Abstract

Climate change and soil degradation represent a threat to essential crops such as maize. In Mexico, this grain is of strategic importance, yet yields are often low. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) can help mitigate this problem. The potential of Paenibacillus dendritiformis, isolated from the “El Chichonal” volcano (Chiapas, Mexico), was evaluated as a PGPB under laboratory conditions using infertile soil. Its capacity for nitrogen fixation (NF), phosphate solubilization (PS), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production, biocontrol activity, and tolerance to different pH levels, temperature, and salinity were assessed. The effect of inoculation on maize seed germination and vigor was examined in vitro through morphological variables and dry weight. Completely randomized and randomized block designs were used, along with Duncan’s test (p < 0.05) for mean comparison. Cohen’s d was used to estimate the size of the treatment effect. P. dendritiformis demonstrated NF, PS, and IAA production, a wide range of environmental tolerance, and promoted root length and number of root hairs in maize at seven days, as well as increased leaf length and area and foliar and root dry weight at 14 days. It is concluded that P. dendritiformis has potential as a PGPB for infertile soils, based on laboratory evaluations.

Keywords:

maize; Zea mays; PGPB; soil; biofertilizer; sustainable agriculture; volcanic soil bacteria; stress tolerance 1. Introduction

Agricultural productivity is affected by nutrient deficiencies in the soil, a phenomenon caused by anthropogenic activities or geographical conditions [1]. Maize is an important cereal for human and animal consumption, as well as for industrial use [2]. In Mexico, maize is the most important crop for the national economy, occupying a larger cultivated area than any other crop—approximately 6,655,097 ha [3]. Despite its relevance, productivity remains low: 8.6 t under irrigated production and 2.6 t under rainfed conditions [3,4]. To secure production, agronomic practices such as excessive application of chemical fertilizers are employed; however, these may cause problems such as nutrient loss and depletion of humus and microbial activity, resulting in reduced productivity and environmental pollution [5].

On the other hand, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) can enhance plant development through a wide variety of mechanisms, establishing an alliance between soil, plants, and microorganisms [6,7]. The use of PGPB has shown potential as a sustainable agricultural practice [8], offering an attractive alternative to replace chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and supplements [9]. The mechanisms used by PGPB to promote plant growth are classified as direct and indirect: the former refers to the direct supply of nutrients to the plant, while the latter involves mechanisms that protect the plant from infections and reduce environmental stress [8].

Among PGPB, there are microorganisms classified as extremophiles (MOEX), which have been isolated from extreme environments and some of which are capable of promoting plant growth under adverse climatic conditions due to their ability to synthesize exopolysaccharides, phytohormones, and chelating compounds [10,11], as well as to produce growth regulators, vitamins, and amino acids that stimulate plant development and help plants adapt to these environments [12]. These microorganisms have developed survival strategies for extreme environments with variations in pH, salinity, light, nutrient scarcity, low humidity, pressure, and radiation [13,14]. Such environments exert selective pressures on bacteria, allowing them to acquire distinctive traits [15], attributable to the evolution of adaptive mechanisms at both genetic and physiological levels [16].

Active volcanic environments are extreme habitats characterized by acidic conditions and low nutrient availability, where microorganisms with beneficial effects on plants and ecosystems have been found, increasing the survival, growth, development, and stress tolerance of host plants [16,17,18]. In vitro studies have shown that some of these bacteria isolated from volcanic environments can fix nitrogen, produce auxins, survive abiotic stress conditions, and antagonize pathogenic fungi [19]. These environments represent a high potential for microbial bioprospecting, as microorganisms adapted to such conditions and exhibiting evolutionary traits have been identified in these sites [20]. These adaptations may be related to the pressure exerted by the physicochemical properties of soil derived from volcanic eruptions, which limit microbial activity. For example, the crater of the active volcano El Chichón exhibits high temperatures, low pH, and elevated concentrations of heavy metals [21]. Therefore, these characteristics make strains obtained from volcanic environments promising candidates resistant to adverse conditions and useful in the restoration or management of agricultural soils subjected to abiotic stress [18,22].

In maize studies, these microorganisms have been used as biofertilizers, improving grain yield, nutritional quality, and forage production and even increasing organic matter content and reducing soil acidity [5]. Consequently, the use of PGPB with MOEX characteristics may be one of the most promising biotechnological strategies for improving soil fertility and functionality [23]. Likewise, studies in maize conducted with different Paenibacillus species have shown that they promote the growth of vegetative components such as leaf length, leaf area, and the accumulation of shoot and root dry matter [24,25,26]. Similarly, Paenibacillus dendritiformis has previously been described as an ecologically useful rhizobacterium with potential applications in vegetation development. It can thrive in soils with low nutrient content, low moisture, low organic matter, nitrogen deficiency, and toxic levels of heavy metals—conditions that can render soil sterile—and it has even been reported in soils contaminated with creosote, highly saline soils, and marine sediments [27,28,29,30].

It is well known that Mexican agriculture faces low productivity due to soil degradation and challenging farming conditions, compounded by the negative effects of excessive chemical fertilizer use. For this reason, the present study aims to evaluate the inoculation of maize with Paenibacillus dendritiformis isolated from volcanic conditions and grown in degraded soil and to analyze its effects on plant performance.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted in the Laboratorio de Genética y producción de planta of the Instituto de Silvicultura e Industria de la Madera at Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, and in the Laboratorio de Suelos of TecNM, Instituto Tecnológico del Valle del Guadiana campus.

2.1. Bacterial Strains

An environmental isolate coded as D28 was evaluated. This isolate is one of the 311 microorganisms obtained by Ríos-Reyes [18] during the exploration of microbial and plant diversity at the “El Chichonal” volcano, conducted as part of a sustainable agriculture prospection. Isolate D28 was specifically recovered from the deep roots of the native vegetation growing on the volcanic slopes. The positive control consisted of a Bacillus megaterium strain (GenBank accession no. KM654562.1), obtained from the culture collection of the Laboratorio de Biotecnología of the Instituto Tecnológico de Durango. The use of B. megaterium as a positive control is supported by previous studies that have demonstrated its plant growth-promoting activities [31,32,33,34].

2.2. DNA Extraction, Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

Genomic DNA from isolate D28, grown in LB broth for 24 h, was extracted using the CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method [35]. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using primers 16S–8F (5′-AGA GTT TGA TYM TGG CTC AG-3′) and 16S–1462R (5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT AYG ACTT-3′). The PCR products were purified and subsequently sent for sequencing at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity (Langebio, Irapuato, Mexico). Whole-genome sequencing of isolate D28 was performed using the Illumina platform at the Genomics Core Lab, Monterrey, Mexico. The genome was assembled and annotated using the multitool pipeline of the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC, Chicago, IL, USA) [36]. The 16S rRNA gene sequences were retrieved and analyzed from the GenBank database [37], aligned with MUSCLE, and phylogenetic analysis was carried out under a neighbor-joining model. Statistical branch support was estimated from 1000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA 12 [38].

2.3. Tests to Determine Plant Growth-Promoting Traits

2.3.1. Nitrogen-Fixation Capacity

The nitrogen-fixing ability of P. dendritiformis, was evaluated following the methodology described by Batista [39] using NFb medium. A color change from green to blue in the medium, along with the formation of a growth halo, indicated nitrogen-fixation capacity.

2.3.2. Phosphate Solubilization

Phosphate solubilization was assessed using NBRIP medium (National Botanical Research Institute’s Phosphate Growth Medium). Cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 14 days to observe halo formation, indicating phosphorus solubilization. The Phosphate Solubilization Index (PSI) was calculated using Equation (1) [39]:

where PSI = Phosphate Solubilization Index (<2 = low; 2–3 = medium; ≥3 = high); Dh = Diameter of the halo formed, measured in millimeters; Dc = Diameter of the colony, measured in millimeters

PSI = Dh/Dc

2.3.3. Indole-3-Acetic Acid Production

Paenibacillus dendritiformis was inoculated in TSB medium supplemented with L-tryptophan (5 g·L−1) and incubated at 28 °C, 160 rpm for 48 h. Subsequently, centrifuged at 5000× g for 10 min. The supernatant was mixed with Salkowski reagent (2 mL 0.5 M FeCl3, 49 mL distilled water, 49 mL 70% HClO4) in a 1:1 ratio and incubated in complete darkness for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 530 nm. IAA concentration was determined using a standard curve from 0 to 250 μg·mL−1. Sterile TSB with Salkowski reagent was used as a control [39].

2.3.4. Qualitative Biocontrol Assay Against Phytopathogenic Fungi

Fusarium graminearum PH-1 (NRRL 31084) [40], Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici strain 4287 (race 2, VCG 0030) [41], and Fusarium solani [42] were used as test pathogens. These phytopathogenic Fungi were selected because they were available in the fungal collection of the Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, and are commonly reported as important phytopathogenic fungi associated with maize and other crops. Conidia of F. graminearum were obtained by inoculating 1 cm2 of mycelium on wheat germ medium for 5 days at 26–28 °C with shaking at 150 rpm. Conidia of F. oxysporum and F. solani were obtained by inoculating 1 cm2 of mycelium on potato dextrose broth (PDB) for 4–5 days under the same conditions. Conidia were filtered, washed with sterile distilled water, and counted in a Neubauer chamber [43]. Fungi were cultured on PDA for 48 h, and 10 mm mycelial disks were placed in the center of PDA plates. Bacterial strains were streaked along the margins of the plates. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for 10 days. Fungal growth inhibition percentage by bacteria is calculated using Equation (2) [39]:

where a = fungal growth toward the bacterial strain; b, c, d = total fungal growth from the edge of the mycelial disk to the colony margin.

2.3.5. Quantitative Biocontrol Assay Using Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

Bacterial strains were streaked on TSA plates. 10 mm fungal mycelial disks were placed at the center of PDA plates. Plates containing bacteria and fungi were overlaid and sealed with double-layer Parafilm. Negative controls consisted of sterile TSA plates overlaid on PDA plates containing fungi. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for 7 days. Inhibition percentage (I%) was calculated using Equation (3) [39]:

where Ri = Diameter of mycelial growth of pathogenic fungi grown in the presence of the tested bacteria. Rc = Diameter of mycelial growth of pathogenic fungi grown in the presence of the control plate.

2.4. Tolerance to Extreme Environments

2.4.1. Growth at Different Temperatures

M9 minimal medium [44] was prepared with 15 g agar, 5.8 g Na2HPO4, 3 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g NaCl, 1 g NH4Cl, 2 g glucose, 0.49 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.0152 g CaCl2·2H2O, and 0.010 g thiamine, adjusted to 1 L and pH 6.5, sterilized at 120 °C for 20 min. Plates were inoculated in triplicate and incubated at 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 °C.

2.4.2. Growth at Different pH Levels

Strain growth was tested at pH 4–10 using M9 medium adjusted with HCl or NaOH.

2.4.3. Growth at Different Salinity Levels

M9 medium was modified with NaCl to reach concentrations of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 3.0 mol·L−1 (29.22, 58.44, 87.66, 116.88, and 175.32 g·L−1, respectively). Media were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min and inoculated by streaking, incubated at 28 °C.

2.5. Maize Germination and In Vitro Vigor Assay

The experimental treatments included seeds inoculated with P. dendritiformis, seeds inoculated with Bacillus megaterium (control), and uninoculated seeds. Maize seeds were surface-sterilized with 3% NaClO for 5 min, rinsed with sterile distilled water, treated with 70% ethanol for 5 min, and rinsed twice with sterile water [45]. Seeds were dried under a laminar flow hood. LB medium (1 g·L−1 casein peptone, 0.5 g·L−1 yeast extract, 1 g·L−1 NaCl) was inoculated with bacterial strains, incubated for 12 h at 28 °C and 120 rpm, and adjusted to 0.1 OD600 [46]. Cells were washed twice with sterile distilled water to remove the culture medium before seed inoculation. Seeds were submerged in the washed bacterial suspension for 30 min. Five seeds per treatment were placed in sterile Petri dishes containing filter paper [47]. A total of 45 seeds were evaluated per treatment, arranged as nine Petri dishes with five seeds each and incubated in darkness at 28 °C for 7 days, with 2 mL sterile water added every third day. Additionally, five seeds per pot were sown in 500 cm3 sterile soil pots. As with the in vitro assay, a total of 45 seeds were evaluated per treatment, distributed in nine pots with five seeds each. Pots were placed in a Biotronette Mark III environmental chamber (Lab-Line Instruments, Inc., Melrose Park, IL, USA) at 24 °C for 14 days and watered with 45 mL of sterile water every third day.

2.6. Soil Sampling and Analysis

The characteristics of the site where the soil samples were collected are summarized in Table 1. The sampling site was located at the coordinates 24°13′06″ N–104°43′42″ W, at an altitude of 1917 m, with an average annual temperature of 20.4 °C and an average annual precipitation of 463.2 mm. Soil samples and fertility evaluation were performed according to the Mexican Official Standard NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 [48]. Determined variables included pH, bulk density, organic matter, nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, potassium, carbonates, and bicarbonates. Soil texture was classified as sandy loam with neutral pH. Electrical conductivity indicated negligible salinity effects. Organic matter, as well as phosphorus, calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, carbonates, and bicarbonates, were all classified as very low; thus, the soil was considered infertile.

Table 1.

Soil analysis.

2.7. Vigor Variables

2.7.1. Germination Percentage

Germination percentage (GP) was calculated as described in Equation (4) [49]:

where ni = germinated seeds; N = total seeds.

2.7.2. Morphological Variables

Seedlings were anatomically dissected to measure primary root length, coleoptile length, number of adventitious roots, and number of root hairs. The length of the anatomical parts of maize seedlings was measured using an image analysis technique with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software [50]. For image processing, the software was calibrated using graph paper as a reference, correlating the millimeters on the paper with the number of pixels in the image along the X and Y axes. Subsequently, the images were uploaded into the system and converted to grayscale to perform the measurements.

2.8. Dry Weight Determination

Shoot and root samples were washed and dried at 45 °C in a forced-air oven until they were constantly weighted and recorded.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data normality and homogeneity of variances were tested using Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests. Phosphate solubilization and IAA production were analyzed with a completely randomized design. In vitro vigor and bacterial treatment effects were analyzed with a randomized block design. Duncan’s test (p < 0.05) was used for mean comparisons. Analyses were performed using R Core Team software [51]. Cohen’s d was used to estimate the effect size. This statistic quantifies the standardized mean difference between two groups ([52], Equation (5)). Two independent comparisons were performed. Group 1 contrasted uninoculated seeds with seeds inoculated with P. dendritiformis. Group 2 compared seeds inoculated with P. dendritiformis against those inoculated with B. megaterium.

where Numerator is the difference between means of the two groups of observations. The denominator is the pooled standard deviation. The standard deviation is calculated from the differences between each individual observation and the mean for the group. Interpretation is to refer to effect sizes as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8) [52].

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

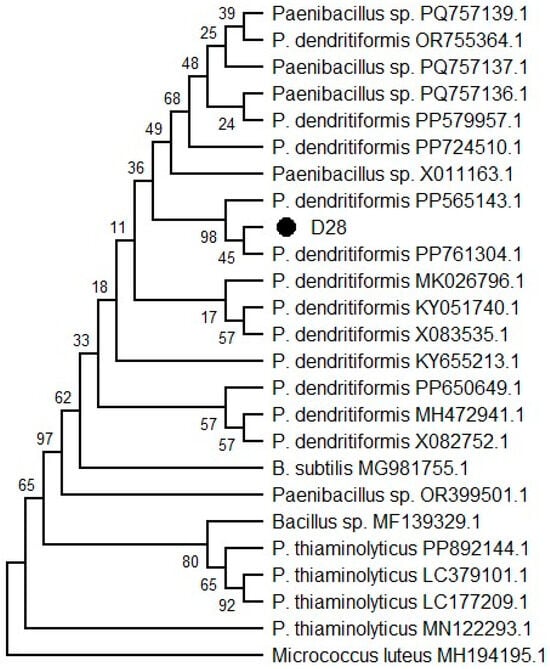

The D28 isolate was positioned within the clade corresponding to P. dendritiformis, clustering with the nucleotide sequence of the reference strain P. dendritiformis PP565143.1 with a high bootstrap support value (98%). This result confirms that D28 shares a recent common ancestor with previously described strains of P. dendritiformis. The clade containing D28 was clearly differentiated from other members of the genus Paenibacillus, as well as from Bacillus subtilis and P. thiaminolyticus, which formed distinct outgroups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of D28 isolate using the neighbor-joining method. The optimal tree is shown with a total branch length of 0.355. The analysis was performed in MEGA 12. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates).

3.2. Plant Growth Promotion Trials

The strain analyzed in this study was found to be positive for nitrogen fixation. P. dendritiformis showed the ability to solubilize phosphate (ISP = 1.95). Additionally, produced 0.306 µg mL−1 of IAA. No favorable results were observed for biocontrol activity, either by direct contact or through VOCs, in both the test strain and the control strain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the evaluation of plant growth promoting characteristics.

3.3. Physiological Tolerance

Table 3 shows the results of the evaluation of tolerance to extreme environmental conditions for P. dendritiformis and B. megaterium. Regarding temperature, P. dendritiformis can grow between 30 °C and 45 °C, whereas B. megaterium grows only up to 35 °C. In terms of growth at different pH levels (Table 3), the results indicate that P. dendritiformis is unable to grow at pH values below 3.0 or above 10.0. However, it can grow within a range of pH 4.0 to 9.0, forming colonies with regular size, shape, and appearance. In contrast, B. megaterium grows only within a narrower pH range of 6.0 to 9.0. With respect to saline tolerance (Table 3), P. dendritiformis was able to grow in NaCl concentrations ranging from 0.25 mol·L−1 to 2.5 mol·L−1, but its growth was inhibited at 3.0 mol·L−1. On the other hand, B. megaterium only grew in the range of 0.25 to 0.50 mol·L−1.

Table 3.

Tolerance to extreme environments.

3.4. In Vitro Vigor Test

After seven days of sowing (Table 4), no statistical differences (p < 0.05) were found for the variables germination percentage (GP), coleoptile length, and number of adventitious roots. Primary root length was statistically greater (p < 0.05) in seedlings inoculated with P. dendritiformis (13.85 ± 3.16 cm) compared with the B. megaterium treatment (13.60 ± 3.11 cm) and the uninoculated seeds (13.85 ± 3.16 cm). The Cohen’s d statistic for this variable indicates that the effects can be considered small. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) were also observed in the number of root hairs between the P. dendritiformis treatment and the control; in this case, Cohen’s d indicates that, relative to the uninoculated seeds, P. dendritiformis produces a mediums size effect, and the same applies to Cohen’s group 2.

Table 4.

Vigor variables in vitro seven days after sowing.

In Table 5, the in vitro vigor results at 14 days after sowing are presented. Statistical differences were found for the evaluated variables (p < 0.05). The length of the main leaf was greater in the treatments with P. dendritiformis and B. megaterium compared with the uninoculated seed. Cohen’s d for group 1 indicates a large effect of the treatment and shows no difference in effect size between P. dendritiformis and the positive control B. megaterium. A larger leaf area in the main leaf was also observed in the treatment with P. dendritiformis compared with plants from uninoculated seeds, which was confirmed by the Cohen’s d value, showing an effect like that of the positive control.

Table 5.

Vigor variables in vitro at 14 days after sowing.

Likewise, the treatment inoculated with P. dendritiformis produced a greater number of leaves, followed by the treatment with B. megaterium, and finally the uninoculated seed. Seedlings also exhibited a greater total leaf area in the treatments with P. dendritiformis and B. megaterium than in the uninoculated seed.

Regarding shoot dry weight, the treatments with P. dendritiformis and B. megaterium were superior. The treatment with P. dendritiformis showed a large Cohen’s d effect size compared with the uninoculated treatment and exceeded the positive control with a medium effect size. For the root dry matter fraction, the treatment with P. dendritiformis did not show statistical differences compared to the B. megaterium treatment, consistent with the low effect size indicated by Cohen’s d. In contrast, the results for seedlings from uninoculated seeds showed differences between means (p < 0.05) and a large effect size according to Cohen’s d.

4. Discussion

The behavior of a plant’s biometric variables serves as an indicator of the favorable or unfavorable conditions under which it develops [53]. The biological ability of bacteria to fix atmospheric N2 can reduce the need for nitrogen fertilizers and may also delay nitrogen remobilization in maize plants, thereby increasing crop yield [54]. According to Aquino [55], inoculation with nitrogen-fixing bacteria increases growth and nitrogen fixation in maize and enhances the plant’s capacity to convert nitrate or ammonium into other metabolites required for development.

The ISP value obtained indicates a low phosphate-solubilization capacity [39]. In soil, phosphorus typically forms insoluble calcium phosphates, limiting its availability to plants. There is also a negative correlation between pH and soluble phosphorus; however, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria enhances phosphorus uptake through the release of organic acids [56]. The production of 0.306 μg/mL of IAA is comparable to the values reported by Freitas [57] for B. subtilis, a species widely recognized as a PGPR [58]. The B. megaterium strain used as a control in this study—reported in several works as a prominent PGPR [31,32,33,34]—showed ISP and IAA values like those obtained with the P. dendritiformis strain. These results agree with Pal [59], who isolated endophytic P. dendritiformis from maize.

Although members of the same genus or species have been described as biocontrol agents, the strain in this study did not show antagonistic activity in the assays performed. This may be due to the common intraspecific variability observed among bacteria of the same genus [60], the absence of nutrient-competition conditions required to activate antagonistic mechanisms [61], or differences in temperature and soil characteristics where it developed affecting biocontrol expression [62]. Furthermore, Besset-Manzoni [62] notes that not all strains with antifungal activity perform well as PGPB, and strains lacking biocontrol activity are often discarded despite having other functional plant-growth-promoting traits.

Beyond its plant growth-promoting properties, the P. dendritiformis strain exhibited additional physiological traits of interest. There is increasing interest in microorganisms capable of growing at high temperatures, as they may produce thermostable enzymes with biotechnological applications and represent a viable alternative to withstand agricultural challenges associated with climate change [63]. The survival of some bacteria at different temperatures may be related to their ability to adjust membrane lipid composition by modifying the proportion of saturated and long-chain fatty acids to maintain membrane functionality [64].

The ability of P. dendritiformis to grow across different pH levels is biotechnologically relevant, since soil pH directly imposes physiological constraints on bacterial communities and indirectly affects nutrient availability, nitrogen transformation, and the expression of functional nitrogen-cycle genes [65]. Although this study did not include metabolic tests to determine the adaptation mechanisms of this strain, the literature describes several survival strategies in acidic environments, such as proton pumping via F1-F0-ATPase, the glutamate decarboxylase system, formation of an ammonium protection cloud, high cytoplasmic urease activity, macromolecule repair, and biofilm formation [66]. Species tolerant to a broad pH range show higher survival rates in biotechnological applications. Thus, bacteria with plant growth-promoting ability and tolerance to wide pH ranges have strong potential for agricultural use [67].

With respect to saline environments, salt stress reduces microbial diversity and threatens agricultural production worldwide [68]. Salinity restricts plant growth by limiting nutrient mobilization, generating hormonal imbalances, producing reactive oxygen species, and causing ionic toxicity and osmotic stress [69]. PGPR capable of growing under saline conditions may confer salt tolerance by releasing osmoprotective organic compounds that modify the rhizosphere and act as signaling molecules [70]. The use of salinity-resistant PGPR also promotes plant growth through ACC-deaminase activity and the synthesis of IAA, GA, ABA, and cytokinins [71]. Some PGPR can even induce halotolerance genes in plants [72].

In addition to the potential of P. dendritiformis as a PGPR, its thermotolerance, broad pH tolerance, and ability to grow under saline conditions highlight its potential for industrial, bioremediation, and biodegradation applications, particularly if bioactive compounds such as extremozymes and other metabolites of interest are identified [73,74,75]. These characteristics may be associated with the evolutionary adaptations of P. dendritiformis to the extreme environment from which it was isolated, as microorganisms from such settings develop genetic and physiological mechanisms driven by selective pressures that result in distinctive traits in membrane composition, cellular structures, enzymes, pigments, antioxidants, vitamins, proteins, and alkaloids [14,15,16].

The behavior of plant biometric variables reflects the favorable or unfavorable conditions under which plants develop [53]. The low effect sizes observed at seven days for both P. dendritiformis and B. megaterium may be attributed to the short duration and nature of the experiment. However, even when these effects are small, it is still possible to identify a PGPB-type response, which can be explained by the use of maize root exudates by the bacteria to produce hormones that stimulate the formation of root hairs in the meristematic zone, thereby increasing the surface area available for water and nutrient uptake [76,77].

At 14 days after sowing, and under infertile soil conditions, P. dendritiformis exhibited greater effect sizes compared with both the uninoculated control and the positive control, providing clear evidence of its capabilities as a PGPB. In this regard, Amezquita-Avilés [78] reported that an increase in leaf number is a clear indicator of plant growth promotion. Likewise, the increase in main leaf length, leaf area, and dry weight can be attributed to phytohormone production. Similarly, a larger leaf area enhances photosynthetic capacity and dry matter accumulation [76].

In another study, results like those obtained in the present work were reported for P. dendritiformis. The bacterium increased germination percentage, shoot length, fresh and dry weight, leaf area, root number, root length, and root fresh and dry weight compared with the negative control. Moreover, it restored seedling growth by improving both root and shoot development compared with uninoculated controls [53].

5. Conclusions

The P. dendritiformis strain demonstrated the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen and produce indole-3-acetic acid (IAA); however, it showed low efficiency in phosphate solubilization and did not exhibit antagonistic activity against phytopathogens in this study. Nevertheless, it promoted maize growth under laboratory conditions. Its tolerance to variations in pH, salinity, and temperature suggests a capacity to adapt to extreme or limiting environments, which often restrict crop development and productivity. These results indicate its potential as a PGPB in maize grown in poor or nutrient-deficient soils, although field evaluations will be necessary to confirm its effectiveness.

Furthermore, the survival of P. dendritiformis under different pH and salinity conditions points to broader biotechnological potential. Future research should focus on exploring its ability to produce thermostable and stress-resistant enzymes, which could have applications in industry, bioremediation, and biodegradation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N.R.-V., J.A.C.-S., I.A.O.-S. and J.P.C.-M.; methodology, J.P.C.-M.; validation, J.N.R.-V., J.A.C.-S., G.A.P.C., I.A.O.-S., J.P.C.-M., R.J.O. and J.H.G. formal analysis, J.A.C.-S.; investigation, J.N.R.-V. and J.P.C.-M.; resources, J.N.R.-V., J.A.C.-S., G.A.P.C., I.A.O.-S., J.P.C.-M. and R.J.O.; data curation, J.R.G.T. and J.N.R.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N.R.-V.; writing—review and editing, J.N.R.-V., J.A.C.-S., I.A.O.-S., J.P.C.-M., G.A.P.C., J.R.G.T., R.J.O. and J.H.G.; visualization, G.A.P.C.; supervision, J.A.C.-S., I.A.O.-S. and J.P.C.-M.; project administration, I.A.O.-S. and J.H.G.; funding acquisition, I.A.O.-S. and J.H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is a product of the project “Improvement of Degraded Soils through the Use of an Extremophilic Microorganism”, funded by the Federal Technological Institutes and Centers under the 2024 Call for Scientific Research, Technological Development, and Innovation Projects. Project code: 20428.24-P.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to the Laboratorio de Biotecnología of the Unidad de Posgrado, Investigación y Desarrollo Tecnológico del Instituto Tecnológico de Durango for providing the Bacillus megaterium strain. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, Z.; Yang, R.; Wang, J.; Zhou, P.; Gong, Y.; Gao, F.; Wang, C. Effects of Nutrient Deficiency on Crop Yield and Soil Nutrients Under Winter Wheat–Summer Maize Rotation System in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Q.; Gao, X. Conservation and Dynamics of Maize Seed Endophytic Bacteria Across Progeny Transmission. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera (SIAP). Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola; Dirección General del Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera: Mexico City, Mexico, 2025.

- Govaerts, B.; Chávez, X.; Fernández, A.; Vega, D.; Vázquez, O.; Pérez, M.; Carvajal, A.; Ortega, P.; López, P.; Rodríguez, R.; et al. Maíz para México. Plan Estratégico 2030; CIMMYT: Texcoco, Mexico, 2019; 144p. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Reyes, B.M.; Rodríguez-Palacio, M.C.; Castilla-Hernández, P.; Sánchez-Robles, J.; Vela-Correa, G.; Schettino-Bermúdez, B. Uso potencial de cianobacterias como biofertilizante para el cultivo de maíz azul en la Ciudad de México. Rev. Latinoam. Biotecnol. Ambient. Algal 2019, 10, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Jha, D.K. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): Emergence in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1327–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, B.; Khan, A.; Tariq, M.; Ramzan, M.; Iqbal Khan, M.S.; Shahid, N.; Aaliya, K. Bottlenecks in commercialization and future prospects of PGPR. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 121, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, D.; Thakker, J.N.; Dhandhukia, P.C. Portraying mechanics of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1127500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Hossen, F.A.; Ismail, M.R.; Hoque, A.; Islam, M.Z.; Shahidullah, S.M.; Meon, S. Efficiency of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) for the enhancement of rice growth. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar]

- De Andrade, L.A.; Santos, C.H.B.; Frezarin, E.T.; Sales, L.R.; Rigobelo, E.C. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Agricultural Production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Luna, J.; Arroyo-Herrera, I.; Bahena-Osorio, Y.; Román-Ponce, B.; Soledad Vásquez-Murrieta, M. Suelos salinos: Fuente de microorganismos halófilos asociados a plantas y resistentes a metales. Alianzas Tend.-BUAP 2020, 5, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murialdo, R.; Daga, I.C.; Pesci, H.; Palmero, F.; Hang, S. Evaluación del uso de cianobacterias nativas como biofertilizantes en cultivos de Zea mays L. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Exactas Fís. Nat. 2022, 9, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Oliart-Ros, R.M.; Manresa-Presas, Á.; Sánchez-Otero, M.G. Utilization of Microorganisms from extreme environments and their products in biotechnological development. CienciaUAT 2016, 11, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzures, M.; Gaytán, M.; Cuna, E. Algas extremófilas: Estrategias de supervivencia y uso potencial. BioTecnología 2021, 25, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.; Núñez-Montero, K.; Lamilla, C.; Pavez, M.; Quezada-Solís, D.; Barrientos, L. Antifungal activity screening of antarctic actinobacteria against phytopathogenic fungi. Acta Biol. Colomb. 2020, 25, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Bose, S.K.; Park, K.-I.; Dufossé, L.; Fouillaud, M. Plant-Microbe Interactions under the Extreme Habitats and Their Potential Applications. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, G.; Orlando, J.; Zuñiga-Feest, A. Plants colonizing volcanic deposits: Root adaptations and effects on rhizosphere Microorganisms. Plant Soil. 2021, 461, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Reyes, A.; Gonzalez-Lozano, K.J.; Cabral-Miramontes, J.P.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, J.J.; Rios-Sosa, A.; Alvarez-Gutierrez, P.E.; Mireles-Torres, S.P.; Batista-García, R.A.; Arechiga-Carvajal, E.T. Exploration of Plant and Microbial Life at “El Chichonal” Volcano with a Sustainable Agriculture Prospection. Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Molina, C.I.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Aguirre-Noyola, J.L.; Manzano-Gómez, L.A.; Zenteno-Rojas, A.; Rogel, M.A.; Rincón-Molina, F.A.; Ruíz-Valdiviezo, V.M.; Rincón-Rosales, R. Bacterial Community with Plant Growth-Promoting Potential Associated to Pioneer Plants from an Active Mexican Volcanic Complex. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pecoraro, L. Analysis of Soil Fungal and Bacterial Communities in Tianchi Volcano Crater, Northeast China. Life 2021, 11, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Ocaña, B.A.; Velázquez-Ríos, I.O.; Alcántara-Hernández, R.J.; Ovando-Ovando, C.I.; Rincón-Rosales, R.; Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A.; González-Terreros, E.; Ruíz-Valdiviezo, V.M. Changes in the Concentration of Trace Elements and Heavy Metals in El Chichón Crater Lake Active Volcano. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaresan, N.; Kumar, K.; Sureshbabu, K.; Madhuri, K. Plant Growth-Promoting Potential of Bacteria Isolated from Active Volcano Sites of Barren Island, India. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, G.; Di Stasio, L.; Vigliotta, G.; Guarino, F.; Cicatelli, A.; Castiglione, S. Exploring the Potential of Four Novel Halotolerant Bacterial Strains as Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) under Saline Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Bisht, N.; Ansari, M.M.; Mishra, S.K.; Chauhan, P.S. Paenibacillus lentimorbus Alleviates Nutrient Deficiency-Induced Stress in Zea mays by Modulating Root System Architecture, Auxin Signaling, and Metabolic Pathways. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.D.; Cavalcanti, M.I.P.; Correia, A.D.; Escobar, I.E.C.; de Freitas, D.S.; Nobrega, R.S.A.; Fernandes-Júnior, P.I. Maize-associated bacteria from the Brazilian semiarid region boost plant growth and grain yield. Symbiosis 2021, 83, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrada, M.R.; Villanueva, D.J.Q.; Cuevas, C.V.M.; Ruíz, M.C.V. Efecto de la aplicación de microorganismos fijadores de nitrógeno en el desarrollo del cultivo de maíz (Zea mays L.). Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. 2024, 17, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, N.; Mishra, V.; Sharma, M.; Das, M.K.; Ahaluwalia, K.; Sharma, R.S. Evaluation of functional diversity in rhizobacterial taxa of a wild grass (Saccharum ravennae) colonizing abandoned fly ash dumps in Delhi urban ecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezza, F.A.; Chirwa, E.M.N. Biosurfactant from Paenibacillus dendritiformis and its application in assisting polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) and motor oil sludge removal from contaminated soil and sand media. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2015, 98, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamdain, L.; Fahmy, F.; Lari, S.; Aly, M. Characterization of some Bacillus strains obtained from marine habitats using different taxonomical methods. Life Sci. J. 2015, 12, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Amoudi, S.; Essack, M.; Simões, M.F.; Bougouffa, S.; Soloviev, I.; Archer, J.A.C.; Lafi, F.F.; Bajic, V.B. Bioprospecting Red Sea Coastal Ecosystems for Culturable Microorganisms and Their Antimicrobial Potential. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.A.; Kadhum, A.A.; Ali, A.F.; Saleh, U.N.; Jassim, N.H.; Hamad, A.R.; Hassan, A.F. Response of cucumber plants to PGPR bacteria (Azospirillum brasilense, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus megaterium) and bread yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2021, 12, 969–975. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, U.; Yasmin, H.; Hassan, M.N.; Naz, R.; Nosheen, A.; Sajjad, M.; Ilyas, N.; Keyani, R.; Jabeen, Z.; Mumtaz, S.; et al. Drought-tolerant Bacillus megaterium isolated from semi-arid conditions induces systemic tolerance of wheat under drought conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Moreno, J.; García-Ortega, L.F.; Torres-Saucedo, L.; Rivas-Noriega, P.; Ramírez-Santoyo, R.M.; Sánchez-Calderón, L.; Vidales-Rodríguez, L.E. Bacillus megaterium HgT21: A promising metal multiresistant plant growth-promoting bacteria for soil biorestoration. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00656-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, E.; Şekerci, A.D.; Yılmaz, S.; Yetişir, H. Field trial of PGPR, Bacillus megaterium E-U2-1, on some vegetable species. J. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2023, 17, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, S.; Feil, H.; Copeland, A. Bacterial Genomic DNA Isolation Using CTAB. Sigma, 50(6876). Available online: https://jgi.doe.gov/ (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC): A resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.L.; Barrett, T.; Benson, D.A.; Bryant, S.H.; Canese, K.; Chetvernin, V.; Church, D.M.; DiCuccio, M.; Edgar, R.; Federhen, S.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D5–D12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 12 for adaptative green computing. across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, B.D.; Bonatelli, M.L.; Quecine, M.C. Fast screening of bacteria for plant growth promoting traits. In The Plant Microbiome: Methods and Protocols; Carvalhais, L.C., Dennis, P.G., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2232, pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trail, F.; Common, R. Perithecial development by Gibberella zeae: A light microscopy study. Mycologia 2000, 92, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncero, M.I.; Hera, C.; Ruiz-Rubio, M.; Maceira, F.I.; Madrid, M.P.; Caracuel, Z.; Calero, F.; Delgado-Jarana, J.; Roldán-Rodríguez, R.; Martínez-Rocha, A.L.; et al. Fusarium as a model for studying virulence in soilborne plant pathogens. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2003, 62, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K. Molecular phylogeny of the Nectria haematococca-Fusarium solani species complex. Mycologia 2000, 92, 919–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Miramontes, J.P.; Martínez-Rocha, A.L.; Rosales-Castro, M.; López-Rodríguez, A.; Meneses-Morales, I.; Del Campo-Quinteros, E.; Herrera-Ocelotl, K.K.; Gandara-Moreno, G.; Velázquez-Huizar, S.J.; Ibarra-Sánchez, L.; et al. Antifungal Activity of Mexican Oregano (Lippia graveolens Kunth) Extracts from Industrial Waste Residues on Fusarium spp. in Bean Seeds (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agriculture 2024, 14, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñafiel-Jaramillo, M.; Torres-Navarrete, E.; Barrera-Álvarez, A.E.; Prieto-Encalada, H.G.; Morante-Carriel, J.A.; Canchignia-Martínez, H.F. Producción de ácido indol-3-acético por Pseudomonas veronii R4 y formación de raíces en hojas de vid “Thompson seedless” in vitro. Cien. Tecnol. 2016, 9, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudpour, Y.; Schmidt, M.; Calabrese, F.; Richnow, H.H.; Musat, N. High resolution microscopy to evaluate the efficiency of surface sterilization of Zea Mays seeds. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Zhao, B.; Sun, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Ma, C.; Zhang, J. Effects of Bacillus subtilis HS5B5 on Maize Seed Germination and Seedling Growth under NaCl Stress Conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubian, I.; Msimbira, L.A.; Smith, D.L. Cell-Free Supernatant of Bacillus Strains can Improve Seed Vigor Index of Corn (Zea mays L.) Under Salinity Stress. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 857643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). NOM-021-RECNAT-2000. Que Establece las Especificaciones de Fertilidad, Salinidad y Clasificación de Suelos. Estudios, MUESTREO y análisis; Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, Mexico, 2002.

- Gong, M.; Kong, M.; Huo, Q.; He, J.; He, J.; Yan, Z.; Lu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Song, J.; Han, W.; et al. Ultrasonic treatment can improve maize seed germination and abiotic stress resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Media Cybernetics. Image-Pro Plus Software, Version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc.: Rockville, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Lakens, D. Calculating and Reporting Effect Sizes to Facilitate Cumulative Science: A Practical Primer for t-Tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Estrada, P.; Piña-Guzmán, A.B.; Álvarez-Bernal, D.; Franco-Hernández, M.O.; Robles-Martínez, F. Potencial de Chlorophytum comosum para la Remediación de Suelos Contaminados con Glifosato. Terra Latinoam. 2025, 43, e2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, K.B.; Othman, R.; Abdul Rahim, K.; Shamsuddin, Z.H. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation to enhance vegetative growth, nitrogen fixation and nitrogen remobilisation of maize under greenhouse conditions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, J.P.A.; Antunes, J.E.L.; Bonifácio, A.; Rocha, S.M.B.; Amorim, M.R.; Alcântara Neto, F.; Araujo, A.S.F. Plant growth-promoting bacteria improve growth and nitrogen metabolism in maize and sorghum. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2021, 33, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Bhardwaj, P.; Pandey, S.S.; Kumar, S. Arnebia euchroma, a Plant Species of Cold Desert in the Himalayas, Harbors Beneficial Cultivable Endophytes in Roots and Leaves. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 696667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.J.A.; Braga Junior, G.M.; Afonso, L.C.; Martins, A.L.L.; Souza, M.C.; Chagas, L.F.B. Bacillus subtilis as a vegetable growth promoter inoculant in soybean. Divers. J. 2022, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H. Biostimulant and Beyond: Bacillus spp., the Important Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)-Based Biostimulant for Sustainable Agriculture. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 9, 1465–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, G.; Kumar, K.; Verma, A.; Verma, S.K. Seed inhabiting bacterial endophytes of maize promote seedling establishment and provide protection against fungal disease. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 255, 126926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.W.K.; Yam, J.K.H.; Mukherjee, M.; Periasamy, S.; Steinberg, P.D.; Kjelleberg, S.; Rice, S.A. Interspecific Diversity Reduces and Functionally Substitutes for Intraspecific Variation in Biofilm Communities. ISME J. 2016, 10, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaterra, A.; Badosa, E.; Daranas, N.; Francés, J.; Roselló, G.; Montesinos, E. Bacteria as Biological Control Agents of Plant Diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besset-Manzoni, Y.; Joly, P.; Brutel, A.; Gerin, F.; Soudière, O.; Langin, T.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Does In Vitro Selection of Biocontrol Agents Guarantee Success in Planta? A Study Case of Wheat Protection against Fusarium Seedling Blight by Soil Bacteria. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuesta-Popolizio, D.A.; Velázquez-Fernández, J.B.; Rodríguez-Campos, J.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M. Isolation and Identification of Extremophilic Bacteria with Potential as Plant Growth Promoters (PGPB) of A Geothermal Site: A Case Study. Geomicrobiol. J. 2021, 38, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, Y. Thermal Adaptation of the Archaeal and Bacterial Lipid Membranes. Archaea 2012, 2012, 789652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; He, X.; Gao, N.; Li, Q.; Qiu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Shen, W. Soil pH Amendment Alters the Abundance, Diversity, and Composition of Microbial Communities in Two Contrasting Agricultural Soils. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e04165-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Lin, Z.; Xu, P. Mechanisms of Acid Tolerance in Bacteria and Prospects in Biotechnology and Bioremediation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumari, M.; Swarupa, P. Characterization of pH dependent growth response of agriculturally important microbes for development of plant growth promoting bacterial consortium. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, A.; Wan, W.; Luo, X.; Zheng, L.; He, G.; Huang, D.; Chen, W.; Huang, Q. High Salinity Inhibits Soil Bacterial Community Mediating Nitrogen Cycling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e01366-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Gaurav, A.K.; Srivastava, S.; Verma, J.P. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Biological tools for the mitigation of salinity stress in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilev, S. Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria Mitigating Soil Salinity Stress in Plants. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, K.K.; Dandge, P.B. Mitigation of salinity stress in plants using plant growth promoting bacteria. Symbiosis 2019, 79, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh-Nasrabadi, S.M.; Mohammadiapanah, F.; Hosseini-Mazinani, M.; Sarikhan, S. Salinity stress endurance of the plants with the aid of bacterial genes. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1049608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofighi, A.; Mazaheri Assadi, M.; Asadirad, M.H.A.; Zare Karizi, S. Bio-ethanol production by a novel autochthonous thermo-tolerant yeast isolated from wastewater. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Chakraborty, A.P.; Chakraborty, R. Understanding the potential of root microbiome influencing salt-tolerance in plants and mechanisms involved at the transcriptional and translational level. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 1657–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Yáñez, J.M.; López Ayala, I.Y.; Villegas Moreno, J.; Montaño Arias, N.M. Maize responds to Azotobacter sp and Burkholderia sp inoculation at reduced dose of nitrogen fertilizer. Sci. Agropecu. 2014, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Robles, M.Á.; González-Salas, U.; Rodríguez-Sifuentes, L.; Mendoza-Retana, S.S.; Sánchez-Lucio, R.; García-de la Paz, N.C. Potencial de Bacillus nativos de la Comarca Lagunera como biofertilizante en la producción de maíz forrajero. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2022, 13, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ceja, M.G.; Loeza-Lara, P.D.; Carballar-Hernández, S.; Jiménez-Mejía, R.; Medina-Estrada, R.I. Aislamiento de bacterias nativas con potencial en la promoción del crecimiento de maíz criollo mexicano (Zea mays L.). Biotecnia 2023, 26, e2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amezquita Aviles, C.F.; Coronel Acosta, C.B.; de los Santos Villalobos, S.; Santoyo, G.; Parra Cota, F.I. Characterization of native plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) and their effect on the development of maize (Zea mays L.). Biotecnia 2022, 24, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).