Abstract

The escalating demand for high-performance energy storage devices has driven extensive research into flexible electrode materials for supercapacitors. Integrating structured carbon nanomaterials with flexible substrates to construct binder-free electrode architectures represents a promising strategy for improving supercapacitor capacitance and rate capability. However, achieving stable, binder-free integration of structure-controlled nanostructured carbon materials with flexible substrates remains a critical challenge. In this study, we report a direct synthesis approach for one-dimensional (1D) carbon nanofibers (CNFs) on commercial flexible carbon fabric (CF) via chemical vapor deposition (CVD). The resulting CNFs exhibit two typical average diameters—approximately 25 nm and 50 nm—depending on the growth temperature, with both displaying highly graphitized structures. Electrochemical characterization of the CNFs/CF composites in 1 M H2SO4 electrolyte revealed typical electric double-layer capacitor (EDLC) behavior. Notably, the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrode achieves a high specific capacitance of 87.5 F/g, significantly outperforming the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode, which reaches 50.2 F/g. Compared with previously reported carbon nanotube CNTs/CF electrodes, the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrode exhibits superior capacitance and lower resistance.

1. Introduction

Global energy transition initiatives, driven by the need to mitigate fossil fuel depletion and environmental concerns, have spurred rapid advancements in energy storage technologies [1]. Supercapacitors have emerged as a key component in energy storage systems due to their low cost, light weight, rapid charge–discharge capability, and long cycle life [2].

Supercapacitors are generally categorized into two types based on their energy storage mechanisms: pseudocapacitors and electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs). Pseudocapacitors store charge through fast and reversible Faradic redox reactions at the electrode–electrolyte surface, while EDLCs store energy through electrostatic charge accumulation at the interface without any chemical reaction. As a result, EDLCs demonstrate excellent cycle stability and reversibility [3].

Carbon-based materials are widely used in commercial supercapacitors, primarily due to their multiple advantageous properties. These properties include a large specific surface area (SSA) that enables efficient charge adsorption, high electrical and thermal stability to sustain performance under various working conditions, strong chemical inertness that prevents unwanted reactions with electrolytes, and favorable cost-effectiveness that fits industrial production requirements [4]. Commonly used carbon materials include carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], carbon nanofibers (CNFs) [13,14], carbon paper (CP), and carbon fabric (CF) [8,9,10,11,12,15,16,17]. Among these, CP and CF are typically employed as flexible substrates, serving as structural support for electrode components while ensuring mechanical adaptability. In contrast, CNTs and CNFs share one-dimensional (1D) structural features; this unique morphology not only endows them with a large SSA and excellent electrical conductivity to promote rapid charge transfer but also ensures superior chemical stability during prolonged charge–discharge cycles, thereby positioning them as highly promising electrode materials for advanced supercapacitor systems [18,19].

In the present work, an uncomplicated strategy was developed to fabricate integrated three-dimensional (3D) composite electrodes, which involves the direct growth of one-dimensional (1D) carbon nanofibers (CNFs) on flexible commercial carbon fabric (CF) through a chemical vapor deposition (CVD) process. To characterize the CNFs/CF composites obtained, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Raman spectroscopy were employed to analyze their morphology and microstructure. For the evaluation of electrochemical performance, a three-electrode system was adopted, with cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) serving as the test methods. Furthermore, we systematically investigated the influence of morphology, microstructure, fiber diameter, interfacial phase, and pore distribution on the electrochemical properties, thereby revealing the structure–performance relationship for carbon-based supercapacitor systems.

2. Materials and Methods

Commercial knitted carbon fabric (CF, model T-300, plain weave, Toray Co., Tokyo, Japan) was selected as the flexible substrate. The CF pretreatment process involved three key steps: first, the catalyst slurry was prepared [20]. Second, the cleaned CF was dipped into a catalyst slurry (containing nickel nanoparticles as the catalyst precursor) for 30 s, followed by placement on filter paper and drying at room temperature for 30 min to ensure uniform catalyst loading. Third, the catalyst-coated CF was transferred to a horizontal tube furnace (OTF-1200X, Hefei Kejing Materials Technology Co., Hefei, China) for the CVD process. Prior to CNF growth, a 15 min heat treatment was performed under a mixed atmosphere of H2 (60 sccm) and Ar (120 sccm). CNF growth was conducted at two different temperatures (750 °C and 800 °C) using ethylene (C2H4) as the carbon source, yielding CNFs with average diameters of approximately 50 nm (750 °C) and 25 nm (800 °C), respectively.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S-4700, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan, 15 kV) was used to observe the morphology and diameter distribution of CNFs on the CF substrate. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, G-20, FEI-Tecnai, Hillsboro, OR, USA, 200 kV) and Raman spectroscopy (Confocal Raman Microscope, in Via, Renishaw, New Mills, UK) were employed to analyze the microstructure and graphitization degree of the CNFs. The electrochemical performance of CNFs/CF composites was characterized via a Solartron 1400 electrochemical workstation (Solartron Analytical, Hampshire, UK) at ambient temperature, adopting a three-electrode configuration. The CNFs/CF composite served as the working electrode (1 cm × 2 cm), complemented by a platinum foil as the counter electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode, with 1 M H2SO4 aqueous solution employed as the electrolyte. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were implemented within a potential window of 0–1 V at scan rates varying from 5 to 200 mV/s. Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements were executed at current densities ranging from 0.1 to 2 A/g. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were performed in the frequency domain of 10 MHz to 0.1 Hz, with an initial potential of 0 V and a ±5 mV potential perturbation applied around the equilibrium state. All specific capacitances and current densities of the composites were calculated based on the mass of CNFs.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological and Microstructural Features of CNF/CF Composites

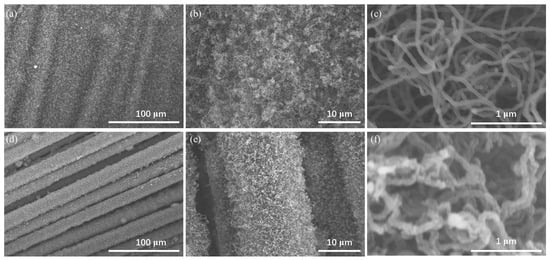

Figure 1 depicts the morphological characteristics of CNFs/CF with varying diameters at distinct magnifications. The CNFs exhibit entanglement, forming an interconnected network with ample open pores. This porous 3D structure promotes rapid transport of electrolyte ions to the entire surface of the CNFs/CF electrodes, thus supporting efficient electric double-layer formation. At a reaction temperature of 800 °C (Figure 1a–c), the carbon fabric was bridged by CNFs, rendering the inter-fiber boundaries obscure. The carbon fiber surface was sheathed in a dense mat of CNFs, with an average diameter of roughly 25 nm. At this temperature, catalysts displayed enhanced catalytic activity, and carbon sources exhibited a faster diffusion rate, yielding CNFs with a larger length–diameter ratio. A control experiment was conducted at a reaction temperature of 750 °C, as illustrated in Figure 1d–f. It can be seen that the carbon fibers were encapsulated by CNFs, whose average diameter was approximately 50 nm.

Figure 1.

The SEM images of CNFs/CF with varying diameters at distinct magnifications: (a–c) 25 nm-CNFs/CF, (d–f) 50 nm-CNFs/CF.

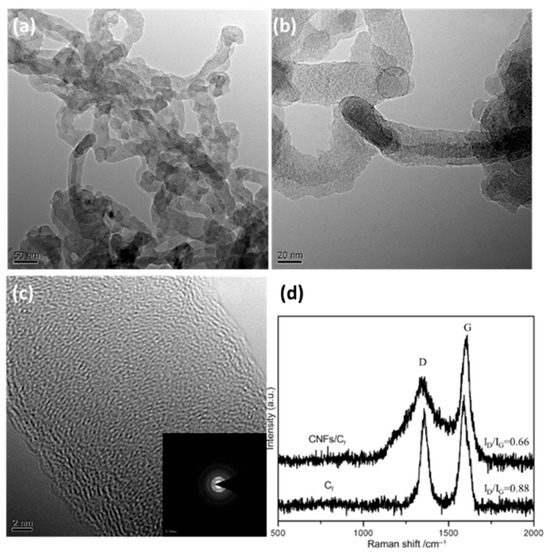

TEM and Raman spectroscopy were used to further characterize the microstructure of the 25 nm-CNF/CF composite (Figure 2). The TEM micrographs (Figure 2a–c) illustrate that the CNFs feature a solid cylindrical microstructure, which is distinct from the archetypal hollow tubular architecture of carbon nanotubes (CNTs). Furthermore, the electron diffraction pattern (inset of Figure 2c), characterized by well-defined diffraction rings, provides direct evidence for the material’s considerable graphitization crystallinity. Notably, the Raman spectrum (Figure 2d) exhibits the characteristic D peak (centered at ~1350 cm−1, associated with structural disorder or defects in carbonaceous materials) and G peak (centered at ~1580 cm−1, corresponding to the in-plane vibrational mode of sp2-hybridized carbon bonds) [21]. Evaluation of the ID/IG peak intensity ratio, a widely utilized metric for quantifying graphitic order/disorder, reveals that this ratio for the CNFs/CF composite (0.66) is markedly lower than that for pristine CF (0.88). This observation indicates that the incorporation of CNFs effectively enhances the graphitization order of the material, thus corroborating the high graphitization degree inferred from the electron diffraction pattern in the TEM characterization.

Figure 2.

The TEM images and Raman spectrum of 25 nm-CNFs/CF. (a) Low-magnification TEM image; (b) Magnified TEM image of the local region; (c) High-resolution TEM image and electron diffraction pattern; (d) Raman spectra of CNFs/CF and CF.

3.2. Electrochemical Properties of CNFs/CF

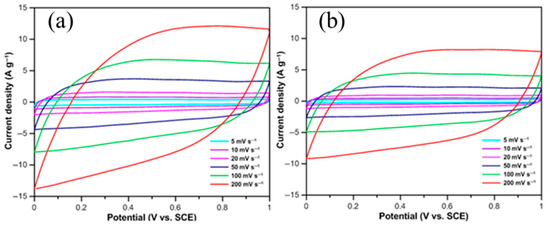

Figure 3 shows the CV curves of the 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrodes at different scan rates. Both electrodes exhibit approximately rectangular CV curves without obvious redox peaks across the entire potential window (0–1 V), confirming that their energy storage mechanism is dominated by EDLC behavior. The electrolyte ions can be rapidly and uniformly adsorbed onto the CNFs/CF surface to form a stable electric double layer. Upon instantaneous reversal of the scan direction, the current promptly inverts and stabilizes, demonstrating excellent electrochemical reversibility of the CNFs/CF composites.

Figure 3.

The CV curves of CNFs/CF with different diameters under different scan rates: (a) 25 nm-CNFs/CF, (b) 50 nm-CNFs/CF.

The scan rate exerts a significant influence on the current intensity and enclosed area of the CV curve, which are directly correlated with the specific capacitance of the electrode material, and the experimental results indicate that with increasing scan rate, the current of the CV curves for both CNFs/CF composites increases proportionally, and the enclosed area expands synchronously while the curve morphology remains essentially unchanged, which is an indication of the good rate capability of the materials. Additionally, at all scan rates, the enclosed area of the CV curves for the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrode is significantly larger than that of the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode, reflecting a higher specific capacitance.

Based on the CV curves, the specific capacitance (C, F g−1) can be derived using Equation (1):

In this equation, m denotes the mass of the CNFs, v represents the potential scan rate, (Va − Vc) stands for the sweep potential window, and I(V) refers to the voltametric current obtained from the CV curves. The results of these calculations are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1.

The specific capacitance of CNFs/CF with different diameters under different scan rates.

As exhibited in Table 1, the specific capacitances of the two CNFs/CF composites exhibit a decreasing trend with the elevation of the scan rate. At a scan rate of 5 mV/s, the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrode exhibits a specific capacitance of 77.0 F/g, in contrast to the 46.8 F/g delivered by the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode. As the scan rate is elevated to 200 mV/s, the specific capacitance of the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrode drops to 36.3 F/g (corresponding to a capacitance retention of ~47.1%), while that of the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode decreases to 28.3 F/g with a higher capacitance retention of 60.5%. This variation trend aligns well with the intrinsic energy storage mechanism of EDLCs. At low scan rates, electrolyte ions possess adequate time to diffuse into the porous framework of the electrode, enabling the full development of electric double layers and thus realizing high specific capacitance. Conversely, at high scan rates, the ion diffusion rate fails to keep pace with the voltage sweeping speed, resulting in incomplete formation of electric double layers and a consequent reduction in capacitance. The superior capacitance retention of the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode under high scan rate conditions may be ascribed to its larger pore size, which facilitates more efficient penetration and transport of electrolyte ions.

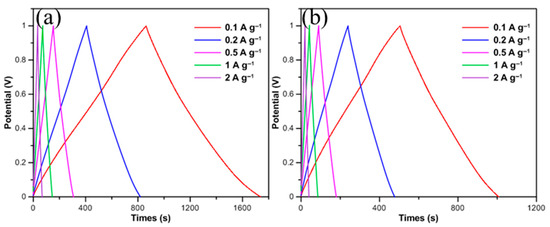

Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) measurements for CNFs/CF composites with different CNF diameters were performed within a current density range of 0.1–2 A/g, with the operating voltage confined between 0 V and 1 V. Figure 4 exhibits the GCD curves of 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF, respectively. Both electrodes feature nearly isosceles triangular GCD curves with good symmetry. This characteristic not only indicates high charge–discharge efficiency and excellent electrochemical reversibility but also aligns with the results obtained from CV tests. An abrupt potential drop commonly occurs at the initial stage of constant current discharge, which is defined as the IR drop. Meanwhile, only a slight IR drop appears at the initial stage of the discharge curves of both composites, which indicates that the CNFs/CF composites have low internal resistance properties, reflecting the formation of a good interfacial bonding between CNFs and the CF substrate, and the device, as a whole, exhibits excellent electrical conductivity and ion diffusion/transport capabilities.

Figure 4.

The GCD curves of CNFs/CF with different diameters under different scan rates: (a) 25 nm-CNFs/CF, (b) 50 nm-CNFs/CF.

It should be emphasized that under all test conditions, the discharge time of the CNFs/CF composites marginally exceeds their charge time. For instance, Figure 4b presents the test data of the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode at a current density of 0.1 A/g. Its charge time is 505.6 s, whereas the discharge time reaches 502 s. This slight discrepancy may be associated with the kinetic characteristics of the ion adsorption–desorption processes occurring on the electrode surface. Additionally, further analysis reveals that the specific capacitances of both 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrodes exhibit a gradual decreasing trend as the current density increases. This regularity indicates that the ion accessibility within the CNF layer is the dominant factor leading to capacitance degradation. At high current densities, electrolyte ions cannot fully diffuse into the microporous structure of the electrode material within a short time, resulting in reduced utilization of the electrode surface and ultimately manifesting as a decrease in specific capacitance. Overall, both CNFs/CF composites exhibit stable capacitance output characteristics and good electrochemical reversibility when used as supercapacitor electrode materials. This conclusion is highly consistent with the analysis results of cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests, verifying the reliability of the characterization results.

The specific capacitance (C, F/g) can be calculated from the charge–discharge curves based on Equation (2):

In this equation, m denotes the mass of CNFs, I refers to the applied current, and dV/dt represents the slope of the discharge curve after the IR drop.

Table 2 summarizes the calculated specific capacitance results of CNFs/CF composites with different diameters under various current densities. At a low current density of 0.1 A/g, the two composites achieve specific capacitances of 87.5 F/g and 50.2 F/g, respectively. With the current density elevated to 1 A/g, their specific capacitances stand at 72.8 F/g and 42.8 F/g, corresponding to capacitance retentions of 83.20% and 85.26% in sequence. Furthermore, as the current density is further increased to 2 A/g, 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF still retain specific capacitances of 67.6 F/g and 40.0 F/g, demonstrating good rate stability.

Table 2.

The specific capacitance of CNFs/CF with different diameters under different current densities.

For 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF, the maximum specific capacitances were found to be 87.5 F/g and 50.2 F/g, respectively. Systematic research into the structural and electrochemical characteristics of VACNT/CF and ECNT/CF composites was reported in a previous work [5], in which the maximum specific capacitances of 50 nm-VACNT/CF and 50 nm-ECNT/CF were documented as 75 F/g and 42 F/g, respectively. To elucidate the key factors governing the specific capacitance of carbon-based composite electrodes, comparative analyses were conducted between the materials synthesized in this work and those reported in the literature [5]. In the VACNT/CF electrode system, the VACNTs can only grow along certain directions [5,22,23]. Directional growth constraints limit the expansion of the surface area, as evidenced by lower specific capacitance than irregularly porous 25 nm-CNFs/CF.

To further clarify the role of structural characteristics in determining capacitance performance, a comparative evaluation of the maximum specific capacitances between 50 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-ECNT/CF electrodes was performed, which demonstrates that the unique hollow structure of CNTs does not exert a substantial effect on enhancing specific capacitance. It is widely recognized that the most prominent structural distinction between CNTs and CNFs resides in the presence or absence of a characteristic hollow tubular architecture. Theoretically, the intrinsic tubular structure of CNTs should endow them with a larger specific surface area and thus superior specific capacitance relative to CNFs. However, several factors mitigate this theoretical advantage: firstly, the interlayer spacing of multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) is typically smaller than the ionic radius of adsorbing species, which inhibits ion penetration into the interlayer regions and thereby eliminates capacitance contribution from these domains. Secondly, the inner channels of CNTs are often underutilized due to the size-dependent limitations of ion infiltration, offsetting the potential capacitance gains associated with their hollow structure. Additionally, microstructural defects and growth mechanisms of nanomaterials can regulate the electrode’s internal resistance, and this parameter is closely correlated with the measured specific capacitance. In the present study, the as-synthesized CNFs show a high degree of graphitization (Figure 2c), and the tip-growth mechanism used in their preparation helps form robust C-C covalent bonds at the interface between carbon nanofibers and carbon fiber current collectors. Consequently, despite the absence of a distinct hollow structure, the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode still exhibits a slightly higher specific capacitance than the 50 nm-ECNT/CF electrode.

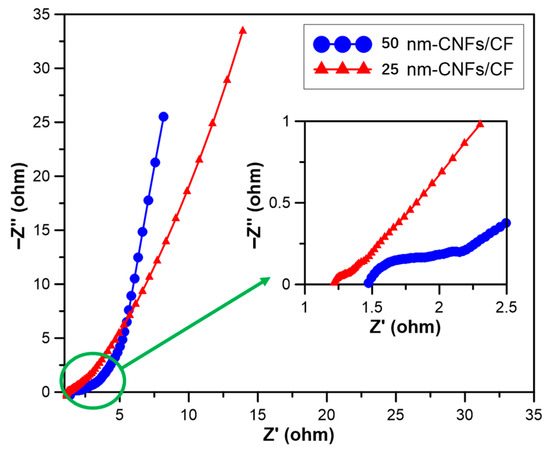

For a deeper insight into the charge transfer processes and electrochemical kinetics of the electrodes, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were carried out over a frequency range of 10 MHz to 100 kHz, using a 5 mV perturbation amplitude relative to the open-circuit potential. The corresponding Nyquist plots, along with a partial magnification of the high-frequency segment for the 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF composites, are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The EIS images of CNFs/CF with different diameters.

The Nyquist plots consist of three distinct regions:

- (i)

- A high-frequency region: For an ideal supercapacitor, the curve in this area should be perpendicular to the horizontal axis when a high-frequency signal is introduced. Nevertheless, because Faraday reactions take place on the electrode surface, the typical feature observed here is a semicircle. As such, this region is used to assess the Faraday impedance of the electrode materials. The semicircle’s size is associated with the material’s morphology and conductivity. Its diameter represents the charge transfer resistance (Rct) at the electrode–electrolyte interface, while the X-axis intercept of the semicircular curve reflects the electrode resistance (Rt), which is primarily linked to electrolyte resistance (Rs), the internal resistance of the active material (Rm), and the contact resistance (Rc) between the collector and the electrolyte.

- (ii)

- A medium-frequency region: Commonly referred to as the Warburg region, this area typically features a straight line with a 45° slope, corresponding to semi-infinite Warburg impedance (Rw). By extending the line in the reverse direction, the intersection of the X-axis can characterize the value of Rw.

- (iii)

- A low-frequency region: In this region, a vertical line emerges, caused by ion accumulation at the bottom of the electrode material’s pores. The closer this line is to being parallel to the y-axis, the more the device approaches the behavior of an ideal capacitor [17].

Figure 5 shows that for both CNFs/CF composites, the high-frequency region contains an incomplete semicircle. This suggests that the CNFs/CF electrodes have low resistance at the CNF–CF interface. When compared with 25 nm-CNFs/CF, the 50 nm-CNFs/CF has a larger area enclosed by its semicircle. By analyzing the Nyquist plots in the high-to-medium frequency range, the Rct of the 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF composites (derived from the X-axis intercept) are determined to be 1.2 Ω and 1.4 Ω, respectively. In the medium-frequency region, the Rw values for the 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF composites are found to be 1.25 Ω and 1.8 Ω, respectively. At low frequencies, the plot for 50 nm-CNFs/CF becomes nearly vertical, signifying ideal capacitive behavior with minimal diffusion resistance. In contrast, the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrodes show a relatively gentle slope. To summarize, 25 nm-CNFs/CF has lower overall resistance and superior energy storage performance. Meanwhile, 50 nm-CNFs/CF behaves more like an ideal capacitor, showing higher capacitance retention. These results are consistent with the outcomes of cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests.

4. Conclusions

Using the CVD method, we successfully fabricated CNFs/CF composite electrodes by growing CNFs directly on CF substrates—these electrodes feature a large specific surface area and a high degree of graphitization. When the growth temperature was set to 800 °C, the CNFs attained their optimal morphology, with fibers exhibiting an average diameter of approximately 25 nm. Electrochemical characterization confirmed that these CNFs/CF electrodes possess EDLC characteristics, achieving a maximum specific capacitance of up to 87.5 F/g. A comparison with previously reported CNTs/CF electrodes reveals that CNFs/CF is a promising candidate for high-performance EDLC electrodes, holding strong application potential in flexible, portable, and wearable electronic devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, X.J.; investigation, J.W. and J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank AVIC The First Aircraft Institute for the research support, and Northwestern Polytechnical University (NWPU) for providing technical assistance. The manuscript text was rephrased and grammar-checked using Doubao AI to improve clarity and language flow. All scientific content, interpretations, data analysis, and conclusions were developed entirely by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Olabi, A.G.; Abbas, Q.; Al Makky, A.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Supercapacitors as next generation energy storage devices: Properties and applications. Energy 2022, 248, 123617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaheldeen, M.; Eskander, T.N.A.; Fathalla, M.; Zhukova, V.; Blanco, J.M.; Gonzalez, J.; Zhukov, A.; Abu-Dief, A.M. Empowering the Future: Cutting-Edge Developments in Supercapacitor Technology for Enhanced Energy Storage. Batteries 2025, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejjanki, D.; Puttapati, S.K. Supercapacitor basics (EDLCs, pseudo, and hybrid). In Multidimensional Nanomaterials for Supercapacitors: Next Generation Energy Storage; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2024; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Hossain, M.S.; Adak, B.; Rahman, M.M.; Kubra Moni, K.; Nur, A.S.; Hong, H.; Younes, H.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Recent advancements in carbon-based composite materials as electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 114838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Zhang, P.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. Vertically aligned carbon nanotubes grown on carbon fabric with high rate capability for super-capacitors. Synth. Met. 2012, 162, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskher, H.; Ghernaout, D.; Thakur, A.K.; Jazi, F.S.; Alsalhy, Q.F.; Christopher, S.S.; Sathyamurhty, R.; Saidur, R. Prospects of functionalized carbon nanotubes for supercapacitors applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, G.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z. Comparison between electrochemical properties of aligned carbon nanotube array and entangled carbon nanotube electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 155, K19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Chung, H.; Kim, W. Supergrowth of aligned carbon nanotubes directly on carbon papers and their properties as supercapacitors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 15223–15227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.T.; Chen, W.Y.; Cheng, Y.S. Influence of oxidation level on capacitance of electrochemical capacitors fabricated with carbon nanotube/carbon paper composites. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 5294–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.T.; Teng, H.; Chen, W.Y.; Cheng, Y.S. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical capacitance of amino-functionalized carbon nanotube/carbon paper electrodes. Carbon 2010, 48, 4219–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lv, P.; Zhang, P.; Feng, W. Electrodeposition of carbon nanotube/carbon fabric composite using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide for high-performance capacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 60, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Zhang, P.; Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Feng, W. High-performance electrochemical capacitors using electrodeposited MnO2 on carbon nanotube array grown on carbon fabric. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 78, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, D.G.; Song, W. Improving supercapacitor electrode performance with electrospun carbon nanofibers: Unlocking versatility and innovation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 22346–22371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.P.; Mukhiya, T.; Muthurasu, A.; Chhetri, K.; Lee, M.; Dahal, B.; Lohani, P.C.; Kim, H.Y. A review of electrospun carbon nanofiber-based negative electrode materials for supercapacitors. Electrochem 2021, 2, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Wei, G. Carbon nanofiber-based three-dimensional nanomaterials for energy and environmental applications. Mater. Adv. 2020, 1, 2163–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lee, C.Y.; Chiu, H.T. Chemical vapor deposition of carbon nanocoils three-dimensionally in carbon fiber cloth for all-carbon supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Shu, K.; Hu, H.; Wu, X.; Tang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Facile synthesis and modification of Fe2O3 nanorod arrays on carbon paper as efficient negative electrodes for supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 979, 173578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K. One-dimensional nanocomposites for renewable energies. In Nanotechnology for Next-Generation Energy Storage; Elsevier: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Owusu, K.A.; Xu, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, G.; Yang, W.; Mai, L. 1D Carbon-based nanocomposites for electrochemical energy storage. Small 2019, 15, 1902348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Du, H. An Ultrathin CNFs/CF Composite and the Performance of Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Nano 2023, 18, 2350104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, A.; Dhamelincourt, P.; Laureyns, J.; Alonso, A.M.; Tascon, J.M.D. Raman microprobe studies on carbon materials. Carbon 1994, 32, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.T.; Chen, W.Y.; Lin, J.H. Synthesis of carbon nanotubes on carbon fabric for use as electrochemical capacitor. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 122, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.J.; Wardle, B.L.; Hart, A.J.; Yamamoto, N. Fabrication and multifunctional properties of a hybrid laminate with aligned carbon nanotubes grown in situ. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2034–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).