic event AAT-7Ø9AA-4 using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. This resulted in the introduction of the Cry 1Ab gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain HD-1 [17]. This cowpea event and its progeny (derived by introgressing the Cry 1Ab gene from AAT-7Ø9AA-4 into the commercial cowpea variety called Songotra (IT97K-499-35)) express the Cry 1Ab protein and are reported to be effective at mitigating MPB damage [18,19]. Commercially available cowpea varieties in Ghana and Nigeria containing the Cry 1Ab gene are Songotra-T and Sampea 20-T, respectively [19]. The Songotra-T variety was commercially launched in Ghana in July 2024 with eight (8) seed companies initially engaged to uptake certified seed production in that year. Many cowpea farmers across the major growing regions purchased seeds of this variety for cultivation in the 2025 growing season. Also, there is a continued effort to strengthen the seed production and distribution system for this variety to ensure unrestricted seed access by the last mile farmer.

The Cry 1Ab protein expressed in the Songotra-T variety is target specific and does not mitigate damage by non-lepidopteran pests of cowpea, such as thrips and the PSB complex [19,20]. Hence, there is a need to holistically and sustainably control infestation and damage by non-lepidopteran pests to protect yield. Field trials were therefore conducted in two successive years and across two locations to identify the appropriate times of insecticide applications to mitigate non-lepidopteran pest infestations and damage in Songotra-T and to determine the insecticide spraying regime that offers the best financial return to growers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Locations

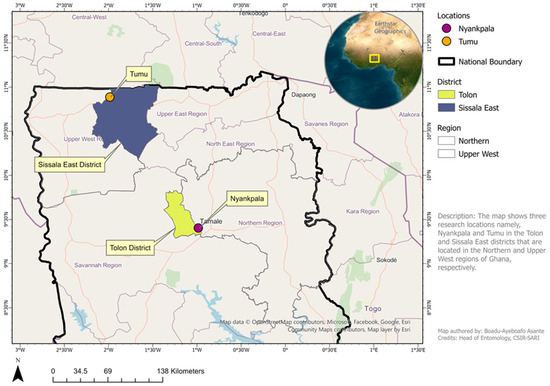

A field trial was conducted during the 2023 and 2024 wet seasons at two locations in northern Ghana to identify the optimum number of insecticide sprays required to protect a transgenic cowpea variety, Songotra-T, from non-lepidopteran arthropod pests. The trial locations were Nyankpala and Tumu in the northern and upper west regions, respectively (Figure 1). The ecology of both trial locations is the Guinea Savannah zone, which is characterized by a unimodal rainfall pattern which commences in May and ends in October, followed by a dry season from November to April of each year. The mean annual daily temperatures during the growing season range between 20 °C and 35 °C, while the mean precipitation ranges between 900 and 1200 mm annually. The soils at Nyankpala and Tumu are generally the Savannah Ochrosol type, with a relatively thin layer of topsoil (about 25 cm deep) consisting of greyish brown sandy loam [21].

Figure 1.

Map of northern Ghana showing locations where the trial was conducted in 2023 and 2024 growing seasons (Credit: Asante Boadu-Ayeboafo, CSIR-SARI, Nyankpala).

The trial sites at both locations were tractor ploughed and harrowed to obtain good soil tilth. In both seasons, planting was performed in the first week of August.

2.2. Test Materials

The genetically engineered commercial cowpea variety, Songotra-T, and its parental line, Songotra (IT97K-499-35), were used for this study. The IT97K-499-35 was developed by the International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (IITA), Ibadan, Nigeria, and, through joint testing across the sub-region, it was released in Ghana by CSIR-Savanna Agricultural Research (CSIR-SARI) as Songotra in 2008. In contrast, Songotra-T was developed and released by CSIR-SARI in 2024. Both varieties thrive well in the Sahel, Sudan, and Guinea Savannah zones of northern Ghana. They have a maturity period ranging between 62 and 65 days after planting and their yield potential is 2.5 t/ha. The main distinguishing features of the two varieties is that Songotra-T is genetically engineered to resist damage by the MPB while Songotra is highly susceptible to this insect pest. Also, although not relevant for this study, Songotra-T is resistant to the charcoal rot disease (Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi)) while Songotra is susceptible [19,22,23].

2.3. Trial Establishment, Treatments, and Experiment Design

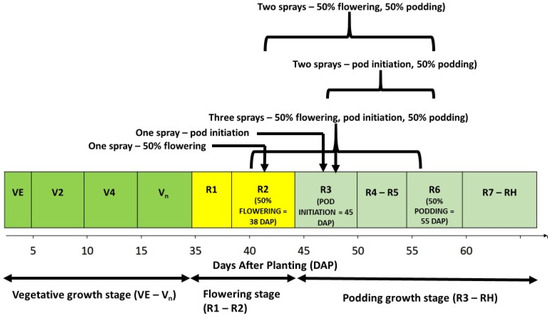

The two cowpea varieties (Songotra and Songotra-T) and the six insecticide spraying regimes [no spray, once at 50% flowering (≈38 days after planting (DAP)), once at pod initiation (≈45 DAP), twice at 50% flowering (≈38 DAP) and 50% podding (≈55 DAP), twice at pod initiation (≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (≈55 DAP), and thrice at 50% flowering (≈38 DAP), pod initiation (≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (≈55 DAP); see Figure 2) were arranged in a split-plot experimental design. The main plot treatments were the varieties, while the sub-plots contained the insecticide spraying regimes. Each sub-plot occupied an area of 7.5 m2 and there were four rows of cowpea in the plots; each row had a length of 5 m. In contrast, the main plots occupied an area of 82.5 m2 each. The standard planting distance of 50 cm between rows and 20 cm between plants was used for this trial. The sub-plots were separated by 1.5 m wide alleys, while main plots were 2 m apart. There were four blocks of treatments combinations, and the blocks were separated by 3 m wide alleys.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the cowpea growth stages at which the insecticide spraying regimes tested were applied. Note: VE = seedling emergence; V2 = second trifoliolate leaf unfolded at node 4; V4 = fourth trifoliolate leaf unfolded at node 6 + branching; R1 = one open flower on the plant; R2 = 50–100% of flowers are open; R3 = one pod at maximum length; R4 = 50% of pods at maximum length; R5 = one pod with fully developed seeds; R6 = 50% of pods with fully developed seeds; R7 = one pod at mature colour; and RH = 80% pods at mature colour (harvest maturity).

Insect pests that cause economic damage in cowpea cultivation are those that attack the crop at the flowering and podding growth stages [13]. Hence, the insecticide application timings used in this study were selected to target infestations at these critical growth stages of cowpea (Figure 2).

After planting, the herbicide, Alligator 400 EC (Pendimentalin, 400 g a.i. L−1) (Kumark Company, Kumasi, Ghana), was applied to the fields at each location to suppress weed growth using a CP-15 knapsack sprayer (Agri-gem Ltd., Saxilby, UK). This was followed by a single hand weeding at 4 weeks after planting and before canopy closure. Fertilizers were not applied to the trial fields.

The insecticide, K-Optimal (Lambda-Cyhalothrin 15 g/L + Acetamiprid 20 g/L) (Kumark Company, Kumasi, Ghana), was used for pest management according to the different spraying regimes tested. It was applied at a rate of 0.5 L/ha using a CP-15 knapsack sprayer.

2.4. Data Collection

Pest infestation data were collected at vegetative, flowering, and podding stages. At the vegetative growth stage, a 38 cm diameter sweep net was used to sample whiteflies (B. tabaci) and leafhoppers (Empoasca spp.) at 21 days DAP following the standard operating procedures for sweeping [24]. Briefly, this involved walking along two diagonals in each plot and sweeping in a 180° arc from left to right. This was followed by transferring the content of the net into previously labelled collection vials containing 70% ethanol. The contents of the vials were sorted in the laboratory and the numbers of each species of flying insects were counted and recorded. At 90% flowering (≈43 DAP), 20 flowers were randomly collected from each plot and placed in vials containing 70% ethanol. The number of MPB (M. vitrata) larvae and thrips (M. sjostedti) present in the flowers were later counted in the laboratory and recorded. Infestation by PSBs (C. tomentosicollis, A. curvipes, R. dentipes, and N. viridula) were assessed at 50% (≈55 DAP) and 90% podding (≈60 DAP). This involved counting the number of different PSBs nymphs and adults in a 1 m stretch of the inner rows in each plot.

Damage to pods by PSBs and MPB was assessed at 90% podding. The PSB damage assessments were conducted by randomly selecting ten plants from the inner rows of each plot and counting the number of pods present. The number of PSB-damaged pods was recorded and expressed as a percentage of the total number of pods counted. Key distinguishing features such as the shriveling of pods or the presence of feeding punctures were used to identify PSB-damaged pods prior to counting [25]. Similarly, the pods on the selected plants were assessed for MPB damage and the number of MPB-damaged pods were expressed as a percentage of the total number of pods counted. The MPB-damaged pods were distinguished by the presence of larval entry holes in the pods which were plugged with webbed frass [26].

Grain yield was assessed at maturity. The pods of all plants in the two inner rows of each plot were harvested, sun-dried, followed by threshing and winnowing to separate the grains from the chaff. The grain yield in each plot was weighed and converted to kilogram per hectare for analysis.

2.5. Data Analysis

The insect count data from each of the two years were subjected to square root transformation to ensure the homogeneity of their variances. This was followed by conducting an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for split-plot design using the GenStat® statistical programme (12th edition, version 1, VSN Inernational Ltd., Hertfordshire, HP1 1ES, UK. www.vsni.co.uk) for insect count data and all the parameters measured for each location in each year. In these analyses, variety was used as the main plot factor and spraying regime was the sub-plot treatment. Afterwards, a combined-years ANOVA, using the treatment means from each season and for each variable, was performed. In these analyses, year was used as the blocking factor, variety as the main plot, and spraying regimes as sub-plot factors. Whenever year effects were significant, the means from each year were presented separately. Also, whenever there was significant location effect for any variable, the data were presently separately for each location. Mean separations were undertaken using Tukey’s HSD test at 5% probability threshold.

2.6. Partial Budget Analysis

To assess the net benefit due to the spraying regimes tested and the returns on non-lepidopteran pest management in the cowpea variety, Songotra-T, a partial budget analysis was performed. This assessed the economic viability of investment in non-lepidopteran pest control in Songotra-T compared to no protection. The market prices of both cowpea and the insecticides were used in order to arrive at the value of production and cost of production, respectively. It was assumed that all other costs were constant and the costs that vary were therefore used to calculate the input cost. The value of increased yields due to insecticide applications were calculated using the following:

where was the value of increased yield due to spraying (USD), was the market price of cowpea (USD), was the output of treated plot (kg/ha), and was the output of unprotected Songotra (kg/ha).

The total variable cost of insecticide application was calculated as follows:

where was the total variable cost (USD), is the market price of insecticides used, is the volume of insecticide used (l ha−1), and the labour cost for insecticide applications (USD/ha).

The net benefit was calculated using the following:

where was the value of increased yield due to spraying and is total variable cost of insecticides and its application.

The returns to spraying were then calculated using the following:

3. Results

3.1. Vegetative Stage Pests

The key vegetative stage pest recorded in this study were whiteflies (B. tabaci) and leafhoppers (Empoasca spp.). In a combined-years ANOVA for the mean whitefly infestation, there was no significant difference between years for this insect (p = 0.136). There was, however, a significant location effect for whitefly infestation (p < 0.001). Of the two locations studied, infestation was greater in Tumu (18.46 flies per sweep) than in Nyankpala (5.86 flies per sweep). At Nyanlpala, the mean whitefly infestation was significantly affected by the spraying regime (p = 0.034) only. There were no significant variety (p = 0.891) and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.671) effects. Among the spraying regimes tested, infestation was highest in the cowpea that was sprayed thrice and lowest in those sprayed once (pod initiation) (Table 1), although the differences found were very small and may not be biologically relevant.

Table 1.

Effect of insecticide spraying regime on mean whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, infestation in cowpea in northern Ghana.

In contrast, whitefly infestation did not significantly affect variety (p = 0.835), spraying regime (p = 0.094), and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.782) at Tumu. The mean whitefly infestation at this location was 18.46 flies per sweep.

There was no significant year effect (p = 0.077) when leafhopper infestation data from the two years and locations were combined and analyzed. There was, however, a significant location effect (p < 0.001) for leafhopper infestations. Infestation was higher in Tumu (20.25 leafhoppers per sweep) than in Nyankpala (14.56 leafhoppers per sweep). In Nyankpala, the mean leafhopper infestation was not significantly affected by variety (p = 0.684), spraying regime (p = 0.812) or their interactions (p = 0.988) (Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant variety (p = 0.178), spraying regime (p = 0.402), and variety × spraying regime interactions (p = 0.713) effect for leafhopper infestation at Tumu (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of variety and insecticide spraying regimes on the mean leafhopper (Empoasca spp.) infestation in cowpea in northern Ghana.

3.2. Flowering and Podding Stage Pests

There was no significant year effect (p = 0.268) when data on thrips were subjected to a combined-years and location ANOVA. The trial locations, however, significantly affected thrips infestation (p = 0.009). This variable was significantly higher in flowers collected in Nyankpala (45.41 thrips per 20 flowers) than in Tumu (29.20 thrips per 20 flowers). In Nyankpala, infestation was not significantly affected by variety (p = 0.644), spraying regime (p = 0.524), and variety × spraying regime (p = 0.805). However, there was a significant spraying regime (p = 0.006) effect for thrips infestation at Tumu. Infestation was highest in cowpea sprayed twice (i.e., pod initiation, 50% podding) and lowest in those sprayed thrice (50% flowering, pod initiation, 50% podding) (Table 3). There was no significant variety (p = 0.081) and variety × spraying regime (p = 0.412) interaction effect for this variable at Tumu (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of insecticide spraying regime on the mean number of thrips per 20 flowers sampled at two locations in northern Ghana.

For MPB infestation in flowers, there was no significant year (p = 0.500) effect when the data from the two years were combined and analyzed. There was, however, a significant location effect for this variable (p = 0.028). Infestation was higher in Tumu (8.41 MPB per 20 flowers) than in Nyankpala (5.54 MPB per 20 flowers). In both Nyankpala and Tumu, infestation was significantly affected by variety only, with the larvae of the insect recorded in the flowers of Songotra only (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of cowpea varieties and spraying regimes on the mean number of Maruca pod borer (MPB) and pod-sucking bugs (PSB) complex infestations at two locations in northern Ghana.

There was no significant year (p = 0.171) effect when PSB complex infestation data from the two seasons and locations were combined and analyzed. There was, however, a significant location effect (p < 0.001) for this variable. Of the two locations studied, infestation was higher in Nyankpala (21.97 PSB/m) than in Tumu (18.54 PSB/m). In Nyankpala, PSB infestation was significantly affected by spraying regime (p < 0.001) only. There were no significant variety (p = 0.391) and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.753) effects for this pest complex. Among the spraying regimes tested, infestation was highest in the unprotected cowpeas and lowest in those sprayed thrice. There was no significant difference between the latter and cowpeas sprayed twice (pod initiation, 50% podding) (Table 4).

Similarly, PSB infestation in Tumu was significantly affected by spraying regime (p < 0.001) only. There were no significant variety (p = 0.286) and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.486) effects for this variable. Of the spraying regimes tested, infestation was highest in unprotected cowpea and lowest in those sprayed thrice (Table 4).

3.3. Pod Damage

A combined-years ANOVA showed significant year effect for damage to pods by PSB (p = 0.020). This variable was higher in 2023 (34.18%) than in 2024 (25.21%). In 2023, PSB damage to pods was not significantly different between the test locations (p = 0.411). Also. this variable was not significantly affected by variety (p = 0.688) and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.070) effects. There was, however, a significant spraying regime effect for percentage of PSB-damaged pods (p < 0.001). Among the spraying regimes, pod damage was highest in the unprotected cowpeas and lowest in those sprayed twice (pod initiation, 50% podding). Damage in the latter was not significantly different from that recorded in those sprayed thrice (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of insecticide spraying regime on the mean damage to cowpea pods (%) by pod-sucking bugs complex during the 2023 and 2024 growing seasons in northern Ghana.

Again, pod damage by PSB was not significantly different between the trial locations (p = 0.571) in 2024. There was no significant variety (p = 0.743) and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.062) effect for this variable. The spraying regimes tested, however, significantly affected (p < 0.001) the percent of PSB-damaged pods. Among the spraying regimes tested, the damage was highest in cowpea sprayed once at 50% flowering and lowest in those sprayed thrice. There was no significant difference between the latter and those sprayed twice at pod initiation and 50% flowering (Table 5).

There was no significant year effect when the percent of MPB-damaged pods data from the two years were combined and analyzed (p = 0.500). The test locations, however, differed in terms of the damage to pods by this insect (p = 0.009). The damage was higher in Tumu (14.14%) than in Nyankpala (11.68%). In Nyankpala, the percent MPB-damaged pods were significantly affected by variety (p = 0.013) and spraying regime (p = 0.015). Of the two varieties tested, damage was recorded in Songotra only. Among the spraying regimes, the damage was highest in the unprotected cowpea and lowest in those sprayed thrice (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effect of variety and insecticide spraying regimes on the mean Maruca pod borer (MPB)-damaged pods (%) at two locations in northern Ghana.

In Tumu, the number of MPB-damaged pods was significantly affected by variety only (p = 0.009). Again, damage to pods by MPB was recorded in only Songotra. There was no significant spraying regime (p = 0.082) and variety × spraying regime interaction (p = 0.082) (Table 6).

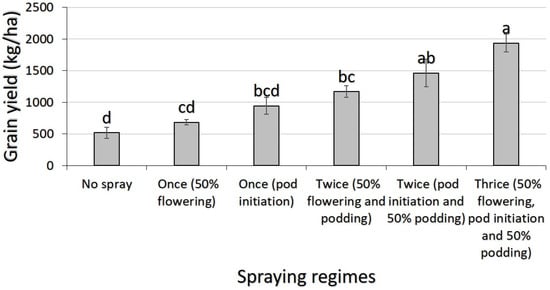

3.4. Grain Yield (Kg/ha)

A combined-years ANOVA for grain yield data showed significant year effect (p = 0.047). Yield was higher in 2023 (1120 kg/ha) than in 2024 (1086 kg/ha). In 2023, yield was not significantly affected by the trial locations (p = 0.696). There was, however, a significant variety (p = 0.015) and spraying regime effect (p < 0.001) for this variable. Of the varieties tested, yield was higher in Songotra-T (1506.6 ± 97.85 kg/ha) than in Songotra (732.93 ± 57.18 kg/ha). Among the spraying regimes, yield was highest in cowpea sprayed thrice and lowest in the unprotected ones. There was no significant difference between the yield of cowpea sprayed thrice and those sprayed twice (i.e., pod initiation, 50% flowering) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of insecticide spraying regime on the mean grain yield of cowpea during the 2023 growing season in northern Ghana. Note: Bars followed by different letters are significantly different at 5% probability threshold; data are means ± standard error of means.

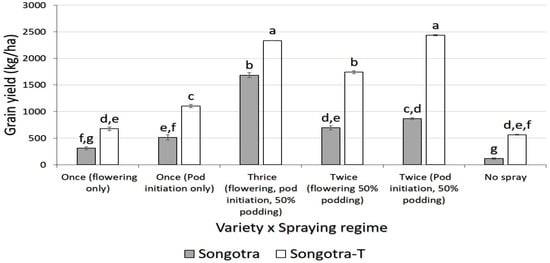

In 2024, yield was not significantly affected by trial location (p = 0.747). There were, however, a significant variety (p = 0.029), spraying regime (p < 0.001), and variety × spraying regime interaction (p < 0.001) effects. In general, Songotra-T sprayed twice at pod initiation and 50% podding recorded the highest yield, while unprotected Songotra was the lowest. There was no significant difference between the former and Songotra-T sprayed thrice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Interaction effect of variety and insecticide spraying regimes on the mean cowpea grain yield (kg/ha) during the 2024 growing season. Note: Bars followed by different letters are significantly different at 5% probability threshold; bars are means ± standard error of means.

3.5. Partial Budget Analyses of Spraying Regimes Tested

A partial budget analysis conducted to identify the spraying regime with the best returns on investment showed a positive value of increased yield for all the spraying regimes tested compared to the untreated controls in both Songotra and Songotra-T. Overall, the net benefit due to the spraying regimes was positive and these net benefits increased with increases in the number of rounds of insecticide applications.

For the Songotra variety, the net returns on investment due to spraying (i.e., benefit: cost ratio) was highest in those sprayed thrice. For every USD 1.00 invested in this spraying regime in Songotra, there was a USD24.37 return on investment. In contrast, the spraying regime with the highest return on investment for Songotra-T was spraying once at pod initiation or twice (pod initiation, 50% podding). For every USD 1.00 invested in spraying Songotra-T once at pod initiation, there was a USD 57.71 return, while for spraying the same variety twice (pod initiation, 50% podding), there was a USD 57.49 return on investment.

In general, there was approximately a 2-fold increase in returns on investment for all spraying regimes applied to Songotra-T compared to the same spraying regime applied to Songotra. When an average of ten rounds of insecticide sprays used by resourceful farmers was assessed for its return on investment, the results showed that those excess sprays did not increase financial returns even if it increased yields (Table 7).

Table 7.

Partial budget analysis for the effect of insecticide spraying regimes on non-lepidopteran pest management in a genetically modified cowpea variety, Songotra-T, and its non-transgenic counterpart, Songotra.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pre-Flowering Pests

The major pre-flowering growth stage arthropod pests of cowpeas in the tropics include whiteflies, leafhoppers, and aphids. However, the economic importance of aphids is seasonal [12,27,28,29]. In this study, whiteflies and leafhoppers infested the two varieties tested across locations and seasons. This corroborates the findings of an earlier study, which reported a lack of significant difference between cowpea genetically modified to express the Cry 1Ab insecticidal protein and its conventional counterparts, in terms of whitefly and leafhopper infestations [19]. To date, synthetic insecticide applications remain the most widely used mitigatory strategy for whiteflies, in spite of the evolution of resistant biotypes [29]. The insecticide spraying regimes tested in this work significantly affected whitefly infestation in only Tumu. However, a closer examination of the data shows that this significance was driven by the high numbers of this pest recorded in cowpeas sprayed thrice (i.e., at 50% flowering (≈38 DAP), pod initiation (≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (≈55 DAP)) and the very low numbers recorded in those sprayed once at pod initiation. Since no insecticide was applied during the vegetative growth stage where sampling for this pest was undertaken, insecticide use could not have accounted for the observed differences. Again, since there was no insecticide application at the vegetative growth stage, leafhopper infestation was uniform across the spraying regimes.

As expected, there was no significant difference between the varieties for infestation by thrips because the Cry 1Ab insecticidal protein expressed by Songotra-T is not active against non-lepidopteran pests [30]. In contrast, spraying regimes that had an insecticide application at 50% flowering recorded significantly lower number of thrips per 20 flowers sampled. Earlier studies [13,31,32] also reported significant reductions in thrips counts when cowpeas were protected with insecticides at the flowering stage. It was, however, generally observed that irrespective of the years and trial locations, thrips infestation levels were below the economic threshold of seven thrips per flower [33]. This indicates that thrips infestation severity in the trial locations does not warrant incurring cost on their management.

4.2. Post-Flowering Pests

Assessments of the flowers for MPB infestation showed that larvae of this pest were present in only the conventional Songotra. This is consistent with the results of an earlier study, which reported that Songotra-T is resistant to infestation and damage by MPB [19]. However, MPB infestation of flowers was not significantly affected by the spraying regimes. This contrasts the findings of Kusi et al. [32] who reported that a single round of insecticide spray applied at the flowering stage effectively mitigates MPB infestation and damage in cowpea. In both trial locations, MPB-damaged pods were affected by variety with damage recorded in Songotra only. The lack of damage to pods of Songotra-T was because of the expression of the Cry 1Ab insecticide protein in its pods which confers it with resistance to this pest [18,19,34,35]. It was only at Nyankpala that the spraying regime influenced damage to pods by MPB, with unprotected cowpeas recording significantly higher damage. Insecticide applications to control MPB is the most widely used option, although this approach does not offer complete suppression of MPB populations in susceptible varieties [36].

The pod-sucking bugs (PSB) complex constitutes another major group of pests that impacts the yield and quality of cowpea [12]. Here, the varieties tested were not resistant to PSB infestation. Cowpeas that are susceptible to PSB infestation are protected from this pest during the podding stage using various management options, with insecticide use considered the most effective [10,37]. However, judicious use of insecticides is key in reducing the negative consequences of pesticide applications [10]. Protecting cowpea with insecticide sprays during the podding stage led to reduced PSB infestation in the tropics [32,38]. Here, targeted applications of insecticide at pod initiation (i.e., ≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (i.e., ≈55 DAP) were identified to be effective in mitigating PSB infestations in cowpea. Since the tested varieties were not genetically resistant to PSB infestation, damage to pods was not significantly different between Songotra and Songotra-T. In both planting years, the timing of insecticide application significantly affected damage caused by PSB infestation. Many studies [13,39,40], confirm the effectiveness of insecticide applications in reducing PSB damage to cowpea pods. In the current work, spraying regimes that targeted the pod initiation (i.e., ≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (i.e., ≈55 DAP) growth stages offered the best protection against this pest complex.

4.3. Grain Yield and Economic Assessment

Grain yield was higher in Songotra-T compared to the conventional variety in both years. This was because Songotra-T was developed to resist in-season MPB infestations that typically limit flowering and cause damage to pods [18,19]. Insecticide applications were found to generally lead to increased grain yield. Some studies suggest that a single round of insecticide application at 50% podding is sufficient to control PSB damage, and this consequently increases grain yields [31,41,42]. In this study, targeted application of insecticide at the pod initiation (i.e., ≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (i.e., ≈55 DAP) growth stages was found to better protect yields. Perhaps this was because of the lethal effects of the insecticide on the PSB complex that attacks and damage the crop at this growth stage. Feeding damage from this pest complex can cause up to 70% yield losses if young developing cowpea pods and mature green pods are not adequately protected [38].

Overall, the current study identified a maximum of two rounds of insecticide applications (i.e., at pod initiation and 50% flowering) as sufficient for protecting the yields of Songotra-T. In contrast, at least three rounds of spray were needed to guarantee some appreciable amount of yield in the conventional Songotra. The in-built resistance to MPB in Songotra-T and the below economic threshold thrips infestation explains the lack of a need to apply insecticides at the flowering stage against the key floral pests [18,19,33]. Thus, limiting insecticide use to the podding stage prevented PSB damage to pods, resulting in better yields. In contrast, the conventional Songotra required additional insecticide protection during flowering to mitigate the damaging effects of thrips and MPB before yields could increase. This explains the higher number of rounds of insecticide applications needed in the conventional variety.

Cowpea cultivation is generally reported to be profitable even when cost of production is increased by increasing the number of rounds of insecticide applications [19]. In this study, two rounds of insecticides sprays targeting pod initiation and 50% podding resulted in the highest return on investment for Songotra-T. Increasing the number of sprays beyond the recommended two did not increase yields to a level that positively impacted on the returns on investment for this variety. For the conventional Songotra, the profits increased with an increase in number of insecticide sprays, suggesting that more than three rounds of insecticide spray applications are required in this variety to attain the minimum profits obtained by growers of Songotra-T. However, when we tested the financial returns to growers who spray up to ten rounds of insecticides, our economic analysis showed a low return on investment even if these excess insecticide applications increased yields to the maximum levels attained in Songotra-T. This low return on investment was mainly attributed to the high cost of insecticides and labour. Considering the negative consequences of insecticides on human health and the environment [43], excessive application of insecticides because of the need to increase yields is not a sustainable agricultural practice. Hence, growing an MPB-resistant variety such as Songotra-T increases profits while safeguarding the environment and human health.

5. Conclusions

Cowpea farmers cultivating conventional cowpea varieties in SSA typically apply 8–12 rounds of insecticide sprays in order to protect their yields from insect pests. In the present study we have demonstrated that the number of rounds of insecticide applications in cowpea can be reduced to two well-timed applications when varieties engineered to resist MPB infestation and damage are cultivated. This is particularly relevant in locations where the population of thrips is below the economic threshold. The yields of MPB-resistant cowpeas such as Songorta-T are effectively protected when insecticide sprays are applied at pod initiation (i.e., ≈45 DAP) and 50% podding (i.e., ≈55 DAP) to target infestation and damage by the PSB complex. This ultimately results in double yields and higher financial returns on investments compared to the other spraying regimes tested. Hence, sustainably minimizing chemical input in cowpea cultivation without compromising on yield can be attained when farmers grow this engineered cowpea variety using this recommended spraying regime.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.N., G.A.A., P.A. and E.A.; methodology, J.A.N., G.A.A., E.A., P.A., M.Z., and J.M.B.; validation, J.M.B.; formal analysis, J.A.N., E.A., P.M.E., and J.M.B.; investigation, G.A.A., E.A., P.A., M.Z., J.Y.K., H.K.A., and T.K.T.; resources, J.A.N., G.A.A., and T.K.T.; data curation, P.A., J.Y.K., and H.K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.N., E.A., P.M.E., and J.M.B.; writing—review and editing, G.A.A., P.A., and M.Z.; supervision, J.Y.K., M.Z., and H.K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this paper are available upon written request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge technical staff at the Entomology Section, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR)—Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (SARI), especially Frederick Anaman, Mohammed Abdulai, Rebecca Kaba, and Suweiba Abdulai for their assistance in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Badiane, F.A.; Diouf, M.; Diouf, D. Cowpea. In Broadening the Genetic Base of Grain Legumes; Singh, M., Bisht, I., Dutta, M., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Lino-Neto, T.; Rosa, E.; Carnide, V. Cowpea: A legume crop for a challenging environment. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 4273–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebede, E.; Bekeko, Z. Expounding the production and importance of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) in Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1769805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timko, M.P.; Ehlers, J.D.; Roberts, P.A. Cowpea. In Pulses, Sugar and Tuber Crops. Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants; Kole, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsky, R.J.; Singh, B.B.; Oyewole, B. Contribution of early season cowpea to late season maize in the savanna zone of West Africa. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2001, 18, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. Cowpea: The Food Legume of the 21st Century; Crop Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Osipitan, O.A.; Fields, J.S.; Lo, S.; Cuvaca, I. Production systems and prospects of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) in the United States. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamara, A.Y.; Omoigui, L.O.; Kamai, N.; Ewansiha, S.U.; Ajeigbe, H.A. Improving cultivation of cowpea in West Africa. In Achieving Sustainable Cultivation of Grain Legumes; Burleigh Dodds Series in Agricultural Science; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-1786761408. Available online: http://oar.icrisat.org/id/eprint/10804 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Boukar, O.; Fatokun, C.A.; Roberts, P.A.; Abberton, M.; Huynh, B.L.; Close, T.J.; Kyei-Boahen, S.; Higgins, T.J.V.; Ehlers, J.D. Cowpea. In Grain Legumes (Handbook of Plant Breeding 10); De Ron, A.M., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 219–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusha, C.; Balikai, R.A.; Patil, R.H. Insect pest of cowpea and their management—A review. J. Exp. Zool. India 2016, 19, 635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Egho, E.O. Management of major field insect pests and yield of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) walp) under calendar and monitored application of synthetic chemicals in Asaba, southern Nigeria. Am. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2011, 2, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewale, R.O.; Bamaiyi, L.J. Management of cowpea insect pests. Sch. Acad. J. Biosci. 2013, 1, 217–226. Available online: http://irepo.futminna.edu.ng:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/4151 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Abudulai, M.; Kusi, F.; Seini, S.S.; Seidu, A.; Nboyine, J.A.; Larbi, A. Effects of planting date, cultivar and insecticide spray application for the management of insect pests of cowpea in northern Ghana. Crop Prot. 2017, 100, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukar, O.; Fatokun, C.A.; Huynh, B.L.; Roberts, P.A.; Close, T.J. Genomic tools in cowpea breeding programs: Status and perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, O.M.; Lawal, O.O.; Wahab, A.A.; Ibrahim, U.Y. Evaluation of advanced breeding lines of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L. Walp) for high seed yield under farmers’ field conditions. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Ochar, K.; Iwar, K.; Ha, B.K.; Kim, S.H. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) production, genetic resources and strategic breeding priorities for sustainable food security: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1562142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, T.J.; Gollasch, S.; Molvig, L.; Moore, A.; Popelka, C.; Watkins, P.; Armstrong, J.; Mahon, R.; Ehlers, J.; Huesing, J.; et al. Genetic transformation of cowpea for protection against bruchids and caterpillars. In Innovative Research Along the Cowpea Value Chain. In Proceedings of the Fifth World Cowpea Conference on Improving Livelihoods in the Cowpea Value Chain Through Advancement in Science, Saly, Senegal, 27 September–1 October 2010; pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Addae, P.C.; Ishiyaku, M.F.; Tignegre, J.B.; Ba, M.N.; Bationo, J.B.; Atokple, I.D.; Abudulai, M.; Dabiré-Binso, C.L.; Traore, F.; Saba, M.; et al. Efficacy of a cry1Ab gene for control of Maruca vitrata (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) in cowpea (Fabales: Fabaceae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nboyine, J.A.; Adazebra, G.A.; Owusu, E.Y.; Agrengsore, P.; Seidu, A.; Lamini, S.; Zakaria, M.; Kwabena, J.Y.; Ali, H.K.; Akaogu, I.; et al. Field Performance of a Genetically Modified Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) Expressing the Cry1Ab Insecticidal Protein Against the Legume Pod Borer Maruca vitrata. Agronomy 2024, 14, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Meissle, M.; Xue, J.; Zhang, N.; Ma, S.; Guo, A.; Liu, B.; Peng, Y.; Song, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Expression of Cry1Ab/2Aj Protein in Genetically Engineered Maize Plants and Its Transfer in the Arthropod Food Web. Plants 2023, 12, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adiku, S.G.; Dayananda, P.W.; Rose, C.W.; Dowuona, G.N. An analysis of the within-season rainfall characteristics and simulation of the daily rainfall in two savanna zones in Ghana. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1997, 86, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Variety Release & Registration Catalogue (GVRRC). Catalogue of Crop Varieties Released and Registered in Ghana; National Varietal Release and Registration Committee; Directorate of Crop Services, Ministry of Food and Agriculture: Accra, Ghana, 2019; 84p.

- Sodji, F.; Tengey, T.K.; Kwoseh, C.K. Identification of new sources of resistance to charcoal rot caused by Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) Goid in cowpea. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.F.; Goodell, P.B.; Baldwin, R.A.; Frate, C.A.; Godfrey, L.D.; Orloff, S.B.; Canevari, W.M.; Davis, R.M.; Getts, T.J.; Grettenberger, I.M.; et al. University of California (UC) IPM Pest Management Guidelines: Alfalfa; UC Agriculture and Natural Resources (ANR) Publication 3430: Davis, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/alfalfa/sampling-with-a-sweep-net/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Koona, P.; Osisanya, E.O.; Jackai, L.; Tonye, J. Infestation and damage by Clavigralla tomentosicollis and Anoplocnemis curvipes (Hemiptera: Coreidae) in cowpea plants with modified leaf structure and pods in different positions relative to the canopy. Environ. Entomol. 2004, 33, 471–476. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H.C.; Saxena, K.B.; Bhagwat, V.R. The Legume Pod Borer, Maruca vitrata: Bionomics and Management; International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics: Patancheru, India, 1999; Available online: http://oar.icrisat.org/id/eprint/6608 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Yadav, K.S.; Pandya, H.V.; Patel, S.M.; Patel, S.D.; Saiyad, M.M. Population dynamics of major insect pests of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.]. Int. J. Plant Prot. 2015, 8, 112–117. Available online: http://www.researchjournal.co.in/online/IJPP.htm (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Ranawat, Y.S.; Kumawat, K.C. Population dynamics of major insect pests of cowpea. J. Exp. Zool. India 2021, 24, 999. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, M.; Koul, B.; Chandrashekar, K.; Raut, A.; Yadav, D. Whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) management (WFM) strategies for sustainable agriculture: A review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, M.N.; Huesing, J.E.; Tamò, M.; Higgins, T.J.; Pittendrigh, B.R.; Murdock, L.L. An assessment of the risk of Bt-cowpea to non-target organisms in West Africa. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngakou, A.; Tamò, M.; Parh, I.A.; Nwaga, D.; Ntonifor, N.N.; Korie, S.; Nebane, C.L.N. Management of cowpea flower thrips, Megalurothrips sjostedti (Thysanoptera, Thripidae), in Cameroon. Crop Prot. 2008, 27, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi, F.; Nboyine, J.A.; Abudulai, M.; Seidu, A.; Agyare, Y.R.; Sugri, I.; Zakariaa, M.; Owusua, R.K.; Nutsugah, S.K.; Asamoah, L. Cultivar and insecticide spraying time effects on cowpea insect pests and grain yield in northern Ghana. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabirye, J.; Nampala, P.; Kyamanywa, S.; Ogenga-Latigo, M.W.; Wilson, H.; Adipala, E. Determination of damage-yield loss relationships and economic injury levels of flower thrips on cowpea in eastern Uganda. Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 911–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.S.; Ishiyaku, M.F.; Abdullahi, U.S.; Katung, M.D. Response of transgenic Bt cowpea lines and their hybrids under field conditions. J. Plant Breed. Crop Sci. 2014, 6, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothi, M.; Kumar, S.; Maravi, D.K.; Altosaar, I.; Kalia, V.; Sahoo, L. Transgenic Cowpea Expressing Synthetic Bt Cry1Ab Confers High Resistance to Legume Pod Borer (Maruca vitrata). bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiso, J.B.; Chemining’wa, G.N.; Olubayo, F.M.; Saha, H.M. Effects of variety and insecticide spray application on pest damage and yield of cowpea. Int. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 7, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Olufemi, O.P.; Odebiyi, J.A. The effect of intercropping with maize on the level of infestation and damage by pod-sucking bugs in cowpea. Crop Prot. 2001, 20, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyelu, O.L.; Akingbohungbe, A.E. Comparative assessment of feeding damage by pod-sucking bugs (Heteroptera: Coreoidea) associated with cowpea, Vigna unguiculata ssp. unguiculata in Nigeria. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2007, 97, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzubil, P.B.; Zakariah, M.; Alem, A. Integrating host plant resistance and chemical control in the management of cowpea pests. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2008, 2, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dzemo, W.D.; Niba, A.S.; Asiwe, J.A.N. Effects of insecticide spray application on insect pest infestation and yield of cowpea [Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.] in the Transkei, South Africa. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afun, J.V.K.; Jackai, L.E.N.; Hodgson, C.J. Calendar and monitored insecticide application for the control of cowpea pests. Crop Prot. 1991, 10, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghali, A.M. Insecticide application schedules to reduce grain yield losses caused by insects of cowpea in Nigeria. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 1992, 13, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F. Impacts of agricultural pesticides on terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Impacts Toxic Chem. 2011, 2011, 63–87. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.