Abstract

Seed vitality is a key factor for successful germination of seeds and successful root establishment of crops. However, a cold environment can severely hinder the germination of soybean seeds, resulting in a significant decrease in yield. In this study, the cold tolerance of 205 chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSL) during the germination process was evaluated. CSSL_R22 exhibited higher seed vitality under low-temperature conditions. Five quantitative trait loci (QTL) related to cold tolerance during the germination stage were detected. By combining the QTL analysis results with transcriptome data, we determined that GmKAN1 (Glyma.20G108600) is an important regulatory factor for cold tolerance during seed germination. Preliminary studies have shown that GmKAN1, as a transcriptional repressor of GmARF2 and GmARF8, can regulate auxin synthesis to enhance the tolerance of seeds to cold stress. These results provide valuable insights into the regulatory network related to cold tolerance during soybean seed germination.

1. Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max L.), an important grain and oilseed crop, originated in China and plays a vital role in global agriculture [1]. In response to increasing demand, extensive efforts have been made to enhance soybean yield [2,3]. Seed vigor, a complex agronomic trait, significantly influences plant establishment and yield [4,5]. Key parameters defining seed vigor include imbibition rate (IR), germination potential (GP), germination index (GI), and germination rate (GR) [6]. These factors collectively affect germination efficiency and uniform seedling establishment, ultimately contributing to improved stress resistance and productivity.

Seed vigor is influenced by multiple environmental and genetic factors, including seed storage conditions, moisture content, salinity, alkalinity, and low-temperature stress in the context of germination [7]. Cold stress adversely affects soybean germination by disrupting physiological metabolism and disease resistance, leading to reduced yield and quality [8]. Cold tolerance in plants is governed by various adaptive mechanisms, including alterations in membrane fatty acid composition, enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, accumulation of osmoprotectants, and expression of cold-responsive genes [9].

Existing studies have shown that the low-temperature response of soybeans is regulated by some related transcription factors. Under cold treatment, transcriptome analysis revealed many genes related to cold stress, including CBF/DREB [10]; GmTCF1a has a specific response to cold stress. Ectopic expression enhances cold resistance and upregulates the level of the cold-sensitive gene COR15a [11]. The GmMYB177 gene endows transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants with freeze tolerance, while GmMYB76 may play a partial role in freeze tolerance [12].

Soybean, known for its high protein and oil content, is particularly vulnerable to cold stress during germination [13]. Chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) serve as a powerful tool for identifying genetic loci associated with agronomically important traits. Previously, a CSSL population was developed by introgressing genomic segments from wild soybean ZYD00006 into the cultivated variety SN14 [14]. Mapping such precise loci in a heterogeneous genetic background is challenging. because each line carries a single or few defined chromosomal segments from a donor parent in the otherwise uniform genetic background of a recurrent parent. This design dramatically reduces genetic noise and enhances the detection power and mapping resolution for small-effect quantitative trait loci (QTLs). Cold tolerance of plants is a complex quantitative trait, which is jointly controlled by genetic factors, environmental conditions and their interactions. QTLs related to cold tolerance at the germination stage have been widely studied in various crops, including corn [15], rice [16,17], rapeseed [18], soybean [19], etc. Twelve QTLs related to low-temperature tolerance during the germination stage of soybeans identified by Jiang et al. in eight linkage groups of soybeans [20]; Zhang et al. further expanded their understanding of the cold tolerance of soybeans during the germination period by detecting 35 cold-tolerant QTLs in 17 linkage groups in backcrossed inbred line populations [21].

However, the precise genetic architecture and regulatory networks governing soybean seed germination under cold stress, particularly the tissue-specific transcriptional responses between cotyledons and plumules, remain poorly understood. Although QTL mapping can identify genomic regions, the key causal genes and their functional roles within these loci are often elusive. Furthermore, how these genes integrate into hormonal signaling pathways, such as auxin, to confer cold tolerance during germination is largely unexplored. In this study, CSSL_R22 was identified as a line exhibiting superior germination potential and germination index under low-temperature conditions. By integrating transcriptomic analysis, the molecular mechanisms underlying its cold tolerance were characterized. Aims to provide new insights into the genetic mechanism of low-temperature tolerance during soybean seed germination, enhance our understanding of the genetic structure of low-temperature tolerance during soybean germination, and accelerate the genetic improvement of low-temperature tolerance in soybeans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The CSSLs used in this study were developed in our laboratory using SN14 as the recurrent parent and wild soybean ZYD00006, which possesses hard seeds, as the donor parent. Individuals exhibiting the expected genomic recovery rate were self-crossed through multiple generations. The CSSL population included eight generations (BC3F8, BC3F9, BC3F10, BC4F7, BC4F8, BC4F9, BC5F7, and BC5F8). In 2019 and 2020, 205 CSSLs were cultivated at the Xiangyang Experimental Base of Northeast Agricultural University (45°45′ N, 126°38′ E). The total length of introgressed segments in the CSSLs was 5589.34 Mb, which was 5.71 times larger than the soybean genome and covered 89.65% of the genome of wild soybean. Resequencing of CSSLs (Parents) and division of Bin Markers; 580,524 SNPs were identified between SN14 and ZYD00006, which indicated that there were genetic differences between cultivated soybean SN14 and wild soybean ZYD00006. These SNPs in the parents of the CSSLs also facilitate further fine mapping of QTLs. The 580,524 SNP was divided into 3780 bin markers. The library was sequenced with an Illumina HiSeqTM sequencing platform, and the sequence read length was 150 bp [22]. The assay was conducted as three independent biological replicates, with each replicate consisting of 30 seeds (a total of 90 seeds were phenotyped per line). Plants were grown in rows 5 m in length, with 60 cm ridge spacing and 10 cm between plants. Seeds were harvested when fully mature in autumn. Field management followed the protocol detailed by Qi et al. [23].

2.2. Seed Vigor Assessment

Seeds were surface-sterilized using 10% (w/w) sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), rinsed twice with sterile water, and selected based on uniform size and absence of visible damage. The seeds were placed on filter paper in sterile Petri dishes and hydrated with 20 mL of sterile water. Seed vigor was assessed by calculating GI, GP, and GR using the following equations: GI = Σ(Gt/Dt), where Gt corresponds to the total number of germinated seeds on day t, while Dt corresponds to the time, in days, for Gt; GP = N3/N × 100%, where N3 denotes the number of germinated seeds on day 3 and N corresponds to total seeds; and GR = Nt/N × 100%, where Nt denotes the numbers of seeds germinated on day t and N indicates the total seeds [24]. Germinated seed numbers were assessed after rinsing to measure IR, GI, GP, and GR, each of which was calculated in triplicate. The low-temperature germination cultivation conditions are 10 °C, in the dark environment. The type of the light incubator is RXZ-380 produced by Ningbo Jiangnan Instrument Factory (Ningbo, China).

Indole-acetic acid treatment group samples: Prepare indoleacetic acid solution of the corresponding concentration, select soybean seeds of uniform size and no obvious damage, disinfect them and place them on filter paper in sterile culture dishes. Pour 25 mL of indoleacetic acid solution into each dish and soak the seeds at 4 °C for 12 h. Wash off the excess soaking solution and add sterilized water for conventional germination treatment. Repeat the treatment three times in each group. During the cultivation period, it is necessary to pay attention to replenishing water and keeping the filter paper moist. Indole acetic acid was prepared using water as the solvent; the final treatment concentration of 10 μM was determined based on the pre-experiment (Figure S6); 30 uniformly sized seeds were used for each biological replicate; in the germination experiment, a randomization procedure was adopted. The Petri dishes containing the seeds of all experimental groups and the control group were randomly placed in different positions within the same incubator.

2.3. QTL Mapping

To identify QTLs associated with seed vigor, a genetic linkage map was constructed using the CSSLs derived from SN14 and ZYD00006. The construction of chromosome fragment substitution lines in wild soybeans in the laboratory in the early stage. Zheng et al.’s research shows the genetic map density [22], with a total of 3780 blocks (Table S2). QTL mapping for GI, GP, and GR employed the ICIM-ADD model of ICIMapping 4.2 software. “PIN” = 0.001 (PIN: the largest-value for entering variables in stepwise regression of residual phenotype on marker variables), LOD value ≥ 2.5 [25,26,27].

2.4. High-Throughput Transcriptomic Sequencing and Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from three biological replicates of SN14 and R22 cotyledons and plumules under both normal and low-temperature conditions using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as directed by the manufacturer. Following RNA extraction, the integrity and purity of the samples were assessed. Messenger RNA was purified from 50 μg of total RNA and broken into fragments of ~300-base pair (bp) fragments. Libraries with different index sequences were mixed in equal proportions, and single-stranded libraries were generated through alkaline denaturation. Paired-end sequencing of all samples was conducted with an Illumina sequencer by Laso biology (Suzhou, China). Clean sequencing reads were mapped to the soybean reference genome for the quantification of gene expression. Percentages of Q30 bases in the raw data for these samples were all at least 98.04%. Reads containing adapter sequences at the 3′ end or exhibiting an average quality score below Q20 were removed. The final clean data, expressed as a percentage of total sequenced bases, ranged from 97.92% to 98.56%. The annotated soybean reference genome (Wm82.a4.v1) was obtained from Phytozome (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/info/Gmax_Wm82_a4_v1, accessed on 15 October 2024). RNA-seq and lipid metabolomic analyses were conducted by Lianchuan Biotechnology Institution (Hangzhou, China). Gene expression levels were quantified in FPKM. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between SN14 and R22 under normal and low-temperature conditions were identified using DESeq2 [28] based on a |log2FoldChange| > 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p < 0.05.

2.5. qPCR-Based Validation

To confirm the accuracy of the RNA sequencing results, total RNA was extracted from independent biological replicates and subjected to quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from each RNA sample using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The qPCR reactions were conducted in a 20-μL volume containing 1 μg of cDNA using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (Takara, Beijing, China) in a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System. The amplification conditions were: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. GmActin11 (GenBank No. TC204137) was utilized as the endogenous control when normalizing data. Cycle threshold (CT) values were computed with the Roche LightCycler 480 II software, and relative transcript levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Data are given as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent biological replicates, each analyzed in triplicate.

2.6. Endogenous Substance Measurement

In the analysis of endogenous substances, samples were taken from soybean seeds treated with 10 μM IAA for three days and untreated soybean seeds. The samples were ground in liquid nitrogen and 0.1 g of each sample was weighed for the determination of proline (Pro), water (H2O2), malondialdehyde (MDA), and the activities of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, and CAT). The reagents used for the determination of these endogenous substances were from Suzhou Greis Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Suzhou, China), and the calculation methods and enzyme activity units were in accordance with the instructions.

2.7. Dual-Luciferase Transcriptional Activity Assay

The transient expression detection of dual-luciferase was carried out in the following steps. To construct the LUC reporter vector, a DNA fragment of approximately 2 kb upstream of the ARF2/8 translation initiation site was amplified from the Williams 82 genomic DNA and homologous recombined into the pGreenII 0800-LUC vector. The CDS sequence of KAN1 was cloned from the cDNA of Williams 82 and constructed into the pGreenII-62SK vector. The Agrobacterium GV3101 (pSoup) strain carrying recombinant plasmids was infected into the leaves of the tobacco plant of Bens’. After 48 h of growth, imaging was performed using the fully automatic chemiluminescence image analysis system (model: Tanon 4600) of Shanghai Tianneng Life Science Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The luminescence intensitions of firefly luciferase (LUC) and renilla luciferase (REN) were determined using the TransDetect® Double-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit from Beijing Quanshijin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The LUC/REN ratio represents relative transcriptional activity.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

In this study, statistical analysis for this study was done using Excel 2024. The calculation method uses Student’s t-test, ns: no significant, *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001. In addition, in all experiments at least three biological replicates were performed in this study. No data were excluded from the analyses and no statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

3. Results

3.1. R22 Exhibits Seed Vigor Superior to Suinong14 Under Cold Tolerance

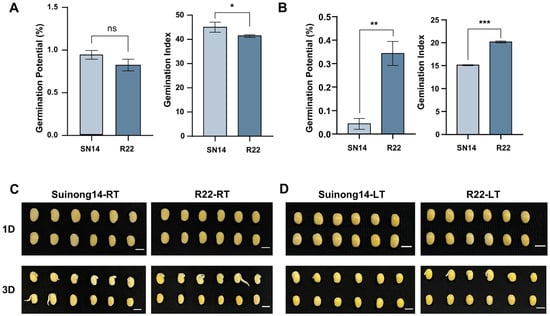

To assess seed vigor, the germination index (GI) and germination potential (GP) of Suinong14 (SN14) and CSSL_R22 were compared under controlled field conditions. At room temperature, the GP of R22 showed no significant differences relative to SN14, whereas the GI of R22 was significantly decreased relative to that of SN14 (Figure 1A and Table S3). Under low-temperature conditions, both GP and GI were significantly higher in R22 than in SN14 (Figure 1B). Representative images of germinating seeds under normal and low-temperature conditions were taken on the first and third days of germination (Figure 1C,D). Additionally, the germination rate (GR) was assessed under both temperature conditions. While no significant difference was observed between R22 and SN14 at room temperature, R22 exhibited a significantly higher GR under low-temperature conditions (Figure S1). The results show that the seed viability of R22 is significantly higher than that of SN14.

Figure 1.

(A) The difference in germination potential and germination index of SN14 and CSSL_R22 at 23 °C. (B) The difference in germination potential and germination index of SN14 and CSSL_R22 at 10 °C. (C) SN14 and CSSL_R22 representative soybean seed germination at room temperature on day 1 and day 3. (D) SN14 and CSSL_R22 representative soybean seed germination at 10 °C on day 1 and day3. Data represent mean ± SE (Standard Error) (n = 3 biological replicates); ns: no significant, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

3.2. Identification of Low-Temperature Stress QTLs in a Soybean CSSL Population

To identify QTLs associated with low-temperature tolerance, a population of 205 CSSLs was developed from successive backcrossing between Suinong14 (recurrent parent) and ZYD00006 (donor parent). QTL mapping was conducted using the ICIM method in ICIMapping 4.2, with a logarithm of the odds (LOD) threshold set at 2.5. Five QTLs associated with low-temperature tolerance during seed germination were identified on chromosomes 5, 7, 12, 13, and 20 (Table S1). These QTLs corresponded to five genomic intervals measuring 0.616425 Mb, 3.754025 Mb, 0.294564 Mb, 4.332036 Mb, and 0.168763 Mb, respectively. The LOD values for these intervals were 3.663, 68.7994, 19.4882, 5.2642, and 55.6152, with corresponding phenotypic contribution rates of 0.6558%, 28.8853%, 4.2418%, 3.874%, and 20.0939%. The additive effects were calculated as −0.0264, −0.2456, −0.0447, 0.0501, and 0.146, respectively.

3.3. Identification of Candidate Genomic Intervals Based on Chromosomal Insertions

During the backcrossing conducted when generating the 205 CSSLs, genomic fragments from the wild soybean ZYD00006 were introgressed into the cultivated SN14 genome. As a result, each CSSL primarily retained the genetic background of SN14 while incorporating small chromosomal segments from ZYD00006, contributing to the observed phenotypic variations between these lines.

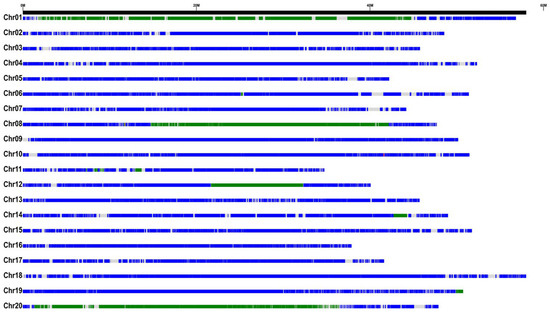

Resequencing of SN14 and ZYD00006 confirmed that CSSL_R22 harbors a homozygous introgression fragment from ZYD00006 (Figure 2). The introduced segments overlapped with previously identified meta-QTL intervals (Table S2).

Figure 2.

Overview of substituted genomic fragment from wild soybean in CSSL_R22. Blue, green, and gray sections denote the SN14 recurrent genome, the ZYD00006 donor genome, and genome gaps.

3.4. Transcriptomic Analysis of SN14 and R22 Under Normal and Low-Temperature Conditions

To investigate gene expression differences under cold stress, transcriptomic analysis was performed on the cotyledons and plumules of SN14 and R22 treated at 10 °C. RNA-seq was conducted on 24 samples (three biological replicates per genotype and treatment using the Illumina sequencing platform. Mapping efficiencies to the Williams82 reference genome ranged from 95.65% to 96.79%. Differentially expressed genes were identified using |log2FoldChange| > 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p < 0.05 as threshold criteria. Principal component analysis (PCA) and Pearson’s correlation coefficients confirmed good reproducibility between biological replicates (Tables S4 and S5 and Figure S2).

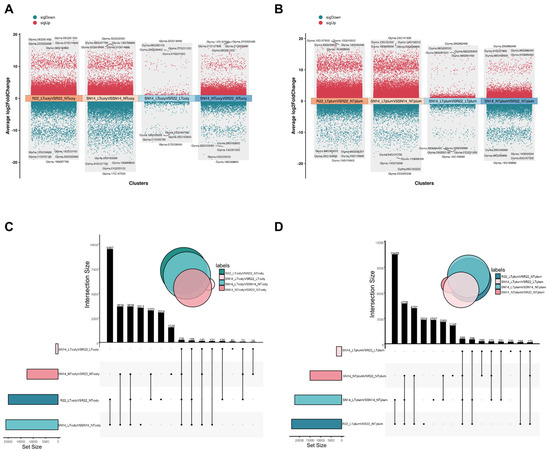

Based on the distribution maps of differentially expressed genes of SN14/R22 in cotyledons at normal and low temperatures, as well as the distribution maps of differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22 at normal and low temperatures. There were a total of 19,957 differentially expressed genes in the R22 low-temperature and normal-temperature comparison group, among which 12,855 were up-regulated and 7102 were down-regulated. There were a total of 20,940 differentially expressed genes in the SN14 low-temperature and normal-temperature comparison group, among which 11,585 were up-regulated and 9355 were down-regulated. At low temperatures, there were a total of 990 differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22, among which 285 were up-regulated and 705 were down-regulated. At room temperature, there were a total of 12,503 differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22, among which 8285 were up-regulated and 4218 were down-regulated (Figure 3A,C and Tables S6–S9). The distribution of differentially expressed genes of SN14/R22 in the embryo at normal and low temperatures, as well as the distribution of differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22 at normal and low temperatures. There were a total of 23,693 differentially expressed genes in the R22 low-temperature and normal-temperature comparison group, among which 17,216 were up-regulated and 6477 were down-regulated. There were a total of 22,193 differentially expressed genes in the SN14 low-temperature and normal-temperature comparison group, among which 15,119 were up-regulated and 7074 were down-regulated. At low temperatures, there were a total of 2498 differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22, among which 1221 was upregulated and 1277 was downregulated. At room temperature, there are a total of 14,962 differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22, among which 9346 are up-regulated and 5616 are down-regulated (Figure 3B,D and Tables S10–S13).

Figure 3.

(A) Volcano map of the distribution of differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22 in cotyledon. (B) Volcano map of the distribution of differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22 in plumule. |log2FoldChange| > 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p < 0.05. (C) Upset maps of differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22 in cotyledon at low and normal temperature, respectively. (D) Upset maps of differentially expressed genes of SN14 and R22 in plumule at low and normal temperature, respectively.

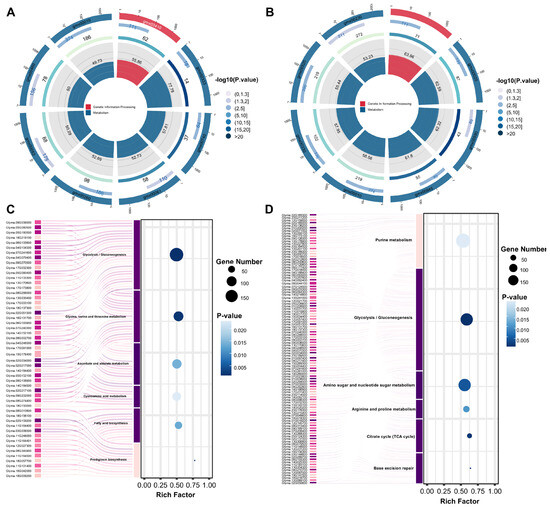

In the cotyledon, under normal and low-temperature conditions, SN14 (SN14_NTcoty vs. SN14_LTcoty) and (R22_NTcoty vs. R22_LTcoty). The number of genes shared by the two groups was 13,528, while the number of genes unique to R22 was 6429 (Figure S5A and Table S14). In the plumule, there were a total of 16,315 genes in the two groups of SN14 (SN14_NTplum vs. SN14_LTplum) and R22 (R22_NTplum vs. R22_LTplum) with differences between normal and low temperatures, while the specificity of R22 was 7378 genes (Figure S5B and Table S15). These unique DEGs may play a key role in the differences in cold stress responses between the two genotypes. We believe that the main regulatory pathways and genes that significantly promote the germination potential of R22 to be higher than that of SN14 under low-temperature conditions should be the genes specific to R22. Therefore, focus on this part of the genes. KEGG enrichment analysis was performed to detect significantly enriched pathways among DEGs in the two comparisons. In the cotyledon, the KEGG-enriched pathway R22_NTcoty vs. R22_LTcoty is compared with SN14_NTcoty vs. SN14_LTcoty. These included glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (gmx00010), glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism (gmx00260), luciferin biosynthesis (gmx00333), riboflavin metabolism (gmx00740), ascorbate and aldarate metabolism (gmx00053), and cyanoamino acid metabolism (gmx00460). Additionally, differences were observed in glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (gmx00630), fructose and mannose metabolism (gmx00051), and other metabolic pathways (Figure 4A,C and Table S16). In the plumule, significant differences were found between R22_NTplum vs. R22_LTplum and SN14_NTplum vs. SN14_LTplum in pathways such as phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (gmx00940), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (gmx00020), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (gmx00010), and pyruvate metabolism (gmx00620) (Figure 4B,D and Table S17).

Figure 4.

(A) KEGG enrichment analysis of the TOP8 pathways with the smallest p-value, R22_NTcoty vs. R22_LTcoty compared with SN14_NTcoty vs. SN14_LTcoty. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis of the TOP8 pathways with the smallest p-value, R22_NTplum vs. R22_LTplum compared with SN14_NTplum vs. SN14_LTplum. The first circle: KEGG Pathway ID. The second circle: p-Value. The third circle: The number of differentially expressed genes included in this function. The fourth circle represents the percentage of the enrichment factor (Rich Factor). (C) Sankey bubble chart of R22_NTcoty vs. R22_LTcoty compared with SN14_NTcoty vs. SN14_LTcoty. (D) Sankey bubble chart of R22_NTplum vs. R22_LTplum compared with SN14_NTplum vs. SN14_LTplum. The left figure shows the distribution of DEGs, and the right figure shows the p-value of the enrichment pathway.

3.5. Interactive Network for Soybean Seed Germination Under Cold Tolerance

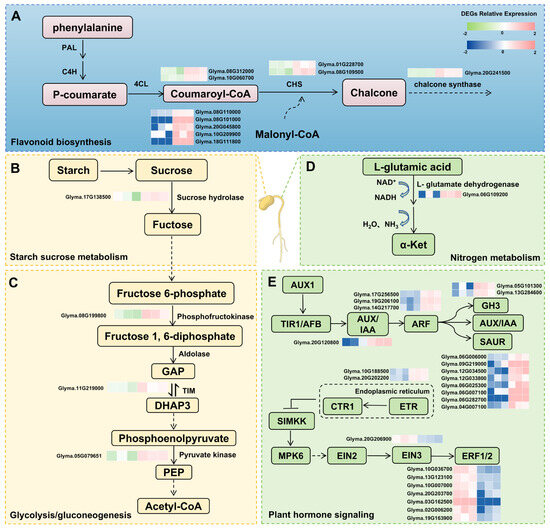

The DEGs identified in the cotyledon and plumule suggest that these tissues play distinct roles in the seed germination process, with differential gene expression patterns reflecting their unique responses to environmental stress. The DEGs associated with responses to normal and low temperatures likely correspond to variations in stress-related gene activity.

During seed germination under low-temperature conditions, the cotyledon primarily responds by accumulating essential nutrients, including starch, sucrose, and glucose, whereas the plumule is involved in hormone signaling and secondary metabolism. The present analysis indicates that the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway is enriched in both tissues, with key enzymes such as cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) and chalcone synthase (CHS) playing crucial roles in regulating responses to cold stress (Figure 5A). The pathways related to sucrose and starch biosynthesis, as well as glycolysis, are essential for nutrient accumulation and metabolism during germination. Key enzymes involved in these processes, such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and triose phosphate isomerase, were expressed at levels significantly higher in the R22 cotyledon compared to SN14. Seedlings lacking pyruvate kinase in Arabidopsis thaliana cannot germinate by using seed-stored compounds [29] (Figure 5B,C).

Figure 5.

Transcriptomics was used to analyze the specific expression pathways in cotyledon and germ. The heat map shows the relative expression (Cotyledon: green to red; Plumule: blue to red). (A) represents the pathway that is expressed in both tissues, (B,C) represents the major pathway where the differentially expressed genes reside in the cotyledon, (D,E) represents the major pathway where the differentially expressed genes reside in the plumule. The left side of the heat map shows the log2FPKM of three biological replicates of SN14 at low temperature, and the right side shows the log2FPKM of three biological replicates of R22 at low temperature.

Within the nitrogen metabolism pathway, Glyma.06G109200 was annotated as encoding NADH, a critical marker in mitochondrial energy production. An increase in NADH levels indicates a metabolic imbalance [30]. Additionally, components of the auxin regulatory pathway, including auxin response factors, GH3 family proteins, and SAUR family proteins, exhibited increased expression in R22. The increase in the contents of IAA is manifested as the enhanced tolerance of dormant seeds to low temperatures [31]. The GH3 gene can be upregulated by the expression of related transcription factors during development, directly activating the auxin binding process [32]; The GH3 gene family plays a crucial role in maintaining the optimal level of endogenous IAA through the coupling pathways of amino acids, sugars and peptides in plant cells [33]. After low-temperature treatment, the plant materials with strong cold tolerance had a higher germination rate and higher levels of indoleacetic acid (IAA) compared with those with low tolerance [34]. Furthermore, ethylene receptors act on the protein kinase CTR1, leading to upregulation of related genes, while the EIN3-binding F-box protein, an ethylene-insensitive transcription factor, showed downregulation in R22 at low temperature. (Figure 5D,E). Previous studies have confirmed that the low-temperature germination rate of seeds treated with ethylene has increased [35]. The negative regulator CTR1, in turn, directly or indirectly inhibits EIN2, which is an important positive regulator of ethylene signal transduction [36]. EIN3 (ethylene-insensitive 3) and EIL1 (EIN3-like 1) are key transcription factors in the ethylene signaling pathway. They negatively regulate the expression of CBF [37] by binding to the promoter of the key factor CBF corresponding to cold stress, thereby negatively regulating the low-temperature tolerance of plants [38].

In summary, soybean seed germination is modulated by multiple pathways, with key genes in each pathway influencing expression changes under low-temperature stress. The interaction between storage compounds and signaling molecules is vital for successful germination (Figure 5). These findings suggest that the enhanced expression of stress response factors in R22 contributes to its superior low-temperature tolerance, potentially due to the evolution of genes associated with cold-adaptive germination mechanisms.

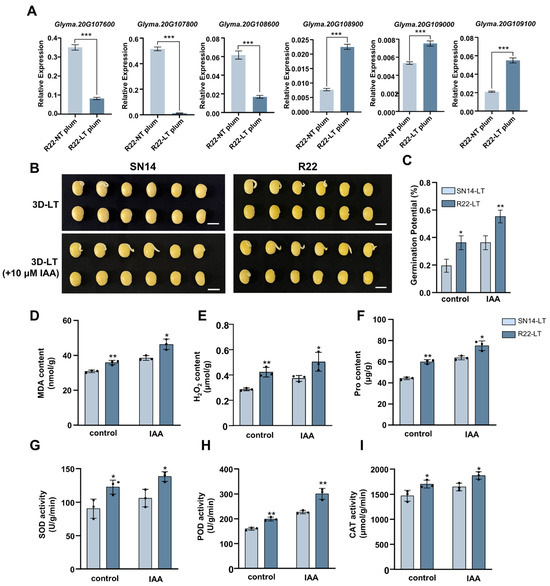

3.6. KANADI1 Regulates the Germination of SN14 and R22 at Low Temperatures and Participates in the Auxin Regulatory Pathway

Through the combined analysis of QTL mapping and transcriptomic data, 6 candidate genes were identified, and their expression in R22 germ was verified by qPCR. The expression trend detected by qRT-PCR was consistent with the results of RNA-seq (Figure 6A and Table S18). Among the candidate genes, Glyma.20G107600 encodes the PHOSPHOLIPASE-LIKE PROTEIN (PEARLI 4) FAMILY PROTEIN, and Glyma.20G107800 is annotated as glyalate reductase. Glyma.20G109100 is a glycosyltransferase-associated protein, while Glyma.20G108900 and Glyma.20G109000 are proteins of unknown function. Glyma.20G108600 was annotated as the transcription factor KANADI1 (KAN1), belonging to the same family as AtKANADI1 (AT5G16560) and sharing the same conserved domain (Figure S7A,B). AtKANADI1 regulates organ development by transcriptional inhibition of genes involved in auxin transport and signal transduction, thereby regulating auxin transport, signal transduction and transcriptional activity [39]. These results imply that the interconnected nature of cold tolerance during seed germination with auxin-associated pathways.

Figure 6.

(A) The relative expression levels of 6 candidate genes CSSL_R22 in the germ were studied after normal and low temperature treatment, respectively. (B) Comparison of the germination potential of SN14 and R22 before and after treatment with 10 μM IAA under low-temperature conditions. (C) Representative seeds of SN14 and R22 before and after treatment with 10 μM IAA. (D–I) Measurements of Malondialdehyde content (MDA, (D)), H2O2 content (H2O2, (E)), Proline content (Pro, (F)), Superoxide Dismutase activity (SOD, (G)), Peroxidase activity (POD, (H)) and Catalase activity (CAT, (I)). Data represent mean ± SE (Standard Error) (n = 3 biological replicates); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

To verify the involvement of auxin in cold tolerance, we determined the optimal concentration of IAA treatment (Figure S6), and supplemented SN14 and R22 with exogenous 10 μM IAA under cold treatment. The results showed that after treatment with 10 μM IAA, the germination potential of SN14 was significantly increased and basically reached the same level as before R22 treatment. After treatment with 10 μM IAA, the germination potential of R22 was significantly enhanced (Figure 6B,C). Under low-temperature stress, malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) serve as key diagnostic markers for oxidative damage. Therefore, the contents of MDA and H2O2 were measured in SN14 and R22 under cold stress with and without IAA treatment. The results indicated that under stress conditions, R22 exhibited significantly higher levels of MDA and H2O2 relative to SN14. Furthermore, exogenous IAA application significantly induced the accumulation of both MDA and H2O2 in both cultivars (Figure 6D,E). To further dissect the antioxidant response, we quantified the activity of key ROS-scavenging enzymes and measured non-enzymatic antioxidant levels. Under low temperatures condition, R22 showed markedly higher activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) compared to SN14, while the enzyme activities were significantly increased after IAA treatment. Additionally, the level of non-enzymatic antioxidants Proline (Pro) displayed a parallel trend (Figure 6F–I). This coordinated upregulation of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic ROS defense systems contributes to the superior oxidative stress resilience observed in R22.

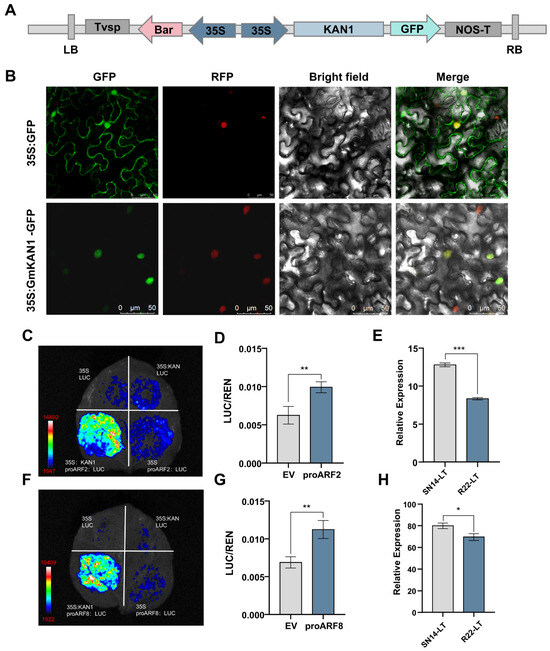

To functionally verify the involvement of auxin in GmKAN1-mediated cold tolerance, we constructed a GFP fusion protein expression system. Subcellular localization assays confirmed that GmKAN1 is predominantly localized within the nucleus, consistent with its role as a transcription factor (Figure 7A,B). The auxin response factor families ARF2 and ARF8 are regarded as negative regulatory factors of auxin [40,41,42]. To verify whether GmKAN1 binds to the soybean ARF genes and thereby regulates seed germination. A dual-luciferase reporter assay in planta demonstrated that GmKAN1 could bind to the downstream target genes GmARF2 and GmARF8 (Figure 7C,D,F,G). Then, the relative expression levels of ARF2 and ARF8 in SN14 and R22 were investigated. Both showed higher expression levels in SN14 than in R22, which was the same trend as the binding of the transcriptional inhibitory factor KAN1 to the growth factor negative regulators ARF2 and ARF8 (Figure 7E,H).

Figure 7.

(A) Schematic overview of the utilized pSOY1-GmKAN1 vector, with expression elements marked with arrows. (B) Subcellular localization analyses of GmKAN1 were conducted in tobacco leaves, with confocal images showing the localization of GFP and GmKAN1-GFP. Scale Bar = 50 μm. GFP fluorescence field, RFP fluorescence field, bright field and fluorescence fusion are arranged in order. (C) Dual luciferase reporter system validation of GmKAN1 binding to GmARF2. The upper left, upper right, and lower right panels represent control groups, while the lower left panel shows the experimental group. (D) Statistical comparison of LUC/REN values between the control group and the experimental group. (E) The relative expression levels of ARF2 at SN14 low temperature and R22 low temperature. (F) Dual luciferase reporter system validation of GmKAN1 binding to GmARF8. The upper left, upper right, and lower right panels represent control groups, while the lower left panel shows the experimental group. (G) Statistical comparison of LUC/REN values between the control group and the experimental group. (H) The relative expression levels of ARF8 at SN14 low temperature and R22 low temperature. Data represent mean ± SE (Standard Error) (n = 3 biological replicates); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

4. Discussion

In this study, to investigate the genetic basis of low-temperature seed germination in soybeans, a CSSL population was developed using the improved cultivar SN14 and the wild accession ZYD00006. Molecular marker-assisted selection was employed to introduce chromosome fragments from ZYD00006, leading to the identification of five QTLs associated with seed viability, all of which correlated with GP. To further refine these findings, whole-genome resequencing, chromosome fragment insertion analysis, and RNA-Seq were conducted to identify loci associated with seed viability.

Subsequent RNA-Seq and qPCR analyses confirmed Glyma20G108600 as a key gene involved in seed viability. Glyma20G108600 encodes KANADI1 protein, a member of the GARP protein family, which plays a crucial role in polarity establishment during embryo, shoot, and root patterning [43]. KAN1 influences plant organ development by modulating hormone distribution and signaling, particularly auxin and cytokinin pathways. Furthermore, KAN1 may contribute to stress responses, such as drought and salt tolerance, by regulating hormonal homeostasis. Through its target gene auxin, KAN1 exerts control over organ development at multiple regulatory levels [44,45]. Additionally, KAN1 influences the expression of genes involved in the response to abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, and ethylene, further underscoring its role in seed germination and stress adaptation. Auxin, a key plant hormone, is fundamental for tissue differentiation and developmental regulation [46]. These findings strongly support the role of Glyma20G108600 as a crucial mediator of soybean seed viability and provide a foundation for further investigations into the molecular mechanisms governing soybean germination under low-temperature conditions.

Data suggest that KANADI1 directly influences the auxin signaling pathway by binding to and repressing early auxin response genes, including three GH3 genes (WES1, DFL1, DFL2), three SAUR-like genes (AT1G75590, AT1G19840, AT2G21210), and two Aux/IAA genes (IAA2, IAA13). Additionally, KAN1 regulates genes associated with responses to brassinosteroids, jasmonic acid, abscisic acid, ethylene, cytokinin, and gibberellin, further underscoring its role in hormone signaling [40]. GmKAN1 inhibits GmARF2 and GmARF8 to regulate Auxin signaling, and auxin plays a core role in seed germination and stress response. The Aux/IAA family and the auxin response factor (ARF) gene are two key gene families that play a significant role in plant growth and development by regulating the auxin signaling pathway. In Arabidopsis thaliana, ARF2 is believed to act as a transcriptional suppressor by binding to synthetic auxin response elements [40,41]; ARF8 may regulate the level of IAA in a negative feedback manner by modulating the expression of auxin related genes [42]. Dual-luciferase assay confirmed that GmKAN1 can bind to the promoters of GmARF2 and GmARF8, leading to their transcriptional inhibition in R22 under low-temperature conditions. This inhibition may reduce the inhibitory effect of ARF2/ARF8 on auxin signaling, thereby promoting the expression of auxin response genes and enhancing germination activity. This mechanism is consistent with the studies in Arabidopsis thaliana. ARF inhibition enhances stress tolerance through hormonal homeostasis changes.

When plants are under stress, the antioxidant defense system comes into play, eliminating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and providing a complete cellular environment for the photosynthetic system. The accumulation of ROS caused by environmental stress will prompt plants to synthesize an antioxidant enzyme system through signal transduction to eliminate ROS. The antioxidant enzyme system in plants consists of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT). The improvement of a plant’s stress resistance is related to the antioxidant enzyme system within its body, which is composed of peroxidase (POD) and others. When plants age or are in adverse environments, peroxidation reactions occur in the cell membrane lipids, damaging the structure of biological membranes, mainly the cytoplasmic membrane. This leads to damage to the structure and function of the cell membrane and alters its permeability. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is one of the products, and thus MDA is an indicator of membrane lipid peroxidation. It indicates the degree of lipid peroxidation on the cell membrane and the strength of the plant’s response to adverse conditions [47,48]. Exogenous IAA treatment significantly enhanced the germination potential of SN14 and R22 under cold stress, confirming the positive role of auxin in cold tolerance. In addition, IAA treatment led to an increase in the activities of SOD, POD and CAT, and an increase in proline content, indicating an enhanced antioxidant capacity. This is consistent with previous reports that auxin can stimulate the ROS clearance system under abiotic stress. It is worth noting that R22 has a higher basal level of these antioxidants than SN14, indicating that the auxin pathway mediated by GmKAN1 contributes to the oxidative stress response, which is crucial for germination at low temperatures.

Our research is one of the earliest to link GmKAN1 to the cold resistance of soybean seeds during germination. Although KAN1 has been studied in the context of Arabidopsis thaliana leaf development and hormone signal transduction, its role in germination under abiotic stress has not been fully explored. Previous QTL studies on soybeans have identified multiple seed viability [49,50] and cold tolerance sites [19,20,21], but few studies have integrated transcriptomics and functional validation to determine candidate genes. Our work fills this gap by integrating genetic mapping, transcriptomics and molecular detection. However, this study also has several limitations. Firstly, the CSSL population originated from a single wild donor (ZYD00006), which might have limited the genetic diversity of the identified QTLs. Secondly, although we have verified the binding of GmKAN1 to GmARF2/8, the downstream auxin and its interactions with other hormone pathways (such as ABA and ethylene) still deserve further study. There are no stable genetic transformation materials available to accurately verify our initial results. Finally, physiological assays were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions; Field verification in a natural low-temperature environment will enhance the applicability of our research results.

Based on the existing experimental results, we proposed a working model of cold tolerance mediated by GmKAN1 to study the role of GmKAN1 in the cold tolerance of soybeans during germination. Under low-temperature stress, the expression of GmKAN1 is upregulated in cold resistance R22. The GmKAN1 protein binds to the promoters of GmARF2 and GmARF8 in the cell nucleus, inhibiting their transcription. This inhibition mitigated the inhibitory effect of ARF2/ARF8 on auxin signaling, thereby enhancing the expression of auxin response genes. The resulting auxin activation promotes the activity of antioxidant enzymes and proline accumulation, reduces oxidative damage and improves membrane stability. Meanwhile, tissue-specific metabolic adjustments in the cotyledon (nutrient mobilization) and embryo (hormone signaling) support successful germination under cold stress. The insights from this study could also inform breeding efforts to develop soybean cultivars with enhanced seed viability, ultimately improving crop yield and quality.

5. Conclusions

This study identified a novel regulatory mechanism for cold tolerance during soybean germination. GmKAN1 (Glyma.20G108600), a major QTL transcription factor located on chromosome 20, acts as a transcriptional suppressor for GmARF2 and GmARF8, thereby regulating auxin signaling and strengthening the antioxidant defense mechanism under cold stress. These findings not only clarify the previously unreported regulatory module of KAN1-ARF-auxin in the cold adaptation of soybeans but also provide functional markers and candidate targets for molecular breeding to enhance the germination recovery ability of soybeans in low-temperature environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16010045/s1, Figure S1: (A) Representative germination of SN14 and CSSL_R22 soybean seeds at room temperature on day 7. (B) Representative germination of SN14 and CSSL_R22 soybean seeds at 10 °C on day 7. (C) Germination rate of SN14 and CSSL_R22 at 23 °C. (D) Germination rate of SN14 and CSSL_R22 at 10 °C; Figure S2: (A) Pearson’s correlation coefficients between different replicates. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) of cotyledons. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of plumule; Figure S3: (A) KEGG analysis barplot of R22_LTcotyVSR22_NTcoty. (B) KEGG analysis barplot of SN14_LTcotyVSSN14_NTcoty. (C) KEGG analysis barplot of R22_LTplumVSR22_NTplum. (D) KEGG analysis barplot of SN14_LTplumVSSN14_NTplum; Figure S4: (A) GO enrichment analysis barplot of R22_LTcotyVSR22_NTcoty. (B) GO enrichment analysis barplot of SN14_LTcotyVSSN14_NTcoty. (C) GO enrichment analysis barplot of R22_LTplumVSR22_NTplum. (D) GO enrichment analysis barplot of SN14_LTplumVSSN14_NTplum; Figure S5: (A) Compared with SN14_NTcoty vs. SN14_LTcoty, R22_NTcoty vs. R22_LTcoty had 6429 different differentially expressed genes. (B) Compared with SN14_NTplum vs. SN14_LTplum, R22_NTplum vs. R22_LTplum had 7378 different differentially expressed genes; Figure S6: (A) At room temperature, the germination potential and germination index of SN14 seeds under treatment conditions with IAA concentrations of 0 μM, 10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM, 200 μM, and 400 μM. (B) Statistical table of germination potential and germination index under different IAA concentration treatment conditions; Figure S7: Phylogenetic and conserved motif analysis of the transcription factor KANAD1. (A) Phylogenetic trees of the KANAD1 gene in soybeans and Arabidopsis thaliana. (B) Analysis of conserved domains of the KANAD1 gene in soybeans and Arabidopsis thaliana; Table S1: Distribution of introduced fragments in CSSL R22; Table S2: Statistics of raw RNA-seq data; Table S3: Germination counts of SN14 and R22 at normal and low temperatures; Table S4: Statistics of raw RNA-seq data; Table S5: Mapping statistics of RNA-seq data; Table S6: R22_LTcotyVSR22_NTcoty_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S7: SN14_LTcotyVSSN14_NTcoty_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S8: SN14_LTcotyVSR22_LTcoty_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S9: SN14_NTcotyVSR22_NTcoty_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S10: R22_LTplumVSR22_NTplum_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S11: SN14_LTplumVSSN14_NTplum_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S12: SN14_LTplumVSR22_LTplum_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S13: SN14_NTplumVSR22_NTplum_genes_significantly_differential_expression; Table S14: The unique DEGs of R22_LTcoty and R22_NTcoty are compared with SN14_LTcoty and SN14_NTcoty; Table S15: The unique DEGs of R22_LTplum and R22_NTplum are compared with SN14_LTplum and SN14_NTplum; Table S16: The unique KEGG pathway of R22_LTcoty and R22_NTcoty are compared with SN14_LTcoty and SN14_NTcoty; Table S17: The unique KEGG pathway of R22_LTplum and R22_NTplum are compared with SN14_LTplum and SN14_Ntplum; Table S18: Primers used for qRT-PCR.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Q. and C.X.; methodology, C.D., Z.Q. and C.X.; investigation, C.D., Q.W., C.T., L.C., C.G., W.P., Q.D., X.H., C.L. and S.Z.; data curation, C.D., Q.W., C.T., L.C., C.G., W.P. and X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G., Z.Q. and C.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.Q., Q.D., S.Z. and C.X.; visualization, C.D. and C.X.; supervision, Z.Q., Q.C. and C.X.; funding acquisition, C.L., Q.C. and C.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (ZL2024C007), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472108, 32501982), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025MD774052), the Hainan Seed Industry Laboratory and China National Seed Group (B23YQ1503), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023ZD0403201-03, 2021YFD1201103), and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-04-PS14).

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information database with the bio-project accession number PRJNA1246612.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deng, Z.; Qu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T. Current progress and prospect of crop quality research. Sci. Sin. 2021, 51, 1405–1414. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Derynck, M.R.; Li, X.; Telmer, P.; Marsolais, F.; Dhaubhadel, S. A single-repeat MYB transcription factor, GmMYB176, regulates CHS8 gene expression and affects isoflavonoid biosynthesis in soybean. Plant J. 2010, 62, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Li, W.; Niu, C.; Wei, W.; Hu, Y.; Han, J.; Lu, X.; Tao, J.; Jin, M.; Qin, H.; et al. A class B heat shock factor selected for during soybean domestication contributes to salt tolerance by promoting flavonoid biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Peng, L.; Huang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; He, Y. Genome-wide association study reveals that JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN 5 regulates seed germination in rice. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.; Bradford, K.; Khanday, I. Seed germination and vigor: Ensuring crop sustainability in a changing climate. Heredity 2022, 128, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Guan, W.; Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Fan, H.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Sun, D.; Jing, R. QTL mapping and candidate gene analysis of seed vigor-related traits during artificial aging in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Guo, J.; Shabala, S.; Wang, B. Reproductive Physiology of Halophytes: Current Standing. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Day, D.; Fricke, W.; Watt, M.; Arsova, B.; Barkla, B.; Bose, J.; Byrt, C.; Chen, Z.; Foster, K.; et al. Energy costs of salt tolerance in crop plants. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1072–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, M. Physiological responses and tolerance mechanisms of low temperature stress in plants. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, K.; Takeda, M.; Kidokoro, S.; Yamada, K.; Sakuma, Y.; Urano, K.; Fujita, M.; Yoshiwara, K.; Matsukura, S.; Morishita, Y.; et al. Metabolic pathways involved in cold acclimation identified by integrated analysis of metabolites and transcripts regulated by DREB1A and DREB2A. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Ji, H. Enhancement of plant cold tolerance by soybean RCC1 family gene GmTCF1a. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zou, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Ma, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S. Soybean GmMYB76, GmMYB92, and GmMYB177 genes confer stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Fakher, B.; Ashraf, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Qin, Y. Plant Low-Temperature Stress: Signaling and Response. Agronomy 2022, 12, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, D.; Qi, Z.; Jiang, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Hu, J.; Han, H.; Hu, G.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q. QTL location and epistatic efect analysis of 100-seed weight using wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. & Zucc.) chromosome segment substitution lines. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e149380. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Lee, M.; Lübberstedt, T.; Zhao, G. QTL Mapping Low-Temperature Germination Ability in the Maize IBM Syn10 DH Population. Plants 2022, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Huang, R.; Wu, G.; Sun, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. Transcriptomic and QTL Analysis of Seed Germination Vigor under Low Temperature in Weedy Rice WR04-6. Plants 2023, 12, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Jan, R.; Park, J.; Asif, S.; Zhao, D.; Kim, E.; Jang, Y.; Eom, G.; Lee, G.; Kim, K. QTL Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Seed Germination Response to Low Temperature in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Jiang, M.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X. QTL mapping for low temperature germination in rapeseed. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, D.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Shi, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Qiu, L.; Jia, H.; et al. Cold tolerance SNPs and candidate gene mining in the soybean germination stage based on genome-wide association analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, P.; Li, W.; Gao, Y.; Hu, G.; Chen, Q. Genotype Analysis and QTL Mapping for Tolerance to Low Temperature in Germination by Introgression Lines in Soybean. Acta Agron. Sin. 2009, 35, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qiu, P.; Jiang, H.; Liu, C.; Xin, D.; Li, C.; Hu, G.; Chen, Q. Dissection of genetic overlap of drought and low-temperature tolerance QTLs at the germination stage using backcross introgression lines in soybean. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 6087–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Hou, L.; Xie, J.; Cao, F.; Wei, R.; Yang, M.; Qi, Z.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, D.; et al. Construction of Chromosome Segment Substitution Lines and Inheritance of Seed-Pod Characteristics in Wild Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 869455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Qin, H.; Mao, X.; Jiang, H.; Xin, D.; Yin, Z.; Zhu, R.; et al. Meta-analysis and transcriptome profiling reveal hub genes for soybean seed storage composition during seed development. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 2109−2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liao, X.; Cui, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Du, H.; Ma, Y.; Ning, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, F.; et al. A cation diffusion facilitator, GmCDF1, negatively regulates salt tolerance in soybean. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wan, X.; Crossa, J.; Crouch, J.; Weng, J.; Zhai, H.; Wan, J. QTL mapping of grain length in rice (Oryza sativa L.) using chromosome segment substitution lines. Genet. Res. 2006, 88, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ribaut, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, J. Inclusive composite interval mapping (ICIM) for digenic epistasis of quantitative traits in biparental populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 116, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ye, G.; Wang, J. A modified algorithm for the improvement of composite interval mapping. Genetics 2007, 175, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Chang, N.; Nan, W.; Wang, S.; Ruan, M.; Sun, L.; Li, S.; Bi, Y. Cytosolic Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Is Involved in Seed Germination and Root Growth Under Salinity in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M. NAD+/NADH homeostasis affects metabolic adaptation to hypoxia and secondary metabolite production in filamentous fungi. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xia, T.; Li, B.; Yang, H. Hormone and carbohydrate metabolism associated genes play important roles in rhizome bud full-year germination of Cephalostachyum pingbianense. Physiol. Plant 2022, 174, e13674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Sun, L.; Ju, Q.; Huang, H.; Lü, S.; Tran, L.; Xu, J. MYB70 modulates seed germination and root system development in Arabidopsis. iScience 2021, 24, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.; Bartel, B. Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Hong, X. Integrated analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveals insights for low-temperature germination in hybrid rapeseeds (Brassica napus L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 291, 154120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phartyal, S.; Rosbakh, S.; Gruber, M.; Poschlod, P. The sweet and musky scent of home: Biogenic ethylene fine-tunes seed germination in wetlands. Plant Biol. 2022, 24, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Yoon, G.; Shemansky, J.; Lin, D.; Ying, Z.; Chang, J.; Garrett, W.; Kessenbrock, M.; Groth, G.; Tucker, M.; et al. CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19486–19491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Song, Y.; Wu, S.; Peng, Y.; Ming, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Su, Z.; Gong, Z.; et al. Regulation of alternative splicing by CBF-mediated protein condensation in plant response to cold stress. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Tian, S.; Hou, L.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; Yang, S. Ethylene signaling negatively regulates freezing tolerance by repressing expression of CBF and type-A ARR genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2578–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Harrar, Y.; Lin, C.; Reinhart, B.; Newell, N.; Talavera-Rauh, F.; Hokin, S.; Barton, M.; Kerstetter, R. Arabidopsis KANADI1 acts as a transcriptional repressor by interacting with a specific cis-element and regulates auxin biosynthesis, transport, and signaling in opposition to HD-ZIPIII factors. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okushima, Y.; Mitina, I.; Quach, H.; Theologis, A. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 (ARF2): A pleiotropic developmental regulator. Plant J. 2005, 43, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schruff, M.; Spielman, M.; Tiwari, S.; Adams, S.; Fenby, N.; Scott, R. The AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 gene of Arabidopsis links auxin signalling, cell division, and the size of seeds and other organs. Development 2006, 133, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Muto, H.; Higuchi, K.; Matamura, T.; Tatematsu, K.; Koshiba, T.; Yamamoto, K. Disruption and overexpression of auxin response factor 8 gene of Arabidopsis affect hypocotyl elongation and root growth habit, indicating its possible involvement in auxin homeostasis in light condition. Plant J. 2004, 40, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merelo, P.; Paredes, E.; Heisler, M.; Wenkel, S. The shady side of leaf development: The role of the REVOLUTA/KANADI1 module in leaf patterning and auxin-mediated growth promotion. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 35, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, H.; Meng, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, F.; Qi, Y.; Yang, W.; Shu, K. The roles of auxin in seed dormancy and germination. Yi Chuan 2016, 38, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shu, K.; Liu, X.; Xie, Q.; He, Z. Two Faces of One Seed: Hormonal Regulation of Dormancy and Germination. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, C.; Nakagawa, A.; Kojima, S.; Takahashi, H.; Machida, Y. The complex of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES (AS) proteins plays a central role in antagonistic interactions of genes for leaf polarity specification in Arabidopsis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2015, 4, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.; Song, C. Reactive oxygen species: Multidimensional regulators of plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wu, F.; Xie, X.; Yang, C. Quantitative Trait Locus Mapping of Seed Vigor in Soybean under −20 °C Storage and Accelerated Aging Conditions via RAD Sequencing. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 43, 1977–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thenveettil, N.; Ravikumar, R.L.; Prasad, S.R. Genome-wide association study reveals the QTLs and candidate genes associated with seed longevity in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill). BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.