Abstract

Ecological stoichiometry offers critical insights into nutrient dynamics and soil–plant interactions in agroecosystems. To explore the effects of long-term fertilization on soil–cotton C, N, P stoichiometry and stoichiometric homeostasis in arid gray desert soils, this study was conducted at a national gray desert soil monitoring station in Xinjiang (87°28′27″ E, 43°56′32″ N, elevation: 595 m a.s.l.)—an arid and semi-arid region with an annual mean temperature of 5–8 °C and annual precipitation of 100–200 mm. Established in 1989, the 31-year experiment adopted a wheat–maize–cotton annual rotation system with six treatments: CK (control, no fertilizer), N (nitrogen fertilizer alone), NK (nitrogen + potassium fertilizer), NP (nitrogen + phosphorus fertilizer), PK (phosphorus + potassium fertilizer), and NPK (nitrogen + phosphorus + potassium fertilizer). Key results showed that balanced NPK fertilization significantly increased soil organic carbon (SOC) by 22.7% and soil total phosphorus (STP) by 48.6% compared to CK, while the N-only treatment elevated soil N:P to 3.2 (a 68.4% increase vs. CK), indicating severe phosphorus limitation. For cotton, NPK increased seed phosphorus content by 68.2% (vs. N treatment) but reduced straw carbon content by 10.2% (vs. PK treatment), reflecting a carbon allocation trade-off from vegetative to reproductive organs under nutrient sufficiency. Stoichiometric homeostasis differed between organs: seeds maintained stricter carbon regulation (1/H = −0.40) than straw (1/H = −0.64), while straw exhibited more plastic N:P ratios (1/H = 1.95), highlighting organ-specific adaptive strategies to nutrient supply. Redundancy analysis confirmed that soil available phosphorus (AP) was the primary driver of cotton P uptake and yield formation. The seed cotton yield of NPK (5796.9 kg ha−1) was 111.7% higher than CK, with NP (N-P co-application) achieving a 94.7% yield increase vs. CK—only 7.9% lower than NPK, whereas single N application showed the lowest straw yield (5995.0 kg ha−1) and limited yield improvement. These findings demonstrate that long-term balanced NPK fertilization optimizes soil C-N-P stoichiometric balance by enhancing SOC sequestration and phosphorus retention, regulating cotton organ-specific stoichiometric homeostasis, and promoting efficient nutrient uptake and assimilate translocation. The study confirms that phosphorus is the key limiting factor in arid gray desert soil cotton systems, and balanced NPK supply is essential to mitigate stoichiometric imbalances and sustain soil fertility and productivity. This provides targeted practical guidance for rational fertilization management in arid agroecosystems, emphasizing the need to prioritize phosphorus supply and avoid single-nutrient application to maximize resource use efficiency.

1. Introduction

Ecological stoichiometry is the science of studying the energy balance and the balance of multiple chemical elements (mainly C, N, and P) in biological systems [1], and it is also an emerging field of ecological research in recent years, which is a new direction in the field of ecology, biochemistry, and soil chemistry research, and it provides a new way of thinking for the study of soil–plant interactions and the cycle of C, N, and P [2,3,4]. The ecological and chemical significance of the ecological stoichiometry of homeostasis has been highly emphasized by scholars because this index reflects the physiological and biochemical adaptation of organisms to environmental changes, and its strength is related to the ecological strategies and adaptations of the species, but the results of the research in the field of agriculture are very limited.

Living organisms consist of more than 20 mostly irreplaceable elements, any one of which is the shortest supply relative to demand and could in principle be growth rate limiting, not only for plants but for all organisms [5]. The most basic components of organisms are the elements, especially C, N and P. The growth process of organisms is essentially a process of regulating the accumulation and relative proportions of these elements. Soil C:N:P can directly reflect soil fertility and indirectly reflect the nutritional status of plants and species composition of plant communities [6]. Plant C:N:P stoichiometry is strongly influenced by nutrient effectiveness and can be effective in showing C, N, and P cycling [5], controlling changes in plant functional types, climate, and anthropogenic disturbances [7]. Understanding the mechanisms by which soil C:N:P stoichiometry affects phosphorus transport can help to manage the paddy soils of these regions soil fertility under long-term fertilization [8].

Leaf acclimatization to N and phosphorus P deficiencies can be reflected in changes in leaf N:P stoichiometric ratios [9]. As such, N:P stoichiometry is widely recognized as one of the key indicators for diagnosing nutrient limitation in ecological stoichiometry research [10]. The theory of ecological stoichiometry suggests that the elemental composition ratio of an organism is dynamically stable, and that there exists a relatively stable relationship between the C, N, and P elemental ratios of an organism, while a great change in any one of these elements will cause this ratio to change [1]. Therefore, changes in the C:N:P ratio can be used to determine the type of element that limits the growth, development or reproduction of an organism [2]. Many studies have also shown that ecological stoichiometric ratios can effectively reflect the types of limiting elements [11,12]. Compared with forest soils, dryland soils have lower C content and a sharp increase in soil P content, which ultimately leads to lower C:N:P ratios [13]. Fertilization experiments involving different plant species have shown that, at the community level, N:P > 16 indicates P limitation, while N:P < 14 indicates N limitation [14]. For wetland plants, fertilization trials revealed that significant community changes occurred when P fertilizer was added at N:P > 20; in contrast, no significant changes were observed when N fertilizer was added alone or both N and P fertilizers were applied at N:P < 20, meaning N:P ratios could not reliably distinguish between N and P limitation under this condition [15]. Additionally, fertilization experiments conducted on the sheepgrass prairie in Inner Mongolia, China, indicated that N:P > 23 corresponds to P limitation, whereas N:P < 21 indicates N limitation [16]. Within the same plant community, species were differently N- or P-limited. P-limited species are found where N controls community biomass production and vice versa [14]. Currently, the judgment of limiting elements and nutrient use efficiency are the embodiment of the results of the application of ecological stoichiometry and many research results have been achieved [2]. The sensitivity and applicability of these nutrient limitation diagnostic indexes vary depending on the research object.

In addition, ecological stoichiometry homeostasis responds to physiological and biochemical adaptations of organisms to environmental changes [17,18], and its strength or weakness is related to ecological strategies and adaptations of the species [19], and the mechanism of adaptation of plants to limiting elements may be through their homeostasis to response; however, nutrient availability status and light intensity [20], fertilization [21], species, organs (above and below ground), stage of growth and development, and elements also affect the plant’s ecological stoichiometric internal stability [22]. For example, environmental conditions (e.g., nitrogen fertilizer addition) may alter the relationship between ecological stoichiometric homeostasis and ecosystem properties [23], but there is a paucity of research results in this area, which needs to be further explored.

Soils are the basis of ecosystems and their stoichiometric characteristics have important implications for ecosystem stability and function [24]. Changes in fertilization practices may lead to changes in nutrient contents and ratios in the soil, e.g., over-fertilization may lead to accumulation of certain nutrients in the soil, whereas lack of fertilization may lead to nutrient limitation [25], and these changes may affect plant growth and nutrient uptake capacity. Therefore, different fertilization practices over a long period of time may lead to changes in the ecological stoichiometric characteristics of soils and plants, which in turn may have implications for ecosystem stability and functioning. Nutrients are the main factor limiting high agricultural yields in the oasis of Xinjiang, and the effects of long-term fertilization on soil fertility and cotton production in cotton fields need to be further revealed.

Based on the above background, this study puts forward the following hypotheses: (1) the long-term use of different fertilization strategies will lead to significant differences in the content of C, N and P in the soil, which will significantly change the soil C, N and P stoichiometric ratio. (2) Dynamic changes in soil C, N and P stoichiometric ratios will directly affect the uptake and distribution of C, N and P during cotton growth. (3) Long-term fertilization will significantly change the stoichiometric homeostatic characteristics between different organs of cotton (such as seeds and straw) and the soil. (4) Soil nutrient limitation can be judged by plant tissue N:P ratios. Given that fertilization is the best method to test nutrient limitation [26], a long-term positional fertilization experiment set up in an irrigated agricultural area of gray desert soil on the northern slopes of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang Province, China, was chosen as the research object in this study to investigate the effects of long-term fertilization on the cotton–soil C, N, and P ecological stoichiometric characteristics and the internal homeostatic characteristics of cotton, which can help to diagnose the C, N, and P growth of the plant. The study aims to lay a theoretical foundation for the related research on carbon sequestration, emission reduction, fertilization and promotion of crop yield increase in farmland soils in the gray desert soil zone, and provide technical support for the screening of farmland management measures that are suitable for the sustainable development of agriculture in the zone and environmental friendliness.

2. Materials and Methods

Study sites and experimental design. The national gray desert soil fertility and fertilizer effectiveness monitoring station is located in the Xinjiang region (87°28′27″ E, 43°56′32″ N, elevation: 595 m a.s.l.) in the arid and semi-arid zone of northwestern China. The experimental site has a mean monthly air temperature ranging from −15 °C (January) to 25 °C (July), with an annual mean temperature of 5–8 °C. The mean monthly precipitation is 15 mm, concentrated in June–August, with an annual total of 100–200 mm. During the cotton growing season (April–October), the accumulated temperature ≥ 10 °C (a key indicator for crop growth) ranges from 2700 to 3600 °C∙d. Given the low precipitation, irrigation is essential for cotton production at the site. After 2009, the irrigation method was changed from furrow irrigation to drip irrigation, with a mean irrigation rate of 4500 m3 ha−1 per cultivation period (cotton growing season). Before 2009, the mean irrigation rate under furrow irrigation was 6000 m3 ha−1 per cultivation period. This combination of arid climate, abundant thermal resources, and optimized irrigation management forms the core environmental context for the long-term fertilization experiment. The basic physicochemical properties of the soil at the start of the experiment (1989) are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial physicochemical properties of the gray desert soil (1989).

The long-term fertilization experiment was established based on the soil nutrient status in Xinjiang and the nutrient requirements of the wheat–maize–cotton rotation system, with fertilizer application rates and treatment selection determined by previous soil test results, local agricultural practices, cumulative nutrient consumption characteristics of rotation crops, and local soil nutrient evolution trends. Rates were adjusted in 1995 (Table 2), and selected treatments included no fertilizer (CK), nitrogen fertilizer alone (N), nitrogen + potassium (NK), nitrogen + phosphorus (NP), phosphorus + potassium (PK), and nitrogen + phosphorus + potassium (NPK). Urea, diammonium phosphate (DAP), triple superphosphate (TSP, used only in PK), and potassium sulfate were adopted as N, P, and K fertilizers, respectively. Fertilizer application was split into basal and topdressing: 60% of total N and all P and K fertilizers were broadcast as basal fertilizer before spring sowing and incorporated via rotary tillage; the remaining 40% of N was applied as topdressing, with timings tailored to rotation crops—once at spring green-up and once at flowering for winter wheat, once at jointing and once at flowering for spring wheat, once by furrowing at the trumpet stage for maize, and once at budding and once at flowering for cotton.

Table 2.

The design of treatment and quantity of fertilization.

Crop ripening system in the region is annual; crop rotation is set for winter wheat, spring wheat (cotton), and corn; after 2009, the spring wheat season changed to cotton season, and at this time the irrigation method from the surface of the furrow irrigation began to change to pipeline drip irrigation; wheat planted on bare ground, cotton and corn planted using mulch, the year of sampling this study planted crops for cotton.

The plots were 468 m2 in size, without duplication. The plots were separated from each other by cement slabs, buried to a depth of 70 cm, with the surface exposed to 10 cm, to avoid mutual seepage of water and fertilizer leakage from the plots. Cotton was cultivated using a mechanical harvesting-oriented wide–narrow row planting pattern, which features alternating wide rows (66 cm) and narrow rows (10 cm) with a uniform plant spacing of 9 cm. This configuration results in a planting density of 270,000 plants ha−1, consistent with the high-density cultivation technology for machine-harvested cotton in arid regions of Xinjiang. At cotton maturity (October 2021, sampling season), yield determination was conducted via full-plot harvesting to ensure data accuracy. The straw and seed cotton yields of each treatment were recorded as follows: Straw yield ranged from 5995.0 ± 159.4 kg ha−1 (N treatment) to 8696.8 ± 96.1 kg ha−1 (NPK treatment), with CK (control), NP, NK, and PK treatments achieving 6889.9 ± 202.5, 7474.2 ± 232.3, 7469.2 ± 277.8, and 7275.6 ± 262.7 kg ha−1, respectively; seed cotton yield varied from 2738.8 ± 250.0 kg ha−1 (CK) to 5796.9 ± 304.4 kg ha−1 (NPK treatment), with corresponding values for N, NP, NK, and PK treatments of 3153.3 ± 226.0, 5334.3 ± 181.2, 3652.6 ± 86.4, and 3951.8 ± 255.0 kg ha−1.

Soil sampling and assays. Soil and plant samples were collected in October 2021 at cotton maturity. Each experimental treatment plot area was 468 m2 (13 × 36 m), since no independent replicate plots were designed at the beginning of the long-term experiment to better account for the differences in the plots, an adaptive sampling design was used, where each treatment area was equally divided into three pseudo-replicate plots of 156 m2 (13 × 12 m), and each pseudo-replicated area was sampled using the diagonal method to collect five 0–20 cm soil samples and plant samples of cotton, respectively, and then the five samples were combined to obtain three composite soil- and plant-replicated samples for each fertilization treatment. The soil was air dried and ground and sieved through 2 mm and 0.15 mm mesh, respectively, the plant samples were dried at 80 °C and pulverized and sieved through 0.5 mm mesh; the processed samples were well-mixed and packed in glass vials for testing and analysis.

Soil organic carbon content was determined by wet digestion with K2Cr2O7-H2SO4, soil total N and P content was determined by HClO4-H2SO4, and the samples were subjected to alkaline titration and colorimetric assay after digestion [27]. Plant C content was determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar, Hanau, Germany); N and P contents were determined by a molybdenum–antimony, colorimetric assay for plant samples after H2SO4-H2O2 digestion [27].

Calculating stoichiometric homeostasis coefficients. The stoichiometric homeostasis index is calculated according to the homeostasis model [1]: y = cx1/H, y is the elemental content and ratio of C, N, and P in different organs of the plant; x is the elemental content and ratio of C, N, and P in the soil in the environment; c is a constant, and H is the index of homeostasis. 1/H is the slope of the logarithmic linear relationship, which allows for quantification of the plant’s chemical stoichiometric homeostasis [28], as H is infinite for strictly homeostatic organisms, which poses many analytical problems. For statistical convenience, 1/H is mostly used to measure the strength of internal homeostasis [1,29].

According to the results of existing studies [28,30,31], the degree of homeostasis (1/H) of a species can be classified into five degrees, which are (1) 1/H ≤ 0, strict homeostatic; (2) 0 < 1/H ≤ 0.25, homeostatic; (3) 0.25 < 1/H ≤ 0.5, weakly homeostatic; (4) 0.5 < 1/H ≤ 0.75, weakly plastic; and (5) 1/H > 0.75, plastic.

Pearson correlation analysis (Correlate-Pearson) was used to determine soil–plant C, N, and P ecological stoichiometric correlations. Regression analysis was used to calculate the internal stability index between plant and soil.

Statistical analysis. Soil C:N, C:P, and N:P ratios were calculated from SOC, total N, and total P. Plant C:N, C:P, and N:P ratios were calculated from total C, total N, and total P. The data were analyzed by using the following methods. Data were processed and plotted using Microsoft Excel for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2411; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and OriginPro, Version 2021 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). All analyses were performed using SPSS, Version 21.0 software (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). We used one-way ANOVA followed by Least Significant Difference (LSD) test (p ≤ 0.05) for each variable to assess significant differences between the means of different treatments. Redundancy analysis (RDA), which identifies the relationship between environmental conditions and outcomes (i.e., the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable), has been widely used to address environmental and ecological problems [8,32], and therefore, we performed RDA using Canoco for Windows, Version 5.0 (Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, NY, USA)—a specialized tool for multivariate ecological data analysis—to identify the main drivers of nutrient changes in various cotton organs (e.g., seed total phosphorus, straw total carbon) that are mediated by soil properties (e.g., available phosphorus, pH, bulk density) under long-term different fertilization practices.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Different Fertilization Practices on Soil Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus

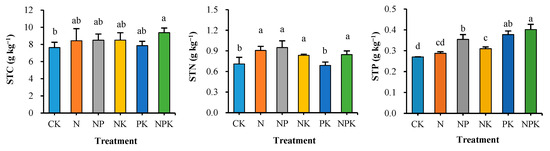

The effects of different fertilization measures on the distribution of soil organic carbon (SOC), soil total nitrogen (STN) and soil total phosphorus (STP) were significant (Figure 1). Long-term balanced fertilization (NPK) soil organic carbon was significantly higher than that of CK (p < 0.05), with an enhancement of 22.7%, and there was no significant change in biased application of chemical fertilizers. Soil total nitrogen content was significantly affected by whether or not nitrogen fertilizer was applied, and the total nitrogen content of 0.84–0.91 g kg−1 with nitrogen fertilizer (N, NP, NK, NPK) was significantly higher than that of PK and CK, and there was no significant difference between PK and CK. Soil total phosphorus content was significantly affected by the application of phosphorus fertilizer, and soil total phosphorus was significantly higher in the application of phosphorus fertilizer (NPK, NP, PK) than in the non-application of phosphorus fertilizer (NK, N) and CK, and the balanced application of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium was significantly higher than that of non-application of potassium (NP) among the phosphorus application treatments. The analysis showed that the balanced application of NP and PK synergistically enhanced soil C, N and P reservoirs, with STP (48.6%) > SOC increasing (22.7%) > STN (19.3%), reflecting that phosphorus was more likely to accumulate in the soil.

Figure 1.

Soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus contents of different fertilization treatments. Values are means + SD. Means with different letters are significantly different based on one-way ANOVA and LSD (p < 0.05, n = 3).

3.2. Characteristics of Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Accumulation in Cotton Under Different Fertilization Measures

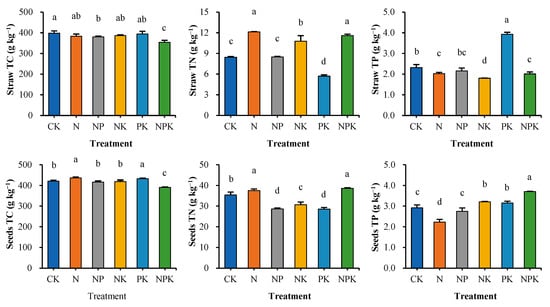

The analysis of the effects of different fertilization measures on total C, N and P content in cotton straw and seeds showed (Figure 2) that the total carbon content of straw in all treatments ranged from 353.9 to 398.6 g kg−1, with the NPK treatment significantly lower than the other treatments (p < 0.05). Among the partial fertilization treatments, nitrogen fertilizer alone (N) and phosphorus and potassium combination (PK) reached 383.2 g kg−1 and 394.5 g kg−1, respectively, which were 8.3–11.5% higher than the NPK treatment. Seed total carbon content (390.7–436.5 g kg−1) was significantly higher than that of straw. the NPK treatment (390.7 g kg−1) was 6.1–10.5% lower than the other treatments, whereas the N and PK treatments amounted to 10.5% and 9.7%, respectively, indicating that balanced fertilizer application may reduce carbon assimilation efficiency.

Figure 2.

Carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus content of cotton biomass in different fertilization treatments. Values are means + SD. Means with different letters are significantly different based on one-way ANOVA and LSD (p < 0.05, n = 3).

The total nitrogen content of cotton straw in different fertilization practices ranged from 5.7 to 12.1 g kg−1 and reached 11.6 g kg−1 and 12.1 g kg−1 in NPK and N treatments, respectively, which was significantly higher than that of CK (8.5 g kg−1) by 37.1–43.5%. The NK treatment (10.8 g kg−1) showed an intermediate state and its nitrogen accumulation in straw was significantly higher than that of PK treatment (5.7 g kg−1) by 88.9%. Seed total nitrogen content (28.6–38.6 g kg−1) was significantly higher than that of straw by 2.4–4.0 times. The NPK and N treatments amounted to 38.6 g kg−1 and 37.5 g kg−1, respectively, while the NK treatment (30.6 g kg−1) was 25.9% lower than that of the NPK treatment, indicating that phosphorus deficiency significantly inhibited nitrogen translocation.

The total phosphorus content of cotton stover in different fertilization practices ranged from 1.8 to 3.9 g kg−1 and was 95.0% higher in PK treatment (3.9 g kg−1) compared to NPK (2.0 g kg−1). The NP treatment (2.2 g kg−1) was significantly higher than NK (1.8 g kg−1) by 19.8% suggesting that excess of potassium may inhibit phosphorus storage. The total phosphorus of seeds in NPK treatment (3.7 g kg−1) was significantly higher than the other treatments, followed by NK and PK treatments (3.2 g kg−1), while N treatment (2.2 g kg−1) was 40.0% lower than NPK, indicating that balanced fertilization promotes phosphorus translocation to reproductive organs.

3.3. Changes in Soil Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Stoichiometric Ratios

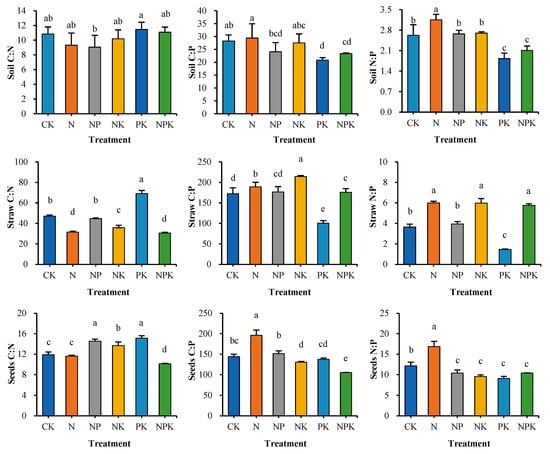

Under the conditions of long-term implementation of different fertilization measures, the inputs of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) nutrients to the soil showed obvious differentiation characteristics (Figure 3), and this difference became a key factor driving the dynamics of the soil N:P ratio. The results of the study showed that the soil N:P ratio under the nitrogen fertilizer (N) alone treatment was as high as 3.2, which was highly significant (p < 0.05) compared with the other treatments (1.8–2.7). No statistically significant differences in soil N:P ratios were found between the CK, NP, and NK treatments by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc multiple comparisons tests; however, soil N:P ratios were significantly (p < 0.05) higher under all three treatments than under PK and NPK treatments. Further comparisons revealed no significant differences in soil N:P ratios between PK and NPK treatments (p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus ratios of soil and cotton biomass in different fertilization treatments. Values are means + SD. Means with different letters are significantly different based on one-way ANOVA and LSD (p < 0.05, n = 3).

In terms of cotton straw N:P ratio, compared with no fertilizer (CK) treatment, single application of N, NK, and NPK treatments led to a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the cotton straw N:P ratio, whereas no nitrogen fertilizer treatment resulted in a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the N:P ratio. In a detailed comparison within the fertilizer treatment groups, the N:P ratio of cotton straw was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in N, NK, and NPK treatments alone than in NP and PK treatments (p < 0.05), and was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in NP than in PK treatments.

The analysis for cotton seed N:P ratio showed that the single application of nitrogen fertilizer (N) treatment was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than that of no fertilizer (CK) treatment; on the contrary, the cotton seed N:P ratios of the NP, NK, PK, and PK treatments were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than that of the CK treatment. A multiple comparison test revealed that there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in cotton seed N:P ratio between the four treatments: NP, NK, PK, and NPK.

In summary, the changes in soil and cotton N and P nutrients and their N:P ratios under different fertilization patterns over a long period of time indicate that fertilization strategies have a profound effect on nutrient cycling in the soil–plant system.

After systematic analysis, the average stoichiometric ratio of C, N, and P in the soil is 150:2.5:1, while the stoichiometric ratios in cotton seeds and straw are 140:11.1:1 and 161:4:1, respectively (Figure 4). Among the three system units (soil, seeds, and straw), the C:N:P ratio of straw is the most prominent. In Figure 3 and Figure 4, the C:N ratio of straw is the highest, which strongly indicates that carbon is relatively enriched in straw.

Figure 4.

Ternary plot of C:N:P (based on mass concentrations of C, N, and P elements) in soil, cotton seeds, and straw under different fertilization methods. Shapes represent different system units, and colors represent different experimental treatments.

3.4. Characteristics of Soil–Cotton Internal Stability After Long-Term Fertilization

The stoichiometric internal homeostatic characteristics between different organs (seeds and straw) and soil of cotton showed significant differences under long-term fertilization conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of stoichiometric homeostasis between long-term fertilized soil nitrogen and phosphorus and cotton.

In the seed–soil system, the carbon component exhibited strong internal steady-state properties (1/H = −0.40), with its power function relationship (y = 978.32x−0.399) having moderate explanatory power (R2 = 0.53). Notably, the 1/H value of the nitrogen-to-phosphorus (N:P) ratio was 0.83 (plastic), implying that the N:P composition of seeds is more dependent on soil availability than individual elements (N: homeostatic, 1/H = 0.12; P: weakly plastic, 1/H = 0.68). The C:N ratio had a homeostatic coefficient of 0.42. The anomalously high homeostatic coefficient (1/H = 1.89) mentioned previously for the C:N ratio actually corresponds to the straw–soil system, which may stem from the asynchrony between carbon assimilation and nitrogen uptake in cotton straw. This high C:N ratio (1/H = 1.89) aligns with the preferential carbon partitioning mechanism observed in global plants by Xu et al. [33].

The straw–soil system displayed distinct response patterns. The carbon component showed strong negative feedback regulation (1/H = −0.64), and its power function model (y = 1268.30x−0.564) had a highly significant goodness of fit (R2 = 0.92). The nitrogen component had a 1/H value of 1.45 (plastic), and its steep power function slope (y = 12.40x1.454) indicated that long-term fertilization significantly enhanced the sensitivity of straw nitrogen content in response to soil available nitrogen (R2 = 0.45). The high sensitivity of the N:P ratio (1/H = 1.95) further validated the N:P decoupling hypothesis [34], which suggests that global changes (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization) differentially regulate plant uptake efficiency of N and P, leading to an imbalance in their stoichiometric relationship. Additionally, long-term fertilization may exacerbate soil phosphorus limitation [35], further driving a plastic N:P response (1/H > 0.75) in straws, implying a key role for phosphorus redistribution mechanisms in vascular tissues.

It is worth noting that the C:P ratio in the seed–soil system (1/H = 0.80, weakly plastic) and the straw–soil system (1/H = 1.53, plastic) showed different plastic characteristics, suggesting that phosphorus use efficiency might be a key limiting factor in long-term fertilized cotton fields. Compared with the straw system, seeds exhibited stronger homeostatic regulation, which is consistent with the evolutionary adaptation theory for nutrient stabilization in plant reproductive organs [1].

3.5. Characterization of Ecological Stoichiometric Correlations of Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Soil–Cotton Systems

As can be seen in Figure 5, the soil–cotton system showed a multidimensional elemental coupling relationship: SOC showed a highly significant negative correlation with StC. STN showed a significant negative correlation with C:N, and STP showed a significant negative correlation with C:P, respectively. This implies that soil nutrient enrichment may reduce the coupling efficiency of C and corresponding elements (N for STN-related, P for STP-related). It is worth noting that SC:N was significantly negatively correlated with SN:P, while SC:P was significantly positively correlated with SN:P. This relationship may reflect that phosphorus effectiveness has a regulatory effect on the cycling of C and N in gray desert soils.

Figure 5.

Correlation diagram of soil–cotton carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus ecological stoichiometry. The numbers in the figure indicate the correlation coefficients, the size of the circle indicates the size of the correlation coefficient, the red indicates the positive correlation, and the green indicates the negative correlation; SOC: soil organic carbon; TN: total nitrogen; TP: total phosphorus; C:N: carbon-to-nitrogen ratio; C:P: carbon-to-phosphorus ratio; N:P: nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio; S: soil; Se: seed; St: straw.

Cotton seed C, N and P stoichiometric correlation analysis showed that Se TN was significantly negatively correlated with SeC:N, and SeTP was significantly negatively correlated with SeC:P, respectively. This indicates that when nutrients (N and P) are preferentially translocated to the seed, it results in a lower percentage of carbon-related metabolites in terms of the C:N and C:P ratios. SeC:P was significantly positively correlated with SeN:P. The significant positive correlation of SeC:P with SeN:P further confirms the central role of phosphorus in seed building, and this ratio can be used as a key indicator for phosphorus nutritional diagnosis.

Stoichiometric correlation analysis of C, N and P in cotton straw showed that StTN was significantly negatively correlated with StTP and highly significantly negatively correlated with StC:N. It was also highly significantly positively correlated with the StN:P ratio. This suggests that nitrogen accumulation inhibits phosphorus storage and drives the N:P ratio higher. The mechanism may be related to lowering the C:N ratio (i.e., elevating nitrogen content relative to carbon content). StTP was highly significantly positively correlated with StC:N and highly significantly negatively correlated with StC:P. This reflects that phosphorus accumulation may come at the expense of the efficiency of C and P metabolism in the straw. StC:N was significantly negatively correlated with StC:P and highly significantly negatively correlated with StN:P. StC:P was significantly positively correlated with StN:P. This may characterize the redistribution strategy of nutrients in the straw.

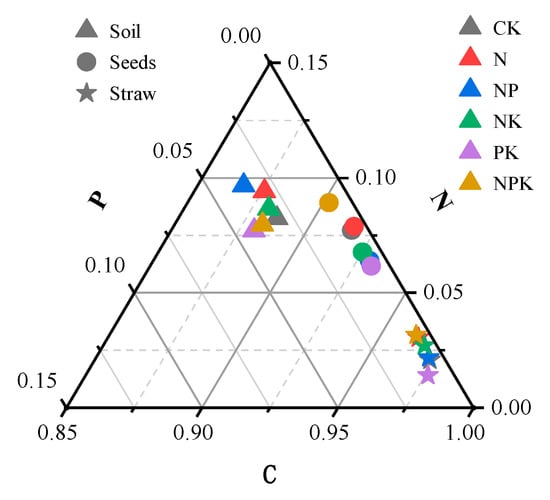

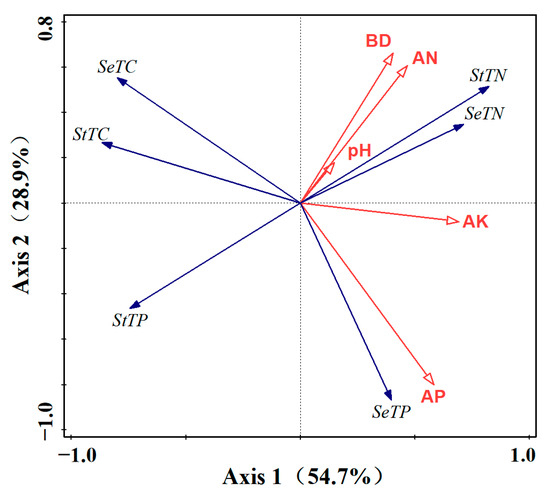

RDA combining soil physicochemical factors AN, AP, AK, pH, BD with cotton C, N and P showed (Figure 6) that the first sorting axis explained 54.7% of the variations, and the second sorting axis explained 28.9% of the variations, suggesting that the sorting axes better reflect the correlation of environmental factors related to cotton C, N and P content under different fertilizer application measures. The correlation of environmental factors related to cotton N, P and K content under different fertilization measures, cotton seed and straw C, N and P were obviously separated in both the first and second sorting axes, i.e., C, N and P in the cotton body changed significantly after the input of different fertilizer ratios into the soil. Soil effective phosphorus was the most influential environmental variable for cotton carbon nitrogen phosphorus and significantly affected cotton seed total phosphorus content. The C, N and P indexes of seeds and straw were significantly separated in the row order space, suggesting that different fertilization measures differentially regulate organ nutrient partitioning by altering soil physicochemical properties (e.g., AP, AN, pH).

Figure 6.

RDA between soil eco-balance properties and nutrients in cotton organs. The red arrow indicates the ecological balance of the soil, and the blue arrow indicates the concentration of nutrients in each organ. In the block diagram, SeTC: total seed carbon; SeTN: total seed nitrogen; SeTP: seed total phosphorus; StTC: straw total carbon; StTN: straw total nitrogen; StTP, straw total phosphorus; pH value; BD: volume density; AN: available nitrogen; AP: available phosphorus; AK: available potassium.

4. Discussion

4.1. On-Farm Fertilization Regimes Drive Changes in Soil–Crop Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Stoichiometry

Soil stoichiometry of C, N and P directly indicates soil fertility levels and indirectly reveals plant nutritional status [36,37]. However, it has been concluded that for different plant species, stoichiometric characteristics are not directly determined by soil nutrient content, but are more strongly influenced by the plants’ inherent genetic traits [38]. For the same plant, the growth rate theory suggests that the organism must change its C:N:P ratio in order for the growth rate to change. Therefore, the C, N and P contents and their mutual ratios (N:P, C:N and C:P) in plants can be utilized as an index to determine the adaptation of plant growth to nutrient supply [20,39]. Meanwhile, soil AN, TN and AP are potential determining variables affecting plant stoichiometric characteristics [40]. C, N and P elemental contents and their proportionality in agricultural soils and plants are affected by a variety of factors compared to natural ecosystems, including interference from long-term anthropogenic management practices, alteration in soil nutrient environments, and adaptive adjustments in crop biomass. Long-term fertilization, especially the biased application of chemical fertilizers, can significantly change soil organic carbon and nutrient levels, which in turn affects the stoichiometric ratio of soil C, N and P (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The average soil C:N:P ratio in this experiment was 11:1.1:1, which is relatively low and consistent with previous findings [13]. Compared with no fertilizer application (CK), fertilization significantly promoted the accumulation of SOC, but the effect of biased application of fertilizer was not as effective as balanced application of fertilizer, which may be due to the fact that the balanced application of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium fertilizers increased the amount of crop root stubble, which then increased the amount of root stubble carbon input, and ultimately increased the farmland soil organic carbon content, which in turn affects the soil C, N and P ratio. Agricultural management practices such as straw return and fertilization can increase exogenous C and N inputs, regulate soil nutrient availability, and thereby modulate agroecosystem productivity [41]. Additionally, fertilization-induced increases in plant N, P, and other nutrients may prompt plants to allocate more C to organismal construction [42], which in turn reduces the mass fraction of NSC (non-structural carbohydrate) in the body. Under the conditions of this study, the whole carbon content of cotton straw and seed with balanced application of N, P and K was significantly lower than that of other treatments, which may be the result of adequate nutrient supply, which improves the increase in cotton leaf area, plant height and bolls, which require the consumption of more carbohydrates. On the contrary, plants were shorter under the biased application of chemical fertilizers, and plants accumulated more NSC produced by photosynthesis. Through the analysis, it was found that the nitrogen and phosphorus contents in cotton tissues lack strict stoichiometric homeostasis (Table 3); without nitrogen or phosphorus, the soil nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency phenomenon is transmitted to the cotton straw and seeds, which in turn shows the decline in nitrogen or phosphorus in the cotton body, so it is manifested as a decline in the C:P ratio and the C:N ratio.

The sampling season’s (October 2021) yield data directly links long-term fertilization effects on soil–cotton stoichiometry to actual productivity. Compared to CK, NPK significantly increased straw yield by 26.2% and seed cotton yield by 111.7%, correlating with enhanced soil nutrient availability (SOC +22.7%, STP +48.6%) and optimized seed P uptake (+68.2% vs. N treatment). Notably, NP achieved the second-highest seed cotton yield, only 7.9% lower than NPK, confirming N-P co-application effectively alleviates nutrient limitation—consistent with AP being the primary driver of cotton P uptake. In contrast, the single N treatment had the lowest straw yield and relatively low seed cotton yield, attributed to severe P limitation (soil N:P = 3.2) inhibiting growth and nutrient assimilation. NK, PK, and NP all outperformed N and CK, highlighting nutrient co-application synergies. The seed cotton-to-straw ratio (S/S) reinforced this: NPK (0.67) and NP (0.71) had the highest S/S ratios, indicating enhanced assimilate translocation to reproductive organs—aligning with observed carbon allocation trade-offs and the link between stoichiometric balance and yield formation.

Our findings regarding the effects of long-term balanced fertilization on the carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) pools and their stoichiometric relationships in arid gray desert soils demonstrate significant regional specificity in both response magnitude and dominant mechanisms. Comparisons with recent studies conducted under different hydrothermal conditions and soil types indicate that the coupling effect of water and heat is the primary environmental factor regulating soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics [43]. Compared to the maximum SOC increase rate (approximately 1% per year) induced by chemical fertilization in a 35-year experiment on temperate fluvo-aquic soils in China [44], the annual increase rate of approximately 0.73% in our study is slightly lower. This could be attributed to the intense solar radiation and high soil temperatures in arid regions, which accelerate the mineralization of labile organic carbon in the surface layer [43]. It highlights that water availability is the key bottleneck limiting the maximum carbon sequestration potential under exogenous carbon input [45]. Meanwhile, in the calcareous alkaline environment, Ca2+-driven calcium carbonate precipitation can enhance the sequestration of deep soil inorganic carbon (SIC) [46], thereby reducing the accumulation of organic carbon in the plow layer.

Second, regarding soil total STP accumulation, the NPK treatment in this study resulted in an annual surge of 1.56% in STP, which is significantly higher than the 1.49% increase observed in paddy soils in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River [47]. This profoundly reveals the “low leaching and high retention” characteristics of soil P cycling in arid regions. The underlying mechanisms are not only related to P input from fertilization but also likely directly associated with the alkaline and calcareous environment of gray desert soils, which promote calcium phosphate precipitation [48]. Additionally, low-moisture conditions inhibit soil microbial activity and the transformation of P forms, leading to a slowdown in the bioavailable cycling rate of P. This study found that AP is the key factor driving cotton P uptake (Figure 6), further confirming that in arid irrigated agriculture, the chemical availability of P rather than its total pool size is often the direct limiting factor for crop responses—consistent with findings from other dryland agricultural systems.

Overall, in agroecosystems, long-term anthropogenic management practices, especially fertilization, have a significant impact on the contents and stoichiometric relationships of soil and plant C, N, and P. Appropriate fertilization strategies are essential for maintaining soil fertility, optimizing plant nutritional status, and regulating agroecosystem productivity. As a common soil amendment, fertilization can indeed improve soil fertility and crop yields, but it also affects soil biomass homeostasis. In particular, balanced fertilization exerts important effects on SOC content and cotton growth, underscoring the necessity of rational fertilization regimes to maximize benefits while mitigating unintended ecological impacts.

4.2. Association of Plant Tissue N:P Ratios with Soil Nutrient Limitation

There is a strong link between plant tissue N:P ratios and soil nutrient limitation, and this relationship has been thoroughly explored in numerous scientific studies. The nature of nutrient limitation can be initially determined by plant tissue N:P ratios [20,49], but there are also divergent views in the academic community [9,50,51]. It has been shown that functional differentiation of plant tissues leads to internal differences between nutrient ratios and stoichiometry [5], and that external supply rates of elements limit nutrient uptake [7]. This implies that judging the nature of nutrient limitation based on N:P ratios alone may be too one-sided.

Nutrient changes can significantly alter the equilibrium of plant ecological stoichiometric traits [52], and in the presence of soil nutrient imbalance, plants will adjust their N:P ratios to adapt to this nutrient imbalance in order to maintain normal growth and development. For example, when there is sufficient nitrogen in the soil but a lack of phosphorus, increased nitrogen application will cause plants to lower the N:P ratio to reduce nitrogen uptake and increase phosphorus uptake, and vice versa. This reflects the mechanism by which plants respond to environmental nutrients by altering their own N:P ratios to optimize the efficiency of resource use and to ensure that a certain level of growth and productivity is maintained despite nutrient-limited environments.

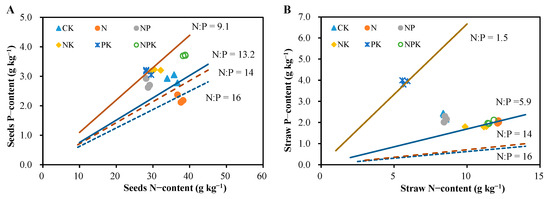

Based on the N:P ratio-based nutrient limitation diagnosis theory (dashed lines represent N:P = 14 and N:P = 16) [14], the cotton N:P ratios under different long-term fertilization treatments in this experiment exhibited distinct nutrient limitation patterns, but the present experiment did not seem to be quite applicable to the criterion of its delineation. For example, when cotton seed N:P = 14, NPK, NK, and NP treatments threw classified as nitrogen limitation (Figure 7A), and the results of straw N:P ratios showed that all treatments were nitrogen limitation (Figure 7B), which may also be due to the differences caused by different plant organs. For the purpose of this experiment, a cotton seed N:P ratio of 9.1/13.2 and a straw N P ratio of 1.5/5.9 should be more applicable as thresholds for determining NP limitation.

Figure 7.

Relationships between nitrogen and P content and nutrient-limiting properties of cotton in long-term fertilizer trials. The dashed lines indicate N and P mass ratios of 14 and 16, respectively [14], and the solid lines indicate the average N and P mass ratios under N and P-limited fertilization in this trial. (A): Nutrient limitation reflected by N and P contents in cotton seeds; (B): Nutrient limitation reflected by N and P contents in cotton straw.

Plant stoichiometric ratios do not fully reflect changes in soil N:P ratios [18]. Plant size, biomass and function are related to metabolic activity, structural organization distribution and its stoichiometric composition [7]. This warns us that we cannot rely solely on plant stoichiometric ratios to determine soil nutrient status. So how can we be more precise? Adopting a dynamic monitoring approach to track the changes in N and P requirements of plants at different growth stages can contribute to a better understanding of their growth limiting factors [53]. At the same time, the universality of N:P thresholds in determining nutrient limitation has been questioned [9,50,51]. Even if N:P ratios fall below known thresholds, plants may still experience co-limitation by N and P [50]. Additionally, critical N:P values for diagnosing N or P limitation vary among plant functional groups [54]. These findings confirm that the N:P threshold hypothesis carries a risk of distortion when identifying nutrient limitation types, with the 14/16 threshold exhibiting a higher distortion risk than the 10/20 threshold [55].

Therefore, the association between plant tissue N:P ratios and soil nutrient limitation is complex, and it is necessary to synthesize various factors in practical applications to more accurately judge soil nutrient limitation and provide scientific basis for agricultural production and ecological research. While N:P ratios of plant tissues can detect nutrient limitation, their thresholds have clear limitations in determination. This aligns with the need to consider multiple factors when developing fertilization strategies in agriculture; only by accounting for these complexities can we effectively support cotton yield and quality improvement, translating ecological stoichiometry insights into practical production guidance.

4.3. Characterization of Cotton Internal Stability and Its Relation to Nutrient Availability, Growth Requirements and Elemental Limitation

Stoichiometric homeostasis is a core concept in ecological stoichiometry. From the perspective of stoichiometric homeostasis, field experimental studies have shown that the stoichiometric homeostasis index of organisms is negative [28,31]. As emphasized in previous research, the strength of organismal stoichiometric homeostasis is generally characterized by the absolute value of the homeostasis index (H) [56]. In the present study, we showed that the stoichiometric homeostasis indices of cotton straw and seeds had both positive and negative values; therefore, we also used the absolute value of H to characterize their strengths and weaknesses. The strength of stoichiometric internal stability reflects the physiological and biochemical adaptation of organisms to environmental changes [17,18], as well as the physiological allocation of organisms to the external environment [57]. Homeostasis is a key characteristic of organisms in responding to environmental changes [58]. Within the same plant, different tissues exhibit variations in stoichiometric balance, which reflects the fundamental balance of nutrient uptake and distribution [59]. Species’ resource use and storage capacity minimizes environmental fluctuations [60]. The C:N ratio of cotton organs is an important indicator of their growth and internal stability, which implies that optimizing fertilization strategies can improve the nutrient use efficiency of the soil and the crop, which in turn enhances cotton yield and quality. Our study showed that different cotton tissues differed in their response to soil elements such as nitrogen and phosphorus in the face of long-term fertilization. Such differences may be related to the different physiological functions, growth stages, and material accumulation processes of seeds and straw. Seeds, as reproductive organs, may need to maintain a relatively stable stoichiometry to ensure the normal development of their offspring, whereas straw is more involved in the transfer and metabolism of substances in the later stages of growth, and thus is more plastic to the changes in soil nutrients (Table 3, Figure 6). Significant differences exist in the variation trend of cotton’s stoichiometric homeostasis index during plant growth and development [61]. The present study showed that application of different nutrient allocation ratios significantly affected the nutrient supply and growth of cotton (Figure 1 and Figure 2), and nutrient supply had a key influence on its growth and internal stability characteristics, with vigorous growth and increased carbon fixation when nitrogen was sufficient, but N:P might rise due to the relative deficiency in phosphorus. The results of this study were summarized as follows. A proper nutrient partitioning ratio is essential for cotton growth and resource utilization. The stability of plant elemental composition is primarily regulated by core physiological processes (e.g., nutrient uptake, assimilation, and utilization), which serve as the foundation for maintaining plant stoichiometric homeostasis [1]. The internal stability index can not only reflect the stability characteristics of plants and their adaptive strategies to the environment, but the internal stability strength of dominant species is also an important parameter to reflect the stability and productivity of ecosystems [58]. It is worth noting that the magnitude or strength of the eco-chemometric internal stability index varies greatly among different plant species or plant functional groups, different growth stages, and different organs or tissues [56]. For cotton, there is a significant difference in the demand status of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and other elements at different growth stages [62]. From seedling to bud stage, cotton is mainly a nutritive growth stage, and chemical elements are mainly accumulated in nutrient organs such as roots, straws and leaves. When cotton enters the boll stage and up to the fluffing stage, chemical elements are transferred and accumulated in large quantities to reproductive organs (buds, bolls and cotton peaches) [63]. This change in elemental demand and distribution results in a large change in the internal stability index of cotton at different growth stages.

The in-depth analysis in this study showed that elements C, N, and P exhibited a certain degree of homeostasis qualities in cotton plants, and this homeostasis varied significantly among the organs of the cotton plant. The results of this study profoundly reflect that cotton organ C:N ratios can be adjusted in time according to the dynamic changes in nutrient supply in order to adapt to different growth requirements and realize the efficient use of soil resources. As observed, cotton organ C:N:P ratios’ response to soil resources is affected by physiological functions, growth stages, and material accumulation processes. This multi-factor dependency highlights why fertilization strategies must be developed with full consideration of these variables.

5. Conclusions

Long-term use of different fertilization strategies significantly altered soil C, N, P contents and their stoichiometric ratios. Balanced NPK fertilization increased SOC by 22.7% and STP by 48.6% compared to CK, while single N application elevated soil N:P to 3.2. The average soil C:N:P ratio was 150:2.5:1, showing distinct characteristics of arid soils. Dynamic changes in soil C, N, P stoichiometry directly affected cotton nutrient uptake and distribution. Soil available phosphorus (AP) was the key driver of cotton P uptake. NPK treatment increased seed P content by 68.2% but reduced straw C content by 10.2%, revealing carbon allocation trade-offs, with seeds showing preferential nutrient translocation. Long-term fertilization significantly changed stoichiometric homeostasis between cotton organs and soil, with distinct organ-specific responses. Straw exhibited strong C stability (1/H = −0.64) but plastic N:P ratios (1/H = 1.95), while seeds maintained stricter C homeostasis (1/H = −0.40) and stable N regulation (1/H = 0.12), aligning with reproductive priority. Plant tissue N:P ratios can reflect soil nutrient limitation but cannot be solely relied upon. The widely used 14/16 threshold showed limited applicability in this arid cotton system, and local suitable thresholds were identified as seed N:P 9.1/13.2 and straw N:P 1.5/5.9. Nutrient co-limitation and organ-specific stoichiometric variation reduced the universality of a single global threshold.

Overall, balanced NPK fertilization is optimal for arid gray desert soil cotton systems, enhancing carbon sequestration and phosphorus retention while mitigating stoichiometric imbalances. Future fertilization strategies should prioritize phosphorus management, account for organ-specific nutrient demands, and integrate soil nutrient availability with plant stoichiometric traits for precise nutrient limitation diagnosis, providing scientific basis for sustainable soil fertility management and high-efficiency cotton production in arid agroecosystems.

Author Contributions

Writing—Review and Editing, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Conceptualization, X.W.; Writing—review and editing, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, J.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Funding Acquisition, H.L.; Writing—Review & Editing, Investigation, Data Curation, Software, X.Q.; Writing—review and editing, Writing—original drafts, Supervision, Investigation, Funding acquisition, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the earmarked fund for the Research on Obstacle Reduction and Production Capacity Enhancement Technology for Medium and Low Yield Fields (No. 2022A02007), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. U1703232 and 41461066), the China Agriculture Research System’s National Cotton Industry Technology System (No. CARS-15), the National Soil Quality Xinshiqu Observation and Experimental Station (NAES095SQ36).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sterner, R.W.; Elser, J.J. Ecological Stoichiometry: The Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1-4008-8569-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Chen, G. Ecological stoichiometry: A science to explore the complexity of living systems. Acta Phytoecol. Sin. 2005, 29, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, G. Ecological stoichiometry characteristics of ecosystem carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus elements. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2008, 28, 3937–3947. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, A.F. The Ratios of Life. Science 2003, 300, 906–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessen, D.O.; Elser, J.J.; Sterner, R.W.; Urabe, J. Ecological Stoichiometry: An Elementary Approach Using Basic Principles. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2013, 58, 2219–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Chen, H.M.; Zhang, X.H.; Shi, F.X.; Song, C.C. Effects of P Addition on Plant C:N:P Stoichiometry in an N-Limited Temperate Wetland of Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minden, V.; Kleyer, M. Internal and External Regulation of Plant Organ Stoichiometry. Plant Biol. J. 2014, 16, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaswar, M.; Ahmed, W.; Jing, H.; Hongzhu, F.; Xiaojun, S.; Xianjun, J.; Kailou, L.; Yongmei, X.; Zhongqun, H.; Asghar, W.; et al. Soil Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorus (P) Stoichiometry Drives Phosphorus Lability in Paddy Soil under Long-Term Fertilization: A Fractionation and Path Analysis Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, R.; Chapin, F.S., III. The Mineral Nutrition of Wild Plants Revisited: A Re-Evaluation of Processes and Patterns. In Advances in Ecological Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 30, pp. 1–67. ISBN 978-0-12-013930-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Jiang, L.; Zeng, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, C. Reviews on the Ecological Stoichiometry Characteristics and Its Applications. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 5484–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, E.; Terrer, C.; Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Ahlström, A.; van Lissa, C.J.; Zhao, X.; Xia, N.; Wu, X.; Jackson, R.B. Global Patterns of Terrestrial Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, B.W.; Alvarez-Clare, S.; Castle, S.C.; Porder, S.; Reed, S.C.; Schreeg, L.; Townsend, A.R.; Cleveland, C.C. Assessing Nutrient Limitation in Complex Forested Ecosystems: Alternatives to Large-scale Fertilization Experiments. Ecology 2014, 95, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Xia, Y.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X.; Rui, Y.; Gunina, A.; He, X.; Ge, T.; Wu, J.; Su, Y.; et al. Stoichiometry of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus in Soil: Effects of Agricultural Land Use and Climate at a Continental Scale. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerselman, W.; Meuleman, A.F.M. The Vegetation N:P Ratio: A New Tool to Detect the Nature of Nutrient Limitation. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güsewell, S.; Bollens, U. Composition of Plant Species Mixtures Grown at Various N:P Ratios and Levels of Nutrient Supply. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2003, 4, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bai, Y.; Han, X. Differential Responses of N:P Stoichiometry of Leymus Chinensis and Carex Korshinskyi to N Additions in a Steppe Ecosystem in Nei Mongol. Acta Bot. Sin. 2004, 46, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessen, D.O.; Ågren, G.I.; Anderson, T.R.; Elser, J.J.; de Ruiter, P.C. Carbon Sequestration in Ecosystems: The Role of Stoichiometry. Ecology 2004, 85, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, J.J.; Fagan, W.F.; Kerkhoff, A.J.; Swenson, N.G.; Enquist, B.J. Biological Stoichiometry of Plant Production: Metabolism, Scaling and Ecological Response to Global Change. New Phytol. 2010, 186, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasingh, P.D.; Weider, L.J.; Sterner, R.W. Genetically-based Trade-offs in Response to Stoichiometric Food Quality Influence Competition in a Keystone Aquatic Herbivore. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güsewell, S. N:P Ratios in Terrestrial Plants: Variation and Functional Significance. New Phytol. 2004, 164, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limpens, J.; Berendse, F. Growth Reduction of Sphagnum Magellanicum Subjected to High Nitrogen Deposition: The Role of Amino Acid Nitrogen Concentration. Oecologia 2003, 135, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Elser, J.J.; He, N.; Wu, H.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, G.; Han, X. Stoichiometric Homeostasis of Vascular Plants in the Inner Mongolia Grassland. Oecologia 2011, 166, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, J.; Clark, C.M.; Naeem, S.; Pan, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Han, X. Tradeoffs and Thresholds in the Effects of Nitrogen Addition on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning: Evidence from Inner Mongolia Grasslands. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Duan, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Yao, C.; Chen, Y.; Cao, W.; Niu, Y. Patterns and Driving Factors of Soil Ecological Stoichiometry in Typical Ecologically Fragile Areas of China. CATENA 2022, 219, 106628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindraban, P.S.; Dimkpa, C.; Nagarajan, L.; Roy, A.; Rabbinge, R. Revisiting Fertilisers and Fertilisation Strategies for Improved Nutrient Uptake by Plants. Biol. Fertil Soils 2015, 51, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, B.L.; Walbridge, M.R.; Aldous, A. Patterns in Nutrient Availability and Plant Diversity of Temperate North American Wetlands. Ecology 1999, 80, 2151–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S. Soil and Agricultural Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000; ISBN 978-7-109-06644-1. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, J.; Fink, P.; Goto, A.; Hood, J.M.; Jonas, J.; Kato, S. To Be or Not to Be What You Eat: Regulation of Stoichiometric Homeostasis among Autotrophs and Heterotrophs. Oikos 2010, 119, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, J.; Cai, L.; Qi, P.; Zhang, R.; Luo, Z. Effects of no-tillage and straw mulching on carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus ecological stoichiometry in spring wheat and soil. Chin. J. Ecol. 2021, 40, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, W.; Cotner, J.B.; Sterner, R.W.; Elser, J.J. Are Bacteria More like Plants or Animals? Growth Rate and Resource Dependence of Bacterial C:N:P Stoichiometry. Funct. Ecol. 2003, 17, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Wu, H.; Shi, Q.; Hao, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G. Multielement Stoichiometry of Submerged Macrophytes across Yunnan Plateau Lakes (China). Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarrón, M.; Faz, A.; Acosta, J.A. Use of Multivariable and Redundancy Analysis to Assess the Behavior of Metals and Arsenic in Urban Soil and Road Dust Affected by Metallic Mining as a Base for Risk Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Sardans, J.; Zhang, J.; Peuelas, J. Variations in Foliar Carbon∶nitrogen and Nitrogen∶phosphorus Ratios under Global Change: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Field Studies. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.Y.; Chen, H.Y.H. Decoupling of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in Terrestrial Plants Associated with Global Changes. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Porder, S.; Houlton, B.Z.; Chadwick, O.A. Terrestrial Phosphorus Limitation: Mechanisms, Implications, and Nitrogen–Phosphorus Interactions. Ecol. Appl. 2010, 20, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batjes, N.H. Total Carbon and Nitrogen in the Soils of the World. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 65, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Alcaraz, M.N.; Egea, C.; Jiménez-Cárceles, F.J.; Párraga, I.; María-Cervantes, A.; Delgado, M.J.; Álvarez-Rogel, J. Storage of Organic Carbon, Nitrogen and Phosphorus in the Soil-Plant System of Phragmites Australis Stands from a Eutrophicated Mediterranean Salt Marsh. Geoderma 2012, 185–186, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhu, M.; An, S. Stoichiometry characteristics of leaves and soil of four shrubs in the upper reaches of the Tarim River Desert. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 8326–8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassen, M.J.; Olde Venterink, H.G.M.; De Swart, E.O.A.M. Nutrient Concentrations in Mire Vegetation as a Measure of Nutrient Limitation in Mire Ecosystems. J. Veg. Sci. 1995, 6, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibar, D.T.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, X. Ecological Stoichiometric Characteristics of Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorus (P) in Leaf, Root, Stem, and Soil in Four Wetland Plants Communities in Shengjin Lake, China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davide, F.; Elke, S.; Guillaume, L.; Tesfaye, W.; Francois, B.; Thomas, R. Mineral vs. Organic Amendments: Microbial Community Structure, Activity and Abundance of Agriculturally Relevant Microbes Are Driven by Long-Term Fertilization Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yu, M.; Cheng, X. Leaf Non-Structural Carbohydrate Allocation and C:N:P Stoichiometry in Response to Light Acclimation in Seedlings of Two Subtropical Shade-Tolerant Tree Species. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 124, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Khanal, B.R. Soil Organic Matter Dynamics in Semiarid Agroecosystems Transitioning to Dryland. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Niu, L.; Hu, K.; Hao, J.; Li, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Long-term Effects of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization on Soil Aggregate Stability and Aggregate-associated Carbon and Nitrogen in the North China Plain. Soil Sci. Soc. Amer. J. 2021, 85, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.W.; Luo, Q.; Qin, Z.H.; Liu, W.S.; Li, H.R.; Lal, R.; Dang, Y.P.; Smith, P.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.L. Aridity Drives the Response of Soil Organic Carbon and Inorganic Carbon to Drought in Cropland. Glob Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naasko, K.I.; Naylor, D.; Graham, E.B.; Couvillion, S.P.; Danczak, R.; Tolic, N.; Nicora, C.; Fransen, S.; Tao, H.; Hofmockel, K.S.; et al. Influence of Soil Depth, Irrigation, and Plant Genotype on the Soil Microbiome, Metaphenome, and Carbon Chemistry. mBio 2023, 14, e01758-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, D.; Yang, T.; Liu, W.; Huang, Y.; Jin, H. Fertility changes and comprehensive quality evaluation of dryland red soil under different long-term fertilization patterns. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 36, 3007–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Sun, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, T.; Shakouri, M.; Zheng, L.; Sui, P.; et al. Iron-Tuned Depth-Dependent P Transformation on Calcium Carbonate Coprecipitates: The Impact of Fe and P Loadings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15151–15158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göran, I. Ågren Stoichiometry and Nutrition of Plant Growth in Natural Communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craine, J.M.; Morrow, C.; Stock, W.D. Nutrient Concentration Ratios and Co-limitation in South African Grasslands. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenovsky, R.E.; Richards, J.H. Critical N:P Values: Predicting Nutrient Deficiencies in Desert Shrublands. Plant Soil 2004, 259, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Yan, Z.; Fang, J. Review on characteristics and main hypotheses of plant ecological stoichiometry. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2021, 45, 682–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei-Ping, Z.; Dario, F.; Guang-Cai, L.; Josep, P.; Jordi, S.; Jian-Hao, S.; Li-Zhen, Z.; Long, L. Interspecific Interactions Affect N and P Uptake Rather than N:P Ratios of Plant Species: Evidence from Intercropping. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Tang, L.; Chen, Y.; Fang, J. Relationship between the Relative Limitation and Resorption Efficiency of Nitrogen vs Phosphorus in Woody Plants. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Tian, D.; Han, W.; Tang, Z.; Fang, J. An Assessment on the Uncertainty of the Nitrogen to Phosphorus Ratio as a Threshold for Nutrient Limitation in Plants. Ann. Bot. 2017, 120, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Hu, T.; Tang, D.; Chen, Q. Characteristics of plant ecological stoichiometry homeostasis. Guihaia 2019, 39, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.C.; Seehausen, O.; Matthews, B. The Ecology and Evolution of Stoichiometric Phenotypes. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Elser, J.J.; He, N.; Wu, H.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J.; Bai, Y.; Han, X. Linking Stoichiometric Homoeostasis with Ecosystem Structure, Functioning and Stability. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Larmola, T.; Murphy, M.T.; Moore, T.R.; Bubier, J.L. Stoichiometric Response of Shrubs and Mosses to Long-Term Nutrient (N, P and K) Addition in an Ombrotrophic Peatland. Plant Soil 2016, 400, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Arif, M.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Geng, Q.; Yin, F.; Li, C. Plant-Soil Interactions and C:N:P Stoichiometric Homeostasis of Plant Organs in Riparian Plantation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 979023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y. Charateristics Ecological Stoichiometry of Oasis Farmland Ecosystem in the Northern Marigin of Tarim Basin. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang University, Ürümqi, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Sheng, J. Effects of combined applications of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium fertilizers on cotton nutrient absorption, yield and fertilizer utilization efficiency. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 55, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, L.; Yang, G.; Song, X.; Wang, D.; Chen, Q.; Bataung, M. Study progress on dry matter and nutrient accumulation distribution of China cotton. Jiangxi Cotton 2011, 33, 7–9+19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).