Sustained Inoculation of a Synthetic Microbial Community Engineers the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Enhanced Pepper Productivity and Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strains and SynCom Preparation

2.2. Pot Experiment Design and Plant Cultivation

2.3. Plant Growth, Yield, and Fruit Quality Measurements

2.4. Rhizosphere Soil Sampling, DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

2.5. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

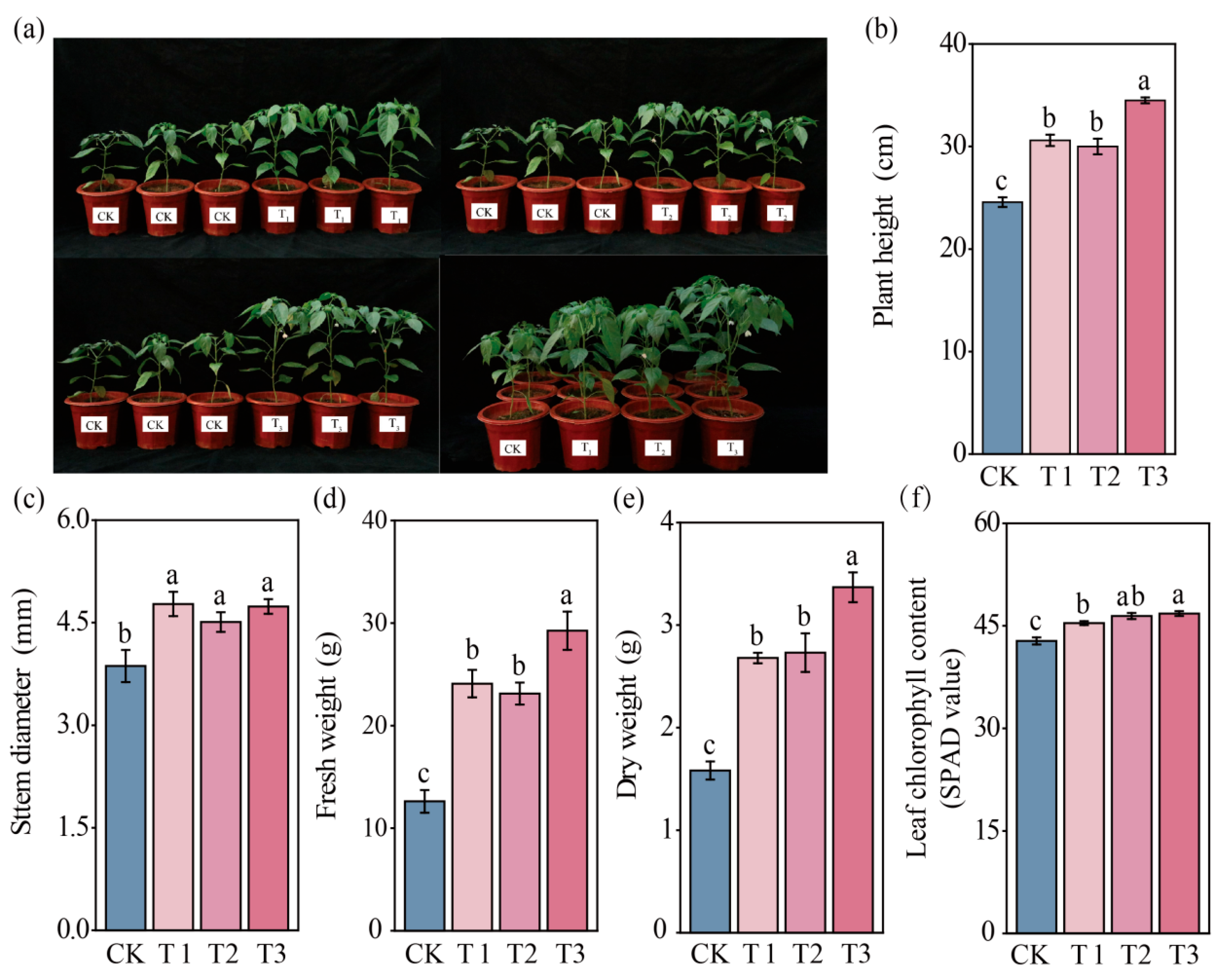

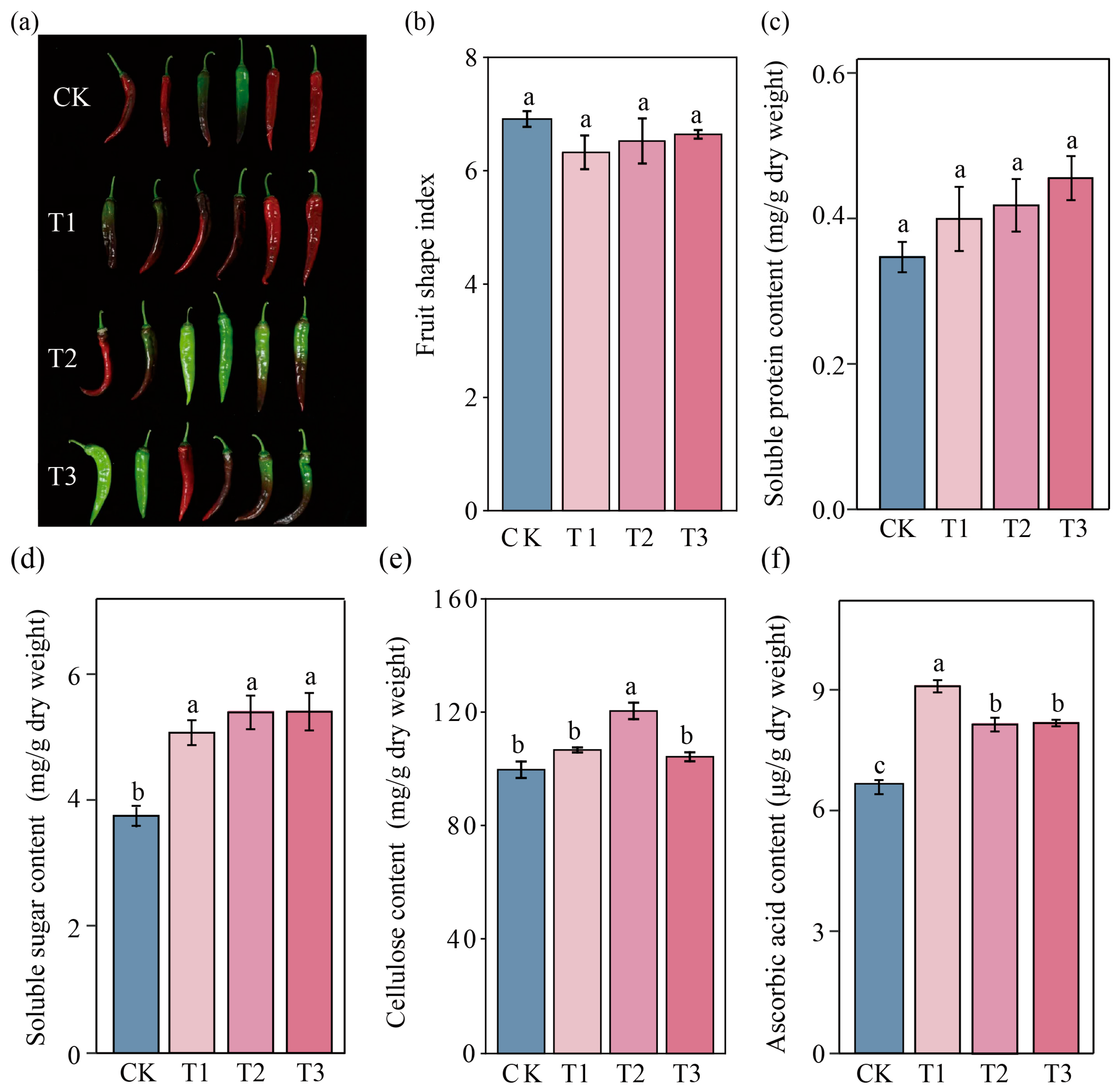

3.1. Effects of SynCom Inoculation on Pepper Growth, Yield, and Quality

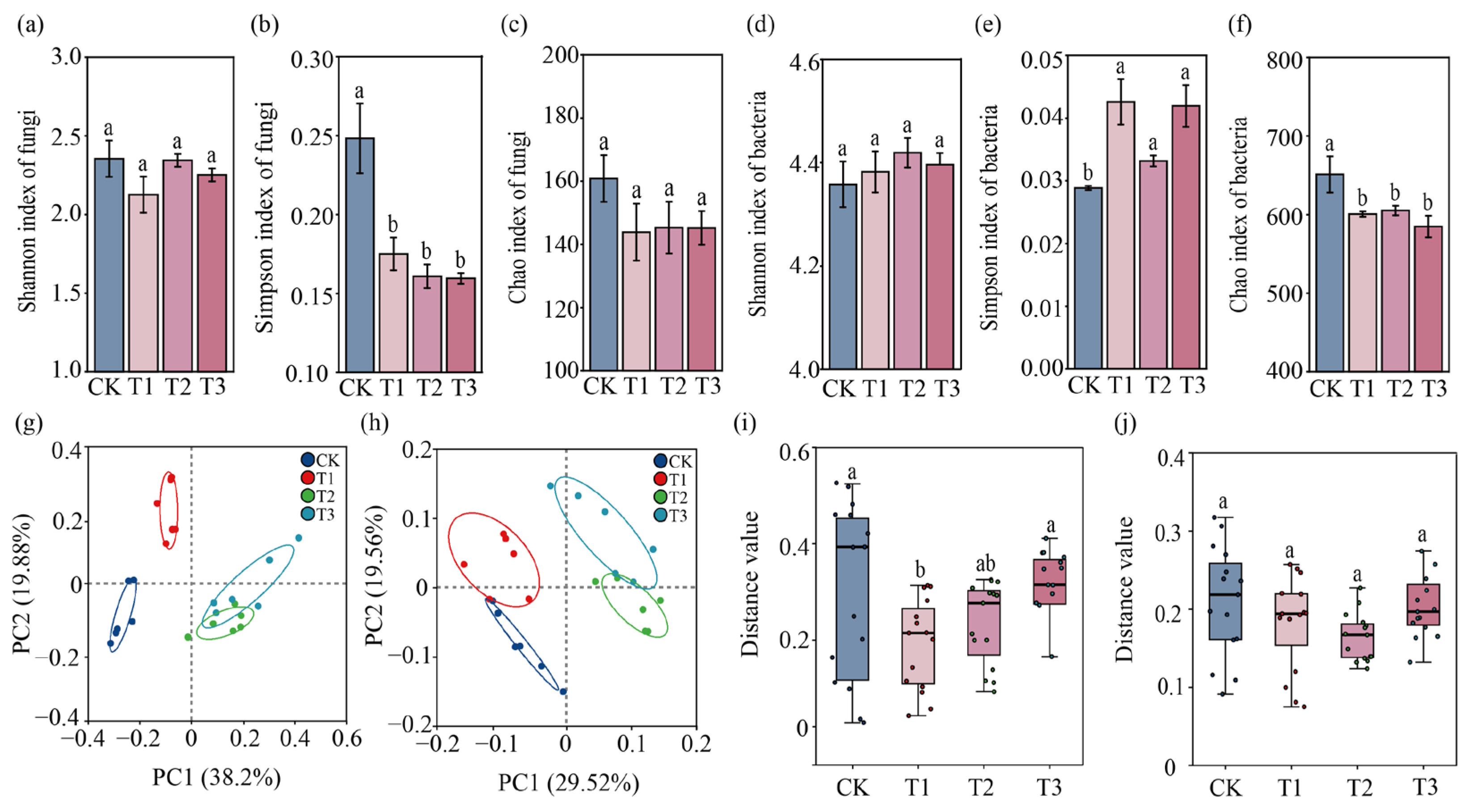

3.2. Effects of SynCom Inoculation on Rhizosphere Microbial Community Structure

3.3. Effects of Sustained Inoculation on Beneficial Microbial Functional Potentials

3.4. Effects of SynCom Inoculation on Rhizosphere Microbial Co-Occurrence Network

3.5. Correlation of Total Yield with Key Microbial Communities and Microbial Functions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SynCom | Synthetic microbial community |

| PGPMs | Plant growth-promoting microorganisms |

| OTU | Operational Taxonomic Unit |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| PDB | Potato Dextrose Broth |

| LB | Luria Broth |

| MS | Murashige Skoog |

| PGPR | Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria |

| TTC | Triphenyl Tetrazolium Chloride |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KO | KEGG Orthologs |

| PICRUSt2 | Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States 2 |

| FUNGuild | Fungi Functional Guild |

| SPAD | Soil and Plant Analyzer Development |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinate Analysis |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| DESeq2 | Differential Expression analysis for Sequence data 2 |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| QIIME2 | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

References

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024: Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade, N.; Peleg, Z. Future challenges for global food security under climate change. Plant Sci. 2020, 295, 110467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Trivedi, P.; Egidi, E.; Macdonald, C.A.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Crop microbiome and sustainable agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 601–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.R.; Chen, H.; Cui, H. Nanotechnology applications and implications of agrochemicals toward sustainable agriculture and food systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6451–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Cassan, F.; Kostić, T.; Johnson, L.; Brader, G.; Trognitz, F.; Sessitsch, A. Harnessing the plant microbiome for sustainable crop production. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 23, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Gu, Y.; Friman, V.-P.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Q.; Jousset, A. Initial soil microbiome composition and functioning predetermine future plant health. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eaaw0759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Pandey, E.; Bushra, S.; Faizan, S.; Pandey, S. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) induced protection: A plant immunity perspective. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade, L.A.; Santos, C.H.B.; Frezarin, E.T.; Sales, L.R.; Rigobelo, E.C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable agricultural production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Mechanisms and applications. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 963401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, P.; Puopolo, G.; Santoyo, G. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms: New insights and the way forward. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 297, 128168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mei, S.; Salles, J.F. Inoculated microbial consortia perform better than single strains in living soil: A meta-analysis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 190, 105011–105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Microbial inoculants: Reviewing the past, discussing the present and previewing an outstanding future for the use of beneficial bacteria in agriculture. AMB Express 2019, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X. Towards sustainable agriculture: Rhizosphere microbiome engineering. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 7141–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiranmayee, G.; Marik, D.; Sadhukhan, A.; Reddy, G.S. Isolation of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria from the agricultural fields of Tattiannaram, Telangana. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.-L.; Zhang, Q.-G.; Buckling, A.; Castledine, M. Interspecific niche competition increases morphological diversity in multi-species microbial communities. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 699190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.S.C.; Armanhi, J.S.L.; Arruda, P. From microbiome to traits: Designing synthetic microbial communities for improved crop resiliency. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorholt, J.A.; Vogel, C.; Carlström, C.I.; Müller, D.B. Establishing causality: Opportunities of synthetic communities for plant microbiome research. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.J.; Pasche, J.; Silva, H.A.O.; Selten, G.; Savastano, N.; Abreu Lucas, M.; Bais, H.P.; Garrett, K.A.; Kraisitudomsook, N.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; et al. The use of synthetic microbial communities to improve plant health. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roy, K.; Marzorati, M.; Van den Abbeele, P.; Van de Wiele, T.; Boon, N. Synthetic microbial ecosystems: An exciting tool to understand and apply microbial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 1472–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, M.; Tang, S.; Ou, L.; Li, D. Synthetic microbial communities enhance pepper growth and root morphology by regulating rhizosphere microbial communities. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, F.; Novello, G.; Bona, E.; Gorrasi, S.; Gamalero, E. Impact of plant-beneficial bacterial inocula on the resident bacteriome: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2462–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, P.; Martignoni, M.M.; McManus, L.C.; Sakal, T.; Liaghat, A.; Stevens, B.; Dahlin, K.J.M.; Souza, L.S.; Cardon, Z.G.; Silveira, C.B.; et al. Theory of host-microbe symbioses: Challenges and opportunities. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Jiao, S.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, G. A simplified synthetic community rescues Astragalus mongholicus from root rot disease by activating plant-induced systemic resistance. Microbiome 2021, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, H.; Guo, H.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q.; et al. Synthetic community derived from grafted watermelon rhizosphere provides protection for ungrafted watermelon against Fusarium oxysporum via microbial synergistic effects. Microbiome 2024, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Singh, K.; Chandra, R. Recent advances of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) for eco-restoration of polluted soil. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 100845–100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amacker, N.; Gao, Z.; Jousset, A.L.C.; Geisen, S.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Identity and timing of protist inoculation affect plant performance largely irrespective of changes in the rhizosphere microbial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0024025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, G.-R.; Lee, K.K.; Clark, I.M.; Mauchline, T.H.; Kavamura, V.N.; Jee, S.; Lee, J.-T.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.-H. Changes in the potato rhizosphere microbiota richness and diversity occur in a growth stage-dependent manner. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2284–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Singh, B.K.; He, J.-Z.; Han, Y.-L.; Li, P.-P.; Wan, L.-H.; Meng, G.-Z.; Liu, S.-Y.; Wang, J.-T.; Wu, C.-F.; et al. Plant developmental stage drives the differentiation in ecological role of the maize microbiome. Microbiome 2021, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, J.; Xing, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z. Adaptation of rhizosphere bacterial communities of drought resistant sugarcane varieties under different degrees of drought stress. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0118423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan, A.; Sultana, S.; Huei, C.S.; Razman, M.R. Antioxidant, anti-obesity, nutritional and other beneficial effects of different chili pepper: A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, S.; Yadav, R.; Ramakrishna, W. Bacillus subtilis impact on plant growth, soil health and environment: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 3543–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Etesami, H.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma: A multifunctional agent in plant health and microbiome interactions. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, R.; Lee Rutgers, S. Applications of Aspergillus in Plant Growth Promotion. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Gupta, V.K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, M.T.; Van Nguyen, M.; Han, J.W.; Kim, B.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, M.S.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.J. Biocontrol Potential of Aspergillus Species Producing Antimicrobial Metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 804333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, T.; Liao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J. Soil plastisphere interferes with soil bacterial community and their functions in the rhizosphere of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 270, 115946–115958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, B.P. Spad value varies with age and leaf of maize plant and its relationship with grain yield. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobet, G.; Pagès, L.; Draye, X. A novel image-analysis toolbox enabling quantitative analysis of root system architecture. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xia, S.; Su, Y.; Wang, H.; Luo, W.; Su, S.; Xiao, L. Brassinolide increases potato root growth in vitro in a dose-dependent way and alleviates salinity stress. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 8231873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Author correction: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. ICWSM 2009, 3, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Wang, B.; Yoshikuni, Y. Microbiome engineering: Synthetic biology of plant-associated microbiomes in sustainable agriculture. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.E.; Harcombe, W.R.; Hatzenpichler, R.; Lindemann, S.R.; Löffler, F.E.; O’Malley, M.A.; García Martín, H.; Pfleger, B.F.; Raskin, L.; Venturelli, O.S.; et al. Common principles and best practices for engineering microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. Plant growth-promoting bacteria of soil: Designing of consortia beneficial for crop production. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2864–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhalnina, K.; Louie, K.B.; Hao, Z.; Mansoori, N.; da Rocha, U.N.; Shi, S.; Cho, H.; Karaoz, U.; Loqué, D.; Bowen, B.P.; et al. Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semchenko, M.; Barry, K.E.; de Vries, F.T.; Mommer, L.; Moora, M.; Maciá-Vicente, J.G. Deciphering the role of specialist and generalist plant–microbial interactions as drivers of plant–soil feedback. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1929–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavira, J.A.; Rico-Jiménez, M.; Ortega, Á.; Petukhova, N.V.; Bug, D.S.; Castellví, A.; Porozov, Y.B.; Zhulin, I.B.; Krell, T.; Matilla, M.A. Emergence of an auxin sensing domain in plant-associated bacteria. mBio 2023, 14, e0336322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacheron, J.; Desbrosses, G.; Bouffaud, M.-L.; Touraine, B.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Muller, D.; Legendre, L.; Wisniewski-Dyé, F.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utami, Y.D.; Nguyen, T.A.N.; Hiruma, K. Investigating plant–microbe interactions within the root. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, B.; Domene, X.; Yao, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Kou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Microbial diversity in Chinese temperate steppe: Unveiling the most influential environmental drivers. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017, 93, fix031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Sun, J.; Xie, P.; Guo, C.; Zhu, K.; Tian, K. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity by increasing bacterial diversity and fungal interaction strength in litter decomposition. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168444–168458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzke, F.; Thiergart, T.; Hacquard, S. Contribution of bacterial-fungal balance to plant and animal health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 49, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Schlaeppi, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-W.; Braswell, W.E.; Kunta, M. Co-occurrence analysis of citrus root bacterial microbiota under citrus greening disease. Plants 2023, 13, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Morinaga, K.; Tamaki, H. Complete genome sequence of Dyella sp. Strain GSA-30, a predominant endophytic bacterium of Dendrobium Plants. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2023, 12, e0133822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; Lawrence, D.P.; Nouri, M.T.; Doll, D.A.; Trouillas, F.P. Characterization of Fusarium and Neocosmospora species associated with crown rot and stem canker of pistachio rootstocks in California. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Rodríguez, A.M.; Parra Cota, F.I.; Cira Chávez, L.A.; García Ortega, L.F.; Estrada Alvarado, M.I.; Santoyo, G.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S. Microbial inoculants in sustainable agriculture: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. Plants 2025, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Pulido, V.; Huang, W.; Suarez-Ulloa, V.; Cickovski, T.; Mathee, K.; Narasimhan, G. Metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics approaches for microbiome analysis. Evol. Bioinform. 2016, 12, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; You, Y.; Xue, B.; Chen, J.; Du, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Suo, H.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, J. Decoding microbiota and metabolite transformation in inoculated fermented suansun using metagenomics, GC–MS, non-targeted metabolomics, and metatranscriptomics: Impacts of different Lactobacillus plantarum strains. Food Res. Int. 2025, 203, 115847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment | Single Fruit Weight (g) | Number of Fruits Per Plant | Yield Per Plant (g) | Yield (kg/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 23.3 ± 1.7 a | 17.5 ± 0.5 b | 407.2 ± 28.1 b | 15,268.2 ± 1052.3 b |

| T1 | 24.8 ± 0.6 a | 20.0 ± 1.0 a | 499.2 ± 37.7 ab | 18,720.0 ± 1412.6 ab |

| T2 | 25.8 ± 0.5 a | 20.0 ± 1.0 a | 518.2 ± 35.0 a | 19,430.7 ± 1312.2 a |

| T3 | 26.2 ± 0.4 a | 20.0 ± 1.0 a | 525.1 ± 34.1 a | 19,691.3 ± 1278.0 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Z.; Li, D. Sustained Inoculation of a Synthetic Microbial Community Engineers the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Enhanced Pepper Productivity and Quality. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2888. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122888

Xu J, Liu Q, Huang Z, Li D. Sustained Inoculation of a Synthetic Microbial Community Engineers the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Enhanced Pepper Productivity and Quality. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2888. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122888

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jiayuan, Qiumei Liu, Zhigang Huang, and Dejun Li. 2025. "Sustained Inoculation of a Synthetic Microbial Community Engineers the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Enhanced Pepper Productivity and Quality" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2888. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122888

APA StyleXu, J., Liu, Q., Huang, Z., & Li, D. (2025). Sustained Inoculation of a Synthetic Microbial Community Engineers the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Enhanced Pepper Productivity and Quality. Agronomy, 15(12), 2888. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122888