Abstract

High-volume fly ash (FA) mitigates the expansion of magnesium oxide (MgO), and the uneven regional distributions of high-quality FA collectively limit the application of roller-compacted concrete admixed with MgO (M-RCC). This study evaluated the autoclave expansion and compressive strength of MgO-admixed cement paste and mortar, wherein phosphorus slag (PS) was used to partially or fully replace FA. The expansion mechanism within the MgO-FA-PS system was explored. Results show that the autoclave expansion of the mortar increased as the proportion of PS replacing FA rose. At a replacement ratio of 33% (i.e., 20% of the total mass of cementitious materials), the mortar maintained the same ultimate MgO dosage (8%) as the control specimen, yet exhibited a 12.7% increase in expansion and an 8.8% decrease in strength. The mechanism is that PS is less efficient than FA in reducing the pore solution alkalinity, thereby promoting the formation of more brucite. The growth pressure of brucite crystals expands the internal gaps in the matrix and coarsens the pore size, resulting in greater expansion and reduced compressive strength. The results of this study can provide theoretical and technical insights for the application of PS in M-RCC.

1. Introduction

Roller-compacted concrete (RCC) has the advantages of rapid construction and reduced cement usage [1], but it is challenged by the issue of thermal cracking in mass concrete [2]. MgO-admixed RCC (M-RCC), prepared by externally incorporating an appropriate amount of light-burned magnesium oxide (MgO), can utilize the delayed expansion of MgO to compensate for the volume shrinkage of concrete during temperature drop, effectively reducing the risk of cracking [2,3]. The combination of RCC dam construction technology and MgO concrete dam construction technology greatly simplifies temperature control measures and shortens the construction period, meeting the requirements for green and low-carbon dam construction. However, over more than 40 years of MgO concrete dam construction practice in China, it has been found that the expansion of concrete generally fails to meet the required expansion range of (200–300) × 10−6/a, which is necessary to completely compensate for the temperature drop shrinkage [3]. The expansion of normal MgO concrete is between (120–180) × 10−6/a, while that of M-RCC is as low as around (50–100) × 10−6/a [3,4,5]. Obviously, the low expansion of M-RCC fails to reach the full superiority of MgO concrete dam construction technology. Therefore, how to appropriately increase the expansion of M-RCC has become a new research topic in concrete dam construction.

There are many factors that affect the expansion of M-RCC, mainly including MgO dosage, MgO reactivity, curing temperature, and fly ash (FA) content [6]. While increasing MgO content enhances the expansion of concrete, it may reduce mechanical properties [7]. MgO reactivity affects both the expansion rate and the final expansion amount of concrete [8], and temperature is crucial for expansion modeling [2]. It is worth noting that FA suppresses the expansion of MgO hydration [9,10], and the higher the FA content, the stronger the suppressive effect [10,11]. In RCC, FA content can reach up to 70% [12]. Therefore, optimizing FA admixture becomes crucial for enhancing the expansion performance of M-RCC. As China’s hydropower projects move to FA-scarce western areas and the country aims for carbon neutrality by 2060, exploring FA substitute materials for M-RCC becomes increasingly important.

In recent years, beyond FA, the application of various supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) in RCC has been extensively explored, including pozzolan [13], steel slag [14], silica fume [15], and ground granulated blast furnace slag [16]. These SCMs play a role in enhancing the mechanical properties and durability of RCC. However, their large-scale application is subject to some limitations, such as higher costs or regional availability constraints [17]. In contrast, SCMs like Phosphorus Slag (PS), a solid waste discharged during the process of yellow-phosphor manufacture, are produced annually in excess of 3.6 million tons in the United States and over 8 million tons in China [18]. Its chemical components are mainly SiO2 and CaO, and the glass phase content is more than 90%, indicating its potential pozzolanic reactivity [18,19]. Furthermore, studies have shown that PS significantly improves the microstructure of the transitional interface in concrete, enhances the mechanical properties of concrete at later ages, and reduces shrinkage [20,21,22]. Moreover, practical engineering cases [23,24] have demonstrated that the retarding characteristics and reduced hydration heat associated with PS enhance the interlayer bonding between new and old concrete, while also preventing early cracking of mass concrete. This makes PS highly promising for application in RCC. Despite the positive research outcomes of PS in non-MgO expansion systems, its application and action mechanisms within MgO expansion systems remain underexplored. While Jin et al. [25] studied the synergistic effects of MgO and PS on the drying shrinkage of concrete, they did not address the influence of PS on the hydration expansion performance of MgO and its mechanism.

Current research on the hydration expansion mechanism of MgO has mainly focused on cement systems or cement–fly ash binary systems [26,27,28,29]. It should be noted that the expansion performance of MgO is affected by the alkalinity of the cement paste pore solution [30], and SCMs have been demonstrated to alter the alkaline environment of the system [30,31,32]. Hence, replacing FA with PS containing specific components like phosphates is highly likely to affect the hydration expansion performance of MgO. Therefore, the influence of PS on the expansion performance of MgO hydration, particularly its mechanism within the MgO-FA-PS system, requires further investigation. In view of this, the present study investigates the effects of replacing FA with PS on the autoclave expansion of MgO-admixed cement paste and mortar, through autoclave testing, compressive strength testing, and microstructural characterization. For the first time, the expansion mechanism of MgO-FA-PS systems is explored.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Three types of MgO were supplied by Haicheng Dongfang Smooth Magnesium Co., Ltd., Anshan, China. The reactivity values of these MgO, measured using the citric acid method [8], were recorded as 100 s, 240 s, and 400 s, and were designated as M100, M240, and M400, respectively. The larger the reactivity value, the lower the MgO reactivity [8]. It is recommended that MgO expansive agent with a reactivity value of 240 ± 40 s is utilized in dam concrete [33]. In this study, P·O 42.5 Portland cement (PC), Class II FA, and PS were used as binders. Both FA and PS were produced in Guizhou, China. The chemical compositions and physical properties of these raw materials are given in Table 1, while their particle size distributions are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions and physical properties of raw materials.

Table 2.

Particle size distributions and statistical parameters of raw materials.

In Table 1, the oxide mass composition of the raw materials was measured by X-ray fluorescence (XRF, Zetium, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) analysis. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area was assessed by N2 adsorption using a fully automated specific surface area and porosity analyzer. The water requirement ratio (WRR) and strength activity index (SAI) were tested according to the Chinese National Standard GB/T 1596-2017 [34]. WRR was calculated using the formula WRR = (M/MC) × 100%, where M and MC represent the water consumption of the test mortar (30% FA or 30% PS) and the control mortar (pure cement) to achieve a slump of 145–155 mm, respectively. SAI was determined using the formula SAI = (R/R0) × 100%, where R and R0 represent the compressive strengths of the test mortar (30% FA or 30% PS) and the control mortar (pure cement) at 28 d, respectively. The pozzolanic reactivity of FA and PS is generally reflected by the strength activity index [19]. The fine aggregate used for preparing mortars was manufactured sand with a fineness modulus of 2.96.

2.2. Specimen Preparation

Based on different research goals, two types of autoclave specimens were designed, namely mortar and paste. The preparation of these autoclave specimens was carried out in accordance with the Chinese State Standard on Autoclave Method for Soundness of Portland Cement (GB/T 750-1992) [35].

Different PS/(PS + FA) ratios were designed to investigate the influence of MgO dosage on the autoclave expansion and compressive strength of cement mortars. It is worth mentioning that to become closer to the composition of concrete, cement mortar, rather than cement paste, is often employed for the autoclave test to determine the ultimate MgO dosage in concrete in Chinese engineering, referred to as the mortar autoclave method [12]. During the preparation of mortar specimens, a water/binder ratio (W/B) of 0.5 and a binder/sand ratio (B/S) of 1:3.74 were maintained, consistent with those of M-RCC from a real dam project. A total mass of 800 g of sand and binder was weighed according to the binder/sand ratio. MgO (M240) was added to cement mortars at a certain percentage of the total binder mass. The proportions of PC and total SCMs (i.e., PS + FA) were fixed at 40% and 60%, by mass of the total binders, respectively. The replacement levels of FA with PS were controlled by adjusting the PS/(PS + FA) ratio (i.e., 0, 1/3, 2/3, and 1). That is, the replacement of FA by PS was 0% (serving as the control), 33%, 67%, and 100%. Detailed proportions of binders in the mortars are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Proportions of binders in mortar specimens (wt.%).

Taking cement pastes prepared with the recommended PS/(PS + FA) ratio as an example, the effects of MgO reactivity on the autoclave expansion and compressive strength were investigated. The paste specimens were prepared with a total binder mass of 800 g and a water requirement of standard consistency.

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Autoclave Expansion

The autoclave test was performed in accordance with the procedures outlined in Ref. [12]. Each cement paste and mortar was cast into two 25 × 25 × 280 mm steel molds with two brass heads half-buried into both ends of the bar. The distance between the two brass heads was recorded as the length of the prism specimen. Following a standard curing (20 ± 2 °C and relative humidity > 95%) for 24 h, these prism specimens were demolded. The initial length of the specimens was measured using a length comparator. Subsequently, the specimens underwent boiling for 3 h, were allowed to cool to room temperature, and were then placed in an autoclave. The specimens were subjected to autoclaving for 3 h in a saturated steam environment at 2 MPa and 216 °C. Upon cooling and removal from the autoclave, the lengths of the autoclaved specimens were measured. The autoclave expansion rate was calculated using the following Equation (1) [35].

where LA was the autoclave expansion rate; L0 was the initial length of the specimen after demoulding; L1 was the length of the specimen after autoclaving; L was the effective length of the specimen, i.e., initial length L0 minus the length of brass heads at both ends of the specimen.

When the autoclave expansion rate of a test specimen does not exceed 0.5%, the specimen is judged to be acceptable for volume stability qualification, as GB/T 750-1992 states.

2.3.2. Compressive Strength

Compressive strength test was conducted according to the Test Method for Cement Mortar Strength (ISO method) (GB/T 17671-2021) [36]. First, an autoclaved prism specimen (25 × 25 × 280 mm) underwent a flexural test to produce two half specimens, and then the two half specimens were subjected to compressive loading until failure at a rate of 2.4 kN/s, obtaining two strength values. Each group contained two prism specimens, resulting in a total of four strength values. The mean of these values was calculated to determine the reported compressive strength.

2.3.3. Microstructural Analysis

To make the research results more valuable for engineering practice, autoclaved pastes with 6% MgO were selected for microstructural analysis. After completing the compressive strength test, the paste specimens were broken into small pieces and soaked in anhydrous ethanol to terminate hydration. Some pieces were used for pore structure analysis, measured by the MIP method in a porosimeter (Auto Pore 9500 IV, Micromeritics). Other pieces were dried and ground into powder for XRD and thermal analysis testing. XRD analysis was performed using a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer at a 2θ range of 5–70° to characterize the phase composition of the hydration products. Thermal analysis was carried out using a thermogravimetric analyzer (STA449F3, NETZSCH, Selb, Germany) from room temperature to 1000 °C under an N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and the DTG-TGA curves were obtained.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Autoclave Expansion and Compressive Strength of MgO-Admixed Cement Mortars Based on Different PS/(PS + FA) Ratios

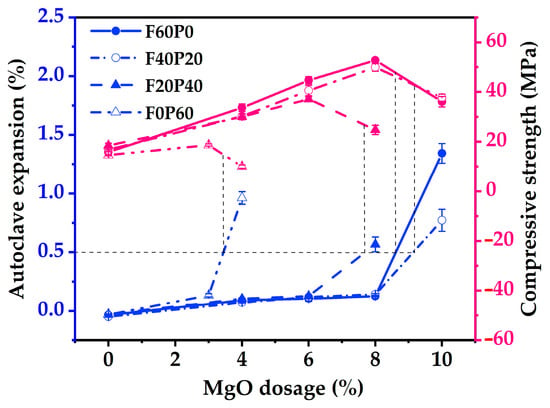

Figure 1 depicts the change curves of autoclave expansion and compressive strength with the MgO dosage (hereinafter referred to as expansion curve and strength curve, respectively) for the cement mortars prepared with varying PS/(PS + FA) ratios. It can be seen from Figure 1 that the autoclave expansion increases with the increasing MgO dosage. Notably, when the MgO dosage exceeds a certain quantity, the autoclave expansion is observed to increase significantly, as manifested by an obvious inflection point on the expansion curve. Conversely, excessive expansion may destroy the interface between the cement matrix and aggregate, leading to a reduction in strength [6,25]. Therefore, the strength curve increased first and then decreased with increasing MgO dosage. Similarly, a clear inflection point is observed on the strength curve. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that appropriate expansion can fill pores, thereby densifying the matrix and improving its compressive strength. As shown in Figure 1, when the ultimate MgO dosage in mortar was determined by the autoclave expansion of 0.5% (GB/T 750-1992), a noticeable reduction in compressive strength was observed, which is unfavorable for concrete structures. Consequently, many researchers agree that evaluating the volume stability of cement-based materials mixed with MgO should consider not only the expansion value but also the mechanical properties [6,12]. In the mortar autoclave method [37], the MgO dosage corresponding to the inflection point of the expansion curve is determined as the ultimate MgO dosage, provided that the compressive strength of the autoclaved specimen does not decrease. Based on this regulation, the ultimate MgO dosages for specimens F60P0, F40P20, F20P40, and F0P60 were determined to be 8%, 8%, 6%, and 3%, respectively, and the corresponding compressive strength values were 54.7 MPa, 49.9 MPa, 37.1 MPa, and 18.7 MPa. Although the ultimate MgO dosages for F60P0 and F40P20 were the same, their expansion values differed. Specifically, the expansion value of F40P20 was 0.142%, representing a 12.7% increase compared to F60P0’s expansion value of 0.126%, accompanied by an 8.8% reduction in compressive strength. Therefore, it can be concluded from Figure 1 that the autoclave expansion of the mortars increased with the increasing PS/(PS + FA) ratio and tended to exceed that of the control specimen.

Figure 1.

Effects of MgO dosage on the autoclave expansion and compressive strength of mortars.

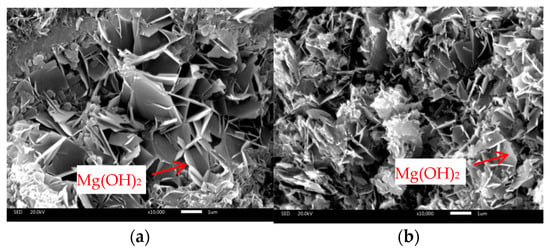

To more directly illustrate the effect of PS on the expansion of MgO hydration, the microstructures of specimens containing only FA (F60P0) and only PS (F0P60) as SCMs at the ultimate MgO dosages were examined, as depicted in Figure 2. In both specimens, hexagonal lamellar brucite crystals, approximately 1 micrometer in length, were observed, interacting with other hydration products. At the same time, the SEM (JSM-IT300, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) images revealed that the F0P60 specimen exhibited a more porous microstructure, despite the lower MgO dosage. This suggests that PS significantly affected the expansion of MgO hydration. In summary, under the test conditions utilized, the replacement ratio of PS for FA in the MgO-FA-PS system should be limited, with a recommended maximum of 33%. The corresponding proportions of binder material were 40% PC, 40% FA, and 20% PS.

Figure 2.

SEM images of the mortars: (a) F60P0, MgO = 8%; (b) F0P60, MgO = 3%.

3.2. Autoclave Expansion and Compressive Strength of Cement Pastes Based on Different MgO Reactivities

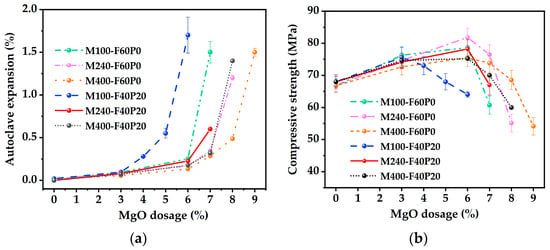

To assess the appropriate reactivity of MgO for the MgO-FA-PS system, cement paste specimens were prepared with 40% FA and 20% PS, incorporating MgO types M100, M240, and M400. These specimens were designated as M100-F40P20, M240-F40P20, and M400-F40P20, respectively. For comparison, the corresponding control specimens containing 60% FA were also prepared and named as M100-F60P0, M240-F60P0, and M400-F60P0. Figure 3 illustrates autoclave expansion and compressive strength curves for these cement pastes with various MgO reactivities.

Figure 3.

Effects of MgO reactivity on the autoclave expansion and compressive strength of cement pastes: (a) Autoclave expansion curves; (b) Compressive strength curves.

From the autoclave expansion curves in Figure 3a, the higher the MgO reactivity, the greater the autoclave expansion of cement paste, whether it is a binary or ternary binder system at the same MgO dosage. Although the hydration of MgO with lower reactivity is more sensitive to curing temperature, in general, MgO with higher reactivity hydrates more rapidly and completely due to its smaller grain size, more internal pores, and larger specific surface area [33], which collectively contribute to greater expansion. Sherir et al. [38] observed that specimens incorporating MgO with smaller particles exhibited slightly higher autoclave expansion than those incorporating MgO with larger particles. That is, to achieve the same amount of expansion, there is an inverse relationship between the MgO dosage and its reactivity. For instance, in the specimens labeled M100-F60P0, M240-F60P0, M400-F60P0, M100-F40P20, M240-F40P20, and M400-F40P20, the ultimate MgO dosages determined by the autoclave expansion of 0.5% were 6.2%, 7.2%, 8.0%, 4.8%, 6.8%, and 7.2%, respectively. Furthermore, Mo et al. [33] and Huang et al. [39] believed that MgO with lower reactivity induces greater expansion at a later age at the same MgO dosage. Increasing the dosage of low-reactivity MgO to achieve the desired expansion target inevitably increases the risk of delayed over-expansion in the later stages of cement paste. Consequently, MgO with too low reactivity is not recommended for use in the MgO-FA-PS system.

From the compressive strength curves in Figure 3b, the effect of MgO reactivity on compressive strength is related to whether the MgO dosage exceeds the specimen’s ultimate dosage. For example, when MgO dosage was 6%, the compressive strength values for specimens M100-F60P0, M240-F60P0, M400-F60P0, M100-F40P20, M240-F40P20, and M400-F40P20 were 78.6 MPa, 81.8 MPa, 75.4 MPa, 64.0 MPa, 78.2 MPa, and 75.2 MPa, respectively. Correspondingly, the expansions were 0.25%, 0.17%, 0.13%, 1.70%, 0.22%, and 0.18%. It was observed that except for M100-F40P20, MgO reactivity did not significantly affect compressive strength in either binary or ternary binder systems, which is consistent with findings of Mo et al. [40]. In contrast, the compressive strength of M100-F40P20 was significantly reduced compared to the other specimens. This is because the incorporation of 6% MgO exceeded the ultimate dosage of 4.8% for M100-F40P20, resulting in volume instability that manifested macroscopically as increased linear expansion and notable bending, ultimately leading to a sharp decrease in strength. On the other hand, Cao et al. [8] believed that although MgO with higher reactivity undergoes rapid expansion at an early age, its expansion at a later age does not completely cease, still posing a risk of excessive expansion. Therefore, MgO with too high reactivity is also not recommended in the MgO-FA-PS system. In conclusion, to prevent volume expansion failure and structural strength degradation in cementitious materials, the reactivity value of MgO in the MgO-FA-PS system should be maintained within the range of 240 ± 40 s.

It can also be concluded from Figure 3 that the cement paste containing 40% FA and 20% PS expanded more than the paste containing 60% FA, regardless of the MgO reactivity. This expansion pattern (i.e., the former > the latter) was roughly consistent with the conclusions drawn using mortar as autoclave specimens in Figure 1. However, there were differences in the expansions between cement paste and mortar as autoclave specimens, which might be ascribed to the variations in MgO reactivity or the types of test specimens.

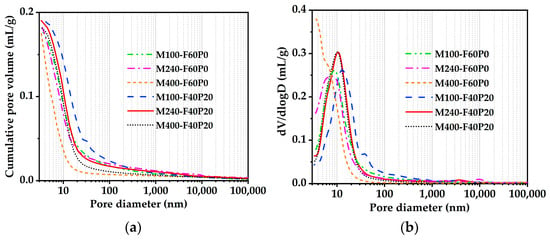

3.3. Pore Structure

The pore structures of autoclaved pastes admixed with 6% MgO were measured using the MIP method. The cumulative pore size distribution (CPSD) and differential pore size distribution (DPSD) are displayed in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively. Compared to the control specimens, the CPSD curves of cement pastes containing 40% FA and 20% PS were slightly shifted up, while their DPSD curves were slightly shifted right. The pore size corresponding to the highest peak on the DPSD curve is defined as the most probable pore diameter [41]. As shown in Figure 4b, the most probable pore diameters of the pastes containing 40% FA and 20% PS fell within the range of meso pore (10–50 nm), while those of the pastes containing 60% FA (control specimens) were within the range of gel micro pore (<10 nm) [41]. Thus, the most noticeable changes after incorporating PS were an increase in porosity and a coarsening of the pore size (Table 4). This can be attributed to the ability of PS to enhance the hydration of MgO, leading to the formation of additional brucite. The growth pressure exerted by these brucite crystals causes the expansion of micro pores [26], thereby increasing the porosity of the specimens. Despite the tendency for pore structures in test specimens incorporating PS to deteriorate, the compressive strengths of specimens M240-F40P20 and M400-F40P20 remained essentially unaffected, as illustrated in Figure 3. In contrast, the compressive strength of specimen M100-F40P20 decreased significantly. This is due to the varying increases in large capillary pores and porosity, which are primarily responsible for the decrease in compressive strength [42]. Generally, MgO with higher reactivity requires much more water consumed to achieve pastes with comparable workability, owing to its larger specific surface area [43]. As expected, this results in a more porous and less resistant microstructure. Microscopic pore structure analyses further suggest that the reactivity value of MgO in the MgO-FA-PS system should not be lower than 240 ± 40 s.

Figure 4.

Pore structures of the cement pastes admixed with 6% MgO: (a) Cumulative pore size distributions; (b) Differential pore size distributions.

Table 4.

Characteristic pore parameters from MIP.

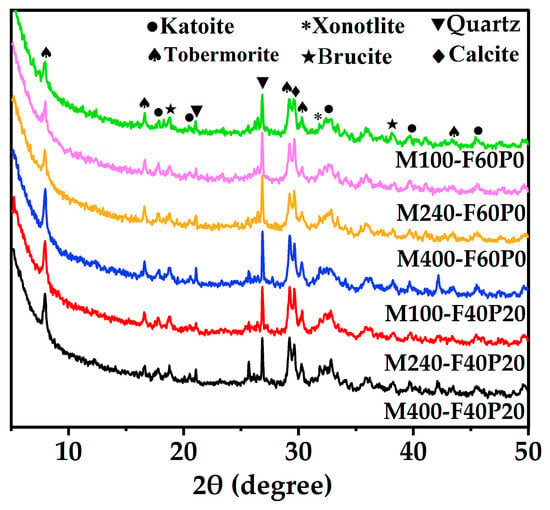

3.4. XRD Analysis

XRD was conducted on the autoclaved pastes admixed with 6% MgO to investigate the mineral compositions, and the results are illustrated in Figure 4. As observed in Figure 5, the XRD patterns of the autoclaved pastes were the same, and the main products included katoite, tobermorite, xonotlite, brucite, calcite, and quartz derived from FA and PS. Noticeably, periclase (MgO) and portlandite (Ca(OH)2) were not found, because MgO is overwhelmingly hydrated to form brucite under saturated water vapor conditions [35], while Ca(OH)2, a cement hydration product, continuously reacts with SiO2/Al3O2 dissolved from FA and PS to form C-S-H gel. C-S-H gel, which has low crystallinity and is unstable under autoclave conditions, can transform into the denser tobermorite at temperatures above about 180 °C, and then convert to xonotlite at 210 °C [41]. When the content of a mineral phase is as low as 2–3% or a minor phase, it becomes difficult to detect using the XRD method [41]. In addition, Figure 4 demonstrates that the incorporation of PS clearly enhanced the intensities of the diffraction peaks assigned to tobermorite and brucite in the cement pastes, whereas MgO reactivity had little effect on them.

Figure 5.

XRD patterns of the cement pastes admixed with 6% MgO.

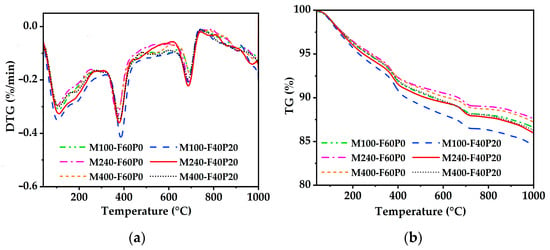

3.5. DTG-TG Analysis

Thermal analysis results of the autoclaved pastes admixed with 6% MgO are shown in Figure 6. Three obvious endothermic peaks were observed on the DTG curves, corresponding to the dehydration of C-S-H (tobermorite phase) below 200 °C [44], the dehydroxylation of Mg(OH)2 at about 330–420 °C, and the decarbonization of CaCO3 at about 620–750 °C, respectively. The presence of CaCO3 is primarily attributed to the carbonation occurring during the sample preparation process. It is noteworthy that no obvious endothermic peak was observed in the temperature range of 420–500 °C, which is typically associated with the dehydroxylation of Ca(OH)2 [43]. There was good correspondence with the XRD analysis. To gain further insight into the hydration process of MgO pastes, both with and without PS, the contents of Mg(OH)2 and chemically bound water (CBW, which indirectly characterizes the content of hydration products excluding Mg(OH)2) in the pastes were calculated using Equations (2) and (3), respectively [41].

where mMg(OH)2 and mCBW were the contents of Mg(OH)2 and chemically bound water, respectively; Δm40°C–1000°C corresponded to the total weight loss; Δm40°C–200°C corresponded to weight of physical absorption water; Δm330°C–420°C and Δm620°C–750°C corresponded to weight loss caused by decompositions of Mg(OH)2 and CaCO3, respectively.

Figure 6.

DTG-TG curves of the cement pastes admixed with 6% MgO: (a) DTG; (b) TG.

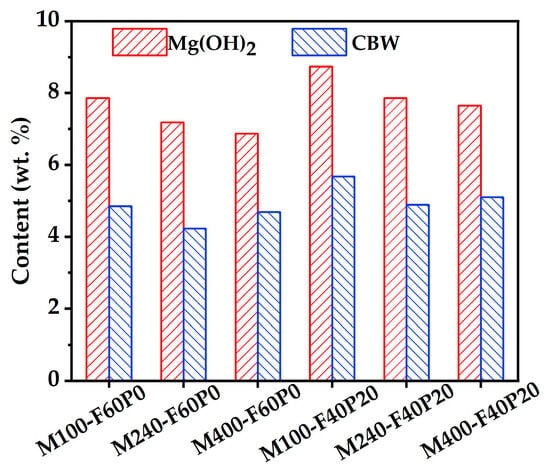

Figure 7 illustrates the distributions of Mg(OH)2 and CBW contents within the cement pastes admixed with 6% MgO. It can be observed that the contents of Mg(OH)2 and CBW in the cement pastes containing 40% FA and 20% PS were both higher than those in the control specimens, regardless of MgO reactivity, which was consistent with the XRD data in Figure 5. The PH values of the pore solutions in pastes M240-F60P0 and M240-F40P20 were measured using the exsitu leaching method [45], and their results were 10.4 and 10.7, respectively. These findings show that the addition of PS changed the pore solution alkalinity to some extent, thereby influencing the content of hydration products.

Figure 7.

Contents of Mg(OH)2 and CBW in the cement pastes admixed with 6% MgO.

Figure 7 also presents a comparative analysis of Mg(OH)2 and CBW contents in cement pastes with various MgO reactivities. For the same binder system, a positive correlation was observed between the Mg(OH)2 content and MgO reactivity. This suggests that MgO with higher reactivity may undergo rapid hydration in a short time due to the increased lattice distortion [46], resulting in enhanced Mg(OH)2 formation. Further examination of CBM variations indicated that the effect of MgO reactivity on CBM was similar to its effect on compressive strength, as discussed in Section 3.2. When the added MgO was below the specimen’s ultimate dosage, MgO reactivity exerted a negligible impact on CBW, as evidenced in specimens M240-F40P20 and M400-F40P20. Conversely, specimen M100-F40P20 exhibited the highest CBW content (Figure 7) but demonstrated the lowest compressive strength (Figure 3). This was attributed to the lower ultimate dosage of MgO in M100-F40P20. When the added MgO exceeds the specimens’ ultimate dosage, expansion stress increases, causing the cement matrix to crack. Although hydration continues, the strength development ceases [47] or may even decline.

3.6. Discussion

In comparison to the specimen utilizing FA as a sole SCM, the MgO-admixed specimen with partial substitution of FA by PS demonstrated increased autoclave expansion (Figure 1 and Figure 3). This observation suggests that PS mitigates less expansion caused by MgO hydration than FA at the same concentration. Within the MgO-FA system, the ability of FA to suppress MgO-induced expansion is primarily attributed to two factors. Firstly, the pozzolanic reaction promotes the conversion of Ca(OH)2 into the denser C-S-H product, strengthening the microstructure of the cement matrix. Secondly, it limits the formation of Mg(OH)2 by reducing pore solution alkalinity, which in turn alleviates expansion stress on the pore walls [38]. The synergistic effect of these two aspects enhances the system’s resistance to the MgO-induced expansion, thereby reducing expansion deformation. Regarding the reason for SCMs reducing the pore solution alkalinity, Shehata [48] conducted pore solution analyses and long-term expansion studies using 20 types of FA with varying calcium and alkali contents. The findings suggested that the higher levels of CaO and Na2O, coupled with the lower levels of SiO2 in FA, diminished its efficiency in lowering pore solution alkalinity. Sherir et al. [38,49] observed that MgO specimens incorporating high-calcium (17.28%) FA exhibited greater expansion compared to those with low-calcium (3.55%) FA, attributing this phenomenon to the CaO content. PS not only possesses a micro-aggregate filling and pozzolanic effect similar to that of FA, but also contains higher levels of CaO and Na2O and lower levels of SiO2 than FA (refer to Table 1). Meanwhile, the measured PH value of the MgO-FA-PS system based on the exsitu leaching method was higher than that of the MgO-FA system. Consequently, it can be believed that the higher CaO content in PS makes it less effective than FA in reducing pore solution alkalinity. This results in the F40P20 specimen containing more brucite crystals (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). Furthermore, a higher CaO content releases more hydration heat [19,38], thereby accelerating the hydration rate of MgO. This implies that more MgO dissolves into the pore solution. According to the expansion mechanism proposed by Chatterji [50], when the concentration of Mg2+ ions in the pore solution continues to rise and reaches supersaturation, brucite crystals begin to nucleate and grow. The resulting crystallization pressure causes the expansion of the cement matrix. Deng et al. [27], however, believed MgO hydrates to form fine-sized Mg(OH)2 crystals in a high-alkalinity pore solution, which mainly grow in narrow areas and cause significant expansion of concrete. Conversely, the hydration of MgO in a low-alkalinity pore solution yields coarse-sized crystals, which cause minor expansion due to their dispersion over wider areas.

On the other hand, the high level of CaO in PS increases the pore solution alkalinity, which in turn increases the amount of Ca(OH)2 [49]. The high concentration of Ca2+/OH− in the pore solution can further accelerate the pozzolanic reaction, resulting in an increased consumption of Ca(OH)2 crystals to produce more C-S-H (Figure 7) [49]. At this time, the competing interaction between the expansion stress induced by MgO hydration and the resistance of the cement matrix to this expansion determines the expansion behavior of the cement paste [33,47]. Obviously, the growth pressure generated by the continuous growth of Mg(OH)2 crystals plays a dominant role, thereby increasing porosity and coarsening the pore sizes within the cement matrix (Figure 4), ultimately resulting in greater expansion and a reduction in compressive strength (Figure 1 and Figure 3). When the increase in expansion stress is counterbalanced by the enhanced resistance of the cement matrix to expansion, a certain level of replacement can still maintain structural integrity [51], as observed when the proportion of PS replacing FA does not exceed 33%. If strength requirements are not stringent, the amount of PS replacing FA may be adjusted accordingly.

Although this study preliminarily demonstrated the feasibility of PS in MgO expansion systems and its replacement ratio through autoclave tests, certain limitations remain. For instance, the autoclave test conditions (high temperature and pressure) differ significantly from the actual service environment of concrete. Consequently, the expansion performance of M-RCC containing PS has yet to be verified. It should be noted that MgO hydrates very slowly at room temperature, and its complete hydration may take a year or even longer. Thus, the autoclave method, as a means to accelerate MgO hydration, provides crucial evidence for rapidly assessing the suitability of PS in MgO expansion systems and serves as an important reference for guiding concrete testing. To address the limitations of this study, subsequent research will investigate the long-term (at least a year) expansion deformation, mechanical properties, and microstructure of M-RCC with varying PS dosages. These findings will be compared with autoclave results to further explore the influence of PS on the expansion performance of MgO hydration and its mechanisms.

4. Conclusions

(1) With an increase in the substitution amount of PS for FA, the autoclave expansion of MgO-admixed mortars tended to increase. At a substitution ratio of 33% (i.e., a binder system of 40% PC, 40% FA, and 20%), the mortar maintained the same ultimate MgO dosage (8%) as the control specimen. However, the expansion increased by 12.7%, and the compressive strength decreased by 8.8%.

(2) The expansion mechanism of the MgO-FA-PS system can be attributed to the relative inefficiency of PS in reducing the pore solution alkalinity compared to FA. This inefficiency promotes the formation of more brucite. The growth pressure of brucite crystals expands the internal gaps in the matrix and coarsens the pore size, resulting in greater expansion and reduced compressive strength.

(3) In areas where FA is scarce or costly, but PS is readily available, PS can be utilized to partially replace FA in the preparation of MgO-admixed RCC. This approach effectively reduces project costs while promoting the utilization of PS solid waste and has significant economic and environmental advantages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and C.C.; methodology, R.C.; investigation, R.C.; data curation, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and C.C.; funding acquisition, R.C. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Guizhou Provincial Department of Education General Undergraduate University Scientific Research Project (Youth Project Qian Jiaoji [2022] 134), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51869005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bayqra, S.H.; Mardani, A.; Özen, S.; Ramyar, K. Effect of Delayed Placement of Layers on Permeability and Durability of Roller-Compacted Concrete Containing Fly Ash. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2075552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.C.; Tong, F.G.; Nguyen, V.N. Modeling of Autogenous Volume Deformation Process of RCC Mixed with MgO Based on Concrete Expansion Experiment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 210, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Li, W.W.; Yang, D.S.; Zhao, Z.H.; Yang, H.S. Study on Autoclave Expansion Deformation of MgO-Admixed Cement-Based Materials. Emerg. Mater. Res. 2017, 6, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.M.; Li, W.J. Application of Fast Damming Technology Admixed with MgO Expansive Concrete in Arch Dams. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2011, 31, 41–45+84. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.M. On the Development History and Current Status of China’s MgO Concrete Dam Construction Technology. Guangdong Water Resour. Hydropower 2012, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Recent Advance of MgO Expansive Agent in Cement and Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, G.X.; Li, X.; Guo, F.X.; Tang, S.W.; Lu, X.; Hanif, A. Influence of Reactivity and Dosage of MgO Expansive Agent on Shrinkage and Crack Resistance of Face Slab Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 126, 104333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.Z.; Miao, M.; Yan, P.Y. Effects of Reactivity of MgO Expansive Agent on Its Performance in Cement-Based Materials and an Improvement of the Evaluating Method of MEA Reactivity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 187, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.W.; Lu, X.L.; Tang, M.S. Shrinkage and Expansive Strain of Concrete with Fly Ash and Expansive Agent. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2009, 24, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.W.; Xu, S.Y.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Lu, X.L. Research on Autogenous Volume Deformation of Concrete with MgO. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, M.S.; Cui, X.H. Expansion of Cement Containing Crystalline Magnesia with and Without Fly Ash and Slag. Cem. Concr. Aggreg. 1998, 20, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Chen, R.F.; Zhao, P.; Yang, D.S. Research on Balanced Content of Magnesium Oxide in Roller Compacted Concrete. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8470426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, O.; Larsen, O.; Samchenko, S.; Aleksandrova, O.; Bulgakov, B. Pozzolanic Activity Assessment of Some Mineral Additives Used in Roller Compacted Concrete for Dam Construction. In Proceedings of the 20th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Proceedings SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 16–25 August 2020; pp. 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, M.H.; Hashim, S.F.S.; Dawood, E.T.; Johari, M.A.M. Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Roller Compacted Concrete Incorporating Brick Powder, Glass Powder, and Steel Slag. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2024, 33, 20220307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bheel, N.; Ahmed, I.; Rizvi, S.H.; Kumar, R.; Jhatial, A.A. Effect of Silica Fume and Fly Ash as Cementitious Material on Hardened Properties and Embodied Carbon of Roller Compacted Concrete. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 1210–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H.F.; Abu-bakr, M. Different Mineral Admixtures in Roller Compacted Concrete. J. Duhok Univ. 2023, 26, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; An, M.Z. Value-Added Reuse of Fine Phosphorus Slag Powder in Composite Cementitious Materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04025148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.P.; Chen, G.P.; Yang, R.; Yu, R.; Xiao, R.G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Xie, G.M.; Cheng, J.K. Hydration Kinetics and Microstructure Development of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) by High Volume of Phosphorus Slag Powder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 138, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, F.X.; Lin, Y.Q.; Yang, H.M.; Tang, S.W. Comparison between the Effects of Phosphorous Slag and Fly Ash on the C-S-H Structure, Long-Term Hydration Heat and Volume Deformation of Cement-Based Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zeng, L.; Fang, K.H. Anti-Crack Performance of Phosphorus Slag Concrete. Wuhan Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2009, 14, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.M.; Fang, K.H.; Yang, H.S. Research on the Strengthening Effect of Phosphorus Slag Powder on Cement-Based Materials. Key Eng. Mater. 2009, 405–406, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yu, R.; Shui, Z.H.; Gao, X.; Xiao, X.G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; He, Y. Low Carbon Design of an Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) Incorporating Phosphorous Slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.Q.; Guo, D.M.; Guo, S.C.; Yang, H.Q. Research and Application of Phosphorous Slag Powder in Dam Roller Compacted Concrete of Shatuo Hydropower Station. Guizhou Water Power 2012, 26, 67–70+79. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.M. Application and Research of Phosphorus Slag-Tuff Binary Admixture in RCC Gravity Dam of Dachaoshan Hydropower Station. Yunnan Water Power 2000, 16, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.L.; Ding, J.J.; Xiong, L.; Bao, M.; Zeng, P. On the Preparation of Low-Temperature-Rise and Low-Shrinkage Concrete Based on Phosphorus Slag. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2024, 20, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.Z.; Miao, M.; Yan, P.Y. Hydration Characteristics and Expansive Mechanism of MgO Expansive Agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 183, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Cui, X.H.; Liu, Y.Z.; Tang, M.S. Expansive Mechanism of Magnesia as an Additive of Cement. Nanjing Inst. Chem. Technol. 1990, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.J.; Wang, K.; Ma, H.Q.; Song, J.; Wang, J.L.; Sui, G.Y.; Gu, L.N. Study on Hydration Characteristics of Composite Cementitious System with MgO Expansion Agent. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.A.; Hu, Z.L.; Li, L.H.; Liu, J.P. A New Hypothesis for Full Stage Deformation of Cement-Based Materials Mixed with MgO Expansive Agent: Generation and Filling of Cavity. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.J.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, K.; Yang, Q.L. Expansion Performance and Microstructure of High-Performance Concrete Using Differently Scaled MgO Agents and Mineral Powder. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, R.S.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.J. Effects of Supplementary Cementitious Materials on Pore-Solution Chemistry of Blended Cements. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2022, 11, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, K.; Lothenbach, B.; Krüger, M.E.; Ranger, M.; Leemann, A. Impact of SCMs on Alkali Concentration in Pore Solution. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Alkali-Aggregate Reaction in Concrete, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 19–24 May 2024; Sanchez, L.F.M., Trottier, C., Eds.; RILEM Bookseries; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 49, pp. 3–10, ISBN 978-3-031-59418-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, L.W.; Fang, J.W.; Hou, W.H.; Ji, X.K.; Yang, J.B.; Fan, T.T.; Wang, H.L. Synergetic Effects of Curing Temperature and Hydration Reactivity of MgO Expansive Agents on Their Hydration and Expansion Behaviours in Cement Pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1596-2017; Fly Ash Used for Cement and Concrete. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GB/T 750-1992; Autoclave Method for Soundness of Portland Cement. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 1993.

- GB/T 17671-2021; The Method of Cement Mortar Strength Test Method (ISO Method). China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- DB52/T 720-2010; Technical Specification for MgO-Admixed Concrete Arch Dam Construction. Guizhou Quality and Technical Supervision Bureau: Guizhou, China, 2010.

- Sherir, M.A.A.; Hossain, K.M.A.; Lachemi, M. The Influence of MgO-Type Expansive Agent Incorporated in Self-Healing System of Engineered Cementitious Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 149, 164–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.N.; Xu, L.L. Effect of Mixing Light-Burned MgO with Different Activity on the Expansion of Cement Paste. Crystals 2021, 11, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.W.; Liu, M.; Al-Tabbaa, A.; Deng, M. Deformation and Mechanical Properties of the Expansive Cements Produced by Inter-Grinding Cement Clinker and MgOs with Various Reactivities. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 80, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.G.; Qu, X.L.; Li, J.H. Microstructure and Properties of Fly Ash/Cement-Based Pastes Activated with MgO and CaO under Hydrothermal Conditions. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, K.F.; Fen-chong, T.; Dangla, P. Pore Structure Characterization of Cement Pastes Blended with High-Volume Fly-Ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.; Silva, R.V.; de Brito, J.; Fernández, J.M.; Esquinas, A.R. Hydration of Reactive MgO as Partial Cement Replacement and Its Influence on the Macroperformance of Cementitious Mortars. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9271507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkeo, W.; Thongsanitgarn, P.; Chindaprasirt, P.; Chaipanich, A. Thermogravimetry of Ternary Cement Blends: Effect of Different Curing Methods. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 113, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Huang, W.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Duong, H.T.H.; Chang, Y.H. Standardized Procedure of Measuring the pH Value of Cement Matrix Material by Ex-Situ Leaching Method (ESL). Crystals 2021, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L.; Unluer, C. Durability of Carbonated MgO Concrete Containing Fly Ash and Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 192, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Gu, K.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Strength and Hydration Properties of Reactive MgO-Activated Ground Granulated Blastfurnace Slag Paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 57, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.H. The Effects of Fly Ash and Silica Fume on Alkali Silica Reaction in Concrete. Ph. D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sherir, M.A.A.; Hossain, K.M.A.; Lachemi, M. Self-Healing and Expansion Characteristics of Cementitious Composites with High Volume Fly Ash and MgO-Type Expansive Agent. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 127, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, S. Mechanism of Expansion of Concrete Due to the Presence of Dead-Burnt CaO and MgO. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995, 25, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Ansari, W.S.; Akbar, M.; Azam, A.; Lin, Z.B.; Yosri, A.M.; Shaaban, W.M. Microstructural and Mechanical Assessment of Sulfate-Resisting Cement Concrete over Portland Cement Incorporating Sea Water and Sea Sand. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).